ABSTRACT

Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) are considered a cross-cutting tool that contributes to meeting the global challenges set out in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). However, in many countries, there is still a significant connectivity gap between cities and rural areas. Using a case study approach and the Digital-for-development paradigm proposed by Heeks, this paper explores an innovative strategy for addressing the rural connectivity gap and examines its impact on the SDGs. The model under analysis is the Rural Mobile Infrastructure Operator (RMIO). The specific case analyzed is the first company operating under an RMIO figure and offering services in underserved rural areas of Peru. The results show that the RMIO strategy primarily contributes to some specific targets of SDGs 3, 9, and 17. Key stakeholders can use the methodology and results of this study to develop strategies to address the connectivity divide and promote the achievement of the SDGs in rural contexts.

1. Introduction

The premise of the 2030 Agenda for achieving its 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) is to ‘leave no one behind’ when it comes to promoting economic, social, and environmental progress. This principle addresses the global inequalities that exclude a large part of the population from fully exercising their rights. Among these inequalities, the development gaps between urban and rural areas stand out (Sieber, Citation2019).

The Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC or CEPAL in Spanish) states that:

In Latin America, it is not the same to be born and live in one place than in another. The place of residence determines the socioeconomic conditions and the possibilities for accessing goods that guarantee well-being. This rule applies both among countries and within them, because there are countries that have achieved higher levels of growth but where this growth is concentrated in only a few territories. (ECLAC, Citation2012)

About 20% of Latin America's population resides in rural areas, and this group is composed mainly of original indigenous peoples. Along with their languages and specific social practices, the territory they inhabit is one of the fundamental traits that defines them, revealing the alliance between environment and ethnicity in perpetuating social inequalities. Many of these territories are places where they took refuge or to which they were relegated during colonization. Since then, they have suffered from infrastructure deficits due to political and social exclusion (ECLAC, Citation2006). The isolation in which they live is not only due to the physical distance from other localities but also to insufficient or nonexistent public support, little investment, and a severe technological lag that further accentuates these gaps. The problematic characteristics of the territory and the scarcity of infrastructure raise the costs of setting up other fundamental services that can improve the quality of life in these regions. The population mainly engages in agriculture, fishing, and crafts has a low-income level and is usually forced to migrate to urban areas. The urban-rural gap is reflected in several indicators related to the SDGs, such as high maternal and infant mortality, malnutrition, few employment opportunities, a greater feminization of both poverty and child labour, and severe limitations in access to essential services such as education, healthcare, water and sanitation, energy, transport, and telecommunications (PAHO, Citation2018). These factors make rural populations more vulnerable, perpetuate the cycle of poverty, and pose a challenge to achieving the SDGs.

1.1 Rural connectivity

Communications infrastructure is a critical element for the adoption of technological innovations that can play a crucial role in driving the achievement of the SDGs (Sachs et al., Citation2016; Tjoa & Tjoa, Citation2016; Wu et al., Citation2018), as part of the so-called ‘Fourth Industrial Revolution’ (artificial intelligence, blockchain, 3D printing, biotechnology, internet of things, etc.). This revolution has the potential to dramatically increase the productivity of national economies (AfDB, ADB, EBRD & IDB, Citation2018). However, the innovation index in Latin America is 34.54, three points below the world average (37.99). Among other factors, this is due to the digital gap (COTEC, Citation2017). According to the World Bank, a 10% increase in mobile phone penetration can lead to a GDP growth of up to 6%, also impacting other aspects of the economy, such as job creation or productivity. Furthermore, some studies (Bhavnani et al., Citation2008; Labonne & Chase, Citation2009; Baro & Endouware, Citation2013; Hossain & Samad, Citation2020) establish a relationship between improving connectivity and its positive impact on living conditions and income levels. Moreover, using ICT to reinforce public services such as healthcare (Dutta et al., Citation2019) or education (Aristovnik, Citation2012) also has great potential. Meanwhile, Corbett and Mellouli (Citation2017) stress the role of ICT in achieving sustainable cities. All this explains governments’ interest in promoting ICT access, which is still a challenge in many parts of the Iberoamerican region. The importance of telecommunication services has even increased during the COVID-19 pandemic, becoming essential in many areas: from access to basic services such as healthcare or education to finding a job or carrying out administrative procedures (Tropea & De Rango, Citation2020).

According to an Inter-American Development Bank study (Citation2017), land-line broadband penetration is 10% in the region, compared to an average of 28% for countries belonging to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). Regarding mobile broadband (3G and 4G), penetration reaches 30% of the population, also far from the average for OECD countries, which is 72%. The region also faces quality problems, with an average speed considerably lower than in OECD countries, both in mobile and land-line connections (Prats Cabrera & Puig Gabarró, Citation2017). Furthermore, according to this same study, services are not very affordable: 40% of the population with the lowest income would have to dedicate 10% of their monthly income to telecommunication services, compared to 3% of the salary of the same segment population in OECD countries.

Access to telecommunication services is also significantly different among countries within Latin America. For example, there are practically no 4G services in the Caribbean, while its coverage reaches 36% of the Southern Cone population, 22% in Central America, and 20% in the Andean countries. In terms of households with internet access, the average for the region (44%) is approximately half that of OECD countries (81%). Again, there are relevant differences between several subregions: Southern Cone (54%), Central America (34%), Andean Countries (34%), and the Caribbean (20%) (Prats Cabrera & Puig Gabarró, Citation2017).

Inequalities in access to telecommunication services are evident when comparing different nations, and also when analyzing the differences between rural and urban areas within countries. In this study, we focused on Peru, where, despite the growth of mobile telephony, only 14% of people in rural areas have internet access, compared to 55% in urban areas. These figures justify the need to find strategies that extend the coverage of telecommunication services to rural areas while maximizing their impact on the SDGs.

In the ICT4D field, more and more voices call for building cumulative knowledge on ICT4D and exploring the link between ICT and development (Sein et al., Citation2019; Zheng et al., Citation2018; Walshman, Citation2017). Different models conceptualizing this link have been proposed. In particular, Diga and May (Citation2016) adopt an ecosystem perspective and focus on the interactions of a variety of actors in a given institutional context. Other authors, such as Heeks (Citation2020), rather focus on analyzing different elements and their role in development.

This paper is based on the digital for-development paradigm proposed by (Heeks, Citation2020). Heeks identifies ‘three generations of digital infrastructure for development.’ The first is based on mobile phones, the second is based on the internet, and the third ‘will be based around a ubiquitous computing model of sensors, embedded processing, and near-universal connectivity and widespread use of smart applications.’ However, as already explained, disconnected communities do not have access to the first generation yet and, therefore, are far from accessing the other two. For this reason, it is necessary to explore possible strategies that can contribute to closing the connectivity gap, and at the same time, try to understand their contribution to development. To do so, we will begin with a review of previous work in this line.

1.2 Previous works

The connectivity gap between rural and urban areas is related to the business model of large operators, specifically Mobile Network Operators (MNOs), which serve urban areas (Cruz & Touchard, Citation2018). Their models are oriented towards settings with a high population density and are not efficient in rural areas with dispersed populations. Consequently, the implementation and operational costs of the MNOs are higher than the expected income, the investment is not attractive, and, therefore, rural areas remain unconnected. This becomes a vicious circle in which a lack of substantial benefits hinders the arrival of connectivity services, while the absence of connectivity services weighs down the opportunities of the population to obtain higher income and achieve the SDGs. This situation is aggravated when connectivity in cities improves thanks to new technologies such as 4G or 5G, thus widening the digital divide between rural and urban areas.

In recent years various alternatives have emerged that propose financially sustainable models for offering telecommunication services in rural areas. Some of the most innovative proposals are reviewed by Saldana et al. (Citation2017), who classified existing strategies into four groups: Community Networks such as Rizhomatica, Wireless Internet Service Providers, Shared Infrastructure Models, and Crowdshared Approaches. These models differ in purpose, the entity behind the network, the administrative model used, or the technologies employed. The feasibility and sustainability of some of these models have been analyzed in previous studies (Baig et al., Citation2018; Prieto-Egido et al., Citation2020; Simo-Reigadas et al., Citation2015), and the results are promising.

One of the controversial regulatory issues is the handling of mobile phone frequencies. MNOs have bought the rights to use these frequencies, but do not use them in rural areas where their operations are not financially sustainable. On the other hand, other actors such as community networks or Internet Service Providers (ISPs) would be interested in using those frequencies but are prevented from doing so by existing regulations. The Peruvian government opted for a strategy that seeks to balance this conflict and is known as the Rural Mobile Infrastructure Operator (RMIO), defined by Supreme Decree number 004-2015-MTC of August 2015. This strategy assigns to the RMIO the deployment and maintenance of the network in underserved areas. Meanwhile, the management of the client portfolio and the mobile phone licenses corresponds to the MNO. The RMIO can then specialize in deployment in rural areas without taking on tasks that MNOs already perform efficiently. Instead, the MNO is responsible for charging the end customers and shares part of the income obtained with the RMIO. In this way, the RMIO receives payment to cover the implementation and maintenance costs and justifies the investment it makes (OSIPTEL, Citation2017). Furthermore, under this framework, the RMIO can use the mobile phone frequencies that belong to the MNOs and are not being used. Although the RMIO model seems promising, up to the current moment, no study has been conducted to assess its actual impact in terms of development, and particularly in terms of its contribution to the SDGs.

This paper aims to identify and estimate the impacts of the RMIO strategy on the SDGs in Peru. From a theoretical perspective, this research proposes an innovative analytical framework and contributes to the stream of literature devoted to considering the contribution of ICT to development. Several practical implications are identified for other stakeholders, particularly policy-makers, to implement sustainable strategies that can contribute to the development of isolated communities.

2. Methodology

2.1. Research approach

This research follows a case study methodology, based on the analysis of a variety of data sources that offer detailed empirical descriptions of specific instances of a contemporary phenomenon, ‘the case’ (Yin, Citation1981). Case studies enable insights into complex relationships that can provide valuable pointers for addressing major substantive themes in a field (Yin, Citation2017) and are also helpful for theory building (Eisenhardt & Graebner, Citation2007). Case studies have been extensively used as a research methodology in multiple disciplines, including ICT for development (Musiyandaka et al., Citation2013; Tibben, Citation2015; Wynn & Williams, Citation2020). Particularly, the study adopts a single-case study methodology and concentrates on the case of Mayu Telecomunicaciones.

The research conducted is placed at the meso level and adopts the perspective of a particular actor, the RMIO operator. According to Qureshi (Citation2015), the meso or organizational level is of particular interest for ICT4D, as this kind of actor can become a key player in enabling ICT usage to support better livelihoods. Particularly, the use of ICTs by NGOs, small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) have received increasing attention as these actors are often more efficient and innovative than large corporations (Gibson & Van der Vaart, Citation2008).

It is worth noting that one of the research team members that developed the case was directly involved in the case under study. The research team also included external researchers. Hence, this study's methodology can also be considered as collaborative management research, i.e. an effort by two or more parties, where at least one is a member of an organization or system under study, and at least other is an external researcher, to work together in learning and to produce the necessary information (Lieberman, Citation1986). In this type of research, the researcher is not a mere observer but an agent of change who engages in cogenerating ‘actionable scientific knowledge.’

2.2. Case study selection

Mayu was established in 2016 and was the first company to operate under Peru's RMIO strategy. The Mayu case provides analytical material of particular richness and interest for case study analysis and is well-suited to the research aims. Mayu can be considered an ‘extreme case,’ i.e. a case of particular interest where the process of interest is transparently observable (Pettigrew, Citation1990). Indeed, Mayu has a considerably longer trajectory in terms of actual operation than the rest of the RMIOs operating in Peru (seven companies, up to July 2021, according to the Peruvian RMIO Registry, although only three of them are operating) (OSIPTEL, Citation2021). While Mayu's ICT service has proven its viability even in the most disconnected and low-income areas, such as the Amazon rainforest (Prieto-Egido et al., Citation2020), its contribution to the SDGs has not yet been analyzed.

Mayu not only offers ICT services throughout Peru but also supports the deployment of telemedicine tools in health facilities in the Napo River basin, an isolated area of the Loreto Region. Consequently, in terms of geographical scope, the study adopts a double perspective. It focuses on the national level (Peru) when analyzing the impact of Mayu in terms of connectivity, but concentrates on a particular region (Napo River basin) when analyzing the impact in terms of health improvements. The health impact is not estimated in the other regions where Mayu offers connectivity because there is no evidence that it is being used to improve health services.

2.3. Collection of information

The study drew on various sources of information that allowed for data triangulation: interviews, analysis of sustainability reports, webpages website of the company, academic articles, and other relevant information provided by the organization. The information was collected between February 2019 and February 2020, according to the following steps:

Collection of secondary information. This stage was conducted before contacting the company and involved the collection of information available on the company's website, as well as other public information available about the case (news about the company and the OIMR model, academic articles, technical reports, and dissertations related to the case).

Contact the company and request additional information. In this phase, the company was contacted, and a formal request for further information was made. Particularly, the sustainability reports and KPIs used by the company regarding the three sustainability dimensions (economic, environmental and social) were requested.

Interviews with the CEO of the company. Finally, three semi-structured interviews were conducted with the company's CEO, Omar Tupayachi, in different moments of the research process. The interviews were aimed at clarifying the business model of the company (synthesized through a business canvas) as well as the different elements of the Theory of Change framework as described in Section 2.5. All interviews were recorded and transcribed.

2.4. Case study analysis

The information collected was systematically analyzed using content analysis techniques (Weber, Citation1990). A crucial step in content analysis is codifying the information into groups or categories depending on selected criteria (Saldaña, Citation2021). In this case, the codes were established ‘a priori’ from two analytical frameworks. On the one hand, to characterize Mayu's impact upon development as well as the incumbent mechanisms, the information was analyzed according to an adapted Theory of Change (ToC) framework. The ToC provides a generic framework for impact assessment of programmes, initiatives, and organizations, widely used in the development sector. To identify specific elements relevant to the digital-for-development context and feed the generic categories in the ToC, the information was also analyzed according to the paradigm proposed by Heeks (Heeks, Citation2020). Both frameworks are explained in subsequent sections.

2.5.1 Adapted theory of change framework

For the specific field of Information and Communication Technologies for Development (ICT4D), Heeks and Molla (Citation2009) set the basis for the Impact Assessment (IA) of projects while providing a detailed review of different frameworks and methodological proposals. However, none seemed comprehensive and generic enough for Li and Thomas (Citation2019), who nonetheless recognized the challenges associated with the concept of impacts in this field. To overcome the limitations identified in Heek and Molla's work, the latter authors propose using the Theory of Change (ToC) as an alternative approach. Following this recommendation, we grounded our analysis on the ToC approach proposed by Weiss (Citation1995).

The ToC is ‘an outcomes-based approach which applies critical thinking to the design, implementation, and evaluation of initiatives and programmes intended to support change in their contexts’ (Vogel, Citation2012). It provides a framework to deliver evidence on how an impact can be achieved through an initiative or organization, and other approaches like logic models support it. It is also recommended for complex interventions (Rogers, Citation2008). The main weaknesses of ToC are related to the oversimplification of reality, the omission of externalities, the consumption of time and resources, and the debate over who owns ToC (Sullivan & Stewart, Citation2006) or subjectivity or context-specific analysis. Moreover, ‘it should be noted that the application of ToCs are based on a deeper assumption of development and therefore do not replace the critical understanding of development perspectives’ (Zheng et al., Citation2018, p. 6).

The adoption of a ToC has demonstrated to help promote the organizational capacity and programme sustainability of humanitarian non-profit-organizations (Hunter, Citation2006). Nonetheless, there are limited references on how this fits other types of organizations, such as ICT companies like Mayu. Thus the application of the ToC to a company is an innovative approach that makes it possible to gather evidence on its performance and impacts.

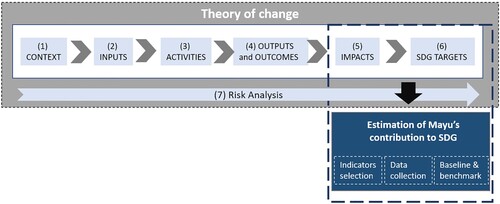

The proposed strategy for assessing how an ICT organization can impact the SDGs is shown in . It is based on seven basic categories, aligned with those proposed by Kivunike et al. (Citation2014): (1) Context, (2) Inputs, (3) Activities, (4) Outputs and Outcomes, (5) Impacts, (6) SDG targets, and (7) Risk analysis. The ‘SDG targets’ category reflects the causal chain of impacts linked to the final objectives intended to be achieved by organizations that seek to be sustainable. Thus it is a tool to conceptualize ‘development impacts.’ Kivunike et al. (Citation2014) proposed this link with the previous Millennium Development Goals (MDG), while Li and Thomas (Citation2019) claim that ‘For the ICT4D project to reach a broader impact in the developing world, it should suit and align with the SDGs’ (p. 99). Moreover, Tjoa and Tjoa (Citation2016) advocate for all ICT projects and organizations to include and monitor the effects of their work on the SDGs. However, as explained in Section 4.3, the SDGs also present limitations and have been the object of various criticisms, especially regarding the principle of ‘Leaving no one behind.’

Figure 1. Proposed methodology: adapted Theory of Change. Source: prepared by the authors, adapted from Kivunike et al., Citation2014.

These seven elementary categories were defined and can be complemented or fed using different tools from other fields, such as business management (e.g. business canvas) or those of ICT4D in particular (e.g. context analysis, mapping of actors, prioritization of SDGs). For this reason, a multidisciplinary approach is necessary. In the following paragraphs, we explain how we approached each category of analysis.

The context analysis (1) sought to identify key categories and sources of data to understand better the characteristics of the context in which Mayu operates. This was important because, besides the general acceptance that ICT improves peoples’ lives, some criticisms also exist regarding negative impacts detected (Rothe, Citation2020). Moreover, it has been recognized that relationships between ICT interventions and socioeconomic development need to be explored in-depth (Bailey & Osei-Bryson, Citation2018). Sometimes the validity and effectiveness of this relationship are not clear (Pandey & Gupta, Citation2018), and counterproductive effects have also been registered, such as maintaining or even amplifying pre-existing inequalities (Cinnamon, Citation2020). Thus contextualizing stands up as a fundamental step to frame the overall assessment and ensure an adequate focus of the analysis.

The analysis of the Inputs (2), Activities (3), and Outputs and Outcomes (4) were mainly based on the Heeks’ paradigm applied to Mayu's case. In particular, the business model block has been analyzed using an adaptation of Osterwalder and Pigneur's (Citation2010) popular Business Model Canvas.

Once Impacts (5) are defined as ultimate outcomes to be achieved by the organization, SDG prioritization is a common procedure to start analyzing relationships among SDG and organizations impacts (Weitz et al., Citation2018). It allows focusing on the SDGs to which greater contributions are made. We used a 0–2 scale to assess each target within each SDG, where value ‘2’ corresponded to a direct and significant relationship of the organization's value proposition with the target, value ‘1’ was selected for those targets with an indirect or partial relationship, and value ‘0’ was assigned to those targets with an irrelevant or null relationship. The association was established taking into account the business model canvas developed as well as the context analysis. To ensure objectivity and reliability, each author assessed all the targets independently and reached a consensus when disagreements appeared. Targets valued as having a significant and direct relationship were classified as priority and used to feed the ToC scheme, linking them with the impacts, as previously identified and added to the causal effect chain, thus establishing a concrete relationship between impacts and the SDG targets (6).

The final step was to discuss possible Risks (7) that would prevent Mayu from achieving the estimated impacts, and some negative impacts Mayu's activity could produce.

When estimating Mayu's contribution to the SDGs, a critical step was identifying and selecting key indicators to measure the impacts. As stated by Kivunike et al. (Citation2014), evaluation becomes more complex when moving from outputs to impacts as the focus shifts from technology to development. A combination of internal organizational data and contextual and sectoral indicators were used to establish proxy indicators (Kostoska & Kocarev, Citation2019). Available data to determine the baseline as well as a benchmark to interpret the results were collected when available. When information in this regard was missing, the indicator could not be included in the analysis, which implied discarding some of the previously prioritized goals.

Two additional considerations should be noted. First, we understand impacts in a general sense, as the medium and long term of the organization's performance regarding its activities and services. Second, we propose using the ToC as the backbone of the analysis process and as a tool to guide a ‘deep critical-reflection process’ (Li & Thomas, Citation2019) to analyze Mayu's contribution to development. ToC development was guided by the researchers who involved Mayu's personnel in a reflection and feedback process to deliver such theory, which was then drawn in a schematic figure and validated by Mayu's team. In this sense, we focus on the learning process involved in making ToC explicit, rather than checking its underlying theory.

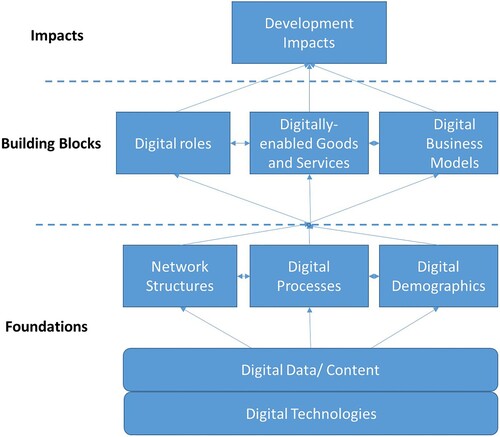

2.5.2 Digital-for-development paradigm

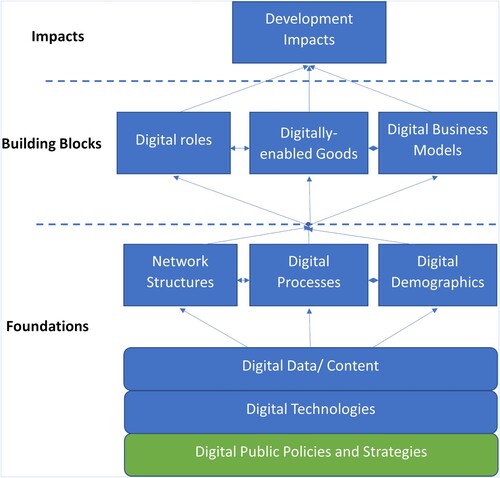

The elements of Heek's digital-for-development paradigm are shown in . ‘Building blocks’ are those components that relate to the operationalization of digital systems, i.e. a direct link to the impact of those systems on development (Heeks, Citation2020).

Figure 2. Components of the digital for-development paradigm from Heeks’ paradigm (Heeks, Citation2020). Source: prepared by the authors.

Regarding ‘foundations,’ new digital technologies allow the digitalization of data and processes, representing potential gains in increased access and efficiency. At the same time, technology changes have had significant impacts on the demographics of ICT usage regarding dimensions such as geography (more and more users are now coming from countries from the South) or experience (increasing presence yet decreasing the visibility of the digital). New digital technologies have also had an impact on the formation and characteristics of physical network structures in terms of their complexity, degree of virtualization or platformization.

In terms of building blocks, as citizens in developing countries interact with digital technology, they take on a range of different roles, which can be understood as a ‘role ladder’ (Heeks, Citation2017), whose different steps represent increasing levels of engagement with digital technology, from ‘delinked’ to ‘innovator.’ Then, digital technologies allow the creation of new goods and services or their conversion from a physical good or service to a virtual one, such as the provision of digitally-enabled telemedicine or educational services. Finally, new digital technologies enable the development of new business models in different domains: content collection, selection, compilation, distribution and/or presentation of online content; initiation, negotiation and/or fulfillment of online transactions; aggregation or sorting of online content; and provision or physical or virtual network infrastructure.

3. Results

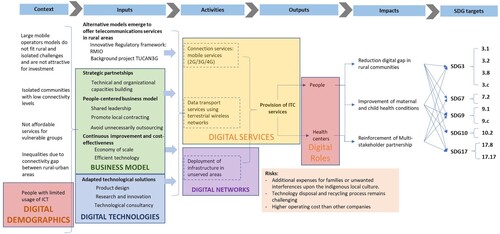

summarizes the ToC developed for Mayu, indicating the relationship to the blocks defined in Heeks’ paradigm. The main elements of the context, inputs and activities, as well as outputs, outcomes, and impacts delivered from Mayu's activity are highlighted about their contribution to the SDG targets.

Figure 3. Development of Mayu's Theory of Change combined with Heeks’ paradigm. Source: prepared by the authors.

3.1. Context analysis

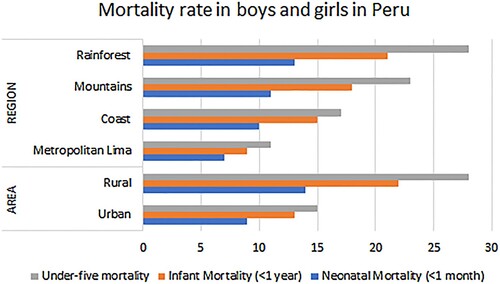

The high Human Development Index (HDI) rank for Peru – position 82 out of 189 in 2018 (UNDP, Citation2019) – hides substantial inequalities between urban and rural areas, and particularly between the country's three major geographical regions: the coast, the highlands, and the rainforest. The rainforest population concentrates the country's highest poverty rates and suffers from a severe shortage of resources, poor housing conditions, limited access to essential services, and social exclusion. Two critical indicators reflecting human development are infant and maternal mortality, which depend on access to quality health services. In terms of child mortality, the Peruvian rainforest stands as the most vulnerable region, where boys and girls are more likely to die than elsewhere (INEI, Citation2018). presents the mortality rate among children per 1000 births in Peru, where the average figure for those under 5 years of age was 28 in rural areas and 15 in urban areas.

Figure 4. Child mortality rate per 1000 live births in Peru between 2017 and 2018. Source: Prepared by the authors based on data from INEI (Citation2018).

In terms of maternal health, there is a wide margin for improving health services covering Peruvian rural areas. In 2018, prenatal care provided to pregnant women by medical staff was 15.9% in rural areas, compared to 45.7% in urban settings. Only 15.5% of pregnant women in the rainforest saw a specialist, compared to 58.5% in Lima, 44.2% at the coast, and 24.9% in the highlands. This impacts maternal mortality, which still shows substantial inequalities by residence and education level, especially among women who live in the rainforest and rural areas. In 2017, the country's maternal mortality ratio (MMR) was 69.8 women who died for every 100,000 live births, below the target of 70 established by the SDGs. However, this national average hides serious gaps affecting eminently rural administrative regions such as Huancavelica or Puno, which maintain high MMR figures of 132 and 121, respectively (MINSA, Citation2018).

According to the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO, Citation2012):

Compared to urban residents, rural people have to travel greater distances to reach local healthcare facilities. In addition to requiring adequate and affordable transportation between their community and the health centre, rural residents have to bear a greater burden in terms of time spent on health. On the other hand, they must negotiate and pay for transportation, and allocate time from their work to travel to the doctor's office, which could translate into lost wages or crops.

Concerning digital demographics, the 2017 HDI Report carried out by UNDP with a regional focus indicates that, in 2016, 55.5% of the country's population used the internet, with 116.2 mobile phone subscriptions per 100 people. However, the differences between Lima and the highlands or rainforest areas show the digital divide, with a precarious or non-existent service in rural communities. 13.9% of households throughout the country remain without ICT access, with some regions reaching 30%, such as Huancavelica, Amazonas, and Loreto. Specifically, there are 62,826 settlements in Peru without coverage (62,616 of them being rural), representing 63.1% of all settlements in the country (only 36.9% have mobile coverage). The region of Loreto, located in the Amazon rainforest, has the lowest mobile phone coverage in all of Peru, with only 64.4% of households having access to a mobile phone – despite the country's average reaching 83.8% in 2017.

Loreto is precisely one of the regions where Mayu has deployed its services. In particular, Mayu works in the Napo River basin, a paradigm of the deprivation of isolated rural areas. The Napo River is a tributary of the Amazon that runs through Peru and Ecuador's sparsely populated territories. It is an area accessible only by river and located an average of 10 h from Iquitos, the region's capital. Agricultural activity is the primary source of income for the Napo basin, but it is insufficient to cover its population's basic needs. Isolation conditions the lives of rural indigenous communities, who must make long and expensive trips by the river to Iquitos to carry out administrative procedures or access job opportunities, secondary studies, or specialized medical care. In this context of isolation, telecommunication services can be especially beneficial, although it is also more challenging to deploy and operate them. For this reason, the Napo experience provides an interesting case to study whether the RMIO strategy can contribute to reducing the connectivity gap within Peru and to reaching the SDGs. It serves to provide some insights into Mayu's model, which is analyzed in the following section.

3.2. Inputs, activities, and outputs

This section analyzes the case of Mayu using Heeks’ paradigm, trying to identify which are critical blocks for the RMIO strategy to develop the ToC as shown in .

First, Mayu chooses Digital Technologies with specific characteristics for rural areas: low maintenance, low energy consumption, and easy deployment. For the transport segment, Mayu prefers WiFi-based long-distance networks because they offer the lowest cost in sparsely populated and low-density settings. Technologies based on small or microsatellites are not yet cost-effective for data services (3G/4G), although they are helpful for voice services (2G). For the access network, Mayu deploys local-scale cellular networks. To maintain control of its base stations and reduce its dependence on the MNO, Mayu uses OpenRAN-based technologies (Singh et al., Citation2020). Stand-alone photovoltaic systems typically power all the equipment in both segments.

In terms of Digital Demographics, Mayu focuses on rural communities with no previous access to mobile services or the internet. The community used to share a fixed phone service through a satellite link, but it was entirely displaced by the advent of mobile services and is no longer available. On the other hand, public personnel (health, education, etc.) working in these communities come in many cases from other areas or have studied abroad, and they have become accustomed to using cell phones and the internet. In addition, public institutions have been digitizing their working processes (Digital Processes) for years and currently have platforms for information management and exchange: epidemiological surveillance systems, telemedicine tools, etc. Public facilities in isolated communities do not usually have access to these platforms, but the responsible public administrations demand to connect them.

To deploy networks in areas without coverage, Mayu takes advantage of some existing Network Structures in urban areas and deploys the ones it needs in rural areas. Mayu establishes agreements with MNOs to interconnect their networks so that Mayu can take advantage of some of the equipment that the MNO has deployed in its core network. Mayu then deploys the necessary infrastructure to serve rural areas using standard network elements similar to those of MNOs.

Mayu provides the physical infrastructure to mobile operators in underserved rural communities, similar to one of the examples Heeks uses when explaining his Digital Business Model block. Despite the high costs of providing mobile communication services in isolated areas, Peruvian regulation states that end-users should access the same rates and services as users in urban areas (Napurí, Citation2012). Apart from the innovative regulatory RMIO framework, several elements are essential to Mayu's business model:

Mayu does not sell services to end users but extends the coverage of an MNO and expands the MNO's customer base. This aspect allows Mayu to specialize in a specific sector and a narrower range of services than MNOs. For example, Mayu does not need to deploy a help desk or end-user billing services.

Mayu manages the complete process of deployment and operation, adopting a holistic and people-centred approach, and optimizing the process's overall costs. This approach entails fostering shared leadership, identifying the tasks that can be performed more efficiently internally, avoiding unnecessary outsourcing costs, and hiring more cost-effective services (e.g., transporting materials) locally.

The RMIO regulation encourages agreements between the Mayu and the MNO, allowing the former to use the frequencies of the latter, which saves Mayu a heavy investment in cellular frequencies.

Mayu prioritizes using robust equipment that limits maintenance and repair activities (OPEX) even if they have a slightly higher investment cost (CAPEX).

Mayu establishes partnerships with innovative technology companies through which, in exchange for beta-testing and validation of their products in different scenarios, Mayu is granted access to emerging technologies at a minimum cost.

Mayu also enters into partnerships with other RMIOs to exchange bandwidth. Where Mayu has a transport network, it sells bandwidth to other RMIOs so that they can deploy telephony services in specific communities. And when Mayu needs transport from other RMIOs, it contracts bandwidth from them. According to Mayu's CEO, the presence of other operators is not a threat to Mayu because the market is extensive.

However, Mayu's expansion potential is limited by its capacity to invest in telecommunications infrastructure. Certain elements such as telecommunications towers involve high CAPEX and have relatively long payback periods (10 years or more).

Using the network deployed and operated by Mayu, MNOs offer voice and data services to the population. On top of these services, other local players can start offering additional Digitally-Enabled goods and services. For example, local transportation companies can send their tickets via the Internet or telephone calls, making it easier for community residents to book their tickets and secure their transportation. Some local businesses are also starting to sell phone credit through their cell phones so that people who run out of credit do not have to travel to the city. Therefore, the connectivity offered by Mayu is changing the Digital Roles and allowing the population to become what Heeks calls Passive Consumers. Indeed, some of them already had smartphones that they used when they went to the city but kept disconnected in their community.

Furthermore, Mayu has established strategic partnerships with various actors. For example, Mayu participates in a consortium led by the Hispanic American Health Link Foundation and the Pontifical Catholic University of Peru (EHAS and PUCP are their respective Spanish acronyms). The consortium aims to provide mobile telephony and telemedicine services (Digitally-Enabled Goods and Services) in the Napo River basin. In this case, Mayu enables 3G/4G services in 14 communities through a wireless transport network that leverages the use of the telecommunications towers (Network Structures) that the Regional Government of Loreto owns in the Napo basin. Thanks to this partnership, Mayu reduces deployment costs and makes the service financially sustainable by not investing in towers and, in return, shares the bandwidth with the Regional Government. Moreover, EHAS and PUCP use this bandwidth to meet their research and development objectives by providing eHealth tools to health centres in the basin. The eHealth services deployed are recognized in the Peruvian Ministry of Health regulations but could not be implemented previously due to lack of connectivity. These eHealth tools include:

A teleconsultation platform that enables videoconferencing and allows primary health centers to seek advice from specialists at the regional hospital.

Teleconferencing systems to improve risk detection in pregnancy and reduce maternal mortality.

Tele-stethoscopy systems to improve the diagnosis of acute respiratory infections in children and reduce infant mortality.

In addition, connectivity allows health facilities to access health information systems and training courses provided by the Ministry of Health.

In summary, the Heeks blocks we have just identified are mainly related to the ‘Inputs, Activities, and Outputs’ blocks in the ToC. As shown in , starting from a context where there are no ICT services, Mayu's business model uses certain technologies to deploy networks that offer transport services and allow extending the connectivity service of large operators. These services allow ICT users to emerge in previously disconnected communities and take on new digital roles. The impact of these changes can be assessed through the SDGs, as explained in the following section.

In contrast, various environmental and social costs can be associated with Mayu's strategy. In the first place, access to telecommunication services can generate undesirable effects, such as additional expenses for families or unwanted interferences upon the local indigenous culture (Unwin & Unwin, Citation2017). Second, telecommunication infrastructure and equipment can cause environmental damage if not disposed of and recycled appropriately. A more detailed analysis of possible risks is presented in Section 3.5.

3.3. Impacts and SDG target prioritization

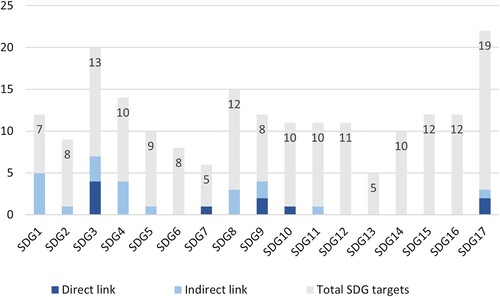

Telecommunication services have applications in almost all areas of human intervention and, therefore, could be related to most of the SDGs. Indeed, Mayu has an impact over 65% of goals (11 out of 17 SDGs) and 18% of targets (31 out of 169 targets) (see ). Among them, Mayu has a direct impact on 10 targets corresponding to five SDGs (3, 7, 9, 10, and 17), while it has an indirect impact on 21 targets distributed among all SDGs. However, it is worth stressing Mayu's contribution to three SDGs in particular, namely SDG 9, 3, and 17.

First, it impacts SDG 9, ‘Industry, innovation, and infrastructure,’ through its contribution to improving access to mobile broadband connectivity (Target 9.c) in isolated communities of Peru, such as the Napo River. This is achieved primarily through the development of ICT infrastructures (Target 9.1), but also by investing in innovation (Target 9.5) and collaborating to develop an adequate regulatory framework at the national level (Target 9.b).

Second, it impacts SDG 3, ‘Health and well-being,’ particularly by improving maternal and child health conditions in the Napo River basin (Targets 3.1 and 3.2). This is achieved through partnerships established to implement telemedicine services that improve the provision of health services (Targets 3.8 and 3.b).

Third, multistakeholder partnerships, such as those mentioned above, play an important role in Mayu's intervention model, linking it to SDG 17, ‘Partnerships to achieve the goals.’ Thus the company also has a direct impact on encouraging effective public-private and civil society partnerships (Target 17.17). In addition, it can contribute directly to some SDG 17 targets regarding internet access and communications (e.g. Target 17.8).

Additionally, contributions are made to other SDGs to a limited extent as impacts contribute to a single target of two SDGs in particular. On the one hand, SDG 7, ‘Affordable and clean energy,’ because of Mayu's contribution to renewable energy production (Target 7.2). On the other hand, ICT development has a clear impact on reducing inequalities, which is linked to SDG 10, ‘Reduced inequalities,’ particularly in terms of access to essential services, the protection of vulnerable groups, and the promotion of social and economic inclusion (Target 10.2).

Complementarily, Mayu affects other goals, although in less significant and more indirect ways. In the first place, it has an impact on SDG 1, ‘End of poverty,’ since the improvement in connectivity conditions can have an impact on the improvement of living conditions and income levels (Target 1.5), as explained in the Introduction. Also indirectly affected is SDG 4, ‘Quality education,’ by means of the contribution that better connectivity could have on improving the population's technical and professional skills (Targets 4.1 and 4.2). It can also contribute to SDG 11, ‘Sustainable cities,’ by improving connectivity between rural and urban centres, thus contributing to establishing positive economic, social, and environmental links between them (Target 11.a). Finally, Mayu's model can also be related to SDG 2, ‘Zero hunger,’ and SDG 8, ‘Economic growth,’ through the improvements in productivity that ICT can generate in the framework of the so-called Fourth Industrial Revolution or Industry 4.0.

Finally, an indirect contribution to SDG 5 is promoted through the potential increase in the proportion of women with access to telecommunication services that Mayu's activity entails (Target 5.b), as well as through the improvement of women's healthcare as a result of applying ICT to healthcare.

Taking into account all the relationships established with the SDGs, summarizes the links found between Mayu's impacts, as identified through the ToC method, and the specific SDG targets to which they contribute.

3.4. Estimation of Mayus's contribution to the SDGs

The most significant impacts affecting the SDGs were estimated and characterized in detail when enough data were available, as summarized in . The respective calculations are explained in the following sections.

Table 1. Estimation of Mayu's most significant contributions to the SDGs. Source: Prepared by the authors (* ‘Isolated regions’ are those that previously did not have access to telecommunications services).

3.4.1. Contribution to SDG 9: industry, innovation and infrastructure

There is a significant direct impact between Mayu's value proposition and Target 9.c, ‘Significantly increase access to information and communications technology and strive to provide universal and affordable access to the Internet in least developed countries by 2020.’ Indeed, Mayu is managing to provide mobile services (2G/3G/4G) to communities that until now were not of interest to large operators because they offer very low or even negative returns in traditional business models. So far, 78,000 people have gained access to mobile connectivity thanks to Mayu. These people live in 237 isolated communities in different regions of Peru: Pucallpa, Ucayali, Puno, Junín, Cajamarca, Amazonas, Loreto, and Piura.

This contribution is significant when taking into account Mayu's investment capacity and the lack of alternatives for these communities. However, the contribution is low regarding the total size of the country's underserved population. More than 62,000 isolated communities are still without mobile connectivity (around 6 million people).

3.4.2 Contribution to SDG 3: good health and well-being

According to the Peruvian Ministry of Health (MINSA), there are 1003 facilities equipped with telemedicine in Peru. However, most of them are health centres that already have a general practitioner and use telemedicine to access specialists located in urban hospitals. Rural health facilities, managed by nursing assistants and with fewer resources, don't usually have access to telemedicine and must serve their population without the support of general practitioners or specialists. According to the National Broadband Plan, 100% of educational centres, health facilities, police stations, and other administrative buildings located in urban areas should have broadband connections, at a minimum speed of 2 Mbps, by 2021. However, there remain more than 10,000 health facilities in the country that do not have access to telemedicine services and are not covered by the objectives of the MINSA (Government of Peru, Citation2011).

With its partners EHAS and PUCP, Mayu provides connectivity to all 14 health facilities in the Napo River basin. Through telemedicine systems, personnel with basic healthcare training working in the communities can communicate with general practitioners hours away from the community at health centres. This enables less-qualified personnel to ask questions, receive remote training, send epidemiological information, coordinate transfers, and manage medical shipments. Overall, the system improves primary care and increases trust in the national public health system. In the whole Loreto Region there are 371 health facilities, of which 70 belong to the Province of Maynas, where the Napo River is located.

The telemedicine tools available within the Napo River basin focus on improving maternal and child health by providing tele-ultrasound and tele-stethoscope solutions. Tele-ultrasound makes it possible to identify health risks during pregnancy and transfer high-risk pregnant women to the hospital before delivery, thus avoiding emergency deliveries within the communities. This tool is relevant in Loreto, a region with a Maternal Mortality Ratio of 91 deaths per 100,000 live births in 2017 (INEI, Citation2018). Meanwhile, tele-stethoscopy helps detect acute respiratory infections that are one of the leading causes of infant mortality. In Loreto, the mortality of children under 5 years of age is 28 per 1000 live births (INEI, Citation2018). Reliably measuring the impact of this alliance's activities on maternal and child health is not easy due to the difficulty of obtaining reliable records in rural areas, particularly in the Napo River basin. However, available studies estimate that better connectivity translates into a decrease in maternal mortality of up to 17% and a reduction in infant mortality of 22% compared to areas without cell phones (Martínez-Fernández et al., Citation2015). These studies have been carried out in rural areas of Guatemala, where the healthcare structure is similar to the Peruvian one. It is thus assumed that the benefits of telemedicine in both settings could be similar. In that case, the maternal mortality ratio in the Napo River could be reduced to 76, and infant mortality to 22, approaching the SDG targets of 70 and 12, respectively. With these figures, we can infer that Mayu's initiative directly impacts Targets 3.1 and 3.2 of maternal and infant mortality, respectively.

3.4.3 Contribution to SDG 17: partnerships for the goals

Thanks to the multistakeholder partnerships established, Mayu is managing to offer mobile services to communities that until now were not of interest to large operators, and it is taking advantage of this connectivity to improve the healthcare system.

Mayu has an agreement to collaborate with at least seven organizations in three different activity areas: connectivity, telemedicine, and rural deployments. It collaborates with the EHAS Foundation (ongoing for the last 3 years) and the PANGO Civil Association (last 2 years) in telemedicine projects (last 3 years); with Telefónica (last 4 years), Facebook (3 years), and Hispasat (3 years) in connectivity projects; and with the Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú (last 3 years) and the Regional Government of Loreto (last 3 years) in rural deployments. This partnership is now being extended to expand the Napo network on the Ecuadorian side of the river, where there is a hospital that serves people from both sides of the border. The Binational Development Plan for the Peru-Ecuador Border Region is funding the expansion of the network, and the Ministries of Health of both countries are establishing protocols for coordinating care and medical emergencies on both sides of the border through the Napo network. Moreover, new initiatives are arising, profiting from the pre-existing relationships established within the Napo context. Specifically, EHAS and PUC are now promoting a multistakeholder platform (PUCP, Citation2019) that intends to strengthen public services on the Santiago River (Condorcanqui Province, Amazonas Region) through ICT. Based on Napo's experience, they aim to improve primary health services and strengthen education and governance.

Therefore, it can be argued that it contributes directly to target 17.17, ‘Encourage and promote effective public, public–private, and civil society partnerships, building on the experience and resourcing strategies of partnerships.’

The consortium around Mayu has expanded its capacity for action and, thanks to this, rural communities have access to communication services and telemedicine services. In addition, Mayu has had access to additional funding and its network of suppliers has expanded, enabling it to access technologies better fit for its purpose.

3.5. Risk analysis

As mentioned before, some studies have identified potential risks associated with ICT expansion, see Section 3.2, last paragraph. This section identifies the most relevant risks associated with Mayu's activity and their possible impact on the SDGs. ICT is a tool used in a transversal way in multiple areas, and it can affect numerous SDG targets, as indicated in . Notwithstanding, the following paragraphs focus on the risks associated with the major SDG impacts analyzed in the previous section.

Regarding SDG 9, the first risk is the possibility that Mayu could stop providing its services, leaving the communities without telecommunication services again. This risk could materialize if regulatory changes modify the relationship with the large mobile operators who own the frequency licenses. However, the regulator is interested in maintaining and expanding the service in rural communities, so it is unlikely that the regulation will change to the detriment of Mayu. Another risk lies in possible price fluctuations for the technologies used. Mayu resorts to lower-cost innovative technologies that make its services profitable even in small rural communities. Nevertheless, the business models associated with these products are still under development (costs, contracting conditions, additional services, etc.). Consequently, future changes in these business models could increase equipment costs, although this is unlikely due to the sector's intense competition.

The impact that Mayu's services have on improving primary healthcare (SDG 3) depends, among other factors, on the capacity of staff to effectively use eHealth technologies (Shuvo et al., Citation2015). For this reason, the rotation of healthcare personnel in rural areas represents a risk for the sustainability of telemedicine in the medium term. The current support of the MINSA, which has an ongoing eHealth programme and wants to expand telemedicine services to rural health posts, mitigates this risk. Another issue is that finding reliable health records in rural areas is complex, leading to a substantial risk of not adequately measuring the resulting health impacts or not being able to attribute them to Mayu and its partners’ intervention directly. In this regard, analyzing the extent to which Mayu contributes to health impacts remains a challenge. Additionally, another risk is derived from the fact that improving healthcare is not only a result of Mayu's activity. Still, it stems from a joint effort of the members of the consortium it belongs to. This risk is limited because Mayu's partners, specifically the EHAS Foundation and PUCP, have been working on eHealth projects for many years and have been active for more than 10 years in the communities where telemedicine services are operational. Thus if strategic partnerships are maintained, the risk can be minimized to a great extent.

Concerning SDG 17, Mayu's alliances offer new business opportunities and increase Mayu's impact. However, they carry a risk since certain actors can generate dependencies. Diversifying alliances helps Mayu limit a single actor's chance to condition its future. It is also essential to mitigate this risk through good coordination within the consortium because each institution has different business objectives. In this vein, it is also necessary to monitor the risk of activities not complying with the initial plan, which increases in proportion to the number of institutions involved.

The deployment of ICT in rural areas can also have adverse effects associated with the extra spending for families (Rey-Moreno et al., Citation2016), the alteration of local culture (Piccolo & Pereira, Citation2019), or a negative impact on gender equality (Bhandari, Citation2019). In addition, improper handling of replaced equipment can generate environmental damage (Pont et al., Citation2019). Rothe (Citation2020) has proposed a good framework to study these aspects, but such an analysis is beyond the scope of this paper.

4. Discussion

4.1 Theoretical implications

This article adopts a case study approach to explore how Mayu's strategy for extending coverage in rural and isolated areas without access to ICT services can contribute to development by estimating its contribution to the SDGs. Using a ToC framework together with Heeks’ paradigm allows us to identify and understand some critical aspects of the case and draw conclusions that contribute to the ICT4D theory.

A first consideration is that Heeks's framework is useful to approach ICT and development understanding for a particular case study as it provides a comprehensive set of elements and categories of analysis. However, it lacks a clear explanation of how they deliver specific development impacts, as claimed by other authors (Sein et al., Citation2019). Therefore, Heeks’ paradigm may be complemented with alternative approaches that facilitate a better understanding of such interlinkages and the processes involved. To this regard, the ToC framework is a suitable approach to fill this gap because it allows operationalizing Heeks’ categories and linking them to concrete impacts.

Second, it should be noted that despite the importance of the context and particularly the public policy in ICT in place (Harris, Citation2016), Heeks’ paradigm does not explicitly mention this aspect. Thus we propose adding a cross-cutting block in the foundation components to include ‘Digital Public Policies and Strategies’ as an additional element of the context that influences Digital Technologies, Digital Processes, Network Structures, Digital Business Models, and Digital-Enabled Goods and Services. This new block is represented in green in and makes the paradigm more comprehensive and complete.

Figure 7. Components of the digital for-development paradigm adapted from (Heeks, Citation2020). The blocks of the original paradigm are represented in blue, and the new proposed block is represented in green. Source: prepared by the authors.

4.2 Practical implications

Mayu was the first company established as an RMIO. Its experience has served to show the feasibility of an innovative model that other companies have later adopted, as there are currently seven companies registered as RMIOs in Peru (OSIPTEL, Citation2021). The strategy's relevance is highlighted by the recognition given to one of these companies, Internet for All, by the ‘2019 Project & Infrastructure Finance Awards’, granted by LatinFinance, which seeks to recognize the most important financial transactions and infrastructure projects in Latin America and the Caribbean. However, the analysis of this case reveals some limitations of the RMIO strategy and allows formulating several recommendations addressed to policy-makers that could be useful to strengthen it.

First, this case study shows that financial sustainability in rural environments is a significant challenge for both MNOs and RMIOs. RMIO specialization in rural settings and its holistic view in terms of cost-efficiency is vital for financial sustainability. However, infrastructure investment makes communities under 400 inhabitants not financially viable, and therefore additional measures would be necessary to serve those areas. Collaboration with community networks may be one strategy to achieve this goal. In addition, public support in developing civil infrastructures such as towers also contributes to bringing services to less profitable communities.

Second, Peruvian regulation obliges RMIOs to establish agreements with MNOs for network deployment and the use of cellular frequencies. These agreements require an unbalanced negotiation between a large company and a small operator. Consequently, only three RMIOs have managed to sign these contracts and two of them only with one MNO (Telefónica del Perú). Moreover, this requirement is not necessary from a technology or cost point of view, as the new OpenRAN solutions allow the RMIO to deploy its core network. The RMIO regulation contemplates that the regulator (OSIPTEL) can force an agreement between the MNO if the RMIO requests it, but this mechanism has not been used yet. By relying on contracts with the MNO, the RMIO is restricted in its ability to deploy networks wherever it sees fit and cannot intervene in the prices offered in rural communities, on which its revenues ultimately depend. To mitigate this limitation, access to frequencies could be more flexible in areas where MNOs are not using them. Without the obligation to reach agreements with the MNO, the RMIO could offer services with costs adapted to the context and collaborate more easily with local organizations such as community networks.

Finally, deploying connectivity services is a necessary but not sufficient condition to achieve a broad development impact. The characterization of the RMIO impact in terms of the SDGs shows that impact is extended to wider areas of the Agenda when an intentional strategy is applied to use connectivity to improve areas such as maternal and child health conditions (in this case, a multistakeholder partnership to implement telemedicine services). Together with an effective public policy aimed at improving connectivity, policy makers should develop coordinated agendas around areas such as health care or education, which could be particularly impacted by connectivity. Furthermore, partnerships such as those of the Napo project should be encouraged and supported.

4.3 Limitations and further research

The main limitation of this study is the scarcity of data to directly evaluate the impact of Mayu on the communities, which has limited the analysis of its contribution to specific SDG targets. A more thorough impact assessment would be of great interest. However, it will require extensive fieldwork to collect data, and it would not be feasible in terms of the time and resources necessary to cover all rural communities where a telecommunications operator offers service. For this reason, this study has combined data from Mayu's interventions with contextual and sectoral information to develop indirect indicators to estimate impacts (proxy indicators). Although it is an estimate, this methodology shows a way to analyze the effects of ICTs on the SDGs, and it is noteworthy that it does so at the target level, making it an innovative proposal in this field. In addition, the methodology is flexible enough to integrate the undesirable effects of the technologies, taking into account the associated risks. However, this analysis should be addressed in greater depth by future studies.

Then, this study has used the SDGs as a framework for operationalizing development impacts. While conceptualizing impacts in terms of SDG targets helps frame development impacts in a shared and mainstream sustainable development framework and is helpful for comparisons when analyzing ICT4D initiatives, it also has some limitations. SDGs have been said to mainly focus on technical aspects while lacking a holistic approach for socio-environmental issues (Wu et al., Citation2018). Then, as evidenced in the analysis of partnerships, the SDGs are often difficult to measure and monitor and do not provide elements to analyze progress on some targets, as is the case here with target 17.17 (Bali Swain & Yang-Wallentin, Citation2020; Stott & Scoppetta, Citation2020;). Furthermore, possible undesired effects of the SDGs are often neglected; for example, multistakeholder partnerships encouraged in target 17.17 may be counterproductive in specific contexts (Banerjee et al., Citation2020; Menashy, Citation2017). Moreover, the SDGs have been criticized for prioritizing economic growth over ecological integrity and not being sufficiently transformative (Eisenmenger et al., Citation2020; Swain, Citation2018) or inclusive (Brussel et al., Citation2019). Indeed, additional considerations should ensure ‘leaving no one behind’ when addressing the Agenda implementation. While the SDG agenda shows the ‘big picture,’ it does not include specific claims from particular collectives, for example, in terms of indigenous people (Yap & Watene, Citation2019) or unconventional gender identities (Mills, Citation2015). Furthermore, some authors analyze the shortcoming discourses on leaving no one behind approach (Weber, Citation2017; Winkler & Satterthwaite, Citation2017) or how the Agenda falls short of addressing inequalities (MacNaughton, Citation2017). This limitation of the SDGs can be solved in future works by adding indicators that depend on the evaluation context.

5. Conclusion

This paper analyzes the RMIO strategy and its impacts on development, estimating its contribution to several SDG targets. This analysis is based on an innovative methodology applied to the case study of Mayu Telecomunicaciones, the first operator created under the RMIO figure in Peru. Mayu's activity is found to affect only a few SDGs (SDGs 3, 9, and 17). However, connectivity opportunities could be extended to other areas such as education (SDG 4), agriculture (SDG 2), or governance (SDG 16). Indeed, ICTs are a cross-cutting tool that is expected to contribute to most of the global challenges of the SDGs, although estimating their impact in other areas will require the development of additional proxy indicators. The potential of ICTs is especially relevant in isolated communities with limited or no connectivity, which are targeted by RMIOs and where the SDGs are far from being met.

The proposed methodology is based on a combination of the Theory of Change and Heeks’ paradigm and has proved suitable for analyzing ICT4D initiatives. Heeks’ model helped identify key ICT components to impact development, while the ToC helped to better understand the relationship between those elements and development impact. As far as we know, this is the first work where the paradigm proposed by Heeks is applied to a case study, and it resulted in the identification of a theoretical contribution to enhance the paradigm: the inclusion of a new component, namely ‘Digital public policies and strategies,’ as a critical factor of the context to be taken into account. Furthermore, we believe that this methodology is transferable to other contexts and to other companies in the sector that wish to understand their contribution to the SDGs. In that sense, it can serve as a starting point for organizations to promote a transformative shift towards sustainability within their organizational and business models, and enhance comparability of the results in terms of SDGs and targets measured.

This work also exemplifies the importance of public policies being consistent with the SDGs: strengthening rural healthcare or education may require a coherent telecommunications policy. This aspect is critical because achieving sustainable development is not an isolated challenge for an institution or a sector but must be addressed by society as a whole. Furthermore, this case study stresses the role of public administration and regulation as a source and enabler of innovation. It shows that effective incentives can be established to develop new strategies that respond to global challenges in a sustainable way, particularly from a financial perspective. However, this work also shows some of the limitations of the RMIO strategy. Governments could consider these limitations to incorporate regulatory innovations that allow other actors different from MNOs to use mobile telephony frequencies where they are not being used. Finally, concerns about monitoring and measuring progress in SDG implementation and the need to overcome identified data gaps are highlighted.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the support of the Secretaría General Iberoamericana (SEGIB) in developing this study and Mayu's collaboration in understanding the RMIO strategy and its impacts.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Ignacio Prieto-Egido

Ignacio Prieto-Egido works as an associate professor at the Rey Juan Carlos University, where he is a member of the Information and Communication Technologies for Human Development (ICT4HD) group. His research is focused on designing, deploying, and evaluating innovative solutions to reduce maternal and infant mortality in rural areas of developing countries.

Teresa Sanchez-Chaparro

Teresa Sanchez-Chaparro works as a professor at Universidad Politécnica de Madrid (UPM). She is a member of the Innovation and Technology for Development Centre (itdUPM) and of the Sustainable Organizations research group within this same university. Her current research interests are sustainable organizations, SDGs, and quality assurance in higher education.

Julia Urquijo-Reguera

Julia Urquijo-Reguera works as an assistant professor at Universidad Politécnica de Madrid (UPM) and as an international consultant on sustainable development. Her research focuses on evaluation approaches and methodologies development for sustainable development analysis, as well as indicators development to measure advances and contribution on SDG from different organizations, contexts, and scales. She is especially interested in climate change adaptation and disaster risk reduction for sustainable agriculture and rural development.

References

- AfDB, ADB, EBRD & IDB. (2018). The Future of Work: Regional Perspectives. African Development Bank, Asian Development Bank, European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, Inter-American Development Bank. https://publications.iadb.org/es/el-futuro-del-trabajo-perspectivas-regionales

- Aristovnik, A. (2012). The impact of ICT on educational performance and its efficiency in selected EU and OECD countries: A non-parametric analysis. Turkish Online Journal of Educational Technology, 11(3), 144–152 https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2187482 .

- Baig, R., Freitag, F., & Navarro, L. (2018). Cloudy in guifi.net: Establishing and sustaining a community cloud as open commons. Future Generation Computer Systems, 87, 868–887. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.future.2017.12.017

- Bailey, A., & Osei-Bryson, K.-M. (2018). Contextual reflections on innovations in an interconnected world: Theoretical lenses and practical considerations in ICT4D. Information Technology for Development, 24(3), 423–428. https://doi.org/10.1080/02681102.2018.1499202

- Bali Swain, R., & Yang-Wallentin, F. (2020). Achieving sustainable development goals: Predicaments and strategies. International Journal of Sustainable Development & World Ecology, 27(2), 96–106. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504509.2019.1692316

- Banerjee, A., Murphy, E., & Walsh, P. P. (2020). Perceptions of multistakeholder partnerships for the sustainable development goals: A case study of Irish non-state actors. Sustainability, 12(21), 8872. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12218872

- Baro, E. E., & Endouware, B. E. C. (2013). The effects of mobile phone on the socioeconomic life of the rural dwellers in the Niger delta region of Nigeria. Information Technology for Development, 19(3), 249–263. https://doi.org/10.1080/02681102.2012.755895

- Bhavnani, A., Chiu, R. W. W., Janakiram, S., Silarszky, P., & Bhatia, D. (2008). The role of mobile phones in sustainable rural poverty reduction. Ict Policy Division.

- Brussel, M., Zuidgeest, M., Pfeffer, K., & van Maarseveen, M. (2019). Access or accessibility? A critique of the urban transport SDG indicator. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information, 8(2), 67.

- Bhandari, A. (2019). Gender inequality in mobile technology access: The role of economic and social development. Information, Communication & Society, 22(5), 678–694. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2018.1563206

- Cinnamon, J. (2020). Data inequalities and why they matter for development. Information Technology for Development, 26(2), 214–233. https://doi.org/10.1080/02681102.2019.1650244

- Corbett, J., & Mellouli, S. (2017). Winning the SDG battle in cities: How an integrated information ecosystem can contribute to the achievement of the 2030 sustainable development goals. Information Systems Journal, 27(4), 427–461. https://doi.org/10.1111/isj.12138

- COTEC. (2017). Iniciativas empresariales y políticas públicas para acelerar el desarrollo de un ecosistema digital iberoamericano. Fundación Cotec para la Innovación. Retrieved from: http://informecotec.es/media/inf_CIPC_vfinal.pdf

- Cruz, G., & Touchard, G. (2018). Enabling Rural Coverage. [Technical Report]. GSMA. https://www.gsma.com/mobilefordevelopment/resources/enabling-rural-coverage-report

- Diga, K., & May, J. (2016). The ICT ecosystem: The application, usefulness, and future of an evolving concept. Information Technology for Development, 22(sup1), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1080/02681102.2016.1168218

- Dutta, U. P., Gupta, H., & Sengupta, P. P. (2019). ICT and health outcome nexus in 30 selected Asian countries: Fresh evidence from panel data analysis. Technology in Society, 59, 101184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2019.101184

- ECLAC. (2006). Pueblos indígenas y afrodescendientes de América Latina y el Caribe: Información sociodemográfica para políticas y programas. United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean.

- ECLAC. (2012). Pobreza y desigualdad. Informe Latinoamericano 2011. United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean. Retrieved from: http://repositorio.minedu.gob.pe/handle/123456789/1175

- ECLAC. (2019). Informe de avance cuatrienal sobre el progreso y los desafíos regionales de la Agenda 2030 para el Desarrollo Sostenible en América Latina y el Caribe. United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean. Retrieved from: https://repositorio.cepal.org/handle/11362/44551

- Eisenhardt, K. M., & Graebner, M. E. (2007). Theory building from cases: Opportunities and challenges. Academy of Management Journal, 50(1), 25–32. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2007.24160888

- Eisenmenger, N., Pichler, M., Krenmayr, N., Noll, D., Plank, B., Schalmann, E., & Gingrich, S. (2020). The sustainable development goals prioritise economic growth over sustainable resource use: A critical reflection on the SDGs from a socio-ecological perspective. Sustainability Science, 15(4), 1101–1110. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-020-00813-x

- Gibson, T., & Van der Vaart, H. J. (2008). Defining SMEs: A less imperfect way of defining small and medium enterprises in developing countries.

- Government of Peru. (2011). National plan for the development of broadband in Peru. Developed from Supreme Resolution No. 063-2010-PCM6.

- Harris, R. W. (2016). How ICT4D research fails the poor. Information Technology for Development, 22, 177–192.

- Heeks, R. (2017). Information and communication technology for development (ICT4D. Routledge.

- Heeks, R. (2020). ICT4D 3.0? Part 1—The components of an emerging “digital-for-development” paradigm. The Electronic Journal of Information Systems in Developing Countries, 86(3), e12124. https://doi.org/10.1002/isd2.12124

- Heeks, R., & Molla, A. (2009). Compendium on impact assessment of ICT-for-development projects.

- Hossain, M., & Samad, H. (2020). Mobile phones, household welfare, and women's empowerment: Evidence from rural off-grid regions of Bangladesh. Information Technology for Development, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/02681102.2020.1818542

- Hunter, D. E. K. (2006). Using a theory of change approach to build organisational strength, capacity and sustainability with not-for-profit organisations in the human services sector. Evaluation and Program Planning, 29(2), 193–200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2005.10.003

- INEI. (2018). Perú—Encuesta Demográfica y de Salud Familiar 2018 [Encuesta Demográfica y de Salud]. Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática (Peru). https://webinei.inei.gob.pe/anda_inei/index.php/catalog/671

- Kivunike, F. N., Ekenberg, L., Danielson, M., & Tusubira, F. F. (2014). Towards a structured approach for evaluating the ICT contribution to development. International Journal on Advances in ICT for Emerging Regions (ICTer), 7(1), 1–15 https://doi.org/10.4038/icter.v7i1.7152.

- Kostoska, O., & Kocarev, L. (2019). A novel ICT framework for sustainable development goals. Sustainability, 11(7), 1961. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11071961

- Labonne, J., & Chase, R. S. (2009). The power of information: The impact of mobile phones on farmers’ welfare in the Philippines. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper, 4996, 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1596/1813-9450-4996.

- Li, Y., & Thomas, M. A. (2019). Adopting a theory of change approach for ICT4D project impact assessment—The case of CMES project. In P. Nielsen, & H. C. Kimaro (Eds.), Information and Communication Technologies for Development. Strengthening Southern-Driven Cooperation as a Catalyst for ICT4D (pp. 95–109). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-19115-3_9

- Lieberman, A. (1986). Collaborative research: Working with, not working on. Educational Leadership, 43(5), 28–32.

- MacNaughton, G. (2017). Vertical inequalities: are the SDGs and human rights up to the challenges? The International Journal of Human Rights, 21(8), 1050–1072. http://doi.org/10.1080/13642987.2017.1348697