ABSTRACT

Human rights are inalienable rights we each possess by virtue of being human. In Canada, Ontario has been at the forefront of progressive human rights policies. Despite this, human rights complaints related to land use regulations have been on the rise. This study pursues three questions: Why are human rights challenges against land-use regulations increasing? What human rights challenges do Ontario municipalities face? and how do they respond? We conclude that despite significant advancements on the human rights front, Ontario municipalities struggle to understand fully their legal and moral obligations and have yet to catch up with new judicial interpretations.

1. Introduction

After the adoption of the UN’s Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) in 1948, the Province of Ontario actively pursued the advancement of human rights in Canada, such as implementing a revolutionary set of rights in 1962 (Ontario Human Rights Commission, Citation2013). Since then, and particularly with the repatriation of the constitution and adoption of the Charter of Rights and FreedomsFootnote1 [hereafter referred to as the Charter] in 1982 as a part of the Constitution,Footnote2 further legislative advancement has been made.

Despite this ongoing legislative progress, human rights complaints at the municipal level have been on the rise (Agrawal, Citation2014, Citation2021). An uptick in challenges related to municipal land-use, on human rights grounds, is among them (Agrawal, Citation2021). Human rights challenges confronting planning policies are not limited to Canada. In the US, Europe, and elsewhere, land-use planning issues have been contested on human rights grounds such as squatters’ rights, property rights, and the right to housing (Agrawal, Citation2022). Unfortunately, the scholarly literature does not tell us much about the types of land-use issues and consequently human rights challenges that arise and what steps, if any, municipalities have taken or can take to combat them.

This study intends to explore three questions:

Why are human rights challenges against land-use regulations increasing in Ontario?

What human rights challenges arising from land-use do Ontario municipalities face and how do they respond?

Have Ontario municipalities made any progress on the human rights front?

In answering these questions, we assessed the situation from 2010 to 2020, while also referring to any prior leading court decisions or the past issues that persisted during this period.

The remainder of the paper is divided into five parts. The next part sets the stage, with a background on the concept of human rights, the constitutional and quasi-constitutional aspects of human rights, and the evolution of human rights in Ontario. The third part elaborates on the methods, which included multiple sources of data as well as analyses. The fourth part details the findings that provide evidence of land-use issues that have led to human rights challenges, along with ongoing concerns. This is followed by a discussion that contextualizes and explains the findings using case law on human rights. The final and concluding part argues that much of the rise in human rights complaints reflects increased awareness of rights by the public. Ontario municipalities have made significant progress by amending their bylaws and decision-making processes; nonetheless, new and perennially unresolved, land-use issues remain challenging, necessitating plenty of catching up.

2. Background

2.1. Human rights

The literature on human rights is extensive (see Donnelly, Citation2013; Sandel, Citation1998; Sen, Citation2004, Citation2006; and others). We define human rights as inalienable rights we each possess by virtue of being human, based on our inherent dignity and equal worth as human beings. They are moral rights of the highest order, although the concept of human rights is primarily Western, mostly secular, and better achieved in liberal democracies. Further, rights are institutionally defined rules specifying how people can act with one another, upheld by enduring legal protections granted to individual citizens by the liberal-democratic state. They encapsulate two moral and political claims: rectitude, which is righteousness or doing the right thing, and entitlement, which is both having a right and a right that is owed to someone either by an individual or the state (Donnelly, Citation2013).

The UDHR is the foundation of modern human rights law, inspiring extensive and legally binding laws. While almost all nation-states have ratified the UDHR, the domestic instruments of implementation vary considerably from one country to another, since the implementation of human rights is largely political. In Canada, both the constitution and federal, provincial, and territorial human rights statutes provide rights to individual Canadians, supported by a legal framework to protect their rights.

2.2. The charter, human rights legislation, and Canadian cities

Canadian human rights are articulated in two forms: quasi-constitutional and constitutional. Federal, provincial, and territorial human rights statutes work to ensure constitutional calls, and, importantly, override other laws if and when they conflict. However, they are legally adjacent to the Charter itself (hence, the ‘quasi’), which is embedded in the Constitution Act of 1982, establishing the heart of the Canadian constitutional guarantee. Prior to 1982, few rights and freedoms were guaranteed, for example, language- and denominational-school rights, women’s voting rights, and freedom of the press.

Interesting, it was the duties thought to be owed by governments to their people that implied constitutional rights, rather than some intrinsic aspect of being human – a notion that is pervasive today. In Canada, the British North American Act of 1867, the predecessor of the Constitution Act. Before the Charter was enacted, individuals’ civil liberties were constrained by the principle of legislative supremacy. Prior to the Charter, the true Canadian pursuit of human rights and liberties first occurred at the provincial level as individual provinces sought to grant them to their citizens. Saskatchewan was the frontrunner, passing its provincial Bill of Rights in 1947, a noteworthy date as it situates this before the otherwise foundational UDHR. In 1962, a more widespread rights initiative launched in Canada: Ontario’s Human Rights Code came in to being [hereafter referred to as Code], followed in 1974 by British Columbia’s Human Rights Code (Clement, Citation2016).

At the federal level, the Human Rights Act became law in 1977, followed five years later by the Charter, driven by the interest and endeavours of Pierre Trudeau, a former prime minister of Canada. The Charter has played an important role in raising awareness of human rights in the Canadian cultural landscape, even though scholars disagree on many of its elements. What matters most, however, is that it gives the judiciary a mandate to liberally interpret rights within a legal framework. As a result, since 1982 many new analogous grounds of discrimination have been added to the CharterFootnote3 (Morton, Citation1987; Smithey, Citation2001; Greene, Citation2014).

As Agrawal (Citation2021) expounds, the Charter is critical in defining the rights and freedoms of all Canadians, but only as they pertain to actions of the government. Thus, the human rights statutes at all levels of government address only how goods, services, facilities, employment, or accommodation are provided as private and public acts. This means that when individuals and private organizations interact, such as landlords or employers, it is federal, provincial or territorial human rights legislation and not the Charter that governs these encounters. This gets complicated is at the intersections of these domains, however: for example, a government action within an employment context, or any level of government offering services, facilities, or accommodations.

Among 33 sections of the Charter, four sections are key to understanding the nexus of land use and human rights including how they apply to municipal bylaws:

Section 1: This puts “reasonable limits [on rights] prescribed by law as can be demonstrably justified in a free and democratic society.”

Section 2: This supports Canadians in freely choosing and following whatever religion they prefer, while guaranteeing their freedom of thought, belief, and expression.

Section 7: Because this section establishes Canadians’ rights to life, liberty, and personal security, any laws that conflict with this intent may be invalidated, potentially resulting in the payment of damages or other remedies.

Section 15: This asserts that we are all equal, and we can rightfully expect equal protection and benefit of the law without having to face discrimination, based on a variety of grounds, such as race, disability, and others.

We must remember, though, that as per Section 1, no constitutional guarantees are absolute, which means that a limit can be placed on any Charter right as long as the restriction is “reasonable” and “justified.”

2.3. History of human rights in Ontario

Ontario’s adoption of the Code in 1962 instigated a rights revolution in the country, but this did not happen in isolation or in one stroke. Forces for reform in play over the previous decade or so, including both national and international factors, culminated in the Code. Adoption in 1948 of the UDHR was undoubtedly significant, compounded by Canada’s postwar policy on immigration that coincided with Ontario’s rapid economic growth (Howe, Citation1991). Ontario’s rapidly changing demographics also markedly participated in pushing legislative reforms. Several individual laws passed in the 1950s provided further thrust to the rights movement. These laws, which prohibited discrimination based on race and religion in employment, in public spaces, or in rental accommodation, were consolidated in 1962 into the single legislation that became the Code. It also resulted in the creation of the Ontario Human Rights Commission (OHRC) to administer and enforce the Code.

Since then, new human rights grounds have been added, congruent with evolving societal values and influences informed by an intensifying rights movement within the province, along with the US civil rights and other rights movements. Further protections emerged in the 1980s based on disability, sex and gender, sexual orientation, family status, pregnancy, exclusion from adults-only housing, receipt of public assistance, and the recognition of systemic discrimination. Furthermore, Ontario strengthened the OHRC ’s powers to investigate, recommend, and review government programs.

A major reform to Ontario’s human rights system came about in 2008, with the creation of two new bodies:

The Human Rights Tribunal of Ontario—to adjudicate over individual human rights complaints in place of the OHRC

The Human Rights Legal Support Centre—to provide legal advice to people making complaints, arguably unique in Canada

The OHRC was, in turn, tasked with educating, empowering, and mobilizing Ontarians to root out discrimination. It can also submit applications to the tribunal focused on systemic issues in the public interest.

3. Methods

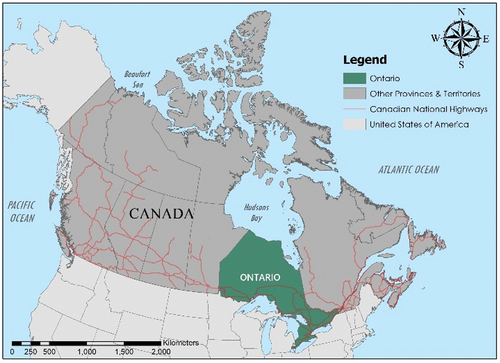

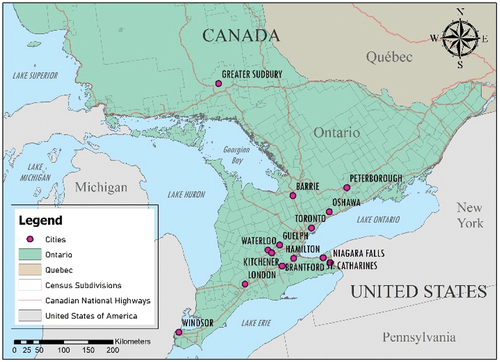

Ontario is the most populous and second-largest land area in the country (see ). It also has had more human rights challenges than any other province or territory in Canada. We selected 12 municipalities across Ontario, each from a different Census Metropolitan Area (CMA).Footnote4 The cities included in the study are as follows: St Catharines, Peterborough, Oshawa, London, Kitchener, Hamilton, Guelph, Brantford, Barrie, Toronto, Windsor, and Sudbury (see ). They are core municipalities of their respective CMAs but vary in population size (see for details). These places have had incidents of human rights violations grounded in land use as reported in the local media or documented in case law. We collected four data streams to stitch together a full picture of the intersection between human rights challenges and municipal planning: media coverage, case law, zoning bylaws, and key informant interviews. Of note, one strand of data informed the other, particularly, in building keyword search terms for bylaw and case law analyses.

Table 1. Details of the municipalities.

3.1. Media coverage

We searched local or national articles in the ProQuest news database and Google using keywords such as ‘human rights,’ ‘zoning’ along with the names of the 12 municipalities. The keyword search was expanded as more cases were reviewed, and we became familiar with the types of emerging land-use issues with human rights grounds. Our search ultimately elicited 17 newspaper articles, which we then reviewed closely. These articles, mostly from 2017 to 2021 (though some articles dated prior to 2017), helped us piece together a pattern about the emerging issues that may or may not have received a judicial review.

3.2. Case law

We collected and analyzed 27 pieces of case law from the Canadian Legal Information Institute (CANLII) database. The case law included judicial decisions rendered at both quasi-judicial levels (Human Rights Tribunal Ontario [HRTO], the now-defunct Ontario Municipal Board [OMB], and municipal level appeal bodies) and in the Ontario courts. Cases were selected based on their relevance to municipal bylaws, alleged human rights violations, or potential impact on strengthening the protection of human rights. Some cases went as far back as the 1980s and 1990s, but we focused on cases decided between 2010 and 2020, while relying on the leading decisions that affect the current situation.

The HRTO annual reports to the Government of Ontario present coarse statistics on a few aspects of applications and decisions, for instance, grounds of alleged discrimination such as gender, ethnicity or others and relevance of the application to a social area such employment, contracts and so on. What is missing in these reports is case classification based on a land-use or zoning concern. Therefore, we used CANLII to review every HRTO case heard between 2012 and 2021. Based on the interviews and the type of issues reported in the print media, we included the following keywords to search for relevant case law ‘bylaw’ (by-law(s), by law(s)), ‘zoning’, ‘land-use’, ‘housing’, and ‘transit’.

3.3. Municipal bylaws

We reviewed municipal bylaws and analyzed the zoning bylaws of the 12 municipalities. A keyword search was employed on all 12 sets of bylaws to identify land-use issues that can give rise to human right complaints, followed by a comprehensive review of each bylaw to identify any potential issues in definition of use or attached regulations, which may not have direct, obvious connections with human rights. Terms used in our initial search were ‘separation distance’, ‘church’, ‘place of worship’, ‘safe injection site’, ‘methadone clinic’, ‘group home’, ‘rooming house’, and ‘secondary suite’. We modified some of these terms in our subsequent searches as each municipality sometime uses different word for the same term. These were based on the common problem areas identified in the first author’s previous research works (Agrawal, Citation2017, Citation2021, Citation2022) and reported in print media or in case law.

3.4. Interviews

Finally, we interviewed 17 key informants, including human rights lawyers and municipal officials, such as directors of planning and city solicitors. These interviews were conducted between 2017 and 2019, just before the onset of the pandemicFootnote5. The open-ended interview questions revolved around the participants’ understanding of human rights and how it relates to planning, and their awareness of any past, ongoing, or potential human rights or Charter challenges to the municipal bylaws or council or administrative decisions made in their respective cities. We also sought to elicit their opinions about the frequency of human rights complaints and their knowledge of human rights challenges among municipal administrators and/or elected officials in their cities. During the interviews, we discussed a diverse human rights challenges ensued from the problematic land-uses identified by the interviewees such as location of housing, drug and addiction facilities, and places of worship. We coded the interview transcripts in the qualitative analysis software NVivo. We took meaning condensation approach to analyzing the interviews and grouping and abridging the interview transcripts into shorter formulations (Kvale, Citation2011; Malterud, Citation2012).

4. Findings

This section explains why human rights complaints have increased, land issues that have led to human rights challenges, and municipal actions to comply with the constitution and the human rights legislation.

4.1. Frequency of complaints

As mentioned before, the human rights complaints emerging from land-use and zoning issues are challenging to track. Neither HRTO nor municipalities keep record of or sort grounds of human rights complaints at a granular level. Our analysis shows that the land-use related cases at the HRTO varied between 2 and 13 out of over 1700 casesFootnote6 heard on an average each year between 2012 and 2021. This does not capture those cases that got resolved prior to an HRTO hearing or through an accommodation made by the concerned municipality before an application was filed with the HRTO.

We, therefore, relied on our interviewees’ responses to the question about the frequency and reasons for human rights complaints emanating from the municipality related to zoning. Six of 14 participants thought the incidence was unchanged in the last decade or so. Two discussed the changing trends in the types of complaints. One respondent identified an increase, based primarily on new and creative applications of human rights law. Seven respondents observed a definite increase in awareness, whether by the public or municipalities. Two expressed a view that municipalities’ improved abilities to understand potential human rights issues and deal with them early on might have tamed the number of complaints. These same two individuals added that cities are becoming more flexible and progressive with their planning instruments, while paying more attention to people’s concerns and rights. One respondent reflected the above sentiments by arguing the following:

I don’t think … [complaints are] coming up more frequently; [rather] it is driven by the types of applications. But I think over time, we have become better at managing and handling it … For example, in 2015, the [city] council very specifically reminded residents that they could not say prejudiced comments regarding people undergoing treatment for mental health. They needed to restrict their comments to questions of land-use planning, and … the municipality cannot and will not abide by prejudicial comments. And we can’t do ‘people zoning’ in Ontario as well. So, I think we have gotten better, over time.

Five respondents mentioned the heightened role of the OHRC in improving awareness of human rights among the public, as well as within municipalities in Ontario. When asked about the impact of the OHRC on municipal issues, the respondents were divided. One articulated that the OHRC’s public education campaign had a major effect, by highlighting municipal issues grounded in human rights. Another respondent agreed with this assessment and went one step further to fully embrace the OHRC’s role, stating the following:

I think in the Ontario context, we’re lucky that the Ontario Human Rights Commission has some really good publications on the relationship between human rights and land-use planning. And I know that at the department, we’ve all reviewed that information and we talk about it, and we’ve used it to educate our council members.

One other participant reflected on the positive impact of OHRC and how it played a key role in raising awareness and sensitivity to human rights challenges, and where they intersect with land-use planning:

We actually invited the OHRC to come here and do a presentation to the local municipality, the council and their planning staff, and administrative staff on the relationship between land-use planning and human rights. That was particularly helpful to the council of our day, how to better manage those planning processes … I think there are lessons that need to be reinforced and re-educated … .They should keep doing the outreach to communities.

In contrast, one respondent complained that the OHRC’s campaign unjustifiably labelled almost every municipal issue as a human rights problem, which diminished the focus on real, justifiably human rights issues.

4.2. Land-use issues

We uncovered several land-use issues where human rights violations were common and at times egregious. They occurred in relation to the following land-use issues: finding suitable locations for drug and addiction facilities; siting various types of housing, particularly affordable and supportive housing facilities such as group homes and students’ lodging houses; locating places of worship; restrictions in public spaces; and in engaging with Indigenous peoples on city development matters.

4.2.1. Cannabis, drug & addiction facilities

Locating medical cannabis, safe injection sites (SIS), and methadone clinics is a recurring issue in multiple municipalities. Zoning restricting the locations of such facilities – such as outright prohibitions, or additional restrictions like minimum separation distance – encountered human rights issues. For instance, Toronto’s zoning bylaw still does not allow cannabis facilities in commercial – residential or commercial – residential–employment zones, on the grounds that they negatively affect streetscapes.

Municipal approaches towards methadone clinics, and permanent and pop-up SIS, range from highly restrictive to no special regulations. As an example, Oshawa prohibited methadone clinics in areas with an overlay, effectively excluding them from locations in the city’s downtown areas. An interviewee from that city indicated the current overlay zoneFootnote7 was in response to the Loralgia ManagementFootnote8 case, which quashed Oshawa’s interim zoning bylaw prohibiting methadone clinics. In Loralgia Management, the Ontario Municipal Board (OMB; Ontario Land Tribunal as of 2021) ruled that, ‘in effect, what the City has done is ban a specific type of medical clinic not based on the function of the clinic but on those who will use the clinic and what their medical condition is. The Board finds that this is not a valid planning rationale.’ The ruling was subsequently upheld by Ontario’s Divisional Court.Footnote9 To circumvent the court’s ruling, according to the interviewee, the city developed the overlay zone with the aim to prevent saturation of such facilities on main downtown streets and pedestrian areas.

In Toronto, regular SIS, operating as a medical service, are allowed to operate in areas zoned for commercial use. As well, Toronto has allowed pop-up SIS, despite ongoing community NIMBYism; however, these sites contravene the City of Toronto Parks bylaw. In Hamilton, methadone clinics do not require a municipal business licence; in fact, the existing zoning bylaw has no category for these uses. Given that methadone treatments are a medical practice, similar to other doctor – patient encounters, this city concluded that attempts to regulate them through either licensing or zoning would be inappropriate.

The City of London, on the other hand, engaged with the OHRC to craft their zoning bylaw on SIS to ensure full compliance with the Code.

4.2.2. Religious institutions

Our review of 12 zoning bylaws revealed continued references to a place of worship as a ‘church.’ We were surprised by this language, presuming that zoning bylaws would have been scrubbed of this discriminatory language by now, which excludes mosque, synagogue, temple, or other types of religious institutions.

For example, the latest version of Peterborough’s zoning bylaw, approved in 2020, uses both ‘church’ and ‘place of assembly,’ whether interchangeably or separately. A place of assembly includes gathering places, used not just for religious purposes, but also for educational, recreational, cultural, social, or other purposes, while church refers to the use of premises for place of worship specific to one faith – Catholicism. A few cities like London removed references to ‘church’ from its zoning bylaw in 2014.

Between 2010 and 2020, Ontario municipalities have made concerted efforts to eliminate many restrictive sections of zoning that curtailed the siting of places of worship. These restrictions also required a minimum site area and a specified number of parking spaces, prohibited or limited their size or ancillary uses in many zones, or restricting their height, massing, or scale. This shift might have been precipitated by the Supreme Court of Canada’s (SCC) decision in the LaFontaineFootnote10 case in 2004, in which the court sided with the appellant, the Jehovah’s Witnesses. They had alleged that the municipality’s refusal to amend its zoning bylaw to allow them to construct their place of worship violated their freedom of religion under Section 2(a) of the Charter. The case sent a strong message to municipalities across the country to take appropriate steps to avoid violating citizens’ freedom of religion.

Our interviewee from Peterborough mentioned that his city understands the contentions around the current use of explicitly religious terms in the zoning bylaw. He suggested that the term ‘assembly’ should be used instead:

In theory you can, I think … delete a definition of a ‘place of worship’ and just treat it as ‘assembly.’ That would be a practical way of taking the air out of the balloon, [of] saying that, ‘We are not regulating you because of your religion.’

Some of the discriminatory language may be inadvertent remnants of the previous version of the bylaw. More importantly, it seems municipalities are becoming aware of the need to be more inclusive in their zoning language and avoid legal or moral restriction on the practice of religion.

The five relevant legal cases we carefully examined concern the variances sought to accommodate religious uses. In each case, the OMB, the highest planning appeals body at the time, granted the variances sought by the proponent. Two recent decisions, elaborated below, reflect issues related to small, but burgeoning communities of worship located in an industrial area or an apartment building, where they can find cheap space for their congregation (Agrawal, Citation2009).

In the Satnam Anami case,Footnote11 a religious organization operated a place of worship in two industrial condominiums in an area zoned industrial since 1998, under the authority of successive variances. When the applicant applied for the variance in question, it was denied by the City of Brampton, which is a part of the Toronto CMA. The city expressed concerns over lack of parking and too many religious groups onsite, also arguing that the temporary nature of the use was becoming ‘semi-permanent’ because of successive approvals of variances. The president of the complex corporation expressed similar concerns. Despite these issues, the board found that overall, the facts underlying the previous 2003 decision to grant the variance had not changed, and therefore granted the variance.

In 1140971 Ontario Ltd,Footnote12 decided in 2010, the owner of an apartment complex had proposed turning two redundant storage rooms into ‘meeting rooms,’ one for Muslim prayers five times daily. These renovations prompted the City of Toronto to issue a notice of violation for illegally inserting a ‘place of worship.’ The owner applied for a variance, stating that the change was for a meeting room, with daily prayer activities just part of its overall usage. When the application was refused, the owner appealed to the OMB. The board stated that the bylaw has two categories – religious institutions and places of worship – and found owner fit under the first category as the tenants would use the onsite space. In contrast, the second category would attract people from outside into the building. Finding that the proposal was a feasible ‘as-of right’ since the existing zoning allowed for religious institution uses, the board determined that no variance was necessary; the city had incorrectly interpreted a ‘place of worship.’ It is noteworthy that these cases were not decided on questions of human rights law, but on the technical aspects and specific (mis)interpretations of zoning bylaws and accepted planning principles and processes. Nonetheless, they have tremendous human rights implications.

4.2.3. Restrictions in public spaces

We found no overt restrictions in the zoning bylaws about what one can or cannot do in public spaces. Case law exists on other municipal bylaws alleged to have violated protesters’ freedom of expression in public space. Among the three cases reviewed, the recent Batty caseFootnote13 concerned whether the municipal stoppage order prohibiting protest by camping in a public park violated Section 2 of the Charter, which guarantees freedom of expression.

The applicant Bryan Batty, and other members of a protest movement, erected tents and other structures in a Toronto park, but without permits. The city delivered a trespass notice ordering protesters to stop erecting structures and camping in the park at night. The applicant challenged the validity of the notice, contending that it violated protesters’ rights under Section 2(a) through (d) of the Charter; however, the ruling stated that Charter rights were not contravened.

In his judgment, Justice Brown detailed that the Charter (including Section 2) offered no justification or protection for protesters appropriating significant, common public space for their own use, such as camping; further, they did not consult fellow citizens, who would be prevented from enjoying it themselves for an indefinite period. The issue is not whether the form of expression is compatible with the function of public space, but whether free expression, in the chosen form, undermines values the freedom-of-expression guarantee is designed to promote. Specifically, the notice may have infringed on applicants’ fundamental freedoms (Section 2 of the Charter), but this was justified under the Charter, Section 1.

4.2.4. Housing

Housing was the most scrutinized area vis-à-vis human rights infringements. Violations concerned zoning bylaw wording and whether it regulated the use or the user. This focus arises from the Bell case,Footnote14 which determined that municipalities could control the use of properties but not who used them. Supportive housing and students’ rental housing have been the most affected by this.

4.2.4.1. Use vs. user

Several issues related to uses and their definitions emerged; these largely focused on regulating users rather than addressing legitimate land-use concerns. For instance, Peterborough places requirements on who can occupy ‘special districts,’ with the zoning bylaw designating ‘dwelling units shall be occupied predominantly by persons fifty-five years of age and over and by persons with disabilities.’ Similarly, the City of London’s zoning bylaw has the use ‘garden suite,’ which is ‘intended to be occupied by the elderly relative(s) of the host family,’ thus specifying both the age and the relation of the user to the residents in the primary dwelling.

One interviewee provided an example of how users become central to the land-use and development discussion:

There is an application that we’ve received … where a developer has permission to build 800 dwelling units in an apartment format . … The developer constantly changes [his application] … sometimes it is a combination of regular rentals plus affordable, and then housing plus seniors housing. And at times he has described the application as being ‘crisis care’ residents, so it’s taking different forms, and in that particular context, the councillor is saying to the developer, ‘Be clear on what you want to ask for.’ … Because we are taking this to the community, and we don’t need to be raising … any sort of concerns. We don’t want to have that type of conversation. This is a land-use planning discussion, it’s not about who’s living there.

These remarks also show an elected official exhibiting an awareness of potential human rights concerns and imparting appropriate advice to avoid infringing on citizens’ rights.

4.2.4.2. Students’ rooming houses

Recently, students’ rooming or lodging houses have become a recurring issue in university towns and around campuses in cities like Hamilton, Oshawa, St. Catharines, Kingston, Waterloo, and Windsor – often related to issue of ‘family status.’ In particular, students and other renters live in a dwelling designated as ‘single-family’ as opposed to a lodging or rooming house, which is a building where multiple people rent single rooms and share a kitchen and/or washroom. The definition of family status in the Code is narrow, but the case law on how to determine family status is mixed, adding to the uncertainty (Ontario Human Rights Commission, Citation2005).

Rooming houses inhabited by students raise the recurring question of whether young people are prevented from sharing accommodation anywhere in a city, due to stereotypes about their age or because they do not resemble a legally defined traditional family. Ultimately, these cases must balance legitimate health and safety issues with the risk of more expensive accommodations, by restricting the number of students in a house. Of note, the sharing of facilities and the number of occupants present challenges in regard to privacy and safety for the people living there.

One of the respondents, from the City of Sudbury, elaborated on the theme of students’ rooming houses as follows:

Very often [in] public meetings people will say, ‘I don’t want ‘those’ types of people living in my neighbourhood.’ … We are talking about people who rent as opposed to people who own homes and … [these ideas] do come up in conversations and in public meetings. When we have the opportunity, we do like to remind the planning committee and council that all land-use planning matters are matters of human rights.

Death, 2008,Footnote15 is an important case in which the City of Oshawa and a neighbourhood developer successfully applied to have landlords ordered to stop using their properties as lodging houses for students. The joint applicants alleged that homeowners, including Death and others, were operating their properties as lodging houses, contrary to the city zoning bylaw that permits only single-detached dwellings in the lowest density residential zones. Both the developer and the city claimed that these houses were each being rented to four to nine postsecondary students and others on short-term leases, creating land-use conflict in the Windfields subdivision.

In 2009, the Ontario Superior Court of Justice (affirmed by the Court of Appeal) found that most of the properties had violated the bylaw.Footnote16 The decision hinged on the court’s interpretation of the bylaw’s term ‘single housekeeping establishment,’ the central feature of a single-detached dwelling. The court clarified that it meant a typical single-family arrangement or similar basic social unit – a reading fundamentally inconsistent with commercial properties being rented to groups of individuals bound together only by their common need for economical short-term accommodation.

Several Ontario cities have introduced, or are introducing, licensing systems to address the safety issues around students’ rooming houses. Courts have dismissed a few lawsuits opposing the licensing system and upheldFootnote17 both the system and the distinction between a single household dwelling vs. a rooming house. In the Waterloo case,Footnote18 the applicant applied for judicial review of the bylaw, asserting that the city’s fee to obtain a licence was discriminatory, based on family status, contrary to the Code. Waterloo’s Licensing Bylaw requires all low-rise residential rental units to obtain an annual licence to ensure safe accommodations. The court dismissed the case on the grounds that the bylaw applied throughout the city, without targeting any particular person or group of people, or affordable or unaffordable housing. Rather, it targeted specific types of dwellings.

In the Fodor case,Footnote19 a landlord who rented a building to students brought a challenge against the City of North Bay’s bylaw requiring a licence for rental properties with multiple and economically independent tenants. The landlord had been charged with operating a rental unit without a valid licence, but the challenge was based on age discrimination, a protected grounds. The court dismissed the challenge as students were not a protected group under Section. 2(1) of the Code or Section 15 of the Charter. The court also noted that student status was not a proxy for age, marital status, or family status.

4.2.4.3. Supportive housing

In the early 2010s, supportive housing, such as group homes, was emerging as a human rights issue because of multiple lawsuits and unrelenting pressure from a strong and active group of survivors of group homes (Finkler & Grant, Citation2011; Outhit, Citation2012; Agrawal, Citation2014; The City of Hamilton, Citation2019). In response, many cities, including Toronto, Smith Falls, Kitchener, and Sarnia, changed the definition of the use and associated minimum separation distancesFootnote20. London, St. Catharines, Oshawa, and Brantford also responded, though their responses varied. London removed the separation distance in its entirety. St. Catharines, which previously had a 300-metre separation distance for group homes, no longer has this usage in its zoning bylaw. Oshawa permitted group homes in a few limited zones. Brantford created other forms of group homes, like mini-group homes, or developed creative ways of separating them by using block density or radial distances. Guelph, Hamilton, and Peterborough, on the other hand, refused to revise or rescind the discriminatory sections of the zoning bylaws and still maintain their separation distances and other restrictions. Barrie is silent on separation distance but continues to carry the discriminatory definition of group homes.

Legal challenges against the City of Toronto’s definition of group homes and the associated minimum separation distance further illuminate the human rights dimension of the housing issue. In 2010, the Dream Team, a housing advocacy group of psychiatric treatment survivors, challenged Toronto’s proposed citywide zoning bylaw at the Ontario Human Rights Tribunal.Footnote21 They asserted that the ‘group home’ definition and the associated mandatory separation distance of 250 m were discriminatory. Group home residents were being singled-out, based on their mental health-related disabilities, for specific bylaw provisions that restricted their available housing options and negatively affected their dignity (Agrawal, Citation2014, Citation2017).

Agrawal, the first author of this paper, had been hired by the City of Toronto to consult on the case, for which he provided an expert review of the definition, the related mandatory separation distances, and the merits of the group homes bylaw vis-à-vis planning principles, the Code, and the Charter (Agrawal, Citation2013, Citation2014, Citation2017). He concluded that both the definition and the separation distances contravened Charter, Section 15, the Code, and Section 35(2) of the Ontario Planning Act, which prohibits ‘people zoning’ (Agrawal, Citation2014, Citation2017).

Based on this recommendation, in 2014, the city amended its definition of group homes, removed the attached minimum separation distance, and deleted the contentious phrase in the zoning that identified the characteristics of the people living in group homes. None of these aspects served planning purposes and were discriminatory by restricting housing locations. This case demonstrates that definitions and separation distances, common elements in municipal bylaws, have clear implications for access to housing, thereby making them subject to human rights legislation.

4.2.5. Indigenous people in the city development process

Indigenous issues, like freedom of expression in public spaces, were not discernable in the zoning bylaws we reviewed, nor were they brought up by our interviewees. However, several cases in the last decade or so highlight the struggles to deal with such issues. The two legal cases we discuss here exhibited little legal certainty about how and even whether municipalities should engage with First Nations peoples in the development process.

In the Montour case,Footnote22 an Indigenous group asked developers to seek their approval and pay a fee for any new development within the Brantford city limits on the grounds that they never surrendered the land on which the city was built. This claim was rejected by the court, calling into question the municipal duty to consult. In 2007, the Haudenosaunee Development Institute (HDI), an Indigenous body created by the Haudenosaunee people, likewise demanded that any development have its approval and that developers pay fees to HDI for projects to proceed. Montour and others, the respondents and supporters of the HDI, claimed that the land, once held by the Haudenosaunee people, was never surrendered; thus, they alone had the right to control its development.

Several developers refused to comply with the HDI’s demands. Montour and other protesters then began to hinder development in the city, such as through blockades on development sites and forced work stoppages. In response, Brantford city council passed two bylaws: one prohibited interference with construction on specific sites and the other prohibited unauthorized groups from demanding fees or tariffs from developers. The city then sought an injunction to restrain the respondents from acting in the now prohibited activities, although the respondents applied to quash the bylaws. However, the city’s injunction was granted and the respondents’ application was dismissed.

Next, the respondents appealed this dismissal on the basis that the bylaws infringed on their Charter rights and overstepped into federal jurisdiction. The Court of Appeal dismissed these claims with Judge Laskin stating the following:

Brantford has every right to pass legislation to control lawlessness and nuisances on its streets and on private property within its city limits. The Haudenosaunee, like all other citizens of Brantford, is subject to this by-law.Footnote23

In the Cardinal case,Footnote24 a developer applied to the City of Ottawa for permission to redevelop certain lands located on islands in the Ottawa River, within the city. After investigating, the city amended its official plan and enacted a zoning bylaw to allow the future development of these lands. Douglas Cardinal, one of the appellants, appealed the plan amendment and bylaw enactment at the OMB. He claimed the land in question as Indigenous land, obligating the federal and provincial governments to consult with the Algonquin people, and further argued that the board erred, with its insufficient consultations. When the appeal was unsuccessful, they appealed the decision to the Divisional Court, which found that the duty to consult was discharged while recognizing that the duty to consult at the municipal level is a mixed question of law. The court agreed with the board’s conclusion, stating the following:

The evidence shows that an extensive consultation process was undertaken by both the City and proponent and that the concerns of First Nations particularly the Algonquin have been adequately considered in the adoption of Official Plan Amendment (OPA) 143 and the enactment of Zoning Bylaw No. 2014-395. The overall development will incorporate elements/features that will celebrate and recognize Algonquin history and culture.Footnote25

Both decisions limit municipal involvement in carrying out the Crown’s duty to consult. However, the Cardinal case confirms that the municipality discharged the duty to consult adequately, which complicates when the onus lies with municipalities to take up the duty to consult.

4.3. Progress on the human rights front

Provincial and municipal governments have made substantial human rights progress (Agrawal, Citation2014, Citation2017, Citation2019, Citation2021). Numerous provincial examples exist: revising legislation to align with the Charter; providing legal aid to those who have experienced discrimination; and proposing to amend the Code to add other prohibited grounds of discrimination.

With respect to planning, Ontario amended its Planning Policy Statement (PPS) in 2014, and maintained these changes in the 2020 PPS, marking a major shift towards human rights. Specifically, the PPS states that it ‘shall be implemented in a manner that is consistent with the Ontario Human Rights Code and the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms,’ (Section 4.4) thus mandating that all municipalities in Ontario ensure their plans, policies, and bylaws are so aligned. However, Ontario is the only province that has so far done this. Notably, the 2014 changes followed Agrawal’s (Citation2013) recommendations, based on his aforementioned consultation on the City of Toronto case.

At the municipal level, Toronto’s city council showed new awareness of the primacy of human rights issues as they pertain to their own decisions and processes by establishing two important offices:

The Human Rights Office—established in 2013, provides advice, information, and assistance regarding human rights and accommodation issues involving city services and facilities.

Ombudsman Toronto—an arms-length agency, established in 2015, investigates administrative decisions, acts, and omissions of the municipal government that are unjust or discriminatory, as well as systems that poorly serve the public.

The shift in provincial policy is also evident in local appeal bodies, which now entertain arguments for or against minor variances and consents the basis of Code or Charter violations. In a 2018 case, arguably the first Toronto Local Appeal Body (TLAB)Footnote26 case, an appellant appealed, on human rights grounds, a refusal of minor variances by the city’s Committee of Adjustment. The appellant argued that the variances sought – to modify an existing home to provide for accessibility and other special needs of the owner – were consistent with the PPS. The TLAB agreed (Decision 17 279307 S45 36 TLAB), and reversed the decision of the Committee of Adjustment.

Many other municipalities have changed or are revisiting the problematic definitions of various forms of supportive housing, restrictions on their locations, contentious user characteristics, and minimum separation distances in zoning classes. For example, Toronto, Hamilton, Kitchener, and Sarnia removed arbitrary separation distances for group homes. Toronto removed the minimum separation distance required for the location of municipal shelters. The definition of ‘place of worship’ has been altered to account for all religions, and to allow more land-use zones and adjusted parking requirements. For instance, in 2010, Brampton revised its places-of-worship zoning bylaw to permit this usage in mixed commercial/industrial or light industrial zones areas, and to adjust parking requirements depending on whether the place of worship had seats or not.

As issues and challenges mounted over the years, other zoning bylaw revisions in many of our sample cities removed (a) the mandatory separation distance between supportive housing like group homes or municipal shelters, and (b) restrictions on locating places of worship in various zones.

5. Discussion

The discussion below explains the role of the OHRC and contextualizes the land-use issues within human rights law. We present some leading court decisions that triggered changes at the municipal level. We also consider some that may explain current violations.

5.1. Ontario human rights commission

The findings tell us the OHRC played a key role in increasing human rights awareness across Ontario, given its key mandate to educate the public about human rights and develop a culture of human rights in the province. The Commission engages in diverse educational activities and public awareness campaigns and activities, intended to reduce discrimination and decrease the incidence of formal human rights complaints, such as the following: fact sheets geared towards a sector in which human rights violations are rampant; speaking engagements; and community events focused on systemic prevention of Code violations. In 2020–2021, OHRC reported holding over 6000 public education and speaking events, which significantly increased its outreach. Most importantly, an overwhelming majority of community stakeholders agreed that OHRC maintained effective relationships with stakeholders (Ontario Human Rights Commission, Citation2012).

5.2. Right to adequate housing

The housing issues in Ontario (and across the country) continues unimpeded, partly due to judicial reluctance and legislative silence. For instance, in the Tanudjaja case,Footnote27 the Ontario Supreme Court rejected ‘inadequate housing’ as analogous grounds pursuant to Section 15 of the Charter. The court concluded that Section 7 of the Charter ‘does not provide a positive right to affordable, adequate, accessible housing and places no positive obligation on the state to provide it.’Footnote28 Housing and homelessness cases often relate to municipal decisions that affect the survival tactics of the homeless, like panhandling and the occupation of public spaces. Even in the AbbotsfordFootnote29 case, the court’s decision concerned whether government action deprived individuals of their liberty rights; it did not impose positive obligations on the government to fix the (homelessness) problem.

5.3. Duty to consult

How a municipality deals with the Crown’s duty to consult and the respect for treaty rights, remains unclear. We have noticed that in Montour,Footnote30 the courts did not hold the municipality responsible for ‘duty to consult,’ while in Cardinal,Footnote31 they acknowledged municipal duty to consult is a mixed question of law.

Case law, including HaidaFootnote32 and Rio TintoFootnote33 and most recently, the Neskonlith case,Footnote34 settle that municipalities, as non-Crown actors, do not have a role in the Crown’s duty to consult. Neskonlith stated that no municipality has an ‘independent constitutional duty to consult.’Footnote35 Imai and Stacey (Citation2014) however argue that it is counterproductive to allow a third party or non-Crown actor to act in a way that may interfere with the Indigenous rights in question. This would mean, practically, that any non-bound actor – such as a municipality – could act freely, despite the Indigenous band knowing that it is entitled to a duty to consult.

Flynn (Citation2022), and Hoehn and Stevens (Citation2018) take a similar stance. They rely on the Clyde River case,Footnote36 in which the SCC held that the Crown may rely on regulatory bodies (in this case, the National Energy Board or NEB, a form of administrative decision-maker) to satisfy the duty to consult. These scholars contend that the combination of the Clyde River, and the evolution of municipal autonomy means that third parties can be effectively considered to be an arm of the Crown and therefore hold a duty to consult and accommodate. It is imperative to note that municipal governments want to strengthen and develop mutually beneficial relations with the Indigenous governments in their vicinity. However, the judiciary and provincial governments provide little or no clear guidance on best practices.

5.4. Right to life, liberty and security

The federal regulatory changes emanated from legal decisionsFootnote37,Footnote38 under the Charter, Section 7, where the courts found that the benefits of SIS, methadone clinics, or marijuana use outweighed any potential detriment to the community or society. The Government of Canada shortly thereafter fully legalized recreational (or non-medical) cannabis industries, effective July 2018 (Government of Canada, Citation2017). Consequently, Canadian municipalities have faced the unprecedented challenge of determining how to create effective land-use schemes to regulate the cultivation, processing, retailing, and consumption of cannabis within their jurisdictions.

Three troublesome aspects inform this challenge: the short time frame municipalities have had to prepare for the anticipated legalization; the fact that cannabis was an illegal drug in Canada from 1923 until 2018 (Lafrenière & Raaflaub, Citation2004); and finally, that Canada is among very few countries to fully legalize the substance for both recreational and medical purposes (Edney & Agrawal, Citation2019). This legislative shift put Canadian municipalities at the forefront of modern urban policy related to recreational cannabis. As such, few policy ‘blueprints’ exist from which to model strategies.

Without points of reference, many Canadian urban planners and municipal policymakers had the difficult task of adapting their current land-use regulations to align with federal and provincial cannabis legislation. They had to uphold human rights, while balancing both the perceived opportunities and threats posed to their communities by this change. The newness of the land-use type and barriers in its social acceptance mean municipalities are struggling with what and how to integrate this into their zoning bylaws.

5.5. Freedom of expression

Freedom of expression has posed a significant challenge to municipalities (Blomley, Citation2011; Malik & Best, Citation2022). Section 2(b) of the Charter protects virtually all forms of expressive activity that convey meaning, irrespective of content, ‘however unpopular, distasteful or contrary to the mainstream.’ The only exempted form of expressive activity that is not protected by Section 2(b) is actual violence. Several SCC decisions, including Irwin Toy,Footnote39 identified the values underlying the rationale for constitutionally protecting free speech.

Multiple cases in Toronto, and recent Charter challenges against Edmonton,Footnote40 Grande Prairie,Footnote41 and other Canadian cities have tested municipalities’ abilities to regulate freedom of expression. For example, the American Freedom Defense Initiative’s ads made explicit references to the so-called honour killings of Muslim girls. Such advertisements have tried the efficacy of cities’ administrative approval processes, highlighting the need to be more vigilant by proactively vetting advertising material to avoid protracted legal entanglements. Municipalities face special challenges to determine what expression may be inappropriate for their communities: what might be offensive to ‘the moral standards of the community’Footnote42 and how to set limits on expression on public properties where necessary.

5.6. Leading judicial decisions on definition of use in zoning bylaw

Although not linked with rights directly, the landmark Bell (1979)Footnote43 case spawned challenges to bylaws for their unreasonableness or discriminatory nature (Leisk, Citation2012; Agrawal, Citation2013). The case challenged the Borough of North York’s bylaw in which dwelling units were defined for use by individuals (no more than two) or families (more than two people bound by blood, marriage, or adoption). The appellant was a tenant in a detached duplex unit who lived with two other persons unrelated to him. He was charged with violating the bylaw.

The SCC held that ‘adopting “family” as defined as the only permitted use of a self-contained dwelling unit is oppressive and unreasonable.’Footnote44 Therefore, the bylaw was found to be ultra vires of the municipality under the provisions of Ontario’s Planning Act,Footnote45 in that municipalities had the right to control the use of properties but not who used them. This decision had profound implications on municipal planning, leading to changes to provincial planning acts as well as municipal bylaws across the country. Subsequent to Bell, however, case law does not take such a strong position (Agrawal, Citation2013). Zoning definitions that refer to users or personal attributes have been upheld subsequently by the courts. Such examples are SmithFootnote46 and FaminowFootnote47 which were decided after Bell. Given that the Bell decision came from the SCC – whereas the decisions in Smith and Faminow came from lower courts – the Ontario Supreme Court and British Columbia Court of Appeal, respectively—Bell technically remains the leading case in the area of people zoning in municipal law.

The above discussion makes it clear that Ontario has come a long way in protecting its citizens’ rights in the city. The judiciary has further clarified, applied, and even expanded the scope of rights in relation to various aspects of city life – with some exceptions, of course. These relate particularly to the provision of adequate housing and to municipal duties and responsibilities towards the Indigenous Peoples of Canada. In response, Ontario municipalities have taken numerous actions: reviewing, revising, or even rescinding existing bylaws and practices; creating new land-use classes; or revising existing zoning or other municipal bylaws to accommodate new resulting land-uses (Agrawal, Citation2021). It is, however, clear that Ontario municipalities still struggle to understand fully their legal and moral obligations and keep pace with the ever-evolving judicial interpretations of the Charter and changes to the Code.

6. Conclusion

In responding to the three key questions laid out in the introduction, this study argues that the increase in human rights complaints is rooted in city residents’ heightened awareness of related rights and issues. This can be partly attributed to the awareness campaign launched by the OHRC and, of course, the relative ease of seeking a remedy through the Human Rights Tribunal and the availability of government-sponsored legal support to individuals facing human rights challenges.

Ontario municipalities face multiple issues tied to restrictions on locating places of worship, what is allowed in public spaces, locations of drug and addiction facilities, and the municipal responsibility to consult with Indigenous groups regarding any new developments in the city. Together, these issues paint a murky picture of the right to adequate housing in the absence of constitutional guarantees. As well, we see judicial reluctance to require municipalities to take on the Crown’s duty to consult with Indigenous groups, along with municipal challenges to keep public spaces inclusive and free of discrimination.

Recent federal legislative shifts gave rise to a new set of human rights challenges arising from locating SIS, methadone clinics, and cannabis dispensaries in the municipal fold, where few precedents exist to help municipal planners. These issues persist along with perennial and outstanding issues of adequate and affordable housing and discriminatory elements of zoning bylaws, such as the inclusion of user characteristics and minimum separation distances.

Nevertheless, over the years, both the Province of Ontario and its municipalities have made significant progress on the human rights front. For instance, in 2014, the province revised the PPS to require all municipalities to abide by the Code and the Charter. The province also made access to justice easier by creating the Human Rights Legal Support Centre that provides legal advice to people making complaints.

Concomitantly, municipalities in Ontario have amended their bylaws to align them with the Code and the Charter. Consequently, many significant changes have occurred, especially in the provision of group homes and municipal shelters, and improved accessibility in the transit system. Cities have also approved the keeping of livestock within the city limits. Some municipalities engaged in incremental learning through pilot studies, while others pursued the ‘wait and see’ approach. Worse, a few created surreptitious ways in zoning to avoid legal exposure or refused to make any changes defying their constitutional or quasi-constitutional obligations. Most potential human rights and Charter challenges in Ontario municipalities still involve the prohibition or exclusion of various forms of supportive housing and congregate living, and restrictions on their locations, as well as the problematic inclusion of user characteristics in the zoning class definitions.

Plenty more remains to be added to the body of knowledge in this emerging area of scholarship. Future studies could focus on other Canadian provinces to evaluate their state of human rights and municipal response. Comparisons and contrasts among provinces will lay out a better perspective on where Canada is heading in the coming years.

Acknowledgment

We thank other members of the team who contributed immensely to the project. These members are: Anthony Soscia, Debadutta Parida, Hayley Wasylycia, Jahaan Premji and Fiona McGill.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, s 15, Part I of the Constitution Act, 1982, being Schedule B to the Canada Act 1982 (UK), 1982, c 11.

2. Constitution Act, 1982, s 35, being Schedule B to the Canada Act 1982 (UK), 1982, c 11.

3. Analogous grounds are additional prohibited grounds of discrimination, over and above those enumerated in Section 15 of the Charter. The courts can interpret the Charter broadly to arrive at these grounds.

4. 16 cities were initially included in the study, one in each of the province’s 16 CMAs. However, access to information about four of the cities proved challenging, so we eventually cut them from the study. A CMA is a statistical geographic unit of a population of at least 100,000 created by Statistics Canada, which is formed by one or more adjacent municipalities centred around a core municipality.

5. Any changes in legislation, bylaws, or jurisprudence since 2019 have been updated.

6. The number of cases heard at the HRTO varied from year to year. The numbers were substantially lower in 2020 and 2021 when the pandemic was at its peak.

7. An overlay is an additional set of regulations applied to an area of the city on top of existing zone-related regulations.

8. Loralgia Management Ltd. v. Oshawa (City), [2002] O.M.B.D. No. 1155 [Loralgia Management].

9. Oshawa (City) v. Loralgia Management Ltd., 2004 CanLII 76,826 (ON SCDC).

10. Congregation des temoins de Jehovah de St-Jerome-Lafontaine v. Lafontaine (Municipality). (2004). SCC 48, 2 SCR 650 [Lafontaine].

11. Satnam Anami of Canada Inc v Brampton (City), [2008] OMBD No 1139, 60 OMBR 459 [Satnam Anami].

12. 1140971 Ontario Ltd v Toronto (City), [2010] OMBD No 595, 66 OMBR 91 [1140971 Ontario Ltd].

13. Batty v. Toronto (City), 2011 ONSC 6862 [Batty].

14. R v Bell, 2 SCR 212, 98 DLR (3d) 255 [Bell cited to SCR]. It is important to note that the Bell case was decided before the Charter came into effect.

15. The Neighbourhoods of Windfields Limited Partnership v Death, 2008 Carswell, Ont 5025, [2008] O.J. No. 3298 [Death, 2008].

16. The Neighbourhoods of Windfields Limited Partnership v Death, 2009 ONCA 277 [Death, 2009].

17. 2161907 Ontario Inc v. City of St Catharines, 2010 ONSC 4548; Good v. Waterloo (City) (2004), 2004 CanLII 23,037 (ON CA), 72 O.R. (3d) 719 (Ont. C.A.); Kritz v City of Guelph, 2016 ONSC 6783.

18. 1736095 Ontario Ltd. v Waterloo (City), 2015 ONSC 6541 [Waterloo].

19. Fodor v North Bay, 2018 ONSC 3722 [Fodor].

20. Separation distance is a regulation in zoning intended to control the unwanted land-use impacts of a specific type of property on the surrounding properties and on the city as a whole. It is also used to manage the potential overconcentration of certain types of land-use, services, or housing in a neighbourhood.

21. The Dream Team v. The City of Toronto, 2012 HRTO 25 [Dream Team].

22. City of Brantford v. Montour et al, 2010 ONSC 6253 [Montour].

23. Brantford (City) v Montour, 2013 ONCA 560 at para 94.

24. Cardinal v Windmill Green Fund LPV, 2016 ONSC 3456 [Cardinal].

25. Supra note 24.

26. The Toronto Local Appeal Body (TLAB) is an independent, quasi-judicial tribunal that adjudicates land-use appeals in Toronto.

27. Tanudjaja v Canada (Attorney General), 2013 [Tanudjaja].

28. Ibid at para 81.

29. Abbotsford (City) v. Shantz. (2014). BCSC 2385, [2015] BCWLD 1393 [Abbotsford].

30. Supra note 22.

31. Supra note 24.

32. Haida Nation v British Columbia (Minister of Forests), [2004] 3 SCR 511 [Haida].

33. Rio Tinto Alcan Inc. v Carrier Sekani Tribal Council, 2010 SCC 43 [Rio Tinto].

34. Neskonlith Indian Band v Salmon Arm (City), 2012 BCCA 379 [Neskonlith].

35. Ibid at para 54.

36. Clyde River (Hamlet) v Petroleum Geoservices Inc., 2017 scc 40 (CanLII).

37. Canada [Attorney General] v PHS Community Services Society, 2011.

38. R v Smith, 2015 SCC 34, [2015] 2 SCR 602; Allard v Canada, 2016 FC 236, 263 ACWS (3d) 358.

39. Irwin Toy Ltd. v Quebec (Attorney General) [1989] 1 S.C.R. 927 [Irwin Toy].

40. American Freedom Defense Initiative v Edmonton (City), 2016 ABQB 555, at para 90 [AFDI].

41. Canadian Centre for Bio-Ethics v Grande Prairie (City), 2016 ABQB 734, [2017] 4 WWR 182 [Grande Prairie].

42. American Freedom Defense Initiative v Edmonton (City), 2016 ABQB 555, at para 71.

43. R v Bell, 2 SCR 212, 98 DLR (3d) 255 [Bell cited to SCR].

44. Ibid at 213.

45. Planning Act, RSO 1990, c P.13.

46. Smith v Tiny (Township), 107 DLR (3d) 483, 1980 CarswellOnt 489 .[Smith]

47. Faminow v North Vancouver (District), 61 dlr (4th) 747, 24 bclr (2d) 49 .[Faminow]

References

- 1140971 Ontario Ltd v Toronto (City). (2010) OMBD No 595, 66 OMBR 91.

- 1736095 Ontario Ltd. v Waterloo (City). (2015) ONSC 6541.

- 2161907 Ontario Inc v. City of St Catharines, (2010) ONSC 4548.

- Abbotsford (City) v. Shantz. (2014). BCSC 2385, [2015] BCWLD 1393 [Abbotsford].

- Agrawal, S. (2009) New ethnic places of worship and planning challenges, Plan Canada, Special Edition, March, pp. 64–67.

- Agrawal, S. (2013) Opinion on the provisions of group homes in the city-wide zoning bylaw of the City of Toronto. Available at https://cms.eas.ualberta.ca/UrbanEnvOb/wp-content/uploads/sites/21/2017/12/group-homes-opinion-Agrawal.pdf

- Agrawal, S. (2014) Balancing municipal planning with human rights balancing municipal planning with human rights: A case study, Canadian Journal of Urban Research, 23(1), pp. 1–20.

- Agrawal, S. (2017) Human rights 101 for planners, Plan Canada, (Summer), 57(2), pp. 6–9.

- Agrawal, S. (2019) Right to the city: Human rights and Canadian cities, Plan Canada, 59(1), pp. 209–214.

- Agrawal, S. (2021) Human rights and the city: A view from Canada, Journal of the American Planning Association, 87(1), pp. 3–10. 10.1080/01944363.2020.1775680.

- Agrawal, S. (2022) Human rights and Canadian municipalities, in: S. Agrawal (Ed) Rights and the City: Problems, Progress and Practice (Edmonton: University of Alberta Press). 105–131.

- American Freedom Defense Initiative v Edmonton (City). (2016) ABQB 555.

- Batty v. Toronto . (2011) ONSC 6862.

- Bell v. The Queen. (1985) 1 S.C.R. 594.

- Blomley, N. (2011) Rights of Passage: Sidewalks and the Regulation of Public Flow (New York, NY: Routledge).

- Brantford (City) v Montour. (2013) ONCA 560.

- Canadian Centre for Bio-Ethics v Grande Prairie (City). (2016) ABQB 734, [2017] 4 WWR 182.

- Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, s 15, Part I of the Constitution Act, 1982, being Schedule B to the Canada Act 1982 (UK), 1982, c 11.

- Cardinal v Windmill Green Fund LPV. (2016) ONSC 3456.

- City of Brantford v. Montour. (2010) ONSC 6253.

- Clement, D. (2016) Human Rights in Canada: A History (Waterloo: Wilfrid Laurier University Press).

- Congregation des temoins de Jehovah de St-Jerome-Lafontaine v. Lafontaine (Municipality). (2004) SCC 48, 2 SCR 650 [Lafontaine].

- Constitution Act, 1982, s 35, being Schedule B to the Canada Act 1982 (UK), 1982, c 11.

- Donnelly, J. (2013) Universal Human Rights in Theory and Practice (Ithaca: Cornell University Press).

- Edney, J., & Agrawal, S. (2019) Planning for federal legalization of recreational cannabis industries: An analysis of municipal land use/zoning strategies in Alberta. Paper presented at the ACSP conference, Greenville, SC.

- Finkler, L., & Grant, J. L. (2011) Minimum separation distance bylaws for group homes, Canadian Journal of Urban Research, 20(1), pp. 33–56.

- Flynn, A. (2022) Whose right to what city? Indigenous rights amidst claims for constitutionally empowered cities, in: S. Agrawal (Ed) Rights and the City: Problems, Progress, and Practice (Edmonton: University of Alberta Press). 1–25.

- Fodor v North Bay. (2018) ONSC 3722.

- Good v. Waterloo (City). (2004), CanLII 23037 (ON CA), 72 O.R. (3d) 719 (Ont. C.A.).

- Government of Canada. (2017) Canada takes action to legalize and strictly regulate cannabis, Health Canada. Available at https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/news/2017/04/canada_takes_actiontolegalizeandstrictlyregulatecannabis.html (accessed 26 June 2022).

- Greene, I. (2014) The Charter of Rights and Freedoms: 30+ Years of Decisions That Shape Canadian Life (Toronto: James Larimer Company Ltd).

- Haida Nation v British Columbia (Minister of Forests), [2004] 3 scr 511 [Haida]

- Hoehn, F., & Stevens, M. (2018) Local governments and the Crown’s duty to consult, Alberta Law Review, 55(4), pp. 971. 10.29173/ALR2483.

- Howe, R. B. (1991) The evolution of human rights policy in Ontario, Canadian Journal of Political Science/revue Canadienne de Science Politique, 24(4), pp. 783–802. 10.1017/S0008423900005667.

- Imai, S., & Stacey, A. (2014) Municipalities and the duty to consult Aboriginal peoples: A case comment on Neskonlith Indian Band v. Salmon Arm (City), UBC Law Review, 47(1), pp. 293–312.

- Kritz v City of Guelph. (2016) ONSC 6783.

- Kvale, S. (2011) SAGE Research Methods. London: SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Lafrenière, G., & Raaflaub, W. (2004). Bill C-10: An act to amend the contraventions act and the controlled drugs and substances act. Available at https://lop.parl.ca/Content/LOP/LegislativeSummaries/37/3/c10-e.pdf

- Leisk, S. (2012) Zoning by-laws: Human rights and charter considerations respecting the regulation of the use of land, Municipal Lawyer, 53(1), pp. 14–17.

- Loralgia Management Ltd. v. Oshawa (City). (2002) O.M.B.D. No. 1155.

- Malik, O. P., & Best, S. (2022) The dangers of allowing “othering” speech in a city’s public spaces, in: S. Agrawal (Ed) Rights and the City: Problems, Progress, and Practice (Edmonton: University of Alberta Press). 209–233.

- Malterud, K. (2012) Systematic text condensation: A strategy for qualitative analysis, Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 40(8), pp. 795–805. 10.1177/1403494812465030.

- Morton, F. L. (1987) The political impact of the Canadian charter of rights and freedoms*, Canadian Journal of Political Science/Revue Canadienne de Science Politique, 20(1), pp. 31–55. 10.1017/S0008423900048939.

- Municipal Government Act, RSA 2000, c M-26

- Neskonlith Indian Band v Salmon Arm (City), 2012 bcca 379 [Neskonlith].

- Ontario Human Rights Commission. (2005) Family status and the Ontario human rights code. Available at https://www.ohrc.on.ca/en/human-rights-and-family-ontario/family-status-and-ontario-human-rights-code

- Ontario Human Rights Commission. (2012) In the zone: Housing, human rights and municipal planning. Available at https://www.ohrc.on.ca/en/zone-housing-human-rights-and-municipal-planning

- Ontario Human Rights Commission. (2013) Human rights: The historical context. Available at appendix-2-%E2%80%93-human-rights-historical-contexturlCtrl+Clicktofollowlink”element-type=“link”ref-type=“DOI”aid=“0x24v578ay36s1i”icoretag=“uri”ia_version=“0”>https://www.ohrc.on.ca/en/teaching-human-rights-ontario-guide-ontario-schools/appendix-2-%E2%80%93-human-rights-historical-context

- Oshawa (City) v. Loralgia Management Ltd., 2004 (ON SCDC)

- Outhit, J. (2012, September 25) Kitchener council drops restrictions on group homes, The Record. Available at https://www.therecord.com/news/waterloo-region/2012/09/25/kitchener-council-drops-restrictions-on-group-homes.html

- Planning Act, RSO 1990.13.

- Rio Tinto Alcan Inc. v Carrier Sekani Tribal Council, 2010 SCC 43 [Rio Tinto].

- R v Bell, 2 SCR 212, 98 DLR (3d) 255 [Bell cited to SCR].

- Sandel, M. (1998) Liberalism and the Limits of Justice (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

- Satnam Anami of Canada Inc v Brampton (City). (2008) OMBD No 1139, 60 OMBR 459

- Sen, A. (2004) Elements of a theory of human rights, Philosophy & Public Affairs, 32(4), pp. 315–356. 10.1111/j.1088-4963.2004.00017.x.

- Sen, A. (2006) Human rights and capabilities, Journal of Human Development, 6(2), pp. 151–166. 10.1080/14649880500120491.

- Smithey, S. I. (2001) Religious freedom and equality concerns under the Canadian charter of rights and freedoms, Canadian Journal of Political Science/Revue Canadienne de Science Politique, 34(1), pp. 85–107. 10.1017/S0008423901777827.

- Smith v Tiny (Township), 107 DLR (3d) 483, 1980 CarswellOnt 489.

- The City of Hamilton. (2019) Residential facilities and group homes: Human rights and the zoning by-laws within the urban area [Discussion Paper]. Available at https://www.hamilton.ca/sites/default/files/media/browser/2019-04-24/residential-care-facilities-group-homes-urbanarea-july2019.pdf

- The Dream Team v. The City of Toronto. (2012) HRTO 25.

- The Neighbourhoods of Windfields Limited Partnership v Death. (2009) ONCA 277.