ABSTRACT

Digital transformation goes beyond digitalization to make radical changes to organisational models and social structures. It takes people with knowledge, skills and motivation to use ICTs to be able to carry out digital transformation. Human capital is seen to be the key for effective digital transformation as it can fuel sustainable development when people use ICTs to lead the lives they choose to live. Unless there is a transformation in capabilities, access to ICTs, requisite skills and knowledge, then digital transformation will merely exacerbate existing inequalities. It will need to touch personal psychology: not merely enabling the marginalised to participate but offering them the ability use digitalization to improve their lives. The human capital key to digital transformation is offered as a means of attaining positive cycles of sustainable development. Lessons learned from papers in this issue throw insight into ways of applying digital technologies to overcome forces of oppression.

1. Introduction

Digital transformation is changing the way improvements are taking place in the lives of people, their communities and nations (Qureshi, Citation2022). Heeks et al. (Citation2022) define the term digital transformation, also referred to as DX4D as ‘radical change in development processes and structures enabled by digital systems’ P.1. Digital transformation at the margins takes place when the oppressed can use technologies to find their way out of the necropolitics that binds them (Qureshi, Citation2022). Necropolitics is the capacity to dictate who must live and who must die (Mbembé & Meintjes, Citation2003). In most cases, it is the oppressor that decides who must die and who gets to live thus limiting the sovereignty of those who are subjects of oppression. When acts of exploitation and violence take place from a failure to recognize others as persons, then self-determination for those who want to fight for their rights depends upon their access to the global internet using digital technologies. Yet, recent events have shown that the use of ICTs have exacerbated inequalities, threatened to prolong conflicts, and increased the populations of refugees or people living without necessities such as food, water and electricity or the ability to do so (Bock et al., Citation2020; Iazzolino, Citation2021; Martin & Taylor, Citation2021; Nemer, Citation2022; Qureshi, Citation2022; UNHCR, Citation2023). That is why digital transformation goes beyond digitalization to make radical changes to organizational models and social structures.

Digital transformation requires a transformation of capabilities including human capital; without this, there will not be a structural transformation of the type needed to eliminate oppression. Improvements in human capital are needed to achieve radical improvements in people’s lives from digitization. This is why investing in human capital to enable people to use ICTs in innovative ways by people whose homes, communities and towns are destroyed by airstrikes while they search for shelter food and water. Transformation of people’s lives out of the historical inequalities that keep them from accessing the economic and political resources of their societies requires access to the factors of production that offer economic opportunity. In this way, digital transformation has the potential to alter the lives of people as they try to make their way out of oppression, destruction, and homelessness in which they find themselves. Those living with limited access to basic resources needed for survival in refugee camps, favelas and communities with makeshift homes lack access to basic human rights (Bock et al., Citation2020; Iazzolino, Citation2021; Martin & Taylor, Citation2021; Nemer, Citation2022; UNHCR, Citation2023). Due to their circumstances, their human capital remains limited unless they can acquire new skills, knowledge and capabilities to help them out of their oppression.

Radical changes to organizational models and social structures take place when there are changes in the underlying technological infrastructure and human infrastructure of skills and knowledge, including digital literacy (Heeks et al., Citation2023). When their homes are destroyed, land and properties taken over, they are left destitute, stateless and without the basic protections of human rights law. As of 2022, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees estimated 4.4 million people worldwide as either stateless or of undetermined nationality (UNHCR, Citation2023). Often assisted by their active use of digital technologies, they find food, shelter and access economic opportunities that offer them the ability to sustain themselves. Their capabilities expand through their use of mobile phone applications that offer them access to the information and resources needed to survive. At the same time, their data is harvested and used to create digital products sold by corporations to governments (Zuboff, Citation2015). The use of such data by governments to track and monitor their citizens has brought about additional challenges to human rights. Can their data rights be human rights?

Human capital is seen to be the key for effective digital transformation to take place. The global economy needs human capital to grow and sustain itself. The World Bank (Citation2020) understands that measuring human capital is important. It starts with infant mortality in that children born today can expect to attain by their 18th birthdays, the Human Capital Index highlights how current health and education outcomes shape generations of people and underscores the importance of government and societal investments in human capital. It defines human capital as the knowledge, skills, and health that people accumulate over their lives and is a central driver of sustainable growth and poverty reduction. The Human Capital Index highlights how current health and education outcomes shape productivity of the next generation of workers and underscores the importance of government and societal investments in human capital (World Bank, Citation2020). Offering technical education is important so that people can be able to use ICTs to lead the lives they chose to live. In addition to this, investments are needed in health, nutrition and the aptitude for taking the economic opportunities and motivation to do so, enable sustainable development to be achieved.

The power unleased by the technologies for digital identities, the innovative uses by refugee populations, the data collected and analyzed to offer novel services with the help of artificial intelligence tools have brought attention to the concept of digital transformation. In recent years, there has been growing interest within information and communication technology for development (ICT4D) in digital transformation (ElMassah & Mohieldin, Citation2020; Qureshi, Citation2022). Guidance on digital transformation for ICT4D practitioners and others has, however, been in short supply with the temptation being to follow that provided by consulting company white papers that focus on large businesses in the global North using technologies built in contexts unsuited to the development context. This need is addressed here through the question being explored: can ICT4D design and development approaches deliver transformation that is both equitable and feasible?

1.1. Digital transformation for development

Digital transformation goes beyond digitalization to make radical changes to organizational models and social structures. There is evidence to suggest that the transformation of global processes and the production of goods and services through the application of digital media have changed business models and societal structures (Graham, Citation2019; Heeks et al., Citation2023; Malecki, Citation2002; Vial, Citation2019). The purpose of digital transformation in the context of development according to ElMassah and Mohieldin (Citation2020) is primarily for the adoption of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Established in 2015 to pursue a more sustainable path toward inclusive and equitable growth, which known as Agenda 2030, include 17 SDGs that cover a broad range of issues related to development and include 169 targets and 304 indicators. This form of data-driven governance, they suggest, enables digital transformation in localizing the implementation of the SDGs. They define digital transformation as ‘the profound transformation of business and organizational activities, processes, competencies and models to fully leverage the changes and opportunities of a mix of digital technologies and their accelerating impact across society in a strategic and prioritized way, with present and future shifts in mind’ (i-SCOOP.eu, 2016 in ElMassah & Mohieldin, Citation2020, p. 2).

The processes of digital transformation differ depending upon the development paradigms being followed. They are not mutually exclusive as a decolonialization paradigm may offer human and sustainable development outcomes. Heeks et al. (Citation2022) offer different outcomes for the neoliberal, structuralist, sustainable, human development and decolonialization paradigms. For example, the neoliberal paradigm focusses on privatization that may bring about digital transformation in the form of changes in markets that function through datafication and machine-readability of market actors and processes. A human development paradigm which focusses on equality of opportunity and choice may support transformations in the ability of all to choose the kind of lives and livelihoods that they value, thus requiring the customization of digital technologies to individual contexts. A decolonial perspective, which seeks to support sovereignty and self-determination of indigenous peoples, may offer digital sovereignty in the form of control over the creation and use of digital assets by the indigenous people preventing uncontrolled extraction of value from these assets by others (Heeks et al., Citation2022).

Within the decolonialization paradigm, digital transformation offers many challenges. Nemer (Citation2022) explains how laws, guidelines and rules are imposed by the consciousness of the prescriber (oppressor) on the consciousness of the prescribed (oppressed) and can be imposed by technological artifacts. Prescriptions imposed through laws and boundaries are designed into algorithms and technological affordances of digital technologies. These technologies are seen to encompass racial bias and algorithmic necropolitics he claims. Mbembé and Meintjes (Citation2003) describe the plight of vast populations living in what they refer to as ‘death-worlds’ where people would rather die than live their lives in servitude. Their use of mobile cell phones and digital identity systems have supported their survival while becoming tools of oppression (Bock et al., Citation2020; Iazzolino, Citation2021; Martin & Taylor, Citation2021; Masiero & Bailur, Citation2021; Schoemaker et al., Citation2021). Iazzolino (Citation2021) offers insight into the biopolitical technologies, such as biometrics, which highlight and heighten the tension between care and surveillance. This tension takes place when refugees challenge the official motives behind biometric infrastructures with situated counter-narratives. He argues that the biometric identification systems exacerbated pre-existing power relations by increasing that socio-economic exclusion, lack of access to employment and business opportunities for the Somali Bantu refugees.

The societal implication of digital transformation is Datafication which is the generation of large amounts of digital data that is machine-readable and computationally manipulable, particularly for ‘big data’ analytics (Taylor & Broeders, Citation2015; Masiero & Das, Citation2019; Heeks & Shekhar, Citation2019). This leads to a Datafied society where everyday forms of activism and re-existence, including their daily tweaking of the digital for purposes of community, care, and survival, takes place online. These online interactions offer insights about design and digital justice (Milan et al., Citation2021). Technologies of control used by government bureaucrats or corporate leaders are used to centralize power to the few at the helm. Digital transformation at the margins takes place when the oppressed can use digital technologies to find their way out of the necropolitics that binds them so that people can have control over their own lives, exercise their reason which is tantamount to the exercise of freedom, a key element for individual autonomy (Mbembé & Meintjes, Citation2003; Qureshi, Citation2022).

The concepts used to describe digital transformation are born from the global north where the exercise of human agency revolves around the dominant market mechanisms. Harvesting large amounts of data to scale and analyzing this data through machine learning models is surveillance capitalism. Much of the data harvested is used in Information capitalism which ‘aims to predict and modify human behavior as a means to produce revenue and market control’ (Zuboff, Citation2015). The following section explores the role of human capital in enabling digital transformation as a means out of oppression.

2. The human capital key

For digital transformation to take place human capital is needed. Human capital is seen to have a decisive influence on production through labor productivity (Pelinescu, Citation2015). It is the stock of skills that a labor force possesses. The flow of these skills is an indication of an individual’s productive capacity which increases with more skills especially when the return to investment exceeds the cost of obtaining these skills (Goldin, Citation2016). White (Citation2009) suggests that endogenous growth models have focussed on a country’s growth rate and its stock of human capital. Without human capital, physical capital, information technology and other factors of production may not function. Effective digital transformation requires investments in people and technology that enable equitable economic growth. White (Citation2009) argues that individuals with good motivation, health and attitudes which favor pursuing economic opportunities and aptitudes for problem-solving reinforce economic development. There is a positive cycle when through economic growth incomes increase, people can invest in education, lead healthier lifestyles, consume better nutrition and create longer term social relationships. Banerjee and Duflo (Citation2011) found that the economic gains from investments in education to increase human capital are higher in poor countries that in rich ones.

‘Economic development results from the acts of human beings. Destroy all physical capital, burn all relevant technical blueprints … ’ (White, Citation2009, p. 135) and human beings have a way of bouncing back. To bounce back, they do need help in the form of access to that which meets their basic needs often through their use of digital media. Accessing resources to meet basic needs through digital technology is a challenge when digital technology depends on infrastructure which can be destroyed or may otherwise non-existent. Human capital is needed to customise digital technologies to individual contexts so that individuals may use these technologies to access the resources they need to survive and thrive. When homes, towns and communities are destroyed, people share what resources they can muster to rebuild safer and better. Wars devastate the buildings they call home, hospitals, schools, shelters, modes of transportation and the livelihoods that sustain them. People become resilient. When the basic infrastructures for survival are destroyed, and necessities for survival (food, water and shelter) become hard to come by, the ecosystems that sustain livelihoods collapse. People survive in make-shift shelters with limited food and water. Human capital helps them use whatever limited resources they can find to stay alive, keep their families from starvation, and find shelter in the most unlikely places. Human capital becomes the key to their survival.

When people use ICTs to support their livelihoods, they may make their way out of oppression to live the lives they chose live. For example, the Masai herdsman can continue to live with his tribe in the bush and earn a living through being a herdsman for other people’s cattle. Digital transformation can take place when the capabilities people possess to use digital media in innovative ways to enable societal change. A young woman who has lost her home and livelihood due to bombardments from airstrikes can post recordings of her life in a make-shift refugee camp while the bomb blasts and screams can be heard in the background. Her use of digital technology may not alleviate the oppression that she and her family face, but it does transform the narrative of her suffering by allowing her followers to see in real time as events unfold. While she may not survive to achieve freedom from oppression, her videos documenting her suffering may transform access to economic opportunity for her people. While the technology is doing nothing to meet her basic needs, it does have an impact on the broader context. Aggressors cause blackouts or cut access to the Internet to limit the flow of information in or out of a conflict zone. Because information has an impact that is contrary to that desired by the aggressor, there is transformation in the way society views the aggressor. In addition to sharing of videos, images and information, digital media offer spaces for collaboration. People viewing this information from both sides of the conflict are able to organize and resist the oppressive regime that is creating the necropolitics or ‘deathworlds’ in which the aggressor decides who lives or dies. Such societal transformations enable new forms of interaction leading to social networks through online communities to be created.

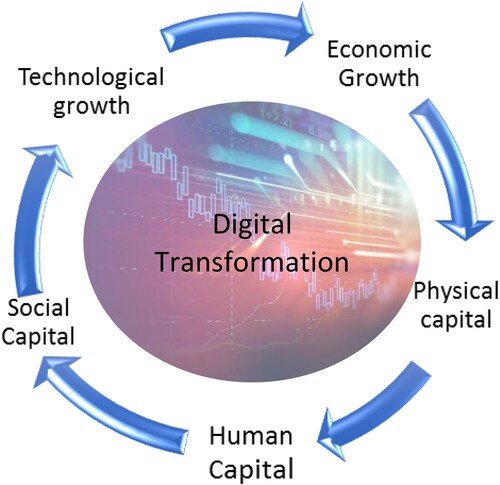

In the economic lives of the poor, Banerjee and Duflo (Citation2007) offer unique insight into why despite the devastation they face, people no matter how poor, will leave their devastated communities as a last resort. They state that the value of remaining close to their social network in a setting where the social network might be the only source of assistance available to people, keeps them close to home. Those who migrate for short periods of up to a few months leave their entire family behind can maintain their social links. A society that supports the education health and care of its people, tends to be more successful at achieving sustainable development. Economic growth fueled by human and social capital leads to sustainable increases in these factors without depleting natural resources. This is illustrated below:

The cycle in , illustrates how digital transformation can enable sustainable development. It highlights that through investments in human capital, technological growth can take place which then supports economic growth which then supports the creation of physical capital which are goods and services which require human capital to create. This is why human capital lies at the heart of the ability of people to live the lives they chose to live. People must be healthy, to gain the knowledge, skills and abilities to make the opportunities they need to lead the lives they choose to live. This is human capital. Digital transformation can also disrupt this cycle leading to negative cycles of development. Digital transformation can break down human capital when the use of the cell phone to doom scroll keeps people from doing their work. It can break down social capital when people do not go to the market or mingle with neighbors because they may have cars that allow them to live far away from neighbors and they can shop online to avoid the market.

When human beings share their resources or trade with each other through social relationships, they build social capital. Social capital is also needed for sustainable development to take place. The result of human interaction creates social capital which is a set of shared values that enable people to access information, resources, and other people to support their lives. Medina and Sole-Sedeno (Citation2023) summarize social capital definitions to include bonding social capital, which refers to relations within or between relatively homogenous groups; bridging social capital, which refers to relationships within or between relatively homogenous groups; and linking social capital, which refers to relationships between people or groups at different hierarchical levels. Social capital is needed to create and manage communities in which new knowledge, innovation and skills are created. In this regard, networks that are strong on bonding but weak on bridging can be powerful knowledge creators. While human capital is needed for physical capital to grow, it may also be created through social capital. According to social theory social relationships are resources that can lead to the development and accumulation of human capital (Machalek & Martin, Citation2015).

Technological growth takes place when innovative ICTs are developed to support the needs of people in communities. Human capital is needed for technology to be developed, adopted and distributed across communities. Technological growth takes place when the adoption of a particular technology lowers production costs and increases the growth of a business. The impact of learning on technology adoption is important for growth to take place. For example, when farmers learn how to use a new technology to increase productivity, other farmers potentially will do the same resulting in an increase in the diffusion of the new technology. Banerjee and Duflo (Citation2005) suggest that complementarity between human capital investment and investments in new technology is key to productivity and growth. Gains in productivity are made possible when there is capital to adopt productive technology. Innovative uses of mobile cell phones in low resource environments have been shown to increase incomes. This increase in incomes leads to investments in better technology among other human capital expenditures.

For digital transformation to support positive cycles of sustainable development, sustained investments in human capital are needed that offer the capability and motivation for people in marginalized communities to participate in the digital economy. They require skills to be able to access and use digital technologies to support their personal productivity. Digital transformation can be seen in the lives of displaced populations as they use applications on their mobile phones in frugal innovative ways to survive. From accessing their social relationships, supplies needed to survive, to making payments and earning money where possible. For example, web-based platforms can level the playing field for stakeholders. Seth et al. (Citation2023) argue that colonization was justified historically by an epistemic supremacy that individuals in Low- and Middle-Income Countries could not be producers of knowledge. This led to the destruction of knowledge systems and in the assumption today that communities in these countries do not have, or are incapable of, generating solutions to their own challenges. Colonization has further contributed to a refusal to learn from people who are local experts and a failure to understand that there are many ways to approach public health issues. Public health is important in this context as the health of the weakest affects all. They found that using web-based platforms, including web-applications, people from marginalized groups were able to participate, to speak up, and offer their local knowledge to solve pressing problems. An important lesson learned from using web-based platforms is that leveraging local knowledge enriches the research and increases the chances of successful implementations (Seth et al., Citation2023).

Human capital is the key to sustainable development because without it, physical capital, information technology and other factors of production may not function. Human capital is important because poverty is not just a lack of money, it is not having the capability to realize one’s potential as a human being (Banerjee & Duflo, Citation2011; Sen, Citation2001). Human freedoms are taken for granted while even those who survive into adulthood, are not free to choose the lives they choose to live. Human progress is primarily and ultimately about the enhancement of freedom and the achievement of development is dependent on the free agency of people (Sen, Citation2001). Positive cycles of development take place when human beings have the agency to make choices that lead them to use technologies to support their livelihoods and increase in incomes so they may lead healthy lives and invest in their education and social networks. The following section illustrates lessons learned from digital transformation through papers published in this issue.

3. Digital transformation for development lessons

This issue on digital transformation offers the ten papers published here represent a broad snapshot of current thinking on ICT4D. Contextual factors and the level of human and digital infrastructure effecting digital transformation are highlighted in the papers. A majority make at least some reference to digital transformation, and they provide an organic basis from which we can draw digital transformation for development lessons.

4. Digital transformation means structural change

Angelica Pigola, and Fernando Meirelles co-author the first paper in this issue titled: ‘Sustainable business value model in ICT4D research agenda.’ The authors argue that Information and Communication Technologies for Development (ICT4D) emerges as a sustainable practice since several studies are focusing on these positive aspects, such as digital financial inclusion and digital platforms for helping communities. Their study investigates how a sustainable business value model (SBVM) might be framed in ICT4D from the perspective of business practices. They perform a systematic literature review of 160 publications in the ICT4D research field from 2003 to 2022 using social network and content analysis. Their findings reveal six different business value perspectives to establish a sustainable business value model (SVBM) in ICT4D initiatives, suggesting a broader perspective for innovators and entrepreneurs to create new business formations for better development outcomes in their communities. Their paper contributes to socioeconomic development by identifying ways in which the SBVM may contribute to different communities’ development in emergent countries. Among the six types of value discussed by Pigola & Souza Meirelles is transformational value; a value that is seen to emerge only when businesses ‘restructure.’ Digital transformation, hence, does not mean piecemeal modification to organizational processes; it means changing structures. At the level of organizations, this implies doing business in a new way, using novel business models. At the level of societies, this implies a new ‘societal model.’

The second paper by Renai Jiang, Shenghao Yang, Sidong Lian & Gary H. Jefferson is titled: ‘The impact of internet development on green total factor productivity in China’s prefectural cities.’ They employ the global Malmquist-Luenberger index to measure the effect of Internet development on the green total factor productivity (GTFP) of China’s 283 prefectural cities. The authors found that by promoting high-quality development, the effect of Internet is significantly positive. Firstly, they explore the two mechanisms through which the use of the Internet promotes GTFP: improvements in the quantity and quality of urban innovation and the advancement and rationalization of urban industrial structures. Secondly, they compare the pre- and post-impacts of the Internet + initiative from which it draws critical policy implications. Finally, their threshold regression illustrates that when urban Internet penetration and employee wages rise to their respective threshold levels, the promotion effect of the Internet on GTFP can be further augmented. Meanwhile, from the perspective of Intensive Growth Theory, the Internet’s contribution to green labor productivity is more pronounced. Jiang et al. equate transformation with the green transition toward a truly sustainable mode of economic and social functioning, and identify – as with any current organizational or societal structural transformation – that ICTs will be central to affecting this type of significant change.

5. Digital transformation is possible if failure can be avoided

The ghost of failure still haunts the ICT4D field (Yim & Gomez, Citation2022), and in one way or another, it is the impetus behind some of the papers in this issue. For all the hype around digital transformation for development, this is a reminder of the prevalence of failure; something which, obviously, will prevent digital transformation from occurring. The papers in this issue all seek ways of reducing ICT4D failure, looking particularly at ways to use design science to improve the content or process of ICT4D design. Summaries of the papers are as follows:

Toward a process framework to guide the development of ICT4D programs: a South African perspective is the third paper in this issue by Lauren Lize Fouche, Sara Grobbelaar & Wouter Bam. They develop a new ICT4D design and development framework that particularly seeks to understand how to better operationalize co-creation. Two challenges, though, remain. They suggest that although a large body of literature exists to support the execution of Information and Communication Technologies for Development (ICT4D) initiatives, many such initiatives fail to deliver the intended results. They argue that the failure of ICT4D initiatives could be avoided by having a guiding framework that ensures the incorporation of activities that have supported the success of other ICT4D initiatives. By following a Design Science Research (DSR) methodology, their article presents a framework to integrate activities and processes noted in the literature to support the successful development of ICT4D initiatives. The result of the study is an evaluated process framework which serves as a tool to guide developers in identifying activities and processes that can support the success of ICT4D initiatives.

Designing ICTs for development. A Delphi study on problem framing, approach, and team composition is the fourth paper in this issue by Stephen Smith and Rico Lie. The authors suggest that many ICT4D projects fail, and this failure is partly attributed to the mismatch between the context in which ICTs are designed and the context of their use. Their study aims to understand the interplay between design and ICT4D by (1) making an inventory of design principles across three themes: problem framing, design approach, and team composition, and (2) assessing design statements (distilled from the list of design principles) through a two-round Delphi study with a group of ICT4D researchers and practitioners. The results show that while there is a general awareness of the importance of design in ICT4D, a consolidated effort to investigate how design principles can be more effectively integrated with ICT4D is missing. The study further concludes that there is a shift toward co-designing, that it is difficult to design without pre-determined ideas of using ICTs and emerging technologies. They conclude that transdisciplinary collaboration has not succeeded. As they show, it is one thing to understand the importance of better design principles, it is another to be able to put them into practice. The challenge is whether design science, with its emphasis on participatory approaches, can deliver transformative rather than just incremental change. There is certainly a belief that this is possible (Danneels & Viaene, Citation2022; Magistretti et al., Citation2021).

The fifth paper in this issue titled ‘Data management system for sustainable agriculture among smallholder farmers in Tanzania: research-in-progress’ is co-authored by Gilbert Exaud Mushi, Giovanna Di Marzo Serugendo and Pierre-Yves Burg. The authors contend that smallholder farmers produce about 70% of the world’s food and employ more than one billion people. They therefore have an important role to play in eradicating food insecurity and poverty among the world’s growing population. Although there are different digital services for smallholder farmers, the existing services lack sustainability in the agriculture context and hardly meet their needs. Data management and sharing among different agriculture stakeholders has the potential to make agriculture sustainable, but there is a need to enable access to digital services in an entire farming cycle under one roof. Their paper aims to propose the design of a comprehensive data management digital framework to solve common challenges of smallholder farmers in Tanzania and other countries’ agricultural systems. They follow the design science research (DSR) method to develop an artifact that interacts with the problem context. To illustrate the framework’s applicability, they use different case studies in Tanzania.

6. Context shapes digital transformation outcomes

Before and outside of ICT4D design comes context. A number of papers in this issue show how contextual factors shape and even determine the development impact of ICT4D. As illustrated by the papers here, for instance, there must be both institutional and infrastructural transformation. What are the implications here for our approach to ICT4D design and development? They might suggest that ICT needs to be de-centred and that contextual change needs to take a more central role in both envisioning and design. The summaries of the papers in this issue are as follows:

Himanshu Sharma and Antonio Díaz Andrade co-author the sixth paper in this issue titled: ‘Digital financial services and human development: current landscape and research prospects.’ Their study explores and analyzes the implications of digital financial services (DFS) on human development from a global perspective. Informed by a systematic literature review of studies published in the past two decades, from 2000 to 2020, this research unveils six overarching themes: contextual conditions, technological skills and financial literacy, consistent trust, shaping financial behavior, energizing economic activities, and supporting financial inclusion. Further analysis categorizes these themes into what constitutes the two intertwined dimensions of DFS: foundational conditions and effectual repercussions. They discuss how these dimensions enhance our understanding of the role information and communication technologies play in contributing to human development. Their study adds to our theoretical understanding of the role of ICTs in human development as it relates to managing money. Digital technology brings financial services to those living on the margins (e.g. disenfranchized individuals, remote communities) to expand their opportunities to manage and control their finances. They also present practical implications for different stakeholders in the financial sector. Contextual factors include the nature of formal and informal institutions are illustrated here.

The seventh paper in this issue, ‘Criminal factions and ICT-Mediated financial inclusion in Brazilian favelas: the role of context,’ is co-authored by Luiz Antonio Joia and Stefano Giarelli. The authors state that the city of Rio de Janeiro has the highest proportion of people living in favelas in Brazil and their residents have very restricted access to financial services, often needing to commute to other neighborhoods to make simple transactions. The objective of this article is to investigate the impact of a fintech startup, namely Banco Maré, on financial inclusion in a complex of favelas dominated by rival criminal factions that have imposed distinct codes of conduct on residents. Banco Maré was created to improve financial inclusion in the largest complex of favelas of Rio de Janeiro - Complexo da Maré. A model for ICT-mediated financial inclusion based on the Capability Approach was applied to evaluate this initiative in two favelas dominated by distinct criminal factions in the complex. The results suggest that financial inclusion depends on the nature of criminal factions dominating same. They found that in contexts where an institutional order that favors greater agency, empowerment and participation of residents prevails. This finding can strongly affect ICT-based financial inclusion initiatives in favelas dominated by lawless organizations. This paper is particularly vivid in showing how the structures of criminality in Brazilian favelas shape the outcomes of digital financial inclusion initiatives. But if – per lesson 1 – digital transformation means structural change, then for transformative outcomes to emerge from ICT4D there must be transformative contextual change.

7. Digital transformation requires transformation of capabilities

The final set of papers in this issue deal with digital exclusion. They argue that marginalized groups and individuals can only be successfully included in ICT4D initiatives – and hence benefit from ICT4D. Unless their capabilities permit, they will be excluded from digital transformation. Unless there is a transformation in capabilities – access to ICTs, requisite skills and knowledge – then digital transformation will merely exacerbate existing inequalities. And that capability transformation will also need to touch personal psychology: not merely enabling the marginalized to participate in digital transformation but motivating them to choose to do so. Yet again, this takes us back to ICT4D design and development approaches: do they or can they encompass the type of capability and psychological interventions necessary for ICT4D to deliver transformation? The summaries of the papers are as follows:

The eighth paper in this issue, co-authored by Mahdi Moeini Gharagozloo, Mahdi Forghani Bajestani, Ali Moeini Gharagozloo, Amirmahmood Amini Sedeh and Fatemeh Askarzadeh, is titled ‘The role of digitalization in decreasing gender gap in opportunity driven entrepreneurship.’ They argue that women entrepreneurs are a promising yet under-supported group that have notable impact on the economy. Recent societal attempts to empower female entrepreneurs and their critical role in economic development have motivated research on determinants of women’s participation in entrepreneurship and what can reduce gender disparities in this field. Drawing on insights from information economics, this paper emphasizes the recent transformations through digital technologies and examines the effect of digital readiness of an economy on women’s ability to close the gap on entrepreneurial activities. Using a sample of international observations over the 2010–2016 period, they show that the capability of an economy to exploit digital opportunities increases female participation in opportunity-driven entrepreneurship. The results also indicate that the positive role of digital readiness in women’s entrepreneurship strengthens populations with higher perceived opportunity and, more interestingly, higher fear of failure.

‘Explaining the digital divide in the European Union: the complementary role of information security concerns in the social process of internet appropriation,’ is the ninth paper in this issue co-authored by Giuseppe Lamberti, Jordi Lopez-Sintas and Jakkapong Sukphan. The authors suggest that most theoretical and empirical explanations of the generation of digital divides have been integrated into the resources and appropriation theory, which proposes a sequential model reflecting a socially unequally distributed digital divide. The unequal social distribution is reflected in Internet use that is sequentially influenced by motivations, attitudes, physical access, and digital skills. They extend the sequential model by exploring the complementary role of information security concerns in producing the digital divide. Using a predictive approach, they test a comprehensive partial least squares-structural equation model with data from a European Union survey, finding that information security concern is another significant determiner of the digital divide. Heterogeneity in social internet appropriation can be summarized in social mechanisms explained by education and age among well-educated Europeans, and by country digital development among less well-educated Europeans. They conclude with a discussion of theoretical and policy implications of their findings. Explicit in this paper is that if marginalized groups have a series of capabilities including physical access to ICTs, they can benefit from the transformations.

The final paper is co-authored by Yu Zhang, Hongquan Ao, Deng Weibin, and Yafen Yuan, is titled ‘Reducing technology-mediated service exclusion by providing human assistant support for senior citizens: Evidence from China.’ This study explores how the allocation of human assistants in a technology-mediated service setting could reduce the exclusion of senior citizens from such services. The authors employ a research methodology based on social support and protection motivation theories. Using a two-phase study with a mixed-methods approach, they conduct 25 semi-structured interviews to develop the research model. The model was then empirically validated using survey data from 285 Chinese senior citizens. The results revealed that senior citizens experienced defensiveness and avoidance behavior when facing technology-mediated services. However, perceived emotional support from a human assistant enhanced their evaluation of coping factors, further reducing their defence motivations and avoidance behaviors. Perceived instrumental support had a greater impact, as it both reduced their assessment of threat factors and enhanced their evaluation of coping factors. Finally, future time perspective moderated the effects of perceived support on threat and coping appraisal processing.

8. Conclusion

Digital transformation has been defined in the context of development. The double-edged sword that it carries in the development context is that inequities and oppression can increase unless there is a transformation in capabilities such as access to ICTs, requisite skills, knowledge and motivation to use the technologies by people to improve the lives they choose to live. In this, human capital is seen as the key to supporting positive cycles of sustainable development. Because without it, physical capital, information technology and other factors of production may not function. Human capital is important because poverty is not just a lack of money, it is not having the capability to realize one’s potential as a human being. Lessons learned through the papers in this issue include digital transformation means structural change is possible if failure can be avoided recognizing that context shapes digital transformation outcomes and requires transformation capabilities. The papers in this issue suggest that if marginalized groups have a series of capabilities including physical access to ICTs, appropriate skills and knowledge, the freedom to exercise their access and skills and a willingness to choose to exercise their access and skills. A willingness may be curtailed by factors such as lack of trust in the technology or in its owners and users or by a perception of other threats from digital system.

Acknowledgements

I am very grateful to Richard Heeks for his contributions and crucial feedback on multiple versions as they were revised through the many rounds of review. Very special thanks to Doug Vogel, Peter Wolcott, Maung Sein, James Pick and Silvia Masiero for their very insightful and detailed feedback on earlier versions of this editorial. It is because of these editors that the quality of work published in this Journal makes lasting contributions to knowledge and society. In addition to being exceptional peers in reviewing my work, they extend their expertise to upcoming rising scholars in the field through their scholarship, reviews, and guidance.

References

- Banerjee, A. V., & Duflo, E. (2005). Growth theory through the lens of development economics. Handbook of Economic Growth, 1, 473–552. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1574-0684(05)01007-5

- Banerjee, A. V., & Duflo, E. (2007). The economic lives of the poor. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 21(1), 141–167. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.21.1.141

- Banerjee, A. V., & Duflo, E. (2011). Poor economics: A radical rethinking of the way to fight global poverty. Public Affairs.

- Bock, J., Haque, Z., & McMahon, K. A. (2020). Displaced and dismayed: How ICTs are helping refugees and migrants, and how we can do better. Information Technology for Development, 26(4), 670–691. https://doi.org/10.1080/02681102.2020.1727827

- Danneels, L., & Viaene, S. (2022). Identifying digital transformation paradoxes: A design perspective. Business & Information Systems Engineering, 1–18.

- ElMassah, S., & Mohieldin, M. (2020). Digital transformation and localizing the sustainable development goals (SDGs). Ecological Economics, 169, 106490. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2019.106490

- Goldin, C. (2016). Human capital. In C. Diebolt & M. Haupert (Eds.), Handbook of cliometrics (pp. 55–86). Springer Verlag.

- Graham, M. (2019). Digital economies at global margins. MIT Press.

- Heeks, R., Ezeomah, B., Iazzolino, G., Krishnan, A., Pritchard, R., Renken, J., & Zhou, Q. (2023). The Principles of Digital Transformation for Development (DX4D): Systematic literature review and future research agenda. Working Paper Series. Centre for Digital Development Global Development Institute, SEED University of Manchester. https://hummedia.manchester.ac.uk/institutes/gdi/publications/workingpapers/di/dd_wp104.pdf.

- Heeks, R., Ezeomah, B., Iazzolino, G., Krishnan, A., Pritchard, R., & Zhou, Q. (2022). Development transformation as the goal for digital transformation. In R. Heeks (Ed.), ICTs for development blog. Centre for Digital Development Global Development Institute, University of Manchester. https://ict4dblog.wordpress.com/2022/12/13/development-transformation-as-the-goal-for-digital-transformation/.

- Heeks, R., & Shekhar, S. (2019). Datafication, development and marginalised urban communities: An applied data justice framework. Information, Communication & Society, 22(7), 992–1011.

- Iazzolino, G. (2021). Infrastructure of compassionate repression: Making sense of biometrics in Kakuma refugee camp. Information Technology for Development, 27(1), 111–128. https://doi.org/10.1080/02681102.2020.1816881

- Machalek, R., & Martin, M. W. (2015). Sociobiology and sociology: A new synthesis in international encyclopedia of the social & behavioral sciences, 892–898. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-097086-8.32010-4.

- Magistretti, S., Pham, C. T. A., & Dell'Era, C. (2021). Enlightening the dynamic capabilities of design thinking in fostering digital transformation. Industrial Marketing Management, 97, 59–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2021.06.014

- Malecki, E. J. (2002). The economic geography of the Internet’s infrastructure. Economic Geography, 78(4), 399–424. https://doi.org/10.2307/4140796

- Martin, A., & Taylor, L. (2021). Exclusion and inclusion in identification: Regulation, displacement and data justice. Information Technology for Development, 27(1), 50–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/02681102.2020.1811943

- Masiero, S., & Bailur, S. (2021). Digital identity for development: The quest for justice and a research agenda. Information Technology for Development, 27(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/02681102.2021.1859669

- Masiero, S., & Das, S. (2019). Datafying anti-poverty programmes: Implications for data justice. Information, Communication & Society, 22(7), 916–933.

- Mbembé, J., & Meintjes, L. (2003). Necropolitics. Public Culture, 15(1), 11–40. https://doi.org/10.1215/08992363-15-1-11

- Medina, F.-X., & Sole-Sedeno, J. M. (2023). Social sustainability, social capital, health, and the building of cultural capital around the Mediterranean diet. Sustainability, 15(5), 4664. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15054664

- Milan, S., Treré, E., & Masiero, S. (2021). COVID-19 from the Margins. Pandemic invisibilities, policies and resistance in the datafied society (Vol. 40). Institute of Network Cultures.

- Nemer, D. (2022). Technology of the oppressed: Inequity and the digital Mundane in favelas of Brazil. MIT Press.

- Pelinescu, E. (2015). The impact of human capital on economic growth. Procedia Economics and Finance, 22, 184–190. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2212-5671(15)00258-0

- Qureshi, S. (2022). Digital transformation at the margins: A battle for the soul of self-sovereignty. Information Technology for Development, 28(2), 215–229. https://doi.org/10.1080/02681102.2022.2062291

- Schoemaker, E., Baslan, D., Pon, B., & Dell, N. (2021). Identity at the margins: Data justice and refugee experiences with digital identity systems in Lebanon, Jordan, and Uganda. Information Technology for Development, 27(1), 13–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/02681102.2020.1785826

- Sen, A. (2001). Development as freedom. Oxford Paperbacks.

- Seth, R., Dhaliwal, B. K., Miller, E., Best, T., Sullivan, A., Thankachen, B., Qaiyum, Y., & Shet, A. (2023). Leveling the research playing field: Decolonizing global health research through web-based platforms. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 25, e46897. URL: https://www.jmir.org/2023/1/e46897.

- Taylor, L., & Broeders, D. (2015). In the name of development: Power, profit and the datafication of the global south. Geoforum, 64, 229–237.

- UNHCR. (2023). Refugee statistics. United Nations High Commission for Refugees. https://www.unrefugees.org/refugee-facts/statistics/?msclkid=632ca26b8a5e1dd9f247c723e642213e&msclkid=632ca26b8a5e1dd9f247c723e642213e&gclid=CMi_3aPFroIDFe6XxQIdSCEBqw&gclsrc=ds, Date Accessed 31 October 2023.

- Vial, G. (2019). Understanding digital transformation: A review and a research agenda. The Journal of Strategic Information Systems, 28(2), 118–144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsis.2019.01.003

- White, C. (2009). Understanding economic development: A global transition from poverty to prosperity? Edward Elgar.

- World Bank. (2020). The Human Capital Index 2020 update: Human capital in the time of COVID-19. © World Bank, Washington, DC. http://hdl.handle.net/10986/34432 License: CC BY 3.0 IGO.

- Yim, M., & Gomez, R. (2022). ICT4D evaluation: Its foci, challenges, gaps, limitations, and possible approaches for improvement. Information Technology for Development, 28(2), 251–274. https://doi.org/10.1080/02681102.2021.1951151

- Zuboff, S. (2015). Big other: Surveillance capitalism and the prospects of an information civilization. Journal of Information Technology, 30(1), 75–89. https://doi.org/10.1057/jit.2015.5