Abstract

Introduction

A chronic subdural haematoma (cSDH) is a collection of altered blood products between the dura and brain resulting in a slowly evolving neurological deficit. It is increasingly common and, in high income countries, affects an older, multimorbid population. With changing demographics improving the care of this cohort is of increasing importance.

Methods

We convened a cross-disciplinary working group (the ‘Improving Care in Elderly Neurosurgery Initiative’) in October 2020. This comprised experts in neurosurgical care and a range of perioperative stakeholders. An Implementation Science framework was used to structure discussions around the challenges of cSDH care within the United Kingdom. The outcomes of these discussions were recorded and summarised, before being circulated to all attendees for comment and refinement.

Results

The working group identified four key requirements for improving cSDH care: (1) data, audit, and natural history; (2) evidence-based guidelines and pathways; (3) shared decision-making; and (4) an overarching quality improvement strategy. Frequent transfers between care providers were identified as impacting on both perioperative care and presenting a barrier to effective data collection and teamworking. Improvement initiatives must be cognizant of the complex, system-wide nature of the problem, and may require a combination of targeted trials at points of clinical equipoise (such as anesthetic technique or anticoagulant management), evidence-based guideline development, and a cycle of knowledge acquisition and implementation.

Conclusion

The care of cSDH is a growing clinical problem. Lessons may be learned from the standardised pathways of care such as those as used in hip fracture and stroke. A defined care pathway for cSDH, encompassing perioperative care and rehabilitation, could plausibly improve patient outcomes but work remains to tailor such a pathway to cSDH care. The development of such a pathway at a national level should be a priority, and the focus of future work.

What is a chronic subdural hematoma and what is the case for change?

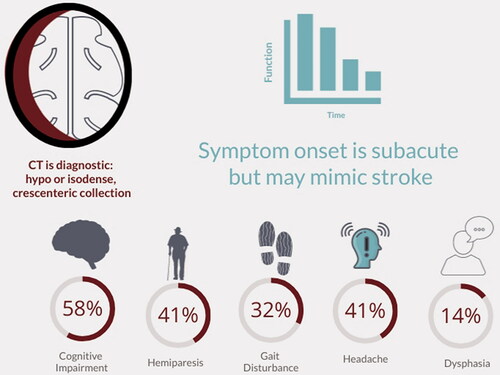

A chronic subdural haematoma (cSDH) is a collection of altered blood products that can form between the dural membrane and the surface of the brain. Most commonly occurring in older, medically complex cohorts,Citation1–4 cSDH is strongly associated with age.Citation1,Citation5–7 It can lead to neurological impairment through localised perfusion deficits secondary to the mass effect of the cSDHCitation8,Citation9 or through direct distortion of key motor pathways.Citation10 Symptoms may mimic a stroke, including hemiplegia or gait disturbance, headache and worsening cognition.Citation2 Subacute and progressive deficits typically occur over days to weeks, although more acute and/or transient presentations are also possibleCitation8 (). Current incidence estimates range from 1.7/100,000/yearCitation5 to 48/100,000/year,Citation11,Citation12 but several longitudinal studies have demonstrated increased incidence over time, likely driven by aging populations, increased detection linked to access to imaging, and use of anticoagulation.Citation7,Citation11,Citation13–15 Shifting demographics may lead to significant increases in case numbers over the coming decades.Citation12,Citation16

Figure 1. Presenting symptoms of chronic subdural haematoma (cSDH). Percentages refer to the percentage of patients presenting with these symptoms in a nationwide audit of UK surgical practice.Citation2

Some medical therapies for cSDH have been proposed and trialled,Citation17 and procedures such as middle meningeal artery embolisation are under investigation,Citation18 but surgical evacuation currently remains the mainstay of treatment for symptomatic cSDH. Approximately 13,000 cSDH operations were conducted in England between 2013 and 2019.Citation19 However, surgery is associated with in-patient morbidity and mid-term mortalityCitation2,Citation3 and significant hospital stay.Citation17 The rising burden of disease and the potential for associated morbidity and mortality makes improving the care of patients with cSDH a healthcare priority.

Progress in improving care has in part been hindered by weaknesses in the evidence base for cSDH. It is a relatively small research field, and activity has largely been focused on the delivery of surgery itself. This has paid dividends in terms of defining best practice for surgical intervention,Citation17,Citation20 but little is known of what happens to those not accepted for surgery,Citation2 including how they are managed, by whom, and their likelihood of going on to being re-referred or discharged – though two studies demonstrate higher mortality (44% vs. 17%) in non-operated versus operated patients at four weeks, but the numbers are small and likely to be distorted by unmatched frailty, age, and comorbidity characteristics between cohorts.Citation13 Likewise, other aspects of perioperative management remain under-developed and poorly specified.Citation21 For example, extended rehabilitation models are not standardised, and care is typically provided by non-specialist professionals outside of designated neurosurgical centres. The experiences of patients and families at different points in the care journey and their priorities for outcome measures remain neglected as areas of study. These gaps in the evidence pose challenges for determining ‘what good looks like’Citation22 in the care of people with chronic subdural haematoma.

What could good look like?

Important learning is available from other surgical fields that have improved care, including hip fracture fixationCitation23 and emergency laparotomy.Citation24 In hip fracture, for example, clear evidence has emerged of the role of integrated working in dramatically reducing mortality:Citation25 hip fractures are now co-managed between orthopaedic surgery and specialists in geriatric medicine.Citation23 These pathways have similarities with cSDH in that they serve a population of older, frail patients requiring emergency surgical intervention. However, the care of patients with cSDH is characterised by further additional complexities.Citation2 First, not all people with cSDH require or will benefit from surgery. In the UK, around 30% of patients referred for a neurosurgical opinion will not be accepted for surgery, in the main (∼70%) owing to a lack of symptoms.Citation2 Second, of those accepted, between 47% and 90% of UK patients are transferred between hospitals.Citation2,Citation3 These transfers of care create significant challenges to communication, safety, flow, and patient experience.Citation26 Successfully improving pathways requires clear understanding and design of the entirety of the patient journey between providers and relinquishing a siloed approach.Citation26 Encouragingly, an audit of the only published example of an integrated care pathway for cSDH to date found that it significantly increased the number of patients undergoing surgery within 24 hours of admission.Citation27

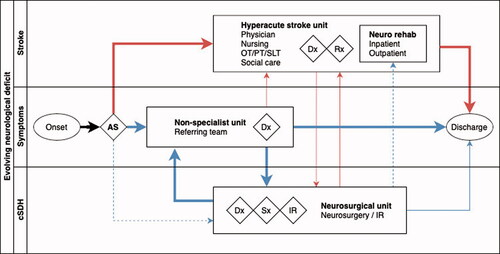

Much valuable learning is also likely to be had from examining pathways outside of surgery, including stroke. Stroke care has evolved significantly in recent years, supported not only by a high quality national clinical audit but also by a highly organised framework of acute referral pathways, crossing primary, secondary and tertiary settings, including treatment and rehabilitation, alongside pre- and acute stroke management. Care today is coordinated effectively through a multidisciplinary team comprising physicians, specialist nurses, anaesthetists, critical care physicians, neurosurgeons, and interventional radiologists, within and between centres.Citation28 With the emergence of interventions such as thrombectomy and the protocolisation of referral for decompressive hemicraniectomy, liaison between referring hospitals and specialist neuroscience centres for stroke has become increasingly routine. Furthermore, the overlap in presenting symptoms between cSDH and acute stroke () mean that it is possible that patients may first present to a local centre’s stroke service ().

Figure 2. Comparison of patient pathways for chronic subdural haematoma and acute stroke demonstrating common themes and journeys. Width of line indicative of proportion of patients in each diagnostic cohort following that pathway. Dashed lines indicate an ‘exceptional’ route of presentation (e.g. a patient with a chronic subdural transferred directly to a neurosciences centre as the closest local facility). Blue lines indicate pathway for patients with chronic subdural and red lines indicate patients with acute stroke. AS: ambulance service; cSDH: chronic subdural haematoma; Dx: diagnosis: IR interventional radiology; Rx: medical treatment; Sx: surgical treatment.

The improvements seen in emergency surgery and stroke offer promising precedents, but seeking to reproduce these successes for cSDH will require specific and sustained attention.

Improving care of chronic subdural haematoma

Recognising the distributed and complex nature of the care needed for people with chronic subdural haematoma, and the requirements for multidisciplinary expertise, the ‘Improving Care in Elderly Neurosurgery Initiative (ICENI)’Citation29 was formed in 2019. A multi-disciplinary group of UK stakeholders, including representatives from across the cSDH perioperative care team, patient advocacy groups, and national experts in healthcare improvement, ICENI is exploring the possibility of understanding, designing, and implementing an integrated pathway for cSDH management. Such a pathway should draw on lessons learned from design and implementation of other care pathways, principles of implementation science, systems thinking,Citation22 and a range of diverse perspectives.

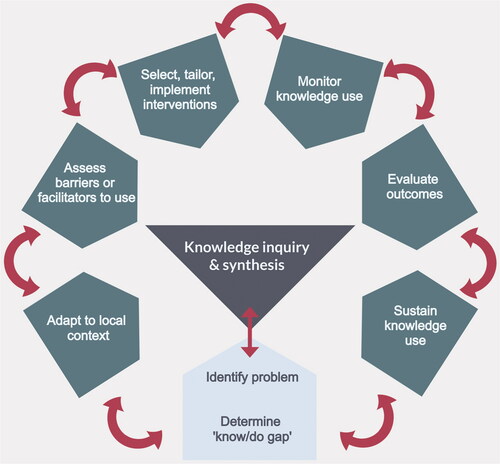

Implementation science – the ‘dynamic and iterative process that includes synthesis, dissemination, exchange and ethically-sound application of knowledge to improve health, provide more effective health services and products, and strengthen the health care system’ – offers a useful framework for structuring thinking in this area.Citation30 Various approaches and models have been proposed, including Straus’s knowledge to action cycle ().Citation30 In this model, a key starting point is the identification and definition of knowledge gaps (‘determine the know/do gap’ in ), establishing both the requirement for new knowledge, and subsequent improved application of existing knowledge.

Figure 3. The Knowledge to Action Cycle. This demonstrates the cyclical nature of steps translating knowledge into action for a specific domain. This article seeks to identify problems and the ‘know/do’ gap in current care of chronic subdural haematoma (light box), the first step in any initiative to improve care. Figure adapted from Straus et al.Citation30

Following a meeting of national stakeholders in October 2020 and using this framework, the ICENI collaborative identified three key requirements for improving care of cSDH () and need for an integrated quality improvement strategy. Here we summarise these requirements, with reference to their respective evidence base and highlighting the key knowledge gaps.

Table 1. Key requirements for improving the care of patients with chronic subdural haematoma derived from a meeting of national stakeholders.

Data, audit, and natural history

A first challenge in improving care of cSDH is the absence of high-quality data. In other areas of clinical practice, disease registries and large-scale clinical audits have had an important role in improving care over time, helping in systematic assessment of care and in identifying areas for improvement. For instance, the national hip fracture database (NHFD)Citation31 has been linked to substantial reductions in mortality,Citation32 supported by best practice tariffs.Citation33

Some disease specific-registries for neurosurgical conditions – such as that for ventriculoperitoneal shuntsCitation34 – already exist, and could potentially be adapted to accommodate cSDH if a consensus view on minimum datasets and quality indicators could be achieved.Citation35 With appropriate information governance, a system that could capture relevant processes and outcomes different stages of the patient journey (e.g. referring and neuroscience centres) may also be possible. As well as helping to guide practice, such a registry, alongside a national audit program analogous to the NHFDCitation31 or the National Emergency Laparotomy Audit (NELA),Citation36 would help improve understanding of the epidemiology of cSDH by providing a consistent case definitions and address issues with use of current diagnostic and operative codes.Citation37 This is a crucial requirement, as routine hospital coding currently crudely categorises all subdural haematoma as either traumatic or non-traumatic based on the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) framework. This distinction is not reflective of the clinical phenotype of cSDH,Citation38 and has shown poor sensitivity and specificity for identifying cases in large scale registries.Citation37 Improved, standardised, case-definitions could not only aid ongoing audit but could also clarify understanding of population epidemiology,Citation12 including outcomes for patients with cSDH who do not undergo surgery and who may be missing from surgical databases.

Evidence-based guidelines and integrated care pathways

Much can be done to support the specification of good practice for care of people with cSDH. In this section we identify three areas along the patient journey where discussions highlighted how current practice could benefit from being defined in an integrated manner. In so doing, we also identify further crucial evidence gaps, including points of equipoise that may be amenable to a future randomised controlled trial.

Pre-surgical optimisation

Presentation of cSDH is characterised by clinical variability, with high rates of baseline disability, comorbidity, and polypharmacy,Citation2,Citation3 and frailty. These factors have clear implications for both anaesthetic and surgical management, and, as demonstrated in other clinical areas, are consequential for outcomes.Citation23,Citation24 In a nationwide survey of UK operative practice, the median modified Rankin score (mRS) at the point of admission was three (indicating moderate disability) with over 40% of patients receiving anticoagulant and antiplatelet medications.Citation2 Over 60% of patients in one study had an American Society of Anesthesiologists score of three (severe systemic disease)Citation3 with high rates of cardiovascular and respiratory disease.Citation2,Citation3 Although age has been related to outcomes,Citation39 including discharge Glasgow Outcome ScoreCitation40 and mortality at 90 daysCitation1 it is plausible that this may reflect underlying rates of comorbidity or frailty. Application of a hospital frailty index to a centralised national health service (NHS) databaseCitation41 demonstrated that 50% of examined neurosurgical patients were classed as severely frail, with these patients exhibiting longer length of stay.Citation42 Further, direct evidence may come from the embedding of frailty assessment into specialist services such as neurosurgery that is being supported by the Specialised Clinical Frailty Network.Citation43 The importance of appropriate perioperative management of the frail patient is reflected in recent guidelines.Citation44

How best to optimise candidates for cSDH surgery across hospital sites is an important concern. Work from one specialist centre suggests that a policy of instigating medical optimisation in referring centres does shorten time to surgery but does not appear to affect outcome at the point of neuroscience centre discharge,Citation27 but numbers were small. Whether to instigate medical optimisation in the referring hospital or upon arrival in the neurosciences centre is a key unknown, and may well be dependent on the facilities available in both hospitals. Experience from the fractured neck of femur pathwayCitation45 is suggestive of trade-offs in terms of timing between pre-optimisation and definitive management, with delays to treatment resulting in greater deconditioning and worse overall outcome. Currently available data demonstrates that longer time to surgery is associated with longer length of stay and a non-significant (p = 0.06) trend towards worse functional outcome at discharge when waits are longer than seven days.Citation46 The impact of repeated pre-operative cancellations should also be considered, given the evidence of a relationship between nutritional status and outcome after cSDH.Citation47

A key stage of perioperative optimisation is the management of antiplatelet and anticoagulant medication. Approximately 45% of patients who present with cSDH are taking some form of anticoagulant or antiplatelet agent.Citation2,Citation3 This may be a critical source of morbidity, as highlighted by a recent population study using the Medicare database, which identified that patients were at a fourfold increased risk of an ischaemic stroke in the four weeks after sustaining a cSDH.Citation48

Perioperative management of antithrombotic agents draws heavily on findings from related conditions, or observational dataCitation49 and requires individualisation based on patient, surgical, and pharmacological factors. Broadly, management consists of efforts to reverse antithrombotic effects or delay surgery, where possible, until drug levels have cleared.Citation50 Duration between cessation of antiplatelet agents and surgery is associated with recurrence rates in observational data, with recurrence rates appearing comparable after three days.Citation51 Platelet transfusion appears to be common practice when surgery cannot be delayed, but this practice lacks a robust evidence base.Citation52

In a national survey of UK practice, reversal strategies included platelet transfusion (administered in approximately 30% of those receiving aspirinCitation2) delayed transfer for surgery in non-urgent patients(∼8% of referralsCitation2) and use of clotting factors and vitamin K. Importantly, patients in this study were recruited in 2013–2014 and only 1% of patients received ‘other’ anticoagulant or antiplatelet drugs (including direct acting oral anticoagulants [DOACs], such as the Factor Xa and direct thrombin inhibitors). This figure was approximately 5% in a trial cohort recruited between 2015 and 2019Citation17 but at a population level, use of these drugs has increased dramatically over this period.Citation53

Specific reversal agents include idaricuzumabCitation54 for the reversal of dabigration (an oral direct thrombin inhibitor), prothrombin complex concentrate (for warfarin and off licence management of bleeding associated with oral factor Xa inhibitors despite very low quality evidenceCitation55), and Andexanet alfa for the reversal of Xa inhibitors apixaban and rivaroxaban. However, andexanet alfa is not currently recommended by NICECitation56 or the British Society for HaematologyCitation57 for the perioperative management of intra-cranial haemorrhage which is at variance with the summary of product characteristicsCitation58 and guidance from the Scottish medicines compendium.Citation59

Surgery and the immediate post-operative period

The surgical procedure for cSDH is now well characterised,Citation20,Citation60 with the use of subdural drains and burr-hole drainage associated with a normalised risk of death over five years compared with an age- and sex-matched population.Citation61 Alternative techniques – such as twist drill craniostomy or craniotomy –may have roles in specific circumstances.Citation60 However, uncertainty persists around optimal anaesthetic technique. Intraoperative events do not appear to be associated with surgical outcome in retrospective datasets,Citation3 but questions endure as to whether surgery under general (GA) or local anaesthesia (LA) is the optimal choice?

Data from both the UK and elsewhere suggest that majority of cases are performed under GACitation2,Citation62 although a retrospective study examining outcomes in non-agenerians highlighted a high (93%) rate of LA use in a Scandinavian cohort.Citation1 No robust randomised controlled trials examining this issue exist and our discussions in ICENI highlighted likely equipoise. Questions around patient selection as well as training provision for anaesthetists and surgeons remain unresolved. Although only 3% of operations were performed by consultant neurosurgeons in one national auditCitation2 data appears to suggest that grade of surgeon is not associated with outcomeCitation63 although no equivalent data exists regarding seniority of anaesthetist. Consideration of the required anaesthetic expertise and appropriate training should be a priority for future work.

National data from across the UK also highlights heterogeneity in immediate postoperative management, with varying periods of bed rest, routine post-operative imaging, and the use of high-flow oxygen.Citation2 Care is normally conducted on a neurosurgical ward before referral for ongoing rehabilitation, or repatriation to the referring hospital occurs. Delays in repatriation can cause pressures on limited neurosurgical bed numbers.Citation64 A crucial issue to address in this phase of care concerns decision-making surrounding antithrombotic drugs; the literature fails to offer consensus on the optimal restarting of antithrombotic drugs in patients with cSDH,Citation65 despite suggestions from retrospective data that timing of resumption may significantly alter the occurrence of post-operative thrombotic and haemorrhagic complications.Citation66

Rehabilitation

A key area of concern in cSDH is the availability of appropriate rehabilitation. The solution to this is far from obvious, with questions as to the most appropriate models and locations of care. The pressures on neurosurgical bedsCitation64 appears to render rehabilitation on an acute neurosurgical ward unfavourable, but needs to be considered considering length-of-stay dataCitation3,Citation19 and the risks of prolonged immobilisation on recovery in other surgical settings. In the UK, rehabilitation services may be either locally or nationally commissionedCitation67 depending on patient complexity. ‘Hyper-acute rehabilitation’ can be commenced pending an appropriate referral and acceptance to either specialist inpatient or community services,Citation67 but the appropriate model for cSDH requires design and testing.

Any future integration and streamlining of rehabilitation pathways for cSDH patients will require improved understanding of rehabilitation requirements at the point of discharge from acute hospital beds across both operative and non-operative cohorts. Again, existing models may provide valuable lessons: both stroke and major trauma rehabilitation have been integrated into their respective care pathways to address the challenge of linking tertiary and secondary centres. Arguably, this dichotomising of care between centres could also create challenges in timely recognition and identification of post-operative complications such as recurrence as well as rehabilitation difficulties. However, detailed understanding of events following repatriation is currently lacking.

Shared decision-making

Good practice in shared decision-making and communication between professionals and patients and their relatives is a priority for cSDH. However, very little is known about patients, families, and clinicians experiences of these discussions or their understanding of different points in the patient journey, including temporality of intervention and likelihood of transfer. Many conversations are likely to be conducted by non-specialist clinicians from acute medical or emergency medicine backgrounds, in non-specialist hospitals. However, the absence of validated risk stratification tools,Citation68 a lack of standardised UK criteria for acceptance for surgery, and absence of data on patients and families experiences of current care practices means that referring clinicians may face significant uncertainties in referral and decision-making processes. Pre-surgical discussions and shared decision-making with patients and family members, including communication of the rationale for either proceeding to surgery or opting for a conservative approach, may therefore be very challenging. In other surgical cohorts the role of pre-operative frailty assessment has shown utility in identifying higher risk patients, and further work on the importance of this in CSDH may be of use. Further complexity may arise in the future as the findings of ongoing randomised controlled trials are focusing on medical therapies as both adjuvant and/or true conservative managementCitation69 become integrated into practice.

A quality improvement strategy

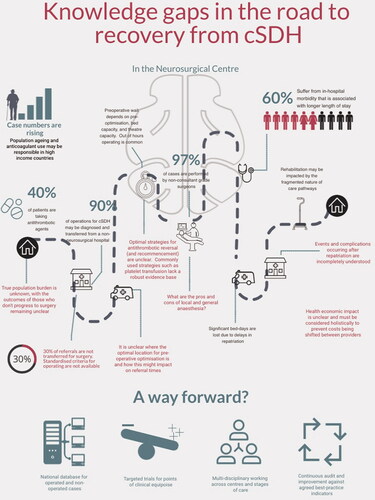

cSDH represents a significant and growing clinical burden where significant knowledge gaps exist () at every level. Current cSDH expertise is focused largely on tertiary neurosciences centres, complicating both effective acute and long-term management of the condition, whereas overlooking incidental disease. Research has remained largely narrowly focus on emergent treatment. A broader, whole-system, integrated approach to cSDH could bring benefit to patients, care takers, and service providers.

Figure 4. Knowledge gaps in current care for cSDH. Red text indicates knowledge gaps identified by the ICENI collaborative. Green text at lower edge identifies four main steps that may be taken to advance care in this area. Percentages were drawn from references.Citation2,Citation3 cSDH: chronic subdural haematoma; ICENI: Improving Care in Elderly Neurosurgery Initiative.

The regional ‘hub and spoke’ model currently coordinating cSDH treatmentCitation70 was identified in our discussions as a driver of many challenges, but it may also represent an opportunity for the development and implementation of solutions. First, many of the challenges pertaining to care ‘within’ a region (such as inter-hospital transfer) may be common ‘between’ regions, offering the opportunity to generate and share learning and best practice between referral networks. Methods such as collaborative multi-stakeholder consensus-building at scale may be especially helpful in enabling diverse expertise to be captured and synthesised into visions and delivery plans for ‘what good looks like’ in areas including clinical pathways, case definitions, communication, and operational processes and work system design.Citation71 This not only may aid in the rapid adoption of interventions such as best-practice statements or audit infrastructure in the short-term, but also creates a framework for comparing future complex interventions or research findings between centres, for instance in a cluster-randomised trial.

Conclusions and next steps

cSDH is increasingly recognised as a ‘sentinel health event’.Citation72,Citation73 The multi-disciplinary ICENI collaborative has identified several challenges that must be addressed if the care of people with cSDH is to be improved. Many of these arise from distributed nature of care for most of these patients, leading to incomplete understanding of patient outcome, cross-specialty requirements, disease burden, and a supported decision-making process. The care improvements delivered in related clinical areas offer both a precedent for success, and potentially transferable solutions, although additional cSDH specific knowledge gaps remain. A wide-ranging programme of health services research is needed to tackle questions concerning models of care and service design, patients and families experiences of care and how best to share decisions, improvement strategies, and economic evaluation.Citation74–76 Improving system design and processes will need to proceed together with a well-founded programme of research to address clinical questions, including those likely to benefit from randomised controlled trials. One uncertainty amenable to a trial, for example, is that of GA versus LA for cSDH, analogous to the GALA trial examining their use in carotid endarterectomy.Citation77

What is clear is addressing these challenges comprehensively will require a multi-disciplinary and system-wide approach. Similarly, we recognise that the challenges of implementing change will differ between healthcare systems, especially between high and low- and middle-income countries. Our next step is to identify key themes which could form the basis of working groups to address some of these challenges. These groups will seek to develop a consensus framework that could build towards a long-term goal of clinical practice guidelines. This process would be strengthened by further collaboration with any interested parties.

Disclosure statement

WT has received speaker’s fees or sat on advisory boards for: Alexion, Portola, Sobi, Pfizer, Bayer, NovoNordisk, Ablynx, Daiichi Sankyo, Takeda, and Sanofi. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the Error! Hyperlink reference not valid., or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bartek JJ, Sjavik K, Stahl F, et al. Surgery for chronic subdural hematoma in nonagenarians: a Scandinavian population-based multicenter study. Acta Neurol Scand 2017;136:516–20. http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=med13&NEWS=N&AN=28382656

- Brennan PM, Kolias AG, Joannides AJ, et al. The management and outcome for patients with chronic subdural hematoma: a prospective, multicenter, observational cohort study in the United Kingdom. J Neurosurg 2017;127:732–9.

- Stubbs DJ, Davies BM, Bashford T, et al. Identification of factors associated with morbidity and postoperative length of stay in surgically managed chronic subdural haematoma using electronic health records: a retrospective cohort study. BMJ Open 2020;10:e037385.

- Edlmann E, Giorgi-Coll S, Whitfield PC, et al. Pathophysiology of chronic subdural haematoma: Inflammation, angiogenesis and implications for pharmacotherapy. J Neuroinflammation 2017;14:13.

- Foelholm R, Waltimo O. Epidemiology of chronic subdural haematoma. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 1975;32:247–50. http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=med1&NEWS=N&AN=1225014

- Kudo H, Kuwamura K, Izawa I, Sawa H, Tamaki N. Chronic subdural hematoma in elderly people: present status on Awaji Island and epidemiological prospect. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 1992;32:207–9. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1378564

- Rauhala M, Luoto TM, Huhtala H, et al. The incidence of chronic subdural hematomas from 1990 to 2015 in a defined Finnish population. J Neurosurg 2020;132:1147–57.

- Alkhachroum AM, Fernandez-Baca Vaca G, Sundararajan S, et al. Post-subdural hematoma transient ischemic attacks: hypoperfusion mechanism supported by quantitative electroencephalography and transcranial doppler sonography. Stroke 2017;48:e87–e90.

- Slotty PJ, Kamp MA, Steiger SHJ, et al. Cerebral perfusion changes in chronic subdural hematoma. J Neurotrauma 2013;30:347–51.

- Yokoyama K, Matsuki M, Shimano H, et al. Diffusion tensor imaging in chronic subdural hematoma: correlation between clinical signs and fractional anisotropy in the pyramidal tract. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2008;29:1159–63.

- Adhiyaman V, Chattopadhyay I, Irshad F, et al. Increasing incidence of chronic subdural haematoma in the elderly. QJM 2017;110:375–8.

- Stubbs DJ, Vivian ME, Davies BM, et al. Incidence of chronic subdural haematoma: a single-centre exploration of the effects of an ageing population with a review of the literature. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2021;163:2629–37.

- Asghar M, Adhiyaman V, Greenway MW, et al. Chronic subdural haematoma in the elderly-a North Wales experience. J R Soc Med 2002;95:290–2. http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=emed7&NEWS=N&AN=34666506

- Mellergard P, Wisten O. Operations and re-operations for chronic subdural haematomas during a 25-year period in a well defined population. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 1996;138:708–13. http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=emed6&NEWS=N&AN=26276563

- Magalhães MJ, da S de Araújo JP, Paulino A, et al. Epidemiology and estimated cost of surgery for chronic subdural hematoma conducted by the unified health system in Brazil (2008–2016). Arq Bras Neurocir 2019;38:79–85.

- Neifert SN, Chaman EK, Hardigan T, et al. Increases in subdural hematoma with an aging population—the future of american cerebrovascular disease. World Neurosurg 2020; 141:e166–74–e174.

- Hutchinson PJ, Edlmann E, Bulters D, et al. Trial of dexamethasone for chronic subdural hematoma. N Engl J Med 2020;383:2616–27.

- Haldrup M, Ketharanathan B, Debrabant B, et al. Embolization of the middle meningeal artery in patients with chronic subdural hematoma-a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2020;162:777–84.

- The Society for British neurosurgeons (SBNS). National Neurosurgical Audit Program (NNAP). Last accessed October 16th 2021. Available from: https://www.sbns.org.uk/index.php/audit

- Santarius T, Kirkpatrick PJ, Ganesan D, et al. Use of drains versus no drains after burr-hole evacuation of chronic subdural haematoma: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2009;374:1067–73.

- Stubbs DJ, Davies BM, Menon DK. Chronic subdural haematoma: the role of perioperative medicine in a common form of reversible brain injury. Anaesthesia 2022; 77 (Suppl 1): 21–33.

- Royal Academy of Engineering. Engineering better care: a systems approach to health and care design and continuous improvement. London: Royal Academy of Engineering; 2017.

- Middleton M. Orthogeriatrics and hip fracture care in the UK: factors driving change to more integrated models of care. Geriatr 2018;3.55.

- The National Emergency Laparotomy Project Team. Fourth Patient Report of the National Emergency Laparotomy Audit (NELA). London; 2018. Available from: https://www.nela.org.uk/reports

- Grigoryan KV, Javedan H, Rudolph JL. Orthogeriatric care models and outcomes in hip fracture patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Orthop Trauma 2014;28:e49–e55.

- NHS Providers. Right place, right time. Better transfers of care: a call to action; 2015. Available from: http://nhsproviders.org/media/1258/nhsp-right-place-lr.pdf

- Bapat S, Shapey J, Toma A, et al. Chronic subdural haematomas: a single-centre experience developing an integrated care pathway. Br J Neurosurg 2017;31:434–8.

- Tools and resources. Stroke and transient ischaemic attack in over 16s: diagnosis and initial management. Guidance: NICE. 2021. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng128/resources [last accessed 11 Mar 2021].

- The ‘Improving Care in Elderly Neurosurgery Initiative’ (ICENI). 2020. Available from: https://www.improving-care.in/neurosurgery[last accessed 4 Dec 2020].

- Straus SE, Tetroe J, Graham I. Defining knowledge translation. CMAJ 2009;181:165–8.

- Royal College of Physicians. The falls and fragility audit program: The National Hip Fracture Database. 2020. Available from: https://www.nhfd.co.uk/ [last accessed 30 Oct 2020].

- JN, CC, RW, et al. The impact of a national clinician-led audit initiative on care and mortality after hip fracture in England: an external evaluation using time trends in non-audit data. Med Care 2015;53:686–91.

- Griffin XL, Achten J, Parsons N, WHiTE orators, et al. Does performance-based remuneration improve outcomes in the treatment of hip fracture? Bone Joint J 2021;103-B:881–7.

- Pickard J, Richards H, Seeley H, et al. UK Shunt Registry Report 2017; 2017. Available from: https://brainhtc.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/UKSRDraftReport2017FINAL.pdf

- Holl DC, Chari A, Iorio-Morin C, et al. Study protocol on defining core outcomes and data elements in chronic subdural haematoma. Neurosurgery 2021;89:720–5.

- National Institute for Academic Anaesthesia Health Services Research Centre. The National Emergency Laparotomy Audit. 2020. Available from: https://www.nela.org.uk/ [last accessed 20 Nov 2020].

- Poulsen FR, Halle B, Pottegard A, et al. Subdural hematoma cases identified through a Danish patient register: diagnosis validity, clinical characteristics, and preadmission antithrombotic drug use. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2016;25:1253–62. http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=med12&NEWS=N&AN=27384945

- Edlmann E, Whitfield PC, Kolias A, et al. Pathogenesis of chronic subdural hematoma: a cohort evidencing de novo and transformational origins. J Neurotrauma. 2021;38:2580–9.

- Christopher E, Poon MTC, Glancz LJ, Hutchinson PJ, Kolias AG, Brennan PM; British Neurosurgical Trainee Research Collaborative (BNTRC). Outcomes following surgery in subgroups of comatose and very elderly patients with chronic subdural hematoma. Neurosurg Rev 2019;42:427–31.

- Whitehouse KJ, Jeyaretna DS, Enki DG, et al. Head injury in the elderly: what are the outcomes of neurosurgical care? World Neurosurg 2016;94:493–500.

- NHS Digital. Secondary Uses Services (SUS). 2021. Available from: https://digital.nhs.uk/services/secondary-uses-service-sus [last accessed 26 Aug 2021].

- Imam T, Konstant-Hambling R, Fluck R, et al. The hospital frailty risk score-outcomes in specialised services. Age Ageing 2021;50:511–8.

- NHS Specialised Clinical Frailty Network. Specialised Clinical Frailty Network. 2021. Available from: https://www.scfn.org.uk/ [last accessed 24 May 2021].

- Centre for perioperative care. Guideline for Perioperative Care for People Living with Frailty Undergoing Elective and Emergency Surgery. 2021. Available from: https://www.cpoc.org.uk/sites/cpoc/files/documents/2021-09/CPOC-BGS-Frailty-Guideline-2021.pdf [last accessed 8 Oct 2021].

- Griffiths R, Babu S, Dixon P, et al. Guideline for the management of hip fractures 2020: guideline by the Association of Anaesthetists. Anaesthesia 2021;76:225–37.

- Venturini S, Fountain DM, Glancz LJ, et al. Time to surgery following chronic subdural hematoma: post hoc analysis of a prospective cohort study. BMJ Surg Interv Health Technologies 2019;1:e000012.

- Scerrati A, Pangallo G, Dughiero M, et al. Influence of nutritional status on the clinical outcome of patients with chronic subdural hematoma: a prospective multicenter clinical study. Nutr Neurosci 2021;5:1–8.doi: 10.1080/1028415X.2021.1895480

- Murthy SB, Wu X, Diaz I, et al. Non-traumatic subdural hemorrhage and risk of arterial ischemic events. Stroke 2020; 51:1464–9.

- MTC P CR, AG K, et al. Influence of antiplatelet and anticoagulant drug use on outcomes after chronic subdural hematoma drainage. J Neurotrauma 2021;38:1177–84.

- Keeling D, Campbell Tait R, Watson H. Peri-operative management of anticoagulation and antiplatelet therapy: a British Society for Haematology Guideline. 2021. Available from: https://b-s-h.org.uk/guidelines/guidelines/peri-operative-management-of-anticoagulation-and-antiplatelet-therapy/ [last accessed 9 Feb 2021].

- Wada M, Yamakami I, Higuchi Y, et al. Influence of antiplatelet therapy on postoperative recurrence of chronic subdural hematoma: a multicenter retrospective study in 719 patients. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 2014;120:49–54.

- Nagalla S, Sarode R. Role of platelet transfusion in the reversal of anti-platelet therapy. Transfus Med Rev 2019;33:92–7.

- Alfirevic A, Downing J, Daras K, et al. Has the introduction of direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) in England increased emergency admissions for bleeding conditions? A longitudinal ecological study. BMJ Open 2020;10:e033357.

- Pollack CV, Reilly PA, Eikelboom J, et al. Idarucizumab for dabigatran reversal. N Engl J Med 2015;373:511–20.

- Piran S, Khatib R, Schulman S, et al. Management of direct factor Xa inhibitor-related major bleeding with prothrombin complex concentrate: a meta-analysis. Blood Adv 2019;3:158–67.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Andexanet alfa for reversing anticoagulation from apixaban or rivaroxaban [TA697]. 2021. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta697/chapter/1-Recommendations [last accessed 24 May 2021].

- Saja K. British Society for Haematology - Haemostasis and Thrombosis Task Force. Addendum to the guideline on the peri-operative management of anticoagulation and antiplatelet therapy. 2021. Available from: https://b-s-h.org.uk/media/19825/addendum-to-the-guideline-on-peri-operative-management-of-anticoagulation-and-antiplatelet-therapy.pdf [last accessed 26 Aug 2021].

- Ondexxya 200 mg powder for solution for infusion - Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC) - (emc). Eur. Med. Compend. 2021. Available from: https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/10933/smpc#gref [last accessed 24 May 2021].

- Scottish Medicines Consortium. Andexanet Alfa. 2021. Available from: https://www.scottishmedicines.org.uk/medicines-advice/andexanet-alfa-ondexxya-full-smc2273/ [last accessed 24 May 2021].

- Almenawer SA, Farrokhyar F, Hong C, et al. Chronic subdural hematoma management: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 34,829 patients. Ann Surg 2014;259:449–57.

- Guilfoyle MR, Hutchinson PJA, Santarius T. Improved long-term survival with subdural drains following evacuation of chronic subdural haematoma. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2017;159:903–5.

- Dakurah TK, Iddrissu M, Wepeba G, et al. Chronic subdural haematoma: review of 96 cases attending the Korle Bu Teaching Hospital, Accra. West Afr J Med 2005;24:283–6.

- Phang I, Sivakumaran R, Papadopoulos MC. No association between seniority of surgeon and postoperative recurrence of chronic subdural haematoma. annals 2015;97:584–8.

- Chelvarajah R, Lee JK, Chandrasekaran S, et al. A clinical audit of neurosurgical bed usage. Br J Neurosurg 2007;21:610–3.

- Chari A, Clemente Morgado T, Rigamonti D. Recommencement of anticoagulation in chronic subdural haematoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Neurosurg 2014;28:2–7.

- Guha D, Coyne S, Macdonald RL. Timing of the resumption of antithrombotic agents following surgical evacuation of chronic subdural hematomas: a retrospective cohort study. JNS 2016;124:750–9.

- The British Society of Rehabilitation Medicine. Specialist neuro-rehabilitation services: providing for patients with complex rehabilitation needs. Last accessed 16th October 2021. Available from: https://www.bsrm.org.uk/downloads/specialised-neurorehabilitation-service-standards–7-30-4-2015-forweb.pdf

- Kwon CS, Al-Awar O, Richards O, et al. Predicting prognosis of patients with chronic subdural hematoma: a new scoring system. World Neurosurg 2018;109:e707–e714.

- Edlmann E, Holl DC, Lingsma HF, et al. Systematic review of current randomised control trials in chronic subdural haematoma and proposal for an international collaborative approach. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2020;162:763–76.

- Moran CG, Lecky F, Bouamra O, et al. Changing the system - major trauma patients and their outcomes in the NHS (England) 2008-17. EClinicalMedicine 2018;2–3:13–21.

- van der Scheer, J.W., Woodward, M., Ansari, A., Draycott, T., Winter, C., Martin, G., Kuberska, K., Richards, N., Kern, R. and Dixon-Woods, M., 2021. How to specify healthcare process improvements collaboratively using rapid, remote consensus-building: a framework and a case study of its application. BMC medical research methodology, 21(1), pp.1–16.

- Moffatt CE, Hennessy MJ, Marshman LAG, et al. Long-term health outcomes in survivors after chronic subdural haematoma. J Clin Neurosci 2019;66:133–137. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2019.04.039.

- Dumont TM, Rughani AI, Goeckes T, et al. Chronic subdural hematoma: a sentinel health event. World Neurosurg 2013;80:889–92. http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=emed14&NEWS=N&AN=52644318

- Bothwell LE, Greene JA, Podolsky SH, et al. Assessing the gold standard-lessons from the history of RCTs. N Engl J Med 2016;374:2175–81.

- Oyinlola JO, Campbell J, Kousoulis AA. Is real world evidence influencing practice? A systematic review of CPRD research in NICE guidances. BMC Health Serv. Res 2016;16:299.

- Williams I, Bryan S, McIver S. How should cost-effectiveness analysis be used in health technology coverage decisions? Evidence from the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence approach. J Health Serv Res Policy 2007;12:73–9.

- Lewis SC, Warlow CP, Bodenham AR, et al. General anaesthesia versus local anaesthesia for carotid surgery (GALA): a multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2008;372:2132–42.