ABSTRACT

Twentieth-century historians of science emphasised the apparent connection between puritanism and experimental natural philosophy in mid-seventeenth-century England, but revisionist scholarship exposed the incorrect religious taxonomies undergirding this thesis. As both a staunch puritan and a well-connected figure in scientific networks, Ralph Austen provides an opportunity to re-examine the thesis. A horticulturalist, cider manufacturer and lay theologian based in Oxford from 1646 until his death in 1676, Austen was a friend and collaborator of Samuel Hartlib and Robert Boyle. He was also a pious puritan, steeped in Reformed divinity, and friends with premier Interregnum puritans, including John Owen. Austen’s life and career demonstrate that Baconian aims to reform learning could happily go hand-in-hand with, and be inspired by, puritan ideals, though they hampered his reputation in post-Restoration natural-philosophical circles. At the same time, via Austen we learn that puritan theologians responded positively to Baconian ideas, something hitherto underrepresented in the literature.

To the enthusiastic projectors of seventeenth-century England, cider was one of the keys to national betterment. As John Evelyn saw it, beer may have been pleasurable, but it repaid such pleasures ‘with tormenting Diseases’; by contrast, cider was ‘one of the most delicious and wholesome Beverages in the World.’ Writing the preface to Pomona, a work on fruit trees and cider production appended to his Sylva (1664), Evelyn was effusive in praising the benefits of ‘our Native Liquor’, ‘good Cider’: planting fruit trees for cider production would provide employment for the poor, protection from trade embargoes, fresher air, and a beverage that could comfortably surpass the finest of French wines.Footnote1 But at the time of Pomona’s publication, English cider was a regional phenomenon, restricted mostly to the western counties of Herefordshire, Staffordshire, and Worcestershire, a problem that Evelyn and his fellow cider enthusiasts sought to solve. In 1676, the west country clergyman and cider aficionado John Beale (bap. 1608, d. 1683) published Nurseries, Orchards, Profitable Gardens, and Vineyards Encouraged, a short tract composed of three letters addressed to Henry Oldenburg, the secretary of the Royal Society. Noting that ‘[t]he great Example of his Majesty, and of our Nobility, and generally of our chief Gentry’ in planting fruit-trees (and improving husbandry more generally) was said to have reached its limits ‘about Cambridge’, his stated aim in this piece was to encourage the creation of a cider trade in the university town, just as the drink had been brought to Oxford a few decades before.Footnote2

Oldenburg joined Beale in this effort. In September 1676, around the time Beale’s Nurseries was published, he wrote to Isaac Newton proposing a scheme for the planting of fruit trees. Newton’s reply detailed the horticultural situation of the town: ‘there are some gentlemen that of late have begun to plant [apple trees], and seem to incline more and more to it’, though Cambridge lacked a ‘professed nurseryman’.Footnote3 Newton wrote to Oldenburg a few weeks later, desiring his ‘procuring a recommendation of us to Mr Austin the Oxonian planter’, who seems to have been suggested by Oldenburg. Newton wanted this cider expert to furnish himself and his Cambridge collaborators ‘wth ye best sorts of Cider-fruit-trees’: ‘30 or 40 Graffs’ for their first foray into cider cultivation.Footnote4 Via Oldenburg, Newton was able to make contact with the Oxford man, but he had died before any serious enterprise was afoot.Footnote5

The ‘Oxonian planter’ in question was Ralph Austen, the man almost single-handedly responsible for bringing cider production to Oxford, and thus an obvious recommendation for Oldenburg to have made. Austen is not well-known today, but he was an influential figure in the reformist agricultural movements of the mid- to late-seventeenth century.Footnote6 A horticulturalist who spent more than forty years specialising in arboriculture, Austen’s major work, A Treatise of Fruit-Trees, was published by the Oxford stationer Thomas Robinson in 1653, and proved popular enough for expanded editions to appear in 1657 and 1665. He was a central figure in agricultural correspondence networks, particularly in the 1650s, when he formed a close collaboration with Samuel Hartlib (c. 1600–62), the Prussian intelligencer. Austen became Hartlib’s mouthpiece in Oxford, England’s most prominent university town, where Hartlib and his acolytes hoped to gain the ear of the puritan divines intruded upon the former royalist headquarters. Via Hartlib, Austen also collaborated with Walter Blith (bap. 1605, d. 1652), the author of the influential husbandry manuals The English Improver (1649) and The English Improver Improved (1652);Footnote7 and Beale, with whom he shared apple tree grafts and debated the merits of different fruit varieties for cider production (at times rather bitterly). In Oxford, Austen formed a close relationship with Robert Sharrock (bap. 1630, d. 1684), the horticulturalist and natural lawyer, and Robert Boyle (1627–91), who helped distribute some of his later writings, and through whom he received the support of Oldenburg. But it was by his writings, particularly the Treatise, that Austen was best known: the gentleman farmer John Worlidge (d. 1693) acknowledged his debt to Austen in his popular Systema Agriculturæ (1669), while Evelyn’s Sylva was almost certainly influenced by him.

These networks are of interest to historians of science, but they represent only one side of Austen’s concerns. Published alongside the first two editions of the Treatise was a parallel work, which Austen regarded as being just as significant: The Spiritual Use, of an Orchard; or Garden of Fruit-Trees. This text contained ‘diverse Similitudes between Naturall and Spirituall Fruit-trees’, with Austen using his horticultural know-how to illustrate, by metaphor, his particular brand of Calvinistic piety. For Austen was very much a puritan, and he was close, both relationally and as a coreligionist, to the divines intruded upon many of Oxford’s colleges: John Owen (1616–83), Thankful Owen (1620–81), and Henry Langley (1610/11–79), to name a few. (He was also connected to the Cromwellian regime through his kinship to Henry Ireton, Cromwell’s son-in-law, who was his mother’s first cousin – a connection he capitalised on in his search for patronage.) This makes Austen an apt figure for exploring the relationship between the experimental natural philosophy of the Restoration era and the politico-religious climate of Cromwellian England. From Robert Merton in the 1930s to Charles Webster in the 1970s, many historians of science claimed that ‘puritanism’ provided the seedbed for the scientific enterprises of the Restoration, until this interpretation was challenged by historians objecting to the imprecise religious taxonomies used to undergird this thesis.Footnote8 According to critics of the puritan-and-science thesis, experimental natural philosophy was eminently ‘latitudinarian’ in character;Footnote9 and this revisionist account has been upheld by more recent literature, which continues to present the non-puritan character of the early Royal Society. But one by-product of this debate was to obscure those figures involved in mid-century natural philosophy who were ‘puritan’ in character, according to the more accurate classifications of modern scholarship. This obscurity has hardly been helped by the historiography of puritanism, or scholarship on individual puritan divines, which likewise engage minimally with the history of science, instead examining puritan figures for their politico-religious significance, or their relevance to the history of theology.Footnote10

In Austen, we can begin to fill these historiographical lacunae. The eagerness of his Baconianism was matched only by his adherence to the staunchest of puritan principles, and to him the two chimed neatly. In this sense, something of the weight of Webster’s thesis can be snatched back from revisionist hands. But Austen’s very obscurity, and the more than ambiguous attitudes towards him amongst the scientific establishment – particularly after the Restoration – place limits on any quick revival of the ‘puritanism-and-science’ thesis. Puritanism certainly played a part in the reform of natural philosophy, but it was a far smaller part than that attributed to it by the Weberian historians of the twentieth century. More illuminating is the light Austen sheds on the response of Reformed divines to the developing natural philosophy of mid-century England, a topic that has been underexplored in the literature on English puritanism. The rather extensive extant materials relating to Austen reveal someone at the centre of the puritan establishment, through whom ideas about the reform of learning and natural philosophy were communicated to its kingmakers. In these cases Austen provides us with a picture of puritan responses to the new science – one that the printed sources usually relied upon have not been able to divulge. More than we might expect from divines who were, by and large, of an Aristotelian-scholastic hue, figures like John Owen and Henry Langley approved of and encouraged the reform of natural philosophy. It is clear that puritanism did not cause experimental natural philosophy in any meaningful sense. But these divines, in their quiet approbation of it – so different to the response of many continental Reformed divinesFootnote11 – played a part in the extraordinary developments in natural philosophy that took place in the Cromwellian years, and on into the Restoration era.

I

Ralph Austen was born in Leek, Staffordshire, in c. 1612.Footnote12 Little is known of his background or upbringing. He seems to have come from a yeoman family, though apparently of some means: Walter Blith pointed his readers to ‘an Oxford Gentleman, called Ra. Austen’,Footnote13 a descriptor Austen himself would use in later life;Footnote14 and his family home was a property built in the ruins of Dieulacre Abbey, where, later in the century, Robert Plot’s friend Thomas Rudyerd would live.Footnote15 Nothing is known of his schooling, though his writings reveal a good knowledge of Latin and classical poetry, suggesting a fairly thorough grammar school education; he also had a basic knowledge of scholastic philosophy.Footnote16 On his account, he started work in husbandry in around 1633;Footnote17 by 1636, he is recorded as a husbandman in Hunningham, around seventy miles south of his childhood home.Footnote18 At some point, probably at the close of the first civil war, he settled in Oxford. It is unclear what brought him to the university town, but he wasted no time ingratiating himself with the newly-established authorities, being appointed deputy registrar to the parliamentary visitation of the university in 1646, and registrar thereafter.Footnote19 It was during these early years in Oxford that Austen became acquainted with the influential intelligencer Samuel Hartlib. We do not know when their friendship began. The first extant letters they exchanged, dating from early 1652, already suggest a degree of familiarity, so it is unlikely that they mark the beginning of their relationship; but he was not a well-known figure in the Hartlib circle in 1652, when Hartlib wrote to Walter Blith warning him not to tread on the Oxonian’s toes. The Warwickshire-based farmer had been preparing a chapter on fruit trees for the updated edition of his work, The English improver improved (1652), only to desist once ‘Mr. Samuel Hartlib, that publike spirit’ had alerted him that Austen ‘had finished a Work fit for the Presse, of approved experiments in Planting late Fruit, from better Rules than have hitherto yet been published’.Footnote20

Austen seems to have started work on the book in question, A Treatise of Fruit-Trees, sometime in 1651. Wood reports that at the end of July 1652 Austen ‘was entred a Student into the publick Library, to the end that he might find materials for the composition of a book which he was then meditating’, something that is confirmed by the Bodleian’s record of readers’ admissions.Footnote21 But this ‘meditating’ was already far enough along in February 1652 for a full manuscript to be sent to Hartlib via Austen’s friend Benjamin Martin, who worked for William Lenthall, the Speaker of the Commons (probably at his property in Burford, nineteen miles west of Oxford).Footnote22 We can safely assume, then, that the bulk of the work, published in the early months of 1653, was formed before Austen started his reading project in the Bodleian – especially given that there is no indication in his detailed correspondence with Hartlib that the book underwent any significant revisions. This accords with Austen’s own description of his education in fruit-tree husbandry. In the preface to A Treatise of Fruit-Trees he relates that his experience in the craft by that point spanned ‘the space of Twenty yeares, and more’, with his knowledge being both practical and literary: ‘I have seen,’ he assured his readers, ‘the best Workes, both of Ancient, and Late Writers upon this Subject, and have learned from them what I could, for accomplishment of this Art’.Footnote23

Principal among such writers was Francis Bacon, ‘a Learned Author’ whose influence litters Austen’s corpus, and on whose Natural History Austen produced a commentary in 1658. In Bacon, Austen found a writer whose interest in husbandry chimed with his own: Bacon had defended his treatment of ‘Plants or Vegetables’ in Sylva sylvarum (1627), for instance, by asserting that such matters ‘are of excellent and generall Vse, for Food, Medicine, and a Number of Mechanicall Arts.’Footnote24 But as useful as this may have been to husbandry in particular, Austen imbibed the heart of the Baconian project in a thoroughgoing fashion – indeed, several of the core conceptual framings of his work he lifted wholesale, and unapologetically, from Bacon. Perhaps most importantly, he consistently stressed the importance of practical experience and ‘experiments’ over and against a speculative or bookish approach to nature. After assuring his readers of his horticultural expertise, Austen dealt a typically Baconian blow at too scholarly an approach to the subject:

Some who have taught this Art of Planting Fruit-trees, have been in it (I conceive) only Contemplative men, having little, or no Experience in it: so that in many things they have erred, and that grossely, as shall appeare in due place.

Citing Bacon’s Advancement of Learning, Austen then argued that such ‘speculative men’ had failed to realise that, important as book-learning is, it is ‘Experience’ that enjoys pride of place as ‘the Perfecter of Arts, and the most sure, and best teacher in any Art’. Speculation has a place, but it must go hand-in-hand with experience in the pursuit of true, practicable knowledge. Indeed, attempting go without one or the other is to do more than just shoot oneself in the foot: since ‘Contemplation and Action are the two Leggs whereon Arts runne stedily and strongly … the one without the other, can but hop, or goe lamely.’Footnote25

These principles did not mean that Austen rejected the tenets of the more traditional Aristotelian physics in toto. In at least two places in his corpus, he drew upon Aristotelian maxims to explain his arboricultural theories. Commenting on Bacon’s Natural History, he explained that the efficacy of grafts from good trees came about since ‘every twig, graft, and bud, hath the nature of the whole tree in it, perfectly’, just as ‘the soule in the body, which is tota in toto, & tota in qualibet parte’.Footnote26 This doctrine, which Henry More would later dub ‘holenmerism’, was common in scholastic-Aristotelian treatments of the soul.Footnote27 Similarly, in the first edition of the Treatise, Austen had defended his theory of the ascension of sap in trees on the basis of the Aristotelian maxim (originally articulated in the Politics) that ‘Natura nil agit frustra, nature does nothing in vaine’: and it would be needless, Austen argued, for nature to cause sap to ascend, only to cause it then to descend again.Footnote28 Austen’s Baconianism, then, was less about an outright rejection of Aristotelian ideas than a commitment to the primacy of experience over bookishness, and a utilitarian vision of the advancement of learning.

The mixture of Aristotelian doctrines with Baconian methods was hardly unique. George Hakewill’s influential Apologie of the Power and Providence of God (1st ed. 1627, 2nd ed. 1635) made clear its debt to Bacon’s optimism about the augmentation of the sciences from the off, with a thinly-veiled allusion to Bacon’s anti-Aristotelian Masculine Birth of Time, an unfinished treatise that had been circulating since c. 1602.Footnote29 Yet Hakewill was no anti-Aristotelian: indeed, he retained belief in the four elements, and in the Apologie ‘his central thesis is a reaffirmation of the changeless Aristotelian heavens’.Footnote30 To this we could add the example of William Twisse, zealous acolyte of the Stagirite who nonetheless expressed his approbation of Bacon’s reading of the apocalyptic prophecy of Daniel 12:4 in his preface to the English translation of Joseph Mede’s Clavis Apolcalyptica (1643).Footnote31 Like Hakewill and Twisse, Austen interpreted Bacon’s intellectual project as bothering itself less with the subtleties of metaphysics and epistemology than with a utilitarian vision of human betterment brought about through the improvement of man’s relation to the natural world. What mattered was not Aristotelianism or anti-Aristotelianism, but the advancement of learning.

The stress on experience bore much fruit for Austen’s work. He was able to produce detailed instructions on nursery management and fruit production that made the Treatise, in Webster’s words, ‘the most systematic and detailed treatment of this subject yet published in England.’Footnote32 The contribution of which Austen was most proud, at least in scientific terms, was his claim to have proven the ascension of sap in trees. Robert Sharrock, fellow of New College, writing the preface to Austen’s Observations upon some part of Sr Francis Bacon’s Natvral History in 1658, noted that many would be offended by ‘his refusall to attribute many effects to the descention of Sap’. But this was ‘a vulgar Error’, and, once Austen had at last convinced Sharrock as much, he encouraged the horticulturalist ‘to publish his arguments to the contrary’.Footnote33 He had in fact already done so, in his original Treatise of 1653. Noting that ‘[t]his Opinion of descention of sap in Trees is an old Error, of many yeares standing, and is radicated in the Minds of most men’,Footnote34 Austen produced a stream of arguments in its refutation. It would be needless, he asserted, for nature to cause sap to ascend, only to cause it then to descend again, and ‘Natura nil agit frustra, nature does nothing in vaine’. Similarly, he dismissed the popular view that the cold causes the descent of sap, since ‘Cold never causeth sap to stir, but to stand, or move slowly.’ Making an argument from experience, he appealed to the process of leaves becoming ‘contracted, and wrinkled’ once cut loose from trees, which happens because they are not being replenished by the ascension of sap from the roots.Footnote35

Other Baconian tenets feature heavily in Austen’s work. A tireless pursuit of practical knowledge was to be a bulwark of Instauratio Magna, Bacon’s utopian vision for the triumph of man over nature. Though proud of his own achievements, the same restlessness pervades Austen’s project. His claim to Hartlib in April 1652, a year before the final sheets rolled off Thomas Robinson’s press, that his work would be ‘capable of additions of new Experiments from yeare to yeare’ might have seemed premature, or somewhat far-fetched,Footnote36 but Austen remained true to his word when he published an updated Treatise of Fruit-Trees in 1657.Footnote37 Despite the considerable experience he had already acquired by the time he published the first edition, the updated sections in 1657 showed Austen to be a constant learner. In 1653, when providing instructions for the beginning of a nursery, Austen had advised that seed plants could be left on their beds to ‘grow there a yeare longer, and then be transplanted’.Footnote38 In the 1657 edition of the Treatise, he removed this sentence, inserting in its place the stipulation that all seed plants be removed from their original beds after ‘but one sommers growth from the seed … though they be never so small’. Having detailed the advantages that could be gained thereby, he added a cautionary note, in autobiographical form: ‘This is very considerable, and therefore observe it: I underwent great inconveniences when I came to Removing, before I found out this observation.’Footnote39 Those inconveniences he presumably experienced in the interim between the two publications, and was thus quick to incorporate his solution into the latter. The same goes for a variety of small additions in the second edition of the text, many of them marginalia, such as recommendations for the storing of apricot stones and advice for the protection of seeds against mice,Footnote40 recommendations of pear types for perry production,Footnote41 the size at which ‘young grafted Trees’ should be removed from a nursery,Footnote42 the spacing between newly-planted trees,Footnote43 and new material on the choice of apples for cider and the best methods for its production.Footnote44

Nor did 1657 mark his final word on the matter. In 1658 he published Observations upon some part of Sr Francis Bacon’s Natvrall History, a critique of Bacon’s Sylva sylvarum that was, ironically enough, his most stridently Baconian text. The text arrived at a time when Austen was having increasing contact with that other great Hartlibian horticulturalist, the clergyman and virtuoso John Beale. Their correspondence, begun in 1656, centred on the question of which apple varieties were best for making cider. In the 1657 edition of the Treatise Austen had recommended the use of domesticated apples already acclaimed as table fruits: pearmains, pippins, and especially Gennet Moyles.Footnote45 But Herefordshire, the county of Beale’s birth and upbringing, had become known for its cider made from wild apples, particularly a variety known as the Red-Streak, pioneered by Lord Scudamore. Writing in September 1658, Austen protested against Beale’s approbation of the Red-Streak: ‘Pippins & Peare Mains makes [sic] far better Cider then wilde apples,’ he claimed, since cider made from ‘wilde harsh fruit … is found to bee somewhat harsh & hard’.Footnote46 But Beale’s response, asserting the rich taste of cider made with Red-Streaks, as well as the speed of their growth and their plentiful yield,Footnote47 seems to have changed his mind; only a few weeks later, with the publication of Observations, Austen included the ‘Redstreake’ alongside the original selection of apples he had listed to Beale, as amongst the varieties able to produce ciders that could rival French wines.Footnote48

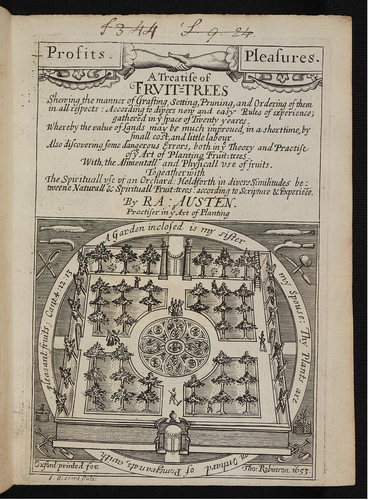

This urge for constant improvement was driven by an attractive vision: the increasing land yields, prolongation of human life, and marriage of pleasure and profits dreamt of in Bacon’s utopian project. The frontispiece of Austen’s Treatise () made these aims clear at the outset. Produced by the engraver John Goddard (whom Austen reckoned ‘a man … given to misspend his time in drinking, though an excellent workman’Footnote49), it depicted the hand of ‘Profits’ clasping that of ‘Pleasures’. The ‘profits’ that could be gained through fruit cultivation he would go on to rhapsodise throughout the book: a garden of fruit trees brought increase to estates, health to the body, long life, greater knowledge, a lasting name, and alms for the poor, alongside the pleasures of the senses.Footnote50 The prolongation of life was particularly singled out by Austen, and defended by recourse to the Book of Proverbs and Bacon’s History of Life and Death.Footnote51

Figure 1. The frontispiece of Austen’s 1653 Treatise of Fruit Trees. Reproduced by kind permission of the Master and Fellows of Trinity College, Cambridge.

All these features of Austen’s project marked him out as thoroughly Baconian. And, true to the original genesis of Bacon’s vision, his efforts towards the betterment of husbandry were not the work of an isolated maverick. Just as Bacon’s vision for ‘the enlargement of the bounds of human empire, to the effecting of all things possible’ in the New Atlantis required the collective expertise of the Elders of ‘Salomon’s House’,Footnote52 so Austen and his fellow Interregnum Baconians scurried about their work from a communal footing, built upon a nationwide network of correspondence. We have already seen as much in the aforementioned comments of Blith, who worried that Austen’s ideas would be less widely disseminated without him holding back his own material on fruit trees.Footnote53 There was nothing disingenuous about these comments: Blith even offered to arrange the printing of Austen’s work in London, and via Hartlib sent Austen a copy of his Improver Improved (1652).Footnote54 Blith’s comments on Austen’s forthcoming work acted as something of an ‘advertisement to the reader’, which Hartlib very deliberately built upon later in the year, when he published an anonymous treatise on fruit trees titled A Designe for plentie (1652). This little work was merely an amuse-bouche meant to stir up anticipation for Austen’s weightier tome:

Such as have perused Mr. Blithe’s Improver improved … will meet with a promise made concerning this Treatise of Master Austin’s, which now he is putting to the Presse, as by his own Letter written in November last 1652 he doth informe me: therefore I intend in this Preface and by this Treatise, as by a small taste of so good a matter, both to raise thine appetite and quicken thy desire to see that larger Work, and to stay thy stomack a little till it come forth …Footnote55

By the time Austen’s book found its way to booksellers, then, demand had been cultivated by this collective effort, something he duly acknowledged in his dedication to Hartlib.Footnote56 Even Thomas Robinson, the Oxford bookseller, collaborated, offering Hartlib as many copies of the Treatise as he desired, at a rate substantially below the usual stationer’s price – on the proviso that he didn’t tell ‘Mr Royston’, the London bookseller responsible for distributing the work in the capital.Footnote57

The Treatise was a collective effort, then, typical of Hartlib’s many schemes for improvement. But though Hartlib had been Austen’s foremost mentor and correspondent for a number of years, it was not long after the publication of the second edition of the Treatise that Austen’s intellectual centre of gravity began to shift away from him. In part this seems to have been due to the failure of Hartlib’s patronage. Austen’s repeated attempts to get parliament, or indeed Cromwell, to take notice of his scheme for national fruit tree planting were channelled via Hartlib, who seems to have been singularly inept at making anything come of them. Austen had also entrusted Hartlib’s son with £100, apparently for some business transaction on his behalf.Footnote58 But Hartlib junior not only failed to use the money as instructed, but ignored Austen’s repeated pleas about the matter.Footnote59 Austen’s patience snapped in September 1655, nearly a year after he had first sent the money, when he complained to Hartlib senior that all he sought was ‘the common Iustice & equity that is distributed even among the Turks’. This letter goes on to criticise, in considerable detail, Hartlib’s newly-published Legacy of Husbandry (1655), accusing the German of erring in ‘ordinary, & common things’,Footnote60 giving the impression that Austen was also angry with Hartlib himself.

The diminution of his relationship with Hartlib coincided with a new and more powerful source of patronage, one that must have seemed a precious providence to Austen. Sometime around late-1655 or early-1656, Robert Boyle moved to Oxford, setting up in rooms on the high street near University College.Footnote61 It is unclear how Boyle and Austen first met. Perhaps Hartlib had arranged their acquaintance, but it is equally likely that Robert Sharrock, the natural philosopher based at New College, encouraged the connection. Charles Webster has claimed that Austen was Sharrock’s ‘close friend’, and indeed that the budding botanist collaborated with Austen in the publication of his 1653 Treatise.Footnote62 While it is not clear whether Sharrock contributed anything to the text of the Treatise, he did note in his prefatory epistle to Austen’s 1658 Observations that he had read it, and Austen’s subsequent works, prior to publication, remarking that ‘THE Author of this piece has alwaies thought fit … to give me leave some time before every impression to make a judgment of what in this nature he has published.’ Textual clues suggest that this process indeed began before Austen’s first work appeared: Sharrock claims that he had ‘alwaies encouraged [Austen] to publish his arguments’ as to the movement of sap in trees, something which he had done with much clamour in the first edition of the Treatise.Footnote63 Almost definitely, then, Sharrock was a fairly longstanding acquaintance of Austen. But Sharrock was also close to Boyle, publishing his only scientific text at the latter’s instigation,Footnote64 and supervising the publication of his works in Oxford while the more eminent scientist was away from the city periodically between 1659 and 1661.Footnote65

It did not take long for Austen to strike up an enduring collaboration with Boyle. Austen clearly relished the opportunity posed to him by a reform-minded natural philosopher with connections to some of the most powerful landowners and politicians in the nation, noting in the dedicatory epistle to the Observations his gratitude that Boyle had ‘been pleased to honour [him] with [his] acquaintance’.Footnote66 This deferential language, apt for a yeoman’s son addressing a member of one of the nation’s wealthiest noble families, belied the closeness of their collaboration. Michael Hunter has surmised that ‘Boyle almost certainly encouraged’ the publication of Austen’s work, and indeed that the format of the text, presented as a refinement of Bacon’s Sylva sylvarum, ‘echoes [Boyle’s] Certain Physiological Essays’ of 1661, which Boyle had written in the mid- to late-1650s, and which presumably Austen had seen in manuscript.Footnote67 Doubtless Boyle did have a serious impact on Austen’s intellectual trajectory, but it is also possible that the influence was reciprocal. Anthony Wood thought as much, when he later recorded not only that Austen’s Treatise ‘was much commended for a good and rational piece by the honorable Mr. Rob. Boyle’, but that Boyle ‘did make us of it in a book or books which he afterwards published’.Footnote68 It is possible that Wood was thinking of the connection already noted, between Austen’s 1658 work and Boyle’s Certain Physiological Essays, reading off the publishing history a simple assumption of the direction of intellectual influence. But he could also have had in mind Austen’s work on the movement of sap, something which, as we have seen, he advertised widely, and a topic which Boyle incorporated into the discussion of van Helmont’s theory of water as fundamental matter in his Sceptical chymist of 1661.Footnote69

Despite the significance of Austen’s Observations to his arboricultural project, he made no mention of it in his correspondence with Hartlib. It is possible that letters discussing the work are no longer extant in the Hartlib Papers; but it is striking that Hartlib, who had been so involved in the publication of Austen’s original Treatise – receiving the autograph manuscript,Footnote70 as well as plenty of printed copies to distribute – should have received copies not at the hand of Austen but of Boyle.Footnote71 By that point, Boyle had become a conduit between the two. Already in March 1658, Hartlib had sent a letter to Austen via Boyle, whom he asked to convey his apologies for the failure of his entreaties to the Lord Protector.Footnote72 And in November 1659, Hartlib asked Boyle to send him Austen’s response to a paper by Oldenburg (presumably on fruit trees; it is not extant).Footnote73 But Hartlib remained a useful contact for Austen, especially when the political turmoil of the Restoration left him estranged from scientific networks, as a puritan deeply implicated in the Cromwellian regime. Sometime in the early summer of 1660, Hartlib had notified Austen of a secret scientific society that was forming.Footnote74 But Hartlib appears to have been guarded in the information he divulged to his erstwhile confidant. He was eager enough in December 1660, when writing to John Worthington about the nascent Royal Society, with its ‘meeting every week of the prime virtuosi’.Footnote75 But one of Austen’s final letters to the German, dating from March 1661, makes clear how little his old friend had been informing him of the matter. ‘Concerning the invisible society mentioned,’ Austen observed (perhaps an allusion to Boyle’s ‘Invisible College’ of the 1640s),Footnote76 ‘I hartily wish they may at last proue visible, for the publique good’. But their continued invisibility, at least to Austen, had left him incredulous, and he expressed doubt ‘that there should be such men upon the Earth; who really intend such things; seeing (for ought I know) it is without President in any age of the world’.Footnote77 By this point Austen was discouraged, and dejected. Despite a half-hearted plea to Hartlib in May 1661 that they ‘reviue the remembrance of our Ould designe’,Footnote78 his words in March of that year had already spoken volumes as to waning vitality of his project:

I haue beene at so much expences in sending, & receaving Letters for aboue this 7 yeares, & in giving, & distributing of Books both in the Citty & Country, about this businesse that I am aweary of it, & discouraged; & indeede disabled, reaping no fruit after so much seede sowen …Footnote79

Even Boyle, whom he counted his ‘very good friend’, was holding off on what he had purportedly promised Austen – presumably the commendation to the powers that be that Austen so desired, and had approached Boyle for in October 1658.Footnote80 At the Restoration, Austen was finding himself out in the cold: the political project in which he had placed so much hope crumbling before his eyes, and his once-cooperative colleagues reticent to engage with him. The dream of an Edenic England must have seemed far off.

II

But Austen’s greatest discouragement at that time would have been religious. For his arboricultural project was wrapped up in an eschatological hope that was decidedly Calvinistic and puritan – and Austen, like many of his coreligionists who had put such hope in the English republic, must have been shaken by the failure of designs that had been assumed to enjoy providential favour. It is this side of Austen – the zealous, utopian-minded puritan – that is foregrounded in the most in-depth study of him to date, undertaken by Charles Webster in his The Great Instauration (1975). Webster’s thesis, the most sophisticated articulation of an idea that had its roots in the work of R.H. Tawney and Robert K. Merton, was that puritanism played a significant role in the development of early experimental science. Naturally, this rested on taxonomical foundations – Webster and his followers needed to show that their scientists really were ‘puritans’. But religious taxonomies have long proved vexing to historians of seventeenth-century England, as the long debates over the nature of ‘puritanism’ make abundantly clear.Footnote81 Webster, a historian of early medicine and science, was naturally hampered in wading into such territories, and his detractors duly took advantage of the analytical impotence of a definition of puritanism broad enough to include John Wilkins and John Owen – arch-nemeses in Interregnum Oxford – as religious bedfellows.

The same kind of taxonomical reclassification that Barbara Shapiro undertook in her work on John Wilkins could equally be applied to Samuel Hartlib and his circle, as Shapiro herself alluded to.Footnote82 At one level, Hartlib shared many of the concerns that specialists in religious history have characterised as archetypically puritan. On 1 April 1653, for instance, Austen wrote to Hartlib detailing his concerns about a practice common amongst the people of Oxford. In a few weeks it would be May Day, when the townsfolk would indulge in the ‘sinfull superstitious Custome’ of ‘Making Garlands, of flouers, & puting them vpon two of the company who are carried vpon the shoulders of the rest, vp & downe the streets’. Austen was fervent in condemning this behaviour: ‘Many vaine, & sinfull things are then practised among them to the Dishonour of god’.Footnote83 His complaints were typical of the godly, who had long laboured to suppress the maypole and associated practices in the name of moral reformation.Footnote84 But it is telling that, in an Oxford already under puritan rule, he would turn to his Prussian friend for help against this menace, appealing to Hartlib to petition parliament for another law to suppress the practice. We have no indication of Hartlib’s response to this request, but Austen’s interruption of their usual horticultural discussions implies that he shared many of Austen’s religious and political concerns. A resident of London since 1631, Hartlib had long associated himself with eminent puritan figures, including Thomas Goodwin, the Independent divine with whom he corresponded from the 1630s, and other members of the Westminster Assembly.Footnote85 And when the irenic Sir Cheney Culpeper found that John Dury, the tireless advocate of Protestant pacification, was not originally invited to serve as one of the Assembly’s divines, it was to Hartlib that he turned, requesting that the intelligencer might have Dury nominated for the role.Footnote86

But while such connections seem to demonstrate Hartlib’s puritan credentials, his close association with Dury, a man whose ecumenism led to his forging alliances across otherwise acrimonious confessional divisions, suggests otherwise. Though he adopted the side of parliament in the Civil Wars, and cooperated happily with the Cromwellian authorities thereafter, Hartlib had none of the concern for precise confessional distinctives that characterised the leading puritan and Reformed divines of the era, and he was willing to cross sizeable political divides in his efforts towards collective ‘improvement’. For the most part, the circle that coalesced around him reflected this ecumenical outlook, influenced less by the polemical divinity of Thomas Goodwin and more by the pansophist ideals of Jan Amos Comenius. Dury was on good terms with puritan and Laudian divines;Footnote87 Robert Boyle read and apparently approved of aspects of Socinian writings (though he was later a loyal son of the established church); and Benjamin Worsley seems to have had fairly pronounced Socinian sensibilities, if the contents of his library are anything to go by.Footnote88 In his efforts to help Austen, Hartlib had no qualms in simultaneously praising the regicide Colonel John Barkstead for his role in providing the manuscript later published as A Designe for plentie (1652), alongside commending to Austen the Earl of Southampton, a powerful Royalist noble, who nonetheless shared their passion for fruit trees.Footnote89

The ecumenical, utopian, and politically ambiguous stance espoused by Hartlib and Dury may have overlapped with aspects of mainstream puritanism, particularly in the stridency of its millenarianism.Footnote90 But much of it fails to align with a working definition of ‘puritanism’ in this period. Quite what that definition may be has been the subject of much historiographical debate, and space does not permit an adequate representation of the voluminous literature.Footnote91 For our purposes, it is sufficient to regard English puritanism as one wing of the wider movement that historians of theology, notably Richard Muller, have called ‘Reformed Orthodoxy’ – that is to say, it was, broadly speaking, Calvinistic in doctrine.Footnote92 Some aspects of puritanism were unique to the English situation, especially in its reaction to the continuing episcopal (to its detractors, quasi-papist) character of the Church. But many of its sociocultural features were a natural corollary of the doctrinal tenets of Calvinism, shared by other movements within the early-modern Reformed tradition. Reformed soteriology, which was robustly predestinarian, emphasised the discernment of the individual’s status as one of God’s ‘elect’, for whom Christ died, and an emphasis on personal holiness, together with a distinction between ‘the godly’ and ‘the world’, flowed from this. This high-stakes process of spiritual discernment was an obsessive feature of the religious lives of the godly in England in particular, and a whole industry of works describing signs of true spiritual regeneration rolled off English presses, part of what Philip Benedict has called ‘the experimental predestinarian tradition’.Footnote93 Related to this were certain practices of piety, personal and communal, many of them unique to English Calvinists: strict sabbath observance, sermon-gadding, and the reading of ‘godly’ devotional works, along with household worship and regular fasting.Footnote94

Many of the puritan divines with whom Hartlib dealt correspond to this definition of the movement. John Owen, for instance, was a lifelong exponent and staunch defender of Reformed soteriology, from his anti-Arminian A Display of Arminianisme (1642), his first published work, through to his The Doctrine of Justification by Faith through the Imputation of the Righteousness of Christ (1677). Fearing for his status as a Christian, Owen had experienced long years of spiritual depression in his youth, before an afternoon of sermon-gadding led to his finally finding assurance of salvation.Footnote95 Owen’s emphasis on holiness came out in Of The Mortification of Sinne in Believers (1656) and Of Temptation, The nature and Power of it (1658), while he advocated strict sabbath observance in Exercitations Concerning the Name, Original, Nature, Use and Continuance of a Day of Sacred Rest (1671).

Compared to Owen, Hartlib, a man of more ecumenical persuasion, appears less obviously ‘puritan’. That of course limits the explanatory power he provides for exploring the connections between English puritanism and early science. But Ralph Austen very much was a puritan, in the same vein as the likes of Owen or Thomas Goodwin, both of whom he knew. This has been understated in the literature on Austen, which digs no deeper than associating him with Hartlib and his pansophist religious concerns. But Austen’s works reveal him to have been something of a lay Reformed theologian. In part this underemphasis has resulted from T.F. Henderson’s mistaken claim in the Dictionary of National Biography that the Reformed and anti-Quaker The Strong Man Armed not Cast Out (1676) was not by the Oxford cider man, despite its author being named as one ‘Ra. Austen’.Footnote96 This seems to have been taken for granted in subsequent historiography, which has ignored this text. In fact, Henderson’s claim that the work ‘contains no reference to gardening’ is false. Austen defends the doctrine that Christ indwells only the elect – an attack on the Quaker doctrine of the ‘light within’ – on the basis of a ‘Similitude between Natural and Mystical Fruit-trees’, something that will sound familiar to readers of his Spiritual use of an Orchard (1653).Footnote97 This work, animadverting on a Quaker text, The Strong Man Armed Cast Out (1674), was responded to by the author of that work, one James Jackson, who made direct reference to Austen’s occupation (as well as to Jesus’s parable of the tenants) in the title of his reply, The Malice of the Rebellious Husband-men against The True Heir (1676).

Despite the claim that Austen was ‘[John] Wilkins’s friend’,Footnote98 the social networks his correspondence with Hartlib bear witness to are markedly puritan in character (and indeed, Wilkins is barely mentioned). In December 1653, Austen suggested to Hartlib that he buy some of the common land in Shotover Forest, east of Oxford.Footnote99 It took him until August 1655 to give the scheme more impetus, by which time he had rounded up support amongst his friends in Oxford, many of whom, he suggested to Hartlib, could work as commissioners to decide the compensation for those who used the common land. ‘[T]hese honest Gentlemen my friends’, as Austen described them, included many influential Oxonian puritans: ‘Dr Iohn Owen: Vice-Chancellor of the Vniuersity of Oxon’; John Nixon, the puritan mayor of Oxford from 1636; Thankful Owen, president of John’s College; and Tobias Garbrand, principal of Gloucester Hall.Footnote100 Austen also listed Elisha Coles, the lay Independent divine who later authored the popular work A Practical Discourse of God’s Sovereignty (1673).Footnote101 As a London trader who settled in Oxford in 1650, Coles was in a similar boat to Austen.Footnote102 Both lacked a university education, but nonetheless produced works of popular divinity that proved successful. Austen spoke fondly of Coles, to whom he sometimes deputised his Registrar duties, referring to him as ‘My beloued brother’ in a letter to Hartlib in 1655.Footnote103

But if Coles was his closest friend, his foremost spiritual counsellor proved to be Henry Langley, the Independent divine intruded as master of Pembroke College in August 1647. In his expanded second edition of The Spiritual Use of an Orchard, published as a standalone volume in 1657, Austen lamented that many ministers shirked their pastoral duties, ‘think[ing] it sufficient to be diligent in their studies … but greatly neglecting this other duty, of enquiring, and looking into the particular state of soules’, something he himself had sadly experienced.Footnote104 But that was not true of Langley, whom he praised as a faithful minister of the gospel. Austen dedicated the first edition of his Spiritual Use of an Orchard (1653) to him, relating how Langley’s use of similitudes from nature, and especially fruit trees, had been an inspiration to him. But more than that, Langley had been the main instigator of Austen’s recovery from a period of severe spiritual depression. In his dedicatory preface, he explained that he presented the work to Langley ‘as a testimony of my thankfulnesse for all your labours in the Lord, and care for mee, from time to time, especially in my great Afflictions, which befell me about six years agoe in this place, when I was even stript naked both of inward, and outward comforts’.Footnote105 These ‘Afflictions’ he would go on to describe in moving terms in the work itself.Footnote106 More broadly, the experience seems to have given Austen clout amongst the godly in Oxford. Stephen Ford, the vicar of Chipping Norton and former chaplain of New College, vouched for Austen’s credentials by describing how ‘he hath beene exercised with many Temptations from his youth up; having passed through the spirit of bondage early in the morning, and by degrees came to close with Christ, and to attaine a comfortable assurance of his interest in him’.Footnote107 The vignette provided by Ford was confirmed in another preface to the same text, written by one ‘J.F.’, described as ‘A Minister of the Gospell’, who wrote approvingly Austen’s godly ‘conversation’.Footnote108

Despite Langley being the puritan divine apparently most amenable to Hartlib’s vision for reform,Footnote109 it was his connection to Owen that Austen was most proud of. He wrote excitedly to Hartlib in July 1653 of the ‘manifold encouragements’ about his Treatise, printing of which had finished in April of that year. Particularly encouraging were the commendations Austen received ‘from some spetiall hands’, principal among them ‘Mr Owen, Vice-Chancellor’, who ‘having beene pleased to take much paines in perusing of it (in order to lycence the Printing)’, had given him ‘great encouragements in it’.Footnote110 And, sure enough, Owen not only kept his copy of the work,Footnote111 but signed a testimonial vouching for Austen and his project, and even promised in February 1654 that he would commend the horticulturalist to the Lord Protector.Footnote112 In 1657 the expanded edition of The Spirituall use of an Orchard proudly advertised itself as bearing the imprimatur of ‘JOHAN: OWEN, Vice-Can: Oxon:’, taking advantage of the Independent divine’s growing status in a way that the first edition did not. Although Hartlib’s efforts amongst the Oxford puritans seem to have been focused upon Goodwin – understandable given their long correspondence – it is clear that Owen, possibly due to Austen’s influence, was sympathetic to Hartlib’s designs, meeting the Prussian personally in February 1654 and subscribing to one of Hartlib and Dury’s schemes of improvement in July of that year.Footnote113

How came Austen by such influential friends? As very much a part of the puritan party in Oxford, he doubtless engaged in religious activities, such as joining a gathered church, where he rubbed shoulders with such figures. More tangibly, though, Austen’s various roles in the Cromwellian regime at Oxford placed him at the centre of puritan circles. As the registrar of the parliamentary visitation, he had an inside view of the Cromwellian attempts to reform the university: indeed, almost the entire register of the visitation, detailing the visitors’ meetings and promulgations, alongside responses to their efforts, from 1647 until 1658, is in Austen’s hand. Given this, and the fact that the register was given to the Bodleian Library by the executors of Austen’s will, it seems likely that it was kept in his possession; the various different hands that feature in the register, alongside Austen’s, thus give us a good idea of the university figures with whom he interacted. In May 1648, the hands of both Francis Cheynell and John Wilkinson appeared, recording, respectively, the parliamentary orders for these two influential presbyterian divines to take up the headships of St John’s and Magdalen Colleges.Footnote114 The vituperative congregationalist Edward Bagshaw, meanwhile, contributed his retroactive response to the visitors’ 1648 test of loyalty in his own hand, explaining his allegiance to parliament’s rule.Footnote115 As well as putting Austen at the centre of the puritan reform party, his role as registrar made him synonymous with the visitation throughout the university. The visitors’ many pronouncements were made in his name, something that was duly noted in college records. At Lincoln an order to elect one John Taylor to a vacant fellowship, in June 1648, was subscribed by the singular name of ‘Ra: Austen’; so too, the election of the Hartlibian Robert Wood to the place left by the extruded William Owen.Footnote116 Payments made to the visitors were also made out in Austen’s name; in 1657, for instance, the bursars of Magdalen College made a payment of £4 to the horticulturalist.Footnote117

Austen combined his work for the visitors with a similar role at Christ Church, where he was employed as the Dean and Chapter’s registrar from July 1649 until May 1655.Footnote118 Although in June 1653 Austen complained to Hartlib that the College was behind on paying his salary,Footnote119 he continued to work there until 1660; by 1659, he appears in the College accounts as a verger (‘virgifer’), in charge of maintaining the chapel, for the undertaking of which he received 15s quarterly.Footnote120 Again, these roles put Austen at the heart of the puritan reformist party in the university. Christ Church, Oxford’s largest, wealthiest, and most prestigious college, was home to the most influential puritan divines: Edward Reynolds and, after him, Owen, as its Dean; the elder Henry Wilkinson, a canon and Regius Professor of Divinity; Peter French, the brother-in-law of Cromwell; and Henry Langley. Recording the events and decisions of meeting after meeting, Austen would have got to know the likes of Owen and Langley fairly well throughout his long tenure at the College.

Austen’s own beliefs and experiences were very much typical of the godly with whom he mixed. His aforementioned spiritual journey, from fear as to the certainty of his regenerate status to assurance of salvation, followed a pattern familiar to English Calvinists. In moving autobiographical excursions in The Spiritual use of an Orchard, Austen recounted the story of this decline and recovery, explaining how, locked in the midst of despair, it had seemed to him that ‘the Sun was clouded, and the spirit, and sap suspended,’ until

he lost not only the sence of the light of Gods countenance, towards him, & the sight of the graces of his spirit, but questioned all his former Evidences of his interest in Christ, and (especially at some times) even gave all for lost.Footnote121

It was only after a period of ‘Seaventeene, or Eighteene Months, or thereabouts’, that Austen experienced relief, writing of how ‘the sunne of righteousnesse beganne to arise with healing in his wings, and to cast some beames of light into his darke soule, which increased more & more unto the perfect day’.Footnote122 John Stachniewski has explored the prevalence of such cases of despair and melancholy, usually associated with predestinarian anxiety, amongst the godly.Footnote123 As we have seen, John Owen experienced something similar. It was perhaps an unsurprising by-product of a theological system that stressed a rigid doctrine of predestination, as even historical theologians sympathetic to Reformed thought have acknowledged.Footnote124

Animating this experience was a sense of the need for the individual to confirm their status as one of God’s elect, something that was a constant theme in Austen’s theological work. His spirituality was thus deeply inward-looking and meditative, with a particular focus upon the believer’s ‘communion’ with God, by which assurance of salvation might be bolstered. Already an established motif of puritan mysticism, ‘communion’ with God was usually expressed as a kind of experiential knowledge of God. Often, as Elizabeth Clarke has shown, it was articulated via allegorical readings of the Canticles, taken to represent the mystical marriage of Christ to the church, or to the soul of the believer.Footnote125 In 1638, for instance, Francis Rous wrote in The heavenly academie of how, married to Christ, Christian believers possess ‘blessings of the highest nature’: ‘remission of sins, peace with God, communion with God, conformitie to God, a spirituall sonship, an inhabitation of the Spirit, an earnest of an eternall inheritance’, and much else besides.Footnote126 The idea would be developed most fully, and famously, by Owen, first in lectures given in St Mary’s, Oxford, from 1651, and then in his popular Of Communion with God (1657), a work later criticised by William Sherlock as evidence of puritan ‘enthusiasm’.Footnote127 Austen’s first edition of The Spiritual Use did not treat the topic. But the second edition of 1657, which added a further eighty spiritual aphorisms to the original twenty, did, perhaps a result of his growing association with Owen. In the 26th ‘Observation’, the fact that the husbandman delights in his fruit trees (and vice versa) was taken to indicate that ‘There is a sweete fellowship, & communion between God, & his People, God delightes in them, and they delight in him.’ Just as in Rous’ work, Austen expressed this through the motif of marriage, rhapsodising the ‘reall, and substantiall pleasures’ available to the believer in Christ, which are nonetheless ‘but tasts, and beginnings of Eternall joyes and satisfactions’. Yet such ‘tasts’ are enough to transport the Christian beyond the visible world: ‘By close Communion with God,’ Austen wrote, ‘we live in another spheare, in another world, then the Common sort of Christians who improve [i.e. make use of] not Communion; it lifts Beleivers as it were in the third heaven, where are unspeakable pleasures, and contentments, and the soule saies, its good being here’.Footnote128

This spirituality was built upon doctrinal foundations that were stridently Calvinistic. Austen laid down the confessional gauntlet from the off, refusing to shy away from theological polemics: the first ‘Proposition’ of his Spiritual use of an Orchard was a stalwart defence of the doctrine of double predestination, the very issue that had provoked such heated debates in Oxford since the 1630s. Austen affirmed ‘That God from all eternity made choice of what Spirituall Plants he pleased, to plant in his Garden the Church, and refused others.’ This was something that ‘[God’s] word clearely manifests’,Footnote129 and appeared alongside many other central tenets of Reformed divinity in Austen’s work. He claimed that ‘Unregenerate persons (of themselves) cannot come to Christ, nor bring forth one good fruit’, criticising ‘the Error of those who hold free will’.Footnote130 But those who were recipients of God’s grace, Austen believed, could not lose their elect status. ‘[T]he sure, and safe condition of every beleever,’ he explained, was that ‘they shall never fall away’, since ‘Saving grace, or the Divine Nature in beleevers, abides in the soule for ever’.Footnote131 Austen also emphasised the believer’s union with Christ, and the identification of the pope as antichrist.Footnote132 All this was to echo central themes in Reformed Orthodox thought, especially since their codification and defence at the Synod of Dort in 1617.

Such doctrines were hardly uncontroversial, not least because of the growing influence of Arminian theology amongst parliamentarian supporters in the 1650s, spearheaded by the fiery Independent John Goodwin.Footnote133 It seems that Hartlib, less keen on doctrinal precision than on the peaceful cooperation of differing religious groups, was wary of Austen publishing such material. We might expect as much from less clearly ‘puritan’ characters. Anthony Wood, for instance, assumed that Austen’s foray into polemical divinity hampered the sale of his horticultural works.Footnote134 Boyle likewise discouraged any republication of the Spiritual Use when Austen approached him for support in republishing the Treatise in 1665, as he attested to Oldenburg.Footnote135 But Hartlib had also dissuaded Austen from publishing his spiritual aphorisms. Although Austen initially agreed as to the idea of ‘Printing only the Naturall part of the work first’,Footnote136 by the time it came to the printing process he had changed his mind, and he appended to the Treatise what he assured Hartlib was ‘only a tast’ of the theological material that he had produced.Footnote137 It seems likely that Hartlib, who wanted the project to be broad enough as to include the staunchly royalist Earl of Southampton, was wary of alienating potential supporters with divinity that was undoubtedly divisive.

Austen had no such qualms: his work made abundantly stark what he made of the political and religious upheavals of the day. Nowhere is that clearer than in his political theology, and the eschatological scheme wrapped up with it. As the events of the Civil Wars, regicide, and commonwealth developed, puritan preachers and laypeople alike turned to apocalyptic prophecies in scripture to explain the cataclysmic events unfolding around them. This was not a uniquely puritan phenomenon: throughout this period, eschatological fervour featured across the political and religious spectrum, as is evident in John Evelyn’s end time speculations, or John Worthington’s editing of Joseph Mede’s works.Footnote138 But Austen’s eschatology was most certainly puritan in origin. One influential voice in puritan apocalypticism was that of Owen, who developed a unique eschatological stance in the course of his parliamentary sermons of the late-1640s and early-1650s. In a sermon preached before the Rump on 19 April 1649, Owen advanced a novel interpretation of Hebrews 12:26 (‘Yet once more I shake not the earth only, but also heaven’), arguing that the ‘shaking’ of ‘heaven and earth’ should be understood as the providential refashioning of earthly kingdoms that would usher in the kingdom of Christ on earth. As Crawford Gribben has observed, this interpretation ran counter to the prevailing reading of the verse amongst English puritans, as shaped by Franciscus Junius’s notes in the Geneva Bible;Footnote139 it also differed from the interpretations of other radical Independents.Footnote140 Owen himself acknowledged this in the text of his published sermon. But the consent of ‘Junius, and after him, most of ours’ did not stop him from making the radical claim that ‘The Heavens of the Nations’ are ‘even their Politicall heights and glory, those Forms of Government which they have framed … with the grandeur and lustre of their Dominions’, while the ‘Nations Earth is the multitudes of their people, their strength and power, whereby their Heavens or politicall heights are supported.’Footnote141 For Owen, the political turmoil of the 1640s and 1650s was a sure sign that the eschaton was nigh.Footnote142

Austen’s own eschatological beliefs echo those of Owen, in language that is strikingly redolent of the Cromwellian Independent. Towards the end of his original Spiritual Use of an Orchard, Austen used pruning and digging as analogies for God’s providential governance of political affairs: just as the pruning of fruit trees leads to their eventual fruitfulness, so the commotions afflicting the church ‘will end in the settlement, peace, and glory of it.’ They were all a part of the ‘great work’ of God in the world, a work which he ‘is now about … even in our daies’. Crucially, Austen made this claim with reference to the same interpretation of Hebrews 12:26 as Owen, directly linking the ‘shaking’ spoken therein to political tumult: ‘When were the Heavens, and the Earth, and the Sea, so shaken as they have been of late yeares, who knowes not of the overturnings, and great alterations, that have been among us both in Church and State.’Footnote143

Austen seems to have taken Owen’s eschatology even further, his thought shaped by Fifth Monarchist literature. In the 1657 edition of The Spiritual Use, he implored his readers to observe ‘the visibile dispensations of providence’ so as to discern ‘what are the Designes of God in this our generation’, citing John Tillinghast’s Generation Work (1653), which encouraged much the same.Footnote144 Tillinghast had been influenced by Owen’s parliamentary sermons, though he took the historicist reading of apocalyptic texts further still, providing precise dates for the fall of the Roman Church (1656) and the onset of the millennium (1701).Footnote145 That he drew upon Tillinghast is indicative of the remarkable durability of Austen’s eschatological hope. By 1657, many puritan figures had stepped back from the eschatological optimism of 1649–50, partly in response to the threat posed by the Fifth Monarchists.Footnote146 But Austen had no such qualms in identifying himself with the group. And indeed, none of the eschatological sections of Austen’s 1653 Spiritual Use were altered upon its republication in 1657. Confident of ‘the certaine downefall of Antichrist’, Austen remained hopeful of a transformation in the church, and especially its ministry, in these last days of the world:

surely the time is at hand (and is not the day dawned already?) when the Gospell Ministry shall be purged, the drosse (carnall Ministers) shall be cast out, and the pure mettle preserved, according as was Prophesied, Mal. 3. 1,2,3.Footnote147

To this eschatology was wedded, somewhat unsurprisingly, a political radicalism. Describing the inevitable triumph of the Christian church, in 1653 Austen expressed his confidence that ‘such as oppose [Christ], and stand out in rebellion against him (though they be Kings and Monarch’s) … he will break such with a rod of Iron, & dash them in peeces like a Potters vessel, Psal:2.9.’Footnote148 Although this was an uncontroversial interpretation of the biblical text, it represented a very specific intervention in the fraught political climate of the 1650s, the memory of the regicide still fresh. There could be no doubting Austen’s politics.

III

Austen, then, was very much a coreligionist of the puritans seeking to turn Oxford to the Cromwellian cause in the 1650s. But to what extent did he influence them? It has often been assumed that divines like Owen and Langley expressed little interest in the concerns of the Hartlib circle. For the most part, Charles Webster’s narrative was built upon viewing the likes of Wilkins or Boyle as ‘puritans’, rather than a thorough analysis of the response of divines like Owen to Baconian ideals. Meanwhile, historians of theology, religion, and politics – who have looked at the Oxford puritans more thoroughly – have been explicit in distancing them from Hartlibian ideas. Blair Worden, in his work on Interregnum Oxford, has claimed that the reaction to Hartlib’s proposals for educational reform ‘was unwelcoming’ and that ‘his schemes for reform were ignored’ across the academic spectrum.Footnote149 Similarly, Richard Greaves has claimed that John Owen ‘displayed little interest in curricular reform, especially the new science’ – and indeed, there is no mention of Hartlib or Baconian ideas in any of the more specialised literature on the Reformed divine.Footnote150 To be fair to such scholarship, the evidence as to puritan responses to Hartlibian ideas is murky. If we take the case of Owen, the long-serving Vice-Chancellor, the sources indicate disparate conclusions. In July 1654 he delivered an oration at the university’s ‘Act’, or Comitia, a yearly celebration that included festivities and mock disputations, in which he certainly seemed to affirm his support for the new learning, noting with pleasure that the university was ‘making daily progress … in widening the boundaries of the sciences and in promoting literature side by side with piety and religion.’Footnote151 Three years later, again speaking at the Comitia, Owen lauded ‘the outstanding mathematicians’ of the university, who,

exceeding the common lot of learned men, have so clearly and eloquently put before the eyes of the learned new, marvellous, astonishing things, extracted from the very entrails of nature unknown to their predecessors, to be admired by their successors, not without glory and fame both to themselves and the University [.]Footnote152

Although Hartlib was less concerned with geometry than with more obviously practical disciplines, Owen’s reference to experimental method in natural philosophy was clearly Baconian in tone.

That Owen may have been sympathetic to the Baconian designs of the Hartlib circle is further suggested when we consider the evidence of his support for curricular reform. Having already been consulted on proposed revisions to the constitution of Trinity College, Dublin, during his sojourn in Ireland in 1649, in 1657 Owen was asked by Henry Cromwell, Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, to send a copy of Oxford’s statutes as a model for the foundation of a proposed second college for the University of Dublin. Owen’s response hardly voiced confidence in Oxford’s statutes, which had been framed under Archbishop Laud and famously mandated a rigid adherence to Aristotle’s corpus. ‘[O]ur statutes,’ he related, ‘as also those of the other university, beinge framed to the Spirit and road of studys in former days, will scarsly upon consideration, be found to be the best expediente for the promotion of the good ends of Godlinesse and solid literature which are in your ayme.’ He encouraged the Lord Lieutenant, instead, to seek out ‘men of Ability, wisdom, and piety’ who would be able to ‘compose a body of orders and statutes suited to the present light’.Footnote153

At first glance this might seem to be an uncomplicated echo of Hartlibian sentiments. In 1648, for instance, Thomas Gilson, an admirer of Hartlib who was a fellow of Merton College, wrote excitedly to the intelligencer of the opportunity ‘to Reforme statutes & constitutions’ at Oxford, thereby ‘planting ingenuity & advancinge Learninge’.Footnote154 But it is not clear what Owen meant by ‘the present light’, to which the Laudian statutes were not, in his estimation, suited. He had already used identical language in what was clearly a religious sense. His 1649 work Of toleration, appended to the printed edition of his regicide sermon, spoke of the spiritual knowledge granted to believers as ‘their present light and apprehension’.Footnote155 His arch-nemesis John Goodwin, meanwhile, used the phrase in a similar fashion, as referring to believers’ knowledge of God and how he ought to be worshipped, something he made clear in a work defending religious toleration.Footnote156

If that makes the case complicated, so too does a comment from Ralph Josselin, the lifelong diarist and minister of Earls Colne in Essex. Owen had ministered in neighbouring parishes to Josselin during the 1640s, first in Fordham, about five miles to the east of Earls Colne, from July 1643, and then in Coggeshall, a similar distance to the south, from August 1646.Footnote157 Josselin had been close to Owen during his tenure as an Essex pastor, and he duly kept his eye on Owen after the latter moved to Oxford in the 1650s.Footnote158 Word reached him of Owen’s controversial attempts to reform the University, which included reducing the number of oaths that university members had to swear, abolishing the Comitia, removing the Convocation voting rights of MAs, and reforming academic dress. On 8 July 1656, Josselin recorded how he

Heard how Dr owen endeavoured to lay down all the badges of schollers distinction in the universities: Hoods, caps, gowns, degrees, lay by all studdie of philosophy he is become a great scorne, the Lord keepe him from Temptacons …Footnote159

The Owen Josselin got wind of was not a learned Reformed divine who sought to encourage a Hartlibian approach to natural philosophy, but an anti-intellectual iconoclast.

But light is shed on this question by Austen’s work. The second edition of The Spiritual Use (1657) replicated the original twenty aphorisms of the first edition, with no changes in the body of the text. But Austen did make one addition to the marginalia. The sixteenth ‘observation in nature’ led to a discussion of the necessity of sending out ‘University men … into the service of the Church, and Commonwealth’,Footnote160 in which Austen added a word of advice absent from the original text. College heads, he wrote, ought to prepare newly-trained ministers ‘to preach Christ’,

by making Orders, and Rules in the severall societies for that end; and not to walke (in this great respect) by statutes made in darke, corrupt times; Is it likely such should be meete Rules for these Gospell times, these times of light, and Reformation?Footnote161

This comment almost certainly referred to the Laudian statutes, which in Austen’s estimation were hopelessly outdated. Of course, the context was a discussion of training for the ministry, and it is certain that he had in his sights the moral deficiency of the statutes, which to many Oxford puritans were insufficiently strict in mandating godly religious practices. But it is striking that Austen, who happily mixed puritan eschatology with Baconian utilitarianism, should take aim at the rigidly Aristotelian statutes, and in language so clearly reminiscent of Owen’s. Clearly, an emphasis on moral reformation could go hand-in-hand with a new approach to nature: and Owen, alongside Austen, had both in mind when criticising the Laudian statutes.

If Owen was speaking in Hartlibian terms of the deficiency of the statutes, this makes sense of Josselin’s comments about his approach to philosophy. To Josselin, educated at Cambridge in the 1630s, long before the mechanical philosophy began to have a foothold in the university, a Baconian emphasis on experiment and practical knowledge of nature would have seemed at odds with the emphases of traditional philosophy; indeed, it would have seemed positively unphilosophical. After all, the planting of fruit trees was (and still is) a rather different endeavour to Aristotelian metaphysics, and Hartlib’s schemes – focused on husbandry, silk-worms, bee hives, and enclosures – were thus often seen as anti-philosophical. Speaking at the funeral of John Langley, high master of St Paul’s, in 1657, Edward Reynolds criticised some Lutherans who, neglecting philosophy, ‘turned to Mechanick imployments’ and ‘Husbandry’.Footnote162 (This was an unfortunately ironic comment, given John Langley’s enthusiasm for Hartlib and Austen’s scheme for fruit tree planting.)Footnote163 To the likes of Josselin and Reynolds, Owen’s support of Hartlib’s schemes for improvement would have seemed to amount to the neglect of philosophy itself.

But this enthusiasm for Hartlib and his designs was not unique to (Henry) Langley and Owen among the Oxford puritans. As we have seen, Austen’s plans to buy Shotover forest were endorsed by the great and the good of the puritan party in town and university – among them John Owen, the mayor John Nixon, and the divines Thankful Owen and Tobias Garbrand.Footnote164 In the two Owens, Austen could count as his supporters two of the committee members of the second and third parliamentary visitations.Footnote165 As well as seeking support for his scheme to buy Shotover Forest, in February 1654 Austen rallied his influential Oxonian contacts to provide a testimonial to the value of his national fruit tree planting scheme. Among the signees was Peter French, the brother-in-law of Oliver Cromwell who was a canon at Christ Church. French had been reading Hartlib’s Legacie: or An Enlargement of the Discourse of Husbandry (first ed., 1651) – apparently with some enthusiasm, for he desired Austen to procure from Hartlib further instructions for cultivating clover grass.Footnote166

The likes of French, Owen, and Langley show that many Oxford puritans were amenable to Hartlib and Austen’s pleas for curricular reform and the advancement of learning. But it is not easy to gauge the impact that this receptiveness had. For one thing, the Cromwellian years were too short-lived, and the power-brokers of university life and politics soon found themselves proscribed from the intellectual mainstream. But even during their years in power, their primary aims belonged not to the world of fruit trees and silkworms but to defending the cause of the Reformed faith. Between the tasks of preaching, ministering in gathered congregations, leading colleges, and writing capacious theological treatises, little time could be set aside for the projects that the Hartlibians spent their days toying with. John Owen claimed (admittedly with a degree of self-aggrandizement) that his voluminous Doctrine of the Saints Perseverance (1654) was composed during ‘Journeyes, and such like avocations from [his] ordinary course of studies, and imployments, with some spare hours’.Footnote167 Henry Langley’s theological labours never even made it into print – unsurprising, perhaps, for someone who fulfilled the twin duties of a canonry at Christ Church and the presidency of Pembroke College with such aplomb. When Ralph Austen acted as a conduit between Hartlib and Goodwin, it was the latter’s busyness that prevented his engagement with the Prussian’s schemes. Twice in 1655 the horticulturalist called on Goodwin, only to find the great Independent to be away from town.Footnote168 When he finally did track him down, Austen was able to extract a promise of a reply to Hartlib, but preparations for the Act sermon soon got in the way.Footnote169

And yet, given this, the degree of engagement with Baconian ideas amongst these divines is remarkable. Owen, between all his duties, found time to read Austen’s Treatise of Fruit-Trees, and made sure to meet Hartlib during a visit to the capital. Langley arranged financial support for Hartlib; many of Oxford’s premier puritans encouraged Austen’s labours, as we have seen. We have to dig beneath the surface of the sources available to discern these things; and indeed, much of the literature on these figures has failed to observe their connection to the Hartlib circle.Footnote170 But the glimpse of puritan engagement with reformist ideas that we gain pays dividends. Puritans like Owen and Langley encouraged Hartlibian involvement in Oxford – and in doing so they left their mark on the history of natural philosophy in this period.

IV

At the Restoration, Austen followed many of his fellow puritans into nonconformity. But, dejected as he was in 1660, his religious radicalism only increased thereafter. Given his relationship to Owen and Langley, it seems likely that he was an Independent during the 1650s. But already in 1657 he had been arguing for the toleration of Baptists (who were Congregationalists in polity, but rejected the practice of paedobaptism) on the basis of the fact that ‘the difference [between the two positions] will prove (when throughly understood) but a circumstantiall difference’.Footnote171 And it seems possible that he himself became a Baptist in the final years of his life. His 1676 anti-Quaker work draws almost exclusively on Baptist writings – particularly Thomas Hicks’ Three Dialogues Between a Christian and a Quaker (1675) – rather than on the works of his puritan colleagues from the Cromwellian days.Footnote172 Even more strikingly, Austen himself appears to have flirted with Quakerism, the experience of which prompted his writing The Strong Man Armed Not Cast Out (1676). This text was written against an anti-Independent pamphlet titled The Strong Man Armed Cast Out (1674), by James Jackson, an ex-Independent turned convinced Quaker (clearly Austen’s horticultural talents were not matched by a gift for witty ripostes). Jackson responded to Austen’s invective with a short ad hominem pamphlet attack, titled The Malice of the Rebellious Husband-men Against the True Heir (1676). The acme of Jackson’s assault on Austen’s work came when he accused the Oxonian of hypocrisy: for Austen had – or so Jackson claimed – been a frequent attender of London Quaker meetings. ‘[T]hou went to most meetings of Friends in London’, he accused Austen, ‘and heard several Friends declare’. Indeed, he went on:

after thou hadst heard Alexander Parker [a prominent Public Friend], thou went to him, and discours’d with him, and came and told B. Clarke, Stationer in George Yard Lumbard-street, how sound thou found this Parker, and how well thou liked such and such, and could willingly joyn with them.Footnote173