ABSTRACT

Background

A Conversation Partner Scheme (CPS) can provide an opportunity for students to learn about acquired communication disorders, develop skills to support adults in conversations and reflect on their personal attitudes about communication disability. It can also enhance communication, facilitate social inclusion and participation and increase well-being for CPS partners with acquired communication disabilities. The format of a CPS generally includes conversation-training workshops followed by face-to-face supported conversations. The COVID-19 pandemic and associated public health guidance necessitated the transition of all components of the scheme (training and conversations) to an online format.

Aims

The aim of this case study was to investigate the feasibility of an online CPS and explore the participants’ experience of this format.

Methods & Procedures

A case study design was undertaken with feasibility objectives examining Implementation, Practicality, Adaption, Integration and Acceptability of the online CPS. Data was gathered from students using questionnaires. Online semi-structured interviews were carried out with seven persons with aphasia (PwA) who participated as CPS partners. Technical challenges, duration of conversations and topics of conversations were also recorded.

Results and Conclusions

Twenty-seven speech and language therapy students and 14 CPS partners took part in the CPS. Eighty-five online conversation sessions were carried out. All seven PwA and many of the students (87.5%) perceived an online format as suitable for CPS conversations. However, many students highlighted the value of in-person contact and reported that the online format constrained the use of some communication ramps. The PwA repeatedly commended their student conversation partners and noted the CPS provided an opportunity for increased social interaction during the public health restrictions. The online CPS provided a timely opportunity for students to practice supported communication skills and was perceived to be important for student training and communication skills development.

Introduction

Communication partner training (CPT) is an environmental intervention usually aimed at people other than the person with aphasia, with the goal of enhancing the language, communication, participation, and/or well-being of the person with aphasia (Simmons-Mackie et al., Citation2010) by using communication resources and strategies. In their updated review of CPT in aphasia, Simmons-Mackie et al. (Citation2016) noted variation in the types of training across formats (group, dyad, individual), communication partners (family members, healthcare providers, students) and duration of training with most programmes typically taking between 10 to 15 hours. Within the studies included in this review, many CPT programmes are described as adaptations from Supporting Partners of People with Aphasia in Relationships and Conversation (Lock et al., Citation2001), Supported Conversations for Adults with Aphasia (Kagan, Citation1998) and Connect Communication Partner Scheme (McVicker et al., Citation2009). Materials used in CPT include videos, written information and other props integrated within a variety of intervention procedures including direct teaching/education sessions, role play, group discussions and feedback (Cruice et al., Citation2018). Trained people with aphasia may also be involved in CPT (Cruice et al., Citation2018). These trainers with aphasia have undertaken training themselves, and are directly involved in the delivery of CPT by providing conversation practice followed by immediate feedback to trainees (Cruice et al., Citation2018; Finch et al., Citation2020; McMenamin et al., Citation2015a; McVicker et al., Citation2009). One notable trend in research on CPT is the “move out of the research laboratory and into real-life settings” (Simmons-Mackie et al., Citation2016, p. 2219). The use of CPT has increased in health education training (Hoepner & Sather, Citation2020; Simmons-Mackie et al., Citation2016). There are a number of available studies that explore CPT delivered to a variety of healthcare students including physiotherapy and occupational therapy (Cameron et al., Citation2015; Power et al., Citation2020), nursing assistants (Welsh & Szabo, Citation2011), medical students (Legg et al., Citation2005) and speech and language therapy (SLT) students (Finch et al., Citation2017; McMenamin et al., Citation2015a). In general, in CPT studies of student learning, students undertake training in the higher education setting (Cameron et al., Citation2015; McMenamin et al., Citation2015a; Welsh & Szabo, Citation2011) followed by a single opportunity for conversation with a trained person with aphasia (Cameron et al., Citation2015; Welsh & Szabo, Citation2011) or repeated opportunities to visit a person with aphasia in a variety of locations such as their own home, a café or clinic (McMenamin et al., Citation2015a) as part of a Conversation Partner Scheme (CPS). A CPS involves trained volunteers or students who have completed education sessions on supporting communication, visiting people with aphasia, usually in their own homes or residential settings for the purpose of engaging in conversations (McVicker et al., Citation2009). A key element of CPS is the repeated opportunities for conversation in order to reduce social isolation for a person with aphasia. These repeated visits may vary from a period of 10-12 weeks, as part of an academic module (McMenamin et al., Citation2015a), up to 6 months (McVicker et al., Citation2009).

Engaging in a CPS increases students’ confidence and recall of strategies when communicating with a person with aphasia (Jagoe & Roseingrave, Citation2011; McMenamin et al., Citation2015b). In addition, participating in CPT has also been shown to increase students’ use of effective communication behaviours during conversations with people with aphasia (Finch et al., Citation2017). Students have reported that the practical experience of engaging in CPT allowed them to apply communication strategies in practice with a person with aphasia and this has helped them to gain a better understanding of aphasia and prepared them for future clinical education and practice (Cameron et al., Citation2018).

In addition to the benefits for students outlined above, participation in a CPS has been shown to promote successful communication and reduce social exclusion among people with aphasia (McMenamin et al., Citation2015a; McVicker et al., Citation2009). The participants with aphasia in a study by McMenamin et al. (Citation2015a) described transformative experiences related to identity, independence and confidence following engagement in the programme. The benefits of increased confidence and purpose were also noted among participants with aphasia involved in a CPT programme with occupational therapy, physiotherapy and SLT students (Cameron et al., Citation2018), with participants indicating they would recommend CPT to others and they would like to be involved in future programmes.

Lee et al. (Citation2020) explored the outcomes and perceptions of people with aphasia engaging in online supported conversations with SLT students. Their findings indicate that people with aphasia may experience psychosocial benefits from the online conversations, and four of the five participants with aphasia reported that telepractice was suitable for conversing with students. The one participant who didn’t consider telepractice to be suitable indicated a preference for face-to-face interactions and reported experiencing technology difficulties in the beginning. The authors highlight that these findings should be considered with caution as this pilot study included a small sample of people with aphasia (Lee et al., Citation2020). However, these are also supported by findings from Cruice et al. (Citation2020) who noted gains in participants’ confidence, social participation and quality of life following a personalised supported conversation intervention delivered online by qualified or student SLTs.

As noted above, a move to online delivery of CPT has emerged in student education. A recent study explored the feasibility of an online conversation with a trained person with aphasia as part of a CPT programme for SLT students (Finch et al., Citation2020). The students attended an educational session delivered in person, followed by the online conversation experience. A statistically significant increase in students’ self-rating of confidence when communicating with people with aphasia, as well as their proficiency at engaging in everyday conversations and obtaining a case history, was noted following the online conversation experience. One group of students received feedback immediately after the online conversation, the second group did not receive feedback. Both groups reported the online conversation was a positive learning experience but the no-feedback group reported more challenging elements (e.g. awkward pauses, ran out of topics etc.) than the feedback group. The authors concluded the online format is feasible and can provide a valuable learning experience for students (Finch et al., Citation2020). Power et al. (Citation2020) also examined students’ outcomes with the Aphasia Attitudes, Strategies and Knowledge survey following CPT, in their pilot randomised control trial comparing online and face-to-face training. A 45-minute CPT programme, based on Supported Conversations for Adults with Aphasia (Kagan, Citation1998) was developed for the study in both a face-to-face and online delivery format. Undergraduate Occupational Therapy and Physiotherapy students were recruited and divided into three groups comparing the online CPT programme, the face-to-face CPT programme, and the delayed training control (no programme). The findings indicate that the online delivery is as efficacious as face to face delivery in improving students’ overall knowledge and attitudes towards aphasia, as well as knowledge of facilitative communication strategies (Power et al., Citation2020).

In the studies outlined above, the training and conversations with people occurred face-to-face, in universities or other locations, and online via telepractice. However none of the studies included a fully online implementation and delivery of training and repeated conversations within a CPS without any face-to-face contact.

The CPS in our study has been running in the University of Limerick since 2008 and is delivered as part of the students’ first practice education module in the first semester of first year of the programme. Historically, students completed 4 x 3 hour face-to-face educational sessions based on Connect – The Communication Disability Network (McVicker, Citation2007) and principles of supported conversation (Kagan, Citation1998). These sessions introduce students to the concept of conversation and communication disability and incorporate video materials along with group discussion, role play and feedback in order to identify techniques to support conversations. These methods are common features of many CPT programmes (Cruice et al., Citation2018). Following the education sessions, the students went in pairs to visit an allocated CPS partner with acquired communication disability in their own homes or nursing homes one hour a week for up to eight weeks.

With the emergence of COVID-19, public health restrictions were introduced in March 2020 and although these were initially eased in June (Kennelly et al., Citation2020) there was a clear understanding of the precarious nature of the public health situation in Ireland and across the globe. At the core of the CPS is the social inclusion, through supported conversations (McVicker et al., Citation2009), of adults who in many cases would be considered more vulnerable and therefore likely to be cocooning in the midst of this crisis. It was not considered prudent or appropriate for students to complete face-to-face visits as part of the CPS until the vaccination rollout was underway. In response to public health guidance to combat the spread of COVID-19, Ellis and Jacobs (Citation2021) advocate it is more important than ever to feel socially connected, in what has become “an increasingly isolated world” (Ellis & Jacobs, Citation2021, p. 1). Isolation due to social distancing could intensify an individual’s communication disability and Ellis and Jacobs (Citation2021) propose “physical distancing with social connectedness (PDSC) (Ellis & Jacobs, Citation2021, p.1) as a means to combat this. They recommend PDSC aphasia therapy/support groups as well as connecting students with older adults for the purpose of virtual conversations as methods of supporting PDSC.

It was necessary to explore alternative options to ensure the CPS could be delivered and as noted previously online CPT and supported conversations are feasible for student learning (Finch et al., Citation2020; Power et al., Citation2020) and acceptable to people with aphasia (Lee et al., Citation2020). All of the CPT studies detailed above incorporated some element of in-person support alongside the online delivery. This included in-person support for trained people with aphasia during one-off conversations with students (Finch et al., Citation2020) or in order to set up digital devices for people with aphasia to access online platforms for supported conversations (Cruice et al., Citation2020). All aspects of the CPS in our study, including training and support, were carried out online. Therefore, the aim of this case study was to investigate the feasibility and participant experiences of an online CPS as part of a speech and language therapy pre-registration qualification programme.

Methods

Case study design

The ability to investigate a phenomenon in its natural context is a key strength of case study design and case studies are a useful tool for examining the world around us (Rowley, Citation2002). This case study examines a single CPS, as a learning experience and an intervention delivered within a University programme, involving student SLTs and people with acquired communication disabilities using both quantitative and qualitative data analysis approaches. Exploring the feasibility of an intervention can provide important information about whether an intervention is relevant, sustainable and appropriate for further testing (Bowen et al., Citation2009). In our study we explore five feasibility elements including Implementation, Practicality, Adaption, Integration and Acceptability (Bowen et al., Citation2009) of the online CPS among students and persons with acquired communication disabilities. The description of each element and the data collection method is outlined in . In addition to these feasibility elements, it is important to gain an in-depth understanding of participants’ experiences of the online CPS in order to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the phenomenon being examined in this case study. Ethical approval for this study was received from the University of Limerick Research Ethics Committee (Ethics Approval Number EHSREC 2020_09_03).

Table 1 Feasibility elements and data collection measures

Participants in the Conversation Partner Scheme

This study examines the experiences of two groups who engaged in the online CPS format; student SLTs and people with acquired communication disabilities.

Speech and language therapy students

The students in this study had just commenced the first semester of their first year on the MSc. Speech and Language Therapy programme in the University of Limerick. They completed the 4 x 3 hour training sessions, as noted earlier, which were delivered remotely rather than in person. Under the National Vetting Bureau (Children and Vulnerable Persons) Acts 2012 to 2016, the University is required to conduct Garda Vetting on all students who go on placement where such activity brings them into contact with vulnerable adults or children. This is a process to check whether an individual has a criminal record or if they may pose a threat to vulnerable people and is a pre-placement requirement. Student can commence the CPS once this is completed. There were minor delays with the verification of this process due to administrative issues with remote working and this resulted in delays for some students commencing the online conversation sessions in the CPS. Twenty-seven student speech and language therapists took part in the CPS and nineteen students consented to participate in the research.

People with acquired communication disabilities

Individuals who previously engaged in the face-to-face CPS were offered an opportunity to be involved in the online format of the scheme. In addition, referrals for the CPS were received from local speech and language therapy services and voluntary agencies that support people with acquired brain injuries. All participants were over 18 years of age and had access to an internet-enabled digital technology device. Referrals were accepted from individuals experiencing acquired communication difficulties due to a variety of aetiologies including stroke, traumatic brain injury, brain tumour and neurodegenerative disease.

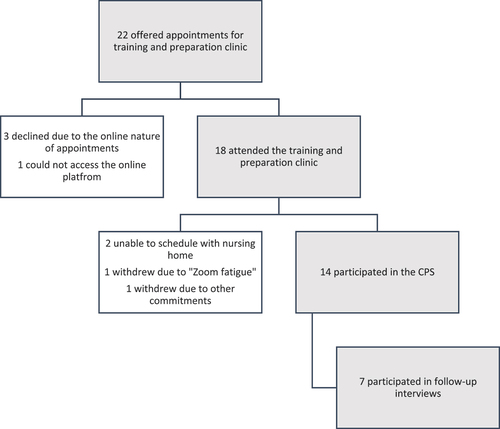

Twenty-two adults with a variety of acquired communication disorders including aphasia, cognitive-communicative disorder, apraxia of speech and dysarthria were offered appointments in a preparation and training clinic prior to the commencement of the CPS. displays the participant flow chart.

Three declined the training due to the online nature of the conversation sessions and one individual was unable to access the online platform despite repeated attempts at troubleshooting the technical issues over the phone. Eighteen individuals attended the training sessions including two who were residing in a local nursing home. Following the final training session, there was a four-week break before the initial conversation sessions were scheduled, while the training for the students took place. During this period, two individuals withdrew from the CPS. In addition, scheduling sessions with the staff in the nursing home became problematic. Ultimately, this meant the two nursing home residents were not able to access the CPS without the staff support. Fourteen individuals with acquired communication disabilities took part in the CPS. Twelve of the CPS partners presented with aphasia, some of these presented with co-occurring cognitive and/or speech disorders, and two of the CPS partners presented with a motor speech disorder. Seven of the CPS partners consented to participate in the evaluation of the online CPS experience. provides participant details for the seven persons with aphasia (PwA) who participated in the interviews. Two PwA also presented with cognitive difficulties (memory and organisational difficulties which required additional support when scheduling and setting up online conversation sessions) and one PwA also presented with apraxia of speech.

Table 2 Characteristics of Persons with Aphasia (PwA)

Preparation for online delivery of the CPS

In order to transition the CPS to a new online format, a training and preparation clinic for people with acquired communication disabilities was developed in summer 2020. The aim of this clinic was to support individuals with acquired communication disabilities, and their families, to access the online platform and engage in online conversation sessions. Two speech and language therapy students facilitated this clinic as part of their final placement, under the supervision of the first author.

Adults with acquired communication disabilities, or their named family member, were contacted by phone to arrange an initial online appointment on the Microsoft Teams Platform. A paper-based aphasia-accessible instruction manual for accessing MS Teams was developed and posted to each CPS partner and a PDF version was also sent by email in advance of the first session. The initial session included troubleshooting access to the meeting platform and an informal assessment of language and technology skills and usage. The informal assessment explored naming, repetition, spoken comprehension and discourse using semi-structured interview and picture description methods (Thomson et al., Citation2018). The technology skills and usage screening tool was modified from existing tools used in aphasia research (Kearns et al., Citation2020; Roper et al., Citation2014). Subsequent sessions, up to a maximum of six, focused on repeated opportunities for familiarisation with the online platform including screen sharing where possible. All sessions were delivered remotely with no in-person contact. This training and preparation clinic provided opportunities for individuals to become familiar and confident with online conversations prior to commencing the CPS in the autumn semester.

Following the training for students and people with acquired communication disabilities, the students were allocated in pairs to a single CPS partner. The students who were paired with CPS partners with motor speech disorders and co-occurring cognitive difficulties were provided with additional guidance in order to support their online conversations. The initial online conversation was scheduled by the first author in order to facilitate introductions online and assist with any technical issues. The students scheduled all subsequent sessions on MS Teams, at a time convenient for their CPS partner, during an allocated afternoon in the student timetable, for remaining eight weeks of the semester.

Data collection methods

Data was gathered separately from the students and the PwA, and the data collection methods are described below.

Weekly survey - Students

During the CPS, the students completed a brief online survey following each weekly conversation. This weekly survey gathered information on the duration of the session, a brief description of any technical issues and the topics discussed.

Post CPS questionnaire - Students

Following the CPS, the students were invited to complete an online questionnaire on their experiences during the CPS (see Supplemental Material). The questions included closed-question formats with binary choice and Likert scale responses as well as open-ended questions which allowed for richer, more in-depth answers. The questionnaire investigated prior experience of communicating with adults with acquired communication disabilities, as well as perceptions of the programme and the online format. The link to the online questionnaire was accessible for four weeks following the final conversation session. Twenty-seven of the first year student speech and language therapists took part in the CPS and nineteen students consented to participate in the research. Students were not required to provide an answer before progressing to the next question in the online survey and not all students answered each question in the online questionnaire. Each question had a minimum of 15 responses.

Semi-structured interviews – PwA

The PwA were invited to participate in semi-structured interviews to explore their experience of the CPS. Information sheets were both emailed and posted and a follow up phone call was carried out to explain the study. The interviews took place online using the MS Teams platform and were scheduled during the four weeks following the final conversation session. At the beginning of the session all participants were provided with an opportunity to ask questions about the research. When informed consent was obtained, participants were asked to sign the consent sheet and hold it up to the camera so a screenshot could be taken. The question format in the interview was similar to those provided to the students (see Supplemental Material). The questions explored perceptions of the CPS and its online format, and reflect those used in a previous study of telepractice (Lee et al., Citation2020). All interviews were recorded using the inbuilt recording function in MS Teams and saved to the secure University server. Questions were presented in aphasia-accessible format on PowerPoint slides using the MS Teams screen share function. Written keywords, gesture, and online images were also used to support communication during the interviews. The first author facilitated the online interviews and she was known to all participants due to her role coordinating the CPS. In order to reduce the potential for only positive feedback, she impressed the point that all their opinions, positive and negative were welcome during the interview.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics and quantitative analysis (counting and ranking) were performed for numeric data obtained from closed questions in the student questionnaires and the interviews with PwA. For the interviews, the initial transcription process began by downloading and tidying the MS Teams transcript which was created during the recording process on the online platform. Each interview was reviewed by the first author and the transcript was prepared following a structured protocol (McLellan et al., Citation2003) in order to manage consistency in formatting and labelling of the transcript. The second author reviewed all transcripts against the recorded interviews and finalised the transcripts. All interview transcripts, as well as student responses to the open field questions were imported into NVivo 12, a qualitative data analysis software, in order to organise and store the data. Both datasets (PwA and students) were analysed separately using Qualitative Content Analysis (Elo & Kyngäs, Citation2008; Graneheim & Lundman, Citation2004). As part of the initial step of the inductive content analysis approach, each interview transcript was deemed a single unit of analysis and read through to obtain a sense of whole. The two authors coded the data separately before coming together to discuss and refine the codes. Following this process of open coding, the authors reviewed the transcripts to ensure all relevant data was coded and then collaboratively identified the potential list of categories and grouped these under headings. Again these were reviewed and the underlying, recurring meanings were abstracted in order to further develop the categories and finally define and describe the themes. This analysis process was repeated for the open field responses from the students’ questionnaires but here the combined responses to each question represented a unit of analysis.

Results

The findings on the feasibility of the online format and the experiences of those involved in the CPS are presented below. The quantitative data investigating the five feasibility elements (Implementation, Practicality, Adaption, Integration and Acceptability) is presented first. The responses to binary choice and Likert scale questions from the seven PwA are presented in and student responses are summarised in . This is followed by the qualitative analysis of the participants’ experiences which also helps to further inform, and provide context to the feasibility elements explored in this study. Finally, a summary of the feasibility of the CPS in this case study is reported before the findings are discussed.

Table 3 Responses from Persons with Aphasia (PwA)

Table 4 Responses from Student Speech and Language Therapists

Table 5 Speech and Language Therapy Students Supporting Quotes Categories and Themes

Table 6 People with Aphasia Supporting Quotes, Categories and Themes

Implementation of an online CPS

Ninety-one sessions were scheduled over the semester and 85 sessions took place. Some of the sessions were cancelled as they were inadvertently scheduled on a public holiday and the CPS partners chose not to attend. In other cases, the CPS partner cancelled due to conflict in scheduling with other appointments or activities. Technology issues occurred in twenty sessions (24%) and were reported by 11/17 students and three of the PwA. These issues included difficulties finding/using the MS Teams link, turning on the camera, problems with WiFi connection and gallery view on the MS Teams platform. No sessions were abandoned due to technical issues. In most cases these issues happened early in the CPS and were resolved as the CPS progressed.

Practicality of an online CPS

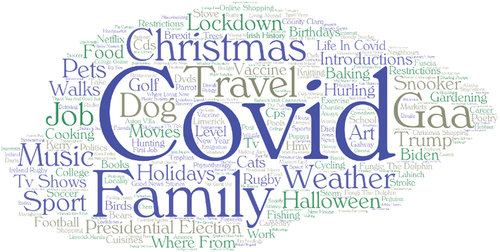

The sessions ranged from 15 to 100 minutes with an average session duration of 53 minutes. A variety of conversation topics were discussed and are represented in the word cloud in (). The most common topic of conversation was COVID-19, along with the associated public health restrictions and their impact on sports, shopping, travel and contact with others. Not being able to see gestures and facial expression and a less natural conversation online were reported by some students (5/16) as elements that they liked least when using the online platform.

Adaptability and Integration of an online CPS

Prior to the CPS, 43.75% (7/16) of students reported having no experience of talking with adults with acquired communication disabilities face-to-face and only one respondent had experience talking with people with acquired communication disabilities online. Most students agreed that the training sessions prepared them for online conversations (13/16) and reported feeling confident (13/16) about their ability to converse online with people with acquired communication disabilities. Three students neither agreed nor disagreed with these statements. The majority of students (15/16) agreed that the CPS would help them to talk to people with acquired communication disabilities in future placements.

Acceptability of an online CPS

All seven PwA reported that the online platform was suitable for conversations. They would recommend the CPS to others but noted that it is an individual choice and one respondent identified that he did not know other people with aphasia. All students felt it was important to engage in the CPS as part of their practice education curriculum and most (14/16) agreed that telepractice was a suitable way to have online conversations but two students did not agree that the online format was suitable.

Participants' experiences

The students’ responses to open-ended questions and the semi-structured interviews from the PwA offer further information on the feasibility of the online format as well as providing insight into their experiences of the CPS. One shared theme exists between the two groups Technology as a Barrier and Facilitator, while other themes are unique to each group. Two additional themes were identified in the data from the students: CPS as a Mutually Beneficial Experience and Valuable Learning Experience under the Conditions, while three further themes were identified within the interview data from the PwA: Valuable Learning Experience, The Power of Conversation and Reflection, Appraisal and Looking Forward. Each theme is discussed briefly below. provide an overview of themes, categories and supporting quotes following the qualitative content analysis of student responses and the interviews with PwA.

Shared theme - Technology as a Barrier and Facilitator

Both groups identified the use of digital technology as both a barrier and facilitator to engagement with the CPS. The initial set up provided some challenges that required trouble shooting or support from family members but as the CPS progressed these issues diminished. Both groups reported that the online format provided a convenient means of communicating during the public health restrictions. With one student noting the benefits of the online sessions including “not having to go out to a place, no commute, easier to schedule”.

The students were concerned about the technical literacy skills required by PwA to access the CPS, while the PwA highlighted that others with acquired communication difficulties may not have access to digital devices or the Internet and this could exclude their participation from the CPS.

Two of the PwA reported they were new to online conversations but all agreed that the use of an online platform for conversations was appropriate for the CPS. The public health guidance included restrictions on travel and the ability to connect with students without any need for travel was a clear advantage of the online format.

“Ehm … Well, first of all, you don’t have to go there … and [secondly], [secondly], with the, with the [/coroba/] with the, eh, Corona and everything you can’t.” PwA3

Although the students were also open to the potential practicality, flexibility and convenience of this mode of communication, they reported that the online format constrained their use of some communication ramps that can support conversation. A number of students (n=6) noted that they would prefer to engage in face-to-face conversations, reflecting a sense of a missed opportunity engaging in the online format.

“In person I believe would be better, but online is adequate” Student SLT

However, many students and PwA identified that digital technology is now part of daily living and using an online platform for conversations provided an acceptable alternative to the traditional visits to CPS partners in the community in light of the public health situation. The impact of COVID-19 prompted many to expand their use of online platforms and mobile applications in order to maintain and regain social connections in a virtual world when public health restrictions reduced the opportunities for these connections in the physical world.

“It worked for the situation we are in with the pandemic” Student SLT

“Well, I’m just I haven’t got … I haven’t tried the, ehm … the only one I’ve tried is the WhatsApp one … eh, d’you know, connecting to other people that way, but I, I haven’t really done the others” PwA7

Themes - Student Speech and Language Therapists

Two additional themes were identified in the data from the students: CPS as a Mutually Beneficial Experience and Valuable Learning Experience under the Conditions and Technology as a Barrier and Facilitator.

In the theme, CPS as a Mutually Beneficial Experience, the act of engaging in conversation as part of the CPS allowed for meaningful social interactions for all who participated. The weekly online sessions provided an opportunity for repeated interactions with the same CPS partner and the students enjoyed the opportunity to develop their communication skills through this social activity.

“It was great to get the opportunity to meet each week and just have general conversation” Student SLT

All students identified positive aspects of the CPS and highlighted how they enjoyed the experience and perceived that their CPS partners also appreciated the opportunity to talk to someone. One student reported that it “felt like we were brightening their day with our conversations”. The students perceived the opportunity to engage in the CPS as beneficial for both people with acquired communication disabilities and students.

“It allowed the CPS partner the space to discuss some of their interests but also I learned more about how to effectively communicate and help the CPS partner … ” Student SLT

In the theme, Valuable Learning Experience under the Conditions, the CPS was reported to be a positive experience that provided opportunities for learning and professional development. This is also reflected in the responses from the PwA during their interviews but unlike the PwA, who tended to focus on many of the positive aspects of the online CPS, the students highlighted many of the constraints when communicating in the online environment. Although the CPS is noted to provide a valued opportunity for learning, there was a perceptions from some students (n=6) that something was missing, with one noting “I think the experience is valuable I’m just not sure if the format is ideal”. The students reflected on the practical experience, delivered at the early stage of the programme, and how this helped to prepare them for future placements. One student noted:

“I think it is important to get used to dealing with a clinical population straight away. I think that my confidence has grown and that this experience will stand to me in the future.” Student SLT

Themes - PwA

In addition to the shared theme, three further themes were identified within the interview data from the PwA: Valuable Learning Experience, The Power of Conversation and Reflection, Appraisal and Looking Forward.

The first unique theme, Valuable Learning Experience, explored their perceptions of their role in facilitating student learning and development. The CPS was considered an important, positive learning experience for the students and as PwA4 reported, the CPS was “good for the students”. All the PwA identified how the CPS helps to further develop the students’ conversation skills for their future interactions with adults with acquired communication difficulties, as one PwA highlighted:

“they (students) may have met other people, but then they can think of what they could do in the future, and they can be quicker or better because of the past” PwA1

Participation in the CPS was described as relaxed and PwA7 noted the conversations “were easy to take part in”. The students’ attitudes and actions in facilitating that ease of access, as well their engaging manner, was highlighted and praised.

“I suppose the … the students, well the girls. They’re was so nice, they’re very nice, but ehm, the new ones … ehm … there was very … ehm … very … ehm … young and … fun, fun.” PwA3

PwA6 identified that in taking part in the CPS he takes on a benefactor role, in response to the support and perceived benefits he received from speech and language therapy in the past, noting “I give back to them” and in doing so paying it forward to the next generation of SLTs.

The next theme, The Power of Conversation, explored how participating in conversations as a means of engaging in social interactions, whether online or face to face, is a powerful and empowering activity. Although challenges are present for PwA, they identified positive benefits from the online social interaction with students.

“So I would talk, and they would talk and we’d both be chatting … it was just unreal that’s all I can say it was brilliant. It was totally different. Yeah” PwA2

The nature of conversations varied and some PwA took the opportunity to introduce students to new hobbies, interests and concepts. Two introduced students to new films and film genres and one identified how talking about these topics prompted him to action, re-watching some of his favourite films following the conversations.

In the final theme, Reflection, Appraisal and Looking Forward, the PwA described their own communication difficulties as well as the impact of their communication difficulties on their conversations. They also reflected on perceived improvements following participation in the CPS.

“I was better than I ever had like this … this is the best I have ever been” PwA2

Two of the PwA discussed how they prepared for the weekly conversations, thinking about conversation topics before the scheduled session. A third PwA suggested the students could provide a presentation each week to recap on the topics discussed the previous week, while another identified that the student were well-prepared each week.

Public health restrictions associated with the COVID-19 pandemic reduced opportunities for social contacts and the CPS provided a welcome opportunity to meet other people outside their immediate family circle, as PwA6 reported:

“Ehm … OK … . eh … being in the pandemic, OK? Eh nice, to talk to someone … other than my family” PwA6

However, the reduced social contact that was promoted by public health guidance during the CPS had an impact not only on reducing the number of social interactions but also reducing topics of conversations. When asked what he liked least about the online CPS, PwA4 laughed and replied “there’s nothing to talk about”. The challenge to find new topics of conversations was also noted by other PwA and students.

Feasibility of the online CPS - a summary overview

The fully online delivery of the CPS is a suitable format for a CPS but a number of issues were highlighted that require further consideration. A summary of each feasibility question is presented in . In particular, additional online support and training was delivered in order to assist set up and familiarisation with the online platform prior to the CPS. This necessitated additional resources from the university practice education team which is not required for the implementation of the face-to-face format. In addition, there were some technology-related issues including the need for access to internet-enabled devices and reduced choice of communication ramps in the online format that impacted the practicality of and adaptability to the online format. In terms of integration with existing university structures, the online CPS was easily incorporated into the student practice education curriculum and the semester timetable. It was also reported as convenient and easily scheduled into the CPS partners’ daily routines. Finally, in terms of acceptability, all the PwA and the majority of students were satisfied that the online delivery was a suitable format for the CPS. However, the students perceived that a face-to-face CPS format would be better than online and it must be noted that attrition among the participants with acquired communication disabilities may warrant further investigation in terms of acceptability.

Table 7 Feasibility of an Online CPS

Discussion

This case study explored the feasibility and participants’ experiences of a CPS that was rapidly adapted to an online format in response to the public health restrictions during the COVID-19 crisis. Overall, the online format was feasible in terms of delivering effective online education sessions to train students to support online conversations, thus reflecting the success of other online CPT programmes for health professionals (Cameron et al., Citation2019) and students (Finch et al., Citation2020). The telepractice format was also feasible for supporting CPS partners and their families to use an online platform with remote assistance only to engage in the CPS. However, the format may not be suitable for and/or acceptable to everyone, as observed by the small but notable attrition among potential CPS partners at each phase during the preparation and commencement of the CPS. In addition, although the students engaged only in an online experience, many expressed a preference for a face-to-face CPS, believing this mode of communication to be more appropriate.

Both students and PwA considered the CPS to be a valuable learning experience. The PwA agreed it was important for students to experience conversations with people with communication disabilities in their programmes of study, a finding also noted in the study from Lee et al. (Citation2020). The online CPS provided an opportunity for effective communication and helped to reduce social exclusion. These benefits have also been noted in face-to-face CPS formats (McMenamin et al., Citation2015a; McVicker et al., Citation2009). The PwA repeatedly praised the students, highlighting the natural, enjoyable nature of conversations. Some PwA reflected on their own communication skills and identified positive changes, others valued the opportunity to chat with people outside their family during the public health restrictions. It is noteworthy that participating in CPT and student mentoring can have a positive impact for people with aphasia helping to increased confidence (Cameron et al., Citation2018) and improved quality of life (Purves et al., Citation2013). In addition, engaging in interactions with CPS partners who have a lived experience of communication disability can provide students with a better understanding of the impact of aphasia (Lee et al., Citation2020; Purves et al., Citation2013). The students in our study felt better prepared for future conversations and clinical placements following the CPS, mirroring the experience of other allied health students following CPT (Cameron et al., Citation2018). Although, the students in our study perceived the experience was positive in general, some questioned the mode and identified that some communication ramps were not readily transferable to an online format. Indeed, modifying clinical tasks from traditional pen and paper tasks to an online format has also been highlighted as a challenge for students during the rapid transition to telepractice placements in response to COVID-19 (Kearns et al., Citation2021a).

All PwA interviewed in our study reported that telepractice was suitable for online conversations with students. This compliments the findings from a recent review which described how people with aphasia reported positive feedback when engaging in aphasia rehabilitation delivered by digital technologies, however variation among personal perspectives was noted (Kearns et al., Citation2021b). Also, it is important to note that the factors that motivate an individual to engage in an online CPS may differ to those factors that influence engagement in online rehabilitation. Lee et al. (Citation2020) noted that while telepractice may be considered suitable for online conversations by PwA, experiencing technology difficulties can be associated with more negative perceptions (Lee et al., Citation2020). The initial training and preparation clinic in our feasibility study provided an opportunity for PwA to become familiar with the online platform and trouble shoot issues that emerged. It’s likely that this support was an important factor that enabled the online conversations in the CPS, however this was not specifically identified by any participants during the interviews. The factors that influence individuals’ decisions to accept and use digital technologies are multifaceted as outlined by a variety of theoretical models that explore the phenomenon (Davis et al., Citation1989; Rogers, Citation2010; Venkatesh et al., Citation2003). The attrition rate of participants with acquired communication disabilities in our study may reflect dissatisfaction with the online format or alternatively this may reflect difficulties with internet access and usage. A variety of barriers and facilitators to internet use may be present for individuals with aphasia (Menger et al., Citation2015). There is likely to be significant variation in individuals’ needs with respect to internet use and a multi-pronged approach to support is indicated (Menger et al., Citation2020). The COVID-19 crisis necessitated a move to online communications for many activities and the individualised support in the training and preparation clinics in our study may have enabled PwA and families to participate in the online CPS.

The use of digital technologies to facilitate online conversations was perceived by students and PwA in our study, as both beneficial and challenging. The students were less positive about telepractice as a means to support online conversations compared to the PwA. However, they considered the format to be acceptable within the current public health context. There were some technical issues that required problem solving, although no sessions were abandoned due to these issues and the students worked to resolve these issues either through the platform or over the phone. To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first study that has explored an online CPS with no face-to-face support and demonstrates that this format is feasible with support provided only online and without face-to-face contact.

The convenience of the online conversations, which supported physical distancing but provided social connections (Ellis & Jacobs, Citation2021) in line with public health guidance, was a clear benefit for students and PwA. Both groups also identified that digital technologies have become part of everyday life and can therefore provide alternative and accessible options for conversations. The students expressed a wish to have face-to-face contact, this was not reflected in the comments from the PwA. However, it’s likely that the views of PwA in this feasibility study represent a group of individuals with positive perspectives on digital technologies. In studies of computer-delivered aphasia rehabilitation, some participants have expressed a preference for a combination of face-to-face and computer-delivered intervention (Palmer et al., Citation2013; Wade et al., Citation2003). While many students and PwA value the potential that digital technologies can provide for online conversations (Finch et al., Citation2020; Lee et al., Citation2020), a combination of face-to-face and online conversations may be a worthwhile option going forward. Future research exploring a hybrid approach, combining the benefits and convenience of the online format alongside the traditional face-to-face interactions, as a means of delivering a CPS for student education and participant engagement is indicated.

Limitations

This study explored five feasibility elements (Bowen et al., Citation2009) of an online CPS. The efficacy of this mode of delivery was not examined and the mode was not compared against face-to-face delivery. However, the CPS in this feasibility study was delivered within a practice education module for SLT students and the learning outcomes were achieved through the delivery of the online format. The students were not required to answer all questions in the post-CPS questionnaire, and could skip to the next question with responding. Therefore the response rate is variable across questions and this represents a limitation of this study. While the majority of individuals with acquired communication disabilities who took part in the CPS presented with aphasia post stroke or traumatic brain injury, the CPS partners were a heterogeneous group. The experiences of the PwA who participated in the interviews may not represent the experiences of all who CPS partners who participated in this online CPS.

Conclusion

The CPS in this feasibility study moved online in response to the public health guidance resulting from the COVID-19 crisis. The delivery of a solely online format for a CPS is feasible with assistance delivered remotely and no face-to-face contact. It is important to note that this format may not be suitable for all individuals with acquired communication disabilities and many students indicated a preference for face-to-face interactions. However, taking into account the public health guidance at the time of delivery of the scheme, this online CPS provided a timely opportunity for students to practice supported communication skills and was perceived to be important for student training and communication skills development.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the people with acquired communication disabilities, their families, and the SLT students who participated in this online CPS.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Bowen, D. J., Kreuter, M., Spring, B., Cofta-Woerpel, L., Linnan, L., Weiner, D., Bakken, S., Kaplan, C. P., Squiers, L., Fabrizio, C., & Fernandez, M. (2009). How We Design Feasibility Studies. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 36(5), 452–457. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2009.02.002

- Cameron, A., Hudson, K., Finch, E., Fleming, J., Lethlean, J., & McPhail, S. (2018). ‘I’ve got to get something out of it. And so do they’: experiences of people with aphasia and university students participating in a communication partner training programme for healthcare professionals. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 53(5), 919–928. https://doi.org/10.1111/1460-6984.12402

- Cameron, A., McPhail, S. M., Hudson, K., Fleming, J., Lethlean, J., & Finch, E. (2015). Increasing the confidence and knowledge of occupational therapy and physiotherapy students when communicating with people with aphasia: A pre–post intervention study. Speech, Language and Hearing, 18(3), 148–155. https://doi.org/10.1179/2050572814y.0000000062

- Cameron, A., McPhail, S., Hudson, K., Fleming, J., Lethlean, J., & Finch, E. (2019). Telepractice communication partner training for health professionals: A randomised trial. Journal of Communication Disorders, 81, 105914. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcomdis.2019.105914

- Cruice, M., Blom Johansson, M., Isaksen, J., & Horton, S. (2018). Reporting interventions in communication partner training: a critical review and narrative synthesis of the literature. Aphasiology, 32(10), 1135–1166. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038.2018.1482406

- Cruice, M., Woolf, C., Caute, A., Monnelly, K., Wilson, S., & Marshall, J. (2020). Preliminary outcomes from a pilot study of personalised online supported conversation for participation intervention for people with Aphasia. Aphasiology, 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038.2020.1795076

- Davis, F. D., Bagozzi, R. P., & Warshaw, P. R. (1989). User Acceptance of Computer Technology: A Comparison of Two Theoretical Models. Manage. Sci., 35(8), 982–1003.

- Ellis, C., & Jacobs, M. (2021). The Cost of Social Distancing for Persons With Aphasia During COVID-19: A Need for Social Connectedness. Journal of Patient Experience, 8, 237437352110083. https://doi.org/10.1177/23743735211008311

- Elo, S., & Kyngäs, H. (2008). The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 62(1), 107–115. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x

- Finch, E., Cameron, A., Fleming, J., Lethlean, J., Hudson, K., & McPhail, S. (2017). Does communication partner training improve the conversation skills of speech-language pathology students when interacting with people with aphasia? Journal of Communication Disorders, 68, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcomdis.2017.05.004

- Finch, E., Lethlean, J., Rose, T., Fleming, J., Theodoros, D., Cameron, A., Coleman, A., Copland, D., & McPhail, S. M. (2020). Conversations between people with aphasia and speech pathology students via telepractice: A Phase II feasibility study. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 55(1), 43–58. https://doi.org/10.1111/1460-6984.12501

- Graneheim, U. H., & Lundman, B. (2004). Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Education Today, 24(2), 105–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001

- Hoepner, J. K., & Sather, T. W. (2020). Teaching and Mentoring Students in the Life Participation Approach to Aphasia Service Delivery Perspective. Perspectives of the ASHA Special Interest Groups, 5(2), 397–413. https://doi.org/10.1044/2019_PERSP-19-00159

- Jagoe, C., & Roseingrave, R. (2011). “If This is What I’m ‘Meant to be’ … ”: The Journeys of Students Participating in a Conversation Partner Scheme for People with Aphasia. Journal of Academic Ethics, 9(2), 127–148. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10805-011-9140-5

- Kagan, A. (1998). Supported conversation for adults with aphasia: methods and resources for training conversation partners. Aphasiology, 12(9), 816–830. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687039808249575

- Kearns, Á., Gallagher, A., & Cronin, J. (2021a). Quality in the Time of Chaos: Reflections From Teaching, Learning and Practice. Perspectives of the ASHA Special Interest Groups, 6(5), 1310–1314. https://doi.org/10.1044/2021_persp-21-00095

- Kearns, Á., Kelly, H., & Pitt, I. (2020). Rating experience of ICT-delivered aphasia rehabilitation: co-design of a feedback questionnaire. Aphasiology, 34(3), 319–342. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038.2019.1649913

- Kearns, A., Kelly, H., & Pitt, I. (2021b). Self-reported feedback in ICT-delivered aphasia rehabilitation: a literature review. Disabil Rehabil, 43(9), 1193–1207. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2019.1655803

- Kennelly, B., O’Callaghan, M., Coughlan, D., Cullinan, J., Doherty, E., Glynn, L., Moloney, E., & Queally, M. (2020). The COVID-19 pandemic in Ireland: An overview of the health service and economic policy response. Health Policy and Technology, 9(4), 419–429. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hlpt.2020.08.021

- Lee, J. J., Finch, E., & Rose, T. (2020). Exploring the outcomes and perceptions of people with aphasia who conversed with speech pathology students via telepractice: a pilot study. Speech, Language and Hearing, 23(2), 110–120. https://doi.org/10.1080/2050571x.2019.1702241

- Legg, C., Young, L., & Bryer, A. (2005). Training sixth-year medical students in obtaining case-history information from adults with aphasia. Aphasiology, 19(6), 559–575. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687030544000029

- Lock, S., Wilkinson, R., Bryan, K., Maxim, J., Edmundson, A., Bruce, C., & Moir, D. (2001). Supporting Partners of People with Aphasia in Relationships and Conversation (SPPARC). International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 36 (s1),25–30. https://doi.org/10.3109/13682820109177853

- McLellan, E., MacQueen, K. M., & Neidig, J. L. (2003). Beyond the qualitative interview: Data preparation and transcription. Field methods, 15(1), 63–84.

- McMenamin, R., Tierney, E., & Mac Farlane, A. (2015a). Addressing the long-term impacts of aphasia: how far does the Conversation Partner Programme go? Aphasiology, 29(8), 889–913. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038.2015.1004155

- McMenamin, R., Tierney, E., & Mac Farlane, A. (2015b). “Who decides what criteria are important to consider in exploring the outcomes of conversation approaches? A participatory health research study”. Aphasiology, 29(8), 914–938. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038.2015.1006564

- McVicker, S. (2007). The conversation partner toolkit. London, UK: Connect.

- McVicker, S., Parr, S., Pound, C., & Duchan, J. (2009). The Communication Partner Scheme: A project to develop long‐term, low‐cost access to conversation for people living with aphasia. Aphasiology, 23(1), 52–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687030701688783

- Menger, F., Morris, J., & Salis, C. (2015). Aphasia in an Internet age: wider perspectives on digital inclusion. Aphasiology, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038.2015.1109050

- Menger, F., Morris, J., & Salis, C. (2020). The impact of aphasia on Internet and technology use. Disability and Rehabilitation, 42(21), 2986–2996. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2019.1580320

- Palmer, R., Enderby, P., & Paterson, G. (2013). Using computers to enable self-management of aphasia therapy exercises for word finding: the patient and carer perspective. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 48(5), 508–521. https://doi.org/10.1111/1460-6984.12024

- Power, E., Falkenberg, K., Barnes, S., Elbourn, E., Attard, M., & Togher, L. (2020). A pilot randomized controlled trial comparing online versus face‐to‐face delivery of an aphasia communication partner training program for student healthcare professionals. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 55(6), 852–866. https://doi.org/10.1111/1460-6984.12556

- Purves, B. A., Petersen, J., & Puurveen, G. (2013). An Aphasia Mentoring Program: Perspectives of Speech-Language Pathology Students and of Mentors With Aphasia. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 22(2), S370–S379. https://doi.org/10.1044/1058-0360(2013/12-0071)

- Rogers, E. M. (2010). Diffusion of innovations. Simon and Schuster.

- Roper, A., Marshall, J., & Wilson, S. M. (2014). Assessing technology use in aphasia Proceedings of the 16th international ACM SIGACCESS conference on Computers & accessibility, Rochester, New York, USA. https://doi.org/10.1145/2661334.2661397

- Rowley, J. (2002). Using case studies in research. Management research news.

- Simmons-Mackie, N., Raymer, A., Armstrong, E., Holland, A., & Cherney, L. R. (2010). Communication Partner Training in Aphasia: A Systematic Review. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation, 91(12), 1814–1837. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2010.08.026

- Simmons-Mackie, N., Raymer, A., & Cherney, L. R. (2016). Communication Partner Training in Aphasia: An Updated Systematic Review. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation, 97(12), 2202–2221.e2208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2016.03.023

- Thomson, J., Gee, M., Sage, K., & Walker, T. (2018). What ‘form’ does informal assessment take? A scoping review of the informal assessment literature for aphasia. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 53(4), 659–674. https://doi.org/10.1111/1460-6984.12382

- Venkatesh, V., Morris, M. G., Davis, G. B., & Davis, F. D. (2003). User Acceptance of Information Technology: Toward a Unified View. MIS Quarterly, 27(3), 425–478. https://doi.org/10.2307/30036540

- Wade, J., Mortley, J., & Enderby, P. (2003). Talk about IT: Views of people with aphasia and their partners on receiving remotely monitored computer‐based word finding therapy. Aphasiology, 17(11), 1031–1056. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687030344000373

- Welsh, J., & Szabo, G. (2011). Teaching Nursing Assistant Students about Aphasia and Communication. Seminars in Speech and Language, 32(03), 243–255. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0031-1286178