ABSTRACT

Throughout scientific history, there have been cases of mainstream science dismissing novel ideas of less prominent researchers. Nowadays, many researchers with different social and academic backgrounds, origins and gender identities work together on topics of crucial importance. Still, it is questionable whether the privileged groups consider the views of underprivileged colleagues with sufficient attention. To profit from the diversity of thoughts, the scientific community first has to be open to minority viewpoints and epistemically include them in mainstream research. Moreover, the idea of inclusive science poses stronger requirements than the paradigm of open science. We argue that the concept of integration of different opinions is insufficient because the process of integration assumes adjusting oneself to the majority view and fitting into the dominant paradigm while contributing only with smaller amendments. Epistemic inclusion, on the other hand, means dynamically changing the research paradigm during the interaction with diverse methods and hypotheses. The process of inclusion preserves marginalized views and increases epistemic justice.

Introduction

The scientific workforce is becoming increasingly diverse, and many contemporary questions are best addressed in a collaborative endeavor by experts with diverse backgrounds. However, science is still often elitist and largely dominated by research institutions in Western Europe and North America, and by the scientists trained in a few institutions (Wapman et al. Citation2022). For example, more than 60% of the papers focusing on a country or region in the Global South do not include any researchers based there (Amarante et al. Citation2022). This underrepresentation has serious consequences: Naidoo et al. (Citation2021) evaluated that less than 4% of the papers related to COVID-19 are relevant to Africa. Consequently, researchers in the Global South are calling for fairness, equity and diversity in research collaborations (Horn et al. Citation2022), and universities and funding agencies are increasingly promoting diversity. However, also within the dominant institutions, we witness a lack of diversity, which is the consequence of elitism. Because of policy decisions, many institutions are nowadays more willing to hire researchers with a more diverse background, increasing the cognitive diversity of the community. However, these hires are frequently not included in the discourse and their viewpoints are not considered equally valid. In other words, they are allowed at the table, but must behave as the majority expects.

Cognitive diversity by itself does not help unless the underrepresented viewpoint is included. As Asai (Citation2019) importantly noted: ‘Diversity without inclusion is an empty gesture’. Epistemic inclusion is the process of incorporating the diverse opinions of peers. It goes one step further than integration which requires all individuals to fit into the dominant paradigm. In an inclusive interaction, minorities do not abandon their perspectives, but the majority and the underprivileged groups dynamically alter their perspectives after receiving new information. Thus, epistemic inclusion is not simply an additive process, it is rather a dynamic process that allows for the group knowledge to be greater than the simple sum of the individual stances. Epistemic inclusion is a key component for maximizing the benefit of cognitive diversity. In an inclusive environment, a plurality of scientific hypotheses is assessed, allowing further theories to be developed based on them. Epistemic exclusion, as the opposite process, neglects the opinions of vulnerable groups in favor of the dominant paradigm.

Different types of epistemic injustice can cause exclusion. An example of epistemic exclusion in a scientific community that came with a high cost is the delayed acceptance of human papillomavirus (HPV) as the main cause of cervical cancer. Cornwall (Citation2014) reports that when Harald zur Hausen’s group first presented their results linking cervical cancer to HPV, their findings were dismissed partially because of their imperfect English skills. This was a typical case of linguistic epistemic injustice (Vučković and Sikimić Citation2022). Moreover, the results were going against the mainstream hypothesis claiming that cancers are not related to infectious diseases. However, zur Hausen was later awarded a Nobel Prize and today the HPV vaccination as preventive measure for cervical cancer, which kills every year more than a quarter of a million people (Parkin and Bray Citation2006), is widely implemented.

Already Thomas Kuhn noted that during periods of normal science, i.e. periods in which researchers work under a dominant paradigm, scientists follow established research paths, while textbooks promote the dominant views (Kuhn Citation1970, Citation1977, Citation2011). Moreover, Kuhn (Citation1977) emphasized the importance of rational disagreement among scientists when choosing the optimal theory. To benefit from the heterogeneity of scientific viewpoints, stronger requirements are needed than the ones that the current paradigm of open science poses. For example, Leonelli (Citation2022) stresses the importance of equity and inclusivity in science. The heterogeneity of scientific results and approaches requires researchers who are epistemically tolerant towards competing theories (Sikimić et al. Citation2021) and ready to include them in mainstream science.

Inclusion is not only important within the scientific workforce, but it is also essential for the interaction with the general public and in particular the populations affected by the research in question. For example, Lewis and Sadler (Citation2021) reported on community-academic partnerships during the Flint water crisis. Those partnerships revealed high asthma levels at certain locations and the researchers directed mobile health units towards these locations. However, such partnerships require a long-standing commitment to a community, longer than typical funding cycles and alternative matrices of success which cannot necessarily be measured in publications (Lewis and Sadler Citation2021). In contrast, the current academic culture results in a translational gap, for example, between the high-profile research of tropical diseases and the roll-out of treatments (O’Connell Citation2007).

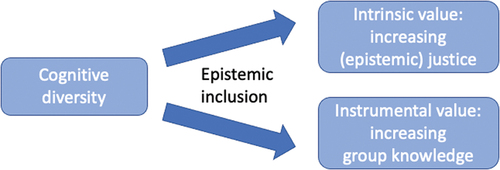

To motivate the importance of cognitive diversity and inclusion, we will present arguments in favor of it, both on a group level and on the level of the scientific community. Afterwards, we will discuss different types of aggregation of diverse knowledge and argue that epistemic inclusion is optimal if our goal is to maximally profit from diversity. Epistemic inclusion can have the instrumental value of being epistemically beneficial from the group perspective, but it can also be postulated as an intrinsic value because it reduces inequality and injustice. Finally, we will discuss measures that can promote an inclusive environment in science.

The Role of Cognitive Diversity in Science

Cognitive diversity can facilitate a diversity of hypotheses, because different backgrounds and viewpoints promote the use of different approaches. However, there can be a mismatch between the hypothesis a researcher should pursue from the social perspective and the individual perspective. From the pragmatic perspective, for one’s individual career, a good strategy could be exploring the most likely hypotheses, as this offers the greatest opportunity for publication of one’s results, even considering that it may be necessary to publish them in low-impact journals. This motivation reduces the diversity of approaches published. On the other hand, from the perspective of the scientific community, some researchers should still pursue hypotheses that are riskier. The importance of diversity of hypotheses has been stressed by philosophers using examples from history of science, probabilistic models and computer simulations (e.g. Kitcher Citation1990, Citation1993; Strevens Citation2003). All these findings suggest that new and less probable ideas can lead to highly influential research (Kitcher Citation1990, Citation1993). Thus, epistemic diversity can be beneficial for forming correct beliefs.

The diversity of the international funding landscape promotes the division into incremental and high-risk high-reward research. While most grants support incremental research based on past performance, some funding agencies such as the European Research Council, award funding particularly to high-risk projects (European Research Council Citation2020). They aim to fund research with a high conceptual risk, for which a feasible research proposal can be presented and some preliminary results exist. Though these projects have a higher risk of failure, in case of success they often become influential, which justifies their promotion. Some researchers enthusiastically pursue diverse ideas because of their personal convictions and the prestigious associated with solving long-standing questions with novel approaches.

If cognitive diversity helps in scientific discoveries, we can also think about it as an epistemic virtue of the scientific community. To test this hypothesis, a variety of computer models have been used. They generally start with a group of scientists who reach a consensus through communication. The results of Zollman’s formal models (Zollman Citation2010) emphasize the importance of transient diversity for the scientific community. Transient diversity occurs when scientists in the beginning of a discovery process investigate different hypotheses and reach a consensus after this initial period. This happens in situations when scientists have strong personal convictions or when their communication is limited (Zollman Citation2010). This finding is also known as the Zollman effect (Rosenstock, Bruner, and O’Connor Citation2017). Such a strong personal conviction could also be understood as the result of social diversity – individuals do not abandon their beliefs and approaches which have been formed within decades easily. Different biases, such as the sunk-cost-bias, can motivate researchers to keep investigating their hypotheses even when they do not align with the majority views (Holman and Bruner Citation2015).

Cognitive Diversity within a Research Team

From the perspective of an individual research team, Grim et al. (Citation2019) showed that the benefit of cognitive diversity depends on the complexity of the research question that scientists are trying to solve. Diversity is advantageous for solving certain problems, but for others, the abilities of individual team members have a greater impact (Grim et al. Citation2019). It was also observed in industry that diverse groups tend to perform better than more uniform ones (Hunt et al. Citation2018; Powell Citation2018). In academia, they publish more papers, and their papers are more frequently cited (Powell Citation2018). In industry, more diverse management correlates with a financial advantage (Hunt et al. Citation2018). Grim (Citation2009) emphasized the benefits of limited communication among scientists for certain research questions. These observations challenge the common view that scientific exchanges among researchers who support competing theories are epistemically advantageous (Longino Citation2002). Cognitive diversity can be achieved by strong initial beliefs or biases in well-connected networks. Therefore, the models from Grim (Citation2009) and Rosenstock, Bruner and O’Connor (Citation2017) do not argue against scientific exchanges between researchers with opposing views, but against immediately following the mainstream opinions. In particular, it can be shown how groups are most effective when they first explore many different hypotheses and only later present their conclusion once they have gained sufficient support (Sikimić and Herud-Sikimić Citation2022).

Psychological experiments support the idea that the more complex questions require a more diverse approach. When studying the communication patterns in teams, Brown and Miller (Citation2000) found that groups that tackle complex tasks tend to adopt more decentralized networks which allow for cognitive diversity.

Diversity also comes with its challenges. A high degree of independence for the individual researchers as well as large team sizes are beneficial for the success of multidisciplinary teams (Jackson Citation1996). Weaker links between the scientists enable them to develop their ideas and question the dominant paradigms. However, large, weakly connected groups frequently lack a common goal and suffer from insufficient communication, making them hard to manage. Thus, the optimal degree of diversity is a compromise between a high diversity of ideas and a strong cohesion of the group resulting in a good understanding between the individuals.

In addition to these social and psychological challenges, the investigation of non-mainstream hypotheses is also limited by the evaluation and funding system. Scientific journals follow the same trends as the research community and prefer to publish research from the largest and, therefore, most cited subfields (Calver Citation2015; Ha, Tan, and Soo Citation2006). In contrast, innovative methods or theories as well as different interpretations of previous data sometimes struggle to get published (Campanario Citation1993). This incentive can reduce the variety of approaches as it motivates scientists to direct their efforts in a more uniform and safer research.

Benefits of Cognitive Diversity in Science

The argument that cognitive diversity can help in the crowdsourcing of information or bring up unconventional ideas in science motivates us to prescribe an instrumental value to cognitive diversity. This instrumental value stands for increasing the epistemic benefit of a scientific community through fostering diverse perspectives and approaches in science.

Apart from instrumental values that cognitive diversity can have, there are also reasons for assigning an intrinsic value to diversity in science. Cognitive diversity is intertwined with social diversity, since, e.g. people with different backgrounds are likelier to have different experiences and ideas. Postulating diversity as a value by itself comes from the theories of democracy and education, where the opinion of each individual matters and has equal weight. Diversity can be achieved by affirmative action, e.g. giving more positions to female researchers in STEM (Sikimić, Damnjanović and Perović Citation2023). The idea behind affirmative action is that underrepresented groups are given a certain advantage with the hope that in the future the balance between groups will be restored. The issue with affirmative measures is that members of the dominant group might feel discriminated against by them, while the justification for affirmative actions lies in the fact that the members of a certain group suffered discrimination over long periods. However, the mere presence of researchers with a more diverse background does not necessarily result in their inclusion.

To mitigate the problem of social and epistemic discrimination and preserve the diversity of thought, education can play a key role. For instance, the academic culture that rewards the intellectual curiosity of graduate students creates a stimulating ground for profiting from cognitive diversity. Similarly, emphasizing epistemic openness as a virtue and, thus, setting a positive example for early-career researchers will have beneficial long-term effects.

Types of Knowledge Aggregation

It is considered that too much cognitive diversity might have a negative effect on the accuracy of the predictions. Thus, diversity is only giving positive results under certain conditions. For instance, according to the wisdom of crowds theory, the accuracy of group knowledge is increased with its size, the agents need to have relevant private information and be able to build further knowledge based on this information (Surowiecki Citation2005). However, this special kind of knowledge aggregation has several requirements, first more than 50% of the participants need to be right, second, they have to cast their votes independently of the opinions of the others, which is not overly common in a scientific discourse. Weatherall and O’Connor (Citation2021) developed a formal model in which the agents tend to agree with their neighbors if they have no prior knowledge. This confirmatory behavior negatively affects the community and can lead to polarization. This observation highlights that in real world scenarios, the type of knowledge aggregation and the valuation of the opinions of the peers is very important when it comes to the performance of the group.

Different Ways of Aggregating Diverse Knowledge in Science

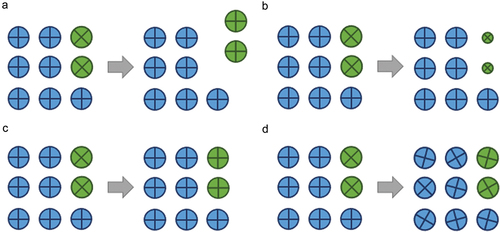

Epistemic exclusion means ostracism of the researchers who do not follow the dominant tendencies (). In extreme situations, such as the dogmatic rule of religious understanding of astronomy, researchers like Giordano Bruno were even paying with their lives for going against the mainstream theories (Rowland Citation2009).

Figure 1. Different types of knowledge aggregation. (a) Epistemic exclusion. Minority groups are excluded from the discourse. (b) Epistemic dominance. Individuals who do not fit in the profile of the dominant viewpoint are diminished. (c) Epistemic integration/assimilation. Researchers from minorities adopt the approach of their peers. (d) Epistemic inclusion. All members of the group dynamically alter their behaviors.

Epistemic dominance, as a milder tendency than exclusion, stands for following the dominant paradigm without questioning it (). For example, hierarchical research groups are susceptible to epistemic dominance. In situations where epistemic dominance is the governing principle of knowledge aggregation, the researchers will follow the dominant paradigm and relatively easily dismiss results that go against it, as in the example with novel findings of zur Hausen’s team. It is worth noting that following the dominant paradigm can also be rational and maximize individual epistemic chances (cf. Sikimić et al. Citation2021). Still, in these situations, there is limited profit from cognitive diversity.

When we consider authoritarian research teams, a person who comes from a different background might not be able to fit the requirements of the authoritative group leader. These structures usually are based on the idea that the leader can understand all details of a project and direct it accordingly, a prerequisite that becomes increasingly hard to fulfill the more diverse the team becomes. Interestingly, authoritarian research groups might perform better when they are homogeneous because they will have higher cohesion and efficiency than a diverse team. Guiding a research team with more diverse expertise requires a certain level of epistemic trust in all the members and the freedom to explore ideas that are not necessarily intuitive for everyone.

In communities consisting of people with diverse views and backgrounds, one can try to integrate the minority into the majority approach. The main component of integration or assimilation as a principle of knowledge aggregation is the hypothesis that the minority group has to adapt to the majority view. In this way, part of their diversity is lost (). For instance, hiring more female researchers in a STEM field such as physics to promote gender balance, but still having the same academic culture which is perceived as predominantly masculine (Gonsalves, Danielsson, and Pettersson Citation2016), is an example of an integration process.

Finally, we come to inclusion as a knowledge aggregation method. In some simple scenarios, like in the example of estimating the weight of an animal, the effect of the wisdom of crowds is achieved by calculating the arithmetic middle of all the predictions. This egalitarian procedure can be classified as inclusive because equal weight is assigned to everyone’s opinion, and no one was epistemically harmed in the procedure. However, in more complex scenarios, where some agents belong to underprivileged groups, one needs to consider affirmative measures to achieve proper inclusion. Epistemic inclusion means adapting the dominant view in the interaction with the diverse approach (). In the case of gender balance, inclusion means changing the academic culture to an environment open to all gender identities. In particular, epistemically including the opinions of people with different gender identities and valuing their experience.

Epistemic Inclusion and Justice

Inclusion is often discussed in political theory with respect to the democratic idea of equity (cf. Young Citation2002). For instance, Jürgen Habermas (Citation1998) emphasized the importance of inclusion for deliberative democracy. He argued for the right of the citizens to insist on the inclusion of immigrants into the political system while keeping their own culture. In particular, he argued against compulsory assimilation. On the other hand, appropriate equality is achievable through inclusive processes.

In medical communities, deliberative practices typically refer to structured processes of communication and decision-making among healthcare professionals, patients and other stakeholders. These practices aim to foster open and respectful dialogue, enhance shared decision-making and improve the overall quality of healthcare delivery. Deliberation involves careful consideration of various perspectives, evidence, values and ethical considerations before reaching a decision. Solomon (Citation2015) explored how medical communities engage with different sources of knowledge and navigate complex ethical and social issues. She argues for evaluating the different strengths and weaknesses of each individual method, instead of developing a hierarchy of methods. In order to epistemically profit from deliberation, one needs to be epistemically inclusive. If the members of the deliberating group are not open to the opinions of others, deliberations can also lead to polarization, i.e. a state in which the initial division is reinforced and increased (e.g. Schkade, Sunstein, and Hastie Citation2007; Sunstein Citation2007). Polarization is the state of a community in which two or more groups support opposing theories and considered only their own viewpoint as valid.

Inclusion has also been thoroughly studied in the context of education (e.g. Emanuelsson Citation1998). An inclusive environment treats every person as an individual with specific needs and it changes dynamically to accommodate its members. Inclusion goes one step further than integration, which simply tries to fit the minority into existing group patterns (Vislie Citation2003). Epistemic integration requires less from the proponents of the dominant views. For instance, according to the requirements of integration, in a laboratory where researchers with diverse viewpoints are introduced, they would have to adapt their approaches and techniques to be in line with the prevailing ones in order for their opinion to be taken with equal consideration. On the other hand, in an epistemically inclusive laboratory, the other researchers dynamically respond to the different experiences and approaches of the new team members and try to include them in their daily research routines.

The absence of cognitive diversity and epistemic inclusion can lead to information cascades, epistemic bubbles or echo chambers. In these structures, knowledge is lost or actively diminished due to a lack of exposure to opposing viewpoints. In information cascades, all members follow what they perceive as an epistemic authority without questioning it (e.g. Baltag et al. Citation2013). One example of a harmful information cascade was the discussion about the mode of transmission of SARS-CoV-2. Based on the paradigm that airborne transmissions are negligible, the WHO and other authorities proclaimed that it would spread over droplets, not aerosols. This information cascade had serious consequences on human health at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic (Jimenez et al. Citation2022). In epistemic bubbles, researchers are not exposed to other ideas because they do not exchange ideas with people outside their bubble (Nguyen Citation2018). Such bubbles can, for example, be the result of isolation or language barriers. If this lack of interaction with people outside of one's bubble is combined with reinforcing communication within the bubble, it can become an echo chambers (Nguyen Citation2018). In those structures, members of the group reinforce the beliefs of each other. This can result in the perpetuation of dangerous practices. In echo chamber relevant voices are actively excluded. In the history of science, many minorities, women, people of color, etc., were explicitly and implicitly excluded from education and science.

The elitist nature of science can particularly prompt epistemic exclusion. For example, 80% of the faculty at US universities is trained at just 20% of the institutions (Wapman et al. Citation2022). An elitist scientific system lacks diversity of knowledge and methods, and epistemic bubbles might be formed. In an elitist scientific system, people who are perceived as epistemic outsiders are expected to integrate in it. The process of integration will cost them their authentic epistemic expertise as they are required to adapt their viewpoint to the dominant paradigm to be considered equal. This can lead to testimonial smothering. Testimonial smothering occurs when an agent is not sharing their epistemic insights because they do not expect that these will be fully accepted and appreciated (Dotson Citation2011). In other words, they do not expect that their views will be included thus they abstain from giving them.

The lack of inclusion in addition puts an unjust expectation on the few members of minority groups. In this context, Berenstain (Citation2016) discusses epistemic exploitation as one of the problems minority researchers face: they are often expected to educate their peers about discrimination and to participate in committees to increase their diversity. Typical examples are hiring committees at STEM faculties. Women are often asked to participate in those committees, however, their small proportion in the faculty means that they have to spend disproportionally more time in those meetings. This is particularly problematic if their opinions are not valued and included, e.g. the majority just overvotes them. This tokenization of positionalities should be discussed from the perspective of standpoint epistemology. Standpoint epistemology, also known as feminist standpoint theory, is a philosophical framework that emphasizes the importance of considering the perspectives and experiences of underprivileged groups. This theory suggests that one’s social position or standpoint significantly influences how they perceive and understand the world. Toole (Citation2019) discussed how our position in society influences our views and conceptual resources and can lead to a form of epistemic oppression of lower ranking members of society. Moreover, while the dominant group can exclude the knowledge of the marginalized, the underprivileged scientists are usually well aware of the majority position. Thus, they can potentially form a more accurate and comprehensive understanding of the phenomena. A formal model of network standpoint epistemology by Wu (Citation2023) highlights this epistemic effect.

Epistemic virtues such as open-mindedness, epistemic humility and epistemic tolerance, and epistemic vices, such as closed-mindedness and epistemic authoritarianism, are relevant for epistemic inclusion as they can either facilitate it or prevent it. In particular, epistemic tolerance is one of the key epistemic virtues when it comes to rational disagreement among scientists (e.g. de Donato Rodríguez and Zamora Bonilla Citation2014). Moreover, Sikimić et al. (Citation2021) introduced a scale for empirically measuring both epistemic tolerance and epistemic authoritarianism of scientists, by testing their attitudes towards competing theories and dominant paradigms. The results were encouraging, since scientists on average scored high on the epistemic tolerance scale and low on the epistemic authoritarianism scale. Fostering epistemic justice as an intellectual virtue is essential for creating an inclusive environment in science. Moreover, an epistemically inclusive environment facilitates intellectual justice.

The Intrinsic Value of Epistemic Inclusion

Epistemic inclusion is the optimal way of aggregating diverse knowledge because it maximizes the positive impacts that cognitive diversity might have on science. Analogously to cognitive diversity, epistemic inclusion can be postulated as having instrumental and intrinsic value. Epistemic inclusion both has instrumental value as it contributes to the group knowledge and intrinsic value of fostering epistemic justice (). This can be achieved by stimulating an inclusive culture, both on the level of the discipline and on the team level. On the level of a discipline, review processes that are benevolent can contribute to epistemic inclusion. On the level of a research team, an inclusive environment promotes hiring and exchanging ideas with scientists with different perspectives on the research problem at hand. The intrinsic value of epistemic inclusion is to mitigate epistemic injustice by assigning epistemic value to the views of underprivileged groups in science. This in turn, positively reflects on the general justice in science.

Figure 2. Epistemic inclusion facilitates reaching the intrinsic and instrumental potential of cognitive diversity.

An important aspect of fighting epistemic injustice in science is the question of the inclusion of underprivileged groups such as female and foreign researchers. Though a lot of effort is placed into increasing the gender balance in science, a study from 2007 reports less than 15% of the full professors in Europe are female (Ledin et al. Citation2007). The small number of female professors is not representative of the proportion of female students but is a consequence of these students leaving academia. To keep them within the scientific community, they should experience that their views are valued. However, it is questionable whether the epistemic views of female researchers are currently given the same weight as the views of their male colleagues. Such unequal treatment represents an epistemic injustice that can prevent inclusion. Testimonial injustice is a type of epistemic injustice that occurs when someone disregards another person’s testimony because they are a member of a minority group (Fricker Citation2007). For example, in science, testimonial injustice occurs if hypotheses, findings or methods used by researchers from the Global South are given less weight than those from the Global North. The mainstream understanding of testimonial injustice is that less credibility is given to a testimony of a person because of the prejudices against them or the group to which they belong. It is also possible that this person fails when making a hypothesis or believes a falsehood. Still, the prejudiced audience attributes less credibility to this person than they would to someone with a different background (McGlynn Citationforthcoming). Following Luzzi (Citation2016), McGlynn (Citationforthcoming) also discusses the possibility that someone is considered to be a credible source, but the audience does not consider the justification that this person offers adequate. In science this can happen when the methods used for supporting an empirical claim are novel or non-standard. In this case the testimonial injustice will be triggered by the imputed ignorance, i.e. the assumption that the person could not reach the conclusions using the proposed justification mechanisms. It remains an open debate whether in such cases the knower receives less credibility or not.

One instance of testimonial injustice in science is linguistic testimonial injustice such as the previously mentioned discrimination against zur Hausen’s findings because of the English proficiency of his team (Vučković and Sikimić 2023). As a result of epistemic injustice, the knowledge of the marginalized agents gets lost. Finally, Anderson (Citation2012) argued that debiasing needs to happen both on the individual and institutional levels by creating an environment that incorporates the views of marginalized groups.

Epistemic inclusion is the proper way of mitigating epistemic injustice because it requires the members of the privileged group not only to consider other opinions but to dynamically adjust their stance as a result of their exchange with underprivileged groups. It is important to note that the underprivileged group can be numerically larger, e.g. Ph.D. students, however, the voice of the underprivileged groups is not equally valued. An inclusive environment asserts a new paradigm of a multidirectional learning process, in which professors are learning from their students or researchers learn from the communities they study. This requires a change of the academic culture from an elitist to an inclusive paradigm.

Measures for Fostering Epistemic Inclusion in Science

In the previous chapters, the differences between integration and inclusion were highlighted. Moreover, we discussed the epistemic advantages of the inclusion of epistemically diverse researchers in the scientific workforce. If diverse researchers are included, they can contribute and advance science, this benefit requires proper knowledge aggregation and changes from the majority.

To achieve epistemic inclusion, the academic culture has to change. Inclusion in science has to be lived at every university, department and research group. To promote this development bottom-up initiatives in the individual teams and top-down approaches on the level of funding agencies can be very successful. Academic freedom includes the freedom of individuals to manage their research in the way they see fit. The academic freedom of epistemically excluded researchers is endangered because they do not have equal opportunities. Moreover, epistemic dominance limits the academic freedom of researchers with diverse viewpoints. To promote inclusion on the individual level, it is important to highlight its benefits and give guidelines on how to achieve it. Furthermore, funding agencies have the flexibility and influence to promote the inclusion of diverse researchers into the community and thereby promote epistemic justice. In this section, we will outline some of the opportunities for funding agencies to promote epistemic inclusion.

To address any challenge, the extent of the problem first has to be understood. Therefore, funders should ask for a statement on the diversity of the research group of the applicants or the background of the individual researcher. For faculty job applications at universities, diversity statements are already frequently required. In this way, the awareness of the researchers is raised, and the funding bodies also gain valuable insights into the diversity of their grantees. For example, Cancer Research UK, the largest independent cancer research charity, is committed to increasing the percentage of applicants and grant holders from diverse backgrounds and publishing data on the diversity of successful and unsuccessful applicants (Cancer Research UK Citation2021). Their data show an equal success rate for male and female applicants but a smaller success rate for ethnic minorities for fellowship applications (Cancer Research UK Citation2021).

Another frequently addressed issue is the underrepresentation of females in evaluation committees. With the idea to address the gender imbalance in science, several funding agencies worked on increasing the proportion of females in their review panels. However, research shows that applicants being evaluated by at least one-panel member from the same institution have a higher chance of success (van den Besselaar and Mom Citation2021). This indicates that only increasing the proportion of women in the panel might improve the situation for female applicants; however, it falls short of providing a fair review because gender is only one aspect that unfairly influences the evaluation.

A further option to increase the diversity in the academic workforce and increase the visibility of underprivileged groups is providing targeted grants. Funding agencies nowadays recognize their influence and responsibility for a more diverse scientific community. For example, Wellcome, one of the wealthiest charitable foundations in the world, acknowledged in 2020 that they perpetuated racism (Wellcome Citation2020). Today, research grants targeting female researchers are commonplace for many funding agencies. In addition, some funding agencies promote underrepresented groups on the management level. For example, the German Research Foundation awards additional funding for networks with spokespersons or coordinators from an underrepresented gender (DFG Citation2020). This policy goes one step further than just requiring a specific quota of female principal investigators (integration), because spokespersons and coordinators have a larger impact on the research direction. This increases their chance to influence the decision making and alter the research direction of the network (inclusion).

The peer review system both limits and perpetuates elitism. On the one hand, journal editors and reviewers are usually well-established scientists and studies not supporting the main hypothesis might be dismissed by them. On the other hand, many journals nowadays use double blind peer-review to reduce the impact of unconscious biases (Darling Citation2015). Lee (Citation2015) explored how factors like gender, institutional prestige and implicit biases can influence the evaluation of research submissions. Furthermore, Heesen and Bright (Citation2021) question the benefits of peer review, considering the high epistemic cost in terms of time spent on reviews and revisions. However, peer review also allows non-famous scientists to be considered and reach a broad audience and was introduced to draw on the knowledge of recognized authorities in contrast to resting the decision only on the editors. Without the selection by editors and reviewers, their contributions might be overlooked on preprint servers due to the prestigious bias. For example, Añazco et al. (Citation2021) found that 62% of the more than 5000 COVID-19 related preprints analyzed had no citations while the same was true for only 33% of the preprints which were eventually published.

A part of the resistance against diverse ideas comes from the current scientific system itself. Grant peer review intrinsically requires convincing a committee – a prerequisite much harder to be fulfilled if one’s idea is against the mainstream. Limited contracts further discourage the exploration of risky projects. When the prolongation of one’s contract depends on a positive outcome, researchers are motivated to stay on established paths. By contrast, some research institutions, such as the Max Planck Society – one of the leading European networks of institutes, guarantee their directors generous funding till they retire, allowing them to pursue risky ideas (Kupferschmidt Citation2018). However, directorships are usually not awarded in an early-career stage.

As a last general aspect, short funding cycles prevent the establishment of novel but time-consuming projects. Projects that need the establishment of trust of a disadvantaged community frequently require a long-term commitment. For instance, Lewis and Sadler (Citation2021) argue that partnerships with marginalized groups require more time than normal funding cycles allow.

Apart from the grant awarding system, it is important to follow the progress of the approved research project to make sure that the team members are treated appropriately. As measures for increasing inclusion in science, funding agencies could support counseling services, introduce training programs for group leaders, mentoring activities for underrepresented groups, organization of workshops for all team members, etc.

Conclusions

Cognitive diversity in science has both benefits, e.g. it can help in solving difficult research questions, and limitations, such as decreasing team cohesion. In order to epistemically profit from cognitive diversity in science, it is important to properly aggregate diverse group knowledge. Different types of knowledge aggregation such as epistemic dominance, integration into the dominant paradigm and epistemic exclusion fail to capture all the potentials of cognitive diversity. Epistemic inclusion, on the other hand, promotes both intrinsic and instrumental values associated with cognitive diversity. In an inclusive setting, the academic culture changes to accommodate diverse views facilitating both the information flow and epistemic justice. Promoting epistemic virtues through the education of early-career researchers together with the financial stimulation of diverse research will contribute to cultivating an epistemically inclusive culture in science.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Vlasta Sikimić

Vlasta Sikimić is an Assistant Professor of Philosophy of Science at the Eindhoven University of Technology. In her research, Dr. Sikimić promotes the ideal of inclusive science. She lectures on topics such as Philosophy and Epistemology of Science, Social Epistemology, and Information Dynamics in Groups. Dr. Sikimić also actively takes part in philosophical organizations of international importance. For example, she is the Chair of the Organizing Committee of the European Philosophy of Science Conference that will be held in 2023 and a member of the East European Network for Philosophy of Science Steering Committee.

References

- Amarante, Verónica, Ronelle Burger, Grieve Chelwa, John Cockburn, Ana Kassouf, Andrew McKay, and Julieta Zurbrigg. 2022. “Underrepresentation of Developing Country Researchers in Development Research.” Applied Economics Letters 29 (17): 1659–1664. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504851.2021.1965528.

- Añazco, D., B. Nicolalde, I. Espinosa, J. Camacho, M. Mushtaq, J. Gimenez, and E. Teran. 2021. “Publication Rate and Citation Counts for Preprints Released During the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Good, the Bad and the Ugly.” PeerJ 9:e10927. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.10927.

- Anderson, Elizabeth. 2012. “Epistemic Justice as a Virtue of Social Institutions.” Social Epistemology 26 (2): 163–173. https://doi.org/10.1080/02691728.2011.652211.

- Asai, David. 2019. “To Learn Inclusion Skills, Make It Personal.” Nature 565 (7737): 537–538. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-019-00282-y.

- Baltag, Alexandru, Zoé Christoff, Jens Ulrik Hansen, and Sonja Smets. 2013. “Logical Models of Informational Cascades.” In Logic Across the University: Foundations and Applications: proceedings of the Tsinghua Logic Conference [Studies in Logic], edited by J. van Benthem and F. Liu, Vol. 47, 405–432. Beijing: College Publications.

- Berenstain, Nora. 2016. “Epistemic Exploitation.” Ergo, an Open Access Journal of Philosophy 3 (20201214). https://doi.org/10.3998/ergo.12405314.0003.022.

- Brown, Thomas M., and Charles E. Miller. 2000. “Communication Networks in Task-Performing Groups: Effects of Task Complexity, Time Pressure, and Interpersonal Dominance.” Small Group Research 31 (2): 131–157. https://doi.org/10.1177/104649640003100201.

- Calver, Michael C. 2015. “Please Don’t Aim for a Highly Cited Paper.” The Australian Universities’ Review 57 (1): 45–51.

- Campanario, Miguel. 1993. “Consolation for the Scientist: Sometimes It is Hard to Publish Papers That are Later Highly-Cited.” Social Studies of Science 23 (2): 342–362. https://doi.org/10.1177/030631293023002005.

- Cancer Research UK. 2021. “Diversity Data in Our Grant Funding 2017–2019.”

- Cornwall, Claudia. 2014. Catching Cancer: The Quest for Its Viral and Bacterial Causes. London: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Darling, Emily S. 2015. “Use of Double-Blind Peer Review to Increase Author Diversity.” Conservation Biology 29 (1): 297–299. https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.12333.

- de Donato Rodríguez, Xavier, and Jesús Zamora Bonilla. 2014. “Scientific Controversies and the Ethics of Arguing and Belief in the Face of Rational Disagreement.” Argumentation 28 (1): 39–65. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10503-013-9300-4.

- DFG. 2020. “New Measures to Promote Gender Equality in Science and Academia.” Accessed April 29, 2023. https://www.dfg.de/en/research_funding/announcements_proposals/2020/info_wissenschaft_20_82/.

- Dotson, Kristie. 2011. “Tracking Epistemic Violence, Tracking Practices of Silencing.” Hypatia 26 (2): 236–257. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1527-2001.2011.01177.x.

- Emanuelsson, Ingemar. 1998. “Integration and Segregation—Inclusion and Exclusion.” International Journal of Educational Research 29 (2): 95–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-0355(98)00016-0.

- European Research Council. 2020. “Qualitative Evaluation of Completed Projects Funded by the European Research Council.” https://erc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/document/file/2021-qualitative-evaluation-projects.pdf.

- Fricker, Miranda. 2007. Epistemic Injustice: Power and the Ethics of Knowing. Oxford University Press.

- Gonsalves, Allison J., Anna Danielsson, and Helena Pettersson. 2016. “Masculinities and Experimental Practices in Physics: The View from Three Case Studies.” Physical Review Physics Education Research 12 (2): 020120. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevPhysEducRes.12.020120.

- Grim, Patrick. 2009. “Threshold Phenomena in Epistemic Networks.” Paper presented at the 2009 AAAI Fall Symposium Series, Arlington, VA.

- Grim, Patrick, Daniel J. Singer, Aaron Bramson, Bennett Holman, Sean McGeehan, and William J. Berger. 2019. “Diversity, Ability, and Expertise in Epistemic Communities.” Philosophy of Science 86 (1): 98–123. https://doi.org/10.1086/701070.

- Habermas, Jürgen. 1998. The Inclusion of the Other: Studies in Political Theory. Cambridge, Maldon: MIT Press.

- Ha, Tam Cam, Say Beng Tan, and Khee Chee Soo. 2006. “The Journal Impact Factor: Too Much of an Impact?” Annals-Academy of Medicine Singapore 35 (12): 911. https://doi.org/10.47102/annals-acadmedsg.V35N12p911.

- Heesen, Remco, and Liam Kofi Bright. 2021. “Is Peer Review a Good Idea?” The British Journal for the Philosophy of Science 72 (3): 635–663. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjps/axz029.

- Holman, Bennett, and Justin P. Bruner. 2015. “The Problem of Intransigently Biased Agents.” Philosophy of Science 82 (5): 956–968. https://doi.org/10.1086/683344.

- Horn, Lyn, Sandra Alba, Fenneke Blom, Marlyn Faure, Eleni Flack-Davison, Gowri Gopalakrishna, Carel IJsselmuiden, Krishma Labib, James V. Lavery, and Refiloe Masekela. 2022. “Fostering Research Integrity Through the Promotion of Fairness, Equity and Diversity in Research Collaborations and Contexts: Towards a Cape Town Statement (Pre-Conference Discussion Paper).”

- Hunt, Vivian, Sara Prince, Sundiatu Dixon-Fyle, and Lareina Yee. 2018. “Delivering Through Diversity.” McKinsey and Company 231:1–39. https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/people-and-organizational-performance/our-insights/delivering-through-diversity.

- Jackson, Susan E. 1996. “The Consequences of Diversity in Multidisciplinary Work Teams.” In Handbook of Work Group Psychology, edited by M.A. West, 53–75. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons.

- Jimenez, Jose L., Linsey C. Marr, Katherine Randall, Edward Thomas Ewing, Zeynep Tufekci, Trish Greenhalgh, Raymond Tellier, et al. 2022. “What Were the Historical Reasons for the Resistance to Recognizing Airborne Transmission During the COVID-19 Pandemic?” Indoor Air 32 (8): e13070. https://doi.org/10.1111/ina.13070.

- Kitcher, Philip. 1990. “The Division of Cognitive Labor.” The Journal of Philosophy 87 (1): 5–22. https://doi.org/10.2307/2026796.

- Kitcher, Philip. 1993. The Advancement of Science: Science without Legend, Objectivity without Illusions. New York: Oxford University Press on Demand.

- Kuhn, Thomas S. 1970. The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press.

- Kuhn, Thomas S. 1977. “Objectivity, Value Judgment, and Theory Choice.” In The Essential Tension, 320–339. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press.

- Kuhn, Thomas S. 2011. “9. The Essential Tension: Tradition and Innovation in Scientific Research.” In The Essential Tension, 225–239. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press.

- Kupferschmidt, Kai. 2018. “Max Planck Society, at a Crossroads, Seeks New Leaders.” American Association for the Advancement of Science.

- Ledin, Anna, Lutz Bornmann, Frank Gannon, and Gerlind Wallon. 2007. “A Persistent Problem: Traditional Gender Roles Hold Back Female Scientists.” EMBO Reports 8 (11): 982–987. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.embor.7401109.

- Lee, Carole J. 2015. “Commensuration Bias in Peer Review.” Philosophy of Science 82 (5): 1272–1283. https://doi.org/10.1086/683652.

- Leonelli, Sabina. 2022. Open Science and Epistemic Diversity: Friends or Foes? Philosophy of Science 89 (5): 991–1001.

- Lewis, E. Yvonne, and Richard C. Sadler. 2021. “Community–Academic Partnerships Helped Flint Through Its Water Crisis.” Nature Publishing Group.

- Longino, Helen. 2002. “The Social Dimensions of Scientific Knowledge.”

- Luzzi, Federico. 2016. “Testimonial Injustice without Credibility Deficit (Or Excess).” Thought: A Journal of Philosophy 5 (3): 203–211. https://doi.org/10.1002/tht3.212.

- McGlynn, Aidan. Forthcoming. “Epistemic Injustice: Phenomena and Theories.” Oxford Handbook of Social Epistemology.

- Naidoo, Antoinette Vanessa, Peter Hodkinson, Lauren Lai King, and Lee A. Wallis. 2021. “African Authorship on African Papers During the COVID-19 Pandemic.” BMJ Global Health 6 (3): e004612. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2020-004612.

- Nguyen, C. Thi. 2018. “Escape the Echo Chamber.” Aeon Magazine.

- O’Connell, David. 2007. “Neglected Diseases.” Nature 449 (7159): 157. https://doi.org/10.1038/449157a.

- Parkin, D. Maxwell, and Freddie Bray. 2006. “Chapter 2: The Burden of HPV-Related Cancers.” Vaccine: X 24:S11–S25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.05.111.

- Powell, Kendall. 2018. “These Labs are Remarkably Diverse–Here’s Why They’re Winning at Science.” Nature 558 (7708): 19–23. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-018-05316-5.

- Rosenstock, Sarita, Justin Bruner, and Cailin O’Connor. 2017. “In Epistemic Networks, is Less Really More?” Philosophy of Science 84 (2): 234–252. https://doi.org/10.1086/690717.

- Rowland, Ingrid D. 2009. Giordano Bruno: Philosopher/heretic. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Schkade, David, Cass R. Sunstein, and Reid Hastie. 2007. “What Happened on Deliberation Day.” California Law Review 95:915. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.911646.

- Sikimić, Vlasta, Kaja Damnjanović, and Slobodan Perović. 2023. “(Dis)satisfaction of Female and Early-Career Researchers with the Academic System in Physics.” Journal of Women and Minorities in Science and Engineering 29 (2): 25–50. https://doi.org/10.1615/JWomenMinorScienEng.2022038712.

- Sikimić, Vlasta, and Ole Herud-Sikimić. 2022. “Modelling Efficient Team Structures in Biology.” Journal of Logic and Computation 32 (6): 1109–1128. https://doi.org/10.1093/logcom/exac021.

- Sikimić, Vlasta, Tijana Nikitović, Miljan Vasić, and Vanja Subotić. 2021. “Do Political Attitudes Matter for Epistemic Decisions of Scientists?” Review of Philosophy and Psychology 12 (4): 775–801. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13164-020-00504-7.

- Solomon, Miriam. 2015. Making Medical Knowledge. Oxford University Press.

- Strevens, Michael. 2003. “The Role of the Priority Rule in Science.” The Journal of Philosophy 100 (2): 55–79. https://doi.org/10.5840/jphil2003100224.

- Sunstein, Cass R. 2007. “Group Polarization and 12 Angry Men.” Negotiation Journal 23 (4): 443–447. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1571-9979.2007.00155.x.

- Surowiecki, James. 2005. The Wisdom of Crowds. New York and Toronto: Anchor.

- Toole, Briana. 2019. “From Standpoint Epistemology to Epistemic Oppression.” Hypatia 34 (4): 598–618. https://doi.org/10.1111/hypa.12496.

- van den Besselaar, Peter, and Charlie Mom. 2021. “What Leads to Gender Bias in Review Panels?”

- Vislie, Lise. 2003. “From Integration to Inclusion: Focusing Global Trends and Changes in the Western European Societies.” European Journal of Special Needs Education 18 (1): 17–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/0885625082000042294.

- Vučković, Aleksandra, and Vlasta Sikimić. 2022. “How to Fight Linguistic Injustice in Science: Equity Measures and Mitigating Agents.” Social Epistemology 37 (1): 80–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/02691728.2022.2109531.

- Wapman, K. Hunter, Sam Zhang, Aaron Clauset, and B. Larremore Daniel. 2022. “Quantifying Hierarchy and Dynamics in US Faculty Hiring and Retention.” Nature 610 (7930): 120–127. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-05222-x.

- Weatherall, James Owen, and Cailin O’Connor. 2021. “Conformity in Scientific Networks.” Synthese 198 (8): 7257–7278. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-019-02520-2.

- Wellcome. 2020. “Our Commitment to Tackling Racism at Wellcome.” Accessed August 13, 2023. https://wellcome.org/press-release/our-commitment-tackling-racism-wellcome.

- Wu, Jingyi. 2023. “Epistemic Advantage on the Margin: A Network Standpoint Epistemology.” Philosophy and Phenomenological Research 106 (3): 755–777. https://doi.org/10.1111/phpr.12895.

- Young, Iris Marion. 2002. Inclusion and Democracy. New York: Oxford University press on demand.

- Zollman, Kevin J. S. 2010. “The Epistemic Benefit of Transient Diversity.” Erkenntnis 72 (1): 17–35. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10670-009-9194-6.