?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

This study on regional development investigates if digital transformation is a means to attract innovative establishments to municipalities. By doing so, the relationship between the availability of high-speed broadband close by and the number of innovative establishments (workplaces) across all 290 municipalities in Sweden is explored. Panel data for eleven years (2010-2021) originate from official registers. Results based on Fixed Effects Poisson estimations including spatially weighted variables indicate that the digital transformation in the guise of high-speed broadband access is important for ICT (micro) establishments and those in declining municipalities, although the proportion of highly skilled inhabitants renders stronger estimates. For high technology and R&D establishments, access to high-speed broadband is not a relevant location factor. The estimates are robust to endogeneity as tested by the control function approach.

1. Introduction

Support for ICT, such as high-speed broadband infrastructure, is a typical measure used in the context of digital transformation to reduce poverty and inequalities or improve regional competitiveness (Abrardi & Cambini, Citation2019; Das & Chatterjee, Citation2023; Harris, Citation2011; Kartiasih et al., Citation2023; Mayer et al., Citation2020).Footnote1 Despite this, literature shows ambiguous results from analyses of the link between broadband access and employment or firm performance at the regional level (Duvivier & Bussière, Citation2022; Falk & Hagsten, Citation2021; Haller & Lyons, Citation2019). There is, however, slightly more solid evidence for the location of firms or establishments, even if available studies are geographically concentrated and use a variety of methods, definitions as well as granularity of data. Good broadband infrastructure may increase the number of firms or establishments in rural areas (Audretsch et al., Citation2005; Deller et al., Citation2022; Duvivier et al., Citation2021; Tranos & Mack, Citation2016). In combination with access to a certain level of highly educated individuals, the importance of broadband access is considered even stronger (Falk & Hagsten, Citation2021; Hasbi, Citation2020; McCoy et al., Citation2018).

This study on regional development empirically investigates if digital transformation is a means to attract innovative establishments to municipalities. By doing so, the relationship between the availability of high-speed broadband close by and the number of innovative establishments (workplaces) across all 290 municipalities in Sweden is explored. Municipality is the lowest administrative level in Sweden. Control variables include the number of highly educated inhabitants and other time-variant factors that might affect the number of innovative establishments. Special emphasis is put on micro-sized establishments and municipalities with declining populations due to presumptive non-heterogeneous access to high-speed broadband.

An establishment is defined by its location in accordance with official statistics and not by its legal form and is thus particularly suitable for regional analyses since there is no uncertainty about where the operations are taking place.Footnote2 The concept of innovative establishment follows the definition made by Eurostat based on the statistical classification of economic activities across industries in the European Union (NACE Rev. 2). This definition encompasses all firms or workplaces in the high technology manufacturing industries 21, 26 and 30.3 as well as those in knowledge intensive service industries 59–63 (ICT) and 72 (R&D). Digital transformation is approximated by the proportion of establishments with high-speed broadband access nearby. Fixed Effects count data models are employed for the estimations where the panel data originate from several official registers in Sweden and span over eleven years (2010–2021).

The prospect of growth in a region may take different paths: make the best use of existing assets, simplify value chains, diversify or attempt to enlarge the knowledge base (Capello & Lenzi, Citation2018; Smidt, Citation2022). Thus, success is not only related to the regional ability to exploit and harness innovations (broadband, for instance) but also to the existing as well as a future base of knowledge and the possibility to attract new firms. Highly innovative firms may create beneficial spillovers both within and across industries (Capello & Lenzi, Citation2015). Knowledge intensive and high technology industries are particularly relevant for regional development, since they are likely to create externalities within and across industries as well as geographically (Audretsch & Feldman, Citation2004; Jaffe et al., Citation1993). There is also evidence that industries with more prevalent knowledge spillovers have a larger propensity to cluster than other groups of firms (Audretsch & Feldman, Citation1996).

Another aspect that could typically affect the attractiveness of a region is the occurrence of unforeseeable large-scale external events, such as a pandemic. During the initial spread of the Covid-19 virus, the increased numbers of individuals working from home distance themselves from heavily agglomerated areas (Dingel & Neiman, Citation2020). To what extent this development affects industries, firms and workplaces is presently unknown.

Innovative activities are found to be related to the spatial extent of the labour market of the firm (McCann & Simonen, Citation2005). This implies that the local labour markets for highly skilled individuals are larger than a single municipality. The up- and downstream value chains of the establishments are also not necessarily limited to a small region. Indeed, there are signs of spatial dependencies in the literature on the relationship between broadband, highly skilled labour and business creation (Deller et al., Citation2022; Duvivier, Citation2019; Duvivier et al., Citation2021; McCoy et al., Citation2018; Whitacre et al., Citation2014). Because of this, presumptive cross-municipality dependencies are taken into account by spatial estimations.

Haefner and Sternberg (Citation2020) investigate the state of existing research on spatial implications of digitization. One of their findings is that there is a need for comprehensive data and a deeper understanding of the role played by regional digital competencies in generating effects. Digital transformation, although not well-understood, is expected to provide an excellent field for regional entrepreneurship research (Sternberg, Citation2022). Recent literature commonly discusses the digital transformation from the perspective of a firm or public institution, for instance (Kraus et al., Citation2021; Verhoef et al., Citation2021; Vial, Citation2019). A novelty of this study is the focus on the layer below this: the transformation of the infrastructure. Thus, present analysis contributes new insights at the very detailed level on the extent to which the digital transformation in the shape of access to high-speed broadband nearby or in the neighbouring areas helps to attract innovative establishments to a municipality. That is, whether this facilitates regional economic development. Separate estimations for declining municipalities reveal to what extent this access is also a factor of importance for recovery in general, while the inclusion of data until 2021 indicates if historical patterns of location of establishments within the specific industries are still valid.

This introduction is followed by sections on the conceptual background, empirical approach, results and conclusions.

2. Conceptual background

Remedies to reduce spatial imbalances may stand in contrast to efficient resource allocation (Andrews et al., Citation2015; Bartelsman et al., Citation2013), especially if the theoretical underpinning relates to beta convergence assumptions of a zero-sum game (Harris, Citation2011). It is, however, not necessarily always an imbalance in the resources available but in the capacity to exploit them (Capello & Cerisola, Citation2021). A facilitator, such as increased access to a general-purpose technology in the shape of high-speed broadband access, could help the region both to make better use of its resources and to improve its competitive advantage (Duvivier, Citation2019; Harris, Citation2011).

Literature on the impact of broadband access on the number of firms or business start-ups is increasing, although the level of granularity as well as methods vary and there is a bias toward North American contexts (Duvivier, Citation2019). An exploration of the importance of broadband speed in the state of Ohio (United States) using linear regression with spatial elements reveals that it is most important for businesses in agriculture and firms in rural areas (Mack, Citation2014). Tranos and Mack (Citation2016) exhibit that a good broadband internet infrastructure leads to an increase in the number of knowledge intensive service firms in the United States counties based on a Granger causality test approach.

Another study on United States counties reveals that there is spatial heterogeneity in the relationship between firm formation and broadband access using OLS regressions (Parajuli & Haynes, Citation2017). Kim and Orazem (Citation2017) apply the difference-in-differences approach to demonstrate that access to early generation broadband is positively and significantly related to the location choice of new firms in the United States rural areas, although the effect varies with agglomeration. There is a positive impact of broadband in rural areas of Iowa and North Carolina and the magnitude is larger in more densely populated rural areas adjacent to metropolitan areas.

Mack and Wentz (Citation2017) investigate if the initial broadband level is of importance for different industries across United States regions and find that this is only the case for knowledge intensive businesses that have a special need for frequent infrastructure updates in terms of platforms and speeds. A recent study on non-metropolitan counties in the United States employs a Bayesian spatial Tobin estimator on cross-sectional data and exhibits that (especially downloading) broadband speed is of importance for the local start-up rates (Deller et al., Citation2022). By use of data on the number of broadband providers in the United States and instrumental variable regression analysis, Conroy and Low (Citation2022) reveal that broadband access is valuable for start-ups in rural areas, particularly so if they are run by sole proprietors or led by women. An instrumental variable approach based on data for the United States reveals that the disruptive phase of broadband access impacts business creation, especially so for knowledge intensive firms and that broadband may also crowd out business activities in the manufacturing sector (Stephens et al., Citation2022).

European evidence on how firm location relates to broadband infrastructure is growing. Count data modelling shows that municipalities with high-speed broadband access in France are more attractive for new firms, particularly in combination with a certain level of education in the local population (Hasbi, Citation2020). Based on Tobit estimations with spatially lagged variables, Duvivier et al. (Citation2021) report positive and significant associations between broadband provision and firm birth in all types of French regions except the rural ones, independent of broadband speed. Additionally, the authors find that certain knowledge intensive industries may be positively affected even in rural areas. On the contrary, difference-in-differences estimations for the Italian region of Trento exhibit no impact on the number of firms from improved broadband speed (Canzian et al., Citation2019). Duvivier and Bussière (Citation2022) also use difference-in differences estimations and demonstrate that access to high-speed broadband is only partially related to the local firm dynamics, in this case, broadly defined knowledge intensive services in regions with already good underlying economic conditions.

In the case of Sweden, outcomes of Fixed Effects and Spatial Durbin model estimations reveal a significant but small direct effect of lagged high-speed broadband access on the number of establishments (workplaces), mainly driven by micro establishments (Falk & Hagsten, Citation2021). However, this effect is much stronger when combined with the local presence of university educated employees and researchers. Negative-binomial panel estimations on Irish urban regions outside the capital city add to the evidence that broadband access is a determinant of the location of new business establishments and that this effect is larger in areas with higher educational attainments (McCoy et al., Citation2018). Start-up activities in Germany are also found to be enhanced by specific infrastructures, in this case, the early generation of broadband estimated by OLS (Audretsch et al., Citation2015). Two other analyses on German data using OLS reveal that high-speed broadband access, as opposed to general broadband, does not automatically translate into higher firm entry rates at the regional level (Sarachuk et al., Citation2021).

As highlighted, not only the coverage and identification strategies vary across studies, but also how broadband access is measured or defined. Early studies mainly use an indicator of broadband infrastructure availability instead of an intensity measure of its usage and there are few studies that employ high-speed broadband access in their models (Duvivier, Citation2019). Examples of measures include a dummy variable for availability in a given area (Lehtonen, Citation2020), a dummy variable for specific fiber speed (Duvivier & Bussière, Citation2022), the number of subscriptions (> 512 Kbps) per 100 inhabitants (Jung & López-Bazo, Citation2020), the number of broadband providers (Conroy & Low, Citation2022; Stephens et al., Citation2022) and broadband speed of ASDL connections (Ahlfeldt et al., Citation2017). Each of these measures suffers from different limitations. For instance, the number of broadband providers does not measure actual take-up, and broadband can be considered used even if only one client in a given area (postcode) subscribes to the service (Conroy & Low, Citation2022). Recently, there is also a smaller group of studies that benefit from continuous measures for broadband access with a certain speed of at least 100 Megabits per second, something that gives more accurate and detailed information on specific areas (Deller et al., Citation2022; Falk & Hagsten, Citation2021; Hasbi & Bohlin, Citation2022).

To control for possible endogeneity of broadband access several different approaches are used: instrumental variables (Stephens et al., Citation2022), difference-in-differences models (Kim & Orazem, Citation2017) and the regression discontinuity approach (Ahlfeldt et al., Citation2017).

Despite the variations in identification strategies, definitions, time periods and the access to and granularity of data, there are studies that indicate that broadband infrastructure is crucial for the regional attractiveness, even if the needs may differ across industries. There is also an emphasis on the importance of highly skilled labour and its possibly moderating role in ICT access such as broadband infrastructure. Literature suggests that the relationship between broadband or ICT access and performance depends on the skill level of residents (Alderete, Citation2017; Atasoy, Citation2013; Bertschek et al., Citation2015; Flaminiano et al., Citation2022).

Few studies consider both the possible dynamism over time and spatial dependencies of the firms or establishments in the high technology and knowledge intensive industries (Duvivier, Citation2019). One exception is Mack and Wentz (Citation2017) who find long-lasting effects of broadband spillovers on business activity from core hubs in neighbouring areas. Literature on broadband access and declining regions is also scarce.

Broadband access and the proportion of university graduates are certainly not the only factors that might make a region attractive for innovative firms. Well before the overall roll-out of broadband infrastructure or availability of such data, size, industry intensity, agglomeration, population density, income growth, closeness to university as well as public support in the shape of general infrastructure investments, for instance, are well-known aspects of importance for the location choice of a firm or a plant (Arauzo-Carod et al., Citation2010; Armington & Acs, Citation2002; Audretsch et al., Citation2005; Audretsch et al., Citation2015; Bennett, Citation2019;; Bhat et al., Citation2014; Conroy & Low, Citation2022; Delfmann et al., Citation2014 McCoy et al., Citation2018). Correspondingly, local amenities, such as coasts, nature et cetera, are potentially crucial for firm location, especially in rural areas (Duvivier & Bussière, Citation2022; Naldi et al., Citation2021). The weight of determinants may even vary over the plant life cycle (Holl, Citation2004).

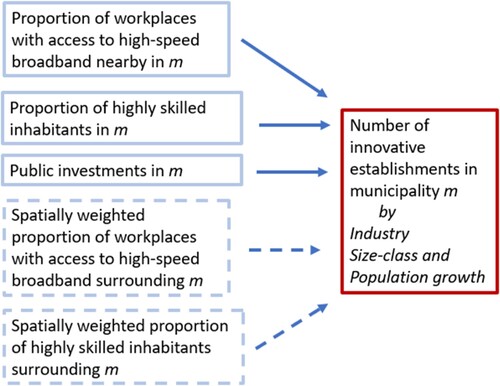

The Fixed Effects count data model employed in this study implies that several aspects of importance for the number of innovative establishments in a certain municipality cannot be included in the estimations due to their time-invariant status. This means that closeness to a university, agglomeration, land characteristics and distances are variables excluded from the analysis, despite their presumptive relevance for innovative firms. Income is, in principle, another outcome variable and is exempted because of that. Thus, the number of innovative establishments is conceptualized as being determined by the time-variant variables for highspeed broadband access, highly skilled inhabitants and public investments, as justified by recent and seminal literature discussed in this section. Due to the fact that many establishments are connected via different value chains and that the local labour markets are commonly larger than a single municipality (Boschma et al., Citation2008; McCann & Simonen, Citation2005; Öner, Citation2017), both the broadband and skills variables are tested in their spatial formats.

The research question may be illustrated by a conceptual model where the boxes to the left frame the independent variables and those to the right the different dependent ones (). Solid lines around the boxes imply variables with presumptive direct relationships to the dependent variables and the dashed lines relate to possible indirect effects. Direction of causality is indicated by a set of arrows.

Figure 1. Conceptualisation of research question. Notes: The arrows indicate expected causality. Source: Own illustration.

Regional policy measures such as investment incentives for research and development, new infrastructure, environmental protection and tourism are common measures used that may lead to an increase in local employment in industrially declining regions (Bondonio & Greenbaum, Citation2006). Thus, investment in broadband access could be more pertinent for the number of innovative establishments in declining rather than in growing regions where different infrastructures are already more developed. In his study, possible deviating patterns for declining areas are controlled for by separate estimations for municipalities that experience depopulation during the period of time studied.

Because this analysis is based on a deeper level of detail than is commonly investigated (establishment instead of firm), an assumption is made that the general relationships outlined in literature are valid. This suggests that a direct relationship between high-speed broadband access and the number of innovative establishments is expected to occur when other regional time-variant characteristics are controlled for. The relationship may also appear indirectly if, for instance, the establishments are dependent on the broadband access of their collaborators or affiliates in neighbouring municipalities or on highly skilled individuals from a larger local labour market than that of the single municipality. Declining municipalities could exhibit a different pattern than growing ones. Even if the Covid-19 pandemic with increased remote work and resistance to agglomerations (Dingel & Neiman, Citation2020) affects many aspects of everyday life, the years 2020 and 2021 might be too short a time span for detecting a possible new location pattern for establishments.

3. Empirical approach

Studies on broadband access and the location of or number of firms employ a variety of approaches including difference-in-differences methods, Bayesian models, count data and linear regressions with or without spatial elements (Audretsch et al., Citation2015; Canzian et al., Citation2019; Deller et al., Citation2022; Duvivier, Citation2019; Hasbi, Citation2020; Kim & Orazem, Citation2017; Mack, Citation2014; McCoy et al., Citation2018). Fixed Effects count data modelling with spatial effects is less common. An earlier comprehensive literature review on factors of importance for industrial location emphasizes that the use of flexible and encompassing specifications based on various levels of geographically aggregated (panel) data and spatial econometrics techniques would be a promising line for future research (Arauzo-Carod et al., Citation2010). Recent studies on establishment location increasingly consider spatially lagged explanatory variables in count data, but not the unobserved time-invariant fixed effects (Liviano & Arauzo-Carod, Citation2014). Bhat et al. (Citation2014) study location choice in Texas based on spatial modelling of count data and an extensive set of variables, although broadband infrastructure is excluded from the specification and the data are cross-sectional.

The dynamics of innovative establishments in municipalities are modelled as a function of high-speed broadband access, presence of inhabitants with tertiary university or research degrees and public investments at the municipal level. Thus, the empirical specification relates the number of establishments (Y) for the chosen industry (i) in a given municipality (m) and year (t = 2010-2021) to the high-speed broadband access (), availability of highly skilled inhabitants

, public investments

time effects (

) and the error term

, for the given size class:

(1)

(1)

The municipality fixed effects are represented by . Variables

,

and

are all lagged one year to allow for delayed responses related to planning and installation time. As a robustness check an interaction term between the proportion of highly skilled inhabitants and the broadband access variable is tested.

The spatially weighted versions of the broadband and skills variables

, are used to account for possible regional spillover effects or dependencies, leading to the following specification, given size class:

(2)

(2) where parameters

and

measure the relationship between the number of innovative establishments in the municipality on the one hand and the spatially weighted proportion of establishments with high-speed broadband access or the proportion of individuals with higher skills in the neighbouring municipality on the other. This specification represents a spatially lagged model (SLX) (Halleck Vega & Elhorst, Citation2015). Spatial econometric modelling, although without count data, is also employed by Briglauer et al. (Citation2021), who find that broadband availability in neighbouring districts is significantly and positively related to regional GDP. A test for time-invariant spatial dependence can be used to assess if the parameter estimates of the Fixed Effects Poisson estimator and its robust (sandwich) variance are consistent (Bertanha & Moser, Citation2016).

Since the dependent variable has a certain proportion of zero values and a skewed distribution, a Fixed Effects panel count data model is required for the estimations. In the group of municipalities, 17.1 per cent do not host any R&D service and 16.8 per cent no high technology manufacturing establishments (source: Statistics Sweden and Swedish Agency for Economic and Regional Growth). Thus, the Fixed Effects Poisson estimator with cluster-adjusted standard errors (at the municipality level) is employed, with spatially weighted explanatory variables in the second step. This estimator is more favourable for panel count data than the Fixed Effects negative binomial estimator (Wooldridge, Citation1999). Fixed effects models explicitly account for unobserved time-invariant location factors (such as the presence of universities) and are therefore preferable to cross-sectional regression models (Holl, Citation2004).

3.1. Test for endogeneity

The issue of endogeneity is commonly raised in relation to impacts of broadband deployment (Kim & Orazem, Citation2017). Haller and Lyons (Citation2019) argue that, unlike adoption, broadband access is external to the institution and therefore does not raise endogeneity and unclear causality concerns in the short term. Despite this, endogeneity of broadband access cannot be fully ruled out. Previous studies show that internet provision is significantly positively related to city size, metropolitan status and knowledge intensity (Tranos & Gillespie, Citation2009). To test for endogeneity the control function approach within the count data framework is employed where the high-speed broadband variable is instrumented by the proportion of households with broadband nearby (Lin & Wooldridge, Citation2019). This variable is less likely to be a factor of attractiveness for the location of innovative establishments.

In the control function approach, the t-test on the residual of the first stage regression can be used as a check for the endogeneity of high-speed broadband. If the null hypothesis stating that the coefficient of the fitted residual is zero cannot be rejected, endogeneity can be ruled out. The standard errors of the number of innovative establishments are bootstrapped in the equation to account for the fact that the fitted residual is a predicted regressor. In practice, the first stage of the estimation only includes a regression of the proportion of establishments with high-speed broadband access on a similar measure for household access and time effects.

4. Data and descriptive statistics

Data for the analysis originate from several official registers. Information on establishments, size classes and industries at the five-digit level for the period 2010–2021 is available in the regional database RAPS-RIS held by the Swedish Agency for Economic and Regional Growth together with Statistics Sweden.Footnote3 This database may be accessed through a licence agreement. The concept of innovative establishments follows the NACE Rev. 2 Eurostat statistical classification of economic activities and includes (a) high technology manufacturing industries (21, 26 and 30.3) as well as (b) high technology knowledge intensive ICT (59-63) and R&D (72) service industries. Present definition is narrower than that used by Stephens et al. (Citation2022), for instance, who include all knowledge intensive business services.Footnote4

Population and education data for the same period are obtainable from Statistics Sweden.Footnote5 The latter refers to the proportion of the night population of all ages with tertiary or higher degrees. Declining regions can be defined in several ways, in terms of employment or in inhabitants (Pekkala, Citation2003), for instance. In this study, municipalities that experience depopulation during the time period studied are considered to be declining. The Swedish Post and Telecom Authority provides data on workplace and household broadband access of a certain speed nearby, in this case a minimum of 100 Megabits per second for the years 2009-2021.Footnote6 Information on public investments at the municipal level is available for the period 2009–2020 from Kommuninvest.Footnote7 Geographic longitude and latitude of the centre of each municipality are used to create the spatial matrix based on information from Google maps. The spatial weight matrix W is calculated based on the geographical distances between municipalities, information on longitude and latitude positions and the exponential decay function (Kondo, Citation2015).

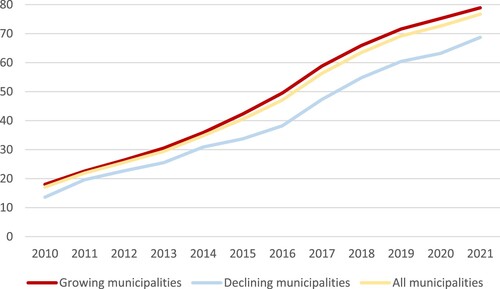

The lowest administrative level in Sweden is the municipality, of which there are 290 with a median size of 22,000 inhabitants. One out of five municipalities experiences a population decrease during the period of time studied (). These municipalities are smaller, with a median of 7,000 inhabitants and are commonly located in the north or the inland of Sweden.

Figure 2. Declining municipalities in Sweden. Notes: There are 290 municipalities in Sweden. Approximately one out of five experience a decline in population during the years 2010–2021 (darker shade). Source: Statistics Sweden.

Descriptive statistics show that there are almost 69,600 innovative establishments in 2021, representing approximately five per cent of the universe (). Among these, the ICT establishments are by far the largest group in numbers and the high technology manufacturing establishments the smallest, although the reverse is valid for their sizes.

Table 1. Development of number of innovative establishments.

Almost one out of five municipalities has neither an R&D service facility nor a high technology manufacturing establishment, with the former mainly appearing in the larger Stockholm area, Uppsala, Malmö, Lund and Gothenburg. The ICT establishments exhibit the fastest growth over time, especially the smaller ones (with 4.0 and 5.9 per cent, respectively), while the number of high technology manufacturing establishments is stagnating or diminishing. There are particularly few innovative establishments in the declining municipalities: an average of 93 high technology in manufacturing and 93 R&D service establishments.

The proportion of workplaces with high-speed broadband access nearby increases from 17 to 77 per cent on average between the years 2010 and 2021 ( and ). Declining municipalities experience a slower development where the gap to the average increases over time and reaches slightly more than ten percentage points in 2021. This trend goes in the opposite direction of that in the emerging country Indonesia, for instance, where a digital divide is found to contract over time (Kartiasih et al., Citation2023).

Figure 3. Proportion of establishments with high-speed broadband access nearby (per cent). Notes: The evolution is measured as unweighted means across municipalities. Source: Swedish Post and Telecommunication Agency.

Table 2. Development of independent variables across municipalities, unweighted averages.

Not only the proportion of establishments with high-speed broadband access, but also the proportion of inhabitants with tertiary degrees are lower in the declining municipalities with a widening gap over time (). Contrary to the high-speed broadband access and the proportion of highly skilled inhabitants, the lower average debt of the declining municipalities follows more naturally from the fact that they are also smaller. Additional summary statistics for the estimation sample of 290 municipalities and the 3190 observations are available in .

Table 3. Summary statistics estimation dataset.

5. Empirical results and discussion

Results of the Fixed Effects Poisson estimator show that high-speed broadband access is positively related to the number of ICT service establishments in the municipality with a coefficient of 0.06 at the one per cent significance level, when time effects, availability of highly skilled inhabitants and municipal investments are controlled for (, Specification i). The magnitude of the relationships is higher for micro establishments with one to nine employees (with a coefficient of 0.15 and p-value < 0.01) and for those in the 62 declining municipalities (with a coefficient of 0.24 and p-value < 0.05) (, Specification ii and ). Despite this, there is evidence that the number of establishments is more strongly driven by the availability of highly skilled inhabitants, especially so in the group of smaller ICT establishments, while municipal investments are not significant or exhibit the wrong sign. Highly skilled inhabitants are also of importance for the R&D establishments (p-value < 0.01).

Table 4. Importance of high-speed broadband access for innovative establishments across municipalities, Fixed Effects Poisson regressions.

Table 5. Importance of high-speed broadband access for innovative establishments in declining municipalities, Fixed Effects-Poisson regressions.

Estimation coefficients can be interpreted as semi-elasticities (in the case of high-speed broadband and highly skilled inhabitants) or elasticities (public investments). On average, an increase in high-speed broadband access by ten percentage points leads to a surge in the number of ICT service establishments by 0.6 per cent. The 60 percentage points increase in high-speed broadband access during the period of time studied, means that the number of ICT service establishments increases by on average five (0.06 × 0.60 × 141 ICT establishments in 2010). This represents 6.5 per cent of the total growth of these establishments (0.06 × 0.60/76.7 = 0.065, ). A similar calculation for the declining municipalities renders a growth by three ICT service establishments over time. This represents two-thirds of the total rise in the number of these establishments. Thus, the impact of broadband access on the number of ICT service establishments is by far more effective in municipalities with declining populations.

The lack of significant links for the R&D establishments could be explained by their high geographical concentration: Five municipalities (and adjacent ones) are home to more than 60 per cent of them while, for instance, there are ICT service establishments in almost all municipalities.

Estimations based on the sub-group of municipalities with de-population during the period of time studied stress the importance of high-speed broadband infrastructure nearby as a factor of attractiveness for the knowledge intensive ICT establishments, although the skills of the local inhabitants are not of relevance for this group of establishments (). Instead, there is an indication that the number of R&D establishments is thriving with access to highly skilled inhabitants (p-value < 0.01).

Another crucial finding is that high-speed broadband access in neighbouring municipalities is important for both the ICT and R&D establishments, as confirmed by the Wald test of joint significance (). In addition, there is a substantially significant and positive spatial association with highly skilled inhabitants in the neighbouring municipalities for all three groups of innovative establishments, although the strength of the relationship is weaker for the high technology manufacturing establishments. This finding confirms that the labour market for skilled individuals is larger than the sole municipality.

Table 6. Importance of high-speed broadband access for innovative establishments including spatial dependencies across municipalities, Spatial Fixed Effects-Poisson regressions.

The possibility of a changed pattern during the pandemic years of 2020 and 2021 is tested by recursive estimations on the subgroup of ICT establishments with 1–9 employees with the largest significance and positive estimates in the baseline regression. Results for the time splits 2011–2019 and 2011-2020, show that the sign and significance of the broadband coefficients are increasing over time, something that could also accommodate a pandemic effect. The broadband coefficients (and their respective z-stats) in the two split equations are 0.089 (2.20) for the years 2011-2019, 0.11 (2.78) for 2011–2020 and 0.148 (3.58) for 2011–2021 (as reported in , specification ii for the latter).

Despite different granularity of data and estimation methods, the results coincide to some extent with existing research in that there is a relationship between broadband access and number of firms or establishments at the local level (Deller et al., Citation2022; Duvivier et al., Citation2021; Falk & Hagsten, Citation2021; Hasbi, Citation2020; Mack, Citation2014; McCoy et al., Citation2018; Stephens et al., Citation2022). The importance of skills is also highlighted in some recent studies (Falk & Hagsten, Citation2021; Hasbi, Citation2020; McCoy et al., Citation2018). However, there is no other study that jointly analyses innovative establishments based on Fixed Effects count data estimations where also diminishing regions as well as the possible reverse of establishment behaviour in 2020 and 2021 are taken into account. As opposed to Duvivier and Bussière (Citation2022), who find that municipalities without good conditions in terms of local economic climate, amenities and demography do not benefit from high-speed broadband access, there is evidence of a stronger relationship between the number of ICT establishments and broadband access in the declining municipalities.

5.1. Robustness checks

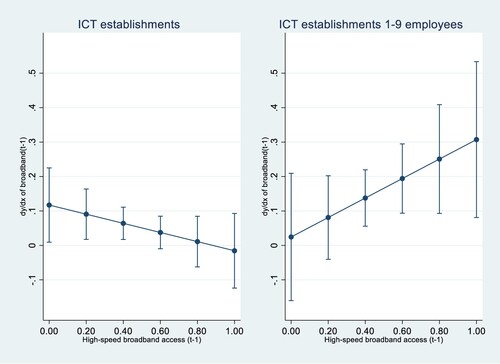

There is a risk that the importance of broadband infrastructure access weakens by intensity. Because of this, a quadratic term is added to the estimations as a robustness check. These estimations reveal that the positive and significant relationship is indeed diminishing for the ICT establishments (). On average, there is an upper threshold of 60 per cent of broadband access close by beyond which there is no significant link observed for the ICT establishments. In contrast, the marginal effect of high-speed broadband access on the micro ICT establishments grows with increasing intensity. This implies that the non-linear relationship deviates from the pattern representing the total group of ICT establishments.

Figure 4. Estimates of quadratic form of high-speed broadband access on ICT establishments. Notes: Calculated using the delta method based on specification in upper panel (Specifications i and ii) and augmented by a quadratic term for broadband access. Source: Kommuninvest, Statistics Sweden, Swedish Agency for Economic and Regional Growth, Swedish Post and Telecommunication Agency and own calculations.

Following Lin and Wooldridge (Citation2019), endogeneity is tested by the control function approach with household high-speed broadband access as the instrumental variable. The first stage of the estimation consists of a Fixed Effects regression where the broadband variable is regressed on the proportion of households with high-speed broadband access nearby and time effects. After this, the first-stage residuals are included as control variables in the second stage Fixed Effects Poisson regression determining the number of innovative establishments. Results show that the fitted residual is not significantly different from zero, implying that there is no endogeneity problem (). The test for time-varying spatial dependence developed by Bertanha and Moser (Citation2016) shows that the assumption of time invariance cannot be rejected.

Table 7. Importance of high-speed broadband access for the number of ICT establishments across municipalities, controlling for endogeneity.

Additional robustness checks include interaction terms between the highly skilled inhabitants and the broadband access variables (, Specifications iii and iv). This interaction tests whether the relationship between broadband and establishment dynamics depends on the skill level of the inhabitants. Estimation results reveal that a relationship can only be observed for ICT establishments in municipalities with higher-than-average shares of the broadband access. An opposite relationship is found for the high technology manufacturing establishments.

6. Conclusions

This study on regional development investigates if the digital transformation is a means to attract innovative establishments to municipalities. By doing so, the relationship between the availability of high-speed broadband access close by and the number of innovative establishments (workplaces) across all 290 municipalities in Sweden is explored. Establishments rather than firms are particularly useful in this analysis, since they are defined by their location and not by legal entity, implying that changes in ownership, acquisitions, mergers or re-orientation of operations cannot distort estimations. Panel data employed for the analysis originate from official registers in Sweden. These kinds of data, together with Fixed Effects count data modelling, are still uncommon in literature.

6.1 Results and implications

Estimation results including the spatially weighted variables indicate that the digital transformation in the guise of high-speed broadband access is still of importance for the development of certain firms and their establishments across municipalities. The estimates are robust to endogeneity as tested by the control function approach. However, just as there is a certain heterogeneity across establishments, this is also valid for different kinds of municipalities. On average, the link between broadband access and establishments is positively significant for the ICT service, but not for the R&D and high technology manufacturing establishments, although with a smaller magnitude than highly skilled inhabitants. Micro establishments gain the most and the effect is stronger for declining municipalities. This could mean that broadband access is of particular weight for the development of entrepreneurial ICT service activities in the weaker municipalities. Indirectly, the R&D and high technology establishments may also benefit if they consult the ICT entrepreneurs. Thus, the finding leads to implications for the design of possible policy support measures, in that the characteristics of firms, establishments, regions or persons targeted need to be carefully considered in advance.

The much stronger link to the availability of highly skilled individuals, however, emphasizes the importance of absorptive capacity when presumptive policy measures for recovery or support are designed. In the case of high technology and R&D establishments, high-speed broadband access is not a relevant location factor. R&D services are markedly persistent, and the geographical concentration is strong with a majority of establishments in the vicinity of the largest cities and universities (Greater Stockholm area, Uppsala, Malmö, Lund and Gothenburg). A new location for a technical university might be more effective in spurring local R&D activities. There is, though, a spatial dependence on highly skilled inhabitants for all the innovative establishments, implying that the source for employees is likely found within a larger labour market area than the sole municipality.

It is puzzling that highly skilled inhabitants and broadband connections do not play a role in attracting high technology manufacturing. One reason could be that the foundation of these establishments is infrequent and requires a larger time window for the analysis. The relationship between high-speed broadband and number of ICT service establishments is increasing over time, possibly also accommodating a slight influence of activities during two years of the Covid-19 pandemic (2020 and 2021).

6.2. Limitations and future work

The study holds several limitations. Although the dataset is vast and the level of granularity is deep, it is not clear if the conclusions can be applied to countries that deviate in characteristics from those of Sweden. Present specification does not deal with geographical agglomeration of innovative establishments or their persistence over time since these aspects are difficult to take into account in the context of panel data with a censored dependent variable. Another interesting aspect is how establishments are affiliated and to what extent they are active in the international market. Unfortunately, this information is not available in the dataset at hand. Any long-term effects of the Covid-19 pandemic cannot yet be identified. If, for instance, there are net flows of individuals moving away from larger to smaller cities, firms and establishments might follow this development to areas where their needs for skills and infrastructure can be guaranteed. This is for future research to investigate.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the participants in the CAED Conference in Coimbra, November 2021, Portugal, the NEON Conference, November 2022, in Drammen, Norway, the IØSS research seminar, March 2023, USN Kongsberg, Norway as well as the Conference on Institutions, Knowledge Diffusion and Economic Development, September 2023, at the University of Cagliari, Italy, for helpful comments on earlier versions of this study. A similar recognition goes to the delegates to the OECD Working Party on Territorial Indicators, May 2022, in Paris, France.

Disclaimer

The conclusions drawn in this study are those of the authors and should not be confused with any official views held by their institutions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement:

Data on the number of establishments is confidential and cannot be shared.

Notes

1 https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/policies/broadband-support, accessed 1 June 2023.

2 https://www.scb.se/vara-tjanster/bestall-data-och-statistik/foretagsregistret/variabelbeskrivning, accessed 1 June 2023.

3 https://tillvaxtverket.se/tillvaxtverket/statistikochanalys/statistikverktyg/regionaltanalysochprognossystemraps.3360.html, retrieved 1 June 2023.

4 Source: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Glossary:High-tech_classification_of_manufacturing_industries, and https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Glossary:Knowledge-intensive_services_(KIS) accessed 1 June 2023.

5 https://www.statistikdatabasen.scb.se/pxweb/en/ssd/START__BE__BE0101__BE0101A/BefolkningNy, retrieved 1 June 2023; https://www.statistikdatabasen.scb.se/pxweb/sv/ssd/START__UF__UF0506__UF0506B/Utbildning, retrieved 1 June 2023.

6 https://statistik.pts.se/mobiltackning-och-bredband, retrieved 1 June 2023.

7 https://kommuninvest.se/investerarinformation/upplaning-och-upplaningsbehov/statistik, retrieved 1 June 2023.

References

- Abrardi, L., & Cambini, C. (2019). Ultra-fast broadband investment and adoption: A survey. Telecommunications Policy, 43(3), 183–198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.telpol.2019.02.005

- Ahlfeldt, G., Koutroumpis, P., & Valletti, T. (2017). Speed 2.0: Evaluating access to universal digital highways. Journal of the European Economic Association, 15(3), 586–625. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeea/jvw013

- Alderete, M. V. (2017). Examining the ICT access effect on socioeconomic development: The moderating role of ICT use and skills. Information Technology for Development, 23(1), 42–58. https://doi.org/10.1080/02681102.2016.1238807

- Andrews, D., Criscuolo, C., & Gal, P. N. (2015). Frontier firms, technology diffusion and public policy: Micro evidence from OECD countries, OECD productivity working papers, 2015-02, OECD Publishing, Paris. https://doi.org/10.1787/5jrql2q2jj7b-en.

- Arauzo-Carod, J. M., Liviano-Solis, D., & Manjón-Antolín, M. (2010). Empirical studies in industrial location: an assessment of their methods and results*. Journal of Regional Science, 50(3), 685–711. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9787.2009.00625.x

- Armington, C., & Acs, Z. J. (2002). The determinants of regional variation in new firm formation. Regional Studies, 36(1), 33–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343400120099843

- Atasoy, H. (2013). The effects of broadband internet expansion on labor market outcomes. ILR Review, 66(2), 315–345. https://doi.org/10.1177/001979391306600202

- Audretsch, D. B., & Feldman, M. P. (1996). R&D spillovers and the geography of innovation and production. The American Economic Review, 86(3), 630–640. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2118216

- Audretsch, D. B., & Feldman, M. P. (2004). Handbook of regional and urban economics. In: Handbook of Regional and Urban Economics, 4, 2713–2739. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1574-0080(04)80018-X

- Audretsch, D. B., Heger, D., & Veith, T. (2015). Infrastructure and entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics, 44(2), 219–230. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-014-9600-6

- Audretsch, D. B., Lehmann, E. E., & Warning, S. (2005). University spillovers and new firm location. Research Policy, 34(7), 1113–1122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2005.05.009

- Bartelsman, E., Haltiwanger, J., & Scarpetta, S. (2013). Cross-country differences in productivity: The role of allocation and selection. American Economic Review, 103(1), 305–334. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.103.1.305

- Bennett, D. L. (2019). Infrastructure investments and entrepreneurial dynamism in the U.S. Journal of Business Venturing, 34(5), 105907. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2018.10.005

- Bertanha, M., & Moser, P. (2016). Spatial errors in count data regressions. Journal of Econometric Methods, 5(1), 49–69. https://doi.org/10.1515/jem-2014-0015

- Bertschek, I., Briglauer, W., Hüschelrath, K., Kauf, B., & Niebel, T. (2015). The economic impacts of broadband internet: A survey. Review of Network Economics, 14(4), 201–227. https://doi.org/10.1515/rne-2016-0032

- Bhat, C. R., Paleti, R., & Singh, P. (2014). A spatial multivariate count model for firm location decisions. Journal of Regional Science, 54(3), 462–502. https://doi.org/10.1111/jors.12101

- Bondonio, D., & Greenbaum, R. T. (2006). Do business investment incentives promote employment in declining areas? Evidence from EU objective-2 regions. European Urban and Regional Studies, 13(3), 225–244. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969776406065432

- Boschma, R., Eriksson, R., & Lindgren, U. (2008). How does labour mobility affect the performance of plants? The importance of relatedness and geographical proximity. Journal of Economic Geography, 9(2), 169–190. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbn041

- Briglauer, W., Dürr, N., & Gugler, K. (2021). A retrospective study on the regional benefits and spillover effects of high-speed broadband networks: Evidence from German counties. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 74, 102677. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijindorg.2020.102677

- Canzian, G., Poy, S., & Schüller, S. (2019). Broadband upgrade and firm performance in rural areas: Quasi-experimental evidence. Regional Science and Urban Economics, 77, 87–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.regsciurbeco.2019.03.002

- Capello, R., & Cerisola, S. (2021). Catching-up and regional disparities: A resource-allocation approach. European Planning Studies, 29(1), 94–116. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2020.1823323

- Capello, R., & Lenzi, C. (2015). Knowledge, innovation and productivity gains across European regions. Regional Studies, 49(11), 1788–1804. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2014.917167

- Capello, R., & Lenzi, C. (2018). Regional innovation patterns from an evolutionary perspective. Regional Studies, 52(2), 159–171. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2017.1296943

- Conroy, T., & Low, S. A. (2022). Entrepreneurship, broadband, and gender: Evidence from establishment births in rural America. International Regional Science Review, 45(1), 3–35. https://doi.org/10.1177/01600176211018749

- Das, S., & Chatterjee, A. (2023). Impacts of ICT and digital finance on poverty and income inequality: A sub-national study from India. Information Technology for Development, 378–405. https://doi.org/10.1080/02681102.2022.2151556

- Delfmann, H., Koster, S., McCann, P., & Van Dijk, J. (2014). Population change and new firm formation in urban and rural regions. Regional Studies, 48(6), 1034–1050. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2013.867430

- Deller, S., Whitacre, B., & Conroy, T. (2022). Rural broadband speeds and business startup rates. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 104(3), 999–1025. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajae.12259

- Dingel, J. I., & Neiman, B. (2020). How many jobs can be done at home? Journal of Public Economics, 189, 104235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104235

- Duvivier, C. (2019). Broadband and firm location: Some answers to relevant policy and research issues using meta-analysis. Canadian Journal of Regional Science, 42(1), 24–45. https://doi.org/10.7202/1083638ar

- Duvivier, C., & Bussière, C. (2022). The contingent nature of broadband as an engine for business startups in rural areas. Journal of Regional Science, 62(5), 1329–1357. https://doi.org/10.1111/jors.12605

- Duvivier, C., Cazou, E., Truchet-Aznar, S., Brunelle, C., & Dubé, J. (2021). When, where, and for what industries does broadband foster establishment births? Papers in Regional Science, 100(6), 1377–1401. https://doi.org/10.1111/pirs.12626

- Falk, M., & Hagsten, E. (2021). Impact of high-speed broadband access on local establishment dynamics. Telecommunications Policy, 45(4), 102104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.telpol.2021.102104

- Flaminiano, J. P. C., Francisco, J. P. S., & Alcantara, S. T. S. (2022). Information technology as a catalyst to the effects of education on labor productivity. Information Technology for Development, 28(4), 797–815. https://doi.org/10.1080/02681102.2021.2008851

- Haefner, L., & Sternberg, R. (2020). Spatial implications of digitization: State of the field and research agenda. Geography Compass, 14(12), e12544. https://doi.org/10.1111/gec3.12544

- Halleck Vega, H., & Elhorst, P. (2015). The SLX model. Journal of Regional Science, 55(3), 339–363. https://doi.org/10.1111/jors.12188

- Haller, S. A., & Lyons, S. (2019). Effects of broadband availability on total factor productivity in service sector firms: Evidence from Ireland. Telecommunications Policy, 43(1), 11–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.telpol.2018.09.005

- Harris, R. (2011). Models of regional growth: Past, present and future. Journal of Economic Surveys, 25(5), 913–951. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6419.2010.00630.x

- Hasbi, M. (2020). Impact of very high-speed broadband on company creation and entrepreneurship: Empirical evidence. Telecommunications Policy, 44(3), 101873. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.telpol.2019.101873

- Hasbi, M., & Bohlin, E. (2022). Impact of broadband quality on median income and unemployment: Evidence from Sweden. Telematics and Informatics, 66, 101732. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2021.101732

- Holl, A. (2004). Start-ups and relocations: Manufacturing plant location in Portugal*. Papers in Regional Science, 83(4), 649–668. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1435-5597.2004.tb01932.x

- Jaffe, A. B., Trajtenberg, M., & Henderson, R. (1993). Geographic localization of knowledge spillovers as evidenced by patent citations. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 108(3), 577–598. https://doi.org/10.2307/2118401

- Jung, J., & López-Bazo, E. (2020). On the regional impact of broadband on productivity: The case of Brazil. Telecommunications Policy, 44(1), 101826. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.telpol.2019.05.002

- Kartiasih, F., Djalal Nachrowi, N., Wisana, I. D. G. K., & Handayani, D. (2023). Inequalities of Indonesia’s regional digital development and its association with socioeconomic characteristics: a spatial and multivariate analysis. Information Technology for Development, 299-328. https://doi.org/10.1080/02681102.2022.2110556.

- Kim, Y., & Orazem, P. F. (2017). Broadband internet and new firm location decisions in rural areas. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 99(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajae/aaw082

- Kondo, K. (2015). spgen: Stata module to generate spatially lagged variables. Statistical Software Components S458105, Department of Economics, Boston College. https://ideas.repec.org/c/boc/bocode/s458105.html

- Kraus, S., Jones, P., Kailer, N., Weinmann, A., Chaparro-Banegas, N., & Roig-Tierno, N. (2021). Digital transformation: An overview of the current state of the art of research. Sage Open, 11(3), 215824402110475. https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440211047576

- Lehtonen, O. (2020). Population grid-based assessment of the impact of broadband expansion on population development in rural areas. Telecommunications Policy, 44(10), 102028. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.telpol.2020.102028

- Lin, W., & Wooldridge, J. M. (2019). Testing and correcting for endogeneity in nonlinear unobserved effects models. In M. Tsionas (Ed.), Panel data econometrics: empirical applications (pp. 21–43). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-814367-4.00002-2.

- Liviano, D., & Arauzo-Carod, J. M. (2014). Industrial location and spatial dependence: An empirical application. Regional Studies, 48(4), 727–743. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2012.675054

- Mack, E. A. (2014). Businesses and the need for speed: The impact of broadband speed on business presence. Telematics and Informatics, 31(4), 617–627. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2013.12.001

- Mack, E. A., & Wentz, E. (2017). Industry variations in the broadband business nexus. Socio-Economic Planning Sciences, 58, 51–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seps.2016.10.007

- Mayer, W., Madden, G., & Wu, C. (2020). Broadband and economic growth: A reassessment. Information Technology for Development, 26(1), 128–145. https://doi.org/10.1080/02681102.2019.1586631

- McCann, P., & Simonen, J. (2005). Innovation, knowledge spillovers and local labour markets. Papers in Regional Science, 84(3), 465–485. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1435-5957.2005.00036.x

- McCoy, D., Lyons, S., Morgenroth, E., Palcic, D., & Allen, L. (2018). The impact of broadband and other infrastructure on the location of new business establishments. Journal of Regional Science, 58(3), 509–534. https://doi.org/10.1111/jors.12376

- Naldi, L., Nilsson, P., Westlund, H., & Wixe, S. (2021). Amenities and new firm formation in rural areas. Journal of Rural Studies, 85, 32–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2021.05.023

- Öner, Ö. (2017). Retail city: The relationship between place attractiveness and accessibility to shops. Spatial Economic Analysis, 12(1), 72–91. https://doi.org/10.1080/17421772.2017.1265663

- Parajuli, J., & Haynes, K. (2017). Spatial heterogeneity, broadband, and New firm formation. Quality Innovation Prosperity, 21(1), 165–185. https://doi.org/10.12776/qip.v20i3.791

- Pekkala, S. (2003). Migration flows in Finland: Regional differences in migration determinants and migrant types. International Regional Science Review, 26(4), 466–482. https://doi.org/10.1177/0160017603259861

- Sarachuk, K., Missler-Behr, M., & Hellebrand, A. (2021). Ultra high-speed broadband internet and firm creation in Germany. In D. Rodionov, T. Kudryavtseva, A. Skhvediani, & M. A. Berawi (Eds.), Innovations in digital economy. SPBPU IDE 2020. Communications in computer and information science (Vol. 1445, pp. 40–56). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-84845-3_3.

- Smidt, H. J. (2022). Factors affecting digital technology adoption by small-scale farmers in agriculture value chains (AVCs) in South Africa. Information Technology for Development, 28(3), 558–584. https://doi.org/10.1080/02681102.2021.1975256

- Stephens, H. M., Mack, E. A., & Mann, J. (2022). Broadband and entrepreneurship: An empirical assessment of the connection between broadband availability and new business activity across the United States. Telematics and Informatics, 74, 101873. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2022.101873

- Sternberg, R. (2022). Entrepreneurship and geography—some thoughts about a complex relationship. The Annals of Regional Science, 69(3), 559–584. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00168-021-01091-w

- Tranos, E., & Gillespie, A. (2009). The spatial distribution of internet backbone networks in Europe. European Urban and Regional Studies, 16(4), 423–437. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969776409340866

- Tranos, E., & Mack, E. A. (2016). Broadband provision and knowledge-intensive firms: A causal relationship? Regional Studies, 50(7), 1113–1126. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2014.965136

- Verhoef, P. C., Broekhuizen, T., Bart, Y., Bhattacharya, A., Dong, J. Q., Fabian, N., & Haenlein, M. (2021). Digital transformation: A multidisciplinary reflection and research agenda. Journal of Business Research, 122, 889–901. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.09.022

- Vial, G. (2019). Understanding digital transformation: A review and a research agenda. The Journal of Strategic Information Systems, 28(2), 118–144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsis.2019.01.003

- Whitacre, B., Gallardo, R., & Strover, S. (2014). Does rural broadband impact jobs and income? Evidence from spatial and first-differenced regressions. The Annals of Regional Science, 53(3), 649–670. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00168-014-0637-x

- Wooldridge, J. M. (1999). Distribution-free estimation of some nonlinear panel data models. Journal of Econometrics, 90(1), 77–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-4076(98)00033-5