ABSTRACT

The special issue on Sharing Economy Enabled Digital Platforms for Development focuses on an investigation of an emerging form of collaborative consumption, known as sharing economy. This special issue aims to address several issues regarding important and novel research questions, analytical approaches, and to understand how the sharing economy brings about economic, social, and environmental development. After articulating the motivations that led us to launch this special issue call, we first outline the sharing economy ecosystem and its impact on sustainable development. Secondly, we propose a framework on the sharing economy development to connect all aspects of sharing economy ecosystem. Finally, we summarize the eight papers in this collection. These eight papers mainly focus on the sharing economy issues in developing regions. The accepted papers investigate the factors influencing SEDPs for development, factors influencing individuals’ intention to engage in the sharing economy, and the related trust, privacy, and regulatory issues.

1. Introduction

Emerging over the past decade, the sharing economy has experienced exponential growth (Acquier et al., Citation2017). The sharing economy is defined as a peer-to-peer activity through which access to goods and services can be given, obtained, and shared by coordinating the acquisition and distribution of a resource (Belk, Citation2014; Hamari et al., Citation2016; Li et al., Citation2021). In this emerging business model, access to goods, services, knowledge, spaces, and other assets can be shared instead of owned. In recent years, many firms have been attracted to join the sharing economy to reap economic benefits, and some of them are becoming increasingly prominent in their respective fields. With the significant success of sharing economy, an increasing number of people participate in this emerging business. As a result, the mode of people’s consumption is transforming from owning to sharing (Li et al., Citation2021).

“Sharing” is not certainly new, but this phenomenon is attracting considerable attention because the sharing is done through digital platforms. By creating two-sided market, digital platforms connect consumers who seek resource with resource owners who can offer resources (Guo et al., Citation2019). Therefore, these platforms provide spaces for product or service sharing. In recent years, many sharing economy digital platforms (SEDPs), exemplified by Airbnb (accommodation sharing), HelloBike (bike sharing), Uber and DiDi (ride sharing) have seen their businesses increased significantly (Trenz et al., Citation2018).

The sharing economy is being praised for its contribution to promoting sustainable development (Palgan et al., Citation2017), which refers to a development model that meets the current needs of people while not compromising on the resource needs of future generations (Brundtland, Citation1987). The sharing economy idea of sharing rather than owning resources is in perfect harmony with sustainable development. For instance, the sharing economy is beneficial to economic benefits, as it plays an important role in cost savings for consumers, increased earnings for suppliers and profits for operators of SEDPs (Fremstad, Citation2016). Moreover, the sharing economy potentially has a lot to offer to social development, such as the increase in social cohesion (Belk, Citation2010), and the decline in drunk driving fatalities (Greenwood & Wattal, Citation2017). Besides, the sharing economy can help alleviate environmental problems. Since the sharing economy advocates the reuse of idle resources instead of the constant production of new ones (Möhlmann, Citation2015), it increases resource efficiency and reduces resource loss (Laukkanen & Tura, Citation2020).

The sharing economy has great prospects for development. Many firms have adopted this promising business model to respond to the challenges posed by newcomers, such as Ola, Lyft, Juno, etc. However, with the growth in the numbers and size of sharing economy firms, a variety of unexpected problems occur. These have raised doubts about the extent to which the sharing economy contributes to sustainability. For instance, it was found that the car-sharing business may drive people to use shared cars frequently, consequently leading to an increase in carbon emissions (Murillo et al., Citation2017; Schor, Citation2014). At the same time, there are other more severe problems that hinder the development of the sharing economy. Individuals are hesitant to participate in sharing practices because of a lack of trust and high possible risks (Cheng et al., Citation2020; Nadeem & Al-Imamy, Citation2020). In addition, the sharing economy may result in unfair competition, create an unregulated marketplace, facilitate tax avoidance, and erode workers’ rights (Fieseler et al., Citation2017; Martin, Citation2016). Some scholars even warn that the sharing economy may be “exploiting people rather than empowering them” (Dreyer et al., Citation2017). For instance, most companies do not provide employees (i.e., resource suppliers) with health insurance, pensions, or others benefits owned by regular employment (Dreyer et al., Citation2017).

The sharing economy yields promises, problems and challenges, and has become the subject of scientific research. In this realm, there are many interesting and unsolved problems that need to be further explored by the academic community. Given the limited research on the sharing economy, this special issue aims to call for papers on recent advances in various aspects of the sharing economy with specific attention to the behavioral, managerial, technical, and policy issues that explain the success, failure, and impact on existing industries and on development. The accepted papers focus on the factors influencing SEDPs for development, factors influencing individuals’ intention to engage in the sharing economy, and the related trust, privacy, and regulatory issues.

2. Sharing economy ecosystem

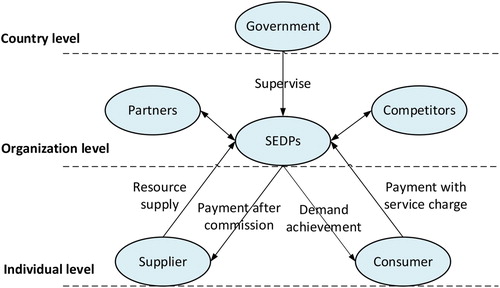

The sharing economy can be viewed as an ecosystem in which organisms coexist and interact with each other in a dynamic environment (Leung et al., Citation2019). The sharing economy ecosystem covers three different levels of consideration and relationships between major parties, as shown in . The interactions among the different parties are varied and complex, as illustrated below:

SEDPs are the core of the sharing ecosystem at the organization level. Most successful sharing firms operate through digital platforms. Sutherland and Jarrahi (Citation2018) summarize the crucial roles played by these digital platforms, including generating flexibility, match-making between supplier and consumer of goods and services, extending reach, managing transactions, developing trust, and facilitating collectivity. Thanks to the rapid growth of SEDPs, the sharing economy has extended beyond car (e.g. Uber and DiDi) and accommodation (e.g. Airbnb) to education (e.g. Thinkdoor), knowledge (e.g. XBJ.com), and healthcare sharing (e.g. AliHealth and WeDoctor) (Plewnia & Guenther, Citation2018). At the organization level, ecosystem organisms also include partners and competitors. The sharing economy brings challenges and opportunities to partners and competitors. In response, they either join in the new business model or stick to the existing business model (Leung et al., Citation2019).

Sharing practices can be dichotomized into sharing in and sharing out (Belk, Citation2014). Resource owners are often the suppliers who participate in the sharing practice by sharing out. Consumers are those consumers who are devoted to seeking the resource they need. SEDPs establish connections between suppliers and consumers in order to help achieve their respective goals (Guo et al., Citation2019). The suppliers who possess idle resources can transfer the right to use goods or services to those in need through SEDPs. The consumers can obtain shared items from suppliers in exchange for payment. By sharing idle resources (e.g. clothes, bike, and empty seats in the car), the owners gain additional value from underutilized resources while the consumers obtain goods or services at a low price, improving the sustainable and effective use of goods (Guo et al., Citation2019; Martin, Citation2016).

However, the sharing economy itself is subject to the critique. For example, the sharing economy firms are frequently accused of avoiding market and regulatory measures, which is good for them to gain what is often described as an unfair advantage over traditional industries (Fieseler et al., Citation2017; Martin, Citation2016). To assure favorable operation, the government has to supervise sharing economy business for avoiding market and regulatory failures (Leung et al., Citation2019). The sharing economy has achieved sound results in many sectors (Zervas et al., Citation2017). It has impacts at different levels. We will discuss the impact of sharing economy at individual level, organization level and country level in the next section.

3. Sharing economy and sustainable development

At the individual level, the sharing economy is assumed to promote sustainable consumption, interpersonal interaction, flexible employment, equal access to goods and services, and economic incomes. Driven by the sharing economy, people’s consumption model is moving away from the purchase toward temporary access (Li et al., Citation2021). In this sustainable consumption model, the right to use idle resources can be transferred from the owner to other consumers (Hamari et al., Citation2016). Both owners and consumers obtain values; owners can earn extra money by sharing idle resources, whereas consumers can save money by obtaining resources at a low price. By a more democratic approach to economic activities, the sharing economy plays an important role in connecting individuals and communities, encouraging cooperation, and empowering citizens (Martin, Citation2016).

At the organization level, the sharing economy fosters more new business opportunities, promotes competitiveness and profitability and reduces operating costs. The sharing economy is promoted as a prospective business model driven by digital technologies; it provides extensive commercial opportunities for entrepreneurs, firms, and industries (Martin, Citation2016). This is reflected in the fact that the sharing economy helps firms open new markets and generate new sources of revenue (Engert et al., Citation2016). Organizations based on a sharing business model are showing great prospects.

At the country level, the sharing economy is portrayed as a sustainable way to promote social, economic, and environmental development. By addressing the three pillars of sustainability (i.e., social, economy and environment), the sharing economy enhances social connection and cohesion, encourages economic growth and reduces the environmental load (Laukkanen & Tura, Citation2020). The effects of the sharing economy can be understood through environmental, social and economic perspectives at the country level (Evans et al., Citation2017). From an ecological-perspective, sustainable value is achieved by increasing resource efficiency (Kriston et al., Citation2010; Muñoz & Cohen, Citation2017), reducing carbon emissions (Kriston et al., Citation2010), responsible use of resources (Acquier et al., Citation2017), and increasing environmental friendly actions (Laukkanen & Tura, Citation2020). From a social perspective, sustainable value is reflected in sustainable consumption habits of the public (Leismann et al., Citation2013), high social welfare (Jiang & Tian, Citation2016), strengthened social cohesion (Botsman & Rogers, Citation2011), and increased social well-being (Lankoski & Smith, Citation2018). From an economic perspective, sustainable development is related to increased cost-efficiency (Bowman & Ambrosini, Citation2000), overall profits (Kumar et al., Citation2018), operational stability, and economic well-being (e.g. employment) (Laukkanen & Tura, Citation2020).

To achieve sustainable development, individuals and organizations must participate in sharing economy business activities. Individuals either act as suppliers to participate in the activities of sharing out, or act as consumers to participate in the activities of sharing in. For an organization, it aims to match the needs of different users by digital technology. Currently, the sharing economy is repeatedly accused of tax avoidance, creating unfair competition, exploiting regulatory loopholes, and creating a race to the bottom that shifts risks to consumers (Martin, Citation2016). Thus, the role at the country level is to implement government supervision to ensure the legitimacy of sharing business activities of individuals and organizations.

Prominent sharing economy businesses include car sharing (e.g. Didi and Uber), bike sharing (e.g. Mobike), accommodation sharing (e.g. Airbnb), knowledge (or skill) sharing (e.g. ZBJ.com), and meal sharing (e.g. Panda Selected). During the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, some new sharing service sectors occurred and developed rapidly, such as education sharing and healthcare sharing. This has been further reinforced during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Digital technology is a driving force of the sharing economy. The large-scale sharing or collaborative networks are based on a coordinating digital platform in which idle resource is redistributed effectively by matching supply and demand. Sorting and matching functions have thus become one of the advantages of SEDPs (Sutherland & Jarrahi, Citation2018) since automated matching helps reduce transaction costs. For example, by analyzing several certain attributes (e.g. users’ location, destination, and schedule), Uber platform enables drivers and passengers with a compatible destination to arrange their travel (Cheng et al., Citation2020). Sutherland and Jarrahi (Citation2018) have emphasized, during the system design of SEDPs, the first consideration is the extent to which digital platforms automate the match-making process.

In addition to digital platform technology, government policies, government oversight and existing infrastructures also affect the successful execution of the sharing economy. By developing a series of regulations and policies, the government may restrict, encourage or steer sharing economy business (Leung et al., Citation2019). Governments have different attitudes towards the sharing economy across different cultural contexts (Cheng, Citation2016). For instance, the regulatory authorities in Frankfurt and Massachusetts have taken action against Uber’s expansion. Contrarily, policymakers in China have taken action to promote the prosperity and growth of the sharing economy. Besides, the growth of sharing economy is also dependent on the infrastructures, such as bike parking (for bike sharing), car parking, and electric vehicle charging (for car sharing).

As mentioned above, to achieve sustainable development, users have to be motivated to engage in the sharing practices. Sharing economy platforms encourage participants to trade with strangers (Richardson, Citation2015), which increases the potential risks of transactions. With the expansion of sharing economy business, institutional defects have been exposed gradually, such as personal safety, property loss, privacy disclose, and interest disputes (Lu et al., Citation2016; Yi et al., Citation2020), which reduces individuals’ intention to participate in the sharing economy and consequently brings about insufficient sharing resources. In this context, building trust among participants is especially important to the success of the sharing economy (Cheng et al., Citation2019), as it helps create a closer bond between unfamiliar individuals. In practice, many firms have developed reputation mechanisms to build trust among traders, such as online review systems. Trust development has become one of the strategic objectives in sharing economy business.

Tarafdar et al. (Citation2013) warn that the use of information technology may bring about negative consequences. The sharing economy is no exception. The dark side behind it has also been exposed, such as whether resource suppliers should be considered employees. In addition, although gig platforms (knowledge sharing or skill sharing) emphasize work flexibility and independence, they have been criticized for short-term work without basic rights and job security (Fieseler et al., Citation2017; Plewnia & Guenther, Citation2018; Schor, Citation2014). Furthermore, some scholars also warn that accommodation sharing may result in income inequality since homeowners who can provide attractive idle rooms generally have a relatively high income (Palgan et al., Citation2017).

4. Framework on sharing economy sustainable development

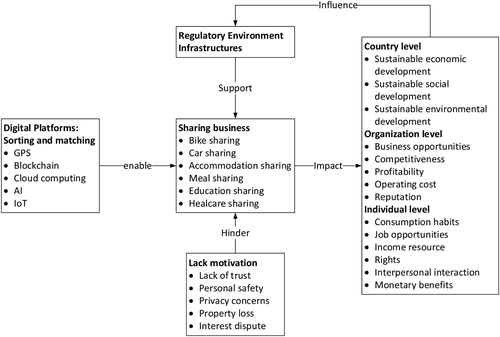

By integrating advanced digital technologies including GPS, blockchain, cloud computing, AI (Artificial Intelligence) and IoT (Internet of things), sharing economy digital platforms have accomplished the redistribution of underutilized resources. The sharing economy has an influence on individuals, organizations, and even countries. For individuals, key consequences include sustainable consumption habits, increased job opportunities and income resources, democratic rights, intimate interpersonal relationships and improved economic benefits (Cheng et al., Citation2019; Cheng et al., Citation2020; Li et al., Citation2021; Martin, Citation2016). For organizations, key consequences include increased business opportunities, improved competitiveness, high profitability, reduced operating cost, and high reputation (Engert et al., Citation2016; Martin, Citation2016). For countries, key consequences are reflected in three aspects, including economic sustainability, social sustainability, and environmental sustainability (Laukkanen & Tura, Citation2020). illustrates the contextual framework:

Although digital platforms provide fundamental technical infrastructure, the success of the sharing economy also depends on the regulatory environment and existing infrastructures. Government policies and infrastructure improvement are influenced by individual, organizational, and country performance (Roztocki & Weistroffer, Citation2016). The development of sharing economy business, in turn, affects the performances of individuals, organizations, and countries. Owing to the potential risks, including privacy disclosure, personal safety, and property loss, the enthusiasm of individuals to participate in the sharing economy may decrease. In response, trust is a precondition for individuals to participate in the sharing practices. Therefore, the development of trust between suppliers, platforms, and consumers is critical to the success of the sharing economy.

5. Papers in this special issue

This special issue brings together eight papers on the sharing economy. The papers in this special issue all deal with some aspects of the framework shown in . They generally consider bike sharing, riding sharing and accommodation sharing. The first six papers are concentrated on consumers’ perception, behavioral intention in the sharing economy. The last two papers address the issues about the sharing economy at the country level. Specifically, the seventh paper examines how SEDPs contribute to social and economic development. The last paper investigates the impact of government supervision on bike-sharing business.

The first paper is co-authored by Jinyuan Guo, Jiabao Lin, and Lei Li and is entitled “Building users’ intention to participate in a sharing economy with institutional and calculative mechanisms: an empirical investigation of DiDi in China”. The authors emphasize the important role of trust in the reduction of uncertainty and risk under the sharing economy. Focusing on drivers in DiDi platforms, this paper investigates the antecedents of drivers’ trust and the role of trust in their intention to participate in the sharing economy. Two trust dimensions are proposed in this study, namely calculative-based trust, and institution-based trust, and then examines the antecedents and outcomes of trust in the ride-sharing context. This study contributes to the development of ride-sharing platforms from the perspective of drivers.

The second paper is co-authored by Upadhyay Chandra Kant, Tewari Vijayshri, and Tiwari Vineet and is entitled “Assessing the impact of sharing economy through the adoption of ICT based crowdshipping platform for last-mile delivery.” This study develops and validates a sociotechnical framework to investigate the Indian urban and semi-urban participant’s intention to participate in sharing economy for last-mile delivery by considering the mediating roles of trust and attitude. This study provides practical implications for service providers to attract users to engage in crowdshipping platforms for last-mile delivery.

The third paper is co-authored by Jifan Ren, Jialiang Yang, Mengyang Zhu, and Salman Majeed, and is entitled “Relationship between consumer participation behaviors and consumer stickiness on mobile short video social platform under the development of ICT: Based on value co-creation theory perspective.” Employing the value co-creation theory as a theoretical basis, this paper investigates how consumer participation behaviors under different emotions influence consumer stickiness by consumer perceived value. After analyzing 902 questionnaires collected from TikTok consumers, the authors conclude that both positive and negative consumer participation behaviors influence consumer perceived value, and then impact consumer happiness and stickiness. This study provides helpful implications for social media companies to increase their users’ stickiness.

The fourth paper is co-authored by Syed Hamad Hassan Shah, Saleha Noor, Shen Lei, Atif Saleem Butt, and Muhammad Ali and is entitled “Role of privacy/safety risk and trust on the development of prosumption and value co-creation under the sharing economy: a moderated mediation model.” The authors point out that perceived privacy-safety risk, prosumption, and prosumers’ trust affect prosumers’ intention to join in value co-creation under the sharing economy. Based on the Orlikowski’s duality of technology framework and the mediating role of prosumption and the moderating role of prosumers’ trust, this study examines how privacy-safety risk influences value co-creation in the sharing economy context. After analyzing questionnaire survey data from DiDi users in China and Uber users in Pakistan, this study illustrates that both trust development and less privacy-safety risk contribute to value co-creation under the sharing economy.

The fifth paper is co-authored by Lin Li, Kyung Young Lee, Younghoon Chang, Sung-Byung Yang, and Philip Park and is entitled “IT-enabled sustainable development in electric scooter sharing platforms: focusing on the privacy concerns for traceable information.” This paper pays attention to the privacy concerns for traceable information (PCTI) in the context of electric scooter sharing services. The authors propose a new concept of PCTI, including privacy concerns for payment information and privacy concerns for location information, and empirically investigate the relationship between PCTI and information privacy-protective responses (IPPR) to identify the factors that influence the level of PCTI. By introducing a new measurement of PCTI, this study advances our knowledge on the privacy concerns in the sharing economy business.

The sixth paper is co-authored by Shuai Wang, Shuang (Sara) Ma, and Yonggui Wang and is entitled “The role of platform governance in customer risk perception in the context of peer-to-peer platforms.” The authors note that although the peer-to-peer (P2P) economy has increased social and economic benefits, a high level of potential risk is discouraging individuals from continuously engaging in the P2P economy. Based on government theory, this paper examines how platform governance influences individuals’ risk perception and the moderating role of property price and professional peer providers in the relationship between platform governance and customer risk perception. This paper provides practical contributions to platform governance in terms of risk control in virtual communities.

The seventh paper is co-authored by Li Cui, Ying Hou, Yang Liu, and Lu Zhang and is entitled “Text mining to explore the influencing factors of sharing economy driven digital platforms to promote social and economic development.” This paper sets out to identify key antecedents for sharing economy-driven digital platforms to promote social and economic development. This investigation has offered prospective insights for companies running these digital sharing economy platforms in China. The authors adopt a text mining approach to perform a comprehensive analysis of different platforms (i.e. Tujia, Xiaozhu, and Airbnb) with different models (B2C and C2C). The results indicate that C2C-based sharing economy digital platforms focus more on social benefits, while B2C-based platforms emphasize economic benefits. They also find two new driving forces of promoting economic and social benefits, that is, technological and regulatory innovation. This study provides valuable suggestions for the sharing economy driven digital platforms to promote socioeconomic development.

The eighth paper is co-authored by Linfeng Li, Guo Li, and Sheng Liang and is entitled “Does government supervision suppress free-floating bike sharing (FFBS) development? Evidence from Mobike in China.” The authors argue that government supervision is particularly important for the development of FFBS. Based on the difference-in-differences (DID) model and massive travel data on the Mobike platform in Chengdu, this paper examines how government supervision influences FFBS development. The authors find that supervision enables FFBS to increase attention to the reduction of consumption of public resources and the relief of the pressure of public transport. Notably, government supervision is not effective for all FFBS travel behaviors and times.

6. Conclusion

These papers investigate the issues associated with the sharing economy at the individual level and country level. Most of the research is being conducted in developing regions, we thus know much about how, in what form, and with what implications and challenges the sharing economy is emerging in developing countries. However, although low entry barriers have provided extensive opportunities for many start-ups to adopt sharing economy business models, we know very little about the sharing economy at the organization level.

We can draw conclusions from the special issue. SEDPs operate in multiple sectors, with different impacts on social and economic development. Out of privacy concerns, consumers are reluctant to participate in the sharing economy. Trust establishment is vital to the future development of the sharing economy. To a certain extent, government supervision can promote the sustainable development of the sharing economy. The papers in our special issues enhance our understanding of the interaction mechanism between the various organisms in the sharing economy ecosystem and enrich the domain knowledge. However, the sharing economy is in a precarious environment during the COVID-19 pandemic that has caused more risk and other problems. The COVID-19 pandemic has also raised concerns about the survivability of the sharing economy. Therefore, during the COVID-19 pandemic, several new issues related to the sharing economy need to be further discussed and addressed.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Sajda Qureshi, Manoj Thomas, Yan Li and Monideepa Tarafdar for their extremely valuable feedback on earlier versions of this work.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Xusen Cheng

Xusen Cheng is a Professor of Information Systems in the School of Information at Renmin University of China, Beijing, China. He has obtained his PhD in informatics atManchester Business School at the University of Manchester. His research focuses on trust development in virtual teams, collaboration process, and system design, sharing economy and e-commerce, and the integration of behavior and design issues in information system. His research paper has been accepted/appeared in journals such as MIS Quarterly, Journal of Management Information Systems, European Journal of Information Systems, Tourism Management, Decision Sciences, Information and Management, Information Processing and Management, International Journal of Information Management, Information Technology and People, Computers in Human Behavior, Information Technology for Development, amongst others. His research has also been included in numerous conference proceedings such as ICIS, HICSS, AMCIS, PACIS, amongst many others.

Jian Mou

Jian Mou is an associate professor of Management Information Systems in the School of Business, Pusan National University, South Korea. He received his PhD degree in Information Systems from University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa. Dr Mou was previously an adjunct professor at the Business School of Sungkyunkwan University, South Korea. In addition, Dr Mou engaged in research as a visiting scholar at the University of Illinois-Chicago, USA. His research interests include electronic commerce, human computer interaction, trust and risk issues in electronic services, and the dynamic nature of systems use. His work has been accepted/appeared in journals such as Journal of the Association for Information Systems, Computers in Human Behavior, Industrial Management & Data Systems, International Journal of Information Management, Electronic Commerce Research, International Journal of Innovation Studies, Information Processing & Management, Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, IT and People, Behaviour and Information Technology, International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction, Information Development, and proceedings of ICIS (2013, 2014, 2017, 2018), ECIS, PACIS, and ACIS.

Xiangbin Yan

Xiangbin Yan is a Professor and head of the School of Economics and Management in the University of Science & Technology Beijing, China. He was previously the Chair of the Department of Management Science & Engineering in the School of Management at Harbin Institute of Technology (HIT), China. He received a PhD from the Department of Management Science & Engineering from Harbin Institute of Technology. He has been a visiting research scholar in the AI Lab in the MIS Department at the University of Arizona from 2008 to 2009. His current research interests include electronic commerce, social media analytics, social network analysis, and business intelligence. His work has appeared in journals such as Information Systems Research, Journal of Management Information Systems, Production and Operations Management, Information and Management, Journal of Informetrics, Information Systems Frontiers, amongst others.

References

- Acquier, A., Daudigeos, T., & Pinkse, J. (2017). Promises and paradoxes of the sharing economy: An organizing framework. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 125, 1–10. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2017.07.006

- Belk, R. (2010). Sharing: Table 1. Journal of Consumer Research, 36(5), 715–734. doi:https://doi.org/10.1086/612649

- Belk, R. (2014). You are what you can access: Sharing and collaborative consumption online. Journal of Business Research, 67(8), 1595–1600. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2013.10.001

- Botsman, R., & Rogers, R. (2011). What's mine is yours, the rise of collaborative consumption. HarperCollins.

- Bowman, C., & Ambrosini, V. (2000). Value creation versus value capture: Towards a coherent definition of value in strategy. British Journal of Management, 11(1), 1–15. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8551.00147

- Brundtland, G. H. (1987). Our common future: The world commission on environment and development. Oxford University Press.

- Cheng, M. (2016). Sharing economy: A review and agenda for future research. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 57, 60–70. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2016.06.003

- Cheng, X., Fu, S., Sun, J., Bilgihan, A., & Okumus, F. (2019). An investigation on online reviews in sharing economy driven hospitality platforms: A viewpoint of trust. Tourism Management, 71, 366–377. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2018.10.020

- Cheng, X., Su, L., & Yang, B. (2020). An investigation into sharing economy enabled ridesharing drivers’ trust: A qualitative study. Electronic Commerce Research and Applications, 40, 100956. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.elerap.2020.100956

- Dreyer, B., Lüdeke-Freund, F., Hamann, R., & Faccer, K. (2017). Upsides and downsides of the sharing economy: Collaborative consumption business models’ stakeholder value impacts and their relationship to context. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 125, 87–104. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2017.03.036

- Engert, S., Rauter, R., & Baumgartner, R. J. (2016). Exploring the integration of corporate sustainability into strategic management: A literature review. Journal of Cleaner Production, 112, 2833–2850. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.08.031

- Evans, S., Vladimirova, D., Holgado, M., Van Fossen, K., Yang, M., Silva, E. A., & Barlow, C. Y. (2017). Business model innovation for sustainability: Towards a unified perspective for creation of sustainable business models. Business Strategy and the Environment, 26(5), 597–608. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.1939

- Fieseler, C., Bucher, E., & Hoffmann, C. P. (2017). Unfairness by design? The perceived fairness of digital labor on crowdworking platforms. Journal of Business Ethics, 156(2), 1–19. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-017-3607-2

- Fremstad, A. (2016). Sticky norms, endogenous preferences, and shareable goods. Review of Social Economy, 74(2), 194–214. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00346764.2015.1089107

- Greenwood, B. N., & Wattal, S. (2017). Show me the way to go home: An empirical investigation of ride-sharing and alcohol related motor vehicle fatalities. MIS Quarterly, 41(1), 163–187. doi:https://doi.org/10.25300/MISQ/2017/41.1.08

- Guo, Y., Li, X., & Zeng, X. (2019). Platform competition in the sharing economy: Understanding how ride-hailing services influence new car purchases. Journal of Management Information Systems, 36(4), 1043–1070. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/07421222.2019.1661087

- Hamari, J., Sjöklint, M., & Ukkonen, A. (2016). The sharing economy: Why people participate in collaborative consumption. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 67(9), 2047–2059. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.23552

- Jiang, B., & Tian, L. (2016). Collaborative consumption: Strategic and economic implications of product sharing. Management Science, 63(4), 1171–118. doi:https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2016.2647

- Kriston, A., Szabó, T., & Inzelt, G. (2010). The marriage of car sharing and hydrogen economy: A possible solution to the main problems of urban living. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, 35(23), 12697–12708. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2010.08.110

- Kumar, V., Lahiri, A., & Dogan, O. B. (2018). A strategic framework for a profitable business model in the sharing economy. Industrial Marketing Management, 69, 147–160. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2017.08.021

- Lankoski, L., & Smith, N. C. (2018). Alternative objective functions for firms. Organization and Environment, 31(3), 242–262. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1086026617722883

- Laukkanen, M., & Tura, N. (2020). The potential of sharing economy business models for sustainable value creation. Journal of Cleaner Production, 253, 120004. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.120004

- Leismann, K., Schmitt, M., Rohn, H., & Baedeker, C. (2013). Collaborative consumption: Towards a resource-saving consumption culture. Resources, 2(3), 184–203. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/resources2030184

- Leung, X. Y., Xue, L., & Wen, H. (2019). Framing the sharing economy: Toward a sustainable ecosystem. Tourism Management, 71, 44–53. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2018.09.021

- Li, L., Lee, K. Y., Chang, Y., Yang, S. B., & Park, P. (2021). IT-enabled sustainable development in electric scooter sharing platforms: Focusing on the privacy concerns for traceable information. Information Technology for Development, 1–24. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02681102.2021.1882366

- Lu, B., Zeng, Q., & Fan, W. (2016). Examining macro-sources of institution-based trust in social commerce marketplaces: An empirical study. Electronic Commerce Research and Applications, 20, 116–131. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.elerap.2016.10.004

- Martin, C. J. (2016). The sharing economy: A pathway to sustainability or a nightmarish form of neoliberal capitalism? Ecological Economics, 121, 149–159. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2015.11.027

- Möhlmann, M. (2015). Collaborative consumption: Determinants of satisfaction and the likelihood of using a sharing economy option again. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 14(3), 193–207. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/cb.1512

- Muñoz, P., & Cohen, B. (2017). Mapping out the sharing economy: A configurational approach to sharing business modeling. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 125, 21–37. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2017.03.035

- Murillo, D., Buckland, H., & Val, E. (2017). When the sharing economy becomes neoliberalism on steroids: Unravelling the controversies. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 125, 66–76. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2017.05.024

- Nadeem, W., & Al-Imamy, S. (2020). Do ethics drive value co-creation on digital sharing economy platforms? Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 55, 1–13. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2020.102095

- Palgan, V. Y., Zvolska, L., & Mont, O. (2017). Sustainability framings of accommodation sharing. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 23, 70–83. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2016.12.002

- Plewnia, F., & Guenther, E. (2018). Mapping the sharing economy for sustainability research. Management Decision, 56(3), 570–583. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/MD-11-2016-0766

- Richardson, L. (2015). Performing the sharing economy. Geoforum, 67, 121–129. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2015.11.004

- Roztocki, N., & Weistroffer, H. R. (2016). Conceptualizing and researching the adoption of ICT and the impact on socioeconomic development. Information Technology for Development, 22(4), 541–549. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02681102.2016.1196097

- Schor, J. (2014). Debating the sharing economy. Great Transition Initiative, 1–14.

- Sutherland, W., & Jarrahi, M. H. (2018). The sharing economy and digital platforms: A review and research agenda. International Journal of Information Management, 43, 328–341. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2018.07.004

- Tarafdar, M., Gupta, A., & Turel, O. (2013). The dark side of information technology use. Information Systems Journal, 23(3), 269–275. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/isj.12015

- Trenz, M., Frey, A., & Veit, D. (2018). Disentangling the facets of sharing: A categorization of what we know and don’t know about the sharing economy. Internet Research, 28(4), 888–925. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/IntR-11-2017-0441

- Yi, J., Yuan, G., & Yoo, C. (2020). The effect of the perceived risk on the adoption of the sharing economy in the tourism industry: The case of Airbnb. Information Processing & Management, 57(1), 1–11. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ipm.2019.102108

- Zervas, G., Proserpio, D., & Byers, J. W. (2017). The rise of the sharing economy: Estimating the impact of Airbnb on the hotel industry. Journal of Marketing Research, 54(5), 687–705. doi:https://doi.org/10.1509/jmr.15.0204