ABSTRACT

Comprehensive understanding of the merits of bottom-up urban development is lacking, thus hampering and complicating associated collaborative processes. Therefore, and given the assumed relevancies, we mapped the social, environmental and economic values generated by bottom-up developments in two Dutch urban areas, using theory-based evaluation principles. These evaluations raised insights into the values, beneficiaries and path dependencies between successive values, confirming the assumed effect of placemaking accelerating further spatial developments. It also revealed broader impacts of bottom-up endeavors, such as influences on local policies and innovations in urban development.

1. Introduction

Within the context of Dutch organic urban development (Rauws & de Roo, Citation2016; Buitelaar et al., Citation2017; Dembski, Citation2020), non-conventional local actors have pursued bottom-up initiatives, aiming to fulfill needs that are not sufficiently met by state or market, such as providing workplaces for creatives or promoting sustainable building by conducting circular economy experiments (Mens et al., Citation2021). These initiatives relate to other contemporary phenomena and concepts, such as do-it-yourself urbanism (Iveson, Citation2013; Finn, Citation2014), temporary use (Colomb, Citation2012; Martin et al., Citation2019; Matoga, Citation2019) and self-organization (Boonstra & Boelens, Citation2011; Horelli et al., Citation2015; Partanen, Citation2015). Whereas the current formal urban planning system favors a predominant economic value perspective (Adams & Tiesdell, Citation2010), these informal, bottom-up initiatives focus on realizing values that are not paramount in that formal perspective. Some have been encouraged by both state and market actors as part of recent organic development strategies, particularly when more conventional development approaches were less opportune (i.e. from an economic value perspective). As such, they relate to the formal system to some extent. Moreover, they align with state policies aiming to stimulate a self-reliant and participatory society (Boonstra, Citation2015).

We perceive these bottom-up urban developments as a specific type of citizens’ initiatives, in which the initiators are, aside from citizens, also independent professionals, i.e. they find their origin at the interface of society and market and reach goals by means of social entrepreneurship (Weerawardena & Mort, Citation2006; Certo & Miller, Citation2008), as argued by Mens et al. (Citation2021). We advocate the relevance of such bottom-up development initiatives for urban innovation and healthy, vibrant cities following other related, scholarly work (e.g. Partanen, Citation2015; Rabbiosi, Citation2016; Danenberg & Haas, Citation2019). In the Dutch context, we have observed bottom-up initiatives being appreciated and praised in public debates as such, but also note that precise and detailed intelligence on the outcomes of such endeavors, are scarce.

Although other scholarly work deliberates on various aspects of bottom-up urban initiatives (e.g. Papachristou & Rosas-Casals, Citation2015; Rabbiosi, Citation2016; Mens et al., Citation2021; Pradel-Miquel, Citation2021; von Schönfeld & Tan, Citation2021), an in-depth study on the merits of bottom-up initiatives in urban development is lacking. We refer to Igalla et al. (Citation2019) who addressed the potential outcomes of the broader phenomenon of citizens’ initiatives by means of an extensive, global literature review. Although they have identified a number of achievements, these remain fairly general, therefore concluding that ‘our knowledge of the actual outcomes of citizen initiatives is still limited’ (Igalla et al., Citation2019, p. 1189). Reverting to the specific phenomenon of Dutch bottom-up urban development, we observed that such a lack of knowledge creates an atmosphere in which some state and market actors openly question the raison d’être or legitimacy of bottom-up initiatives. Since initiators of bottom-up endeavors strongly depend on collaborations with such actors, hesitance concerning this legitimacy hampers and complicates collaborative processes towards results. We address this problem by questioning which precise values bottom-up urban developments bring forth. The aim is to better recognize and acknowledge anticipated results and effects of bottom-up endeavors, thus supporting collaborative processes and improving public debate.

The issue addressed above finds its origin in the motives of initiators of bottom-up urban development, and the context in which they operate. As already addressed above, Mens et al. (Citation2021) identify the pioneers in bottom-up urban development as social entrepreneurs (Thompson, Citation2002; Weerawardena & Mort, Citation2006; Certo & Miller, Citation2008), who act upon opportunities and are motivated by creating social values (Young, Citation2006; Mulgan, Citation2010). They are not primarily driven by financial returns but must maintain themselves in a competitive, neoliberal context, which is complicated since the values they primarily aim to create, are much harder to grasp or quantify, than the financial values that are a primary indicator of performance in a market-driven context (Austin et al., Citation2012), i.e. social entrepreneurs experience difficulties in legitimizing their efforts within a market-oriented setting, since they do not focus on the financial returns of their efforts.

In this article, we aim to explore and understand the versatile values that successful bottom-up urban developments bring forth, in the context of the revitalization of former inner-city industrial areas. How, or with which values, do bottom-up efforts contribute to change? What role do they fulfill in the transformation of areas? What are possible, broader relevancies for cities and their inhabitants? These questions are of relevance to practitioners, such as initiators seeking support or municipalities considering supporting or stimulating bottom-up endeavors. The scientific relevance lies in a more profound understanding of the values generated by bottom-up urban development, thus filling the above-described gap in knowledge.

2. Evaluating value: composing an analytical model for value mapping

We approach our study of the merits of bottom-up urban development from the concept of value. Basic, philosophical approaches to value are found in the discipline of axiology, or theory of value (Hart, Citation1971; Biedenbach & Jacobsson, Citation2016). In his work on axiology, Hart (Citation1971), for example, describes how value relates to everyday human needs and desires and permeates our lives as such. It affects our behaviors, decisions, actions and well-being among others. Of relevance are Hart’s remarks on the relationship between value and interest. An interest of a person or group of persons in something is a condition for it to acquire value (Hart, Citation1971). We also address the overlap between the values we aim to scrutinize, and the goals of those involved. However, we purposefully choose to focus on values instead of goals because we aim for a broad inventory of all intended, unintended, positive and negative results and effects, instead of only those purposefully intended by specific actors (i.e. their goals).

Previously, we addressed the predominant economic value perspective of the formal planning system. From this perspective, and in a narrow sense, value can be defined as ‘benefits relative to costs’ (Porter & Kramer, Citation2019, p. 327), which is a common perception in business. However, we also introduced our view on bottom-up urban developments prioritizing social values over economic values. Therefore, we need to approach value from a broader perspective. Aside from our monetary system that handles the exchange of financial values specifically, value in general is always the result of an interplay between supply and demand, in which it is crucial who values what (Mulgan, Citation2010). As such, value is not an objective given (Young, Citation2006; Mulgan, Citation2010). Young (Citation2006) speaks of value as ‘a matter of real-life experiences’. She describes social value as that which ‘benefits people whose urgent and reasonable needs are not being met by other means’ (Young, Citation2006, p. 56) and notes that ‘social value is negotiated between stakeholders’ (Young, Citation2006, p. 57). Similarly, Carmona et al. (Citation2002) speak of value as ‘a relational concept, defined through the forms of value sought by competing stakeholders and by the process of interaction between them’ (Carmona et al., Citation2002, p. 149). Given our initial observations, we argue that the values generated by bottom-up urban developments are both diverse and accrue to various people. Therefore, we turn to the concept of shared value (Porter & Kramer, Citation2011). Maas and Grieco (Citation2017) explain shared value by stating that all organizations, either for-profit or not ‘create value that consist of economic, social and environmental value components’ (Maas & Grieco, Citation2017, p. 113). Since this trichotomy of values is widely used and accepted, we adopt it for the purpose of our study, i.e. we will incorporate all three value components in our analyses.

Despite the above contemplations on the relativity and subjectivity of values, recent decades have shown an upsurge of methods to obtain detailed and sometimes quantitative insights in various values, i.e. other than financial ones (Young, Citation2006; Ormiston & Seymour, Citation2011). These methods are contested though. Mulgan et al. (Citation2019) stress ‘the need to move beyond single measures of value and to see the exploration of value more as a process of uncovering that can then support better conversations and negotiations’ (Mulgan et al., Citation2019, p. 40). This is in line with our objectives, which imply a holistic and qualitative approach of value; we aim to gain explorative insights into the values established by bottom-up urban activity. To gain such insights, we turn to the concept of theory-based-evaluation (Weiss, Citation1995, Citation1997; Mayne, Citation2015), which Weiss describes as an alternative to standard evaluation practices and for the use of evaluating complex, comprehensive community initiatives in particular. Weiss: ‘in lieu of standard evaluation methods, I advance the idea of basing evaluation on the theories of change that underlie the initiatives’ (Weiss, Citation1995, p. 66). In other words, she proposes to make the theory that underlies the creation of value explicit: ‘the evaluation should surface those theories (…) identifying all the assumptions and sub-assumptions built into the program. The evaluators then construct methods for data collection and analysis to track the unfolding of the assumptions’ (Weiss, Citation1995, p. 67). Weiss speaks of identifying mini-steps to surface and test the often-unspoken assumptions and speaks of immediate, intermediate and ultimate objectives/effects (Weiss, Citation1997). She also refers to linkages between earlier results and longer-term outcomes using the term causal chains (Weiss, Citation1995). Other scholars use the terms outputs, outcomes and impact to indicate successive effects of interventions over time (Clark et al., Citation2004; Liket et al., Citation2014; Maas & Grieco, Citation2017). They mostly speak of an ‘impact value chain’ to indicate causal relationships between inputs, activities, outputs, outcomes and impacts. In general, outputs are regarded as immediate results of an intervention, outcomes as intermediate effects and impacts as long-term effects or sustained significant change, although definitions and interpretations vary. Mayne (Citation2015) speaks of ‘impact pathways’ to ‘describe causal pathways showing the linkages between the sequence of steps in getting from activities to impact’ (Mayne, Citation2015, p. 121).

We adopt the aforementioned principles of theory-based evaluation by structuring values over time in terms of outputs, outcomes and impacts and also aim to gain insights into casualties in terms of impact pathways. We refer to the work of Macmillan (Citation2006) that brings forward the notion of so-called value maps to structure the exploration of values. These value maps are ‘visual diagrams that set out in graphic form the relationships between different types of value and the flows of value they achieve’ (Macmillan, Citation2006, p. 265). Given its relevance, we will use this concept of value maps for our analyses.

shows the analytical framework we developed, based on the combination of theories and concepts discussed above. This matrix expresses the aim to make a detailed inventory of the outputs, outcomes and impacts of bottom-up initiatives, in terms of economic, social and environmental values including, e.g. the beneficiary or beneficiaries of each value, given the relevance of knowing ‘who values what?’. Related to these beneficiaries, we will distinguish private values from public values, in which private values are those that accrue to individuals or specific groups of people, and public values potentially accrue to all society or public bodies, such as municipalities. We note that the latest developments in evaluation methods focus on complex actor networks instead of linear, causal chains in terms of outputs, outcomes and impacts as presented in . Our focus, however, is on the results and effects of bottom-up initiatives and how they relate, rather than the complex network realities from which they arise. We argue that this goal is best served by the (linear) approach as presented, instead of focusing on the complex network structures that underlie these results.

3. Theoretical assumptions: towards a hypothetical impact pathway

Theory-based evaluation is grounded in the idea that, to make solid evaluations, implicit theoretical assumptions underlying developments are made explicit, i.e. what theory-of-change is consciously or unconsciously assumed? This section articulates the main theoretical assumptions that underlie our evaluations and their interrelatedness.

In the introduction, we refer to the view on initiators of bottom-up urban developments as being social entrepreneurs (Mens et al., Citation2021). Mens et al. (Citation2021) also identified that such initiators often have a background in the creative industry, just as most end-users of the initiatives. The outputs of bottom-up initiatives therefore focus on (social) values related to the needs, desires and beliefs of these creatives. That is, we foresee an initial emphasis on social values that accrue to creatives, combined with, e.g. socio-environmental values arising from environmental engagement. A first, assumed output as such is the provision of affordable, inner-city working places for creatives.

Elaborating on this prominent role of creatives in bottom-up endeavors, we refer to assumed relationships between creative industries, innovation, growth of local economies and urban (re)development. Attention to these relationships has risen since Florida’s well-known work on the rise of the creative class (Florida, Citation2002). Many scholars thereafter have studied and debated relationships between settlements of creatives and urban regeneration in particular (Jarvis et al., Citation2009; Flew, Citation2013; Gregory, Citation2016). In line with these studies, we assume that successful bottom-up development initiatives by creatives influence and stimulate the redevelopment of dilapidated areas; we position placemaking as a central mechanism therein. Relationships between creatives and placemaking are explicated by scholars, such as Gregory (Citation2016), Toolis (Citation2017) and Courage (Citation2017). Toolis (Citation2017) in this regard speaks of a ‘role of arts and culture in rejuvenating the physical, social and economic dimensions of urban life in the midst of post-deindustrialization and suburbanization’ (Toolis, Citation2017, p. 186). The term creative placemaking is often used as such (Markusen & Gadwa, Citation2010; Courage & McKeown, Citation2019). A hint of why there is a strong relationship between creatives and placemaking was provided by He and Gebhardt (Citation2014). They speak of creative workers as being ‘freelance’ and ‘footloose’ and, moreover, having a ‘fluid boundary between work-time and playtime’ (He & Gebhardt, Citation2014, p. 2352). They state that ‘the processes of production and consumption in the creative economy are combined in the same location and perhaps at the same time’ (He & Gebhardt, Citation2014, p. 2352).

Recent studies emphasize the many meanings and uses of placemaking (Palermo & Ponzini, Citation2015; Strydom et al., Citation2018; Courage et al., Citation2020). Toolis (Citation2017) refers to Markusen and Gadwa (Citation2010) in defining placemaking as ‘a bottom-up, asset-based, person-centered process that emphasizes collaboration and community participation in order to improve the livability of towns and cities’ (Toolis, Citation2017, pp. 185 & 186). We also refer to Courage (Citation2017), who distinguishes top-down oriented placemaking from bottom-up placemaking. The first refers to sets of tools used by the public sector to strategically re-image public spaces or to the outcomes of strategically planned interventions. The latter, bottom-up placemaking can be seen as a more spontaneous, unplanned, emergent and community-driven activity that changes place-identity (Courage, Citation2017), which applies to the initiatives we aim to scrutinize. Reviewing literature, we identified indicators of placemaking being an increase in activity, interaction, liveliness, vibrancy, social cohesion and social safety in an area, leading to an increased attractiveness, attraction of other and more diverse actors to an area and change in place-identity.

We feel that many urban policy makers consciously or unconsciously anticipate the above-described effects of bottom-up initiatives by creatives. Placemaking is often regarded as a temporary incentive preceding, and enabling further, more permanent developments. As such, it benefits local governments or landowners anticipating revitalization of an area, aside from users or inhabitants of an area. Since placemaking is in the interest of, for example, local governments, we qualify it as a value, referring to the relationship between interests and value as discussed in the previous section. An important intended or unintended (side-)effect of bottom-up initiatives and placemaking is that of rising land and real estate prices. This notion, together with the observation that many bottom-up initiatives have a temporary basis, implies possible negative consequences for bottom-up initiatives. That is, market-mechanisms may ‘push’ initiators and end-users (i.e. creatives) out of the area they helped revitalize in the first place and force them to move further to the fringes of a city. For them, such a discontinuance of an initiative and possible displacement is mostly an unintended, negative long-term effect partially or completely nullifying the values that accrued to them. We refer to a specific sub-class or broadening of the ‘classic’ conception of gentrification in this respect by Pratt (Citation2018), related to the displacement of creatives from the inner-city. Pratt speaks of ‘a perfect storm of contradiction’ in this respect, in which creatives are ‘wanted, but then disposed of’ (Pratt, Citation2018, p. 357).

The previously described causalities are summarized in the hypothetical impact pathway of , or as Weiss formulates it: ‘the hypothesized chain of events’ (Weiss, Citation1997, p. 78). This figure functions as a first, theoretical steppingstone to map the exact values and how they interrelate, i.e. this impact pathway is to be validated and further detailed by our data-collection and analyses. We also wish to uncover other possible path dependencies though, in line with Weiss, who remarks that ‘the evaluation could track the unfolding of new assumptions in the crucible of practice.’ (Weiss, Citation1995, p. 84).

4. Research method

Our subject is a complex, contemporary phenomenon, which is why we chose for a multiple case study approach (Yin, Citation2014). The main units of analysis (i.e. cases) are former industrial areas undergoing transformative changes given organic development ambitions, in which bottom-up initiatives have emerged in recent years. We regard these bottom-up initiatives as embedded cases (subcases hereafter) in the former industrial areas. A key selection criterion for these subcases was the pursuit of shared values by these initiatives. We selected two areas in two large, Dutch cities. In Rotterdam, we studied the larger Merwe Vierhavens (M4H) area and the sub-area Vierhavensblok in particular. In Utrecht, we studied the area Werkspoorkwartier (WSK). In each area, we selected three bottom-up initiatives; these six subcases, as such, are described in the next section. We chose two different types of bottom-up initiatives, following the typology drafted by Mens et al. (Citation2021). That is, per area we selected two initiatives that led to physical developments and one initiative that fulfilled a more facilitative and intermediate role in the area development.

Our data collection consisted of document studies and three rounds of semi-structured interviews with various stakeholders, such as the initiators of bottom-up developments, civil servants and others involved, such as private financiers. In addition, we frequented the cases and made observations as such and attended various relevant network meetings. The first two rounds of interviews took place from November 2018 to February 2019 in Utrecht and from November 2019 to March 2020 in Rotterdam; both rounds were preceded by document studies. These two rounds of interviews were part of a broader study towards various aspects of bottom-up urban developments, in which the values created was only one of the multiple topics. The 23 interviews of these two rounds were audio recorded, transcribed and analyzed (i.e. by selective and open coding using ATLAS.ti). Selective coding was among others based on the theoretical assumptions presented in section three. A third round of interviews took place from November 2021 to January 2022, in which we focused particularly on the values of the six selected subcases. Preceding this round of interviews, we analyzed quotes from the first two rounds of interviews related to the created values. Moreover, we conducted a document study on the values of these initiatives using, e.g. municipal policy documents (WSK and M4H) and the M4H program monitors, providing insights into recent changes. These analyses enabled us to draft preliminary value maps and empirical impact pathways. In the third round of interviews, we asked our interviewees to reflect on the various values created by the bottom-up initiatives using . After extensively collecting data as such, we presented our preliminary value maps and impact pathways and asked our interviewees to validate these. As such, the goal of this third round was twofold: to collect specific, additional data and to validate preliminary findings. The eight interviews of the third round were audio recorded. We made reports of these recordings in which key parts were transcribed; these reports were summarized and analyzed. The larger part of the third round of interviews was held online because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

5. Short case explorations

5.1. Case 1: Vierhavensblok in Rotterdam

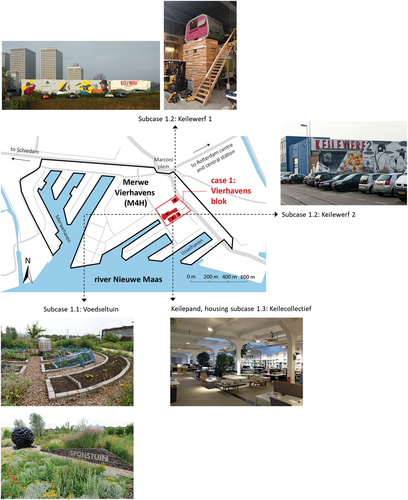

The Rotterdam case, Vierhavensblok, is part of the larger area Merwe Vierhavens (M4H) in the west of Rotterdam (). M4H is currently being redeveloped from an industrial harbor area into a mixed-use area (i.e. working and living) following organic development principles. M4H has been named ‘Rotterdam Makers District’ together with the RDM (Rotterdamse Droogdok Maatschappij) area south of the river Nieuwe Maas, expressing the ambitions of the local authorities regarding the redevelopments. In Vierhavensblok, an emergence of bottom-up activity and activity by creatives took place in recent years. The first bottom-up subcase we selected in this area is De Voedseltuin (Food Garden in English; subcase 1.1). This 7000 m2 large production garden, founded in 2010 on a piece of wasteland, produces fresh vegetables and fruits for the nearby Rotterdam Food Bank, applying permaculture principles. The garden is maintained with the help of a large group of volunteers who mostly struggle with personal issues. Working at De Voedseltuin is a way for them to improve their personal situation. Over the years, De Voedseltuin developed into a multifunctional place where, in addition to being a production garden and volunteer project, visitors can enjoy greenery and, e.g. art installations by a neighboring artist. It has become a publicly accessible park and, moreover, a place where sustainability experiments are conducted, such as the Sponstuin (Sponge Garden in English) in collaboration with a neighboring office for urban design and research. Stam and Peek (Citation2019) summarize the functionalities of De Voedseltuin as a combination of 1) producing, 2) learning and working, 3) staying and meeting and 4) experimenting and innovating.

The second subcase in Vierhavensblok is De Keilewerf (subcase 1.2), which started in 2013/2014 in an empty hall of over 3000 m2, currently known as Keilewerf 1 and expanded in 2016 with Keilewerf 2 (2740 m2) in a nearby building. Both buildings offer affordable workplaces to small, starting entrepreneurs in the creative making industry. Moreover, Keilewerf occasionally organizes festivals and other events. In 2019, Keilewerf celebrated its 5-year existence, then housing 105 creative businesses (van den Berg et al., Citation2019). Located directly at the entrance of Keilewerf 1, the initiators of De Keilewerf erected a warehouse and workshop called ‘Buurman’ offering re-used, recovered building materials and machinery to process these materials, open to the public. Although Buurman is a separate organization from De Keilewerf, we regard both as one subcase in our study.

The third bottom-up subcase in Rotterdam is Het Keilecollectief (subcase 1.3). Het Keilecollectief has been organizing various public activities from roughly 2018 on, such as lectures, debates and expositions among others, linking societal themes such as climate adaptation and circularity to the redevelopment of M4H. The initiative emerged from the users of the Keilepand building (). The new users of this immense, formerly unused warehouse collectively redeveloped this building into a location where various creative companies share spaces and facilities; they bought the building from the municipality in 2019. Het Keilecollectief is run by people from the Keilepand building, using the facilities and spaces of the Keilepand. As such, both entities are strongly connected; we only regard the values of Het Keilecollectief for our study though. As such, subcase Keilecollectief differs from subcases Voedseltuin and Keilewerf, meaning that subcase Keilecollectief does not represent physical developments, whereas the others do; subcase Keilecollectief fulfills a more facilitative, intermediate role within the area developments.

5.2. Case 2: Werkspoorkwartier in Utrecht

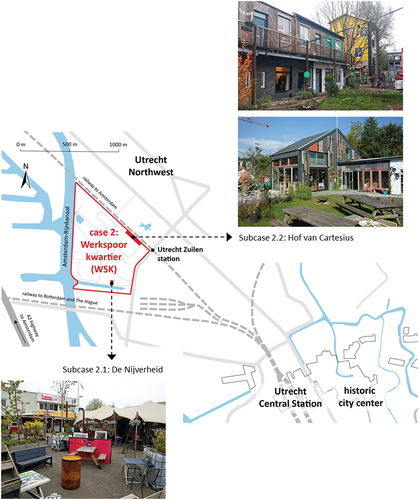

The case we selected in Utrecht is Werkspoorkwartier (WSK), situated in the northwest of the city (). From 2012 on, this former industrial area was organically redeveloped towards an urban working landscape combining the existing city-care enterprises with the creative making industry. Similar to Vierhavensblok, in WSK multiple bottom-up initiatives have emerged over recent years. We first selected De Nijverheid (subcase 2.1), which started in 2017. De Nijverheid is a ‘cultural free haven’ offering workspaces for artists, a cultural cafe, terrace and exhibition spaces and was realized in and around an existing building. The aim of De Nijverheid is to offer affordable workspaces to young, autonomous artists. Furthermore, it is a place where one can enjoy art and culture given the regular public events, mostly from the cafe and adjoining terrace. Currently, De Nijverheid houses over 50 autonomous artists (De Nijverheid, Citationn.d.).

Figure 4. Case 2 and subcases 2.1 and 2.2 in Utrecht (subcase 2.3, Vriendinnen van Cartesius, is not physically located in WSK).

The second subcase in WSK is Hof van Cartesius (HvC; subcase 2.2). HvC is an experimental, green working environment for small, creative entrepreneurs and sustainability entrepreneurs, consisting of various pavilions, clustered around collective, climate adaptive inner gardens. The pavilions were built from discarded materials, following circular economy principles, and partly by the end-users themselves. HvC is a cooperative organization with end users as its members and was realized in phases from 2017 on. Currently, HvC consists of eight pavilions with a total of 3500 m2 of working spaces for 110 entrepreneurs (Hof van Cartesius, Citationn.d.). HvC not only provides green workspaces and semi-public inner gardens but also organizes various activities from festivals to debates and workshops, mostly aimed at promoting sustainability and circularity. HVC has gained a lot of regional and national attention given its innovative approaches. In 2019, an Utrecht branch of Buurman was opened by the initiators of HvC at HvC, in close collaboration with Buurman Rotterdam (see above). We include Buurman Utrecht in our study as part of HvC although it is, like subcase Keilewerf, formally a separate organization. Over the years, the initiators of HvC and several end-users have been closely involved in the development of WSK, exemplified by the involvement in the ‘Werkspoorpad’, a new footpath in WSK among others.

The third subcase in WSK is the collaborative project of two female, freelance professionals and ‘friends’ (‘vriendinnen’ in Dutch) called Vriendinnen van Cartesius (subcase 2.3). From roughly 2012 on, they are active in WSK as agents paving the way for future developments, initially by organizing local, cultural activities generating attention for WSK among others, and later facilitating the area-wide network by organizing meetings and publishing newsletters, as such acting as an intermediate between various stakeholders in WSK. Similar to Vierhavensblok, this last subcase in WSK also differs from the other two, given that no direct, tangible developments were pursued.

6. Findings

6.1. Value maps

show the output-maps we composed regarding the six bottom-up initiatives. shows the combined outputs of subcases 1.1, 1.2, 2.1 and 2.2 (i.e. the physical developments) and shows the combined outputs of subcases 1.3 and 2.3 (i.e. the initiatives with non-physical outputs and a more facilitative role). We drafted separate output-maps for the two types of developments given the differences in outputs. includes economic, social and environmental values, as well as overlapping values, which we denoted as socio-economic or socio-environmental values. Given the variety in social values, we also made subdivisions in types of social values. , in contrast to , shows a lesser variety in values, including only socio-economic and social values and whereas the values of vary between public and private, those of are all public. These differences in outputs are a direct result of the differences in objectives of the initiatives.

Table 1. Combined output-map of subcases 1.1, 1.2, 2.1 and 2.2 (i.e. physical developments).

Table 2. Combined output-map of subcases 1.3 and 2.3 (i.e. non-physical developments).

provide a qualitative overview of output-values, although some outputs of are potentially quantifiable. This applies mainly to private values, but also to some public values, such as the increase in creative industry employment. The policy documents of M4H and WSK that we studied provide some related, quantitative insights as such, e.g. in WSK, the number of jobs in the creative sector has increased from 6% in 2012 to 34% in 2021 (Gemeente Utrecht, Citation2012, Citation2021). Similarly, the 2020 M4H programma-monitor (program monitor in English) reports that in Keilekwartier, of which Vierhavensblok is part, the share of employment in the ‘new making industry’ (arts, crafts and design & engineering among others) has risen to 58% (Programmabureau_M4H, Citation2021). Although one can assume that these area-related numbers are partially caused by the bottom-up activity in both areas, quantitative effects of the bottom-up endeavors specifically, e.g. on the share of creative industry employment, are not available.

Similar to the output-maps, we composed an outcome-map and impact-map. shows the combined outcomes and the combined impacts of all subcases. Contrary to the output-maps, we drew only one outcome-map and one impact-map given that the outputs of together lead to more general outcomes and impacts as presented.

Table 3. Combined outcome-map of all subcases.

Table 4. Combined impact-map of all subcases.

Whereas part of the outputs () is relatively tangible and potentially quantifiable, most outcomes and impacts () are more fundamentally qualitative with one clear exception, being the increased exchange value of lands and buildings (first impact in ). We will reflect on the relevance of quantifying this specific impact-value in Section 7. Noteworthy is that this impact also represents the only economic value in , whereas all others are either social, social-economic, or social-environmental. This is in line with the overall tendency of the tables, which show an emphasis on social (and, e.g. socio-economic) values, justifying the view of bottom-up urban development as social entrepreneurship (Mens et al., Citation2021). Another important, overall insight from the interviews is that particularly the diversity and combinations of (social) values, which accrue to a variety of actors, and, e.g. the many local, cross-sectoral collaborations that accompany it, lead to broad appreciation. Many regard the initiatives, their commitment to specific goals and involvement with the areas they operate in, in combination with the new approaches, as a source of inspiration.

6.2. Broader insights and causalities

Reverting to the hypothetical impact pathway of , we recognize the values and causalities as laid down in this figure. Our data show creatives undertaking a variety of place-based activities, leading to the effect of placemaking, creating new possibilities and opportunities for further redevelopment. The bottom-up initiatives instigate and give direction to these new developments. Subcases Voedseltuin (1.1) and Vriendinnen van Cartesius (2.3) show an exception regarding the actors involved; the primary actors involved in these initiatives are not from the creative industry, although the actors of both subcases collaborate with many local creatives. Characteristic for most initiatives is that they are driven by strong (creative) communities. The municipality of Utrecht states that ‘it is particularly these communities that generate attention, dynamics, public activity and new employment’ (Gemeente Utrecht, Citation2021, p. 13; translation by authors), confirming the outcome of placemaking. We will fall short by only addressing this temporary role of placemaking though, which we will further explicate.

The (creative) communities of physical developments settle in formerly unused buildings, turning them into co-working spaces (subcases 1.2 and 2.1), or turning former wastelands into use (subcases 1.1 and 2.2). They represent a new, more intense usage of already sparse urban space, in which experimenting is key. Several initiatives qualify as ‘urban living labs’ (Steen & van Bueren, Citation2017) and have become leading examples of urban sustainability and socio-technological innovation (subcases 1.1, 1.2 and 2.2). All initiatives show strong involvement to the place where they operate and its surroundings. Moreover, they change the functionalities of the areas, which transform from former industrial working landscapes into mixed-use areas. As a result, the mental conceptions and positions of the areas in the cities change; they become alternative locations to recreate, enjoy culture, have a drink, conduct experiments, learn or take part in a debate, as such attracting many new and other people. Tangible representations of this new use, other than the initiatives themselves, are the new footpaths that were erected in both WSK and Vierhavensblok to accommodate the growing number of visitors/pedestrians.

The communities display a strong sense of collectivity; they collaborate, exchange ideas and resources, share a common drive to innovate and inspire each other and others. An example is the aspect of circular building in WSK. In this area, circular building was initially one of the core ambitions and achievements of subcase 2.2 (HvC). Multiple others however, followed this circular approach. Another example is the establishment of Buurman Utrecht at HvC, based on its Rotterdam counterpart at Keilewerf 1. Other developments include the recently established foundation Keilekwartier in Vierhavensblok, uniting the communities and entrepreneurs surrounding De Voedseltuin and aiming for collaboration in area-wide developments. Similarly, in WSK, possibilities for a public-private area organization are explored. Both organizations, in which the bottom-up initiatives play a prominent role, are (being) initiated with the aim to facilitate area-wide collaborations and developments. Ambitions regarding ,e.g. innovative waste collection, greening and car-sharing have been mentioned in this regard.

Authorities increasingly acknowledge the relevance and values of bottom-up initiatives in favor of a lively, healthy city and express desires to retain and institutionalize these values. The broad value creation and this appreciation are, among others, the result of a continuous interplay between municipalities and bottom-up initiatives, i.e. the initiatives we studied act upon opportunities and tend to follow municipal policies to deliberately or undeliberate safeguard their continuance. Given their accomplishments, new approaches and the awareness they create regarding the relevance of certain values, they in turn influence municipal policy formation in the domain of urban development (Programmabureau Rotterdam Makers District, Citation2019; Gemeente Utrecht, Citation2021), which creates new opportunities and possibilities. In this respect, actors involved in bottom-up urban development, aside from being social entrepreneurs, can be regarded as policy entrepreneurs (Kingdon, Citation2011). The effect of bottom-up initiatives inspiring, e.g. municipalities to approach urban development in new ways, together with initiatives fueling innovation as described above, transcends that of initial and temporary placemaking.

Displacement of creatives or discontinuance of bottom-up initiatives because of rising property prices and market mechanisms has not (yet) occurred at the areas we studied, although a fear of such future displacement has often been expressed by interviewees. Moreover, some bottom-up initiatives at M4H (i.e. others than the ones we studied) will end soon, given terminated rental agreements. Related to the above-mentioned influences on policy formation, local authorities and initiatives themselves among others are looking for methods and (policy) instruments to prevent displacement or stimulate bottom-up endeavors in general. An example is the recently established Stadsmakersfonds (City Maker Fund in English): a revolving fund facilitating bottom-up initiatives with social objectives. This fund, in which the Province of Utrecht is the main investor, represents a new method to finance bottom-up initiatives. The second realization phase of subcase HvC was the pilot project of this new fund.

The value maps and above insights led to the empirical impact pathways of . This figure summarizes and bundles the values that lead to impacts, i.e. rearranges these values in such a way that their causalities are made insightful. as such, is an elaboration and nuance of , based on our empirical findings. Comparison of both figures shows that value creation is more versatile than assumed, exemplified by differences in the number of values between, e.g. the output- and outcome-boxes. Moreover, shows that the impacts not only relate to specific area developments but are broader, as explicated. These wider impacts, visualized by the lower impact-box in , are a result of both the outcomes and area-related impacts; hence, the two arrows that lead to this impact-box and that we speak in plural of impact pathways.

7. Discussion

The previous section provided a detailed insight into the comprehensive values of bottom-up initiatives. These values are a result of intense collaborations between, and joint efforts of bottom-up initiators and others (e.g. municipalities), in contrast to, e.g. earlier squatters’ initiatives, which mainly opposed the established order. An important nuancing concerns the outcomes and impacts; although the outputs are a direct result of the bottom-up endeavors, the outcomes and impacts are not a result of the bottom-up initiatives alone; these effects were also influenced by activities of others, such as more conventional actors in urban development. Therefore, the effects of the bottom-up initiatives cannot be regarded separately from other, simultaneous developments. Moreover, some impacts of bottom-up endeavors remain difficult to prove or pinpoint precisely. An example concerns the volunteer work at De Voedseltuin (subcase 1.1). Some interviewees indicated that this work by vulnerable, local citizens saves social costs and health-care costs. However, to verify such long-term cost-saving effects, detailed monitoring is necessary, which is a costly affair. Therefore, we did not include such alleged impacts (e.g. reductions of health-care costs) in our findings. Another example concerns statements by interviewees that bottom-up initiatives contribute to healthy, livable cities. This raises questions of what precisely constitutes a healthy city and which standards must be met to achieve this. We did mention this impact (i.e. contributions to healthy cities) in our findings though, given that a significant number of interviewees indicated such effects and given that it corresponds with own observations, albeit based on our own standards. We also included the effects of rising land and property prices in our findings, which too can be contested. One interviewee stated that this increase would have happened regardless of the bottom-up developments since it is a general trend. Although we acknowledge the validity of this argument, we maintain our standpoint on the influence of bottom-up endeavors on rising land and property prices, since it is undoubtedly of influence. What can be questioned is to what degree, again exemplifying the influence of other developments on the effects we identified. It also shows why, e.g. monitoring price developments in light of our study is pointless, since such quantifications do not provide insights into the causes of rising prices, making such quantitative data irrelevant.

The concept of value maps has proved useful in structuring and categorizing the values created by bottom-up initiatives and offering general, qualitative overviews of values and interrelationships. The insights enable pinpointing specific values and allow more detailed studies towards specific categories of values. As mentioned, various outputs are potentially quantifiable, whereas the outcomes and impacts are generally not. Given the multifaceted character of some values, classifying them into a specific category remains somewhat arbitrary. Some values qualify, e.g. as both socio-economic and socio-spatial. Nevertheless, mapping values using the framework of is a useful method for structuring and gaining general insights into the (types of) values that are created and its beneficiaries.

Regarding our case selection, we have only studied successful bottom-up initiatives. In the M4H area however, also lesser, or non-successful bottom-up initiatives took place, which did not generate a wide range of values. Bottom-up initiatives as such do not always lead to broad value creation as presented; it depends, e.g. on the ability of those involved to successfully reach goals, and the context in which they operate. It should also be noted that the ‘success’ in both areas we studied, is partially due to an absence of direct housing pressures in the areas; this enabled the areas to grow towards their current, innovative state. Finally, we only studied two Dutch cases. Other or international contexts may yield other insights regarding the values created.

8. Conclusions

In this article, we questioned which values successful bottom-up urban developments bring forth and scrutinized path dependencies between values in terms of impact pathways. Our research shows that bottom-up urban development generates more impact than generally assumed, i.e. initiatives have a broader impact than merely the areas in which they operate. Our assumption that the activities of creatives lead to placemaking, subsequently accelerating further area developments was affirmed. The effects of bottom-up urban development transcend this temporary placemaking practice though. The initiatives we studied respond to policy opportunities and actively seek collaboration with various actors to realize goals. The richness of the created values, which accrue to a variety of actors, together with the broad collaborations (e.g. with local authorities), leads to widespread appreciation. This affects municipal urban planning policies, on the one hand, and leads to innovations in urban development on the other. As such, bottom-up approaches are being institutionalized to a certain extent. Contrary to our theoretical assumptions, we have not yet identified structural displacement of creatives or discontinuance of initiatives to date, although this remains a point of concern.

The approach of drafting value maps and applying theory-based evaluation proved useful, given the insights gained. These insights can foster the public debate on the legitimacy of bottom-up urban development and help practitioners identify relevancies of initiatives for different stakeholders. In broader perspective, our framework provides a structured method to scrutinize outputs, outcomes and impacts of developments, which can be useful to other scholars and practitioners aiming thorough value analyses. It can, for example, be applied to conventional, market-led urban developments in comparison to alternative approaches. Our model as such, is more generically applicable to discussions on impact development.

Our study has limitations and shortcomings. The analyses were limited to two areas with a total of six bottom-up subcases, which raises the question whether findings can be generalized. As part of a larger study towards bottom-up urban development, however, we also studied other cities and areas. Although these studies were not part of the analyses in this article, we perceived similarities from which we preliminarily conclude that our findings are valid. We also limited our analyses to the values of successful bottom-up initiatives. The values presented in this article are therefore not representative for all bottom-up initiatives, but only for ones that succeed in reaching goals.

A recommendation for future research is to deepen insights on the general values as presented. We were, e.g. not able to identify the long-term effects of the voluntary work at subcases Voedseltuin and Hof van Cartesius. Does this work indeed improve the well-being of volunteers, thus saving health-care costs in the long term? More detailed insights and, e.g. quantifications of outputs could also further strengthen the evidence base regarding the values of bottom-up initiatives, justifying the support for such endeavors in a market-driven, neoliberal context.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the individual practitioners who have been interviewed in the context of this research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adams, D., & Tiesdell, S. (2010) Planners as market actors: Rethinking state–market relations in land and property, Planning Theory & Practice, 11(2), pp. 187–207. doi:10.1080/14649351003759631.

- Austin, J., Stevenson, H., & Wei-Skillern, J. (2012) Social and commercial entrepreneurship: Same, different, or both?, Revista De Administração, 47(3), pp. 370–384. doi:10.5700/rausp1055.

- Biedenbach, T., & Jacobsson, M. (2016) The open secret of values: The roles of values and axiology in project research, Project Management Journal, 47(3), pp. 139–155. doi:10.1177/875697281604700312.

- Boonstra, B. (2015) Planning Strategies in an Age of Active Citizenship: A Post-Structuralist Agenda for Self-Organization in Spatial Planning (Groningen: InPlanning).

- Boonstra, B., & Boelens, L. (2011) Self-organization in urban development: Towards a new perspective on spatial planning, Urban Research & Practice, 4(2), pp. 99–122. doi:10.1080/17535069.2011.579767.

- Buitelaar, E., Grommen, E., & Van der Krabben, E. (2017) The self-organizing city: An analysis of the institutionalization of organic urban development in the Netherlands, In: G. Squires, E. Heurkens, & R. Peiser (Eds) Routledge Companion to Real Estate Development, pp. 169–182 (London: Routledge).

- Carmona, M., De Magalhães, C., & Edwards, M. (2002) Stakeholder views on value and urban design, Journal of Urban Design, 7(2), pp. 145–169. doi:10.1080/1357480022000012212.

- Certo, S. T., & Miller, T. (2008) Social entrepreneurship: Key issues and concepts, Business Horizons, 51(4), pp. 267–271. doi:10.1016/j.bushor.2008.02.009.

- Clark, C., Rosenzweig, W., Long, D., & Olsen, S. (2004) Double bottom line project report: Assessing social impact in double bottom line ventures. Berkeley: Center for Responsible Business, University of California.

- Colomb, C. (2012) Pushing the urban frontier: Temporary uses of space, city marketing, and the creative city discourse in 2000s berlin, Journal of Urban Affairs, 34(2), pp. 131–152. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9906.2012.00607.x.

- Courage, C. (2017) Arts in Place: The Arts, the Urban and Social Practice (London: Routledge).

- Courage, C., Borrup, T., Rosario Jackson, M., Legge, K., Mckeown, A., & Platt, L. (Eds) (2020) The Routledge Handbook of Placemaking (Abingdon, Oxon and New York: Routledge).

- Courage, C., & McKeown, A. (2019) Creative Placemaking: Research, Theory and Practice (Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge).

- Danenberg, R., & Haas, T. (2019) New trends in bottom-up urbanism and Governance—Reformulating ways for mutual engagement between municipalities and citizen-led urban initiatives, In: M. Arefi & C. Kickert (Eds) The Palgrave Handbook of Bottom-Up Urbanism, pp. 113–129 (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan).

- De Nijverheid. (n.d.) De Nijverheid. Available at http://www.denijverheid.org/

- Dembski, S. (2020) ‘Organic’ approaches to planning as densification strategy? the challenge of legal contextualisation in Buiksloterham, Amsterdam, The Town Planning Review, 91(3), pp. 283–303. doi:10.3828/tpr.2020.16.

- Finn, D. (2014) DIY urbanism: Implications for cities, Journal of Urbanism International Research on Placemaking and Urban Sustainability, 7(4), pp. 381–398. doi:10.1080/17549175.2014.891149.

- Flew, T. (2013) Introduction: Creative industries and cities, In: T. Flew (Ed) Creative Industries and Urban Development: Creative Cities in the 21st Century, pp. 1–14 (Abingdon, Oxon and New York: Routledge).

- Florida, R. (2002) The Rise of the Creative Class (New York: Basic Books).

- Gemeente Utrecht. (2012) Ontwikkelingsvisie Werkspoorkwartier - de transformatie van een bedrijventerrein (Utrecht: Gemeente Utrecht).

- Gemeente Utrecht. (2021) Omgevingsvisie Werkspoorkwartier. de transformatie van een werklandschap (Utrecht: Gemeente Utrecht). Available at https://www.werkspoorkwartier.nl/assets/Uploads/20210617-Omgevingsvisie-Werkspoorkwartier.pdf

- Gregory, J. (2016) Creative industries and urban regeneration – the Maboneng precinct, Johannesburg, Local Economy, 31(1–2), pp. 158–171. doi:10.1177/0269094215618597.

- Hart, S. L. (1971) Axiology - theory of values, Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 32(1), pp. 29–41. doi:10.2307/2105883.

- He, J., & Gebhardt, H. (2014) Space of creative industries: A case study of spatial characteristics of creative clusters in Shanghai, European Planning Studies, 22(11), pp. 2351–2368. doi:10.1080/09654313.2013.837430.

- Hof van Cartesius. (n.d.) Hof van cartesius. Available at https://hofvancartesius.nl/.

- Horelli, L., Saad-Sulonen, J., Wallin, S., & Botero, A. (2015) When self-organization intersects with urban planning: Two cases from helsinki, Planning Practice & Research, 30(3), pp. 286–302. doi:10.1080/02697459.2015.1052941.

- Igalla, M., Edelenbos, J., & van Meerkerk, I. (2019) Citizens in action, what do they accomplish? A systematic literature review of citizen initiatives, their main characteristics, outcomes, and factors, VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 30(5), pp. 1176–1194. doi:10.1007/s11266-019-00129-0.

- Iveson, K. (2013) Cities within the city: Do-it-yourself urbanism and the right to the city, International Journal of Urban & Regional Research, 37(3), pp. 941–956. doi:10.1111/1468-2427.12053.

- Jarvis, D., Lambie, H., & Berkeley, N. (2009) Creative industries and urban regeneration, Journal of Urban Regeneration & Renewal, 2(4), pp. 364–374.

- Kingdon, J. W. (2011) Agendas, Alternatives, and Public Policies, Updated second ed. (Boston: Little, Brown).

- Liket, K. C., Rey-Garcia, M., & Maas, K. E. (2014) Why aren’t evaluations working and what to do about it: A framework for negotiating meaningful evaluation in nonprofits, American Journal of Evaluation, 35(2), pp. 171–188. doi:10.1177/1098214013517736.

- Maas, K., & Grieco, C. (2017) Distinguishing game changers from boastful charlatans: Which social enterprises measure their impact?, Journal of Social Entrepreneurship, 8(1), pp. 110–128. doi:10.1080/19420676.2017.1304435.

- Macmillan, S. (2006) Added value of good design, Building Research & Information, 34(3), pp. 257–271. doi:10.1080/09613210600590074.

- Markusen, A., & Gadwa, A. (2010) Creative Placemaking (Washington, DC: National Endowment for the Arts).

- Martin, M., Deas, I., & Hincks, S. (2019) The role of temporary use in urban regeneration: Ordinary and extraordinary approaches in Bristol and Liverpool, Planning Practice & Research, 34(5), pp. 537–557. doi:10.1080/02697459.2019.1679429.

- Matoga, A. (2019) Governance of temporary use, Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers-Urban Design and Planning, 172(4), pp. 159–168. doi:10.1680/jurdp.18.00052.

- Mayne, J. (2015) Useful theory of change models, Canadian Journal of Program Evaluation, 30(2), pp. 119–142. doi:10.3138/cjpe.230.

- Mens, J., van Bueren, E., Vrijhoef, R., & Heurkens, E. (2021) A typology of social entrepreneurs in bottom-up urban development, Cities, 110(103066), pp. 1–14. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2020.103066.

- Mulgan, G. (2010) Measuring social value, Stanford Social Innovation Review, 8(3), pp. 38–43.

- Mulgan, G., Breckon, J., Tarrega, M., Bakhshi, H., Davies, J., Khan, H., & Finnis, A. (2019) Public Value: How Can It Be Measured, Managed and Grown? (London: Nesta).

- Ormiston, J., & Seymour, R. (2011) Understanding value creation in social entrepreneurship: The importance of aligning mission, strategy and impact measurement, Journal of Social Entrepreneurship, 2(2), pp. 125–150. doi:10.1080/19420676.2011.606331.

- Palermo, P. C., & Ponzini, D. (2015) Place-Making and Urban Development: New Challenges for Contemporary Planning and Design (London: Routledge).

- Papachristou, I. A., & Rosas-Casals, M. (2015) The many urban languages or why there is always a gap between bottom-up initiatives and top-down processes, in: Resurbe II: International conference on urban resilience. Bogotá.

- Partanen, J. (2015) Indicators for self-organization potential in urban context, Environment and Planning: D, Society & Space, 42(5), pp. 951–971. doi:10.1068/b140064p.

- Porter, M. E., & Kramer, M. R. (2011) The big idea: Creating shared value, Harvard Business Review, 89(1–2), pp. 62–77.

- Porter, M. E., & Kramer, M. R. (2019) Creating shared value how to reinvent Capitalism—And unleash a wave of innovation and growth, In: G. Lenssen & N. Smith (Eds) Managing Sustainable Business, pp. 323–346 (Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands).

- Pradel-Miquel, M. (2021) Analysing the role of citizens in urban regeneration: Bottom-linked initiatives in Barcelona, Urban Research & Practice, 14(3), pp. 307–324. doi:10.1080/17535069.2020.1737725.

- Pratt, A. (2018) Gentrification, artists and the cultural economy, In: L. Lees & M. Phillips (Eds) Handbook of Gentrification Studies, pp. 346–362 (Cheltenham and Northampton: Edward Elgar Publishing).

- Programmabureau_M4H. (2021) Programmamonitor M4H 2020. Samenvatting (Rotterdam: Programmabureau M4H). Available at https://m4hrotterdam.nl/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/M4H_monitor_2020_Issuu.pdf

- Programmabureau Rotterdam Makers District. (2019) Ruimtelijk raamwerk Merwe-vierhavens Rotterdam - toekomst in de maak (Rotterdam: Programmabureau Rotterdam Makers District). Available at https://m4hrotterdam.nl/nieuws/vaststelling-ruimtelijk-raamwerk-m4h

- Rabbiosi, C. (2016) Urban regeneration ‘from the bottom up’ critique or co-optation? notes from Milan, Italy, City, 20(6), pp. 832–844. doi:10.1080/13604813.2016.1242240.

- Rauws, W., & de Roo, G. (2016) Adaptive planning: Generating conditions for urban adaptability. lessons from Dutch organic development strategies, Environment and Planning B-Planning & Design, 43(6), pp. 1052–1074. doi:10.1177/0265813516658886.

- Stam, K., & Peek, G. (2019) Gebiedsontwikkeling anders organiseren. De Voedseltuin, Rotterdam, In: G. Helleman, S. Majoor, V. Smit, & G. Walraven (Eds) Plekken van hoop en verandering: Samenwerkingsverbanden die lokaal verschil maken, pp. 115–122 (Utrecht: Academische Uitgeverij Eburon).

- Steen, K., & van Bueren, E. M. (2017) Urban Living Labs: A Living Lab Way of Working (Amsterdam: AMS Institute).

- Strydom, W., Puren, K., & Drewes, E. (2018) Exploring theoretical trends in placemaking: Towards new perspectives in spatial planning, Journal of Place Management and Development, 11(2), pp. 165–180. doi:10.1108/JPMD-11-2017-0113.

- Thompson, J. L. (2002) The world of the social entrepreneur, International Journal of Public Sector Management, 15(5), pp. 412–431. doi:10.1108/09513550210435746.

- Toolis, E. E. (2017) Theorizing critical placemaking as a tool for reclaiming public space, American Journal of Community Psychology, 59(1–2), pp. 184–199. doi:10.1002/ajcp.12118.

- van den Berg, B., Vunderink, L., van Wieren, C., Nijland, A., Willems, B., & Perdeck, N. (2019) Ontmoet de makers van de keilewerf - de werf waar je alles kan (laten) maken (Rotterdam: Keilewerf BV).

- von Schönfeld, K. C., & Tan, W. (2021) Endurance and implementation in small-scale bottom-up initiatives: How social learning contributes to turning points and critical junctures, Cities, 117(103280), pp. 1–13. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2021.103280.

- Weerawardena, J., & Mort, G. S. (2006) Investigating social entrepreneurship: A multidimensional model, Journal of World Business, 41(1), pp. 21–35. doi:10.1016/j.jwb.2005.09.001.

- Weiss, C. H. (1995) Nothing as practical as good theory: Exploring theory-based evaluation for comprehensive community initiatives for children and families, In: J. Connell, A. Kubisch, L. Schorr, & C. Weiss (Eds) New Approaches to Evaluating Community Initiatives: Concepts, Methods, and Contexts, pp. 65–92 (New York: The Aspen Institute).

- Weiss, C. H. (1997) Theory-based evaluation: Past, present, and future, New Directions for Evaluation, 76, pp. 41–55. doi:10.1002/ev.1086.

- Yin, R. K. (2014) Case Study Research Design and Methods (Los Angeles: Sage).

- Young, R. (2006) For what it is worth: Social value and the future of social entrepreneurship, Social Entrepreneurship: New Models of Sustainable Social Change, 18(3), pp. 56–73.