Whenever I hear complaints that Arundhati Roy hasn’t written enough novels, I invoke the case of an Argentinean writer – Jorge Louis Borges – who wrote about half a novel, but is regarded as a towering figure not just in Spanish but in world letters. Arundhati Roy’s two full novels, written twenty years apart, are enough for us to call her great because of their piercing beauty, penetrating vision, wealth of detail, and their impeccable, almost musical, prose. She creates, amidst our homes and street corners, allegorical worlds as haunting as the history house and the Kabristan, and metaphors as raw as open wounds. She has described herself as a ‘mobile republic’ and her readers as borderless citizens; she planted the unusually ‘deft dorsal tufts of the cold moths’ on human hearts; she likened Hijra’s clap to ‘a gunshot’, defined the Indian mainstream Left as ‘a heady mix of Eastern Marxism and orthodox Hinduism, spiked with a shot of democracy’, and described, through the mouths of her characters, India as a ‘democracy zoo’, a ‘bazaar raj’, a collection of ‘ancient people’ trying to ‘live in a modern nation’, and renamed Bharat Matha’s chosen sons – the Gandhis, the Ambanis, the Adanis – as ‘history’s henchmen’.

Since a good deal of Roy’s numerous ‘non-fiction’ essays – collected in Broken Republic (2011), Seditious Heart (2019), Walking with the Comrades (2011) – are about the fictions of India, it is entirely possible to suggest that she has written more fiction than she is given credit for. If India – the heart of her imagination, or the object of her seditious heart – is a fictionally conceived nation without the consent of its people, then the entire body of her non-fiction is about the incredulity of its existence, the impossibility of its coming together, like the Jantar Mantar in The Ministry of Utmost Happiness (2017) where rebels, rogues, lovers, losers, Hijras, militants, Maoists, and Gandhians of all breeds and kinds converge, to find the broken thread of their imagined nation. But this is not a world of magical realism where dreams and lives become indistinguishable. This is India, not just any India, but the India of ‘saffron parakeets’ – a factory of dreams, a furnace of fake facts – a world of unmagical realism where the dreams of a fictive nation are not only processed, packaged, and actualised into militant realities, but are sold in the open market as historical facts, beamed across mobile gadgets, roadside adverts, walls of public urinals, and wherever there is a television set and a telephone tower.Footnote1

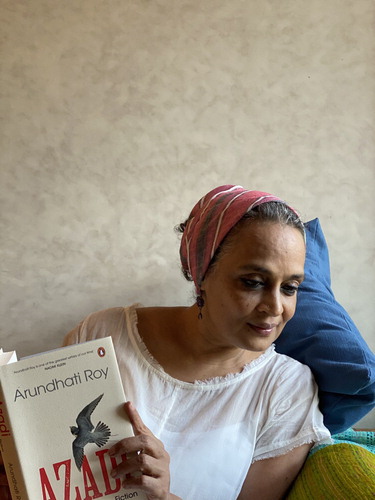

Arundhati, if I were to describe your life and work in your own lexicon, it would be that of a pickle jar of languages with the label ‘Malabar Coast Products’ — the real name of your Grandmother’s pickle factory. One can see big chunks of Urdu vegetables, slices of Bengali garlic, a toss of Telugu mango pieces, Malayali sea salt sprinkled all over the mix. The key ingredient is the chilli powder — the proverbial English which holds all the other ingredients together. The result is a potent dose of spiciness which is palatable neither to the English sahibs nor the Indian babus. Did I get the recipe (and the metaphor) right?

I think the problem with that metaphor is that pickles are settled things. Pickles peacefully live inside a bottle even if they have chilli powder or salt in them. But language, and especially language in India, is not a settled thing. It won’t submit to living peacefully in any bottle regardless of its size and shape. Language in India is almost as deeply contested as ethnicity, religion, caste, or sub-nationalism. In one of the essays in my book Azadi [2020] I describe the hundreds of languages and dialects in India that we live in and amongst, which makes us a people who are constantly translating ourselves to each other, however imperfectly, as an ocean of imperfection full of shoals of language fish and word fish that flash past. Some are carnivorous, some are hunted, some are predators, some are swallowed. But they are all nourished by what the ocean provides. And all of them, like the people in The Ministry, have no choice but to coexist, to survive, and to try to understand each other. There are a million kinds of colonialisms that go on in there. It is not just the English colonising everything else. Every language has a story and history behind it. So, I would say ‘pickle’ is the wrong metaphor for this particular vast, heaving, changing thing. I live and write in this teeming ecosystem of living, loving, warring creatures. Pickles are too settled. My writing is not. Nor is my life.

That’s a very satisfying, savoury answer. The occasion of our conversation is a discussion about justice. Do you think terms like ‘justice’ and ‘injustice’ are universal, with clear rules, like syntax, like algebra, or vernacularly distinct?

Obviously, they are vernacularly distinct, because if you enter a village, a caste-ridden village in India, what is considered ‘justice’? Who dispenses it? What do we understand by it? What I, as a privileged, urban woman in India expect and demand in the name of justice is not something that a woman in, say, a village in Haryana who is being arraigned by an upper-caste Khap panchayat can demand or even dream of.

I asked that question for two reasons: firstly, as you note in your Walking with the Comrades, the Adivasis could not count beyond twenty. One wonders what justice means to people who fall outside wage-labour capitalism, let alone translate the worth of their labour into numbers.

Yes that’s true in some of the deep forest villages at the heart of the conflict. But of course it’s not true of all Adivasis. The Adivasi communities in India are very diverse — as diverse as everybody else here. But yes, some of the tribes that live deep in the forest have less access to modern education. But they know other things, they have invaluable knowledge about things that modern education has destroyed in modern minds. How do you negotiate justice in a society, like the Indian, where people live in several centuries simultaneously? Everybody does not live in the market economy.

There is a saying that most of those who preach socialism are ‘macro-socialists but are micro-fascists’ in the sense that they support socialism as long as it doesn’t involve sharing their own resources or questioning their own privilege. I’ve read that the CPI [Communist Party of India] in Kerala has been somewhat hostile to you because you criticised them for failing to address the question of ‘untouchability’.

That has been the great failure of the Left in India — the inability to address the question of caste.

We are a society that lives in a hierarchical grid, which has not really been challenged. This grid is not imposed by the state, since theoretically the Constitution says all citizens are equal. The grid is imposed and actively sustained by various sections of society. Ambedkar made a Constitution that was more progressive than Indian society. It had the potential to challenge this. But now laws and ordinances are being passed that make nonsense of the Constitution. Recently in the state of Uttar Pradesh, the Ordinance Against Religious Conversion, known as the law against ‘Love Jihad’, targets interreligious marriages, especially between Muslims and Hindus. People are now liable to be arrested and imprisoned for five or ten years. It’s a criminal offence if you are seen to be converting somebody from one religion to another. Everybody is busy policing everybody else.

In The God of Small Things, when Velutha, the Dalit protagonist, is killed, your narrator reflects: ‘After all, they were not battling an epidemic. They were merely inoculating a community against an outbreak.’ Does the current pandemic offer, in any sense, a better or worse understanding of the relationship between purity, pollution, poverty, disease, and untouchability?

I think that caste and how it plays out, obviously in terms of dividing social space and distancing people from each other in real and metaphorical ways, is something people in India are used to and practised all the time, even in the most modern spaces and most modern forms. The idea of treating another human body as ‘polluting/infectious’ – a biohazardous body – is familiar to a society that practises caste and has the vulgar imagination to consider a fellow human being a polluting entity. It is the most violent form of social practice I think human beings could ever have come up with. And the coronavirus, in the way it has placed the idea of the biohazardous body at the centre of the public imagination, resonates so strongly with the idea of caste. I hear smug whispers about how Namaste is such a beautiful greeting because you don’t have to touch anybody …

You have argued that the pandemic could be used as an opportunity for corrective action, for new ways of thinking. I recall after 9/11 many commentators argued that it provided America an opportunity to reassess its relationship to the world. But it apparently didn’t.

I think I said that the pandemic is a portal and it’s up to us to choose what to drag through it, what we choose to take and what we choose to leave behind. The realism behind what is happening with Covid is that it looks as if the powers, the money, the digital world are going to use it as a way to make things even more unequal, more authoritarian, more controlled, more surveilled. You separate the conquered classes and castes, the torturable and the non-torturable, the imprisonable people and the chosen people, and so forth. It could be that Covid is giving the ruling class the opportunity to do away with the working class — mechanise, computerise, digitise. The world is haemorrhaging jobs. And the physical labour the economy cannot do without, they will find ways of sealing off as far as possible — the sacrificial class. But when I wrote about it when the pandemic first broke out, I actually was trying to say that there is another way of using this moment. That’s what I meant when I said that it’s a portal, because it is a rupture and an opportunity for us to think twice about a return to a ‘normality’ which was absolutely unbearable for so many people. To dream of something better than what we thought of as normality. To change and to reassess our luggage. But I fear what we are heading for is something worse, not better.

Can we turn to the title of your latest work? There are several kinds of ‘Azadis’ that run through my mind: Azadi (liberation) from a form of colonialism, and Azadi to a known place of freedom — utopic or dystopic. In The Ministry, you say that if you bring four Kashmiris together and ask what the meaning of ‘Azadi’ is, or its ideological bases, they would end up slitting each other’s throats. But you say this should not be mistaken as a state of confusion, and Kashmiris have this terrible clarity whenever they utter the word Azadi.

That particular thing about the dispute that Kashmiris have with each other about the exact meaning of Azadi, that is not me saying it. It’s one of the main characters in The Ministry, Biplab Dasgupta, aka Garson Hobart, who is a member of the Intelligence Bureau. The task of the Intelligence Bureau and the Indian intelligence agencies in Kashmir has been to sow these seeds of discord and division and set people against each other — so that is where that comment comes from. But despite their best efforts there is a terrible clarity among people in Kashmir because the nature of the oppression, the military occupation, has turned a whole population into insurgents — in mind, not deed. Right now, through fiat and ordinance, every bone in Kashmir’s metaphoric body is being broken. But still, after all this, miraculously, the spirit of that struggle doesn’t seem to be broken. Life goes on. Equally brutal, equally contentious — people are humiliated, some compromise, some fight back. I don’t remember who it was who said that eventually life is lived somewhere between the failed revolutions and the shabby deal. If it’s a spectrum, I’d rather be somewhere closer to the failed revolution than the shabby deal. There’s more honour in that, but one doesn’t always have a choice.

There is always this unrealistic expectation on the part of the readers to look up to writers and seek solutions for all kinds of social problems. How do you feel about that in relation to your own work? I think it is one of Chinua Achebe’s characters who, when asked by a journalist whether writers can offer prescriptions to social problems, says something like: ‘writers don’t offer prescriptions, they give headaches’.

When you look at literature or even political writing and you posit it in terms of problems and solutions, that in itself is such a simplification. I mean there may be solutions to the idea of building a big dam. There may be smaller dams or different kinds of water conservation that would be a better solution to irrigation and water supply. There may be solutions to a number of social, political, and economic conflicts. But is that the business of novels?

You remember the days of the World Social Forum when the slogan ‘Another world is possible’ became popular? In one of the central chapters of The Ministry, we find ourselves in a place called Jantar Mantar in Delhi — a place where resistance movements gather, people are on hunger strike, all kinds of things are going on. In the midst of all this a pair of documentary film-makers wander from group to group asking people to say in their own languages ‘Another world is possible’ for a montage in their film. When they ask Anjum – who is one of the main characters in the book – to say ‘Doosri duniya mumkin hai’, she replies, ‘Hum doosri Duniya se aaye hain’, meaning ‘I’ve come from the other world.’ Anjum is a Hijra, the Urdu for transgender. She has lived much of her life in Old Delhi in a haveli called the Khwabgah, the House of Dreams, with people like herself, a range of non-conforming genders, a whole other universe, who refer to the ‘normal’ world as the ‘Duniya’, the World. So they think of themselves as belonging to another world. She sees herself as coming from another world. The point I am trying to make is that it’s not just that other worlds are possible. Other worlds exist. They’re being suffocated, throttled. Novels can show you those other worlds, can show you different ways of fighting, living, loving, laughing, different things to laugh about. So, those worlds exist. And they connect to each other. To speak about novels – such grand and complex things – in terms of problems and solutions — is, in my mind, a little sad.

Speaking about freedoms and resistance movements, I am reminded of the anthropologist James Scott’s work, where he argues that the poor do have weapons – though not always guns – like foot dragging, sabotage, petty theft, feigning injury, and so forth. It always interested me to understand, in the daily grind of life, how people confront violence, cohabit with violence, and cope with injustices and carry on with their lives. I do not mean to suggest this to be a form of passive or negative agency, or even conference of dominance, but I see it as an embedded form of resistance in the social fabric that your work uncovers, especially in Kashmir. When she is caught up in the Gujarat massacre for instance, for Anjum, a straight man’s superstition becomes a Hijra’s boon, and then there is the whole fleet of Kashmiri militants who help Amrik Singh kill himself.

Anjum escapes the massacre of Muslims that she gets caught in, but the person she was with, Zakir Mian, is murdered. This is the 2002 massacre in Gujarat where almost 2,000 people, mostly Muslim, were butchered on the streets and tens of thousands were driven from their homes. Anjum escapes because the Hindu vigilante murderers believe that killing a Hijra is bad luck. She is caught up in the pogrom because of her Muslim identity, but her gender identity, which is often a reason for violence, on this occasion saves her. She returns to Delhi, but the trauma she has been through leaves her unable to go back to her life in the Khwabgah. She moves into a nearby Muslim graveyard where members of her family are buried. Over the years as she recovers, she builds a guest house called the Jannat Guest House. ‘Jannat’ in Urdu means ‘Paradise’. Each room has a grave. Instead of being a place for the dead, it becomes a place for the living with an osmotic, porous, boundary between the spirits of the living and the dead. When she is questioned by the municipal authorities she’s told that ‘no one is allowed to live in a graveyard’; she says ‘I am not living here, I’m dying here’. But basically, she is living there, and eventually creates her own community there — a community of passive insurgency. The people who live there, die there, and are buried there form the only possible networks of radical solidarity against Hindu Nationalism. That graveyard is the staging ground for revolution in India. A very Indian kind of revolution.

Dr Azad Bhartiya is another character I can’t forget who is part of this ‘very Indian kind of revolution’, or ‘the passive insurgency’ as you have called it.

Dr Azad Bhartiya is an embodiment of everyday resistance. Perhaps he is the very syntax of everyday resistance. He sits at Jantar Mantar – the place where protestors converge – he calls it the ‘Democracy Zoo’. He has been sitting there on an on-and-off hunger strike for years. He is a little eccentric, but actually through that eccentricity, his politics are profound — he has absorbed and now embodies everything that has swirled around him over the years. When I began to write the chapter called ‘The Nativity’, which introduces Dr Azad Bhartiya and all the other Jantar Mantar characters, I envisaged it as the gutter version of the opening scene of War and Peace where the good and the great of St Petersburg meet at Anna Pavlovna’s ball. In Jantar Mantar the battered and broken of modern India gather — gathered. It’s been more or less shut down now. But it is a place where I have spent many, many days and nights.

Azad Bhartiya is one of the more important characters in The Ministry. I remember when The Ministry was published in Germany I had an appointment with a journalist at a hotel. And this journalist – a very big man – was standing in the lobby with a huge bouquet of flowers. He made a sweeping bow and said: ‘Hello Arundhati, I am Dr Azad Bhartiya.’ And I laughed and said: ‘Oh, I thought I was Dr Azad Bhartiya!’

The repressive machinery of the state and the culture of impunity are some of the recurrent themes of your essays. So many Hindu vigilante murderers have gotten away even after public confessions of their crimes were recorded on tape and broadcast on TV. One could say that the violence that shapes Indian society is the vacuum created by such impunity, the vengeance that arises from the punishment that was not met.

Impunity has led to very dire things. Recently, I was at the farmers’ rally at the Delhi border, and one of the union leaders said: ‘You know, our leaders are murderers, mass murderers.’ I said: ‘Well, it is almost like when you apply for a job you have to show a degree. To be a leader here you have to show yourself capable of murdering or looking away while the right kind of people are murdered. You have to show that you are not unapologetic about it.’ In India you can lynch a Muslim, a Dalit, it can be on camera, you can put it up on YouTube and you can get massive support for it. And of course, look at Kashmir — a military occupation can only function if impunity is guaranteed. In Kashmir, they took away the oxygen a long time ago and now with every new law and ordinance they are close to breaking every last bone of that collective body. In India, they are taking away the oxygen of the poor as well as of the Muslim community. Almost every day, there are laws passed which are ghettoising them, marginalising them, threatening to take away citizenship. Every day is an assault on the Constitution, on the economy, on the environment, on education, health, the social fabric. And we have 400 TV news channels telling us that it isn’t happening. Churning out hatred and fake news all day and all night long.

There is a relationship between fact, fictions, and fascism. We live in an age of everyday emergencies where all news is breaking news, when real emergencies remain hidden from us. In an age of poking, following, liking, and 140-character tweeting, facts no longer seem to matter, but what one feels does. Feelings are the new facts.

Social media ushers people into hermetically sealed universes where they can feel comfortable and have their prejudices re-affirmed and reinforced. It applies to all of us, I guess. And now with the Covid pandemic people really are being physically sealed off from each other which accelerates this fevered process of fragmentation. All we can do is to continuously insist that there are such things as facts, there is such a thing as a reality check. Here we have a ruling party and its Hindu Nationalist ideology that has millions of people being sent fake facts and fake history which generate this rage and vengefulness that is becoming uncontrollable. This is the world we live in, and this is the world we have to try and navigate. It’s like swimming in a river full of flesh-eating fish. The only thing that can counter this also has to be done through social media. That battle is on right now. So you see the Hindu Nationalists, once the emperors of the Internet, now raging against Twitter and Facebook and Instagram, calling for bans. The Indian government tops the list of Internet shut downs — even as it forces the population into the digital world with its Unique IDs, Aadhar Cards, its disastrous demonetisation policy, and so on.

Not just India, these technologies are used in Burma, Bangladesh, and the Philippines to incite genocidal violence.

Last March in India, the corona panic and lockdown happened very soon after an organised pogrom, once again targeting Muslims, took place in Delhi during the protests against the new anti-Muslim citizenship laws. So anti-Muslim rhetoric merged seamlessly into the language of the pandemic and the lockdown. An organisation called the Tablighi Jamaat was holding an international meeting in a mosque in a neighbourhood called Nizamuddin which is quite close to where I live. The meeting had obviously been planned long ago and the lockdown was announced by the Prime Minister with just four hours’ notice. It meant that the people who had come from all over the world found themselves trapped in that pretty crowded neighbourhood. The TV channels began to headline what they called ‘Corona-Jihad’, accusing Muslims of being spreaders of disease. At a time of such tension, this de-humanising language was potentially genocidal. De-humanising a whole community, accusing them of spreading death. Muslims were being beaten on streets and boycotted. You create a deadly climate, then all you need to do is flick a match onto it. The preparation has been made, and is being kept on the boil continuously. All you need to do is to flick a match.

This so-called post-truth world is driven purely by the emotional logic of the moment. Fake news and fake facts are the lynchpins of affective technologies that hold sway, spread hatred, and engineer genocides. How do you imagine the role of the writer who writes both fiction and non-fiction, which, in John Berger’s words, are like two legs that take you around the world? There is this popular view that facts appeal to intellect and fiction to emotion. Facts are naked and raw, and fiction is dressed up, prepped up, and decked up.

This idea that fiction is the opposite of facts, and fiction dresses up facts — is of course puerile and not even worth getting into. To me fiction is not an argument, fiction is nothing less than an attempt to construct a complex universe. When you try to say, ‘Arundhati Roy said this’ and Arundhati Roy says, ‘I did not say that’, that may be a dispute of fact. But with fiction, for example, you take a situation like Kashmir where fiction could end up being a truer way of presenting the reality than facts could ever be. Because facts are hidden away, it may be hard to establish them or defend them legally even if you know them to be true. But there are truths that are more than just facts, more than what would qualify, say, as human rights violations, terrifying ways in which a whole population is trying to negotiate with institutionalised repression and violence, just in an attempt to survive. To try and create that universe in fiction — maybe the freedom fiction gives allows it to communicate what’s going on in a place like that more accurately, more comprehensively than a human rights report or a newspaper article. Eventually, the battle is going to be about contesting stories. What story do you believe? What stories do we believe? What kinds of feelings do we value? The fact-free world is now staring us in the face. How do you argue with people who say ‘Oh, actually, the people who invaded the US capitol were Antifa pretending to be the far right’? You can keep on falling lower and lower and the floor will keep giving way under your feet as you plummet into hell, or Wonderland, depending on your politics. People eventually go and believe what they want to believe. Or what is convenient for them to believe. This is a very dangerous thing in a very dangerous time.

These are not my views of course, and there are other popular views in this vein: if fact glosses reality, then fiction captures what is glossed over by the fact. My question here is this: do we have any aesthetic or ethical parameters that can distinguish between fictions that are dangerous and fictions that are necessary?

Well what is dangerous for you may be necessary for me. There never will be a consensus, will there? Whether it’s fiction, cinema, literature, poetry, music, all of this becomes a part of the texture of life, a part of our cellular structure. It’s not just reporting. It’s also imagining a world, and welcoming or rejecting what we think we would like to believe in. We use our skills to turn the tide, and those skills are powered by our ethics, our aesthetics, and our values. And these are set against other ethics, other aesthetics, other values — some that are different, some that are outright repugnant. The conflict will never end. Nor will the chaos.

I’d like to return to the idea of ‘algebra’ that inspired this conversation, the unifying code to which all elements return. I can’t help thinking of how you rewrite the alphabets of Kashmir as elements separating and coming together, awaiting their own syntax.

When I first started to travel in Kashmir, I was fascinated by how the years of violence had seeped into the vocabulary of ordinary Kashmiris. In The Ministry of Utmost Happiness, one of the characters, Tilottama, goes to Kashmir. She starts building what she calls the ‘Kashmiri-English Alphabet’:

A: Azadi/army/Allah/America/Attack/AK-47/Ammunition/Ambush/Aatankwadi/Armed Forces Special Powers Act/Area Domination/Al Badr/Al Mansoorian/Al Jehad/Afghan/Amarnath Yatra

W: Warnings/wireless/waza/wazwaan

X: X gratia

Y: Yatra (Amarnath)

Z: Zulm (oppression)/Z plus Security

This is like a confetti of Kashmir — an explosion of metaphors, from Azadi, to inqilab, from POWs [prisoners of war] and pundits. Kashmir, like India itself, to borrow the words of the late Northern-Irish poet Ciaran Carson, is ‘like a sentence one is trying to construct, which keeps stuttering — all the alleyways and side-streets blocked with stops and colons’ where ‘every move is punctuated’, leading us towards ‘a fusillade of question marks’.

These almost-English words will make their way into the Kashmiri vocabulary. Similarly, if you go to the Narmada valley in Central India where tens of thousands of people have been displaced by the Big Dams of the Narmada Valley Development Project, their vocabulary, even in local languages, include ‘Displacement’, ‘Project Affected Person’, and so on — it is a whole other vocabulary that comes into that space with words which you’d least expect people to know.

You have always held the view that India is a powerhouse of resistance movements. What are your views about the ongoing farmers’ resistance? This one seems stronger and more determined.

Last year this time, just before the pandemic hit, India was once again convulsed with protest. This was the protest against the new anti-Muslim citizenship laws and those protests were led by Muslims, especially by Muslim women. And they were spontaneous, they were massive, and they were militant. Those groups were not formally politically organised groups. They had come together in very, very interesting ways. You had young people joining them, you had all kinds of poetry and song, you had a lot of waving of national flags and the reading of the Constitution — which was in a way a form of protection because Muslims have been demonised as traitors, terrorists, Pakistan-sympathisers to such a great extent. The farmers’ protest is of a very different nature. For the first time this regime is facing a protest about its corporate economic agenda, which is beyond even crony capitalism. It has enriched two Gujarati-owned corporations, the Ambanis and Adanis, by billions of dollars.

A final question. Much has been said about the agency of your fictional characters. A glaring difference between your characters Velutha and Anjum is the way they shape their lives, the active agents of their fate and destiny. Velutha is a silent victim but Anjum builds a vibrant, vivacious community of resistance in Kabristan, without an iota of victimhood. Has the twenty-year gap in your fiction contributed to this shift in writing agency? Is it always important to position the marginalised as active agents of their making, as opposed to merely magnifying their victimhood — as in the case of Phulan Devi you have argued in the essay ‘The Great Indian Rape Trick’?

Velutha is not the only victim in The God of Small Things. And not really the silent one. The silent one is Estha, Esthappen, one of the twins. Who simply stops speaking altogether. But being silent is not the same as being voiceless. The God of Small Things is set in 1968, The Ministry is set in the 2000s, you’re talking about almost half a century where somebody who would have been a victim then may not be a victim now. I have often said, there is really no such thing as the voiceless, there are only the deliberately silenced or the preferably unheard. I think, particularly as a novelist, I find it so important that we have to understand that the world, our world, is peopled by all kinds. If they don’t find a place in your way of telling a story, then that story is incomplete. The Ministry of Utmost Happiness, or The God of Small Things, these are not novels that are only about marginalised people. They’re about the relationship of power that runs through the fabric of our society. I would not write a novel that is just about marginalised people or just about one single thing. To me, it’s the attempt to construct a universe. It was not just about one person or two people. The complexity of the world we live in has to be reflected in that.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Thanks to Frank Schulze-Engler, Stefanie Kemmerer, and Geoff Rodoreda for their help in drafting this interview.

Notes

1 This interview was conducted in early 2021.