ABSTRACT

This paper presents a practical and pedagogical model of socially innovative planning based on four dialectical relations between actors, institutions and planning instruments that frame, constitute and position planning actions. The paper illustrates and evaluates this model by analysing four spatial planning studios that took place during the authors’ six-year long engagement in a heavily contested urban renewal project in the city of Antwerp, Belgium. The paper shows how a frame for critical inquiry helped to address changes in the studio and project realities. by understanding, experiencing and responding to the ethical and socio-environmental consequences of spatial planning practice.

1. A Relational Understanding of Planning

Social innovation research has a long tradition in deconstructing local planning practices as trajectories of socio-spatial transformation. More specifically, the territorial development approach, situated in the Euro-Canadian social innovation literature, helps to redefine the transformative nature of planning (see among others MacCallum et al., Citation2009; Moulaert et al., Citation2010, Citation2017; Moulaert & MacCallum, Citation2019; Moulaert & Mehmood, Citation2020). This approach conceptualises socially innovative practice as a way to ‘offer the means not only for meeting needs, but also for political mobilisation among vulnerable and marginalised communities. It has an explicit analytical focus on multi-level governance and institutional dynamics, as well as on the strategies and knowledge mobilised by socially innovative actors in particular contexts’ (Moulaert et al., Citation2017, p. 26).

A social innovation-inspired perspective on planning (for an overview see De Blust & Van den Broeck, Citation2019) starts from the social construction of planning as an institutionally embedded practice. Planning systems, their instruments and rules, are socially constructed and can be situated in the range between replicating a broader hegemonic socio-cultural and technical imaginary (Moulaert et al., Citation2007; Servillo, Citation2017) and supporting counter-hegemonic movements. Therefore they are always socio-political in their nature (Friedmann, Citation1992; Sandercock, Citation2003; Swyngedouw, Citation2008; Van den Broeck, Citation2008; Marcuse et al., Citation2009). In line with this planning perspective, strategic action is defined as a relational endeavour; it focuses on institutional difference and selectivity to determine critical room for manoeuvre (Moulaert & Mehmood, Citation2010). Through a deep analysis of how a certain initiative or strategy reveals and challenges the opportunities and constraints for a more equitable spatial transformation, one can understand the path dependency of the resources for (institutional) transformation and actively challenge them (Moulaert et al., Citation2007).

2. Socio-Environmental Justice as the Subject of Planning

Starting from a relational understanding of planning affects the way socio-environmental justice is approached. Social-environmental justice (Swyngedouw & Heynen, Citation2003; Parra, Citation2013; Velicu & Kaika, Citation2015) becomes defined through both the selectivity of institutional mechanisms and the design of the actual transformative action. Knowledge and action may be understood as dialectically interrelated (De Blust & Van den Broeck, Citation2019; Moulaert & MacCallum, Citation2019; Van Dyck et al., Citation2019). Through a process of collective problematisation (Novy, Citation2012; Miciukiewicz et al., Citation2012; Van den Broeck et al., Citation2016), the definition of socio-environmental justice in the goals, means and outcomes of planning practice is constantly revisited. ‘Rather than importing a universal principle of justice to apply in an act of final moral judgement’ (Lake, Citation2016, p. 1210), socio-environmental justice is defined through a process of collective situated moral inquiry, aimed at formulating a principle of justice to guide actions.

Creating the right learning environment for this collective situated moral inquiry is challenging (De Blust et al., Citation2021). This approach needs a mode of collective reflection that acknowledges both the experience of the practitioners engaged in an activity and the socio-political context in which the activity occurs. By collectively reflecting on individual learners’ experiences, students and involved actors become aware of the assumptions that undergird their thoughts, the strategic and tactical aspects of planning practice and how it defines their (collective) room for manoeuvre.

Such an approach is structured along three lines: (1) students learn from (past) experiences and translate lessons learned into possible reorientations of the used theories, methodologies and actions (Healey, Citation2009; Moulaert & Mehmood, Citation2014); (2) this allows for complexity, contradictions, multiple perspectives and opposing interests to unfold (Van Dyck et al., Citation2019; Van den Broeck et al., Citationin press), and (3) research is understood as part of the social reality in which the processes studied occur (Jessop et al., Citation2013).

In this paper, we introduce a frame for collective critical inquiry that operationalises this approach. After situating its development in a longer trajectory of action research, we describe its key dimensions and analyse how they were activated during four spatial planning studios that ran between 2014 and 2020 in the Department of Architecture at KU Leuven, during one semester (13 weeks) for 2–3 days per week.

3. The Co-Production of a Frame for Collective Critical Inquiry

The frame for collective critical inquiry has been co-constructed by planning studio teachers, planning students and studio case study stakeholders. It builds on the relational understanding of planning cum socio-environmental justice as summarised above and explored in some of the authors’ previous work. The frame is organised around four dialectical relations between actors, institutions and planning instruments that constitute and position planning actions (), including: (A) ‘actors and institutions expressed and examined in terms of each other, institutions in terms of action and action in terms of institutions’ (Van den Broeck, Citation2011, p. 54), (B) the restructured or reproduced institutional field, defining the field of action of future planning activities, (C) the reflexive-recursive dialectical interaction of actors and institutions reshaping institutional fields over time, and (D) the definition of socio-environmental justice in relation to this reflexive-recursive dialectical field. Together, these four dialectical relations define the field of action of a social innovation inspired planning practice.

Figure 1. Four dialectical relations in a field of actors organised in social groups, institutional frames and planning instruments (Source: Authors’ elaboration of Van den Broeck, Citation2011).

This frame evolved through the six-year process of studio making and has served as a situated and emerging meta-theoretical and analytical work. Its co-production implies that actors’ backgrounds, parallel learnings and events were influential. The frame continued to re-emerge from conversations, discussions and negotiations on how to design, build, implement etc. the planning studio and related planning process.

Given the international nature of the Master’s programme (comprising 10–15 students per studio), the students came from all continents and spanned a range of (four) generations. Neighbourhood and city stakeholders with various backgrounds were involved in defining the studio assignments, feeding the students with information and interpretations, giving students feedback at intermediate moments in the process, participating in workshops, and integrating some of the students’ work in their own actions. Over the course of the 6 years the studio was held, studio teachers, students and case study stakeholders discussed, negotiated and co-produced (sometimes consciously, other times intuitively) what a planning studio is or can/should be.

During the process, some practical pedagogical methods emerged that were meant to stimulate collective (self-)reflection. At the beginning of the studio students’ skills were mapped, and they were asked to either present a project that they valued or explore and narrate the story behind something that struck them during an introductory walk. Based on these small warm-up exercises an organisational group of students was formed taking care of the studio governance and the different moments of individual and collective self-reflection. These steps were framed in the overall philosophy of the studio to avoid defining the final output but rather negotiate the overall research question and conduct mid-reviews as stakeholder workshops where the final products of the studio are discussed and group and task structures are reshufflled to respond to reinterpretations of the assignment.

The studio process was structured around critical moments when decisions regarding the position of the students, the teachers and the studio as a whole vis-à-vis the studio case study and its stakeholders needed to be questioned, discussed, negotiated and redefined. Critical moments, for example, include stepping into an ongoing process; important actors entering or leaving the institutional field; crucial shifts happening in institutional frames; or fundamental changes in actors’ understanding of the field. At such moments, critical questions with high self-reflexive meaning and regarding socio-environmental justice explicitly came to the fore. Whose interests are we serving at this stage in the process? Which values are expressed in our research questions, theories, methodologies, analyses, invited stakeholders, collective reflections etc.? Should we reposition ourselves and if so, how? To support the exploration of these questions, and the choices to be made therein, the concept of reflective responses was introduced implying possible strategies that could be deployed as response to the critical moments traced during a process of collective critical inquiry (). Each of the four reflective responses operationalises how to deal with one of the four dialectical relations of a social innovation inspired understanding of planning as introduced above. The four reflective responses we distinguish are: (A) assessing power relations, structures and dynamics (B) navigating strategic alliances (C) combining collective problematisation and strategic action (D) building reflexive positionality. Before illustrating how these four reflective responses help to collectively deal with different critical moments in a shared case study, we further operationalise them in the following section.

4. Four Reflective Responses

4.1. Assessing Power Relations, Structures, and Dynamics Through Mapping the Socio-Technical Ensembles at Play

Planning instruments and visions are defined and constructed by their relevant social groups (transformative or conservative communities of practice, epistemic communities). This process is subject to continuous changes. Actors create, transform and/or reproduce instruments and institutional frames and imbue their interests and values. Institutional frames are selectively open to the actors’ strategies and tactics, depending on the specific interests and values inscribed in their social practices (Jessop, Citation2001, Citation2008). When engaging for the first time in a specific planning process or when new actors or instruments are introduced (critical moments), it becomes important to actively analyse and (re)evaluate the underlying configurations of power (reflective response).

This first reflective response highlights the need to continuously question the socio-political context of the planning project and understand who is gaining and losing from the development of land? Which dimensions of planning and development are crucial in these conflicts over socio-environmental justice? And what instruments and institutional mechanisms are key in sustaining these situations of inequality? By conducting interviews, mapping actors and relevant social groups, analysing institutional frames and their spatial structures planning actors may gradually reveal processes of socio-environmental injustice and opportunities for greater spatial equity, and construct a new narrative about the place and process at hand.

4.2. Navigating Strategic Alliances as a Constitutive Element for Action and Plan-Making

A social innovation inspired planning practice sees planning agents neither as the key actors nor the driving force of transformation, but as part of a larger gradually evolving strategic alliance and therefore supportive or not to the collective effort of others. Planning must be situated in a much larger field of social action, considering a large variety of intertwined agencies and their value systems, materialities, spatialities and temporalities. Defining planning strategies from this perspective becomes first of all a matter of situating practices in direct relation to shared concerns and (future) actions of others. Strategy-making engages with multiple and unexpected ways of transformation and cannot be narrowed down to making strategic plans per se (Healey, Citation2013).

In order to navigate in this wide and ever-changing set of alliances, the second reflective response stresses the need to always situate actions and strategies in relation to others. Questions such as ‘Who do I support with my intervention? How does this affect other actors? And can my intervention be used by other social groups to strengthen their claim … ?’ become key for thinking about the configuration and importance of various planning and design proposals and interventions. Both the form and content of interventions depend on the ability to reveal new institutional mechanisms or support strategic alliances in their transformative ambition.

4.3. Combining Collective Problematisation and Strategic Action to Develop Scenarios for Intervention

A social innovation approach goes beyond the planning professional ideal of collectively building a shared ontology and fully integrates institutional selectivity and strategic collaboration as key elements for understanding the possibilities for action. The gradual collective understanding of assets and needs by evolving strategic coalitions may unravel the mechanisms of inequality that can be at work in a specific institutional field. Critical moments and cracks in planning processes are traced that may reveal opportunities for strategic coalitions to navigate the complex reality of socio-spatial transformation.

To fully acknowledge this socially constructed understanding of action and plan-making, a socially innovative understanding of planning firstly includes processes of collective problematisation aiming for inclusion, stimulating solidarity, assessing assets and needs, etc. Secondly, it initiates strategic action, which aims building power, appropriating resources, changing legislative frameworks, etc. by professional practice. In particular, it is the combination of both lines of action by a more inclusive partnership of agents that successfully multiplies its strategic possibilities.

4.4. Building a Reflexive Positionality Through Tracing Its Ethical, Organisational and Socio-Political Consequences

Planners are usually part of different collectives (a local coalition, a planning administration, an activist group, a private planning office or an educational or research context). Each of these structures has distinct decision-making mechanisms, specific (collective) capabilities, organisational identities and a specific institutional position. This makes it difficult to combine these different roles without raising strong ethical dilemmas and operationalizing key values like solidarity, mutual respect, democratic communication, collective self-evaluation and co-production (Moulaert & MacCallum, Citation2019; Moulaert & Mehmood, Citation2020).

The fourth reflective response focuses on these possible ethical dilemmas and activates all stakeholders in a planning process to think about their own organisational structure and how they organise themselves in a real-life or studio context. A range of questions is addressed on both an individual and group level: What are the different value positions and capabilities activated in the studio context? How can we organise ourselves to mediate between the expectations of local actors and studio tutors? How can I create the right conditions to ensure that the outcome of a collective learning trajectory is respected? What are the resources and capabilities that are available in the studio context to support local coalitions? Reflexivity is essential in building up such positionality. This involves learning from a detailed analysis of urban transformation dynamics while taking one’s own presence and involvement into account.

5. Six Years of Studio Making in the Dam Neighbourhood in Antwerp

In the following section we analyse how the four reflective responses described above were part of the different planning studios in the Dam neighbourhood in Antwerp and how they related to a specific understanding of socio-environmental justice as the subject of planning.

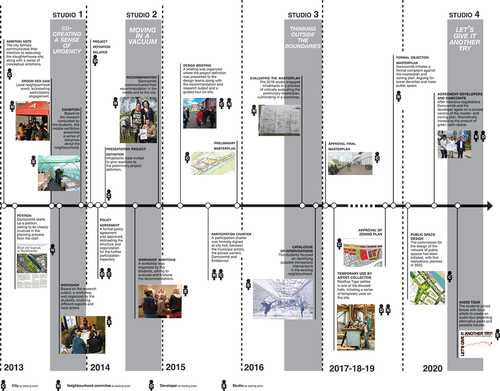

The four studios were all organised as part of a real-life and experimental participatory planning process (). Studio tutors were closely involved in this process, both through action research as part of doctoral research as well as pro bono work as members of a professional planning office. The trajectory aimed to strengthen resident involvement within a master planning process that will profoundly change the neighbourhood Dam – situated at the edge of Antwerp’s 19th century belt and one of the more socially deprived areas in the city. The neighbourhood is characterised by a rich history of industrial activities intertwined with a densely populated working-class residential area; it houses the site of the former municipal slaughterhouse, which almost literally cuts the neighbourhood in two. Over the past fifty years, the Dam has changed at a slow pace and has remained to a large extent outside the city’s urban renewal agenda (a.o. Christiaens et al., Citation2007; Loopmans, Citation2008; Van den Broeck et al., Citation2015). Several attempts have been made to initiate a redevelopment of the slaughterhouse site since the 2000s, but these brought no results until the newly appointed Alderman for spatial planning initiated an ambitious public-private redevelopment project to transform the slaughterhouse site into a residential neighbourhood.

For each of the studios the different dynamics of collective critical inquiry are traced (). We describe how they were organised around specific critical moments (introducing possible interpretations of socio-environmental justice), collective reflection and action (mobilising specific reflective responses). Resulting in a specific and partial reading of the planning and transformation process of the Dam neighbourhood. For each studio period the relation between the work of the students and the overall (participatory) planning process is summarised in to frame the period of transformation. The data we used to conduct this analysis was generated before, during and after the studios. We relied on: studio intermediate and final outputs; notes of meetings within the frame of the studio including discussions between teachers, teachers and students, and teachers, students and stakeholders; email exchanges between studio teachers, students and stakeholders; students’ individual and collective reflections that they were assigned to make; the studio brief and its various versions; minutes of mid and final reviews; data on the neighbourhood’s transformations collected for the studios; fieldwork notes; notes on numerous informal conversations; and discussions held during the drafting of previous versions of this paper.

Table 1. Overview of critical moments, collective reflection and reflective responses for four planning studios.

5.1. Studio 1 (Fall 2013): ‘Co-Creating a Sense of Urgency’

The momentum created by the announcement made in the media in 2013 by the new alderman prompted a recently established local neighbourhood committee (Damcomité) to take the lead in building a local coalition. Through personal contacts, Damcomité involved endeavour, a planning office that had been recently established by two of the authors, to help strengthen their claim for an innovative and early-on involvement in the planning procedure. This collaboration aimed to establish a sense of urgency in the neighbourhood over the fact that the foreseen procedure did not include a clear strategy on how the local community would be involved prior to the completion of the project definition. The collaboration between endeavour and the Damcomité was born out of a major concern: that studying the current day-to-day reality of the neighbourhood would not be prioritised and that local input could be sidelined in the project definition. Damcomité claimed that the city’s focus was predominantly on facilitating negotiations between private investors, and that actual participation would only be staged once the outlines of the future vision would be drawn. Through their involvement at KU Leuven as researchers, the authors had the opportunity to focus a studio trajectory in strategic spatial planning on this process, organised the first semester of each year as part of a Master’s programme in urbanism and strategic planning at KU Leuven.

The described context motivated the tutors to set the initial focus of the studio on mapping and understanding the socio-spatial reality of the neighbourhood. A direct and early-on engagement between Damcomité and the students on a local event (critical moment), allowed students to collect direct input from a variety of local residents. Analysing the input collected at the event, demonstrated to the students a general ‘lack of awareness of the community towards the ongoing process’ (final studio document, p. 43). In addition, Damcomité had voiced in several interactions its ambitions to connect local actors and strengthen the local network. After a collective discussion in the studio, aimed at delineating different future research tracks, the students came to the consensus that tracing the community dynamics and actor-networks (reflective response) would be essential groundwork to assist local parties in building a strong coalition. This motivated the students to direct the focus towards an elaborate social-network analysis, to identify local desires and needs, and opportunities to connect actors and assets. Additionally the studio investigated the long history of plan-making in the Dam, laying bare a strong tradition of local involvement, as well as a frustration regarding unexecuted plans and ideas – in this way giving flesh to a dialectic between planning, local activism and a sentiment of neglect (reflective response). A historical narrative helped the students to grasp the local ‘anxiety’ about not being included in the planning process from the outset and the absence of a framework to involve the inhabitants.

The inputs from the partners in the social network analysis allowed the students to map and detect blind spots in the network of local involvement (critical moment), and therefore proved instrumental in building a strategic alliance of the Studio with the Damcomité and supporting the latter in becoming local ambassadors (reflective response). At the same time, the students started questioning and exploring how they could use their skills as spatial professionals to collect data and develop readings of the neighbourhood, in order to feed participatory interactions (reflective response). They therefore focused on a combination of socio-spatial mappings, for example studying flows and movements, and visual analysis of the spatial patterns of the neighbourhood. The students emphasised their search to adapt a mode of research and visualisations which would ‘go beyond a spatial language’ (final studio document, p. 43) and develop a capacity amongst local inhabitants to discuss and critique spatial concepts.

Gradually, through the analysis, laying bare socio-spatial dynamics and particular challenges in the neighbourhood, the students together with the tutors began to problematise the apparent lack of in-depth socio-spatial readings of the neighbourhood as part of the project definition (critical moment). The mid-review of the Studio, an intermediate presentation usually structured as a presentation, proved to be a key moment in taking the collective problematisation a step further. In collaboration with Damcomité, the students decided to organise it as a workshop in order to test the usability of the different research outputs (reflective response) by bringing them together in the form of what the students termed a ‘toolbox’ (final studio document, p. 43). In response to the workshop and follow-up discussions with the tutors and some external critics (critical moment), the students pursued two tracks which would become intertwined (reflective response). Firstly, they developed a series of narratives about the neighbourhood, integrating social, spatial and intervention-related analysis. This track was clearly stimulated by Damcomité who became aware of the potential of visualisations and mappings. Secondly, they built on the recurring thematic of staging a spatial intervention ‘to spatialise the forum and leave behind a tangible result of our engagement with the neighbourhood’ (individual reflection). This was triggered by a shared awareness developed by the students and Damcomité to proactively start to re-appropriate run-down, forgotten spaces that would be part of the masterplan such as the slaughterhouse site itself and the quays of a nearby dock.

In the final output of the studio, the uncertain development process, and the recently established local coalition (critical moment), resulted in a surprisingly strong focus on reflection and process-evaluation (reflective response). The strong local involvement triggered continuous discussion amongst the students: to what extent was the process truly and sufficiently inclusive, going beyond the usual suspects and involving forgotten voices in the neighbourhood? The students emphasised the difficulty of coming to a shared understanding of the positioning and goal of the studio, epitomised by the effort to collectively write a mission statement. Lastly, students struggled with what they termed an ‘action-bias’, or the urge to realise something concrete, an agenda which seemed to become all too dominant towards the end of the studio.

5.2. Studio 2 (Fall 2014): ‘Moving in a Vacuum’

Studio 2 took place in a considerably different context. One of the private owners planned on selling part of the site to a real estate development group. The situation of temporary standstill triggered negotiations between the neighbourhood actors and the city to draft an agreement on the procedures of the formal participation process to be implemented during the master planning phase. At the same time, a public presentation by the city administration on the ambitions in the project definition made apparent that they had remained fairly generic: despite the effort invested in elaborate research and deliberative moments, the ambitions had not been amended nor ‘locally enriched’ and remained no more than ready-made blueprints.

Shortly after the mid-review, as the students were contemplating on the next moves, the tutors were informed of the interest of the local administration to initiate a (temporary) revaluation of a local neighbourhood park (critical moment). This prompted the students to reflect on the strong sentiment picked up during the mid-review: that existing spaces were becoming neglected and, despite their local importance, were under pressure of being built up according to a supra-local real estate development logic. This inspired the students to elaborate a design proposal for a natural playground to build a new coalition of local social organisations, inhabitants, as well as municipal stakeholders and political representatives around the project (reflective response).

Working on this project students acknowledged a tension between working ‘for’ Damcomité whilst producing an output or leave a mark ‘as a studio’ (critical moment). The dependency on real-life situations and different actors slowed down a process that students wanted to speed up in order to come to a physical realisation during the course of the studio. They slowly shifted focus from realising the intervention to empowering others to take up responsibilities for its realisation (reflective response).

The students’ work on a proposal for a natural playground was shared and communicated in the form of a pamphlet and temporary installation at a Christmas party in the local community centre (critical moment). Interestingly, it was here, at the festive end of the studio trajectory, that students started to critically reflect on the growing disconnect between local dynamics and the official participatory trajectory that was being prepared. Informal discussions on the neglect or undervaluation of certain spaces and the social importance of community spaces in the existing neighbourhood resulted in a problematisation of how the redevelopment of the slaughterhouse site lacked a position towards local transitions, dynamics and aspirations, beyond the project’s boundaries (reflective response).

5.3. Studio 3 (Fall 2016): ‘Thinking Outside the Boundaries’

During the course of 2015 and the first half of 2016, a design team was appointed to work on a preliminary masterplan for the Slaughterhouse site. Moreover, a community briefing was staged; the recommendations as well as the research outputs of previous studios were shared with the team; and several community workshops were organised to provide input to draft designs. By the start of studio 3, a preliminary masterplan had been drafted, awaiting formal approval, and the planning procedure to draft a land-use plan had been initiated. Damcomité therefore redirected its attention to critically evaluate the proposals in the masterplan, putting forward recommendations considering the phasing of the redevelopment, and finally making a plea for a stronger focus on affordable and alternative housing models. Whereas both previous studios focused heavily on participatory engagement in preparation of the masterplan, in this studio students were confronted with a ready-made masterplan. This considerably impacted the sequence of different reflective responses.

As a result of having to position the studio in relation to an existing masterplan (critical moment), this studio predominantly started by evaluating the preliminary masterplan, rather than directly engaging with local stakeholders. The first half of the studio was driven by a collective problematisation of certain aspects of the masterplan: as a means to process the large quantity of pre-existing material as well as study and evaluate the potential impact of the masterplan on the local and supra-local level. Therefore, the students directed their analysis at problematising how in the masterplan certain public spaces seemed vaguely defined and undervalued despite their local importance, and the surprising lack of a concrete development strategy and program for the slaughterhouse halls – a centrepiece in the project site (reflective response).

In contrast to the previous studios, students indicated struggling early-on with setting out a course of action and delineating the potential output of the studio. They had difficulty positioning themselves and collectively defining the ‘purpose’ of the studio in relation to the vast amount of work already done by previous studios as well as connecting to an officialised participatory trajectory that was already ongoing (critical moment). After the mid-review, students were asked to individually write a reflection on a further course of action which in turn triggered a productive collective reflection on two levels: whether or not it would be strategic to actually design alternative scenarios, a course of action Damcomité was pleading for; and set up a parallel participatory trajectory, confronted with the reality that the students would only be involved for a limited time. Instead, the students decided for a fundamentally different positioning, focusing on what was absent in the current masterplan: strategies on both a micro-scale (small social spaces in the existing neighbourhood), and a meso-scale (how the slaughterhouse halls could play a role as a new socio-economic engine for the wider area) (reflective response).

Following this new course of action, the students redirected attention to issues that had remained outside of the scope of the masterplan and previous engagements with the neighbourhood (critical moment). This allowed for a setting where students could engage once more in exploratory research yet setting them apart from previous analytical work. Rather than directing attention towards local actors, this allowed them to engage with external experts as well as construct a database of references of socio-cultural projects that have a lever effect on deprived neighbourhoods. This exploratory research allowed to identify certain blind spots in the existing visions and initiatives, as well as retrace important identity markers and important socio-economic dynamics, in particular in relation to the slaughterhouse halls (reflective response).

The responses described above implied that the final-review, in contrast to previous studios, was constructed as a presentation of the research results to Damcomité (critical moment). Firstly, the results were presented in the form of a catalogue of interventions in the existing neighbourhood tissue: different prototypes of micro-projects that demonstrated how the existing neighbourhood should be connected physically as well socially to the transitions that would take place. Secondly, the students had drafted a manifesto, website and film for an alternative development model of the slaughterhouse halls, emphasising its potential as a renewed motor for the neighbourhood. This setting and the resulting discussions were aimed at raising awareness amongst Damcomité and other actors of the potential and feasibility of tactical interventions in the neighbourhood and alternative development models (reflective response).

5.4. Studio 4 (Spring 2020): ‘Let’s Give it Another Try’

After several years of not being involved in the Dam neighbourhood, the fourth studio took the exceptional shape of 3 students conducting their Master’s thesis research on the Dam. Starting points were meetings between one of the studio teachers and a representative of a group of artists that had moved into the former slaughterhouse warehouses and who had invited the teacher and students to collaborate on the future of the slaughterhouse site (critical moment). The masterplan and concomitant land use plan and the Damcomité that sued the developer for not complying with the masterplan and land use plan provided a clear context of decisions. In the meantime, the artists had developed artistic community activities together with the neighbourhood and were silently hoping to still affect the future use and form of the warehouses.

The discussion on the position of this fourth studio imposed itself from the beginning. Given the previous studios, it was clear that the development project was going to happen, which triggered the question of possible instrumentalisation of the artists by the developer, who had allowed the artists in through short-term contracts to activate the site and was happy with the positive attention the place was receiving. Contacts by the studio teachers with the responsible city official confirmed that the studio should not question the development project, but that thinking about the design of green spaces would be desirable. This affected the discussion in the studio on the studio brief, the studio’s conditions, and the question of instrumentalisation of artists for urban development (reflective response).

Not long after the start of the studio, the abrupt COVID-19 lockdown made physical contact with the case study and its stakeholders very difficult. One student, having studied the model explained above, which had evolved more and more after discussions among studio teachers (critical moment), started building an actor-institutional chronology of the neighbourhood. The other students supported this by conducting a literature search, especially on the history of the slaughterhouse (reflective response). Students created an elaborate scheme, showing five historical tracks along which power dynamics unrolled (neighbourhood welfare, art and lively community, food economy and culture, functional diversity, urban development practices in Antwerp) and six emblematic moments defining how the place came to be what it is today. The final outcome of this work was a first definition of a problem statement for the site and the studio based on a selection of key-issues and key-actors, which was also presented during the studio’s mid review.

By the time of the mid review, the students had only been in touch with some of the stakeholders through a few interviews. Students had only spoken once with the artists. So the studio put little effort into thinking about potential alliances for producing specific studio outputs or proposals. However, the interview with the previous owner-developer provided a lot of insight into the power struggles around the development of the site (critical moment). During the mid-review students decided it was time to take more strategic and concrete action; they chose to support the artists in expanding their network in the neighbourhood and to not make any move towards the current developer (reflective response).

In brainstorming sessions, artists, representatives from the neighbourhood, students, and teachers decided to develop an audio tour on the history, possible alternative pasts and possible futures of the site, supporting a virtual exposition (reflective response). The audio tour, entitled ‘Let’s give it another try’, was fed by the extensive analyses conducted in this and previous studios, turning it into an action. It indirectly questioned the decisions taken for the development of the housing project, which neglected the rich past of the site and missed opportunities for re-building an economically, socially and culturally lively neighbourhood (critical moment). The students’ elaboration of the audio tour triggered interest from the artists, local residents and the heritage agency of the city of Antwerp, offering to develop it further.

Discussions during the final review brought the studio back to the original questions on the studio’s position in a context of almost certain development and potential instrumentalisation of artists, who had been granted access to the site without the guarantee of long-term engagement. Students were challenged by external reviewers (critical moment) for having been too neutral, but this was contradicted by the students, the artist present and a local resident, praising the students for taking a position by asking subtle but critical questions about the alternative futures for the site (reflective response).

6. Conclusion

This paper has explained, operationalised, and tested a theory, methodology and frame for a relational approach to spatial development analysis and planning, building on the authors’ previous work on social innovation, collective learning and strategic-relational planning. Following Lake (Citation2016), this approach sees socio-environmental justice as a subject rather than an object of planning, making planning a ‘situated moral inquiry’ and a collective reflection rather than a ‘final moral judgement’.

Developing a relational approach based on mutual respect and a situated understanding of socio-environmental justice is a co-productive endeavour. The frame presented in this paper was the result of the existing tradition of socially innovative action and research of the studio teachers and was co-constructed during collaborations among teachers, students and stakeholders along 6 years of planning studios on the case study area of the Dam neighbourhood in Antwerp (Belgium). Developing the frame enabled the authors to clarify their thinking, challenge students and introduce a relational understanding of planning practice. The transdisciplinary methodology implies that in principle each studio should and can develop its proper frame. Following a process of collective critical inquiry, analysing the field of action and the positions of all participants, and tracing critical moments and reflective responses, at which planning actors collectively reflect and take position regarding socio-environmental justice as the subject of planning.

Looking back at the four studios shows how different moments of collective critical inquiry became instrumental to raise, discuss and respond to questions of socio-environmental justice in the development of the Dam. shows how this process of collective critical inquiry is dynamic and negotiated. During the six-year process, a variety of critical moments emerged. Sometimes these moments were actively initiated in the studio process, while other times evolutions in the development project or activities of the Damcomité stimulated reflection and re-positioning. In each studio students chose to structure their work in another sequence, starting from a different type of reflective response and in always unique combinations, responding to an ever-changing order of events characterizing the dynamic and often messy nature of planning processes.

This highly situated order of reflective responses highlights the blur boundaries between the studio as a pedagogical experiment, a situated response to development oriented planning process or an attempt to co-construct a real-life and experimental participatory planning process. The analysis of the four studio periods present elements of each of these three dynamics without clearly identifying how they are each structured over time. The variety of critical moments and reflective responses hints at the entanglement of these various tracks but also situates them in a collective but subjective and partial reading of planning dynamics and transformations, having socio-environmental justice at the heart. This mode of situated moral inquiry invites to understand the planning studio as a socio-pedagogical project, dialectically interacting with, and becoming part of, the reality of a planning process.

If we would start from our proposed frame for critical inquiry to understand and define planning practice, a set of consequences needs to be taken into account. The logic of alternating critical moments with reflexive responses introduces a radically situated interpretation of planning practice. The act of planning and its related instruments is not solely defined by a clear purpose-driven procedure but flexibly tries to respond to changing conditions and mechanisms of social-environmental justice. In the process of the studio only a court case by the local activists against the environmental permit of the project could convince the city and developer to adapt their plans and fundamentally take position. This shows the rigidity of current planning procedures to include new claims and urgencies that are revealed in parallel to official planning procedures. In line with the studio’s backbone of a continuous conversation, planning could be less framed as an official procedure and process of consultation but instead highlight the multiple and parallel negotiations that form such a process. This could help question the framing (or boundaries or involved stakeholders) of a planning project on the fly and create more room for manoeuvre to actually search for possible win-win solutions and engage with socio-environmental justice in a profound but situated way.

Consequently, it becomes important to challenge dominant understandings of collaboration and representation in planning practice. A relational planning approach introduces a disruptive understanding of democratic politics. Democratic politics is not only understood as the inclusive deliberation between all stakeholders (deliberative democracy) but also the (temporary) dis-identification of people with their assigned name, place and function in the existing societal order (Kaika & Karaliotas, Citation2014). In the studio we can find traces of this approach in the strategic alliances that were fostered. All of them resulted from an attempt to reinforce a group of local actors to be acknowledged in a different role and as such challenge the planning process. Decisions on whom to collaborate with are no longer based on what is commonly agreed upon (often referring to the need of representative and inclusive collaborations) but on individual and collective assessment of mechanisms of socio-environmental justice and social order in a specific place and moment in time.

In order to deal with this need of situated moral inquiry, there was a lot of emphasis in the studio on the positionality of the group, its capacity to reflect collectively and the design of its own organisational structure. Tracing the capacities of the group to respond to ever-changing conditions and engage with a variety of planning instruments and interventions allowed for developing a culture of discussion and negotiation that supports the engagement with critical moments and reflexive responses as outlined in this paper. Introducing such a culture of collective reflexive discussion is a challenge in planning practice. As was shown in the analysis, this requires both the flexibility to navigate in and around a constantly changing case study and giving enough attention to the internal process of building a context for developing a learning community and stimulating collective reflection and relational thinking. This situated nature of relational planning as a critical socio-pedagogical endeavour forms both a challenging configuration for studio teaching and planning practice, requiring the ‘right’ learning environment, the conditions of which we have explored in this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Christiaens, E., Moulaert, F., & Bosmans, B. (2007) The end of social innovation in urban development strategies? The case of Antwerp and the neighbourhood development association ‘Bom’, European Urban and Regional Studies, 14(3), pp. 238–251. doi:10.1177/0969776407077741

- De Blust, S., Devisch, O., & Vandenabeel, J. (2021) Learning to reflect collectively: How to create the right environment for discussing participatory planning practice?, European Planning Studies, 30(6), pp. 1162–1181. doi:10.1080/09654313.2021.2014403

- De Blust, S., & Van den Broeck, P. (2019) From social innovation to spatial development analysis and planning, in: P. Van den Broeck, A. mehmood, A. Paidakaki & C. Para (Eds) Social Innovation as Political Transformation. Thoughts for a Better World, pp. 100–105 (Cheltenham: Edward Algar Publishers).

- Friedmann, J. (1992) Empowerment: The Politics of Alternative Development (Cambridge, MA: Blackwell).

- Healey, P. (2009) The pragmatic tradition in planning thought, Journal of Planning Education and Research, 28, pp. 277–292. doi:10.1177/0739456X08325175

- Healey, P. (2013) Comment on Albrechts and Balducci. “Practicing strategic planning, disP, 49, pp. 48–50.

- Jessop, B. (2001) Institutional (re)turns and the strategic-relational approach, Environment & Planning A, 33, pp. 1213–1235. doi:10.1068/a32183

- Jessop, B. (2008) State Power: A Strategic-Relational Approach (Cambridge: Polity Press).

- Jessop, B., Moulaert, F., Hulgård, L., & Hamdouck, A. (2013) Social innovation research: A new stage in innovation analysis?, in: F. Moulaert, D. MacCallum, A. Mehmood & A. Hamdouch (Eds) The International Handbook on Social Innovation. Collective Action, Social Learning and Transdisciplinary Research, pp. 110–130 (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar).

- Kaika, M., & Karaliotas, L. (2014) The spatialisation of democratic politics: Insights from Indignant Squares, European Urban and Regional Studies, 23(4), pp. 1–15.

- A. Khan, Van den Broeck, P., Segers, R., Van Dyck, B., Pluym, B. (2016) Part I. Spatial quality. Why, for whom and according to which method?, in: R. Segers, P. Van den Broeck, A. Khan, J. Schreurs, B. De Meulder & F. Moulaert (Eds) The SPINDUS Handbook for Spatial Quality. A Relational Approach, pp. 18–32 (Rotterdam, Brussel: ASP).

- Lake, R. W. (2016) Justice as subject and object of planning, International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 40(6), pp. 1206–1221. doi:10.1111/1468-2427.12442

- Loopmans, M. (2008) Relevance, gentrification and the development of a new hegemony on urban policies in Antwerp, Belgium, Urban Studies, 45(12), pp. 2499–2519. doi:10.1177/0042098008097107

- MacCallum, D., Moulaert, F., Hillier, J., & Haddock, S. V., (Eds). (2009) Social Innovation and Territorial Development (Farnham: Ashgate Publishing Ltd).

- Marcuse, P., Connoly, J., Novy, J., Olivo, I., Potter, C., & Steil, J., (Eds). (2009) Searching for the Just City (New York: Routledge).

- Miciukiewicz, K., Moulaert, F., Novy, A., Muserd, S., & Hillier, J. (2012) Problematizing urban social cohesion: A transdisciplinary Endeavour, Urban Studies, 49(9)pp. 1855–1872. doi:10.1177/0042098012444877

- Moulaert, F., & MacCallum, D. (2019) Advanced Introduction to Social Innovation (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishers).

- Moulaert, F., Martinelli, F., Gonzalez, S., & Swyngedouw, E. (2007) Introduction: Social innovation and governance in European cities. Urban development between path dependency and radical innovation, European Urban and Regional Studies, 14, pp. 195–209. doi:10.1177/0969776407077737

- Moulaert, F., Martinelli, F., Swyngedouw, E., & Gonzalez, S., (Eds). (2010) Can Neighbourhoods Save the City? Community Development and Social Innovation (London: Routledge).

- Moulaert, F., & Mehmood, A. (2010) Analysing regional development and policy: A structural-realist approach, Regional Studies, 44(1)pp. 103–118. doi:10.1080/00343400802251478

- Moulaert, F., & Mehmood, A. (2014) Towards social holism: Social innovation, holistic research methodology and pragmatic collective action in spatial planning, in: E. A. Silva, P. Healey, N. Harris & P. Van den Broeck (Eds) The Routledge Handbook of Planning Research Methods, pp. 97–106 (London: Routledge).

- Moulaert, F., & Mehmood, A. (2020) Towards a Social Innovation (SI) based epistemology in local development analysis: Lessons from twenty years of EU research, European Planning Studies, 28(3), pp. 434–453. doi:10.1080/09654313.2019.1639401

- Moulaert, F., Mehmood, A., MacCallum, D., & Leubolt, B. (2017) Social Innovation as a Trigger for Transformations - the Role of Research (Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union).

- Novy, A. (2012) Unequal diversity” as a knowledge alliance: An encounter of Paulo Freire’s dialogical approach and transdisciplinarity, Multicultural Education & Technology Journal, 6(3), pp. 137–148. doi:10.1108/17504971211253985

- Parra, C. (2013) Social sustainability: A competing concept to social innovation?, in: F. Moulaert, D. MacCallum, A. Mehmood & A. Hamdouch (Eds) The International Handbook on Social Innovation. Collective Action, Social Learning and Transdisciplinary Research, pp. 142–155 (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar).

- Sandercock, L. (2003) Cosmopolis II: Mongrel Cities in the 21st Century (London: Continuum).

- Servillo, L. A. (2017) Strategic planning and institutional change: A karst river phenomenon, in: L. Albrechts, A. Balducci & J. Hillier (Eds) Situated Practices of Strategic Planning: An International Perspective, pp. 331–348 (London: Routledge).

- Swyngedouw, E. (2008) The multiple and the one, in: J. Van den Broeck, F. Moulaert & S. Oosterlynck (Eds) Empowering the Planning Fields, pp. 135–141 (Acco: Leuven).

- Swyngedouw, E., & Heynen, N. (2003) Urban policial ecology, justice and the politics of scale, Antipode, 35(5), pp. 898–918. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8330.2003.00364.x

- Van den Broeck, P. (2008) The changing position of strategic spatial planning in Flanders. A socio-political and instrument based perspective, International Planning Studies, 13(3), pp. 261–283. doi:10.1080/13563470802521457

- Van den Broeck, P. (2011) Analysing social innovation through planning instruments. A strategic-relational approach, in: S. Oosterlynck, J. Van den Broeck, L. Albrechts, F. Moulaert & A. Verhetsel (Eds) Strategic Projects. Catalysts for Change, pp. 52–78 (London and New York: Routledge).

- Van den Broeck, P., Leubolt, B., Delladetsimas, P., Hubeau, B., & Parra, C., F. Moulaert, (Eds). (in press) Governing Shared Land Use Rights: Conceptualising the Landed Commons (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing).

- Van den Broeck, J., Vermeulen, P., Oosterlynck, S., & Albeda, Y. (2015) Antwerpen Herwonnen Stad? Maatschappij, Ruimtelijke Plannen En Beleid - 1940-2012 (Brugge: Die keure).

- Van Dyck, B., Moulaert, F., & Kuhk, A. (2019) Transdisciplinaire praktijken: Participatieve onderzoekstrajecten als collectieve leerprocessen, in: A. Kuhk, H. Heynen, L. Huybrechts, J. Schreurs & F. Moulaert (Eds) Participatiegolven: Dialogen Over Ruimte, Planning en Ontwerp in Vlaanderen en Brussel, pp. 147–165 (Leuven: Universitaire Pers Leuven).

- Velicu, I., & Kaika, M. (2015) Undoing environmental justice: Re-imagining equality in the Rosia Montana anti-mining movement, Geoforum, 84, pp. 305–315. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2015.10.012