ABSTRACT

The study aimed to assess the potential of smartphone applications for strengthening accountability in public agricultural extension services. Therefore, a smartphone application called ‘e-diary’ was developed and tested in Uganda. A Design Science Research approach was used for the development and assessment of the e-diary. Individual face-to-face interviews and focus group discussions were used for data collection. Data analysis was conducted using the content analysis method. The findings indicate that smartphone applications have the potential to strengthen accountability in the public agricultural extension services by enabling remote supervision in real-time, which reduces the costs and time of supervision. However, the study also indicates that the successful implementation of such tools requires incentives such as awards of recognition. These findings contribute to the understanding of the potential role of ICTs in strengthening the management of public services (such as agricultural extension) in developing economies.

1. Introduction

The spread of Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs) in developing countries offers new opportunities that may aid the realization of the global sustainable development goals. ICTs can play a vital role in improving the delivery of public services such as agricultural, education and health services, which are key drivers of development (Aker, Citation2011; Baumüller, Citation2018; Tata & McNamara, Citation2018). In particular, studies have frequently highlighted the importance of public agricultural extension for development: extension systems help to transfer knowledge and technologies to farmers and other value chain actors, thus enhancing farm productivity, alleviating poverty and ensuring food security (Benin et al., Citation2011; Birner & Resnick, Citation2010; Hazell et al., Citation2010). ICTs have great potential to improve agricultural extension service delivery, specifically in regards to reducing information asymmetry, costs and time; which subsequently facilitates the diffusion and uptake of agricultural technologies (Arinloye et al., Citation2015; Deichmann et al., Citation2016; Lio & Liu, Citation2006; World Bank, Citation2011). Evidence from the literature has shown that ICTs for agricultural extension have a positive impact on yields, productivity, food security and ultimately rural incomes (Al-Hassan et al., Citation2013; Casaburi et al., Citation2014; Cole & Fernando, Citation2016; Lio & Liu, Citation2006).

While ICTs hold great promise for improving the delivery of agricultural extension services, their application for strengthening the accountability of public agricultural extension services remains less explored. So far, the application of ICTs in agriculture has focused on strengthening the capacity of extension services to communicate with farmers and to facilitate farmers’ access to information about technologies, weather and markets (Arinloye et al., Citation2015; Fafchamps & Minten, Citation2012; Jain et al., Citation2015; Nakasone et al., Citation2014). However, establishing an accountable system is essential for improving system performance and consequently effective and efficient service delivery (Brinkerhoff, Citation2004). Since public agricultural extension systems usually deploy large numbers of field agents in remote and widely dispersed geographic areas, their hierarchical, top-down, supply-driven management approach makes supervision difficult (Anderson & Feder, Citation2004; Feder et al., Citation2010). This is further compounded by underdeveloped transport infrastructure, a lack of resources and a lack of robust supervisory tools that enable both the supervisors and beneficiaries to adequately follow up the activities of the field agents and provide feedback (DeRenzi et al., Citation2011; Nakasone & Torero, Citation2016). The above factors contribute significantly to the weak accountability in public agricultural extension systems that has been observed. As a result, the systems are characterized by absenteeism, shirking and moonlighting by the field agents, thus reducing service utility (Chaudhury et al., Citation2006; Fujii, Citation2019; Goldstein et al., Citation2013; Ramadhan, Citation2013).

While there is limited evidence on the application of ICTs for accountability in agriculture, studies in other development sectors, in particular education and health, have demonstrated the potential of ICTs to strengthen supervision and accountability (Biemba et al., Citation2017; Cilliers et al., Citation2014; Henry et al., Citation2016). However, unlike agriculture, services in health and education are located in designated places, and it is the clients that seek the services. In addition, the ICT solutions that have been developed in these sectors are rarely smartphone-based and may therefore limit the provision of platforms that could enable, for example: remote or distant monitoring, supervision and feedback in real-time, the capture of beneficiary data which could be used to verify agents’ visits (Aker, Citation2011; Aker et al., Citation2016; DeRenzi et al., Citation2011). Not using ICT tools may be associated with the following types of costs: (1) supervision costs such as transport costs and travel time to physically follow up the field agents, (2) coordination costs, (3) cost of obtaining feedback from the beneficiaries by physical visits to the beneficiaries, and (4) reporting costs such as more time needed to generate reports, travel time and travel costs of report submission. For the farmers, these costs can translate into less utility from the services, and ultimately lower yields and lower incomes.

It is against this background that a unique ICT tool: a smartphone application called ‘e-diary’ was developed and tested in Uganda. The e-diary, which integrates a Global positioning system (GPS), photograph recording and profiles for beneficiaries (farmers and other value chain actors), enables field agents to report their daily activities in real-time, and also allows remote supervision and feedback from the beneficiaries. The objective of the study was to assess the potential of using smartphone applications in strengthening accountability in the public agricultural extension services. The key research question that motivated this study was: Can smartphone applications be used for strengthening accountability in public agricultural extension services?

This study demonstrates the opportunities for using ICT tools, particularly smartphone applications, for strengthening the accountability of agricultural extension services, which have hitherto not been widely applied. In the context of ICT for development, the findings of the study illustrate how ICTs can be applied to strengthen the management of public services, which are key for development. The findings of the study are therefore relevant for both academics and practitioners in agricultural extension as well as other public services where the accountability of field agents is a challenge.

2. Literature review

2.1. Accountability in the context of public service delivery

According to Paul (Citation1992), ‘accountability means holding individuals and organizations responsible for performance measured as objectively as possible’ (p. 1047) and public accountability refers to the ‘spectrum of approaches, mechanisms and practices used by the stakeholders concerned with public services to ensure a desired level and type of performance’ (p. 1047). In the context of public service delivery, accountability can be conceptualized into upward and downward accountability. Upward accountability means holding the public servants responsible for their performance by their higher-level supervisors (Yilmaz et al., Citation2010). Conversely, downward accountability means holding the public servants responsible by the beneficiaries of the services (Devas & Grant, Citation2003; Wongtschowski et al., Citation2016).

In the public agricultural extension services, weak accountability of field agents has been identified as one of the characteristic challenges in service delivery (Anderson & Feder, Citation2004). Weak upward accountability arises due to a lack of robust supervisory mechanisms, making it difficult for the supervisors to monitor and evaluate the performance of large numbers of remotely dispersed field agents. Correspondingly, the weak downward accountability is largely due to the limited voice of the beneficiaries such as a lack of farmer complaint mechanisms, in addition to the top-down, supply-driven, hierarchical management approaches that are characteristic of public bureaucracies (Anderson & Feder, Citation2004; Feder et al., Citation2010; Paul, Citation1992).

Consequently, upward accountability can be strengthened by establishing mechanisms to increase the capacity and incentives of the supervisors to adequately follow up on the field agents’ activities. Equally, downward accountability can be strengthened by improving the beneficiaries’ ability to demand better services, provide feedback to the public agencies and hold them accountable (Birner, Citation2007).

2.2. The role of ICTs in agricultural development

Information and Communication Technologies are widely acknowledged as important tools for enhancing development across various sectors of the economy (Heo & Lee, Citation2019; Ponelis & Holmner, Citation2015; Roztocki et al., Citation2019; Walsham & Sahay, Citation2006). In the agricultural sector, which forms a high share of the economy in most developing countries, ICTs have been deployed in two main areas. First, they have been applied in providing agricultural extension advice (Cole & Fernando, Citation2012; Jain et al., Citation2015; Nakasone et al., Citation2014). In this case, ICTs reduce the unit cost of communication and information sharing as compared to the traditional means of agricultural extension. Several studies have indicated that the use of ICTs has led to an increase in awareness and adoption of suitable agricultural technologies and practices resulting in increased yields (Casaburi et al., Citation2014; Cole & Fernando, Citation2012; Cole & Fernando, Citation2016; Nakasone et al., Citation2014). Secondly, ICTs have been utilized to facilitate the dissemination of market price information and subsequently improved farmers` bargaining power (Lio & Liu, Citation2006). Other studies have reported better prices, decreases in transaction costs, reductions in price dispersion and elimination of waste (Arinloye et al., Citation2015; Jensen, Citation2007; Nakasone, Citation2013; Svensson & Yanagizawa, Citation2009). ICTs have also been used for dissemination of weather data (Camacho & Conover, Citation2010; Fafchamps & Minten, Citation2012), collecting agricultural data (Daum et al., Citation2018; Dillon, Citation2012), and supporting on-farm activities including fertilizer application, irrigation, pest and disease control, and farm management (Bueno-Delgado et al., Citation2016; Carmona et al., Citation2018; Lantzos et al., Citation2013; Vellidis et al., Citation2016). Despite the contribution of ICTs in agricultural development, the literature also highlights several potential constraints to the use of ICTs, especially in developing countries. This includes but is not limited to: inadequate ICT infrastructure, lack of ICT skills, unreliable network connectivity and power supply problems (Akpabio et al., Citation2007; Dillon, Citation2012; Saidu et al., Citation2017).

The above literature illustrates how ICTs for agricultural development have focused more on the dissemination of agricultural extension messages, market and weather information than on strengthening agricultural extension systems for accountability.

2.3. Potential of using ICTs to strengthen accountability in public agricultural extension services

The existing literature highlights some ICT initiates regarding strengthening accountability in public services that employ large numbers of rural-based field staff. In education, for example, Duflo and Hanna (Citation2005) reported on an intervention that used cameras to monitor the attendance of teachers in rural India. The time and date stamps on the photographs provided evidence for attendance, which was later used to compute financial incentives for the teachers. The intervention resulted in an immediate decline in teacher absence. In another study, an SMS based monitoring system was piloted in Uganda. Monitors, who were either head teachers or parents, reported teacher attendance via SMS. Results indicated that both monitoring schemes understated the teacher absenteeism and thus stricter protocols to discourage under-reporting were suggested. Nonetheless, monitoring by head teachers with bonus payments increased teacher attendance (Cilliers et al., Citation2014). Similarly, a prototype system that used a combination of voice-biometrics and location tagging was developed for low-cost remote attendance tracking of teachers or health workers in developing regions. The evaluation of the system suggested that it could be a useful tool for tracking attendance (Reda et al., Citation2011).

In the health sector, WhatsApp mobile messaging was used to enhance the supervision of health services in Kenya. Through a WhatsApp group, community health workers documented their activities, with photos constituting the majority of evidence. The results demonstrated that WhatsApp messaging was useful in the supervision of health services (Henry et al., Citation2016). In Zambia, a mobile phone-based management information system was developed for community health workers and their supervisors. The platform used basic mobile phones to provide real-time, information from community health workers to their immediate supervisors and higher levels of the health system. Through the system, the supervisors tracked the reports from the community health workers and provided feedback. Results indicated that using basic phones was feasible for reporting, but smartphones and computers would be needed for data analysis and visualization (Biemba et al., Citation2017). Similarly, Modi et al. (Citation2015) piloted a mobile phone and web application designed to improve the delivery of health services by accredited social health workers in India. The health workers would log into the application, review their daily schedule, complete assigned tasks and report the completed tasks. The supervisors were then expected to log into the web interfaces to supervise and support the health workers. The application was also found to be largely acceptable, feasible, and useful.

Efforts have also been made in the agricultural sector. However, the focus has mainly been towards collecting the beneficiaries’ feedback and less on enhancing the supervision of extension activities. For example, Farm Radio International explored the potential of using interactive radio to capture farmers’ feedback. This was through the Listening Post model, which combined interactive radio broadcasts with an interactive voice response system that collected and aggregated real-time feedback from farmers. The findings indicated that the model had the potential to strengthen the beneficiaries’ voice (Gilberds et al., Citation2016). Similarly, Jarvis et al. (Citation2015) piloted an automated voice-surveys platform to obtain feedback from beneficiaries. The pilot showed that the ICT approach provided near real-time feedback and was more cost-effective for monitoring compared to traditional methods.

The above review demonstrates that there is great potential for the application of ICTs in strengthening public accountability. This brings into perspective the prospects of using smartphone applications in the supervision and monitoring of agricultural activities upon which this study was premised.

3. Research methods

3.1. Research design

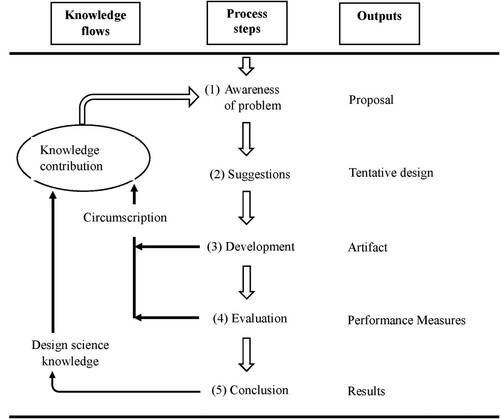

The study was conducted in a joint project between the University of Hohenheim, Germany and the Ministry of Agriculture, Animal Industry and Fisheries of Uganda (MAAIF). The study was conducted using the Design Science Research approach, which has its roots in the sciences of the artificial (Simon, Citation1996). Design Science Research is based on the ‘build and evaluate’ cycle, which consists of building an artifact and testing it, with iterations, before a final artifact is developed (Adomavicius et al., Citation2008; March & Smith, Citation1995). Design Science Research enables the researchers to design artifacts (in this case the e-diary) that are applied to solve problems in organizations and society in general (Hevner & Chatterjee, Citation2010). Hence, applying the Design Science Research approach to this study provides insight into what it takes to design ICTs for development that address actual problems. In this paper, we apply the Design Science Research process framework (see ) developed by Vaishnavi and Kuechler (Citation2007), which comprises five stages: (1) Awareness of the problem, which involves identifying and defining the research problem; (2) Suggestion, which includes suggesting a solution to the problem; (3) Development, which involves transforming the solution (a tentative design) into an actual artifact; (4) Evaluation, in which the artifact is evaluated, iterated and refined. (5) Conclusion, which is the end of the research cycle. In the conclusion stage, the overall contribution of the research project to advance knowledge in the research area is presented. Thus, based on the ‘build and evaluate’ cycle, the study was conducted in two phases using the 5-stage framework. The two phases included designing of the e-diary and evaluation of the e-diary.

Figure 1. Design Science Research process framework. Source: Adopted from Vaishnavi and Kuechler (Citation2007).

3.1.1. Designing of the e-diary

In this phase, which comprised stages one to three of the framework, the e-diary was developed. The phase commenced with the awareness of the problem stage, in which weak accountability was identified as a constraint to the functioning of public agricultural extension services, as outlined in section 1.

Then, in the suggestion stage, the use of diaries and ICTs was identified as a potential solution to the accountability problem (see section 2.3.). A diary was therefore designed to strengthen accountability in the public agricultural extension services. The first version was a diary in a paper format and was adopted by the Ministry of Agriculture, Animal Industry and Fisheries of Uganda.

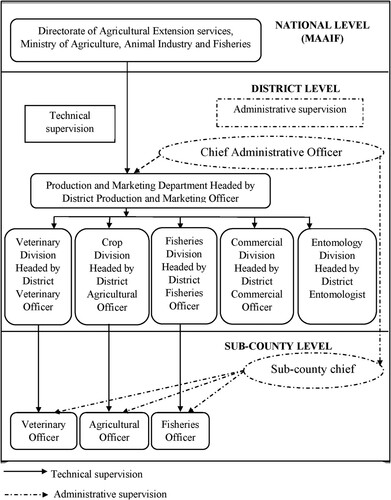

During the following development stage, the paper version was then transformed into an electronic diary (‘e-diary’) prototype. The design was structured along the hierarchical arrangements upon which the agricultural extension service of the Ministry of Agriculture, Animal Industry and Fisheries of Uganda is organized. The structure is organized at three levels: the national, district, and sub-county levels (see ).

Figure 2. Uganda’s Agricultural extension structure. Source: Adopted from MAAIF (Citation2015).

3.1.2. Evaluation of the e-diary

3.1.2.1. Piloting the e-diary

In the second phase, which comprised the fourth and fifth stages of the framework, the e-diary was evaluated. In stage four, a dry run of the e-diary prototype was conducted. The purpose of the dry run was to test for the functionality of the e-diary to mitigate the possibility of failure. The dry run was conducted in one randomly selected district out of the 122 districts of Uganda as of the time of the study. Two of the thirteen sub-counties in the selected district were randomly selected for the dry run. The participants from the district included; the Chief Administrative Officer, District Production and Marketing Officer and subject matter specialists. The Chief Administrative Officer is responsible for the administrative supervision of all government activities in the district while the District Production and Marketing Officer is responsible for the technical supervision of all agricultural extension services within the district. The subject matter specialists are the immediate technical supervisors of the field agents and they include: District Veterinary Officer, District Agricultural Officer, District Fisheries Officer, District Commercial Officer, and District Entomologist. The participants from the sub-county included the sub-county chiefs (one from each of the selected sub-counties) and the three field agents per selected sub-county (Agricultural Officer, Veterinary Officer and Fisheries Officer). The sub-county chiefs are responsible for the direct administrative supervision of the field agents, who are then responsible for delivering agricultural extension services within the sub-county (Agricultural Officers, Veterinary Officers and Fisheries Officers responsible for crop services, veterinary services, and Fisheries services, respectively). The dry run was conducted for two days. This involved a one-day training in which the field agents and supervisors were first separately trained on their respective interfaces, after which a joint training was conducted. The second day involved the users applying the e-diary and thereafter, providing feedback on its functionality, content and features. The feedback was used to improve the e-diary.

Following the dry run, the e-diary was piloted in two other districts that were randomly selected out of the remaining 121 districts. The pilot was conducted for 69 days between April and July 2019, and all the field agents in these districts and their respective supervisors were considered. shows the number of staff per district. Also, five supervisors from the Directorate of extension services of MAAIF were involved in the pilot. The officers from MAAIF include the Principal Agricultural Extension Coordinators-Livestock, Crops and Fisheries, each responsible for the supervision of extension services in the respective subject matter. The Principal Agricultural Extension Coordinators are under the headship of the Commissioner Agricultural Extension Services, who is supervised by the Director Agricultural Extension Services. The director is responsible for the management and coordination of all extension services in the country.

Table 1. Number of staff per district.

All users were first trained on the e-diary before its administration. Since the e-diary had different categories of users (field agents, sub-county chiefs, technical supervisors), the training was conducted stepwise. At first, each category of the users was separately trained in their respective interfaces. Subsequently, joint training was conducted for all the users since the different interfaces are interlinked. Each training comprised both theoretical and practical sessions. Whereas the theoretical sessions were intended for the users to understand the background of the e-diary and its purpose, the practical sessions were intended for hands-on experience prior to the use of the e-diary. During the practical sessions, the users practiced and explored the different features of the e-diary as they asked questions where they needed clarity. After the training, the users practiced with the e-diary in the field for three days, after which the actual recording of activities started. During the pilot, data was obtained in the form of feedback from the different categories of users. The feedback was in the form of perceptions and experiences of using the e-diary.

The feedback was used to modify and refine the e-diary to produce the finalized version which is described in section 4.1. One of the major modifications was the introduction of an offline component for the recording of the daily activities by the field agents. Modifications were also made to the wording in the e-diary to fit the commonly used vocabulary in the day to day activities of the users. For example, the word ‘My Objectives’ was replaced with ‘My Outputs’ and ‘costs’ with ‘budget.’ Additions were also made on the content of the e-diary, especially in regards to the activities that were to be filled in by the agents. Initially, the field agents were to choose from a list of activities that was developed based on the expected roles of the field agents. However, new activities were suggested by the field agents during the pilot and they were also included. It was noted that the field agents occasionally forgot to activate the GPS location on the device while they filled in their daily activities. Thus, the e-diary was modified such that it can only be started if the GPS location is activated. Additionally, it was noted that the field agents sometimes conduct activities outside their areas of jurisdiction (sub-counties). For example, farmer exchange visits or farmer trade shows, where farmers are taken to other sub-counties or districts. Consequently, the location in the e-diary was modified to accommodate other places outside the sub-counties, unlike the original design which restricted the agent to only report activities within their sub-county. Furthermore, it was reported that sometimes the field agents conduct activities outside their work plans, especially in cases of emergencies like disease outbreaks. As such, a new provision was created to allow for the recording of unplanned daily activities unlike in the original design were only planned activities were considered. However, a safeguard was included so that the agent had to justify each unplanned activity.

Finally, in the conclusion stage, the feedback obtained from the users was also used to assess the potential of the e-diary for strengthening accountability (see section 4.2). The overall contribution of the research to the body of knowledge and the practical implications were also highlighted (see section 6.).

3.1.2.2. Data collection

Data for the evaluation of the e-diary was collected through a combination of focus group discussions and individual face-to-face interviews, both of which are methods used to collect qualitative data (Berg & Lune, Citation2012). The focus group discussions were conducted for field agents, sub-county chiefs and district-level supervisors. For the field agents, only those that used the e-diary to report daily activities were considered. The individual interviews were conducted for the supervisors at MAAIF. However, since each of the two districts had recruited only two Fisheries Officers, they could not be considered for the focus group discussion. Instead, they were invited for individual interviews. shows an overview of the number of focus group discussions and individual interviews conducted per category of users of the e-diary. In addition to the interviews, a joint workshop aimed at obtaining joint feedback from all users of the e-diary was conducted in each of the pilot districts.

Table 2. Overview of interviews conducted with the users of the e-diary.

3.1.2.3. Data analysis

The data obtained was transcribed and analysed using the content analysis method (Holsti, Citation1968). The content analysis method enables analysis of qualitative data through the assigning of codes to texts and then transforming the codes into common themes (Elo & Kyngäs, Citation2008). Accordingly, the perceptions and experiences of the different categories of users were used to develop the finalized version of the e-diary and to identify common themes with a particular focus on the potential opportunities and challenges of using the e-diary for strengthening accountability in the public agricultural extension services. Furthermore, descriptive statistics on how field agents used the e-diary to report their daily activities were compiled.

4. Results

4.1. E-diary architectureFootnote1

4.1.1. User interfaces

The e-diary has two categories of users. The first are the ‘field agents’: Agricultural Officers, Veterinary Officers and Fisheries Officers. The second category of users are the ‘supervisors.’ They include the supervisors from the sub-county (sub-county chiefs), district (subject matter specialists, District Production and Marketing Officer, and Chief Administrative Officer), and the Directorate of Agricultural Extension Services (Principal Agricultural Extension Coordinators-Livestock, Crops and Fisheries, Commissioner Agricultural Extension Services and Director Agricultural Extension Services).

The different actors have different user interfaces that upload information into a central database where all the data is compiled. The user interfaces for the field agents are smartphone-based (Android OS), while the supervisors’ are web-based. The different interfaces are interlinked, such that the information filled in by the subordinates is reflected on the interfaces of the respective supervisors and vice versa.

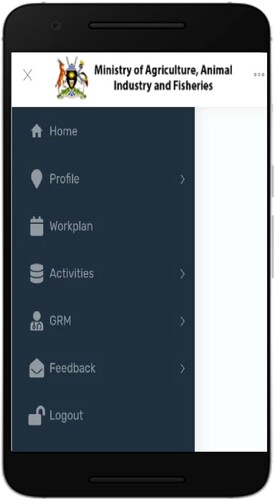

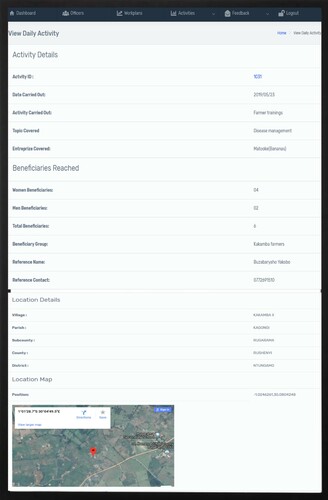

All interfaces were designed in adherence to the existing agricultural extension service delivery procedures to ensure that the e-diary aided rather than conflicted with the existing processes. The procedures start with planning, which is followed by conducting the planned activities, reporting, monitoring, evaluation and feedback. These procedures are reflected in the features of the interfaces. The interface of the field agents (see ) shows the following features: profile (field agent profile, area profile), work plan (annual work plan), my activities (view quarterly planned activities, add daily activities, view daily activities and evaluation), feedback (compose messages, inbox and sent messages to respective supervisors) and GRM (a Grievance Redress Mechanism intended to be linked to a public app such that the field agents can monitor the grievances of the beneficiaries and respond to them).

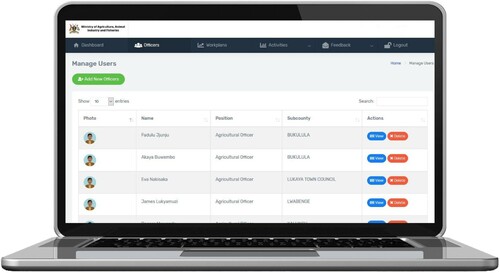

The interfaces of the supervisors within the district are a reflection of the interfaces of the field agents. As shown in , the district supervisors’ interfaces highlight the profiles, work plans and activities of all field agents supervised. The structure of the interface of all the district supervisors is similar. The only difference is that for each supervisor, the content reflected is from only the field agents supervised. For example, in , the interface for the District Agricultural Officer shows profiles and content from only the Agricultural Officers in the district. Similarly, the sub-county chiefs’ interface reflects content only from the three field agents within the sub-county. Since the District Production and Marketing Officer, and the Chief Administrative Officer supervise the entire district, their interfaces reflect content from all the subject matter specialists within the district regardless of the subject matter.

The interfaces for the supervisors at MAAIF headquarters take on the same structure as that of the supervisors from the district. The exception is that the content captured at MAAIF is from all districts in the country. Just like the district supervisors, the supervisors at MAAIF also see information based on their subject matters. The interfaces of the Principal Agricultural Extension Coordinators-Livestock/Crops/Fisheries reflect content from their respective subject matter specialists. Since the Commissioner and the Director Agricultural Extension Services coordinate all extension services in the country, their interfaces reflect content from all the subject matters.

4.1.2. How the e-diary works

The user of the e-diary must have an e-diary account, which is protected by a user name and password. Each supervisor creates the account for the immediate subordinate. As earlier noted, the e-diary works within the existing agricultural extension procedures such as planning, conducting of activities, reporting, monitoring, evaluation and feedback. The planning is annual and results in the formulation of annual work plans. However, the funds to conduct activities are released every quarter (every three months), and therefore the work plan is implemented quarterly. The e-diary was thus designed based on these processes.

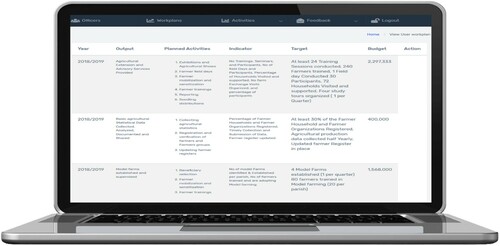

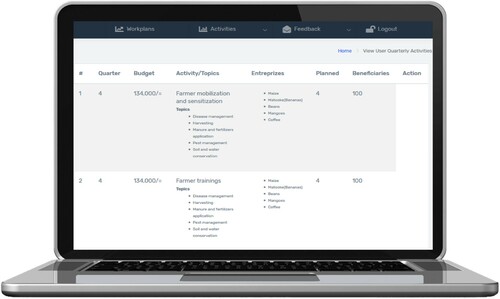

At the beginning of each financial year, the field agent, together with the respective subject matter specialist, plan and agree on the activities to be conducted that year. Through this process, the annual work plan of the field agent is formulated. The content of the annual work plan includes; outputs, key indicators, targets, activities to be carried out and budgets to be allocated to each activity. Subsequently, the subject matter specialist uploads the agreed-on field agent’s annual work plans into the e-diary via the subject matter specialists’ account (see ). The annual work plan is then reflected on the account of the field agents as well as other supervisors at different levels. At the beginning of each quarter, the field agent together with the subject matter specialist select from the annual work plans the quarterly activities to be carried out. These quarterly activities are further broken down into topics, enterprises, activity budget, the number of times the activity is planned to be carried out and the number of target beneficiaries. The subject matter specialist further uploads the selected quarterly activities into the e-diary (see ). During the quarter, the field agent logs into their account, reviews the planned quarterly activities and selects daily activities. Subsequently, the field agent conducts and reports the completed daily activities. Through their accounts, the supervisors can track the daily activities of the field agents, thereby holding them accountable.

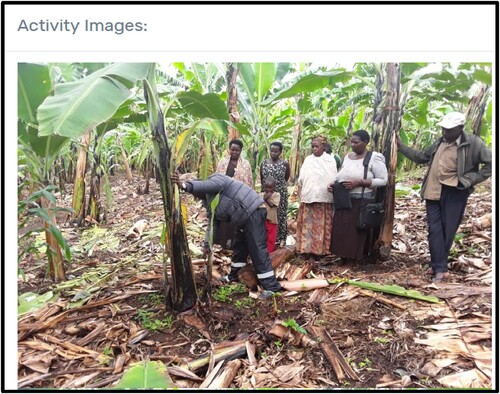

The e-diary is embedded with special accountability features to enable the supervisors to verify the reported daily activities of the field agent. These include a beneficiary verification mechanism, location of activity and activity photos. Regarding the beneficiary verification mechanism, for each activity, the field agent has to record the name and phone number of the beneficiary or reference beneficiary in the case of a group. Using the captured phone numbers, the supervisor can call the beneficiaries and verify the field agent’s visit. For the location, the field agent has to record the name of the village in which the activity was conducted. In addition, the system automatically captures the GPS coordinates, which verify the location entry. Concerning the activity photos, the field agent has to attach at least one activity photo that also provides evidence of the reported activity. and show how the accountability features are tagged to the daily activities.

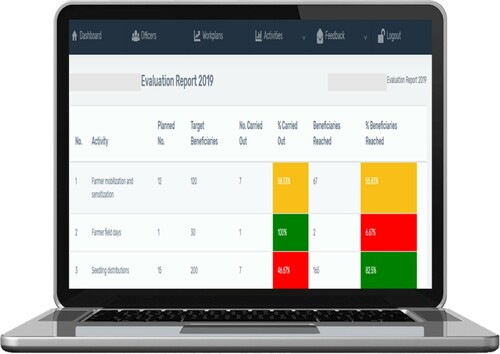

To facilitate evaluation, at the end of each quarter, an automatic summary report of the field agent’s activities is generated. The report highlights the activities conducted, topics and enterprises covered, locations visited and the number of beneficiaries reached. While the field agent’s report focuses only on the activities carried out by the individual agent, the supervisor’s report further computes activities from all agents supervised. Furthermore, an automatic quarterly performance evaluation of the field agent’s activities is generated. The evaluation, which is in table form, presents the percentages that are generated by comparing the completed against the planned activities, beneficiaries and budget. shows an example of an evaluation summary.

The e-diary also allows for feedback from the supervisors to the field agents. The field agents can send and receive messages from their immediate supervisors, who can also send and receive messages from their superiors. This facilitates communication regarding extension activities, thereby improving service delivery

4.2. Perceptions and experiences of the users on the e-diary

To evaluate any system, it is important to understand the users’ perceptions and experiences about the system, and whether the system meets the users’ requirements. This facilitates user acceptance and therefore buy-in. This section presents the findings on the perceptions and experiences of the users from both the field agents and their supervisors. The findings highlight the perceived benefits and challenges of using the e-diary for strengthening accountability in the public agricultural extension services. The findings show that the main benefits of the e-diary included: ease of use, convenience, real-time reporting and centralized online evidence. The major challenges highlighted included poor network connectivity and lack of electricity access. shows the magnitude of the perceived benefits and challenges based on the number of respondents that mentioned the respective benefit or challenge.

Table 3. Perceptions and experiences of the users of the e-diary.

4.2.1. Ease of use

The e-diary was reported to be an easy to use tool, which saves effort and time in the reporting and supervision of the extension activities. The majority of the field agents (82.7%), as well as their supervisors (80.8%), commended the e-diary for being easy to use. Ease of use was expressed in terms of the simplicity of the interfaces, content, language and mode of operation. The field agents reported that it took them very little time to familiarize themselves with the e-diary since their interface was easy to navigate and the content simple to understand. They were mainly satisfied by the ease with which they reported the daily activities, which were already preloaded in the system based on the annual work plans. Reporting of daily activities was done by selection from a drop-down list of activities, topics and enterprises. This simplified the use of the e-diary as reflected in the following statement by one of the field agents:

The e-diary is user-friendly as it is easy to fill. It is just a click and go. I just select an activity and, in a few minutes, everything is captured. There is not so much typing needed, unlike the cumbersome paper reporting.

In the beginning, when I heard that the reporting was going to become electronic, I was worried given the fact that I am not good with ICTs. However, after the training and using the app in the field, I realized that it is an easy tool.

4.2.2. Convenience in reporting and supervision

The majority of the field agents and supervisors found the app convenient for reporting and supervision of activities, respectively. The field agents expressed convenience in terms of portability of the smartphone. They liked the idea of having the work plans and reporting of their daily activities on a mobile phone, which they claimed to carry with them most of the time. One field agent stated;

I am happy that we are moving away from carrying books to the field because they are bulky. Everything with the e-diary is on the phone, which is portable. The e-diary eliminates the process of first writing down the different activities and then compiling reports. Everything is compiled in the system. Secondly, unlike with the paper-based reporting were all information is lost once the books are misplaced, I have noted that with the e-diary, I can install the app on another phone and access my data.

Monitoring is now only a mouse click away. Before the e-diary, we had to travel to different locations to be able to follow up on the reported extension activities. This was more expensive and also required more time since we deal with many agents who work in large sub-counties. The e-diary is a simple way of monitoring the activities without having to run after the field agents. We can verify the reported activities using the phone numbers of the registered farmers, the GPS, which captures the location of the activity and the activity photos. One photo speaks more than a thousand words.

4.2.3. Real-time reporting

The e-diary was also commended for its real-time reporting since the daily activities were uploaded immediately after they were conducted. Real-time reporting facilitates immediate supervision and, therefore quick feedback from the supervisors to the field agents. One field agent stated:

The app captures firsthand information. There is no time lag between conducting an activity and reporting it. At the end of each day, the supervisor can see what is happening on the ground. It is better than writing a report which takes days or even months to reach the ministry. The timely reporting helps the field agent to get immediate feedback from the supervisor.

The advantage of this e-diary is that I can get the information in real-time. Even simple statistics of how many beneficiaries have been reached in a day are generated instantly. When I want to see what my officers have done today, I just check on the system and advise them immediately and if there is an emergency, I handle it immediately.

4.2.4. Centralized online evidence of activities

Most of the field agents (86.5%) were pleased that the e-diary provided an online proof for their field activities. It was highlighted that often, the beneficiaries deny the reported field activities when supervisors go to verify. However, with the evidence in the e-diary database, the GPS coordinates and activity photos, the field agents could easily prove their activities. One of the field agents stated:

Sometimes farmers claim that we are not on the ground especially when they need favours from our supervisors or politicians. However, with the e-diary, within a few minutes, we can prove to the entire nation that we are working. For example, attaching an activity photo shows proof that the activity was conducted. The GPS also shows that the agent was in the sub-county.

Since we have so many farmers in the sub-county, sometimes it is not possible to reach all of them. Therefore, some of the farmers may claim that we are not working. This e-diary shows that even if I am not able to reach all farmers, at least I try to reach those I can, given the available means.

4.2.5. Poor network connectivity

At the start of the pilot, poor network connectivity was reported by the majority (80.8%) of the field agents. Due to the remoteness of their work areas, the poor network connections interfered with the reporting of the daily activities. However, this was managed by introducing a component that allowed for the offline recording of the daily activities. The application would then automatically synchronize the captured daily activities with the online system once a connection was received.

4.2.6. Inaccessibility to electricity

The e-diary was also reported to be affected by the challenge of inaccessibility to electricity. The field agents emphasized that they operate in rural areas, some of which do not have access to electricity yet the e-diary operates on mobile phones, which need to be charged.

4.3. User statistics for the reporting of daily activities by the field agents

The results in this section were obtained by monitoring the activities of the field agents using the e-diary. Additionally, WhatsApp platforms were created to provide feedback on how the field agents reported the activities, and the effect of the feedback on the reporting monitored.

4.3.1. Descriptive statistics for the use of the e-diary for reporting daily activities

The statistics showed that the majority of the field agents (52 out of 56) were able to report at least one daily activity in the e-diary. However, no field agents reported on each of the 69 days of the pilot. The maximum number of days that a field agent reported daily activities was 38 days, the minimum was one day, the average was 17 days and the median also 17 days. When asked why reporting was not done every day, the field agents revealed that they reported mainly on days that they conducted field-based activities and did not report office-based activities. This was because most of the activities budgeted for in the work plans were field-based. For the four field agents that did not report any daily activity, one went on sick leave, and the other three reported to have been hindered by technical problems with the phones that they used. However, they still did not report any activity after receiving different phones. The failure to report daily activities using the e-diary could have been due to the absence of sanctions for failure to report.

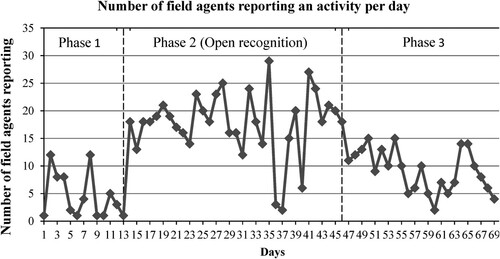

4.3.2. Effect of open recognition on reporting of daily activities

During the pilot of the e-diary, a mechanism was designed to test the effect of open recognition on the reporting by the field agents. This involved the creation of WhatsApp groups for each of the participating districts. The WhatsApp groups comprised of all categories of users of the e-diary in the district, MAAIF supervisors and researchers. In the WhatsApp group, recognition was given to the field agents that reported the daily activities more consistently, while those who were inconsistent or not reporting at all were queried. The effect of this mechanism on the reporting of daily activities is demonstrated by three phases that are shown in . During phase 1, which marks the period when the field agents started reporting daily activities, there was no open recognition. Hence, reporting of the daily activities was at a low level. However, the rate of reporting increased during phase 2 in which open recognition was continuously done. The rate of reporting remained consistently higher throughout phase 2, with the exception of a drastic drop between days 36- 40. This period was the first week of a new financial year, during which the field agents were doing more of the office activities in preparation for the field activities for the new financial year. Just like in phase 1, the rate of reporting went down and remained consistently lower in phase 3 when the open recognition had stopped. It can thus be argued that open recognition of the field agents that reported the daily activities more consistently, together with the querying of those who were inconsistent or not reporting at all, was an incentive for the field agents to use the e-diary for reporting of daily activities.

5. Discussion

5.1. Potential of the e-diary for strengthening accountability in public agricultural extension services.

The results indicate that the e-diary has the potential to strengthen upward accountability in public agricultural extension services. These findings make a unique contribution to the use of ICT for development purposes since, to our knowledge, hardly any study has assessed the potential of using ICTs, particularly, smartphone applications for strengthening the accountability of public agricultural extension services, which are key for rural development. To date, most studies on ICT for agricultural development have focused on the dissemination of information (Arinloye et al., Citation2015; Fafchamps & Minten, Citation2012; Jain et al., Citation2015; Nakasone et al., Citation2014). The findings point to a unique opportunity of using ICTs to improve effectiveness in a sector constituting large numbers of field agents working with dispersed clients. However, the findings are also of relevance for the provision of other public services, like health and education, where field agents are stationed in one location.

The findings suggest that the e-diary has the potential to strengthen upward accountability in two ways: (1) It permits remote or distant supervision of the extension activities and (2), it enables real-time reporting and supervision of the extension activities.

Regarding remote/distant supervision, the e-diary is embedded with features (GPS, activity photo and a beneficiary verification mechanism), that enable supervisors to remotely follow-up the activities of the field agents. The GPS captures the actual location for which a particular activity is reported, therefore enabling the supervisors to track the activities of the different field agents conducted in different locations without necessarily traveling to those locations. The activity photo also provides additional evidence for the type of activity conducted as also reported by Duflo and Hanna (Citation2005) and Henry et al. (Citation2016), who found that photos constituted the major evidence in the supervision of teachers and health workers respectively. In addition, the beneficiary verification mechanism, which captures the phone numbers of the beneficiaries, can be used by supervisors to verify agents’ reported activities as earlier suggested by Aker (Citation2011) and Aker et al. (Citation2016). This finding validates the supposition that smartphone applications can provide platforms that enable remote supervision (DeRenzi et al., Citation2011). By enabling remote supervision, the e-diary eliminates the travel costs and time needed to physically supervise large numbers of field agents working in remote, widely dispersed geographic areas. Hence, it facilitates more effective supervision and thus accountability.

In regards to real-time reporting and supervision, the e-diary enables the supervisors to get real-time reports from the field agents and subsequently immediate feedback from the beneficiaries. This finding corroborates the suggestion that mobile tools can enable the supervisors to monitor the activities of the field agents in near real-time and provide immediate feedback or immediate interventions were necessary (DeRenzi et al., Citation2011). According to Omisore (Citation2014), daily reporting by subordinates enables the supervisors to monitor the productivity of the subordinates consistently. Consequently, increasing the effectiveness of supervision and subsequently accountability.

5.2. Limitations of implementing the e-diary

Despite its unique potential for strengthening accountability, the results revealed that incentives are necessary to motivate the field agents to report in the e-diary. As observed, the open recognition of the field agents who reported more consistently against those who were inconsistent or not reporting at all, increased the number of field agents reporting per day. The open recognition was via WhatsApp groups but a more automated mechanism could be created within the e-diary. Furthermore, the incentive to report could even be higher if the recognition is coupled with rewards for those reporting more consistently and sanctions for those not reporting. Such rewards could include: employee awards of recognition, promotion opportunities, career development and financial benefits such as bonus payments (Armstrong, Citation2010; Bitzer, Citation2016). The expectancy theory suggests that staff are more likely to be motivated when they believe that their efforts will be rewarded (Vroom, Citation1964). This finding is in line with Duflo and Hanna (Citation2005) and Cilliers et al. (Citation2014), who found that coupling monitoring with (financial) incentives was needed to increase teacher’s attendance.

The results also showed that the e-diary could be limited by inaccessibility to electricity as most field activities are conducted in rural areas, sometimes with no access to electricity. This is in line with studies that have reported power supply problems as a constraint to the implementation of ICTs in other developing countries (Akpabio et al., Citation2007; Dillon, Citation2012; Saidu et al., Citation2017). Providing power banks or solar chargers to field agents may help to overcome this challenge.

Another limitation of the e-diary is that it focuses on whether or not the field agents conducted activities. While this is a major advancement, this ignores the quality of the activities conducted. Further, the e-diary mostly addresses upward accountability. While there are some elements to enhance downward accountability, for example, the beneficiary verification mechanism through which the supervisors can obtain feedback from the registered beneficiaries, there is no inbuilt mechanism that enables the beneficiaries to automatically verify the reported activities and rate the quality of services received.

5.3. Potential of expanding the e-diary

5.3.1. Modification of the e-diary with new features

As highlighted under the limitations section, the e-diary mainly focuses on strengthening upward accountability. However, it could further be improved to also strengthen downward accountability. Future studies could incorporate a mechanism that enables the beneficiaries captured in the e-diary to automatically verify the reported activities and to rate the quality of services received. For example, after service delivery, short text messages (potentially using simple icons) may be sent to the beneficiaries that were visited by the field agents to ask them to anonymously verify the reported activities and rate the quality of the service. This could be in combination with a voice response system which allows the beneficiaries to leave a voice message. Using icons and voice response systems would ensure that beneficiaries who cannot read or write can also evaluate the field agents. The system can then automatically generate an aggregate rate for each field agent, which is received by the supervisor in addition to the voice message. Automated response systems have been found to provide near real-time feedback and were more cost-effective for monitoring compared to traditional methods (Gilberds et al., Citation2016; Jarvis et al., Citation2015).

Regarding supporting the routine of the field agents in addition to strengthening accountability, the e-diary could be embedded with a crisis surveillance mechanism. This could be in the form of alert notifications by which field agents inform supervisors about crises such as pest and disease outbreaks and natural disasters such as floods and landslides. A similar mechanism by which field agents send daily activities could be explored such that the field agents send photos of the crises with the GPS location automatically captured. A study by Quinn et al. (Citation2011) demonstrated that camera phones can be useful in monitoring the spread of pests and diseases.

Furthermore, a new command button for a stakeholder profile could be created under the area profile in the e-diary. This would enable the field agents to register important stakeholders, for example, the non-state agricultural extension service providers, input dealers and farmer groups in their sub-counties. At the time of the study, the existing farmer groups in each sub-county had been manually profiled and manual registration for the new groups was still ongoing (MAAIF, Citation2017). However, electronic systems have been found to be simpler and more timely in terms of data receipt, data management and the formation of databases (Hufford et al., Citation2002; Lane et al., Citation2006; Quinn et al., Citation2003). Thus, using the e-diary for profiling the relevant stakeholders could simplify the process of stakeholder profiling.

There is also a possibility of including a new interface for the financial office to follow up with the financial accountability for the different activities reported in the e-diary. When the study was conducted the field agents were submitting paper receipts of the funds spent under each activity alongside a paper-based report to the financial office for accountability. The e-diary could simplify this process by enabling the field agents to upload scanned copies of receipts under each daily activity via the same mechanism used to upload daily activity photos. This could simplify the flow and management of the agricultural extension funds.

5.3.2. Linking the e-diary to other ICT tools

Regarding links to other ICT tools, the e-diary has so far been linked to another application called ‘MAAIF E-GRM’ which is locally built on the same platform. This was via the GRM (Grievance Redress Mechanisms) command button created on the interface for the field agents. The MAAIF E-GRM is being developed by MAAIF to enable the public to report on Grievances arising from agricultural extension projects. By linking the e-diary to MAAIF E-GRM, the field agents can obtain beneficiary feedback via the e-diary once the MAAIF E-GRM is implemented. This could further be linked to the supervisors’ interfaces such that they too could access the beneficiaries’ feedback on the different agricultural projects. Studies by Jarvis et al. (Citation2015) and Gilberds et al. (Citation2016) have shown that beneficiary feedback obtained from the use of ICT tools has the potential to enhance the impact of agricultural projects. Thus, linking the e-diary to the beneficiary feedback could be an incentive for the field agents to use the e-diary.

The e-diary could also be linked to the ‘E-extension and Advisory system for MAAIF,’ another tool built on the same platform, which is designed to generate and disseminate agricultural information to beneficiaries. Linking the E-extension and Advisory system to the e-diary will enable the field agents to have easy access to the generated agricultural information, which they can refer to while conducting field activities.

The e-diary could also be linked to other relevant platforms outside MAAIF. This can be via Application Programming Interface-(API) which facilities automatic communication between the e-diary and other platforms. For example, through collaborations between MAAIF and the meteorology center, the e-diary could be linked to weather forecast platforms, and that would enable the field agents to access weather data which they can use to guide the beneficiaries’ activities. The e-diary could also be linked to market information platforms, which would enable the field agents to get easy access to market information such as market prices. This information can be used by the field agents to guide the beneficiaries on where to sell their produce.

6. Contribution to the literature and practical implications for socioeconomic development

The findings of this study provide significant contributions to both research and practice on the use of ICTs for strengthening public (and private) services, in both developing and developed countries. While several studies have demonstrated the potential of ICTs to enhance farmer’s access to information on agricultural technologies, weather and markets, among others, few studies have assessed the potential of ICTs to strengthen public services that are key for farmers. Moreover, while a great body of literature has focused on the use of ICTs to strengthen supervision and accountability in public services, these studies have been limited to education and health, making it difficult to draw implications for agricultural extension services, which constitutes large numbers of field agents working with dispersed clients, that is, smallholder farmers. This study has identified several factors that are key when designing digital tools to create more accountability for such types of public extension services and has demonstrated that tools such as the e-diary, when coupled with incentive structures, can strengthen the management and performance of agricultural extension services. Improving the performance of the extension services has large implication for socioeconomic development as shown by the many studies that have demonstrated their role in enhancing farmer’s productivity. Since the majority of the world’s poor and hungry are farmers, this can help to alleviate poverty and ensure food security. In addition to being useful for public services, the developed e-diary (and the lessons derived from its assessment in this paper) could also be useful for private businesses that have field staff who provide services to farmers, such as agro-input companies. The developed e-diary and the experiences reported here could also be useful for other public services that have field staff, such as rural health and education services.

Conclusion

The study has shown that smartphone applications such as the e-diary, which record GPS data, make it possible to take photographs and enable beneficiary feedback, can strengthen accountability in public agricultural extension services. The experience with the ‘e-diary’ indicates that such smartphone applications enable remote supervision in real-time, which reduces the costs and time of supervision. This, increases the effectiveness of supervision and subsequently overcomes the challenges of absenteeism, shirking and moonlighting that are common in public systems. However, successful implementation of smartphone applications for purposes of strengthening accountability requires incentives in the form of rewards such as, awards of recognition. Furthermore, the implementation of smartphone applications in developing countries, especially in rural areas with limited access to electricity, requires the use of or power banks or solar chargers to enable the charging of smartphones. It is recommended that further research incorporates an automated mechanism within the e-diary that allows the beneficiaries to verify and rate the quality of services received. The experiences with the e-diary point to the significant and largely untapped potential of using digital tools to enhance the accountability of public services such as agricultural extension.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge and thank all the respondents who kindly shared valuable information. The authors also thank the reviewers for providing the comments which contributed to the improvement of the article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Angella Namyenya

Angella Namyenya is a Senior Agricultural Extension Coordinator at the Ministry of Agriculture, Animal Industry and Fisheries Uganda, where she also previously worked as a Farm Planning Officer. She holds a Ph.D. in Agricultural sciences (Agricultural Economics, Bioeconomy and Rural Development) from the University of Hohenheim, Germany. She also holds an M.Sc. in Agricultural and Applied Economics and a B.Sc. in Agriculture both from Makerere University. Her research interests include smart agricultural innovations especially the use of digital technology in Agriculture, accountability and management of agricultural extension services, agricultural policy, governance of agricultural institutions and the role of agriculture in rural development.

Thomas Daum

Thomas Daum is a research fellow at the Institute of Agricultural Sciences in the Tropics (Hans-Ruthenberg-Institute), University of Hohenheim, Germany. His research focuses on agricultural development strategies that are sustainable from an economic, social and environmental perspective. His work focuses, among other topics, on agricultural mechanization, digital agriculture and youth in agriculture in Africa and India. He studied Business Administration (B.A.) in Mannheim and Budapest and holds an M.Sc. and Ph.D. in Agricultural Economics from the University of Hohenheim. He is working as a freelance journalist for the ‘Süddeutsche Zeitung’ and the ‘Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung,’ among others.

Patience B. Rwamigisa

Patience B. Rwamigisa is the Assistant Commissioner Agricultural Extension Coordination in the Directorate of Agricultural Extension Services, at the Ministry of Agriculture, Animal Industry and Fisheries of the Republic of Uganda since 2016. He holds a Ph.D. in Agricultural Extension from Makerere University and his expertise is largely in agricultural extension reforms. He possesses 25 years of experience in agricultural extension service delivery and has provided technical leadership in the ongoing reform of agricultural extension services in Uganda. He has in the past served as an adjunct lecturer at the School of Veterinary Medicine and also as a guest lecturer at the School of Agriculture and Environmental Sciences, Makerere University. He also serves as an external examiner at the same University. He has made several publications on agricultural extension reforms in Africa.

Regina Birner

Regina Birner is the Chair of Social and Institutional Change in Agricultural Development at the the Institute of Agricultural Sciences in the Tropics (Hans-Ruthenberg-Institute), University of Hohenheim, Germany. Regina Birner specializes in the analysis of agricultural institutions, including extension services and has more than 20 years of conducting empirical research in developing countries. She has been consulting with international organizations, including the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD) and the World Bank. Regina Birner holds a Ph.D. in Socio-Economics of Agricultural Development from the University of Göttingen.

Notes

1 The app was programmed by Musoke Herbert Thomas Nsubuga, a professional programmer, who was hired as a consultant for the project.

References

- Adomavicius, G., Bockstedt, J. C., Gupta, A., & Kauffman, R. J. (2008). Making sense of technology trends in the information technology landscape: A design science approach. Mis Quarterly, 32(4), 779–809. https://doi.org/10.2307/25148872

- Aker, J. C. (2011). Dial “A” for agriculture: A review of information and communication technologies for agricultural extension in developing countries. Agricultural Economics, 42(6), 631–647. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1574-0862.2011.00545.x

- Aker, J. C., Ghosh, I., & Burrell, J. (2016). The promise (and pitfalls) of ICT for agriculture initiatives. Agricultural Economics, 47(S1), 35–48. https://doi.org/10.1111/agec.12301

- Akpabio, I. A., Okon, D. P., & Inyang, E. B. (2007). Constraints affecting ICT utilization by agricultural extension officers in the Niger Delta, Nigeria. Journal of Agricultural Education and Extension, 13(4), 263–272. https://doi.org/10.1080/13892240701630986

- Al-Hassan, R. M., Egyir, I. S., & Abakah, J. (2013). Farm household level impacts of information communication technology (ICT)-based agricultural market information in Ghana. Journal of Development and Agricultural Economics, 5(4), 161–167. https://doi.org/10.5897/JDAE12.143

- Anderson, J. R., & Feder, G. (2004). Agricultural extension: Good intentions and hard realities. World Bank Research Observer, 19(1), 41–60. https://doi.org/10.1093/wbro/lkh01

- Arinloye, D. D. A., Linnemann, A. R., Hagelaar, G., Coulibaly, O., & Omta, O. S. (2015). Taking profit from the growing use of mobile phone in Benin: A contingent valuation approach for market and quality information access. Information Technology for Development, 21(1), 44–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/02681102.2013.859117

- Armstrong, M. (2010). Armstrong's handbook of reward management practice: Improving performance through reward (3rd ed.). Kogan Page Publishers.

- Baumüller, H. (2018). The little we know: An exploratory literature review on the utility of mobile phone-enabled services for smallholder farmers. Journal of International Development, 30(1), 134–154. https://doi.org/10.1002/jid.3314

- Benin, S., Nkonya, E., Okecho, G., Randriamamonjy, J., Kato, E., Lubade, G., & Kyotalimye, M. (2011). Returns to spending on agricultural extension: The case of the National Agricultural Advisory Services (NAADS) program of Uganda. Agricultural Economics, 42(2), 249–267. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1574-0862.2010.00512.x

- Berg, B. L., & Lune, H. (2012). Qualitative research methods for the social sciences (8th ed.). Pearson.

- Biemba, G., Chiluba, B., Yeboah-Antwi, K., Silavwe, V., Lunze, K., Mwale, R. K., Russpatrick, S., & Hamer, D. H. (2017). A mobile-based community health management information system for community health workers and their supervisors in 2 districts of Zambia. Global Health: Science and Practice, 5(3), 486–494. https://doi.org/10.9745/GHSP-D-16-00275

- Birner, R. (2007). Improving governance to eradicate hunger and poverty. 2020 focus Brief on the World’s poor and hungry People. International Food Policy Research Institute.

- Birner, R., & Resnick, D. (2010). The political economy of policies for smallholder agriculture. World Development, 38(10), 1442–1452. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2010.06.001

- Bitzer, V. (2016). Incentives for enhanced performance of agricultural extension systems (KIT Working Paper) 2016, 6.

- Brinkerhoff, D. W. (2004). Accountability and health systems: Toward conceptual clarity and policy relevance. Health Policy and Planning, 19(6), 371–379. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czh052

- Bueno-Delgado, M. V., Molina-Martínez, J. M., Correoso-Campillo, R., & Pavón-Mariño, P. (2016). Ecofert: An Android application for the optimization of fertilizer cost in fertigation. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture, 121, 32–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2015.11.006

- Camacho, A., & Conover, E. (2010). The impact of receiving price and climate information in the agricultural sector. Documento CEDE, (2010-40).

- Carmona, M. A., Sautua, F. J., Pérez-Hernández, O., & Mandolesi, J. I. (2018). Agrodecisor EFC: First Android™ app decision support tool for timing fungicide applications for management of late-season soybean diseases. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture, 144, 310–313. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2017.11.028

- Casaburi, L., Kremer, M., Mullainathan, S., & Ramrattan, R. (2014). Harnessing ICT to increase agricultural production: Evidence from Kenya. Harvard University.

- Chaudhury, N., Hammer, J., Kremer, M., Muralidharan, K., & Rogers, F. H. (2006). Missing in action: Teacher and health worker absence in developing countries. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 20(1), 91–116. https://doi.org/10.1257/089533006776526058

- Cilliers, J., Kasirye, I., Leaver, C., Serneels, P., & Zeitlin, A. (2014). Improving teacher attendance using a locally managed monitoring scheme: Evidence from Ugandan Primary Schools. Rapid response paper.14/0189. International Growth Centre.

- Cole, S. A., & Fernando, A. N. (2016). The value of advice: Evidence from the adoption of agricultural practices. HBS Working Group Paper, 1(1.3), 6.

- Cole, S., & Fernando, A. N. (2012). The value of advice: Evidence from mobile phone-based agricultural extension. Harvard Business School working paper. 13-047.

- Daum, T., Buchwald, H., Gerlicher, A., & Birner, R. (2018). Smartphone apps as a new method to collect data on smallholder farming systems in the digital age: A case study from Zambia. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture, 153, 144–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2018.08.017

- Deichmann, U., Goyal, A., & Mishra, D. (2016). Will digital technologies transform agriculture in developing countries? The World Bank.

- DeRenzi, B., Borriello, G., Jackson, J., Kumar, V. S., Parikh, T. S., Virk, P., & Lesh, N. (2011). Mobile phone tools for field-based health care workers in low-income countries. Mount Sinai Journal of Medicine. A Journal of Translational and Personalized Medicine, 78(3), 406–418. https://doi.org/10.1002/msj.20256

- Devas, N., & Grant, U. (2003). Local government decision-making citizen participation and local accountability: Some evidence from Kenya and Uganda. Public Administration and Development, 23(4), 307–316. https://doi.org/10.1002/pad.281

- Dillon, B. (2012). Using mobile phones to collect panel data in developing countries. Journal of International Development, 24(4), 518–527. https://doi.org/10.1002/jid.1771

- Duflo, E., & Hanna, R. (2005). Monitoring Works: Getting Teachers to Come to School. NBER Working Paper No. 11880. National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Elo, S., & Kyngäs, H. (2008). The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 62(1), 107–115. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x

- Fafchamps, M., & Minten, B. (2012). Impact of SMS-based agricultural information on Indian farmers. The World Bank Economic Review, 26(3), 383–414. https://doi.org/10.1093/wber/lhr056

- Feder, G., Anderson, J. R., Birner, R., & Deininger, K. (2010). Promises and realities of community based agricultural extension (IFPRI Discussion Paper 00959). IFPRI.

- Fujii, T. (2019). Regional prevalence of health worker absenteeism in Tanzania. Health Economics, 28(2), 311–316. https://doi.org/10.1002/hec.3844

- Gilberds, H., Handforth, C., & Leclair, M. (2016). Exploring the potential for interactive radio to improve accountability and responsiveness to small-scale farmers in Tanzania. Farm Radio International.

- Goldstein, M., Graff-Zivin, J., Habyarimana, J., Pop-Eleches, C., & Thirumurthy, H. (2013). The impact of health work absence on health outcomes: Evidence from Western Kenya. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 5(2), 58–85. https://doi.org/10.1257/app.5.2.58

- Hazell, P., Poulton, C., Wiggins, S., & Dorward, A. (2010). The Future of Small Farms: Trajectories and policy Priorities. World Development, 38(10), 1349–1361. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2009.06.012

- Henry, J. V., Winters, N., Lakati, A., Oliver, M., Geniets, A., Mbae, S. M., & Wanjiru, H. (2016). Enhancing the supervision of community health workers with WhatsApp mobile messaging: Qualitative findings from 2 low-resource settings in Kenya. Global Health: Science and Practice, 4(2), 311–325. https://doi.org/10.9745/GHSP-D-15-00386

- Heo, P. S., & Lee, D. H. (2019). Evolution of the linkage structure of ICT industry and its role in the economic system: The case of Korea. Information Technology for Development, 25(3), 424–454. https://doi.org/10.1080/02681102.2018.1470486

- Hevner, A. R., & Chatterjee, S. (2010). Design research in information systems: Theory and practice. Springer.

- Holsti, O. R. (1968). Content analysis. The Handbook of Social Psychology, 2, 596–692.

- Hufford, M. R., Stone, A. A., Shiffman, S., Schwartz, J. E., & Broderick, J. E. (2002). Paper vs. Electronic diaries. Applied Clinical Trials, 11(8), 38–43.

- Jain, L., Kumar, H., & Singla, R. K. (2015). Assessing mobile technology usage for knowledge dissemination among farmers in Punjab. Information Technology for Development, 21(4), 668–676. https://doi.org/10.1080/02681102.2013.874325

- Jarvis, A., Eitzinger, A., Koningstein, M., Benjamin, T., Howland, F., Andrieu, N., Twyman, J., & Corner-Dolloff, C. (2015). Less is more: The 5Q approach. Scientific Report, Cali, Colombia. International Center for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT).

- Jensen, R. (2007). The digital provide: Information (technology), market performance, and welfare in the South Indian fisheries sector. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 122(3), 879–924. https://doi.org/10.1162/qjec.122.3.879

- Lane, S. J., Heddle, N. M., Arnold, E., & Walker, I. (2006). A review of randomized controlled trials comparing the effectiveness of handheld computers with paper methods for data collection. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making, 6(1), 23. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6947-6-23

- Lantzos, T., Koykoyris, G., & Salampasis, M. (2013). Farm manager: An android application for the management of small farms. Procedia Technology, 8, 587–592. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.protcy.2013.11.084

- Lio, M., & Liu, M. C. (2006). ICT and agricultural productivity: Evidence from cross-country data. Agricultural Economics, 34(3), 221–228. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1574-0864.2006.00120.x

- MAAIF. (2015). Policy guide for the national agricultural extension services. Ministry of Agriculture, Animal Industry and Fisheries.

- MAAIF. (2017). A report on the profiling of farmer groups and higher-level farmer organisations in Uganda. Ministry of Agriculture, Animal Industry and Fisheries.

- March, S. T., & Smith, G. F. (1995). Design and natural science research on information technology. Decision Support Systems, 15(4), 251–266. https://doi.org/10.1016/0167-9236(94)00041-2

- Modi, D., Gopalan, R., Shah, S., Venkatraman, S., Desai, G., Desai, S., & Shah, P. (2015). Development and formative evaluation of an innovative mHealth intervention for improving coverage of community-based maternal, newborn and child health services in rural areas of India. Global Health Action, 8(1), 26769. https://doi.org/10.3402/gha.v8.26769

- Nakasone, E. (2013, August 4–6). The role of price information in agricultural markets: Experimental evidence from rural Peru [Paper presentation]. 2013 annual Meeting of the agricultural and applied Economics Association (AAEA), Washington, DC.

- Nakasone, E., & Torero, M. (2016). A text message away: ICTs as a tool to improve food security. Agricultural Economics, 47(S1), 49–59. https://doi.org/10.1111/agec.12314

- Nakasone, E., Torero, M., & Minten, B. (2014). The power of information: The ICT revolution in agricultural development. Annual Review of Resource Economics, 6(1), 533–550. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-resource-100913-012714

- Omisore, B. O. (2014). Supervision-Essential to productivity. Global Journal of Commerce & Management Perpective, 3(2), 104–108.

- Paul, S. (1992). Accountability in public services: Exit, voice and control. World Development, 20(7), 1047–1060. https://doi.org/10.1016/0305-750X(92)90130-N

- Ponelis, S. R., & Holmner, M. A. (2015). ICT in Africa: Building a better life for all. Information Technology for Development, 21(2), 163–177. https://doi.org/10.1080/02681102.2015.1010307

- Quinn, J. A., Leyton-Brown, K., & Mwebaze, E. (2011, August 7–11). Modeling and Monitoring Crop Disease in Developing Countries. Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 25(1). https://ojs.aaai.org/index.php/AAAI/article/view/7811

- Quinn, P., Goka, J., & Richardson, H. (2003). Assessment of an electronic daily diary in patients with overactive bladder. BJU International, 91(7), 647–652. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1464-410X.2003.04168.x

- Ramadhan, P. A. (2013). Teacher and health worker absence in Indonesia. Asian Education and Development Studies, 2(2), 149–161. https://doi.org/10.1108/20463161311321420

- Reda, A., Panjwani, S., & Cutrell, E. (2011). Hyke: A low-cost remote attendance tracking system for developing regions. Proceedings of the 5th ACM workshop on Networked systems for developing regions, pp. 15–20. https://doi.org/10.1145/1999927.1999933.

- Roztocki, N., Soja, P., & Weistroffer, H. R. (2019). The role of information and communication technologies in socioeconomic development: Towards a multi-dimensional framework. Information Technology for Development, 25(2), 171–183. https://doi.org/10.1080/02681102.2019.1596654

- Saidu, A., Clarkson, A. M., Adamu, S. H., Mohammed, M., & Jibo, I. (2017). Application of ICT in agriculture: Opportunities and challenges in developing countries. International Journal of Computer Science and Mathematical Theory, 3(1), 8–18. https://iiardpub.org/get/IJCSMT/VOL.%203%20NO.%201%202017/Application%20of%20ICT.pdf

- Simon, H. A. (1996). The sciences of the artificial (3rd ed.). MIT Press.

- Svensson, J., & Yanagizawa, D. (2009). Getting prices right: The impact of the market information service in Uganda. Journal of the European Economic Association, 7(2-3), 435–445. https://doi.org/10.1162/JEEA.2009.7.2-3.435