ABSTRACT

The global digital divide is sometime presented as the primary obstacle to developmental convergence between world regions. On the other hand mobile phone and internet technology are at times seen as transformative innovations that are dissolving this development divide. Through secondary data (such as on usage from Internet World Stats) and case exemplars, of mobile money and the gig economy, this paper argues that this is not the case; primarily because new information and communication technologies are used mostly for communication and consumption, rather than production, and if they are value capture is often low. Consequently the ‘digital divide’, and its partial dissolution, are perhaps better characterized as phases of an ‘ICT product consumption diffusion cycle’, facilitated by technological embedding and convergence. The paper provides background and substantiates this argument and then explores the potential for a deep digital transformation (DDT) in the Global South.

1. Introduction

‘How does access to information technology impact development?’ is perhaps one of the most important questions in the field of international development. According to some commentators the ‘digital divide’,Footnote1 where there are dramatic differences in access to, and use of, information technology was, or is, a primary cause of underdevelopment, with the US Secretary of State at the start of the new millennium going so far as to call it ‘digital apartheid’ (Powell quoted in Koss, Citation2001, p. 81). However, with substantial increases in the availability of low-cost smartphones, and associated digital applications, in many parts of the Global South some analysts have argued users there are more included, reap benefits and contribute to the structural transformation of economies.Footnote2 However research results are mixed, with one comprehensive study of low and middle-income countries finding that ‘digitalization has a positive impact on structural change and manufacturing labour productivity but a negative impact on manufacturing employment share, indicating a reallocation of labor from the agricultural sector into services’ (Banga et al., Citation2023). Of course whether such a trend can be considered a ‘positive’ structural change is open to question as manufacturing development remains the main route out of poverty for developing countries through employment creation, linkage, multiplier and research, and development effects, amongst others (see Carmody et al., Citation2023).

According to the well-known development economist Jeffrey Sachs ‘mobile phones are the single most transformative technology for development’ (quoted in Voigt, Citation2011, np). Other researchers echo this sentiment with Wani and Ali (Citation2015, p. 101) claiming ‘when mobile phones were introduced in the world markets, little did one expect that these small handheld devices would transform the world as we knew it’. However, as Harvey (Citation2003) reminds us technology in and of itself does not have causative power. Heeks et al. (Citation2023, p. 21) in their systematic review argue that

(T)he heavy lean of current literature towards optimism and techno-centrism suggest that research has been a little too taken up with the hype of digital transformation when it is clear that DX4D [digital transformation for development] is still at best an emergent phenomenon.

Paradoxically however perhaps, according to some sources, users in developing countries often now tend to spend, on average, more time on the internet than those in the Global North.

In 2022 … the country that spent the longest online was South Africa, where residents surfed the Internet for an average of 578 minutes (9 hours and 38 minutes) every day. Brazil and the Philippines rounded out the top three with 572 minutes (9 hours and 32 minutes) and 554 minutes (9 hours and 14 minutes), respectively. (Government Technology, Citation2023)Footnote3

Is this then a revolutionary moment when the development divide is erased? This is not the case, primarily because new information and communication technologies (ICTs) are used mostly for the consumption of content, rather than economic production. As Arora (Citation2019, p. 18) notes ‘people who have fewer resources, who often have unsteady, badly paid, or no employment, seek ways to cope with their vast amount of free time – and mobile phones give them this primarily by providing them with entertainment’. Recent trends bely ICT boosterist claims; as these largely reflect deeper market and unpaid labor (data, content) exploitation rather than being representative of a fundamental economic, structural transformation (Kwet, Citation2019). Furthermore, data and content exploitation is classed, as the greatest burden of surveillance using digital methods has always been borne by the poor; such as through attempts to avoid welfare fraud for example (Eubanks, Citation2014 and Masiero, Citation2016 cited in Taylor, Citation2017). In fact, the appearance of the ‘digital divide’, and its partial dissolution, are more accurately characterized as phases of ‘the ICT product consumption diffusion cycle’ (PCDC) (discussed later), which has been facilitated by technological convergence. Consumption rather than production uses are the primary drivers of this.

This paper draws on data from a variety of sources and agencies, such as from the World Bank, and evidence from the use of mobile applications often thought to be particularly well suited to address needs in the Global South: mobile money and gig economy work. It begins by exploring the digital divide and its partial dissolution. It then examines particular uses of digital technology in the Global South and develops the theory of the PCDC. Finally, it concludes by examining policy implications from the findings and explores the wider developmental potential of the technology.

2. The digital divide

‘The term “digital divide” emerged in the 1990s in the United States to describe observed inequalities of access, initially, to computers and later to the Internet, information, and other digital technologies’ (Hartnett, Citation2019, np). The literature on this phenomenon usually assumes that benefits of the internet accrue primarily to developed rather than developing countries (Jaumotte et al., Citation2007). In a sense this should not be a surprise as this suite technologies are often largely designed in the Global North, and for its conditions, including relatively high income levels. Consequently, data shows a substantial divide between the adoption and use of the internet globally. For example, internet penetration in North America is 93% and 89% in Europe, but in Africa is only 43%, with the majority there accessing it via their mobile phones (Internet World Stats, Citation2023). However given the rapid rate of increase in internet usage – in Africa it grew 13,233% from 2000 to 2023 – this gap is closing rapidly with the Global North (Internet World Stats, Citation2023), even as new digital divides, around geo-tagged data for example, are opening in terms of usage (see Graham, Citation2008).

Mobile phones are a somewhat unusual, advanced technology, as in some cases they have been more heavily adopted in the Global South than the North, which can partially be explained by leapfrogging, where new adopters bypass obsolete technologies leading to cost and other efficiencies, and also as a result of generally declining prices for handsets. As new ICTs dropped in cost and consequently became more widely adopted across the globe, some posited a ‘digital provide’ in the Global South, where they could be used to enhance direct producers’ livelihoods and returns to labor through disintermediation (cutting out of ‘middle people’) (see Jensen, Citation2007).

At a time of unprecedented global micro-electronic and digital technological revolution, it was perhaps unsurprising that some commentators came to see differential access to new ICTs as the primary driver of underdevelopment, which could be reversed. However correlation does not equal causation and the overall developmental impacts have been relatively limited as these are primarily used as communication and consumption, rather than production, technologies (Carmody, Citation2012, Citation2013). Consequently, digital adoption has not fundamentally altered the broader development divide. The paper now explores why this is the case in more detail.

3. Digital and development divide dissolution?

As noted earlier, such has been the scale of diffusion of mobile phones recently some surveys suggest that those in the Global South spend, on average, more time on the Internet. For example, whereas European users spend an average of 1 h and 53 min a day on social media, the figure for South America is 3 h and 29 min (Review 42, Citation2023), leading some to suggest there has been a global ‘digital reversal’ (James, Citation2021). However, users in both the Global South, and also to a large extent the Global North, prioritize social and entertainment uses (Arora, Citation2019; Jeffrey, Citation2010; Malm & Toyama, Citation2021) rather than those for business, which could theoretically lead to productivity increases or spark innovation. This is in keeping with Banerjee and Duflo’s (Citation2012) finding that for some of the poor ‘television is more important than food’ given the hardships of their existence. Online advertising is also heavy and dominated by transnational corporations as they attempt to ‘consumerize’ the poor (Innovate Media, Citation2020; Murphy & Carmody, Citation2015).

The poverty reduction benefits of mobile phones are consequently often over-stated (see Carmody, Citation2012 and Bateman et al., Citation2019). Malm and Toyama (Citation2021) find in their study that only a relatively small minority of ‘deliberate’ or ‘advanced’ users of mobile phones benefit from them financially, whereas ‘simple’ users may merely experience their (economic) costs. However, for ‘purposeful’ users there is evidence of intense entrepreneurship, adaptation and innovation (Afutu-Kotey & Gough, Citation2022; Meagher, Citation2018) but as implied above, new and general adopters often choose a more ‘shallow’ pattern of uses than theoretically might be expected through the lens of developmentality (Lie, Citation2015; Wang, Citation2020, np).

The above is not suggestive of a deep digital transformation (DDT) of economic structures (explored in more detail below) in the Global South. This potential loss is felt at the level of the domestic economy and represents a form of ‘thin integration’ (thintegration) (Carmody, Citation2013) into the global informational economy and society in the sense that many domestic economies in the Global South are only relatively superficially integrated. For example, there are often only limited research and development and supply chain interactions with that global economy, which prevent the development of linkage, spillover, multiplier and accelerator effects in domestic ones, although they may be critical suppliers of raw materials (Kara, Citation2023). While some countries have been able to attract substantial economic activity in this space, such as call-centres in the Philippines, this is often without accompanying economic transformation (Kleibert & Mann, Citation2020), but with declining gains from foreign investment (Mann, Citation2023).

While the digital divide and subsequent (partial) dissolution are real, they are better conceived of as a singular process (product consumption diffusion) rather than separate ones. This process is reflective of both deeper development divides, as expressed initially through cost constraints, and the phenomenon of technological convergence in mobile phones, where they also serve other functions similar to watches, torches, computers and others. These twin processes of division and diffusion can then be conceptualized as the ICT ‘product diffusion consumption cycle’. Understanding this allows for a more realistic understanding of the developmental potential of new ICTs in the Global South. How does this cycle work?

4. Understanding the new ICT product diffusion consumption cycle

Perhaps the main theory around the spread of new innovations is the S-shaped diffusion curve proposed by Rogers (Citation2003), which posited slower and then more rapid adoption of new technologies before saturation and plateauing out, although there are also competing theories of innovation diffusion (see Wani & Ali, Citation2015). As noted above however the experience with mobile phones has been different to that proposed by Rogers as they have not become obsolete but continue to increase their global diffusion. How do we explain this?

In the 1960s Vernon (Citation1966) developed product cycle theory, which aimed to explain the changing geography of production as new products moved through their life cycle. In essence, when new innovative products emerged in rich countries, economic rents were high and could support higher wages in those contexts. As the technology became more embedded and diffused, rents dissipated and production spread to low-wage contexts until eventual obsolescence. While this theory captured important aspects of the emergent geography and shifts in global production, although not without its problems (see Storper, Citation1985), it did not explicitly deal with the geography of consumption, which recursively affects the geography of production through effective demand.

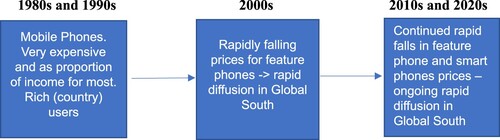

In order to explain the diffusion and profusion of mobile phones in the Global South this paper proposes a PCDC. This theory as it relates to mobile phone in particular is illustrated in .

In 1983 one of the first mobile phones, the Motorola Dyna TAC cost almost US $4,000 (Peng, Citation2019) but as prices for handsets fell rapidly in recent decades mobile phones have become affordable for most people around the world.Footnote4 However as data costs are the highest in the world in Africa for example, with one gigabit of data, according to some estimates, costing US $50 in Equatorial Guinea (the highest in the world), versus US $0.05 in Israel (the cheapest in the world) (WEF, Citation2022), people often have to find innovative ways of using their phones to save money or access ‘free’ services through initiatives such as ‘Facebook Zero’.Footnote5 High data costs represent a major disincentive for productive use of the internet. For example, Africa has 5.2% of registered workers globally on the Upwork ‘gig’ platform, which is, however, less than the Philippines by itself (Anwar & Graham, Citation2022).

Obsolescence has been avoided to-date in the case of mobile phones because (1) these are relatively recent innovations, (2) their small size and now often relatively low cost and (3) the phenomenon of technological convergence noted above which has enhanced their utility. Adoption is not necessarily synonymous with economic development though as the paper now explores through a case exemplar of one of the most frequently touted innovations: mobile money.

5. Mobile money

There are many potential channels through which ICT can contribute to economic development. In the literature disintermediation or the cutting out of middle ‘men’ has received much attention. However disintermediation may offer only marginal gains from an economy-wide perspective, without changing production structures or increasing productivity, and mobile phones may be implicated in new forms of extractive intermediation (see Molony, Citation2007; Murphy & Carmody, Citation2015) via websites and platforms for example. Another area which has received much attention is mobile money.

Within Africa the best-known mobile money application is called M-Pesa (pesa is money in Swahili), which is an electronic payment and money storage system. Ninety-six percent of households in Kenya had at least one individual who used M-Pesa by 2016 and there is now an over 90% penetration rateFootnote6 for the application in that country (Gathinji quoted in Talking Banking Matters, Citation2022). Mobile phones are used to make payments or get cash from agents. This of course may be very useful and time-saving, but not economically transformative as it does not substantially raise the productivity of different economic sectors. New ICTs are also characterized by a productivity paradox, where surfing the internet or transferring money, for example, may distract from working (Vass, Citation2018). Furthermore, M-Pesa has been associated with substantial value transfer overseas to its primary parent company in the UK, Vodafone, for intellectual property rights service fees (Foster, Citation2023).

The introduction of new ICTs and other related innovations have also been associated with forms of displacement, with substantial governance implications and impact. For example although rapid adoption of mobile payments such as M-Pesa led to the loss of roughly 6,000 bank jobs between 2014 and 2017 in Kenya the number of mobile payment agents increased by almost 70,000, resulting in a direct net positive job effect. (Choi et al., Citation2020, p. 1)

However, this positive analysis elides a number of issues. Firstly, the displaced jobs were in the formal sector, whereas those created were not. This means a potential loss of income tax revenue and the further dilution of the social contract with citizens; the lack of which is largely responsible for many African countries’ governance problems (Leonard & Straus, Citation2003). Furthermore, agents are now being largely displaced by digital systems of topping up (Afutu-Kotey & Gough, Citation2022).

There are however many potential economic benefits of mobile money. For example, Shema (Citation2019) shows how credit scoring and then, potentially, access to loans is facilitated by analysis of mobile phone data usage. Gosavi (Citation2018) shows East African firms using mobile money are more productive and more likely to get loans or credit, although the evidence presented is associative rather than demonstrating causality. However, adoption may also result in the competitive displacement of some small businesses by mobile phone or internet-enabled micro-enterprises. Furthermore, better access to credit sometimes results in increasing indebtedness and gambling (Bateman et al., Citation2019). Evidence does however exist indicating increased tax receipts after the introduction of mobile money payment systems (Apeti & Edoh, Citation2023; Scharwat, Citation2014).

Despite its promise, however, the actual economic gains from mobile money are still being debated in terms of differences in data and method. Nonetheless

A growing body of research is emerging with a consistent finding: households are able to better respond to unforeseen difficulties when they have access to mobile money … This is because mobile money helps risk-sharing among the community or family irrespective of location, strengthening these informal insurance networks. (Parekh & Hare, Citation2020, np)

This however is not transformative of economic structures. Does the internet perhaps offer greater developmental potential?

6. Gigification, virtual capital and thintegration

The increasing social penetration and geographic diffusion of digital technologies have also opened up the possibility of new business models, and reconfigurations of social and employment relations. In particular, it has facilitated the development of the so-called gig economy or ‘gigification’ (Veen et al., Citation2020) where delivery service workers or ‘ride sharers’, for example, are effectively paid a piece rate to undertake a discrete piece of work (Anwar & Graham, Citation2020). This has allowed for the emergence of a new form of capital – virtual capital, which is defined by the fact it ‘extracts’ value from assets it doesn’t own and labor it doesn’t manage (Carmody & Fortuin, Citation2019).

While there are examples of virtual capital which are African-originating, such as the online retail, delivery company and financial payments company Jumia, which is a ‘unicorn’,Footnote7 most virtual capital in the Global South tends to be foreign in origin, resulting in the expatriation of profits which could otherwise be domestically or regionally invested if produced by local firms, representing a reconfiguration rather than a transcendence of dependence. Furthermore, even locally-owned online retail companies source many of their products overseas; again representing a value transfer abroad as the profits and wages associated with production are captured off-shore.

Despite its iconic status Jumia itself has struggled, partly as a result of competition from (foreign-owned) social media marketplaces (Komminoth, Citation2023). In 2019 ‘Jumia’s losses rose 34% to $246 m, the eighth straight year without profits’ (BBC, Citation2020, np) and its stock price on the New York Stock Exchange collapsed. It then closed operations in three African countries, reflective of its challenging operating environments.Footnote8 Also

Jumia’s public claim to African-ness is tenuous because its headquarters are in Berlin, Germany, its Technology and Product Team in Porto, Portugal, and its senior leadership in Dubai in the United Arab Emirates (UAE). Critics see it as an exploitative Western company that conveniently co-opted an African identity to extract as much value as possible and profit off the continent. (BBC, Citation2020, np)

ICTs allow foreign firms, such as Uber, to break down spatial barriers to accumulation globally, sometimes in the informal sector (Meagher, Citation2018).Footnote9 ‘Virtual capital’ governs through mobile applications and customer surveillance (ratings), globally (Carmody & Fortuin, Citation2019). While applications such as Uber may help fill insitutional voids, this is not always positive and they are also implicated in void creation, where there are missing intermediaries or other functions vital to effective market functioning (Heeks et al., Citation2021).

According to some it is the ‘gig’ and informal economies which are the future of Africa (e.g. Adegoke, Citation2018; Ng’weno & Porteous, Citation2018). This can be seen as related to the ‘Africa Rising’ discourse. However, for many, it may be a dystopian future. For example, according to Choi et al. (Citation2020, p. xix).

Kobo360 and Lori Systems have each invested in cashless, paperless, mobile-based on-demand trucking logistics technologies that have created new and better functioning markets. Mobile technologies are allowing young entrepreneurs to use various digital platforms to access larger markets. Of course, the risk of large sections of the poor, the low-skilled, and the uneducated being left behind in a so-called digital divide looms large as more than 60 percent of the labor force is made up of ill-equipped adults and almost 90 percent of employment is in the informal sector.

The fact that only around 10% of African gross domestic product (GDP) is produced by the manufacturing sector is presented by Choi et al. (Citation2020) in their World Bank study as an advantage, as it is argued that competitive displacement of labor by robotics and other technologies of the fourth industrial revolution will be less pronounced than that in other world regions. However, existing marginalization may simply recursively deepen as rates of investment remain low.

In South Africa, generally taken to be the most industrially advanced country on the continent, investment as a proportion of GDP fell from over 34% in 1981 to less than 19% in 2017 (World Bank, Citation2021), despite the purported ‘Africa Rising’ phenomenon (Carmody et al., Citation2020). Gross capital formation for Sub-Saharan Africa was 22% in 2019, compared to 44% in 1981 – a halving (World Bank, Citation2021).Footnote10 This decline in the relative level of investment is reflective of the ‘autonomous’ development of the trade and financial sectors on the continent and associated capital leakages through imports and (often illicit) financial flows (Carmody, Citation1998), now increasingly facilitated through ICTs (Steel, Citation2021). This has made it virtually impossible for the sub-continent to move from factor-driven to investment and innovation-driven growth, claims to the contrary notwithstanding. Consequently, while Africa is increasingly an information society it is not a knowledge economy (Carmody, Citation2013). How can new ICTs be used more developmentally?

7. The internet and digital upskilling

In most cases, to date, digital diffusion in the Global South has not been economically transformative; at least where hardware and software or more advanced associated services are not produced. In order to be transformative there has to be substantial value creation and capture domestically.Footnote11 This would imply developing production capacity initially in industries that are relatively low technology and skill, that are resistant to automation, such as clothing for the time being at least (Altenburg et al., Citation2020) and moving up the value chain or down the technology stack to engage in research and development through time. It may also be possible to ‘leapfrog’ into new industries and technologies, particularly in those which have short technology cycle times rather than long periods of research and development (Lee, Citation2024). Through time it might also imply the development of platform companies, but as has been demonstrated the hold of incumbents in global markets is strong, implying the need for digital industrial policy to develop conducive ecosystems where there are positive feedback signals, incentives, returns and loops.

If such an approach is adopted there is potential for a DDT where ICTs promote structural transformation. This will have three dimensions: (1) training, upskilling and associated impacts, (2) integration into the production of goods and services that increase productivity, (3) research, development and production of ICTs, which is often currently beyond most low-income countries technological capabilities, but may be developed or imported through foreign direct investment (FDI) or through joint ventures. For example the Mara group, originally from Tanzania but now headquartered in the United Arab Emirates, produces smart phones in Rwanda in partnership with Google (Tasamba, Citation2019). The focus in this section is on the first of these three aspects – digital skills – as this would appear to be the ‘lowest hanging fruit’ and the COVID pandemic showed their vital importance to the continued operation of economies and services (Gigler, Citation2021).

Thicker or deeper integration of new ICTs is associated with improvements in productivity and firm competitiveness (see Murphy & Carmody, Citation2015). This requires digital skills, which are scarce in much of Africa and much of the Global South more generally (Qureshi, Citation2023), especially in ‘remote’ rural areas. Lack of digital skills is both a symptom and recursive cause of underdevelopment but their provision by themselves will not close development divides (Chetty et al., Citation2018) in the absence of wider structural and productivity changes. Nonetheless, they are a necessary prerequisite to a DDT; although skills are only one amongst many barriers to technological adoption and effective usage (see Boamah et al., Citation2021), such as reliable power supply. Skills gaps will potentially reduce both FDI in this area and domestic firm formation and survival, although the role of aggregate domestic demand is central in this (Cramer et al., Citation2020). Skills training, by itself, however, in the absence of effective demand creation, perhaps local content requirements and other elements of industrial policy and supportive regulatory frameworks will be ineffective (Greene, Citation2021). These should be developed along with other elements of industrial policy in a joined-up approach (Foster & Azmeh, Citation2023).

According to Caballero and Bashir (Citation2020) hundreds of millions of people in Africa will need training or retraining in digital skills, with the International Finance Corporation estimating that 230 million jobs on the continent will require these by 2030 (IFC, Citation2019). If the past is prologue however it is unlikely this demand will be met, although we should perhaps be wary that projected skills demand will materialize given pervasive and often unfounded digital boosterism (Bateman et al., Citation2019). Nonetheless, there does appear to be a skills gap and only 50% of African countries have computer skills in the school curriculum compared to the global average of 85% (Kandri, Citation2019). In some cases, companies are already reacting to the lack of digitally-skilled labor by recruiting from overseasFootnote12 (IFC, Citation2019). However, this does little to build local digital capabilities or ecosystems. Stand-alone initiatives isolated from the local context, such as telecentres, have often failed in the past. Consequently, Gigler (Citation2021, np) argues that there is a need to ‘fully integrate digital development programs in the overall objectives of sectoral programs such as in education, health, agriculture and avoid implementing digital programs as stand-alone projects’.

Currently, predominant uses of the internet such as entertainment and gambling may induce a moral panic in those who are wealthier (Arora, Citation2019) or ‘donors’ seeking to reduce the digital divide. While such paternalism may be regrettable there is still an economic case for educational reform and for interventions that produce a ‘thicker’, more developmental role for the internet and other new ICTs. This is not to suggest that governments in the Global South force people to use these in certain ways, but that they can shape incentives around them to be more developmental. Aid may play an important catalytic financing role in this effort.

8. Conclusion: towards a deep digital transformation

There is increasing recognition in the literature, since 2017 when the first paper was published on it (Heeks et al., Citation2023), of the need for digital transformation. Various three-stage models of this have been proposed such as those encompassing access, proficiency and benefits (Haryanti et al., Citation2023 cited in Heeks et al., Citation2023) and foundation, adoption and acceleration (Kim et al., Citation2022 cited in Heeks et al., Citation2023). Others argue that digital transformation must entail structural change.

As Gerschenkron (Citation1962) wrote more than a half-century ago economic backwardness may create certain advantages. In particular, it may allow for technological leapfrogging and low wages may be leveraged as a source of competitive advantage if labor productivity gaps with more advanced or industrializing economies can be reduced or closed. However, these potential advantages are only latent and can only be actualized in the current hyper-competitive financialized and digitalized economy in the context of an effective and articulated industrial strategy. At the moment most of Africa is experiencing adverse, differential (Bush, Citation2007)Footnote13 and digitalized (re)incorporation and restructuring into the global economy (see also Heeks, Citation2022); claims of ‘Africa Rising’ notwithstanding. Mobile phone penetration or increased internet connectivity by themselves do little to enhance economic productivity or structural transformation, despite the existence of ‘economies of time’ associated with these technologies. On the contrary, as most ICT is imported into Africa and profits tend to flow outwards through imports and to service providers such as Orange (France) or Vodafone (UK) previous patterns of dependence are replicated. Even the International Monetary Fund recognizes that new technologies increase inequality in the absence of countervailing policy (Tetflow, Citation2017). Such an outcome is in contrast to common perceptions that developing countries, by leapfrogging previous technologies and their infrastructures, are ‘catching up’ faster to developed economies than otherwise might be the case. Furthermore, the profusion and diffusion of digital devices and internet access allow for new forms of governmentality and surveillance associated with digital platforms to proliferate (see Murakami Wood & Monahan, Citation2019). While skills upgrading is one part of the equation to counter such potentially negative tendencies, this needs to be part of a broader industrial and skills development and upgrading strategy.

Digitalization of communication may be a necessary but not sufficient condition for the structural transformation of African economies. The diffusion and up-grading of digital skills, and improved literacy are certainly worthwhile investments in terms of fostering economic development if they form part of a coherent economic development strategy aimed at structural diversification of economies by taking advantage of opportunities for import substitution, export promotion and the fulfillment of domestic demand (Riddell, Citation1990). Exports play a key role in unlocking foreign exchange constraints on growth (Cramer et al., Citation2020) and under globalization industrial sequencing should now perhaps favor export-promotion before industrialization (Whitfield & Staritz, Citation2021). This will entail the development of domestically embedded, whether local or transnational capital, firm capabilities or trait making. However the fourth industrial revolution, including robotics, the impacts of COVID and ongoing global geopolitical conflicts and tensions will make attracting labor-intensive FDI even more difficult to developing countries; particularly those perceived to have poor business environments (Baldwin, Citation2019; Carmody, Citation2020). Consequently, there is a greater need to develop indigenous businesses, sometimes through joint ventures with FDI, as China has. For example, Africa hosts only two of the world’s top 100 platform companies, both owned by the South African company Naspers, and these are small by global standards (Acs et al., Citation2020). Furthermore, this may have changed as Naspers has engaged in repeated divestments from the Chinese platform giant Tencent in recent years (Juan, Citation2023).

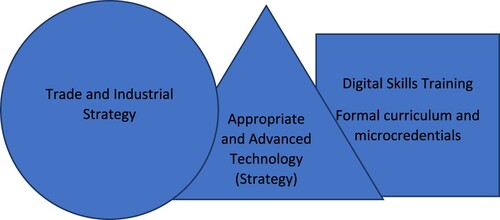

A DDT can be both a cause and effect of economic development. A DDT would mean that firms would shift from thin forms of information technology usage, such as texting customers, to thicker ones such as the use of artificial intelligence algorithms to process data around market segmentation for example (Murphy & Carmody, Citation2015). More advanced technological capabilities allow for greater productivity gains and the innovative deployment of ICT to address crucial supply, design, marketing, production and other issues. However, the prospects for substantial value capture within the digital space itself are largely precluded by current Northern-based near-monopolies in this area (Kwet, Citation2019). Reversing this requires a nested approach, where technology and skills strategy are seen as sub-set of broader industrial policy (see ).

Digital skills, by themselves, are not a magic bullet. In contrast to orthodox theory, Hern (Citation2023) finds that the common feature of generalized success in economic and social development in Africa, for example, is an activist state. A DDT will mean African economies moving from being information societies to knowledge economies, in time. As part of an articulated economic development strategy, this will require investment in digital skills and in the higher educational system. There must be a close alignment between the supply of skills produced and demand for these as the structure of the economy shifts from disarticulation to articulation with global production and innovation networks in ways which are developmentally beneficial rather than oftentimes regressive (Cooke, Citation2017; Selwyn & Leyden, Citation2022).

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Silvia Masiero, Amir Anwar, Richard Heeks, Johnny Lyons and Francis Owusu and the journal referees for their comments, which have substantially improved the paper. Any errors of fact or interpretation are mine.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 While the concept of the digital divide ‘is usually defined as the gap between people who do and do not have access to forms of information and communication technology’ (Van Djik, Citation2017), it has been reconceptualized in different ways, such as through the concept of the ‘second digital divide’ (Hargittai, Citation2002 cited in Van Djik, Citation2017) for example to encompass issues such as user skills and capabilities.

2 Structural transformation is generally taken to refer to substantial increases in productivity across sectors, and the emergence of new higher value added and higher productivity industries and niches (Andreoni et al., Citation2021).

3 This data was derived from a global survey of internet users aged 16-64. However, other research has found that developed country users spend more time online (see Pariona, Citation2017).

4 There are however substantial differences in average smart phone prices across regions. For example, the average price of a smart phone in ‘emerging Asia’ was US $183 in 2017 versus, U$645 in ‘Developed Asia’ (Richter, Citation2018). In some places average prices for smartphones may rise as newer, more complex models are brought out such as the iPhone 15 which costs approximately US $800, with the lowest memory capacity, in the US.

5 Arguably people pay with their time looking at ads and uploading content.

6 This is the number of active users per 100 of population.

7 A technology start-up company valued at more than US $1 billion. However, Jumia does have substantial foreign investment in it. ‘Jumia is a start-up internal to Africa Internet Group (AIG), a leading e-commerce group in Africa with Rocket Internet, MTN Telecommunications, Millicom, Orange, Axa, and Goldman Sachs as investors during our observation period’ (Peprah et al., Citation2022, p. 10).

8 Jumia’s difficulties are similar to those of other virtual capitalist companies, in that profits are derived from increasing share prices initially rather than service provision. Uber has never made a profit. However at some point the ‘chickens come home to roost’ as operational profitability must eventually underwrite or be reflected in stock prices. Jumia’s performance improved as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic.

9 M-Pesa, discussed earlier, actually evolved from the indigenous innovation of taking photos of phone credit vouchers and texting them to others by way of payments, and the company is largely owned by UK-based Vodafone (Meagher, Citation2018).

10 Relatively high rates of economic growth in the early years of the new millennium were driven largely by higher primary commodity prices.

11 Of course there may be other substantial benefits, such as being able communicate with distant family members that improve wellbeing or quality of life in addition to widening choice sets (Kleine, Citation2013).

12 Almost a fifth of Ghanaian companies recruit only internationally for digitally-skilled jobs (IFC, Citation2019).

13 Adverse differential incorporation means that places or regions are differently incorporated into the global system, based on what their staple exports are, for example, but still disadvantageously.

References

- Acs, Z., Szerb, L., Song, A., Komlósi, E., & Lafuente, E. (2020). The digital platform economy index 2020. http://thegedi.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/DPE-2020-Report-Final.pdf

- Adegoke, Y. (2018). In African cities, the “gig economy” is called the economy. Quartz Africa, Retrieved June 19, 2023, from https://qz.com/africa/1440879/uber-airbnb-lead-africas-informal-gigeconomy/.

- Afutu-Kotey, R. L., & Gough, K. V. (2022). Bricolage and informal businesses: Young entrepreneurs in the mobile telephony sector in Accra, Ghana. Futures, 135, 102487. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2019.102487

- Altenburg, T., Chen, X., Lütkenhorst, W., Staritz, C., & Whitfield, L. (2020). Exporting out of China or out of Africa? Automation versus relocation in the global clothing industry, Discussion Papers 1/2020. German Development Institute / Deutsches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik (DIE. ttps://ideas.repec.org/p/zbw/diedps/12020.html.

- Andreoni, A., Mondliwa, P., Roberts, S., & Tregenna, F. (2021). Framing structural transformation in South Africa and beyond. In A. Andreoni, P. Mondliwa, S. Roberts, & F. Tregenna (Eds.), Structural transformation in South Africa: The challenges of inclusive industrial development in a middle-income country (pp. 1–27). Oxford University Press.

- Anwar, M. A., & Graham, M. (2020). Hidden transcripts of the gig economy: Labour agency and the new art of resistance among African gig workers. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 52(7), 1269–1291. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X19894584

- Anwar, M. A., & Graham, M. (2022). The digital continent: Placing Africa in planetary networks of work. Oxford University Press.

- Apeti, A. E., & Edoh, E. D. (2023). Tax revenue and mobile money in developing countries. Journal of Development Economics, 161, 103014. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2022.103014

- Arora, P. (2019). The next billion users: Digital life beyond the West. Harvard University Press.

- Baldwin, R. E. (2019). The globotics upheaval: Globalisation, robotics and the future of work. Oxford University Press.

- Banerjee, A. V., & Duflo, E. (2012). Poor economics: Barefoot hedge-fund managers, DIY doctors and the surprising truth about life on less than $1 a day. Penguin Books.

- Banga, K., Harbansh, P., & Singh, S. (2023). Digital de-industrialization, global value chains, and structural transformation: Empirical evidence from low- and middle-income countries. WIDER Working Paper 2023/65. Helsinki: UNU-WIDER. https://doi.org/10.35188/UNU-WIDER/2023/373-4

- Bateman, M., Duvendack, M., & Loubere, N. (2019). Is fin-tech the new panacea for poverty alleviation and local development? Contesting Suri and Jack”s M-Pesa findings published in Science. Review of African Political Economy, 46, 480–495. https://doi.org/10.1080/03056244.2019.1614552

- BBC. (2020). Jumia: The e-commerce start-up that fell from grace. Retrieved June 19, 2023, from https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-52439546.

- Boamah, E. F., Murshid, N. S., & Mozumder, M. G. M. (2021). A network understanding of fintech (in)capablities in the Global South. Applied Geography, 135, 102538. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeog.2021.102538

- Bush, R. (2007). Poverty and neoliberalism: Persistence and reproduction in the Global South. Pluto.

- Caballero, A., & Bashir, S. (2020). Africa needs digital skills across the economy, not just in the tech sector. Retrieved June 16, 2023, from https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/10/africa-needs-digital-skills-across-the-economy-not-just-tech-sector/.

- Carmody, P. (1998). Constructing alternatives to structural adjustment in Africa. Review of African Political Economy, 75, 25–46.

- Carmody, P. (2012). The informationalization of poverty in Africa? Mobile phones and economic structure. Information Technologies and International Development, 8(3), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.4018/jiit.2012070101

- Carmody, P. (2013). A knowledge economy or an information society in Africa? Thintegration and the mobile phone revolution. Information Technology for Development, 19(1), 24–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/02681102.2012.719859

- Carmody, P. (2020). Meta-trends in global value chains and development: Interactions with COVID-19 in Africa. Transnational Corporations: Investment and Development, 27(2), 143–155. https://doi.org/10.18356/64e3f6fe-en

- Carmody, P., & Fortuin, A. (2019). “Ride-sharing”, virtual capital and impacts on labor in Cape Town, South Africa. African Geographical Review, 38(3), 196–208. https://doi.org/10.1080/19376812.2019.1607149

- Carmody, P., Kragelund, P., & Reboredo, R. (2020). Africas shadow rise: China and the mirage of African economic development. Zed.

- Carmody, P., Murphy, J. T., Grant, R., & Owusu, F. (2023). The urban question in Africa: Uneven geographies of transition. Wiley with Royal Geographical Society.

- Chetty, K., Aneja, U., Mishra, V., Gcora, N., & Josie, J. (2018). Bridging the digital divide in the G20: Skills for the new age. Economics, 12(1), 20180024. https://doi.org/10.5018/economics-ejournal.ja.2018-24

- Choi, J., Dutz, M., & Usman, Z. (Eds.). (2020). The future of work in Africa: Harnessing the potential of digital technologies for all. Agence Francaise de Development and World Bank Group.

- Cooke, P. (2017). Complex spaces: Global innovation networks & territorial innovation systems in information & communication technologies. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, 3(9). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40852-017-0060-5

- Cramer, C., Sender, J., & Oqubay, A. (2020). African economic development: Evidence, theory, policy (1st ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Eubanks, V. (2014). Want to predict the future of surveillance? Ask poor communities. The American Prospect. http://www.prospect.org/article/want-predict-future-surveillance-ask-poor-communities

- Foster, C. (2023). Intellectual property rights and control in the digital economy: Examining the expansion of M-Pesa. The Information Society, 40(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/01972243.2023.2259895

- Foster, C., & Azmeh, S. (2023). Aligning digital and industrial policy to foster future industrialization. Industrial Analytics Platform. https://iap.unido.org/articles/aligning-digital-and-industrial-policy-foster-future-industrialization

- Gerschenkron, A. (1962). Economic backwardness in historical perspective: A book of essays [A reduced photographic reprint of the edition of 1962]. Harvard University Press.

- Gigler, B. (2021). Putting people first in digital transformation. Linkedin Article. https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/putting-people-first-digital-transformation-bjorn-soren-gigler-phd-%3FtrackingId=F53jdpQxTJaPbTIzesEjpg%253D%253D/?trackingId=F53jdpQxTJaPbTIzesEjpg%3D%3D

- Gosavi, A. (2018). Can mobile money help firms mitigate the problem of access to finance in Eastern sub-Saharan Africa? Journal of African Business, 19(3), 343–360. https://doi.org/10.1080/15228916.2017.1396791

- Government Technology. (2023). In what country do people spend the most time online? Retrieved May 9, 2024, from https://www.govtech.com/question-of-the-day/in-what-country-do-people-spend-the-most-time-online.

- Graham, M. (2008). Warped geographies of development: The internet and theories of development. Geography Compass, 2/3(3), 771–789. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-8198.2008.00093.x

- Greene, D. (2021). The promise of access: Technology, inequality and the political economy of hope. MIT Press.

- Hargittai, E. (2002). Second-level digital divide: Differences in People's Online Skills. First Monday. https://firstmonday.org/ojs/index.php/fm/article/view/942

- Hartnett, M. (2019). Digital divides. Oxford Bibliographies. Retrieved June 19, 2023, from https://www.oxfordbibliographies.com/display/document/obo-9780199756810/obo-9780199756810-0222.xml#:~:text=The%20term%20%E2%80%9Cdigital%20divide%E2%80%9D%20emerged,information%2C%20and%20other%20digital%20technologies.

- Harvey, D. (2003). The fetish of technology: Causes and consequences. Macalester International, 13, Article 7. Available at: http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/macintl/vol13/iss1/7.

- Haryanti, T., Rakhmawati, N. A., & Subriadi, A. P. (2023). A comparative analysis review of digital transformation stage in developing countries. Journal of Industrial Engineering and Management-Jiem, 16(1), 150–167. https://doi.org/10.3926/jiem.4576

- Heeks, R. (2022). Digital inequality beyond the digital divide: Conceptualizing adverse digital incorporation in the global south. Information Technology for Development, 28(2), 688–704. https://doi.org/10.1080/02681102.2022.2068492

- Heeks, R., Ezeomah, B., Iazzolino, G., Krishnan, A., Pritchard, R., Renken, J., & Zhou, Q. (2023). The principles of digital transformation for development (DX4D): Systematic literature review and future research agenda. Digital Papers Working Series, No. 104. https://hummedia.manchester.ac.uk/institutes/gdi/publications/workingpapers/di/dd_wp104.pdf

- Heeks, R., Gomez-Morantes, J. E., Graham, M., Howson, K., Mungai, P., Nicholson, B., & Van Belle, J.-P. (2021). Digital platforms and institutional voids in developing countries: The case of ride-hailing markets. World Development, 145, 105528. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2021.105528

- Hern, E. (2023). Explaining successes in Africa: Things don't always fall apart. Lynn Rienner.

- Innovate Media. (2020). Digital advertising and the entertainment industry. Retrieved June 19, 2023, from innovatemedia.com/news/pre-roll-entertainment-industries-trends/

- International Finance Corporation (IFC). (2019). Digital skills in Sub-Saharan Africa. ifc.org/wps/wcm/connect/industry-ext-content/ifc-external-corporate-site/education/publications/digital + skills + int + sub-saharan + africa.

- Internet World Stats. (2023). World internet users statistics and 2021 world population stats. Retrieved June 19, 2023, from https://www.internetworldstats.com/stats.htm

- James, J. (2021). New perspectives on current development policy: COVID-19, the digital divide, and state internet regulation. Springer.

- Jaumotte, F., Lall, S., Papageorgiou, C., & Topalova, P. (2007). IMF survey: Technology widening rich-poor gap. Retrieved June 19, 2023, from https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2015/09/28/04/53/sores1010a.

- Jeffrey, C. (2010). Timepass: Youth, class and the politics of waiting in India. Stanford University Press.

- Jensen, R. (2007). The digital provide: Information (technology), market performance, and welfare in the south Indian fisheries sector. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 122(3), 879–924. https://doi.org/10.1162/qjec.122.3.879

- Juan, L. (2023). Naspers pares stake in China’s tencent again; internet giant buys back twice as much. Yicai Global. Retrieved June 16, 2023, from https://www.yicaiglobal.com/news/nasper-pares-stake-in-chinas-tencent-again-internet-giant-buys-back-twice-as-much.

- Kandri, S. (2019). Africa’s future is bright-and-digital. Retrieved June 16, 2023, from blogs.worldbank.org/digital-development/africa-future-bright-and-digital..

- Kara, S. (2023). Cobalt red: How the blood of the Congo powers our lives (1st ed.). St. Martin's Press.

- Kim, J., Park, J., & Jun, S. (2022). Digital transformation landscape in asia and the pacific: aggravated digital divide and widening growth gap. ESCAP Working Paper Series.

- Kleibert, J. M., & Mann, L. (2020). Capturing value amidst constant global restructuring? Information-technology-enabled services in India, the Philippines and Kenya. The European Journal of Development Research, 32(4), 1057–1079. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41287-020-00256-1

- Kleine, D. (2013). Technologies of choice?: ICTs, development, and the capabilities. MIT Press.

- Komminoth, L. (2023). Social media put pressure on African e-commerce platforms. African Business. June, 52–55.

- Koss, F. A. (2001). Children falling into the digital divide. Journal of International Affairs, 55(1), 75–90.

- Kwet, M. (2019). Digital colonialism: US empire and the new imperialism in the global south. Race & Class, 60(4), 3–26. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306396818823172

- Lee, K. (2024). Economics of technology cycle time (TCT) and catch-up by latecomers: Micro-, meso-, and macro-analyses and implications. Journal of Evolutionary Economics. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00191-024-00847-9

- Leonard, D. K., & Straus, S. (2003). Africa”s stalled development: International causes and cures. Lynne Rienner Publishers.

- Lie, J. H. S. (2015). Developmentality: An ethnography of the world bank-Uganda partnership (1st ed.). Berghahn Books.

- Malm, M., & Toyama, K. (2021). The burdens and the benefits: Socio-economic impacts of mobile phone ownership in Tanzania. World Development Perspectives, 21, 100283. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wdp.2020.100283

- Mann, L. (2023). The evolution of the global Information Technology Enabled Services (ITES) sector and the shrinking gains of FDI for low- and middle-income economies. Sustainable Global Supply Chains Research Network. Retrieved June 16, 2023, fromhttps://www.sustainablesupplychains.org/the-evolution-of-the-global-information-technology-enabled-services-ites-sector-and-the-shrinking-gains-of-fdi-for-low-and-middle-income-economies/.

- Masiero, S. (2016). Digital governance and the reconstruction of the Indian anti-poverty system. Oxford Development Studies, 818, 1–16.

- Meagher, K. (2018). Cannibalizing the informal economy: Frugal innovation and economic inclusion in Africa. European Journal of Development Research, 30(1), 17–33. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41287-017-0113-4

- Molony, T. (2007). I don't trust the phone; It always lies: trust and information and communication technologies in Tanzanian micro- and small enterprises. Information Technologies and International Development, 3(4), 67–83. https://doi.org/10.1162/itid.2007.3.4.67

- Murakami Wood, D., & Monahan, T. (2019). Platform surveillance. Surveillance & Society, 17(1-2), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.24908/ss.v17i1/2.13237

- Murphy, J. T., & Carmody, P. (2015). Africa’s information revolution: Technical regimes and production networks in South Africa and Tanzania. John Wiley & Sons Inc.

- Ng’weno, A., & Porteous, D. (2018). Let”s be real: The informal sector and the gig economy are the future, and the present, of work in Africa, CGD Notes. Retrieved June 19, 2023, from https://www.cgdev.org/publication/lets-be-real-informal-sector-and-gig-economy-are-future-andpresent-work-africa.

- Parekh, N., & Hare, A. (2020). The rise of mobile money in sub-Saharan Africa: Has this digital technology lived up to its promises? Retrieved June 19, 2023, from https://www.povertyactionlab.org/blog/10-22-20/rise-mobile-money-sub-saharan-africa-has-digital-technology-lived-its-promises.

- Pariona, A. (2017). Countries where people spend the most time online. World Atlas. Retrieved June 16, 2023, from https://www.worldatlas.com/articles/top-countries-which-spend-the-greatest-amount-of-time-online.html.

- Peng, D. (2019). Cell phone cost comparison timeline. Ooma Phone Blog. Retrieved June 16, 2023, from https://www.ooma.com/blog/home-phone/cell-phone-cost-comparison/.

- Peprah, A. A., Giachetti, C., Larsen, M. M., & Rajwani, T. S. (2022). How business models evolve in weak institutional environments: The case of Jumia, the Amazon. Com of Africa. Organization Science, 33(1), 431–463. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2021.1444

- Poushter, J. (2016). Internet access growing worldwide but remains higher in advanced economies. Pew Research Center. Retrieved June 16, 2023, from https://www.pewresearch.org/global/2016/02/22/internet-access-growing-worldwide-but-remains-higher-in-advanced-economies/.

- Qureshi, S. (2023). Digital transformation for development: A human capital key or system of oppression? Information Technology for Development, 29(4), 423–434. https://doi.org/10.1080/02681102.2023.2282269

- Review 42. (2023). How much time do people spend on social media? Retrieved October 1, 2023, from https://review42.com/resources/how-much-time-do-people-spend-on-social-media.

- Richter, F. (2018). How smartphone prices differ across the globe. Statista. Retrieved June 16, 2023, from https://www.statista.com/chart/12685/smartphone-asp-by-region/.

- Riddell, R. (1990). Manufacturing Africa: Performance and prospects of seven African countries. James Currey.

- Rogers, E. (2003). Diffusion of innovations (5th ed.). Simon & Schuster.

- Scharwat, C. P. (2014). Paying taxes through mobile money: Initial insights into P2G and B2G payments. GSMA.

- Selwyn, B., & Leyden, D. (2022). Oligopoly-driven development: The word bank’s trading for development in the age of global value chains in perspective. Competition & Change, 26(2), 174–196. https://doi.org/10.1177/1024529421995351

- Shema, A. (2019). Effective credit scoring using limited mobile phone data. In Paper presented at the Proceedings of the Tenth International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies and Development, Ahmedabad, India. https://doi.org/10.1145/3287098.3287116

- Steel, G. (2021). Going global - going digital. Diaspora networks and female online entrepreneurship in Khartoum, Sudan. Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences, 120, 22–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2021.01.003

- Storper, M. (1985). Oligopoly and the product cycle - essentialism in economic-geography. Economic Geography, 61(3), 260–282. https://doi.org/10.2307/143561

- Talking Banking Matters. (2022). Driven by purpose: 15 years of M-Pesa’s evolution. Retrieved June 16, 2023, from https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/financial-services/our-insights/driven-by-purpose-15-years-of-m-pesas-evolution.

- Tasamba, J. (2019). Africa's first smartphone launched in Rwanda. Retrieved June 16, 2023, from https://www.aa.com.tr/en/africa/africas-first-smartphone-launched-in-rwanda/1605397#.

- Taylor, L. (2017). What is data justice? The case for connecting digital rights and freedoms globally. Big Data and Society. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053951717736335

- Tetflow, G. (2017). Blame technology not globalisation for rising inequality, says IMF. Retrieved June 19, 2023, from https://www.ft.com/content/cfbd0af6-1e0b-11e7-b7d3-163f5a7f229c.

- Time. (2023). Exclusive: OpenAI used Kenyan workers on less than $2 per hour to make ChatGPT less toxic. Retrieved June 19, 2023, from https://time.com/6247678/openai-chatgpt-kenya-workers/.

- Van Djik, J. (2017). Digital divide: Impact of access. In P. Rossler, C. Hoffner, & L. Zoonen (Eds.), International encyclopedia of media effects. Wiley Online. https://www.utwente.nl/en/bms/vandijk/publications/digital_divide_impact_access.pdf

- Vass, L. (2018). The internet is everywhere, except in the economic growth figures. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/the-internet-has-done-a-lot-but-so-far-little-for-economic-growth-105294

- Veen, A., Kaine, S., Goods, C., & Barratt, T. (2020). The ‘gigification’ of work in the 21st century. In P. Holland, & C. Brewster (Eds.), Contemporary work and the future of employment in developed countries (1st ed., pp. 15–32). Routledge.

- Vernon, R. (1966). International investment and international trade in the product cycle. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 80(2), 190–207. https://doi.org/10.2307/1880689

- Voigt, J. (2011). Mobile phone: Weapon against global poverty. CNN. Retrieved June 16, 2023, from https://edition.cnn.com/2011/10/09/tech/mobile/mobile-phone-poverty/index.html.

- Wang, Y. (2020). First-time internet users in Nigeria use the internet in a unique way. Here’s why that matters. Retrieved June 19, 2023, from https://www.kaiostech.com/first-time-internet-users-in-nigeria-use-the-internet-in-a-unique-way-heres-why-that-matters/.

- Wani, T., & Ali, S. (2015). Innovation diffusion theory: Review and scope in the study of the adoption of smartphones in India. Journal of General Management Research, 3(2), 101–118.

- WEF (World Economic Forum). (2022). As young Africans push to be online data costs stand in the way. Retrieved June 19, 2023, from https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2022/06/as-young-africans-push-to-be-online-data-cost-stands-in-the-way/.

- Whitfield, L., & Staritz, C. (2021). The learning trap in late industrialisation: Local firms and capability building in Ethiopia’s apparel export industry. Journal of Development Studies, 57(6), 980–1000. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2020.1841169

- World Bank. (2021). Gross capital formation (% of GDP). Retrieved June 19, 2023, from https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NE.GDI.TOTL.ZS.