ABSTRACT

Background: Aphasia and other acquired language impairments have the potential to impact greatly on quality of life by disrupting everyday conversation. Different intervention approaches are available to speech and language therapists (SLTs), such as targeting the language impairment itself and/or addressing activity or participation barriers. Conversation therapy is one approach that is gaining in popularity, with a growing evidence base. However, it is not clear how SLTs currently use conversation approaches and what factors may influence delivery.

Aims: To investigate how SLTs (i) define conversation therapy, (ii) deliver it in clinical practice, and identify (iii) any challenges faced.

Methods & Procedures: An online survey and focus group explored how SLTs working in the south east of England currently deliver conversation therapy to support people with a range of communication disorders, in particular aphasia. Data were analysed using descriptive statistics and thematic content analysis.

Outcomes & Results: A total of 50 SLTs completed the survey and 6 participants attended the focus group. Conversation therapy was found to be widely employed by participants, however there was considerable variation in the approaches used, and a number of major challenges were raised. SLTs reported delivering conversation therapy with a range of client groups and preferably working with the client and partner together. Conversation goals predominantly reflected an approach based on: (i) strategy use and/or total communication (TC), and (ii) Conversation Analysis. Three overarching themes around conversation therapy emerged from the focus group: (1) What is conversation therapy? (2) showing it works, and (3) complexities of delivering it. SLTs acknowledged the benefit of conversation therapy but felt they lacked the tools and skills needed to deliver it.

Conclusions: SLTs wanted to use conversation therapy and desired clear outcome measures to demonstrate its effectiveness, but were not accessing the available evidence base, highlighting the ongoing difficulty of translating research into clinical practice. Whilst these data are limited by the small number of participants, the study provides a first view of how conversation therapy is articulated in practice. Further investigation of conversation therapy delivery is warranted with a larger sample of SLTs based across the United Kingdom, as is comparison with practice in other countries.

Introduction

According to Wilkinson and Wielaert (Citation2012), aphasia rehabilitation should facilitate an individual’s ability to communicate within their everyday environment through holding conversations. Indeed, the ability to participate in conversation is a treatment outcome prioritised internationally by both people with aphasia and their family members (Wallace et al., Citation2016a). To achieve this, conversation must be targeted directly (Royal College of Speech and Language Therapists, Citation2005). One approach which has the capacity to target activity and participation whilst reducing environmental barriers is conversation therapy (Simmons-Mackie & Kagan, Citation2007). According to Simmons-Mackie (Citation2001, p. 254), conversation therapy constitutes “planned intervention that is explicitly designed to enhance conversational abilities”. Key features are its goal-directed and individualised nature. In a recent qualitative review, Simmons-Mackie, Savage, and Worrall (Citation2014) highlight a growing number of interventions under the umbrella of conversation therapy, based on different underlying theories, and utilising a variety of methods. Examples include interventions underpinned by Conversation Analysis (CA; see Wilkinson, Citation2014 for a review), group communication treatment (targeting initiation of conversation and information exchange) (Elman & Bernstein-Ellis, Citation1999), conversational coaching (Hopper, Holland, & Rewega, Citation2002), and conversation partner (CP) training (McVicker, Parr, Pound, & Duchan, Citation2009; Simmons-Mackie, Raymer, Armstrong, Holland, & Cherney, Citation2010; Turner & Whitworth, Citation2006). Published conversation training programmes include Supporting Partners of People with Aphasia in Relationships and Conversation (SPPARC; Lock, Wilkinson, & Bryan, Citation2001) and Supported Conversation for Adults with Aphasia (SCA™; Kagan, Citation1998). The SPPARC programme, grounded in CA, is individually tailored to a dyad’s conversation strengths and barriers via an initial analysis of a conversation sample. Training involves education about how conversation works, dyad self-reflection using video recordings of their own conversations, and practice of jointly identified strategies to deal with specific conversation barriers. SCA™ involves training partners to acknowledge the competence of speakers with aphasia using a natural and adult communicative style, using a range of generally applicable techniques and tools to facilitate responses, and is linked to observational outcome measures (Kagan et al., Citation2004). The ultimate goal is to provide access to good quality conversation to promote well-being and quality of life. CP training in particular has a robust evidence base (Simmons-Mackie et al., Citation2010; Simmons-Mackie, Raymer, & Cherney, Citation2016; Turner & Whitworth, Citation2006), and the Royal College of Physicians Intercollegiate Stroke Working Party (Citation2016) recommends it as an approach to enhance participation in social interaction for people with aphasia. Individual case studies provide early evidence that direct training of the person with aphasia(PWA) alongside their CP can also achieve positive change (see Beeke et al., Citation2015; Wilkinson, Lock, Bryan, & Sage, Citation2011). It is clear from the literature that despite a robust evidence base, conversation therapy research studies vary in implementation (Simmons-Mackie et al., Citation2010, Citation2016, Citation2014), and there is no “coherent synopsis” of conversation therapy research studies’ findings (Simmons-Mackie et al., Citation2014, p. 511).

Given the growing evidence base for conversation-based interventions, it is important to consider SLTs’ conversation therapy practices. A survey of aphasia clinicians from North America and Australia (Simmons-Mackie, Worrall, & Savage, Citation2013) reported frequent use of conversation therapy, but approaches and outcome measures varied considerably. Commonly reported approaches varied widely and included targeting conversation via discussion of current events, as well as conversation as a context for multimodality communication practice and strategy training. Survey participants showed an awareness of the evidence base for conversation therapy approaches with over half (52%) reporting that their learning in this area was drawn from reading the literature (Simmons-Mackie et al., Citation2013). Two studies of aphasia rehabilitation in Australia revealed interesting findings in relation to partner training. Rose, Ferguson, Power, Togher, and Worrall (Citation2014) reported relatively low use of and confidence in CP training, that is, 50% of the sample reported occasional to very rare use, just a little more than 50% reported being neutral to very unconfident. Conversely, large numbers of SLTs reported they were training family members to communicate with the PWA, but reported being unable to deliver more frequent and comprehensive CP training for a range of reasons (Rose et al., Citation2014). An earlier study by Verna, Davidson, and Rose (Citation2009) found that communication partner training was the second most frequently used aphasia intervention, and delivered across all settings. It was not clear however whether SLTs conducted actual CP training as no interactional assessment of the dyad or CP contribution was undertaken; and it is possible that SLTs were providing more general communication partner education (Verna et al., Citation2009). These findings raise an issue of whether SLTs distinguish between dyad-specific assessment-driven CP training, and generalised partner education without assessment. Indeed, an earlier study in North America (Simmons-Mackie, Threats, & Kagan, Citation2005) found that SLTs very infrequently used a conversation sample to measure outcomes of aphasia intervention. Finally, one UK study by Beckley, Best, and Beeke (Citation2016) touches on SLTs’ conversation therapy practices in a survey of broader approaches to communication strategy training in aphasia rehabilitation. The authors reported that SLTs consistently used “conversation with the SLT” as an intervention task to deliver communication strategy training, and that more training was conducted with clients than CPs who played a passive role in therapy sessions. However, given the broad focus on communication strategy intervention practices, including methods such as TC, it is not possible to extract practices specific to the delivery of conversation therapy, and further UK research is needed. In summary, it appears that SLTs do deliver conversation therapy, however assessment practices and therapeutic approaches vary, and SLTs’ reported practice is not consistently based on evidence (e.g., for assessment methods) that could support its delivery.

The survey reported here sought to identify current practice in conversation therapy and factors influencing this, including how SLTs defined conversation therapy and therefore the authors have not provided their own definition. Any qualified SLT currently working with adults in any clinical setting was invited to complete the survey; there was no requirement to have knowledge of conversation therapy although it may have been implied through association with a larger project (see later). Responses were anonymous to permit SLTs to answer honestly. A focus group complemented the survey by allowing more detailed exploration of the research questions (specifically questions 2 and 3, see later) with a group of SLTs who had an interest in conversation therapy. This study formed part of a larger project at University College London (UCL) to develop an e-learning resource—Better Conversations with Aphasia (BCA; Beeke et al., Citation2013) to support access to conversation therapy for SLTs, and people with aphasia and their families. The current study ensured that the needs of one of BCA’s main stakeholders, SLTs, were addressed in the development of the e-learning resource. The wider project also involved eliciting SLTs’ views on continuing professional development and e-learning; these data are not discussed here.

Aims

The aim was to gain insight into how SLTs working in the south east of England currently deliver conversation therapy to clients with a variety of communication disorders, and in particular those with aphasia. The research questions were:

How do SLTs define conversation therapy?

How do SLTs deliver conversation therapy, specifically (i) Which client groups do they currently use it with? (ii) Which participants are included? (iii) What assessments and approaches are commonly used?, and (iv) What areas of conversation are targeted?

What are the challenges for SLTs in delivering conversation therapy?

Research questions 1 and 2 were considered through the survey; question 3 was uniquely considered through the focus group, and questions 2 and 1 were further explored through focus group discussion.

Method

Participants

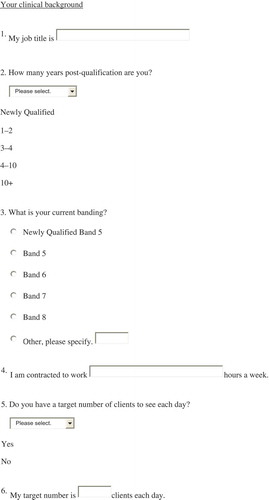

Fifty qualified SLTs working in the south east of England completed the survey and six then took part in the focus group (see for participant characteristics). The majority of participants held specialist roles, worked full time and were employed either at Band 6 or Band 7. In the United Kingdom, SLTs working in the National Health Service are banded from Band 5 (entry level) up to Band 8 (highly specialist with management responsibility), with Bands 6 and 7 defined as specialist and highly specialist, respectively.

Table 1. Participant characteristics.

Recruitment

Survey participants were targeted in a variety of ways. The survey link was distributed by email to: (1) people who had expressed interest in the BCA project after attending workshops on conversation therapy UCL for two London-based Clinical Excellence Networks (CENs) (Aphasia Therapy CEN, Domiciliary/Community CEN); (2) the general membership of those CENs; (3) the first author’s National Health Service colleagues; and (4) British Aphasiology Society members. Finally, the link was posted on the BCA project website, Twitter, and Facebook pages.

Focus group participants were recruited via the CEN study days mentioned earlier. A total of 22 SLTs registered their interest, and of those, 6 were able to attend. They worked in the Greater London area, and had previously completed the online survey. Background information was obtained using an anonymous profiling form.

Ethical issues and consent

The UCL Research Ethics Committee confirmed this project to be service evaluation. Participants in the focus group gave written consent to be video and audio recorded for the purposes of transcription and qualitative analysis, and survey respondents were informed that by undertaking the survey their consent was implied. All were advised that the resulting anonymous data would be used by the first author and the wider BCA team.

Data collection

Survey

An Opinio-based online survey method was chosen for ease of completion, and to maximise the number of respondents in the hope of capturing a broad landscape of current practice in conversation therapy. This method has been used successfully in previous SLT service evaluations (see, e.g., Collis & Bloch, Citation2012). A range of question formats was used including closed questions for factual information and open-ended questions for development of discussion.

Questions were selected and developed based on two key reviews of the conversation therapy evidence base available at the time, namely Simmons-Mackie et al. (Citation2010) and Wilkinson and Wielaert (Citation2012). Relevant published assessments and interventions such as the Conversation Analysis Profile for People with Aphasia (CAPPA; Whitworth, Perkins, & Lesser, Citation1997), SPPARC (Lock et al., Citation2001), and SCA™ (Kagan, Citation1998) were included to investigate their use, alongside informal methods. A definition of conversation therapy was not given to respondents because we wished to gain a picture of their own understandings of the approach, and to explore any lack of clarity that might exist. The final survey had 15 questions covering respondents’ clinical background and information regarding roles (to provide general context for the survey results), and current delivery of conversation therapy (see Appendix A). Respondents were asked to provide a conversation goal worked on with a client as a concrete example of their practice; to our knowledge this kind of evidence has not been collected before. The survey was piloted with two practising clinicians, and modifications were made including use of bold and italics to highlight keywords, a change in the order of some questions, and the addition of a comments box for others. The survey was available online between 19 August 2012 and 17 December 2012.

Focus group

Focus groups are a well-established method of exploring people’s knowledge and experience in healthcare research (Kitzinger, Citation1995; Parsons & Greenwood, Citation2000). This method was judged to be an ideal vehicle through which to gain a deeper understanding of SLTs’ experiences of using conversation therapy, to enhance the findings of the survey. Whilst the survey generated data on core practices including client groups receiving conversation therapy, and assessment and intervention practices, the focus group method permitted in-depth exploration of the richness of practice experiences of SLTs using conversation therapy, and the challenges involved (thereby targeting research questions 2 and 3, respectively). The first author led the focus group held at the university, and following the topic guide, participants discussed successful and unsuccessful experiences of using conversation therapy with clients, and their personal experience of the therapy process. They also discussed factors that facilitated or hindered carrying out conversation therapy and what could be changed to improve the experience. The second author and another member of the BCA team acted as assistant moderators, making field notes to support data analysis. These included observations on speakers’ body language, key quotes, and emerging themes.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics, predominantly frequency counts, were used to analyse responses to the first 14 survey questions. Open-ended text questions from the survey (questions 14b and 15), and focus group data were analysed using thematic content analysis, as recommended by Boynton (Citation2004). The analytic process was broken down into stages, outlined later. Survey respondents and focus group participant quotes are included in Results, indicated as P#.

Stage 1: Data were prepared for analysis. Text responses from the survey were exported from Opinio into Excel. The focus group was transcribed verbatim in its entirety by the first author, including body language (nodding and laughter). The assistant moderators’ field notes were used to clarify queries and identify notable participant comments. The transcript was imported into Nvivo 10 (QSR International), a qualitative data analysis software package. All participants were assigned a number to maintain anonymity, and data quoted in this paper are identified in this way.

Stage 2: Familiarisation with the data was achieved through reading and listening to the transcript and recording multiple times.

Stage 3: Units of data that portrayed key themes, either implicitly or explicitly, were highlighted. No limit was placed on the size of these; they ranged from a word through to several sentences. In a similar way, keywords in the textual survey responses were highlighted in italics. If a unit conveyed a novel idea then a theme was created, alternatively it was assigned to an existing theme.

One key difference between the analysis of focus group and survey data was that, for the focus group, a coded unit of data could be assigned to multiple themes if it was felt that different ideas were present, indicating a potential relationship between themes. However, a survey response was assigned to the single theme with which it had the strongest affiliation. This was due to the nature of the data; the shorter survey responses lent themselves to being assigned to one theme only.

Stage 4: Once created, themes were labelled. In order to retain the authenticity of the data, a participant’s own words were used where possible. Definitions were developed which explicitly described the nature of a theme and thereby facilitated coding transparency. For example, from the following participant comment the first author identified a key theme “measurement”, defined as SLTs discussing ways in which to measure the impact of conversation therapy:

And do you think if you could measure it similar to impairment level … do you think you’d be more successful at doing more of it? (P5)

Stage 5: Data are presented in figures and organised as themes, some of which incorporate sub-themes. For example, one response from survey question 15 (“To initiate conversation at least x2 per day with my husband” P15) was categorised into Theme 2 CA-based goals, under sub-theme 2.1 Topic Initiation.

Stage 6: The first author led the data analysis and, for rigour, an advisory group was established consisting of all authors (including an experienced qualitative researcher) and a member of the BCA team. This met at key stages to reach coding consensus through discussion. This was an iterative process with refinements made over a period of months. Data saturation was reached when the first author could no longer identify new themes and the group was satisfied that the coding of existing themes adequately captured the data.

Stage 7: Stages 7 and 8 refer only to the focus group data. Through discussion with the advisory group, three overarching themes were identified, each of which has sub-themes. The focus group findings are rich and detailed, and are thus presented across three separate figures (which report themes numbered 1, 2, and 3 across , , and , respectively).

Stage 8: Annotations were added to highlight themes that were felt to be highly representative of the group, that is, if three or more of the participants appeared to be in consensus (agreement or disagreement). Incidences of diverse or strong opinions were also noted.

Analysis was undertaken and agreed amongst the authorship team and advisory team. Coding and themes were not returned to focus group participants for comment or feedback; coding and themes could not be returned to survey respondents because of the anonymous online survey data collection mechanism.

Results

Survey results

The survey results are reported as follows: (1) survey respondents’ current roles (questions 5–8) and (2) conversation therapy delivery (questions 9–15), which includes discussion of assessment, approaches to intervention, and examples of goals. Multiple responses could be selected for questions 7–13. Questions 1–4 covered respondents’ characteristics. Of note, free text responses to question 14b were analysed and are presented in ; free text responses to question 15 were extensive, and were analysed and are presented in linked ,). All three figures present data arranged under themes, some of which include sub-themes. Descriptive findings are presented both as n and as percentages of the whole participant sample (N = 50).

Survey respondents

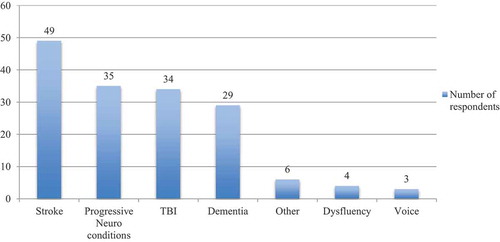

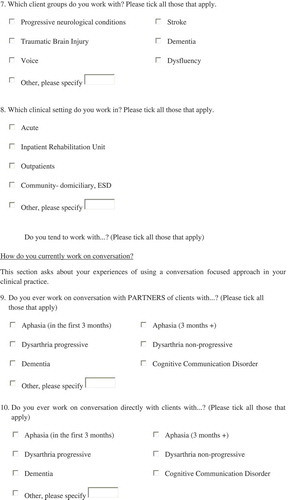

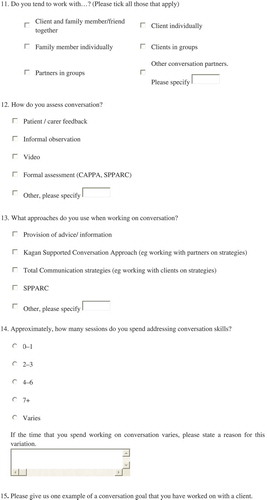

The majority of respondents (76%, n = 38) had no daily target number of clients to see, however one quarter did (24%, n = 12), and saw on average 5.2 clients (range 3–8, median and mode = 5). Ninety-eight per cent of respondents (n = 49) worked with stroke clients, 70% (n = 35) with progressive neurological conditions, 68% (n = 35) with traumatic brain injury, 58% (n = 29) with dementia, and 12% (n = 6) with “other” client groups (other neurological conditions, oncology, respiratory, gastrology, surgical, and general elderly; see ). Inpatient rehabilitation units (46%, n = 23) and community settings (48%, n = 24) were the most common workplace settings, followed by acute (36%, n = 18), outpatients (32%, n = 16), and other (6%, n = 3) which included an acute psychiatric setting and community hospitals.

Conversation therapy delivery

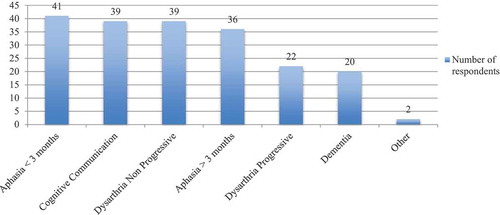

Eighty-two per cent of respondents (n = 41) worked on conversation indirectly through the partners of clients with aphasia in the first 3 months following a stroke, compared with 72% (n = 36) with the same client group from 3 months onwards. Indirect work on conversation was also carried out for non-progressive dysarthria (78%, n = 39), cognitive communication disorder (78%, n = 39), progressive dysarthria (44%, n = 22), dementia (40%, n = 20), and other (including dyspraxia 4%, n = 2) ().

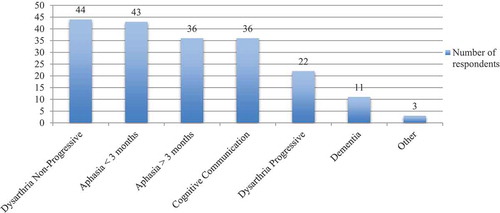

Eighty-eight per cent of respondents (n = 44) indicated they worked on conversation directly with clients with non-progressive dysarthria, and 44% (n = 22) with clients with progressive dysarthria (). It is important to note that more respondents worked with non-progressive clients than with progressive clients (see paragraph earlier). Eighty-six per cent (n = 43) worked on conversation with clients with aphasia in the first 3 months, compared with 72% (n = 36) with same client group from 3 months onwards. Direct work on conversation was also carried out with client groups with cognitive communication disorders (72%, n = 36), dementia (22%, n = 11), and other including dyspraxia and dysfluency (6%, n = 3).

Ninety per cent of respondents (n = 45) worked on conversation with a client and family member together, 82% (n = 41) with a client individually, and 46% (n = 23) with a partner individually. Fifty-eight per cent (n = 29) worked with clients in groups, compared with 12% (n = 12) with partners in groups. Other partners (22%, n = 11) included multidisciplinary team (MDT) members, carers, volunteers, and work colleagues.

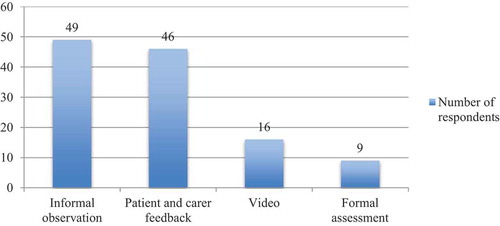

Nearly all respondents (98%, n = 49) reported using informal observation to assess conversation, and 92% (n = 46) used patient and carer feedback on conversation as an assessment method (). Approximately one-third (32%, n = 16) used video as an assessment tool, and only 18% (n = 9) used a formal assessment such as the CAPPA (Whitworth et al., Citation1997) or SPPARC (Lock et al., Citation2001).

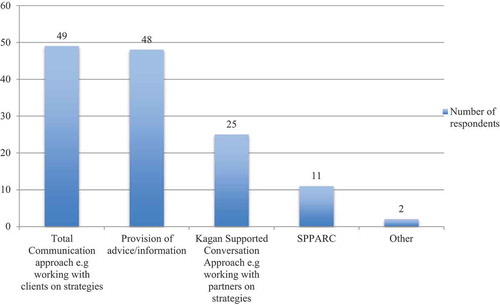

Nearly all respondents (98%, n = 49) reported using TC strategies and 96% (n = 48) provided information and advice (). Less commonly used were published approaches such as SCA™ (Kagan, Citation1998) (50%, n = 25) and SPPARC (Lock et al., Citation2001) (22%, n = 11).

Over half of the respondents (60%, n = 30) reported a variable number of sessions spent addressing conversation (). Analysis of their responses (Q14b) when asked to state a reason revealed three themes: (1) client/CP (factors relating to individual only); (2) client and service (combination of factors pertaining to individual and provision); and (3) setting, the first two of which included sub-themes (see ). The findings indicate that, with respect to theme 1, SLTs were guided predominantly by the client, their partner (sub-theme 1.1), needs (1.2), circumstances (1.3), and the ability to learn (1.4):

This will depend on how able the person is to take on these issues and to acknowledge that the way that conversations are supported and dealt with is at least as important as the semantic content of the conversation. (P35)

Table 2. Number of sessions SLTs spend working on conversation.

Fewer responses contributed to themes 2 and 3 but included reasons such as therapists’ workload, staffing levels, time restrictions, staffing levels, and patient medical status.

,) present content analysis of the 46 conversation goals submitted by survey respondents. Eighty per cent of the goals were categorised into themes 1, 2, and 3. Theme 1 goals reflected working on strategies and encouraging a TC approach. Specific strategy use (sub-theme 1.1) included using cards or a communication book, writing, gesture, and pausing. For some of these goals, the topic of conversation and the setting were also stated:

To use written social phrase prompts to initiate greetings during visiting hours. (P30)

General strategy use (1.2) specified the CP and topic of conversation, and strategies to aid word finding (1.3) included both general and specific strategy use when encountering a word finding difficulty. Theme 2 comprised goals based on a CA approach, referring to (topic) initiation, maintenance, and turns. Topic initiation (2.1) included CPs of variable familiarity, or initiating in a group:

Patient will initiate a conversation or change topic in a small group discussion. (P42)

Theme 3 comprised goals that targeted functional communication. Some were specific about topic and CP, whereas others were more general:

To get my point across more often when discussing controversial subjects with family and in arguments with my husband. (P1)

To be able to order food/drink in a restaurant. (P34)

Such goals reflected holistic working and considered the social impact of communication disability. However, none mentioned the means by which the goal will be achieved.

It is difficult to comment on whether conversation therapy use differed across settings or by SLT experience, as the majority of respondents reported delivering a variable number of sessions, and this issue was not pursued. Interestingly the only respondent who indicated addressing conversation for “0–1 session” was a Band 5 therapist, and the three respondents selecting “7 or more sessions” were Band 7 therapists. This may suggest a link between SLT experience and number of sessions devoted to conversation work, and highlights the need for further investigation.

Summary of survey results

This survey of 50 mostly Band 6 or 7 SLTs in South East England working in stroke, inpatient rehabilitation and the community, revealed a strong trend towards delivering conversation therapy to clients with a range of acquired conditions and their CPs. Most worked on conversation directly and indirectly for aphasia, with a slightly higher percentage working directly in the first 3 months post-stroke. Most commonly, intervention involved a client and family member together, although individual and group work were also popular. Informal approaches to assessment and treatment were used over published resources, and there was substantial variation in therapy delivery, influenced by client and CP need, service, and setting. Conversation goals were diverse, with most focusing on strategy use/TC, CA, and functional communication.

Focus group results

SLTs’ current practice in relation to conversation therapy was further explored through a focus group. The six participants (Bands 6 and 7) worked within stroke and progressive neurology (acute, inpatient rehabilitation, community, and medico/legal). Analysis of their comments on conversation therapy revealed three overarching themes: (1) What is conversation therapy? (2) showing it works, and (3) complexities of delivering it (see , , and ). These themes incorporate several sub-themes, which are also discussed later with reference to their definitions, and illustrative units of data.

What is conversation therapy encompassed SLTs’ definitions, who is involved, and functional gain (). Working on strategies was a significant component of SLT definitions of conversation therapy (sub-theme 1.1):

I am focusing more on the family and carers, what they should do and shouldn’t be doing …. It’s not really therapy, but strategies.(P5)

Whilst working on strategies was perceived to be key, there was no consensus about the most effective way of doing this. Only participant 1 mentioned using video as a reflective tool, which is interesting given that video is often considered a core element of conversation therapy. Who’s involved? (sub-theme 1.2) included references to the client, husband, wife, family, and carers, and revealed consensus. Only participant 5 made reference to prioritising time with a CP rather than with the client. Functional gain (sub-theme 1.3) reflected the viewpoints of three participants who acknowledged a key benefit of conversation therapy to be its functionality:

It’s that functional gain isn’t it? rather than aiming for perfect language, it’s that functionality that is key … you ask a patient what they want to do, “I want to talk” they don’t want to talk to be able to ask for things, they want to be able to have conversations with people, that’s their goal. (P3)

Showing it works captured the need to demonstrate efficacy to others, and included education, measurement, influence of published research, and feeling justified in doing the therapy (). Education (sub-theme 2.1) encompassed educating clients and their families, and colleagues. Participants agreed that modelling the use of conversation strategies encouraged clients and carers to try them out:

Certainly with families they definitely benefit from seeing it because they can nod along and say “well yes I give him lots of time” and then you just watch their interaction and think “oh no”, nothing. (P3)

Half the participants believed it was important to educate colleagues in response to a perceived lack of understanding of the value of these approaches:

It is more of an education … they think “oh they’re just having a chat” and that’s all it is but not actually understanding the finer details about actually what we do and why we do it and how as well. (P2)

The view that SLTs were “just having a chat” was a recurring point of discussion. It was encountered within the MDT by three participants, who reported feeling the need to justify the use of conversation therapy (sub-theme 2.4).

Measurement (sub-theme 2.2) revealed the SLTs need to actively demonstrate its benefit:

being able to quantify and actually having an outcome measure, especially the way things are going in terms of proving to commissioners what we are doing is evidence based practice, it’s actually a way of measuring how effective we have been …. I think actually being able to have numbers and quantify it would be really good. (P2)

Influence of published research (sub-theme 2.3) reflected responses to an article reporting on a treatment study employing paid individuals to communicate with inpatients (Bowen et al., Citation2012) that was published around the time of the focus group:

We’ve (gestures to participant 3) been talking about the ACT NoW paper that’s come out, maybe that will give us more grounding to look at conversation, more on a par with impairment based therapy …. I think what we’re very keen to do is get very defined outcome measures so we can be demonstrating improvement in this different area. (P4)

Whilst participants agreed on the link between an appropriate outcome measure and more routine use of conversation therapy, it was unclear how they felt about the ACT NoW paper. Participant 4 suggested the paper allowed her to focus more on conversation (but in what capacity was not clear), whereas participant 2 felt differently:

The way that it (conversation therapy) is perceived by others and obviously with that ACT NoW research as well, it’s “you just get anyone in to have a chat”. (P2)

Complexities of doing conversation therapy was the broadest overarching theme (), representing much of the data, and encompassing the complex nature and challenges of the approach, both external and internal. Sub-themes with a large amount of cross-coded data signifying possible relationships are presented here. Some of these relationships were raised by participants, others are hypothesised by the authors. The data suggest that the perception of others (sub-theme 3.1) influenced SLTs to take a combined approach to therapy (sub-theme 3.4), as did pressure to carry out impairment therapy (sub-theme 3.5). In addition, setting (sub-theme 3.6) influenced pressure to carry out impairment therapy. The connections and direction of influence are indicated by arrows in .

Conversation therapy tended to be combined with impairment based therapy, in different ways, and for different purposes (e.g., accepting benefits of conversation therapy; fulfilling expectations of colleagues and clients for therapy that comprises worksheets and exercises):

I find that if you combine the impairment type and the functional type and then ultimately work on conversation … it seems to work … then they (client and partner) accept but if you just focus on just the chatting bit I don’t think that would go down very well. (P5)

Participants were broadly in agreement about the ways in which clients and CPs influenced choice of therapy; however there was a greater range of experience regarding the influence of colleagues’ and other professionals’ perceptions:

some people put us on a pedestal and think we’re amazing and other people are not sure what we do apart from having tea and cakes. (P2)

I think we joke in the team about me going to have a cup of tea and a chat … but it’s all tongue in cheek …. I think the team are very aware of what we do as speech therapists. (P6)

There was pressure to carry out impairment-based interventions (sub-theme 3.5), and one participant reported a direct consequence was less conversation therapy. SLTs hypothesised that the setting (sub-theme 3.6) influenced the choice of therapy approaches available to them:

I used to work with (Participant 4) in the inpatient setting and I think coming to the community for the first time, I’m having a real chance to get to grips with a community caseload, I think there’s actually more opportunity for it and actually the approach that you have when you are in hospital is very impairment based. (P2)

Comments reflected feelings about delivering conversation therapy (sub-theme 3.2) some of which could be directly attributed to the influence of the dyad relationship (sub-theme 3.3) or structuring therapy (sub-theme 3.7). Participants reported a sense of awkwardness about dealing with the impact of relationship dynamics on therapy, and the availability of CPs:

Especially if the husband and wife relationship is not a good one that’s a tricky one, I have been in situations where they have not had a good marriage before and when one of them has a stroke and that makes it very, very difficult. (P5)

Participant 4 felt she was “making therapy up” when working on conversation, and another agreed. Participant 3 suggested a structure would overcome this, and made links to justifying conversation therapy (2.4):

To find some way of structuring it like you said so that we can feel confident in delivering that form of therapy and also feel that we are justified in doing it. (P3)

SLT feelings (sub-theme 3.2) revealed recognition of the benefit of conversation therapy, whilst acknowledging internal (unspecified) factors often prevented a focus on this approach:

I’ve not focused on it enough actually …. I wish I had because I do think that it can make a real difference. (P3)

Summary of focus group results

The overarching themes pertain to establishing a definition for conversation therapy, evaluating effectiveness, and managing the complexities of delivery. Definitions highlighted work on strategies, however no consensus was reached. There was a reported need to demonstrate efficacy; with the right measurement tools, participants would feel justified in using this approach. The education of others was also linked to demonstrating efficacy. Most discussion was generated around the complexities of delivering conversation therapy. Whilst the benefits were recognised, the perceptions of others, SLTs’ own feelings, and pressure to carry out impairment therapy, resulted in the majority of participants combining impairment and conversation therapy, feeling they lacked a justification for delivering the latter in isolation.

Discussion

Defining conversation therapy

The SLTs who took part in this study (survey and focus group) interpreted conversation therapy to encompass an eclectic blend of strategy use, TC, topic initiation and maintenance, and functional communication targets. Much of their reported work focused on conversation targeted strategy training. These findings concur with definitions of conversation therapy proposed by Simmons-Mackie et al. (Citation2010), (Citation2016) and Wilkinson and Wielaert (Citation2012). Furthermore, SLTs felt they were “making therapy up”, and that other professionals perceived they were “just having a chat”. This suggests a lack of a professionally held strong definition of conversation therapy, one that is held by SLTs themselves and shared with other professionals to justify and explain treatment. In addition, structuring conversation therapy more (raised by SLTs) would help in achieving a clear definition of conversation therapy, for example, through specifying the active ingredients, the goal or rationale of essential elements, mode of delivery, and so on. This would need to be considered alongside the strong emphasis in practice on personal tailoring of the intervention to clients’ needs and circumstances.

Delivering conversation therapy

The SLTs in this study provided conversation therapy to both clients with acquired or non-progressive conditions, and clients with progressive conditions. The former practice is supported by a growing evidence base in aphasia (Simmons-Mackie et al., Citation2010, Citation2016, Citation2014) and traumatic brain injury (Togher, McDonald, Code, & Grant, Citation2004). However for the latter client group, the evidence is currently limited, for example, to progressive dysarthria (Forsgren, Antonsson, & Saldert, Citation2013). This finding suggests that SLTs recognise the potential of conversation therapy as a broader therapy approach, and research could prioritise a wider evidence base.

The majority of SLTs worked with clients and CPs together. A recent international study of aphasia clinicians and managers revealed consensus that dyadic communication, that is, the ability of both the person with aphasia and CP to communicate with each other, was the most agreed treatment outcome of aphasia rehabilitation (Wallace, Worrall, Rose, & LeDorze, Citation2016b). It is possible that clinicians perceive it to be efficient to work jointly with clients and their CPs. In aphasia, there are a few individual case studies to support this way of working (Beckley et al., Citation2013; Beeke et al., Citation2015), and there is stronger evidence in the form of two systematic reviews (Simmons-Mackie et al., Citation2010, Citation2016; see also Citation2014) and a United Kingdom review (Turner & Whitworth, Citation2006) to support training a CP. This study found that less than half the SLTs worked with CPs individually and even fewer in groups, despite the availability of the SCA™ (Kagan, Citation1998) and SPPARC (Lock et al., Citation2001). These findings mirror those of Rose et al. (Citation2014) where Australian SLTs reported limited training of CPs during aphasia rehabilitation. Only one focus group participant reported using video, considered a core method by proponents of conversation therapy based on CA (Beckley et al., Citation2013; Lock et al., Citation2001), a finding that concurs with Beckley et al. (Citation2016) survey of wider communication strategy training practices, however a third of survey respondents in Beckley et al.’s study reported using video to assess conversation.

This study identifies the desire for an outcome measure to validate conversation therapy, but few respondents reported using published measures such as the observational measures (Kagan et al., Citation2004), and CAPPA (Whitworth et al., Citation1997). Other researchers have also reported a lack of clarity about how to measure conversation, which can lead to limited use of conversation therapy (Collis & Bloch, Citation2012; Simmons-Mackie et al., Citation2005; Verna et al., Citation2009). Given that so many different outcome measures have been used to date to evaluate communication partner training (Simmons-Mackie et al., Citation2010, Citation2016), it is likely that this lack of consensus within research contributes to a lack of outcome measurement in clinical practice. As well as fully defining and specifying the components of conversation therapy, further research needs to identify the barriers and facilitators to measuring outcomes of conversation therapy in practice, and to reach consensus amongst stakeholders on a reliable, feasible, and acceptable outcome measure.

These SLTs used conversation therapy in combination with other approaches, and the amount of time they spent addressing conversation varied. The root of this may be a perceived lack of evidence with which to convince other members of the MDT as to its worth, possibly resulting in SLTs combining approaches as a hedge against criticism, despite the findings of Turner and Whitworth (Citation2006) and (Simmons-Mackie et al., Citation2010, Citation2016). Other studies also found that SLTs use two approaches simultaneously (Collis & Bloch, Citation2012; Sherratt et al., Citation2011; Verna et al., Citation2009) and the Royal College of Speech and Language Therapists (Citation2005) acknowledge delivering approaches concurrently may be required. Nonetheless, the possible implications of these findings should be considered in light of the research around therapy intensity and dose. The Royal College of Physicians Intercollegiate Stroke Working Party (Citation2016) recommends 45 min of treatment every day, whilst Bhogal, Teasell, and Speechley (Citation2003) state intensive speech and language therapy over a short time period can improve outcomes in aphasia. With no consensus around the number of sessions needed to deliver conversation therapy (Simmons-Mackie et al., Citation2010, Citation2016), its concurrent delivery with another therapy may lead to a lower dose of each, diluting the potential effectiveness of both. This in turn may reinforce the view of other professionals, and even of SLTs themselves, that conversation therapy is not effective. In order to implement treatments with the intensity and dose originally intended, more resource, therapy time, and different treatment schedules (e.g., parallel or sequential treatments) are needed in research and practice.

A popular goal for conversation therapy was the increased use of strategies by the client. Sherratt et al. (Citation2011) also found that SLTs set strategy-related goals, which often included personalised strategies for a person with aphasia, and Beckley et al. (Citation2016) reported twice as much direct strategy work with clients than with their CPs. This is an interesting finding, given that the conversation therapy evidence base currently supports strategy training for CPs, but there is as yet little evidence for training a client. However common strategy training for clients may be, it is not exempt from the challenge of generalising success in the clinic to everyday life (Beckley et al., Citation2013). Few goals identified in this study targeted family members and their interactions with the person with aphasia, a similar finding to Sherratt et al. (Citation2011).

According to these SLTs, delivering conversation therapy is complex; they reported that they wanted to deliver more of it but met with a range of challenges, including the perception of others, their own feelings and managing the dyad relationship. Rose et al. (Citation2014) found many Australian SLTs in their sample wanted to deliver more frequent and comprehensive CP training, but identified that lack of time, resources, and availability of family members were barriers to this.

The setting was also a challenge and provoked conflicting views. According to the survey results, there was a slight trend towards working with clients/CPs in the first 3 months following a stroke, and it was noted in the Verna et al. (Citation2009) that CP training was delivered more in inpatient and outpatient rehabilitation hospital settings, than in community-based settings. Participants from the study by Rose et al. (Citation2014) thought CP training was marginally more appropriate for an inpatient rehabilitation setting (82%) than for a community setting (72%). However, the views of the focus group conducted for our study were that a community setting provided more opportunity to work on conversation, whereas inpatient work tended to be more impairment focused, reflecting the findings of Collis and Bloch (Citation2012) for dysarthria interventions. These conflicting findings suggest SLTs have identified the benefit of working on conversation from acute through to community settings, but as yet the evidence base does not reflect such trends. Different conversation outcomes may well be appropriate at different stages of the rehabilitation process, yet it appears that the literature is less clear about which setting achieves the best outcomes for a particular approach.

Application of research within SLT practice

SLTs typically seek information from different sources to support clinical practice, one of which is the literature. The variety of methods of delivering conversation therapy reported in this study suggest that there is no consensus about what is most effective, and this is one of the major challenges of this approach. Evidence exists to support working with a CP, and there are published conversation measures, however this study reveals the available evidence is not always used to guide clinical practice.

Why might this be the case? The selection of an evidence-based approach that achieves positive outcomes might be expected to be routine, given professional requirements to act as an evidence-based practitioner, heavy demands on time, growing caseloads, and the need to demonstrate the effectiveness of therapy. One possible explanation could be that SLTs lack the time to access research (O’Connor & Pettigrew, Citation2009). In addition, according to McCurtin and Roddam (Citation2012), SLTs prefer to use sources other than research findings to inform their clinical decisions. Another explanation centres on the difficulty of transferring research into clinical practice, identified as a major challenge in aphasia rehabilitation for Australian clinicians (Rose et al., Citation2014). For example, reading a research report on a particular therapy approach does not necessarily enable an SLT to start using it immediately. Few research articles actually detail the practical steps involved in delivering a particular approach (Simmons-Mackie et al., Citation2016), however this information is critical to consolidate new learning and equip an SLT with the necessary therapy skills. A third explanation could be conflicting information in the literature. This study highlights the lack of a clear sense of optimal timing, duration, or setting for conversation therapy. If an SLT consulted studies of CP training, for example, they would find great variety in how many sessions were delivered. Critical decisions concerning timing and dose are often left to an individual SLT to decide. It is likely that elements of each of these issues are at play and that challenges in implementing evidence-based practice are not specific to conversation therapy alone; it is part of a wider reality facing all allied health professionals. Core to this issue is the field of implementation science, wherein the implementation of interventions and adherence to practice guidelines is a heavily studied field in its own right. Implementation is mediated by a range of factors (enablers and barriers); assessing these factors’ influence and developing a subsequent strategy (Flottorp et al., Citation2013), is what is now required to progress conversation therapy in SLT practice. Implementation cannot occur though unless earlier precursor stages have been completed. In recent times there have been substantial advances in knowledge synthesis (Graham et al., Citation2006) of conversation therapy research (Simmons-Mackie et al., Citation2010, Citation2016, Citation2014), however knowledge tools and products (Graham et al., Citation2006) are still lacking, hence the BCA wider project that contextualises this study. It is clear that ongoing communication is needed for effective knowledge translation and implementation, and as such, conversation therapy communities of practice are a possible mechanism for moving the field forward (Bezyak, Ditchman, Burke, & Chan, Citation2013).

Finally, having acknowledged the importance of SLTs adhering to research evidence, it is also important to explore how clinical practice could drive the research agenda. The largest body of evidence to support the use of conversation therapy currently focuses on aphasia but, as this study demonstrates, SLTs are using it for a range of communication disorders and further research is needed across client groups and settings to validate its broader use. Such knowledge exchange could occur within organised communities of practice within the profession involving clinicians and researchers of different levels (Bezyak et al., Citation2013).

Limitations of the current study and future research

The study targeted SLTs working in the south east of England, with a relatively small sample of 50 completing the survey and six taking part in the focus group, thus conclusions drawn may not be representative of United Kingdom SLTs as a whole. Only one focus group was held; in order to achieve data saturation, a series of focus groups with different participants would be warranted. The participants who volunteered for the focus group were a self-selecting group who knew that the topic of discussion would be around conversation therapy, and may have been biased in terms of their interest and experience in this area. Finally, during the focus group it was not made explicit whether the participants were to discuss conversation therapy in relation to people with aphasia, or with a range of client groups. Although one participant does mention working with people with aphasia, the others talk generally about their clients without specifying disorder. Whilst it is not entirely certain that participants reflected only on clients with aphasia, this focus might be assumed because participants knew they were participating in the BCA project.

Future research investigating clinicians’ practices would employ a larger sample incorporating a broader geographical spread within the United Kingdom and include SLTs who do not currently deliver conversation therapy. Involving participants in data analysis would clarify and strengthen the relationships amongst sub-themes that have been proposed here. Issues worthy of further exploration include whether the banding and experience of an SLT influences the use of conversation therapy and how clinical setting may impact on the approach selected. Further research to identify and address the challenges of sharing the evidence base amongst the SLT community and incorporating research findings into clinical practice is also warranted.

Conclusion

In conclusion, conversation therapy is acknowledged by these SLTs to be beneficial, and is delivered to clients with a range of non-progressive and progressive conditions, and their family members, using a range of goals that draw on strategies, TC and CA. The SLTs in this study primarily used informal assessments and often carried out a combination of conversation and impairment therapy. Treatment duration varied and was influenced by a range of factors. There was a desire to justify its effectiveness, and a wish for appropriate outcome measures. Existing evidence and published assessment and treatment approaches to address these concerns are not being consistently applied in practice. The challenge remains as to how to enable the translation of the evidence base in conversation therapy into daily clinical practice.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Economic and Social Research Council under Grant RES-189-25-0292 Better Conversations with Aphasia (the second author was principal investigator). It constituted the first author’s conversion module in MSc Speech and Language Therapy at City, University of London, supervised by the third and second authors. We extend our thanks to survey respondents and focus group participants for their time and considered reflections.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Beckley, F., Best, W., & Beeke, S. (2016). Delivering communication strategy training for people with aphasia: What is current clinical practice? International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders. E-pub ahead of print. doi:10.1111/1460-6984.12265

- Beckley, F., Best, W., Johnson, F., Edwards, S., Maxim, J., & Beeke, S. (2013). Conversation therapy for agrammatism: Exploring the therapeutic process of engagement and learning by a person with aphasia. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 48, 220–239. doi:10.1111/jlcd.2013.48.issue-2

- Beeke, S., Beckley, F., Johnson, F., Heilemann, C., Edwards, S., Maxim, J., & Best, W. (2015). Conversation focused aphasia therapy: Investigating the adoption of strategies by people with agrammatism. Aphasiology, 29, 355–377. doi:10.1080/02687038.2014.881459

- Beeke, S., Sirman, N., Beckley, F., Maxim, J., Edwards, S., Swinburn, K., & Best, W. (2013). Better conversations with aphasia: An e-learning resource. Available from: http://extend.ucl.ac.uk/

- Bezyak, J. L., Ditchman, N., Burke, J., & Chan, F. (2013). Communities of practice: A knowledge translation tool for rehabilitation professionals. Rehabilitation Research, Policy, and Education, 27, 89–103. doi:10.1891/2168-6653.27.2.89

- Bhogal, S. K., Teasell, R., & Speechley, M. (2003). Intensity of aphasia therapy, impact on recovery. Stroke; a Journal of Cerebral Circulation, 34, 987–993. doi:10.1161/01.STR.0000062343.64383.D0

- Bowen, A., Hesketh, A., Patchick, E., Young, A., Davies, L., Vail, A., … Tyrrell, P. (2012). Effectiveness of enhanced communication therapy in the first four months after stroke for aphasia and dysarthria : A randomised controlled trial. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), 345, e4407. doi:10.1136/bmj.e4407

- Boynton, P. M. (2004). Administering, analysing, and reporting your questionnaire. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), 328, 1372–1375. doi:10.1136/bmj.328.7452.1372

- Collis, J., & Bloch, S. (2012). Survey of UK speech and language therapists’ assessment and treatment practices for people with progressive dysarthria. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 47, 725–737. doi:10.1111/jlcd.2012.47.issue-6

- Elman, R. J., & Bernstein-Ellis, E. (1999). The efficacy of group communication treatment in adults with chronic aphasia. Journal of Speech, Language and Hearing Research, 42, 411–420. doi:10.1044/jslhr.4202.411

- Flottorp, S. A., Oxman, A. D., Krause, J., Musila, N. R., Wensing, M., Godycki-Cwirko, M., … Eccles, M. P. (2013). A checklist for identifying determinants of practice: A systematic review and synthesis of frameworks and taxonomies of factors that prevent or enable improvements in healthcare professional practice. Implementation Science, 8, 35. doi:10.1186/1748-5908-8-35

- Forsgren, E., Antonsson, M., & Saldert, C. (2013). Training conversation partners of persons with communication disorders related to Parkinson’s disease: A protocol and a pilot study. Logopedics, Phoniatrics, Vocology, 38, 82–90. doi:10.3109/14015439.2012.731081

- Graham, I. A., Logan, J., Harrison, M. B., Strauss, S. E., Tetroe, J., Caswell, W., & Robinson, N. (2006). Lost in knowledge translation: Time for a map? Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions, 26, 13–24. doi:10.1002/chp.47

- Hopper, T., Holland, A., & Rewega, M. (2002). Conversational coaching: Treatment outcomes and future directions. Aphasiology, 16, 745–761. doi:10.1080/02687030244000059

- Kagan, A. (1998). Supported conversation for adults with aphasia: Methods and resources for training conversation partners. Aphasiology, 12, 816–830. doi:10.1080/02687039808249575

- Kagan, A., Winckel, J., Black, S., Duchan, J., Simmons-Mackie, N., & Square, P. (2004). A set of observational measures for rating support and participation in conversation between adults with aphasia and their conversation partners. Topics in Stroke Rehabilitation, 11, 67–83. doi:10.1310/CL3V-A94A-DE5C-CVBE

- Kitzinger, J. (1995). Qualitative research: Introducing focus groups. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), 311, 299–302. doi:10.1136/bmj.311.7000.299

- Lock, S., Wilkinson, R., & Bryan, K. (2001). Supporting partners of people with aphasia in relationships and conversation: A resource pack. Bicester: Speechmark.

- McCurtin, A., & Roddam, H. (2012). Evidence-based practice: SLTs under siege or opportunity for growth? The use and nature of research evidence in the profession. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 47, 11–26. doi:10.1111/j.1460-6984.2011.00074.x

- McVicker, S., Parr, S., Pound, C., & Duchan, J. (2009). The communication partner scheme: A project to develop long-term, low-cost access to conversation for people living with aphasia. Aphasiology, 23, 52–71. doi:10.1080/02687030701688783

- O’Connor, S., & Pettigrew, C. (2009). The barriers perceived to prevent the successful implementation of evidence-based practice by speech and language therapists. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 44, 1018–1035.

- Parsons, M., & Greenwood, J. (2000). A guide to the use of focus groups in health care research: Part 1. Contemporary Nurse, 9, 169–180. doi:10.5172/conu.2000.9.2.169

- Rose, M., Ferguson, A., Power, E., Togher, L., & Worrall, L. (2014). Aphasia rehabilitation in Australia: Current practices, challenges and future directions. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 16, 169–180. doi:10.3109/17549507.2013.794474

- Royal College of Physicians Intercollegiate Stroke Working Party. (2016). National clinical guideline for stroke. (5th ed.), London: Royal College of Physicians. Retrieved from https://www.strokeaudit.org/Guideline/Full-Guideline.aspx

- Royal College of Speech and Language Therapists. (2005). Clinical guidelines. Bicester: Speechmark.

- Sherratt, S., Worrall, L., Pearson, C., Howe, T., Hersh, D., & Davidson, B. (2011). “Well it has to be language-related”: Speech-language pathologists’ goals for people with aphasia and their families. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 13, 317–328. doi:10.3109/17549507.2011.584632

- Simmons-Mackie, N. (2001). Social approaches to aphasia intervention. In R. Chapey (Ed.), Language intervention strategies in aphasia and related neurogenic communication disorders (pp. 246–268). Baltimore: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

- Simmons-Mackie, N., & Kagan, A. (2007). Application of the ICF in aphasia. Seminars in Speech and Language, 28, 244–253. doi:10.1055/s-2007-986521

- Simmons-Mackie, N., Raymer, A., Armstrong, E., Holland, A., & Cherney, L. R. (2010). Communication partner training in aphasia: A systematic review. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 91, 1814–1837. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2010.08.026

- Simmons-Mackie, N., Raymer, A., & Cherney, L. R. (2016). Communication partner training in aphasia: An updated systematic review. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 97, 2202-2221.e8. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2016.03.023

- Simmons-Mackie, N., Savage, M. C., & Worrall, L. (2014). Conversation therapy for aphasia: A qualitative review of the literature. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 49, 511–526. doi:10.1111/jlcd.2014.49.issue-5

- Simmons-Mackie, N., Threats, T. T., & Kagan, A. (2005). Outcome assessment in aphasia: A survey. Journal of Communication Disorders, 38, 1–27. doi:10.1016/j.jcomdis.2004.03.007

- Simmons-Mackie, N., Worrall, L., & Savage, M. (2013). Conversation therapy for aphasia: A survey. Poster presented at the American Speech Language and Hearing Association Conference Annual Convention, 13-16 November, Chicago, USA. Retrieved from http://aphasiology.pitt.edu/archive/00002454/

- Togher, L., McDonald, S., Code, C., & Grant, S. (2004). Training communication partners of people with traumatic brain injury: A randomised controlled trial. Aphasiology, 18, 313–335. doi:10.1080/02687030344000535

- Turner, S., & Whitworth, A. (2006). Conversational partner training programmes in aphasia: A review of key themes and participants’ roles. Aphasiology, 20, 483–510. doi:10.1080/02687030600589991

- Verna, A., Davidson, B., & Rose, T. (2009). Speech-language pathology services for people with aphasia: A survey of current practice in Australia. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 11, 191–205. doi:10.1080/17549500902726059

- Wallace, S., Worrall, L., Rose, T., Le Dorze, G., Cruice, M., Isaksen, J., … Gauvreau, C. (2016a). Which outcomes are most important to people with aphasia and their families? An international nominal group technique study framed within the ICF. Disability and Rehabilitation, June 27, 1–16. Epub ahead of print. doi:10.1080/09638288.2016.1194899

- Wallace, S., Worrall, L., Rose, T., & LeDorze, G. (2016b). Which treatment outcomes are most important to aphasia clinicians and managers? An international e-Delphi consensus study. Aphasiology, 1–31. Epub ahead of print. doi:10.1080/02687038.2016.1186265

- Whitworth, A., Perkins, L., & Lesser, R. (1997). Conversation Analysis Profile for People with Aphasia. London: Whurr.

- Wilkinson, R. (2014). Intervening with conversation analysis in speech and language therapy: Improving aphasic conversation. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 47, 219–238. doi:10.1080/08351813.2014.925659

- Wilkinson, R., Lock, S., Bryan, K., & Sage, K. (2011). Interaction-focused intervention for acquired language disorders: Facilitating mutual adaptation in couples where one partner has aphasia. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 13, 74–87. doi:10.3109/17549507.2011.551140

- Wilkinson, R., & Wielaert, S. (2012). Rehabilitation targeted at everyday communication: Can we change the talk of people with aphasia and their significant others within conversation? Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 93, S70–76. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2011.07.206