ABSTRACT

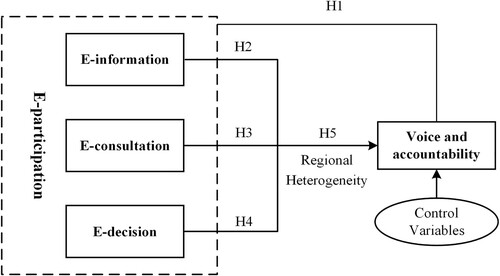

E-participation has become a new potential factor for improving voice and accountability through the introduction of digital services and the transformation of governance. However, the path and its theoretical interpretation are still unclear, and its actual effect lacks empirical verification. Drawing on the concept of digital-era governance, this study explored how e-participation can theoretically improve a country’s voice and accountability. Empirical verification was performed using the ordinary least squares method with sample data from 182 countries. The results show that global e-participation positively affects voice and accountability in three channels: e-information, e-consultation, and e-decision. Moreover, the effects of e-participation on voice and accountability are more pronounced in least developed countries than in developing and developed countries. This study identifies theoretical explanations for using e-participation to improve voice and accountability, and provides practical implications for how information technology can be used to achieve inclusive and meaningful participation.

1. Introduction

Voice and accountability (VA) are novel governance tools for effective service delivery, good governance, and citizen empowerment (Brinkerhoff & Wetterberg, Citation2016), meaning that the public’s political rights are guaranteed, especially in elections, government supervision, and broad political participation rights (Chan et al., Citation2021). The World Bank defines VA as the extent to which a country’s citizens can participate in selecting their government, their freedom of expression, freedom of association, and free media (Kaufmann et al., Citation2010). The core of VA is that citizens can participate in the selection of governments and their decisions and have the right to participate in the formulation and implementation of public policy (Zou et al., Citation2023). VA provides a stable political environment for social development (Xin et al., Citation2023). However, global VA in the digital age faces various difficulties, such as the low degree of political participation (Norris, Citation2010), media-controlled public opinion (Leroux et al., Citation2020), low voting rates (Asher et al., Citation2019; Leroux et al., Citation2020), digital divide, and information overload (Parycek et al., Citation2017).

With the integration of information and communication technology (ICT) and social development, the focus of ICT for Development (ICT4D) has expanded from economic growth to the improvement of civil power (Zheng et al., Citation2018) and VA (Sein et al., Citation2019; Sharma et al., Citation2022). Given the difficulties faced by VA in the digital age, as a representative of ICT4D in the political field, digital governments not only provide public services but also give rise to a large number of e-participation forms, such as online elections, polls, hearings, and expressions of political will (Lu & Luo, Citation2019; Pirannejad & Janssen, Citation2017; Zou et al., Citation2023). The United Nations (UN) defines e-participation as a government’s use of online services to provide information to its citizens, interact with stakeholders, and engage in decision-making processes (United Nations, Citation2020).

With the development of digital government as a new form of digital-era governance, e-participation has become a new way of connecting citizens and government; changing the form, scope, and content of public participation; and receiving widespread attention (Coelho et al., Citation2022). E-participation promotes information disclosure and builds a two-way channel for government-citizen interaction to help improve government transparency (Bonsón et al., Citation2012; Yusup et al., Citation2018), control corruption (Lopez-Lopez et al., Citation2018) and enhance accountability (Braga & Gomes, Citation2018). The UN identified the main purpose of e-participation as governments incorporating public voices into decision-making processes and increasing the VA of vulnerable groups (United Nations, Citation2022).

Based on this, existing studies have attempted to explore the effects of e-participation on VA. However, there are several limitations. First, research on e-participation’s impact on VA is controversial, with some scholars arguing for a positive impact (Akmentina, Citation2022; Braga & Gomes, Citation2018) and others questioning it (Escher & Riehm, Citation2017; Parycek et al., Citation2017). Second, most studies quantify e-participation at an overall level (Bragazzi et al., Citation2020; Waheduzzaman & Khandaker, Citation2022), which does not reveal differences in the extent of utilization and effectiveness of the different components of e-participation (Santamaria-Philco et al., Citation2019). Third, relevant empirical studies have mostly focused on a specific country or region, with less evidence from all over the world (Leroux et al., Citation2020; Lindquist & Huse, Citation2017). However, the progress and focus of building e-participation may vary between countries owing to the level of development, and the impact on VA may also be heterogeneous (United Nations, Citation2020). Technological development is embedded in a country’s economy, society, politics, and culture and these developments affect each other. Regional studies cannot explain and verify the universal law that e-participation promotes VA on a global scale; therefore, further heterogeneity analysis is required (Waheduzzaman & Khandaker, Citation2022). Finally, although some existing studies have preliminarily analysed the correlation between e-participation and VA through quantitative analysis methods, the pathway mechanism of its influence requires further theoretical and empirical research (Silal & Saha, Citation2021).

Therefore, this study analysed the relationship between e-participation and VA to answer the following questions: How does e-participation promote VA? What components of e-participation correlate with improvements in VA? Are there regional heterogeneities in these effects across countries? This study will help indicate the relationship between e-participation and VA, and provide recommendations for achieving inclusive participation in different countries. In the following content, Section 2 reviews relevant studies. Section 3 elaborates on the theoretical explanation and influence path of e-participation on VA based on the concept of digital-era governance and proposes the corresponding research hypotheses. Section 4 introduces the research method, sample selection, variable measurements, and data collection. Section 5 adopts the ordinary least squares (OLS) method to estimate the effects of e-participation on VA, and tests for regional heterogeneity. Section 6 concludes the paper by summarizing the findings to help make evidence-based decisions for the further development of e-participation.

2. Literature review

2.1. Definition and measurement of e-participation

E-participation refers to the use of ICT by the public and government to interact, create spaces and new opportunities for collaboration, and influence public decision-making (Coelho et al., Citation2022; Zissis et al., Citation2009). E-participation involves not only using ICT to implement information and project management activities, but also facilitating the government’s transition to public-centred governance to achieve citizen empowerment (Sanchez-Tortolero et al., Citation2019). The UN e-participation index (EPI) assesses e-participation using a three-point scale that distinguishes between the provision of information, consultation, and decision and measures the use of social networks, newsgroups, blogs, polls, surveys, and other interactive tools to facilitate engagement (United Nations, Citation2020). Specifically, (1) e-information refers to providing public information and access to information for citizens, (2) e-consultation refers to providing advice and feedback to the public at different stages of policy or public services, and (3) e-decision refers to giving citizens the right to participate in policy and specify the contents and methods of services (David, Citation2020). The Department of Economic and Social Affairs of the United Nations (UNDESA) analyses materials on e-participation covering assessment in the areas of e-information, e-consultation, and e-decision to assess the national online presence of all 193 UN Member States. Mathematically, the EPI is normalized by taking the total score value for a given country, subtracting the lowest total score for any country in the survey, and dividing it by the range of total score values for all countries (United Nations, Citation2020). This index shows significant differences across countries and is often used to analyse the effects or influencing factors of the development of e-participation worldwide (Gulati et al., Citation2014).

2.2. Role of e-participation

Improving the political power of citizens is a political guarantee of sustainable social development (Zheng et al., Citation2018). In the digital age, the focus of ICT4D must shift from economic development to citizen empowerment, promoting social development by improving the interaction between the government and citizens (Karkin & Janssen, Citation2020; Sharma et al., Citation2022). As an extension of ICT4D in the political field, e-participation has become a topic in the field of public administration and is utilized by governments worldwide to increase citizen participation and transparency in government decision-making (United Nations, Citation2020).

Studies have shown that e-participation has a positive impact on enhancing citizens’ political influence and promoting effective participation (Pinto et al., Citation2022; Stratu-Strelet et al., Citation2021; Tai et al., Citation2020). Many countries have built e-participation platforms to facilitate the collaboration and interaction between governments and citizens (Kotina et al., Citation2022; Sivarajah et al., Citation2016; Yang et al., Citation2021). Additionally, e-participation has a significant impact on the perception of corruption, leading to more inclusive human development and superior environmental performance through corruption control (Hu & Zheng, Citation2020; Zheng, Citation2016). Androniceanu and Georgescu (Citation2022) noted that e-participation is a predictor of corruption control and government effectiveness. As shown above, existing studies reveal that e-participation plays a positive role in many fields, but evidence on its effectiveness on macro-level governance outcomes is insufficient, particularly for VA (Silal & Saha, Citation2021).

2.3. Relationship between e-participation and VA

In recent years, the relationship between e-participation and VA has attracted scholars’ attention. Secinaro et al. (Citation2022) analysed the case of Madrid (Spain), confirming that e-participation platforms help expand the scope and depth of participation, emphasizing the need to strengthen research on the links between e-participation and VA. Yusup et al. (Citation2018) conducted a questionnaire study in Malaysia and found that ICT can improve access to government information, uphold government integrity, and promote democracy and accountability. Akmentina (Citation2022) analysed the plan-making processes in 12 Baltic cities, demonstrating that e-participation has led to a higher call for greater transparency and accountability on city issues. However, relevant studies have several limitations.

First, the role of e-participation in VA remains controversial. Although these scholars believe that e-participation has a positive impact on VA, some have questioned this. Norris (Citation2010) argued that e-participation was limited to providing information and services to external stakeholders and did not show the potential for achieving e-democracy, as expected. Waheduzzaman and Khandaker (Citation2022) also indicated that there are some limitations to the present form of e-participation in ensuring that citizens’ voices hold services providers accountable. Some studies also showed that e-participation is faced with unbalanced development (Perez-Morote et al., Citation2020), information cocoon room (Escher & Riehm, Citation2017), and digital divide (Parycek et al., Citation2017). Therefore, the impact of e-participation on VA requires further validation.

Second, most existing studies quantify e-participation at the overall level, providing evidence for exploring its role in VA (Bragazzi et al., Citation2020; Parycek et al., Citation2017; Waheduzzaman & Khandaker, Citation2022). However, the content and composition of e-participation vary widely, and there may be differences in the degree of utilization and action effects of different compositions of e-participation (Santamaria-Philco et al., Citation2019; Smith et al., Citation2011). Referring to the UN’s definition, this study divides e-participation into three components – e-information, e-consultation, and e-decision, and analyses their impact and path mechanism on VA in detail (United Nations, Citation2020).

Third, the level of e-participation varies among countries owing to differences in political, economic, cultural, social, and technical developments (Lindquist & Huse, Citation2017). Although a few scholars note the diffusion of e-participation across the countries or regions, most are still confined to selected countries or regions, such as 19 OCED countries (Pina et al., Citation2007), Asia (Brewer et al., Citation2008), and Latin America (Trapero, Parra & Sánchez, Citation2019). Considering the significance of cross-national research on a global scale for the development of e-participation, this study attempted to cover more countries to examine the relationship between e-participation and VA. Effective participation must be inclusive, particularly by including the least-developed regions and the most vulnerable and marginalized groups. This study compares the differences between least developed countries and other countries to provide a reference for narrowing regional gaps.

Finally, existing quantitative studies demonstrate the role of e-participation in VA only through correlation analysis and lack sufficient analysis of the impact mechanism under theoretical guidance to further reveal their relationship. For example, Ifinedo et al. (Citation2021) found a correlation between e-participation and VA but regarded VA as a factor that promotes e-participation. This is because of the lack of sufficient theoretical and case analyses to define a causal relationship between the two. As mentioned, the UN views e-participation as a factor that promotes a country’s VA in the digital era. Further theoretical and case analyses are required to determine the role of e-participation in VA. The concept of digital-era governance advocates the role of ICT in public sector reform and emphasizes the process of good governance by returning power to society and citizens (Panagiotopoulos et al., Citation2019). This concept has been used in digital government research and can provide guidance for this study as well (Wang et al., Citation2018).

2.4. Theoretical basis and hypotheses development

2.4.1. Digital-era governance and its implications for this study

In the twenty-first century, with the rapid evolution of ICT, new public management, public services, and digital governance have flourished worldwide (David, Citation2020; Sheryazdanova & Butterfield, Citation2017). The concept of digital-era governance is a response to and an extension of governance needs in the digital era. Dunleavy et al. (Citation2006) pointed out that reintegration, demand-based holism, and digital changes are the three directions for future public governance reform. Specifically, digital-era governance advocates the significant role of ICT in the public sector’s reform to build a flat management mechanism, promote the sharing of power operations, and achieve the process of returning power to society and citizens (Margetts & Dunleavy, Citation2013). Digital-era governance shifts the focus of public sector management from how to regulate and control the delivery of public services in a better way to promoting citizen participation in the whole process of governance and public services delivery with the help of digital tools such as government website homepages, apps, and social software, thus ensuring transparency and accountability in the government (Hanisch et al., Citation2023; Panagiotopoulos et al., Citation2019).

Previous studies have shown that research focusing on digital-era governance in VA has shifted from a theoretical perspective to an application field. Digital-era governance emphasizes the importance of ICT for public participation in political activities, government activities, and public service delivery. It is not a simple combination of digitalization and governance but the use of advanced ICT to promote progressive ideas in governments and a citizen-centred mode of political participation (Margetts & Dunleavy, Citation2013; Perri & Setzler, Citation2002). As shown in , when studying e-participation, scholars applied the concept to the studies of smart city construction (Paskaleva, Citation2009), public policy formulation (Bonsón et al., Citation2012), public participation and cooperation (Milakovich, Citation2012), crisis management (Mao et al., Citation2021) and public value co-creation (Scupola & Mergel, Citation2022).

Table 1. Related studies on the application of digital-era governance in e-participation.

Digital-era governance emphasizes the need for governments to use digital technologies to facilitate the flow of governance information between the government, public, and other social actors, thereby helping governments incorporate public claims into policy formulation, public service design, and government decision-making behavior (Dunleavy et al., Citation2006; Margetts & Dunleavy, Citation2013). Thereby, digital technologies allow the public to participate in governance activities and monitor government actions or officials’ behavior anytime and anywhere with the help of e-participation platforms, which further promote transparency and accountability (Bonsón et al., Citation2012; Milakovich, Citation2012). The public in e-participation activities is no longer a passive recipient of services, but a co-creator of public value. Thus, the concept of digital-era governance provides a feasible perspective to examine why and how e-participation promotes VA and what measures should be taken to improve it (Hanisch et al., Citation2023). The hypotheses of this study were developed based on the above theoretical analyses.

2.5. Hypotheses development

2.5.1. E-participation for voice and accountability improvement

The concept of digital-era governance helps us understand the role of e-participation in improving VA. On the one hand, digital-era governance provides a theoretical basis for understanding the impact of e-participation on VA. Digital-era governance advocates the simple, moral, accountable, responsive, transparent (SMART) governance model, and e-participation is guided by this philosophy and is committed to these values (Twizeyimana & Andersson, Citation2019). First, it provides a good informational environment for public participation. It alleviates ordinary citizens’ information vulnerability and allows marginal groups to have a voice in the political sphere, avoiding irrational behavior caused by information asymmetry (Gulati et al., Citation2014). Second, digital-era governance provides a convenient channel for public participation, which can solve the problem of ‘consultation fatigue’ that often occurs in political decision-making, thereby enhancing the effectiveness and efficiency of public participation. Third, digital and virtual networks reduce the insecurity of political participation, and interactive networks enhance citizens’ political self-efficacy through mobilization and reinforcement, both of which increase their enthusiasm for political participation (Tai et al., Citation2020).

On the other hand, the concept of digital-era governance provides a perspective to examine the extent to which e-participation guarantees and develops VA and what measures should be taken to improve it. Digital government construction is committed to promoting the transformation of the government to transparency and accountability under the concept of digital-era governance, which improves citizens’ voices and expands public participation (John et al., Citation2011). The concept of digital-era governance has been used to facilitate the dissemination of information by governments, address the dilemma of citizen participation, and promote innovation in public participation (Alonso & Castro, Citation2016). This concept is public-centred, and digital government mainly aims to provide citizens with effective and high-quality public services, thereby creating political and social public values other than economic benefits. According to the theory of public value, a digital government provides a direct, equal, and convenient platform dedicated to improving social values, such as efficiency, inclusiveness, democracy, transparency, and participation (Mergel, Citation2014; Twizeyimana & Andersson, Citation2019). The public can participate in politics to realize e-democracy through e-information, e-consultation, and e-decisions, such as online public opinion polls, hearings, and elections (Kneuer & Harnisch, Citation2016).

Hypothesis 1: E-participation development promotes voice and accountability.

2.5.2. E-information for voice and accountability improvement

The first component of e-participation is e-information (United Nations, Citation2020), which is the most common initiative as information sharing and dissemination between governments and public is the basic form of e-participation (Akmentina, Citation2022; Silal & Saha, Citation2021). Previous studies have shown that e-information can provide accessible information on government activities and policies, making the government more transparent and allowing the public to learn about governmental and political issues (Maclean & Titah, Citation2022). The disclosure and transparency of government information can affect public participation, communication, and collaboration. First, digital government information can lower barriers to political participation, expand channels of participation, and amplify public voice in the political process (Halachmi & Greiling, Citation2013). Second, e-information can be copied and diffused to enhance public participation. Third, e-information makes governments more transparent through data and information disclosure and promotes government self-restraint and the supervision of social actors, thus safeguarding VA (Braga & Gomes, Citation2018). However, scholars argue that e-information faces challenges such as information overload, low value density, limited quantity, and difficulty in analysis, which do not facilitate full transparency and accountability (Halachmi & Greiling, Citation2013; Matheus et al., Citation2021).

Many countries have achieved remarkable results in providing e-information via ICT. Regarding public service delivery, Australia and Colombia have set up information platforms where the public can access information and services from the government and post comments and suggestions on Facebook and Twitter, which could affect government activities (Australia, Citation2022). Concerning policymaking, the Saudi Arabian government established an e-Dashboard, where citizens can access public reports and government documents. Such access is conducive to expanding public participation and effectiveness of governance. Regarding the construction of political voices, the Ugandan government has established a free short-messaging service system called the U report, which sends weekly community news and public opinion polls to users, allowing them to participate in political affairs and guaranteeing the public’s right to information and participation (Uganda, Citation2022). The province of Chungcheongnam-do in South Korea was awarded the 2018 UN Public Service Award for providing government financial information containing real-time expenditure information and the number of funds available online, enabling citizens to access local government budget performance, ask questions, and receive responses online in real time (Korea, Citation2022).

Hypothesis 2: E-information development promotes voice and accountability.

2.5.3. E-consultation for voice and accountability improvement

The second component of e-participation is e-consultation (United Nations, Citation2020). At this stage, governments collect and analyse public opinion through digital government platforms, such as government websites, apps, and social media, while drafting policies, designing services, or implementing projects (Simonofski et al., Citation2021; Zhang et al., Citation2024). This makes the public the makers or implementers of policies in e-participation. The digital government system has several e-consultation functions, such as publishing draft opinions on policies or projects; creating topic-specific forums for free public discussion; and creating a special section for collecting opinions, evaluations, and suggestions for improving public services (Oni et al., Citation2020). E-participation enables individuals to provide advice on government actions or policies, helping safeguard citizens’ voice, improving the quality of decision-making and enhances the legitimacy of the political system (Kennedy & Scholl, Citation2016). Previous studies have shown that e-consultation improves the quality of government-citizen interaction, thus improving public voices and promoting the realization of an open and accountable government (James & Petersen, Citation2018).

Countries worldwide are currently developing e-consultations using ICT. Concerning public service delivery, Portugal launched ‘Citizen Point’ in 2014, through which trained civil servants or social service workers provide face-to-face support to the public temporarily uncomfortable with e-services. As of February 2022, more than 3,000 citizen points were launched in Portugal, offering 1,335 public services and facilitating the online use of e-consultations (Eportugal, Citation2022). Regarding policymaking, Bahrain launched the Tawasul system in 2014. Through Tawasul, the public can submit suggestions and complaints to any government department at any time and a professional team can respond promptly. Until January 2020, the system had received thousands of complaints and proposals per year, 99.5% of which were processed within time (Bahrain, Citation2022). For the construction of political voices, the Brazilian government has issued the ‘Digital Government Strategy’, cooperating with the supervisory commissioners in digital public services, strengthening direct interaction between government and society to improve social participation. The President of Brazil also led the establishment of ‘Participa. br’, which has organized more than 200 activities and more than 30 consultations since its establishment (Brazil, Citation2022).

Hypothesis 3: E-consultation development promotes voice and accountability.

2.5.4. E-decision for voice and accountability improvement

E-decision, the third component of e-participation (United Nations, Citation2020), refers to empowering citizens through any online form, including participation in policy formulation, legal amendments, political elections, and government decisions (United Nations, Citation2020). One of the main goals of digital government is to allow the public to influence the government’s decision-making process through social media, government portals, online discussion forums, and e-participation platforms (Malodia et al., Citation2021). E-voting is a representative example of how flexible voting time and location reduce citizens’ time and traffic cost burdens, alleviate information asymmetry, stimulate public participation, and guarantee civil rights (Leroux et al., Citation2020). Sivarajah et al. (Citation2016) found that an e-participation platform with data visualization technology can facilitate citizen – government collaboration and provide a policy compass for government decision-making. As a form of technology-mediated interaction between civil society and the formal political or administrative sphere, e-decisions increase the efficiency of citizen participation in public decision-making processes and enhance the effectiveness of representative democracy (Stratu-Strelet et al., Citation2021).

Citizens’ awareness and e-decision-making behaviors are growing with the popularity of ICT. Regarding public services delivery, the spread of information infrastructure and social media has changed how people report and respond to crises(Pánek et al., Citation2017). A ‘crisis map’ has great potential for national crisis management and refers to the acquisition, analysis, and positioning of social media data for crisis relief personnel through crowdsourcing. It helps governments and the public extract effective information for situational awareness and provides decision support for timely rescue and assistance (Becker & Bendett, Citation2015; Mao et al., Citation2021). Concerning policymaking, the UK established an e-petition platform for the public to express their views, and petitions are submitted to the Parliament to influence decision-making (Asher et al., Citation2019). In August 2020, China started a column on the 14th Five-Year Plan on the official websites and news clients of the People’s Daily and Xinhua News Agency, as well as the Learning Power app, which received more than 1,018,000 comments from netizens and provided references for the preparation of the 14th Five-Year Plan (Xinhua News Agency, Citation2022). In terms of the construction of political voices, e-voting is widely used in many countries in local and parliamentary elections, and has become a new way to participate in elections (United Nations, Citation2020). However, e-decision is still at an early stage of development and currently unable to achieve the desired level of participation and goals, which may not significantly impact local government accountability (Toots, Citation2019).

Hypothesis 4: E-decision development promotes voice and accountability.

2.5.5. Impact of e-participation on voice and accountability in different countries

Alford and Hughes (Citation2008) argued that there is no best way to govern and that the choice of governance tools depends on the nature of the task, specific context, technology, and resources available. When exploring the relationship between e-participation and VA, the heterogeneity caused by a specific context should be considered. Some scholars have noted this phenomenon and considered regional heterogeneity analysis when conducting studies related to e-participation and VA. Zhang et al. (Citation2024) highlighted that differences in citizens’ digital skills and heterogeneity in socioeconomic levels led to differences in the effectiveness of e-participation. Xin et al. (Citation2023) believed that differences in electoral systems in different countries affect the role of e-participation in VA. Kabanov (Citation2022) found that differences in sociopolitical backgrounds make the role of e-participation heterogeneous in VA. Brewer et al. (Citation2008) found that countries that decisively incorporate digital technology into society often have higher VA.

Considering the reports from the UN and World Bank, there is a wide variation in the development of e-participation and VA across countries, while the gross domestic product (GDP), telecommunication infrastructure, and human capital in the least developed group are significantly lower than the corresponding world averages(United Nations, Citation2020; World Bank, Citation2020), the impact of e-participation on VA may vary in different countries. The level and focus of building national e-participation varies with the level of economic development, which leads to different impacts of e-participation on VA (United Nations, Citation2020). Although Internet use is increasing, only one-fifth of the population of the least developed countries (LDCs) have access to it. Approximately 40 percent of the people living in poverty reside in LDCs worldwide. However, these countries still strive to build a sufficient ICT infrastructure and improve the digital literacy of their citizens toward meaningful e-participation (Waheduzzaman & Khandaker, Citation2022). Specifically, e-participation in economically backward countries is mainly reflected in e-information (United Nations, Citation2020). However, because the public often unilaterally accepts the information disclosed by governments, it is difficult for them to participate in the government governance process through the channels of e-consultation and e-decisions, which have an insufficient impact on VA (Vázquez Parra & Arredondo Trapero, Citation2019).

Hypothesis 5:There is regional heterogeneity in the impact of e-participation on voice and accountability.

3. Materials and method

3.1. Research methods

E-participation has become common recently, and its development is still undergoing a dynamic evolutionary process. The UN has been measuring e-information, e-consultation, and e-decisions since 2014; however, too many extreme values of zero exist in the 2014, 2016, and 2018 e-decision indicators. Considering the validity of the sample data and the findings, the data for 2020 was selected for analysis and research in this study.

Given that the variables are cross-sectional data and can be considered continuous, this study adopted the ordinary least squares (OLS) model to examine the impact of e-participation on VA. OLS was chosen for this study because it is used to determine the relationship between variables (Stratu-Strelet et al., Citation2021). Related empirical studies have also used OLS to determine the influencing factors or effects of e-participation (Ifinedo et al., Citation2021; Stratu-Strelet et al., Citation2021; Waheduzzaman & Khandaker, Citation2022). Throughout the empirical analysis, this study used MS Excel 2019 to input and clean the dataset and SPSS 23.0, for statistical analysis. First, this study conducted descriptive statistics to understand the distribution of each variable. Pearson’s correlation was used to analyse the correlation between variables. Second, this study performed the OLS to verify Hypotheses 1–5. The global development of e-participation is uneven and the levels of economic development, social environment, and underlying conditions vary significantly across regions. Hence, this study examined Hypothesis 5 on regional heterogeneity by regressing groups of developed, developing, and least developed countries to compare whether the relationship between e-participation and VA varies by country. Finally, this study tested the robustness of the results to confirm their reliability of empirical results.

3.2. Sample selection

This study was conducted on UN Member States, collecting data from all countries and excluding individuals with missing values for crucial variables, resulting in a sample of 182 countries. Specifically, the UN identifies countries that face specific challenges in their pursuit of sustainable development as LDCs: they have weak human and institutional capacities, low and unequally distributed incomes, and a scarcity of domestic financial resources (United Nations, Citation2022). There are currently 46 LDCs worldwide. Considering the UN definition and the overall sample distribution, the sample of this study included 41 LDCs and 141 developed and developing countries. The distribution of the study samples is shown in .

Table 2. Sample selection and distribution.

3.3. Variable measurement

3.3.1. Independent variables

Considering the required representativeness and scientific validity of the independent variables, the e-participation index and its secondary indices published by the UN E-Government Survey were selected as independent variables for this study. The e-participation index tracks 193 member states and is calculated by summing the values of the 3 categories of e-information, e-consultation, and e-decision, and dividing the total by the result of the normalized maximum possible value, which takes a value between 0 and 1 (United Nations, Citation2020). This index reflects the state of e-participation in each country at a dynamic level and assesses the way, content, and results of public participation, measuring the degree of interaction between the government and the public in e-government and the extent to which public participation plays an effective role in democratization. Although evaluation techniques have been proposed to replace this index, the EPI remains the most popular method in quantitative research because of its geographic coverage (Durkiewicz & Janowski, Citation2020; Kabanov, Citation2022; Meyerhoff Nielsen & Millard, Citation2020; Smith et al., Citation2011).

3.3.2. Dependent variables

The index of VA from the Worldwide Governance Index (WGI) is the dependent variable in this study, which is representative and authoritative, and has been widely recognized by scholars in the field. The World Bank’s WGI includes 6 comprehensive indicators covering the governance levels of more than 200 countries since 1996 in 6 dimensions: VA, political stability and the absence of violence or terrorism, government effectiveness, regulatory quality, rule of law, and control of corruption. The World Bank first proposed the VA index to assess citizens’ democratic rights, capturing perceptions of the extent to which a country’s citizens can participate in selecting their government, as well as freedom of expression, freedom of association, and free media (World Bank, Citation2020). The World Bank calculates the VA index by obtaining hundreds of variables from 31 sources to assess enterprises, non-governmental organizations, multilateral organizations, and other public sector institutions. The World Bank aggregates the data and then harmonizes them with a range of values for this indicator of (−2.5, 2.5) (World Bank, Citation2020).

3.3.3. Control variables

Considering the covariance of the variables and the availability and validity of the data, this study selected the levels of telecommunications infrastructure, regional economic development, and human capital as control variables (Choi et al., Citation2017). Previous studies showed that telecommunication infrastructure helps governments provide information and services to the public through e-government platforms, directly affecting performance in e-participation (Sæbø, Citation2011). Telecommunications infrastructure refers to the supporting supply facilities that provide telecommunication services to the public to ensure the unimpeded security of telecommunication networks and information. The Telecommunication Infrastructure Index (TII) is an arithmetic average composite of four indicators: (1) estimated internet users per 100 inhabitants, (2) number of mobile subscribers per 100 inhabitants, (3) number of wireless broadband subscriptions per 100 inhabitants, and (4) number of fixed broadband subscriptions per 100 inhabitants (United Nations, Citation2020). Because the design, operation, and access of e-participation platforms require large capital investment, relevant studies have shown that GDP per capita is a key factor that directly affects e-participation (Alcaide Muñoz & Rodríguez Bolívar, Citation2021; Ifinedo et al., Citation2021; Ingrams & Schachter, Citation2019; Waheduzzaman & Khandaker, Citation2022). Additionally, regional economic development and human capital affect e-participation and VA, which may result in the Matthew effect (Epstein et al., Citation2014). Specifically, citizens with more developed economies and higher education levels have more opportunities to engage in e-participation, ultimately leading to the increasing marginalization of disadvantaged groups (Harrison & Sayogo, Citation2014). The International Monetary Fund states that the GDP per capita objectively reflects the level of prosperity and economic development of a country or a region, and is a representative macroeconomic indicator, which is usually used to compare the level of economic development of countries in the world (Callen, Citation2016). Human capital includes non-physical capital such as knowledge, ability, and labor proficiency, which is reflected in the ability to generate permanent income for workers. The Human Capital Index (HCI) has four components: (1) adult literacy rate, (2) combined primary, secondary, and tertiary gross enrollment ratio, (3) expected years of schooling, and (4) average years of schooling (United Nations, Citation2020). According to the UN E-Government Survey, TII, HCI, and the e-participation index are non-overlapping variables, and GDP per capita is not included in the composition and measurement of these variables (United Nations, Citation2020), these control variables satisfy the independence requirement.

3.4. Data collection

This study employed cross-country data drawn from the UN E-Government Survey and World Bank WGI databases to conduct empirical tests. There were 182 observations in 2020, covering almost all countries worldwide, after cleaning the dataset for missing values. The TII was obtained from the International Telecommunications Union and HCI was obtained from the United Nations Education Science and Cultural Organization. GDP per capita is obtained from the World Bank report and takes the logarithm of the natural index as a basis to eliminate heteroscedasticity (Leroux et al., Citation2020). All these data sources are representative and authoritative, and observations of the same variable for different samples take the same measurements and data sources. presents the variables and data sources.

Table 3. Variables, indicators, and data sources.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive statistics for variables

presents the descriptive statistics for all the variables. These results show that the average value of the total e-participation index is 0.585, compared with 0.160 when the index was first measured in 2003, demonstrating that the overall level of e-participation worldwide has changed from weak to strong (United Nations, Citation2003). E-information, e-consultation, and e-decisions are processes that deepen e-participation in political life. shows a wide gap between them, which implies that e-participation mostly remains at the e-information and e-consultation stages. Furthermore, the low score of e-decisions and the negative average score of the VA index indicate that the current development of political participation is insufficient and VA level needs to be improved.

Table 4. Descriptive statistics of all variables in groups.

Most variables in have large standard deviations, with the standard deviation of the independent variables being approximately 0.3, whereas the standard deviation of the dependent variable is as high as 0.914. These results indicate considerable variations in the values of the variables between different countries and regions. This study categorized all countries and regions into developed and developing countries and LDCs according to the UN classification criteria for descriptive statistics (UNDESA, 2022), thus exploring inter-group differences in indicators. shows that VA, e-participation, e-information, e-consultation, and e-decisions are much higher in developed and developing countries than in the LDCs, and large gaps exist in the means of all the control variables. The uneven levels of e-participation and VA in countries and regions worldwide confirm the regional heterogeneity preliminarily.

4.2. Correlation analysis of variables

Conducting correlation tests on the variables after the descriptive statistical analysis is necessary to clarify the impact of e-participation on VA. shows the results of Pearson’s correlation analysis, which reveal that all e-participation dimensions are positively correlated with one another (P < 0.001). The correlation coefficients between all variables ranged from 0.567–0.983. Specifically, VA is positively related to e-participation (r = 0.724, P < 0.001), e-information (r = 0.714, P < 0.001), e-consultation (r = 0.671, P < 0.001), and e-decision (r = 0.640, P < 0.001). In addition, HCI, TII, and GDP are also positively correlated with VA and all dimensions of e-participation (r > 0, P < 0.001).

Table 5. Pearson correlation coefficients.

4.3. Regression analysis of variables

This study conducted regression analyses of the dependent variables in each of the three dimensions – e-information, e-consultation, and e-decision – to explore whether and how they impact VA.

4.3.1. Regression analysis of all variables

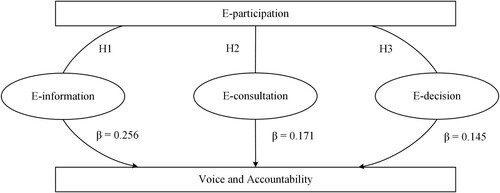

The model test results show that the Durbin – Watson statistics of e-information, e-consultation, and e-decision with VA are approximately 2. The variance inflation factor values for each variable are less than 10 and the standardized residuals follow a normal distribution. These results are within a reasonable range, indicating that the models in this study match well. presents the OLS results. As shown in Model 1, e-participation has a significant positive impact on VA (β = 0.248, P < 0.001), confirming Hypothesis 1.

Table 6. Regression analysis of all variables.

As shown in Model 2, e-information has a significant positive impact on VA (β = 0.256, P < 0.001). The results show that the R2 of the model is 0.782, indicating that the variables can explain the outcome variables well and that the model fits well. The results verify that e-information development promotes the improvement of VA, thus confirming Hypothesis 2.

As shown in Model 3, e-consultation has a significant positive impact on VA (β = 0.171, P < 0.01). E-consultation is a two-way interactive process that safeguards citizens’ voices and government accountability in both procedure and substance. The results show that the R2 of the model is 0.766, indicating that the variables can explain the outcome variables well and that the model fits well. The results verify that e-consultation development improves VA, thus confirming Hypothesis 3.

As shown in Model 4, e-decision has a significant positive impact on VA (β = 0.145, P < 0.001). It enhances transparency and public participation in decision making, thereby promoting VA. The results show that the R2 of the model is 0.764, indicating that the variables can explain the outcome variables well and that the model fits well. These results verify that e-decision development promotes the improvement of VA, thus confirming Hypothesis 4.

4.4. Regression analysis in groups

Previous studies have shown that democracies generally adopt e-participation earlier and use more tools than authoritarian countries (Kneuer & Harnisch, Citation2016). The impact of e-participation on VA varies significantly across different societies and governance systems (West, Citation2004). This study further explores whether regional heterogeneity exists in the impact of e-participation on VA by dividing countries into two groups: developed and developing countries, and LDCs for subgroup regressions. presents the results of regression analysis of the groups.

Table 7. Regression analysis in groups.

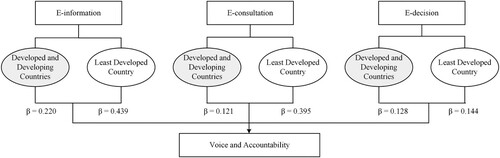

The results show significant positive effects of e-participation, e-information, e-consultation, and e-decision on VA in both categories of countries. The regression coefficient of e-participation on VA is 0.202 in developed and developing countries, and 0.444 in LDCs. The regression coefficient of e-information on VA is 0.220 in developed and developing countries, and 0.439 in LDCs. The regression coefficient of e-consultation on VA is 0.121 in developed and developing countries and 0.395 in LDCs. Similarly, the regression coefficient of e-decision on VA is 0.128 in developed and developing countries, and 0.144 in LDCs. These results indicate that Hypothesis 5 regarding regional heterogeneity is valid, reflected in the promotion of e-participation, and its components on VA are more pronounced in LDCs.

4.5. Robustness test of models

This study adopted robustness tests to guarantee the stability of the OLS model and its index interpretation ability. Several academic approaches can be adopted when conducting robustness tests, such as changing certain parameters, evaluation methods, and indicators for repeated experiments. The models and results are considered robust if no significant changes occur in the symbol or significance.

Considering that e-participation is an emerging practice and may have a time effect due to its rapid development in recent years, the 2018 data for each variable were selected for replication in this study to verify the robustness of the results. As shown in , even after replacing the original data, e-participation (β = 0.307, P < 0.001), e-information (β = 0.293, P < 0.001), e-consultation (β = 0.239, P < 0.001), and e-decision (β = 0.224, P < 0.001) still have a positive impact on VA. Similarly, the regional heterogeneity results for the above indicators continue to exist. The OLS results are all consistent with the main findings, proving that the findings of this study are robust.

Table 8. Robustness test results.

5. Discussions

5.1. Main findings

The success of ICT4D initiatives requires citizen empowerment and placing political power in the hands of citizens to ensure that they are co-creators and participants in governance and public service delivery (Sharma et al., Citation2022). Among them, e-participation helps develop a democratic and stable political system in the digital age, expands a country’s VA, and encourages it to achieve social development goals. This study focused on whether and how e-participation promotes VA, including the following three aspects: (1) Examined the relationship between e-participation and VA in three aspects: e-information, e-consultation, and e-decision. (2) Analysed the path and theoretical explanation of e-participation to promote VA under the guidance of the concept of digital-era governance. (3) Verified the actual impact of e-participation on VA and tested the existence of regional heterogeneity using data from 182 countries in 2020. The main findings of this study’s theoretical and empirical analyses are as follows:

First, the findings confirm the promotional role of global e-participation on VA, and the robustness test further verifies this positive impact.

This study used the concept of digital-era governance to reveal that e-participation can provide the public and other social actors with a good information environment and convenient political participation channels, reduce the insecurity of political participation, and thereby ensure and develop a VA. This study further used the concept of digital-era governance to explain the theoretical mechanism by which e-participation promotes VA; that is, the public and other social actors can use e-information, e-consultation, and e-decisions to participate in public service delivery, policymaking, and the construction of political voices, thereby improving VA. This study also used OLS to further verify the validity of the theoretical analysis and the actual impact of e-participation on VA. The corresponding influence paths and regression coefficients are shown in . As a new form of participation, e-participation opens channels, broadens scope, and increases opportunities for public political participation, thus providing an effective tool for realizing VA. These findings echo the empirical findings of Leroux et al. (Citation2020) that a positive correlation exists between voter participation rates and the number of online voting tools and information programs offered by local governments. Similarly, Asher et al. (Citation2019) argued that e-petition systems can significantly enhance the relationship between the public and Parliament, allowing the Parliament to take greater account of the concerns expressed by the public in e-petitions in its decision-making.

However, scholars have raised concerns about the potential negative impact of e-participation on VA. Specifically, some governments use ICT to increase information monopoly over people, thus strengthening existing bureaucratic power, which hinders the full value of e-participation (Wong & Welch, Citation2004; Zou et al., Citation2023). Low levels of public democratic awareness and digital literacy may exacerbate the situation (Zhang et al., Citation2024). Consider democratic voting in national elections. Owing to the public’s low awareness of democratic participation and limited digital literacy, their ability to screen, select, process, and use information is insufficient, which may result in abstention or irrational voting behavior under information asymmetry (Ahmed et al., Citation2023; Hill & Alport, Citation2009). Another negative impact is that some interest groups can use digital technology to manipulate the electorate, undermining the legitimacy, science, and effectiveness of democratic elections and hindering the effectiveness of e-participation (Boulianne, Citation2020; Lowenkron, Citation2006). This is because e-participation must be embedded in the governance system to achieve substantive rather than procedural democracy. E-participation can only fully contribute to VA if a country’s governance system is democratic rather than controlled and governments are citizen-centred rather than authoritarian (Bertot et al., Citation2010; Lindquist & Huse, Citation2017; Waheduzzaman & Khandaker, Citation2022). Overall, this study supports the view that global e-participation promotes VA, and that e-information, e-consultation, and e-decision play active roles.

Second, the findings demonstrate regional heterogeneity, that is, the impacts of e-information, e-consultation, and e-decision on VA are more pronounced in LDCs than in developing and developed countries.

presents the impact levels in different types of countries. An efficient and orderly flow of information between governments and the public is the key to promoting VA. However, the level of digital government in LDCs is usually extremely low, and the functions of e-participation are limited due to the lack of telecommunication infrastructure and funds (Allen et al., Citation2020). Universally low digital literacy and excessive inter-regional or inter-population digital divide further hinder public access to e-information, leading to participation in government activities through e-consultation and e-decision (Parycek et al., Citation2017). The bureaucracies of LDCs are relatively closed and lack citizen-centric culture, making public political rights difficult to guarantee (Kneuer & Harnisch, Citation2016). These contextual factors impede the two-way flow of information between the government and the public. Nonetheless, there is room for improvement in e-participation and VA in the LDCs. The widespread deployment of e-participation as a low-cost and effective democratic tool, especially the e-information employed in LDCs, is crucial to facilitate two-way communication and the two-way flow of information between governments and the public, thus presenting a higher potential to enhance VA relative to other countries. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to empirically validate this view.

5.2. Practical implications

Based on the main findings and discussion, this study proposes practical implications for global e-participation in improving VA.

Regarding e-information, governments should strengthen the construction of an information infrastructure to crack the digital divide and increase the openness of government affairs. Moreover, to alleviate information asymmetry between governments and the public in the governance process, governments must accept public supervision through information disclosure, thereby forming open governments. In addition to enhancing information disclosure at the technical level, governments must improve the transparency of information related to their internal operational processes, policy formulation, and public service delivery from the institution, policy, and management perspectives.

Concerning e-consultation, governments should build and improve public consultation platforms to strengthen the links between themselves and the public. Apps such as social networks, instant chat software, short videos, and government service platforms, are needed to build communication channels between governments and the public (Grover et al., Citation2022; Li, Citation2016). This will enable the public to provide feedback and suggestions to governments in the process of policy formulation and decision-making, forming two-way communication and extensive supervision between governments and the public.

Regarding e-decision, governments need to build more inclusive e-decision platforms such as e-procurement, e-petitions, and e-voting to maximize the inclusion of the common will of the public during policy revision, legislation, and elections. The public can participate in government decision-making through e-government platforms, for example, by holding online hearings and soliciting suggestions for policy changes to enhance direct public participation in decision-making.

The construction of e-participation requires adaptation to each country’s level of development. Countries with low levels of economic development should focus on strengthening e-information and e-consultation. This is because two-way communication between governments and the public through government information disclosure and the use of existing platforms usually does not require a high cost or digital technology level, which is easier for the least developed countries to achieve. Specifically, it is essential to strengthen information infrastructure construction and promote the widespread use of online devices, such as computers, iPads, and smartphones.

An open and democratic political system must guarantee the effectiveness of e-participation. If governments are unwilling to interact fully with citizens, fearing that their control will be weakened, these technologies will function only as one-way communication channels without the ability to improve e-participation, public accountability, or public service delivery (Bolívar, Citation2017). Thus, Political systems and bureaucracies must shift from authoritarian to citizen-centric and use e-participation platforms to achieve two-way communication between governments and the public.

5.3. Contributions

In summary, this study explored the path of e-participation for VA at the theoretical and empirical levels and presented targeted theoretical and practical implications for safeguarding the democratic efficacy of e-participation, contributing to the realization of good governance in the digital age. The main contributions of this study are as follows.

This study focused on the rapid development of ICT using the concept of digital-era governance to explain the impact mechanism of e-participation on VA, responding to hot issues in the practice of e-participation, and expanding the theory and practice of political participation and democratic development in the digital age.

On this basis, this study also addressed the phenomenon of the uneven development of e-participation worldwide and further analyses regional heterogeneity in the impact of e-participation on VA, thus providing targeted guidance for designing e-participation in countries at different levels or stages of development.

At the practical level, e-participation is a global trend in public administration, and this study recommended ways for developing VA with the help of ICT.

5.4. Limitations and future research

This study has some limitations. Future research can be conducted from the following aspects. First, the scope of e-participation is vast, and, to our knowledge, there is no universally accepted international index of e-participation that is truly all-encompassing. The dataset from the UN has been widely used and successfully published in many high-level papers, and is recognized as a reliable source of data, although it has been questioned by some researchers (Kabanov, Citation2022; Pirannejad et al., Citation2019). Future research should consider using case studies and questionnaire methods, or designing a better e-participation index to improve the comprehensiveness of the explanatory variables. Second, global e-participation is developing rapidly and may have different impacts on VA at different stages. To ensure data integrity, this study only conducted a cross-sectional study where individual effects were considered for regional comparative analysis, and the OLS model could not control for the confounding effects of time effects. Future research should collect sufficient annual data and sample size to explore the impact of global e-participation on VA at different times. Third, the impact of e-participation on VA is due to many factors that vary from time to time and from place to place, and little is known about the interrelationships between these factors. Future research needs to look beyond the technical or project level to social and institutional level changes with the help of other complex estimation models, such as mixed-effects models, for a detailed analysis. Fourth, this study revealed through quantitative research that e-participation can positively influence VA, and the results are supported by robustness tests. Unfortunately, mathematical statistics alone do not help understand causality and inevitably have an endogenous flaw of insufficient explanatory power. In the future, expert interviews, surveys, literature analyses, comparative analyses, and case studies can be used to clarify the mechanisms of influence.

Author contributions

Z.M.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Project Administration. W.Z.: Methodology, Data Curation, Writing-Original Draft. Q.Z.: Conceptualization, Data Curation, Writing-Reviewing and Editing, Supervision. W.D.: Validation, Writing-Reviewing and Editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analysed during the current research available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We also acknowledge the reviewers and editors of the Information Technology for Development for helping improve this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ahmed, S., Wang, Y., & Tully, M. (2023). Perils of political engagement? Examining the relationship between online political participation and perceived electoral integrity during 2020 US election. Journal of information technology & politics, 1, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/19331681.2023.2275255

- Akmentina, L. (2022). E-participation and engagement in urban planning: Experiences from the Baltic cities. Urban Research & Practice, 624–657. https://doi.org/10.1080/17535069.2022.2068965

- Alcaide Muñoz, L., & Rodríguez Bolívar, M. P. (2021). Different levels of smart and sustainable cities construction using e-Participation tools in european and central asian countries. Sustainability, 13(6), 3561. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13063561

- Alford, J., & Hughes, O. (2008). Public value pragmatism as the next phase of public management. The American Review of Public Administration, 38(2), 130–148. https://doi.org/10.1177/0275074008314203

- Allen, B., Tamindael, L. E., Bickerton, S. H., & Cho, W. (2020). Does citizen coproduction lead to better urban services in smart cities projects? An empirical study on e-participation in a mobile big data platform. Government Information Quarterly, 37(1), 101412. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2019.101412

- Alonso, G., & Castro, S. L.-D. (2016). Technology helps, people make: A smart city governance framework grounded in deliberative democracy. Smarter as the new urban agenda: A comprehensive view of the 21st century city (pp. 333–347). Springer.

- Androniceanu, A., & Georgescu, I. (2022). E-participation in Europe: A comparative perspective. Public Administration Issues, 5, 7–29. https://doi.org/10.17323/1999-5431-2022-0-5-7-29

- Asher, M., Leston-Bandeira, C., & Spaiser, V. (2019). Do Parliamentary Debates of e-Petitions Enhance Public Engagement With Parliament? An Analysis of Twitter Conversations. Policy & Internet, 11(2), 149–171. https://doi.org/10.1002/poi3.194

- Australia. (2022). Official Australian Government information. Available from: https://www.australia.gov.au/ [Accessed 2022/3/19].

- Bahrain’s Information and eGovernment Authority. (2022). Tawasul: Submit Your Case. Avaulable at: https://services.bahrain.bh/wps/portal/tawasul (accessed 20 March 2022).

- Becker, D., & Bendett, S. (2015). Crowdsourcing solutions for disaster response: Examples and lessons for the US government. Procedia Engineering, 107, 27–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proeng.2015.06.055

- Bertot, J. C., Jaeger, P. T., & Grimes, J. M. (2010). Using ICTs to create a culture of transparency: E-government and social media as openness and anti-corruption tools for societies. Government Information Quarterly, 27(3), 264–271. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2010.03.001

- Bolívar, M. P. R. (2017). Policy makers’ perceptions about social media platforms for civic engagement in public services. An empirical research in Spain. Policy Analytics, Modelling, and Informatics: Innovative Tools for Solving Complex Social Problems, 2018, E1–E1. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-61762-6_19

- Bonsón, E., Torres, L., Royo, S., & Flores, F. (2012). Local e-government 2.0: Social media and corporate transparency in municipalities. Government Information Quarterly, 29(2), 123–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2011.10.001

- Boulianne, S. (2020). Twenty years of digital media effects on civic and political participation. Communication Research, 47(7), 947–966. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650218808186

- Braga, L. V., & Gomes, R. C. (2018). Electronic participation, government effectiveness, and accountability. Revista do Serviço Público, 69(1), 111–144. https://doi.org/10.21874/rsp.v69i1.1017

- Bragazzi, N. L., Dai, H., Damiani, G., Behzadifar, M., Martini, M., & Wu, J. (2020). How big data and artificial intelligence can help better manage the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(9), 3176. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17093176

- Brazil. (2022). Noosfero. Available from: http://www.participa.br/ [Accessed 2022/3/19].

- Brewer, G. A., Choi, Y. J., & Walker, R. M. (2008). Linking Accountability, corruption, and government effectiveness in Asia: An examination of World Bank Governance Indicators. Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

- Brinkerhoff, D. W., & Wetterberg, A. (2016). Gauging the effects of social accountability on services, governance, and citizen empowerment. Public Administration Review, 76(2), 274–336. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12399

- Callen, T. (2016). Gross domestic product: An economy’s all. IMF. Available from: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/fandd/issues/Series/Back-to-Basics/gross-domestic-product-GDP [Accessed 23 February 2024].

- Chan, F. K. Y., Thong, J. Y. L., Brown, S. A., & Venkatesh, V. (2021). Service Design and Citizen Satisfaction with E-Government Services: A Multidimensional Perspective. Public Administration Review, 81(5), 874–894. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.13308

- Choi, H., Park, M. J., & Rho, J. J. (2017). Two-dimensional approach to governmental excellence for human development in developing countries: Combining policies and institutions with e-government. Government Information Quarterly, 34(2), 340–353. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2017.03.002

- Coelho, T. R., Cunha, M. A., & Pozzebon, M. (2022). Eparticipation practices and mechanisms of influence: An investigation of public policymaking. Government Information Quarterly, 39(2), 101667. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2021.101667

- David, L. B. (2020). E-participation: A quick overview of recent qualitative trends. United Nations, Department of Economics and Social AffairsWorking Papers, 163.

- Dunleavy, P., Margetts, H., & Tinkler, B. J. (2006). New Public Management Is Dead--Long Live Digital-Era Governance. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 16(3), 467–494. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/mui057

- Durkiewicz, J., & Janowski, T. (2020). Towards synthetic and balanced digital government benchmarking Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences.

- Eportugal. (2022). Your portol of public services. Available from: https://eportugal.gov.pt/home [Accessed 2022/3/19].

- Epstein, D., Newhart, M., & Vernon, R. (2014). Not by technology alone: The “analog” aspects of online public engagement in policymaking. Government Information Quarterly, 31(2), 337–344. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2014.01.001

- Escher, T., & Riehm, U. (2017). Petitioning the german bundestag: Political equality and the role of the internet. Parliamentary Affairs, 70(1), 132–154. https://doi.org/10.1093/pa/gsw009

- Garcia Alonso, R., & Lippez-De Castro, S. (2016). Technology helps, people make: A smart city governance framework grounded in deliberative democracy. In J. R. Gil-Garcia, T. A. Pardo, & T. Nam (Eds.), Smarter as the New Urban Agenda: A Comprehensive View of the 21st Century City (pp. 333–347). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-17620-8_18.

- Grover, P., Kar, A. K., & Dwivedi, Y. (2022). The evolution of social media influence - a literature review and research agenda. International Journal of Information Management Data Insights, 2(2), 100116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jjimei.2022.100116

- Gulati, G. J. J., Williams, C. B., & Yates, D. J. (2014). Predictors of on-line services and e-participation: A cross-national comparison. Government Information Quarterly, 31(4), 526–533. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2014.07.005

- Halachmi, A., & Greiling, D. (2013). Transparency, E-Government, and accountability. Public Performance & Management Review, 36(4), 572–584. https://doi.org/10.2753/PMR1530-9576360404

- Hanisch, M., Goldsby, C. M., Fabian, N. E., & Oehmichen, J. (2023). Digital governance: A conceptual framework and research agenda. Journal of Business Research, 162, 113777. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2023.113777

- Harrison, T. M., & Sayogo, D. S. (2014). Transparency, participation, and accountability practices in open government: A comparative study. Government Information Quarterly, 31(4), 513–525. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2014.08.002

- Hill, L., & Alport, K. (2009). E-Government Diffusion, Policy, and Impact - Advanced Issues and Practices. IGI Global.

- Hu, Q., & Zheng, Y. (2020). Smart city initiatives: A comparative study of American and Chinese cities. Journal of Urban Affairs, 43(4), 504–525. https://doi.org/10.1080/07352166.2019.1694413

- Ifinedo, P., Anwar, A., & Cho, D. (2021). Using panel data analysis to uncover drivers of E-Participation progress. Journal of Global Information Management, 29(3), 212–235. https://doi.org/10.4018/JGIM.2021050109

- Ingrams, A., & Schachter, H. L. (2019). E-participation opportunities and the ambiguous role of corruption: A model of municipal responsiveness to sociopolitical factors. Public Administration Review, 79(4), 601–611. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.13049

- James, O., & Petersen, C. (2018). International rankings of government performance and source credibility for citizens: Experiments about e-government rankings in the UK and the Netherlands. Public Management Review, 20(4), 469–484. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2017.1296965

- John, C. B., Paul, T. J., & Derek, H. (2011). The impact of polices on government social media usage: Issues, challenges, and recommendations. Government Information Quarterly, 29(1), 30–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2011.04.004

- Kabanov, Y. (2022). Refining the UN E-participation index: Introducing the deliberative assessment using the varieties of democracy data. Government Information Quarterly, 39(1), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2021.101656

- Karkin, N., & Janssen, M. (2020). Structural changes driven by e-petitioning technology: Changing the relationship between the central government and local governments. Information Technology for Development, 26(4), 837–855. https://doi.org/10.1080/02681102.2020.1742078

- Kaufmann, D., Kraay, A., & Mastruzzi, M. (2010). The worldwide governance indicators: A summary of methodology, data and analytical issues. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper, 5430(1), 1–28.

- Kennedy, R., & Scholl, H. J. (2016). E-regulation and the rule of law: Smart government, institutional information infrastructures, and fundamental values. Information Polity, 21(1), 77–98. https://doi.org/10.3233/IP-150368

- Kneuer, M., & Harnisch, S. (2016). Diffusion of e-government and e-participation in Democracies and Autocracies. Global Policy, 7(4), 548–556. https://doi.org/10.1111/1758-5899.12372

- Korea. (2022). National tax department. Available from: https://www.nts.go.kr/ [Accessed 2022/3/19].

- Kotina, H., Stepura, M., & Kondro, P. (2022). How does active digital transformation affect the efficiency of governance and the sustainability of public finance? The ukrainian case. Baltic journal of economic studies, 8(1), 75–82. https://doi.org/10.30525/2256-0742/2022-8-1-75-82

- Krassimira Antonova, Paskaleva. (2009). Enabling the smart city: The progress of city e-governance in Europe. International Journal of Innovation and regional development, 1(4), 405–422. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJIRD.2009.02273

- Leroux, K., Fusi, F., & Brown, A. G. (2020). Assessing e-government capacity to increase voter participation: Evidence from the U.S. Government Information Quarterly, 37(3), 101483. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2020.101483

- Li, Z. (2016). Psychological empowerment on social media: Who are the empowered users? Public Relations Review, 42(1), 49–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2015.09.001

- Lindquist, E. A., & Huse, I. (2017). Accountability and monitoring government in the digital era: Promise, realism and research for digital-era governance. Canadian Public Administration, 60(4), 627–656. https://doi.org/10.1111/capa.12243

- Lopez-Lopez, V., Iglesias-Antelo, S., Vazquez-Sanmartin, A., Connolly, R., & Bannister, F. (2018). E-government, transparency & reputation: An empirical study of Spanish local government. Information Systems Management, 35(4), 276–293. https://doi.org/10.1080/10580530.2018.1503792

- Lowenkron, B. F. (2006). Human rights, civil society, and democratic governance in Russia: Current situation and prospects for the future. Available from: https://xueshu.baidu.com/usercenter/paper/show?paperid=08a63fa4d8d97520131b1de315e2500f&site=xueshu_se&hitarticle=1 [Accessed 2022/3/19].

- Lu, J., & Luo, C. (2019). Development consensus in the Internet context: Penetration, freedom, and participation in 38 countries. Information Development, 36(2), 288–300. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266666919848815

- Maclean, D., & Titah, R. (2022). A Systematic Literature Review of Empirical Research on the Impacts of e-Government: A Public Value Perspective. Public Administration Review, 82(1), 23–38. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.13413

- Malodia, S., Dhir, A., Mishra, M., & Bhatti, Z. A. (2021). Future of e-government: An integrated conceptual framework. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 173, 121102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2021.121102

- Mao, Z., Zou, Q., Yao, H., & Wu, J. (2021). The application framework of big data technology in the COVID-19 epidemic emergency management in local government—a case study of Hainan Province, China. Bmc Public Health, 21(1), https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-12065-0

- Margetts, H., & Dunleavy, P. (2013). The second wave of digital-era governance: A quasi-paradigm for government on the Web. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences, 371(1987), https://doi.org/10.1098/rsta.2012.0382

- Matheus, R., Janssen, M., & Janowski, T. (2021). Design principles for creating digital transparency in government. Government Information Quarterly, 38(1), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2020.101550

- Mergel, I. (2014). Social media adoption: Toward a representative, responsive or interactive government? Proceedings of the 15th Annual International Conference on Digital Government Research, 2014, 163–170. https://doi.org/10.1145/2612733.2612740

- Meyerhoff Nielsen, M., & Millard, J. (2020). Local context, global benchmarks: Recommendations for an adapted approach using the UN E-Government Development Index as an example. The 21st Annual International Conference on Digital Government Research, 2020, 253–260. https://doi.org/10.1145/3396956.3396969

- Milakovich, M. E. (2012). Digital governance: New technologies for improving public service and participation. International Review of Public Administration, 17(2), 175–178. https://doi.org/10.1080/12294659.2012.10805235

- Norris, D. F. (2010). E-Government 2020: Plus ça change, plus c'est la meme chose. Public Administration Review, 70(S1), S180–S181. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2010.02269.x

- Oni, S., Oni, A. A., Ibietan, J., & Deinde-Adedeji, G. O. (2020). E-consultation and the quest for inclusive governance in Nigeria. Cogent Social Sciences, 6(1), 1823601. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2020.1823601

- Panagiotopoulos, P., Klievink, B., & Cordella, A. (2019). Public value creation in digital government. Government Information Quarterly, 36(4), 101421. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2019.101421

- Pánek, J., Marek, L., Pászto, V., & Valůch, J. (2017). The Crisis Map of the Czech Republic: The nationwide deployment of an Ushahidi application for disasters. Disasters, 41(4), 649–671. https://doi.org/10.1111/disa.12221

- Parycek, P., Sachs, M., Virkar, S., & Krimmer, R. (2017). Voting in E-Participation: A set of requirements to support accountability and trust by electoral committees. Electronic Voting: Second International Joint Conference, E-Vote-ID 2017, Bregenz, Austria, Springer International Publishing, Cham, 10615, 42–56. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-68687-5_3

- Paskaleva, K. A. (2009). Enabling the smart city: The progress of city e-governance in Europe. International Journal of Innovation and Regional Development, 1(4), 405–422. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJIRD.2009.022730