ABSTRACT

The significant predicament of sustainable urbanism in contemporary cities of the Gulf region is being addressed by developing policies designed to make cities safe, inclusive, resilient and sustainable. By examining the accessible planning documents, and based on the analysis of the ongoing world-class developments and megaprojects within the Gulf cities, particularly in Doha and Dubai, we argue that there is an inconsistency between the master-planning phase, usually conducted by western consultants, and the economic, political, socio-cultural, and environmental dynamics of the Gulf. Our analysis revealed insensitivity to the local, economic and socio-cultural patterns of the Arab Gulf countries and a governmental lack of capacity of national planners that may erode the opportunities to implement sustainable urbanism. It is suggested that, although globalization and modernization may have brought some benefits to the Gulf cities such as improvement in living standards and changes in society and lifestyles, yet an innovative master planning that merges land use and strategic planning based on building national capacities, and a holistic understanding of the social, cultural and oil-dominated economies and community engagement, is essential to deliver sustainable urbanism in the region. Recommendations for moving towards more capable, participatory and sustainable planning system are suggested in the paper.

Introduction

Place imagery and the urban environment have always been significantly influenced by urban planners. In fact, there has always been a direct correlation between traditional planning and its impact on the attractiveness of a place as a potential source of social and capital investments. Urban planners are typically involved in the promotion of a destination for urban development through the narratives or visualizations of a destination. As such, they formulate official plans, which have a pronounced effect on policy-making decisions (Zaidan and Abulibdeh, Citation2019). An increasing number of cities are developing thorough urban redevelopment plans and city enhancement programs. The main aim of these schemes is ‘rebranding’ and establishing a new image of the city to sell it (Zaidan, Citation2016). With respect to selling and characterizing a city, urban imagery underscores the perceptions of the city to outsiders and, at the same time, to its inhabitants, with regard to their tangible and intangible traits, which are central to the foundation of cultural planning (Stephenson, Citation2013). Urban imagery emphasizes these traits, which correspond to the symbols illustrated in the tangible and intangible aspects of the city, such as monuments, buildings, and roads, habits, institutions, and stereotypes related to the attitudes of residents, among other factors (Hague and Jenkins, Citation2004). These traits need to be clearly illuminated to prospective investors, tourists, and local inhabitants (Stephenson, Citation2013).

The manner in which modernism, postmodernism and globalization have influenced the urban environment in several cities of developing and developed nations is highly important in the urban and cultural trends in planning. The transformation to the global economy contributed to several changes in the form of the advent of a global division of labor, increasing mobile capital, and an abonnement of the traditional nation-state role (Crook et al., Citation1992). Consequently, these transformations have given rise to the adoption of a competitive economic identity by numerous cities. For example, London, Toronto, Tokyo and New York have established a strong image of epicenters of power with respect to global urban networks of financial, communicational and informational flows. These international cities share more common features with each other compared to nearby cities and surrounding regions (Stephenson, Citation2013). However, attention to the idea of urban sustainability and sustainable development, has only recently featured within urban planning and development (Abulibdeh et al., Citation2015a). Cities, as industrial nodes and as densely populated areas, have historically been depicted as mutually incompatible to sustainability (Grander, Citation2014). Although sustainable development is a somewhat new paradigmatic force, the idea that metropolitan areas are in some respects problematic or unsuited spaces for human inhabitation has a more extensive and eventful history in both Middle Eastern and European traditions.

On the other hand, in the case of globalization and growth in urban and regional destination competitiveness, the integration of culture in development planning is becoming increasingly more important. The growing homogeneity between landscapes and societies is one impact of globalization (Zaidan, Citation2016). In the current age of global travel, and the growth in cross-border economics, technological, and socio-cultural exchanges, several scholars have assumed that globalization and the ‘linking of localities’ would simply result in the rapid homogenization of urban society, culture, and landscapes (Chang, Citation1999). However, a new shift in scholarly thinking has questioned these past assumptions. Instead of encouraging homogeneity in terms of socio-cultural characteristics, academics are identifying that globalization is also playing a hand in creating significant localizing effects on place (Abulibdeh, Citation2018a). While many communities have lost, or are in the process of losing their uniqueness, having been ‘transformed into standardized morphing of architecture, land-uses, and repetitive rhythms and flows of people,’ many others are increasingly reasserting local distinctiveness as a social and economic response to globalization. The powerful appeal of place distinctiveness as a reaction to globalization is at the heart of the concept of ‘globalization’ (Swyngedouw and Baetan, Citation2001).

Since one of the traditional challenges and objectives of professional planning is to preserve or enhance a place’s character through its pre-existing environment, planners must utilize a variety of concepts to define and describe place. Often appropriated from other disciplines and used in generalized ways, concepts such as a ‘sense of place,’ and ‘genius loci,’ are referred to extensively in urban planning, with the aim being to enhance the unique and attractive views of place within cities (Zaidan, Citation2016). In the modern day and age, the identity and image of a city are key areas of focus for experts involved in urban planning. It is extremely important to establish an emotional attachment between the city and its local inhabitants and businesses operating in the area (termed civic pride), and to attract external interests and investments. Branding and integrating culture into development and urban planning are crucial for successfully marketing a city to local inhabitants and people abroad in order to produce a sense of place identity (Hague and Jenkins, Citation2004; Abulibdeh and Zaidan, Citation2017). Consequently, the challenges for experts involved in the urban planning space are to determine how to make the effects of globalization present in the whole city without causing detriment to its unique identity.

The high rate of urban growth and immigration has considerably altered the structure of the Gulf nations, transforming them into large laboratories in which urban development-related phenomena that occurred over an extended period in modernized Western cities have been replicated over a short period of time. The impact of concentrated development spatiotemporally and globalization has prevailed and is witnessed in many cities in the Gulf region, particularly in Dubai, in the form of multiculturalism, immense conurbations surrounded by urban sprawl, gentrification, extremes of wealth and poverty, and gated and guarded communities. In a historical sense, and owing merely to the immense rapidity of the transformation, this phenomenon was not experienced before and highlights the need for investigating the sustainability of such transformation. Bagaeen (Citation2007, pp. 174) introduced the term ‘instant urbanism’ with the aim to distinguish what has taken place in the Gulf region from the continuing urban transformation that occurred through a long-term process in the West. In several respects, academics remain in the initial phases of investigating, analyzing, and comprehending what has happened. Our analysis will closely examine the rhetorical underpinnings of eco-friendly large-scale projects in an attempt to discuss implicit and explicit goals.

By examining the accessible planning documents, and based on the analysis of the ongoing world-class developments and megaprojects within the Gulf cities, particularly in Dubai, and to a lesser extent in Doha, the paper aims at analyzing the numerous ambitious efforts being exerted to manage the rapid urban development and the challenges and opportunities associated with urban planning and the ability of the Gulf region to deliver sustainable urbanism.

Planning for Sustainability in the Absence of Democratic Politics in the Evolving Gulf City: Lost Meaning and Opportunity

Besides the visual transformation and the transition of the cities in the Gulf region, the most notable transformation experienced by these cities is the demographic transformation and change, which has occurred due to the mass influx of expat workers that have been attracted to these cities due to their economic prosperity and growth. The human resources landscape can approximately be described as follows (Nagy, Citation2006; Rizzo, Citation2013): inexpensive labor, originating from South Asia (primarily Pakistan, Bangladesh, and India), has been involved in the infrastructure and construction sector, which is highly dependent on manual labor. On the other hand, expats from Southeast Asia (primarily from Indonesia and Philippines) work in the lower service industry. Middle Eastern and North African expats worked mainly in the education and the public sectors, while expats who possess tertiary education from Western countries have provided expertise in high professional consultancy services for designing, constructing, and the handling of the recently built, or future build state-of-the-art-infrastructure. Consequently, due to these demographic patterns, the Gulf region possesses an ethnically diverse population, mainly comprised of temporary laborers (Nagy, Citation2006) which, in the context of UAE and Qatar, exceed locals 5 to 1.

In the 1970s, in particular, countries in the Gulf region were characterized by a swift growth in the rate of urban population. The foundation for this demographic change was the import of technology from western countries with the aim to acquire immediate, major changes (Abulibdeh et al., Citation2019a). Adequacy, speed and quantity functioned as the primary parameter, and a relative transitional period was avoided. However, when we closely study past events we can conclude that this transformational period has enabled cultures and their values to evolve, expand, and protect their particular identity (Zaidan, Citation2019a; Zaidan, Citation2019b). The consequence has been modern built-up structures constructed based on international designs centered in an essentially traditional environment, with the aid of the latest technology. In cities of the Gulf States, and to a larger extent the cities of the Middle East, most of the traditional architectures are being limited. This is due to the perception that the symbolic, cultural, and economic patterns are second to the modern way of life patterns and notion of allocating space, which display their depiction of knowledge and technology, and new policies and strategies of urban management cut-off from human scale and native natural city fabrics.

In the Gulf nations, according to Grander (Citation2014), the rapid development of the urban landscape and the vast supply of wealth streaming through the GCC have continuously increased the size of the typical aspect of development in the urban sector. While there is continued planning and construction of hotels, buildings, parks and mosques, increasingly larger areas are being integrated into this super-modernist and highly planned spatial discourse. According to Zaidan and Abulibdeh (Citation2019), cities that once changed to the melodies of an inner tune that molded their designs are now destroyed, disembowelled, or have surrendered to the development systems and demands of transport, which assign very limited attention to human scale and the urban landscape. Native identity and culture are considered as part, but not essential, in the design process of architects planning buildings and public spaces in the cities of the Gulf region, partly due to a belief that Middle East local culture, traditions, and economic patterns are inferior to their ‘modern’ Western counterparts. The planning and allocation of living spaces, which are part of the policies of urban management, manifest an incongruity in architecture due to global style, technology, and architecture designed around traditions, identity and culture. Cities, which were formerly regarded as embodiments of rich culture and heritage, have currently been diminished to industrialized urban sites, which overlook the importance of the balance between the urban landscape and development needs. Moreover, cities founded on public cities and communal spaces that housed culture-centric buildings, have currently been superseded by newer ‘car cities,’ in which the inhabitants depend on the latest traffic management systems and roads.

The Politics of Megaprojects in the Gulf Region: Modernity for Improving the City’s Comparative Edge

In recent years, governments in the Gulf countries have carried out numerous megaprojects, which have enabled the provision of modern urban amenities and more tourism (Rizzo, Citation2013, p. 540). Megaprojects are continuously provided by government-linked companies for the purpose of branding cities and improving their competitive advantage over other Gulf cities as well as other globally important cities. However, the execution of such immense megaprojects without the guidance of a national planning framework has given rise to urban preeminence (Rizzo, Citation2013) and hence to increased congestion in traffic, affordable housing shortages, localized environment effects, and real estate inflation (Al Buainain, Citation1999, p. 406). The luxurious lifestyles of the citizens of the Gulf countries have been subsidized by the ruling states in these cities, with the aim being to secure political backing. Consequently, the implementation of these policies resulted in increasing the urban sprawl (due to the allocation of vast amounts of land to citizens to design and construct segregated houses). Furthermore, these policies have increased road and traffic congestion (due to the high number of vehicle ownership as well as subsidizing fuel prices) (Abulibdeh and Zaidan, Citation2018; Abulibdeh et al., Citation2015b). Finally, imposing these policies has resulted in irresponsible consumption of electricity and water (electricity and water are free of charge to citizens in certain countries such as Qatar, while in other Gulf countries it is supplied at discounted rates) (see Abulibdeh and Zaidan, Citation2020; Rizzo, Citation2013, p. 14). In light of these well managed and controlled conditions, the citizens of the Gulf region are less likely to be inclined towards pushing the authorities to impose more sustainable initiatives. The governance structure is designed so that the change may only be implemented from the top, and when this does occur it is typically faced with resistance from government authorities that do not possess any incentive or capability (Spiess, 2008, p. 245) to implement what is being asked of them. The Gulf region appears to lack conscious and engaged users/residents, who are required for even the most advanced eco-friendly technologies to be effective and successful (Crot, 2013, p. 2821).

Other academics have pointed out that the failure to achieve the goals of sustainability is inherent to the organizational flaws of Arab nations in the Gulf region. For instance, Ponzini and Nastasi (Citation2011) claim that the absence of segregation between private and public stakeholders in Abu Dhabi hinders any effective dialogue regarding the suitability of state-sponsored megaprojects. Ponzini and Nastasi (Citation2011) studied the Abu Dhabi 2030 Urban Structure Plan and identified that developers are not bound by formal obligations and they are allowed to discuss the best offers with the Urban Planning Council. Moreover, Rizzo (Citation2013) states that the absence of a thorough planning framework in Doha has given rise to fragmentation in the city, resulting in significant variations in real estate values that place the neglected inhabitants to forgotten corners of the urban sites. Rizzo (Citation2013) studied the Msheireb renovation project and demonstrated that while the redevelopment project may entice locals and expats, its execution has directly contributed to the displacement of the previous inhabitants (primarily from Asian countries) to the outskirts of the urban-scape, resulting in a gentrification phenomenon which poses a threat to the complexity of the city center (Rizzo, Citation2013, p. 539).

Through a qualitative study of the official planning documents, certain stimulating features of the development projects (mega-projects) are revealed. The majority of mediatized spectacular megaprojects are described as elements of the vision of their cities’ governors (refer to the websites and brochures of the GCC׳s megaprojects). This particular politico-economic system has privileged a development mode based on creating iconic megaprojects as foundations for a claim to global-city status, in line with the image of megaprojects as ‘vehicles for cities’ revitalization and attraction’. Nonetheless, the language communicated in such large-scale projects demonstrates a limited understanding of the vernacular architecture of the Gulf region. In reality, urban and building form is managed by international firms that are highly insensitive to the native culture. The sheer scale of the projects provides another added benefit to the reputation of the leader. This strategy bears a long historical tradition and is clearly designed to rival other large-scale projects in Asia (most prominently those in Singapore, Malaysia, and China). illustrates the classification of major planned cities in the Gulf Region. The figure indicates that the vast majority of development may be classified as signifying an infrastructure improvement in cities with contemporary infrastructure. However, the low-carbon and carbon-neutral cities (Musheireb in Doha, Masdar in Abu Dhabi, and Education City in Doha) resemble theme cities with limited accessibility.

Figure 1. Classification of major planned cities in the Gulf Region (Al-Saidi and Zaidan, Citation2021)

The New “eco-cities” of the Gulf Region: Between Corporate Interests and True Innovation

There is an increased enrollment of GCC major cities in the competition of world cities through records and spectacle, despite the absence of local expertize. Gulf cities are also challenged by the cultural and geographical contexts of GCC. Previous studies show that local contexts can affect architectural and design practice; therefore, contextualizing the design within local environments, though crucial, yet is a difficult task. Through the investigation of the official planning documents, there is an invoke general references and norms, such as ‘international norms’ and ‘best practices’. Given the context constraints, the proposed solutions and ideas are limited to broad and general matters. It is argued that international mobile experts have insufficient time to conduct feasibility studies to examine local conditions and the related constraints. The major challenges of firms is to deliver what the client wants on time and leave no space for conducting preliminary studies that are related to socio-cultural or feasibility aspects. Conversely, there is a need for a holistic approach towards the effective management of sustainability issues, from supply-side green technologies to demand-side utilization patterns, air to land and water, and urban to rural. The Gulf countries need to shift towards effective engagement considering the global sustainability agenda by going beyond mere reporting and official reference of the current national visons of the sustainability agenda. Playing a significant role and effective engagement entails more robust and efficient forms of action via participating in the international strategies and the development of workable and cohesive national strategies, and is required to address the major challenges to sustainability. These integrated national strategies include, but are not limited to, food security plans, sustainable transportation strategies, risk management and resilience strategies, biodiversity and ecosystem management and preservation strategies, climate change strategies, laws on renewable energy resources, and integrated water management strategies and water laws (Zaidan et al., Citation2019; Hawas et al., Citation2016). Effective engagement also requires a deeper integration between the issues and future policies and institutional arrangements. The one-dimensional nature of the Gulf countries’ development policies has indicated that one cannot segregate water desalination from its growing energy footprint, coastal development from its impact on marine organisms and the tourism industry, urban planning from climate change, global warming, and air pollution effects, or food security from groundwater considerations. Policymakers and decision-makers in the Gulf region are gradually becoming conscious of such interconnections and of the significance of and need for distinct national strategies and frameworks for collaboration on the regional level. A highly relevant and key measure that needs to be taken into consideration in order to strengthen these initiatives towards policy amalgamation and integration is the attention to the financing component needed to improve sustainable development. While financing is not the main issue for Gulf region countries states in relation to other countries nearby, the ‘greening’ of these plentiful financial resources and their diversion from traditional investments to sustainable ones that also consider climate change concerns remain an issue of high importance (Alsaidi et al., Citation2019).

On the other hand, Elsheshtawy suggests it is crucial that planners perceive people living in the Gulf simply as ‘passive consumers following the dictates of global capitalism’ (Elsheshtawy Citation2008, p. 968). He also highlights the evolution of ‘transitory sites’ (e.g. tourist-centric projects and green spaces.) as controversial spaces of ethnic prohibiting (Elsheshtawy, Citation2018). However, Rizzo and Glasson (Citation2011) made a case for the possibility of a more inclusive model in their studies regarding large-scale projects and urbanization in Singapore and Malaysia. They argued that such an inclusive societal model would make the most of the modern Gulf’s rich ethnic diversity, as opposed to directly addressing the social norms practiced in such transitional spaces.

The responsibilities of Gulf countries towards sustainable development are not completely consistent with the principles of environmental preservation and proper usage of natural resources. Furthermore, they stem from further responsibilities such as enhancing the competences of marginalized or underrepresented groups, sustaining the contemporary high-quality essential services, and actively participating in the global sustainability agenda. Coupled with the high rate of urbanization and demographic growth and economic prosperity patterns, staying ahead of the demands for essential services in the arid and semi-arid climate of the Gulf region has been an extremely challenging task. For example, the growing demand for electricity may increase even further due to the impact of climate change, as most energy consumption in the Gulf countries is composed of operating air conditioning units and running desalination processes to produce clean water. Considering these national sustainability challenges, the Gulf countries have commenced certain initiatives to alter the urban landscape and implement competent technologies, such as renewable energy, aiming to initiate an ecological modernization process and, simultaneously, achieve the aims and objectives of the global sustainability agenda, such as the 2015 Paris Agreement (Al-Saidi et al., Citation2019). In addition, Zaidan et al. (Citation2019) indicated the Gulf countries have lately demonstrated rapid active involvement towards the global sustainability agenda by implementing more policies, re-modifying certain strategies to global goals (particularly the urban environment and the utilization of renewable energy resources), and joining global organizations.

On the other hand, the significant dilemma of sustainable urbanism in contemporary cities of the Gulf region is illumined by difficult task of tackling sustainable urbanization in the Gulf countries to make cities safe, comprehensive, resilient and sustainable. While encouraging the needs of sustainability in urban areas, which contain more than 90% of the residences of the Gulf region, several local development plans have concentrated measures around the economic and social diversification of the urbanization process, along with schemes dedicated to native innovation, resilience and inclusivity. However, a significant number of urban environments in Gulf urban areas are still unsustainable mainly due to urban growth and development that is centered around ‘trophy architecture’ (Grander, Citation2014, p. 350). However, under the impact of an oil-driven economy and the rapid rate of change, locals in the Gulf countries are becoming more vigilant towards efforts to safeguard, represent and develop a unique ‘national’ culture and heritage. According to Picton (Citation2010), concerns relating to ‘loss’ of identity and problems surrounding ‘global’ culture are potent social factors that can have a detrimental effect on such efforts. The development of ‘Heritage Villages’ in nearly every city has become a key sign that heritage revival has transformed into a significant political, cultural and social process in the Arabian Gulf (Picton, Citation2010). In an effort to rebrand themselves into international urban hosting centers, several cities within the Gulf region embraced a paradigm of development that suggests a rejuvenation and interconnection between globalization, heritage and tourism – a kind of ‘cosmopolitan heritage industry.’ In this regard, the implementation of ‘tradition’ is presented as a dynamic counteracting measure to hegemonic globalization. However, this process, ‘far from being a type of resistance to globalization, is explicitly its typical consequence’ (Melotti, Citation2014, p. 75). Several scholars have investigated the concepts of heritage restoration and the preservation, representation and construction of culture in the Gulf region. These scholars arrived at the conclusion that heritage revival in the Gulf cities is both a symbolic and practical antithesis of globalization (Picton, Citation2010). Heritage revival is also an increasingly strong indication of the rapid rate of development of international business and tourism in these countries, which is the primary aim of economic diversification.

It is clear that the Gulf countries are engaged in efforts to reinforce the top-down system of political power and fuel the exchange of wealth through the development of the urban sector. Discourse of master planning in the Gulf region contributes to the formation of an urban form that differs considerably from the models and best practices that have amassed over a long period of conversation about sustainable development and sustainability with respect to the urban environment. In particular, we will argue that the super-modernism, which stems from urban master planning in the Gulf cities, is consigned to a spatial discourse that is contradictory to its effective execution (Grander, Citation2014). A typical modern house in the Gulf cities is encircled by high walls, which marks the boundaries of the estate and provides a culturally standard level of privacy to members of the household. The private spaces situated within the confines of the walls are usually highly manicured, well-maintained and remarkably green. This well-maintained and highly embellished private space bears a stark contrast with the interstitial land between and beyond the surrounding walls. From a pleasant view anywhere in the suburban areas of Doha and Dubai, for example, an odd combination of elements can clearly be observed. This strange combination of elements consists of high walls, which block the view to the private space from outside, and lofty mansions that peer over the surrounding walls and disorderly interstitial space that covers the gaps between and beyond these omnipresent walls (Grander, Citation2014; Zaidan et al., Citation2019).

In moving from these disorderly and redundant interstitial spaces to the personal living spaces of the family estate, one crosses over the unique boundary between order and disorder. This stark difference is not allocated to the residential level. For instance, Aspire Park in Doha, is a collection of parkland, stadiums and athletic amenities constructed to host the 2006 Asian Games. This well-maintained, modernistic space is in close proximity to two vast shopping malls. Currently, it operates as a park open to the public and is maintained by a small staff of South Asian caretakers, guards and gardeners (Grander, Citation2014). Humans struggle to utilize the meticulously planned spaces and pedestrian streets that systematically link the different amenities of the park. They are overshadowed by the surroundings, and even when people are moving around in the park, it feels nearly empty. Indeed, the unique boundary one faces when entering a walled private property is reproduced at this super-modern level: at the interstices of the immense planned development.

The highly modern compartmentalization of urban development in Gulf cities, particularly Doha and Dubai, function as the main backbone for urban sustainability. Moreover, the Gulf countries are experiencing a technology-driven transformation towards a low-carbon and energy-efficient built environment. Many regional efforts have been invested in order to adopt renewables, encourage the transition to low carbon communities and the establishment of smart cities (e.g. Lusail city in Qatar or Masdar city in the United Arab Emirates) (Rizzo, Citation2017; Zaidan et al., Citation2019). However, other notable examples include Education City (established and operated by Qatar Foundation), the host venue of the UN Climate Change Conference by, which aims to provide leadership in energy and environmental design (LEED) and houses foreign university branches of various prestigious educational institutions from the US (Rizzo, Citation2013, p. 541).

Regarding the efforts to achieve urban sustainability, being the region’s first significant effort to construct a ‘sustainable’ city, Masdar City in the UAE is a prime example of the vast amount of capital certain nations possess and have dedicated to the type of sustainable goals, which is beyond the capabilities of less financially equipped cities, specifically via the use of a cluster of technologies aiming for net-zero carbon output (Grander, Citation2014). At present, Qatar has formulated plans for an ‘Energy City,’ which will utilize the latest eco-friendly technology, focus significantly on solar energy and function in a manner to enhance air and water quality while ensuring a reduction in the waste stream (Abulibdeh et al., Citation2019b). This is in addition to the renovation of Msheireb, apparently ordered by Sheikha Moza, with the goal of fostering and signifying the architectural history of Qatar and rediscovering a distinct type of Qatari urban development, which strikes a balance between modern, innovative developments and local culture and heritage. These development projects interconnect with the political economy of development in urban areas, as their construction and continued maintenance depend on the foreign workforce, which functions as a conduit for the transfer of wealth from state to citizenry. In addition, super modern developments in urban living spaces evidently present the top-down setup of political power in the Gulf countries – even when the projects are not directly carried out by the country, the land allocation and permits for developments of this sheer size need intricate links with the top strata of the Gulf nations. However, the concern here lies in the product of this system and, in particular, in the incompatible nature present between urban supermodernism and sustainability (Grander, Citation2014). Two important and interconnected flaws are suggested here, exclusive to the spatial discourse indicated by these plans and projects. Firstly, descriptions of Masdar City footnote, which states that approximately 40,000 to 60,000 workers will travel for work on a daily basis to the planned city. In most of the Gulf countries, these super modern projects and immense spaces are the visible stage showcased to the international audience.

Furthermore, Gardner (Citation2014) argues that supermodernism partly relates to the extensive size of these constructions, a spatial discourse in which completely new planned communities, distinct ‘cities’, islands and other large planned spaces emerge in the city, as well as the surrounding areas. For instance, in Doha, the Pearl project is a commercial and residential development that close resort. Located just north of the city, the development is built on a 14 square kilometer artificial island and is purpose-built to house about 40,000 residents through a mixture of tall apartment buildings and private villas. The Pearl houses numerous eateries, premium hotels, a marina, commercial sites and, perhaps most controversially, a mere four lanes of road linking it with the mainland. Likewise, ‘Education City’ is a large campus that is home to various high-end universities from the US and other educational organizations located in what is presently the fringe of urban Doha.

Other scholars such as Al-Ammari and Romanowski (Citation2016, p. 1537) argue that globalization and modernization may have aided the Gulf countries, Qatar, for example stating ‘these benefits include a significant overhaul of the education system, access to high-quality education (…), an improvement in living standards, enhanced transportation, opportunities in the financial sector and changes in society and lifestyles.’ The Qatari family resides between the poles of the tribe, the conjugal family, the housekeeping workers, and the variations in culture (Kassem & Al-Muftah, Citation2016). Looking to the future, it is argued that ‘Qatar needs to address the issue of aligning Arabian Gulf expectations, traditions, and norms with those of knowledge economies’ (Wiseman et al., Citation2014). Furthermore, to develop a knowledge society while ensuring that the local culture and traditions are not compromised (GSDP, Citation2008), Qatar may need to transform into a place of varied dimensions. The prime location that the capital city of Doha describes is as follows, ‘many parts of the city resemble a surreal and incongruent mixture of Hong Kong, on the one hand and Tucson, Arizona, on the other’ (Kamrava, Citation2015, p. 5–6). While one end of Doha is dominated by huge skyscrapers with distinctive designs, the traditional outlook is preserved in other parts of the capital city (Zaidan and Abulibdeh, Citation2018). In addition, certain structures have been renovated using the original design. Located at the Corniche, the West Bay of Doha, features a futuristic look amplified by the switching of the numerous colorful lights at night (Zaidan & Abulibdeh, Citation2019). In contrast Souq Waqif, located on the other side of the Corniche, is a traditional Arab market that attracts tourists and locals coming to socialize and shop.

An effective and worthwhile approach to sustainability suggested in this current paper is to include initiatives for curbing urban sprawl and, ultimately, moving away from a growth-driven economy. However, through the brief assessment of the political economy of urban growth in the Gulf countries, Grander (Citation2014) suggested that the model of urban growth in Qatar displays an evidently unsustainable economic and socio-political approach for the foreseeable future. This model, while publicly conceptualized as simply the route to a swiftly nearing terminal stage (the reduction in hydrocarbon reserves and a diversified socio-economic future to address that reality), and now encouraged in the whole discussion of sustainable development, has become heavily interconnected with the social and cultural fabric of the modern Gulf country. The expectations of state citizens, their notions of entitlement and the naturally rapid rate of growth in the region, only further aggravates the situation. Curbing urban growth will compromise one of the two key channels through which wealth is moved from state to citizen, and political stability within the region partly depends on the legitimacy created by these transfers. Thus, a prospective threat to political stability in the Gulf could be posed via the implementation of a more sustainable model of urban growth.

In the background, however, lie the support industries, service facilities and labor camps that accommodate the huge workforce. In Doha, for example, the South Asian laborers who construct, clean, maintain and serve the different super modern projects and urban sites in the capital city usually live in the Industrial Area, a tough and expansive network of industry and labor camps located on the city outskirts. Similar places can be found in the majority of the Gulf cities and plans for substantial ‘Bachelor Cities’ are abundant in planning contingents present in all of the Gulf countries (Zaidan et al., Citation2019; Grander, 14). This background activity is crucial to the daily function of the Gulf city. It opposes the detached and compartmentalized design of these super modern spaces, and in this context questions the logic of Masdar City’s claim towards sustainability in terms of the manner in which a discrete and bounded ‘sustainable city’ can compensate for the impact of the labor force that passes through the background/center stage divide on a daily basis.

Urban Planning and Development in Post-Colonial Dubai: The Modernization and Stagnation Phases

Dubai has formed an image for itself as the most audacious of the Gulf cities primarily due to its numerous megaprojects (Koolhaas et al., Citation2017; Rizzo, Citation2013; Zaidan, Citation2015). Some of these megaprojects include the Internet City (inaugurated in 2000), which was one of the initial large-scale projects to be executed, with the goal of transforming the urban area into a hotspot for Internet and Communication Technology firms. Another megaproject is Media City (inaugurated in 2001), a place which houses such organizations as Forbes, CNN, Sony Pictures and the BBC. Furthermore, there is also Festival City, which is a large commercial, residential and entertainment park, covering an area of around 526 hectares. The prominent Dubai Marina is a multi-use, waterfront place, which includes major housing projects and hotels. Palm Jumeirah (inaugurated in 2007) is a 1.5 billion USD artificial island for exclusive hotels, residences, and entertainment amenities. The Burj Khalifa (opened in 2010) and Dubai Mall Complex (Opened in 2008) is a multi-use commercial area housing the tallest building and the largest mall in the world. Finally, Dubai World Central (inaugurated in 2010) is an airport city that will also accommodate the pavilions for the 2020 Expo (postponed to 2021 due to COVID 19 crisis).

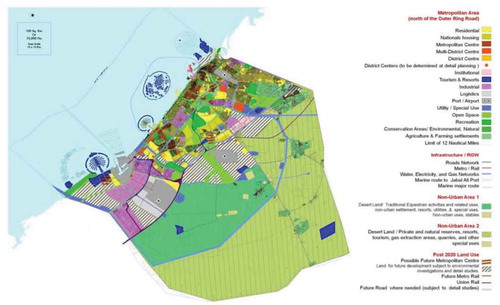

Dubai Master Plan 2020 (see ) is based on the vision of Shaikh Mohammed Bin Rashid Al-Maktoum, the Ruler of Dubai. This Master Plan has progressed through different phases, from reviewing and analyzing the existing situation covering aspects such as population and demographics, natural and man-made environments, socio-economic, and socio-cultural, etc., to perspectives of urbanization, development, and predicting the future urban expansion, to spatial structure, and lastly, developing legislative implementation tools. The vision of Dubai as a vibrant regional gateway to the world and a modern Arab city were the key elements underpinning the plan. During the past seven decades, Dubai has witnessed a rapid growth of its population, expanding from a small town of 20 thousands residents to 3 million residents, while urbanization in the city extended 400 times to include 1,309 high-rise buildings within 3,885 sq. km of land.

It is evident that the replication of Dubai’s successful approach to branding through its large-scale projects has become crucial for other small GCC emirates as seek measures to cement both their survival and autonomy in light of internal and external threats. However, with an emphasis on growing the tourism sector, limited attention has been devoted to development of the community in Dubai. For example, public amenities and open spaces are often crowded with buildings because, unlike the public amenities and open spaces, these buildings generate higher profits for developers (Zaidan, Citation2016; Zaidan et al., Citation2019). Jumeirah Beach Residence (JBR) is an example, which has a low number of open spaces and roads with a lower traffic capacity than required by the population size.

The Lagoon in Dubai, a mega development project, is another example of inadequate public facilities and open spaces developed in exchange for greater capital profits. The Lagoons were planned with the intent to create luxury destinations for private and public use, centering on seven ‘pearl’ islands. For it to be profitable, the number of plots sold had to be increased, thus reducing the size of each plot dedicated to a high-rise building. This resulted in three issues: a) less efficient building footprints, b) an increased level of podiums and basements, and c) lower-quality plots for open spaces and public facilities. It also resulted in an increased gross floor area (GFA), adding to infrastructure demands, such as traffic and services (Ogaily, Citation2015).

A number of different and often counterproductive strategies have been utilized to confront these challenges, confirming the confusion stemming from the incorporation of contemporary technology into traditional culture (Zaidan et al., Citation2019). An example of the issues related to this type of strategy is that it overlooks the traditions and enforces a global, more generalized form of architecture with the primary goal to demonstrate growth, stature, and progress. This strategy has contributed to the emergence of structures suitable to environments outside of Dubai that follow architectural designs but neglect the environment where the buildings are located (Hazime, Citation2011). This architectural style paves the way for an extremely compartmentalized and industrialized landscape that contains an extremely limited number of elements that embody the national identity, culture, spirit, and traditions. An opposing strategy would be to assign a greater amount of attention to the past and replicate structures that display the rich heritage of Islamic architecture. Architects used superficial features and designs, such as the dome or arches, to portray the Islamic identity in an effort to make a constructed building reflect the culture and heritage of the city rather than foreign. However, in reality, these structures owe their existence more to the global style and technology than the local culture (Ogaily, Citation2015).

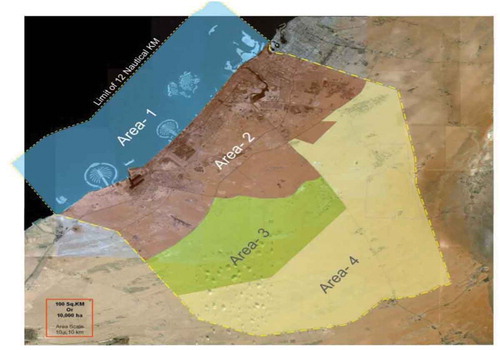

As shown in , Area 1 indicates the offshore islands that include sensitive environmental man-made islands for urban/resorts development and tourism. Area 2 indicates metropolitan areas (see ), where areas 1 and 2 indicate existing urban fabric, ongoing mega projects, on-hold or deferred mega projects to be developed beyond 2020. Area 3 indicates the non-urban area, for example the desert land including land used for equestrian and camel traditional sport activities and related uses, resorts, conversation areas, utilities, non-urban settlements, and special purposes, while Area 4 indicates non-urban areas, desert land including land-uses for resorts, gas extraction area, aquifer zone, farming settlements, utilities, and special uses. Similar to other cities along the Arabian Gulf, Dubai is also focused on the tallest, largest and biggest structures. Therefore, Dubai has developed in a linear pattern and the city that once was pedestrian-oriented, had neighborhood centers sprawled over large areas of land, has disappeared. Such strip development has also increased the car-dependency of residents, required to access daily needs, while walking and cycling are quite restricted (Abulibdeh, Citation2018b).

Skyscrapers have transformed into a suitable economic resolution to provide further room in densely populated old cities such as New York and Chicago, where these high-rise structures signify modernity, globalization, and prosperity and communicate a notion of pride and significant achievement as indicators of capitalist power (Zaidan, Citation2015; Ewers, Citation2016). Such high-rise skyscrapers buildings, including Emirates Towers and Burj Khalifa, are frequently found in Dubai and are perceived as monumental trademarks. However, presently the city skyline is ‘dispersed’ by the inclusion of several buildings of average height constructed next to other carefully planned and constructed high-rise buildings. In terms of urban population growth, it is clear that even a traditional urban form, where form identity stems from within the culture and region, satisfies the society’s requirement for taller buildings (Ogaily, Citation2015). Examples that still exist include the first tall structures from the 16th Century in the old Yemeni city of Shibam. Furthermore, identified among the most ancient World Heritage sites by UNESCO, ‘The Manhattan of the Desert’ can be viewed as a good example of sustainable planning and native building design in ancient tower houses. The success of this ancient UNESCO site is reflected in the current Al Badiya residential project in Dubai, which is being built based on design principles of Shibam. Before 2008, authorities designed plans to establish Xeritown in Dubai, which would have been the first city in the Gulf region to considerably reduce water consumption and implement technology to recycle industrial wastewater. However, the urban development project was discontinued in 2010 due to the dissolution of Tatweer, the main owner of the land on which Xeritown was to be constructed, because of Dubai’s financial woes (Bloch, Citation2010). After a recovery from the economic recession and following a successful bid for the 2020 World Expo, Dubai has instead constructed a new sustainable city built around the values of the ‘zero-net energy’ UC Davis West Village community in California. However, the idea of the eco-friendly city is not new, as it can be traced back to Richard Register and his work in the 1980s at Berkley.

The Dubai Master Plan 2020 recognized the appropriate urbanizations framework, urban fabric and form, development dramatization, and scale. The city is aiming to concentrate its target for achieving economic prosperity while, simultaneously, allowing opportunities for public and private investment to attain sustainable growth beyond 2020. As confirmed by Alraouf and Clarke (Citation2014, 318), several urban projects in the Gulf cities have incorporated the ‘Dubaization phenomenon’ in urban development. Indeed, the term ‘Dubaization’ or ‘Dubaification’ have recently been applied in academic literature to describe cities looking to compete with Dubai’s urban large-scale projects (Elsheshtawy, Citation2010, p. 250). According to Al-Zo’by (Citation2019), the rivalry among Gulf cities to mimic Dubai’s ‘success story’ with comparable development projects throughout the region has contributed to a plethora of construction, deconstruction and reconstruction of their identities leading to a homogeneity throughout the region in terms of iconic buildings and real estate marvels dominating cities. However, several experts suggest that the ‘Dubaization phenomenon’ as a platform of urban change and development, neglects and degrades the native, conventional and communal facet of culture. Al-Zo’by (Citation2019) states that the main issue lies not just within the lack of tradition and heritage within development models in the Gulf cities, but also the way in which this heritage discourse acts as a tool to bridge the gaps between cultural myths and manifestations of self-exoticism. Orientalist imaginative geography has usually been utilized as a self-eroticizing form of visual narratives for heritage artifacts, urban designs, and cultural aesthetics in the urban development of the Gulf region (Al-Zo’by, Citation2019).

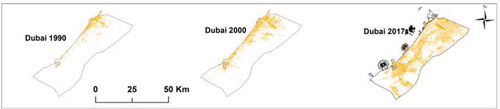

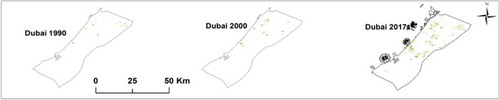

In the highly transformed city of Dubai, super modern spaces have increased rapidly over recent decades (see ). These super modern spaces include the ‘Internet City’, which serves the dual purpose of a free economic zone and an informational technology park; Media City, a tax-exempt area built to attract the media sector operating in the Gulf; Knowledge Village, a human resource management, higher learning and educational-free trade zone providing amenities for commercial training and educational institutions to function with full foreign ownership; International Humanitarian City, an independent-free zone authority dedicated to accommodate various global institutions devoted to the provision of humanitarian aid and international development. Elsewhere in the UAE, super modern projects such as the Masdar City Project in Abu Dhabi (a sustainable city designed to have a net-zero carbon footprint) have also emerged. These are a few examples that we suggest are characteristic of the spatial discourse imperative to development in the urban sector of the region – a spatial discourse that are following others, which, for example, Grander (Citation2014) refers to as supermodernism.

Figure 4. Built-up areas in Dubai (1990–2017) (Abulibdeh et al., Citation2019b)

Figure 5. Green areas in Dubai (1990–2017) (Abulibdeh et al., Citation2019b)

As noted, modernization is widespread in the Gulf cities, not only in Dubai. For example, ‘The Pearl’ in Qatar, an immense uniquely shaped artificial island, housing opulent residential spaces designed around the appearance of the French Riviera and the famous Italian City of Venice, mirrors Dubai’s ‘Palms Islands.’ Qatar has gained global prominence in various other ways such as by hosting global events, advocating for democratic reforms in regime-imprisoned Arab nations, financing development projects and even football teams in Western nations – but it is through constant competition with its neighboring countries to construct the most ambitious urban large-scale projects that it is seeking to make its built presence known (Rizzo, Citation2013). Furthermore, in its aim to become the world’s destination of choice and a cultural city, Dubai took the lead in the region by building skyscrapers that signify modernity and globalization and mirror the city’s economic growth (Ewers, Citation2016) and attract large numbers of residents and tourists. However, the level and pace of this population and economic growth has given rise to a variety of urban planning and environment related concerns (Mould, Citation2012). Hence, the question that remains is how Dubai can channel its growth ambitions and aspirations in order to transform regional and global urban planning decision-making into a role model for a city with an urban environment that successfully incorporates its culture and socioeconomic realities.

According to Stephenson (Citation2013, p. 286), the westernized approach to development in Dubai (See ), mainly featuring tourism development, may potentially lead to a considerable socio-cultural effect modified to fulfill the taste of tourists rather than those of the inhabitants. In the process, a socio-cultural issue is Dubai’s perceived absence of consistency with respect to its culture, primarily in the adoption of the old into the new. This position is evident in the lack of dedicated heritage resources and tourism industry organizations, in addition to limited public acknowledgment regarding the traditional and ethnic aspects of the indigenous society.

The emanation of high-rise developmental projects leads to the segregation of the population. While most expats (typically with small families or no family) live in clusters, such as Business Bay, Downtown, Dubai Marina, nationals (usually with bigger families) opt to live in conventional homes (Ogaily, Citation2015; Mould, Citation2012), which leads to residential clusters segregated based on socio-economic traits and urban establishments (Timothy, Citation2017). This is a significant problem that requires managing via urban planning that restricts segregation by putting emphasis on utilizing land for mixed development, regulating building heights, monitoring density, and integrating recreational and communal spaces for both locals and expats (Elessawy & Zaidan, Citation2014).

As mentioned earlier, successful megaprojects in Asian countries such as Singapore have transformed into models worthy of replicating by oil-rich Gulf rulers seeking ways for economic diversification and the modernization of their capital cities (Rizzo, Citation2013). Dubai has been viewed as leader of megaprojects; however, the Qatari capital of Doha has the capability to dethrone Dubai with respect to its goals for renewable energy resources, energy-efficient buildings, and knowledge production. The development of both Dubai and Doha landscapes are significantly influenced by megaprojects and mega-events, with Dubai hosting the World Expo 2020 and Qatar hosting the 2022 FIFA World Cup. Consequently, significant investments in infrastructure commenced, which are regarded as transformation catalysts, as they exert pressures to satisfy the expectations of the international audience on infrastructure along with environmental standards. In the context of several cities in the Gulf region, funding for these developments has mainly been supplied by the state via profits generated from their oil and gas resources. However, Dubai does not conform to this trend as it receives funding from its oil-rich neighbors (see Bloch, Citation2010). Moreover, although the benefits of large-scale projects are constantly met with criticism in the form of hindrance towards proper master-planning and boasting extravagance (Rizzo, Citation2017), they form a key element of the contest and rivalry in the Gulf region for symbolic dominance with respect to living standards, quality of life, and the nuances of the economic model. For instance, Qatar as an Islamic, moderate yet modern nation, compared to the UAE as a more westernized model. This rivalry can place the Gulf region at a crossroads, particularly following the fall-out of the economic relationship with Qatar instigated by Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, and the UAE in 2017. While it is still premature to assess the impact of this conflict on the future development of the Gulf region, it evidently damages the spirit of collaboration required to jointly address future environmental issues, which could push the economies of Gulf nations towards the verge of collapse.

The consequence goals of sustainability large-scale project in the Gulf is a state-sponsored and integrated urban development, distinguished by a certain concept (e.g. old Arab City, International City, Mediterranean Riviera City etc.) and an overriding purpose (e.g. commercial, sports, residential etc.). Evidently, the impact of state-funded development projects on such a level has been extensive, which has contributed to problems such as the deep fragmentation of the urban fabric of the city. Compared to the past, there are growing numbers of high-rise structures today, built solely with the purpose of maximizing profit for their developers. These structures incur damage to the city’s urban fabric, which is further aggravated by the developer’s emphasis on quantity over quality, especially with regard to land use (Zaidan et al., Citation2019).

Local academics have warned about the negative impact megaprojects may potentially have on the Gulf region’s Islamic heritage and identity. Riad (Citation1981, 7) was one of the first scholars to raise the alarm regarding an aggressive type of ‘Petro-Urbanism’ which, from his perspective, rapidly eroded the roots of an ecosystem that mirrored an effective acclimation to an environment spanning several generations. Similarly, while Al Buainain (Citation1999, p. 406) observes that Qatar’s ineffective multi-centric development is the reason contributing to a dire shortage of affordable residence, inflation in real estate, and localized environmental effects, Nagy (Citation2006) argues that a limited knowledge of budget limitations, the impacts of immigration, and native culture itself by global and local planners in Qatar are also some of the primary factors that have impeded the implementation of effective and meaningful urban planning.

Conclusion

The fast-paced urbanization of cities in the Gulf region poses challenges regarding conventional native city fabric and the rise of contemporary skyscrapers. It is crucial that project stakeholders consider the cultural principles, native environment, human scale, and the present historical urban fabric in their approach to satisfying project requirements, which primarily demand ‘iconic high-rise buildings,’ ignoring basic and fundamental conditions in producing sustainable building designs and comfortable spaces that can be utilized easily. Companies involved in development projects and construction rules and regulations should be mutually compatible with the requirements of the local community and society as a whole for intricately planned, comfortable urban spaces – balanced with economic advantages. High-rise buildings are not always the answer to the residential needs of locals, despite their integration in native culture. Land-use zoning and urban master plans need to be effectively employed to implement appropriate elements of sustainable cities such as open spaces and systematically and comfortably scaled structures. In addition, socially mixed development need to be taken into account to achieve the primary goal of encouraging harmony and peaceful coexistence between locals and expat residents.

The shift towards the extremes of urbanization in the Gulf region has contributed to design and cultural identity issues, along with threats associated with coastal management or natural hazards. However, simultaneously, it has placed the cities in the limelight with respect to global development, since they no longer function as spaces exclusively for settlement, production, and essential services. These cities now have a pronounced impact on political and social relations at all levels and have now become powerhouses of influence and politics, guiding the accomplishment of national visions and influencing policy outcomes. Managing the development of these cities also has a substantial impact on environmental and sustainability initiatives. The change of these cities with respect to sustainable living and eco-friendly design, symbolizing local cultures in place of westernization patterns, is an essential criterion for a shift towards sustainability in the Arab Gulf region.

The findings suggest that urban development in the Gulf countries has transformed into a key element of the implicit contract between the government and citizen. In its present structure, this system relies on the continuously growing presence and influx of foreigners to these countries. In other words, the increasing cluster of foreigners working to help and support the Gulf countries’ development collectively operates as the medium by which wealth is transferred from state to citizen. The most benefits are assigned to those citizens who operate at the largest scale with respect to urban development. The focal point of the argument, then, significantly alters the logic of this system in the sense that new social relations in the Gulf region are not shaped by urban development, but rather by the continuous representation of native social relations, which fuels urban development.

In this conclusion, we summarize the findings and emphasize the importance of the professional training and education of native planners as a key element of effective urban planning implementation across the Arabian Gulf.

It is suggested that urban development has become a crucial medium for the movement of government-controlled wealth to its citizenry, and that stalling urban development in the interests of long-term sustainability will likely be detrimental to the legitimacy built by the political leaders of the Gulf countries. Secondly, we maintain that the socio-political setup of the GCC countries poorly matches the essentially democratic assumptions enjoining both theory and practice in sustainability. Finally, the key question remains regarding how an effective and transformative type of sustainable development can be truly tailor-made for the urban environment. As demonstrated throughout this paper, the fundamental spatial discourse of urban development in the Gulf region creates extremely organized and managed spaces, but at the same time also contributes to the production of interstitial and fringe spaces of a remarkably contrasting character. The implementation of meaningful, significant and transformative sustainability would face considerable challenges in various socio-cultural contexts not only in the Gulf region. However, with a sizeable amount of capital at its disposal, the Gulf nations look to move quickly towards these expressed aims.

Acknowledgements

This publication was made possible by an NPRP award [NPRP11S-1228-170142] from the Qatar National Research Fund (a member of the Qatar Foundation). The statements made herein are the sole responsibility of the authors. Open Access funding provided by the Qatar National Library.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Abulibdeh, A. (2018a). Implementing congestion pricing policies in a MENA region City: Analysis of the impact on travel behaviour and equity. Cities, 74(3), 96–207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2017.12.003

- Abulibdeh, A. (2018b). Chapter 21: “Urban transportation and tourism in the MENA region.“ In D. J. Timothy (Ed.) Routledge Handbook on Tourism in the Middle East and North Africa. London: Routledge.

- Abulibdeh, A., Al-Awadhi, T., & Al-Barwani, M. (2019b). Comparative analysis of the driving forces and spatiotemporal pattern of urbanization in Muscat, Doha, and Dubai, Development in Practice, 29(5), 606–618. doi:10.1080/09614524.2019.1598335.

- Abulibdeh, A., Andrey, J., & Melnik, M. (2015b). Insights into the Fairness of Cordon Pricing based on origin-destination data. Journal of Transport Geography, 49, 61–67. doi:10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2015.10.014.

- Abulibdeh, A., & Zaidan, E. (2017). Empirical analysis of cross-cultural information acquisition and travel behaviour of business travellers: A case study of MICE travellers to Qatar in the middle East. Applied Geography. 85 (2017), 152–162. doi:10.1016/j.apgeog.2017.06.001

- Abulibdeh, A., and Zaidan, E. (2018). High-occupancy toll (HOT) lanes on the main highways of the city of Abu Dhabi: The public’s willingness to pay. Journal of Transport Geography, 66, 91–105. doi:10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2017.11.015.

- Abulibdeh, A., Zaidan, E., & Al-Saidi, M. (2019a). Development drivers of the water-energy-food nexus in the Gulf Cooperation Council region, Development in Practice, 29(5), 582–593, doi:10.1080/09614524.2019.1602109.

- Abulibdeh, A., & Zaidan, E. (2020). Managing the water-energy-food nexus on an integrated geographical scale, Environmental Development, 33(March 2020), 100498. doi:10.1016/j.envdev.2020.100498.

- Abulibdeh, A. Zaidan, E. & Abuelgasim, A. (2015a). Urban form and travel behavior as tools to assess sustainable transportation in the greater toronto area. Journal of Urban Planning and Development, 140(2).

- Al Buainain, F. (1999) Urbanisation in Qatar: A study of the residential and commercial land development in Doha City, 1970–1997. Ph.D. Thesis, ESRI, Department of Geography, University of Salford: UK.

- Al-Ammari, B., & Romanowski, M. H. (2016). The impact of globalisation on society and culture in Qatar, Pertanika Journal of Social Science and Humanities, 24(4), 1535–1556.

- Alraouf, A., and S. Clarke. (2014). The predicament of sustainable architecture and urbanism in contemporary Gulf cities. In P. Sillitoe (Eds.), Sustainable development: An appraisal focusing on the Gulf region, 313–342. New York: Berghahn.

- Al-Sabouni, M. (2016). Battle for Home: The Vision of a Young Architect in Syria (UK: Thames & Hudson).

- Al-Saidi, M., & Zaidan, E. (2021, forthcoming). Gulf futuristic cities beyond the headline: understanding the planned cities megatrend. Energy Reports.

- Al-Saidi, M., Zaidan, E., & Hammad, S. (2019). Participation modes and diplomacy of Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries towards the global sustainability agenda, In Development in Practice, 29(5), 545–558. Routledge. doi:10.1080/09614524.2019.1597017.

- Al-Zo’by, M. (2019) Culture and the politics of sustainable development in the GCC: Identity between heritage and globalisation, Development in Practice, Routledge.

- Bagaeen, S. (2007). Brand Dubai: The Instant City; or the instantly recognizable city. International Planning Studies, 12(2), 173–197. doi:10.1080/13563470701486372.

- Bloch, R. (2010). Dubai’s long goodbye, International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 34(4), 943–951. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2427.2010.01014.x.

- Chang, T. C. (1999). Local uniqueness in the global village: Heritage tourism in Singapore. The Professional Geographer, 51(1), 91–103. doi:10.1111/0033-0124.00149.

- Crook, S., Pakulski, J., & Waters, M. (1992). Postmodernization: Change in Advanced Society (London: Sage).

- Elessawy, F., & Zaidan, E. (2014). Living in the move: Impact of guest workers on population characteristics of the United Arab Emirates (UAE), The Arab World Geographer, 17(1), 2–23.

- Elsheshtawy, Y. (Ed.). (2008). The evolving Arab City: Tradition, modernity and urban development. UK: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780203696798.

- Elsheshtawy, Y. (2010). Dubai. Behind an Urban Spectacle (Abindgon: Routledge (Planning, history and environment series)). http://site.ebrary.com/lib/alltitles/docDetail.action?docID=10320420

- Ewers, M. C. (2016). International knowledge mobility and urban development in rapidly globalizing areas: Building global hubs for talent in Dubai and Abu Dhabi, Urban Geography, 38(2), 291–314. doi:10.1080/02723638.2016.1139977.

- Grander, M. A. (2014). How the city grows: Urban growth and challenges to sustainable development in Doha, Qatar. in: P. Sillitoe (Ed) Sustainable Development: An Appraisal Focusing on the Gulf Region, pp. 343–366 (New York: Berghahn).

- Gremm, J., Barth, J., Fietkiewicz, K. J., & Stock, W. G. (2018). Transitioning Towards a Knowledge Society (Cham: Springer International Publishing).

- GSDP. (2008). Qatar National Vision 2030 (Doha, QA: General Secretariat for Development Planning).

- Hague, C., & Jenkins, P. (2004). Planning and place identity. In C. Hague & P. Jenkins (Eds.), Place Identity, Participation and Planning (pp. 2–15). London: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780203646755.

- Hawas, E. Y., Hassan, N. M., & Abulibdeh, O. A. (2016). A multi-criteria approach of assessing public transport accessibility. Journal of Transport Geography. 57, 19–34. doi:10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2016.09.011.

- Hazime, H. (2011). From city branding to e-Brands in developing countries: An approach to Qatar and Abu Dhabi, African Journal of Business Management, 5(121), 4731–4745.

- Kamrava, M. (2015). Qatar: Small State, Big Politics (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press).

- Kassem, L., & Al-Muftah, E. E. (2016). The Qatari family at the intersection of policies. in: M. E. Tok, L. R. M. Alkhater, & L. A. Pal (Eds) Policy-making in a Transformative State. The Case of Qatar, pp. 213–239 (London, UK: Palgrave Macmillan).

- Koolhaas, R., Bouman, O., Wigley, M. (Eds.). (2017). Al Manakh (Vol. 12). Columbia University GSAPP/Archis.

- Melotti, M. (2014). Heritage and tourism. Global society and shifting values in the United Arab Emirates, Middle East -topics and Arguments, 3(December), 71–91.

- Mould, O. (2012). Creative city: Four projects bringing arts and culture to Dubai. http://thisbigcity.net/creative-city-four-projects-bringing-arts-and-culture-to-dubai/ (accessed March 28, 2020).

- Nagy, S. (2006). Making room for migrants, making sense of difference: Spatial and ideological expressions of social diversity in Urban Qatar, Urban Studies, 43(1), 119–137. doi:10.1080/00420980500409300.

- Ogaily, A. (2015). Urban planning in dubai; cultural and human scale context, Paper presented at annual meeting for the society of council on tall buildings and urban Habitat, New York, October 26–30.

- Picton, O. J. (2010). Usage of the concept of culture and heritage in the United Arab Emirates – An analysis of Sharjah Heritage Area, Journal of Heritage Tourism, 5(1), 69–84. doi:10.1080/17438730903469813.

- Ponzini, D., & Nastasi, M. (2011). Star Architecture, Scenes, Actors and Spectacles in Contemporary Cities (Umberto Allemandi & C: Turin).

- Riad, M. (1981). Some aspects of petro-urbanism in the Arab Gulf States. Bulletin of the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences (Qatar University), 4, 7–24.

- Rizzo, A. (2013), Metro Doha, Cities, 31, 533–543. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2011.11.011.

- Rizzo, A. (2017). Sustainable urban development and green megaprojects in the Arab states of the Gulf Region: Limitations, covert aims, and unintended outcomes in Doha, Qatar, International Planning Studies, 22(2), 85–98. doi:10.1080/13563475.2016.1182896.

- Rizzo, A., & Glasson, J. (2011). Conceiving transit space in Singapore/Johor: a research agenda for the Strait Transnational Urban Region (STUR). International Journal of Urban Sustainable Development, 3(2), 156–167. doi:10.1080/19463138.2011.590722.

- Rizzo, A., & Khan, S. (2013), Johor Bahru’s response to transnational and national influences in the emerging Straits Mega-City Region, Habitat International, 40, 154–162. doi:10.1016/j.habitatint.2013.03.003.

- Shatkin, G. (2008). The city and the bottom line: Urban megaprojects and the privatization of planning in Southeast Asia, Environment and Planning A, 40(2), 383–401. doi:10.1068/a38439.

- Stephenson, M. L. (2013). Tourism, development and ‘Destination Dubai’: Cultural dilemmas and future challenges, Current Issues in Tourism, 17(8), 723–738. doi:10.1080/13683500.2012.754411.

- Swyngedouw, E., & Baeten, G. (2001). Scaling the city: The political economy of 'glocal' development - Brussels' conundrum. European Planning Studies, 9(7), 827–849. doi:10.1080/09654310120079797.

- Timothy, D. (2017). Tourism and Geopolitics in the GCC Region. in: M. Stephenson & A. Al-Hamarneh (Eds) International Tourism Development and the Gulf Cooperation Council States: Challenges and Opportunities, pp. 45–60 (London: Routledge).

- Wiseman, A., Alromi, N., & Alshumrani, S. (2014). Challenges to creating an Arabian Gulf knowledge economy. in: A. W. Wiseman, N. H. Alromi, & S. Alshumrani (Eds) Education for a Knowledge Society in Arabian Gulf Countries, pp. 1–33 (Bingley, UK: Emerald).

- Zaidan, E. (2015). Tourism planning and development in Dubai: Developing strategies and overcoming barriers, in: M. Kozak & N. Kozak (Eds) Tourism Development, pp. 76–92 (Cambridge Scholars Publishing).

- Zaidan, E. (2016). The impact of cultural distance on local resident’s perception of tourism development: The case of Dubai in UAE, Tourism, 64(1), 109–126.

- Zaidan, E. (2019a). Cultural-based challenges of the westernized approach to development in newly developed societies. Development in Practice, 29(5), 670–681. Routledge.

- Zaidan, E. (2019b). Tourism, shopping, and hyper-development in the MENA region. In D.J. Timothy (Ed.), Routledge handbook on tourism in the Middle East and North Africa. London: Routledge.

- Zaidan, E., and Abulibdeh, A., (2018). Modeling ground access mode choice behavior for hamad international airport in the 2022 FIFA World Cup city, Doha, Qatar. Journal of Air Transport Management, 73, 32–45. doi:10.1016/j.jairtraman.2018.08.007.

- Zaidan, E, and Abulibdeh, A. (2019). Qatar: Political, economic and social issues. The new cultural turn in urban development for the Gulf state: Creativity, place promotion, and identity: Doha as a case study. In H. Al-Khateeb (Ed.) Qatar: Political, economic and social issues. USA: Nova Sciences.

- Zaidan, E., Al-Saidi, M., & Hammad, S. (2019). Sustainable development in the Arab world – Is the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) region fit for the challenge? Development in Practice, 29(5), 670–681. Routledge. doi:10.1080/09614524.2019.1628922.

- Zaidan, E., Kovacs, J. F., Zaidan, E., & Kovacs, J. F. (2017). Resident attitudes towards tourists and tourism growth: A case study from the Middle East, Dubai in United Arab Emirates, European Journal of Sustainable Development, 6(1), 291–307. doi:10.14207/ejsd.2017.v6n1p291.