ABSTRACT

‘Mediators’ are becoming recognized as necessary actors in managing complex socio-political dynamics in the ‘temporary use’ of vacant spaces. However, ‘mediation’ remains understudied and undertheorized in temporary use scholarship. To better articulate mediator roles in temporary use, I review literature on related ‘intermediary’ roles in ‘urban transitions’ literature vis-à-vis temporary use practice. Thereby, I propose a typology of roles in (inter)mediation and elucidate selected roles in practice. By articulating how mediators align interests, build networks and negotiate the conditions in planning and development, this article draws attention to changing professional roles in planning and sets a basis for future research.

Introduction

Complex global challenges such as climate change and resource depletion are putting pressure on cities to develop flexible modes of urban planning and adaptable use of the existing built environment. In recent decades, the ‘temporary use’ of vacant spaces and properties has become recognized by urban scholars and planners as a potential approach for addressing such issues in the Global North, notably Europe (Bishop & Williams, Citation2012; Oswalt et al., Citation2013; Henneberry, Citation2017). Scholars appreciate temporary use as an adaptive, resource-efficient and experimental approach to urban regeneration (Lehtovuori & Ruoppila, Citation2012; Galdini, Citation2020) and as a channel for local initiatives and participation (Németh & Langhorst, Citation2014). Further interpreted as a part of a broader transition towards iterative and process-oriented forms of planning (Oswalt et al., Citation2013; Honeck, Citation2017), temporary use addresses the argued incapacity of prevailing planning practices to accommodate complexity and uncertainty in today’s cities (e.g. de Roo & Boelens, Citation2016).

The term ‘temporary use’ implies interim, often user-driven activation of vacant properties or spaces pending political or development decisions (Lehtovuori & Ruoppila, Citation2012). Since the early 2000’s, a field of scholarship has emerged to study the potentials of such uses in planning (Haydn & Temel, Citation2006; Oswalt et al., Citation2013). While the term itself is ambiguous and the duration of such uses can range from months to years, even decades, it denotes a difference from the typical regulatory and temporal scope of planning targeted to ‘permanent’ land use. The potential impact of temporary use is, however, not limited to being an interim solution. Instead, many scholars draw attention to its capacity to reimagine the future potentials of places (Lehtovuori & Ruoppila, Citation2012; Andres & Kraftl, Citation2021) and to renegotiate existing structural conditions (Honeck, Citation2017). A recent example of such an approach in Finland is the revitalization of an underused office and logistics district, ‘Kera’, in the Helsinki metropolitan area with local cultural and sports actors as part of a longer-term urban transformation process.

Although many cities have introduced efforts to facilitate temporary uses or integrate them within formal planning (Honeck, Citation2017; Christmann et al., Citation2020), temporary use practices face many tensions and barriers. Firstly, they struggle within the structural conditions of planning and development, including stringent zoning practices, building codes and conventional business models and liabilities involved in real-estate development (Gebhardt, Citation2017). Secondly, temporary uses involve multiple actors with asymmetric power relationships and contradictory motivations (Andres, Citation2013; Németh & Langhorst, Citation2014). Temporary use can provide opportunities for diverse local actors to demonstrate alternative values and visions beyond profit-driven developments (Groth & Corijn, Citation2005). Yet, for developers or planners, temporary use may ultimately serve quite the opposite goals. Recently, scholars have paid critical attention to the potential co-optation of temporary uses in favor of neoliberalism (Tonkiss, Citation2013), gentrification (Bosák et al., Citation2020) or city marketing (Colomb, Citation2012) and the precarity of users (Madanipour, Citation2018). Evidently, temporary use operates within particularly complex and contested socio-political conditions.

Temporary use also entails changing professional roles. ‘Mediation’ is emerging as a professional role for actors who navigate the socio-political complexity involved in temporary use (Oswalt et al., Citation2013; Patti & Polyak, Citation2015; Jégou et al., Citation2018). While ‘mediators’ are recognized as necessary actors in temporary use (Henneberry, Citation2017), their work exceeds the traditional training and competencies of architects, planners or other professionals typically involved in planning and development (Hernberg & Mazé, Citation2017). However, despite growing interest, there is scant academic literature on mediation in temporary use.

To date, mediation has been explored mainly in non-academic reports on temporary use (e.g. Jégou et al., Citation2018) and accounts by practitioners themselves (Berwyn, Citation2012; Hasemann et al., Citation2017). Such reports demonstrate various types of mediators, ranging from activists to more established actors and organizations. Examples include private ‘agencies’ such as the ZwischenZeitZentrale Bremen (Hasemann et al., Citation2017; Hernberg, Citation2020), new public sector roles such as the ‘neighborhood managers’ in Ghent (Jégou et al., Citation2018; Hernberg, Citation2020), online platforms and NGOs (Jégou et al., Citation2018). The work of such actors can range from facilitating the relations between property owners, temporary users and authorities, advising and negotiating technical and legal issues, to lobbying government (Berwyn, Citation2012; Oswalt et al., Citation2013; Jegou & Bonneau, Citation2017). Overall, the emerging discourse provides some worthwhile yet preliminary elaborations of mediation practice in temporary use. However, there is a need for more systematic, theoretically grounded and empirically relevant studies to better understand and articulate this emerging phenomenon.

Therefore, to contribute to the theorization and analysis of mediation in temporary use, the objective of this article is to develop a systematic and nuanced articulation of mediator roles in temporary use.Footnote1 To address this objective, this article asks the following research questions: (1) How can we understand and articulate ‘roles’ in mediating temporary use? (2) In what ways are such roles performed by practitioners? Evidently, ‘role’ is a key aspect in focus here, which I will treat in more nuance in terms of activities, understood here as part of roles, as I will explain in more detail below.

To systematically articulate mediator roles, this article turns to literature in an adjacent field, ‘urban sustainability transitions’ (Wolfram et al., Citation2016; Frantzeskaki et al., Citation2017), where related work and roles of ‘intermediary’ actors have been elaborated recently (e.g. Hargreaves et al., Citation2013). This emerging field (here also referred to as ‘urban transitions’) cuts across disciplines including urban studies, policy, planning and geography, discussing the role of cities in advancing long-term transformations towards sustainability. Previously dominated by socio-technical discourses focusing on energy, water and transport infrastructures (e.g. Hodson & Marvin, Citation2009; Bulkeley et al., Citation2011), scholars in the field have recently emphasized the role of civic and grassroots initiatives in advancing sustainability (Buijs et al., Citation2016; Frantzeskaki et al., Citation2016). Thus, urban transitions discourse resonates with temporary use by addressing related socio-political dilemmas, including the complex dynamics and wide range of motivations of multiple actors involved in urban transition processes (e.g. Hodson et al., Citation2013).

Although urban transitions is a heterogeneous field, some key concepts from transitions researchFootnote2 are widely used. These include ‘regime’, constituting the dominant societal functions and ‘rules’, and ‘niche’, from which radical innovations emerge (Geels, Citation2002; Smith et al., Citation2010). In transitions research, the concepts of niche and regime are important for conceptualizing change and related socio-political dynamics. Characteristically, niche-level innovations struggle to break into the mainstream, while regimes actively resist change (e.g. Loorbach et al., Citation2017). These concepts help to elaborate the dynamics and power-relations between levels and the tensions entailed in advancing change within established institutional contexts. Recently, transitions scholars have drawn attention to the potential of intermediary actors in advancing change (e.g. Kivimaa et al., Citation2019a). This article finds the elaborations of ‘intermediary’ roles within urban transitions relevant for articulating mediation in temporary use.

Elaborating the ‘niche’ and ‘regime’ in temporary use helps understand the conditions underlying (inter)mediation. In transitions research, the concept of ‘regime’ articulates power and stability, representing dominant ‘rules’ that guide actors’ perceptions and actions. Such rules include shared beliefs, values, routines, regulations and capabilities (Geels, Citation2004, Citation2011). Regimes are characterized as highly persistent yet not necessarily coherent (Geels, Citation2004; Fuenfschilling & Truffer, Citation2014). Within temporary use, we can identify several powerful regimes. Firstly, the real-estate regime involves incumbent investment companies and standard economic and operational models. Property owners may prefer holding properties vacant due to rent expectations, valuation standards or responsibility concerns (Gebhardt, Citation2017). Secondly, planning and regulatory regimes regulate land use through zoning and building codes, which usually concern ‘permanent’ uses, thus subject to interpretation concerning temporary use (Hernberg, Citation2014; Gebhardt, Citation2017). Furthermore, entrenched patterns of knowledge, thought and action create barriers to change within such regimes (Filion, Citation2010; Dotson, Citation2016).

‘Niches’ are understood as the locus for path-breaking innovations and alternatives, which may challenge regimes and seed wider change (Raven et al., Citation2010). Niches ‘shield’ the development of innovations from regime conditions (Smith & Raven, Citation2012). Yet, particularly grassroots innovations struggle within the conditions they wish to transform (Smith et al., Citation2014). Similarly, temporary use can be understood as a niche-level or grassroots phenomenon that struggles to operate within regime conditions while simultaneously challenging them. Ways of shielding temporary use from regime conditions include low rents, specific contract terms or circumventing regulations (Gebhardt, Citation2017; Stevens & Dovey, Citation2019). Hence, conceptualizing temporary use as a niche-level phenomenon clarifies the socio-political struggle vis-à-vis regimes and the need for mediation.

Therefore, to systematically articulate mediator roles in temporary use, this article draws on recent studies in urban transitions which elaborate related ‘intermediary’ roles in theoretically and empirically grounded ways. Such studies provide relevant articulations of intermediaries navigating between multiple interests (Hodson et al., Citation2013), empowering niche development (Hargreaves et al., Citation2013) and potentially disrupting prevailing regimes (Matschoss & Heiskanen, Citation2018). In this article, I analyze the articulations of intermediary roles in such studies against a case of temporary use mediation practice. As a result, I propose a typology of roles in (inter)mediation. I will use ‘mediation’ and ‘intermediation’ as related terms in temporary use and transitions discourses but introduce (inter)mediation as a combination term.

Lastly, to build a more nuanced understanding of the theoretical (inter)mediation roles in temporary use, I elucidate selected roles through the case, ‘Temporary Kera’ (abbr. ‘Kera’), in which I studied my work as a mediator commissioned in a recent temporary use project by the municipality of Espoo, Finland. The project goal, linked to broader municipal sustainability goals, was to revitalize a suburban district struggling with vacancy. Kera was selected as a case for several reasons: As a recent, recognized European temporary use project, to which I had unique access as a practitioner, the case demonstrates nuances of mediation work and the evolving nature of the professional mediator roles. Displaying challenging niche-regime dynamics and conditions for temporary use, Kera was a relevant context for studying mediation. In Kera, the real-estate regime was particularly skeptical of the temporary use approach, while the potential users were in great need of affordable spaces. Furthermore, the municipal zoning policies and permissions presented barriers. To address such barriers, mediation work involved brokering between actors, aligning interests and negotiating the conditions for temporary use. Throughout the project, other participants urged the property owners to address the ‘resource-stupidity’Footnote3 of holding properties vacant.

Materials and Methods

To address the objectives and research questions articulated above, this article brings together knowledge from urban transitions literature and a case of temporary use practice to articulate roles in mediating temporary use. The methodological stages are described below.

To systematically articulate roles in (inter)mediation, I reviewed literature on intermediary roles in urban transitions, focusing on studies in urban grassroots and energy contexts that explicitly investigate intermediary roles. By identifying similarities and differences across the roles articulated in such studies, I developed synthetic categories of roles and comprising activities. In an integrative analysis, I further assessed these categories against coded data from the temporary use case, Kera.

The case study of Kera followed a qualitative, ‘practice-based research’ approach (Vaughan, Citation2017) to investigate my practice and engagements as a mediator in the project. Acknowledging my dual role as a researcher-practitioner, I formulated separate goals in the research plan and project contract. The project commissioner signed permission for collecting data within the project, and all informants were asked to sign informed consent. To collect data, I used ethnographic methods (Hammersley & Atkinson, Citation2007) and semi-structured interviews (Kvale & Brinkmann, Citation2009). The data include field notes, reflections and project logs, transcripts of audio-recorded meetings, workshops and interviews, and a survey with temporary users. To analyze the data, I used a ‘process coding’ technique (Saldaña, Citation2009) to identify categories of mediator roles and activities.

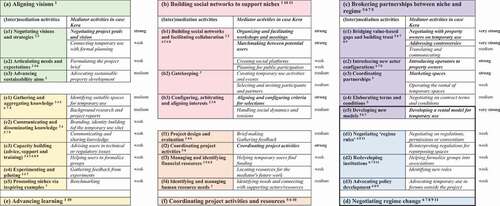

In an integrative analysis, I examined the synthetic role categories from urban transitions literature against coded categories from the case, Kera. This was done to investigate whether and in what ways the theoretically constructed roles were demonstrated in the case, assess the meaning of the terms in a temporary use context, specify and differentiate the role and activity categories and identify potential gaps in the theoretical categories. As a result of the integrative analysis, I developed a typology of roles in (inter)mediation, presented in detail in . Through the case, Kera, I further elucidate nuances of selected roles, demonstrated strongly in the case. The strength was estimated by the number of coded excerpts from the case corresponding to categories of the typology (see ).

Figure 1. A typology of roles in (inter)mediation.This typology differentiates six role categories (a to f) and comprising activity categories (a1 – f4). Corresponding activity categories from the temporary use case, ‘Kera’, are shown in columns on the right, also indicating the strength of resonance with the typology.

I acknowledge that this research approach involves the influence of subjectivity, ‘situated’ local conditions (Haraway, Citation1988) and ‘partiality’ of knowledge production (Harding, Citation2011) as inherent in practice-based and case study research. However, the practice-based approach has the advantage of providing unique access to ‘insider’ knowledge, seen as relevant for understanding an emerging phenomenon in-depth (Gray & Malins, Citation2004, p. 23). I am also aware of the influence of normative values of socio-ecological sustainability inherent in temporary use and urban transitions scholarships, also given in my commission in Kera. Hence, particular attention to the less powerful groups of ‘users’ and ‘niches’ is reflected in my analysis.

Articulating Roles in Urban (Inter)mediation

Recent non-academic reports on temporary use practice (e.g. Jégou et al., Citation2018) have started using colloquial terms and loose formulations to describe the roles of mediating actors. Mediators are identified as necessary in ‘arbitrating conflicts’ (Oswalt et al., Citation2013, p. 247), trust-building (Oswalt et al., Citation2013; Hasemann et al., Citation2017), translating (Rubenis, Citation2017) ‘negotiating,’ ‘moderating’ and ‘communicating’ between actors (Oswalt et al., Citation2013, p. 231, 247; De Fejter, Citation2017, p. 17). Additionally, mediators advise temporary users and negotiate on regulations, permissions and contracts (Oswalt et al., Citation2013; Rubenis, Citation2017). Furthermore, mediators can contribute to reducing structural barriers for temporary use (Berwyn, Citation2012) through lobbying government (Hasemann et al., Citation2017), developing new collaborative governance structures (Patti & Polyak, Citation2017; Matoga, Citation2019) or giving a voice to bottom-up initiatives (Matoga, Citation2019). Such reports offer useful yet preliminary elaborations of mediation roles and activities ranging from mundane to more strategic contributions.

Related studies in urban transitions offer a more mature and systematically developed vocabulary to articulate ‘intermediary’ roles, which I argue as useful for further elaborating ‘mediator’ roles in temporary use. Therefore, this section reviews literature on transition intermediaries vis-à-vis temporary use mediation practice to articulate roles in (inter)mediation.

To first clarify the theoretical understanding of ‘role’, I draw on transition scholars Wittmayer et al.’s (Citation2017) review of the concept of role in social interaction discourse (Turner, Citation1990; Collier & Callero, Citation2005; Simpson & Carroll, Citation2008). Wittmayer et al. describe roles ‘as a set of recognizable activities and attitudes used by an actor to address recurring situations’ (Citation2017, p. 51). They further consider roles as evolving and negotiated social constructions, which can be used as a ‘vehicle for mediating and negotiating meaning in interactions’ (Citation2017, p. 50). For the purposes of my analysis focusing on articulating roles in this article, I take the understanding that roles comprise activities, which are recognizable, purposeful and recurring, yet negotiated and evolving.

Intermediary Roles in Urban Transitions

‘Intermediary’ is a term widely used to characterize actors with an in-between position, increasingly studied within urban transitions (e.g. Hodson et al., Citation2013). This literature has its roots in innovation studies and science and technology studies (e.g. Baum et al., Citation2000; Howells, Citation2006). Within urban transitions, particularly studies focusing on urban grassroots (White & Stirling, Citation2013), spatial (Valderrama Pineda et al., Citation2017) and energy (Hodson & Marvin, Citation2009) contexts address complex socio-political dynamics related to those identified in temporary use.

Various types of actors can be understood as intermediaries. Examples include national-level organizations, independent professional actors (including architects) and small-scale civic networks (Fischer & Guy, Citation2009; Hyysalo et al., Citation2018; Kivimaa et al., Citation2019a). Moss asserts that a commonality of different intermediaries is the ‘relational nature of their work’ (Citation2009, p. 1481). Hodson et al. further describe such actors as ‘mediating’ between multiple actors and interests across levels and scales (Citation2013, p. 1408). Despite such commonalities, Kivimaa et al. point out that different types of intermediary actors and activities are needed in different transition phases (Citation2019b) and levels (Citation2019a). The scope of action of intermediaries may further vary depending on conditions such as their funding source, organization size, affiliation or the duration of their involvement (Kivimaa, Citation2014; Mignon & Kanda, Citation2018).

Scholars have identified a wide range of roles and activities by which intermediaries can contribute to urban transitions processes. There is increasing evidence of their roles in advancing niche development. For example, Hargreaves et al. (Citation2013) recognize intermediaries as important in sustaining and consolidating grassroots innovations that are particularly vulnerable and struggling within regime conditions. Kivimaa (Citation2014) analyzes intermediaries’ roles in energy transitions, identifying how they advance niche development through articulating visions, building social networks and contributing to learning. Geels and Deuten (Citation2006) highlight the role of intermediaries in aggregating knowledge to make niches more robust. Yet, other scholars emphasize the need to better understand the diverse, conflicted realities of local niches (Hargreaves et al., Citation2013; Seyfang et al., Citation2014).

In transitions literature, niche development is perceived to stimulate change within regimes, potentially contributing to their ‘reconfiguration’ or ‘destabilization’ (e.g. Geels, Citation2012). Yet, fewer studies have explicitly addressed the intermediaries’ roles in destabilizing regimes. Smith et al. (Citation2016) assert that intermediaries can take an antagonistic stance to reveal and potentially transform regime structures. Intermediaries are identified to contribute to regime change by ‘destabilizing regime rules’ (Matschoss & Heiskanen, Citation2018) and ‘alleviating institutional barriers’ (Warbroek et al., Citation2018, p. 2). Hargreaves et al. (Citation2013, p. 877) also recognize their role in ‘brokering’ between niche and regime. Furthermore, Hodson et al. (Citation2013) suggest that intermediary work can range across strategic and project-focused roles.

The emphasis on niche empowerment, regime change and destabilization in the literature reflects underlying normative values but also suggests that transition intermediaries are not always neutral middle actors. Instead, they may strongly advocate specific goals (e.g. Orstavik, Citation2014). Nevertheless, their agency to influence change varies based on, for example, their affiliation and resources (Kivimaa, Citation2014; Parag & Janda, Citation2014).

My analysis of intermediary roles focused on the terminology describing roles and activities across the above-mentioned literature. A shortcoming in the literature was that some terms describing roles remained rather abstract due to a lack of empirical detail. To assess such terminology in the temporary use context, I examined the roles vis-à-vis the case of Kera through an integrative analysis (see Materials and Methods).

A Typology of Roles in (Inter)mediation

As a result of an integrative analysis across the literature on intermediary roles and the temporary use case, Kera, I propose a typology of roles in (inter)mediation. The typology outlines six role categories, divided into sub-categories of activities, in line with the above-mentioned definition of roles. The roles are differentiated by their emphasis on niche development vs regime change and a project-oriented vs strategic purpose. The vocabulary in the typology follows that in the urban transitions literature. The empirical case has influenced the assessment of the terms and the differentiation of specific role and activity categories in the typology. The roles and accompanying activities are overviewed below and described in detail in , with all references.

The role of Aligning visions (a) is understood to concern articulating shared visions across niches (Seyfang et al., Citation2014) and negotiating broader-scale visions (Hodson & Marvin, Citation2009), also linked to efforts to destabilize regimes (Kivimaa, Citation2014). Thus, this role concerns vision alignment across levels and scales. This role comprises activities of negotiating visions and strategies, articulating needs and expectations and advancing sustainability aims.

Building social networks to support niches (b) is a socially complex role. In transitions literature, network-building is understood as central for niche development (e.g. Kivimaa, Citation2014; Seyfang et al., Citation2014), while the social interactions may also involve regime actors. This role involves activities of building networks and facilitating collaboration, gatekeeping as well as configuring, arbitrating and aligning interests.

Brokering partnerships between niche and regime (c) is a role through which intermediaries can introduce new actor configurations that may disrupt existing power relations and conventional practices (Hargreaves et al., Citation2013; Matschoss & Heiskanen, Citation2017, Citation2018; Warbroek et al., Citation2018). The role involves bridging value-based gaps and building trust between actors involved. Other activities include coordinating partnerships, elaborating terms and conditions and developing new models (e.g. business or operational).

Negotiating regime change (d) articulates a role through which intermediaries may explicitly address structural barriers for change and elaborate related ‘regime rules’ and institutions (Smith et al., Citation2016; Matschoss & Heiskanen, Citation2018; Warbroek et al., Citation2018). ‘Rules’ are understood here as regulations, permissions or institutional practices. Activities include negotiating ‘regime rules’, redeveloping institutions and advocating policy development.

The role of advancing learning (e) is also understood as key in niche development (e.g. Geels & Deuten, Citation2006). This role comprises activities of gathering and aggregating knowledge across local contexts, communicating and disseminating and capacity building (Hargreaves et al., Citation2013; Kivimaa, Citation2014; Seyfang et al., Citation2014). Other activities include experimenting and piloting as well as promoting niches via inspiring examples (Kivimaa, Citation2014; Matschoss & Heiskanen, Citation2017).

Coordinating project activities and resources (f) is the most neutral role in this typology (Geels & Deuten, Citation2006; Hargreaves et al., Citation2013; Warbroek et al., Citation2018). The accompanying activities include project design, coordination and evaluation and managing and identifying financial and human resources.

The proposed typology outlines a broad scope of potentially relevant roles and activities in (inter)mediation, assessed for their relevance in temporary use. The roles are not mutually exclusive nor exhaustive. Neither are they intended as a universal ‘job description’ in (inter)mediation. Instead, they present a range of potential roles, the combination of which may vary across individual cases and contexts of (inter)mediation. The following section further elucidates selected roles in the case of Kera in more detail.

Elucidating Mediator Roles in Case Kera

To bring to light nuances of temporary use mediation on the ground, vis-à-vis the typology overviewed above, this section elucidates selected roles in the Finnish temporary use case, Kera. The accounts below illustrate selected roles from the typology that resonate strongly with the case. In Kera, mediation focused largely on addressing the challenging socio-political dynamics between and within niche and regimes during an initial phase of temporary use. The case thus resonated most with the roles of building social networks (b) and brokering partnerships between niche and regime (c). Below, I illustrate these roles and related activities and instances of mediation in Kera. Furthermore, displays all activity categories from the case with the typology.

Conditions and Dynamics in Case Kera

The Temporary Kera project (2016–18) took place in a suburban office and logistics district in the city of Espoo, located in the Helsinki metropolitan area in Finland. The district was facing a growing vacancy problem; its buildings were outdated but in reasonably good condition. I was commissioned as a mediator in the project by a coalition of municipal culture and urban development departments in Espoo. The commissioner’s goal was to initiate agile, bottom-up revitalization of the underused properties before plans for longer-term redevelopment were implemented.

The conditions for mediation in the case were constrained by several factors, including the available budget and project brief negotiated with the commissioner, but also the local regulatory and planning context and the involved regime actors’ values and motivations. Concerning the planning and regulatory regimes, cities in the Helsinki area have had a tradition of stringent zoning and regulatory practices. In Kera, building regulations were not directly a barrier for temporarily repurposing the vacant spaces. Instead, it was a question of interpreting technical requirements in some of the buildings. Moreover, the permissions for repurposing spaces within the zoning plan involved high transaction costs, which were a barrier for individual users. Nevertheless, the commissioner representatives had ambitions to challenge some of the conventions in planning and development. They actively advocated swift concrete actions for initiating urban transformation with local actors, putting hope in temporary use to experiment with such an approach in practice.

Actors in the real-estate regime in Kera were private property owners, including leading Finnish property investment companies and local subsidiaries of international property investors. The property owners were rather skeptical of temporary use as a relatively unfamiliar approach in the Finnish real-estate sector. Consequently, the potential temporary users, here understood as niche actors, had faced great difficulty finding affordable spaces. This group included individual artists, event organizers and sports associations – quite unequal as negotiation partners with the corporate property owners. Thus, the socio-political dynamics in the case were characterized by asymmetric power relations, mismatching motivations and values and social and economic distance between actors.

Therefore, initiating temporary use in Kera can be seen as emblematic of niche-regime contestations in a Finnish temporary use context. A key challenge was to find ways to initiate temporary use within conditions dominated by real-estate and planning regimes.

Elucidating Selected Mediator Roles in Case Kera

Building Social Networks to Support Niches (b)

Addressing social dynamics to support temporary use was an important part of mediation work in Kera. This work entailed building networks of temporary users and facilitating their collaboration (b1). Other activities were gatekeeping (b2) to select participants and partners, configuring selection criteria, aligning interests and arbitrating between actors or actor groups (b3).

Building Social Networks and Facilitating Collaboration (b1)

As a mediator, my work concerning network-building and collaboration involved organizing and facilitating workshops and meetings and matchmaking between potential users.

While planning the project, I organized and facilitated a kick-off workshop, in which 50 people participated. The workshop took place in one of the underused buildings, where we planned to pilot temporary use. The workshop helped to identify interested users and their needs concerning spaces. However, the owner of the building soon withdrew from the project, and mediation continued with negotiations with other property owners (see c1).

Over a longer timeframe, matchmaking took over as a time-consuming priority. As the property owners were concerned about the workload of renting small office units to individuals, I helped users build groups to rent larger units together. In public viewings, I mapped the interested users’ needs and interests while also encouraging them to become proactive in group-building. The matchmaking work took place over months, involving complicated social dynamics, numerous meetings, phone calls and group emails. This process also revealed critical gaps concerning the need for an ‘operator’ to manage rental contracts (see c3) and a flexible rental model (see c5).

Configuring, Arbitrating and Aligning Interests (b3)

Besides network-building, mediation work in Kera involved configuring and aligning interests between actor groups and arbitrating conflicts between temporary users competing over funding or specific spaces.

Aligning interests between the municipal commissioner, the property owners and the potential users became necessary while framing the temporary use project and activities. While I prepared suggestions based on background research, decision-making entailed aligning the priorities of municipal representatives and property owners with the needs of the potential users. Although cultural actors and artists were the main groups interested in the available spaces, some property owners were quite prejudiced towards them, and the commissioner representatives were indecisive about their priorities. The local CEO of an international property investment company explained their worries about the existing tenants’ response towards ‘hipsters’, arguing ‘we don’t want to lose the foundations of our rental income.’ Consequently, artists had faced great difficulty with finding workspaces, as a ceramic artist reported: ‘Most of them [owners] said we weren’t suitable tenants. That left us feeling that this [project] would be our only chance to find a studio space … I think it was your [the mediator’s] engagement that made this [rental agreement] possible.’ My contribution as a mediator was to find a compromise between actors to enable first temporary use experiments, which might generate further learning.

Brokering Partnerships between Niche and Regime (c)

Besides addressing the social dynamics to support temporary use, another key mediator role focused on brokering partnerships between niche and regime actors to alleviate initial barriers for temporary use. I understand ‘partnerships’ here as contracts and agreements (such as rental contracts), funding or collaboration partnerships. In Kera, brokering work involved bridging value-based gaps (c1) in negotiations with property owners, introducing new actor configurations (c2) and coordinating partnerships (c3). The experiences also revealed a need to develop new rental models (c5) and elaborate related terms and contracts (c4).

Bridging Value-based Gaps and Building Trust (c1)

To enable new partnerships in Kera, mediation work involved negotiating with property owners and other actor groups to address controversies and develop shared understandings and compromises. Furthermore, translating and communicating needs and requirements was necessary to bridge the distance and build trust between actors and actor groups.

Negotiating with property owners took over as an essential priority after one of the most prominent property owners had withdrawn from the project due to air conditioning problems. Despite growing vacancy, most property owners were skeptical about temporary use and reluctant to find new ways for addressing the issue. Instead, their primary concern was the longer-term redevelopment of the underused properties. The owners presumed that temporary use would generate extra work, risks and added maintenance costs without enough financial profit – as one rental manager put it, ‘terrible costs, little income and a lot of trouble’.

The negotiations with owners also revealed a critical structural issue concerning real-estate valuation. As the prevailing valuation model is based on rental income, holding spaces empty maintains property value while lowering the rents would decrease the value – on paper. One of the rental managers explained: ‘People always argue that the property owner would earn at least some rent so it would be better than nothing, which is not true in terms of real-estate valuation … Have you thought about this … is the valuation model wrong?’

Other actors, including the municipal project leaders, argued instead for the potential of temporary use to increase property value in the longer term, claiming that the current valuation model is indeed problematic. While I had limited agency as a freelance consultant to influence the property owners’ decisions, the municipal project leaders generated pressure towards temporary use by withholding longer-term redevelopment permissions for even five years. Through negotiations, two property owners agreed to test small-scale temporary rental.

Introducing New Actor Configurations (c2)

A significant gap identified in Kera was the lack of a specific actor to operate rental contracts and payments and possibly create a joint marketing and booking platform. Such activities were beyond the scope of my work, due to the specific legal requirements attached to ‘real-estate agents’ and the potential longer-term commitment extending beyond my contract. Therefore, I searched for potential operators and introduced these actors to property owners. An organization specialized in operating ateliers for professional artists took over the operational task in one of the buildings. However, negotiations with other actors, such as startups, did not result in collaboration with owners.

Coordinating Partnerships (c3)

Having developed an agreement with two property owners in Kera to test small-scale temporary rental, I continued marketing the spaces while looking for a professional operator.

Within the small project budget, I advertised spaces via social media and public events that were part of the project. I arranged public viewings together with the rental managers. This work took time and involved complex dynamics in matchmaking between users (see b1). Within six months, I found groups of users within the fields of arts, culture and sports for three office premises and a larger, 3000 m2 warehouse space. To enable the renting of larger spaces for individual users without an operator, I resorted to substitute solutions, such as helping users found an association (‘ry’ in Finnish) to act as the formal main tenant. This solution had many problems, including risks and responsibilities for association members. Nevertheless, such experiences provided learning for the potential development of future models in temporary use.

Developing New Models (c5)

In Kera, the property owners’ traditional operational models did not easily accommodate temporary use. Hence, there was a need for developing a flexible rental model. Based on my previous research and the experiences within Kera, I developed a proposal for such a model, including a step-by-step system to start renting parts of larger spaces for an initial period while still looking for more tenants. The owners, however, deemed the proposal too risky. Instead, we agreed on smaller adjustments to contract terms and conditions concerning rental and deposit prices, contract duration or included renovations.

Discussion and Conclusions

‘Mediation’ is emerging as a field of professional work that addresses the complex socio-political dynamics and structural barriers identified in temporary use. This article has sought to contribute to the research in this understudied and undertheorized field by articulating the roles and activities involved in mediating temporary use.

As a result of an integrated analysis across literature on urban transition intermediaries and temporary use practice, I have proposed a typology of roles in (inter)mediation. The typology outlines six mediation-related roles and comprising activities, tested concerning practice-relevance in temporary use and differentiated into levels and categories. The roles range from learning, network-building and brokering to aligning visions and renegotiating ‘regime rules’ involved in planning and development. Thus, the typology suggests a broad range of potentially relevant mediator roles, the scope of which may vary depending on local contexts and conditions of temporary use.

Through a Finnish temporary use case, Kera, I have further elucidated nuances of selected roles in practice. The empirical accounts have shed light on socio-politically complex mediator roles in initiating temporary use in a local context, where mediation entailed building social networks, aligning interests and brokering between actors to enable temporary use. Regarding the typology, the case strongly demonstrates the roles of network-building and brokering while providing more subtle evidence on other roles concerning learning or regime change. This may be partly due to the limited scope of the case, as further discussed below.

The case further demonstrates the nature of the roles as evolving and negotiated in interaction with other actors, as suggested by Wittmayer et al. (Citation2017). In Kera, the content and scope of the mediator roles were negotiated continuously with the project commissioner. The scope of roles was limited in terms of resources and my short-term involvement as a freelance consultant. Yet, the roles also changed from our initially agreed understandings due to actions and decisions by the property owners and the commissioner’s changing perceptions.

There are inevitable delimitations concerning the typology and the role of a single case in this study. Firstly, it has been beyond the scope of this article to delve deeply into the theoretical foundations of the main sources and the temporary use and urban transitions discourses. Secondly, methodological limits concern the above discussed ‘partiality’ and ‘situatedness’ of the practice-based research approach and the role of the single case, which sets some limits for interpreting the implications. Here, the case of Kera represents an initial phase of temporary use in a local context, characterized by a mismatch of interests between key actors and a strong position of the private property owners. Inevitably, mediation in other cases, contexts or phases of temporary use will involve other context-specific characteristics. Nevertheless, the nuanced elaboration of the contextual conditions here is relevant for understanding mediation roles in challenging strong, conventional planning and real-estate regimes. Moreover, the typology itself is based on a broad literature review and thus intended as applicable on temporary use mediation across local contexts.

Thirdly, the integrated analysis indicated potential gaps in the scope of roles in the typology vis-á-vis temporary use. While the case demonstrated all roles of the typology to varying degrees, it also revealed some activities that did not perfectly match the typology. This indicates that some new roles or activities might potentially be added or some terms reformulated based on further empirical studies on temporary use. However, my decision here was not to add new categories or alter the terms in the typology, based on one case.

Given these limitations, the typology proposed in this article is not intended as closed or finalized. Recommended future research would include expanding the study of mediation to other cases of temporary use, involving different geographical contexts and regime conditions, different phases of temporary use, or other research methods. Future work could also include a deeper theoretical grounding of the typology itself or seeking additional literature in other disciplines possibly relevant for further theorizing such mediator roles.

Through a systematic and nuanced articulation of (inter)mediation roles in temporary use, this article draws attention to changing work in planning, where mediation is an example of distinctly dialogic and socio-politically engaged work. Such work extends beyond the traditional, largely spatially-oriented competencies and training of professionals involved. By elaborating related roles and competencies, this article provides important implications for municipalities aiming to procure such work and for the future development of professional education in planning or architecture.

A better understanding of mediation can be important for cities aiming to develop more adaptive, inclusive and resource-efficient approaches in urban planning and development. Closer attention to the complexity of interests through mediation might increase the recognition and representation of niche actors, such as the temporary users. As implied in urban transitions scholarship, (inter)mediation involved in negotiating structural conditions or building new partnerships between niche and regime might ultimately open up avenues for temporary use to challenge the real-estate and planning regimes in more profound ways. This would make more concrete the claims by scholars on the potential of temporary use in advancing systemic changes in planning and development (e.g. Oswalt et al., Citation2013). Overall, the integrated analytic work proposed in this article is a necessary first step in mapping out a previously understudied area, and thus, a basis for further research.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to my advisor Ramia Mazé for support and comments throughout the process and my supervisor Mikko Jalas for comments. I also thank my colleagues Elif Erdoğan Öztekin and Satu Lähteenoja for comments. I particularly thank the anonymous reviewers for their thorough and constructive feedback and Felicity Kjisik for language editing. Moreover, I thank the commissioner of the Temporary Kera project and all the participants for agreeing to participate in this research. All quotations from the case are translated from Finnish by the author.

Disclosure Statement

Part of this research was conducted as a practice-based study, in which I investigated my work as a mediator commissioned in the project Temporary Kera. I am reporting that I received a fee covering my project work from the city of Espoo (the project commissioner). The research work, including data collection, analysis, literature review and writing, was funded separately, as mentioned below. In agreement with the project commissioner, I carried out the research work independently, guided by separate research objectives. I have disclosed these interests fully to Taylor & Francis, and have an approved plan for managing any potential conflicts arising from this involvement.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. This article forms part of my doctoral research, in which I study mediation through the ‘practice-based research’ of my own work as an architect mediating temporary use in Finland and through qualitative interviews with other professional mediators.

2. The term ‘transitions research’ refers here to the field of scholarship studying long-term socio-technical transitions (e.g. Geels & Schot, Citation2010). The field borrows insights from various disciplines, including science and technology studies, evolutionary economics, sociology and institutional theory. Recently, transitions thinking has been applied in a broad range of disciplines. ‘Urban sustainability transitions’ draws on both socio-technical and socio-ecological system studies (e.g. Berkes et al., Citation2002).

3. Quotation from a participant at a meeting in the case Kera.

References

- Andres, L. (2013) Differential spaces, power hierarchy and collaborative planning: A critique of the role of temporary uses in shaping and making places, Urban Studies, 50(March), pp. 759–775. doi:10.1177/0042098012455719.

- Andres, L., & Kraftl, P. (2021) New directions in the theorisation of temporary urbanisms: Adaptability, activation and trajectory, Progress in Human Geography, 45, pp. 1237–1253. preprint. (accessed 26 October 2021). doi:10.1177/0309132520985321.

- Baum, J. A. C., Calabrese, T., & Silverman, B. S. (2000) Don’t go it alone: Alliance network composition and startups’ performance in Canadian biotechnology, Strategic Management Journal, 21(3), pp. 267–294. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0266(200003)21:3<267::AID-SMJ89>3.0.CO;2-8.

- Berkes, F., Colding, J., & Folke, C. (Eds) (2002) Navigating Social-Ecological Systems (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

- Berwyn, E. (2012) The meanwhile plinth, in: M. Glaser, M. van’t Hoff, H. Karssenberg, J. Laven, & J. van Teeffelen (Eds) The City at Eye Level: Lessons for Street Plinths, pp. 143–147 (Delft: Eburon).

- Bishop, P., & Williams, L. (2012) The Temporary City (London: Routledge).

- Bosák, V., Slach, O., Nováček, A., & Krtička, L. (2020) Temporary use and brownfield regeneration in post-socialist context: From bottom-up governance to artists exploitation, European Planning Studies, 28(3), pp. 604–626. doi:10.1080/09654313.2019.1642853.

- Buijs, A. E., Mattijssen, T. J., Van der Jagt, A. P., Ambrose-Oji, B., Andersson, E., Elands, B. H., & Steen Møller, M. (2016) Active citizenship for urban green infrastructure: Fostering the diversity and dynamics of citizen contributions through mosaic governance, Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 22, pp. 1–6. doi:10.1016/j.cosust.2017.01.002.

- Bulkeley, H., Broto, V. C., Hodson, M., & Marvin, S. (2011) Cities and Low Carbon Transitions (New York: Routledge).

- Christmann, G. B., Ibert, O., Jessen, J., & Walther, U. J. (2020) Innovations in spatial planning as a social process – Phases, actors, conflicts, European Planning Studies, 28(3), pp. 496–520. doi:10.1080/09654313.2019.1639399.

- Collier, P., & Callero, P. (2005) Role theory and social cognition: Learning to think like a recycler, Self and Identity, 4(1), pp. 45–58. doi:10.1080/13576500444000164.

- Colomb, C. (2012) Pushing the urban frontier: Temporary uses of space, city marketing, and the creative city discourse in 2000s Berlin, Journal of Urban Affairs, 34(2), pp. 131–152. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9906.2012.00607.x.

- De Fejter, A. (2017) Building bridges to cross-over: Neighbourhood managers playing a brokerage role between stakeholders involved in temporary use, in: F. Jégou & M. Bonneau (Eds) Brokering between Stakeholders Involved in Temporary Use Refill Magazine #2, pp. 12–15 (Ghent: Refill).

- de Roo, G., & Boelens, L. (Eds) (2016) Spatial Planning in a Complex Unpredictable World of Change (Groningen: Coöperatie in Planning UA).

- Dotson, T. (2016) Trial-and-error urbanism: Addressing obduracy, uncertainty and complexity in urban planning and design, Journal of Urbanism, 9(2), pp. 148–165.

- Filion, P. (2010) Reorienting urban development? Structural obstruction to new urban forms, International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 34(1), pp. 1–19. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2427.2009.00896.x.

- Fischer, J., & Guy, S. (2009) Re-interpreting regulations: Architects as intermediaries for low-carbon buildings, Urban Studies, 46(12), pp. 2577–2594. doi:10.1177/0042098009344228.

- Frantzeskaki, N., Castán Broto, V., Coenen, L., & Loorbach, D. (Eds) (2017) Urban Sustainability Transitions (New York and Oxon: Routledge).

- Frantzeskaki, N., Dumitru, A., Anguelovski, I., Avelino, F., Bach, M., Best, B., Binder, C., Barnes, J., Carrus, G., Egermann, M., Haxeltine, A., Moore, M. L., Mira, R. G., Loorbach, D., Uzzell, D., Omman, I., Olsson, P., Silvestri, G., Stedman, R., Wittmayer, J., Durrant, R., & Rauschmayer, F. (2016) Elucidating the changing roles of civil society in urban sustainability transitions, Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 22, pp. 41–50. doi:10.1016/j.cosust.2017.04.008.

- Fuenfschilling, L., & Truffer, B. (2014) The structuration of socio-technical regimes - Conceptual foundations from institutional theory, Research Policy, 43(4), pp. 772–791. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2013.10.010.

- Galdini, R. (2020) Temporary uses in contemporary spaces. A European project in Rome, Cities, 96, pp. 1–8. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2019.102445.

- Gebhardt, M. F. (2017) Planning, property rights and the tragedy of the anticommons: Temporary uses in Portland and Detroit, in: J. Henneberry (Ed) Transience and Permanence in Urban Development, pp. 171–184 (Oxford: Wiley).

- Geels, F. W. (2002) Technological transitions as evolutionary reconfiguration processes: A multi-level perspective and a case-study, Research Policy, 31(8–9), pp. 1257–1274. doi:10.1016/S0048-7333(02)00062-8.

- Geels, F. W. (2004) From sectoral systems of innovation to socio-technical systems: Insights about dynamics and change from sociology and institutional theory, Research Policy, 33(6–7), pp. 897–920. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2004.01.015.

- Geels, F. W., Kern, F., Fuchs, G., Hinderer, N., Kungl, G., Mylan, J., Neukirch, M., & Wassermann, S. (2016). The enactment of socio-technical transition pathways: A reformulated typology and a comparative multi-level analysis of the German and UK low-carbon electricity transitions (1990-2014), Research Policy, 45, 869–913.

- Geels, F. W., & Schot, J. (2010) The dynamics of transitions: A socio-technical perspective, in: J. Grin, J. Rotmans, & J. Schot (Eds) Transitions to Sustainable Development: New Directions in the Study of Long Term Transformative Change, pp. 11–102 (New York and London: Routledge).

- Geels, F. W. (2011) The multi-level perspective on sustainability transitions: Responses to seven criticisms, Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 1(1), pp. 24–40. doi:10.1016/j.eist.2011.02.002.

- Geels, F. W. (2012) A socio-technical analysis of low-carbon transitions: Introducing the multi-level perspective into transport studies, Journal of Transport Geography, 24, pp. 471–482. doi:10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2012.01.021.

- Geels, F. W., & Deuten, J. J. (2006) Local and global dynamics in technological development: A socio-cognitive perspective on knowledge flows and lessons from reinforced concrete, Science and Public Policy, 33(4), pp. 265–275. doi:10.3152/147154306781778984.

- Gray, C., & Malins, J. (2004) Visualising Research: A Guide to the Research Process in Art and Design (London and New York: Routledge).

- Groth, J., & Corijn, E. (2005) Reclaiming urbanity: Indeterminate spaces, informal actors and urban agenda setting, Urban Studies, 42(3), pp. 503–526. doi:10.1080/00420980500035436.

- Hammersley, M., & Atkinson, P. (2007) Ethnography: Principles in Practice, 3rd ed. (London and New York: Routledge).

- Haraway, D. (1988) Situated knowledges: The science question in feminism and the privilege of partial perspective, Feminist Studies, 14(3), pp. 575. doi:10.2307/3178066.

- Harding, S. (Ed) (2011) The Postcolonial Science and Technology Studies Reader (Durham and London: Duke University Press).

- Hargreaves, T., Hielscher, S., Seyfang, G., & Smith, A. (2013) Grassroots innovations in community energy: The role of intermediaries in niche development, Global Environmental Change, 23, pp. 868–880. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2013.02.008.

- Hasemann, O., Schnier, D., Angenendt, A., Oßwald, S., & Bremen, Z. (Eds) (2017) Building Platforms (Berlin: Jovis Verlag).

- Haydn, F., & Temel, R. (2006) Temporary Urban Spaces: Concepts for the Use of City Spaces (Basel: Birkhäuser).

- Henneberry, J. (Ed) (2017) Transience and Permanence in Urban Development Transience and Permanence in Urban Development (Oxford: Wiley).

- Hernberg, H. (2014) Tyhjät Tilat: Näkökulmia ja keinoja olemassa olevan rakennuskannan uusiokäyttöön [Vacant Spaces: Perspectives to Reusing Existing Built Environment] (Helsinki: Ministry of the Environment).

- Hernberg, H. (2020) Mediating ‘Temporary use’ of urban space: Accounts of selected practitioners, in: M. Chudoba, A. Hynynen, M. Rönn, & A. E. Toft (Eds) Built Environment and Architecture as a Resource, Proceedings Series 2020-1, pp. 211–239 (Sweden: Nordic Academic Press of Architectural Research).

- Hernberg, H., & Mazé, R. (2017) Architect/designer as ‘Urban agent’ – A case of mediating temporary use in cities, in: Proceedings of NORDES Nordic Design Research Conference 2017 Design + Power, June 15–17, Oslo, Norway.

- Hodson, M., & Marvin, S. (2009) Cities mediating technological transitions: Understanding visions, intermediation and consequences, Technology Analysis and Strategic Management, 21(4), pp. 515–534. doi:10.1080/09537320902819213.

- Hodson, M., Marvin, S., & Bulkeley, H. (2013) The intermediary organisation of low carbon cities: A comparative analysis of transitions in Greater London and Greater Manchester, Urban Studies, 50(7), pp. 1403–1422. doi:10.1177/0042098013480967.

- Honeck, T. (2017) From squatters to creatives. An innovation perspective on temporary use in planning, Planning Theory and Practice, 18(2), pp. 268–287. doi:10.1080/14649357.2017.1303536.

- Howells, J. (2006) Intermediation and the role of intermediaries in innovation, Research Policy, 35(5), pp. 715–728. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2006.03.005.

- Hyysalo, S., Juntunen, J. K., & Martiskainen, M. (2018) Energy Internet forums as acceleration phase transition intermediaries, Research Policy, 47(5), pp. 872–885. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2018.02.012.

- Jegou, F., & Bonneau, M. (Eds) (2017) Brokering between Stakeholders Involved in Temporary Use Refill Magazine #2 (Ghent: Refill).

- Jégou, F., Bonneau, M., & Tytgadt, E. (Eds) (2018) A Journey Through Temporary Use (Ghent: Refill).

- Kivimaa, P. (2014) Government-affiliated intermediary organisations as actors in system-level transitions, Research Policy, 43(8), pp. 1370–1380. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2014.02.007.

- Kivimaa, P., Boon, W., Hyysalo, S., & Klerkx, L. (2019a) Towards a typology of intermediaries in sustainability transitions: A systematic review and a research agenda, Research Policy, 48, pp. 1062–1075. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2018.10.006.

- Kivimaa, P., Hyysalo, S., Boon, W., Klerkx, L., Martiskainen, M., & Schot, J. (2019b) Passing the baton: How intermediaries advance sustainability transitions in different phases, Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 31, pp. 110–125. doi:10.1016/j.eist.2019.01.001.

- Kvale, S., & Brinkmann, S. (2009) Interviews, Learning the Craft of Qualitative Research Interviewing, 2nd ed. (London: SAGE).

- Lehtovuori, P., & Ruoppila, S. (2012) Temporary uses as means of experimental urban planning, Serbian Architecture Journal, 4(1), pp. 29–54. doi:10.5937/SAJ1201029L.

- Loorbach, D., Frantzeskaki, N., & Avelino, F. (2017) Sustainability transitions research: Transforming science and practice for societal change, Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 42(1), pp. 599–626. doi:10.1146/annurev-environ-102014-021340.

- Madanipour, A. (2018) Temporary use of space: Urban processes between flexibility, opportunity and precarity, Urban Studies, 55(5), pp. 1093–1110. doi:10.1177/0042098017705546.

- Matoga, A. (2019) Governance of temporary use, Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers: Urban Design and Planning, 172(4), pp. 159–168.

- Matschoss, K., & Heiskanen, E. (2017) Making it experimental in several ways: The work of intermediaries in raising the ambition level in local climate initiatives, Journal of Cleaner Production, 169, pp. 85–93. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.03.037.

- Matschoss, K., & Heiskanen, E. (2018) Innovation intermediary challenging the energy incumbent: Enactment of local socio-technical transition pathways by destabilisation of regime rules, Technology Analysis and Strategic Management, 30(12), pp. 1455–1469. doi:10.1080/09537325.2018.1473853.

- Mignon, I., & Kanda, W. (2018) A typology of intermediary organizations and their impact on sustainability transition policies, Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 29, pp. 100–113. doi:10.1016/j.eist.2018.07.001.

- Moss, T. (2009) Intermediaries and the governance of sociotechnical networks in transition, Environment and Planning A, 41(6), pp. 1480–1495. doi:10.1068/a4116.

- Németh, J., & Langhorst, J. (2014) Rethinking urban transformation: Temporary uses for vacant land, Cities, 40, pp. 143–150. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2013.04.007.

- Orstavik, F. (2014) Innovation as re-institutionalization: A case study of technological change in housebuilding in Norway, Construction Management and Economics, 32(9), pp. 857–873. doi:10.1080/01446193.2014.895848.

- Oswalt, P., Overmeyer, K., & Misselwitz, P. (2013) Urban Catalyst - the Power of Temporary Use (Berlin: DOM Publishers).

- Parag, Y., & Janda, K. B. (2014) More than filler: Middle actors and socio-technical change in the energy system from the ‘middle-out’, Energy Research and Social Science, 3, pp. 102–112. doi:10.1016/j.erss.2014.07.011.

- Patti, D., & Polyak, L. (2017) Frameworks for temporary use: Experiments of urban regeneration in Bremen, Rome and Budapest, in: J. Henneberry (Ed) Transience and Permanence in Urban Development, pp. 231–248 (Oxford: Wiley).

- Patti, D., & Polyak, L. (2015) From practice to policy: Frameworks for temporary use, Urban Research & Practice, 8(1), pp. 122–134. doi:10.1080/17535069.2015.1011422.

- Raven, R., Van Den Bosch, S., & Weterings, R. (2010) Transitions and strategic niche management: Towards a competence kit for practitioners, International Journal of Technology Management, 51(1), pp. 57–74. doi:10.1504/IJTM.2010.033128.

- Rubenis, M. (2017) ‘Free Riga’: Space offer -driven brokering between owners and initiatives, in: F. Jégou & M. Bonneau (Eds) Brokering between Stakeholders Involved in Temporary Use Refill Magazine #2, pp. 23–27 (Ghent: Refill).

- Saldaña, J. (2009) The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers (London: SAGE Publications).

- Schot, J., & Geels, F. W. (2008) Strategic niche management and sustainable innovation journeys: Theory, findings, research agenda, and policy, Technology Analysis and Strategic Management, 20(5), pp. 537–554. doi:10.1080/09537320802292651.

- Seyfang, G., Hielscher, S., Hargreaves, T., Martiskainen, M., & Smith, A. (2014) A grassroots sustainable energy niche? Reflections on community energy in the UK, Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 13(2014), pp. 21–44. doi:10.1016/j.eist.2014.04.004.

- Simpson, B., & Carroll, B. (2008) Re-viewing ‘role’ in processes of identity construction, Organization, 15(1), pp. 29–50. doi:10.1177/1350508407084484.

- Smith, A., Fressoli, M., & Thomas, H. (2014) Grassroots innovation movements: Challenges and contributions, Journal of Cleaner Production, 63, pp. 114–124. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2012.12.025.

- Smith, A., Hargreaves, T., Hielscher, S., Martiskainen, M., & Seyfang, G. (2016) Making the most of community energies: Three perspectives on grassroots innovation, Environment and Planning A, 48(2), pp. 407–432. doi:10.1177/0308518X15597908.

- Smith, A., & Raven, R. (2012) What is protective space? Reconsidering niches in transitions to sustainability, Research Policy, 41(6), pp. 1025–1036. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2011.12.012.

- Smith, A., Voß, J. P., & Grin, J. (2010) Innovation studies and sustainability transitions: The allure of the multi-level perspective and its challenges, Research Policy, 39(4), pp. 435–448. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2010.01.023.

- Stevens, Q., & Dovey, K. (2019) ‘Pop‐ups’ and public interests: Agile public space in the Neoliberal city, in: M. Arefi & C. Kickert (Eds) The Palgrave Handbook of Bottom-Up Urbanism, pp. 323–337 (New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan).

- Tonkiss, F. (2013) Austerity urbanism and the makeshift city, City, 17(3), pp. 312–324. doi:10.1080/13604813.2013.795332.

- Turner, R. H. (1990) Role change, Annual Review of Sociology, 16, pp. 87–110. doi:10.1146/annurev.so.16.080190.000511.

- Valderrama Pineda, A. F., Braagaard Harders, A. K., & Morten, E. (2017) Mediators acting in urban transition processes: Carlsberg city district and cycle superhighways, in: N. Frantzeskaki, V. Castán Broto, L. Coenen, & D. Loorbach (Eds) Urban Sustainability Transitions, pp. 300–310 (New York and Oxon: Routledge).

- van der Laak, W. W. M., Raven, R. P. J. M., & Verbong, G. P. J. (2007) Strategic niche management for biofuels: Analysing past experiments for developing new biofuel policies, Energy Policy, 35(6), pp. 3213–3225. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2006.11.009.

- Vaughan, L. (2017) Practice-based Design Research (London and New York: Bloomsbury).

- Warbroek, B., Hoppe, T., Coenen, F., & Bressers, H. (2018) The role of intermediaries in supporting local low-carbon energy initiatives, Sustainability (Switzerland), 10(7), pp. 1–28.

- White, R., & Stirling, A. (2013) Sustaining trajectories towards sustainability: Dynamics and diversity in UK communal growing activities, Global Environmental Change, 23, pp. 838–846. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2013.06.004.

- Wittmayer, J. M., Avelino, F., van Steenbergen, F., & Loorbach, D. (2017) Actor roles in transition: Insights from sociological perspectives, Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 24, pp. 45–56. doi:10.1016/j.eist.2016.10.003.

- Wolfram, M., Frantzeskaki, N., & Maschmeyer, S. (2016) Cities, systems and sustainability: Status and perspectives of research on urban transformations, Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 22, pp. 18–25. doi:10.1016/j.cosust.2017.01.014.