ABSTRACT

Previous research has shown that the comprehensive-integrative planning model seems to be expedient for modernising planning systems, specifically regarding the relation between spatial planning and sectoral policies. However, contemporary, and particularly comparable studies are non-existent. Based on empirical findings from a European research project our comparative analysis explores whether spatial planning in nine countries conforms to key features of this idealised planning model. Our analysis reveals discrepancies regarding how spatial planning is positioned in relation to sectoral policies across the various countries. We argue that this planning model appears rather to be in a state of dissolution than of consolidation.

Introduction

According to the ‘Compendium on Spatial Planning Systems and Policies’ (CEC, Citation1997), a fundamental feature of the comprehensive-integrated spatial planning tradition in Europe is to coordinate the spatial impacts of different sectoral policies. This Compendium, and the large study behind it, has become a key reference for comparing spatial planning systems in both theory and practice during the last two decades (Nadin & Stead, Citation2013; Reimer et al., Citation2014). The Compendium (CEC, Citation1997) suggests that the comprehensive-integrative spatial planning tradition represents one of four so-called ideal types of spatial planning. Vertical integration of plans and policies from the national to the local levels and horizontal coordination of different sectoral policy fields are central to this spatial planning tradition. Ideally, the process of coordination should lead to policy integration or to other forms of consensual agreements and synergies such as policy packages (Stead & Meijers, Citation2009).

In this paper, we compare the horizontal coordination of different sectoral policy fields as a central characteristic of the comprehensive-integrated planning tradition across nine carefully selected countries. The objective is to investigate how spatial planning is positioned in relation to ten sectoral policy fields. Based on empirical findings from a comparative European research project, we explore the extent to which the nine countries show evidence of a strong relation between spatial planning and sectoral policy fields. The nine countries are all assigned to the comprehensive-integrative tradition in the available literature (e.g., CEC, Citation1997, ESPON, Citation2007, Dühr et al., Citation2010). First, we investigate how spatial planning is positioned in relation to these ten different sectoral policy fields at the national, sub-national and local levels in the nine different countries. Second, we consider the influence of these sectoral policy fields on spatial planning debates, i.e. the extent to which these sectoral policy fields actually influence the normative direction of spatial planning plans, programmes and policies.

In the following section, we first provide a conceptual background to the different models of spatial planning, with a particular focus on the comprehensive-integrative model. After that, we discuss the comparative methodology and some further conceptual underpinnings as well as the rationales for the selection of countries and sectoral policy fields on which the empirical analysis of the paper is based. In the section thereafter, we present the empirical results, which highlight both the role of spatial planning in different sectoral policy fields and how different sectoral policy fields influence the spatial planning debates in the nine countries, as well as to what extent their influence changed in the period 2000 to 2016. This section is followed by a discussion on the relation between spatial planning and sectoral policy fields. We argue that within this comprehensive-integrated model there are significant differences between countries, sectoral policy fields and policy levels, and the role of spatial planning therein. In the concluding section, we revisit the notion of the comprehensive-integrated planning model, as we call it here in accordance with Nadin and Stead (Citation2013). Since the level and scope of integration and the comprehensiveness of sectoral policy fields is limited in a number of the countries analysed, we claim that the comprehensive-integrated planning model is not being consolidated (as suggested by previous studies, e.g. ESPON, Citation2007), but rather is dissolving. Hence, we question the extent to which the comprehensive-integrated planning model can still function as an ideal model for the modernisation of spatial planning systems. This is a fundamental question in view of reappraising the substance and future normative direction of spatial planning across Europe in research and practice.

The Comprehensive-integrated Planning Model: Origins and Characteristics

The term ‘spatial planning’ evolved as a European concept in the early 1980s and became firmly established across Europe in the 1990s, particularly through the gestation and application of the European Spatial Development Perceptive (ESDP). However, the first policy paper that used this term was the so-called ‘Torremolinos Charter’ from 1983, also known as the ‘European regional/spatial planning charter’. This charter was issued by the standing European conference of Ministers responsible for Regional Planning (Conférence Européenne des Ministres responsables de l’aménagement du territoire, CEMAT), founded in 1970, which brings together representatives of 47 member states to discuss sustainable spatial development objectives. In the English version of the charter, it is stated that:

regional/spatial planning gives geographical expression to the economic, social, cultural and ecological policies of society. It is at the same time a scientific discipline, an administrative technique and a policy developed as an interdisciplinary and comprehensive approach directed towards a balanced regional development and the physical organisation of space according to an overall strategy (CEMAT, Citation1983, p. 13).

Furthermore, a number of key elements of spatial planning are addressed, such as its long-term orientation and the fact that spatial planning is supposed to span across territorial jurisdictions horizontally as well as being concerned with the vertical coordination of policies. But also, and this is key here, spatial planning is supposed to have a cross-sectoral character, and a coordinative and integrative function (CEMAT, Citation1983, p. 13). In the ESDP (CEC, Citation1999), the term ‘spatial planning’ is used rather vaguely without making further attempts to define its scope and meaning, because this would have been a political minefield, since spatial planning resides under the aegis of member states. However, the ESDP emphasises that sectoral policy integration is a key issue, which requires spatial planning to address conflicts between sectors but also requires close horizontal and vertical cooperation among the actors and authorities that are responsible for spatial development (CEC, Citation1999). In other words, these early conceptualisations of spatial planning as a generic European concept convey a number of ideals, norms, and expectations that highlight specifically the integrative and comprehensive function of spatial planning.

The ‘Compendium on Spatial Planning Systems and Policies’, which aimed ‘to define more precisely the meaning of the terms used in each country, rather than to suggest that they are the same’ (CEC, Citation1997, p. 23), has added much to our understanding of what spatial planning means in the various national contexts across the EU and how it is institutionalised in the various national planning systems. Indeed, as Schmitt and Van Well (Citation2017) noted, the term ‘spatial planning’ was adopted as a ‘neutral’ generic term in many European policy documents and debates, specifically in the 1990s and 2000s. The systematic study behind the Compendium revealed that the term does not equate to any one member state’s system, practices or culture for managing spatial development (see for instance Faludi, Citation2010; Dühr et al., Citation2010; Getimis, Citation2012; Reimer & Blotevogel, Citation2012; Knieling & Othengrafen, Citation2015). It also ’directed more attention to the variation of planning systems, cultures and perspectives in Europe, and increased interest in comparative planning research‘ (Nadin & Stead, Citation2013, p. 1543). To compare spatial planning systems, the Compendium identified four traditions of spatial planning based on seven criteria (see CEC, Citation1997, p. 34), which were termed ‘comprehensive-integrated’, ‘land-use management’, ‘regional economic’ and ‘urbanism’. Later on, Nadin and Stead (Citation2013, p. 1551) clarify that:

these traditions were developed as ‘ideal types’ and used in the study as measures against which the reality in member states was compared. […] the four traditions were never meant to imply that planning systems fit neatly into a single tradition – the idea was that national planning systems in all member states show some degree of affiliation with all four traditions but are more closely related to certain traditions than others.

In accordance with Weber (Citation1949) they argue that due to the ideal type’s fictional nature, the idea was not to claim correspondence with social reality, but rather the ideal types are supposed to ”put the chaos of social reality in order” (Nadin & Stead, Citation2013, p. 1552). The authors further note that the Compendium (CEC, Citation1997) was not very clear about the use of ideal types, and a number of misinterpretations occurred in the many publications that related back to the Compendium as a point of reference (e.g., ESPON, Citation2007; Reimer et al., Citation2014; Servillo & Van Den Broeck, Citation2012).

As mentioned before, in this paper, we investigate spatial planning in nine European countries that are associated with the ideal ‘comprehensive-integrated’ type. In, accordance with Nadin and Stead (Citation2013), in the following we use the term comprehensive-integrated planning ‘model’, not ‘type’, to avoid any further misinterpretations. In the Compendium (CEC, Citation1997) this model is characterised by a systematic and formal hierarchy of plans from the national to the local levels, whereas spatial planning is expected to coordinate public sector activity across different sectoral policies. In other words, the coordination, which may even lead to different forms of policy integration, of spatially relevant policies, programmes and projects is one of the model’s central characteristics. This does not mean that elements of the other three models, i.e. ‘land-use management’, ‘regional economic’ and ‘urbanism’, are not to be found in the one or other country that is assigned to the comprehensive-integrated model.

Furthermore, in the Compendium the comprehensive-integrated model is associated with mature or complete spatial planning systems. This means that the ideal model has a comparatively high level of public acceptance regarding the need for (public) planning and regulation, the provision of up-to-date policy instruments, vertical cooperation and integration between levels of administration and other official organisations, and, finally, the existence of transparent and productive consultation mechanisms to incorporate the many relevant interests in the planning process. In addition, it is stressed that this model requires responsive and sophisticated planning institutions and mechanisms and considerable political commitment to the planning process. As a final point, it is stated in the Compendium that public sector investments play an important role in supporting or bringing about whatever form of spatial development the planning frameworks within this model intend to control, maintain or promote (CEC, Citation1997, p. 35–37).

Ten years after the Compendium was published, a large European study indicated that many countries, specifically those that joined the EU in 2004 and 2007 had modernised their planning systems by following some of these features of the comprehensive-integrated model (ESPON, Citation2007). In addition, the Territorial Agenda of the European Union from 2011, a follow-up policy document of the ESDP and the Territorial Agenda from 2007, addressed the coordination and integration of sectoral policy fields at all territorial levels in a number of its recommendations on how to promote territorial cohesion across the EU. For instance, under point 59 it is stated that:

[w]e [the Ministers responsible for Spatial Planning and Territorial Development] encourage Member States to integrate the principles of territorial cohesion into their own national sectoral and integrated development policies and spatial planning mechanisms’ (Ministers responsible for Spatial Planning and Territorial Development, Citation2011, p. 10).

In other words, this key characteristic of the comprehensive-integrated model should not only be understood as an analytical category, but also as a normative goal that national planning systems should strive for. Drawing upon the aforementioned study from 2007 and the Compendium from 1997, Dühr et al. (Citation2010) provide a synthesised conceptualisation of this planning model, emphasising that notions such as ‘coordination’ and ‘integration’ of those sectoral policies which have a spatial impact are the key characteristic. They suggest that:

[t]he comprehensive-integrated model is about spatial coordination. It has a wide scope and its main task is to provide horizontal (across sectors), vertical (between levels) and geographical (across borders) integration of the spatial impacts of sectoral policies. […] European countries that show features of this ideal type [or model] include: AT, DK, FI, NL, SE, DE, BG, EE, HU, LV, LT, PL, RO, SL, SV. (Dühr et al., Citation2010, p. 182).

Hence, this definition further underscores the expectation that the national spatial planning systems assigned to this model are supposed to demonstrate a close relationship between spatial planning and those sectoral policy fields that have a significant impact on land-use planning and/or spatial development.

In this paper, we follow this notion as it helps us to question the seemingly ‘comprehensive-integrated’ nature of those national spatial planning systems that are assigned to this model. Drawing upon recently gathered comparative data, we do this at first by analysing the extent to which specific sectoral policy fields are actually ‘coordinated’ or ‘integrated’ with spatial planning, and secondly, by investigating how sectoral policy fields influence spatial planning debates, through which we assess the extent to which the national planning system under consideration can be considered ‘comprehensive’.

Methodological and Conceptual Notes

The applied research project commissioned by the ESPON 2020 Cooperation Programme: Comparative Analysis of Territorial Governance and Spatial Planning Systems in Europe (COMPASS), on which this paper is based was to some degree a follow-up on the Compendium-study discussed above (CEC (Commission of the European Communities), Citation1997). In the project, we investigated territorial governance and spatial planning systems in 32 countries (the EU 28 plus Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway and Switzerland).

By means of two extensive questionnaires, information about spatial planning systems and territorial governance was collected (ESPON, Citation2018b). It should be noted that besides information about the current state and shifts within the spatial planning systems (e.g. organisational aspects, instruments, relation to sectoral policy fields), roughly one third of the questions were focused on European territorial governance and the influence of EU policies on the domestic planning systems (ESPON, Citation2018c). National experts, in most cases academic scholars that either originated from or did research work in the country under consideration, responded to the questionnaires. They assessed the available national literature and analysed collected national-based information on various aspects of the national spatial planning system concerned. These national experts also consulted other experts in the country of their responsibility, i.e. academic scholars and planning professionals, in order to gather additional information and discuss (their) preliminary assessments through interviews or focus group meetings (ESPON, Citation2018b).

The first questionnaire was orientated towards the formal structure of the institutions of spatial planning, while the second focused on how spatial planning operates in practice by putting emphasis on the relationship between strategy, policy, decisions, outputs and outcomes. The analysis that is presented here draws particularly upon the results from the second questionnaire. In this questionnaire, two sets of questions were explicitly about the relations between spatial planning and sectoral policy fields. The first set of questions addressed to what extent spatial planning is

integrated with sectoral policy fields (i.e. targeted at similar policy goals),

coordinated with sectoral policy fields (i.e. visible efforts to align policies and measures),

informed by sectoral policy fields (i.e. making references to in e.g. policy documents, but no further efforts towards coordination or integration), or

ignored (i.e. no tangible relations or recognition) by sectoral policy fields.

The national experts were also asked to specify at which policy level (national, sub-national or local) this relation becomes tangible. The focus was thus on the horizontal coordination and integration of the different sectoral policy fields, and not on the vertical relations between these levels (Vigar, Citation2009).

The second set of questions addressed to what extent other sectoral policy fields were influential on spatial planning debates; i.e. the extent to which these sectoral policy fields were ‘very influential’, ‘influential’, ‘neutral’ or ‘not influential’ concerning the normative direction of spatial planning plans, programmes and policies in 2016 (as a year of reference); and how the degree of influence differed compared to the degree of influence in 2000 (ESPON, Citation2018b). These evaluative adjectives were not further defined, since the sort of influence that may have occurred can differ enormously because of the multitude and scope of the various considered sectoral policy fields in each of the nine countries. Hence, this question aimed to provide an indication rather than a definite answer.

These sectoral policy fields were pre-defined based on three underpinning functions of spatial planning: developing, provisioning and preserving. Since these sectoral policy fields are structured differently in different countries they were grouped into broad generic categories (e.g. ‘agriculture and rural policy’ or ‘cultural, heritage and tourism policy’).

Conceptually, the resulting analysis is underpinned by the observation that spatial planning is seen as a mechanism or a ‘locus for integration’ (Vigar, Citation2009), and as such spatial planning ‘[…] can play an integrating role between sectors and it can also fulfil an objective setting role, steering sectoral policies’ (Stead & Meijers, Citation2009, p. 329). The role of spatial planning within sectoral policy fields is an indicator of its position in relation to these sectoral policy fields as well as of its potential contribution in respect of the implementation of policies stemming from these sectoral policy fields. The influence of sectoral policy fields within spatial planning debates is an indicator of the level of susceptibility to sectoral policy fields.

However, our comparative approach implies that spatial planning is perceived as an individual or autonomous policy field, which is questionable since other policy fields are often needed for the implementation of spatial planning policies (Albrechts, Citation2004; Stead & Meijers, Citation2009). In addition, when conceptualising spatial planning as an individual policy field it is important to recall that spatial planning is differently empowered compared to many sectoral policy fields, since it is generally less well equipped with financial resources and less supported by lobby organisations compared to many other sectors across Europe (Kunzmann & Koll-Schretzenmayr, Citation2015). Therefore, spatial planning is deemed to convey its political intentions to a greater extent compared to other sectors, through persuasive concepts, by developing causal connections between events, functions and institutions, suggesting applicable trade-offs and, finally, through adapting or changing various kinds of institutions (Madanipour, Citation2010; Van Assche et al., Citation2014).

On the other hand, the conception of spatial planning as an individual policy field, which is implied here, allows straightforward analysis and comparison of the relation between spatial planning and sectoral policy fields. Hence, our structuralist approach to analysing spatial planning systems across nine countries and in relation to ten sectoral policy fields builds upon generic definitions and some simplifications in order to be able to compare the relation between spatial planning and sectoral policy fields instead of carving out specificities or even good or bad practices. Hence, we have deliberately abstained from searching for single examples or cases in the literature to underpin any national expert’s assessment, since their assessments are supposed to be based upon countrywide, generic and objective appraisals and not on paraphrasing or highlighting well-studied or cited local cases. Instead, we argue that in order to put the presented assessments here on a more robust footing a large number of in-depth case studies per country would be required. This would mean that a rather strict comparative research design would have to be followed covering the prevailing institutional contexts, actor constellations, power structures and so on. Such investigations would also need to provide a deeper understanding of the governance practices and the various rationales that underpin the relation between spatial planning and sectoral policy fields (Schmitt & Wiechmann, Citation2018), and the many facilitators and inhibitors therein (Stead & Meijers, Citation2009). Hence, the results discussed here provide a comparative cross-national overview of trends, commonalities and differences, and as such may trigger further in-depth research in this direction.

In addition, our literature review has confirmed the observation made by Stead and Meijers (Citation2009) ten years ago. Although a number of studies have examined the interplay of different sectoral policy fields on specific issue areas, such as eco-system services, marine issues or environmental problems (see for instance Fürst et al., Citation2017; Ingold et al., Citation2019; Jordan & Lenschow, Citation2010; Sandström et al., Citation2011), there are few that centre around the role of spatial planning. Most of these rare examples address the complex integration of ‘single’ sectoral policy fields with spatial planning such as flood risk management (e.g., Ran & Nedovic-Budic, Citation2016), environmental policy (e.g., Runhaar et al., Citation2009; Weber & Driessen, Citation2010), transport policy (e.g., Hrelja, Citation2015; Rode, Citation2019), energy policy (e.g., Liljenfeldt, Citation2015; Wolsink, Citation2010) or economic development issues such as place branding (e.g., Van Assche et al., Citation2020; Pasquinelli & Vuignier, Citation2020).

A different perspective is provided by the work of Harris and Hooper (Citation2004) who analysed how ‘spatial content’ is addressed in sectoral policy documents in order to assess the potential for spatial planning instruments to facilitate ‘joined-up’ coherent policies. Within this strand of research one can also include the investigation by Evers and Tennekes (Citation2016) on the impacts of EU sectoral policies on spatial planning in the Netherlands, and the paper by Priemus (Citation1999) who problematises the non-coordination between different Dutch national ministries due to their diverging sectoralised views on urbanisation. What these contributions have in common is that they articulate that the role of spatial planning is weak in coordinating different normative agendas stemming from different sectoral policy fields and in synchronising their often diverging spatial logics. Another limiting factor is the rather modest financial and political backing of spatial planning as an own policy field. Therefore, ‘[t]he desire for sectoral policy integration […] leading to approaches involving ’policy packages‘, or combinations of policy sectors, such as land-use, transport and environment or heritage, tourism and economic development’ (Stead & Meijers, Citation2009, p. 318), which is a key feature underpinning the comprehensive-integrated planning model, cannot be taken for granted.

Compared to this literature briefly addressed above, our analysis presents a different and novel approach by applying a comparative analysis between nine different countries and ten different sectoral policy fields, instead of drawing upon specific cases of one sectoral policy field in one country, region or city, for instance. This allows us to analyse and position the current state of the comprehensive-integrated planning model in Europe.

In contrast to the original COMPASS study, in which 14 sectoral policy fields were studied, we focus here only on ten, namely ‘energy policy’, ‘environmental policy’, ‘transport policy’, ‘cultural heritage’ and ‘tourism policy’, ‘housing policy’, ‘cohesion and regional policy’, ‘agricultural and rural policy’, ‘industrial policy’, ‘retail policy’, and ‘waste and water management’. This means that we have deliberately excluded ‘health and (higher) education policy’, ‘ICT and digitalisation policy’, ‘maritime policy’ and ‘mining policy’, since they are only relevant in some of the nine countries that are analysed here.

For practical analytical reasons we have also excluded a few countries (such as Latvia, Austria and Finland) that were assigned to the comparative-integrative model in earlier studies (see CEC, Citation1997; ESPON, Citation2007) to keep our analysis here clearly arranged and applicable. The carefully selected nine countries were grouped into three geographical sub-groups; the Scandinavian countries (Denmark, Norway and Sweden), the Western European countries (Germany, the Netherlands and Switzerland) and the Eastern European countries (Hungary, Poland and Rumania). The selected countries thus provide an appropriate geographical coverage, especially since the comprehensive-integrated planning model is less evident in Southern Europe (CEC, Citation1997; ESPON, Citation2007).

The Role of Spatial Planning within Sectoral Policy Fields

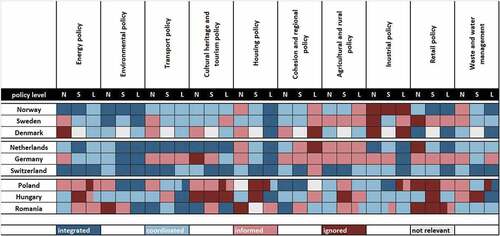

In the following, we discuss the extent to which spatial planning is ‘integrated’, ‘coordinated with’, ‘informed’ or ‘ignored’ by each of the ten sector policy fields. Here we also distinguish between three different policy levels (national = N, sub-national = S, and local = L; see ).

Figure 1. The role of spatial planning within ten different sectoral policy fields at the national, sub-national and local levels in nine different countries.

Our results show that within the ‘environmental policy’ field, spatial planning is either integrated, which means targeted at similar goals, or at least coordinated through efforts at alignment across the nine investigated countries (see ). ‘Transport’, ‘energy’, ‘housing’ as well as ‘cultural heritage and tourism’ are four other policy fields within which spatial planning is actively integrated or coordinated across many of the analysed countries here, but with more variations between countries and across the different policy levels compared to the environmental policy field. The two sectoral policy fields, ‘industrial policy’ and ‘retail policy’, show significant variations between countries and policy levels. Active integration and coordination efforts are thus directed mainly towards traditional areas for spatial planning (e.g. ‘transport’) and policies that have been high on the political agenda in recent years such as ‘environment’, ‘energy’, ‘cultural heritage and tourism’, and ‘housing’. While the sectoral policy fields of ‘regional and cohesion policy’ as well as ‘agricultural and rural policy’ are more focused on informative activities compared to the aforementioned policy fields. The role of spatial planning in the sectoral policy fields of ‘industry’ and ‘retail’ varies significantly between countries and policy levels. Overall, these differences give us interesting insights into the level of comprehensiveness of spatial planning, by reflecting upon whether spatial planning is related strongly to many of such sectoral policy fields or rather to only a few specific ones.

The local level seems to be the key level for policy integration and coordination, especially regarding ‘housing policy’ (which is rather unsurprising due to the distribution of competences) but also ‘environmental policy field’. Although the sub-national level is often considered to be the prime level for spatial planning and policy integration and coordination (see Alden, Citation2006; Neuman & Zonneveld, Citation2018) it does not stand out as more or less important compared to the national or local levels. Denmark is a special case, since the mandate for spatial planning was removed in the late 2000s from the sub-national level and is now only a concern at the local and national levels (Galland, Citation2012; Olesen & Carter, Citation2018). While ‘retail policy’ and spatial planning are coordinated and targeted towards similar goals at the local level in Switzerland, the Netherlands, Denmark and Norway, the role of spatial planning in retail policy is more or less neglected across all levels in Poland and Romania, and is not particularly relevant at any of the three policy levels in Germany and Sweden.

In general, there is no distinct or repeating pattern across the nine countries or within the three geographical sub-groups. However, the sub-groups as such are still discernible, since we can observe significant variations among the Scandinavian, Western European and the Eastern European countries. Among the three Eastern European countries, we can identify a diverse pattern of roles regarding spatial planning within sectoral policy fields and policy levels. However, across these three countries, the role of spatial planning is rather passive in a number of sectoral policy fields, for instance within ‘retail’, ‘energy’ as well as ‘cultural heritage and tourism’. More coherency and comprehensiveness is evident across the Western European countries. Switzerland stands out here, since spatial planning is perceived to be integrated or at least coordinated in all policy fields under consideration. Spatial planning in the Netherlands is integrated within ‘environmental’, ‘transport’ as well as within ‘cultural heritage and tourism policy’ across all three policy levels under consideration. In contrast, the picture in Germany is different, and less comprehensive; spatial planning only passively informs four sectoral policy fields, namely ‘transport’, ‘cohesion and regional policy’, ‘retail’, as well as ‘agricultural and rural policy’.

Across the Scandinavian countries, there are both similarities and differences. Norway and Sweden show rather similar repeating patterns, indicating a rather comprehensive approach in which spatial planning is coordinated and to some extent also integrated with many of the sectoral policy fields. ’Environmental policy’ and ‘industrial policy’ show similarities in the Scandinavian countries but at the two opposite sides of the active-passive spectrum, while the former sectoral policy field actively integrates spatial planning, the latter more or less ignores it. On the other hand, ‘energy’ and ‘retail policy’ are very differentiated among the three Scandinavian countries and across the three policy levels. To sum up, while in the Scandinavian country group Denmark diverges from the comprehensive-integrated planning model, it is Germany that diverges in the Western European country group. The Eastern European countries form the least coherent sub-group in this respect, due to the comparatively strong differences among Hungary, Poland and Romania when comparing the various sectoral policy fields and policy levels.

Influence of Sectoral Policy Fields within Domestic Spatial Planning Debates

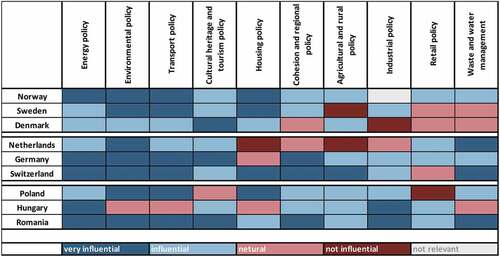

How other sectoral policy fields influence domestic spatial planning debates is more related to the notion of how spatial planning as a policy field of its own might integrate different sectoral policy fields (Stead & Meijers, Citation2009). The analysis of this influence indicates, here by referring to the year 2016, which sectoral policy fields are considered important for spatial planning, and it allows insights into the position of spatial planning in regard to sectoral policy fields that are perceived to have an influence on spatial planning in the country concerned.

indicates that domestic debates within spatial planning seem to be susceptible to a number of sectoral policy fields, in particular those which are traditionally influential, such as ‘transport’, but also those on which the EU has a particular influence, such as ‘energy’, ‘environment’ as well as ‘cohesion and regional policy’ (ESPON, Citation2018c). Subsequently, these sectoral policy fields are perceived to have a rather high influence on spatial planning debates across almost all countries, with the exception of ‘cohesion and regional policy’ in Denmark and the Netherlands. The influence of other policy fields on spatial planning debates varies more but there are only a few cases where other policy fields do not have any influence. Some policy fields, such as ‘housing policy’, are very influential in some countries but are assessed as having no influence in others.

Figure 2. The influence of sectoral policy fields on current domestic debates in spatial planning in 2016.

In terms of how other policy fields influence spatial planning debates, the Eastern European and the Scandinavian sub-groups seem to be the most coherent, while the Western European sub-group is more diverse. However, Norway differs from Denmark and Sweden, at least to some extent, since all sectoral policy fields except for ‘industrial policy’ are classified at least as influential, whereas in Denmark and Sweden four or three sectoral policy fields respectively, are assigned as neutral or not influential. In the Western European countries, the Netherlands deviates with a number of policy fields that have little influence on the debates on spatial planning. Also, the spatial planning debate in Denmark, Hungary, the Netherlands and to some extent also Sweden is influenced by fewer sectoral policy fields compared to the other countries of this survey in general, and Norway, Germany, Switzerland and Romania in particular.

When comparing the influence of sectoral policy fields on domestic debates in spatial planning between the year 2016 and the year 2000, the general assessment is that sectoral policy fields have an increased influence on domestic spatial planning debates in most of the reviewed countries during this period. However, it should be noted that these nine countries have had different starting points. In particular, one should recall the many political-administrative reforms and adjustments of spatial planning systems that were significant in the Eastern European countries, specifically in the time-span before and after their accession to the EU (ESPON, Citation2007, Citation2018a), which have affected the influence of sectoral policy fields on spatial planning. However, there are also a few exceptions. For instance, in Hungary, Denmark and the Netherlands a number of policy fields have become less influential, such as ‘environmental policy’ (Hungary and Denmark), ‘transport’ (Hungary), ‘cohesion and regional policy’ (the Netherlands, Hungary), ‘agricultural and rural policy’ (Hungary and the Netherlands), and finally ‘housing’ (the Netherlands). Concerning energy policy, we can notice that this sectoral policy field has become more influential in all countries, specifically pushed by debates on windfarm siting and the application of EU Energy directives, but with a particular increase in Germany and Hungary between 2000 and 2016.

On the other hand, the ‘agricultural and rural policy’ field is only very influential in Switzerland and has become less influential in both Hungary and the Netherlands since 2000. Also, ‘cohesion and regional policy’ has become less influential in Hungary and the Netherlands, but in Poland and Romania it has become significantly more influential. While ‘housing policy’ has become very influential in Sweden and Poland, it has decreased its influence in the Dutch and Danish spatial planning debate. Also, retail policy has decreased its influence within spatial planning in Denmark, whereas industrial policy has become significantly more influential in Hungary and Poland. Although the ‘environmental’ and ‘transport policy fields’ are generally influential, both have decreased their influence in Hungary, whereas in Denmark only one of them, namely environmental policy, decreased its influence between the years 2000 and 2016.

Overall, we can observe that domestic spatial planning debates are increasingly influenced by different sectoral policy fields. This increasing influence creates opportunities for policy integration and coordination. However, this may also mean that spatial planning is susceptible to other policy fields, which may make it difficult to coordinate the spatial impacts of different (conflicting) sectoral policy fields since the influence of one or the other sectoral policy field may dominate spatial planning debates. Another observation is that the influence of ‘agricultural and rural policy’ as well as ‘cohesion and regional policy’ is generally rather limited, which is noteworthy since in general the spatial implications of these sectoral policy fields are rather significant.

Discussion on the Relation between Spatial Planning and Sectoral Policy Fields

Spatial planning seems to be rather well integrated or at least coordinated with a number of key sectoral policy fields such as environmental, energy and transport policy, but much less in relation to the other analysed policy fields. Regarding the latter, we can recognise significant variations across policy levels and countries that are associated with the comprehensive-integrated planning model. In general, the influence of different sectoral policy fields on spatial planning debates increased across all countries between 2000 and 2016, but again with significant variations between sectoral policy fields. There seems to be a correlation between the influence of specific sectoral policy fields on spatial planning debates and the role of spatial planning within the same sectoral policy fields. The sectoral policy fields (i.e. energy, environment and transport) that are most influential on spatial planning are also those in which spatial planning is actively integrated and coordinated. The local level seems to be the most important scale for policy integration, although with significant differences across sectoral policy fields and countries. The importance of the local policy level is notable since it is the sub-national level, which is often associated with policy integration according to the comprehensive-integrated planning model. However, it is important to recognise that integration can have different facets and there are in practice a number of facilitators and inhibitors at play (see Stead & Meijers, Citation2009).

Active integration and coordination of spatial planning within other sectoral policy fields seem to be more established in the Western European countries and to some extent in the Scandinavian countries in comparison with Eastern European countries. The results indicate that the level of convergence, i.e. the extent to which the nine countries illustrate similarities regarding the integration and comprehensiveness of spatial planning in sectoral policy fields, is limited. Hence, the comprehensive-integrated planning model is difficult to distinguish even if there are some recurring patterns of two countries within two of the three sub-groups, namely Norway and Sweden on the one hand, and the Netherlands and Switzerland on the other. These four countries also seem to have the most coherent and comprehensive approach (i.e. incorporating a broad spectrum of the different sectoral policy fields analysed here). Certainly even among these countries, there is a significant degree of diversity concerning how a specific sectoral policy field is related to spatial planning.

However, there seems to be somewhat more convergence among the analysed countries regarding the question of how other sectoral policy fields influence spatial planning. On the one hand, the significant influence of different sectoral policy fields on domestic spatial planning debates may be an indication that spatial planning is recognised as important for policy implementation, at least in some of the nine countries, because of its integrative character. This significant influence can also be an indicator of the relatively strong position of spatial planning within policy-making and within the governmental system of the country concerned. On the other hand, a strong influence of sectoral policy fields can also indicate that spatial planning is rather susceptible to these sectoral policy fields and thus is dominated, if not even bypassed by them.

This discussion leads us to the question of to what extent spatial planning can be considered as an independent policy field. Certainly, this may vary from case to case and would require specific investigation into matters such as: power resources (e.g. legal, financial), power constellations among actors and institutions, available instruments and more or less routinised practices, prevailing taken-for-granted attitudes and other culturised practices that underpin spatial planning (e.g. Reimer & Blotevogel, Citation2012; Othengrafen, Citation2012). However, this question opens up the opportunity not only to revisit the question of to what extent spatial planning, or a specific policy, programme or project that is under consideration, can be assigned to the comprehensive-integrated model, but also whether and to what extent spatial planning is seen primarily as a tool for policy integration or as a transformative practice (Albrechts, Citation2010).

Conclusions: Dissolution Rather than Consolidation

Overall, our results show that there are significant differences between the nine countries both in terms of the role of spatial planning within different sectoral policy fields, but also in how different policy fields influence spatial planning debates. Hence, for spatial planning scholars and policy-makers in Europe alike, it is important to be mindful of these differences, and more specifically of the fact that spatial planning is differently positioned and empowered not only across countries, but also within countries, depending on which sectoral policy field is under consideration.

In conclusion, we question whether the comprehensive-integrative planning model has further consolidated across Europe in recent years through the modernisation of national planning systems, as observed by other authors (e.g. ESPON, Citation2007; Stead & Meijers, Citation2009; Nadin & Stead, Citation2013). Our results suggest that the level and scope of the ‘integration’ and ‘comprehensiveness’ of sectoral policy fields is selective and rather limited in a number of countries. This key feature of the comprehensive-integrative planning model is difficult to discern, which also implies that we need to question its analytical usefulness as well as its normative function as an ideal model for the modernisation of spatial planning systems in Europe.

Reappraising the comprehensive-integrated planning model also means to question the substance and normative direction of spatial planning as such. If the key feature of integrating and coordinating sectoral policies through spatial planning is not achievable in many countries, we need to question whether it can still function as a placeholder for what spatial planning is good for in a national context. In addition, and perhaps more importantly within the EU as such, ‘achieving the ideal of sectoral integration with a spatial perspective’ (territorial or place-based) is the key argument behind the concept of territorial cohesion (e.g., Zaucha et al., Citation2014).

We question the value of this ideal planning model as a unifying analytical construct, because our empirical informed analysis indicates that there is an increasing discrepancy between this idealised model and the extent to which spatial planning in a number of countries conforms with the key features of this model (i.e. integration and comprehensiveness). Hence, we argue that the comprehensive-integrative planning model appears to be rather out-dated and thus in a state of dissolution than of consolidation.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Albrechts, L. (2004) Strategic (spatial) planning re-examined, Environment and Planning. B, Planning & Design, 31(5), pp.743–758. doi:10.1068/b3065.

- Albrechts, L. (2010) More of the same is not enough! How could strategic spatial planning be instrumental in dealing with the challenges ahead? Environment and Planning. B, Planning & Design, 37(6), pp.1115–1127. doi:10.1068/b36068.

- Alden, J. (2006) Regional planning: An idea whose time has come? International Planning Studies, 11(3–4), pp. 209–223.

- CEC (Commission of the European Communities). (1997) The EU Compendium of Spatial Planning Systems and Policies (Regional Development Studies) (Luxemburg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities).

- CEC (Commission of the European Communities). (1999) European Spatial Development Perspective: Towards Balanced and Sustainable Development of the Territory of the EU (Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities).

- CEMAT (Conference Europeenne des Ministres responsables de l’aménagement du territoire). (1983) European regional/spatial planning Charter: Torremolinos Charter. Adopted at the Conference of European Ministers responsible for Regional Planning on 20th May 1983 at Torremolinos, Spain.

- Dühr, S., Colomb, C., & Nadin, V. (2010) European Spatial Planning and Territorial Cooperation (Milton Park, Abingdon: Routledge).

- ESPON. (2007) Governance of Territorial and Urban Policies from EU to Local Level. ESPON Project 2.3.2, Final Report, Luxembourg: ESPON Coordination Unit.

- ESPON. (2018a) COMPASS – Comparative Analysis of Territorial Governance and Spatial Planning Systems in Europe. Final Report, Luxembourg: ESPON Coordination Unit.

- ESPON. (2018b) COMPASS – Comparative Analysis of Territorial Governance and Spatial Planning Systems in Europe. Final Report - Additional Volume 2 – Methodology, Luxembourg: ESPON Coordination Unit.

- ESPON. (2018c) COMPASS – Comparative Analysis of Territorial Governance and Spatial Planning Systems in Europe. Final Report - Additional Volume 7 – Europeanisation, Luxembourg: ESPON Coordination Unit.

- Evers, D., & Tennekes, J. (2016) Europe exposed: Mapping the impacts of EU policies on spatial planning in the Netherlands, European Planning Studies, 24(10), pp.1747–1765. doi:10.1080/09654313.2016.1183593.

- Faludi, A. (2010) Cohesion, Coherence, Co-operation: European Spatial Planning Coming of Age? (Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, New York: Routledge).

- Fürst, C., Luque, S., & Geneletti, D. (2017) Nexus thinking – How ecosystem services can contribute to enhancing the cross-scale and cross-sectoral coherence between land use, spatial planning and policy-making, International Journal of Biodiversity Science, Ecosystem Services & Management, 13(1), pp.412–421. doi:10.1080/21513732.2017.1396257.

- Galland, D. (2012) Understanding the reorientations and roles of spatial planning: The case of national planning policy in Denmark, European Planning Studies, 20(8), pp.1359–1392. doi:10.1080/09654313.2012.680584.

- Getimis, P. (2012) Comparing spatial planning systems and planning cultures in Europe. The Need for a multi-scalar approach, Planning Practice and Research, 27(1), pp.25–40. doi:10.1080/02697459.2012.659520.

- Harris, N., & Hooper, A. (2004) Rediscovering the ‘Spatial’ in public policy and planning: An examination of the spatial content of sectoral policy documents, Planning Theory & Practice, 5(2), pp.147–169. doi:10.1080/14649350410001691736.

- Hrelja, R. (2015) Integrating transport and land-use planning? How steering cultures in local authorities affect implementation of integrated public transport and land-use planning, Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 74, pp. 1–13.

- Ingold, K., Driessen, P. P. J., Runhaar, H. A. C., & Widmer, A. (2019) On the necessity of connectivity: Linking key characteristics of environmental problems with governance modes, Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 62(11), pp.1821–1844. doi:10.1080/09640568.2018.1486700.

- Jordan, A., & Lenschow, A. (2010) Environmental policy integration: A state of the art review, Environmental Policy and Governance, 20(3), pp. 147–158.

- Knieling, J., & Othengrafen, F. (2015) Planning culture—A concept to explain the evolution of planning policies and processes in Europe? European Planning Studies, 23(11), pp.2133–2147. doi:10.1080/09654313.2015.1018404.

- Kunzmann, K. R., & Koll-Schretzenmayr, M. (2015) A planning journey across Europe in the year 2015, disP - the Planning Review, 51(1), pp.86–90. doi:10.1080/02513625.2015.1038081.

- Liljenfeldt, J. (2015) Legitimacy and efficiency in planning processes—(How) does wind power change the situation? European Planning Studies, 23(4), pp.811–827. doi:10.1080/09654313.2014.979766.

- Madanipour, A. (2010) Connectivity and contingency in planning, Planning Theory, 9(4), pp.351–368. doi:10.1177/1473095210371162.

- Ministers responsible for Spatial Planning and Territorial Development. (2011) Territorial Agenda of the European Union 2020: Towards an Inclusive, Smart and Sustainable Europe of Diverse Regions. Available at http://www.nweurope.eu/media/1216/territorial_agenda_2020.pdf (accessed 11 November 2019)

- Nadin, V., & Stead, D. (2013) Opening up the Compendium: An Evaluation of International Comparative Planning Research Methodologies, European Planning Studies, 21(10), pp.1542–1561. doi:10.1080/09654313.2012.722958.

- Neuman, M., & Zonneveld, W. (2018) The resurgence of regional design, European Planning Studies, 26(7), pp.1297–1311. doi:10.1080/09654313.2018.1464127.

- Olesen, K., & Carter, H. (2018) Planning as a barrier for growth: Analysing storylines on the reform of the Danish Planning Act, Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space, 36(4), pp. 689–707.

- Othengrafen, F. (2012) Uncovering the Unconscious Dimensions of Planning. Using Culture as a Tool to Analyse Spatial Planning Practices, 1st ed. (London: Routledge).

- Pasquinelli, C., & Vuignier, R. (2020) Place marketing, policy integration and governance complexity: An analytical framework for FDI promotion, European Planning Studies, 28(7), pp.1413–1430. doi:10.1080/09654313.2019.1701295.

- Priemus, H. (1999) Four ministries, four spatial planning perspectives? Dutch evidence on the persistent problem of horizontal coordination, European Planning Studies, 7(5), pp.563–585. doi:10.1080/09654319908720539.

- Ran, J., & Nedovic-Budic, Z. (2016) Integrating spatial planning and flood risk management: A new conceptual framework for the spatially integrated policy infrastructure, Computers, Environment and Urban Systems, 57, pp. 68–79.

- Reimer, M., & Blotevogel, H. H. (2012) Comparing spatial planning practice in europe: A plea for cultural sensitization, Planning Practice and Research, 27(1), pp.7–24. doi:10.1080/02697459.2012.659517.

- Reimer, M., Getimēs, P., & Blotevogel, H. H., (Eds.) (2014) Spatial Planning Systems and Practices in Europe: A Comparative Perspective on Continuity and Changes, 1st ed. (London: Routledge).

- Rode, P. (2019) Urban planning and transport policy integration: The role of governance hierarchies and networks in London and Berlin, Journal of Urban Affairs, 41(1), pp.39–63. doi:10.1080/07352166.2016.1271663.

- Runhaar, H., Driessen, P. P. J., & Soer, L. (2009) Sustainable urban development and the challenge of policy integration: An assessment of planning tools for integrating spatial and environmental planning in the Netherlands, Environment and Planning. B, Planning & Design, 36(3), pp. 417–431.

- Sandström, C., Lindkvist, A., Öhman, K., & Nordström, E.-M. (2011) Governing competing demands for forest resources in Sweden, Forests, 2(1), pp. 218–242.

- Schmitt, P., & Van Well, L. (2017) Tracing the place-based coordinative frameworks of EU Territorial Cohesion Policy: From European Spatial Planning towards European Territorial Governance, in: E. Medeiros (Ed) Uncovering the Territorial Dimension of European Union Cohesion Policy, pp. 97–113 (London and New York: Routledge).

- Schmitt, P., & Wiechmann, T. (2018) Unpacking spatial planning as the governance of place: Extracting potentials for future advancements in planning research, disP - the Planning Review, 54(4), pp.21–33. doi:10.1080/02513625.2018.1562795.

- Servillo, L. A., & Van Den Broeck, P. (2012) The social construction of planning systems: A strategic-relational institutionalist approach, Planning Practice and Research, 27(1), pp.41–61. doi:10.1080/02697459.2012.661179.

- Stead, D., & Meijers, E. (2009) Spatial planning and policy integration: Concepts, facilitators and inhibitors, Planning Theory & Practice, 10(3), pp.317–332. doi:10.1080/14649350903229752.

- Van Assche, K., Beunen, R., & Duineveld, M. (2014) Formal/informal dialectics and the self-transformation of spatial planning systems: An exploration, Administration & Society, 46(6), pp.654–683. doi:10.1177/0095399712469194.

- Van Assche, K., Beunen, R., & Oliveira, E. (2020) Spatial planning and place branding: Rethinking relations and synergies, European Planning Studies, 28(7), pp.1274–1290. doi:10.1080/09654313.2019.1701289.

- Vigar, G. (2009) Towards an integrated spatial planning? European Planning Studies, 17(11), pp.1571–1590. doi:10.1080/09654310903226499.

- Weber, M. (1949) The Methodology of the Social Sciences (E. Shils & H. A. Finch, Trans) (New York: Free Press).

- Weber, M., & Driessen, P. P. J. (2010) Environmental policy integration: The role of policy windows in the integration of noise and spatial planning, Environment and Planning. C, Government & Policy, 28(6), pp.1120–1134. doi:10.1068/c0997.

- Wolsink, M. (2010) Near-shore wind power—Protected seascapes, environmentalists’ attitudes, and the technocratic planning perspective, Land Use Policy, 27(2), pp.195–203. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2009.04.004.

- Zaucha, J., Komornicki, T., Böhme, K., Świątek, D., & Żuber, P. (2014) Territorial keys for bringing closer the territorial Agenda of the EU and Europe 2020, European Planning Studies, 22(2), pp.246–267. doi:10.1080/09654313.2012.722976.