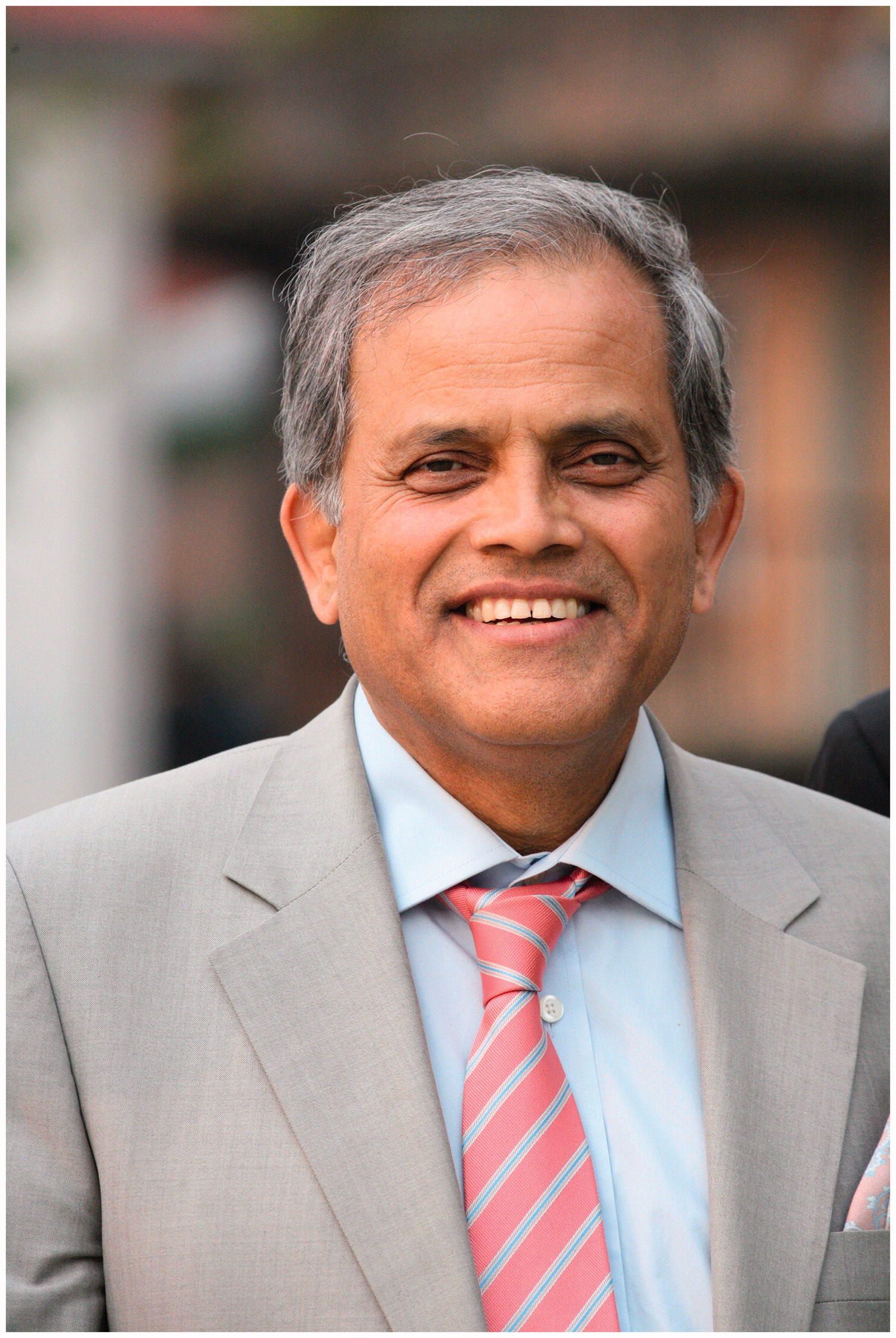

Professor Upendra Devkota, FRCS (Glasg.), FRCSEd (Ad hominem), FCSHK (Hong Kong), FNAMS (NAMS)- Nepal's first and foremost neurosurgeon – died at the age of 64 on 18th June 2018.

Professor Upendra Devkota, FRCS (Glasg.), FRCSEd (Ad hominem), FCSHK (Hong Kong), FNAMS (NAMS)- Nepal's first and foremost neurosurgeon – died at the age of 64 on 18th June 2018.

He was born in 1953 in a remote village in the Gorkha hills of Nepal, where his father was an Ayurvedic physician. He said later that his father's devotion to his patients had a profound influence on him. There were neither roads nor electricity, and “Dev” as he was known by his many British friends, was proud of the fact that he was barefoot until the age of fourteen. He had the good fortune to be one of the first boys in the area to attend a newly established missionary school. Although he became a man of science, he remained at the same time very close to his Hindu inheritance and the Sanskrit scriptures. His brilliance and capacity for hard work showed at any early age as he secured one of the three coveted government scholarships to study medicine at the Assam Medical College in India, qualifying MBBS in 1977.

On his return to Kathmandu he worked at the Bir Hospital, the main government hospital in the city. He was a protégé there of Dr. Dinesh Nath Gongol and quickly showed himself to be an outstanding surgeon. He was therefore sent on a British Council scholarship (flying Business Class on BOAC to his amazement) to train in neurosurgery at the Southern General in Glasgow under Graham Teasdale. He later went on to work as a Senior Registrar at Atkinson Morley's Hospital and the National Hospital, Queen Square. Unlike many other overseas trainees who were sent to be trained in the UK, he did not stay but instead returned to Nepal where he established Nepal's first specialist neurosurgical unit at the Bir. This was a truly extraordinary achievement – not only did he have to carry out his own direct carotid puncture angiograms (a technique taught to him by Dr Jamie Ambrose at AMH), he painted and directed the ward himself with the dedicated team which he slowly built up. The unit was equipped through the generous help from his friends abroad, particularly from the UK. Eventually, the department (described by one UK visitor as a “beacon of light in the darkness” when compared to the rest of the hospital) became so good that it started its own post-graduate neurosurgical training.

In 2002 he was appointed as the Minister for Health, Science and Technology by the King of Nepal, an appointment ending when the King ill-advisedly dismissed his Cabinet during the Maoist insurgency, which ultimately led to the downfall of the monarchy. Dev ruefully commented that he had probably saved more lives by making motorcycle helmets compulsory when he was Minister than he had saved as a neurosurgeon.

It became apparent that working within the constraints of the poorly resourced government sector was making it impossible to continue to take Nepali neurosurgery into the modern age (a common problem in poorer countries). He therefore built and equipped his own hospital on the outskirts of Kathmandu. This is almost certainly the best designed and most efficient hospital in Nepal, and, once again, a truly remarkable achievement. State-of-the-art modern neurosurgery has been practiced there now for 12 years and Dev became famous throughout Nepal.

Near the hospital he and his wife Madhu built a beautiful home on the edge of a rice paddy (now, alas, surrounded by suburban development). The exquisite garden they created is a little demi-paradise and reflects the same care and attention to detail to be found in their hospital. His many British friends and colleagues were always welcome here and always received the most generous hospitality.

Dev was one of the most extraordinary men I have had the honour of knowing – charming, enthusiastic and determined in equal measure, and utterly devoted to his patients. His far too short life started in the rural hardship of a peasant society and ended in brilliant success, high government office and high tech neurosurgery – a truly remarkable transition. He was one of Nepal's most loyal sons. He had plans to return to politics and still had much to offer that turbulent country. He leaves behind his wife Madhu, Professor of Public Health at Tribhuvan University, and three daughters, one of whom is following him into the medical profession. He will be sorely missed.