ABSTRACT

Effectiveness is a term often used in intelligence studies. However, what effectiveness means in relation to intelligence remains elusive and intelligence effectiveness is studied from a wide variety of viewpoints. This paper aims to understand the concepts of effectiveness of intelligence and seeks to gain greater insight into what drives effectiveness. Reviewing 176 studies from 12 journals this paper identifies four paradigms of intelligence effectiveness – utility, intelligence failure, precision, and rigor- and describes distinct perspectives within each paradigm, the constructs used to determine effectiveness, and their antecedents. Analysis of the results shows that the paradigms of intelligence effectiveness are interrelated. In addition, paradigms and their constructs can be sequenced, revealing gaps in our knowledge, and providing an agenda for further research.

Introduction

Effectiveness is a term frequently used in intelligence studies. However, what effectiveness means in relation to intelligence remains elusive and intelligence effectiveness is studied from a wide variety of viewpoints. This is evident from the myriad of attempts to study effectiveness in intelligence. In general, effectiveness is defined as the extent to which desired aims of effects are realized and desired aims or effects are essential elements to determine effectiveness. Footnote1 However, in intelligence views on studies intelligence’s purpose, aims, or desired effects differ and are part of an ongoing academic debate.Footnote2

Differing views on the purpose, aims, or desired effects of intelligence and intelligence organizations have led to varying approaches to evaluating or measuring effectiveness in intelligence. In one such approach authors such as Eiran and Gill list detailed accounts of intelligence failures, providing a rich source for scholars studying factors leading to them.Footnote3 As a result, de Valk and Goldbach, argue that intelligence effectiveness is mainly determined by their ability to predict future events accurately in terms of success or failure.Footnote4 Others such as Lowenthal and Marks and Marchio agree that the accuracy of predictions determines the effectiveness of intelligence but disagree with the binary nature of failure versus success.Footnote5 Taking in a different approach Whitesmith claims that effectiveness of intelligence is determined by its objectivity and the rigor of the process.Footnote6 From another point of view Cayford and Pieters, and Marrin consider the support to customer decision-making as the fundamental goal of intelligence organizations and approach effectiveness from this viewpoint.Footnote7 However, approaches to intelligence effectiveness appear to be divergent and to some degree incompatible. In addition, these different approaches have yet to be contrasted.

Many of these endeavors to determine effectiveness of intelligence are often the result of government inquiries on past intelligence ineptitudes. These inquiries have led to a call for increased accountability and more thorough democratic governing mechanisms of intelligence organizations. Clearly, assessing effectiveness of intelligence is relevant. In addition, determining what intelligence effectiveness means enables intelligence organizations to evaluate their processes and products, it bolsters management, facilitates learning and creates transparency and accountability.Footnote8 Caceres-Rodrigues and Landon-Murray argue that this makes intelligence effectiveness a key issue for intelligence scholars.Footnote9 Moreover, they call for systematic reviews of these key issues in intelligence studies to explore the state of knowledge, to identify questions unanswered, and provide direction for future research.Footnote10 This demand to examine intelligence effectiveness more systematically is echoed by Mandel and Tetlock and Wheaton.Footnote11 As a systematic review of intelligence effectiveness is absent from the literature, this study conducts a systematic review of intelligence effectiveness with the aim to understand the concepts of effectiveness in intelligence. In addition, it aims to gain greater insight into what drives intelligence effectiveness. To achieve this, this paper sets out to answer two questions: what constitutes effectiveness of intelligence and how is intelligence effectiveness operationalized in intelligence studies literature?

The following section elaborates on the methodology used. Then, the results section provides an overview of approaches to effectiveness in intelligence. Furthermore, the approaches are contrasted against each other to explore more in-depth how effectiveness of intelligence can be defined. The discussion section will analyze the findings and present a research agenda to study intelligence effectiveness.

Data collection and analysis

A systematic literature review is a methodical and comprehensive analysis of existing research on a specific topic.Footnote12 This systematic review is based on contributions to journals that discuss effectiveness of intelligence and sets out to explore concepts of intelligence effectiveness in intelligence studies.

Data selection

Systematic reviews start with the selection of relevant studies by conducting a search of bibliographic databases with search strings that include predefined keywords and search terms. An initial attempt to select relevant articles by conducting a database search in this way was unsuccessful because it returned a vast amount non-relevant hits form a wide variety of fields unrelated to topic at hand. Especially problematic is that fact that the term ‘intelligence’ is an academic homonym. As a search term in database searches any combination yields a wealth of hits from artificial and emotional intelligence and their relation to effectiveness on myriad of topics from medicine and psychology to organizational effectiveness. Another prevalent return from these kind of database searches is human intelligence, which did not refer to human intelligence as it is understood to be in intelligence studies. Attempts to refine the search by further specification and excluding unwanted terms resulted in a reduction of hits, but it also led to doubts concerning the reliability and comprehensiveness of the returns from the database search. Therefore, the author opted for a different approach by manually selecting relevant articles from a predefined set of journals. The approach is not unwarranted as both HorlingsFootnote13 and RietjensFootnote14 have conducted reviews in intelligence studies based on articles selection from a predefined set of journals. This means that this study deviates from established methodological practices concerning data selection for systematic reviews. This limitation is acknowledged as the methodological approach is driven partly by pragmatism and likely excludes a part of the body of knowledge. However, the method used is intended to trade completeness for reliability and replicability. Other researchers could use a similar method to attempt to replicate the results from journals this study unwillingly omitted.

To aid a methodical and comprehensive analysis, journal selection aimed to provide a broad overview of work on effectiveness in field of intelligence studies. Journal selection was conducted in four steps. First established academic journals as listed by Coulthard and Marrin,Footnote15 were compared to those used by HorlingsFootnote16 and Rietjens.Footnote17 This yielded 9 journals used in at least two of the studies. Next the list was refined to exclude those journals that could not be accessed at that time, excluding only the Journal of Intelligence and Analysis. Third step added journals used by Horlings or Rietjens that may provide insights into intelligence effectiveness from the perspective of a differing field of study. This led to the inclusion of Defense & Security Analysis and Public Policy and Administration. This list of 10 journals was then complemented with two journals that were expected to contain views or debates on intelligence effectiveness that were not prevalent in flagship intelligence studies journals. Defense and Peace Economics was added because the journal has contributed to debates on effectiveness of defense policy. The Journal of Strategic Studies was added based on the journals advertised aim and scope. It was expected to include contributions to the debate on purpose, aims, and desired effects of intelligence in relation to warfare, defense policy and strategy. This process yielded the following selection of journals:

Intelligence and National Security (INS)

International Journal of Intelligence and CounterIntelligence (IJIC)

Journal of Intelligence History (JIH)

The International Journal of Intelligence, Security, and Public Affairs (IJISP)

The Journal of Intelligence, Conflict, and Warfare (JICW)

Journal of Policing, Intelligence and Counter Terrorism (JPICT)

Studies in Intelligence (SII)

American Intelligence Journal (AIJ)

Public Policy and Administration (PPA)

Defense & Security Analysis (DSA)

Defence and Peace Economics (DPE)

Journal of Strategic Studies (JSS)

Next, only studies published from 2012 to 2022 were included to ensure that studies reflected the most recent ideas on intelligence effectiveness. This resulted in 5214 possible contributions from which to identify relevant studies. To identify studies from this set, studies were selected when they addressed the issue of effectiveness of intelligenceFootnote18 in the title or abstract. When doubt arose, the conclusion was screened to determine whether the study addressed the issue of effectiveness.

The verification process identified 240 articles. Further screening excluded five records because they were either correspondence, commentaries, or book reviews, leaving 235 research articles after the screening. Determining eligibility was the last step in selecting studies for this review. Studies were eligible for inclusion when they met two criteria. First, the article described a concept of effectiveness of intelligence. Second, the paper operationalized this concept of effectiveness of intelligence into a construct of intelligence effectiveness. This resulted in 176 studies eligible for inclusion in this review. Although 59 other studies had passed the necessary conditions for selection and screening, they were excluded because they failed to describe a concept of effectiveness of intelligence or failed to operationalize a concept of effectiveness.

Data analysis

First, the meta-data of the studies was coded to include authorship characteristics – name, number of authors, educational and professional background, and nationality. The educational background was extracted from notes on the contributor included in the paper, from the author’s ORCID ID, or by searching for the author’s CV. This process also yielded data for the author’s professional background and nationality. Next – if applicable – the intelligence organization studied, and the study’s timeframe were coded. The intelligence organization’s name, type, country of origin and service branch were determined. In addition, the methodological characteristics of the study were determined – e.g., empirical or conceptual, the data collection method used, and qualitative or quantitative data analysis. Lastly, when appropriate the sample size and population was included.

Then, the author coded the content of the studies by identifying the concept of intelligence effectiveness used. Coding for the concept of effectiveness was conducted using an iterative process. First, the description of effectiveness mentioned in the study was included, which was then categorized into an approach to effectiveness of intelligence. This step revealed several distinct perspectives on intelligence effectiveness. In the second step the codification of effectiveness concepts and their corresponding perspectives were reviewed to identify commonalities between them. The third step identified the constructs to measure effectiveness for each article. This more in-depth examination of the measurement of intelligence effectiveness made it possible to reexamine the initial categorization of the second step. When appropriate the identification of constructs lead to recategorization of a study. Then, factors influencing effectiveness constructs were identified. When these were found in the study they were coded as antecedents. The iterative coding process described above then yielded paradigms of effectiveness, their distinct perspectives, the constructs used to determine effectiveness within each perspective, and factors influencing the constructs of effectiveness, i.e., antecedents.

Since manual coding processes are prone to subjectivity, the author sought to enhance reliability by actively seeking feedback through discussions with colleagues during the conduct of this research. Moreover, these discussions were fueled further by the iterative nature of coding process employed. This resulted in constant review of the coding and categorization. In addition, the author engaged in discussions with partitioners and fellow intelligence scholars after presenting this work at the International Association for Intelligence Education (IAFIE) conference and the Netherlands Intelligence Studies Association conference in 2023. The iterative nature of coding process, the resulting discussions during the research, and the engagements at the conferences aided in defining codes and categories more clearly and helped to set better boundaries for codes and categories. To ensure consistent application of coding practices during the conduct of the research, coding at the start and end were compared once all the articles were coded and categorized.

Meta data analysis

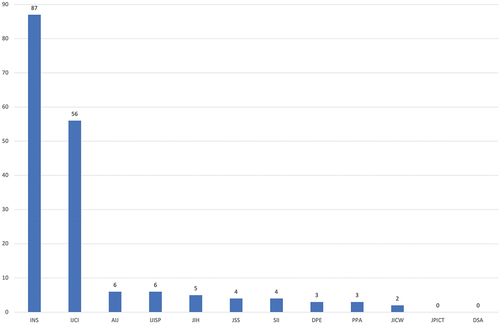

shows the distribution of studies that address effectiveness of intelligence across the selected journals from 2012 to 2022. As the figure shows, studies published in Intelligence and National Security and the International Journal of Intelligence and CounterIntelligence make up the bulk of the contribution to this subject. Surprisingly, Journal of Policing, Intelligence and Counter Terrorism and Defense & Security Analysis have yielded no eligible results. The remaining journals have published considerably less on the subject.

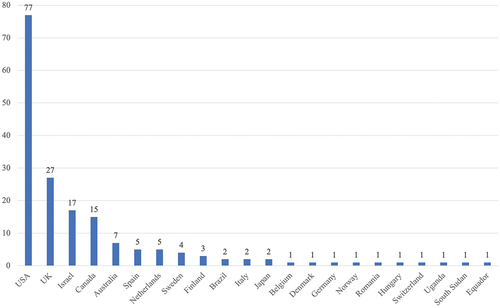

Of the studies in this review, 127 have a single author, while 49 have multiple authors. shows the number of first authors per country who published studies that address effectiveness in the selected journals and timeframe. Although the set of studies has authors from 21 countries, most of the studies are written by authors from the United States and US-allied countries. Van Puyvelde and CurtisFootnote19 attributed the abundance of English-speaking authors to the fact that authors make most contributions from the USA, UK, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand, which comprises 126 (71 per cent) of contributions to this review. And this bias towards English-speaking nations becomes more apparent when looking through the lens of US alliances. 137 (77 per cent) contributions can be attributed to authors from a NATO member country, and only 13 studies have authors originating from countries that cannot directly be considered US allies.Footnote20 No authors from large NATO member countries such as France and Turkey have contributed to these journals, and countries such as Germany and Italy are limited with one and two contributions, respectively. Limited contributions by authors from large NATO member countries may give further credit to Van Puyvelde and Curtis’s argument that language barriers may be the cause of limited non-US views in intelligence studies.Footnote21

Gender diversity in authorship is limited because the overwhelming number of authors is male (89 per cent) compared to fewer women (11 per cent) contributing to this topic. Female co-authorship shows a slightly different pattern because a higher percentage of co-authors are female (27 per cent) than the rate of female first authors. The distribution between male and female first authorship approximates what Van Puyvelde and Curtis found but differs from the findings of Rietjens, Horlings, and Tuinier, indicating that the inclusion of female authors may vary across intelligence studies subfields.Footnote22 More diversity is found in authors’ professional, educational, and organizational backgrounds. Analysis of professional backgrounds reveals that academics publishing on intelligence effectiveness come from 26 scientific disciplines. Most have a background in political science, followed by history, intelligence studies, international relations, psychology, and philosophy. Professionals come from 22 scientific disciplines, and their educational background differs from the academics only in the distribution across scientific disciplines.

Results

Four paradigms of intelligence effectiveness emerge from the articles in this review. First, utility, which is the most used concept of intelligence effectiveness in intelligence studies, makes up almost half of the papers in this review. Effectiveness from the utility perspective is defined as the degree to which intelligence organizations contribute to a desired security goal.Footnote23 Second, is the effectiveness paradigm of intelligence failure. Intelligence failure refers to surprise on the part of the customer caused by either the intelligence organization’s inability to draw appropriate, correct, or sound conclusions, or by the customer’s failure take mitigating actions.Footnote24 In this paradigm, intelligence and the intelligence organization is either right or wrong. This binary approach disregards uncertainty that may be inherent to intelligence. The third paradigm is precision, in which proponents argue that effectiveness of intelligence is determined by the extent to which analytical products make accurate or inaccurate assessments.Footnote25 This paradigm recognizes an inherent uncertainty in predicting future events and that this uncertainty is communicated through confidence levels and probability qualifiers to customers. Precision is not about right versus wrong but attempts to determine how often uncertainty was judged correctly. The last paradigm is rigor. Scholars of this paradigm claim that intelligence’s effectiveness is about the process’s rigor.Footnote26 They focus on improving analytic processes and encourage using Structured Analytical Techniques to reduce biases and mental pitfalls to enhance the accuracy of products.Footnote27 In the next sections, an analysis is made of how these paradigms operationalize effectiveness by identifying competing perspectives, their constructs, and their antecedents of each paradigm. The distribution of articles across paradigms is shown in .

Table 1. Number of articles per paradigm.

Utility

Two perspectives on the utility of intelligence can be identified. First, the utility of intelligence organizations lies in their ability to support decisionmakers in attaining an aspired security goal. The second perspective of utility is the intelligence organizations’ contribution to societal security goals, which studies governance mechanisms of intelligence organizations. These perspectives differ in the level of analysis. The decisionmaker-support approach studies effectiveness at a product and intra-organizational level, whereas the governance approaches effectiveness studies effectiveness at an inter-organizational and institutional level. depicts the perspectives according to the utility paradigm, their corresponding constructs, and antecedents.

From the perspective of decision-making support, intelligence organizations are effective when they inform decisionmakers about their environment and enable them to make decisions that yield the most beneficial contribution to the decisionmaker’s goals. Salmi specifies what a beneficial contribution means by defining that intelligence should ’ … contribute to better decisions and judgments [of] decisionmakers … ’.Footnote28 Three constructs can be identified that define the degree of decision-making support. First, judgements are hypothesized to improve when intelligence outputs are actionable,Footnote29 meaning outcomes should contribute to the decisionmaker’s goals. The construct of actionability is operationalized as the number of resulting interventionsFootnote30 or by the number of fulfilled intelligence requirements,Footnote31 which are found to be positively related to information accuracy, recentness, and reliability.Footnote32 However, modern information environments contain larger volumes of information and information overload may negate the effects of information accuracy.Footnote33 As a consequence, high information volumes need to be managed by developing and utilizing processing capabilities within current intelligence processes.Footnote34

The second construct of decision-making support is sensemaking or knowledge production. Omand specifies how analysts are to fulfil intelligence requirements, adding that the ‘basic purpose of intelligence itself is that it helps to improve the quality of decision-making’.Footnote35 This is achieved through knowledge production and sensemaking of complexities.Footnote36 Sensemaking is operationalized by determining the volume and quality of knowledge production through intelligence collection. One example of empirical work on this construct is Turcotte’s study which describes how intelligence gathered from German prisoners of war accumulated a large amount of knowledge, aiding the Allied war effort.Footnote37 Another example is Hamm’s examination of British efforts to gain insight into the Ottoman Empire.Footnote38 He concludes that eventually, the knowledge gained benefitted British efforts to manage the effects of the Ottoman collapse. In turn, knowledge production is influenced by the questions asked and answered and the collection methods employed. Unfortunately, neither intelligence requirement development nor requirement fulfilment has been studied concerning sensemaking.

The third construct of decision-making support is uncertainty reduction. The theoretical rationalization is that sensemaking reduces uncertainty for decisionmakers and enables them to optimize decision-making.Footnote39 This rationalization is supported by Izquierdo Triana et al., who find that determining financial risks through intelligence contributed positively to decision making and financial performance of 61 Spanish companies.Footnote40 However, Ben Gad et al. argue that uncertainty can only be reduced to a certain extent ‘in a world of unreliable probabilistic information’.Footnote41 Acuff and Nowlin operationalize uncertainty by determining the number of alternative viewpoints. In essence, they argue that uncertainty needs to be accurately determined and that utility of intelligence lies partly in its accuracy in determining uncertainty. However, they find those missing in their evaluation of competing assessments in National Intelligence Estimates of two cases, the decision to deploy US troops to South Vietnam between 1962 and 1967 and the effects of Mikhail Gorbachev’s reform.Footnote42 Empirical work identifies two variables influencing uncertainty reduction. First, the employment of self-learning strategies on the part of the decisionmakers is positively associated with uncertainty reduction, indicating that intelligence consumers play a pivotal role in reducing uncertainty.Footnote43 Second, because uncertainty is partially determined by the degree of uncertainty in the intelligence gathering and assessment process, it is argued to be positively related to information accuracy, recentness, and reliability, variables which can be viewed as the operationalization of information quality.Footnote44

An alternative perspective on the utility of intelligence is that of governance. This perspective asserts that budget allocations are paramount to assessing effectiveness from a governance perspective. Effectiveness is operationalized by assessing either the degree to which mechanisms of checks and balances ensure accountability for fiscal spending on intelligence, or by assessing whether these mechanisms prevent the production of intelligence irrelevant to the political agenda and prevent waste of public resources. Steinhart and Avramov outline that the mechanisms of checks and balances should be capable of yielding two primary results. First, they must ensure accountability by delivering intelligence products that are reliable, objective, and fiscally responsible.Footnote45 Empirical work on accountability is limited to descriptions of governing mechanisms in intelligence organizations. In a comparative study of intelligence organization accountability mechanisms in New Zealand, Australia, and Canada, Brunatti found that governance structures are closely aligned to how countries define their national interests. Canada’s definition of its interests was value-based, which means that it defined its security in terms of values, norms, and laws. In contrast New Zealand’s and Australia’s definition was material-based, thus more focused on physical and economic security.Footnote46 As a result, New Zealand and Australia have greater legal maneuverability in security matters than Canada. Yauri-Miranda assesses intelligence agencies’ authority by analyzing accountability mechanisms in Spain and Brazil and identifies four principles governing accountability: representation, regulation, justice, and trust.Footnote47 In a study comparing governance structures in six South American countries, Cepik argues that regulation and justice are correlated.Footnote48 He finds legislation and external controls to be weak in regulating intelligence-gathering or repressive operations and weak in countering political misuse. However, democratic governance structures don’t necessarily lead to more accountable intelligence organizations compared to dictatorships due to the strain governing mechanisms put on intelligence budgets,Footnote49 due to increasing monitoring and negotiating costs.Footnote50 Although the studies above define effectiveness of intelligence organizations as the degree of accountability, none make these constructs measurable.

Second, Steinhart and Avramov contend that mechanisms of checks and balances must maintain alignment with the political elite’s agenda, as intelligence that lacks relevance to their priorities is a waste of taxpayers’ resources and offers no value to the democratically elected government.Footnote51 Gilad et al. suggest that significance to the political agenda may be operationalized by examining how intelligence contributes to optimizing military budget allocation.Footnote52 In their theoretical optimization model of military expenditure as part of overall government budget allocations, they bridge the gap between the ability to support decision-making and the governance view of utility, arguing that the ‘military capability of a country is a function of its expenditure on weapon systems [and] intelligence’.Footnote53 In addition, here is a case to be made to reverse the direction of causality by proposing that the degree of relevance determines budget allocation. Unfortunately, work in this perspective is conceptual and remains untested in studies of this review.

Intelligence failure

The paradigm of intelligence failure revolves around two perspectives: first, the failure to accurately predict a future threat and second, the failure to act on intelligence. The perspective of failure to predict asserts that intelligence aims to avoid failure, inferring that the effectiveness of intelligence organizations is mainly determined by their ability to predict future events accurately. Vrist Rønn defines intelligence failure as the intelligence organization’s ‘…inability to reach relevant conclusions, such as the inability to predict a terrorist attack or other unwanted/criminal actions. They also refer to any wrongful and defective conclusions’.Footnote54 From the perspective of failure to act, Ikani et al. argue that the absence of intelligence surprise is a performance indicator for foreign policy, implying that effectiveness of intelligence can only be assessed indirectly through the effectiveness of its customers.Footnote55 shows the perspective, constructs, and antecedents of the intelligence failure paradigm.

The first perspective is failure to predict, and the construct used is the accurate prediction of a future event. The ability to give accurate predictions is hypothesized to be positively associated with the quality of analytic tradecraft and subsequently rigor.Footnote56 Case studies by Arcos and Palacios, Mettler and Wirtz indicate some validity to this claim.Footnote57 Stivi-Kerbis argues that the volume and quality of information used determines the quality of the analysis.Footnote58 However, information volume may also have a direct relation to failure. Karam finds evidence that the number of different sources used is negatively associated with failure in his case study of US failure to predict the Iraqi revolution of 1958.Footnote59 The effects of information quality on failure to predict remain unclear. Little work is done to measure quality of information in relation to this perspective.

In contrast, research often examines quality determinants without determining the quality level. Determinants of information quality are the depth of penetration into a target source,Footnote60 the degree of intelligence collaborationFootnote61 and the strength and presence of preconceived attitudes in analyst.Footnote62 Wilson et al. have also shown that these preconceived attitudes were present in the early stages of the COVID-19 crisis,Footnote63 and Connelly et al., Lillbacka and Wilkinson have led them to be one of the causes in their respective cases of military intelligence failures.Footnote64 Once these preconceived attitudes are present, limited receptivity to new informationFootnote65 or even unwillingness to absorb new informationFootnote66 may increase the rigidity of conceptions,Footnote67 leading to analytical self-censorship in some instances.Footnote68 Factors constraining analytical quality leading to intelligence failure are analytical pathologies in this paradigm.

Besides these analytical pathologies there are also organizational pathologies affecting accuracy of prediction in the paradigm of intelligence failure. Barnea and Meshulach refer to this as organizational cognitive failure and define it as the organizations mistaken threat assessment.Footnote69 Organizational cognitive failures are found to be caused by organizational issues such as culture, lack of leadership, unclear processes, lack of coordination and limited intra-organizational information sharing.Footnote70 In addition, organizational learning can serve as a constraint on intelligence failures,Footnote71 as demonstrated by Libel in his examination of the self-driven adaptation initiatives within Israel’s foreign intelligence agency.Footnote72

Organizational factors have also been found to affect the failure to act, the second perspective of intelligence failure. The construct in this perspective is the decisionmaker’s receptivity. Gentry argues that fear of client dissatisfaction, personal bureaucratic greed, and fear of intra-organizational consequences limit decisionmaker’s receptivity.Footnote73 In addition, Borer et al. identify sources of managerial and customer censorship that dissuade action after intelligence reports imminent threats and found that some issues within the ‘intelligence-policy nexus’ cannot be influenced by intelligence organizations.Footnote74 In a more optimistic attempt to identify organizational factors that limit action, Ikani et al. argue that limited attention and prioritization may lead to a failure to act.Footnote75 Limited attention and prioritization at the individual level may also influence decisionmaker receptivity, with low or absent receptivity leading to a failure to act. Connelly et al. found that US decisionmakers may have had limited attention for the Shas downfall in Iran because they were engaged in high-level negotiations leading up to the Camp David Accords and consequently failed to act decisivelyFootnote76 Similarly, Dahl has found that US military’s attention to warning signs leading up to the Japanese attack on Midway was given more attention, than warnings prior to the Pearl Harbor attack which were not prioritized at the time.Footnote77

Decisionmaker receptivity is only partly influenced by due attention and prioritization but also by client attitudes, i.e., acceptance of the threat analysis and the decisionmaker’s open mindedness to discordant claims.Footnote78 Gradon and Moy found that politization of intelligence restrains decisionmaker receptivity in their case study of intelligence failure during the COVID-19 pandemic,Footnote79 as has Ryan in her examination of the US’s successful denuclearization of Iraq in the 1990s.Footnote80 In addition, product quality regarding timeliness and convincingness affects decisionmaker receptivity.Footnote81 But there appears to be some kind of sweet spot regarding timing.Footnote82 Too early and one risks crying wolf; too late and one forfeits the opportunity to act decisively. Moreover, convincingness apparently compounds the effect of timeliness. Ostergard studied timeliness in relation to Ebola outbreak warnings and found warnings almost immediately led to action.Footnote83 Decisionmakers were convinced of the severity of the situation and acted, whereas in the case of COVID-19 decision makers were unconvinced of the severity in the early stages of the outbreak and were more hesitant to act.Footnote84 Similarly, Connelly et al. found reluctance to act on the part of the US State Department when early signs appeared that the Shah of Iran was facing a revolution.Footnote85 The studies above show that timeliness and convincingness increase decisionmaker receptivity, but timeliness alone does not lead to action unless the information provided convinces the decisionmaker.

Precision

The precision paradigm differs distinctly from the intelligence failure paradigm which views prediction accuracy which views accuracy solely as the binary state of right or wrong prediction. Chang argues that the effectiveness of intelligence can be determined by evaluating when, why, and how often intelligence makes accurate or inaccurate predictions.Footnote86 But accuracy is not merely about Marchio’s so-called ‘batting averages’ of analysts and intelligence organizations.Footnote87 It is also about communicating probabilities to intelligence customers and how the ambiguity surrounding the communication of probability qualifiers limits their utility to intelligence customer.Footnote88 Consequently, this review identifies two perspectives on the precision of intelligence: prediction accuracy and communicating uncertainty. An overview of the perspectives, constructs, and antecedents of the precision paradigm is given in .

First, precision revolves around how often assessments are correct and how accurate intelligence is. In contrast to the intelligence failure which only looks at instances where intelligence incorrectly assessed future events, i.e., it led to surprise, this approach recognizes that intelligence is inherently uncertain. These uncertainties are generally communicated explicitly to intelligence customers. However, from time-to-time events will play out differently from prior assessments. Chang, Friedman and Zeckhauser, Hetherington, Lowenthal and Marks, and Speigel propose to determine the accuracy of intelligence and to identify factors that affect accuracy in intelligence.Footnote89 Friedman and Zeckhauser introduce two constructs, calibration and discrimination, which they define as follows: ‘Calibration captures how well-estimated likelihoods compare to actual rates of occurrence … ’ and ‘discrimination measures how effectively analysts vary their assessments across cases’.Footnote90 Calibration is hypothesized to be positively related to rigorous analytic methodology, but this claim has yet to be substantiated. Hetherington and Dear argue that ‘ … failure to … evaluate the accuracy of British military intelligence predictions limits its effectiveness as an aid to commanders … ’,Footnote91 proposing a relationship between calibration and utility. One study conducted on calibration was Kajdasz’ experiment in which he determined the accuracy in terms of calibration of a group of 217 individuals and compared their performance with the calibration performance of different group sizes.Footnote92 He found that groups perform better than individuals in terms of calibration; in other words, groups provide more accurate predictions than individuals. More specifically, no individuals outperformed any group. He also found that calibration improves as the size of the group increases but shows diminishing returns on calibration as groups become larger. Unfortunately, no empirical study was found that explored factors influencing discrimination in the selection of this review. Thus, it remains unclear how, when, and why analyst vary their assessments across cases. Moreover, knowing what influences discrimination could yield valuable insights into the underlying dynamics of this construct.

The second perspective on precision examines an intelligence organization’s ability to communicate uncertainty accurately and unambiguously to policymakers. Mandel and Irwin argue that ‘ … not only does the analyst have to reason through uncertainties to arrive at sound and hopefully accurate judgments, but the uncertainties must also be clearly communicated to policymakers who must decide how to act on the intelligence’.Footnote93 On the one hand, this approach revolves around analyst’s adherence to pre-defined standards in communicating uncertainties when reporting them to customers. On the other hand, the approach examines linguistic expressions of uncertainties. It is ideally linked to probabilistic expressions to minimize the vagueness of the natural language and, therefore, accurately and unambiguously communicate uncertainty to intelligence customers. Decreasing the ambiguity when communicating uncertainty, in turn, theoretically increases the utility of intelligence. In a descriptive quantitative study, Dhami researches the use of linguistic probabilities by intelligence analysts. She shows that intelligence analysts use differing terminology when communicating uncertainty.Footnote94 This heterogeneity may increase the chances of miscommunication with intelligence consumers.

Rigor

In this paradigm, the effectiveness of intelligence is measured or determined through the degree of rigor of the process, and rigor can best be defined as following a correct process. Rigorous processes are alleged to enhance the precision of intelligence analysis, deepen comprehension of historical influences, increase analytic precision, refine decision-making, and ultimately yield favorable results.Footnote95 Two perspectives dominate the debate in this paradigm. The methods perspective of rigor views the effectiveness of intelligence as the rigorous adherence to methodology, contending that sound methods lead to desirable outputs. In contrast, advocates of standards reject the methods perspective because it leads to unwarranted standardization and institutionalization. The standards perspective deems intelligence effective when it adheres to prescribed standards of rigor. The perspectives, constructs, and antecedents of the rigor paradigm are summarized in .

Supporters of the methods perspective draw inspiration from Heuer’s work in the late 1990s.Footnote96 He identified the need to mitigate cognitive biases, explore multiple hypotheses using structured analytic techniques (SATs), and promote methodical critical thinking in intelligence analysis. Using SATs should enhance the quality of intelligence assessments by improving their accuracy and reliability. This perspective finds support in the conceptual literature under review. The aim of SATs, as described, is to enhance the quality of intelligence analysis by reducing cognitive biases among analysts. Similarly, proponents of these techniques argue that they provide cognitive strategies to help analysts address biases, make better decisions, and enhance intelligence assessments’ overall accuracy and reliability. Unfortunately, the effects on decision-making are not measured in studies in this review; neither are accuracy and reliability.

Other proponents advocate the use of a myriad of alternative methodologies. For instance, there is an endorsement of a more deliberate application of qualitative methodologies to enhance strategic analysis.Footnote97 Another argument revolves around using case studies to improve the quality of intelligence analysis and aid policymakers in understanding current threats and challenges.Footnote98 Additionally, suggestions are made to leverage recent insights from historians and social scientists in intelligence analysis.Footnote99 A structured approach to intelligence analysis, exemplified by NORDIS’s model, aims to make uncertain estimates more precise,Footnote100 while an indicator and warning methodology is endorsed to minimize the risk of intelligence failures.Footnote101 In a more specific context, there are proposals to evaluate the methodological validity and robustness of the widely used SAT ACH (Analysis of Competing Hypotheses). As with the traditional SATs, the effects on decision making, accuracy, nor reliability are measured in studies in this review.Footnote102

In contrast, studies in this review examine the use of methods as an antecedent to two constructs: bias reduction and reasoning quality. When using the construct of bias reduction, the assumption is that it will positively impact the effectiveness of intelligence and will eventually yield better accuracy and reliability. An example of such a study is Whitesmith’s study on the effectiveness of a structured analytical method, specifically the Analysis of Competing Hypotheses (ACH) and its relation to serial position effects and confirmation bias.Footnote103 She concludes that this technique does not mitigate these cognitive biases. This conclusion is supported by Coulthart, who finds mixed results in ACH’s ability to mitigate biases is questionable in a systematic review of six frequently used SATs.Footnote104 In addition, he finds SATs such as brainstorming A/B teaming to be mostly ineffective in mitigating biases in analysts. On the other hand, he finds some evidence that Devils Advocacy, Red Teaming and Alternative Futures Analysis are effective bias mitigating techniques.

When using the construct of reasoning quality, the first assumption is that it is a predictor of Heuer’s reliability. Reasoning quality, in turn, is positively related to adherence to methods. Stromer-Galley et al. study the effect of adherence to SATs on reasoning quality in analytic intelligence products.Footnote105 They find that using SATs leads to a higher quality of reasoning than unaided reasoning. They also find that more flexibility in the selection of SATs to use leads to improved reasoning quality compared to a predefined and standardized sequence of SAT’s. The second assumption is that increased reliability is positively associated with decision-making quality. Kruger et al. examined the relation between reasoning quality and decision-making quality.Footnote106 They find that training is positively associated with reasoning quality, while reasoning quality leads to better alignment of communicated risks and mitigation strategies and, subsequently, better decisions.

Most research in the methods perspective examines effectiveness at the process or product level. How these constructs extend to intelligence organizations, however, is unclear. In addition, little can be said about whether more rigorous processes matter in intelligence organizations because analysts rarely use SATs.Footnote107 There is a lack of evidence showing the use of SATs in intelligence organizations, let alone whether intelligence organizations have institutionalized the use of SATs. The lack of institutionalization might suggest that the use of SATs yield no or only marginal benefits for intelligence organizations.

In contrast to the methods perspective, Breakspear contends that any effort to implement a standardized approach, such as the new proposed ‘standard’ definition, carries the risk of narrowing intelligence practices, making them less intuitive and more procedural. This could lead to the certification of methods based on the false notion that there is a single correct method for conducting intelligence analysis.Footnote108 Supporters of the standards approach to rigor emphasize that the effectiveness of intelligence is contingent on its objectivity, neutrality, accuracy, persuasiveness, timeliness, and relevance.Footnote109 In the US, analytic standards are described in the Intelligence Community Directive 203 (ICD 203), developed as a result of deficiencies in intelligence production surrounding al-Qaida’s September 11 attacks and the faulty assessments of Iraq’s weapon of mass destruction program and are regularly updated.Footnote110 ICD 203 imposes five analytic standards to which analysis in the US must adhere, and it prescribes that analysis is objective, independent of political consideration, timely, based on all-source intelligence, and that it applies tradecraft standards.Footnote111 In an attempt to ascertain the efficacy of ODNI reforms, Gentry concludes that implementing ICD 206 has led to limited enhancements in the operational performance of intelligence organizations.Footnote112 Specifically, less proficient analysts have increased their performance through adherence to ODNI standards, albeit slightly, by enabling them to avoid fundamental errors. However, these standards have had a marginal influence in improving analysis. In addition, he finds little evidence that adherence to ODNI standards has reduced the analytic failures over the past decades. Unfortunately, Gentry’s study does not give a measure of standards adherence.

In contrast, Mandel et al. examined the degree of adherence in a quantitative correlational study that examined the correlation between personal and organizational compliance to analytical standards, conscientiousness, actively open-minded thinking, organizational commitment, and job satisfaction.Footnote113 Their findings suggest personal and perceived organizational compliance was high. In addition, they find that personal compliance is correlated to conscientiousness and actively open-minded thinking, while perceived organizational compliance is related to organizational commitment and job satisfaction. Whether adherence to standards leads to improvements in decision-making, accuracy, or reliability remains unsubstantiated and relies heavily on anecdotal evidence.

Discussion

The results of this review indicate that the paradigms of intelligence effectiveness are interrelated, which becomes clearer when examining the underlying assumptions and the predictions of the paradigms. They predict that appropriate inputs should benefit rigor, which in turn should lead to improved precision and more utility for decisionmakers, and improved precision is also hypothesized to directly lead to greater utility. In addition, these assumptions indicate that the paradigms could be sequenced to align with an input-process-output-outcome framework, called the Logic Model. This model is used in organizational theory as an effectiveness measurement framework by many business-like approaches.Footnote114 The paradigms and their constructs could be categorized along the lines of this framework. Sequencing the constructs in that manner may provide us with more fine-grained insights into the interrelation between the paradigms and may simultaneously reveal gaps in our knowledge.

Sequencing the constructs along the lines of input, process, output, and outcome unveils the following. Most paradigms of intelligence effectiveness agree that appropriate inputs may consist of personal traits and training of intelligence personnel, structure and content of intelligence requirements, accuracy and volume of information used, and a variety of organizational factors. These insights are most prominently expressed in the intelligence failure paradigm. Studies in this paradigm have found that intelligence failures are caused by poor analytic tradecraft, inferior quality and restricted availability of sources, and counterproductive organizational factors. Surprisingly, the intelligence failure paradigm does not measure the degree of intelligence failure. It measures factors present or absent when failure occurs, apparently focusing exclusively on intelligence inputs. Focusing mostly on process, the rigor paradigm in contrast disregards appropriate inputs, even though work in the intelligence failure paradigm has shown that appropriate inputs are a prerequisite for the sound execution of the intelligence process. Rigor contends that intelligence effectiveness is attained through improving analytic processes and solely concentrates on how rigor reduces biases and mental pitfalls. The hypothesis is that bias reduction will positively impact the intelligence effectiveness through improved decision-making and increased precision. However, this hypothesis remains untested. Furthermore, the paradigm predicts that rigor is positively related to utility and precision. This relationship is also predicted by the precision, intelligence failure, and the utility paradigm. Lastly, improved precision is also hypothesized to directly lead to greater utility. Precision can be considered an output measure and is viewed as accuracy of prediction and as the ability to communicate uncertainty accurately and unambiguously. Both factors are expected have a positive causal relation to utility, which can be considered an outcome measure. Although the relation between accuracy of prediction and utility remains merely a hypothesis, there is evidence that ambiguous terminology when communicating uncertainty may increase the chances of miscommunication with intelligence consumers, decreasing utility. Scholars of the utility paradigm have found similar evidence. Actionability, a construct of the utility paradigm, is argued to be positively related to information accuracy. In addition, utility of intelligence lies partly in its ability to reduce uncertainty for decision makers by making more accurate predictions.

Sequencing the constructs using the input-process-output-outcome framework also reveals gaps in our knowledge, such as: How do inputs (e.g., information volume or quality, training, experience, personal traits, organizational factors, and systems etc.) affect rigor, precision, and utility? Do more rigorous processes lead to increased precision in intelligence organizations? In what way does more precision lead to more utility? To what extent is rigor related to utility? What organizational factors in intelligence organizations lead to rigor, precision, and utility improvement? In essence the logic model may provide some direction for future research by helping researchers to think about how constructs of intelligence fit together as a part of intelligence processes. Moreover, by studying intelligence as a process the logic model may aid to conceptualize intelligence processes enhancing our understanding of how intelligence organizations are structured. As the logic model is a generic model of production processes of organizations, approaching activities through this lens might also accelerate ongoing professionalization efforts of intelligence organizations. In doing so future research may find the need to define new constructs to determine the relationship between the paradigms of intelligence effectiveness.

Conclusion

The aim of this paper was twofold. First, it aimed to establish effectiveness concepts in intelligence and, second, gain greater insight into how these concepts were operationalized. It identified four distinct paradigms of effectiveness: utility, intelligence failure, precision, and rigor. The utility paradigm contends that the effectiveness of intelligence is determined by the actionability of intelligence, its knowledge-producing or sensemaking ability, its degree of uncertainty reduction, and the degree to which governance mechanisms ensure public spending on intelligence contributes to national security. These measures of effectiveness are difficult to quantify and rely in part on subjective constructs such as actionability, sensemaking, and uncertainty reduction. The paradigm of intelligence failures comes in two forms: either failure is the result of inaccurate prediction or the failure to act on intelligence. The strength of this paradigm is that it has identified many antecedents that influence effectiveness. However, this paradigm disregards uncertainty and addresses effectiveness from a binary stance. The paradigm of precision views effectiveness either as the accuracy of prediction or the ability to communicate uncertainty accurately and unambiguously, and both are hypothesized to positively affect utility. But this paradigm is mostly product- or analyst-oriented. It addresses mainly the micro-level of organizational analyses, and very little research is done on how precision differs across intelligence organizations. The last paradigm is rigor, which claims that intelligence effectiveness is about the process’s rigor. This paradigm is split between the debate of adherence to methods and adherence to standards but fails to define what effectiveness is other than the implied adherence to these standards or methods.

The results of this review show that the paradigms of intelligence effectiveness are interrelated. Moreover, the paper suggests that the paradigms and their constructs can be sequenced along the lines of the Logic Model from organizational theory. Sequencing in this manner also reveals gaps in our knowledge, such as do better inputs lead to better rigor, does improved rigor make for improve precision and more utility, and does increase precision yield more utility. In addition, it identified the possible need to define new constructs o determine the relationship between the paradigms of intelligence effectiveness. Our knowledge of intelligence effectiveness will benefit from filling these gaps in our knowledge. Furthermore, addressing these gaps may contribute to a framework for assessing intelligence effectiveness which may benefit from the body of knowledge in organizational theory as it contains much work on effectiveness measurement.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Sebastiaan Rietjens, Robert Beeres, and three anonymous reviewers for their insightful remarks during discussions and their feedback on earlier versions of this paper. Earlier versions of this paper were presented at the IAFIE Conference in Copenhagen in 2023, the NISA Conference in Amsterdam in 2023 and the ISA Conference in San Francisco in 2024.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Gideon Manger

Gideon Manger is a PhD candidate at the Graduate School of the Faculty of Governance and Global Affairs, Leiden University, Leiden, the Netherlands, and the Netherlands Defence Academy, Breda, the Netherlands. His research addresses intelligence performance measurement frameworks in intelligence organizations. As an officer in the Royal Netherlands Army, he currently serves as head of the analysis department at the Intelligence and Security Academy in ‘t Harde, the Netherlands, teaching qualitative and quantitative intelligence analysis. He holds a master’s degree in economics from Maastricht University, the Netherlands.

Notes

1. Wilson et al., A Literature Review on the Effectiveness and Efficiency of Business Modeling. & Gorschek, Citation2018

2. Marrin, “Improving Intelligence Studies as an Academic Discipline,” Marrin, “Evaluating intelligence theories: current state of play’, —, ‘Is Intelligence Analysis an Art or a Science?.”

3. Eiran, “Dangerous Liaison: The 1973 American intelligence failure and the limits of intelligence cooperation,” ; Gill, “Explaining Intelligence Failure: Rethinking the Recent Terrorist Attacks in Europe.”

4. de Valk and Goldbach, “Towards a robust β research design: on reasoning and different classes of unknowns.”

5. Lowenthal and Marks, “Intelligence Analysis: Is It As Good As It Gets?,” Marchio, “’How good is your batting average?’ Early IC Efforts To Assess the Accuracy of Estimates.”

6. Whitesmith, “Experimental Research in Reducing the Risk of Cognitive Bias in Intelligence Analysis,” Coulthart, “An Evidence-Based Evaluation of 12 Core Structured Analytic Techniques.”

7. Cayford and Pieters, “Effectiveness fettered by bureaucracy: why surveillance technology is not evaluated,” Marrin, “Is Intelligence Analysis an Art or a Science?.”

8. Bruijn, Managing performance in the public sector, Rietjens et al., “Measuring the Immeasurable? The Effects-Based Approach in Comprehensive Peace Operations.”

9. Caceres-Rodriguez and Landon-Murray, “Charting a research agenda for intelligence studies using public administration and organization theory scholarship,” 150.

10. Landon-Murray and Caceres-Rodriguez, “Building Research Partnerships to Bridge Gaps between the Study of Organizations and the Practice of Intelligence,” 25.

11. Mandel and Tetlock, “Correcting judgment correctives in national security intelligence,” 4. Wheaton, “Evaluating Intelligence: Answering Questions Asked and Not,” 619.

12. Tranfield et al., “Towards a Methodology for Developing Evidence-Informed Management Knowledge by Means of Systematic Review.”

13. Horlings, “Dealing with data: coming to grips with the Information Age in Intelligence Studies journals.”

14. Rietjens, “Intelligence in defence organizations: a tour de force,”—.

15. Coulthart and Marrin, “Where to submit: a guide to publishing intelligence studies articles,”—.

16. Horlings, “Dealing with data: coming to grips with the Information Age in Intelligence Studies journals.”

17. Rietjens, “Intelligence in defence organizations: a tour de force.”

18. Articles on covert action were not included because these are activities resulting from intelligence processes, as are policy, mitigating activities or military decisions. The effectiveness of these activities does not necessarily say something about how well the intelligence function has performed. Moreover, covert action is not something that is proprietary to intelligence organizations. Special operations forces execute similar missions. Sometimes under the leadership of intelligence organizations.

19. Van Puyvelde and Curtis, “Standing on the shoulders of giants’: diversity and scholarship in Intelligence Studies.”

20. Finland and Sweden are not included in the set of NATO allies or non-NATO US allies because of their policy of neutrality up until they applied to be a NATO member in 2023.

21. Van Puyvelde and Curtis, “’Standing on the shoulders of giants’: diversity and scholarship in Intelligence Studies.”

22. Ibid., Tuinier, “Explaining the depth and breadth of international intelligence cooperation: towards a comprehensive understanding’,—, Rietjens, ‘Intelligence in defence organizations: a tour de force’, Horlings, ‘Dealing with data: coming to grips with the Information Age in Intelligence Studies journals.”

23. Cayford and Pieters, “Effectiveness fettered by bureaucracy: why surveillance technology is not evaluated,” 1027.

24. Gentry and Gordon, “U.S. Strategic Warning Intelligence: Situation and Prospects,” 26, ; Gill, “The way ahead in explaining intelligence organization and process,” 575, de Valk and Goldbach, “Towards a robust β research design: on reasoning and different classes of unknowns,” 73, and Vrist Rønn, “(Mis-) Informed Decisions? on Epistemic Reasonability of Intelligence Claims,” 353.

25. Chang, “Fixing Intelligence Reforming the Defense Intelligence Enterprise for Better Analysis,” ; Lowenthal and Marks, “Intelligence Analysis: Is It As Good As It Gets?,” Mandel and Tetlock, “Correcting judgment correctives in national security intelligence,” ; Marchio, “’How good is your batting average?’ Early IC Efforts To Assess the Accuracy of Estimates,” and Mandel and Irwin, “Uncertainty, Intelligence, and National Security Decisionmaking.”

26. Marrin, “Is Intelligence Analysis an Art or a Science?.”

27. Gainor and Bouthillier, “Competitive Intelligence Insights for Intelligence Measurement,” 591.

28. Salmi, “Why Europe Needs Intelligence and Why Intelligence Needs Europe: ‘Intelligence Provides Analytical Insight into an Unpredictable and Complex Environment,’” 4.

29. Work, “Evaluating Commercial Cyber Intelligence Activity,” 292.

30. Saito, “Japanese Navy’s Tactical Intelligence Collection on the Eve of the Pacific War.”

31. Palfy, “Bridging the Gap between Collection and Analysis: Intelligence Information Processing and Data Governance,”; Van Puyvelde, “Fusing drug enforcement: a study of the El Paso Intelligence Center.”

32. Saito, “Japanese Navy’s Tactical Intelligence Collection on the Eve of the Pacific War.”

33. Van Puyvelde, “Fusing drug enforcement: a study of the El Paso Intelligence Center.”

34. Palfy, “Bridging the Gap between Collection and Analysis: Intelligence Information Processing and Data Governance.”

35. Omand, “Reflections on Intelligence Analysts and Policymakers,” 472.

36. Chang, “Fixing Intelligence Reforming the Defense Intelligence Enterprise for Better Analysis,” 86.

37. Turcotte, “’An important contribution to the allied war effort’: Canadian and North Atlantic intelligence on German POWs, 1940–1945.”

38. Hamm, “British Intelligence in the Middle East, 1898–1906,” 899.

39. Ben-Gad et al., “Allocating Security Expenditures under Knightian Uncertainty: An Info-Gap Approach,” ; Spoor and Rothman, “On the critical utility of complexity theory in intelligence studies.”

40. Izquierdo Triana et al., “Audit of a Competitive Intelligence Unit,” 228.

41. Ben-Gad et al., “Allocating Security Expenditures under Knightian Uncertainty: An Info-Gap Approach,” 846.

42. Acuff and Nowlin, “Competitive intelligence and national intelligence estimates.”

43. Wolfberg, “When generals consume intelligence: the problems that arise and how they solve them,” 474.

44. Pecht and Tishler, “The value of military intelligence,” 183.

45. Steinhart and Avramov, “Is Everything Personal?: Political Leaders and Intelligence Organizations: A Typology,” 534.

46. Brunatti, “The architecture of community: Intelligence community management in Australia, Canada and New Zealand,” 135.

47. Yauri-Miranda, “Principles to Assess Accountability: A Study of Intelligence Agencies in Spain and Brazil,” 594.

48. Cepik, “Bosses and Gatekeepers: A Network Analysis of South America’s Intelligence Systems,” 703.

49. Honig and Zimskind, “The Spy Machine and the Ballot Box: Examining Democracy’s Intelligence Advantage,” 457.

50. Thomson, “Governance costs and defence intelligence provision in the UK: a case-study in microeconomic theory,” 855.

51. Steinhart and Avramov, “Is Everything Personal?: Political Leaders and Intelligence Organizations: A Typology.”

52. Gilad et al., “Intelligence, Cyberspace, and National Security,” 22.

53. Ibid., 36.

54. Vrist Rønn, “(Mis-) Informed Decisions? on Epistemic Reasonability of Intelligence Claims.”

55. Ikani et al., “An analytical framework for postmortems of European foreign policy: should decision-makers have been surprised?,” 198.

56. Calista, “Enduring Inefficiencies in Counterintelligence by Reducing Type I and Type II Errors Through Parallel Systems: A Principal-Agent Typology,” Eiran, “The Three Tensions of Investigating Intelligence Failures,” ; de Valk and Goldbach, “Towards a robust β research design: on reasoning and different classes of unknowns,” Vrist Rønn, “(Mis-) Informed Decisions? on Epistemic Reasonability of Intelligence Claims.”

57. Arcos and Palacios, “The impact of intelligence on decision-making: the EU and the Arab Spring,” Mettler, “Return of the Bear Learning from Intelligence Analysis of the USSR to Better Assess Modern Russia,” and Wirtz, ‘The Art of the Intelligence Autopsy’.

58. Stivi-Kerbis, “The Surprise of Peace: The Challenge of Intelligence in Identifying Positive Strategic – Political Shifts,” 453.

59. Karam, “Missing revolution: the American intelligence failure in Iraq, 1958,” 704.

60. Faini, “The US Government and the Italian coup manqué of 1964: the unintended consequences of intelligence hierarchies,” 1024.

61. Eiran, “Dangerous Liaison: The 1973 American intelligence failure and the limits of intelligence cooperation,” 221.

62. E.g —, “The Three Tensions of Investigating Intelligence Failures,” Vrist Rønn, “(Mis-) Informed Decisions? on Epistemic Reasonability of Intelligence Claims”, and ; Wirtz, “The Art of the Intelligence Autopsy.”

63. Wilson et al., “Health security warning intelligence during first contact with COVID: an operations perspective,”—.

64. Connelly et al., “New evidence and new methods for analyzing the Iranian revolution as an intelligence failure,” ; Lillbacka, “The Finnish Intelligence Failure on the Karelian Isthmus in 1944,” Wilkinson, “Nerve agent development: a lesson in intelligence failure?.”

65. McDermott and Bar-Joseph, “Pearl Harbor and Midway: the decisive influence of two men on the outcomes.”

66. Karam, “Missing revolution: the American intelligence failure in Iraq, 1958.”

67. Stivi-Kerbis, “The Surprise of Peace: The Challenge of Intelligence in Identifying Positive Strategic – Political Shifts.”

68. Borer et al., “Problems in the Intelligence-Policy Nexus: Rethinking Korea, Tet, and Afghanistan.”

69. Barnea and Meshulach, “Forecasting for Intelligence Analysis: Scenarios to Abort Strategic Surprise.”

70. Lillbacka, “The Finnish Intelligence Failure on the Karelian Isthmus in 1944,” Gill, “Explaining Intelligence Failure: Rethinking the Recent Terrorist Attacks in Europe,” Lefebvre, “’The Belgians Just Aren’t up to It’: Belgian Intelligence and Contemporary Terrorism,” and Gordon, “Developing Managers of Analysts: The Key to Retaining Analytic Expertise,”.

71. Ingesson, “Beyond Blame: What Investigations of Intelligence Failures Can Learn from Aviation Safety,”

72. Libel, “Looking for meaning: lessons from Mossad’s failed adaptation to the post-Cold War era, 1991–2013.”

73. Gentry, “The intelligence of fear,” 9.

74. Borer et al., “Problems in the Intelligence-Policy Nexus: Rethinking Korea, Tet, and Afghanistan.”

75. Ikani et al., “An analytical framework for postmortems of European foreign policy: should decision-makers have been surprised?.”

76. Connelly et al., “New evidence and new methods for analyzing the Iranian revolution as an intelligence failure,” 782.

77. Dahl, “Why Won’t They Listen? Comparing Receptivity Toward Intelligence at Pearl Harbor and Midway,” 87.

78. Ikani et al., “An analytical framework for postmortems of European foreign policy: should decision-makers have been surprised?,” 207.

79. Gradon and Moy, “COVID-19 Response – Lessons from Secret Intelligence Failures.”

80. Ryan, “Wilful Blindness or Blissful Ignorance? The United States and the Successful Denuclearization of Iraq.”

81. Ikani et al., “An analytical framework for postmortems of European foreign policy: should decision-makers have been surprised?,” ; Ostergard, “The West Africa Ebola outbreak (2014–2016): a Health Intelligence failure?.”.

82. Connelly et al., “New evidence and new methods for analyzing the Iranian revolution as an intelligence failure,” ; Wilson et al., “Influenza pandemic warning signals: Philadelphia in 1918 and 1977–1978,” Wilson and McNamara, “The 1999 West Nile virus warning signal revisited.”

83. Ostergard, “The West Africa Ebola outbreak (2014–2016): a Health Intelligence failure?.”

84. Wilson et al., “Influenza pandemic warning signals: Philadelphia in 1918 and 1977–1978,” Wilson and McNamara, “The 1999 West Nile virus warning signal revisited.”

85. Connelly et al., “New evidence and new methods for analyzing the Iranian revolution as an intelligence failure.”

86. Chang, “Fixing Intelligence Reforming the Defense Intelligence Enterprise for Better Analysis.”

87. Marchio, “’How good is your batting average?’ Early IC Efforts To Assess the Accuracy of Estimates,” 3.

88. Mandel and Irwin, “Uncertainty, Intelligence, and National Security Decisionmaking.”

89. Chang, “Getting It Right Assessing the Intelligence Community’s Analytic Performance,” Friedman and Zeckhauser, “Why Assessing Estimative Accuracy is Feasible and Desirable,” Hetherington and Dear, “Assessing Assessments How Useful Is Predictive Intelligence?,” ; Speigel, “Adopting and improving a new forecasting paradigm,” and ; Lowenthal and Marks, “Intelligence Analysis: Is It As Good As It Gets?.”

90. Friedman and Zeckhauser, “Why Assessing Estimative Accuracy is Feasible and Desirable,” 185.

91. Hetherington and Dear, “Assessing Assessments How Useful Is Predictive Intelligence?,” 116.

92. Kajdasz, “A Demonstration of the Benefits of Aggregation in an Analytic Task.”

93. Mandel and Irwin, “Uncertainty, Intelligence, and National Security Decisionmaking,” 559.

94. Dhami, “Towards an evidence-based approach to communicating uncertainty in intelligence analysis,” 257.

95. Marrin, “Understanding and improving intelligence analysis by learning from other disciplines.”

96. Heuer, Psychology of intelligence analysis.

97. Walsh, “Improving strategic intelligence analytical practice through qualitative social research.”

98. Dahl, “Getting beyond analysis by anecdote: improving intelligence analysis through the use of case studies.”

99. Aldrich, “Strategic culture as a constraint: intelligence analysis, memory and organizational learning in the social sciences and history.”

100. Borg, “Improving Intelligence Analysis: Harnessing Intuition and Reducing Biases by Means of Structured Methodology.”

101. Wirtz, “Indications and Warning in an Age of Uncertainty.”

102. Jones, “Critical epistemology for Analysis of Competing Hypotheses.”

103. Whitesmith, “The efficacy of ACH in mitigating serial position effects and confirmation bias in an intelligence analysis scenario” Whitesmith “Experimental Research in Reducing the Risk of Cognitive Bias in Intelligence Analysis.”

104. Coulthart, “An Evidence-Based Evaluation of 12 Core Structured Analytic Techniques.”

105. Stromer-Galley et al., “Flexible versus structured support for reasoning: enhancing analytical reasoning through a flexible analytic technique.”

106. Kruger et al., “Using argument mapping to improve clarity and rigour in written intelligence products.”

107. Coulthart, “Why do analysts use structured analytic techniques? An in-depth study of an American intelligence agency,” Arcos and Palacios, “The impact of intelligence on decision-making: the EU and the Arab Spring,” Marchio, “Analytic Tradecraft and the Intelligence Community: Enduring Value, Intermittent Emphasis”.

108. Breakspear, “A New Definition of Intelligence,” 689.

109. Simon, “Intelligence Analysis as Practiced by the CIA,” ; Manjikian, “Positivism, Post-Positivism, and Intelligence Analysis,” Irwin and Mandel, “Improving information evaluation for intelligence production.”

110. Zulauf, “From a Former ODNI Ombudsperson Perspective: Safeguarding Objectivity in Intelligence Analysis,” 36, Marrin, “Analytic objectivity and science: evaluating the US Intelligence Community’s approach to applied epistemology,” 2.

111. Zulauf, “From a Former ODNI Ombudsperson Perspective: Safeguarding Objectivity in Intelligence Analysis,” 36.

112. Gentry, “Has the ODNI Improved U.S. Intelligence Analysis?.”

113. Mandel et al., “Policy for promoting analytic rigor in intelligence: professionals” views and their psychological correlates”.

114. Beeres and Bogers, “Ranking the Performance of European Armed Forces,” ; Soares et al., “The defence performance measurement framework: measuring the performance of defence organisations at the strategic level,” Rietjens et al., “Measuring the Immeasurable? The Effects-Based Approach in Comprehensive Peace Operations.”

Bibliography

- Acuff, J. M., and M. J. Nowlin. “Competitive Intelligence and National Intelligence Estimates.” Intelligence and National Security 34, no. 5 July 29, 2019. 654–672.

- Aldrich, R. J. “Strategic Culture As a Constraint: Intelligence Analysis, Memory and Organizational Learning in the Social Sciences and History.” Intelligence and National Security 32, no. 5 July 29, 2017. 625–635.

- Arcos, R., and J.-M. Palacios. “The Impact of Intelligence on Decision-Making: The Eu and the Arab Spring.” Intelligence and National Security 33, no. 5 July 29, 2018. 737–754.

- Barnea, A., and A. Meshulach. “Forecasting for Intelligence Analysis: Scenarios to Abort Strategic Surprise.” International Journal of Intelligence & Counter Intelligence 34, no. 1 January 2, 2021. 106–133.

- Beeres, R., and M. Bogers. “Ranking the Performance of European Armed Forces.” Defence and Peace Economics 23, no. 1 (2012): 1–16.

- Ben-Gad, M., Y. Ben-Haim, and D. Peled. “Allocating Security Expenditures Under Knightian Uncertainty: An Info-Gap Approach.” Defence and Peace Economics 31, no. 7 October 2, 2020. 830–850.

- Borer, D. A., S. Twing, and R. P. Burkett. “Problems in the Intelligence-Policy Nexus: Rethinking Korea, Tet, and Afghanistan.” Intelligence and National Security 29, no. 6 November 2, 2014. 811–836.

- Borg, L. C. “Improving Intelligence Analysis: Harnessing Intuition and Reducing Biases by Means of Structured Methodology.” The International Journal of Intelligence, Security, and Public Affairs 19, no. 1 January 2, 2017. 2–22.

- Breakspear, A. “A New Definition of Intelligence.” Intelligence and National Security 28, no. 5 October 1, 2013. 678–693.

- Bruijn, J. A. D. Managing Performance in the Public Sector. [in Engels] London: Routledge, 2002.

- Brunatti, A. D. “The Architecture of Community: Intelligence Community Management in Australia, Canada and New Zealand.” Public Policy and Administration 28, no. 2 (2013): 119–143.

- Caceres-Rodriguez, R., and M. Landon-Murray. “Charting a Research Agenda for Intelligence Studies Using Public Administration and Organization Theory Scholarship.” In Researching National Security Intelligence: Multidisciplinary Approaches, edited by S. Coulthart, M. Landon-Murray and D. Van Puyvelde, 141–162. 2019.

- Calista, D. J. “Enduring Inefficiencies in Counterintelligence by Reducing Type I and Type Ii Errors Through Parallel Systems: A Principal-Agent Typology.” International Journal of Intelligence & CounterIntelligence 27, no. 1 March 1, 2014. 109–131.

- Cayford, M., and W. Pieters. “Effectiveness Fettered by Bureaucracy: Why Surveillance Technology Is Not Evaluated.” Intelligence and National Security 35, no. 7 November 9, 2020. 1026–1041.

- Cepik, M. “Bosses and Gatekeepers: A Network Analysis of South America’s Intelligence Systems.” International Journal of Intelligence & CounterIntelligence 30, no. 4 October 2, 2017. 701–722.

- Chang, W. “Getting it Right Assessing the Intelligence Community’s Analytic Performance.” American Intelligence Journal 30, no. 2 (2012): 99–108.

- Chang, W. “Fixing Intelligence Reforming the Defense Intelligence Enterprise for Better Analysis.” American Intelligence Journal 31, no. 1 (2013): 86–90.

- Connelly, M., R. Hicks, R. Jervis, and A. Spirling. “New Evidence and New Methods for Analyzing the Iranian Revolution As an Intelligence Failure.” Intelligence and National Security 36, no. 6 September 19, 2021. 781–806.

- Coulthart, S. “Why Do Analysts Use Structured Analytic Techniques? An In-Depth Study of an American Intelligence Agency.” Intelligence and National Security 31, no. 7 November 9, 2016. 933–948.

- Coulthart, S. J. “An Evidence-Based Evaluation of 12 Core Structured Analytic Techniques.” International Journal of Intelligence & CounterIntelligence 30, no. 2 April 3, 2017. 368–391.

- Coulthart, S., and S. Marrin. “Where to Submit: A Guide to Publishing Intelligence Studies Articles.” Intelligence and National Security 38, no. 4 (2023): 643–53.

- Dahl, E. J. “Getting Beyond Analysis by Anecdote: Improving Intelligence Analysis Through the Use of Case Studies.” Intelligence and National Security 32, no. 5 July 29, 2017. 563–578.

- Dahl, E. J. “Why Won’t They Listen? Comparing Receptivity Toward Intelligence at Pearl Harbor and Midway.” Intelligence and National Security 28, no. 1 February 1, 2013. 68–90.

- Daniel, I., and D. R. Mandel. “Improving Information Evaluation for Intelligence Production.” Intelligence and National Security 34, no. 4 June 7, 2019. 503–525.

- de Valk, G., and O. Goldbach. “Towards a Robust Β Research Design: On Reasoning and Different Classes of Unknowns.” Journal of Intelligence History 20, no. 1 January 2, 2021. 72–87.

- Dhami, M. K. “Towards an Evidence-Based Approach to Communicating Uncertainty in Intelligence Analysis.” Intelligence and National Security 33, no. 2 February 23, 2018. 257–272.

- Eiran, E. “Dangerous Liaison: The 1973 American Intelligence Failure and the Limits of Intelligence Cooperation.” Journal of Intelligence History 19, no. 2 July 2, 2020. 213–228.

- Eiran, E. “The Three Tensions of Investigating Intelligence Failures.” Intelligence and National Security 31, no. 4 June 6, 2016. 598–618.

- Faini, M. “The Us Government and the Italian Coup Manqué of 1964: The Unintended Consequences of Intelligence Hierarchies.” Intelligence and National Security 31, no. 7 November 9, 2016. 1011–1024.

- Friedman, J. A., and R. Zeckhauser “Why Assessing Estimative Accuracy Is Feasible and Desirable.” Intelligence and National Security 31, no. 2 February 23, 2016. 178–200.

- Gainor, R., and F. Bouthillier. “Competitive Intelligence Insights for Intelligence Measurement.” International Journal of Intelligence & CounterIntelligence 27, no. 3 September 1, 2014. 590–603.

- Gentry, J. A. “Has the Odni Improved U.S. Intelligence Analysis?.” International Journal of Intelligence & CounterIntelligence 28, no. 4 02 date-in-citation. October 2015. 637–661.

- Gentry, J. A. “The Intelligence of Fear.” Intelligence and National Security 32, no. 1 January 2, 2017. 9–25.