Abstract

Introduction

Although mostly used in the management of spinal trauma, hard collar immobilisation is also used as an adjunct to recovery after elective cervical spine surgery. Many surgeons believe that bracing reduces the risk of non-union and pain and provides a subjective sense of security for patients. There is little if any, evidence for this practice and immobilisation can be a direct cause of adverse events. The primary aim of this study was to provide an updated assessment of post-operative bracing practice in UK spinal surgeons, including the indications, rationale and perspectives on compliance and complications.

Methods

Neurosurgeons and spinal orthopaedic surgeons completed a web-based survey distributed by email to members of the Society of British Neurological Surgeons (SBNS) and the British Association of Spinal Surgeons (BASS). Professional information captured included level of experience and whether surgeons had a specialist interest in spinal surgery. Questions first focused on the frequency and duration of hard collar immobilisation for common decompressive procedures. Later questions captured surgeon rationale, perceptions of patient compliance, complications, and collar removal.

Results

A total of 86 surgeons completed the survey, of whom 83% were spinal specialists. In total, 33 (38%) surgeons recommend a hard collar following at least one of the elective procedures listed. Collars were most commonly recommended following cervical corpectomy (30%). The support of fusion and bone healing was the most common rationale (82%), with post-operative pain (45%) and limiting patient activity (39%) also considered. Most surgeons (69%) believed that their patients were compliant. All listed types of complications were reported, with impaired activities of daily living (41%) and impaired sleep (34%) the most frequently cited.

Conclusions

Current post-operative use of hard collars is much lower in the United Kingdom than previously reported in the United States. Surgeon decision-making is inconsistent and may benefit from greater standardisation. Future work is needed to help develop guidelines as a move away from arbitrary to evidence-based practice.

Introduction

Cervical bracing, otherwise known as cervical orthosis or a hard collar immobilisation, is commonly used as part of spinal care in trauma,Citation1 but may also be used as an adjunct to recovery after elective cervical spine surgery. Anecdotal reports suggest elective use is justified in the expectation that bracing reduces the risk of non-union and pain and provides a subjective sense of security for the patient. Whilst these assumptions are widely held, a growing body of evidence suggests that hard collar immobilisation is unnecessary for certain post-operative indications. For example, in comparative effectiveness studies after anterior cervical discectomy and fusion (ACDF), clinical outcomes are not significantly different in the absence of a hard collar.Citation2–4

Conversely, deliberate cervical immobilisation restricts the range of motion post-operativelyCitation5 and risks impeding long-term function. In addition, hard collars can directly cause adverse events, including pressure ulceration of the skin, dysphagia and increased intracranial pressure.Citation6,Citation7 The use of hard collars, therefore, has disadvantages, and the benefit of their use should be proven, considering both cost and patient outcomes. This is a common source of enquiry at Myelopathy.org, a charity for Degenerative Cervical Myelopathy.Citation8

There is limited evidence about the current frequency of hard collar use in the UK. Previous studies have come from North AmericaCitation9 or are restricted to specific procedures such as ACDF.Citation10 These studies were also before the comparative effectiveness studies.Citation2–4

The primary objective of this study was to provide a contemporary assessment of post-operative bracing practice in the UK including surgeon perceptions of complications. Capturing practice preferences and diversity will help inform whether guidance on use for professionals and/or patients, might be useful.

Methods

The survey was designed and is reported following the Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys (CHERRIES).Citation11

Survey design

A cross-sectional observational study was conducted using a web-based survey targeted at surgeons who operate on the cervical spine. The survey questions can be found in Supplementary Material 1. Questions captured surgeons' level of training and for which procedures they would employ post-operative bracing, specifically looking at the consistency of these decisions and the duration of immobilisation. Further questions assessed surgeon reasoning in the decision to use a hard collar, along with surgeon perceptions of complications and factors affecting compliance. The question format was a combination of multiple-choice questions, matrix questions and Likert scale questions.

Ethical approval and consent

As this was a survey of clinicians, ethical approval was not required. Participants completed the survey voluntarily and were informed before doing so that anonymised data would be shared with researchers associated with the charity Myelopathy.org for the purposes of academic research. This acted as voluntary electronic consent, with completion of the survey questions taken as agreement to participate.

Development and testing

The usability and technical functionality of the survey were piloted before dissemination.

Data protection

No patient identifiable information was stored. The minimum amount of data was securely stored and accessed by the minimum number of researchers for the minimum amount of time required to complete the research.

Participants

All participants were practicing neurosurgeons or spinal orthopaedic surgeons in the United Kingdom or the Republic of Ireland.

Recruitment

An open survey type was used. Surgeons were recruited to a web-based questionnaire, administered by SurveyMonkey. The survey was disseminated via email directly to the members of the Society of British Neurological Surgeons (SBNS) and was advertised in the British Association of Spinal Surgeons (BASS) newsletter. No contact was made with participants outside the survey.

Administration

The SBNS is the primary professional association for UK neurosurgeons and BASS is a leading organisation for UK spinal surgeons of either neurosurgical or orthopaedic training. BASS is a specialist sub-group of the British Orthopaedic Association. There was no sample pre-selection. The survey was administered by email. Completion of the survey was voluntary and no incentives were offered. Adaptive questioning was employed to reduce complexity and respondents were able to review their answers by using a ‘Back’ button. Responses were collected from 2nd June 2021 to 26th September 2021.

Response rates

In June 2021, there were 660 members of the SBNS and 460 members of the BASS. As 86 participants completed the survey, the maximum response rate was 16%, The completion rate, i.e. the number of completed surveys relative to the number of respondents who entered the survey, was calculated by SurveyMonkey to be 30%. IP addresses were recorded as metadata with each survey response, allowing assessment for duplication and preventing multiple entries from the same individual.

Data analysis

Survey data were extracted into an Excel spreadsheet (Microsoft, California, USA). Analysis and data visualisation were performed using R (v4.0.5; R Core Team, 2020) and RStudio (v1.4.1106; RStudio Team, 2021). Incomplete responses were excluded from the analysis, except in cases where incomplete questions were independent of those answered.

Results

Summary

A total of 86 practicing neurosurgeons and spinal orthopaedic surgeons participated in the survey. Of this group, 71 (83%) considered themselves to be a surgeon with a specialist interest in spinal surgery. Responses came mostly from experienced surgeons: 9 (10%) were still in training, 16 (19%) were under 5 years post-training, 23 (27%) were 5–15 years post-training, and 39 (45%) were more than 15 years post-training. The average completion time of the 5-minute survey was 37 seconds, suggesting a high number of respondents with early survey termination, which was designed to occur if respondents did not routinely use hard collars, as the later questions were then irrelevant.

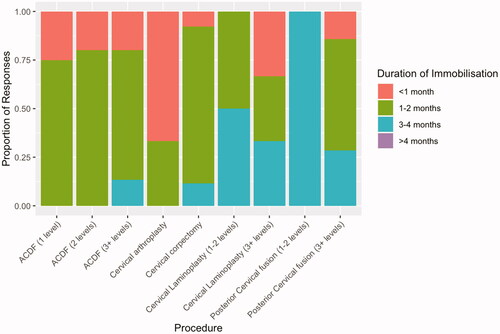

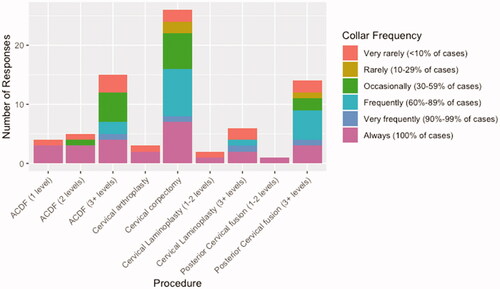

Post-operative hard collar frequency

In total, 53 (62%) surgeons reported that they never use post-operative bracing following any of the listed surgical procedures (). Such responses terminated the survey at question 3 of 11. Hard collars are often used following cervical corpectomy, with 26 (30%) of surgeons reporting the use of a post-operative hard collar. Following single-level ACDF, a post-operative collar was considered by 4 (5%) surgeons. The frequency of hard collar use post-ACDF increased with the number of vertebral levels involved. The majority of surgeons using a collar following 1 or 2 level ACDF opted for a collar with every patient. A cervical hard collar was less frequently used for posterior approaches to cervical decompression than anterior approaches.

Figure 1. Frequency of hard collar use following common cervical decompressive procedures, excluding responses with a collar frequency of ‘Never’.

There was no significant difference in the frequency of post-operative hard collar use when surgeons were divided by experience level or specialist interest (Supplementary Material 2). All analysis hereafter includes only the 33 (38%) surgeons that recommend a hard collar following any of the listed procedures.

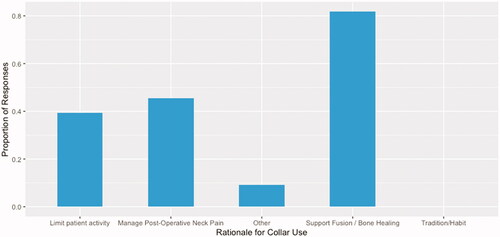

Duration of post-operative immobilisation

The average duration of immobilisation () was the longest for posterior cervical fusion (3+ levels) and cervical laminoplasty (3+ levels). This analysis includes only those procedures for which there were more than 3 surgeon responses. Following ACDF, the duration of immobilisation increased with the number of vertebral levels involved. For all ACDF procedures, surgeons most commonly reported an immobilisation duration of 1–2 months.

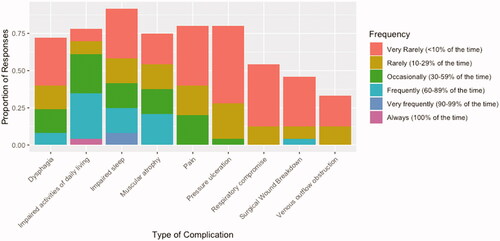

Rationale for immobilisation

The most common reason for considering a post-operative collar was to support fusion and bone healing. This was reported by 27 (82%) of the surgeons who use post-operative bracing (). The management of post-operative pain and the limitation of patient activity were also important factors for 14 (45%) and 13 (39%) surgeons, respectively.

Incomplete responses to questions concerning complications and compliance mean that the following analysis is limited to 26 responses. Regarding patient-specific factors, 13 (50%) respondents reported that trauma would influence their decision to immobilise. Just 3 other factors were selected by more than a quarter of surgeons: osteopenia/osteoporosis (10, 38%), frailty (7, 27%), patient’s capacity (7, 27%) and revision surgery (7, 27%).

Patient compliance

Most surgeons (18, 69%) agreed or strongly agreed that their patients were compliant when asked to wear a hard collar post-operatively. Seven (27%) responses were neutral and only 1 surgeon disagreed. When asked about factors influencing compliance, most surgeons reported that discomfort (17, 65%) and hygiene/supply of replacement pads (14, 54%) were important. Four further factors were selected by more than a quarter of surgeons: duration of wear indicated (13, 50%), allowances for intermittent removal (13, 50%), adequate counselling on rational for use (11, 42%) and the type of surgical intervention (7, 27%). Patient-specific factors, such as age, gender and socioeconomic status, were reported as an important group of factors by 9 (35%) surgeons. Only 4 (15%) surgeons believed that restrictions on activities influenced patient compliance.

Hard collar complications and side effects

Every suggested type of hard collar complication or side effect was observed by the participating surgeons (). Impaired activities of daily living (41% of patients) and impaired sleep (34% of patients) were the most frequently reported. Venous outflow obstruction was observed least frequently (4% of patients).

Hard collar removal

Most surgeons (15, 58%) reported advising phased withdrawal of the hard collar, with specific instructions. A phased withdrawal, at the discretion of the patient, is advised by 7 (27%) surgeons. Lastly, no specific advice is routinely provided by 3 (12%) of the responding surgeons.

Discussion

Our results suggest that a minority of UK-based surgeons use hard collars after elective cervical spine procedures. Where collars are used, specific indications are mixed, but they are generally used to support fusion and bone healing. Regarding patient experience, the perceived factors influencing hard collar compliance appear largely modifiable.

The use of post-operative bracing is at odds with a similar survey conducted largely amongst spinal surgeons in the US.Citation9 Bible et al sampled surgeons practicing primarily in the US and found that hard collar immobilisation is used following 25–56% of ACDF procedures, again depending on the number of vertebral levels. Cervical bracing is also used following most cases of cervical corpectomy and multilevel posterior cervical decompression and fusion. However, the UK results are more closely aligned with a recent study from Canada,Citation10 which investigated cervical bracing post-ACDF, where the frequency of hard collar use in ACDF cases was low (30%) compared to the American study.

These differences may reflect the adaptation of practice to emerging evidence. Numerous studies have found that cervical immobilisation leads to no significant differences in post-operative outcomes.Citation2–4 On the other hand, it is known that hard collars cause adverse events, such as pressure ulceration, dysphagia and cervical deconditioning.Citation6,Citation7

However, these differences may be more heavily influenced by differing surgical cultures. In our UK survey, of the few surgeons that reported using hard collars, a large portion selected ‘always’ when estimating the frequency of use. This was especially true for procedures such as arthroplasty and posterior fusion (), which are favoured in North America. With limited evidence for procedures aside other than ACDF, differing surgical preferences, long-established practice and fear of litigation,Citation12 are likely to be the main drivers for greater post-operative bracing in the US.

The variation in practice is a strong indicator of a lack of evidence.Citation7 A lack of consensus is also present when considering the rationale for post-operative immobilisation. Eighty per cent cite bracing to support bone fusion, 45% of surgeons aim to reduce post-operative neck pain and 39% hope to limit patient activity by using a hard collar. This inconsistent rationale is aligned with findings from the US,Citation9 where 51% of surgeons aim to ‘slow down’ the patient (i.e. limit mobilisation) and 38% hope to improve post-operative pain. These findings are consistent with anecdotal reports of patients receiving conflicting advice from members of the same surgical team.

The decision to immobilise post-operatively will also be influenced by the mechanism of injury, such as cases of acute trauma, which was not considered in this survey. The qualitatively different nature of such an insult compared to chronic degeneration can further complicate decision-making.

Such inconsistencies can only be resolved with evidence, and therefore further studies are required to inform practice. Whilst it is not a study of collar use for elective indications, the recently commissioned DENS randomised controlled trialCitation13 is a promising investigation in this area, which will evaluate collar vs no collar following odontoid fractures in the elderly. The need for further studies is reinforced by the morbidity reported by surgeons, which exceeded currently published prevalence data.Citation6,Citation7 For example, a quarter of surgeons reported that 10–60% of patients develop pressure ulcers when wearing a post-operative hard collar, while cohort studies report a pressure ulcer prevalence under 10%.Citation6,Citation7 This may indicate surgeon vulnerability to recall bias, but given the low-quality cohort studies around adverse events, this too indicates the potential value of a prospective trial.

In the short term, it appears collars are likely to remain a part of elective spinal surgical practice. Although surgeons largely perceived that patients with hard collars are compliant (69%), several modifiable factors were identified, including hygiene/the supply of replacement pads (54%) and counselling on the rationale for use (42%). Further allowances for intermittent removal (50%) were popular and should be promoted, in light of emerging evidence.Citation2–4 To our knowledge, little specific aftercare exists for patients in or transitioning out of hard collars. Taken together, this suggests there is scope to optimise the indications for cervical immobilisation but also develop strategies to minimise any adverse effects.

Limitations

These survey results may be subject to recall bias. Further, despite dissemination through the leading national neurosurgical and spinal surgery organisations, only a small proportion of practicing UK spine surgeons participated, potentially leading to a selection bias. Of note, more experienced surgeons were slightly overrepresented, as 50.6% of respondents reported 15+ years of post-training experience, while the most recent surgeon census reported that only 36.9% of neurosurgeons were aged >50 years.Citation14

If surgeons did not routinely use a hard collar for at least one procedure listed, they were removed from the survey. Whilst this limited the ability to share perspectives on compliance and morbidity, this ensured perspectives were restricted to those surgeons routinely using and therefore caring for patients within a collar.

Conclusions

There is a lack of consensus on the use of cervical collars after elective cervical surgery in the UK. Whilst the majority do not routinely use them, some surgeons do, particularly for corpectomy and multi-level fusion procedures. Despite this, the observed morbidity is reportedly high. Future studies are needed to help develop standardised guidelines, enhance factors influencing patient compliance and understand patient experiences.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (92.4 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (663.5 KB)Disclosure statement

This report is independent research arising from a Clinician Scientist Award, CS-2015-15-023, supported by the National Institute for Health Research. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the National Institute for Health Research or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Frohna WJ. Emergency department evaluation and treatment of the neck and cervical spine injuries. Emerg Med Clin North Am 1999;17:739–91.

- Campbell MJ, Carreon LY, Traynelis V, Anderson PA. Use of cervical collar after single-level anterior cervical fusion with plate: is it necessary? Spine 2009;34:43–8.

- Camara R, Ajayi OO, Asgarzadie F. Are external cervical orthoses necessary after anterior cervical discectomy and fusion: a review of the literature. Cureus 2016;8:e688.

- Iizuka H, Nakagawa Y, Shimegi A, et al. Clinical results after cervical laminoplasty: differences due to the duration of wearing a cervical collar. J Spinal Disord Tech 2005;18:489–91.

- Tescher AN, Rindflesch AB, Youdas JW, et al. Range-of-motion restriction and craniofacial tissue-interface pressure from four cervical collars. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2007;63:1120–6.

- Powers J, Daniels D, McGuire C, Hilbish C. The incidence of skin breakdown associated with use of cervical collars. J Trauma Nurs 2006;13:198–200.

- Brannigan J, Dohle E, Laing R, et al. Adverse events relating to prolonged hard collar immobilisation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Glob Spine J 2022.

- Davies BM, Mowforth OD, Smith EK, Kotter MR. Degenerative cervical myelopathy. BMJ 2018;360:k186.

- Bible JE, Biswas D, Whang PG, et al. Postoperative bracing after spine surgery for degenerative conditions: a questionnaire study. Spine J 2009;9:309–16.

- Baweja RK, Bennardo M, Farrokhyar F, et al. A Canadian perspective on anterior cervical discectomies: practice patterns and preferences. J Spine Surg 2018;4:72–8.

- Eysenbach G. Improving the quality of web surveys: the checklist for reporting results of internet E-surveys (CHERRIES). J Med Internet Res 2004;6:e34.

- Guardado JR. Policy Research Perspectives Medical Liability Claim Frequency Among U. S. Physicians. 2018. Available from: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Policy-Research-Perspectives-Medical-Liability-U-.-Guardado/88a23279a327c110dc67e325c158ef7050098eea [last accessed November 1, 2021].

- NIHR Funding and Awards Search Website. Available from: https://fundingawards.nihr.ac.uk/award/NIHR131118 [last accessed October 10, 2021].

- [email protected]. Surgical Workforce Census Report. Royal College of Surgeons. Available at: https://www.rcseng.ac.uk/library-and-publications/rcs-publications/docs/surgical-workforce-census/ [last accessed January 26, 2022].