Abstract

British cities appear to be moving from a period of counter-urbanization to a period of reurbanization. One reason for this appears to be the growth of residential development in city centres. At the same time as there has been a boom in city centre housing, many cities appear to have experienced housing market failure in parts of the inner urban area. Through a study of Liverpool this article considers the evidence to support the notion that reurbanization is becoming an established trend, and why. What is the relationship between this emerging central area housing market and the surrounding inner urban areas? What are the implications for planning practice? The article concludes that there is evidence of reurbanization, partly driven by the economic revival of the city centre economy. But this emerging housing sector caters only for a niche population and makes a relatively inefficient contribution to housing supply. However, with the exception of student housing, it appears to be segmented from and not adversely impacting upon the inner-area housing market. If the goal is to broaden the appeal of city centre living to a wider social spectrum and to increase the efficiency of its contribution to housing supply, then its provision needs to be more carefully planned in terms of housing mix, local environmental conditions and amenities.

Introduction

Over the past decade evidence has begun to appear suggesting that many English cities are experiencing a degree of reurbanization after decades of counter-urbanization. One of the clearest indicators leading to the claim of reurbanization has been the emergence of ‘city centre living’. Private housing investment in these areas re-emerged during the 1990s and has become an established trend during the 2000s. However, at the same time as seeing a boom in city centre housing investment, many cities experienced a wave of disinvestment, low demand and even abandonment in parts of the inner urban area housing stock, especially around the turn of the 20th/21st century. In response, the Government established a series of ‘Housing Market Renewal Areas’ to tackle these problems. This raises a number of questions about the processes of urban change that are going on and the nature of the housing market within English cities. Is the growth of residential development in city centres evidence of reurbanization or is it merely a redistribution of housing investment and population between different parts of the urban core: notably between the inner urban area and the central area? What is the relationship between city centre housing markets and the surrounding inner urban housing markets? Are they linked or segmented? Are there spillover effects from the city centre that positively or adversely affect the inner urban areas, for example, through gentrification? Through a case study of Liverpool in North-west England, this paper explores these questions.

Reurbanization and the Emergence of City Centre Housing Markets

The process of reurbanization involves the movement of people back into the cities, and in particular the repopulation of the city centre and inner ring. It has been argued that reurbanization represents a phase of urban development in a recognizable urban lifecycle model (van den Berg & Klassen, Citation1987). Following studies of urban change in Western Europe, van den Berg & Klassen found evidence for a cyclical process of growth and decline in the patterns of urban development and similarities between cities in the paths of their urban development over time (Fielding & Halford, Citation1990, p. 8). The model identified four broad development phases: urbanization, suburbanization, disurbanization and reurbanization. Each phase is sub-divided into two stages relating to differences in the rate of population change in both the core and the suburban ring, resulting in a more sophisticated eight-stage model highlighting the potential for both relative and absolute population growth and decline. According to the model the initial phases of urbanization and suburbanization indicate a period of overall growth for the urban area, but gradually net migration gains are outweighed by net migration losses leading to a phase of disurbanization (or counter-urbanization) as population decline in the core is replicated in the suburbs leading to overall decline. According to the model, reurbanization begins with relative growth in the core (i.e. as population levels stabilize in the core, they continue to decline in the suburbs) and peaks with absolute population growth in the urban core and suburbs.

The dominant population trend affecting most British cities throughout the latter half of the 20th century was dispersal and counter-urbanization (Champion, Citation1992, Citation2001). All of the major cities lost population, and the central areas in particular became virtually devoid of occupied housing accommodation. However, using evidence from Glasgow, Lever (Citation1993, p. 282) suggested that the combination of restructuring of urban economies, demographic change and more proactive urban policy meant that post-industrial cities in the UK were in a position to move from the disurbanization phase in the model to relative, if not absolute, reurbanization.

Since then a body of evidence has been accumulated to suggest that, over the past decade, relative and absolute reurbanization has occurred in many British cities (for example, Couch, Citation1999; Seo, Citation2002; Barber, Citation2007; Bromley et al., Citation2007). Boddy and Lambert (Citation2002) found that city centres in a number of the largest UK cities were undergoing a process of rapid change affecting their physical form and land uses. Residential development in central locations, formerly dominated by industrial and commercial uses, and a new emphasis on urban lifestyles and urban culture are said to have been fundamental to the process of reurbanization.

Initially one or two pioneering city councils developed policies to encourage the return of housing investment to the city centre. One of the first was Manchester City Council who, in their 1984 Manchester City Centre Local Plan argued that more housing would add to the quantity and variety of the housing stock generally, promote greater diversity and activity and bring life back to the central area. (Couch, Citation1999, p. 73)

| • | A supply of sites and premises for which more profitable uses did not exist; | ||||

| • | A demand for small urban dwellings arising from changes in household structure; | ||||

| • | A demand for student accommodation arising from recent changes in higher education policy; | ||||

| • | Changes in public policy, including the provision of substantial development subsidies, that sought to promote city-centre living as part of a response to the aim of developing more ‘vital and viable’ city centres and as a contribution towards more sustainable cities. (Couch, Citation1999, p. 82) | ||||

In 1997 the Labour Government came to power with a strong commitment to regenerate British cities. This led to the publication of the Urban Task Force (Citation1999) report Towards an Urban Renaissance and the Urban White Paper on urban policy Our Towns and Cities: The Future: Delivering an Urban Renaissance (Department of the Environment, Transport and the Regions, 2000). Lees (Citation2003) considers both reports as the powerhouse setting a course for ‘urban renaissance’ in England and the UK. In consequence, a key element of urban policy over the past 10 years has been to encourage the redevelopment of brownfield sites, with residential development in the central areas of cities being a major outcome.

By 2001, Madden et al. could report that the population of Liverpool city centre had grown by almost 300%—from 2, 340 in 1991 to approximately 9,000 in 1999. They found that these new residents were predominantly young, male, single and skewed heavily towards managerial and professional occupations (Madden et al., Citation2001). They also tended to have lower than average car ownership and a noticeable higher proportion of people who walked to work. Thus they concluded that, in Liverpool, city centre living responded to the demographic trend towards more smaller households, did appear to promote more sustainable lifestyles, was having a positive effect on social mix, had the potential to support wider economic regeneration and had positive implications for the conservation and the re-use of vacant land and derelict buildings (Madden et al., Citation2001).

By the early years of the new century demand seems to have divided into a market for housing investment on the one hand, and a market for housing occupation on the other. According to Allen and Blandy:

Rising property prices and growing demand for rented property from young people seeking a city centre ‘experience’ has resulted in an expansion of the buy-to-let investors market. This has led to an increase in investor demand for small, studio, apartments that can be let at competitive rents. (Allen & Blandy, Citation2004, p. 2)

By the end of 2005 further conclusions could be drawn. A report for the Centre for Cities suggested that the growth of city centre living was the most visible symbol of urban renaissance. Whilst agreeing with Madden et al. that residents were mostly young and single, they argued that the level of transience was quite high, with turnover being three times the UK average. The report concluded that most residents left when they started families: pushed by the lack of space and services and pulled by the attractions of the suburbs. It was also suggested that the amount of city centre living reflected rather than drove economic growth. It did best in cities that were doing best (Nathan & Urwin, Citation2006)

But transience might be reduced. Allinson (Citation2005), in a study of metropolitan migration patterns, noted that some areas of cities (including developments such as Salford Quays in Greater Manchester and Brindley Place in Birmingham) had certain characteristics that correlated strongly with in-migration, such as high dwelling prices, high salary levels and high social class, together with recent immigrants and young adults. The problem was that many of these variables also correlated with out-migration: the problem being that these were essentially amongst the most mobile social groups within society. The trick for policy-makers, he suggested, was to promote those characteristics that may correlate with in-migration rather more strongly than out-migration. These he identified as the presence of a rented housing stock and a younger adult population, higher salaries and higher value housing (Allinson, Citation2005, pp. 178–179).

In a recent study of Bristol, where the emergence of a strong private rented sector is a key characteristic of the central area housing market, Boddy (Citation2007) has suggested this new wave of development has resulted from a combination of factors, including: national economic recovery and its impact on investment and property markets (including low interest rates and low returns on equities)—in particular the emergence of an investment market in city centre residential units, for example from the growing demand for personal pension provision (i.e. a growing number of individuals and firms who wished to become landlords); a latent demand for renting apartments, for example resulting from changes in demography and household structure, changing occupational structures and career paths (i.e. a growing number of households who wished to become tenants); government policy to promote city living (notably Planning Policy Guidance Note 3: Housing); and a rapid growth in organizational learning within the property and development sectors (Boddy, Citation2007, p. 103).

Thus, there is no doubt that, after a long period of decline, most major British cities have gained population in recent years. The exception is Liverpool, but even here there was a sharp fall in the rate of population decline during the same period (see ).

Figure 1. Population change in selected British cities. Source: Mid-year Population Estimates 1981–2007; Census Dissemination Unit LCT 1971–1981.

Switching the focus more specifically to city centres, and using city centre boundaries recognized by the planning authorities, Bromley et al. (Citation2007) used data from the 1991 and 2001 census to assess and compare population change in Birmingham, Bristol, Cardiff and Swansea city centres, as shown in . According to their analysis, all city centres in their investigation gained population during he 1990s—ranging from a modest 8% in Birmingham to dramatic increases of over 60% in both Bristol and Cardiff.

Table 1. Population change in selected British city centres, 1991–2001

Looking more closely at the situation in Liverpool, and using more recent data based on mid-year estimates since the 2001 census, it can also be seen that although the city as a whole continued to show slight population decline, the city centre grew significantly (see ). It is in the rest of the city, the inner and outer suburbs, that decline is continuing. Thus whilst some British cities are entering a period of absolute reurbanization, Liverpool is still in the relative reurbanization phase of the lifecycle model.

Table 2. Recent population trends in Liverpool

The emergence of this period of relative reurbanization in Liverpool might be explained by considering two particular factors that have strongly influenced housing demand: the changing nature of employment in the urban area, and the growth of higher education.

Economic Development

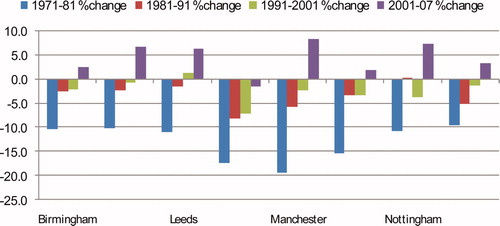

The recent economic revival of many British cities has been quite profound, particularly when comparing the extent of economic decline and recession these cities experienced in the 1970s and 1980s. Whilst this urban renaissance at the local level has been aided by national economic revival and stability, several major cities have outperformed the national rates on a number of economic indicators including employment change as shown in .

Table 3. Long-term annual change in employment (%) in selected core cities

Further analysis of employment growth between 1998 and 2007 in Liverpool identifies two key growth sectors: firstly, banking, finance and insurance, where jobs increased by 47.1%; and secondly, public administration, education and health, where jobs increased by 25.7%. Over the same period the most significant decline was in the manufacturing sector, continuing a much longer-term trend. By 2007 only 5.2% of jobs in Liverpool were in manufacturing; in contrast, 60.8% of jobs were in the two key growth sectors (Annual Business Inquiry Employee Analysis). These trends suggest a geographical redistribution with employment growth focused particularly in the city centre.

It is estimated that the city centre accounts for more than 50% of all financial services and business services jobs in Liverpool, more than 40% of all jobs in hotels and restaurants, and more than 30% of all retail and other service jobs in Liverpool (Pion Economics, Citation2006, p. 7). Many of these jobs are characterized by higher level occupations, with some focused on niche markets or sectors; for example, jobs in creative industries are largely concentrated in the city centre. Thus Liverpool city centre is likely to have been the location for as much as one-half of all job growth in the city over this period (around 12, 000 jobs). The size and nature of this job growth is likely to have been a key factor in the growth of demand for ‘city centre living’.

Students and Higher Education

It has been established that much of the growth in jobs has been in technology-led and knowledge-based industries. This is partly reflected by the concentration of universities and related higher education institutions in cities: indeed most major British cities outside London have at least two universities, with Liverpool hosting three. The University of Liverpool is situated in a campus setting on the fringes of the city centre although, like many red-brick universities, it owns halls of residences in the suburbs of the city. Liverpool John Moores University is located mainly in the city centre, with one suburban campus. In contrast, Liverpool Hope University has a main campus building in Childwall, some 4 miles from the city centre, with a much smaller inner-city campus at Everton.

For the purpose of this paper, the trends in full-time undergraduate students are of more significance than other types of students as these are the main grouping of students likely to have an impact on demand for housing in the city. As demonstrated in , all three universities in Liverpool have recently expanded their student intake with over 7, 400 more full-time undergraduate students in 2006/07 compared with 1995/96. The vast majority of these students are studying in Liverpool city centre.

Table 4. Full-time undergraduate students at Liverpool universities

Thus the emergence of city centre living as a dimension of reurbanization appears to have resulted from a combination of urban policies and housing market forces pulling in a similar direction over the past 10–15 years. The result has been a significant shift in the location and type of housing supplied in British cities, much of which has become occupied by a population that is characterized by small adult households with a high level of transience. In Liverpool the city centre population has increased by more than 17, 000 since 1991. It seems likely that much of this increased demand has been stimulated by growth in the higher education sector (student numbers) and the post-industrial nature of recent economic development.

The Contemporary Housing Market in Liverpool City Centre

Since the millennium, housing investment in Liverpool city centre has accelerated beyond all expectations. According to Liverpool City Council, between 1988 and September 2008 nearly 9, 000 dwellings were completed in the city centre. To this must be added around 2, 000 dwellings under construction in the last quarter of 2008 and a further 5, 000 in anticipated schemes. However, as a consequence of the recent downturn in the housing market, there must be serious doubt as to how many of these anticipated schemes will actually come to fruition in their currently proposed form (see ).

Figure 2. Residential completions in Liverpool city centre, numbers of units (conversions and new-build), 1988–2008 and anticipated. Sources: Liverpool City Council, City Centre Living Residential Development Update(s) May 2006, November 2007 and September 2008. Completions prior to 1996 are derived from Couch (1999).

From it can be seen that residential development in the city centre has gone through a number of phases. In the first phase, prior to 1996, development was to be found mainly in the former docklands (Waterfront) and in the northern (Marybone) and eastern (University) fringes of the central area (see for the location of districts). Over the following decade, development continued in these fringe districts but also expanded inwards towards the core of the city centre, notably in the Commercial (traditional office) quarter, Ropewalks (former warehouses, workshops, retail fringe) and Lime Street Gateway.

More recently the spatial emphasis has shifted again, with the majority of the schemes on-site or anticipated being concentrated in the Commercial, Baltic, Retail and Waterfront areas. Whilst virtually no residential development took place in the retail core in the early years, by 2008 more than 500 units were under construction, mainly as part of the Grosvenor Estates' new ‘Liverpool One’ development.Footnote1 There was also some spread outwards from the city centre, with more than 600 dwellings on site or anticipated in the Baltic Triangle to the south of the central area—although, as suggested above, in the current recession it must be doubted whether the renaissance of the city centre will continue to trickle down to more marginal fringe locations such as this.

The early docklands (Waterfront) development had been largely the product of the regeneration efforts of the Merseyside Development Corporation (1981–1998), and much of the development in the eastern fringe of the city centre in the 1990s was supported through the ‘City Centre East’ City Challenge initiative. At the same time, development in the Ropewalks was encouraged through the ‘Ropewalks Partnership’—a joint initiative between the City Council, English Partnerships and the local community (Couch & Dennemann, Citation2000).

However, the extent to which this growing stock of dwellings has contributed to the useful dwelling stock of the city is perhaps less than it might seem at first sight. There are a number of reasons for this. Firstly, voids (vacancies) tend to be higher in the city centre housing stock, estimated at 9.0% in 2007 compared with a city average of 4.9% (Liverpool City Council, Citation2007). This may be partly due to the rapid speed of development creating temporary imbalances between supply and demand, but it may also be that during the housing boom some purchasers were using their property as an investment asset, neither seeking to occupy nor to let their property but content to benefit from anticipated increases in capital value over time.

Secondly, leaving aside the student accommodation, the vast majority of the residential developments in the city centre comprise one-bedroom or two-bedroom apartments almost exclusively occupied by one-person or two-person adult households. There is virtually no accommodation designed for families, nor families in occupation. In as much as these households might formerly have occupied dwellings in the rest of the city, the development of these city centre apartments has probably increased the spatial segregation of the population by household type and, to some degree, by age as well.

Thirdly and linked to the second point, average household size is continuing to fall across the city, and particularly the city centre. Average household size in Liverpool's Central Ward was 1.60 pph in 2001 compared with 2.11 persons per household for the city as a whole (Liverpool City Council, Citation2007, .5). This means that whilst dwelling completions in the central area have been substantial, their contribution to accommodating the population is limited.

Finally, there is a known tendency for householders in the private sector to ‘under-occupy’ dwellings—that is to say, many households will purchase a dwelling that is larger than their statistical needs (e.g. single-person households may occupy a two-bedroom flat). In contrast, in the social housing sector, landlords generally try to match household and dwelling size more closely. Given that virtually all recent housing completions in the city centre are for the private sector, under-occupation seems likely. Taken together, these factors suggest that dwelling completions in the city centre are contributing proportionately less to the accommodation of the population than is the case for dwelling completions elsewhere in the city.

Furthermore, a large proportion of city centre residents are transient temporary residents with little commitment to the area, either to stay or to contribute to community development. Allen and Blandy's (Citation2004, p. 14) two-fold classification of short-term ‘experiential’ and longer term ‘authentic’ city centre dwellers is helpful in measuring these groups. In Liverpool city centre it is likely that the first group would include all the occupants of the student bedspaces (around 9, 900) together with a proportion of other residents. National trendsFootnote2 and local anecdotal evidence would suggest that the proportion of dwellings being completed for housing investors in the buy-to-let sector increased substantially after 2005, declining only as the recession began to bite in 2008. Our own data suggests that of the 996 dwellings offered for occupation in Liverpool City Centre at the end of 2007, 67% were for sale and 33% for rent.Footnote3 It can be assumed that rented dwellings are mainly catering for short-term city centre dwellers, and no doubt a proportion of the dwellings purchased for owner occupation are intended for resale within a relatively short period of time. Thus it seems plausible to suggest that perhaps no more than one-half of those currently living in the city centre are ‘authentic’ long-term residents. If students are included then this proportion could be as low as a quarter. Our surveyFootnote4 indicated that at the end of 2007 there was a significantly higher proportion of the stock offered for resale in the central core and Waterfront areas compared with the eastern fringe University, Canning and Hope areas (between the traditional inner urban residential districts and the central core). This suggests that ‘authentic’ residents may favour these latter areas whereas ‘experiential’ residents prefer the central core and Waterfront.

The City Centre Housing Market and its Relationship with the Inner Urban Areas

An important question that has to be asked in relation to the emerging city centre housing market is how it has affected surrounding neighbourhoods. This is a matter of particular concern to policy-makers responding to the apparent low demand for housing in some of these inner urban areas:

Low demand for housing in the older urban areas, and even abandoned housing, is a significant and growing problem. It affects some 440,000 dwellings in the region. (Office of the Deputy Prime Minister, Citation2003, p. 6)

On the one hand, the City Council have indicated that housing development outside the HMRA and certain other strategic housing sites would only be supported where significant regeneration benefits could be demonstrated and where the development would not undermine the objectives of the HMRA (Liverpool City Council, Citation2005, para. 6.1). In other words, restrictions are to be placed on housing development in the rest of the city in order to encourage housing investment in the problematic inner urban areas. Yet on the other hand, no such restrictions apply in the city centre—on the basis that: it falls within the HMRA; its continuing regeneration is critical to the economic prosperity of the city; many of the regeneration sites in the city centre lend themselves to mixed uses including a residential component; for some derelict or under-used buildings, residential development offers the best alternative use; and residential development adds to the vitality of the central area (Liverpool City Council, Citation2005, para. 4.8). In support of this approach the City Council argue that they are confident the city centre represents a distinct market segment.

It is considered that city centre housing constitutes a distinct market ‘segment’—catering to smaller households, generally without children—which should be recognised and supported by a policy approach which generally seeks higher density development than in other parts of the City. (Liverpool City Council, Citation2005, para. 4.8)

The city centre market can be seen to be having a positive impact by attracting households to make long-range moves into Liverpool. However, the ability of the city market to retain households in the long-term—as they mature and require family housing—has been questioned. Moreover, whilst high volume city centre apartments have contributed significantly to achievement of RSS housing targets, the extent to which they genuinely aid population retention and meet local demand for housing is not clear … One stakeholder felt that the development of the city centre student market (private halls of residence) ‘has had a detrimental effect in traditional student renting areas’ … the boom of private halls of residence has directly led to the decline of traditional student neighbourhoods … this does demonstrate that there is some interaction between the city centre market and the wider Pathfinder area. (ECOTEC, Citation2007, pp. 8–9)

It is worth reflecting more broadly on why low demand should exist alongside high levels of housing demand in nearby areas. It is an apparent paradox that low demand should exist alongside a nationally projected housing need for more than 4 million additional dwellings over the next 20 years. Holmans (Citation1999) explored the issue and suggested that the explanation could be found at the regional and sub-regional level. Whilst out-migration from cities in the north of England had reduced housing pressures and decreased prices within the cities, there had been no general collapse of demand for privately owned housing:

very important evidence of this is that as the housing market came out of the slump in the first half of the 1990s the upturn in new building for private owners was proportionately as large in the north as in the south of England. (Holmans, Citation1999, p. 336)

old though cheap housing is not in competition with new houses; hence instances of second-hand houses that are unsaleable owing to deficient demand. (Holmans, Citation1999, p. 336)

shows the growth of the housing market in the inner city and central area of Liverpool. As the owner-occupied sector has grown, both absolutely and as a percentage of dwellings in all tenures, so both the inner urban and central area housing markets have grown. In 1997 the central area (postcodes L1–L3) represented just 1.5% of dwellings sold in Liverpool. At that time, the inner areas (L4–L8) represented just under 20% of sales. By 2002 sales in the central area had increased to nearly 8% of total sales and the inner areas to just over 22%. By 2006 the figures were 11% for the central area and 31% for the inner area (Land Registry data). This suggests that both markets had been growing rapidly in terms of volume of sales and that housing market activity in the city was becoming increasingly concentrated in these inner and central areas. However, one effect of the housing market recession that began to bite in 2008 was that the volume of sales fell sharply across the city, but with the central area recording a sharper fall (the volume of sales in 2008 was 54% below the 2006 figure) than the inner areas (−42%) and the rest of the city (−39%). There is nothing here to suggest that the emergence of a central area housing market has had any adverse impact on the volume of dwelling sales in the inner urban area.

, which considers dwelling price trends, also shows that the central area housing market is segmented from that of the inner urban area, commanding a quite different order of dwelling prices. However, there is some evidence to support the notion that until 2001/02 dwelling prices in the central area were rising faster than the city average and were possibly partly responsible for the depression in inner urban dwelling prices that was evident in the period 1997–2002. After 2003, coincident with the launching of the HMRA, dwelling prices in the inner urban area begin to recover. Again, the reaction to the recession of different spatial segments of the city's housing market is different. Between 2006 and 2008 dwelling prices continued to rise in the central area (by 5% over the 2 years) and in the inner urban areas (by 12%), whereas figures for the city as a whole show a fall of 3% over the same period. An explanation may lie in the fact that whilst the volume of sales has fallen sharply in the central area, many of the dwellings sold are new-build, high-priced, luxury apartments. In the inner urban areas the activities of the local authority and registered social landlords may be having a positive effect, especially in the housing market renewal areas. It is in the rest of the city (the outer suburbs), in a housing market dominated by sales of existing dwellings and little public-sector intervention, that prices have fallen most sharply.

There is another reason to suggest segmentation of the inner city and central area housing markets: a different mix of dwellings on the market. At no time since 1999 has the proportion of dwellings sold in the central area that are flats/apartments fallen below 80% whilst over the same period the proportion of dwellings sold in the inner urban area that are flats/apartments has never exceeded 20% (Land Registry data). This suggests a high level of ‘product differentiation’ between the central and inner urban areas.

There are also differences in the marketing of property in these two zones. The marketing of dwellings for sale in the central area (postcodes L1–L3) is dominated by six estate agents (City Residential, King Sturge, Venmore (CC office), KMC, Sutton Kersh (CC office), and Andrew Louis). Of the 440 properties offered for sale by these firms in November 2007, only 22% were outside the city centre. On the other hand, the marketing of dwellings for sale in the inner urban area (postcodes L4–L8) is dominated by five estate agents (Venmore (suburban offices), Entwistle Green, Halifax, Sutton Kersh (suburban offices) and BE properties). From these firms, of the 137 properties sampled in November 2007, only 7% were in the city centre.Footnote5 Thus the marketing of residential properties in the central and inner urban areas is largely handled by different agents or at least by different offices, suggesting a segmentation of the market.

Furthermore, the ways in which properties are advertised differs substantially between the two areas. In the city centre, advertisements tend to promote the joys of city living:

The Foundry is located in one of Liverpool's most desirable postcodes—L1. Deep in the heart of the famous Ropewalks area and Liverpool Maritime Merchant City World Heritage Site, the Foundry is in walking distance of all of Liverpool's main attractions: the coolest bars and clubs, the most sensational restaurants and the bright lights of the theatre.

The apartment is conveniently located to benefit from all the services and amenities of Liverpool city centre including close proximity to Liverpool's universities, shopping district and theatres.

White Court is situated in central Liverpool, on the edge of China Town and all the amazing dining and entertainment experiences that the area offers. White Court is also just a stone throw's away from the city's central shopping area. Easy for commuting, for dining and for fun with friends; White Court has the perfect location.

Conveniently located within Anfield, Rosemount offers residents a choice of high quality, energy efficient new homes … Gardens and attractive landscaped areas will ensure that Rosemount is set in a lovely environment.

There are a good range of primary and secondary schools within the immediate catchment area.

Three bedroom semi-detached property situated in a popular development, located close to all local amenities, including shopping and transport links.

St. James House sits proudly on a well established road on the fringe of Sefton Park. Convenient for local amenities, it is also but a short distance from John Lennon airport and the city centre.

There is clearly a degree of market segmentation between the central area and inner area housing markets. The central area offers a substantially different product—mainly one-bedroom and two-bedroom apartments to a different market sector—mainly small adult households, at a price level that averages around twice that which is obtained in the inner areas. Central area dwellings are also marketed differently and usually by different agencies. Nevertheless, there are some connections between the two areas. The development of student accommodation in the central area does seem to have had some impact on the student housing market in the inner areas.

What are the Implications for Planning of this Nascent Reurbanization?

Lever (Citation1993) argued that reurbanization raised four policy implications: the necessity to treat the whole conurbation as one planning unit; that reurbanization offers the prospect of greater social integration; that the building of luxury homes in the city (centre) would have a greater benefit than building low-income housing because of ‘trickle down’ effects; and that, in the post-industrial economy, competition between cities would become ever more important and so good urban environments and living conditions take on a new economic importance for cities. Tallon and Bromley suggest that social inclusion would be advanced by encouraging city centres to develop ‘a more balanced array of housing schemes aimed at a broader range of social classes’ (2004, p. 785). The argument is further developed in Bromley et al., where the authors point out that ‘the infrastructure for families is poorly developed in British city centres’ (2005, p. 2425). Allen and Blandy (Citation2004) raise a number of detailed issues concerning the need to appropriately manage new apartment blocks and the city centre environment more generally. Their key point is that higher density residential developments and mixed uses brings a strong potential for conflicts between residents and between residents and other city centre users that needs to be carefully managed.

This study of Liverpool allows us to comment on some of these remarks.

Firstly, it seems clear that whilst there is a degree of segmentation between city centre, inner urban and suburban housing markets, there is also some interaction. The need for the coordination of plans and policies across the conurbation becomes self-evident, and may be realized following the recent changes to the geographic focus of Liverpool Vision (Liverpool's economic development company). From 1999 to 2008 Liverpool Vision had facilitated and overseen redevelopment specifically in the city centre. Its remit has now changed to include other regeneration priority areas elsewhere in the city, and this may impact on the spatial distribution of housing investment.

Secondly, there is mixed evidence about the effects of reurbanization (i.e. urban compaction) upon social integration. Burton (Citation2000) concluded that higher density urban form (the compact city) could reduce social segregation but might have other negative social impacts, including less domestic space, lack of affordable housing, increased crime levels and lower levels of walking and cycling. Whilst the building of apartments in the city centre has led to a degree of reurbanization, most of the developments are of a single type—small apartments, occupied by a very narrow social spectrum (mainly younger, smaller, affluent adult households)—and cannot in any substantial sense be said to increase social integration. Therefore, to the extent that social integration is a goal of planning, policies will need to be devised to increase the mix of dwelling types (including family housing) and tenures (including more affordable housing) in city centres. With particular reference to Liverpool, current planning guidance (Liverpool City Council, Citation2005, p. 14) acknowledges that ‘city centre housing constitutes a distinct “segment” catering to smaller households, generally without children’. The policy has been to seek much higher density development in the city centre, and this seems to have had the effect of reinforcing the centre's attraction for some social groups whilst reducing its appeal to others.

Thirdly, for ‘trickle-down’ to benefit lower-income households the luxury dwellings being provided in the city centre would have to be largely occupied by households who were vacating dwellings in the rest of the city that were appropriate and attractive to lower-income households. There are a number of problems with this thesis. Firstly, it is difficult to reconcile this with the finding of ECOTEC that ‘the city centre market can be seen to be having a positive impact by attracting households to make long-range moves into Liverpool’ (2007, p. 8). However a recent survey of city centre living in Nottingham found that only 17% were new households and 58% of residents had moved within the city (University of Nottingham Survey Unit, 2007). Those who are moving to Liverpool city centre, being almost entirely small adult households, are unlikely to be releasing very much appropriate and attractive housing in the rest of the city that could filter down to lower-income groups. In contrast, affordable housing provided across the city by social housing providers and others directly and efficiently responds to the measured needs of specific social groups.

In a survey for Liverpool Vision (Citation2001), it was found that 74.2% of respondents said the city centre did not have a clean environment; 76.6% said they did not think that the city centre had enough parks and open spaces; 92.9% felt that buildings needed to be better maintained; and 76.6% felt there was too much dereliction. If it is the desire of policy-makers to turn more city centre residents into ‘authentic’ residents with a longer-term commitment to the area, especially starting a family in the city centre, then there is clearly a lot to be done. Perhaps this is the greatest failing of town planning with regard to city centre living; many of the complaints of residents are about the local environment. Noise from outside including traffic noise/emergency sirens/clubs and bars/late-night drinkers was the ‘least liked’ aspect of city centre living, raised by 41% of respondents in the Nottingham survey (University of Nottingham Survey Unit, 2007, pp. 30–35). Inadequate parking and lack of local residential amenities (grocery stores, etc.) were other complaints. A similar survey in Leeds (Unsworth, Citation2007, p. 738) found that lack of green space was the most influential factor cited by residents moving out of the city centre, followed by ‘having children’ and ‘inadequate living space’. This is where town planning should be able to help: in requiring building forms that minimize noise intrusion and planning the development of amenities in parallel with population growth.

There is little doubt of the increasing competition between cities to attract both post-industrial employers and workers. The ‘State of English Cities’ report has demonstrated the failings of various British cities in this regard. It emphasizes the importance of improving the ‘livability’ of cities. The report calls for better quality design and a greater understanding of the importance of local environmental quality. Liveability, it suggests, should be more explicitly integrated into the higher level structures such as Local Strategic Partnerships (Office of the Deputy Prime Minister, Citation2006, p. 32). With reference to Liverpool, progress has been made in the provision of support services, including new health centres, dentists and day nurseries, whilst a number of convenience and grocery stores have opened recently. In addition the central area of Liverpool continues to be well served by primary schools, and the overall appearance of the city centre is undoubtedly better than it used to be, helping create the conditions for a more sustainable community in the city centre.

Conclusions

According to the urban lifecycle model there is a cyclical process of urban change with four clearly defined stages: urbanization, suburbanization, counter-urbanization and reurbanization. When the model was devised, many British cities were clearly in the counter-urbanization stage, characterized by severe levels of population decline. Reflecting on the predictive nature of the model, Lever (1993) outlined the potential for British cities to move from a period of counter-urbanization into a period of reurbanization, although at the time he was unable to find much evidence of reurbanization. Since then research into the dynamics of population change during the 1990s has provided ample evidence of reurbanization in a number of British cities (for example, Bromley et al., Citation2007), with in some cases dramatic levels of population growth concentrated in revitalized city centres. With specific reference to Liverpool, the authors have sought to use mid-year estimates to analyse population change since the 2001 Census. Using these data it can be seen that overall Liverpool has experienced significant population growth in the city centre but continuing population decline in the rest of the city. In the context of the model, therefore, Liverpool is in a period of relative reurbanization but has yet to experience the more general urbanization predicted by the model, with population growth across the whole city.

The key seems to be that urban policies, economic development trends and housing and property market forces have been pulling in a similar direction over the past 10–15 years, resulting in rising central area populations. However, this population in Liverpool as elsewhere is characterized by students and other adult households without children and with a high level of transience. Families are virtually absent from these developments, even in the most mature and stable market areas in eastern fringes of the central area adjoining traditional inner urban residential districts. Many of these dwellings offer a spaciousness and quietude that is not available elsewhere in the central area. They are also expensive and therefore not affordable by many young family households.

The central area market differs from the inner area housing market in a number of ways: in general it offers a different product aimed at a different type of households at a different price level and marketed in a different way. The effects of the housing market recession that emerged in 2008 are different in the central and inner urban areas, with the former experiencing a sharper fall in sales but with prices holding up more strongly. Only in the student housing market does there seem to be any strong connections between the two areas. In Liverpool this segmentation is acknowledged by the Council and has been supported by policy, notably on residential density, but also indirectly in relation to wider city centre policies promoting a vibrant evening and night-time economy, possibly to the disadvantage of resident groups.

In order to achieve a more sustainable community in the city centre, there are a several implications for policy-makers based on this case study of Liverpool. The most important would seem to be that the central area housing that has been developed so far in Liverpool has not contributed significantly to social integration. It is too homogeneous and aimed at too narrow a social group. In order to make a more substantial contribution it is probably necessary to reduce the amount of transience in the central area population and to encourage occupation by a wider range of social groups. This suggests that planning departments need to adopt a more proactive forward-planning approach and a rather more robust attitude to the control of city centre residential developments: dealing with residents' concerns about noise and amenity, and making greater provision for the kind of facilities households would expect to find in more established residential areas, such as convenience shopping, health, welfare and recreational facilities. In addition, more affordable and possibly more flexible apartments—particularly in the ‘quieter’ areas of the city centre—may encourage more families either to move in or to stay, resulting in a more stable community with a longer-term commitment to city living. This might also have the effect of reducing segregation between the central and inner urban housing market areas, making the coordinated planning of these two markets even more important.

One consequence of the housing market recession is that the process of reurbanization is likely to be slowed. However, this may provide a breathing space that would allow policy-makers to reflect on the achievements and shortcomings of a decade of very rapid central area housing investment and to adjust plans and development management requirements in light of the comments made above.

Notes

1. Liverpool One Project, a £1 billion scheme covering 17 hectares of the city centre. Opened during 2008, it contains 150, 000 square metres of retail space as well as a park, hotels, restaurants, apartments and a multi-screen cinema.

2. The number of buy-to-let mortgages increased nationally from 130, 000 in 2002, to 225, 900 in 2004 and to 329, 100 in 2006 (Council of Mortgage Lenders, Statistics, Table MM17.Available at http://www.cml.org.uk/cml/statistics, accessed 28 November 2007), as against a rather more modest rise in UK housing completions from 175, 235 in 2001/02, to 190, 427 in 2003/04 and to 213, 372 in 2005/06 (DCLG Housing Live, Table 253 Housebuilding. Available at http://www.communities.gov.uk/housing/housingresearch/housingstatistics/housingstatisticsby/housebuilding/livetables, Accessed 12 March 2008).

3. Authors' survey of advertisements at www.rightmove.co.uk (accessed 19 November 2007).

4. Authors' survey of advertisements at www.rightmove.co.uk (accessed 19 November 2007).

5. Authors' survey of advertisements at www.rightmove.co.uk (accessed 19 November 2007).

References

- Allen , C. 2007 . Of urban entrepreneurs or 24-hour party people? City-centre living in Manchester, England . Environment and Planning A , 39 ( 3 ) : 666 – 683 .

- Allen , C. and Blandy , S. 2004 . The Future of City Centre Living: Implications for Urban Policy , London : Department for Communities and Local Government .

- Allinson , J. 2005 . Exodus or renaissance? Metropolitan migration in the late 1990s . Town Planning Review , 76 ( 2 ) : 167 – 189 .

- Barber , A. 2007 . Planning for sustainable re-urbanisation: Policy challenges and city centre housing in Birmingham . Town Planning Review , 78 ( 2 ) : 179 – 202 .

- Boddy , M. 2007 . Designer neighbourhoods: New-build residential development in nonmetropolitan UK cities—the case of Bristol . Environment and Planning A , 39 ( 1 ) : 86 – 105 .

- Boddy , M. and Lambert , C. 2002 . Transforming the City: Post-Recession Gentrification and Re-urbanisation , (Bristol : University of the West of England) . CNR paper No.6

- Bromley , R. D. F. , Tallon , A. R. and Thomas , C. J. 2005 . City centre regeneration through residential development: Contributing to sustainability . Urban Studies , 42 ( 13 ) : 2407 – 2429 .

- Bromley , R. D. F. , Tallon , A. R. and Roberts , A. J. 2007 . New populations in the British city centre: Evidence of social change from the census and household surveys . Geoforum , 38 : 138 – 154 .

- Burton , E. 2000 . The compact city: Just or just compact? A preliminary analysis . Urban Studies , 37 ( 11 ) : 1969 – 2001 .

- Champion , A. G. 1992 . Urban and regional demographic trends in the developed world . Urban Studies , 29 ( 3–4 ) : 461 – 482 .

- Champion , A. G. 2001 . “ Uurbanization, suburbanization, counterurbanization and reurbanization ” . In Handbook of Urban Studies , Edited by: Paddinson , R. 143 – 161 . London : Sage .

- Couch , C. 1999 . Housing development in the city centre . Planning Practice & Research , 14 ( 1 ) : 69 – 86 .

- Couch , C. and Dennemann , A. 2000 . Urban regeneration and sustainable development in Britain: The example of the Liverpool Ropewalks Partnership . Cities , 12 ( 2 ) : 137 – 147 .

- Department of the Environment . 1993 . Town Centres and Retail Development (PPG6) , London : HMSO .

- Department of the Environment, Transport and the Regions . 2000 . Our Towns and Cities: The Future: Delivering an Urban Renaissance , London : HMSO .

- ECOTEC . 2007 . Adjacency and Displacement Effects of New Heartlands HMR Pathfinder , Liverpool : New Heartlands Housing Renewal Partnership .

- Fielding , T. and Halford , S. 1990 . Patterns and Processes of Urban Change in the United Kingdom , London : HMSO .

- Holmans , A. 1999 . Low demand for housing: Where and why? . Town and Country Planning , November : 336 – 338 .

- Jones , C. and Watkins , C. 1996 . Urban regeneration and sustainable markets . Urban Studies , 33 ( 7 ) : 1129 – 1140 .

- Lees , L. 2003 . “ Visions of ‘urban renaissance’. The Urban Task Force report and the Urban White Paper ” . In Urban Renaissance? New Labour Community and Urban Policy , Edited by: Imrie , R. and Raco , M. 61 – 82 . Bristol : Policy Press .

- Lever , W. F. 1993 . Reurbanisation—The policy implications . Urban Studies , 30 ( 2 ) : 267 – 284 .

- Liverpool City Council . 1987 . Liverpool City Centre Strategy Review , Liverpool : Liverpool City Council .

- Liverpool City Council . 2005 . New Housing Development, Supplementary Planning Document , Liverpool : Liverpool City Council .

- Liverpool City Council . 2007 . Ward Profile: Central Ward , Liverpool : Liverpool City Council .

- Liverpool Vision . 2001 . City Centre Living Forum: Report to Liverpool Vision , Liverpool : Liverpool Vision .

- Madden , M. , Popplewell , V. and Wray , I. 2001 . City Centre Living as a Spring Board for Regeneration? Some Lessons from Liverpool Department of Civic Design Working Paper 59, University of Liverpool, UK

- Nathan , M. and Urwin , C. 2006 . City People: City Centre Living in the UK , London : Institute for Public Policy Research .

- Office of the Deputy Prime Minister . 2003 . Sustainable Communities in the Northwest: Building for the Future , London : Office of the Deputy Prime Minister .

- Office of the Deputy Prime Minister . 2006 . State of the English Cities , London : Office of the Deputy Prime Minister .

- Pion Economics . 2006 . Liverpool City Centre—Foundations for Growth , Salford : Pion .

- Seo , J. K. 2002 . Reurbanisation in regenerated areas of Manchester and Glasgow: New residents and the problems of sustainability . Cities , 19 ( 2 ) : 113 – 121 .

- Tallon , A. R. and Bromley , R. D. F. 2004 . Exploring the attractions of city centre living: Evidence and policy implications in British cities . Geoforum , 35 ( 6 ) : 771 – 787 .

- University of Nottingham Survey Unit . 2007 . City Centre Living Survey, 2006 , Nottingham : Nottingham City Council .

- Unsworth , R. 2007 . City living and sustainable development . Town Planning Review , 78 ( 6 ) : 725 – 747 .

- Urban Task Force . 1999 . Towards an Urban Renaissance , London : Spon .

- van den Berg , L. and Klassen , L. H. 1987 . “ The contagiousness of urban decline ” . In Spatial Cycles , Edited by: van den Berg , L. Aldershot : Gower .