ABSTRACT

Internally Displaced People (IDP) have received less attention in ICT4D research. This study examines how IDP in Africa use mobile phones to enhance their social inclusion. We employed Sen’s Capability Approach as the theoretical lens and a qualitative case study as a methodology. Qualitative data obtained from 21 conflict-induced IDP in Nigeria suggests that mobile phones serve not only as a self-help commodity to overcome disconnection from their communities but also a means to enhance their individual and collective capabilities, which in turn fosters their social inclusion. However, generating these capabilities depend on the personal, social, and environmental experiences of IDP. With these findings, the study offers contributions to theory, research, and practice.

1. Introduction

According to the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC), there are an estimated 41 million Internally Displaced People (IDP) globally that have been forcibly displaced from their homes due to conflicts or natural disasters (IDMC, Citation2019). Unlike refugees, IDP remains within national borders under their state’s sovereignty (Cohen, Citation2006). Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) hosts approximately 17.8 million IDP, over one-third of the global internally displaced population (IDMC, Citation2019). In many cases, IDP who flee from natural disasters usually get support from their governments and can rebuild their lives after some time (Sabie et al., Citation2019). However, conflict-induced IDP tend to be more vulnerable due to lack of access to basic amenities and marginalization by their governments (World Bank, Citation2016). Ongoing conflicts and violence in countries such as the Central African Republic, Democratic Republic of Congo, Nigeria, Sudan and Somalia are a significant contribution to the growing number of IDP in Africa (IDMC, Citation2019).

Conflict-induced IDP have been widely discussed in economics, political and development literature (Akresh et al., Citation2012; Alix-Garcia et al., Citation2013; Saparamadu & Lall, Citation2014). These studies indicate that IDP are subject to various forms of social exclusion, such as limited participation in social, economic, cultural and political activities. Recently, the increasing use of mobile phones by displaced people to enhance their social inclusion has attracted research interest in the Information and Communication Technology for Development (ICT4D) community (see Mancini et al., Citation2019). Social inclusion is defined as

the process of improving the terms of participation in society for people who are disadvantaged on the basis of age, sex, disability, race, ethnicity, origin, religion, or economic or other status, through enhanced opportunities, access to resources, voice and respect for rights. (UN, Citation2016, p. 20)

However, extant research on the use of mobile phones for social inclusion by displaced people have focused on refugees and migrants; therefore, less is known about IDP, especially the ones in Africa, who rely on mobile phones as they relocate for safety and a better life (Bacishoga et al., Citation2016; IDMC, Citation2019). Hence there have been calls for more studies on IDP to better understand their conditions and how mobile technologies can improve their social inclusion (Sabie et al., Citation2019). Such research is not only relevant but also timely, particularly within the context of SSA, where there is a growing number of IDP escaping the internal conflict of Africa (UNHCR, Citation2018). It is against this backdrop that we attempt to answer the research question: ‘How do IDP in Africa use mobile phones to enhance their social inclusion?’ We believe that specifically studying IDP in Africa will provide an opportunity to understand how mobile phones can support IDP and how their experience might differ from refugees living in the global north.

To address this question, we employ Sen’s capabilities approach (Sen, Citation1999) as a theoretical lens to understand the capabilities enabled by mobile phones that can enhance the social inclusion of IDP. A qualitative case study was adopted as the methodology. This study uses evidence from IDP that has been forced to flee from the ‘Boko Haram’ insurgency in the North-Eastern region of Nigeria. The rest of this paper is structured as follows: first, we provide a theoretical discussion on the notion of social inclusion, and displacement and mobile phones; we then introduce Sen’s Capability Approach as a theoretical lens for the study. Next, we present the research methods through which data was gathered and analysed. Subsequently, we outline the findings and analysis of our study. This is followed by the discussion section, where we discuss the contributions of the study. The final section presents the conclusion and limitations of the study.

2. Literature review

2.1. Social inclusion

To better conceptualize social inclusion, it is important to understand the notion of social exclusion. Social exclusion is deeply rooted in poverty and is commonly defined in monetary terms (Silver & Miller, Citation2003). It has increasingly been understood from a multi-dimensional perspective to have an impact not only on the individual but also on the whole of society (Vinson, Citation2009). From this perspective, social exclusion is defined as ‘a complex and multi-dimensional process. It involves the lack of or denial of resources, rights, goods and services, and the inability to participate in normal relationships and activities’ (Levitas et al., Citation2007, p. 9).

Social inclusion, on the other hand, is the extent to which individuals are able to fully participate in society (Warschauer, Citation2003). Clearly, social inclusion, although related to social exclusion, cannot merely be seen as simple exclusion (Livari et al., Citation2018). Tackling social exclusion is about alleviating disadvantages, while promoting social inclusion involves proactively creating opportunities (Phipps, Citation2000). We position our study with the definition of social inclusion that is concerned with the opportunities people have to participate in an inclusive society. Van Winden (Citation2001) provides a distinction between the three major dimensions of social inclusion. The social dimension focuses on access to social services such as education, housing and opportunities for social participation. Political dimension is concerned with attaining full human rights, civic engagement and access to political participation. Last is the economic dimension, which focuses on employment, income status and access to the local economy.

Although, the dominant approach to social inclusion has continued to focus mainly on the economic dimension while ignoring other dimensions such as social and political participation (Phipps, Citation2000). Warschauer (Citation2003) argues that inclusion should not only emphasize access to economic resources but also focus on opportunities that will enable individuals and communities to participate in society and control their destinies. There are several social, economic and political dimensions involved both at the micro and macro level (Trauth & Howcroft, Citation2006; Warschauer, Citation2003). As a multi-faceted concept, social inclusion needs to be conceptualized as a dynamic and relational process (Phipps, Citation2000).

This has led to the view of social inclusion that emphasizes agency and empowerment in line with the capability approach (AbuJarour et al., Citation2018). According to this view, social inclusion is something carried out by people and not done on their behalf (Taket et al., Citation2009). Here, social inclusion is a multidimensional phenomenon not limited to people’s access to material resources but also on how they can put these resources into making life choices (Sen, Citation1999). To enhance social inclusion, there must be resources, including the ability to use these resources to facilitate people’s full participation in the society (Hardy & Leiba-O'Sullivan, Citation1998; Livari et al., Citation2018).

In recent years, ICT has been recognized to enhance social inclusion (Choudrie et al., Citation2017; Taylor & Packham, Citation2016). Research has found that the use of ICT can enable people to build their social capital, engage in social networks and strengthen their sense of belonging (Urquhart et al., Citation2008). Also, access to ICT is instrumental in enhancing the civic and political participation in policy and local decision making (Nemer & Tsikerdekis, Citation2017; Thakur, Citation2009). Other studies have highlighted the influential role of ICT in providing job opportunities to individuals and getting them back into the labour market (Marr & Yan, Citation2011; Maya-Jariego et al., Citation2009).

Although other studies have a skeptical view of the role of ICT with regard to social inclusion, and believe that ICT can further contribute to the social exclusion of individuals. Such studies argue that socially disadvantaged communities who cannot afford ICT and have difficulties accessing it are at the risk of remaining excluded from the information society and subsequently failing to participate and integrate into the society (Alam & Imran, Citation2015; Törenli, Citation2006). In addition, some studies have shown that access to ICT alone is not sufficient, they argued that lack of ICT literacy skills and language competency limits the ability of the rural poor communities to use ICT, and this adversely affects their inclusion in the information society (Hull, Citation2003; Alam, & Imran). Hence, we extend our conceptualization of the role of ICTs for social inclusion by moving beyond just access to ICT toward a broader understanding of the way ICT can be utilized to expand the economic, social and political participation of individuals, which in turn is fundamental enhancing their social inclusion.

Within the ICT4D literature, there is a gap in which displaced people use ICT and how these ICT impacts on their social inclusion within the wider society (Abujarour et al., Citation2021; Mancini et al., Citation2019). The few existing literature have been specifically focused on refugees and migrants and are yet to expand their focus on people that are internally displaced within their own countries (Sabie et al., Citation2019). To address this gap, this study explores the use of mobile phones by IDP in Nigeria to enhance their social, economic and political dimensions of social inclusion.

In the following section, we provide a review of the extant literature of displaced people and ICT use, and we focus on the few studies, that is, mostly refugee studies, that touch on the role that mobile phones play in the social inclusion of displaced people. Studies on IDP have largely been ignored in the literature.

2.2. Displaced people and mobile phones

There is a growing body of research investigating how ICT can enhance the social inclusion of displaced people. As displaced people, they have moved from their homes into new and unfamiliar communities in which they need to adapt and construct meaningful lives (Díaz Andrade and Doolin, Citation2016). Majority of these studies have focused on the use of mobile phones by refugees and migrants in the global north (Bock et al., Citation2020; Shah et al., Citation2019). These studies have shown that mobile phone penetration and use among refugees is growing and can be seen to facilitate the social integration of refugees (Abujarour et al., Citation2021; Casswell, Citation2019).

For example, mobile phones enable refugees to stay connected with families back home and establish new connections with locals in their host communities(Wall et al., Citation2017). This helps them overcome the feeling of social isolation and develop a sense of belonging in their host communities (Kaufmann, Citation2018; Wilding, Citation2012). Also, interacting with members of their host communities using mobile phones help refugees overcome language barriers and also learn about host communities’ behaviour and culture, which is useful to their social and economic integration (Bacishoga et al., Citation2016; Mancini et al., Citation2019). Access to the internet using mobile phones have provided refugees with the means to access general information about issues relating to settlement, such as support services, rights, settlement, citizenships, employment, community facilities housing and language learning programmes (AbuJarour & Krasnova, Citation2017; Maitland et al., Citation2015). Refugees use text messages and translation applications to overcome language barriers when accessing services relating to healthcare, housing and employment (Abujarour et al., Citation2021; Danielson, Citation2013). Besides helping refugees access information, Veronis et al. (Citation2018) noted that mobile phones provide a virtual space where refugees develop transcultural connections, that is, negotiating and bridging the cultural gap between refugees and the local culture.

The role of mobile phones for fostering learning and skills development that allows for a faster integration into their host communities was also considered in the literature. Refugees use e-learning platforms through mobile apps to learn the languages of their host communities during their first phase of resettlement (AbuJarour & Krasnova, Citation2018). Mobile phones used in the education context provide refugees the opportunities to experiment, socialise, learn and grow (Mancini et al., Citation2019). Dahya and Dryden-Peterson’s (Citation2017) study shows that mobile phones enabled access to social networks which allowed refugee women to engage in transnational conversation with other women studying in higher education and this, in turn, contributed to creating a new pathway for refugee education.

Mobile technologies can have an impact on not only educational but also health inclusion. Refugees connect with online platforms using their mobile phones to access health information and health care from host communities (Pottie et al., Citation2020). Also, refugees relied on social media and text messaging for health care integration, that is, to communicate with health care providers (Danielson, Citation2013). In addition, mobile phones facilitate online self-help and access to online health support groups that provide therapeutic support and collaborative relationships among refugees (Pottie et al., Citation2020; Siapera & Veikou, Citation2013).

Politically, mobile phones have provided refugees the possibility to exercise their right to express and engage in political discussions in both their host societies and their home of origin (Leurs, Citation2017). Refugees connect to social network to voice out their opinions, engage in both online and offline activism, influence politics and policy, and advocate for refugees rights (Alhayek, Citation2016; Godin & Doná, Citation2016; Pottie et al., Citation2020). According to Siapera and Veikou (Citation2013), refugee youths use their mobile phones to contribute to discussions on social media aimed to bring about their empowerment and action from short postings, storytelling and movements.

Other studies have shed light on the barriers to the use of mobile phones that limits the social inclusion of refugees into the society. Refugees access to reliable and stable mobile connectivity is usually restricted by limited financial resource, the difficulty of getting a sim-card due to their uncertain legal status and local communication infrastructure in their host communities (Fiedler, Citation2019; Maitland & Xu, Citation2015; Witteborn, Citation2015; Wall et al., Citation2017). Other barriers include language skills, limited digital literacy skills and refugees’ sense of insecurity and fear of being surveilled by the government when using their mobile phones (Mancini et al., Citation2019; Opas & McMurray, Citation2015; Wall et al., Citation2017).

However, despite the interest in the study of displaced people, research on mobile phones and displaced people has received little attention within the ICT4D domain (Bock et al., Citation2020). The few existing studies discussed above focused on the role of mobile phones on the social inclusion of refugees and migrants in the global north (Alencar, 2020; Mancini et al., Citation2019). Other displaced groups such as IDP have remained under-studied in the ICT4D literature. Hence, this study contributes to the literature with a qualitative study of the use of mobile phones by conflict-induced IDP in Nigeria who temporarily reside in resource-constrained environments. We discuss how they make use of their mobile phones to enhance their social inclusion. We also highlight the challenges that impede their ability to utilize mobile phones for social inclusion purposes.

2.3. Theoretical framework: the capability approach

Understanding how ICT contributes to social inclusion has been a complex analytical task (Díaz Andrade & Doolin, Citation2016; Kleine, Citation2009). Sen’s (Citation1999) Capability Approach (CA) has been suggested as an alternative approach to theorising the role of ICT in initiating and supporting the social inclusion of displaced people (AbuJarour & Krasnova, Citation2017; Díaz Andrade & Doolin, Citation2016). The CA is primarily focused on the notion of ‘freedom’ which broadly refers to the effective opportunities that people have to live the kind of life they have reason to value (Sen, Citation1999). Sen views freedom as both the primary end and means to development.

Sen’s CA critiques other philosophical approaches that focus on people’s economic income and expenditure (Robeyns, Citation2005). The CA has been widely used in the field of politics, welfare economics, social policy, and development studies to assess social arrangements and individual well-being (Robeyns, Citation2017). CA comprises two key elements, namely, functionings and capabilities. Functionings are beings and doings, for example, being employed, being nourished or exercising, eating and so on. Capabilities, on the other hand, refers to an individual’s freedom to achieve valuable functionings, for example, the freedom to be educated.

Sen further identifies two other critical elements of the CA, namely, well-being and agency. He argues that an individual’s capability can be assessed in terms of his/her well-being which could be defined in an elementary manner (nutritional status) or a more sophisticated fashion (self-dignity). As such, Sen speaks of well-being, freedom or well-being achievement. Also, capability can relate to the agency, which Sen refers to as an individual’s ability to pursue and actualise the goals that he/she values, for example, political freedoms. Sen (Citation1999) refers to an agent as an individual who acts and brings about change as opposed to someone who is oppressed or forced. Sen also talks about agency freedom or agency achievements.

The Capability approach has been used by several ICT4D scholars to examine the complex relationship between ICT and human development. For example, Sen himself (Citation2010) discusses the role of mobile phones in expanding individual freedoms. Sahay and Walsham (Citation2017) use a case study of a public health system in India to show how the health information systems led to increased opportunities for the patients. Msoffe and Lwoga (Citation2019) provide evidence that mobile phones enabled rural farmers in Tanzania to build their financial, human and social capabilities. Zheng and Walsham (Citation2008) applied CA to conceptualize social exclusion in the e-society as a capability deprivation using case studies in China and South Africa. Hatakka and Lagsten (Citation2012) operationalized CA using a case study of higher education students from developing countries to show the educational capabilities enabled as a result of their use of internet resources. Kleine (Citation2010) presents the choice framework as a way to operationalize CA within the ICT4D domain.

In this study, we examine conceptualized social inclusion as a form of capability enhancement. Sen (Citation2000) argues that being excluded from social relations can ‘be constitutively a part of capability deprivation as well as instrumentally a cause of diverse capability failures’ (p. 5). Sen (Citation2000) considers that functionings also involves being part of a community. According to Sen (Citation2000), individuals value not being excluded from social relations as such taking part in the life of the community is important and constitutive of one’s life. Also, being excluded from social relations can lead to other deprivations, which further hinders the lives of individuals. For example, ‘being excluded from the opportunity to be employed or to receive credit may lead to economic impoverishment that may, in turn, lead to other deprivations (such as undernourishment or homelessness)’ (5). Sen’s idea on social exclusion ‘lies in emphasizing the role of relational features in the deprivation of capability’ (6). Although Sen’s does not clearly define what social relations or social inclusion means, however, by simply reversing Sen’s conceptualization of social exclusion, then social inclusion could simply be defines as enabling opportunities for social relations that could lead to alleviating capability failure (Suzuki, Citation2017).

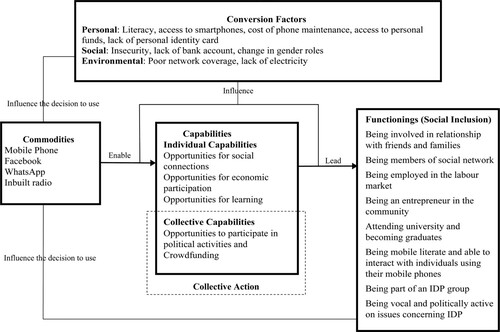

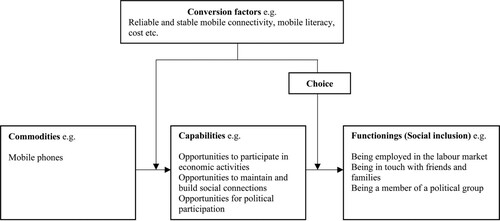

We adapt Robeyns (Citation2005) non-dynamic representation of a person’s capability set and her social, personal and environmental context due to its importance in explaining the process that leads to the contribution of ICT to social inclusion. One of the basic emphasis of Robeyns (Citation2005) is on the vital role material goods and services (commodities) play in contributing to individual well-being in both the short and long term. Examples of goods could be mobile phones, and services can be digital literacy programmes. Examples of capabilities could be opportunities to seek employment or learn a new language using mobile phones. Functionings are outcomes that can also contribute to various dimensions of social inclusion. An instance is being employed in the labour market as a result of the employment opportunities provided by mobile phones.

It is important to note that the abilities of an individual to generate capabilities are dependent on the availability of conversion factors. Three categories of conversion factors are identified, namely personal conversion factors, for example, gender, age, education; social conversion factors, for example, social norms, public policies, power relations; and environmental conversion factors, for example, infrastructure and climate (Robeyns, Citation2005). For example, for an individual to be able to utilize a mobile phone to generate capabilities for learning, he or she should have the skills to operate a mobile phone. These factors further reinforce agency and serve as a constituent of the capability set of a person.

Furthermore, commodities are not only the means of expanding peoples’ capabilities. There are also other means that function as input, such as social institutions, social and legal norms and so on. It should be noted that functionings are based on an individual’s personal choice to select from the available capability set, and this also depends on conversion factors. In short, commodities are an important means to individual well-being but not the ends of well-being (Robeyns, Citation2005). A visual representation of the concepts of the CA and their relationships is shown in .

Figure 1. Visual representation of the concepts of CA in relation to social inclusion (adapted from Robeyns, Citation2005).

However, the level of analysis with CA framework is focused on an individual level which has been termed as insufficient (Ibrahim, Citation2006). Authors argue that the capability approach needs to be complemented with theories and concepts of collective capabilities and collective action in order to cater for groups (Ibrahim, Citation2006; Pelenc et al., Citation2015). Collective capabilities are not

the sum or average of individual capabilities but rather newly generated capabilities that an individual attains as a result of their engagement in a collective action or their membership in a social network that helps them achieve the life they value. (Ibrahim, Citation2006, p. 404)

ICT can enable capabilities both at an individual and collective level. For example, mobile phones can provide individuals with opportunities for learning, and this leads to the achieved functioning of being educated, and this functioning contributes to them getting employed in the society. In addition, mobile phones provide access to social networking platforms which provides individuals the capabilities to build networks. Several individuals have joined various groups on social media and have participated in various discussions to fight for a collective cause and this impacts on their social inclusion. However, to generate some of these capabilities, the individuals will need to have enabling factors such as mobile literacy skills, access to the internet and so on. Such examples illustrate the impact of mobile phones on both individual and collective capabilities that foster social inclusion.

To answer our research, we empirically apply the CA framework to explore how IDP use mobile phones in Nigeria to generate individual and collective capabilities, which in turn promotes their social inclusion.

3. Methodology

In order to gain insight and understanding of how IDP use mobile phones to enhance their social inclusion, our empirical findings are based on qualitative interviews conducted with IDP in Nigeria. The research design was a single case study due to the uniqueness of the case; there is limited information on mobile phone use by IDP in Nigeria. The fieldwork in June 2019 involved interviews with resettled IDP living in the Bama/Gwoza IDP camp in Abuja.

The camp is located in one of the slums in Durumi, a remote area in Abuja. It is a private camp that was founded by a group of IDP in 2014 and has approximately 3000 IDP who left the Bama and Gwoza communities in Borno State due to the Boko Haram insurgency. The IDP camp is congested and lacks basic health amenities, hygiene, education, food, shelter and electricity supply. Internet connectivity is unreliable inside the camp due to the lack of fibre optic cable installation in the Durumi community, where the camp is located. There are approximately 502 households in the camp, consisting of adults, youths, children and orphans. The householders have various sources of income, and about 80% of the households earn less than 20,000 Naira ($25) per month. Sources of income for women are traditional cap making and petty trading; sources of income for men are building, tailoring and farming. The IDP are also involved in other menial jobs such as labouring and the women provide cleaning and nanny services. The educational levels in the IDP camp vary from primary school to a university degree.

The first author, in collaboration with an indigenous non-government organization (NGO), identified one of the leaders of the Gwoza/Bama IDP camp. He was chosen as the leader of the camp because he is elderly and also a religious leader whom the IDP tends to listen to and trust. The leader assisted further in the identification and recruitment of 21 participants for the study. To be eligible to participate in this study, participants needed to: (a) be eighteen years or older, (b) have owned or own a mobile phone and (c) self-identify as an IDP. Before the data collection process, the participants were provided with an information sheet and a consent form to sign, and the author also explained the contents to those who lacked the literacy skills to understand the documents. Pseudonyms were used for the participants in order to preserve confidentiality and anonymity. Interview questions were designed using the concepts of the Capability Approach: the background of the IDP; questions about their social inclusion; how they use mobile phones to generate capabilities; their achieved capabilities and the challenges impeding their use of mobile phones to enhance their capabilities.

During the data collection process, a short survey was administered to gather information on participants’ demographics, their ownership, and use of mobile phones. Seventeen of the participants were male and 14 were female. The participants’ ages ranged from 20 to 56. Among the respondents, 2 were in their 50s, 12 were in their 40s, 11 were in their 30s, and 6 were in their 20s. All participants had experience with using a mobile phone. Eighteen of the 21 participants owned a mobile phone at the time of the study, 2 reported they had lost their phones and 1 had reported his phone stolen.

Three types of phones were used by the IDP: the basic phone for voice call and SMS, usually without internet connectivity; the enhanced basic phone, which supports selected applications such as games and a limited web browser and the smartphone. A few were not comfortable with using smartphones as they found them too complicated. The participants had been using mobile phones for two to eight years. For those who had smartphones, the most common applications they reported using were Facebook and WhatsApp.

All the selected IDP participated in a face-to-face interview at one of the converted meeting rooms at the IDP camp. One of the authors has extensive knowledge of Nigeria and is fluent in the Hausa language used when conducting the interviews, which were all audio-recorded. Due to the fact that the participants had suffered a series of traumatic events, we ensured that our interaction with them was similar to a relaxed family conversation where the participants laughed and shared their experiences of life before and after the insurgency, and their experience of using mobile phones to promote their social inclusion in their host communities. Examples of topics that facilitated the relaxed conversation were a discussion about the beautiful mountains that exist in Gwoza, a region the author visited during his employment in the North East, and the local food eaten there. The interview sessions lasted between thirty minutes and an hour, depending on the richness of the data that could be gathered. The principle of data saturation was applied; after engaging twenty-one participants, the interview process was ended as no new data would be revealed from further probing.

At the end of the study, each participant was given 3000 Naira ($8) as a gift to thank them for their participation in the study. Also, the camp has a document containing information about the camp, such as the population, local government origins of IDP, gender, number of families and occupation. This document was analyzed to learn more about the research context. The use of different sources of data ensured triangulation which helped increase the credibility and validity of our results. Before the first author left Nigeria, he revisited the camp to thank the participants and also to share a summary of the findings with them. This was to provide transparency, ensure the findings were accurate, and to validify the honesty and integrity of the researchers. The participants agreed with the findings of the study.

Overall, a total of approximately nine hours of interviews were conducted; 24 pages of interviews were organized, translated and transcribed by the first author. The qualitative data was analyzed by both authors using principles of reflexive thematic analysis. This process began by carefully reading and re-reading the transcribed data in order to identify consistent themes discussed by the participants. Next, coding of transcript data began while revisiting the data as well as the existing literature around the emerging themes in order to clarify any ambiguities. After coding was completed, the different coded extracts were sorted into themes. Finally, the themes were reviewed by both authors to ensure that they reflect the topic of the study but with careful attention given to emergent topics. At the completion of the coding exercises, we produced our report as presented in the research context and analysis section. Significant quotations and relevant themes from the transcripts are provided in to clarify the coding exercise.

Table 1. Sample transcript from coded data.

4. Case study findings

In this section, we present our findings around the main themes arising from the interviews that emerged from our thematic analysis.

4.1. Internal displacement in North-Eastern Nigeria

The Boko Haram insurgency started in 2009. The term Boko Haram means, ‘Western Education is prohibited.’ The group aims to create an Islamic caliphate in the North-Eastern region of Nigeria, which is made up of three states, namely Borno, Adamawa, and Yobe. The war between Boko Haram and the Nigerian army has led to protracted displacement of many people from their homes, resulting in a national humanitarian crisis. People have lost their homes, lives have been lost, livelihoods have been destroyed, loved ones have been kidnapped, women have been raped – and many have been forced into early marriage with insurgents – and hopes have been shattered. The Nigerian government has ordered civilians in affected communities to leave their homes and move to IDP camps.

According to the UNHCR, over 2.5 million people are displaced in Nigeria due to the insurgency and now live in IDP camps (UNHCR, Citation2019). The crisis has further worsened the economic situation of the North-Eastern states that are dependent on agricultural activities. With the ongoing war in the North-East, many of the IDP have re-settled in camps in the urban city of Abuja, located in North Central Nigeria and claimed them to be the new ‘safe haven.’

There are four government-sponsored camps in different locations, namely Lugbe, Area- one, Kuchigoro and Kuje. On arrival at these camps, many IDP find the living conditions unbearable and synonymous to other camps in the North East. In 2015, IDP in Kuchigoro staged a protest to denounce overcrowding, and the lack of food and basic amenities in their camp. Sadly, with the continued crisis, Abuja has continued to see an influx of IDP and the reason could be due to the Northern culture which is similar to that of the IDP who are from Borno State, and many are now developing their camp on any abandoned land available to them. In this study, we focus on IDP residing in the Bama/Gwoza camp, which is one of the privately owned IDP camps.

4.2. Bama/Gwoza IDP camp and social inclusion challenges

The IDP Camp has continued to see the arrival of IDP daily. One of the participants explained the influx:

Instead of going to IDP camps in Borno State, we decided to rather come to Abuja, which is a bigger city, and you know it is the Federal capital and has more job opportunities. So, when we heard that some of our friends from Bama and Gwoza had set up an IDP camp in Durumi, we decided to join them. As I am talking to you, more of our friends are on their way from Gwoza to come here.

The camp leader provided a brief of how the camp was set up and the economic challenges faced with regards to assistance from the government:

When we were kicked out of our communities by Boko Haram in 2013, we came to Abuja, but, you see, none of the four IDP camps set up by the government was ready to accept us because they were already overcrowded. The land where our camp is located was given to us by a good Samaritan with the condition that he could at any time ask us to leave. Since arriving here, we have not received any single support from the government as regards our livelihoods … no jobs, no health care facility, no schools.nothing..we are just lucky we share the same culture with the people in this community in terms of language, and we are also lucky that majority are Muslims like us; for these reasons, they could easily accept us.

The camp is not conducive for living and is in a very poor state. Most of the rooms in the camp are made of nylon bags and often get flooded during the rainy season, with many falling sick to malaria and various kinds of infection. The participants revealed that many are faced with anxiety and depression and do not have health care facilities within the camp, and are thus unable to access good healthcare due to the cost of transportation and distance. Many have had to rely on self-diagnosis and sometimes local herbs; pregnant women in the camp relied on traditional birth attendants for child delivery. One of the participants explained his displeasure as shown in the quote below:

Before the war, we had primary health care centres in Bama but now look at us, we have nothing; ourselves and the children in this camp cannot even see a nurse or a doctor because we cannot access basic health care. It costs almost 1000 naira to be able to get to the clinic in Apo and then you also have to pay the cost of consultation which many of us cannot afford … how much do we even earn a day? How much is medicine? Most of our women here receive less antenatal care and deliver at home because they cannot afford the cost of health care but thanks to one of the women who has experience in childbirth. She is the one that helps

Asides healthcare, the participants mentioned that they also faced discrimination, causing them delays in continuing their education. For example, some of the IDP who had started their higher education in Borno State were unable to transfer their courses to the institutions in Abuja. Excerpts from one of the participants are as follow:

Before the war, I was a diploma student at the college of education of Bama, but due to the insurgency our school was shut down. When I moved here, I wanted to transfer to one of the universities here in Abuja but I was denied my transfer. To my biggest surprise I was told it is because I am not an indigene of Abuja and I knew no one who was a politician who could stand for me. I’m not the only one in this position. Many of us have had to suspend our education for now, unfortunately

The issue of indigeneship not only affected the adults but also children in the camp who had their education interrupted and were separated from their classmates, teachers and school environment due to the outrageous school fees for non-indigenes. The participants noted that only children that are from the Gwari or Gbagi tribe are allowed to enroll without having to pay book fees, schools fees and other administrative fees as shown in the quote below from one of the participants:

What is difference between my kid and a Gwari kid? Are they not both Nigerians? But you see for us who are from Borno, we have to pay and we cannot afford it..they don't even pity us and consider that we are IDP. I am unhappy that my children might grow up uneducated and not work in one of these big government agencies in Abuja.

Although a makeshift school has been created for the school by an NGO for the IDP, the participants complained that the school is non-functioning due to lack of volunteer teachers and the deplorable state of the classrooms that result in the school being closed during the rainy season due to the lack of ceiling. The participants mentioned that the reason for their predicaments is due to the lack of care by the government and more importantly being abandoned by their political representatives who should be representing and calling the attention of the government to ensure they are well taken care of and supported to ensure they can resume back the normal life activities as shown in the quote below:

You see, even if the government don’t care about us, our representatives should. In the last election, these politicians came to this camp and took us back to Maiduguri to vote for them with all kinds of promises but today they have abandoned us and all they care about is their pockets and families.

Not to rely on the government and politicians anymore, many of the IDP have resorted to self-help using their mobile phones for promoting their well being and supporting their integration into their new community pending when they are able to return back home.

4.3. IDP, mobile phones, and income generation

Very few of the IDP has been able to secure a meaningful job in Abuja; they often face discrimination and competition with the local workers. Many have had to accept insecure jobs with a lower pay of a daily average of one thousand nairas ($2), which is insufficient to cater for their health, housing, education and family needs. To be self-sufficient and stay employed in the community, some of them have taken up the use of mobile technologies as a means to generate income to meet their immediate needs. One of the male participants, who was a painter back in Bama and unable to get a permanent job, now has an umbrella stand for selling mobile recharge cards, and phone accessories. He noted that:

Prior to coming here, my friend who came before me told me to come prepared because life in Abuja for IDP was very difficult due to the high rate of poverty. With my little capital, I set up this kiosk..Most people around camp patronise me especially when buying airtime or phone charger. This is what I will do for the meantime before I get a permanent job.

Other IDP saw mobile phone services as an opportunity to also help family members generate income to help themselves without putting them at risk. One of the male participants mentioned buying and sending a phone to his mother so that he could be sending her money through the transfer of mobile credits which she then converts into money by selling it to mobile phone users in her neighbourhood. He noted:

The bank in Bama village has been destroyed by Boko Haram and the roads are not safe, so it’s difficult to send money back home. Every month end, I send her[mother] 5000 naira credits and when she receives it, my cousin helps her sell it to neighbours whenever they need airtime. She uses it to generate income to support herself and immediate family members living with her.

However, an increase in robbery and stealing around the camp has affected economic activities within the camp. The participants noted that there is at least an incident of robbery every day and this was due to the lack of secure fencing around the camp. These robbers usually infiltrate the camp at night to target shops and the warehouse where donated items are stored. When attacking IDP, their interest is restricted to cash and portable items such as mobile phones, radios and watches. The perpetrators who engaged in these criminal activities are both IDP and individuals from neighbouring villages who have no source of income due to the high rate of poverty in the country. One of the participants, a male mobile airtime seller who was robbed of his money and mobile phone noted that:

Last month, I was sleeping in a room when two robbers broke into my room. On seeing me, the first thing they asked was to give them my mobile phone and the money I had made from the day’s sale. The incident really affected me as it was my only source of livelihood; it took almost a month before I was able to get a loan to buy a new phone and get back to business.

4.4. IDP, mobile phones, and social support

Apart from the financial challenges they encountered in the camp, IDP lamented that the violent and traumatic events they experienced during the war and displacement to the camp had affected their mental and emotional health. The participants mentioned torture, killing, and abduction as the frequent traumatic events they witnessed that resulted in obsessive thinking and insomnia. According to one of the male participants:

I lost my immediate family members during the war. I was lucky because I hid in the ceiling of the house. I am yet to recover from that event; sometimes, while people talk to me, I zone out. I think too much and I am scared for my health because of my blood pressure.

Some Non-Governmental Organisations (NGO) have sent community-based counsellors to provide support to the IDP. However, this support is usually not enough, and many have adopted the use of their mobile phones to help with this. Maintaining contact with family and friends was very important to many as it helped them gain emotional and psychological support to carry on with their daily activities. This was also a major reason for the use of mobile phones by the majority of the participants. One of the male participants noted the use of mobile phone to track the situation of family members:

The only reason I bought it is to keep in touch with my family especially now that they are all scattered around the country due to the insurgency. At least every two days I reach out to my pregnant sister and mum back in Gwoza. I left them because they could not run away through the high mountains. Talking to them makes me happy and reduces my stress and allows me to at least focus whenever I go out searching for my daily job as a labourer.

However, there were several occasions when communicating with loved ones could be difficult due to the inadequate network coverage in the camp, and this has resulted in some of the participants owning more than one SIM card; if one network provider was down, they can simply switch to the other SIM card. As well as this, the participants complained that sometimes it can take up to 10 days before they can connect with their loved ones in Bama due to the inadequate network coverage in the area resulting from the excessive bombings and vandalisation of telecommunication networks by the terrorists:

In Bama, the network is terrible. Only the Glo mobile network works there and to get a good signal you need to go to the top of the mountain. The journey to climb the mountain is tedious, and there is a risk of being kidnapped by Boko Haram members.

Mobile communications are also used by IDP to locate and connect with loved ones. Sharing of mobile phone numbers are regularly used by the IDP to find missing friends and family members. The separation from family and friends has had an adverse impact on IDP’s health and well-being. One of the participants reported how having a mobile phone helped her locate her mum:

I gave my number to my friend who moved back to Bakassi camp in Maiduguri and on getting there, she gave my number to someone who knew me and then that person was actually sharing the same shelter with my mum in the camp. One day I was sleeping when I heard my phone ring and it was my mum’s voice.

Also, the IDP described the significance of the Church and how beneficial it is to their emotional and social well-being. On arrival in Abuja, many of the IDP were able to connect with the churches which they attended back in Borno State. These churches usually have branches across the country and the majority have a special WhatsApp bible study group specifically for members who are unable to attend the church in person. Many of the IDP are members of this WhatsApp group due to the high transport cost of going to church. The IDP mentioned that depending on the church, the WhatsApp bible study group runs on selected days. The Pastor joins at a specific time and sends voice notes of the day’s sermon. Later on, there is an open discussion with other members about the reading of the day where everyone types in their questions and gets a response from the Pastor. There are also discussions on how the teachings of God apply to their daily lives. One of the female IDP mentioned that she had to save money to buy a smartphone in order to be part of the WhatsApp bible study group. She mentioned how being a member of the group has helped her mentally and socially:

The Bible study has impacted seriously on my life and has helped heal the pains in my heart. Every Sunday, I know there are people out there that will be around me in the spirit to cheer me up and remind me I am not alone and will pray with me that I am reunited with my parents and siblings.

4.5. IDP, mobile phones, education and political support

The Boko Haram insurgents disrupted access to education, especially for young IDP, by destroying schools, and kidnapping and killing students and teachers. Despite this, some have made a conscious effort to further their higher education, specifically the male IDP. The female IDP were mostly taking care of the children and the homes. Few of the IDP who had completed their secondary school education had enrolled for an online degree program with the National Open University in Nigeria (NOUN). With the help of their mobile phones, participants are able to continue their higher education learning and graduate as shown in the quote below:

‘While in Bama, I had already started my diploma programme in Psychology with the polytechnic but due to the conflict, our school was shut down and we had to flee … I thought that was the end because I was unable to transfer my credits to university of Abuja but luckily for me the National Open University of Nigeria accepted me for a degree in mass communication. I graduated last year and I am now doing my internship in media company here in Abuja

Apart from learning, politics is very important for many of the participants and was often discussed in terms of how politicians have failed to address the challenges faced by IDP after voting them into office. During the run-up to the 2019 elections, many of the IDP became active on social media and WhatsApp groups in order to follow the news on electioneering campaigns in Borno state and engage with other political actors since they were no longer residing in the state. One of the participant mentioned:

Every day I log into Facebook mobile and WhatsApp to the Borno political group to see the exchange of information between the supporters of various candidates and including the aspiring candidates themselves … I also contribute to the topics of discussion and ask supporters of these candidates questions based on their manifestos. It is always interesting to see that many of the political candidates read our comments and respond to the majority of the issues raised.. The problem is they just listen and make empty promises’.

Other IDP normally call their friends through their mobile phones to discuss the political situation during the 2019 elections:

I used to be a ward exco member of APC so I am so excited about the election and each time I have credits, I usually call my other ward members in Maiduguri just to find out how our party candidates are doing and give my opinion on how our party can better the lives of the people in Borno.

Few days before the election, some of the IDP were offered money by the politicians who were seeking political office and transported in an unescorted convoy back to Maiduguri – a journey through towns that are known for attacks by Boko Haram. For some of the IDP who couldn’t take the risk of going, they used their mobile phones to monitor the results on the day of the election. One of the male participants mentioned:

We simply went on Facebook to monitor the discussions on the day of the election. Many people were posting the results of their polling unit. We used that information to assess how our preferred candidates were doing.

A surprising number of participants maintained that, since winning elections and being sworn in, many of the politicians had abandoned them and failed to keep to their election promises despite the sacrifices made by IDP to embark on a dangerous road journey to vote for them. The IDP came together to form a group called ‘The concerned Abuja IDP’ and as a group, they started calling out non-performing politicians on community radio programmes and social media platforms as shown in the quote below by one of the participants:

Since after winning the election, our representative does not pick up our calls nor reply to our messages. To get his attention, we decided to use Facebook which has his public profile page, with the support of the public we criticized him on his Facebook wall. We also reported him of his negligence and how he has abandoned his constituents to the popular community radio programme. Due to the pressure and the negative media coverage on him, he decided to join the show two weeks ago to explain himself, and we spoke to him live on the show, reminding him of the problems we faced as IDP which he promised to deal with.

The IDP were active listeners of this community radio programme which is focused on human rights and empowering vulnerable communities. The radio programme partners with a major network provider so listeners can call or message for free. As a group, The IDP mentioned calling in on several occasion to ask questions on how they could participate in the election due to their displacement and also voice their concerns about the state of their condition in the camp and also contribute to any topic they could relate to as IDP as shown in the quote below:

Majority of us listen to the popular Brekete family show here in the camp. Every Tuesday you will see many IDP sitting together using their phones to listen to the programme. The show has been very helpful in educating us about our rights here in Abuja and most importantly giving us a chance to call and explain our situation. The radio program is like a platform we have continued to use to call the attention of the government, that is if they are even listening.

4.6. IDP, mobile phones, donation and fund-raising

The participants mentioned that mobile phones enabled them to seek donations from the public using social media applications. This is very critical to the IDP who are solely dependent on external help from private individuals and charity organisations due to the lack of formal assistance from the government: ‘we need serious help and you know what, this help is not as big as what we have lost from the insurgency’. One of the participants exemplified the use of Facebook via their mobile phones to request for donations from the public. Many individuals and NGO who saw their campaigns on Facebook contacted them and physically visited the camp to donate cash and relief materials as shown in the quote below:

We created a Facebook page containing the camp information, pictures and what we are in dire need of. Through it, we seek donations from the public by sharing our campaigns in several groups. Also, we agreed that IDP who have a Facebook account should also keep sharing our page which has also helped. Most of the donations such as food, mattresses and so on we have received in this camp are mostly from people who saw our campaigns on Facebook and made efforts to visit us to make these donations.

Seeking financial help from others was described as being a vital function of the mobile phone. Since they arrived at the camp, this function had become even more important due to the continuous financial challenges faced by the IDP. As one participant noted: ‘Since the government won’t support us, at least we have other ways to seek for financial help but it’s not easy especially due to the economic situation of the country now, a lot of people don’t have money.’

Another participant depicted the mobile phone as a tool that has been effective in crowdfunding key projects in the camp. Specifically, he explained how they were able to raise money to finance the building of the camp meeting room by requesting individuals to contribute to the cause using their Church WhatsApp group:

Through the Church WhatsApp group, we posted an appeal to build a small community hall in the camp. Members helped us further share our appeal to their other groups and we heard the pastor even made an appeal during the church services. The church collected the money on the camp’s behalf and handed it over to the camp leader. The money was used to build the camp hall which is used for social gatherings. The project was so helpful as it also gave some of our IDP a temporary source of income since many of them were employed as labourers during the construction.

4.7. IDP, mobile phones, and gender inclusion

Prior to the insurgency, the majority of the women participants mentioned that they were primarily engaged in farming and taking care of the home. The men are usually the decision makers of the family. The participants mentioned that they were secluded (Kulle in Hausa language) in their homes and subject to the will of their husbands, and had no formal education. With the war, many of the women participants have been widowed while many daughters have lost their parents. Having fled their communities to the IDP camp in Abuja, many of these widows and orphans have had to change gender roles by safeguarding and helping their families and themselves to survive in the midst of their challenges. In this process, they have found mobile phones useful in providing them with opportunities that would be difficult to acquire prior to the Boko Haram insurgency. The women participants mentioned using mobile phones to support their business by allowing them to market their products and connect with customers. One of the participants, who is a widow and has two kids, mentioned the impact of mobile phone on her traditional cap-making business and how it has helped her expand her customer base:

Back in Bama, I made local caps for my immediate family members … My late husband wouldn’t want me to sell it in the market because he didn’t want men to interact with me. On arriving here, I have been making them for sale in order to survive. I also started using WhatsApp to market my designs, and this made my business really grow. I have regular customers that call me to place orders and then come and pick it up, similarly I call them when I have new designs in stock.

The women also asked their existing customers to share their mobile phone numbers with friends. They mentioned that they received random calls from several potential customers as a result of referrals and when they got the details of the customer’s cap specification, they usually negotiated payment for pick up. The transactions are usually cash driven as many of the women did not have bank accounts and were unable to open one due to their lack of identification card. The participants mentioned that while leaving the village in Borno prior to the insurgency, many of them were unable to obtain a national ID card because it was too expensive for them to go to the city, or even pay to get documents such as an indigene certificate which was a requirement for getting a national ID card; also, the majority of them did not see the point of having one. And since arriving into the camp, there has been no progress made to provide them with any form of identification. Although sometimes, they usually ask their friends who had bank accounts for their permission to receive payments using their bank details. Once payments were made by the customers to the provided account and it had been confirmed, they then send the product:

There are some customers who are not living in Abuja so whenever they make an order, I send their order with one of the drivers in the local park and the customers usually pay me through my friend’s account; once she receives the alert she informs me.

The women who were not involved in trading practices engaged in hair braiding, cleaning and nanny services. Many of the women advertise their services by having their numbers written on the wall of the IDP camp. The women mentioned that people within the city usually come around the camp looking for those services since the IDP provides cheaper services. They also snowballed customers by asking existing customers to share their numbers with their friends and family members.

The mobile phones were also used to access federal government loans. The women explained that they use their mobile phones to apply for government zero collateral loans targeted at women engaged in petty trade. One of the participants who sells sachet drinking water explained how she benefited from the loan which helped her expand her business:

When I heard about the loan on radio, I had to immediately buy a small mobile phone and recover my sim card in order to register for the scheme. When we were running away, I lost my phone. Two days after registering, I received a text that a mobile wallet account has been created and I should come to the bank to verify my account using my national ID card. Before I bought one bag of pure water to sell, but now that I have this 10000-naira loan I buy like 4 or 5 bags to meet more customer requests especially during this dry season.

Interestingly, the women were active listeners of radio programs using their mobile phones. Even if they did not have one, they usually shared it with their friends. Particularly, the women mentioned listening to Kakaki radio which had a weekly women interactive program for women that was beneficial in informing and discussing issues and interests that affected their daily live activities. Some of the topics the women mentioned that were discussed in the program includes; domestic violence, genital mutilation, marriage, business and women participation in politics. The women mentioned that the radio program provided them with the space to participate in public life, educated them, and gave them a chance to contribute to the discussion by calling into the program. As one of the women noted: ‘The radio has made many of us re-discover ourselves in the society now.’

Also, many of the women mentioned that since purchasing a mobile phone, many of them learnt how to use it by themselves, which was very beneficial to them. As one woman explained:

Even though I do not really speak very good English, at least I know how to type and save a person’s name. With this, I know how to send messages and call my sister and neighbours. I also open the radio program immediately after my morning prayers to listen to BBC hausa and sometimes I also use this phone to call my daughter’s teacher to find out about her learning in school and sometime they also call me in case they want to tell me something extra my daughter will need for school

However, some of the women mentioned that the high cost of internet bundles and not always having enough charge in their phone due to lack of electricity in the camp, hinders their use of mobile phones.

5. Analysis

Drawing on the human capability approach to development, Sen’s concept of commodities, capabilities and conversion factors were used as pillars for the case study analysis to understand how IDP use mobile phones to enhance their social inclusion of IDP as shown in the .

5.1. Commodities

As shown in , the mobile phone is a commodity relied on by IDP to enhance their social inclusion. Mobile phone features such as voice call and SMS were relevant for communication. The inbuilt radio matches the needs of the refugees in the context of accessing information and providing them with a platform for participation with local community radio programs using voice call and SMS features. Smart phone features such as web-browsers were relevant to the needs of refugees in the context of e-learning. The ability to access social media applications such as Facebook and WhatsApp were also relevant in fulfilling their needs towards social inclusion.

5.2. Capabilities

The findings of the study showed a number of individual and collective capabilities provided by mobile phones that enhanced the social inclusion of IDP in their host community.

5.2.1 Individual Capabilities:

5.2.1.1. Opportunities for social Connections

From , mobile phones provided IDPs the opportunities to maintain and build new social connections. Specifically, the findings of our study showed that IDP used their mobile phones to keep in touch with family members despite their physical displacement. The value of these relationships is evident in their use of mobile phones to call or send SMS to both immediate and extended family members who are a primary source of information to the IDP. IDP relied on mobile phones in searching and reuniting with loved ones they had lost connection with while fleeing from the conflicts. Also, considering that some IDP were not able to flee due to several reasons such as old age or being pregnant, many IDP who were able to flee used their mobile phones to keep track of those left behind and support them both mentally and financially. In addition, mobile phones provide IDP with the opportunities to build new connections. The value of building these new relationships is shown in the use of social media applications such as Facebook and WhatsApp to build new virtual networks and seek donations. More importantly, maintaining and building new relationships with family and friends and being members of the Church WhatsApp group was a source of emotional and psychological support for many IDP during these difficult times and this is a critical achievement that was realised via the use of mobile phones by IDP and relevant for their social inclusion.

5.2.1.2. Opportunities for economic participation

The use of mobile phones by IDP contributed in boosting economic activities in their host community. Mobile phones provided IDP with the freedom to run small businesses and generate income through ancillary services. On the part of family and friends, monies generated by IDP using mobile phones also provided them the opportunities to send money to their family members back at home, which in turn enhanced their capabilities of participating in the economy and also maintaining existing social relationships. Being self-employed and engaging in the exchange of goods and services within and outside the community using their mobile phone is a value achievement that is relevant to the social inclusion of the IDP. Interestingly, the use of WhatsApp by the women empowered them to advertise and run businesses, engage with customers, and expand the geographical scope of their business transaction. Also, the women relied on their mobile phones to access interest-free loans from the government, which has provided them with their economic independence. Thus, the achieved functioning of women being employed and becoming loan beneficiaries via the use of mobile phones has contributed to the financial inclusion of women.

5.2.1.3. Opportunities for learning

Findings from the case study showed that mobile phones provided learning opportunities for the IDP. The IDP used the mobile phone as a platform to establish connections with the local community on the radio programs and also enhance their knowledge about women empowerment, civic rights, religion and political participation. Also, for some of the IDP who were interested in furthering their education, mobile phones provided them the opportunity to obtain a university degree online. The functioning of being a graduate has allowed some of the IDP enter the labour market and become self-sufficient economically. Self-learning on how to use the mobile phone was very prominent with female IDP, with the majority of them having to own a phone for the first time because of the insurgency. Attaining the functioning of being mobile literate helped the IDP in not only reaching out to family members and friends but also interacting with teachers of their children in order to monitor and support the learning of their children.

5.2.2. Moving from individual capabilities to collective capabilities

5.2.2.1. Opportunities to participate in political activities and crowdfunding

Mobile phones provided IDP with the individual capabilities to participate in political activities. Specifically, mobile phones provided the IDP with access to social media and information about political candidates, their manifestos and political parties, thus providing them with the opportunities to make informed choices from among aspiring politicians. For many of the IDP who were unable to return home to participate in the election, social media platforms such as Facebook and WhatsApp provided them with the opportunity to contribute to the discussion on election matters and also monitor election results. Becoming politically engaged was an important functioning the IDP valued as it made them express and exercise their views on issues regarding the elections and many also expanded their knowledge and relationships with other political actors on social media especially as they have been excluded from participating in the elections due to their displacement.

In addition, the findings show that IDP also came together and achieved the functioning of a group that was able to use their mobile phones to participate in the local community radio program targeted as educating the vulnerable communities about their civic rights, teaching them how to vote and actively participate in the electoral process of Nigeria. As a group, the IDP were able to call in or text in during radio programs where they achieved the functioning of voicing out their concerns on their needs and their social, economic and political condition in their host communities, reaching out to their political representatives and scrutinizing their activities, thus empowering them to influence and push for adequate political representation. By acting collectively, the findings show that IDP were able not only to voice out their individual concerns but also to call the attention of the government and their political representatives. Hence enhancing their individual and collective well-being simultaneously.

Lastly, the findings of our study showed that many of the IDP became members of their church WhatsApp group. Using this WhatsApp group and their existing social media networks, they were able to facilitate their collective action of seeking donations and help from the public online. The IDP, through their coordinated collective action were able to use the donated funds to build a community hall where social gatherings take place. The construction of this community hall resulted in IDP gaining collective capabilities in the form of temporary employment as laborers.

5.3. Conversion factors

As shown in , conversion factors influence the capabilities that can be derived from the use of mobile phones by IDP in the context of social inclusion. Institutional support is a social conversion factor that provides IDP with the ability to develop social connections using their mobile phones. Particularly, the support from the church is a factor that enabled IDP to use the Church WhatsApp groups to crowdfund, build and maintain social relations with other church members albeit virtually.

However, some participants were unable to use their mobile phones to generate the capabilities for social connectedness due to the lack of social conversion factors. Environmental factors such as poor network coverage that is partly as a result of the bombing of telecommunication infrastructures by Boko Haram insurgents, indered the ability of IDP to keep in touch with friends and families back home who could not escape. This, in turn, reduced their well-being and freedom of receiving emotional and psychological support from friends and families.

Also, the free of charge call in and text provided by the radio stations (environmental factor), literacy and access to phones with inbuilt radio or radio and having data bundles (personal factors) influence the ability of IDP to participate in political activities. Also, social class as determined by key personal conversion factors such as literacy and education influences the ability of IDP to use mobile phones to participate in educational programs to further their education.

Of course, the ability to generate economic capabilities in terms of running small businesses and generating income through ancillary services required IDP to have some personal funds and literacy, which can be regarded as a set of personal conversion factors. Although criminal activities, which is a social conversion factor, reduced the well-being freedom of some IDP from deriving these capabilities. However, for some women, the lack of personal conversion factors such as lack of a form of identification and not having a bank account contributed to reduced well-being and freedom on some of the women, in terms of accessing government loans.

Our findings further indicated that conversion factors are not static and can also have an influence on the decision of IDP to use mobile phones. Referring to the case study findings, many of the women participants became widows due to the loss of their husbands during the insurgency. As widows, many of them had to change gender roles by safeguarding and supporting their families. The change in these female gender roles (personal conversion factors) has influenced their decision to use mobile phones to live a valuable life. However, the cost of internet bundles (personal conversion factor) and lack of electricity (environmental conversion factor) were factors that hindered the ability of IDP from generating capabilities using their mobile phones.

6. Discussion

To answer the research question, ‘How do IDP in Africa use mobile phones to enhance their social inclusion?’, we undertook a study of the use of mobile phones by selected IDP who had fled the Boko Haram insurgency in Nigeria. Using CA as a theoretical lens, our study showed that IDP used their mobile phones to generate both individual and collective capabilities that led to their social inclusion. The individual capabilities are opportunities for social connections, opportunities for economic participation and opportunities for learning. The collective capabilities that are derived through collective actions are opportunities to participate in political activities and crowdfunding. In addition, we discussed the conversion factors that influence the generation of these capabilities. summarizes our findings in relation to the concept of CA. In the following section, we discuss the implication of our study theoretically and practically.

6.1. Implic ations to theory

This research responds to calls for further studies into the use of mobile phones by IDP to improve their social inclusion (Abujarour et al., Citation2021; Mancini et al., Citation2019). The study makes a contribution by moving away from the dominant focus on refugees and migrants living in the global north to focus on internally displaced persons in SSA (Sabie et al., Citation2019). In this context, IDP are exercising their agency to use mobile phones in ways that can enhance their social inclusion phones in an environment where they have been neglected and are faced with a high degree of socio-economic instability. In this sense, understanding how IDP use mobile phones to enhance their social inclusion in Africa, where there is an increasing number of IDP due to ongoing conflicts and where protracted displacement has become a characteristic of the continent for over 20 years, is critical (Hounsell & Owuor, Citation2018). As such, we investigate how IDP in Nigeria generate capabilities from the use of mobile phones to enhance their functioning in the community, as well as the factors that enable or hinder their abilities to use their mobile phones for social inclusion purposes. Within the context of displacement, unlike refugees that have secured support, protection and assistance, IDP resort to self-help to overcome the challenges of social inclusion.

Theoretically, we adopted Sen’s CA to conceptualize social inclusion in terms of capability enhancement. To address the critique of Sen’s CA of its emphasis on individuals, we incorporate the concepts of collective capabilities (Ibrahim, Citation2006; Pelenc et al., Citation2015). Our findings reveal that mobile phones serve not only as a self-help commodity for IDPs to overcome disconnection from their communities but also as a means to enhance their individual and collective capabilities, which in turn fosters their functioning in their host community. The findings of the study have shown that IDP used their mobile phone to generate three individual capabilities to enhance their social inclusion as identified by previous studies in the refugee context.

The first individual capability includes opportunities for social connections. IDP used their mobile phones to maintain ties with friends and family members back home and also to build new relationships. This reflects the findings from other studies on displaced people that show that mobile phones enable refugees to connect with loved ones and re-establish a network (AbuJarour & Krasnova, Citation2018; Díaz Andrade & Doolin, Citation2016. These good relationships were important for the well being of the IDP, as it contributes to their sense of belonging and good mental well being to function well in the community. Keeping in touch with friends and families using their mobile phones is also a source of psychological comfort for displaced people that alleviates social isolation and emotional stress in a new environment (Díaz Andrade & Doolin, Citation2016). This also reduces the impact of uncertainty about the general circumstances and well-being of friends and family members they have left behind (Bacishoga et al., Citation2016).

Although refugee studies show that newly arrived refugees usually face challenges such as language, cultural knowledge and social network, which hinders successful social connectedness using mobile technologies (AbuJarour et al., Citation2018). These challenges do not necessarily apply in an IDP setting as shown in our findings where IDP could easily use their mobile phones to connect with new members of their church due to the existing relationship they had with the church as members while in Borno and also connect with the local communities who shared the same norm, religion and culture.

Another individual capability we identified is the opportunities for economic participation. IDP were able to participate in the economic activities of their host community. Mobile phones provided them with opportunities to run small businesses and generate income through ancillary services. Being self-employed enabled the IDP to integrate into and function in the local economy. Previous studies show that access to income-generating activities enable refugees to participate in a country’s economy and build a stable lives for themselves and their loved ones (AbuJarour et al., Citation2018; Bacishoga et al., Citation2016).