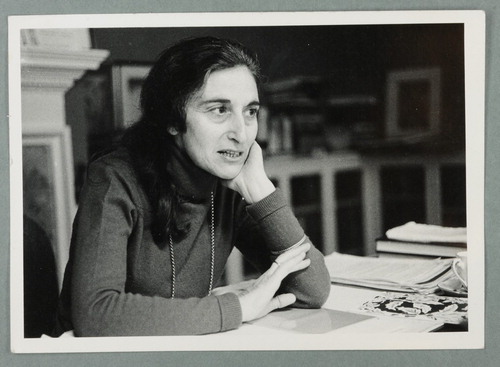

The novel, short story and screenplay writer Ruth Prawer Jhabvala died in 2013 and bequeathed her literary papers to the British Library in London. There they joined the Contemporary Collections which include the literary archives of Angela Carter, Harold Pinter, Shiva Naipaul and Hanif Kureishi. Prawer Jhabvala’s rich sixty-year contribution to literature and film won her the accolade, unchallenged to date, as the only person to have a Booker Prize (for Heat and Dust, 1975) and two Oscars (for adapting A Room with a View in 1987 and Howards End in 1993). She also received a BAFTA for adapting Heat and Dust in 1984, and its Fellowship in 2002; the Guggenheim Fellowship for Creative Arts (1976); the Neil Gunn Fellowship (1979); the MacArthur Fellowship in 1984; and the O Henry Prize for the short story in 2005. The transnational recognition she received was a testament to the multifaceted aspects of her career in both film and prose.

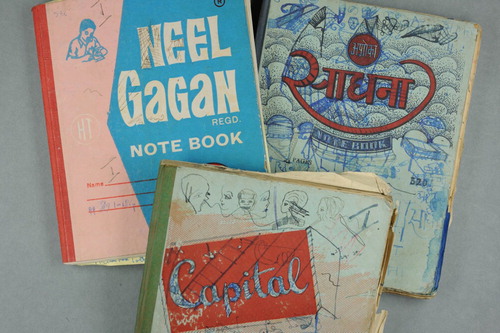

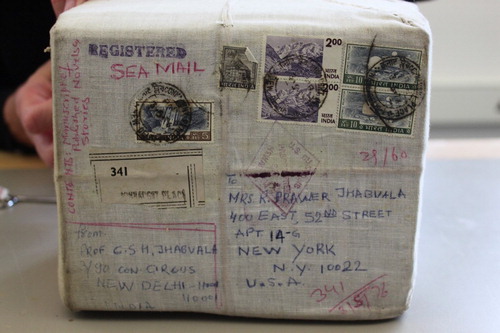

The library received her papers in 2014 and listed them as Deposit 10770, which consisted of eleven boxes. Opening these boxes for the first time offered a valuable opportunity to get a full sense of her contribution to prose literature. They allowed us to assess a range of drafts, typescripts, manuscripts and correspondence, and analyse what their contents can add to knowledge about her work beyond her published and visual media. One of these boxes contained four tightly filled cuboid packages. Each of these packages was wrapped in an off-white cotton material, covered with postage stamps, all dated and franked in 1976. The sending address from Delhi and the destination address in New York were written in blue and red ink. Stitched to one side of each package with fine thread were customs declaration forms, yellowed and fragile. This extremely fine stitching also ran along the sides of the packages to ensure that each one and its contents were held intact. The condition of these exceptional objects was assessed by Liz Rose, a textile conservator from the Collection and Conservation studio at the British Library. The manifest list described them simply as: ‘Linen packets’ and numbered them 1–4. This mundane description, which was of practical use for insurance purposes for their transportation, belied an aesthetic allure and fascination which these tactile solid objects held on first sight.

Figure 2. Packages from Prawer Jhabvala’s literary archive being examined in the Conservation studio at the British Library. Image © British Library Board.

Prawer Jhabvala’s daughter Ava, Ava’s husband Laurie and I witnessed Liz Rose opening the first of the packages in the Library’s Conservation studio on Friday, 13 October 2017. This package was the most mysterious of all four because its contents were not listed on its exterior. The other three were labelled to indicate that they held material related to: her first novel To Whom She Will (1954); her first short story collection, Like Birds, Like Fishes (1963); A Stronger Climate (1968); Bombay Talkie (a story that became an original screenplay in 1970); and the collection An Experience of India (1971). All of these had characters anchored in the milieu of urban India; some of whom were Western seekers, but most represented an emerging Indian middle class.

Having witnessed the opening of this particular package, I wondered about the complete history and journeys of all four of these objects. Each of the writer’s daughters, Renana, Ava, and Firoza remembered different aspects about their travel and storage history and they all shared their memories with me. I became acutely conscious of a list of participants who actively contributed to the first careful enclosure of what turned out to be Prawer Jhabvala’s notebooks, in Delhi. I was attentive to the importance of their storage and preservation in New York and the spaces they required until receiving their current housing arrangements and conservation at the British Library. Above all else, I identified that these cuboid packages told a narrative about the passage of time, about places and people, and possessed a powerful authority which distinguished them from the other items in this collection. I wanted to decipher their narrative and assess its significance in light of Prawer Jhabvala’s transnational life as a writer.

After almost three hours of unpicking stitches in October 2017, Liz Rose revealed eight hardbacked notebooks which were the first handwritten drafts of the novels Esmond in India (1958) and The Householder (1960). The former was Prawer Jhabvala’s second published novel which featured an unsuccessful cross-cultural marriage set in the early days of new postcolonial India. It was dramatised by Namita Ghose on BBC Radio 4 in 2000 (BBC Genome). The latter was a story of a newly married teacher detailing his inner life and social responsibilities and it displays Prawer Jhabvala’s acute awareness of the strains and expectations of middle-class Indians struggling with modernity and traditions. It was The Householder that brought James Ivory to seek out Prawer Jhabvala in Delhi, and her film adaptation in 1963 was the first in the long, successful Merchant Ivory collaboration. The novel was read in instalments on BBC’s Woman’s Hour in 1961 and was adapted for BBC 2’s Storytime by Zoe Bailey (BBC Genome) twenty years later (1981).

A writer’s first ideas in ink which germinate into a literary work are considered significant in themselves for the insight into the writer’s craft and work practices they provide. This was an idea I was exploring in my thesis within the concept of genetic criticism. Likewise, is there significant aesthetic value embodied within the notebooks on which these literary works are written? Can receptacles, like these cotton packages, in which the ideas and kernels of novels and short stories are transported, also hold their own cultural value? This might differ from Gérard Genette’s concept of the paratext where the interpretation of the published work is extended beyond a threshold into the paraphernalia that surrounds it. After all, these were handwritten drafts or ‘pre-texts’. What does paying attention to how and where the notebooks are stored tell us about their cultural value? The notebooks’ journeys, through various homes, across three continents, truly echoed Prawer Jhabvala’s own transnational life. Could tracing the routes of the packages of her earliest drafts and the lived places and spaces they shared with the diasporic writer help illuminate their value as meaningful objects among her creative output? Above all, what could they tell us of some of the spaces in which she worked?

Moving Things, Changing Places

I was inspired to answer these questions by a section called ‘Every Object Tells a Story’ which looks at examples of items and their connections with people’s diasporic lives located within Kim Knott’s findings in the research programme Moving People Changing Places carried out in the UK between 2010 and 2015. Knott's study examines the connections between migration, diaspora and people’s belongings, connections that are clear in Prawer Jhabvala's story.

Ruth Prawer, born in 1927, of Polish German Jewish heritage, had lived in England since the age of twelve after she arrived as a refugee from Cologne. She travelled to India in 1951 with her husband Cyrus Jhabvala, whom she met while at university in London. Prawer Jhabvala never returned to Germany; her extended family lost over forty of their members in the Holocaust and the few who survived moved to Britain, the United States and Israel. It is fitting to describe her as diasporic, as ‘diaspora’ was first used over 2,000 years ago to describe the separateness of the Jewish people, but now describes those who live outside the places in which they were born. It is also fitting to call her a ‘transnational’ writer. The term ‘transnational’ has had its meaning extended by Peggy Levitt far beyond the idea of crossing boundaries and nations which would also serve my purpose here. Levitt applies it also to a gaze and perspective, a way of understanding the world, where boundaries and the relationships and processes which happen at these margins are examined. Prawer Jhabvala in her writings deals with cultural boundaries and cultural clashes, while also inhabiting characters from other cultures, in settings such as India and the United States. Neither of these cultural environments are those into which she was born or spent her formative years.

She published her first novel, which was written in India, in 1954. The Jhabvala family moved many times within Delhi: from their first home in the early 1950s in Pusa Road, to rented rooms in a house on Ram Kishore Road. Cyrus (known as ‘Jhab’) then built their own larger family house on Rajpur Road which was later sold for a home that he had designed himself on Flagstaff Road. It was from here that the Jhabvalas made the final Delhi move to Alipur Road. At each of these locations Prawer Jhabvala amassed her manuscripts and notebook drafts. Between 1954 and 1976, the year these packages were sent to New York, she had already published nine novels and four short story collections, many stories in journals and magazines and six screenplays including an adaptation of her own work. At this point she was less than half-way through her writing career.

The writer’s eldest daughter Renana Jhabvala shared details of how these particular packages came about and where their journey started. These notebooks packed inside their thailis (the term used by Renana for the cotton packaging which means ‘pouch’ or ‘bag’ in Hindi) were posted from their father’s architecture company’s first office, Anand Apte and Jhabvala, based in Connaught Place, in Delhi on 11 May 1976. This was before their premises moved to a flat on Alipur Road, below one which the Jhabvalas bought as a residence.

Delhi Drafts

In Jhab’s office in 1976, the notebooks were measured by both Mr Dhan Singh, who was the office peon, and by Mr Kapoor, the bookkeeper and administrator. Based on their calculations, they bought a roll of cotton cloth and Dhan Singh and Mr Kapoor stitched a thaili (in the shape of a cube) into which the notebooks would fit tightly. To this day, cotton is still used as a material for transporting paper in India. In 1976, cotton was cheap, it was strong and hard-wearing, ubiquitous and practical. The notebooks were first wrapped in thin black plastic, tied with orange fine string and placed within the prepared thaili. Lastly, the thaili was sewn up securely with thread and a fine needle. This process was completed for four sets of notebooks.

The office secretary Miss Manchanda signed the customs forms. The other details on the packages, including the addresses of the sender and addressee with the description of contents would have been either in her hand or that of Mr Kapoor, as Dhan Singh was not literate. Mr Singh, now in his eighties and living as a reluctant retiree in the hilly area of Uttarakhand, remembers carrying out the task which he recounted to Renana. He continued his employment in her office, after her father retired. Mr Guglani, who was the office manager then, possibly oversaw such operations but was unlikely to have handled the packages. Dhan Singh had the important role of taking the packages to the post office to purchase stamps and to witness the correct franking of each stamp. This held some guarantee against theft and some assurance against delays or possible non-delivery. The packages were all marked ‘Sea mail’. There is no indication of how long they took to travel.

New York, New Space

Prawer Jhabvala had been travelling to and from New York since the early 1970s, but according to her daughter Firoza, she had no place of her own there and stayed with her film collaborators and friends, Ismail Merchant and James Ivory, and later in a small serviced apartment.

Between 1975 and 1977, when these items were first posted, Indira Gandhi’s Emergency was in effect in India. It was a time of strict regulation, curtailment of human rights and censorship. There were rules about time spent in India for those who were frequent travellers, so movement back and forth between India and the United States was restricted for writers like Prawer Jhabvala during this period. In handwritten correspondence dated December 1974, she tells her publishers of her decision about the new title, Heat and Dust. This was to be her last novel written while living in India. She claims:

I can no longer take such prolonged immersions into India. And to think that once eight years at a stretch was nothing to me — I didn’t even notice! But those times are gone. (John Murray Archive)

The packages arrived safely at Jhab and Ruth’s rented studio apartment on East 52nd Street in 1976. This particular apartment was another place of transitional residence for the packages, for their contents and for members of the family. Both Ava and Firoza remembered this rented studio with its many wardrobes with ample storage space in which these packages were placed.

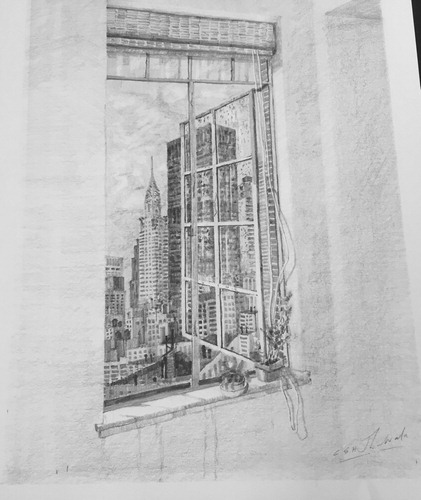

The apartment offered wonderful views of the Chrysler building from the writer’s bed and, according to Ava, her mother also enjoyed the view of a tree which grew from the courtyard on the ground floor. The apartment was sunny and airy. In a letter to John Murray publishers dated March 1976, Prawer Jhabvala describes the feeling of being so high up in the city:

It’s more like being in the mountains than any other place I’ve ever been, except the mountains themselves (those huge white skyscrapers all around are like the Himalayas). I can see a bit of the East River from my terrace as well. (John Murray Archive)

Figure 5. Photo of C S H Jhabvala’s drawing of the view of the Chrysler building, illustration from My Nine Lives Chapters of a Possible Past (published by John Murray, 2004). Image © Ruth & Cyrus Jhabvala LLC.

The Jhabvalas rented this studio in the same block in which James Ivory and Ismail Merchant also lived. Prawer Jhabvala wrote again to her publishers in London in March 1976 of her lack of time to read and write because of the disruption of the move. She was still ‘in confusion and upheaval’ as she had the uncongenial task of a lease to deal with and she also complained: ‘I didn’t have one single stick of furniture nor teaspoon nor absolutely anything so you can imagine what I’ve been having to do’ (John Murray Archive). This rental was considered an expensive decision by her daughters at the time but one that paid off, as the rent was controlled, and twelve years later, in 1988, the residents were offered a discount rate to purchase in the same block. The Jhabvalas later bought a one-bedroomed apartment there.

In this space, Prawer Jhabvala wrote at a desk in the bedroom while Jhab worked in the living room. Her books, including the packages, were moved there, as her library and manuscripts had started to outgrow the spaces already provided.

In a letter written three months later from Prawer Jhabvala to John Murray publishers dated 16 June 1976, she mentions how it is her wedding anniversary but Jhab is in India and she is keeping herself busy on a screenplay of ‘A Holy Mother’ so that she doesn’t get too lonely. This indicates that she and her belongings are now settled enough to allow her to work. The screenplay emerged from a short story called ‘How I Became a Holy Mother’ which became the title of a collection of short stories published in 1975. She also announces here that her daughter, Ava, would be bringing over her Booker Prize trophy for the new apartment in July. She won this Award for Heat and Dust in 1975, and Ava stressed how much the prize money of £5,000 meant to her mother. Prawer Jhabvala told the writer Paul Scott that it was spent on furnishings for the New York apartment. Her hard work and perseverance in fiction took considerable time to gain wider public recognition and the financial rewards from this work seemed to have taken even longer. All of this greater financial security directly supported the writer’s ability to feel at home in her surroundings, an environment which she made congenial for creative work.

Creative work and family life coexisted while the family’s living spaces needed to accommodate Prawer Jhabvala’s reading materials and writing work. Her daughter Ava recalled one entire wall in the apartment lined with shelves and cupboards. Firoza also remembered deep closets in both apartments. The second apartment was a space where the whole family were accommodated on sofa beds and futons when they came to stay. Prawer Jhabvala was still able to have her independent space and kept up her writing routine in the morning hours. Her daughter Firoza recounted spending a lovely summer there but always found something to do in the mornings so that her mother could work in silence. Firoza also remembers that the closet was the only place for a young woman to speak privately to her friends on the landline.

It was not until 2010 that the Jhabvalas were in the financial position to purchase an adjoining studio apartment where the increasing number of family members of the next generation could be accommodated. Ava remembers shopping trips with her parents in New York to buy items with which to furnish this additional studio. It was to this new and final location that Firoza remembers helping her father move his and his wife’s expanding collection of books and papers. This apartment was already furnished with bespoke shelves and cupboards which extended the full length of one wall. It was within these that both of Jhab and Ruth’s legacies were stored, and in the latter’s case, they included these packages.

Firoza describes her father as ‘the master of organising small spaces’, while her mother was ‘practical’ to the end and had worked out the details in advance about where the packages were to go after she died. They were sent with the rest of her literary papers to the British Library after her death in 2013. Cyrus Jhabvala died the following year, 2014, in Los Angeles, where he had moved to live with his daughter Firoza.

London Library

At an event called Ruth Prawer Jhabvala: A Celebration held at the British Library on 3 July 2018, Ava described how her mother’s papers were collected and shipped from New York to London in 2014. What she, her husband Laurie and I witnessed when Liz Rose opened the thaili at the Conservation studio in 2017 was a complete reversal of the process carried out by Dhan Singh and Mr Kapoor forty-one years earlier. Liz used medical tools for precision: curved and straight dissecting micro-forceps, dissecting scissors, a mounted curved needle and stainless-steel spatulas. These instruments allowed her to meticulously unpick the threads from the top part of the parcel so that the next layer of black plastic with string could be unwrapped. She opened the remaining cotton packages at a later date and the notebooks she found there, and the empty outer cotton layer, are now preserved in acetate boxes. She refilled one of these with a foam material and re-stitched it so that one package remains as a complete object with the original external information. The unravelling of the story of the packages’ journey mirrored the physical unpeeling of layers of material in which they were packed.

Figure 6. Liz Rose opening a package at the British Library Conservation studio 2017. Image © British Library Board.

When the first cotton thaili was carefully opened in 2017 and the notebooks were revealed to us for the first time, the objects held some essence of ‘magic’. The innate significance they represented was reflected in the difficult unwrapping process and the suspense this created, but was also embellished by all the information which the outer thaili contained. The markings told the story of some of the places from which the drafts had travelled and gave only clues to the people who participated in their journey. This added an even greater poignancy to the contents of the notebooks, Ruth Prawer Jhabvala’s first ideas for two early novels.

In some circumstances, it is true to say that any essence of magic can be spoiled when all the minute details of a process are exposed. Somehow, the complete story of the homes and cupboards where these drafts were housed, the details of the origins of the packaging process, the handling by the individuals who encountered them and the attention with which they were treated at each point, partly evidenced from clues on the packages, added meaningfully to their extraordinary enchantment. This intertwined relationship between people and things is what explains the concept of objectification inherent in the work from Material Culture Studies (Woodson). This work focuses upon the properties which objects hold, the materials from which they are made and the ways in which these material components are central to an understanding of culture and social relations. Sociologists like Peter Pels speak of the agency and magical power of material things, this power which things themselves gain but only from the intervention of human intention. Things seem out of the ordinary or magical for us if they do something to us. Prawer Jhabvala’s fiction is full of everyday material objects like furniture, clothing and utensils in stories which could be read as symbols of cultural meaning but also as symbols of social hierarchy and class distinctions.

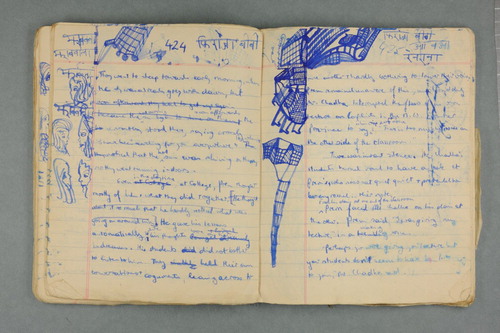

Figure 7. Photo of a handwritten page from a draft of the novel The Householder. Image © British Library Board.

It is important to be conscious of the temptation to fetishise these packages, adorned in colourful Indian stamps. After all, many of her other notebooks of works that were in the same shipment and were published later were stored in old plastic bags, some in re-used cardboard boxes or recycled folders, along with her typed later works, printed pre-publication drafts and manuscripts. These handwritten notebooks, however, with her quotes, her scribbled drawings, crossings-out and plans among the full drafts of published works have a special resonance which distinguishes them from the rest of the archival materials. Reading the contents of a notebook feels like another process of peeling back the layers; like being one step closer to the author’s thoughts about the characters and stories that later became her published works.

These particular notebooks, in entirety, held great value for Ruth Prawer Jhabvala as they comprised the origins of her first seven fictional published works, which were the building blocks of her creative career. One of them became an original screenplay, starting her transition into the world of film-making. It was important for her to have the notebooks around her and in safe keeping when she made the major decision to establish herself in the United States, from where she travelled annually to the family’s Delhi home.

She guarded them well when they weren’t crossing continents in her wake, and she bestowed them, with her other prose papers, to the country which gave her a home as a twelve-year-old refugee who arrived in 1939 with neither spoken nor written English. Jhab, the architect of many spaces in their lives and illustrator of many of her books, supported and enabled her endeavours. And her daughters have ensured that her final wishes have been carried out.

Her bequest shows that she considered her prose works her most important. Their psychological insights still resonate across transnational boundaries. The attention which Cyrus Jhabvala’s team in India gave to the packaging and transport on their first transnational journey was evident from the condition of the contents, despite the poor quality of the paper, multiple house moves and the lengthy time-lapse in between. The conservation team at the British Library also took attentive precautions to ensure their preservation for the future which will allow others to access them when they are catalogued. All of these efforts fully justified Prawer Jhabvala’s final decision for this last transnational journey of her legacy.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the AHRC for funding this Collaborative PhD project, my supervisors and our institutions for their support and guidance: Dr Florian Stadtler and Professor Laura Salisbury at the University of Exeter and Rachel Foss at the British Library. I would also like to thank The John Murray Archive, held at The National Library of Scotland, and the estate of Ruth and Cyrus Jhabvala for access to archives and permission for the use of these images. Special thanks go to Ruth Prawer Jhabvala’s daughters, Renana Jhabvala, Ava Jhabvala Wood and Firoza Jhabvala for their time, information and guidance with this article.

Works Cited

- BBC Genome. Radio Times 1923-2009. Accessed 5 Jul. 2019. <https://genome.ch.bbc.co.uk/search/0/20?adv=0&q=ruth+prawer+jhabvala&media=all&yf=1923&yt=2009&mf=1&mt=12&tf=00%3A00&tt=00%3A00#search>.

- British Library. Ruth Prawer Jhabvala: A Celebration. 3 July 2018. Accessed 5 Jul. 2019. <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tzwI0Ck6ReA&feature=youtu.be>.

- Genette, Gérard. Paratexts: Thresholds of Interpretation. 1997. Trans. Jane E Lewin. Ed. Richard Macksey and Michael Sprinker. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2001.

- John Murray Archive. Acc. 13328. Book files related to Ruth Prawer Jhabvala, National Library of Scotland, Edinburgh.

- Horowitz, Dorothy D. ‘Ruth Prawer Jhabvala: Oral History Memoir’. New York Library Digital Collections. The New York Public Library Nov. 1983. Accessed 5 Apr. 2019 <https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/ace61cc0-035b-0131-4229-58d385a7b928>.

- Jhabvala, Ruth Prawer. An Experience of India. London: John Murray, 1971.

- Jhabvala, Ruth Prawer. Heat and Dust. London: John Murray, 1975.

- Jhabvala, Ruth Prawer. The Householder. London: John Murray, 1960.

- Jhabvala, Ruth Prawer. Like Birds, Like Fishes. London: John Murray, 1963.

- Jhabvala, Ruth Prawer. My Nine Lives: Chapters of a Possible Past. London: John Murray, 2004.

- Jhabvala, Ruth Prawer. A Stronger Climate. London: John Murray, 1968.

- Jhabvala, Ruth Prawer. Uncatalogued papers. Deposit 10770 (2014). Contemporary Archives and Manuscripts. British Library, London.

- Knott, Kim. ‘Every Object Tells a Story’. Moving People Changing Places. UK Research into Diasporas, Migration and Identities, 2005–2010 <http://web.archive.org/web/20150215055840/http://www.diasporas.ac.uk/>.

- Levitt, Peggy. ‘Transnationalism’. Diasporas: Concepts, Intersections, Identities. Ed. Kim Knott and Sean McLoughlin. London: Zed Books, 2010. 40–42.

- Pels, Peter. ‘Studying Particular Things’. The Oxford Handbook of Material Culture Studies. Ed. Dan Hicks and Mary C Beaudry. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2010. 613.

- Woodson, Sophie. ‘Material Culture Studies’. Oxford Bibliography Online <http://www.oxfordbibliographies.com>. Last updated 2015.