ABSTRACT

Background

Over the past two decades, “aphasia awareness” has been studied across 19 countries and five continents. Despite international efforts, awareness of aphasia has remained persistently low and little consideration has been given to what it actually means to be “aphasia aware”. In order to raise awareness of aphasia, it is first necessary to understand how key stakeholders perceive the topic, and their experience of raising awareness of aphasia and the factors which may enable or hinder success.

Aims

To explore international stakeholder: (1) perspectives on aphasia awareness, (2) experiences of delivering aphasia awareness campaigns; and to identify (3) barriers to, and facilitators of, successful aphasia awareness raising activities.

Methods & Procedures

Two cross-sectional, international, online surveys were conducted. Survey 1 was conducted with people living with aphasia (PLWA: people with aphasia, family members, friends, carers). Survey 2 was conducted with people who work with PLWA (workers: clinicians, researchers, volunteers, consumer organisation representatives). The surveys contained 31 and 25 questions respectively across four topic areas: demographics, perspectives on aphasia awareness, experiences of running aphasia awareness campaigns, and barriers to, and facilitators of, raising awareness. Closed and open-ended responses were elicited. Data were analysed using descriptive statistics and qualitative content analysis.

Outcomes and Results

A total of 105 PLWA and 306 workers, from 39 countries, completed the surveys. More than 90% of participants considered aphasia awareness to be “very” or “extremely important”, primarily due to the communication and information barriers faced by people with aphasia daily. Participants reported that being “aphasia aware” meant knowing: that aphasia does not affect intelligence (PLWA), and how to communicate with a person with aphasia (workers). In total, 15% of PLWA and 31% of workers reported they had previously run an aphasia awareness campaign. Barriers to campaign success included insufficient resources (e.g., funding, time) and lack of experience and specialised skills (e.g., health promotion). Key facilitators included people living with aphasia (including celebrities) sharing their stories and being key members or leaders of the campaign.

Conclusions

“Aphasia awareness” was considered essential by all participants. To enhance aphasia awareness misconceptions and stereotypes about communication disability must be challenged and practical education on how to communicate with a person with aphasia provided. These results lay the foundation for developing an international aphasia awareness campaign. Future research is needed to identify campaign priorities and to co-design the campaign.

Introduction

Over the past two decades, more than 20 studies across 19 countries and five continents have examined international rates of aphasia awareness, however, the concept of “aphasia awareness” is inconsistently defined in the literature. The majority of aphasia awareness studies, including those based on the “Awareness of Aphasia Survey” (Code et al., Citation2001) consider having heard the word “aphasia” to be awareness (e.g., Aljenaie & Simmons-Mackie, Citation2022; Code et al., Citation2001, Citation2016; McMenamin et al., Citation2021; Simmons-Mackie et al., Citation2002; Vuković et al., Citation2017). Other studies required participants to be able to define or describe features of aphasia to be deemed “aphasia aware”. For example, the studies completed by the National Aphasia Association (National Aphasia Association, Citation2016, Citation2020, Citation2022), considered participants to be “aphasia aware” if they had heard the word and could identify aphasia as a language disorder.

Irrespective of how “aphasia awareness” has been conceptualised, levels of aphasia awareness amongst the general public have remained persistently low, with rates for having heard the word ranging from 10% in the United Kingdom (UK; Aphasia Alliance, Citation2008) to 67.8% in the United States of America (USA; National Aphasia Association, Citation2022).Footnote1 More than half of the studies investigating aphasia awareness reported rates of awareness below 20% across a range of populations and countries (Aljenaie & Simmons-Mackie, Citation2022; Aphasia Alliance, Citation2008; Chazhikat, Citation2011; Code et al., Citation2001; Guo & Lim, Citation2018; Kent & Wallace, Citation2006; McCann et al., Citation2013; McMenamin et al., Citation2021; National Aphasia Association, Citation2016, Citation2020; Simmons-Mackie et al., Citation2002; Vuković et al., Citation2017). In addition, many of these studies explored if those who were deemed to be “aphasia aware” also had basic knowledge of the condition (for example, knowing features or symptoms related to aphasia). Again, basic knowledge of aphasia was consistently reported to be low, ranging from 1% in Argentina (Code et al., Citation2016) to 78.6% in Singapore (Guo & Lim, Citation2018). More than half the studies reported rates below 10% (Chazhikat, Citation2011; Code et al., Citation2001, Citation2016; Hill et al., Citation2019; Kent & Wallace, Citation2006; McCann et al., Citation2013; McMenamin et al., Citation2021; National Aphasia Association, Citation2016, Citation2020; Patterson et al., Citation2015; Simmons-Mackie et al., Citation2002; Speakability, Citation2000; Vuković et al., Citation2017). The relatively high rate of awareness in Singapore may be attributable to the research context. The Singapore data were collected in a hospital foyer where participants may have been more likely to have health and medical knowledge. Awareness and knowledge of aphasia have also been found to be low when compared with awareness and knowledge of other health conditions. For example, McCann et al. (Citation2013) compared awareness and knowledge of aphasia, stroke, and Parkinson’s disease (PD) in New Zealand. They found public awareness of aphasia (11%) was significantly lower than awareness of stroke (99.3%) or PD (96%) and knowledge of aphasia (1.5%) was significantly lower than knowledge of stroke (53.3%) and PD (31%). Concerningly, aphasia awareness has also been found to be low amongst health professionals (McCann et al., Citation2013). McCann et al. (Citation2013) found that only 68% of healthcare workers in New Zealand demonstrated awareness (i.e., having heard the word aphasia) and 21% had basic knowledge of aphasia.

Despite the international focus on awareness and basic knowledge of aphasia, Simmons-Mackie et al. (Citation2020) point out that having heard the word aphasia does not improve understanding of the condition and is not a helpful outcome of aphasia awareness campaigns. Similarly, extremely basic knowledge such as knowing aphasia is a language disorder does not convey the enormous impact of the condition on a person with aphasia and their family and friends. To date, no research has investigated how people living and working with aphasia conceptualise “aphasia awareness”.

Increased “aphasia awareness” is a key priority for those living, and working, with aphasia (Ali et al., Citation2022; Flynn et al., Citation2009; Power et al., Citation2015; Wallace et al., Citation2017), and is of great importance to those living with aphasia (Flynn et al., Citation2009). In addition, changed attitudes about aphasia through increased awareness and education is a desired treatment outcome for people with aphasia and their families (Wallace et al., Citation2017). This is understandable considering that low aphasia awareness has economic, psychosocial, and political consequences (Code, Citation2020; Code et al., Citation2001, Citation2016; Elman et al., Citation2000; Simmons-Mackie et al., Citation2002, Citation2020). The importance of aphasia awareness to the global aphasia community is reflected in the numerous aphasia awareness campaigns conducted every year by individuals, local services, and consumer organisations to try to increase awareness. Examples include observance days, weeks and months for causes associated with aphasia, for example, stroke weeks, and for aphasia specifically, for example, aphasia awareness month organised by National Aphasia Association (NAA) in the United States (June). Overarchingly, campaign messages can be categorised into: (1) description and definition of aphasia, (2) education that aphasia is a loss of language, not intelligence, (3) presentation of statistics about aphasia, and (4) provision of tips for communicating with a person with aphasia (Simmons-Mackie et al., Citation2020). However, despite the international focus on raising awareness and the many campaigns conducted every year, aphasia awareness campaigns, and their outcomes are often not documented.

Developing a campaign to raise awareness of a health condition such as aphasia is complex (Noar, Citation2006). Simmons-Mackie et al. (Citation2020) suggested several possible problems with public aphasia awareness campaigns internationally. They contended that campaigns around the world have failed to identify a unified and compelling message, have lacked coordination across organisations and campaigns and have frequently targeted audiences already aware of aphasia. They also argued that campaigns have not been informed by theory and research from other disciplines such as marketing, health promotion and communications research and have not included people living with aphasia and health-care professionals in their design. Finally, they highlighted that there was no evidence of the evaluation of the impact of the campaigns.

Currently there is uncertainty around what people living and working with aphasia mean by aphasia awareness, what they think others need to know about aphasia to be aphasia aware, and what they are hoping to achieve by raising awareness of aphasia. No previous studies have investigated these questions or the relative importance of aphasia awareness to the various stakeholders. Therefore, we aimed to explore stakeholder: (1) perspectives on aphasia awareness including the importance of aphasia awareness; what “aphasia awareness” most means to them; what they think others need to know to be “aphasia aware”; and what an “aphasia awareness” campaign should do; (2) experiences (components and outcomes) of previous aphasia awareness campaign(s) and (3) the barriers to, and facilitators of, their success.

Materials and methods

Study design

A cross-sectional study design was used, with two online surveys developed using Qualtrics software. Survey development and reporting was guided by the Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys (CHERRIES; Eysenbach, Citation2004; see Supplemental Material 1). Ethical approval was received from The University of Queensland’s Human Research Ethics Committee (2021/HE002174).

Consumer and community involvement

Two people with lived experience of aphasia (one person with aphasia and one family member) were advisors throughout this study and guided the research. They provided critical review of participant-facing materials; disseminated recruitment materials; and provided advice on the mode of data collection. One advisor with aphasia identified the following benefits to using an online survey: it can be completed when convenient; it can be completed in stages and revisited; there is less pressure than when a researcher is present; and an online format is easier than a written survey that you must complete and send back.

Participants

Participants were an international sample of: (1) people with aphasia and their family, friends, or carers and (2) people who work with people with aphasia, including clinicians, researchers, leaders of aphasia consumer organisations or aphasia centres, assistants, or volunteers. For brevity, these two groups will henceforth be referred to as (1) PLWA (people living with aphasia) and (2) workers.

To be eligible to take part, PLWA were required to: identify as having aphasia of any aetiology or be a family member, friend, or carer of a person diagnosed with aphasia. Workers were required to have current or prior experience working with people with aphasia. All participants were required to be: (1) aged eighteen or above (2) able to participate in an online survey independently or with support, (3) sufficiently proficient in the English language to complete the survey, and (4) able to provide informed consent (indicated through completion of the consent section at the start of the survey).

Recruitment

Invitations to participate were distributed via email and social media through international networks, including aphasia consumer organisations, aphasia research centres, community aphasia groups, universities, speech pathology professional organisations and special interest groups, and the Collaboration of Aphasia Trialists. The survey link was shared with these networks and snowball sampling used to reach as many participants as possible. Recruitment remained open for approximately 8 weeks from mid-March until 11th May 2022, with two reminders sent via email, two prompts via Facebook and five prompts via Twitter through the same networks described above.

Survey development and design

Separate surveys were designed for the two participant groups. Our advisors with lived experience guided the questions included in the surveys, the wording of these questions and response options, and ensured that the survey for PLWA and its delivery mode were accessible to people with aphasia. The survey for PLWA used aphasia friendly formatting guidelines (Rose et al., Citation2011a, Citation2011b, Citation2012) and audio recordings of the questions and responses were included to further increase accessibility. Closed answer options were also used to help people with aphasia to respond. Please see supplemental material 2 for a sample of this survey which illustrates these accessibility features. The survey for PLWA comprised six sections with a total of 31 questions. The survey for workers also comprised six sections with a total of 25 questions. Please see Supplemental Material 3 for an overview of the survey sections and questions for each stakeholder group. A mix of question types were presented including: (1) yes-no questions; (2) multiple choice questions using both closed and open response options; (3) Likert scales; and (4) open-ended questions. The response options for the multiple-choice questions were randomised for each participant to minimise an order effect as per Eysenbach (Citation2004).

Piloting

The surveys were piloted with three representatives from each stakeholder group and our advisors living with aphasia. Minor revisions were made following the pilot and their feedback, including:

Specifying required number of responses to multiple-choice questions.

Removing ranking response options, as respondents found this difficult.

Moving questions about receiving research results and participating in future research to the end of the survey.

Analysis

The data from each survey were exported to Microsoft Excel. Datasets that only included responses to consent and/or demographic questions were removed. Descriptive statistics were used to analyse the quantitative data obtained from the closed questions. Where participants selected the “other” option in response to a question and provided their specific response, these responses were grouped and tallied. The data arising from the open-ended questions were analysed using content analysis (Graneheim & Lundman, Citation2004), which included: multiple readings of the free-text responses to identify meaning units (groups of words or statements that related to the same central meaning), and develop content codes (the label of the meaning units), subcategories, categories (groups of content that share common features) and themes (threads of underlying meaning).

Results

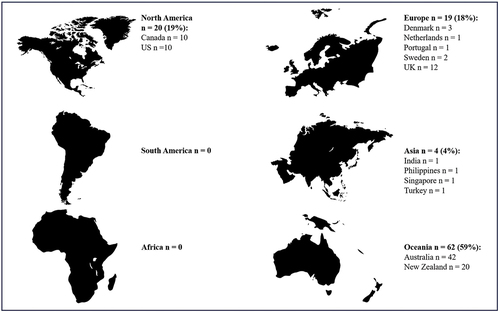

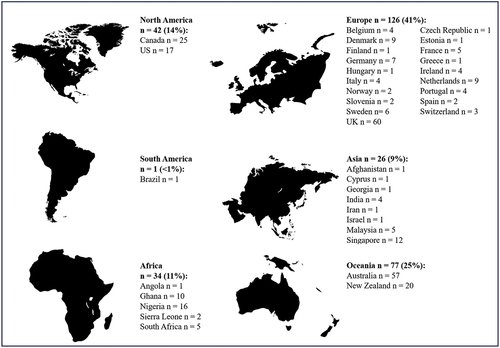

A total of 160 PLWA and 343 workers commenced their respective surveys. Following removal of incomplete or ineligible responses, datasets from 105 PLWA and 306 workers (total n = 411) were included in the analysis (see and ).

Participant demographics – PLWA

PLWA were from 13 countries and four continents (see ). More than half of the participants (59%, n = 62) reported being from Australia (n = 42) or New Zealand (n = 20). There were no responses from South America or Africa.

Most responses came from countries where English is the most spoken language with 87% (n = 91) of participants reporting English as their main language. However, respondents reported speaking 10 languages other than English: Danish (n = 3); Swedish (n = 2), and n = 1 for Thai, Dutch, Hindi, Māori, Portuguese, Filipino, Cantonese, Turkish. outlines the demographic information for PLWA.

Table 1. Participant demographics – people with lived experience of aphasia, n = 105.

Participant demographics – workers

Workers identified as being from 37 countries and six continents (see ). Most responses (41%) were from Europe with 19 countries represented. The United Kingdom had the highest number of responses per country.

A total of 75% of workers (n = 228) reported that English was the main language they used at work. In addition, participants identified speaking a further 30 languages at work, including; Dutch (n = 11), Danish (n = 9), German (n = 8), French (n = 7), Swedish (n = 6), Mandarin (n = 6), Malay (n = 5), Portuguese (n = 4), Italian (n = 4), Spanish (n = 2), Hindi (n = 2), Chinese dialects other than Mandarin and Cantonese (n = 2), Twi (n = 2), Ga (n = 2), Greek (n = 2), Slovenian (n = 2), Norwegian (n = 2) and the following languages were all spoken by one respondent each (Catalan, Marathi, Farsi, Finnish, Hebrew, Czech, Flemish, Ewe, Kannada, Estonian, Cantonese, Hungarian and Hokkien). provides an overview of the complete demographic information for workers.

Table 2. Participant demographics – people who work with people with aphasia n = 306.

Perspectives on aphasia awareness

Importance of aphasia awareness

“Aphasia awareness” was rated as very or extremely important by 93% of PLWA and 95% of workers on a 5-point Likert scale. Participants identified their top 5 reasons why aphasia awareness was important (see ).

Table 3. Reasons why aphasia awareness is important.

Both stakeholder groups agreed on the same primary reason why aphasia awareness is important: “People with aphasia face barriers to communication and information every day”. For workers, this was closely followed by, “People don’t know how to support communication for people with aphasia”. The second most important reason for PLWA at 47% was “Aphasia affects not only the person with aphasia but also their family and friends”.

What aphasia awareness means to key stakeholders

outlines the full results relating to “what aphasia awareness means” for both stakeholder groups. The same top 3 explanations of aphasia awareness were selected by both stakeholder groups, albeit with different order of priority: “Educating people about aphasia” (i.e., having knowledge of aphasia, was the first choice for PLWA at 24% and third for workers at 19%); “People know how to communicate with a person with aphasia”, (first choice for workers at 25% and second for PLWA at 18%); and “People understand the condition aphasia” (second choice for workers at 21% and joint third choice for PLWA at 13%). Equal third for PLWA was “People with aphasia are included in society”. It is also worth noting that none of the workers and only 6 PLWA (6%) selected “People have heard the word aphasia”.

Table 4. What aphasia awareness most means to stakeholders.

What people need to know about aphasia to be “aphasia aware”

outlines the results from both stakeholder groups about what specific content people need to know about aphasia to be considered “aphasia aware”. Both groups selected the same top three responses: “Aphasia does not affect intelligence” (first response for PLWA at 75% and third response for workers at 68%); “What helps people with aphasia to communicate” (first response for workers at 85% and second for PLWA at 67%), and “Impact on people with aphasia” (second response option for workers at 71% and third choice for PLWA at 66%).

Table 5. What stakeholders think people need to know about aphasia to be “aphasia aware”.

What should an aphasia awareness campaign do?

All the results pertaining to what stakeholders think an aphasia awareness campaign should do are presented in .

Table 6. What are the three most important things an aphasia awareness campaign should do?

Both stakeholder groups selected the same top two responses, albeit in different order: 58% of PLWA and 55% of workers selected “Educate people about aphasia” and 58% of workers and 50% of PLWA selected “Change the way people communicate with people with aphasia”. In third place PLWA (42%) chose “Increase the number of people who know that the condition exists”. The third choice for workers (45%) was “Help people with aphasia to re-integrate into society”.

Experiences of running an aphasia awareness campaign

In total, 15% of PLWA (n = 16; 8 countries) and 31% of workers (n = 96; 33 countries) reported having run an aphasia awareness campaign.

What have stakeholders done to raise awareness of aphasia

The most frequently reported awareness raising activities were 1) giving talks (n = 11 PLWA; n = 84 workers), 2) social media post(n = 9 PLWA; n = 70 workers), 3) displaying posters (n = 8 PLWA; n = 70 workers), 4) sending emails (n = 8 PLWA; n = 42 workers), 5) writing articles for newspapers or magazines (n = 8 PLWA; n = 41 workers), 6) holding fundraising events (n = 5 PLWA; n = 41 workers), 7) radio interviews (n = 5 PLWA; n = 39 workers), 8) making a YouTube video or similar (n = 3 PLWA; n = 35 workers), 9) TV interviews (n = 5 PLWA; n = 24 workers) and 10) writing to a politician (n = 2 PLWA; n = 18 workers), 11) Other (n = 5 PLWA; n = 17 workers).

Content analysis of the open-ended “other” responses revealed awareness raising activities fell into six themes: Inclusion; Occasions; Creations; Knowledge and skills development; and Championing the cause. These themes and their underlying categories are presented in . The theme “Inclusion” referred to involving people living with aphasia (people with aphasia and family members) in the awareness raising activity. The “Occasions” theme primarily related to events, such as a performance or movie night, organised to raise awareness of aphasia which often doubled as a fundraising event. “Creations” referred to making products such as a keyring or game incorporating specific information about aphasia. ‘Knowledge and skills development” was divided into three categories: “Training”, “Education”, and “Informational material”. “Training” was used for activities aimed at teaching a specific skill or behaviour, such as communication training; “Education” referred to activities such as talks aimed at increasing knowledge and “Informational material” related to producing resources such as handouts, or a website to provide further information about aphasia. “Championing the cause” had the subcategories of “Advocacy”, “Lobbying” and “Media”. “Advocacy” related to supporting people with aphasia, “Lobbying” referred to communicating directly with a government representative about aphasia and “Media” referred to activities such as interviews with various media outlets (e.g., newspaper interviews). As these answers were reported in the “other” option, these answers were not tallied with the responses to the closed questions.

Table 7. Content analysis of open “other” response to question: what have you done to raise awareness of aphasia?

Most effective ways to raise awareness

Both groups reported that from their perspective giving talks was the most effective way to raise awareness (n = 12 PLWA; n = 71 workers), followed by social media posts (n = 7 PLWA; n = 49 workers), TV interviews (n = 4 PLWA; n = 37 workers), radio interviews (n = 6 PLWA; n = 26 workers), writing articles for newspapers or magazines (n = 6 PLWA; n = 19 workers), making a YouTube video or similar (n = 2 PLWA; n = 19 workers), displaying posters (n = 4 PLWA; n = 18 workers), holding a fundraising event (n = 1 PLWA; n = 12 workers), sending emails (n = 1 PLWA; n = 6 workers), and writing to a politician (n = 0 PLWA; n = 3 workers).

Target audiences of aphasia awareness campaigns

The most common target audiences reported by PLWA were friends (n = 14), healthcare workers (n = 13), family (n = 11), health service organisations, such as hospitals or rehabilitation centres (n = 10), and the general public (n = 9). Further target audiences reported by PLWA can be found in Supplemental Material 4. The most common target audience reported by workers were the general public (n = 32), healthcare professionals (n = 24), people with aphasia (n = 7), family members of people with aphasia (n = 7), and caregivers of people with aphasia (n = 5). Additional target audiences reported by workers can be found in Supplemental Material 5. Forty two percent of this sample (n = 27) reported targeting a single audience and the remaining 58% (n = 38) targeted multiple audiences.

Specific details of campaigns run by workers

Participants described that planning campaigns included team members, students, and/or people living with aphasia and on occasion with people with expertise in communications. Occasionally, campaigns were spontaneous or reactive, such as in response to the announcement of Bruce Willis’ diagnosis of aphasia. The most common campaign goals (as reported by participants) were: raise awareness of aphasia (n = 23), followed by raising awareness of how to communicate with people with aphasia (n = 9), understand what aphasia is and its impact (n = 8), education (unspecified) (n = 4), that people have heard the word “aphasia” (n = 3), and to raise money (n = 3). See Supplemental Material 6 for the full range of goals reported. outlines the results from the content analysis of the open text boxes relating to specific awareness raising activities. The themes, categories and subcategories were the same as those described above and presented in .

Table 8. Specific awareness raising activities undertaken by workers.

The audiences of the aphasia awareness campaigns were required to engage in information receiving activities about aphasia, for example, reading written communications, listening to talks, or watching videos, or activities with more interactive components, such as communicating with people living with aphasia, role play, using picture and gestures to communicate, altering communication environments, and simulations, (see Supplemental Material 7 for the full list of activities undertaken by audiences).

The remaining specific details of the campaigns run by workers, including the key message, messenger, communication channels, context for the campaign, length of the campaign, whether or not the campaign was successful, whether or not it was evaluated and if so how, the cost of the campaign, whether or not it was funded and if so how, are summarised in .

Table 9. Specific details of components of aphasia awareness campaigns run by workers.

Barriers and facilitators to raising awareness of aphasia

Both stakeholder groups were asked about barriers they had encountered when raising awareness of aphasia and what had facilitated their efforts. Content analysis of their responses revealed several barriers and facilitators for each group. PLWA reported the following barriers: (1) their aphasia: “Because I have aphasia it’s hard get words out” and “How do I explain what I have in a way that others will understand”, (2) aphasia being a hidden disability: “it’s invisible like ADD or bipolar or depression”, “Not many people know what the word aphasia is or means. It’s an invisible condition” and “Aphasia can be a hidden disability, and sometimes people just don’t understand”, (3) lack of confidence to speak, (4) access to audience, “People are so busy these days it is hard to access people these days”, and “There needs to be more training for healthcare providers but that is hard to get their attention”, (5) lack of time, (6) lack of knowledge of how they can help, (7) lack of resources, (8) fatigue and (9) transport. Workers cited: (1) lack of time/funds/resources, (2) lack of skills including marketing skills, knowing the most effective communication channels to use and how to evaluate the impact of a campaign, (3) lack of interest in general public in understanding conditions which do not concern them, “aphasia is not a ‘hot topic’”,(4) lack of understanding about the size of the problem, (5) lack of continuity, (6) competition from other causes, and (7) cultural issues as the main barriers to raising awareness.

In regard to what facilitated awareness raising, PLWA reported: (1) telling their story, (2) videos, (3) photos, paintings, music, or being able to refer to a famous person(s) who lives with the condition, (4) attitudes of others, (5) social media, (6) aphasia consumer organisations and (7) brochures. Workers highlighted (1) people with aphasia and/or their families as key members or leaders of the awareness campaign, (2) famous people talking about aphasia, (3) attitudes of others – willing to take time and listen, (4) passion and drive to raise awareness, (5) support from employers and colleagues, (6) support of other/larger organisations/charities (7) support of marketing and communications professionals, (8) funding and (9) videos and social media

When asked for “other” comments about running an aphasia awareness campaign, only workers responded and they made the following recommendations:

Call for a world-wide strategy.

Involve people with lived experience throughout.

Target funders/commissioners.

Need to be aware of the audience.

Pre-produced package of resources with a consistent message available free/low cost.

Invest in input from public health/marketing professionals.

Celebrity spokesperson, such as Michael J Fox for Parkinson’s disease, could help.

Discussion

We explored the perspectives and experiences of people living and working with aphasia globally on aphasia awareness. Aphasia awareness was very or extremely important to both stakeholder groups and this was attributed to the daily communication barriers encountered by people living with aphasia. This is the first study we are aware of to investigate these topics and it provides insights into how international stakeholders conceptualise “aphasia awareness”, what they have done to raise awareness and barriers and facilitators to aphasia awareness raising success.

The results of our study, align with what is already known about how different stakeholders view aphasia awareness (Flynn et al., Citation2009; Wallace et al., Citation2017), and support the notion that aphasia awareness is more than having heard the word aphasia or being able to define the term. This extends the concept of aphasia awareness that was previously used to evaluate aphasia awareness (Code et al., Citation2001; National Aphasia Association, Citation2016, Citation2020, Citation2022). Our findings lend support to the argument that raising aphasia awareness involves challenging misconceptions and stereotypes about communication disability and providing practical education, such as how to communicate with a person with aphasia. The desired outcome of aphasia awareness campaigns, therefore, is that target audiences know aphasia masks intelligence and how to support communication with people living with aphasia to help them participate in everyday life. An awareness campaign should target key audiences and focus on what those audiences need to do to enable people with aphasia to overcome the daily communication barriers they encounter. This concurs with public information specialists Christiano and Neimand (Christiano & Neimand, Citation2017, p. 36) who argue for the need to “move beyond just raising awareness” by using “behavioural science to craft campaigns and use messaging and concrete calls to action that get people to change how they feel, think or act and as a result create long lasting change”.

Although “raising awareness of aphasia” was the most commonly reported goal of campaigns described by workers in our study, it was not clear what they meant by the use of this term or what they were hoping to achieve by “raising awareness”. This aligns with our argument outlined by Simmons-Mackie et al. (Citation2020) that there is no standard definition of aphasia awareness and uncertainty whether the term means (1) having heard the word aphasia, (2) having basic knowledge of aphasia or (3) having a basic understanding of the disability of aphasia (Simmons-Mackie et al., Citation2020). The remaining data gained from exploring the goals of the previously conducted aphasia awareness campaigns provided greater insight into what workers were trying to achieve with their campaigns which included people knowing: (1) How to communicate with people with aphasia, (2) Understand what aphasia is, and its impact, and (3) Education. These findings suggest that while the ultimate umbrella goal might be “Aphasia Awareness”, defining the goals more specifically is more helpful.

Regarding running aphasia awareness campaigns, our results provided further insights into factors which have likely impacted the limited success of aphasia awareness campaigns to date. The results illustrated the wide range and variability of campaigns in terms of activities, goals, target audiences, messages, messengers, and context (length and timing). This variability, alongside the lack of investment, time, resources, and skills amongst people trying to raise awareness of aphasia and a reported lack of interest from the general public could further explain the lack of awareness raising success to date. Our findings support the call from Simmons-Mackie et al. (Citation2020) for an international collaborative effort as our results also found campaigns were run at a local or national level with little or minimal funding and by people (clinicians and people living with aphasia) who did not have the specific expertise (e.g., health promotion, marketing, or media skills) to run a campaign. We are not aware of any other studies which have specifically explored barriers and facilitators to awareness raising success, but the factors identified in our study support points raised by Simmons-Mackie et al. (Citation2020) that campaigns around the world failed to identify a unified and compelling message, were not coordinated across organisations, and tended to target audiences who were already aware of aphasia.

Information about the impact of specific campaigns is limited and this was reflected in our results which showed little had been done to evaluate campaigns and measure their impact over time. Of the specific campaigns detailed by workers, only 50% were evaluated and these evaluations were largely limited to feedback provided immediately after an event whether it be verbal or by survey or questionnaire. There is little or no information available about the broader and longer-term impact of campaigns and what changes may have occurred as a result of those campaigns.

Study limitations

The main limitation of this study is that the surveys could only be completed in English. This would have been particularly challenging for participants with aphasia for whom English was not their first language. It is also likely that many elderly people (with or without aphasia) from non-English speaking countries would have less proficiency in English. Despite having participants from 39 countries, the absence of translations likely limited participation, and the cultural and linguistic diversity of the sample. Responder bias is a fundamental issue with any survey, and it must be acknowledged that people who felt strongly about aphasia awareness were more likely to complete the survey.

Future directions

The results of this study provide insights into the perspectives and experiences of international stakeholders on aphasia awareness. These findings are important for developing an international campaign to raise awareness of aphasia globally. Future research should identify priorities for such a campaign and co-design the campaign itself.

Conclusion

International stakeholders from the global aphasia community considered “aphasia awareness” essential to reducing communication barriers in everyday life for people with aphasia. To enhance aphasia awareness, they reported that campaigns should challenge misconceptions and stereotypes about communication disability and provide practical education on how to communicate with a person with aphasia. Much has been done to try to improve levels of aphasia awareness around the world but campaigns to date have not been co-ordinated across organisations and countries, have frequently been under resourced and not evaluated. These results support the need for an international collaborative effort to increase aphasia awareness globally.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (619.3 KB)Acknowledgments

We wish to acknowledge and thank Dr Tanya Rose for her contribution to this study in the planning of this project and survey development.

Claire Bennington is supported by an Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship.

Emma and Kim Beesley are funded by the Queensland Aphasia Research Centre, which is funded by the Bowness Family Foundation and an anonymous donor.

Dr Sarah J. Wallace is supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council under an Emerging Leadership Investigator Grant (1175821).

Picture materials included in the aphasia-friendly survey include:

ParticiPics – a free, searchable database of pictographic images developed by the Aphasia Institute, https://www.aphasia.ca/participics

Speakeasy Aphasia-friendly Images, speakeasy-aphasia.org.uk

Lightbulb images adapted from Light Bulb Free HQ Image by Brett Croft under a CC BY-NC 4.0 licence, and Cartoon Light Bulb by j4p4n under a CC0 Public Domain licence.

Rehabilitation signpost image by Unknown Author is licensed under CC BY-SA

Road image by Road-Free-PNG-Image.png (2244×1887) (pngall.com).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038.2024.2330145

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. The National Aphasia Association’s 2022 survey was completed in the immediate aftermath of the announcement of actor Bruce Willis’ aphasia diagnosis at the end of March 2022.

References

- Ali, M., Soroli, E., Jesus, L. M. T., Cruice, M., Isaksen, J., Visch-Brink, E., Grohmann, K. K., Jagoe, C., Kukkonen, T., Varlokosta, S., Hernandez-Sacristan, C., Rosell-Clari, V., Palmer, R., Martinez-Ferreiro, S., Godecke, E., Wallace, S. J., McMenamin, R., Copland, D., Breitenstein, C., and Brady, M. C., on behalf of the Collaboration of Aphasia Trialists (CATs). (2022). on behalf of the Collaboration of Aphasia Trialists (CATs). Aphasiology, 36(4), 555–574. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038.2021.1957081

- Aljenaie, K., & Simmons-Mackie, N. (2022). Public awareness of aphasia in Kuwait. Aphasiology, 36(10), 1149–1158. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038.2021.1942773

- Aphasia Alliance. (2008). Aphasia – The hidden disability [Unpublished data].

- Chazhikat, E. (2011). Awareness of aphasia and aphasia services in south India: Public health implications. Online Manuscript. https://digital.library.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metadc86166/m2/1/high_res_d/Chazhikat%20Emlynn.pdf

- Christiano, A., & Neimand, A. (2017, Spring). Stop raising awareness already. Stanford Social Innovation Review. https://ssir.org/articles/entry/stop_raisingawareness_already

- Code, C. (2020). The implications of public awareness and knowledge of aphasia around the world. Annals of Indian Academy of Neurology, 23(Suppl 2), S95–S101. https://doi.org/10.4103/aian.AIAN_460_20:10.4103/aian.AIAN_460_20

- Code, C., Mackie, N. S., Armstrong, E., Stiegler, L., Armstrong, J., Bushby, E., Carew-Price, P., Curtis, H., Haynes, P., McLeod, E., Muhleison, V., Neate, J., Nikolas, A., Rolfe, D., Rubly, C., Simpson, R., & Webber, A. (2001). The public awareness of aphasia: An international survey. International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders, 36(s1), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.3109/13682820109177849

- Code, C., Papathanasiou, I., Rubio‐Bruno, S., Cabana, M., Villanueva, M. M., Haaland‐Johansen, L., Prizl-Jakovac, T., Leko, A., Zemva, N., Rochon, E., Leonard, C., & Robert, A. (2016). International patterns of the public awareness of aphasia. International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders, 51(3), 276–284. https://doi.org/10.1111/1460-6984.12204

- Elman, R. J., Ogar, J., & Elman, S. H. (2000). Aphasia: Awareness, advocacy, and activism. Aphasiology, 14(5–6), 455–459. https://doi.org/10.1080/026870300401234

- Eysenbach, G. (2004). Improving the quality of web surveys: The Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys (CHERRIES). Journal of Medical Internet Research, 6(3), e34. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.6.3.e34

- Flynn, L., Cumberland, A., & Marshall, J. (2009). Public knowledge about aphasia: A survey with comparative data. Aphasiology, 23(3), 393–401. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687030701828942

- Graneheim, U. H., & Lundman, B. (2004). Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: Concepts, procedures, and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Education Today, 24(2), 105–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001

- Guo, Y. E., & Lim, M. S. (2018). Aphasia awareness in Singapore. Aphasiology, 32(sup1), 79–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038.2018.1485867

- Hill, A., Blevins, R., & Code, C. (2019). Revisiting the public awareness of aphasia in Exeter: 16 years on. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 21(5), 504–512. https://doi.org/10.1080/17549507.2018.1485742

- Kent, B. P., & Wallace, G. L. (2006). Aphasia awareness among the Honolulu Chinese population. Hawaii Medical Journal, 65(5), 142–147.

- McCann, C., Tunnicliffe, K., & Anderson, R. (2013). Public awareness of aphasia in New Zealand. Aphasiology, 27(5), 568–580. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038.2012.740553

- McMenamin, R., Faherty, K., Larkin, M., & Loftus, L. (2021). An investigation of public awareness and knowledge of aphasia in the West of Ireland. Aphasiology 35(11), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038.2020.1812047

- National Aphasia Association. (2016). Aphasia awareness survey. https://www.aphasia.org/2016-aphasia-awareness-survey/

- National Aphasia Association. (2020). Aphasia awareness survey. https://www.aphasia.org/2020-aphasia-awareness-survey/

- National Aphasia Association. (2022). Aphasia awareness survey. https://aphasia.org/2022-aphasia-awareness-survey-3/

- Noar, S. M. (2006). A 10-year retrospective of research in health mass media campaigns: Where do we go from here? Journal of Health Communication, 11(1), 21–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730500461059

- Patterson, R., Robert, A., Berry, R., Cain, M., Iqbal, M., Code, C., Rochon, E., & Leonard, C. (2015). Raising public awareness of aphasia in southern Ontario, Canada: A survey. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 17(2), 121–126. https://doi.org/10.3109/17549507.2014.927923

- Power, E., Thomas, E., Worrall, L., Rose, M., Togher, L., Nickels, L., Hersh, D., Godecke, E., O’Halloran, R., Lamont, S., O’Connor, C., & Clarke, K. (2015). Development and validation of Australian aphasia rehabilitation best practice statements using the RAND/UCLA appropriateness method. BMJ Open, 5(7), e007641. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2015-007641

- Rose, T. A., Worrall, L. E., Hickson, L. M., & Hoffmann, T. C. (2011a). Aphasia friendly written health information: Content and design characteristics. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 13(4), 335–347. https://doi.org/10.3109/17549507.2011.560396

- Rose, T. A., Worrall, L. E., Hickson, L. M., & Hoffmann, T. C. (2011b). Exploring the use of graphics in written health information for people with aphasia. Aphasiology, 25(12), 1579–1599. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038.2011.626845

- Rose, T. A., Worrall, L. E., Hickson, L. M., & Hoffmann, T. C. (2012). Guiding principles for printed education materials: Design preferences of people with aphasia. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 14(1), 11–23. https://doi.org/10.3109/17549507.2011.631583

- Simmons-Mackie, N., Code, C., Armstrong, E., Stiegler, L., & Elman, R. J. (2002). What is aphasia? Results of an international survey. Aphasiology, 16(8), 837–848. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687030244000185

- Simmons-Mackie, N., Worrall, L., Shiggins, C., Isaksen, J., McMenamin, R., Rose, T., Guo, Y. E., & Wallace, S. J. (2020). Beyond the statistics: A research agenda in aphasia awareness. Aphasiology, 34(4), 458–471. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038.2019.1702847

- Speakability. (2000). Phonebus survey (Speakability) [Unpublished data].

- Vuković, M., Matić, D., Kovač, A., Vuković, I., & Code, C. (2017). Extending knowledge of the public awareness of aphasia in the Balkans: Serbia and Montenegro. Disability & Rehabilitation, 39(23), 2381–2386. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2016.1226410

- Wallace, S. J., Worrall, L., Rose, T., Le Dorze, G., Cruice, M., Isaksen, J., Pak Hin Kong, A., Simmons-Mackie, N., Scarinci, N., & Gauvreau, C. A. (2017). Which outcomes are most important to people with aphasia and their families? An international nominal group technique study framed within the ICF. Disability & Rehabilitation, 39(14), 1364–1379. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2016.1194899