ABSTRACT

Background

The maintenance of therapy gains is critical for successful aphasia rehabilitation, a topic often overlooked in both research and clinical practice. For some people with chronic aphasia, maintaining therapeutic gains can be challenging, potentially resulting in diminished communicative function over time. Furthermore, maintaining therapy gains may necessitate consistent, deliberate effort; however, little is known about the factors supporting this process. People living with chronic aphasia and their family members may provide critical insights into the behavioural factors that impact the maintenance of therapy gains. Understanding these factors will be crucial for developing long-lasting, effective aphasia interventions.

Aim

In this study, we explored the perspectives and practices of people with chronic aphasia and their partners concerning the maintenance of gains from therapy for post-stroke chronic aphasia.

Methods & Procedures

Eight in-depth, semi-structured interviews were conducted, involving four people with chronic aphasia and four partners. We employed inductive thematic data analysis to identify emergent themes.

Outcomes & Results

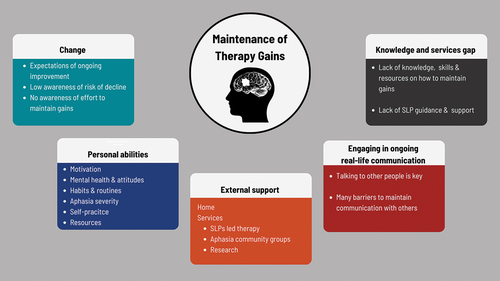

Five themes were identified that were perceived to influence the maintenance of gains made during aphasia rehabilitation. These were: 1) Beliefs about change: improvement, decline, and maintenance; 2) Personal abilities impact improvement and maintenance; 3) External support impacts improvement and maintenance; 4) Engaging in ongoing real-life communication impacts improvement and maintenance; and 5) Knowledge and services gaps in maintenance. The findings demonstrate the complexity and interaction of factors that potentially facilitate or hinder the maintenance of therapy gains in chronic aphasia.

Conclusions

People with chronic aphasia and their partners report having a limited understanding of the necessity and methods for maintaining therapy gains. They also describe a lack of services to support this. A lack of knowledge and services could hinder the ability to maintain therapeutic benefits. Our study also suggests various behavioural factors are involved in maintaining gains. Forming meaningful real-life communication routines may potentially optimise such gains. These findings highlight the necessity of placing maintenance at the heart of aphasia rehabilitation, informing future interventions and service development.

Introduction

Full language recovery is often a primary goal for individuals with post-stroke aphasia and their families (Wallace et al., Citation2017). Yet, for approximately 20% of stroke survivors living with chronic aphasia (≥6 months post-stroke) (Dijkerman et al., Citation1996; El Hachioui et al., Citation2013), this aspiration seems less attainable. Chronic aphasia typically has lasting negative implications for people with aphasia and their families. The aphasia literature underscores the multifaceted challenges faced by people with chronic aphasia and their families. These include communication difficulties, emotional and psychological effects, strained relationships, diminished social participation, employment and financial obstacles, difficulties in accessing suitable services and reduced quality of life (Baker et al., Citation2020; Code, Citation2003; Dalemans et al., Citation2010; Graham et al., Citation2011; Grawburg et al., Citation2014; Hilari et al., Citation2003; Morris et al., Citation2017; Rose et al., Citation2014; Wray & Clarke, Citation2017). The impact of aphasia extends beyond the individuals, impacting their families as well. The significant others of people with chronic aphasia are at risk of ‘third-party disability’, which may lead to mental health issues and social participation constraints (Grawburg et al., Citation2014; Howe et al., Citation2012).

Therefore, implementing effective interventions is essential to mitigate the lifelong adverse effects of chronic aphasia (Papathanasiou, Citation2017). Recent high-quality randomized controlled trials have shown the efficacy of intensive aphasia therapy (≥5 hrs. per week) in enhancing language function in people with chronic aphasia (Brady et al., Citation2016; Breitenstein et al., Citation2017; Rose et al., Citation2022). Nonetheless, the maintenance of gains, crucial for assessing intervention efficacy (Glasgow et al., Citation2019; Glasgow et al., Citation1999), is often overlooked (Menahemi-Falkov et al., Citation2022). Clinically effective intervention must not just offer immediate improvements, but also sustainable benefits over time (Breitenstein et al., Citation2021; Menahemi-Falkov et al., Citation2022).

Participation in interventions demands significant investment of time, effort, and resources. For individuals with aphasia, their families, and for the clinicians delivering these interventions, aphasia interventions need to yield long-lasting benefits and be cost effective to be worthwhile. However, a recent systematic review found that the majority of studies on intensive aphasia interventions mainly evaluated immediate post-therapy successes and overlooked the long-term maintenance of effects (Menahemi-Falkov et al., Citation2022). This incomplete evaluation may reduce the identification of cost-effective interventions that yield lasting benefits. Furthermore, a discrepancy exists between group-level and individual-level results of intensive therapy for chronic aphasia (Menahemi-Falkov et al., Citation2022). While group analyses uphold intervention effectiveness, only a third of participants show significant immediate improvement, and a mere 22% maintained significant gains at follow-up. These results indicate that maintaining aphasia therapy gains may require further effort or intervention.

Maintaining behavioural change is a significant challenge, with loss of gains common in both healthy populations and after aphasia rehabilitation (Glasgow et al., Citation1999; Menahemi-Falkov et al., Citation2022). The current model of care for aphasia rehabilitation primarily emphasizes therapy during the sub-acute phase, with insufficient services for people with chronic aphasia (Palmer et al., Citation2018; Rose et al., Citation2014). Consequently, many people lack ongoing support, interventions, and follow-up, potentially hindering their ability to maintain therapy gains.

The factors contributing to maintaining therapy gains in chronic aphasia remain unclear. Limited high-quality studies have explored key factors for long-term gains, primarily focusing on client demographics, stroke, aphasia-related factors, and therapy variables (Breitenstein et al., Citation2017; Kristinsson et al., Citation2023; Rose et al., Citation2022). However, there is extensive literature from behavioural and cognitive science on the factors underpinning maintenance of behavioural change in healthy populations (Bandura, Citation1986; Prochaska et al., Citation1992; Rothman et al., Citation2011; Ryan & Deci, Citation2000; Schwarzer, Citation2008; Verplanken & Orbell, Citation2003; Witkiewitz & Marlatt, Citation2009). Recently, Kwasnicka et al. (Citation2016) conducted a comprehensive review of 100 behavioural theories and identified six key elements associated with maintained health-related behaviour change. These are: motivation, self-regulation, resources, habits, and social, and environmental factors. What remains unclear is the applicability of these elements to individuals with chronic aphasia and their unique challenges in maintaining language and communication therapy gains.

The challenges experienced by people with chronic aphasia may be exacerbated by the inability to maintain therapy gains. The difficulty of maintaining therapy gains is particularly pronounced due to a lack of ongoing professional speech therapy support post-discharge (Rose et al., Citation2014). As individuals transition from supervised therapy to independently managing their condition (Voils et al., Citation2014), recognizing the multifaceted behavioural factors becomes crucial for promoting long-term gains. Understanding the role of communication, behavioural, and psychological challenges in maintenance may be essential for developing effective interventions and support services tailored to the unique needs of people with chronic aphasia and their families.

Aim

In this study, we aimed to explore the views and practices of people with post-stroke chronic aphasia and their partners regarding the maintenance of therapy gains, and identify enablers and barriers to improving and preserving gains achieved through therapy. A second study exploring the perspectives of speech-language pathologists about maintenance of therapeutic gains in chronic aphasia is reported elsewhere (Menahemi-Falkov, O’Halloran, Hill & Rose, under review).

Methods

Research paradigm and strategy

To gain an understanding of the experiences and practices of people with chronic aphasia and their families in maintaining therapy gains, we employed a descriptive qualitative approach (Bradbury-Jones et al., Citation2017; Bradshaw et al., Citation2017), within a social constructivist paradigm. Our choice of this paradigm was based on the belief that all knowledge is constructed through meaningful interaction with others and the environment (Crotty, Citation1998). Consequently, we collected data through in-depth semi-structured interviews, allowing people with chronic aphasia and their partners to discuss and share their views and practices with the researcher (Patton, Citation2015), and employed inductive thematic data analysis (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006; Braun et al., Citation2019). The study was reported using the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) checklist (Tong et al., Citation2007).

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was granted by the Human Research Ethics Committee, La Trobe University (HEC18006).

Participants

Individuals who were 18 years or older, had post-stroke chronic aphasia (at least six months post-onset), and their immediate family members were invited to participate in this study. Additionally, individuals with aphasia must have completed an intensive aphasia therapy program between 3 and 18 months prior to study enrolment, be a native English speaker and live in the community. A range of channels, including aphasia and stroke support organizations, and web and social media platforms were utilized to provide potential participants with information about the study. The researcher contacted individuals who expressed interest, and subsequently provided them with more detailed information. Formal consent was obtained after verifying the prospective participant’s ability to comprehend the information, which was assessed through a series of yes/no questions and the implementation of supportive communication strategies.

A total of eight participants were recruited and interviewed, including four people with chronic aphasia and four family members (partners). This comprised three couples (a person with aphasia and partner), one individual with aphasia without a partner, and one partner of a person with aphasia not included in the study. For the two participants who did not participate as a couple, one partner was unable to participate due to cognitive problems, and one person with aphasia refused to take part. All participants had English as their first language and were married.

Of the four people with aphasia, all were employed at the time of their stroke two retired post-stroke, and two changed jobs due to the illness. Two of the four partners were self-employed and explained that following their partner’s stroke, they had to either return to work or take on additional work responsibilities. One partner could not work due to illness, and another was already retired. presents the participants’ characteristics.

Table 1. Participant characteristics

Research method

We conducted semi-structured in-depth interviews to generate detailed, rich, deep, and person-centred information (Kvale, Citation2015). Three versions of the topic guide were developed to facilitate the interview process (people with aphasia, aphasia-friendly, and family members; see Appendix 1). Interview topics included participants’ views and practices regarding maintenance of therapy gains, including how therapy gains have been maintained over time, and the methods people employed to maintain therapy gains. Finally, the factors that facilitate or prevent people with chronic aphasia from maintaining and implementing therapy gains were investigated.

Given that this was an exploratory study investigating personal experiences, the researchers’ professional backgrounds in Speech-Language Pathology (SLP) with extensive experience in aphasia therapy influenced the interview guide. Interviews had a flexible format (order of questions, wording, prompts), allowing the researcher to follow the participants’ line of thought. Interviews with each participant were conducted between July 2018 and January 2019 at the participants’ residences.

The first author (M.MF) conducted five interviews, which involved three couples, one individual with aphasia, and one partner. The couples were interviewed together upon their request. The length of the interviews ranged from 88 to 132 minutes, resulting in 184 single-spaced transcript pages. A video camera and a digital audio recorder were used to record the interviews. Interviews were transcribed, and pseudonyms were used to protect the participants’ anonymity. Field notes were taken to complement the transcripts.

M.MF, a female speech-language pathologist and researcher with extensive experience in aphasia rehabilitation, conducted all interviews as part of her PhD dissertation. M.MF disclosed the purpose of the study to the participants, with no prior relationship existing between the researcher and the participants. The interview topic guide questions were collaboratively designed by the research team as open questions to reduce bias.

Data analysis

M.MF conducted the analysis, which co-author R.O reviewed during the analysis process. To enhance the rigour of the analysis and interpretation of the data, we used strategies such as reflexivity, creating an audit trail, and discussing themes and sub-themes with all research team members throughout the analysis process. All data were stored and managed using the software package NVivo 12 Plus (QSR International Pty Ltd, 2020). An inductive (data-driven) thematic analysis was used according to the six phases of thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006; Braun et al., Citation2019). The six phases include: 1) Familiarization, which involves repeated transcript readings and allows the researchers to notice interesting features in the data; 2) Generating codes, where chunks of data are linked to short descriptive labels; 3) Constructing themes, which organizes codes to discern potential patterns; 4) Revising themes, through an iterative process ensuring themes reflect both data extracts and the entire dataset; 5) Defining and naming themes, which is focused on clarifying and summarizing each theme’s essence; 6) Producing the report, which offers a final check to see if the themes work, individually and as part of a conceptual whole (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006; Braun et al., Citation2019).

Results

We identified five key themes and thirteen sub-themes that provide insights into the views and practices of people with chronic aphasia and their partners in maintaining therapeutic gains. The five themes are: 1) Beliefs about change: improvement, decline, and maintenance; 2) Personal abilities impact improvement and maintenance; 3) External support impacts improvement and maintenance; 4) Engaging in ongoing real-life communication impacts maintenance; and 5) Knowledge and services gaps in maintenance. depicts the five themes.

Theme 1. - Beliefs about Change: Improvement, Decline and Maintenance

This theme focuses on the perspectives of people with chronic aphasia and their partners concerning improvement, plateau and decline, and maintenance of language post-stroke.

Improvement

All participants strongly believed that language improvement was possible even years post-stroke. “It (i.e., language abilities), it’s increasing all the time” (Jerry - PWA [Person with Aphasia]); “You can go on for ten years and you can still keep improving (i.e., language abilities) bit by bit by bit” (Ally - Partner). Both people with aphasia and their partners expressed a range of hopes for the future, including enhanced independence, leisure time, relationships, work, communication abilities, and normality. “I just wanna be normal; Be everything I want it to be” (Liam - PWA).

People who were two to three years post-stroke and their partners not only believed that positive change is possible, but they explicitly linked this belief to their motivation to practice and undergo therapy. All participants with chronic aphasia and their partners expressed a willingness to do whatever it takes to aid the rehabilitation process. “I’ll do anything. I’ll do anything”. (Kate - PWA). However, they also emphasized the importance of seeing tangible benefits from their efforts. Therefore, participants only invested time and effort in activities they deemed useful and worthwhile. “It helps you to feel good that you’re doing something useful … doing the right thing” (Kate - PWA). Similarly, participants did not engage in communication activities considered ineffective, impossible to perform, emotionally challenging, unenjoyable, or inconvenient. “You’ll probably say it’s boring. You’re probably even not stimulated with it. (Hugo - Partner).

Participants believed that ongoing improvement required challenging, intensive impairment-based therapy under the guidance of a speech therapist. When asked to reflect on their abilities before, immediately after, and long after intensive aphasia therapy, both people with aphasia and partners reported that the person with aphasia’s communication had improved. However, they described a general improvement or better naming ability. They did not report any changes in their communication activities or participation in everyday communication.

Plateau and decline

Only partners described outcomes in terms of plateau and decline. “Since the trial, yeah, things might have faded … it doesn’t sort of stick in the brain” (Mike - Partner). Partners believed that plateau and decline were associated with withdrawal from speech therapy, reduced home practice, and low communication use. “I do feel there has been a bit of a decline since he’s stopped his speech therapy” (Erin - Partner). Partners also reported that if people with aphasia thought their communication could not improve further, it might lead to reduced motivation, practice, and further decline.

Maintenance

Participants rarely used the term maintenance. When asked about their practices and beliefs concerning maintenance, they expressed strong concerns about their insufficient knowledge and skills in this domain. Nevertheless, some participants acknowledged that aphasia is a lifelong condition that necessitates maintenance. “You had a brain injury; you have to keep working at it. It’s not going to go away.” (Erin - Partner). “It’s over and over and over and over” (Liam - PWA). Some participants emphasized the importance of ongoing hard work for the brain, as they believed that the more the brain is exercised, the better communication becomes. One partner highlighted the common saying, “use it or lose it,” to emphasize the need to continually exercise and utilize the brain’s capabilities. “Don’t they say, you don’t use it, you lose it … And that’s exactly the same with the words, that the more – often that wo-word is used, the better it comes” (Erin - Partner).

Theme 2. - Personal Abilities Impact Improvement and Maintenance

This theme explores the influence of personal abilities on improvement and maintenance of communication skills in chronic aphasia. Sub-themes include motivation, habits and routines, mental health, self-practice, and resources.

Motivation

Intrinsic motivation, specifically participating in meaningful, enjoyable, valued activities, was believed to support people with chronic aphasia to improve and maintain gains. “That was the other thing we wanna try to get – help get back. That might be another round way of getting back the speech. Talking about art in some way.” (Hugo - Partner). Intrinsic motivations were often derived from hobbies, enjoyable or valued relationships and past employment. “Well, a couple therapy is still my passion, absolutely, and what I’d like to do is to talk well enough to work with couple therapy with aphasia” (Kate - PWA).

However, some participants were unsure about what would keep people with chronic aphasia motivated over the long term. Many participants reported losing motivation over time, particularly for self-practice. Reductions in motivation stemmed from time passing, the belief that progress was unachievable, or a waning interest in activities or therapy. “The thing is with her; she will do something for a certain period of time, and then it will drop off” (Mike - Partner).

Habits and routines

Participants discussed a variety of daily routines that they considered to help or hinder gains and maintenance. Routines considered beneficial included reading the paper daily, talking to people while taking a walk, babysitting grandchildren, meeting family and friends regularly, going shopping, checking sports results, participating in aphasia or stroke groups (e.g., an aphasia choir), and engaging in hobbies that promote social interaction, as these were seen as helpful for maintaining ongoing communication. Interestingly, rather than specifically being aimed at maintenance, most routines were aimed at seeking enjoyment and value.

Habits hindering the maintenance of gains were also discussed, including avoiding speaking, being inactive and homebound, partner’s overcompensation or “talking for” behaviours, and people with chronic aphasia’s dependency, which limited independence and communication. Few partners acknowledged the need to modify their habits to help people with aphasia increase communication usage.

Mental health and attitude

Participants considered good mental health, a positive attitude, confidence, an outgoing personality, and being active and proactive as key factors in improving and maintaining long-term gains. They believed that initiating communication and being open to talking to anyone, especially beyond close family members, provided increased communication opportunities and practice. “If she’s in a room of people, she will attempt to communicate with them as best she can” (Mike - Partner).

Conversely, participants reported that depression or a lack of confidence hindered communicating. Communication breakdowns could result in low confidence, anger, anxiety, nervousness, and frustration in interpersonal interactions, leading to avoidance of speaking or group activities. “Then the more tired he gets, the worse it gets, but his emotions affect his speech so much as well. So, once you add some nervousness, anxious, anger, you know, sadness, they all affect his speech” (Erin - Partner).

Aphasia severity

Participants believed that a milder aphasia would lead to greater communication use and maintenance. “If his speech was improved, I guess then he would more just speak to people” (Erin - Partner). They viewed a person’s motivation to improve and maintain gains as directly linked to their progress, hope, and the effectiveness of practice. Participants considered communication disabilities as major barriers to activity and participation, including independence, work, life roles, relationships, leisure, and safety. They attributed reduced real-life communication use to a range of language impairments.

For example, naming difficulties led one person to be charged higher waste recycling fees due to the confusion between the words “grass” and “glass,” which led to anxiety and frustration. Semantic and grammatical errors limited the use of text messages for maintaining friendships and work. Receptive problems, such as difficulty following a group’s rapid communication pace or changing topics, hindered participation in groups and leisure activities, including those involving little communication, such as swimming squad. Finally, a participant with mild aphasia reported that her communication disability had led to her inability to work and estrangement from her daughter.

Self-practice

Self-practice was deemed crucial for successful rehabilitation for people with chronic aphasia during and after therapy discharge. Speech-Language Pathologists (SLPs) commonly recommended aphasia software, and some participants found this software advantageous, providing practice opportunities especially when no one was available for conversation. However, some participants did not believe practice via aphasia software enhanced their communication. “It’s not talk-talking to people” (Jerry - PWA).

Sustaining self-practice was viewed to rely on motivation, structure, time commitment, rote learning, individualized drills, knowledge of performing tasks, monitoring, and feedback. Initially, during their rehabilitation, people with chronic aphasia were willing to practice anything recommended by the SLP. Then, post-therapy discharge, they tried to continue using apps and materials from their rehabilitation programs. However, without an SLP’s involvement, selecting suitable apps and drills was difficult, and lack of feedback made them doubt their efforts.

Some partners reported attempting to assist people with aphasia to maintain their self-practice efforts but felt they lacked the necessary skills and knowledge to do so effectively. Despite their lack of formal training, partners attempted to guide on what and how to practice. “I also give him homework” (Ally - Partner). Some partners, for example, suggested reading aloud instead of silently, or using specific apps, tasks, games, and practice methods. They also encouraged continued use of impairment-based aphasia apps, even when unsure of their effectiveness.

Nevertheless, some partners expressed dissatisfaction with the people with chronic aphasia’s level of commitment, time investment, and practice preferences. Partners wanted the person with chronic aphasia to either take more responsibility for their self-practice or for someone else to supervise it. They expressed concerns about relationship strain, technological challenges, and a lack of time and knowledge.

Over time, the lack of progress from repetitive tasks led to disinterest and demotivation in people with chronic aphasia, making them more selective and less willing to invest in ineffective self-practice. This often resulted in reducing or discontinuing practice, as they found it uninspiring and ineffective for communication skill improvement. “We tried therapy type various apps, but we really couldn’t seem to maintain that” (Hugo - Partner); “I stopped it cause it seemed to be not really effective”. (Kate - PWA); “Yeah, it didn’t (help)” (Libi - PWA).

As people with aphasia’s life and communication skills changed, new challenges emerged for them and their families. Participants highlighted the importance of ongoing professional individual guidance and support for successful self-practice, regardless of available therapy apps and materials.

Resources

People with aphasia were less likely to focus on maintaining gains when life issues arose, for example, when they or a close family member experienced significant life or medical issues. “Life gets in the way of everything… So, as far as practicing anything she might have got out of the (research) trial, it wasn’t a priority” (Mike - Partner). Partners expressed limited time and competing life tasks as barriers to focusing on maintaining gains. Finally, the lack of funds and the high cost of speech therapy prevented participants from getting additional treatment, which most believed was necessary to maintain motivation, improve, and sustain achievements.

Theme 3. - External Support Impacts Improvement and Maintenance

This theme emphasizes the vital role of external support in maintaining therapy gains for people with chronic aphasia. Professional services, although crucial, may not always be available, especially during the chronic phase. In such situations, family support becomes indispensable, particularly when individuals face severe aphasia, executive function issues, or mental health problems.

Services and methods; therapy, research, and aphasia community groups

People with chronic aphasia and their partners believed in the crucial role, value, and effectiveness of SLP-led aphasia therapy for improving and maintaining communicative gains. The SLPs who were applauded for encouraging clients to push beyond their limits played a crucial role, particularly during the initial years post-stroke, empowering clients to “keep trying” (Liam - PWA), work harder, and achieve more. For example, one person with mild aphasia learned to text her grandchild in therapy, which helped them reconnect.

Participants valued professional therapy programs for providing personalized therapy tailored to specific deficits, real-life needs, and meaningful goals. They appreciated the individual guidance, structure, motivation, and rote learning and valued the tools, practice ideas, monitoring, and feedback. This motivated people with chronic aphasia to maintain their efforts. “It’s effective ‘cause I’ve got the-the-the feedback” (Jerry - PWA).

Participants believed that additional therapy could boost improvement and maintain communication abilities. (he told me),” I think dad needs to do some more therapy or more practice. It seems like he needs to do another (research) trial now, to give him another little boost” (Erin - Partner). For those lacking access to therapy or resources, participating in research studies that offered therapy emerged as a valuable alternative method to improve their communication abilities. Varying outcomes were reported, including one participant who improved and even received a community therapy extension. However, other participants did not experience significant gains or benefits. “It didn’t help, not a lot … I-I don’t think he got much out of it” (Ally - Partner).

Community groups were also a common service utilized by most participants with chronic aphasia, including aphasia support or communication groups, choir, art, coffee meet-ups, and physical exercise. Participants appreciated the inclusive, safe atmosphere of disability groups, allowing for participation and communication with people with similar experiences. Most participants, however, did not identify maintaining or improving communication skills as the driver for attending these activities. Only one partner of a client with severe aphasia found aphasia choir beneficial. “The biggest difference I’ve noticed is with the singing … she seems to be getting more into thinking – thinking of things to say” (Hugo - Partner). Additionally, participants with aphasia would exit groups if they did not benefit or enjoy them, if their participation inconvenienced their partner, or faced life or medical challenges. “Oh, she went in for a procedure and that sort of set her back, and she never really got – got back into it … ” (Hugo - Partner).

Home support

Family members, particularly partners, played a crucial role as communication partners for participants with aphasia. They felt responsible for enabling communication, providing companionship, and preventing loneliness. Immediate family members were more aware of the communication needs of people with aphasia compared to those outside the household and made efforts to assist by initiating conversation or allowing sufficient time to respond. They also served as intermediaries between the person with aphasia and the environment, in social or work-related situations, providing necessary information and enabling active participation. For instance, one wife helped her husband, who worked as a gardener, communicate with his clients.

Partners and people with aphasia described doing many routine activities together, usually organized by the partner or available locally (e.g., a pizza night at a retirement village). Partners significantly contributed to managing, caring, planning, initiating, organizing, and participating in the daily tasks, activities, and social interactions of their person with aphasia. “I always try and, um, uh, get Libi go meet other people” (Hugo - Partner). They searched for community activities, therapy, and caregivers for the partner with aphasia. Partners took ownership of tasks that people with aphasia did before the stroke and could no longer fulfill. Only one person with mild aphasia whose husband had a significant health issue described organizing her life independently.

Additionally, as noted previously, partners took a therapeutic role, especially during the first few years post-stroke. They took responsibility for ensuring that home practice was completed. Partners provided motivation, guidance, reminders, monitoring, feedback, and encouraged ongoing communication use. “I said to him, just keep talking. No matter what, keep talking” (Ally - Partner); However, partners’ lack of skills and knowledge could also hinder therapy gains, due to unhelpful guidance, expectations, dissatisfaction, and tension.

Some partners’ communication behaviours were described as potentially unhelpful. For example, people with aphasia reported that they could overcompensate by constantly being present as a backup, checking for communication breakdowns and speaking for the person with aphasia, potentially limiting communication independence. One partner chose not to use funded caregiver hours as he was unsure of his partner’s ability to spend time without him. They also noted that they changed topics without sufficient signalling, and underestimated people with chronic aphasia’s ability to independently communicate with others, including not appreciating non-verbal skills as communication. In the interview, few partners recognized the need to change their ineffective communication strategies.

Theme 4. - Engaging in Ongoing Real-life Communication Impacts Maintenance

This theme highlights the critical role of ongoing real-life communication in maintaining therapy gains, and the challenges and opportunities that affect integrating communication into daily life.

Talking to other people is key to maintaining and improving therapy gains

While not suggesting it spontaneously, all participants agreed that talking to others was crucial for maintaining therapy gains, with daily communication seen as a form of practice and self-expression. “Talk to a friend like that. it’s practice, its conversation, its self-expression” (Kate - PWA); “Amm amm … better talk, talk” (Libi - PWA). Real-life communication was enabled by the person’s willingness to interact despite their disability and the listener’s interest, understanding, and patience. Additionally, enjoyable communication activities available at the local community, retirement villages, cruises, and caravan parks, such as art classes and sharing breakfast with others, presented opportunities to communicate with people who were often more prepared to engage with people with aphasia. While some participants believed there were sufficient opportunities to maintain communication, others discussed multiple barriers.

Barriers to maintaining communication with others

Participants discussed various challenges that prevented people with aphasia from maintaining real-life communication, including limited communication opportunities, difficulty coping with communication breakdowns, lack of knowledge, and poor mental health.

People with aphasia reported limited communication opportunities due to small social networks, lack of community activities, and difficulty learning and using communication devices and apps (e.g., audio and video calls, text messages, emails, and social media). This hindered regular communication with family and friends who lived at a distance, resulting in many people with aphasia interacting only in person. There was a lack of community activities suitable for people with aphasia and some disliked participation in aphasia or disability community activities (e.g., aphasia support groups, men’s shed). Fees for activities and transportation costs were additional barriers to participation. Consequently, close family members’ involvement and presence became essential for people with aphasia, limiting communication opportunities when family members were unavailable. “When I go off to work for a day, I don’t know who he would even talk to with the whole day” (Erin - Partner).

Additionally, communicating in a group or with unfamiliar people posed many challenges. Unfamiliar people were usually unaware of aphasia and lacked knowledge, interest, patience, and understanding. Although people with aphasia wished to participate in social activities, communication was challenging due to noise, pace, diversity of topics, and communication breakdowns. This difficulty increased in larger groups, resulting in some people stepping back. “I wanna have-have a laugh and joke, but by the time I’ve worked it out, there are on the-the-the third or fourth” (Liam - PWA). Moreover, communication breakdowns and people’s reactions to them led to significant negative emotions including anxiety, stress, and low self-esteem, which led to the avoidance of speaking. Partners tried to assist but often considered it to be impossible.

Whilst some participants reported high activity levels, these activities were characterized by limited communication and social participation opportunities. Participants attributed this mismatch to the many activities they did on their own. For example, some people did a lot of solo sports (e.g., walking, swimming) and work (e.g., mowing the lawn, repairing a tractor) that do not require communication.

Theme 5. - Knowledge and Services Gap in Maintaining Therapy Gains

This theme highlights the knowledge gap for people with aphasia in maintaining therapy gains, including limited understanding of the need to maintain gains, insufficient knowledge and skills for developing communication routines and habits, lack of guidance and post-treatment support, and ineffective use of aphasia apps.

Participants showed a greater emphasis on making progress rather than maintaining it. Only a few expressed concerns about the importance of continuing to work on communication skills to maintain therapy gains. For instance, one partner noted that her husband may not fully grasp the need to continue working on his communication skills. “I don’t know that Liam realizes that he does have to keep working” (Erin - Partner).

All participants described a significant lack of knowledge, skills, ideas, and resources on how to maintain therapy gains. “I’ve got no skills to maintain – to keep that going. So, you fall back into the ways that you were before” (Mike - Partner). Many participants noted that treatment programs often provide only general recommendations to continue practicing and do not address the development of individual maintenance or communication habits. This leaves participants with limited knowledge and skills in maintaining progress. Consequently, many participants return to their old routines and do not intentionally focus on maintaining any achievements.

Participants found the lack of knowledge on how to maintain communication skills frustrating: “The biggest frustration for me was to get the best care that didn’t cost too much money … I didn’t (know how to maintain). That was the trouble … I just don’t know what would work, what can I “(do)(Kate - PWA). One partner suggested the provision of weekly ongoing support to maintain gains, possibly through aphasia groups.

Participants also identified a gap in their skills and knowledge concerning research-based therapy studies. They valued research studies but struggled to maintain therapy gains afterwards due to a lack of skills, knowledge, and resources. “I didn’t have them, the rhinoceros, and the elephant” (i.e., image stimuli) (Liam - PWA). Moreover, partners expressed limited involvement during research therapy studies, which resulted in a lack of awareness of the people with aphasia’s individual communication progress and how to maintain this improvement: “I will drop Cathy off and pick her up. So therefore, I’ve got no skills to deal with whatever Cathy was – gleaned from the (research) trial”. (Mike - Partner).

As noted previously, participants also reported that they lacked knowledge about self-practice, struggling to select appropriate apps and drills for self-practice. As a result, many noted that they experienced a decrease in practice frequency, or they stopped altogether. “Libi did not really seem want to get into it sort of it. Come home maintain it” (Hugo - Partner). Years after their stroke, individuals with chronic aphasia still searched for advice on the most effective aphasia software to improve or maintain their capabilities. “If you could tell me what would be the best (app) on the iPad about the best that would match where I’m at the moment, that would be brilliant” (Kate - PWA). This highlights the need for ongoing professional support and guidance to help individuals with chronic aphasia practice effectively and maintain progress.

Discussion

This study explored the perspectives and practices of people with chronic aphasia and their partners in maintaining therapy gains, and the enablers and barriers to improving and preserving gains achieved through therapy. We identified five main themes: Change, Personal abilities, External support, Engaging in ongoing real-life communication, and Knowledge and service gaps. These themes illuminate factors that are believed to facilitate or hinder the maintenance of behavioural therapy gains in chronic aphasia, a complex and under-researched area.

While early post-stroke improvements are driven by spontaneous recovery and therapy, ongoing improvement in the chronic phase usually requires deliberate effort (Menahemi-Falkov et al., Citation2022). Therapy can initiate functional changes and enhance client satisfaction. However, transitioning these new behaviours to an everyday environment presents challenges, particularly due to the lack of professional services for those with chronic aphasia post-discharge (Rose et al., Citation2014). As the focus shifts from supervised intervention to the client taking control of maintaining gains (Voils et al., Citation2014), it is critical to understand and address the multifaceted behavioural factors of personal beliefs, motives, abilities, resources, external support, and knowledge that were found to be essential for promoting long-term gains in non-brain damage populations (Kwasnicka et al., Citation2016).

Knowledge gap

This study highlights a critical knowledge gap among people with chronic aphasia and their partners, which may have significant implications for maintaining therapy gains. All participants noted that a lack of information and guidance hindered their awareness and understanding of how to maintain therapeutic gains. This knowledge gap could cause participants to undervalue therapy maintenance, negatively impacting attitudes and motivation, which are crucial for behavioural change (Schwarzer, Citation2008; Sheeran et al., Citation2016) and may be important for maintaining therapeutic gains in aphasia as well. People with chronic aphasia reported anticipating slow but ongoing improvement, which could lead to neglecting the risk of decline.

Belief in slow, ongoing improvement might obscure the potential risk of decline and the need for active efforts to maintain therapeutic gains. After therapy, people with chronic aphasia have reported returning to their pre-therapy habits, often without making a conscious effort to maintain the gains they made. Participants attributed this to barriers, including insufficient information, resources, and skills for maintenance. These findings and previous research about self-management (Nichol et al., Citation2022) underscore the need for SLPs to provide more information and education before discharge to increase awareness among people with chronic aphasia and their partners about decline risks and potential solutions.

While knowledge may be crucial for maintaining gains, it is unlikely to be the sole determinant of long-term behavioural changes. Identifying the potential relationships among behavioural factors that facilitate maintaining aphasia therapy gains is necessary.

The role of motivation and meaningful activities in maintenance

Maintenance in chronic aphasia may necessitate intentional, persistent engagement (Menahemi-Falkov et al., Citation2022). If this is the case, individual competencies will be vital. Emotional struggles and life constraints were thought to pose barriers to maintaining communication. In contrast, good mental health, positivity, confidence, proactivity, and reduced language impairment were identified as key to improving and maintaining communication gains. Research indicates that psychological well-being significantly impacts post-stroke social participation and autonomy (Fallahpour et al., Citation2011), which are essential for sustained engagement and motivation to maintain behaviours over time (Ryan & Deci, Citation2000).

Motivation is a crucial component of aphasia rehabilitation, often used as a discharge criterion in therapy decision-making (Hersh & Ciccone, Citation2016; Maclean et al., Citation2002). However, research on motivation in post-stroke aphasia remains scant (Biel et al., Citation2017; Weatherill et al., Citation2022), and more research is needed to fully understand its complexities and long-term impact. Our study emphasizes that motivation is believed to play a pivotal role in initiating and maintaining behavioural change. We found that external motivations, such as expectations of improvement and adherence to SLP guidance, are perceived as significant drivers to initial change. These motivators are ‘external’ as they aim for separate outcomes or rewards, not deriving inherent enjoyment from the activity itself, which may not be sufficient to maintain post-therapy gains (Deci & Ryan, Citation2000; Ryan & Deci, Citation2000).

Our findings indicate that people with chronic aphasia are more likely to maintain long-term intrinsic motivation to use language through meaningful activities, relationships, and experiences that align with their self-identity and core values. The inherent pleasure or value in these engagements, reflecting personal beliefs, is more likely to encourage sustained involvement despite communication challenges and likely lead participants to favour meaningful activities and avoid those perceived as ineffective or unenjoyable.

This is consistent with behavioural change research (Kwasnicka et al., Citation2016) and aphasia literature, demonstrating that individuals are more likely to engage in value-driven activities (Dalemans et al., Citation2010; Lanyon et al., Citation2019; Nichol, Wallace, Pitt, Rodriguez, & Hill, Citation2022) which facilitate enhanced achievement, purpose, engagement, confidence, persistence, and well-being (Ryan & Deci, Citation2000; Wray & Clarke, Citation2017), irrespective of competence and self-efficacy (Ryan & Deci, Citation2000). Additionally, our findings resonate with the salience principle of experience-dependent neural plasticity, which suggests that meaningful experiences can drive neural changes (Kleim & Jones, Citation2008; Raymer et al., Citation2008).

Interestingly, participants did not describe these activities as directly enhancing language or communication. Instead, they engaged in them because they found them fulfilling and enjoyable. This indicates that relevant stakeholders may not fully recognize the benefits of these activities in maintaining communication therapy gains. Engagement in real-life meaningful activities also likely requires self-regulation. This key skill facilitates deliberate efforts, self-practice, and transitions from therapy to everyday communication.

The dynamic interplay of personal abilities and external support in maintaining intentional efforts

While the study participants did not explicitly discuss self-regulation skills, they deemed self-practice essential for rehabilitation success, both during and following therapy. The noticeable recovery in the early stage of therapy, which may have been associated with impairment-based therapies and home practice, likely reinforced this belief. Participants emphasized the importance of motivation, structured individualized drills, time commitment, monitoring, and feedback in maintaining self-practice. These elements support self-regulation, a skill set crucial for maintaining behavioural change and closely aligned with executive functions (Hofmann et al., Citation2012; Kwasnicka et al., Citation2016). Self-regulation is particularly vital when psychological and physical resources are limited. It facilitates the transition from automatic to goal-directed behaviour through planning, monitoring, reinforcement, and the adoption of effective coping strategies (Kanfer & Karoly, Citation1972).

Post-therapy, self-regulation may become crucial for people with chronic aphasia, influencing the ability for self-practice and real-life communication. These skills are essential when behavioural changes are not automatic (Hofmann et al., Citation2012; Kwasnicka et al., Citation2016) and during times of low motivation, challenging tasks, and unfamiliar situations (Kwasnicka et al., Citation2016). Additionally, self-regulation facilitates coping with barriers, frustration, and stress, and enables adjustment to strategies during communication breakdowns. However, people with chronic aphasia often experience cognitive impairments impacting executive functions (Purdy, Citation2002) and self-regulation skills. Recent studies highlight executive functions as a predictor of aphasia therapy gains (Simic et al., Citation2017) and post-stroke participation (Park et al., Citation2015; Skidmore et al., Citation2010).

Participants noted they often initially engaged in impairment-based practices, encouraged by their partners and SLPs, which were considered to maximize communication abilities. Increased motivation and professional support during this phase enhanced self-practice. Despite their desire for continued professional support for rehabilitation and maintaining therapy gains, they faced several challenges after therapy ended. These included communication barriers, emotional struggles, life hurdles, reduced motivation, and a lack of available professional services for chronic aphasia. The lack of personalized advice and support led some participants to view repetitive practice as emotionally challenging and ineffective, leading to discontinued self-practice. Notably, the struggle of maintaining therapy gains without support, also observed in chronic disease management (Barlow et al., Citation2005), may be exacerbated by the lack of professional services for chronic aphasia (Palmer et al., Citation2018; Rose et al., Citation2014).

Our findings indicate that partners are believed to play a critical role in bridging the self-regulation gap, especially when individuals’ resources are diminished, or professional support is lacking. Partners, serving as external motivators, described significantly contributed by assisting in planning, initiating, organizing, monitoring, removing barriers and guiding home practice, daily tasks, and social interactions. However, they also reported that overreliance on partners also imposed burdens and potentially hindered the independence of people with aphasia. Furthermore, they expressed concern that partners’ limited expertise may result in suboptimal guidance, potentially leading to dissatisfaction, strained relationships, and negative emotions. These findings highlight the need for a balanced approach that fosters independence without overburdening partners, and the need to find supports beyond partners.

People with chronic aphasia reported receiving support from partners and a desire for more involvement in real-life communication activities, which aligns with previous aphasia research (Brown et al., Citation2012; Cruice et al., Citation2006; Dalemans et al., Citation2010; Wallace et al., Citation2017; Worrall et al., Citation2011). However, these individuals also discussed tendencies to avoid speaking and reduced social participation. To enhance engagement, the establishment of communication habits and routines might be a viable strategy, especially when self-regulation proves challenging.

Maintenance enhancement: leveraging habits, routines, and supportive environments

Participants unanimously agreed that regular communicative interactions in real-life situations are vital for maintaining therapy gains. They viewed daily communication as both practice and a form of self-expression. Establishing these communication habits and routines may be vital for this population, given their unique cognitive, physical, and psychological challenges. Habits and routines, requiring less cognitive effort and conscious processing, are generally more efficient than self-regulation (Arlinghaus & Johnston, Citation2019; Kwasnicka et al., Citation2016).

Participants highlighted that unwanted habits such as avoiding speaking, inactivity, and partners’ overcompensation hinder the maintenance of effective real-life communication. Though forming new habits can support behavioural maintenance, breaking deep-rooted unwanted habits (e.g., avoidance of speaking) can be highly challenging (Bouton, Citation2000) . Furthermore, barriers include generic therapy instructions that lack personalization, difficulties in managing communication breakdowns, mental health issues, and limited opportunities for engagement.

Study participants identified supportive environments as key to enhancing communication for people with aphasia, providing them interaction opportunities with empathetic individuals. Previous research affirms that familiar, supportive environments play a crucial role in maintaining communication use and behavioural changes (Kwasnicka et al., Citation2016). For instance, it is likely easier for this population to maintain a new strategy within familiar settings and with trusted people than in unfamiliar or unsupportive ones. The importance of social and environmental factors in behavioural maintenance underscores the need to consider these aspects in intervention design and education resources about maintenance.

Ultimately, our findings resonate with the principles of Person-Centered Care emphasizing the tailoring of interventions according to clients’ preferences, values, and overall life aspects (Håkansson Eklund et al., Citation2019). Extending beyond the functionally focused traditional Patient-Centered Care, advocates for a meaningful life reflecting personal goals through engaging and meaningful activities (Håkansson Eklund et al., Citation2019). Our results indicate that greater knowledge, prioritizing intrinsic motivations, engaging in meaningful activities, and establishing habits within supportive environments may be crucial for optimizing therapy gains in chronic aphasia.

Clinical implications

This work revealed a significant gap in knowledge, skills, resources, and services regarding the maintenance of therapy gains in chronic aphasia. Therefore, it is important for stakeholders to understand the potential decline in therapy gains without continued communication use or practice. This study identified various behavioral factors, such as motivation, self-regulation of skills and habits that may either hinder or facilitate this process. As such, clinicians should take these factors into account, carefully assessing each client’s unique situation, capabilities, and challenges. Clinicians should also consider implementing proactive, individualized strategies to maintain long-term treatment gains. These strategies may encompass enhancing awareness around the importance of active maintenance and assisting clients and families to establish meaningful, enjoyable communication routines and habits within a supportive environment.

Limitations and future directions

We recognise that our findings may be influenced by the unique beliefs and experiences of the people with chronic aphasia and their partners participating in this study. Additionally, the study may exhibit selection bias, as more motivated individuals are likely to consent to participate. Moreover, our relatively small sample size may limit the diversity of perspectives captured. Thus, the results should be interpreted carefully, as they may not represent the views of all people with chronic aphasia and their families, especially in different models of care, cultural or geographical contexts.

Maintaining therapy gains is a crucial measure of therapeutic success and deserves a prominent role in aphasia rehabilitation research and clinical practice. Our research highlighted a substantial deficiency in the availability of knowledge, skills, resources, and services, which hinders individuals with chronic aphasia from maintaining their therapeutic progress. As such, it is crucial to develop educational packages, intervention programs, and services specifically addressing this critical issue.

Considering this is the first study on an under explored topic, further research is needed to identify the variables that people with aphasia and their close others believe impact maintenance during and following therapy. Currently, predictions of therapy response are typically tied to the client’s aphasia severity, brain damage characteristics, and age. Consequently, research should broaden its focus beyond biological and clinical factors and examine the contribution of behavioral factors to maintenance, such as intrinsic motivation, self-regulation skills and meaningful communication routines and habits.

Finally, when designing interventions for maintaining therapy gains, it is crucial for researchers and clinicians to consider that self-management and maintenance require high-level self-regulation skills, which are often impaired in people with chronic aphasia due to executive function difficulties and depleted psychological and physical resources.

Conclusions

The maintenance of therapy gains, while essential for the lives of people with chronic aphasia, is currently under-addressed in both research and clinical practice. People with chronic aphasia and their partners identified a significant lack of essential knowledge, skills, resources, and specific professional services in this area. This gap likely affects their beliefs and practices, leading to an overemphasis on continuous improvement while overlooking the need to sustain therapy gains.

Maintaining therapy gains in chronic aphasia is a multifaceted process, potentially requiring sustained, intentional effort. Our study provides valuable insights into the complexities of the intertwined roles of personal abilities, along with cognitive, physical, and psychological resources, which are often reduced in this population. Given the scarcity of personal resources and abilities, professional SLP guidance could be beneficial. However, due to its limited availability, partners often step in to assist. Despite their best intentions, their lack of requisite knowledge and expertise may inadvertently create further barriers, and the burden on carers requires careful consideration.

We also found that intrinsic motivation, enjoyable routines, habits, and a supportive environment could be important to promote long-term gains. These factors could empower people with aphasia to drive meaningful life activities, utilizing fewer personal and cognitive resources. This person-centered approach presents fresh avenues for strategies aimed at promoting long-term therapy gains in chronic aphasia. While aphasia therapy is predominantly accessible in the early recovery stages, people with chronic aphasia face the challenges throughout their lives and require knowledge, skills, resources, and effective interventions to maintain therapy gains.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (24.1 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (1,006.7 KB)Acknowledgements

Many thanks to the participants for their time and expertise.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038.2024.2356875.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Arlinghaus, K. R., & Johnston, C. A. (2019). The Importance of Creating Habits and Routine. American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine, 13(2), 142–144. https://doi.org/10.1177/1559827618818044

- Baker, C., Worrall, L., Rose, M., & Ryan, B. (2020). ‘It was really dark’: The experiences and preferences of people with aphasia to manage mood changes and depression. Aphasiology, 34(1), 19–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038.2019.1673304

- Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: a social cognitive theory. Prentice-Hall.

- Barlow, J. H., Bancroft, G. V., & Turner, A. P. (2005). Self-management training for people with chronic disease: a shared learning experience. Journal of Health Psychology, 10(6), 863–872. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105305057320

- Biel, M., Nitta, L., & Jackson, C. (2017). Understanding motivation in aphasia rehabilitation. In Coppens, P. & Patterson, J. L. (Eds.), Aphasia Rehabilitation: Clinical Challenges (pp. 393–495). Jones & Bartlett Learning.

- Bouton, M. E. (2000). A learning theory perspective on lapse, relapse, and the maintenance of behavior change. Health Psychology, 19(1, Suppl), 57–63. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.19.suppl1.57

- Bradbury-Jones, C., Breckenridge, J., Clark, M. T., Herber, O. R., Wagstaff, C., & Taylor, J. (2017). The state of qualitative research in health and social science literature: a focused mapping review and synthesis. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 20(6), 627–645. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2016.1270583

- Bradshaw, C., Atkinson, S., & Doody, O. (2017). Employing a qualitative description approach in health care research. Global Qualitative Nursing Research, 4, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1177/2333393617742282

- Brady, M. C., Kelly, H., Godwin, J., Enderby, P., & Campbell, P. (2016). Speech and language therapy for aphasia following stroke. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews(6), CD000425. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD000425.pub4

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Braun, V., Clarke, V., Hayfield, N., & Terry, G. (2019). Thematic Analysis. In P. Liamputtong (Ed.), Handbook of Research Methods in Health Social Sciences (pp. 843–860). Springer Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-5251-4_103

- Breitenstein, C., Grewe, T., Flöel, A., Ziegler, W., Springer, L., Martus, P., Huber, W., Willmes, K., Ringelstein, E. B., Haeusler, K. G., & Baumgaertner, A. (2017). Intensive speech and language therapy in patients with chronic aphasia after stroke: a randomised, open-label, blinded-endpoint, controlled trial in a health-care setting. The Lancet, 389(10078), 1528–1538. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30067-3

- Breitenstein, C., Hilari, K., Menahemi-Falkov, M., Rose, M. L., Wallace, S. J., Brady, M. C., Hillis, A. E., Kiran, S., Szaflarski, J. P., & Tippett, D. C. (2021). Operationalising treatment success in aphasia rehabilitation. Aphasiology, 1–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038.2021.2016594

- Brown, K., Worrall, L. E., Davidson, B., & Howe, T. (2012). Living successfully with aphasia: A qualitative meta-analysis of the perspectives of individuals with aphasia, family members, and speech-language pathologists. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 14(2), 141–155. https://doi.org/10.3109/17549507.2011.632026

- Code, C. (2003). The quantity of life for people with chronic aphasia. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 13(3), 379–390. https://doi.org/10.1080/09602010244000255

- Crotty, M. (1998). The Foundations of Social Research: Meaning and Perspective in the Research Process. Sydney : Allen & Unwin. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003115700

- Cruice, M., Worrall, L., & Hickson, L. (2006). Quantifying aphasic people’s social lives in the context of non‐aphasic peers. Aphasiology, 20(12), 1210–1225. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687030600790136

- Dalemans, R. J., De Witte, L., Wade, D., & van den Heuvel, W. (2010). Social participation through the eyes of people with aphasia. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 45(5), 537–550. https://doi.org/10.3109/13682820903223633

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and” why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227–268. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01

- Dijkerman, H. C., Wood, V. A., & Hewer, R. L. (1996). Long-term outcome after discharge from a stroke rehabilitation unit. Journal of the Royal College of Physicians of London, 30(6), 538. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8961209

- El Hachioui, H., Lingsma, H. F., van de Sandt-Koenderman, M. W., Dippel, D. W., Koudstaal, P. J., & Visch-Brink, E. G. (2013). Long-term prognosis of aphasia after stroke. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry, 84(3), 310–315. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp-2012-302596

- Fallahpour, M., Tham, K., Joghataei, M. T., & Jonsson, H. (2011). Perceived participation and autonomy: aspects of functioning and contextual factors predicting participation after stroke. Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine, 43(5), 388–397. https://doi.org/10.2340/16501977-0789

- Glasgow, R. E., Harden, S. M., Gaglio, B., Rabin, B., Smith, M. L., Porter, G. C., Ory, M. G., & Estabrooks, P. A. (2019). RE-AIM Planning and Evaluation Framework: Adapting to New Science and Practice With a 20-Year Review. Frontiers in Public Health, 7, 64. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2019.00064

- Glasgow, R. E., Vogt, T. M., & Boles, S. M. (1999). Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: the RE-AIM framework. American Journal of Public Health, 89(9), 1322–1327. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.89.9.1322

- Graham, J. R., Pereira, S., & Teasell, R. (2011). Aphasia and return to work in younger stroke survivors. Aphasiology, 25(8), 952–960. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038.2011.563861

- Grawburg, M., Howe, T., Worrall, L., & Scarinci, N. (2014). Describing the impact of aphasia on close family members using the ICF framework. Disability and Rehabilitation, 36(14), 1184–1195. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2013.834984

- Håkansson Eklund, J., Holmström, I. K., Kumlin, T., Kaminsky, E., Skoglund, K., Höglander, J., Sundler, A. J., Condén, E., & Summer Merenius, M. (2019). Same same or different? A review of reviews of person-centred and patient-centred care. Patient Education and Counseling, 102(1), 3–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2018.08.029

- Hersh, D. J., & Ciccone, N. (2016). Predicting potential for aphasia rehabilitation: The role of judgments of motivation. Journal of Clinical Practice in Speech-Language Pathology, 18(1), 3–7.

- Hilari, K., Wiggins, R., Roy, P., Byng, S., & Smith, S. (2003). Predictors of health-related quality of life (HRQL) in people with chronic aphasia. Aphasiology, 17(4), 365–381. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687030244000725

- Hofmann, W., Schmeichel, B. J., & Baddeley, A. D. (2012). Executive functions and self-regulation. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 16(3), 174–180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2012.01.006

- Howe, T., Davidson, B., Worrall, L., Hersh, D., Ferguson, A., Sherratt, S., & Gilbert, J. (2012). ‘You needed to rehab … families as well’: family members’ own goals for aphasia rehabilitation. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 47(5), 511–521. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-6984.2012.00159.x

- Kanfer, F. H., & Karoly, P. (1972). Self-control: A behavioristic excursion into the lion’s den. Behavior Therapy, 3(3), 398–416. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7894(72)80140-0

- Kleim, J. A., & Jones, T. A. (2008). Principles of experience-dependent neural plasticity: implications for rehabilitation after brain damage. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 51(1), S225–239. https://doi.org/10.1044/1092-4388(2008/018)

- Kristinsson, S., Basilakos, A., Den Ouden, D. B., Cassarly, C., Spell, L. A., Bonilha, L., Rorden, C., Hillis, A. E., Hickok, G., & Johnson, L. (2023). Predicting Outcomes of Language Rehabilitation: Prognostic Factors for Immediate and Long-Term Outcomes After Aphasia Therapy. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 66(3), 1068–1084. https://doi.org/10.1044/2022_JSLHR-22-00347

- Kvale, S. (2015). InterViews : Learning the Craft of Qualitative Research Interviewing (3rd ed.). Los Angeles : Sage Publications.

- Kwasnicka, D., Dombrowski, S. U., White, M., & Sniehotta, F. (2016). Theoretical explanations for maintenance of behaviour change: A systematic review of behaviour theories. Health Psychology Review, 10(3), 277–296. https://doi.org/10.1080/17437199.2016.1151372

- Lanyon, L., Worrall, L., & Rose, M. (2019). “It’s not really worth my while”: understanding contextual factors contributing to decisions to participate in community aphasia groups. Disability and Rehabilitation, 41(9), 1024–1036. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2017.1419290

- Maclean, N., Pound, P., Wolfe, C., & Rudd, A. (2002). The concept of patient motivation: a qualitative analysis of stroke professionals’ attitudes. Stroke, 33(2), 444–448. https://doi.org/10.1161/hs0202.102367

- Menahemi-Falkov, M., Breitenstein, C., Pierce, J. E., Hill, A. J., O’Halloran, R., & Rose, M. L. (2022). A systematic review of maintenance following intensive therapy programs in chronic post-stroke aphasia: importance of individual response analysis. Disability and Rehabilitation, 44(20), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2021.1955303

- Morris, R., Eccles, A., Ryan, B., & Kneebone, I. I. (2017). Prevalence of anxiety in people with aphasia after stroke. Aphasiology, 31(12), 1410–1415. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038.2017.1304633

- Nichol, L., Wallace, S. J., Pitt, R., Rodriguez, A. D., Diong, Z. Z., & Hill, A. J. (2022). People with aphasia share their views on self-management and the role of technology to support self-management of aphasia. Disability and Rehabilitation, 44(24), 7399–7412. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2021.1989501

- Nichol, L., Wallace, S. J., Pitt, R., Rodriguez, A. D., & Hill, A. J. (2022). Communication partner perspectives of aphasia self-management and the role of technology: an in-depth qualitative exploration. Disability and Rehabilitation, 44(23), 7199–7216. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2021.1988153

- Palmer, R., Witts, H., & Chater, T. (2018). What speech and language therapy do community dwelling stroke survivors with aphasia receive in the UK? PLOS ONE, 13(7), e0200096. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0200096

- Papathanasiou, I. (2017). Aphasia and Related Neurogenic Communication Disorders (2nd ed.). Jones & Bartlett Publishers.

- Park, Y. H., Jang, J.-W., Park, S. Y., Wang, M. J., Lim, J.-S., Baek, M. J., Kim, B. J., Han, M.-K., Bae, H.-J., & Ahn, S. (2015). Executive function as a strong predictor of recovery from disability in patients with acute stroke: a preliminary study. Journal of Stroke and Cerebrovascular Diseases, 24(3), 554–561. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2014.09.033

- Patton, M. Q. (2015). Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods : Integrating Theory and Practice (4th ed.). Sage.

- Perry,A.(2004). Therapy outcome measures for allied health practitioners in Australia: the AusTOMs. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 16(4), 285–291. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzh059

- Prochaska, J. O., DiClemente, C. C., & Norcross, J. C. (1992). In search of how people change: applications to addictive behaviors. The American Psychologist, 47(9), 1102–1114. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.47.9.1102

- Purdy, M. (2002). Executive function ability in persons with aphasia. Aphasiology, 16(4–6), 549–557. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687030244000176

- Raymer, A. M., Beeson, P., Holland, A., Kendall, D., Maher, L. M., Martin, N., Murray, L., Rose, M., Thompson, C. K., & Turkstra, L. (2008). Translational research in aphasia: From neuroscience to neurorehabilitation. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 51(1), S259–275. https://doi.org/10.1044/1092-4388(2008/020)

- Rose, M., Ferguson, A., Power, E., Togher, L., & Worrall, L. (2014). Aphasia rehabilitation in Australia: Current practices, challenges and future directions. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 16(2), 169–180. https://doi.org/10.3109/17549507.2013.794474

- Rose, M., Nickels, L., Copland, D., Togher, L., Godecke, E., Meinzer, M., Rai, T., Cadilhac, D. A., Kim, J., Hurley, M., Foster, A., Carragher, M., Wilcox, C., Pierce, J. E., & Steel, G. (2022). Results of the COMPARE trial of Constraint-induced or Multimodality Aphasia Therapy compared with usual care in chronic post-stroke aphasia. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry 93(6), 573–581. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp-2021-328422

- Rothman, A. J., Baldwin, A. S., Hertel, A. W., & Fuglestad, P. T. (2011). Self-regulation and behavior change: Disentangling behavioral initiation and behavioral maintenance. In K. D. Vohs & R. F. Baumeister (Eds.), Handbook of self-regulation: Research, theory, and applications (pp. 106–122). The Guilford Press.

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American psychologist, 55(1), 68–78. https://doi.org/10.1037//0003-066x.55.1.68

- Schwarzer, R. (2008). Modeling health behavior change: How to predict and modify the adoption and maintenance of health behaviors. Applied Psychology, 57(1), 1–29.

- Sheeran, P., Maki, A., Montanaro, E., Avishai-Yitshak, A., Bryan, A., Klein, W. M., Miles, E., & Rothman, A. J. (2016). The impact of changing attitudes, norms, and self-efficacy on health-related intentions and behavior: A meta-analysis. Health Psychology, 35(11), 1178. https://doi.org/10.1037/hea0000387

- Simic, T., Rochon, E., Greco, E., & Martino, R. (2017). Baseline executive control ability and its relationship to language therapy improvements in post-stroke aphasia: a systematic review. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 29(3), 1–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/09602011.2017.1307768

- Skidmore, E. R., Whyte, E. M., Holm, M. B., Becker, J. T., Butters, M. A., Dew, M. A., Munin, M. C., & Lenze, E. J. (2010). Cognitive and affective predictors of rehabilitation participation after stroke. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 91(2), 203–207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2009.10.026

- Tong, A., Sainsbury, P., & Craig, J. (2007). Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 19(6), 349–357. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzm042

- Verplanken, B., & Orbell, S. (2003). Reflections on past behavior: a self‐report index of habit strength. Journal of applied social psychology, 33(6), 1313–1330. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2003.tb01951.x

- Voils, C. I., Gierisch, J. M., Yancy Jr, W. S., Sandelowski, M., Smith, R., Bolton, J., & Strauss, J. L. (2014). Differentiating behavior initiation and maintenance: Theoretical framework and proof of concept. Health Education & Behavior, 41(3), 325–336. https://doi.org/10.1177/1090198113515242

- Wallace, S. J., Worrall, L., Rose, T., Le Dorze, G., Cruice, M., Isaksen, J., Kong, A. P. H., Simmons-Mackie, N., Scarinci, N., & Gauvreau, C. A. (2017). Which outcomes are most important to people with aphasia and their families? An international nominal group technique study framed within the ICF. Disability and Rehabilitation, 39(14), 1364–1379. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2016.1194899

- Weatherill, M., Tibus, E. O., & Rodriguez, A. D. (2022). Motivation as a predictor of aphasia treatment outcomes: A scoping review. Topics in Language Disorders, 42(3), 252–265. https://doi.org/10.1097/TLD.0000000000000286

- Witkiewitz, K., & Marlatt, G. A. (2009). Relapse prevention for alcohol and drug problems: that was Zen, this is Tao. The American Psychologist, 59(4), 224–235. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.59.4.224

- Worrall, L., Sherratt, S., Rogers, P., Howe, T., Hersh, D., Ferguson, A., & Davidson, B. (2011). What people with aphasia want: Their goals according to the ICF. Aphasiology, 25(3), 309–322. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038.2010.508530

- Wray, F., & Clarke, D. (2017). Longer-term needs of stroke survivors with communication difficulties living in the community: a systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative studies. BMJ Open, 7(10), e017944. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017944