ABSTRACT

Background

Despite growing evidence supporting the clinical efficacy of Intensive Comprehensive Aphasia Programs (ICAPs), there are implementation challenges that may prevent widespread adoption of ICAPs by healthcare services. To address these barriers, a tailored implementation intervention was developed to facilitate the delivery of a modified-ICAP called the Comprehensive, High-dose Aphasia Treatment (CHAT) program within the Australian healthcare context.

Aims

1) To evaluate the feasibility, acceptability and potential effectiveness of a tailored implementation intervention to support the delivery of CHAT within a clinical service. 2) To evaluate the feasibility, acceptability and the potential effectiveness of delivering CHAT with respect to clinician and patient outcome measures.

Methods and Procedure

This Phase 1 feasibility study utilised a mixed-methods hybrid Type III implementation effectiveness design. A single health service was recruited for the implementation trial and two speech pathologists received training and resources to support the delivery of CHAT. Four adults with chronic post-stroke aphasia were recruited to participate in the eight-week CHAT program. Qualitative data, obtained through in-depth interviews, were used to explore speech pathologists’ perspectives of the tailored implementation strategy and to identify the potential barriers and facilitators to delivering CHAT. Furthermore, quantitative data evaluated the feasibility (i.e., dose of intervention), acceptability (i.e., satisfaction ratings) and potential effectiveness (i.e., clinical outcomes) of the CHAT program.

Outcomes and Results

Speech pathologists perceived CHAT to be feasible, acceptable, and potentially effective to implement into the healthcare service. Improvements across measures of patients’ language impairment, functional communication and quality of life post-CHAT were observed. Reported facilitators to implementation included the provision of support and access to information and resources, while barriers included time constraints, scheduling issues and clinician fatigue.

Conclusions

This is the first study to report the successful clinical implementation of a modified-ICAP into a health service. Findings from this study will be used to inform future adoption of the ICAP model into rehabilitation services.

Introduction

Due to the far-reaching and devastating impact of aphasia on the individual and their broader social network (Everett et al., Citation2021; Hilari, Citation2011; Lam & Wodchis, Citation2010), multifactorial and effective methods of treatment are required (Brady et al., Citation2016; Rose et al., Citation2021). Intensive, Comprehensive Aphasia Programs (ICAPs) are a novel service delivery model incorporating principles of neuroplasticity to systematically target language impairment and activity and participation restrictions across International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) domains (Rose et al., Citation2013; World Health Organization [WHO], Citation2001). The ICAP model provides high dose or intensive therapy (minimum of 3 hours therapy per day, 5 days per week for 2 weeks), utilises a variety of treatment formats (e.g., individual therapy, group therapy) and incorporates patient and family education in a cohort design (Rose et al., Citation2013). A modified ICAP (mICAP) meets all but any one of the defining ICAP elements, for example a mICAP may have a modification to the intensity or cohort design elements, but not both (Rose et al., Citation2021, p. 3). There is growing evidence supporting the clinical efficacy of ICAPs, with research demonstrating significant improvements in participants’ overall aphasia severity, functional communication and non-linguistic based measures, such as psychosocial wellbeing and overall quality of life (Babbitt et al., Citation2015; Dignam et al., Citation2015; Griffin-Musick et al., Citation2020; Hoover et al., Citation2017; Rose et al., Citation2013).

To date, few studies have investigated the clinical effectiveness of an ICAP when delivered as part of a mainstream healthcare service (Babbitt et al., Citation2015; Brindley et al., Citation1989; Leff et al., Citation2021; Winans-Mitrik et al., Citation2014). Most recently, Leff and colleagues (Citation2021) evaluated the effectiveness of The Queen Square Intensive Comprehensive Aphasia Service (ICAP) when delivered within the United Kingdom’s National Health Service (NHS). In this study, 46 participants with chronic aphasia received 7 hours aphasia rehabilitation per day, 5 days per week for 3 weeks. Significant improvements were observed in participants’ language impairment, measured using four language domains (auditory comprehension, speaking, reading, writing) of the Comprehensive Aphasia Test (CAT, Swinburn et al., Citation2004) and functional communication on the Communicative Effectiveness Index (CETI, Lomas et al., Citation1989). These studies provide promising evidence for the clinical effectiveness of an ICAP when delivered within a healthcare service (Babbitt et al., Citation2015; Leff et al., Citation2021; Winans-Mitrik et al., Citation2014). However, to date this research has predominantly reported patient-level clinical outcomes and has not explored the process of implementing the ICAP into the healthcare service. Several studies have highlighted barriers and sustainability issues with ICAP implementation, described below, and as such, in order to support the translation of research evidence for ICAPs into clinical practice, it is important to evaluate implementation processes.

Barriers to implementing complete ICAPs, or elements of ICAPs such as intensive and comprehensive services, have been identified in three recent studies (Monnelly et al., Citation2023; Shrubsole et al., Citation2022; Trebilcock et al., Citation2019) informed by the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF, Cane et al., Citation2012; Michie et al., Citation2005). The TDF is a framework of 14 domains that relate to theory-informed determinants of behaviour-change across individual, organisational, and social levels (Cane et al., Citation2012; Michie et al., Citation2005). The TDF domain ‘environmental context and resources’ (including factors such as time and staffing) was identified as a barrier in all studies, with other common factors influencing practice including clinician ‘knowledge’ and ‘skills’. The domains ‘beliefs about consequences’ (including clinicians’ beliefs about ICAP benefits) and ‘social/professional role and identity’ (including clinicians’ perceptions that ICAPs are compatible with their role) were found to influence practice in both Trebilcock et al.’s (Citation2019) international focus group study and Monnelly et al.’s (Citation2023) survey of 227 UK speech pathologists. However, the ‘beliefs about capabilities’ domain (including factors such as clinician confidence) was identified as a unique barrier to implementing a specific ICAP (Aphasia LIFT - see Dignam et al., Citation2015; Rodriguez et al., Citation2013) into metropolitan healthcare services in Shrubsole et al.’s (Citation2022) qualitative study with Australian speech pathologists, highlighting the importance of understanding the intended implementation context. In addition, Monnelly et al. found that the ‘emotion’ domain (including factors such as clinician enjoyment) was a facilitator for implementing comprehensive services, but that negative emotions such as stress were barriers to implementing intensive services. Two additional barriers not based on the TDF were identified by Shrubsole and colleagues, including the structure and perceived inflexibility of ‘the ICAP innovation’, and ‘patient factors’ such as fatigue and other therapy priorities. Similarly, Monnelly and colleagues identified patient factors such as fatigue and cognitive impairment as concerns for program candidacy. A finding common to all three studies was speech pathologists’ lack of confidence that an ICAP could feasibly be delivered within existing services. This was particularly apparent in Monnelly et al.’s (Citation2023) survey, where only 16.5% responded that their service could be reconfigured to deliver an ICAP. Furthermore, international survey data indicated that several ICAPs ceased to operate between 2013 and 2021, highlighting issues of sustainability and funding challenges (Rose et al., Citation2021).

There is a need to address these barriers to facilitate implementation of ICAPs into clinical services and/or to identify modifications that would enable the successful adoption of ICAPs through applying implementation science methodologies. The field of implementation science promotes the use of strategies to increase evidence uptake, known as implementation interventions, to facilitate behaviour change in clinicians and improve practice (Baker et al., Citation2015; Eccles & Mittman, Citation2006). Implementation interventions developed and tailored to address context-specific barriers are known to be more effective than non-tailored interventions or passive guideline dissemination (Baker et al., Citation2015). Additionally, the use of theory in implementation science and adoption of theory informed frameworks, such as the TDF (Cane et al., Citation2012), is important to inform the development of implementation interventions for clinical settings, explain the drivers of change, and enable replicable methodology (French et al., Citation2012; Phillips et al., Citation2015). An implementation intervention designed to improve the intensity and comprehensiveness of aphasia services was shown to be feasible and acceptable to speech pathologists, with the potential to improve practice (Trebilcock et al., Citation2022). However, the participating site in the Trebicock et al study did not implement a complete ICAP, focussing instead on improving individual ICAP components such as group therapy. In addition, although ICAPs have been successfully implemented into healthcare service models, the process of successful implementation has not been previously reported, making it difficult to replicate successes. Therefore, it is currently unknown what elements of a theoretically informed implementation intervention are required to successfully implement a complete ICAP or mICAP into an existing clinical service.

The CHAT program and the implementation intervention

While some adoption of ICAPs has been reported (Rose et al., Citation2021), there are relatively few ICAPS and mICAPS offered globally. Within Australia, aphasia rehabilitation services are limited (Rose et al., Citation2014; Verna et al., Citation2009) and there is an evidence-practice gap between the dose or intensity of intervention recommended in the research literature and what occurs in clinical practice (Shrubsole et al., Citation2022; Shrubsole et al., Citation2018). To increase access to high-dose, evidence-based aphasia therapy, The University of Queensland developed a mICAP, the Comprehensive, High-dose Aphasia Treatment (CHAT) program. The CHAT program is comprised of 50 hours of evidence-based, goal-directed aphasia therapy, delivered 2-3 hours per day, 3 days per week over an 8-week schedule. CHAT was developed for service implementation and is based on the Aphasia Language, Impairment and Functional Therapy (LIFT) program (Rodriguez et al., Citation2013) that systematically targets ICF domains through a combination of individual, group, and computer-based therapy. Phase II efficacy studies have provided support for the clinical efficacy of Aphasia LIFT with positive participant outcomes reported for measures of language impairment, functional communication and communication-related quality of life (Dignam et al., Citation2015; Rodriguez et al., Citation2013). The LIFT program was delivered in a research context and predominantly included evidence-based therapies for word retrieval delivered across a range of treatment formats. In order to address the heterogenous clinical needs of people with aphasia, the CHAT program was expanded to incorporate a broad range of evidence-based aphasia therapies, across language domains and communication modalities. For a detailed description of the CHAT protocol refer to the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR checklist, Hoffmann et al., Citation2014) in Supplemental 1.

In order to facilitate the implementation of CHAT into clinical services within the Australian metropolitan healthcare context, a theory-informed implementation intervention was developed (Shrubsole et al., Citation2022). The development of this implementation intervention involved a mapping process identifying suitable Behaviour Change Techniques (Michie et al., Citation2014; Michie et al., Citation2013) and implementation strategies (Waltz et al., Citation2019) tailored to address identified barriers. The resultant implementation intervention included six components described in more detail elsewhere (Shrubsole et al., Citation2022): (i) Executive, leadership and stakeholder support, (ii) Allocation of clinical staff, (iii) Interactive education and training program, (iv) Resource procurement and provision, (v) Ongoing implementation support, and (vi) Consumer engagement and promotion. However, the implementation intervention is yet to be evaluated, and thus the feasibility and potential impact on delivering CHAT within an existing healthcare service is unknown. Moreover, no studies have investigated the patient outcomes of CHAT within an existing healthcare service. Therefore, this study aimed to:

Evaluate the feasibility, acceptability and potential effectiveness of a tailored implementation intervention to support the delivery of the CHAT program within a clinical service.

Evaluate the feasibility, acceptability and the potential effectiveness of delivering the CHAT program in terms of clinician and patient outcomes.

Methods

Design

This Phase 1 feasibility study (Eldridge et al., Citation2016) utilised a mixed-methods hybrid Type III implementation effectiveness design (Curran et al., Citation2012). This design was selected to enable feasibility testing of both the implementation intervention and the CHAT program prior to full testing, as recommended by the UK Medical Research Council (Craig et al., Citation2013). For this study, feasibility was the practicality of receiving the implementation intervention and implementing CHAT, as perceived by the participants and indicated by recruitment retention and treatment fidelity (dose delivered). Acceptability referred to the participants’ satisfaction with the implementation intervention and CHAT program, and the perceived fit of the CHAT program within their service. Potential effectiveness related to the capacity of the implementation intervention to produce change as measured by quantitative outcome measures and participants’ perceptions.

Setting

This research project was a joint initiative between The University of Queensland and Metro North Hospital and Health Service located in Brisbane, Australia. The CHAT program was implemented at a single site, the Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital Geriatric Assessment and Rehabilitation Unit, which is a public in-patient and out-patient rehabilitation facility. Usual care for aphasia management at this site typically includes comprehensive, goal-directed aphasia therapy incorporating impairment and functional treatment approaches, computer-based therapy and group therapy models (Shrubsole et al., Citation2022). Out-patient therapy is typically provided at an intensity of 1 to 2 hours per week (face to face) up to a maximum of 3 hours per week, supported by a targeted home exercise program.

The study is reported in accordance with the Standards for Reporting Implementation Studies (StaRI) (Pinnock et al., Citation2017, Supplemental 2). Ethical clearance was obtained from the relevant ethics committees and all participants provided informed written consent prior to participation. The eight-week comprehensive, high-dose aphasia therapy (CHAT) program was implemented between September and November 2020.

Participants

Two participant groups were involved in the study: speech pathologists (n=3) and patients (n=4).

Speech pathologists

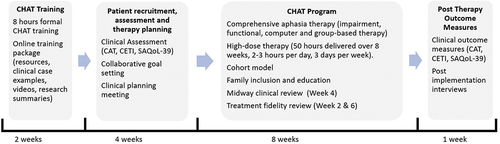

Two senior speech pathologists (Bachelor of Speech Pathology or equivalent, clinical experience = 15 years each) performed the roles of the CHAT speech pathologists for a duration of 14 weeks. One speech pathologist (SLP01) was employed on 0.6 full-time equivalent basis and the second speech pathologist (SLP02) on a full-time basis. Across these 14 weeks the CHAT speech pathologists completed two weeks of training, four weeks of patient screening, assessment and therapy preparation, and eight weeks dedicated to the delivery of the CHAT program (See for project timeline). In addition, one advanced speech pathologist (SLP03, clinical experience = 23 years) was responsible for overseeing the clinical rehabilitation service, including staff recruitment, provision of clinical supervision and managing resources. The CHAT speech pathologists were experienced in aphasia rehabilitation but had no prior training or experience in delivering the CHAT program.

Patients

Four adults (3 Male, 1 Female; mean age = 44.3 years, range 26 to 62 years) with chronic, post-stroke aphasia resulting from left hemisphere stroke were recruited to participate in CHAT. Participant demographics are reported in in accordance with the DESCRIBE checklist (Wallace et al., Citation2022). All patients were a minimum of 1-month post onset (mean 8.5 months, range 4 to 12 months) and were native English speakers prior to their stroke. Although both in-patients and out-patients were eligible for participation, all four patients were receiving out-patient therapy at the time of recruitment. Patients with comorbidities that would prevent participation in rehabilitation (e.g., progressive neurological disorder), determined in consultation with the treating multidisciplinary team, were excluded from the study.

Table 1. Patient Demographic Information.

Procedure for Development and Delivery of the Implementation Intervention

Five components of the previously-developed implementation intervention (Shrubsole et al., Citation2022) were operationalised for the pilot site by the research team, led by authors JD and DC, with input from the participating speech pathology department manager. Further detail regarding the process for developing these components and the associated behaviour change techniques can be found elsewhere (Shrubsole et al., Citation2022). The implementation intervention was delivered by two experienced researchers with extensive knowledge of the CHAT program and included the following core components:

Executive, leadership and stakeholder support: Prior to implementation, extensive consultation with service managers, site speech pathologists and the multidisciplinary team was undertaken. Support from executive and leadership was obtained, including a formal agreement between The University of Queensland and Metro North Hospital and Health Service to deliver and evaluate CHAT and its implementation.

Allocation of clinical staff: Dedicated speech pathology staff (1.6 full time equivalent) were recruited for 14 weeks to implement CHAT into the clinical service. CHAT speech pathologists were backfilled from their usual Queensland Health appointment for the duration of the study and their positions were funded by the Queensland Aphasia Research Centre.

Interactive education and training program: During the two weeks of training, the CHAT speech pathologists received 8 hours of formal CHAT training and access to a comprehensive online training package that included the CHAT treatment protocol, summaries and videos of treatment procedures and links to the research literature.

Resource procurement and provision: Physical resources, such as laptops, internet connectivity, computer therapy programs and clinical resources, were provided to the CHAT speech pathologist by the research team for the duration of the study.

Ongoing implementation support (facilitation, enablement, and feedback): The research team provided the CHAT speech pathologists with ongoing mentoring and support, including joint clinical planning for CHAT patients, mid-way clinical review, and weekly debriefing sessions. To promote treatment fidelity, all CHAT assessments and a sample of therapy sessions (1 session per therapy type per week) were video recorded. A sample of therapy videos were selected by the CHAT speech pathologists and the research team and jointly reviewed during two fidelity sessions to enable performance monitoring and to support the provision of feedback.

Procedure for delivering the CHAT Program

Baseline Assessment

A clinical assessment battery was conducted by CHAT speech pathologists to evaluate patients’ language impairment (CAT, Swinburn et al., Citation2004), functional communication (CETI, Lomas et al., Citation1989) and communication-related quality of life (Stroke and Aphasia Quality of Life Scale-39 (SAQoL-39), Hilari et al., Citation2003) at baseline. Further clinical assessment was conducted at the discretion of the CHAT speech pathologists to inform treatment planning.

Goal Setting

Consistent with best-practice, a multi-stage, collaborative goal-setting process was undertaken with people with aphasia and their family to identify and prioritise personally meaningful communication goals for CHAT (Hersh et al., Citation2012; Scobbie et al., Citation2011; CitationStroke Foundation., 2021). Patients’ goals were revised to ensure they were specific, measurable and achievable within the CHAT treatment period and were used to inform treatment planning (Hersh et al., Citation2012).

Clinical Planning

A collaborative clinical planning session involving the CHAT speech pathologists, clinical supervisors, the research team, an implementation scientist and a technology expert was conducted prior to CHAT to support implementation. From a research perspective, the aim of the clinical planning meeting was to promote CHAT treatment fidelity. From a clinical perspective, the aims of this session were to identify further assessment required to inform intervention; review and calibrate patients’ communication goals in the context of their clinical history and assessment results; collaboratively develop evidence-based action plans to address patients’ communication goals (Scobbie et al., Citation2011); identify personally salient therapy materials (e.g., treatment stimuli and set-sizes), and identify any further clinical considerations (e.g., referrals to the multidisciplinary team, discharge planning). Approximately 1 to 2 hours was allocated for discussion of each participant during the clinical planning meeting.

Therapy

The CHAT program includes 50 hours of evidence-based aphasia therapy, including 14 hours each of impairment, functional and computer-based intervention and eight hours of psychosocial group therapy and education, delivered over 8 weeks. Therapy was personalised to address participants’ communication goals across ICF domains and patients’ progress was reviewed iteratively during the program, with therapy plans updated as required. Patients’ individualised therapy plans for CHAT are detailed in . Patients’ family members and/or significant others were encouraged to attend and participate in CHAT therapy sessions, as able.

Table 2. Patients’ communication therapy goals and individualised therapy plan for CHAT.

Both impairment therapy and functional therapy were delivered by the trained CHAT speech pathologists on an individual basis. Computer therapy was delivered by either the speech pathologists or a trained allied health assistant, and group therapy was facilitated by the CHAT speech pathologists.

Data collection and analysis

As this was a pilot study with a focus on feasibility, acceptability and potential effectiveness, there was no primary outcome measure. Multiple outcome measures were used, described below, in order to investigate the complex implementation outcomes and processes, with the quantitative and qualitative findings integrated as appropriate to meet the study aims (Fetters et al., Citation2013). The study outcome measures are presented in .

Table 3. Outcome measures to evaluate the feasibility, acceptability and potential effectiveness of the implementation intervention and the CHAT program.

Clinician-level outcome measures and analyses

Semi-structured Interviews

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with CHAT speech pathologists and service managers to evaluate their post-implementation views and perspectives. These interviews were approximately 1 hour in length and conducted by a member of the research team (KS) with qualitative research experience who was not involved in delivering the implementation intervention. A topic guide informed the interviews, based on a previously-developed interview guide (Shrubsole et al., Citation2022). Interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim, then analysed using content analysis (Graneheim & Lundman, Citation2004). Two members of the research team jointly coded and analysed the first transcript to establish coding agreement, then coded the remaining transcripts separately and engaged in peer checking throughout. For each transcript, condensed meaning units were identified to establish facilitators and barriers influencing implementation. These condensed meaning units were then coded with reference to the concepts of feasibility, acceptability and potential effectiveness of the implementation intervention and delivering CHAT.

Behavioural Determinants Survey

A ‘behavioural determinants’ survey, based on the Theoretical Domains Framework (Cane et al., Citation2012) and informed by a validated survey (Huijg et al., Citation2014), was conducted with the CHAT speech pathologists at baseline and post-implementation. In this survey, speech pathologists responded to a series of 35 statements (1-3 statements per TDF domain), indicating their level of agreement on a 5-point Likert scale. Survey results were analysed using descriptive statistics to determine the areas of greatest change and identify whether the barriers targeted by the implementation intervention were addressed. A change score for each TDF domain was calculated by subtracting the average pre-CHAT domain score from the relevant average post-CHAT domain score. Larger change scores indicated greater change, with positive scores indicating improvement and negative scores indicating deterioration in specific domains.

Patient-level outcome measures and analyses

Recruitment Retention & Dose of Comprehensive Aphasia Therapy Received

A recruitment retention log was maintained throughout the study. In addition, detailed clinical progress notes and therapy hours were recorded by the CHAT speech pathologists for each patient across the eight-week program to evaluate patients’ ability to attend and complete the intensive, comprehensive therapy program. Dose of intervention was measured in therapy hours, and the total number of therapy hours delivered was divided by the total number of therapy hours intended (i.e. 50 hours) to obtain the percentage of intended therapy hours received by each patient.

Patient Satisfaction

An aphasia-friendly 34 item survey, developed by the research team, was conducted with participants with aphasia upon completion of CHAT, to evaluate their satisfaction and explore their perspectives with the service. A combination of response formats was used, including 5-point Likert scale (scored 0 to 5) and open-ended questions. Quantitative data were analysed using descriptive statistics and qualitative data, obtained from open ended questions, were analysed using content analysis (Graneheim & Lundman, Citation2004).

Clinical Outcomes

The clinical assessment battery was repeated post-therapy to evaluate changes in patients’ language impairment (CAT, Swinburn et al., Citation2004), functional communication (CETI, Lomas et al., Citation1989), and communication-related quality of life (SAQoL-39, Hilari et al., Citation2003). Assessments were administered by a research speech pathologist and were audio and video recorded and scored offline. Clinical outcome measures were analysed using descriptive statistics to examine the potential effectiveness of the CHAT program. Published test-retest reliability data were used to determine significant change in patients’ language impairment on the CAT subtests (p < .05, one-tailed) (Swinburn et al., Citation2004). Minimal Detectable Change (MDC90), defined as the minimal score change that falls outside measurement error with 90% confidence, was used to identify an individuals’ change on the CETI (>11.53) and the SAQoL-39 (>0.36) (Menahemi-Falkov et al., Citation2021).

Results

Results are reported in relation to the study aims below, with qualitative data integrated with findings from other outcome measures where appropriate.

Implementation intervention evaluation

Feasibility and acceptability of receiving the implementation intervention

Overall, the CHAT speech pathologists perceived the implementation intervention components as being feasible and acceptable, with some suggested improvements. In particular, the face-to-face format of the training was feasible with the allocation of clinical time for this purpose, however speech pathologists noted that face-to-face training would be difficult for a larger group of clinicians to be released from patient contact time. In addition, speech pathologists were satisfied with the training, highlighting the importance of receiving education about the CHAT components and including videos of patients and clinicians in real-life clinical contexts. Participant SLP02 valued these videos with “real patients and real clinicians” more than videos of “therapy approaches that had YouTube links … from America or had not real people (simulations)” and indicated a preference for including more authentic videos in future training. The speech pathologists were also satisfied with the interactive style of training that allowed them the opportunity to ask questions throughout. However, they felt that the amount of information about assessments and treatment approaches provided within the training and in the online package was overwhelming, particularly when they had not yet recruited patients and so didn’t know what treatment approaches were relevant. SLP01 explained that “it was a little bit overwhelming” and suggested that recruiting and assessing patients before learning about specific treatment approaches “would make it easier.” This was reinforced by SLP02, who stated:

I think it was no good knowing all the therapy approaches available when you didn’t know who you had. Like if you knew who you had and … what impairments they had, you could then read up more about each technique better. Whereas we were learning and reading about everything we could that was on the RDM [online training package], but we didn’t know what the patient had to begin with and what their goals were, so it was kind of … it was overwhelming …

The support provided by the research team was generally seen as feasible and acceptable, and clinicians valued researchers’ input into clinical planning, stating that it was “important to have experience along the way (SLP02)”. However, clinicians reported it was not feasible to videorecord the treatment sessions for fidelity purposes due to the time required to upload each video to the shared drive. In addition, clinicians reported feeling some discomfort and negative emotions at having sessions reviewed by the research team, identifying “ … pressure of feeling like you were needing to make sure that assessments were done correctly (SLP01)”. However, the process of videorecording sessions became more acceptable as clinicians became more comfortable with the process, as explained by SLP02: “You always feel a bit funny in the beginning, but when you get into it, and you talk like you usually talk … it’s not a big deal.”

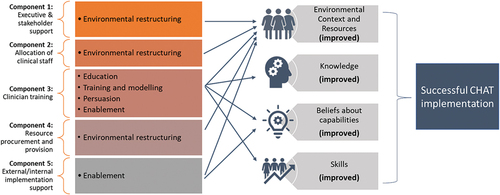

Potential effectiveness of the implementation intervention

The pre-post behavioural determinants survey results are presented in , showing improvements in 13 of the 15 domains. As shown in , the four domains targeted by the intervention (‘environmental context and resources’, ‘skills’, ‘beliefs about capabilities’, and ‘knowledge’) improved, suggesting the implementation intervention was potentially effective in addressing these barriers.

Figure 2. Logic model depicting implementation intervention components, intervention functions and behavioural determinants (domains) and outcomes.

Table 4. CHAT speech pathologists’ behavioural determinants survey results (n = 2).

An additional two domains not directly targeted by the planned implementation intervention also showed large improvements (i.e., ‘behavioural regulation’ and ‘reinforcement’), with possible reasons for these changes emerging from the qualitative interviews. No change was seen for the ‘memory, attention and decision-making’ domain, which was also the lowest scoring domain during both pre- and post-implementation surveys. The ‘intentions’ domain was the only domain that showed a small reduction in pre- and post-implementation scores; however, both scores (5; 4.75) were indicative of high intentions for CHAT implementation.

The potential effectiveness of the implementation intervention components was discussed in the interviews. Clinicians specifically spoke of the benefits of all of the five components (see Appendix A for more detail), i.e., executive and stakeholder support, the allocation of staff, training, resources and ongoing implementation support. Clinicians identified that the executive support (intervention component 1) that enabled the allocation of two clinical staff (intervention component 2) was key for implementation, as this allowed them to share their workload and knowledge. The added allocation of Allied Health Assistant time was also important for developing personalised therapy resources. In addition, clinicians identified that elements of the training (intervention component 3) enhanced their understanding of the evidence underlying the CHAT program, and that they developed skills in therapy planning through training. Resource procurement and provision (intervention component 4) including access to CHAT resources such as computer programs, information about therapy approaches, and provision of documentation templates was also seen as an important implementation component. Furthermore, the ongoing implementation support (intervention component 5) through supported clinical planning, clinical supervision and expert advice through the fidelity sessions was seen to enhance speech pathologists’ practice. In particular, speech pathologists reported that the fidelity requirements helped ensure accountability and consistency in their practice, which may explain the improvement seen in the ‘behavioural regulation’ domain of the barriers change survey. The ongoing implementation support was seen as being potentially effective in enhancing delivery of CHAT throughout the implementation phase.

Overall, the CHAT speech pathologists indicated that the implementation intervention had the potential to change their practice going forward, even if they were not providing the CHAT program. This was exemplified by SLP02, who stated, “I feel like it [CHAT] has completely changed my perspective and understanding of neuroplasticity and rehab(ilitation) because repetition is key,” and that she would “ … bring those general principles [to aphasia therapy going forward]”. In addition, SLP03 was optimistic that the success of the CHAT pilot would change practice to a more intensive rehabilitation model overall: “I’m really hopeful that we will just stop doing once a week anything … that we will just move to intensity … (and) with the shift we can leave some of some other practices behind.”

CHAT program evaluation

Feasibility of delivering the CHAT program

Recruitment Retention & Dose of Comprehensive Aphasia Therapy Received: All four patients completed the program and the dose of therapy received was high (See ). Three of the four patients received >90% of the total dose, whereas one patient, PWA4, only received 80% of the total dose due to medical illness. Other reasons for missed sessions included medical appointments, public holidays, absence of speech pathologist due to illness or leave, and other outside commitments of patients. The treatment provided by CHAT speech pathologists was comprehensive, incorporating a range of treatment approaches to address participants’ communication goals across ICF domains.

Table 5. Dose of comprehensive aphasia therapy received in therapy hours.

Barriers and facilitators to implementation: Speech pathologists generally perceived (as per interview data) that CHAT was feasible to implement, identifying nine key factors that influenced CHAT delivery (shown in ). The main facilitators to delivering CHAT included the clinical planning process, resource and staff availability, support from the research team, and the shared workload and positive working relationship between the two CHAT speech pathologists. The influence of this positive working relationship was exemplified by SLP01, who stated:

[a valuable working relationship] would be the single most important factor in a partnership of people delivering the therapy, where if you had a partnership of people that didn’t work … the program itself may not be as successful because you really need that.

Table 6. Summary of main barriers and facilitators to delivering CHAT.

There were also barriers to delivering CHAT, including challenges related to the organisational context, such as scheduling and time limitations and a lack of available therapy resources on occasion (e.g., when a program was on a single computer). In addition, clinician fatigue was a challenge, with SLP01 stating, “it wasn’t them [the patients] that was fatigued, most of the time it was us.” Both speech pathologists felt some initial stress when preparing for the CHAT cohort, however they both enjoyed delivering the program and commented on their sense of achievement:

What I really enjoyed about this program was that sense of actually finishing something and achieving something. And I think participants did too. I think there was that real cohesion within this group and they really valued being able to go through that together [SLP01].

Acceptability of delivering the CHAT program

Overall, patients reported high satisfaction with the CHAT program (mean = 5, strongly agree) and would recommend the program to others (mean = 5, strongly agree) (Appendix B). These positive findings were reinforced by the CHAT speech pathologists, who reported that patients were motivated and engaged throughout the 8 weeks. Although speech pathologists initially identified concern about patient fatigue during therapy, this was not observed: “They didn’t get tired of doing it. They loved getting success with doing the practice and the repetition” [SLP01]. When asked about the optimal intensity and duration of CHAT upon program completion, all four patients indicated they wanted more therapy; “I want more, maybe another month” [PWA2].

The CHAT speech pathologists perceived that CHAT was acceptable as a ‘one-off’ project but would be more challenging to embed in the long-term, as exemplified by SLP02, who stated, “ … concessions were made because it was the one off … it was only eight weeks.” CHAT speech pathologists noted that the program’s structure was different to their current service-delivery model and initially perceived that CHAT may not be a ‘good fit’ for the service. For example, SLP01 reported that CHAT “was a very different way of operating to plan eight weeks’ worth of therapy at week one and just deliver it … and the degree of personalisation that happened to meet those people’s goals … was … different.” However, speech pathologists found CHAT’s pre-determined time limit to be an acceptable change from usual care, as it helped to clarify patient expectations and to set a discharge period. Similarly, CHAT speech pathologists thought that the broader speech pathology team had mixed perceptions of the program’s potential to be embedded within existing services, with some members of the team being “really on board and really keen to … see how it worked,” while others “viewed it as more of a research project rather than being an actual clinical (service) … moving forward,” (SLP01). In general, attitudes toward the program were perceived to change throughout implementation, with increased interest and acceptance reported amongst non-CHAT clinicians. For example, the multidisciplinary team showed “an increased awareness of what we were doing and why and how the program worked,” (SLP01) and “could see that (patients) were doing so much better.” (SLP02). In order to be acceptable to clinicians delivering CHAT on an ongoing basis, there was a suggested need to “rotate through CHAT”; “You couldn’t just do an eight-week block of therapy and then do another eight weeks … to offer the same level of enthusiasm to a new set of participants, you do need to step away (SLP02).”

Potential effectiveness of delivering CHAT program

Patients’ clinical assessment results at baseline and post-therapy are displayed in .

Table 7. Patient clinical assessment results.

Language impairment

Variable changes in patients’ language impairment were observed on the CAT. Three patients (PWA1, PWA2, PWA3) demonstrated gains on the CAT modality mean T-score at post-therapy (Mean change = 2.54, SD = 2.9, range = 0.33-5.8), with one patient (PWA1) reaching significance. One patient, PWA1, demonstrated significant improvements across repetition, naming, and reading domains of the CAT, while PWA2 and PWA3 presented with more variable change profiles (See ). Patient PWA4, was below cut-off for one CAT domain (repetition) at baseline and demonstrated an improvement on this domain to within normal limits at post-therapy.

Functional communication

Three patients had a communication partner complete the CETI (PWA1, PWA3, PWA4). All three patients made positive gains on the CETI post-therapy (Mean change = 22.4, SD = 17.1, range = 3.8 – 37.4) with two patients (PWA1, PWA3) demonstrating changes greater than MDC90. The third patient, PWA4, achieved relatively high scores at pre-therapy (9/16 items at ceiling) and post-therapy (10/16 items at ceiling) and while demonstrating an overall positive improvement at post-therapy, this change did not reach MDC90.

Communication-related QOL

Three patients (PWA1, PWA2, PWA3) demonstrated positive improvements in communication-related QOL based on their total score on the SAQoL-39 at post-therapy (Mean change = 0.36, SD = .34, range = 0-.65), with two patients (PWA1, PWA2) demonstrating gains greater than MDC90. Patient, PWA4, was at ceiling for the communication domain on the SAQoL-39 at pre-therapy and post-therapy and demonstrated no change in total score at post-therapy.

Patient and Speech Pathologists’ Perspectives

According to the satisfaction survey, all four patients perceived improvements in their communication after CHAT (mean = 5, strongly agree): “After 8 weeks you feel you’ve improved. Improved my whole ability to speak, memory, strategies” [PWA4]. Furthermore, the interviews reinforced that the speech pathologists perceived CHAT as being potentially effective, with meaningful improvements noted in patients’ functional communication: “Everyone I felt made improvements and their significant others all commented on it … they were talking more. They noticed they’re initiating more in their verbal output.” [SLP02].

Discussion

This study is the first to evaluate and report on the clinical implementation of a mICAP within an existing healthcare service and builds upon previous work evaluating the effectiveness of ICAPs when delivered in mainstream healthcare settings (Babbitt et al., Citation2015; Brindley et al., Citation1989; Leff et al., Citation2021; Winans-Mitrik et al., Citation2014). Overall, the CHAT program was successfully delivered to a cohort of four participants with aphasia and their family members in a mICAP model. The program was feasibly delivered by 1.6 FTE Queensland Health speech pathologists as part of the clinical speech pathology service at the Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital Geriatric Assessment and Rehabilitation Unit. All CHAT program elements were delivered, including assessment and goal setting, and a high dose of comprehensive, goal-directed aphasia therapy (individual impairment, functional, and computer-based therapy and psychosocial group therapy). While CHAT speech pathologists recognised that the service delivery model deviated from usual care and challenges to implementation were identified, overall, the CHAT program was deemed feasible and acceptable to deliver within the healthcare service.

This study is the first to report the clinical outcomes of the CHAT program. We found preliminary support for the clinical effectiveness of CHAT in this pilot study, with significant improvements on measures of patients’ language impairment, functional communication and communication-related quality of life observed at post-therapy, consistent with the previous Aphasia LIFT program (Dignam et al., Citation2015; Rodriguez et al., Citation2013). Furthermore, these positive clinical outcomes are consistent with patients’ self-reported improvements following CHAT. While there is research evidence supporting the clinical effectiveness of ICAPs (Babbitt et al., Citation2015; Leff et al., Citation2021; Winans-Mitrik et al., Citation2014), individuals’ response to aphasia rehabilitation remains heterogenous (Menahemi-Falkov et al., Citation2021). Of the four patients who completed CHAT, three patients (PWA1, PWA2, PWA3) demonstrated significant gains on at least one outcome measure (CAT, CETI, SaQOL-39), determined using test-retest reliability data (i.e., CAT) and/or MDC90 (i.e., CETI, SaQOL-39). Significant therapy gains on the CAT were predominantly observed for the domains of verbal expression (e.g., naming, repetition) and aligned with participants’ communication goals. It is interesting to note that PWA4 did not demonstrate significant gains across any of the clinical outcome measures, however, this patient presented with mild aphasia and was at or approaching ceiling for all outcome measures. Despite the absence of gains on formal assessment, self-report data for PWA4 indicated perceived gains in their functional communication post-therapy and high satisfaction with the CHAT program.

The perceived effectiveness of the CHAT program by their treating speech pathologists and the broader multidisciplinary team, coupled with patients’ satisfaction with the program, were powerful facilitators for implementation. This finding was supported by the behavioural determinants survey results, whereby the domain of reinforcement demonstrated the second highest improvement after implementation, with improvements also noted in the domain of emotion. The perceived improvements in patients’ language and communication provided professional validation for the CHAT speech pathologists and supported the acceptability of the program as exemplified by SLP01:

To see the level of improvement from a clinician satisfaction point of view to really know that you’ve made a difference in that eight weeks because you don’t always get that I don’t think when you’re seeing people you know once or twice a week.

These findings are consistent with the results of Babbitt et al. (Citation2013), whereby seeing patient progress was identified as a key reward of delivering an ICAP, providing both professional validation and having a positive emotional impact on the speech pathologists involved.

Although patient fatigue has previously been identified as a potential barrier to the delivery of intensive services (Gunning et al., Citation2017) and the feasibility of ICAP delivery (Monnelly et al., Citation2023; Shrubsole et al., Citation2022), this finding was not observed in the present study, with all patients indicating a preference for more therapy. In contrast, clinician fatigue was identified as a key barrier, with clinicians concerned they would not have the stamina to deliver CHAT to consecutive cohorts. The positive professional working relationship and the shared clinical management of the patients, however, were found to counteract clinician fatigue and facilitate implementation. Furthermore, CHAT speech pathologists identified clinical rotation of the CHAT caseload as a potential solution to overcome the barrier of clinician fatigue in practice.

In contrast to Shrubsole et al. (Citation2022), the CHAT speech pathologists perceived the structure of the “ICAP innovation” as both a facilitator and a barrier to implementation. The design of the program enabled the speech pathologists to address specific, achievable goals within the 8-week period with a clear plan for patient discharge from the service. Additionally, key clinical components (e.g., session type, dose and frequency) prescribed in the CHAT protocol, and implementation processes (e.g., video recording of therapy sessions), may have further enhanced accountability and promoted treatment compliance (linked to the ‘behavioural regulation’ domain discussed below). However, the speech pathologists noted that as the mICAP model was more structured than usual clinical care it potentially limited the speech pathologists’ flexibility to adapt the treatment (e.g., type and dose of therapy provided) to the needs of the patient.

The implementation intervention, which consisted of five components, was found to be feasible, acceptable and potentially effective in supporting the delivery of CHAT in this Phase I study. Notably, the four domains targeted by the intervention (‘environmental context and resources’, ‘skills’, ‘beliefs about capabilities’, and ‘knowledge’) improved, suggesting the implementation intervention successfully addressed these domains. The ‘behavioural regulation’ domain, while not specifically targeted by the implementation intervention, also showed a large improvement, most likely due to the video-recorded sessions, structured clinical planning and mid-way review that served to enhance clinicians’ sense of accountability through feedback processes (Brown et al., Citation2019). The additional non-targeted domain of ‘reinforcement’ also showed a large improvement, possibly due to the positive patient feedback provided to clinicians. Although based on a small sample size, these preliminary data provide support for the potential effectiveness of the implementation intervention.

As the implementation intervention was multifactorial, it is difficult to determine the extent to which each component contributed to the successful delivery of CHAT, and further evaluation is required to understand the mechanisms of change. However, clinicians highly valued the components of clinical staff allocation and ongoing implementation support. Babbitt et al. (Citation2013) found that collaborative learning and peer/mentor support to implement evidence-based practice were key rewards of delivering an ICAP and these elements were explicitly incorporated into the implementation strategy for the current study. The speech pathologists regarded the implementation support provided, specifically the collaborative clinical planning model, as an important component of CHAT and a key facilitator for implementation. Limited research has explicitly considered the process of clinical planning for aphasia rehabilitation and as such, further exploration of this planning process when conducted in a collaborative model is warranted.

This study provides new insight into the implementation barriers experienced by speech pathologists when delivering ICAPs. Although there were some consistencies between our findings and previous research, such as challenges to the organisational context (e.g., resources, room bookings, scheduling) (Monnelly et al., Citation2023; Shrubsole et al., Citation2022; Trebilcock et al., Citation2019), ‘beliefs about capabilities’, ‘knowledge’ and ‘skills’ were not identified as barriers to CHAT implementation, in contrast to previous research (Shrubsole et al., Citation2022). These differences in previously reported barriers and the current implementation experience further suggest that the implementation strategy, particularly the training, resources and support provided, was potentially effective in equipping speech pathologists with the knowledge and skills to deliver the CHAT program. Moreover, the organisational commitment to the program in conjunction with the provision of ongoing implementation support likely helped to overcome the organisational barriers and enabled the overall feasible and acceptable delivery of CHAT in this Phase I study.

Limitations and future directions

This Phase 1 feasibility study explored the clinical implementation of the CHAT program at a single research site with a small sample of participants (n = 4 patients; n = 3 speech pathologists). While the small sample size allowed for a rich and multifaceted data set to understand the process of implementation, moving forward a larger sample size is required to evaluate the feasibility, acceptability and effectiveness of implementation. Furthermore, the present study was time-limited, with the planned implementation of one CHAT cycle. The temporary nature of the service may have impacted speech pathologists’ perspectives and acceptance of the program (e.g., preferential access to treatment rooms for CHAT patients) and as such, further consideration of these factors, in the context of a longer implementation period, is necessary.

Previous research identified funding and resources as a potential barrier to the implementation of ICAPs (Monnelly et al., Citation2023; Trebilcock et al., Citation2019). Funding for this study, including staffing and resources, was contained and provided through the Queensland Aphasia Research Centre. While this study is promising in demonstrating that implementation barriers could be overcome, this was likely only possible due to the allocation of funding for this project. Future research will need to consider funding design, including securing the necessary staffing, for sustainable ICAP implementation.

This study provided preliminary evidence for the clinical effectiveness of the CHAT program. In view of the variability of individual participants’ response to aphasia rehabilitation, consideration of the clinical effectiveness of CHAT in a larger sample of patients is required. Furthermore, it is important that future research consider the optimal clinical candidacy for CHAT, with respect to individual participant characteristics (e.g., aphasia severity, time post onset) and treatment components (e.g., dose). Furthermore, there is a need to consider measures of quality and outcome beyond measures of language and communication, to evaluate the implementation of an ICAP as a complex intervention. These research questions will be addressed in a planned, large-scale, hybrid clinical implementation and effectiveness study, which will evaluate the implementation of CHAT into 17 rehabilitation services across Australia (Grant APP1191820).

Conclusions

Despite growing evidence for the clinical effectiveness of ICAPs, this research is not routinely translated into clinical practice. This study has demonstrated the successful implementation of a mICAP, the CHAT program, into an Australian healthcare service. Furthermore, this study has advanced our understanding of speech pathologists and service managers’ perspectives on the implementation of CHAT and has provided preliminary support for the clinical effectiveness of this model. The findings from this study will be used to inform the implementation of CHAT in a large-scale, hybrid clinical implementation and effectiveness study and may be used to support the uptake of ICAPs into routine clinical care.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (189 KB)Supplemental Material

Download Zip (22 B)Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the speech pathology department and the multidisciplinary rehabilitation team at the Royal Brisbane & Women’s Hospital Geriatric Assessment and Rehabilitation Unit for their support of this project and their ongoing commitment to advance the state of aphasia rehabilitation services. We would like to formally acknowledge and thank the participants with aphasia and their family members for their contribution to this study.

Disclosure statement

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038.2023.2287766

Additional information

Funding

References

- Babbitt, E. M., Worrall, L., & Cherney, L. R. (2015, Nov). Structure, Processes, and Retrospective Outcomes From an Intensive Comprehensive Aphasia Program. American Journal of Speech Language Pathology, 24(4), S854–863. https://doi.org/10.1044/2015_ajslp-14-0164

- Babbitt, E. M., Worrall, L. E., & Cherney, L. R. (2013, Sep-Oct). Clinician perspectives of an Intensive Comprehensive Aphasia Program. Topics in Stroke Rehabilitation, 20(5), 398–408. https://doi.org/10.1310/tsr2005-398

- Baker, R., Camosso-Stefinovic, J., Gillies, C., Shaw, E. J., Cheater, F., Flottorp, S., Robertson, N., Wensing, M., Fiander, M., Eccles, M. P., Godycki-Cwirko, M., van Lieshout, J., & Jäger, C. (2015, Apr 29). Tailored interventions to address determinants of practice. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2015(4), Cd005470. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD005470.pub3

- Brady, M. C., Kelly, H., Godwin, J., Enderby, P., & Campbell, P. (2016). Speech and language therapy for aphasia following stroke [Review]. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (6), 397, Article Cd000425. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD000425.pub4

- Brindley, P., Copeland, M., Demain, C., & Martyn, P. (1989, 1989/12/01). A comparison of the speech of ten chronic Broca’s aphasics following intensive and non-intensive periods of therapy. Aphasiology, 3(8), 695–707. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038908249037

- Brown, B., Gude, W. T., Blakeman, T., van der Veer, S. N., Ivers, N., Francis, J. J., Lorencatto, F., Presseau, J., Peek, N., & Daker-White, G. (2019, Apr 26). Clinical Performance Feedback Intervention Theory (CP-FIT): A new theory for designing, implementing, and evaluating feedback in health care based on a systematic review and meta-synthesis of qualitative research. Implementation Science, 14(1), 40. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-019-0883-5

- Cane, J., O’Connor, D., & Michie, S. (2012). Validation of the theoretical domains framework for use in behaviour change and implementation research. Implementation Science, 7(1), 37. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-7-37

- Craig, P., Dieppe, P., Macintyre, S., Michie, S., Nazareth, I., & Petticrew, M. (2013, May). Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new Medical Research Council guidance. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 50(5), 587–592. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2012.09.010

- Curran, G. M., Bauer, M., Mittman, B., Pyne, J. M., & Stetler, C. (2012, Mar). Effectiveness-implementation hybrid designs: combining elements of clinical effectiveness and implementation research to enhance public health impact. Medical Care, 50(3), 217–226. https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0b013e3182408812

- Dignam, J. K., Copland, D. A., McKinnon, E., Burfein, P., O’Brien, K., Farrell, A., & Rodriguez, A. D. (2015). Intensive versus distributed aphasia therapy: A nonrandomized, parallel-group, dosage-controlled study. Stroke, 46(8), 2206–2211. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.009522

- Eccles, M. P., & Mittman, B. S. (2006). Welcome to implementation science. Implementation Science, 1(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-1-1

- Eldridge, S. M., Lancaster, G. A., Campbell, M. J., Thabane, L., Hopewell, S., Coleman, C. L., & Bond, C. M. (2016). Defining Feasibility and Pilot Studies in Preparation for Randomised Controlled Trials: Development of a Conceptual Framework. Plos One, 11(3), e0150205. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0150205

- Everett, E. A., Everett, W., Brier, M. R., & White, P. (2021). Appraisal of Health States Worse Than Death in Patients With Acute Stroke. Neurology: Clinical Practice, 11(1), 43–48. https://doi.org/10.1212/cpj.0000000000000856

- Fetters, M. D., Curry, L. A., & Creswell, J. W. (2013, Dec). Achieving integration in mixed methods designs-principles and practices. Health Services Research, 48(6 Pt 2), 2134–2156. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.12117

- French, S. D., Green, S. E., O’Connor, D. A., McKenzie, J. E., Francis, J. J., Michie, S., Buchbinder, R., Schattner, P., Spike, N., & Grimshaw, J. M. (2012, Apr 24). Developing theory-informed behaviour change interventions to implement evidence into practice: a systematic approach using the Theoretical Domains Framework. Implementation Science, 7, 38. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-7-38

- Graneheim, U. H., & Lundman, B. (2004, Feb). Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: Concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Education Today, 24(2), 105–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001

- Griffin-Musick, J. R., Off, C. A., Milman, L. H., Kincheloe, H., & Kozłowski, A. (2020). The impact of a university-based Intensive Comprehensive Aphasia Program (ICAP) on psychosocial well-being in stroke survivors with aphasia. Aphasiology, 35, 1363–1389 .

- Gunning, D., Wenke, R., Ward, E. C., Chalk, S., Lawrie, M., Romano, M., Edwards, A., Hobson, T., & Cardell, E. (2017). Clinicians’ perceptions of delivering new models of high intensity aphasia treatment. Aphasiology, 31(4), 406–426. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038.2016.1236359

- Hersh, D., Worrall, L., Howe, T., Sherratt, S., & Davidson, B. (2012). SMARTER goal setting in aphasia rehabilitation. Aphasiology, 26(2), 220–233. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038.2011.640392

- Hilari, K. (2011). The impact of stroke: Are people with aphasia different to those without? Disability and Rehabilitation, 33(3), 211–218. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2010.508829

- Hilari, K., Byng, S., Lamping, D. L., & Smith, S. C. (2003, Aug). Stroke and aphasia quality of life scale-39 (SAQOL-39) - Evaluation of acceptability, reliability, and validity [Article]. Stroke, 34(8), 1944–1950. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.str.0000081987.46660.ed

- Hoffmann, T. C., Glasziou, P. P., Boutron, I., Milne, R., Perera, R., Moher, D., Altman, D. G., Barbour, V., Macdonald, H., Johnston, M., Lamb, S. E., Dixon-Woods, M., McCulloch, P., Wyatt, J. C., Chan, A. W., & Michie, S. (2014, Mar 7). Better reporting of interventions: Template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ, 348, g1687. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g1687

- Hoover, E. L., Caplan, D. N., Waters, G. S., & Carney, A. (2017, Mar). Communication and quality of life outcomes from an interprofessional intensive, comprehensive, aphasia program (ICAP). Topics in Stroke Rehabilitation, 24(2), 82–90. https://doi.org/10.1080/10749357.2016.1207147

- Huijg, J. M., Gebhardt, W. A., Crone, M. R., Dusseldorp, E., & Presseau, J. (2014, Jan 15). Discriminant content validity of a theoretical domains framework questionnaire for use in implementation research. Implementation Science, 9, 11. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-9-11

- Lam, J. M. C., & Wodchis, W. P. (2010, Apr). The relationship of 60 disease diagnoses and 15 conditions to preference-based health-related quality of life in Ontario hospital-based long-term care residents. Medical Care, 48(4), 380–387. https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181ca2647

- Leff, A. P., Nightingale, S., Gooding, B., Rutter, J., Craven, N., Peart, M., Dunstan, A., Sherman, A., Paget, A., Duncan, M., Davidson, J., Kumar, N., Farrington-Douglas, C., Julien, C., & Crinion, J. T. (2021, Oct). Clinical effectiveness of the Queen Square intensive comprehensive aphasia service for patients with poststroke aphasia. Stroke, 52(10), e594–e598. https://doi.org/10.1161/strokeaha.120.033837

- Lomas, J., Pickard, L., Bester, S., Elbard, H., Finlayson, A., & Zoghaib, C. (1989, Feb). The Communicative Effectiveness Index (CETI): Development and psychometric evaluation of a functional communication measure for adult aphasia. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders, 54(1), 113–124. https://doi.org/10.1044/jshd.5401.113

- Menahemi-Falkov, M., Breitenstein, C., Pierce, J. E., Hill, A. J., O’Halloran, R., & Rose, M. L. (2021). A systematic review of maintenance following intensive therapy programs in chronic post-stroke aphasia: importance of individual response analysis. Disability and Rehabilitation, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2021.1955303

- Michie, S., Atkins, L., & West, R. (2014). The behaviour change wheel: A guide to designing interventions. Silverback Publishing.

- Michie, S., Johnston, M., Abraham, C., Lawton, R., Parker, D., & Walker, A. (2005). Making psychological theory useful for implementing evidence based practice: a consensus approach. Quality and Safety in Health Care, 14(1), 26–33. https://doi.org/10.1136/qshc.2004.011155

- Michie, S., Richardson, M., Johnston, M., Abraham, C., Francis, J., Hardeman, W., Eccles, M. P., Cane, J., & Wood, C. E. (2013, Aug). The behavior change technique taxonomy (v1) of 93 hierarchically clustered techniques: building an international consensus for the reporting of behavior change interventions. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 46(1), 81–95. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-013-9486-6

- Monnelly, K., Marshall, J., Dipper, L., & Cruice, M. (2023). Intensive and comprehensive aphasia therapy: A survey of the definitions, practices, and views of speech and language therapists in the United Kingdom. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders.

- Phillips, C. J., Marshal, A. P., Chaves, N. J., Jankelowitz, S. K., Lin, I. B., Loy, C. T., Rees, G., Sakzewski, L., Thomas, S., To, T. P., Wilkinson, S. A., & Michie, S. (2015). Experiences of using the Theoretical Domains framework across diverse clinical environments: A qualitative study [Article]. Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare, 8, 139–146. https://doi.org/10.2147/JMDH.S78458

- Pinnock, H., Barwick, M., Carpenter, C. R., Eldridge, S., Grandes, G., Griffiths, C. J., Rycroft-Malone, J., Meissner, P., Murray, E., Patel, A., Sheikh, A., & Taylor, S. J. (2017, Mar 6). Standards for Reporting Implementation Studies (StaRI) Statement. BMJ, 356, i6795. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i6795

- Rodriguez, A., Worrall, L., Brown, K., Grohn, B., McKinnon, E., Pearson, C., Van Hees, S., Roxbury, T., Cornwell, P., MacDonald, A., Angwin, A., Cardell, E., Davidson, B., & Copland, D. A. (2013). Aphasia LIFT: Exploratory investigation of an intensive comprehensive aphasia programme. Aphasiology, 27(11), 1339–1361. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038.2013.825759

- Rose, M., Cherney, L. R., & Worrall, L. E. (2013, Sep-Oct). Intensive Comprehensive Aphasia Programs: An international survey of practice. Topics in Stroke Rehabilitation, 20(5), 379–387. https://doi.org/10.1310/tsr2005-379

- Rose, M., Ferguson, A., Power, E., Togher, L., & Worrall, L. (2014). Aphasia rehabilitation in Australia: Current practices, challenges and future directions. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 16(2), 169–180. https://doi.org/10.3109/17549507.2013.794474

- Rose, M., Pierce, J. E., Scharp, V. L., Off, C. A., Babbitt, E. M., Griffin-Musick, J. R., & Cherney, L. R. (2021, Jul 10). Developments in the application of Intensive Comprehensive Aphasia Programs: An international survey of practice. Disability and Rehabilitation, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2021.1948621

- Scobbie, L., Dixon, D., & Wyke, S. (2011, May). Goal setting and action planning in the rehabilitation setting: development of a theoretically informed practice framework. Clinical Rehabilitation, 25(5), 468–482. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269215510389198

- Shrubsole, K., Copland, D., Hill, A. J., Khan, A., Lawrie, M., O’Connor, D. A., Pattie, M., Rodriguez, A., Ward, E., Worrall, L., & McSween, M.-P. (2022). Development of a tailored intervention to implement an Intensive and Comprehensive Aphasia Program (ICAP) into Australian health services. Aphasiology, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038.2022.2095608

- Shrubsole, K., Worrall, L., Power, E., & O’Connor, D. A. (2018, Sep). The Acute Aphasia IMplementation Study (AAIMS): A pilot cluster randomized controlled trial. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 53(5), 1021–1056. https://doi.org/10.1111/1460-6984.12419

- Stroke Foundation. (2021). Clinical guidelines for stroke management.

- Swinburn, K., Porter, G., & Howard, D. (2004). Comprehensive Aphasia Test. Psychology Press.

- Trebilcock, M., Shrubsole, K., Worrall, L., & Ryan, B. (2022, Dec 23). Pilot trial of the online implementation intervention Aphasia Nexus: Connecting Evidence to Practice. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/17549507.2022.2153918

- Trebilcock, M., Worrall, L., Ryan, B., Shrubsole, K., Jagoe, C., Simmons-Mackie, N., Bright, F., Cruice, M., Pritchard, M., & Le Dorze, G. (2019). Increasing the intensity and comprehensiveness of aphasia services: Identification of key factors influencing implementation across six countries. Aphasiology, 33(7), 865–887. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038.2019.1602860

- Verna, A., Davidson, B., & Rose, T. (2009, Jun). Speech-language pathology services for people with aphasia: A survey of current practice in Australia. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 11(3), 191–205. https://doi.org/10.1080/17549500902726059

- Wallace, S. J., Isaacs, M., Ali, M., & Brady, M. C. (2022). Establishing reporting standards for participant characteristics in post-stroke aphasia research: An international e-Delphi exercise and consensus meeting. Clinical Rehabilitation, 37(2), 199–214. https://doi.org/10.1177/02692155221131241

- Waltz, T. J., Powell, B. J., Fernández, M. E., Abadie, B., & Damschroder, L. J. (2019, Apr 29). Choosing implementation strategies to address contextual barriers: Diversity in recommendations and future directions. Implementation Science, 14(1), 42. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-019-0892-4

- Winans-Mitrik, R. L., Hula, W. D., Dickey, M. W., Schumacher, J. G., Swoyer, B., & Doyle, P. J. (2014). Description of an intensive residential aphasia treatment program: Rationale, clinical processes, and outcomes. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 23(2), S330–S342. https://doi.org/10.1044/2014_AJSLP-13-0102

- World Health Organization [WHO]. (2001). The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health. WHO.

Appendix A

Table A1. Potential effectiveness of implementation intervention components

Appendix B

Table B1.. Patient Satisfaction Survey