ABSTRACT

Background

Reading is an important everyday activity. Extensive individual variability exists in both typical readers and readers with aphasia in their reading ability, preferences, and practice. Although reading comprehension difficulties in people with aphasia are typically assessed at single word, sentence, and text level, there is limited information about how performance at these levels corresponds to their enjoyment and practice of reading.

Aims

This study aimed to improve our understanding of reading in people with aphasia by examining: 1) the relationship between performance on assessments of word, sentence, and paragraph comprehension; 2) the relationship between reported reading difficulty, feelings about reading, and reading activity; and 3) the relationship between reading comprehension scores and personal perception of reading.

Methods & Procedures

Participants included 74 adults with a single symptomatic stroke resulting in aphasia; they did not have to report or present with reading difficulties. Participants completed the Comprehensive Assessment of Reading in Aphasia (CARA). Statistical analysis used Spearman correlations to investigate the relationship between measures. Illustrative case studies provided evidence of individual variability.

Outcomes & Results

Significant positive correlations were found between comprehension accuracy in single word and sentence, single word and paragraph, and sentence and paragraph assessments. There were also significant positive correlations among reported reading difficulty, feelings about reading, and reading activity. There were no significant correlations between reading comprehension scores and personal perception of reading.

Conclusions

There is no straightforward relationship between reading comprehension difficulties and individual perception of reading. This emphasises the importance of considering both when discussing and agreeing goals, selecting a treatment approach, and evaluating the outcome of intervention.

Introduction

Reading in People with Aphasia

Reading difficulties are a common feature of aphasia, including oral reading and reading comprehension problems and reduced reading speed (Knollman-Porter et al., Citation2015). Reading is essential for a wide range of social, leisure, and work activities (Knollman-Porter et al., Citation2015; Parr, Citation1995), with reading difficulties restricting participation and potentially impacting overall quality of life (Parr, Citation2007). In semi-structured interviews about reading, individuals report feelings of loss, frustration, disappointment, and annoyance (Kjellén et al., Citation2017; Webster, Samouelle et al., Citation2018). However, individuals are often motivated to read and want to improve their skills (Kjellén et al., Citation2017; Webster, Samouelle et al., Citation2018), recognising the importance of reading in everyday life (Kjellén et al., Citation2017).

There are individuals who perform at ceiling on the reading assessments traditionally used by people with aphasia, but who find everyday reading a bitterly frustrating and disappointing experience (e.g., DV, Meteyard et al., Citation2010). The contrast is with people who, despite extremely poor processing of written materials on conventional clinical tests, can lead a rich, satisfying, and engaged literary life. Perhaps, the best example of this more surprising picture is John Hale, whose aphasia is eloquently described by his wife Sheila (Hale, Citation2003). John was an acclaimed Renaissance historian, writer, and lecturer who had a severe stroke resulting in aphasia. He could no longer speak, and his reading was significantly affected. He failed to understand single words in simple written word to object matching tasks (p46) and short “childlike” stories (p84) – tasks routinely used in the clinical setting. However, she reports he seemed to understand his academic journals. She writes “I can tell this because he marks them in what seem like appropriate places and answers questions about them by pointing to relevant passages” (p47). He also read the newspaper and was able to do linguistic tasks that were perhaps more relevant or appropriate to his pre-morbid level of education and interests, e.g., a game from Reader’s Digest matching rare words to their definitions. Later, in his recovery, he also maintained his love of books, joining a library, engaging with a local bookseller to purchase books, and reading for pleasure. This paper addresses the relationships between performance on different measures of reading and report of reading. Importantly, it considers whether the enjoyment and satisfaction that people with aphasia experience in reading is largely independent of their scores in tests of written word, sentence, and discourse comprehension as these examples might suggest, or whether – as one would predict – better reading comprehension on testing makes satisfying engagement with reading more likely.

Parr (Citation1992) argued that functional literacy activities in typical readers cannot be predicted or typified as they are embedded in domestic, social, and cultural patterns of behaviour. Reading preferences and practices vary based on social roles (e.g., family, employment, and interests) and individuals may do reading and writing activities in co-operation with others (Parr, Citation1992). Semi-structured interviews with people with aphasia focusing on pre- and post-morbid reading (Kjellén et al., Citation2017; Knollman-Porter et al., Citation2015; Parr, Citation1995; Webster, Samouelle et al., Citation2018) reveal the same variability found in typical readers. Individuals with aphasia have unique motivations for reading (Kjellén et al., Citation2017; Webster, Samouelle et al., Citation2018) and read a unique range of reading materials (Kjellén et al., Citation2017; Knollman-Porter et al., Citation2015). Individuals with aphasia also seek support from, or delegate tasks (e.g., reading formal letters) to, others, possibly more often than before their stroke (Knollman-Porter et al., Citation2015; Webster, Samouelle et al., Citation2018).

Webster et al. (Citation2021) report the design of a questionnaire developed to consider individual perception of reading ability and activities and feelings about reading. The questionnaire allowed views to be obtained from people with aphasia with both comprehension and spoken production difficulties across the severity range and captured information in a clinically feasible and time-efficient manner. The questionnaire had good face and construct validity, good internal consistency, and test–retest reliability (Webster et al., Citation2021). As predicted, the questionnaire revealed individual variability in perception of and feelings about reading, and in reported reading difficulties at single word, sentence, paragraph level, and when reading books, with increased perceived difficulty with increasing length of material. The extent to which perception of reading was linked to the severity of reading difficulties and how it related to performance in reading comprehension assessments was not, however, considered.

Reading at Word, Sentence & Paragraph Level

Everyday reading can involve single words or sentences (e.g., on signs, menus, labels), but it is more likely to involve paragraphs and extended text (e.g., in emails, news articles, websites, books). Reading comprehension in people with aphasia has been assessed at word, sentence, and paragraph level, but there is currently limited insight into the associations between different levels and how lexical and syntactic difficulties influence everyday reading. Text or discourse comprehension (the understanding of multiple sentences) involves lexical recognition and comprehension and the processing of the syntactic structure of sentences. The overall meaning of discourse is not, however, a simple accumulation of word and sentence meaning (Brookshire & Nicholas, Citation1993). We need to extract the propositional content, understand the relationship between the propositions, and maintain the coherence of what we have heard or read (Kintsch, Citation1988). As such, there is an increased contribution of inferential processing and world knowledge (Kintsch, Citation1988) and problem solving and deduction (Stachowiak et al., Citation1977). Discourse comprehension also involves a complex interaction between linguistic and other cognitive processes including working memory, attention, and executive function (Chesneau & Ska, Citation2015; Watter et al., Citation2017).

There may then be differences in the comprehension difficulties seen at different linguistic levels, with performance on assessments of single word and sentence comprehension not necessarily predicting understanding of multi-sentence messages (Brookshire & Nicholas, Citation1984). Some individuals with aphasia show no difficulties in basic level linguistic assessments but report difficulties in understanding text (e.g., participants described in Chesneau & Ska, Citation2015). For these individuals, difficulties at text level may reflect the increased cognitive demands of text processing, with impairments in working memory, attention allocation, and executive function influencing comprehension (Chesneau & Ska, Citation2015). For other individuals, the context and potential to rely on background knowledge and redundancy of information present at text level may facilitate comprehension (Waller & Darley, Citation1978; Webster, Morris et al., Citation2018).

Previous studies have considered the relationship between assessments of single word and/or sentence comprehension and discourse comprehension in spoken or written comprehension. Studies have used different tasks and have typically involved small numbers of participants. In three studies of spoken comprehension (Brookshire & Nicholas, Citation1984; Waller & Darley, Citation1978; Wegner et al., Citation1984), no clear relationship was identified between sentence and discourse comprehension; there was no significant correlation between performance on an assessment of syntactic comprehension (a shortened version on the Token Test, Spreen & Benton, Citation1969) and correct responses on different assessments of paragraph comprehension. Poor performance and high error rates on the Token Test did not prevent people from understanding both the main ideas and specific details within paragraphs. In addition, Brookshire and Nicholas (Citation1984) found no significant correlation between the auditory comprehension sub-tests of the Boston Diagnostic Aphasia Examination (BDAE, Goodglass & Kaplan, Citation1972) and correct responses in paragraph comprehension; the BDAE sub-tests involve the comprehension of words and sentences. Participant numbers in these studies ranged from 10 (Wegner et al., Citation1984) to 20 (Waller & Darley, Citation1978) people with aphasia. The authors of these studies argue that context and inference play an important role in the comprehension of spoken discourse; context and real-world knowledge may allow overall meaning to be extracted without requiring accurate interpretation of syntactic structure.

Caplan and Evans (Citation1990) investigated the relationship between spoken comprehension of reversible sentences of varying syntactic complexity and comprehension of syntactically simple or complex stories. The authors argue that the stories resembled natural discourse as the sentences were non-reversible and comprehension could be aided by context and real-world knowledge. Sixteen people with aphasia were assessed alongside control participants. There was a low (rs = 0.52) but significant positive correlation between performance on the syntactic and story comprehension tasks; sentence comprehension difficulties were generally associated with difficulties in discourse comprehension, although this did not relate to a person’s ability to understand syntactically complex sentences. Within the study, however, there were several individuals where dissociations between sentence and discourse comprehension were present, suggesting some selective impairment of distinct processes and a complex relationship between syntactic and discourse comprehension.

Focusing on written comprehension, Webb and Love (Citation1983) assessed single-word comprehension (picture-to-word matching), sentence comprehension (error detection) and paragraph comprehension in 35 participants. Participants also completed assessments of oral reading and letter and word recognition. Sentence comprehension was the most difficult task across participants. A factor analysis revealed two factors, general reading ability, and silent reading skill, suggesting a relationship between the comprehension measures. There was also a strong relationship between reading ability and overall severity of language disorder, as measured by the Porch Index of Communicative Ability (PICA, Porch, Citation1967). Smith and Ryan (Citation2020) also considered the relationship between reading tasks, with a primary focus on oral reading. The study identified a correlation between the accuracy of oral reading of words and non-words and oral reading of text. There was no correlation between oral reading of words and oral or silent reading comprehension.

Meteyard et al. (Citation2015) carried out a detailed study of four participants, probing their performance across a range of written tasks involving word, sentence and discourse comprehension, measures of working memory, and metacognitive abilities. Based on the results, the authors suggest some dissociations in performance across different linguistic levels. Participant L showed a residual impairment in written synonym judgment and detecting errors in discourse, despite retained sentence comprehension. Meteyard et al. (Citation2015) argue that this emphasises “the relative importance of word meaning over syntactic parsing for building a representation of the text” (p19). The other three participants (W, S, and P) performed within normal limits on assessments of word comprehension. Participant W also performed within the normal range on written sentence comprehension but found it difficult to understand inferences at text level. Participants S and P had difficulties with sentence comprehension but were able to read at text level, although at a reduced speed. It is suggested that the redundancy within discourse compensated for the sentence-level difficulties. The study, whilst interesting, is difficult to extrapolate from given the small number of participants, the large number of different assessments, the different types of text reading assessed, and the variable performance across participants.

There has, therefore, been some consideration of the relationship between reading comprehension at word, sentence, and paragraph level. However, differences in methodology and small participant groups do not allow for conclusive findings and point to the benefits of a larger scale study to address these important questions. What studies have not really considered is how people with aphasia view their reading abilities and activity in relation to their assessed reading performance.

Aims of the Study

This study focused on the relationship between performance on assessments of reading comprehension and personal perception of reading in people with aphasia. It drew on data collected during a large study of reading in people with aphasia (described in Morris et al., Citation2015) which resulted in the design of the Comprehensive Assessment of Reading in Aphasia (CARA, Morris et al., Citationin preparation). CARA assesses reading comprehension of words, sentences and paragraphs, and probes experiences and feelings about reading and reading activities via a questionnaire. We investigated the following research questions:

What is the relationship between performance on assessments of reading comprehension at single word, sentence, and paragraph level?

What is the relationship between personal perception of reading difficulty, thoughts, and feelings associated with reading, and reported reading activity?

What is the relationship between performance on assessments of reading comprehension and personal perception of reading?

The questions were investigated by looking at the relationship across a large group of people with aphasia and then by exploring the performance of three individuals.

Method

Participants

Seventy-four participants with aphasia were included in this study. Inclusion criteria were a single symptomatic stroke resulting in aphasia, English as the first language, no history of pre-morbid literacy difficulties, no significant visual impairment, and no significant cognitive impairment (e.g., dementia). There was a broad sampling of people with aphasia; individuals did not have to report or present with reading difficulties. There were 42 men and 32 women, with a mean age of 65.3 years (median 66 years, range 33–87). They had a mean of 11.8 years of education, with 17 participants educated to degree level. Time post-stroke varied from 2 months to 21 years (median 1.5 years, mean 4.1 years).

Assessment Materials

Participants’ reading was assessed using the following subtests from the CARA (Morris et al., Citationin preparation). All participants completed the comprehension assessments in full.

Assessment of Single Word Comprehension: Single-word comprehension was assessed using a semantic association task, involving written word matching. The stimulus word was presented with a choice of three written words below (target and two distracters), with participants identifying the word that was most closely related to the stimulus. The assessment consisted of 40 items, with 20 items where both distracters were unrelated to the target (e.g., street matched with road, moon, or fork) and 20 items with one semantically related and one unrelated distracter (e.g., forest matched with wood, hill, or doll).

Assessment of Sentence Comprehension: Sentence comprehension was assessed using a written sentence to picture matching task. Participants were presented with a written sentence and four, black and white pictures. Distracter items were systematically varied so that readers had to understand specific lexical items (nouns, verbs, adjectives, and pronouns) and/or understand specific syntactic structures. Sentences varied in length (from 3 to 11 words), syntactic complexity, and reversibility. The assessment consisted of two parts. In Part 1 (34 items), sentences were non-reversible with lexical distracters (e.g., the children are painting, with pictures representing: the children are painting, the children are drawing, the girl is painting, and the girl is drawing). In Part 2 (23 items), sentences were reversible with a mixture of lexical and grammatical distracters to enable identification of syntactic difficulties (e.g., the nurses are weighing the soldiers, with pictures representing: the nurses are weighing the soldiers, the soldiers are weighing the nurses, the nurses are measuring the soldiers and the soldiers are measuring the nurses). Within part 2, sentence types included actives, passives, subject relatives, and object relatives.

Assessment of Paragraph Comprehension: Understanding at paragraph level was assessed by asking participants to read 15 paragraphs of varied length (<40 words to >200 words) and then answer multiple choice, sentence completion questions. Questions assessed understanding of different types of information: main ideas stated, details stated, main ideas inferred and details inferred. At the end of the assessment, there were a set of questions designed to assess understanding of ideas built across the paragraphs; these were defined as questions about gist. There was a total of 65 questions. More information about the design and format of this assessment can be found in Webster, Morris et al. (Citation2018).

Questionnaire: Participants completed the CARA questionnaire, an aphasia friendly and therapist-supported questionnaire (see, Webster et al., Citation2021). The questionnaire consisted of three sections covering current reading ability and difficulties (section A), feelings about reading (section B), and reading activities (section C). In Section A, the person with aphasia was asked to rate “at the moment, how difficult do you find … … reading and understanding single words, short sentences, paragraphs, a book, reading text out loud, concentrating on reading and remembering what you have read?” A 5-point rating scale was presented which ranged from impossible to no problem, with visual support at the extremes and participants were asked to indicate their response on the scale and could select mid points. Responses were given corresponding numbers from impossible (1) to no problem (5), so higher scores were consistent with less reading difficulty. In section B, the person was asked to rate “at the moment, do you find reading …. enjoyable, easy?” “do you feel … confident, happy to try, motivated?,” “is reading important to you?” and “are you happy with the speed of your reading?.” A 5-point rating scale was presented with no and yes at the extremes. Participants were asked to indicate their response on the scale and could select mid points. Responses were given corresponding numbers, and higher scores were consistent with less concerns about reading. In section C, people were asked to sort cards representing different reading activities/reading materials, e.g., instructions, formal letters, newspaper headlines, and place them on a scale with four points: “impossible/avoid,” “trying to read but difficult,” “trying to read and OK” and “no problem.” Responses were given corresponding numbers, impossible/avoid (1), trying but difficult (2), trying and OK (3),and no problem (4), so higher scores were consistent with a greater range of reading activity and less overall difficulty. Participants could also indicate that the activity was “not applicable”.

Analysis

We calculated the overall proportion correct for the single word, sentence, and paragraph comprehension assessments. For the questionnaire, we scored each section separately and then combined them to determine an overall score. As the data were not normally distributed, non-parametric Spearman correlations were calculated between proportion correct on each comprehension assessment and between the sections of the questionnaire. Correlations were then calculated between proportion correct on each comprehension assessment and the total score on the questionnaire. Using Bonferroni correction across the 10 calculations, correlations were significant if p < .005.

Results

Results of the analyses across the group are presented followed by an exploration of performance for three individuals with aphasia

Correlational analyses

The correlations reported in explore the relationships between single word, sentence, and paragraph comprehension. There are substantial, and essentially equal, positive correlations between single word and sentence, single word and paragraph, and sentence and paragraph comprehension scores showing strong relations among comprehension abilities for differing lengths and complexities of materials.

Table 1. Results of Spearman correlations between single-word comprehension, sentence comprehension, and paragraph comprehension.

reports the correlations between each of the sections of the questionnaire. Significant positive correlations were found among reported reading difficulty, feelings about reading, and reported reading activity.

Table 2. Results of Spearman correlations between sections of the questionnaire.

In , we report on the relationship between the severity of the reading difficulty and personal perception of reading specifically, the correlations between the comprehension assessments, total reading score, and the questionnaire. There were no significant correlations between the comprehension assessments and total score on the questionnaire; they did not meet the Bonferroni-corrected criterion. Correlations between the individual linguistic assessments and each section of the questionnaire were not carried out as sections A and C focused on skills and activities across words, sentences, and paragraphs.

Table 3. Results of Spearman correlations between single-word comprehension, sentence comprehension, and paragraph comprehension, and total score on the questionnaire.

Individual variability was present in performance on the comprehension assessments and the questionnaire ratings; this can be seen in . With each assessment, there are individuals who have a high level of accuracy on the reading comprehension assessment but who rate their reading negatively (low score on the questionnaire) and there are individuals who have significant comprehension difficulties but who rate themselves highly on the questionnaire.

Figure 1. Relationship between accuracy (proportion correct) on CARA single word comprehension assessment and total score on the questionnaire.

Illustrative Case Studies

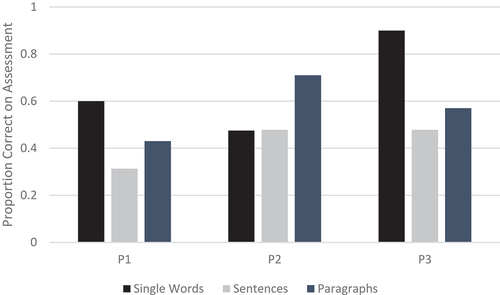

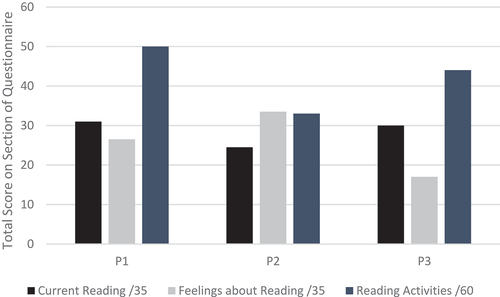

The analysis described above is at group level. Given the inherent variability in reading, it was of interest to consider exemplars of different profiles; three participants were selected who showed differential performance across the reading comprehension assessments and the questionnaire. P1 was a 73-year-old woman who was 18 months post-stroke. She had 10 years of education and had worked in an office prior to retirement. P2 was a 62-year-old man who was 6 months post-onset. He had 11 years of education and owned a bar. P3 was a 67-year-old man who was 4-month post-stroke at the time of the study. He had 14 years of education and had been a captain in the merchant navy. The results for the three participants on the assessments of reading comprehension and on the questionnaire can be seen in .

Figure 4. Comparison of the three individuals with aphasia on the CARA reading comprehension assessments.

Figure 5. Comparison of the three individuals with aphasia on the three sections of the CARA questionnaire.

All three participants fell below the typical reader cut-off scores on the CARA reading comprehension assessments at single word, sentence, and paragraph level (which were 0.93, 0.89, and 0.78, respectively). On the reading comprehension assessments, overall P1 had the most severe comprehension difficulties, although her numerical score on single-word reading was better than P2ʹs. In section A of the questionnaire about her current reading, she recognised her comprehension difficulties with paragraphs and books and with reading aloud but rated other aspects as “no problem”. In section B, feelings about reading, P1 felt reading was important. She reported that reading was easy that she felt confident when reading and was happy to try. Her main concern was her slow speed of reading. In section C, reading activities, P1 reported that reading text messages and reading on the computer were not applicable; she had never used a mobile phone or computer. She said she had some difficulty reading labels but rated all other reading materials (including newspaper articles, magazines, and books) as “no problem.” Overall, she had the highest score of these three participants on the questionnaire indicating the least problems and concerns about reading. Despite acknowledging her difficulties with paragraphs and books in section A, she reported no difficulty with the reading activities. This could reflect what she was choosing and needing to read was within her level of ability. Comments recorded by the tester during the administration of the questionnaire suggested that P1 was able to read what she wanted to. However, it is possible this reflected poor insight or, despite the aphasia-friendly nature of the questionnaire, misunderstanding of the questions.

P2 had impaired single word and sentence comprehension, with difficulties with complex sentences. Paragraph comprehension was impaired but was a relative strength. When rating his current reading, P2 recognised the difficulty he was having reading sentences, paragraphs, and particularly books. He also reported finding it difficult to concentrate when reading. In terms of reading activities, he had not tried to read magazines or books so said not applicable. He reported finding instructions, formal letters, and newspaper articles hard. Despite these difficulties, he felt quite positive and was not concerned about his reading (section B).

On the reading comprehension assessments, P3 was just outside normal limits in single-word comprehension. Sentence comprehension was impaired, with a mixture of lexical and grammatical errors. Paragraph comprehension was also impaired. P3 reported no difficulty reading words, sentences, paragraphs, and books but said it was hard to concentrate when reading and hard to remember what he read. In section B, he indicated he did not find reading enjoyable or easy, that he was not confident about his reading and not happy with his reading speed. He reported that some reading activities (reading labels, signs, menus, instructions, timetables) were not a problem. He was trying to read letters and magazines but finding them difficult. He was avoiding newspaper articles and books because it was hard to concentrate, and reading was slow.

Discussion

Assessment of Reading Comprehension

Reading comprehension accuracy varied across the group of people with aphasia, with correlations between performance at single word, sentence, and paragraph level. The associations do not mean causation, but the patterns seen are worthy of consideration considering the large number of participants and the use of reliable measures. Whilst multiple comparisons have been carried out, the use of Bonferroni correction mitigates the risk of type 1 errors (false-positive association) and not all associations were significant.

The group data is helpful in considering the potential relationships between lexical and syntactic processing and text comprehension. Lexical comprehension is clearly important across the tasks, and lexical distracters were present in both the sentence and paragraph assessments. The association could, therefore, reflect the overall importance of lexical processing in sentence and paragraph comprehension despite there being no link in the vocabulary used. The significant positive correlation between sentence and paragraph comprehension contrasts with previous studies (Brookshire & Nicholas, Citation1984; Waller & Darley, Citation1978; Wegner et al., Citation1984) that found no relationship between syntactic and discourse comprehension. This could reflect the larger number of participants, influencing the sensitivity of the analysis. The results are though in line with Caplan and Evans (Citation1990) findings in spoken comprehension. Across our participants, if a person had difficulties at sentence level, they were also more likely to have difficulties at paragraph level. The comprehension of the CARA paragraphs did not depend on the understanding of specific syntactic structures, with sentence types in the sentence comprehension tasks different from those occurring within the paragraphs. As in the Caplan and Evans (Citation1990) study, the paragraphs resembled everyday text which can often be mostly understood using lexical knowledge and background context. This does not, however, rule out that the person is parsing the syntactic structure as they read the paragraphs.

The group data masks some of the variability present in individual comprehension performance. Although all three individuals (selected as illustrative case studies) were outside the cut-off scores for typical readers, they presented with different profiles across assessments of single word, sentence, and paragraph comprehension. Whilst the group results demonstrated that lexical, syntactic, and text-level processing are associated at group level, there is the potential for skills to be differentially impaired within individuals, for assessments to draw on different skills, and for individuals to complete assessments in different ways (DeDe, Citation2013). For example, P2 may not have access to the precise semantic information necessary for the word comprehension test, but the repetition and redundancy within paragraphs may facilitate understanding at this level.

Understanding the linguistic difficulties at single word, sentence, and paragraph level may give some insight into what is contributing to strengths in, and difficulties with, everyday reading. However, it currently does not inform the choice of an evidence-based treatment as there has been limited investigation of the impact of linguistic-based treatments targeting single word and sentence processing on text comprehension. Early studies of computer-based hierarchical treatments (Katz & Wertz, Citation1992, Citation1997) showed promising results in terms of overall changes in reading comprehension. However, the impact on everyday reading was not investigated. There needs to be a systematic investigation of the impact of word and sentence-level activities on text comprehension, with consideration of whether gains are maximised if there is a direct link between the targeted words and structures and the everyday text, which is the focus of intervention.

Personal Perception of Reading

At the group level, significant positive correlations were found among self-reported ability and difficulty, feelings about reading, and impact on reading activity; less reported difficulty was associated with more positive feelings about reading and a greater range of reading activities accessed without difficulty. However, the case studies again highlight variability, with different relationships between emotions, difficulties, and activities, again emphasising the importance of considering this at the individual level

Relationship between Assessment Performance and Personal Perception

There was no significant relationship between reading difficulty, as assessed on the comprehension assessments, and personal perception. This is in line with other aspects of aphasia where there is no straightforward relationship between the severity of impairment and its impact on activity and quality of life (Williamson et al., Citation2011). There was a positive, though not significant, trend with people with less severe reading comprehension difficulties on assessment generally rating their reading as less problematic and reporting more positive feelings about their reading. Extensive variability was, however, evident across individuals.

Some people with mild reading difficulties had low questionnaire scores, suggesting a significant personal impact and negative feelings about reading. The wider aphasia literature suggests that even people who score within the normal range on aphasia assessments may still report salient communication difficulties, a need to continually concentrate when engaged in language tasks, and reduced social participation (Cavanaugh & Haley, Citation2020; Cruice et al., Citation2006). This may be because the demands of the linguistic assessments are not in line with the demands of everyday communication. Alternatively, people with less severe difficulties may be attempting to carry out activities, which approximate more closely to their pre-morbid reading, so any difficulties are more apparent and then cause frustration.

Some individuals with severe reading comprehension difficulties had high questionnaire scores. This could be due to a lack of insight and would be consistent with previous literature, which has suggested that some individuals lack awareness of their spoken comprehension difficulties (Knollman-Porter et al., Citation2018). It was not clear whether P1 had good insight into her reading difficulties. In the questionnaire, she acknowledged some difficulties reading paragraphs and books. She felt positive about her reading and reported no problems with reading activities that were relevant to her. So, despite severe comprehension difficulties, she had the highest score on the questionnaire. Reading was important to her, but the profile on the questionnaire may suggest it would not be a high priority for intervention.

Differences between assessed reading comprehension ability and personal perception would also be present if individuals were aware of their reading difficulties but wanted to underplay these due to embarrassment and a desire to appear competent. Individual variability may also reflect inherent variation in the importance of reading and reading preferences. Individuals may have insight into their reading ability but if skills are sufficient for their everyday needs, and they can read what they want and need to, the reading difficulties may have minimal impact on their feelings about reading and reading activity. For example, P2 showed preserved insight into his reading difficulties, with ratings of reading difficulty that were in line with the comprehension assessments. He was though not concerned about his reading, reporting no negative feelings within section B of the questionnaire and no apparent difficulties with relevant reading activities. This would suggest that reading would not be a high priority for intervention for him. In contrast, reading was very important to P3, and he was concerned and upset about his reading difficulties. For him, reading would be a priority for intervention. He found it hard to read extended text, attributing the difficulty to concentration and memory. It is, however, not clear what he is rating as “memory.” Recognising the complexity of text comprehension, it is important to consider the impact of wider cognitive skills, analysing the extent to which attention, working memory, and executive function support or are a barrier to reading for an individual and how these factors might contribute to intervention.

The case studies highlight the complexity of individual factors that influence a person’s perception of their reading. There is no straightforward relationship between the severity of reading difficulties and their perceived impact. This complex relationship between linguistic measures and personal perception is also seen in intervention studies. There is no straightforward relationship between changes in text-level reading post-intervention and reported changes in reading activity and feelings about reading. Webster et al. (Citation2013) described four individuals with aphasia who all showed some numerical changes in the accuracy of paragraph comprehension following intervention. They also reported some positive changes, but there was individual variation about whether the change was in overall feeling about reading (confidence, frustration), in reading choice/frequency of reading or in reading ability. One individual (DB) rated his overall reading ability more negatively following therapy, saying he sought more help from his wife but his reading activities had changed positively. Post-therapy, he could read food labels (a concern pre-therapy) and varied lengths of text.

Clinical Implications

While there is an emerging evidence base about text-level reading interventions (see, Purdy et al., Citation2019; Watter et al., Citation2017), there is still a need to develop a better understanding of what influences an individual’s reading and design treatments that integrate relevant factors (Pierce, Citation1996). The complex relationship between assessments of reading and individual perception underlines the importance of considering both when agreeing goals, selecting a treatment approach, and measuring outcome. An individual will want to consider whether reading is important to them and should be a focus for intervention, potentially balancing the impact that their reading difficulties have on their quality of life with the impact of other aspects of aphasia. Goal setting in reading (as in other areas) should always be underpinned by an understanding of a person’s individual needs and wishes (Pierce, Citation1996). An individual’s feelings about their reading, the extent to which their reading difficulties impact reading activities/materials and how those activities relate to participation in everyday activities and access to technology will shape specific goals about what a person wants to read or change about their reading. The goals may include changes in reading comprehension, changes in reading speed or compensating for the reading difficulty but still allowing participation in the activity, for example, the use of audiobooks or text to speech. The focus on meaningful individual goals does not, however, reduce the need to understand a person’s reading difficulties.

Conclusion

This study provides insight about reading in people with aphasia and in particular, the relationship between reading comprehension at different linguistic levels and personal perception of reading. Comprehension at single word, sentence, and paragraph level is correlated. There was also a strong association between different aspects of personal perspective: reported reading difficulty, feelings about reading, and reading activity. There was extensive individual variation across the group in terms of reading ability as assessed by the reading comprehension tasks, reported reading difficulty, feelings about reading, and the impact on reading activity. There was, therefore, no correlation between reading comprehension assessment performance and personal perception.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the members of the Aphasia Research User Group (ARUG) who shaped the direction of the project, Jenny Malone, Maria Garraffa, and Lois McCluskey for their assistance with data collection, all of the participants for contributing their time and the individuals and organisations who assisted with recruitment to the study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Brookshire, R. H., & Nicholas, L. E. (1984). Comprehension of directly and indirectly stated main ideas and details in discourse by brain-damaged and non-brain-damaged listeners. Brain and Language, 21(1), 21–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/0093-934X(84)90033-6

- Brookshire, R. H., & Nicholas, L. E. (1993). Discourse Comprehension Test. Communication Skill Builders.

- Caplan, D., & Evans, K. L. (1990). The effects of syntactic structure on discourse comprehension in patients with parsing impairments. Brain and Language, 39(2), 206–234. https://doi.org/10.1016/0093-934X(90)90012-6

- Cavanaugh, R., & Haley, K. L. (2020). Subjective communication difficulties in very mild aphasia. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 29(1S), 437–448. https://doi.org/10.1044/2019_AJSLP-CAC48-18-0222

- Chesneau, S., & Ska, B. (2015). Text comprehension in residual aphasia after basic-level linguistic recovery: A multiple case study. Aphasiology, 29(2), 237–256. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038.2014.971098

- Cruice, M., Worrall, L., & Hickson, L. (2006). Perspectives of quality of life by people with aphasia and their family: Suggestions for successful living. Topics in Stroke Rehabilitation, 13(1), 14–24. https://doi.org/10.1310/4JW5-7VG8-G6X3-1QVJ

- DeDe, G. (2013). Reading and listening in people with aphasia: Effects of syntactic complexity. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 22(4), 579–590. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038.2013.843151

- Goodglass, H., & Kaplan, E. (1972). The Boston Diagnostic Aphasia Examination. Lea & Febiger.

- Hale, S. (2003). The man who lost his language. Penguin Books Ltd.

- Katz, R. C., & Wertz, R. T. (1992). Computerized hierarchical reading treatment in aphasia. Aphasiology, 6(2), 165–177. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687039208248588

- Katz, R. C., & Wertz, R. T. (1997). The efficacy of computer-provided reading treatment for chronic aphasic adults. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 40(3), 493–507. https://doi.org/10.1044/jslhr.4003.493

- Kintsch, W. (1988). The role of knowledge in discourse comprehension: A construction-integration model. Psychological Review, 95(2), 163. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.95.2.163

- Kjellén, E., Laakso, K., & Henriksson, I. (2017). Aphasia and literacy—the insider’s perspective. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 52(5), 573–584. https://doi.org/10.1111/1460-6984.12302

- Knollman-Porter, K., Dietz, A., & Dahlem, K. (2018). Intensive auditory comprehension treatment for severe aphasia: A feasibility study. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 27(3), 936–949. https://doi.org/10.1044/2018_AJSLP-17-0117

- Knollman-Porter, K., Wallace, S. E., Hux, K., Brown, J., & Long, C. (2015). Reading experiences and use of supports by people with chronic aphasia. Aphasiology, 29(12), 1448–1472. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038.2015.1041093

- Meteyard, L., Bruce, C., Edmundson, A., & Ayre, J. (2010). Intervention for higher level reading difficulties: A case study. Paper presented at the British Aphasiology Society Therapy Symposium, Newcastle.

- Meteyard, L., Bruce, C., Edmundson, A., & Oakhill, J. (2015). Profiling text comprehension impairments in aphasia. Aphasiology, 29(1), 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038.2014.955388

- Morris, J., Webster, J., Howard, D., & Garraffa, M. (in preparation). Comprehensive Assessment of Reading in Aphasia (CARA). Newcastle University.

- Morris, J., Webster, J., Howard, D., Giles, J., & Gani, A. (2015). Reading comprehension in aphasia: The development of a novel assessment of reading comprehension.

- Parr, S. (1992). Everyday reading and writing practices of normal adults: Implications for aphasia assessment. Aphasiology, 6(3), 273–283. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038.2014.955388

- Parr, S. (1995). Everyday reading and writing in aphasia: Role change and the influence of pre-morbid literacy practice. Aphasiology, 9(3), 223–238. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687039508248197

- Parr, S. (2007). Living with severe aphasia: Tracking social exclusion. Aphasiology, 21(1), 98–123. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687030600798337

- Pierce, R. S. (1996). Read and write what you want to: What’s so radical? Aphasiology, 10(5), 480–483. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687039608248427

- Porch, B. E. (1967). The Porch Index of Communicative Ability. Consulting Psychologists Press.

- Purdy, M., Coppens, P., Madden, E. B., Mozeiko, J., Patterson, J., Wallace, S. E., & Freed, D. (2019). Reading comprehension treatment in aphasia: A systematic review. Aphasiology, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038.2018.1482405

- Smith, K. G., & Ryan, A. E. (2020). Relationship between single word reading, connected text reading and reading comprehension in persons with aphasia. American Journal of Speech and Language Pathology 29(4), 2039–2048. https://doi.org/10.1044/2020_AJSLP-19-00135

- Spreen, D., & Benton, A. L. (1969). The neurosensory center comprehensive examination for aphasia. Department of Psychology, University of Victoria.

- Stachowiak, F. J., Huber, W., Poeck, K., & Kerschensteiner, M. (1977). Text comprehension in aphasia. Brain and Language, 4(2), 177–195. https://doi.org/10.1016/0093-934X(77)90016-5

- Waller, M. R., & Darley, F. L. (1978). The influence of context on the auditory comprehension of paragraphs by aphasic subjects. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 21(4), 732–745. https://doi.org/10.1044/jshr.2104.732

- Watter, K., Copley, A., & Finch, E. (2017). Discourse level reading comprehension interventions following acquired brain injury: A systematic review. Disability and Rehabilitation 39(4), 315–337. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2016.1141241

- Webb, W. G., & Love, R. J. (1983). Reading problems in chronic aphasia. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders, 48(2), 164–171. https://doi.org/10.1044/jshd.4802.164

- Webster, J., Morris, J., Connor, C., Horner, R., McCormac, C., & Potts, A. (2013). Text level reading comprehension in aphasia: What do we know about therapy and what do we need to know? Aphasiology, 27(11), 1362–1380. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038.2013.825760

- Webster, J., Morris, J., Howard, D., & Garraffa, M. (2018). Reading for meaning: What influences paragraph understanding in aphasia? . American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 27(1S) , 423–437. https://doi.org/10.1044/2017_AJSLP-16-0213

- Webster, J., Morris, J., Malone, J., & Howard, D. (2021). Reading comprehension difficulties in people with aphasia: Investigating personal perception of reading ability, practice and difficulties. Aphasiology 35(6), 805–823. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038.2020.1737316

- Webster, J., Samouelle, A., & Morris, J. (2018). The brain can’t cope”: Insights about reading from people with chronic aphasia. PsyArXiv. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/p8xh4

- Wegner, M. L., Brookshire, R. H., & Nicholas, L. E. (1984). Comprehension of main ideas and details in coherent and noncoherent discourse by aphasic and nonaphasic listeners. Brain and Language, 21(1), 37–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/0093-934X(84)90034-8

- Williamson, D. S., Richman, M., & Redmond, S. C. (2011). Applying the Correlation Between Aphasia Severity and Quality of Life Measures to a Life Participation Approach to Aphasia. Topics in Stroke Rehabilitation, 18(2), 101–105. https://doi.org/10.1310/tsr1802-101