ABSTRACT

Transportation and accessibility remain an important consideration in land use planning decision-making if modal shifts towards sustainable forms of transport are to be encouraged. Land value capture (LVC) mechanisms which gather developer contributions can provide new transport infrastructure which supports such a shift. Within England, this has traditionally been pursued through negotiated section 106 agreements, yet data suggest a significant decline in the value of these contributions for transport measures since 2010. This paper investigates the reduction to understand the reasons behind it and then considers the resulting implications for policy and LVC practices using a qualitative synthesis.

Introduction

Transportation is an important component within urban planning, generating damaging externalities including increased congestion, air pollution and deepening social inequalities if unmanaged (Banister, Citation2001, Citation2005). Urban planners can often resolve these issues by employing various land value capture (LVC) mechanisms which redistribute wealth from developers towards new or enhanced public infrastructure (Dunning & Lord, Citation2020; OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development), Citation2022), but these actions require integration between land use and transport planning (Smith, Citation2021). This integration is recognised as problematic; both disciplines have developed as separate professional activities and are usually practiced at different administrative scales by disparate bodies, which risks the fostering of policy silos and blinkered mentalities amongst planners in practices termed ‘the politics of mobility’ (Vigar, Citation2002; Fischer et al., Citation2013). Such problems require researchers to study how and why policy mechanisms are affected by various multifaceted and interlinked contextual and intrinsic forces, yet there is no agreed or accepted approach for pursuing this holistically (Smith, Citation2018). To these ends, this paper advances a new D=CIB (Delivery = Context, Intelligence and Behaviour) framework for fathoming the complex relationships affecting the outcome of policy interventions in urban planning. By deciphering what works (and equally does not), how and why, this framework is particularly informative at depicting thorny implementation issues in urban planning.

UK transport policy underwent a paradigm shift during the 1990s as the ‘predict and provide’ mentality of a massive road building programme was debunked in favour of ‘plan-monitor-manage’ approaches that advanced controlling demand through modal shifts towards sustainable transport (defined broadly here as egalitarian and/or low carbon modes) (Banister, Citation2001; Vigar, Citation2002). Land use planning is an important partner in delivering this agenda, with central government policies and guidance since the mid 1990s directing local authority planners in England to ensure new developments are accessible by a range of transport modes (Headicar, Citation2009; DCLG (Department of Communities and Local Government), Citation2012). To these ends, transport users are considered consumers and offered options in the hope they select the most sustainable (Smith, Citation2021). Land use planning helps deliver this agenda in two principal ways; firstly, by locating new development in locations already accessible by a range of transport modes (Banister, Citation2005), and secondly, by creating new sustainable transport capacity by using LVC to harvest planning gain and pay for new infrastructure (Enoch et al., Citation2004). This paper focuses on the delivery of this second element.

Planners can use LVC to provide a range of infrastructure and services supporting sustainable transport modes, from cycle parking, footpaths, and bus stops to new railway stations and trainlines (Enoch et al., Citation2004; Headicar, Citation2009). Since the 1980s, UK planners have employed negotiated settlements commonly known as section 106 agreements (s106) after the relevant section of the 1990 Town and Country Planning Act to pursue these provisions (Crook, Citation2016). Use of s106 for transport measures requires co-operation between land use planners and their transportation counterparts to identify and justify requirements (Smith, Citation2021). Such agreements are also regulated and controlled by central government to the extent the approach is characterised as overly centralised (Raynsford, Citation2018), thus jarring with notions in implementation theory suggesting delivery is an inherently local activity ill-suited to top-down management (Smith, Citation2018).

Recent research reveals a significant decline in funding from s106 towards transport measures in England; the proportion of revenue going towards transport schemes fell from £420 m; 11% of the total sum of all contributions in 2011/12 to just £294 m; 2% in 2018/19 (Lord et al., Citation2020). This paper investigates reasons for this and considers their implications for LVC practices.

Land value capture in the English planning system

LVC persists as a somewhat controversial mechanism for harvesting planning gain or betterment; the uplift in land value occurring when planning permission is granted (Crook, Citation2016). The presence of a discretionary planning system in the UK offers planners the freedom to interpret planning policies and negotiate concessions with developers to ensure approved development accords with local and national planning policies (Moore, Citation2002; Booth, Citation2012). Since the 1980s, local authority planners have negotiated s106 settlements (either financial or in-kind contributions) to cover costs from externalities (Wyatt, Citation2017), such as financing a broad range of transport projects which facilitate accessibility by sustainable modes and so encourage a modal shift away from cars (Smith, Citation2021). Central government regulates s106 though tests of necessity enshrined in nationally set planning frameworks and guidance which planners are obliged to follow (DoE (Department of the Environment), Citation1995; ODPM (Office of the Deputy Prime Minister), Citation2005; DCLG, Citation2012). A 2005 update also permitted pooling of contributions from several developers towards a project (Lane & Wells, Citation2006), for costs of infrastructure works can exceed what individual developers might reasonably expect to contribute (Enoch et al., Citation2004; CIHT (Charted Institution of Highways and Transportation), Citation2019).

Since 2010, a new Community Infrastructure Levy (CIL) offers an alternative LVC mechanism in England (Wyatt, Citation2017; Crook & Whitehead, Citation2019). Unlike s106, CIL is essentially a hypothecated development tax (usually expressed as £x per m2) and revenue funds a predetermined list of strategic infrastructure projects, such as Crossrail in London (GLA (Greater London Authority), Citation2016). CIL does not resolve site-specific concerns (like accessibility) nor provide affordable housing which still requires s106 (Crook, Citation2016). Consequently, CIL does not directly replace s106 (Lord et al., Citation2020), and not all local authorities have adopted CIL (Burgess & Monk, Citation2016; Raynsford, Citation2018). Planning conditions remains a third LVC mechanism. Planners (and elected councillors who have final authority) attach conditions when approving planning proposals which can restrict operations of a development and/or require undertakings to host-specific measures (Cullingworth & Nadin, Citation2006). Pertinent transport examples include providing cycle parking or adopting green travel plans which commit end users to adopt strategies encouraging modal shifts towards sustainable transport by customers and employees (Rye et al., Citation2011). Unlike s106 and CIL, planning conditions do not involve financial settlements and are restricted to on site matters (Moore, Citation2002).

Integration is a recurring problem for land use and transport are typically administered and governed separately in England (Fischer et al., Citation2013). For instance, in city regions and two tier local authority areas, transport is planned at strategic levels while land use planning decisions (and sometimes highways management) are taken by district authorities (Glaister et al., Citation2006). Even in single tier, unitary authorities transport is typically administered in a separate department to land use planning as they are different professions. These arrangements contrast with other calls on s106, like affordable housing which is commonly a land use planning responsibility (Lord et al., Citation2020). Use of s106 for transport therefore requires co-operation and can generate conflict in terms of contrasting/incompatible needs and priorities (Vigar, Citation2002; Smith, Citation2021). In one notable case, planners failed to collect any s106 contributions towards the unfortunate Merseytram light rail scheme in Liverpool, which inadvertently assisted its demise from a funding shortfall (Smith et al., Citation2014).

Issues and research into LVC

Numerous issues arise through practicing LVC in England. Notably, it is reliant on financial viability and an area’s underlying economic conditions with proposals in more prosperous markets typically contributing substantially more than those elsewhere (Baker & Hincks, Citation2009). This results in significant regional disparities, with most developer contributions coming from lucrative property markets in London (Lord et al., Citation2020, Citation2022), while no mechanism exists to redistribute contributions towards disadvantaged areas in need of infrastructure investment (Raynsford, Citation2018).

These issues are also ingrained, with planners in areas making limited use of s106 powers having little opportunity to gain experience in negotiation or finesse their skills (Dunning et al., Citation2019). For instance, an investigation into green travel plans found planners were reluctant to use s106 to monitor and enforce these plans in the fear that these processes were time consuming and too complex (Rye et al., Citation2011). Likewise, planners need to be able to see through smokescreens created by developers seeking to reduce their contributions by embroidering financial viability concerns (Lord et al., Citation2019). Collecting developer contributions using negotiated settlements has subsequently been framed as planning games (Lord, Citation2012). Here, games are seemingly won and lost on the experience and confidence of the different players to manipulate their opponents into conceding ground (Lord et al., Citation2019). Planners are also subjected to rules rooted in planning cultures and local authority expectations on development and inward investment in playing these games (Dunning et al., Citation2019; Buck, Citation2021). For example, local authorities may fear jeopardising development offering much needed jobs and housing by asking for contributions (Smith, Citation2021).

Considerable research has been conducted on LVC in England. Most scholars have examined LVC through the lens (or combined lenses) of affordable housing (Crook et al., Citation2016, Citation2021; Lord et al., Citation2022), operation of mechanisms generally (Dunning et al., Citation2019; Crook & Whitehead, Citation2019; Lord et al., Citation2020), ecological measures (Buck, Citation2021) or development and uptake of CIL (Burgess & Monk, Citation2016; Wyatt, Citation2017; Crook et al., Citation2021). Perhaps surprisingly, little of this recent research looks specifically at transport and it only features tangentially within other studies (Rye et al., Citation2011; Smith et al., Citation2014), or as a project related overview on an international scale (OECD, Citation2022). Transport has several complex and unique features in its application with LVC; it focuses on accessibility at both a site specific and strategic levels whilst is also subject to considerable integration challenges. This paper subsequently completes a significant knowledge gap on the application of LVC practices in England, the results of which will also enlighten scholars of LVC elsewhere through processes of refutation and understanding what works (and does not work), how and why (Booth, Citation2012). International interest is growing in this area as countries (including Holland and Spain) also consider pursuing negotiated LVC agreements (Samsura et al., Citation2015; Gozalvo Zamorano & Muñoz Gielen, Citation2017).

Vicious & Virtuous Cycles

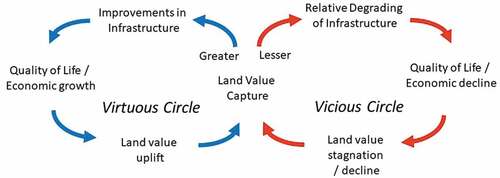

LVC can result in virtuous and vicious circles () (Raynsford, Citation2018; Lord et al., Citation2019, Citation2022). Virtuous circles arise because increases in land value are captured and harvested by planners and used to improve local infrastructure in an area. These improvements (eg to accessibility) lift both quality of life for residents and improve economic performance of businesses. Such enhancements escalate demands for property, which inflates prices. Developers are thus encouraged to invest in further proposals from which extra contributions are extracted, thus establishing a virtuous circle.

Figure 1. Virtuous and vicious circles (Lord et al., Citation2019).

In contrast, a vicious circle emerges where planners fail to harvest any increases in land value from development for investment in an area, possibly because there is little value to be captured without making development unviable. This failure to invest can cause infrastructure to degrade or stagnating and accompanying uplifts in quality of life and economic activity fail to materialise, thereby leading to inertia in land values. In terms of transport, poor accessibility might typically constrain property prices, as it constricts journey horizons. Developers are subsequently unwilling to invest, and when they do, lower returns diminish potential contributions to the point LVC becomes unviable.

Within the virtuous/vicious circle propositions, the key tipping point (where either path might be taken) is when planners attempt (or should attempt) to utilise LVC. What happens at this critical juncture is of immense interest to researchers, but there is no model or framework to investigate the issue (Dunning & Lord, Citation2020). Instead, researchers have looked towards behavioural insight approaches on the influences and motivations for individual actions (Lord et al., Citation2019), or new institutional models considering ontological dynamics between structure and agency (Vigar, Citation2002; Smith, Citation2014). These views, however, consider complex implementation processes in isolation, and we argue new holistic frameworks are needed.

Towards a D=CIB (Delivery = Context, Intelligence and Behaviour) framework

To these ends (and taking inspiration from the PARIHS framework used in healthcare sciences to explain complex implementation practices (Rycroft-Malone et al., Citation2004)), we propose a D=CIB logical model for exploring implementation in urban planning. This model explains the theory of change surrounding planners use of LVC mechanisms. It is expressed as Delivery (D) being a function of Contexts (C), Intelligence (I) and Behaviour (B). There is strong overlap between the elements as they feed off one another.

Delivery is fundamentally about policy intervention outcomes. No profession to success is made in the framework, so it accepts bad outcomes can result from policy interventions just as improvements can also be achieved. It is subsequently down to the researcher to express an opinion on the success or otherwise of delivery.

Contexts are multi-layered and multifaceted constructs with many alternative dimensions and tiers that are inherently structural, yet which interlink and work for or against one another. Different tiers of government are the most intrinsic example, such as local, regional and national decision-making contexts (Gallent, Citation2008). Yet there are also spatial and temporal contexts; spatial reflecting different scales (such as community boundaries) and temporal referencing the timescales over which interventions play out (Hillier, Citation2011), whilst relativity means policy interventions can present differently depending upon the stance one examines them (Clifford & Tewdwr-Jones, Citation2014). Likewise, the extent to which policies and mechanism are imposed from the top or grow from the ground is a further consideration (Smith, Citation2018). Other contexts may be subject related, such as the regulatory/legal context which dictates and controls actions (Rydin et al., Citation2021), and fiscal contexts which determine what action can be afforded or are required to meet budget limitations (Banister, Citation2001). Overall, contexts incorporate a broad range of resolute structures which determine and shape actions, but which might also display a dynamic in being subject to revision and reform through actions and events.

Intelligence is referenced as an information or evidential construct; particularly materials brought forward to inform and support the case for actions (whereupon it becomes evidence) (Davoudi, Citation2006). Examples here include data supporting the need for measures or defining the limits of what is achievable/viable. Within urban planning, intelligence is developed and presented through collaboration with numerous actors, including scientists, officials, charities, pressure/community groups and private interests (Holt & Baker, Citation2014). Knowledge may subsequently be presented in different formats, to contrasting methodologies and lack consistency and coherence (Solesbury, Citation2002; Davoudi, Citation2006). Simultaneously, uncertainty persists where knowledge is incomplete, incoherent or is missing (Davoudi, Citation2006; Snowden & Boone, Citation2007), while intelligence can prove unhelpful by delaying or distorting decision-making (Nutley et al., Citation2003).

Finally, behaviour references how individuals react and respond to various contextual and intelligence influences. This might include how context informs cultures and priorities which determine behavioural responses (Booth, Citation2012), and could influence what intelligence is picked up and acted upon via the ‘science of muddling through’ as actors lack time to read and reflect on all available materials (Lindblom, Citation1959; Cairney, Citation2022). Management of these issues appeals to planners’ professional judgements and subjectivity in informing their reactions (Vigar, Citation2012). Emotion can prove key to ascertaining behaviour, particularly how one responds to fears of uncertainty and risk (Ferreira, Citation2013; Sturzaker & Lord, Citation2018). Personality and the extent to which one sees oneself as a liberal enabler or an insular regulator can also determine one actions (Morphet et al., Citation2007); for example, as a trendsetter embracing change and innovation or as a hesitant laggard (Rogers, Citation2003). Behaviour is therefore synonymous with individual action and the ways actors and players opt to wield power and respond to conditions.

We propose contexts, intelligence and behaviour are interlinked in delivery chains (see Pressman & Wildavsky, Citation1973), so interact, inform and influence each other through varying processes which require understanding. To these ends, important questions persist as to the strengths of these linkages (a chain is only as strong as its weakest links) and the extent to which links couple together (do they jar, sit comfortably or too loose?).

Methodology

Our investigation uses a qualitative methodology and synthesis to interpret (from first-hand accounts of planning practice) why s106 contributions for transport have fallen, as part of an ESRC funded study into financing clean air using LVC. We approached 40 local authority planning departments across England for a semi-structured interview on how they employed s106 and in what way use of these agreements had changed since 2010 in relation to transport. Twenty did not respond to these requests and another 9 declined as officers said they either lacked time or felt unqualified to answer our questions. From the 11 local authorities across England who consented to help, we conducted an online interview with an officer between January to March 2022 (another provided a written response). Our interviewees worked on s106 and identified as planners, engineers, solicitors, policy officers and managers. Each interview was conducted and recorded using Microsoft Teams and were later transcribed verbatim. All participants were assured anonymity.

Transcripts were analysed through a layered synthesis (, see Noblit & Hare, Citation1988). This involved 1) placing the accounts into an interpretive order by identifying overarching themes which were constructed by reading the transcripts into one another, and asking ‘is this the same? What is different?’, 2) attributing these themes within the D=CIB framework as examples of the different components, 3) reasoning the implications of the findings by reflecting on the relationship between the components as part of a delivery chain and their insinuations for planning practice. This was an iterative process which moved continually between the layers to refine our work. The strategy was pursued so that we could translate practical experience into illuminating insights through the rigors of a heuristic framework.

Primary synthesis findings – key themes

Most respondents were unsurprised s106 contributions towards transport infrastructure had declined due to many local authorities adopting CIL; ‘the point of CIL was broadly, it was intended to replace a load of s106 stuff’ (Officer C, 2022). The extent of the decline did however surprise several respondents for transport persisted as a site specific accessibility issue that CIL did not resolve; ‘out of all the aspects that you would expect CIL to have an impact on reducing s106, transport was probably one of the least because you generally do have this demonstrative site specific impact activity’ (Officer Z, 2022). Several explanations were offered, and a thematic overview of them is now presented.

Planning Reform

Central government has conducted several rounds of reforms to England’s planning system since 2010 with the intention of making the system faster and more responsive, although these efforts frequently seem counterproductive (Raynsford, Citation2018). In terms of LVC, central government imposed numerous restrictions which made s106 unwieldy in the hope of forcing local authorities to adopt CIL. These changes included limits to pooling contributions (removed 2019), prohibiting their use on smaller developments and strengthening the tests of necessity through regulation (DCLG (Department of Communities and Local Government), Citation2012; Lord et al., Citation2020). Most respondents felt these changes hampered their efforts; ‘there’s been a lot of reform of the planning system which has made it harder to get contributions from developers’ (Officer M, 2022).

Tougher tests of necessity increased the emphasis on adopting planning policies and frameworks to justify contributions; ‘ … the easiest way to show a contribution is necessary is to point to a planning policy that says the air quality of this area is very bad and needs to be improved’ (Planner F, 2022). This was a particularly important consideration for transport; ‘for traffic and transport projects, it’s much harder to show that you should be investing in something that’s happening a mile away’ (Officer X, 2022). Many places however lacked such strategy due to budget and resource constraints;

‘it was quite difficult for that authority to capture that funding because it couldn’t demonstrate it had a number of infrastructure projects on a schedule … to get an infrastructure program and to cost that; it’s quite expensive to do for a local authority and often they don’t have the resources’ (Officer X, 2022).

Market conditions

All respondents suggested property market inequalities partly explained declines in s106 contributions for transport. London properties are typically more expensive, resulting in developers financing substantially more contributions here than elsewhere; ‘viability is a fundamental issue because outside London a lot of developers find viability is quite marginal, and therefore they’ve got less scope to provide financial contributions’ (Officer M, 2022). Some of the reduction in s106 contributions for transport could be due to CIL being adopted in London; for example, developer funding for Crossrail has increasingly come via the mayoral CIL rather than s106 (GLA, Citation2016). The prominence of London within the overall developer contributions figures meant changes here can distort the overall picture of decline across England.

Outside London, officers reported weak property markets limited viability and restricted what might be captured to fund transport infrastructure. This resulted in officers and local authorities prioritising and selecting what infrastructure could be funded; ‘generally s106 can be restricted by viability arguments … we have had to make difficult choices about which infrastructure will be afforded and, which couldn’t’ (Officer O, 2022). Affordable housing provision was raised as an important priority by most respondents due to its prominence in central government policy and targets, and these contributions have increased significantly from £2.3bn in 2011/12 to £4.6bn in 2018/19 (Lord et al., Citation2020). Transport has not been subjected to this level of concern and may diminish in any trade-off; ‘it’s always a conflict with affordable housing and infrastructure … it’s very hard to get both’ (Officer S, 2022).

Developer preferences

Respondents reported that developers were keen to contribute to transport infrastructure in some areas because they saw added value and profitability from improved accessibility; ‘a lot of developers are seeing the business case for sustainable travel to and from their sites’ (Officer U, 2022). However, some felt this interest was fickle and largely limited to what developers thought local markets demanded; ‘public transports a lot higher priority there [London] in awareness terms; other cities are still quite car orientated in their mindset from a general public perspective’ (Officer M, 2022). Likewise, there was a general feeling developers were more willing to contribute to transport (and other infrastructure) where property was built for investment and value needed to be maintained over a longer term; ‘there are some developers who are building out big sites and want to maintain interests for many decades in that site, and they’ll have a very different priority for investment from those who might want to sell it on immediately’ (Officer U, 2022). Some officers tried to influence developer preferences by preaching the benefits and framing contributions as an investment rather than a tax; ‘on sustainable transport I think you can get very good value for money, so the cost of a footpath or cycle path improvement is far cheaper than building a new road… it’s one of the best bang for your buck items that you can get … It can often help unlock a difficult discussion about whether a development should be permitted’ (Officer O, 2022).

Several respondents suggested developers sometimes used financial viability concerns to plead hardship and be absolved of requirements to contribute; ‘Viability, of course, something they sometimes raise, and we are required to let them off the hook basically. As otherwise the scheme would be unviable if we charged for contributions’ (Officer F, 2022). Although some planners felt developers did occasionally try overstating their financial viability concerns by creative accounting or challenging evidence to exploit the situation and reduce their obligations, this proved less of an issue with transport infrastructure; ‘it’s a developer, he/she is trying to reduce the liability per house he/she has to pay. But its … I’ve never really seen transport contributions as one that’s so flagged as “do we have to pay?”’ (Officer Z, 2022). This was primarily due to the obvious need for accessibility; ‘If you can’t get in or out, it’s gonna strangle their sales!’ (Officer K, 2022). That said, others felt there were issues when negotiate settlements for strategic (and more expensive) measures; ‘They [developers] tend to argue more about the larger scale transport interventions and whether they’re necessary. I would say sometimes with justification because … most authorities will try and get what they can from a development and sometimes we are asking a lot’ (Officer O, 2022).

Fragmentation

Splitting land use and transport functions into different departments (and sometimes into separate local authorities in differing tiers) was also said to hamper the harvesting of contributions for transport, with officers often reliant on partners; ‘in our case transport is very much driven by the county council and we are beholden to them. It is up to them to decide what projects need funding. It is a bit out of our hands.’ (Officer F, 2022). Some respondents suggested these junctures sometimes caused officers to be unrealistic about what might practically be achieved and to have difficulty communicating; ‘you have some people who are very technical from the transport side who might not know the best ways to make the business case or might ask for something that matters on their side but then doesn’t translate very well’ (Officer U, 2022). Likewise, others encountered problems when moving out of partners comfort zones; ‘ … their [district] planning departments are capable of dealing with three storey rear and side extensions to houses… But when you throw anything bigger than that at them, it’s completely out of their ability’ (Officer S, 2022).

Selecting priorities seemed an important recuring issue with departments sometimes having conflicting agendas, or ones which were out of synch. Examples include erstwhile partners opting not to pursue requests to negotiate transport contributions from developers due to differences in priority; ‘you might have all the schemes in the world but if a planning authority … doesn’t want to support you in your request … then you won’t get all of that. You’ll be lucky to get your school stuff. You probably won’t get any community facilities and you definitely won’t get any transport’ (Officer S, 2022). In other cases, planners struggled to bridge funding gaps where developers only contributed to part of the transport infrastructure costs as the proposals did not register as a priority to others; ‘you can quite often get funding for half a pedestrian crossing or half a signalized junction. Which means that the Council has got to find the other half. And if it’s not in a major priority area and funding is being diverted to other things at that moment in time, it can be quite possible for s106 moneys … to hang around for ages’ (Officer C, 2022). To these ends some explained they were negotiating just as much with their own colleagues as with developers; ‘development management planners have the quite difficult job of balancing the asks of all the departments in the Council … In as much as anything, the negotiation could be in house rather than rather than with the developer’ (Officer C, 2022). Several respondents hoped the re-emergence of strategic planning in city regions through devolution deals would eventually prevent these conflicts by providing new levels of oversight and means of resolution; ‘it should get to be a more harmonious model as it evolves over time, and it means we can inch our way towards doing it in a more coherent fashion’ (Officer M, 2022).

Behaviour

Most respondents suggested their local authority influenced their behaviour through leadership and the setting of priorities. This cut both ways, with those areas setting transport as a priority seemingly actively encouraging and supporting their officers’ attempts to get contributions; ‘I don’t think it’s skill in terms of a technical level. I think it’s that strategic driver from the top level that gives the officers that support to go and secure these things’ (Officer Z, 2022). On the other hand, local authorities which did not see sustainable transport as a priority were sometimes obstructive and even discouraged officers; ‘if you’re in an authority … where local politically you’re not really confident you’re going to get the backing of it. Will that officer be confident in going to that planning committee and saying I want the developments to pay XY&Z? Probably not’ (Officer Z, 2022).

Some officers suggested the types of transport infrastructure being requested may have inadvertently diminished s106 contributions. For example, since 2010 planners have increasingly sought contributions for electrical vehicle charging points and some found this could be achieved more practicably using planning conditions; ‘requiring electric vehicle charging points, there is just no need to use a s106 because it can be conditioned’ (Officer F, 2022). Likewise, several planners highlighted how green transport plans are still a key transport concession levied on developers using planning conditions.

Almost all officers suggested developer contributions by themselves were insufficient to deliver transformative transport infrastructure; ‘You couldn’t extend it [the metro system] without it being a nine-figure sum of some description, which s106 just wouldn’t touch the sides of!’ (Officer B, 2022). These difficulties also discouraged officers from trying to obtain contributions; ‘It’s no use if you just collect money towards a scheme and you’ve got no confirmation of building it because you’ll find you’ve got a time limit on that money and you’ll just end up paying it back to the developer’ (Officer S, 2022).

The importance of transport also made some officers reluctant to use s106 powers, preferring instead to seek other funding (like central government grants) to provide new transport infrastructure which opened sites to development; ‘Infrastructure should always come first, and that’s what we’re doing … looking to intervene and help with the infrastructure; to put the roads in first to get the links in first’ (Officer K, 2022). In these cases, planners sought subsequent contributions for affordable housing, education or green spaces from developers, which might not otherwise have been viable had transport been included too; ‘sometime, you’ve got to lead with that; put the money in first and then try and get the money back’ (Officer Z, 2022).

Given the numerous practical issues encountered in successfully negotiating s106 contributions for transport measures, several respondents intimated this was something learned tacitly through experience; ‘You can always improve in negotiation skills and a lot of it is based on experience because until you get in the room you never really know how hard it can be’ (Officer U, 2022). Likewise, officers were felt to lose out on crucial practical insights in places where s106 was not used regularly, which perhaps put them at a disadvantage when an agreement was required; ‘in other authorities, perhaps s106 agreements are not so usual. So you perhaps don’t have that experience’ (Officer X, 2002). Some respondents feared this reliance on practical knowledge was inherently fickle due to extensive turnover of personnel in the planning system; ‘if you’re talking about a hindrance, the fact that there is a very high turnover of the officers involved from transport side in negotiating s106 and in sustainable transport generally. We have real recruitment and retention problems due to the private sector paying more at the moment… people quite often only stay six months’ (Officer O, 2022).

These resource pressures also meant officers and their managers increasingly needed to consider how much effort was required to secure s106 contributions, and whether these benefits were a good use of resources; ‘there is huge pressure given the number of applications we have to deal with and the number of officers we have to deal with them’ (Officer X, 2022). This seemed a particular issue with transport, for the resulting benefits might be neglected as they related to partners interests; ‘there was a perception from members [councillors] that we were raising money to go and hand it over to the county council and why are we doing that? We shouldn’t!’ (Officer Z, 2022). Likewise, others expressed concerns over the time needed to negotiate s106 when central government reforms wanted the planning system speeded up; ‘local authorities are less willing to ask for them [contributions] as well because of the speed up being the priority’ (Officer M, 2022).

This myriad of influences on planners’ behaviour meant frequent differences in how planners set about extracting developer contributions for transport, even within the same local authority; ‘Well, it should be standardised as we have policies, and they should be applied uniformly. But we are overall human so there might be instances of sometimes missing something. Certainly where viability is an issue. That is quite subjective’ (Officer F, 2022). These issues clearly vexed and frustrated respondents; several felt unable to fully utilise s106 due to a combination of internal politics determining priorities, market forces and cumbersome regulations which were all largely beyond their control and had to be resolved before trying to negotiate with developers; ‘When government writes the policies about viability and we should all be getting 50% affordable housing and million pound tube lines and things that I don’t think they’re really appreciating the situation in a lot of the country, where we’re lucky to be able to get some CIL and a reasonable s106’ (Officer O, 2022). Some respondents looked on London with envy; ‘land value capture, but that actually only works in London. There’s not enough margin elsewhere in the country’ (Officer M, 2022). Although others highlighted London too had many of the same difficulties to a lesser or greater extent; ‘it’s a region, London… So very very small area really, but with huge demand for building. So land value is huge there. But in the outer London boroughs as you head towards the M25 it’s a completely different story’ (Officer X, 2022).

2nd layer synthesis – applying the D=CIB framework

Translating our findings into the D=CIB framework, we suggest s106 contributions for transport have decreased due to a complex web of interrelated factors that are inherently contextual in nature. In particular, officers find themselves subjected to top-down regulatory frameworks from central government and working to priorities set within local authority structures at a strategic level to the extent they are hemmed in with crisscrossing red lines. Likewise, they are faced with a delivery landscape shaped by market forces, and which seems frequently loaded against use of s106. Since 2010, many of these factors have been exacerbated through continuous rounds of planning reform.

These contextual factors influence behaviours as officers rarely appear in full command of their situation. The multitude of contextual factors can manifest as planning cultures which assist or limit the actions that might be taken due to prevailing attitudes within a local authority towards sustainable transport and economic development. Officers experience in navigating these challenges seems key, for they rarely have a free hand to negotiate with developers for transport infrastructure, much to their frustration and vexation. Yet this is also somewhat fickle, varying between individuals while knowledge is lost through officer turnover.

Intelligence appears to provide some opportunity for resolving these issues through constructive dialogue, appreciation and understanding. These efforts are as much needed against players on officers’ own side (as against the opponent developer) due to the fragmented land use and transport policy landscape. Likewise, developers can weaponize intelligence to negotiate contributions downwards by questioning the need for measures or pleading financial unviability.

In terms of linkages between these elements, we suggest a critical juncture persists between context and behaviour, that is, how planning actors respond to their situation. The linkage here can be characterised as problematic and weak, for contextual pressures push against what actors feel able and happy to do to the extent that contributions are not always successfully negotiated when they might have been.

3rd layer synthesis – implications

Our findings suggest there is some variation in the actions officers take towards s106 to the extent it is not applied systematically or uniformly. While officers are expected to have some volition to interpret policies and regulations in a discretionary planning system, experience with s106 and transport exceeds what elasticity might reasonably be construed. This is an important issue on several fronts.

Firstly, the public are deprived of funding for infrastructure which might alleviate external costs of development, such as improvements to sustainable transport accessibility. Without contributions, these costs fall on the public purse, potentially at the expense of other infrastructure investments and/or in overloaded public services.

Secondly, this lack of consistency causes regional inequality to fester as areas experiencing a virtuous circle receive increased infrastructure spending, while those locked into a vicious circle due to challenges of financial viability continue to stagnate and lag economically. There is some debate (beyond the remit of this paper) on whether s106 is the best means of investing in infrastructure in comparison to CIL or other forms of taxation.

Thirdly, variations in using s106 offers fertile grounds for developers to play games with officers to reduce contributions downwards. For example, a developer could threaten to take their investment elsewhere if not offered some discount, exemption, or inducement. The extent to which officers and local authorities are equipped to play these games is debateable, for while some are clearly experienced and resourced for these fights, others are not.

And finally, the lack of consistency makes it difficult for communities to understand decision-making processes and induces a sense that planning consent is bought and sold. Ultimately, this erodes public trust in the planning system, its officers and institutions.

Discussion and conclusion

S106 contributions towards transport infrastructure have declined for various reasons, with reforms to planning and prioritisation of local authority objectives manifesting in planning cultures which have ultimately reduced what can be leveraged. The fragmented and disjointed policy landscape in English local government further complicates matters by requiring integration between partners which place additional challenges on planners beyond negotiating with developers.

Previous research on integrated land use and transport policies, plans and programmes highlight how these processes often prove fraught and flounder against procedural, administrative and sectoral barriers (Fischer et al., Citation2013; Smith, Citation2014), and our findings reinforce these messages that this integration remains challenging in England. There is additionally strong consistency between our results and those of Smith (Citation2021) which examined the period immediately before 2010 during the spatial turn of planning and found thinking to be siloed and officers handicapped by conflicting priorities and sent into battle with tools unfit for purpose. Our findings could imply planners have failed to heed these lessons yet this is disingenuous as officers lack the means to make the necessary changes themselves due the persistence of various cultural and structural constraints which set priorities and expectations, as was also observed by Buck (Citation2021) and Dunning et al. (Citation2019). While past research demonstrates s106 and LVC to be challenging enough endeavours themselves (Crook & Whitehead, Citation2019; Lord et al., Citation2019), our results suggest the intrinsic integration difficulties with transport make these tasks more problematic and should not be underestimated.

Our work suggests LVC practices are inherently systemic and institutional, needing to be seen in the context of the entire approach to planning. To this extent, our D=CIB framework is particularly effective at placing an intervention into its wider setting to illuminate murky practice issues concerning what works. It is particularly useful at structuring research on planning practice by reflecting on the complex interplay between different components involved in the delivery of planning. Yes, context is always important, but so are flows of information and attributes of planning practitioners to researchers seeking to understand planning practices. This is perhaps most evident in how the same policy instruments can result in different outcomes from a function of individual experience as much as context. In this regard, we feel planners would find it insightful to know how much value is available for capture so that appropriate and consistent responses can develop.

LVC offers a solution to the perennial challenges planners face in delivering the infrastructure needed to meet the global climate emergency whilst public finances are increasingly strained (Dunning & Lord, Citation2020). That LVC covers a broad range of mechanisms individually tailored to individual countries requires researchers develop a nuanced understanding of planning practice, institutional context and governance elements involved. While negotiated settlements are generally specific to discretionary planning systems, those with regulatory and hybrid models can also look towards negotiation as a means for leveraging further contributions. For example, negotiation is still needed in public-private partnerships or in processes of expropriation, as experienced in Holland (Samsura et al., Citation2015). That all forms of LVC need to be accepted and legitimised by the public and developers likewise places additional focus on negotiation between stakeholders (OECD, Citation2022). This can be witnessed in the setting of acceptable thresholds and procedures in tax based LVC approaches. These experiences suggest negotiation in some form is intrinsic to all formats of LVC, and integration between land use and transport planning functions (which can be problematic in itself) is central to this wider conversation.

Going forward, we suggest more research (both domestically and internationally) is needed for scholars to fully appreciate what works, when and why with regard to LVC if we are to learn from the growing experience of harvesting planning gains to pay for public goods. While contextual, cultural and personal attributes involved in the development and practice of LVC make it impossible to transplant procedures and lessons between counties, one can extrapolate insights based on fathoming what works (and equally does not), how and why, and our D=CIB framework, constructed around the underlying relationship of the factors involved, is particularly useful at structuring our responses.

Acknowledgments

The author is grateful to all the interview participants and Prof Alex Lord and Dr Richard Dunning (Liverpool University) for their advice in producing this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Baker, M., & Hincks. S. (2009) Infrastructure delivery and spatial planning, Town planning review, 80(2), pp. 173–199.

- Banister, D. (2001) Transport Planning, 2nd ed. (London: SPON).

- Banister, D. (2005) Unsustainable Transport. (London: Routledge).

- Booth, P. (2012) The unearned increment: Property and the capture of betterment value in Britain and France, In: G. K. Ingram & Y.-H. Hong (Eds) Value Capture and Land Policies, pp. 74–93 (Cambridge: Lincoln Institute for Land Policy).

- Buck, M. (2021) Considering the role of negotiated developer contributions in financing ecological mitigation and protection programs in England: A cultural perspective, Local Economy, 36(5), pp. 356–373. doi:10.1177/02690942211053592.

- Burgess, G., & Monk, S. (2016) Chapter 8 Delivering planning obligations – are agreements successfully delivered?, In: A. D. H. Crook, J. Henneberry, & C. Whitehead (Eds) Planning Gain, pp. 201–226 (Chichester: Wiley Blackwell).

- Cairney, P. (2022) The myth of ‘evidence-based policymaking’ in a decentred state, Public Policy and Administration, 37(1), pp. 46–66. doi:10.1177/0952076720905016.

- CIHT (Charted Institution of Highways and Transportation) (2019) Better Planning, Better Transport, Better Places (London: CIHT).

- Clifford, B., & Tewdwr-Jones, M. (2014) The Collaborating Planner? Practitioners in the Neoliberal Age. (Bristol: Policy Press).

- Crook, A. D. H. (2016) Chapter 4 Planning obligations policy in England: undefined facto taxation of development value, In: A. D. H. Crook, J. Henneberry, & C. Whitehead (Eds) Planning Gain, pp. 63–114 (Chichester: Wiley Blackwell).

- Crook, A. D. H., Henneberry, J., & Whitehead, C. (2016) Summary and conclusions, In: A. Crook, J. Henneberry, & C. Whitehead (Eds) Planning Gain, pp. 269–290 (Chichester: Wiley Blackwell).

- Crook, A. D. H., Henneberry, J., & Whitehead, C. (2021) Funding affordable homes and new infrastructure – improving Section 106 or moving to an infrastructure levy?, Town & Country Planning, 90(3/4), pp. 88–94.

- Crook, A. D. H., & Whitehead, C. (2019) Capturing development value, principles and practice: Why is it so difficult?, The Town Planning Review, 90(4), pp. 359–381. doi:10.3828/tpr.2019.25.

- Cullingworth, B., & Nadin, V. (2006) Town and Country Planning in the UK, 14th ed. (London: Routledge).

- Davoudi, S. (2006) Evidence-based planning; rhetoric and reality, disP, 165(42), pp. 14–24. doi:10.1080/02513625.2006.10556951.

- DCLG (Department of Communities and Local Government) 2012 National Planning Policy Framework (London: DCLG).

- DoE (Department of the Environment) 1995 The Use of Conditions in Planning Permissions, Circular 11/95 (London: DoE).

- Dunning, R., & Lord, A. (2020) Viewpoint: Preparing for the climate crisis: What role should land value capture play?, Land Use Policy, 99(99), p. 104867. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2020.104867.

- Dunning, R., Lord, A., Keskin, B., & Buck, M. (2019) Is there a relationship between planning culture and the value of planning gain? Evidence from England, The Town Planning Review, 90(4), pp. 453–471. doi:10.3828/tpr.2019.29.

- Enoch, M., Potter, S., Ison, S., & Humphreys, I. (2004) Role of hypothecation in financing transit, lessons from the United Kingdom, Journal of the Transportation Research Board, 1864(1), pp. 31–37. doi: 10.3141/1864-05.

- Ferreira, A. (2013) Emotions in planning practice: A critical review and a suggestion for future developments based on mindfulness, The Town Planning Review, 84(6), pp. 703–719. doi:10.3828/tpr.2013.37.

- Fischer, T., Smith, M., & Sykes, O. (2013) Can less sometimes be more? – Integrating land use and transport planning on Merseyside (1965–2008), Urban, Planning and Transport Research, 1(1), pp. 1–27. doi:10.1080/21650020.2013.866876.

- Gallent, N. (2008) Strategic-local tensions and the spatial planning approach in England, Planning Theory & Practice, 9(3), pp. 307–323. doi:10.1080/14649350802277795.

- GLA (Greater London Authority) 2016 Crossrail Funding Supplementary Planning Guidance (London: GLA)).

- Glaister, S., Burnham, J., Stevens, H., & Travers, T. (2006) Transport Policy in Britain, 2nd ed. (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan)).

- Gozalvo Zamorano, M. J., & Muñoz Gielen, D. (2017) Non-negotiable developer obligations in the Spanish land readjustment: An effective passive governance approach that ‘de facto’ taxes development value?, Planning Practice & Research, 32(3), pp. 274–296.

- Headicar, P. (2009) Transport Policy and Planning in Great Britain. (Abingdon: Routledge)).

- Hillier, J. (2011) Strategic navigation across multiple planes. Towards a Deleuzean-inspired methodology for strategic spatial planning, The Town Planning Review, 82(5), pp. 503–527. doi:10.3828/tpr.2011.30.

- Holt, V., & Baker, M. (2014) All hands to the pump? Collaborative capability in local infrastructure planning in the North West of England, The Town Planning Review, 85(6), pp. 753–772. doi:10.3828/tpr.2014.45.

- Lane, R., & Wells, J. (2006) Using planning agreements to fund transport infrastructure, Municipal Engineer, 159: pp. 77–83. doi: 10.1680/muen.2006.159.2.77.

- Lindblom, C. E. (1959) The science of ‘muddling through’, Public Administration Review, 19(2), pp. 79–88. doi:10.2307/973677.

- Lord, A. (2012) The Planning Game; an Information Economics Approach to Understanding Urban and Environmental Management. (Abingdon: Routledge)).

- Lord, A., Burgess, G., Gu, Y., & Dunning, R. (2019) Virtuous or vicious circles? Exploring the behavioural connections between developer contributions and path dependence: Evidence from England, Geoforum, 106: pp. 244–252. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2019.07.024.

- Lord, A., Cheang, C.-W., & Dunning, R. (2022) Understanding the geography of affordable housing provided through land value capture: Evidence from England, Urban Studies, 59(6), pp. 1219–1237. doi:10.1177/0042098021998893.

- Lord, A. D., Dunning, R., Buck, M., Cantillon, S., Burgess, G., Crook, T., Watkins, C., & Whitehead, C. (2020) The Incidence, Value and Delivery of Planning Obligations and Community Infrastructure Levy in England in 2018/19. (London: Ministry for Housing Communities and Local Government)).

- Moore, V. (2002) A Practical Approach to Planning Law, 8th ed. (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

- Morphet, J., Tewdwr-Jones, M., Gallent, N., Hall, B., Spry, M., & Howard, R. (2007) Shaping and Delivering Tomorrow’s Places: Effective Practice in Spatial Planning. (London: Royal Town Planning Institute)).

- Noblit, G. W., & Hare, R. D. (1988) Meta-Ethnography; Synthesizing Qualitative Studies. (Newbury Park: Sage)).

- Nutley, S., Walter, I., & Davies, H. T. O. (2003) From knowing to doing; a framework for understanding the evidence-into-practice agenda, Evaluation, 9(2), pp. 125–148. doi:10.1177/1356389003009002002.

- ODPM (Office of the Deputy Prime Minister) 2005 Circular 05/2005 Planning Obligations (London: ODPM).

- OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) 2022 Financing Transportation Infrastructure Through Land Value Capture; concepts, Tools and Case Studies (Paris: OECD)).

- Pressman, J. L., & Wildavsky, A. B. (1973) Implementation: How Great Expectations in Washington are Dashed in Oakland. (Berkeley: University of California Press)).

- Raynsford, N. (2018) Planning 2020, Raynsford Review of Planning in England. (London: Town & Country Planning Association)).

- Rogers, E. M. (2003) Diffusion of Innovations, 5th ed. (New York: Free Press)).

- Rycroft-Malone, J., Harvey, G., Seers, K., Kitson, A., McCormack, B., & Titchen, A. (2004) An exploration of the factors that influence the implementation of evidence into practice, Journal of Clinical Nursing, 13(8), pp. 913–924. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2702.2004.01007.x.

- Rydin, Y., Beauregard, R., Cremaschi, M., & Lieto, L. (2021) Introduction, In: Y. Rydin, R. Beauregard, M. Cremaschi, & L. Lieto (Eds) Regulation and Planning; Practices, Institutions, Agency, pp. 1–11 (London: Routledge)).

- Rye, T., Green, C., Young, E., & Ison, S. (2011) Using the land-use planning process to secure travel plans: An assessment of progress in England to date, Journal of Transport Geography, 19(2), pp. 235–243. doi:10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2010.05.002.

- Samsura, D. A. A., van der Krabben, E., van Deeman, A. M. A., & van der Heijden, R. E. C. M. (2015) Negotiation processes in land and property development: An experimental study, Journal of Property Research, 32(2), pp. 173–191. doi:10.1080/09599916.2015.1009846.

- Smith, M. (2014) Integrating policies, plans and programmes in local government: An exploration from a spatial planning perspective, Local Government Studies, 40(3), pp. 473–493. doi:10.1080/03003930.2013.823407.

- Smith, M. (2018) Revisiting implementation theory; an interdisciplinary comparison between urban planning and healthcare implementation research, Environment & Planning C: Politics and Space, 36(5), pp. 877–896.

- Smith, M. (2021) Delivering the goods: Executing sustainable transport policy through urban planning in Merseyside (2001–2010), Planning Perspectives, 36(3), pp. 515–534. doi:10.1080/02665433.2020.1813620.

- Smith, M., Sykes, O., & Fischer, T. (2014) Derailed: Understanding the implementation failures of Merseytram, The Town Planning Review, 85(2), pp. 237–260. doi:10.3828/tpr.2014.15.

- Snowden, D. J., & Boone, M. E. (2007). A leaders framework for decision making, Harvard Business Review, November, pp. 69–76.

- Solesbury, W. (2002) The ascendancy of evidence, Planning Theory and Practice, 3(1), pp. 90–96. doi:10.1080/14649350220117834.

- Sturzaker, J., & Lord, A. (2018) Fear: An underexplored motivation for planners’ behaviour?, Planning Practice and Research, 33(4), pp. 359–371. doi:10.1080/02697459.2017.1378982.

- Vigar, G. (2002) The Politics of Mobility. (London: SPON)).

- Vigar, G. (2012) Planning and professionalism: Knowledge, judgement and expertise in English planning, Planning Theory and Practice, 11(4), pp. 361–378.

- Wyatt, P. (2017) Experiences of running negotiable and non-negotiable developer contributions side-by-side, Planning Practice and Research, 32(2), pp. 152–170. doi:10.1080/02697459.2016.1222148.