ABSTRACT

Background and aims

Literacy skills are typically affected in people with stroke aphasia, leading to reduced engagement in functional everyday reading/writing tasks, such as email/messaging via social media. The aim of this study was to investigate the outcomes of the TALES (Technology And Literacy Engagement after Stroke) programme, a group-based online literacy-focused programme for people with aphasia after stroke. This first evaluation of this programme aimed to examine outcomes related to feasibility, changes in language, literacy and self-ratings of communication skills.

Methods

Five participants with aphasia were assessed on a range of outcome measures relating to language and self-perception of communication skills. These were: the Western Aphasia Battery-Revised (WAB-R; (Kertesz, 2007)), literacy subtests from the Psycholinguistic Assessment of Language Processing in Aphasia (PALPA; (Kay et al., 1996)) and the Communication Outcomes after Stroke (COAST; (Long et al., 2008)). TALES consisted of a weekly group online session, 1:1 supported telehealth reading/writing practice and regular messaging via email.

Results and main contribution

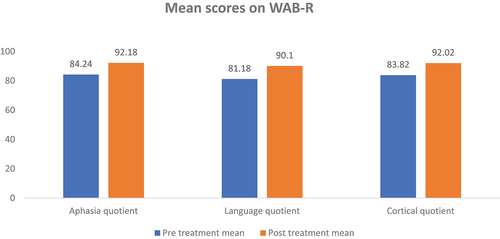

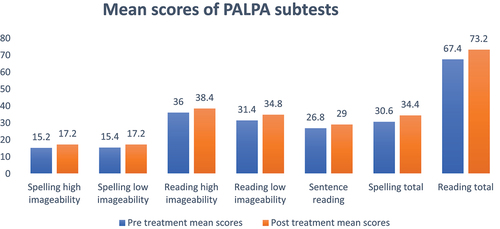

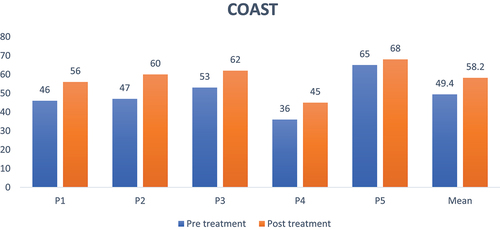

From a descriptive statistics perspective, the mean gains across the cohort were 7.94 (from 84.24 to 92.18) on the WAB AQ (aphasia quotient), 8.92 (from 81.18 to 90.10) on the WAB LQ (language quotient). Additionally, there was a change in the mean scores for PALPA subtests (31, 37 and 40) observed between the pre-treatment assessment and post-treatment assessment. Finally, the mean score increased by 8.8 (from 49.40 to 58.20) on the COAST (max score = 80). Results indicated gains in literacy and communication measures as well as changes to self-rating of communication reflecting changes in communication confidence.

Conclusions

Mindful of the threats to the internal validity inherent in the study design, the reported online therapy can overcome barriers such as distance and mobility limitations and may provide greater accessibility to therapy for individuals with aphasia. TALES was a low-therapist-input yet reasonably intensive treatment approach which embedded language practice immediately in functional use through the social group format and personally-relevant written communication.

Implications

The TALES programme meets many neuroscience principles of neurorehabilitation including “use it or lose it”, salience and transference. Future research may usefully investigate the contribution of the group format versus the functional literacy components towards these potentially promising early data.

Introduction

Functional literacy has become an essential skill required for full participation in many societies and arguably more so with advances in digital technology. Aphasia poses huge challenges to functional literacy for many stroke survivors (Caute et al., Citation2016; Lee & Cherney, Citation2022). Although the effects of aphasia on verbal language processing for comprehension and production are the diagnostic hallmarks of aphasic symptoms (e.g., providing us with the aphasic sub-diagnoses in the WAB-R (Kertesz, Citation2007)), aphasia can significantly affect a person’s functional literacy, making it difficult for them to engage in everyday activities and communicate with their loved ones via text messaging or social media (Thiel et al., Citation2015; Worrall et al., Citation2011). Specifically, people with aphasia (PWA) may struggle with reading comprehension for work or leisure or, at a more basic level, find it challenging to decode key single-word written information (Knollman-Porter et al., Citation2015; Thiel et al., Citation2016). Writing difficulties can manifest as impaired spelling, grammar, and/or coherence at discourse text levels, hindering effective communication through written means (Johansson-Malmeling et al., Citation2022). More broadly, PWA may struggle to read forms, take notes, and perform other literacy tasks essential for modern life (Dietz et al., Citation2011). These limitations will pose significant challenges to independence for those suffering from aphasia after a stroke (Dietz et al., Citation2011; Kjellén et al., Citation2017).

The growing dependence of society on technology for literacy tasks (e.g., online shopping, passwords for banking) can make it more difficult for individuals with aphasia to redefine and reintegrate their social roles. This is evident as the usage of handwritten documents has decreased (Thiel et al., Citation2015) and has been replaced by electronic communication such as emails and online written exchanges via fora such as WhatsApp, which allow interaction with friends and family members who are far away and also with colleagues working in the same building (Dietz et al., Citation2011). According to Parr (Citation1995), literacy should be viewed from a sociolinguistic perspective, and any assessment of the functional communication needs of individuals with aphasia should consider their writing and reading abilities. In particular, treatments targeting written modalities may capitalise on strengths in reading and writing to compensate for impairments in speaking and comprehending. Specifically, writing allows more time to retrieve words and organise language than speaking, which is more rapid and ephemeral (Beeson et al., Citation2013; Marshall et al., Citation2019). The permanence of the written word also enables reviewing, revision, and editing of language and ideas. Additionally, the visual-orthographic cues provided by writing can support word retrieval and sentence construction, thus facilitating communication (Johansson-Malmeling et al., Citation2022; Thiel & Conroy, Citation2022). By using written language through assistive technology, PWA can gain new prospects of improving their reading and writing skills and engaging with others (Brandenburg et al., Citation2013; Thiel et al., Citation2017).

As technology has rapidly advanced and becomes more widely accessible, telerehabilitation is increasingly used with PWA (Cacciante et al., Citation2021; Cetinkaya et al., Citation2023). This approach can help overcome obstacles of geography, financial constraints (travelling to appointments), and time limitations, while also providing the flexibility to increase the intensity of therapy from any location and at any time (Brennan et al., Citation2011). In addition, remote therapy allows clinicians to monitor patient progress and customise treatment to meet their unique needs (Des Roches et al., Citation2015; Stark & Warburton, Citation2018).

A recent systematic review of telehealth treatment of aphasia (Cetinkaya et al., Citation2023) found that the scope of teletherapy has been limited to specific areas such as reading, lexical or discourse skills, and that there has been a shortage of comprehensive teletherapy programmes that address holistic aspects of aphasia rehabilitation such as confidence, engagement and social interaction. This is despite the fact that technology has significant potential to support such broader applications. Additionally, while there has been a substantial focus on lexical therapies in the past, there is a growing need for therapies that focus on functional literacy, including reading and writing at sentence and discourse levels and via technological media (e.g., email, social media). By taking these principles into account, therapists can create more effective and comprehensive approaches to aphasia therapy (Thiel et al., Citation2015). Furthermore, adopting an explicitly technology-based functional approach, that is, supporting the direct use of social messaging and email, has the potential to exploit the neuroscientific principles of salience, transference, and intensity which are proposed as key factors in aphasia therapy (Raymer & Rothi, Citation2017). Specifically, therapy should ensure that activities are relevant and meaningful to the individual living with aphasia, that skills acquired can be transferred to everyday life, and that skills are practised with a high level of frequency and intensity.

Recent studies have explored the use of various online methodologies to enhance functional literacy for PWA. Interventions delivered in virtual worlds, text-to-speech technology, text messaging, e-readers, and virtual book clubs have shown potential benefits (Caute et al., Citation2016, Citation2022; Knollman-Porter et al., Citation2022; Lee & Cherney, Citation2022; Wallace et al., Citation2023). These have included improvements in communication skills, reading confidence and experience, comprehension, processing time, and feelings of social connection. Importantly, personalization is key, as individuals with aphasia have diverse needs and preferences (Knollman-Porter, Brown, et al., Citation2022). Technical issues remain a barrier, highlighting the need for training, adaptation and support in technology access for PWA. Overall, online methodologies appear promising for improving literacy and reducing isolation for PWA, but require careful implementation tailored to each individual.

Regardless of the growing research in writing therapy for individuals with aphasia (Mortley et al., Citation2001; Thiel et al., Citation2016), there remains a significant gap in the literature in terms of group-based interventions that also focus specifically on confidence within interactional skills and improving verbal communication skills. Moreover, functional task-oriented writing therapy, for example the use of email and social messaging, along with the use of writing as a tool to augment engagement and social participation, remain under-researched topics in current literature. While there is some evidence to suggest that functional literacy intervention can improve overall language abilities and communication (Thiel et al., Citation2015), few studies have explored the potential benefits of group-based interventions targeting functional literacy and engagement in people with aphasia (Pitt et al., Citation2019b). Therefore, there is therapeutic potential in investigating the impact of group-based writing therapy programmes for individuals with aphasia, particularly those that address functional tasks such as writing emails and social messaging. A possible outcome of this approach could be increased and more enjoyable written communication, with enhanced writing skills promoting social participation and engagement for individuals with aphasia (Thiel et al., Citation2016). In turn, this may improve the quality of life in stroke survivors with aphasia, supporting their ability to participate fully in social, educational, and professional contexts (Thiel et al., Citation2015).

The intensity of aphasia therapy is also a critical factor that significantly influences the outcomes of treatment (Monnelly et al., Citation2023). Recent research has demonstrated that increased intensity of aphasia therapy leads to improved outcomes in terms of recovery of language and communication skills (Brady et al., Citation2016), with a recent systematic review finding that the biggest improvements in overall language skills and comprehension were seen when participants received between 20-50 hours of speech and language therapy (RELEASE Collaborators, Citation2022). Recognising the critical role of intensity in aphasia rehabilitation could play an important role in improving the lives of those affected by this communication disorder. Importantly, technology allows for guided self-management (Cetinkaya et al., Citation2023), so it should be achievable and is certainly desirable to devise hybrid treatment programmes which incorporate both therapist-led and self-guided intervention in order to provide reasonable therapy dose with a relatively limited proportion of therapist time given available resources.

This leads us to the following research questions addressed in this study:

Is a hybrid treatment model feasible and can it achieve sufficient intensity of treatment based on a relatively time-efficient model of care?

Can we demonstrate improvements in language and literacy skills stemming from this treatment approach that are sustained once the treatment ceases?

Will participation in this treatment result in gains in confidence in communication skills, and how do any such changes relate to gains in language/literacy skills?

Method

Study Design

This research used a pre-and post-treatment assessment approach, documenting quantitative outcomes obtained before and after the implementation of the TALES (Technology and Literacy Engagement after Stroke) programme, and after a period of no treatment to gauge maintenance measures. TALES is an online literacy programme that focuses on student Speech and Language Therapists offering 1:1 online support within a group treatment context. TALES emerged as a ‘social responsibility’/civic engagement project, designed to facilitate outreach from the university to stroke survivors with aphasia, initiated within the University of Manchester in the Spring of 2021. This was in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic and restrictions on social participation limiting clinical treatment availability and social interaction.

Ethics

The study protocol for this first formal investigation of TALES was approved by the research ethics committee of the Division of Human Communication, Development & Hearing at the University of Manchester (Ref: 2022-14463-24948). All participants provided informed consent to participate.

Participants

The population for the study was individuals 18 years old or older who had developed chronic (>4 months) aphasia after a stroke. Given the need to create a therapeutic group environment and due to the preliminary nature of this study, we sought to recruit 6-8 individuals only with aphasia and relatedly, acquired dyslexia and dysgraphia, of varying subtypes and degrees of severity, with an interest in working on their functional literacy skills who resided in Greater Manchester and/or North-West England. Of the six participants recruited, five completed the study. One participant underwent baseline assessment, but chose not to participate in the treatment programme. All participants were fluent in English before aphasia onset and had no prior history of significant psychiatric illness or hearing loss. One of the participants had a moderate visual disability that did not affect participation in the study. The research team worked closely with this participant to ensure the font size and contrast were optimised for his visual abilities. For example, black Calibri font in 20-point size text on a white background provided the best contrast for the participant’s vision. During the intervention sessions, the research team monitored the participant’s ability to see and interact with the materials and provided verbal descriptions and guidance as needed. The participant confirmed that the font size and contrast accommodations enabled him to fully access and comprehend the intervention content. The study setting and tasks did not require any specialised auditory abilities beyond normal hearing. During consent procedures, participants confirmed their ability to hear the research team explain the study details. The research team also continually monitored participants’ understanding during all study activities to ensure adequate hearing and comprehension. Moreover, participants responded to email communication about the study and were offered overview/ introductory pre-programme contacts via the video conferencing platform Zoom. All participants had sufficient computer literacy skills to participate in the programme. The mean time since stroke onset was 15.8 months (range 5 to 40 months). describes basic demographics for these participants and their attendance information.

Table 1. Participants’ demographic data and attendance information.

Outcome Measures

As per the ROMA guidelines (Wallace et al., Citation2019), which aim to standardise assessment procedures for clinical aphasia assessment and reporting, participants were evaluated for aphasic symptoms and severity with the WAB-R (Kertesz, Citation2007), which is a comprehensive language test battery that provides measures of spontaneous speech, auditory verbal comprehension, repetition, naming and word finding, reading, and writing. The scores from these were used to calculate the participant’s Aphasia Quotient (AQ), Language Quotient (LQ) and Cortical Quotient (CQ). To assess participants’ literacy skills, reading and spelling subtests from the Psycholinguistic Assessment of Language Processing in Aphasia (PALPA) (Kay et al., Citation1996) were utilised, including subtest 31 (Oral Reading: Imageability x Frequency), subtest 37 (Oral Reading: Sentences), and subtest 40 (Spelling to Dictation: Imageability x Frequency). The PALPA is an exhaustive evaluation tool for both researchers and clinicians, which aims to provide a thorough examination of intact and impaired language-processing skills of adults with acquired language impairment, including aphasia (Bate et al., Citation2010). In addition, the Communication Outcome after Stroke (COAST) questionnaire (Long et al., Citation2008) was used to assess participants’ broader communication skills. The COAST is comprised of 20 items that evaluate the effect or level of communicative difficulties via a 5-point Likert Scale, where a score of 0 represents the lowest level of functioning and a score of 4 represents the highest level of functioning. Out of these 20 questions, 15 measure the communication abilities of the stroke survivor, while the other 5 assess the impact of communication difficulties on the stroke survivor’s quality of life. The COAST covers everyday communication (verbal and non-verbal), opinions of confidence and improvement in communication since stroke (providing an overview of communication) and the impact of functional communication on participants’ quality of life. The presentation format (simple language, visual support, detailed interviewer scripts) makes it accessible even for those with severe comprehension problems. In summary, the COAST scale measures self-perceived communication effectiveness and its impact on quality of life for people with post-stroke communication disabilities like aphasia and dysarthria. Its inclusion in the current study therefore allows us to contextulise any functional gains demonstrated in our other measures in terms of any improvements in broader quality of life.

Zoom was used for all online intervention sessions with participants. Participants were provided individual log-in details and support to access sessions equally. All pre- and post-testing assessments were completed by the first author only to ensure consistency. The speech and language therapy students were not involved in conducting formal assessments. Moreover, students had attended a preliminary training session to orientate them to interacting with PWA online and to the structure and schedule for the TALES programme. Students were well-known to the second and last authors, who were involved in their teaching. The chair of the online sessions (last author) did not work 1:1 with a PWA in the weekly online group session. Once the breakaway groups were set up, the chair moved between breakaway groups to offer help, support and modelling as required to the students. Students were also free to click the request help button which alerted the chair who could then address their specific query.

Intervention

The TALES programme protocol was implemented for the study. After baseline testing, the 5 participants took part in seven weekly online group sessions that lasted for 90 minutes each. During these sessions, they worked one-on-one with speech and language therapy students and also engaged in group conversation for further language/communication practice and support. The main focus of the individual sessions was to improve participants’ reading and writing skills, while the group format allowed for social communication and the formation of a supportive group environment. The objective was to provide a ‘safe space’ for the practical application of (online) face-to-face communication and literacy skills, leading to increased competence in reading and writing and increased confidence in using technology-based communication methods such as email and social media. provides details of the TALES programme. An overall macro-structure was established for each session as follows:

Welcome, introduction and outline of session plans for part 1 and part 2.

Brief statement of philosophy of the group, specifically to engage directly in communication formats that are likely to be used, e.g. email/WhatsApp/text messaging, and to focus on all word types (objects/nouns, actions/verbs, descriptors/ adjectives, adverbs) to maximise informativeness of writing.

Breakaway groups within Zoom: one person with aphasia working directly with one student SLT and/or member of the research team.

The student or research team member offering to lead the writing task, but gradually encouraging the person with aphasia to take this task on, as sessions progress.

Before the break or end of session, come back to the ‘main group’ (10-12 people) and have brief group discussion as to consider how everyone found a given task, and allow time/space for the participants with aphasia to begin to communicate verbally in the group online setting.

Increasingly, as group familiarity enhanced, time was gradually allowed to facilitate direct communication with group members, for example a participant with aphasia asking a student how their exam had gone, or asking another person with aphasia how they had enjoyed their holiday etc.

Close session with a summary of homework tasks, including purposefully trying to send more written message to friends and family.

Table 2. Details of the TALES programme.

During the online group sessions, several evidence-based reading and writing treatment methods were employed with the participants, for example, copy and recall for single word spelling (Beeson et al., Citation2002), spelling to dictation, spelling with letter cues (Johansson-Malmeling et al., Citation2022), understanding written words, and ordering written sentences (Purdy et al., Citation2019). In addition, reading and writing tasks were consistent across all participants.

App-based language therapy

In addition to the TALES programme, the aphasia therapy software Cuespeak (https://cuespeak.com/) was used as an individualised programme of home practice treatment. Cuespeak allows for tailoring of therapy tasks to the individual for use either in-person or remotely, either with support or independently. The therapy exercises in Cuespeak address a range of difficulties encountered in aphasia and apraxia of speech, including word finding, sentence processing, auditory comprehension, reading comprehension, writing and articulation. Most exercises use an interactive question-and-answer format, meaning that speech and language stimulation takes place in a context which goes some way towards emulating the demands of everyday communication. There is a range of help available when the questions prove difficult to answer, including spoken feedback on errors and spoken cues to help elicit spoken responses to questions. Exercises were adapted to make them suitable for people with anything from mild to severe symptoms.

Certain exercises within the Cuespeak app were selected for the participants to complete, rather than allowing them to freely use any part of the app. These included exercises focused on spelling and reading. Importantly, the research team selected different difficulty levels of the spelling and reading exercises for each participant based on their severity of language impairment. Participants with more severe deficits received simpler, more foundational exercises, while those with milder impairments worked on more advanced levels.

In addition to the weekly group and independent practice with writing and Cuespeak, all participants received weekly online 1:1 support for a period of 30 minutes. This allowed us to ensure any technical challenges were successfully resolved, and to provide participants with individualised guidance and encouragement in completing practice tasks. For example, the researcher engaged the participant in reading exercises and spelling practice using Cuespeak, solved any issues with technology (such as audio, accessing zoom, email/messaging apps), collaborated on setting communication goals, reviewed concepts from the group sessions, introduced helpful writing assistive technologies, and offered encouragement. Fidelity was clear and positive for group attendance, 1 to 1 attendance and engagement with the software but within the software there was lack of fidelity as regards specific time spent on tasks, as well as participant performance within these tasks. We did obtain an estimate of overall weekly time spent from participants, which provided some broad indication of ongoing engagement with the software.

Statistical Analyses

The statistical data analyses was conducted using IBM SPSS version 29 software. We used the Wilcoxon matched pairs signed rank test, a non-parametric approach, to investigate whether participants showed improvement on the pre-treatment measures. Thus, improvements on comparisons included pre- and post-WAB-R three quotient scores, PALPA (reading and spelling subtests) and COAST. In addition, the exact McNemar test was employed to evaluate the individual differences in participants’ performance before and after therapy in PALPA subtests where items were either correct/incorrect. A p value of < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Is a hybrid treatment model feasible and can it achieve sufficient intensity of treatment based on a relatively time efficient model of care?

In order to assess the feasibility of the TALES programme, participants and students were asked to provide informal feedback about their experiences. The results of this feedback were overwhelmingly positive, with the majority of participants reporting that they found the treatment to be helpful and engaging. One of the most common views that emerged from the feedback was the benefit perceived by participants of addressing functional concerns, for example the practicalities of writing text messages or emails. Participants also noted that the TALES programme positively impacted their social confidence. Another important aspect of the feedback was the high level of engagement and participation that the treatment elicited. In addition to the feedback from participants, students who were involved in the treatment also provided positive feedback. They reported that the treatment was well-structured and delivered in a clear and engaging manner. While a formal qualitative analysis was outside the scope of this preliminary study, we note the importance of gaining an in-depth understanding of participants’ experiences and perceptions of the programme, which will be the focus of future work.

The attendance rate of students and participants supports the feedback received from these individuals, suggesting that treatment was positively received and supported. Specifically, P2 and P3 had a full attendance record, having been present at all sessions. P1 and P4 had nearly full attendance, being present at 6 sessions out of 7 sessions. Lastly, P5 had been present at 5 out of 7 sessions, with family holiday plans affecting participation to some extent. presents data on the duration of group sessions, online 1:1 support, and independent practice. Overall, the TALES programme provided a total therapy time mean dose of approximately 36.5 hours.

(2) Can we demonstrate statistically significant changes in language and literacy skills stemming from this treatment approach, that are sustained once the treatment ceases?

Table 3. Summary of participants’ engagement in the TALES programme.

To assess whether participation in the treatment resulted in an improvement in language, we examined the mean WAB-R scores. provides pre- and post-treatment mean scores on WAB-R. As can be seen, mean scores increased after the treatment on all measures.

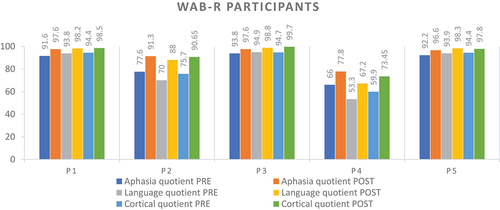

presents individual language assessment data for each participant, demonstrating improvements in the language skills.

To determine whether there were any changes in literacy skills stemming from the treatment approach, we analysed changes in the PALPA subtests’ scores from pre-treatment to post-treatment (see ). Mean scores for all the subtests show an improvement from pre-treatment assessment to post-treatment assessment. Moreover, the standard deviation decreased in most subtests, indicating that participants’ scores became more consistent after treatment (see ). The Wilcoxon’s Signed Rank Test was used to compare the scores of the group before and after therapy. There were statistically significant differences in the pre-and post-treatment assessments of some of the literacy skills (see ). The following measures showed statistically significant differences within the group before and after treatment (at p < .05): Aphasia Quotient, Language Quotient, Cortical Quotient, reading low imageability, and reading total. On the other hand, spelling high imageability, spelling low imageability, sentence reading, and spelling total did not show statistically significant differences within the group pre- and post-therapy (at p > .05).

Table 4. Statistical analyses for assessments (WAB-R, PALPA).

presents the McNemar exact test results for the PALPA subtests, focusing on changes in performance across participants. Pre- and post-treatment correct response counts are presented for each subtest. In Subtest 31, comprising 80 items, post-treatment performance indicated improvements for most participants, with no statistically significant differences (p >.05), except for P4 (p = .01) and P5 (p = .02). For Subtest 37, consisting of 36 items, overall correct response rates improved after the treatment, with no significant difference observed among participants. In Subtest 40, containing 40 items, all participants demonstrated enhanced performance post treatment, resulting in higher mean scores compared to the pre treatment phase. Notably, P4 showed significant improvement in Subtest 40 (p <.001).

(3) Will participation in this treatment result in gains in confidence in communication skills and how do any such changes relate to gains in language/literacy skills?

Table 5. Results for McNemar exact test on PALPA subtests.

To investigate whether participation in the treatment resulted in gains in confidence in communication skills for participants, we examined the difference between pre- and post-treatment scores on the COAST. shows participants’ pre- and post- treatment scores for COAST assessment. The mean score increased from 49.40 to 58.20. The minimum and maximum scores also increased from 36 to 45 and from 65 to 68, respectively, indicating an overall improvement in performance. Overall, all participants showed an increase in their COAST score, indicating gains in confidence in communication skills. However, the magnitude of these gains varied amongst participants, with some showing larger improvements than others. A Wilcoxon’s Signed Rank Test indicated a statistically significant difference in the scores of the group before and after the treatment (p =.042).

The study did not explicitly analyse the correlation between gains in confidence and gains in language/literacy skills due to the limited data points for correlation analysis. However, it was evident that the treatment approach seemed to positively impact both confidence and language/literacy skills. The statistically significant changes in the COAST, WAB-R, and PALPA scores in these participants with chronic aphasia suggested that improvements in confidence and language/literacy skills were likely related to the treatment.

Discussion

.The aim of this study was to examine the outcomes of the TALES programme, a group-based, online, literacy-focused programme designed for individuals with aphasia. This study represents the initial evaluation of the programme and sought to investigate its feasibility as well as any changes in language, literacy, and self-ratings of communication skills among participants. By exploring these outcomes, we aimed to clarify the potential benefits of the TALES programme in improving the communication abilities of PWA. This study contributes to the existing literature by addressing an important gap in knowledge regarding the impact of online, literacy-focused interventions for this population. Understanding the feasibility and potential benefits of such programmes can guide the development of future interventions and ultimately enhance the rehabilitation and quality of life for PWA.

To summarise the findings and mindful of the methodological limitations of the study (outlined later in this section), the results of the study provided encouraging outcomes as to the potential of the TALES treatment programme. The feedback from participants and student SLTs overwhelmingly supported the feasibility of the programme, with participants finding it helpful, engaging, and effective in addressing their functional concerns. The high level of engagement and participation further indicates the positive reception of the treatment approach (Meltzer et al., Citation2018). These findings suggested that the TALES programme achieved a relatively modest mean dosage of treatment while participant engagement and time-efficiency in delivery. Although the emerging dose literature in aphasiology has focused on sufficient dose (Harvey et al., Citation2021) in terms of being enough to effect change, it is also important to consider the acceptability of increasing dose, especially in people with long-term chronic aphasia (Harvey et al., Citation2022).

It is promising to establish that a group-based online treatment could be beneficial to PWA and could potentially be a beneficial way to provide services (Pitt et al., Citation2019a). In addition, none of the participants was omitted from a full session because of technological issues, and the therapists successfully carried out all the essential therapy activities as planned. It is worth mentioning that despite facing technological difficulties (such as internet connection issues), all participants expressed that they could clearly see (except P3 who had a moderate visual disability that did not affect participation) and hear the therapists and felt that the sessions proceeded without any major issues. Pitt et al. (Citation2019b) reported similar findings indicating that providing a group intervention for individuals with aphasia through online platforms can lead to enhanced communication, increased participation in communicative activities, and improved quality of life. Moreover, the current work emphasises the feasibility of using telepractice as an alternative to in-person services for intervention purposes. Importantly, the confidence changes obtained in this study were completely indirect, in that the focus was on functional literacy but in the group context (including both peer interactions and engagement with researchers and student SLTs). This nuance is an important one, which future research should investigate and optimise further (Lanyon et al., Citation2019).

The present study also examined the effect of the treatment approach on literacy skills. The analysis of PALPA subtests scores revealed statistically significant improvements in certain literacy skills, such as reading low imageability and reading total. The mean scores increased for all subtests, indicating a general enhancement in literacy skills. The decrease in standard deviation demonstrates that the participants’ scores became more consistent after the treatment. These findings suggest that this treatment approach can lead to improvements in some literacy skills. Interestingly, even though the mean scores for all PALPA spelling subtests increased, there were not statistically significant improvements in spelling. Although this lack of effect may stem from our small sample size, it is also possible that this may be due to the use of electronic writing instead of document writing in the treatment. However, Thiel et al. (Citation2017) indicated that assistive writing technologies may have the potential to assist individuals with aphasia in email writing, covering various significant aspects of performance. Importantly, while the inclusion of functional assessments of literacy, such as text-based reading and writing tasks, was outside the scope of this early work, these aspects of literacy should be addressed in subsequent research.

The current findings align with and build upon recent research on technology-assisted reading and writing therapies for PWA. For instance, Caute et al. (Citation2022) also found increased engagement and communicative confidence from a virtual reading group, supporting their previous in-person results (Caute et al., Citation2016). The TALES programme’s incorporation of writing practice and social messaging also relates to benefits reported for texting interventions (Lee & Cherney, Citation2022). Furthermore, gains in reading comprehension evidenced in the TALES participants who utilised text-to-speech reflect outcomes from other virtual book clubs using this technology (Wallace et al., Citation2023). Together, these studies demonstrate the potential of online platforms to facilitate continued literacy rehabilitation and social participation in PWA through increased accessibility, flexibility, and support. Findings from TALES and other recent work indicate that virtual delivery of reading and writing therapies can lead to meaningful improvements for PWA. Further research directly comparing online versus in-person approaches may be beneficial.

Mindful of the risk of bias inherent in our study design, the current data suggest that taking part in TALES appears to have helped participants become more confident in their communication abilities. The analysis of the COAST assessment scores before and after the treatment provides insights into the extent of these gains. All participants’ COAST scores clearly increased, indicating an improvement in their level of communication skill confidence. The magnitude of these increases, however, differed amongst the group. The differences in the degree of progress might be explained by a number of variables, including each participant’s baseline skill level, treatment receptivity, motivation, and engagement. It is likely that individuals with lower starting scores had more space for improvement and hence showed greater increases (Wilson et al., Citation2023). Nonetheless, we found a statistically significant change in the group’s overall scores before and after the therapy suggesting that, in addition to basic literacy skills, participation in TALES may also benefit participants in terms of confidence, with potential downstream positive effects on quality of life, although this speculation requires confirmation in future work.

As mentioned earlier, there are several serious limitations that question the internal validity of the study. Consequently, the current findings should be treated with caution due to the small sample size and the lack of a control group. Another limitation of the current study is the potential for assessment bias. As assessments were conducted by members of the research team who were aware of participants’ study conditions, unconscious bias may have influenced outcome ratings. Given the resources available within the study, we did not report on test-retest reliability. However, although the statistical outcomes reported were robust for widely used non-parametric tests, in future work we will also utilise minimal detectable change statistics for greater rigour. Finally, while fidelity was demonstrated for group and one-on-one attendance along with overall engagement with the software, there was a lack of fidelity tracking time on specific software tasks and performance within these. Clearly, future research in this area must prioritise methodological quality and rigorous reporting to produce more robust evidence. These limitations indicate that our findings should be interpreted with caution due to threats to internal validity. Nonetheless, the observed improvements in this small-scale study point to fruitful avenues for larger-scale work. In particular, the outcome measures used in this study were successful in tracking performance improvements over time, forming the groundwork for a larger trial. Additionally, participants had varied lengths of post-onset duration and different, though relative mild-moderate levels of aphasia severity. A next step in refining TALES will be to include a wider range of aphasia severity in participants.

Speech and language therapy services have been widely influenced by the COVID-19 pandemic. Referral patterns have changed, standard care has been interrupted, and interventions have been adjusted, resulting in varying effects on patient outcomes (Chadd et al., Citation2021). The limitations imposed by the pandemic, such as restricted movement and reduced availability of in-person therapy, have highlighted the potential of remote intervention for individuals with aphasia. Telerehabilitation has bridged the gap created by the pandemic and demonstrated its effectiveness in maintaining and improving communication abilities in aphasia patients (Cassarino et al., Citation2022), with positive outcomes, including improvements in language skills, functional communication, and quality of life (Carr et al., Citation2022; Cassarino et al., Citation2022). Therefore, it may be advantageous to prioritise the utilization of online therapy approaches like TALES in future research, aiming to improve the well-being of PWA.

It will be necessary to examine the reliability and generalisability of the TALES programme. Specifically, conducting studies with a larger and more diverse group of participants (such as gender, ethnicity, age), more robust study design will be essential to ensure adequate statistical power and generalizability. Moreover, conducting qualitative research could yield more comprehensive information about participants’ experiences with the TALES and potential processes of change. Additionally, qualitative methods may offer deeper insights into participant satisfaction with online delivery, and the influence of technology on group dynamics. Considering the availability of adequate technology for potential participants is also crucial and providing the necessary apps may enhance the participation rate among them.

Conclusion

Overall, the current study demonstrates the feasibility of the TALES treatment programme. The treatment approach showed promise in achieving some intensity of treatment while being time-efficient, and led to improvements in language and literacy skills. Additionally, participation in the treatment resulted in gains in self-ratings of communication skills. These findings underline the potential benefit of technology engagement in relation to functional literacy and provide a template for further investigation to understand how to optimise and interpret these promising early data.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

REFERENCES

- Bate, S., Kay, J., Code, C., Haslam, C., & Hallowell, B. (2010). Eighteen years on: What next for the PALPA? International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 12(3), 190–202. https://doi.org/10.3109/17549500903548825

- Beeson, P. M., Higginson, K., & Rising, K. (2013). Writing treatment for aphasia: A texting approach. https://doi.org/10.1044/1092-4388(2012/11-0360)

- Beeson, P. M., Hirsch, F. M., & Rewega, M. A. (2002). Successful single-word writing treatment: Experimental analyses of four cases. Aphasiology, 16(4–6), 473–491. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687030244000167

- Brady, M. C., Kelly, H., Godwin, J., Enderby, P., & Campbell, P. (2016). Speech and language therapy for aphasia following stroke. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 6. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD000425.pub4

- Brandenburg, C., Worrall, L., Rodriguez, A. D., & Copland, D. (2013). Mobile computing technology and aphasia: An integrated review of accessibility and potential uses. Aphasiology, 27(4), 444–461. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038.2013.772293

- Brennan, D. M., Tindall, L., Theodoros, D., Brown, J., Campbell, M., Christiana, D., Smith, D., Cason, J., & Lee, A. (2011). A blueprint for telerehabilitation guidelines—October 2010. Telemedicine and E-Health, 17(8), 662–665. https://doi.org/10.5195/ijt.2010.6063

- Cacciante, L., Kiper, P., Garzon, M., Baldan, F., Federico, S., Turolla, A., & Agostini, M. (2021). Telerehabilitation for people with aphasia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Communication Disorders, 92, 106–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcomdis.2021.106111

- Carr, P., Moser, D., Williamson, S., Robinson, G., & Kintz, S. (2022). Improving functional communication outcomes in post-stroke aphasia via telepractice: An alternative service delivery model for underserved populations. International Journal of Telerehabilitation, 14(2). https://doi.org/10.5195/ijt.2022.6531

- Cassarino, L., Santoro, F., Gelardi, D., Panerai, S., Papotto, M., Tripodi, M., Cosentino, F. I. I., Neri, V., Ferri, R., Ferlito, S., & others. (2022). Post-stroke aphasia at the time of COVID-19 pandemic: A telerehabilitation perspective. Journal of Integrative Neuroscience, 21(1), 8. https://doi.org/10.31083/j.jin2101008

- Caute, A., Cruice, M., Devane, N., Patel, A., Roper, A., Talbot, R., Wilson, S., & Marshall, J. (2022). Delivering group support for people with aphasia in a virtual world: Experiences of service providers. Disability and Rehabilitation, 44(26), 8264–8282. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2021.2011436

- Caute, A., Cruice, M., Friede, A., Galliers, J., Dickinson, T., Green, R., & Woolf, C. (2016). Rekindling the love of books–a pilot project exploring whether e-readers help people to read again after a stroke. Aphasiology, 30(2–3), 290–319. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038.2015.1052729

- Cetinkaya, B., Twomey, K., Bullard, B., EL Kouaissi, S., & Conroy, P. (2023). Telerehabilitation of aphasia: A systematic review of the literature. Aphasiology. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038.2023.2274621

- Chadd, K., Moyse, K., & Enderby, P. (2021). Impact of COVID-19 on the speech and language therapy profession and their patients. Frontiers in Neurology, 12, 629190. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2021.629190

- Des Roches, C. A., Balachandran, I., Ascenso, E. M., Tripodis, Y., & Kiran, S. (2015). Effectiveness of an impairment-based individualized rehabilitation program using an iPad-based software platform. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 8, 1015. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2014.01015

- Dietz, A., Ball, A., & Griffith, J. (2011). Reading and writing with aphasia in the 21st century: Technological applications of supported reading comprehension and written expression. Topics in Stroke Rehabilitation, 18(6), 758–769. https://doi.org/10.1310/tsr1806-758

- Harvey, S., Carragher, M., Dickey, M. W., Pierce, J. E., & Rose, M. L. (2022). Dose effects in behavioural treatment of post-stroke aphasia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Disability and Rehabilitation, 44(12), 2548–2559. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2020.1843079

- Harvey, S. R., Carragher, M., Dickey, M. W., Pierce, J. E., & Rose, M. L. (2021). Treatment dose in post-stroke aphasia: A systematic scoping review. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 31(10), 1629–1660. https://doi.org/10.1080/09602011.2020.1786412

- Johansson-Malmeling, C., Antonsson, M., Wengelin, Å., & Henriksson, I. (2022). Using a digital spelling aid to improve writing in persons with post-stroke aphasia: An intervention study. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 57(2), 303–323. https://doi.org/10.1111/1460-6984.12696

- Kay, J., Lesser, R., & Coltheart, M. (1996). Psycholinguistic assessments of language processing in aphasia (PALPA): An introduction. Aphasiology, 10(2), 159–180. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687039608248403

- Kertesz, A. (2007). Western Aphasia Battery–Revised. Pearson. https://doi.org/10.1037/t15168-000

- Kjellén, E., Laakso, K., & Henriksson, I. (2017). Aphasia and literacy—The insider’s perspective. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 52(5), 573–584. https://doi.org/10.1111/1460-6984.12302

- Knollman-Porter, K., Brown, J. A., Hux, K., Wallace, S. E., & Crittenden, A. (2022). Reading comprehension and processing time when people with aphasia use text-to-speech technology with personalized supports and features. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 31(1), 342–358. https://doi.org/10.1044/2021_AJSLP-21-00182

- Knollman-Porter, K., Hux, K., Wallace, S. E., Pruitt, M., Hughes, M. R., & Brown, J. A. (2022). Comprehension, processing time, and modality preferences when people with aphasia and neurotypical healthy adults read books: A pilot study. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 31(6), 2569–2590. https://doi.org/10.1044/2022_AJSLP-22-00121

- Knollman-Porter, K., Wallace, S. E., Hux, K., Brown, J., & Long, C. (2015). Reading experiences and use of supports by people with chronic aphasia. Aphasiology, 29(12), 1448–1472. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038.2015.1041093

- Lanyon, L., Worrall, L., & Rose, M. (2019). “It’s not really worth my while”: Understanding contextual factors contributing to decisions to participate in community aphasia groups. Disability and Rehabilitation, 41(9), 1024–1036. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2017.1419290

- Lee, J. B., & Cherney, L. R. (2022). Transactional success in the texting of individuals with aphasia. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 31(5S), 2348–2365. https://doi.org/10.1044/2022_AJSLP-21-00291

- Long, A., Hesketh, A., Paszek, G., Booth, M., & Bowen, A. (2008). Development of a reliable self-report outcome measure for pragmatic trials of communication therapy following stroke: The Communication Outcome after Stroke (COAST) scale. Clinical Rehabilitation, 22(12), 1083–1094. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269215508090091

- Marshall, J., Caute, A., Chadd, K., Cruice, M., Monnelly, K., Wilson, S., & Woolf, C. (2019). Technology-enhanced writing therapy for people with aphasia: Results of a quasi-randomized waitlist controlled study. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 54(2), 203–220. https://doi.org/10.1111/1460-6984.12391

- Meltzer, J. A., Baird, A. J., Steele, R. D., & Harvey, S. J. (2018). Computer-based treatment of poststroke language disorders: A non-inferiority study of telerehabilitation compared to in-person service delivery. Aphasiology, 32(3), 290–311. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038.2017.1355440

- Monnelly, K., Marshall, J., Dipper, L., & Cruice, M. (2023). Intensive and comprehensive aphasia therapy—A survey of the definitions, practices and views of speech and language therapists in the United Kingdom. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders. https://doi.org/10.1111/1460-6984.12918

- Mortley, J., Enderby, P., & Petheram, B. (2001). Using a computer to improve functional writing in a patient with severe dysgraphia. Aphasiology, 15(5), 443–461. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687040042000188

- Parr, S. (1995). Everyday reading and writing in aphasia: Role change and the influence of pre-morbid literacy practice. Aphasiology, 9(3), 223–238. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687039508248197

- Pitt, R., Theodoros, D., Hill, A. J., & Russell, T. (2019a). The development and feasibility of an online aphasia group intervention and networking program – TeleGAIN. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 21(1), 23–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/17549507.2017.1369567

- Pitt, R., Theodoros, D., Hill, A. J., & Russell, T. (2019b). The impact of the telerehabilitation group aphasia intervention and networking programme on communication, participation, and quality of life in people with aphasia. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 21(5), 513–523. https://doi.org/10.1080/17549507.2018.1488990

- Purdy, M., Coppens, P., Madden, E. B., Mozeiko, J., Patterson, J., Wallace, S. E., & Freed, D. (2019). Reading comprehension treatment in aphasia: A systematic review. Aphasiology, 33(6), 629–651. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038.2018.1482405

- Raymer, A. M., & Rothi, L. (2017). Principles of aphasia rehabilitation. The Oxford Handbook of Aphasia and Language Disorders. New York: Oxford University Press.

- RELEASE Collaborators. (2022). Dosage, intensity, and frequency of language therapy for aphasia: A systematic review–based, individual participant data network meta-analysis. Stroke, 53(3), 956–967. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.121.035216

- Stark, B. C., & Warburton, E. A. (2018). Improved language in chronic aphasia after self-delivered iPad speech therapy. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 28(5), 818–831. https://doi.org/10.1080/09602011.2016.1146150

- Thiel, L., & Conroy, P. (2022). ‘I think writing is everything’: An exploration of the writing experiences of people with aphasia. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 57(6), 1381–1398. https://doi.org/10.1111/1460-6984.12762

- Thiel, L., Sage, K., & Conroy, P. (2015). Retraining writing for functional purposes: A review of the writing therapy literature. Aphasiology, 29(4), 423–441. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038.2014.965059

- Thiel, L., Sage, K., & Conroy, P. (2016). The role of learning in improving functional writing in stroke aphasia. Disability and Rehabilitation, 38(21), 2122–2134. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2015.1114038

- Thiel, L., Sage, K., & Conroy, P. (2017). Promoting linguistic complexity, greater message length and ease of engagement in email writing in people with aphasia: Initial evidence from a study utilizing assistive writing software. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 52(1), 106–124. https://doi.org/10.1111/1460-6984.12261

- Wallace, S. E., Hux, K., Knollman-Porter, K., Patterson, B., & Brown, J. A. (2023). A mixed-methods exploration of the experience of people with aphasia using text-to-speech technology to support virtual book club participation. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1044/2023_AJSLP-23-00094

- Wallace, S. J., Worrall, L., Rose, T., Le Dorze, G., Breitenstein, C., Hilari, K., Babbitt, E., Bose, A., Brady, M., Cherney, L. R., & others. (2019). A core outcome set for aphasia treatment research: The ROMA consensus statement. International Journal of Stroke, 14(2), 180–185. https://doi.org/10.1177/1747493018806200

- Wilson, S. M., Entrup, J. L., Schneck, S. M., Onuscheck, C. F., Levy, D. F., Rahman, M., Willey, E., Casilio, M., Yen, M., Brito, A. C., & others. (2023). Recovery from aphasia in the first year after stroke. Brain, 146(3), 1021–1039. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awac129

- Worrall, L., Sherratt, S., Rogers, P., Howe, T., Hersh, D., Ferguson, A., & Davidson, B. (2011). What people with aphasia want: Their goals according to the ICF. Aphasiology, 25(3), 309–322. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038.2010.508530