ABSTRACT

In this paper, we utilise data from biographical interviews to examine the values held by UK planners and whether and how they promote progressive planning ideals in their everyday work, often despite countertendencies in planning systems and organisational priorities. Our research concurs with the idea of a mildly progressive, yet conservative, positioning: in Hillier’s (2002) terms, some planners are ‘on a mission’ but these missions vary from common-good orientations, a desire to do ‘better’ planning in a putative public interest, to more justice-based commitments to certain progressive ‘causes’ such as particular publics, cultural heritage, special places, or the environment.

Introduction: what values do planners hold/identify with?

Worldwide there are many thousands of people who would self-identify as planners, making it dangerous to over-generalise about the values that planners might hold. That said, the idea that groups of people working on similar issues, educated, and working in relatively small numbers of places, such as planners, will be ‘like-minded’ has a large degree of truth (Hendler & Bickenbach, Citation1994). Clifford and Tewdwr-Jones (Citation2013) find a great deal of similarity in the views of hundreds of local authority planners across Great Britain to planning reforms and a distinct sense of meaning around their role as planners. Likewise, Loh and Norton (Citation2013) find more similarities than differences across planners in public and private sector organisations.

Such like-mindedness is, however, likely to vary significantly too, a feature explored in research through analysis of planning cultures (Sanyal, Citation2005; Othengrafen, Citation2014). Historically, this literature has been dominated by a focus on national systems,Footnote1 not least as this is where the planning profession is ‘regulated’, but more recently the significance of local variation has been acknowledged (Valler & Phelps, Citation2018). In general terms, planners exhibit mildly ‘progressive’ value orientations,Footnote2 working pragmatically within contexts shaped heavily by state and organisational structures and under capitalism where property rights heavily frame what is possible (Harvey, Citation1985; Fox-Rogers & Murphy, Citation2016; Jackson, Citation2020). While it is dangerous to assume all planners aspire to contribute to societal goals such as greater social and ecological justice or even care about the outcomes of their recommendations (Allmendinger, Citation1996; Allmendinger & Tewdwr-Jones, Citation2002), there is evidence that many do. Previous research also tells us that, faced with the pressures of workload and institutional politics, many planners prefer ‘neutrality’, to become in Hillier’s (Citation2002) terms, ‘chameleons’, blending into the background. Such an orientation may reflect planners’ own ideas of their role, for example as neutral facilitators (Howe, Citation1994). Some also ascribe this phenomenon to self-selection, for example, Cook and Sarkissian 2000 (in Hillier, Citation2002, p. 206) note that Australian planners ‘are, in general, the sort of people who support the status quo and value compliance’.

Hillier’s own research notes that this chameleon tendency develops from, and contributes to, national and local planning cultures, generating path dependency and conservatism in the profession. There is evidence too, from a variety of national contexts, that ‘neutral’ positioning on the part of planners has become more significant in the past two decades as local government power and resources have often been undermined and a neoliberal discourse has further embedded itself into government practices and assumed a wider cultural hegemony (Clifford & Tewdwr-Jones, Citation2013; Grange, Citation2017; Lauria & Long, Citation2017; Raco, Citation2018). Considering the everyday practices of planners, Clifford (Citation2022) suggests that an important part of a commonly held notion of what a ‘good planner’ is includes following policy and legislation, so that over time under such neoliberal hegemony, planners may increasingly be working in less progressive ways due to a governance context that requires this from its state actors.

Such behaviour is likely supported by a rise in private sector employment, further underpinned by planners working across national boundaries, where transnational corporations create their own ‘regulatory’ structure above and beyond national professional ones (Suddaby et al., Citation2007). Clients may be transnational in operation too, so we can expect a small minority of planners to be working globally, to a set of personal and corporate norms, and others to be heavily shaped by their experiences of planning in a nation and locality in a particular time.

At whatever scale of working, planners may show signs of alternative practice, of promoting a ‘mission’ in Hillier’s terms. Such missions can be more extreme versions of market fundamentalism, yet, as our research below sows, are more likely to be small-scale and pragmatic forms of progressive planning. As we report below, missions can emerge at any time in a career. Or they can frame its entirety, sometimes necessitating moving to organisations with similar values, or opting for self-employment which allows for greater freedom (Jackson, Citation2020). In the empirical research that follows, we mobilise Hillier’s idea of planners as missionaries and chameleons to explore the values held by UK planners in the late 2010s. We use a method rarely seen in planning scholarship, that of the biographical interview, to go deep into both the values held by individual planners but also where such values may have emerged from and been subsequently shaped; and we explore the significance of the organisational contexts in allowing them to flourish.

Planners as missionaries and chameleons

Hillier’s dualistic conception of planners as missionaries and chameleons is clearly an over-simplification of a range of value positions planners might occupy and Hillier notes that this can change across a planners’ career depending particularly on the ‘opportunity structure’ for influence in an organisation and the individual’s capacity at a given time to mobilise the resources needed to take a ‘missionary position’. This distinction is also considered by Howe (Citation1980) who talks of ‘technicians’, ‘politicians’ and ‘hybrids’. The fundamental difference between missionaries/politicians and chameleons/technicians is that the latter engage in passive planning to ‘allow process to take precedence and elected representatives to take whatever decision they wish’ (Hillier, Citation2002, p. 196). Hillier’s work thus acknowledged the importance of local politicians more than some other work previously. It also studied public sector employed planners whereas we wish to extend this definition to substitute ‘client’ for ‘elected representatives’ to embrace private sector work, while also noting the much more blurred nature of the distinction between public and private sectors in contemporary UK planning (Steele, Citation2009; Schoneboom, Citation2023). The focus of planning on ‘clients’ is now a feature of planning across public and private sectors and this orientation has ideological consequences (Harris & Thomas, Citation2011; Campbell et al., Citation2014; Zanotto, Citation2019). McClymont (Citation2014) sees the two camps as ‘planner as facilitator’ and planner as ‘just professional’ emphasising the deontological and consequentialist positions of previous research into planners’ values (Howe, Citation1994).

Why are some planners’ chameleons? Hillier (Citation2002, p. 198) notes that ‘chameleon like behaviour results from a desire to maintain a salaried job, which desire takes precedence over caring about particular planning outcomes’. So, the influence from employers and precarity of contracts has an important role in shaping planner’s progressive tendencies. In many nations, the contractual situations of planners have shifted more toward agency style working although this remains in the minority (Clifford, Citation2018). Similarly, evidence suggests that local authorities and private sector employers have a stronger corporate steer on what planning can and cannot do and what planners can and cannot say (Vigar, Citation2012). And Howe (Citation1994, p. 174) notes that a small minority of planners in her survey had very little ethical compass at all which resulted from a cynical position or from working in a corrupt context. In such instances, a chameleon disposition is inevitable. In reality, most planners, at least below very senior levels, are likely walking a tightrope between their own values and organisational compliance (Kitchen, Citation1997). Contrary to Hillier’s statement that chameleon planners ‘play the game of organisational survival’, all planners likely do this to varying degrees, pushing on some issues, not on others, and at different times in their career, while all the while reading the institutional politics, which makes their working lives easier or harder.

By contrast missionaries work to enable particular outcomes that are of concern to them as individuals, in keeping with professionals in other domains such as ‘cause lawyering’ (Barclay & Marshall, Citation2005). While the focus of much planning research has been on using a missionary role to advocate progressive causes, you can be a missionary to facilitate forms of market fundamentalism (Hillier, Citation2002; Clifford, Citation2020). But such planners are relatively small in number, at least in the Anglo-Saxon worlds that form the bulk of the existing research. In terms of progressive causes Hillier usefully distinguishes between justice-based disadvantages (countering the violation of a minority’s rights) and common-good-based disadvantages (the public interest). It is the latter conception that has occupied planning research historically and recent research also finds a commitment to public service as well as the public interest among young planners in South-East England (Nelson & Neil, Citation2021) even while defining precisely what that might mean remains difficult (Campbell & Marshall, Citation2002). By contrast Jackson (Citation2020) finds mid-career planners in Victoria, Australia less committed to public service and less hopeful of their ability to affect any sort of change. Our own research suggests such disillusionment may set in as planners progress through their career (Slade et al., Citation2019). We should also note the importance of the context. Planning in Victoria has been subject to a particular form of neoliberal urban development which will affect the way planners’ see their potential to affect change (Jackson, Citation2020). South-East England (in contrast with the much of the rest of England) has a planning system comparatively well-resourced through the capture of higher land values through indirect land taxes (Campbell et al., Citation2014; Ferm & Raco, Citation2020).

Such research plays into a theme of recent literature which suggests that planners’ have less discretion, or ‘acting space’ than previously (Grange, Citation2013). Historically Howe (Citation1994) notes that about a quarter of US planners felt severely constrained in terms of pursuing the sort of planning they felt necessary. Campbell et al. (Citation2014) suggest that the space is there, but the hegemony of neoliberal discourse means planners do not see the potential spaces that do exist. Planners’ recommendations can lean heavily on the anticipated response of clients (politicians, landowners, developers) and latterly as more planning work is done by large global professional services firms, shareholder value has been shown to heavily influence planning work (Linovski, Citation2023). Working in such contexts shapes future behaviour generating ‘detachment’ from value orientations, ‘[private sector] planners narrow the lens through, which they reflect upon their work and establish a sense of distance between their practices, planning values, and the politics of their work’ (Zanotto, Citation2019, p. 49). Planners scope to influence outcomes is thus reduced to very minor forms of mitigation (Hillier, Citation2002; Schoneboom, Citation2023, esp. chapters 2–5). Planners are thus likely, and necessarily given their limited actual power, pragmatic above all else but the context heavily constrains the acting space available (Vigar, Citation2012).

While the focus in the literature has been primarily on planners employed in government, we should be alive to the differences in values potentially held by those planners working in the private and third sectors. Previous research has suggested that there is a great deal of value confluence between public and private sector planners (Loh & Norton, Citation2013; Linovski, Citation2019) and that this ‘shared sub-culture’ might be of long-standing (Reade, Citation1987). Less attention has been paid to the differences between the values held by planners employed across the private sector. Such employment is highly variegated with many planners occupying niches related to citizen advocacy, environmental protection, the promotion of heritage assets, or taking a pro-equity stance on mainstream practice for example, as opposed to working primarily to gain planning consent for large developers. Even within individual consultancies certain workplace cultures can promote and actively encourage, through hiring strategies for example, diverse views (see for example Schoneboom, Citation2023). We would therefore expect to find some planning consultants displaying common-good or justice-based positions in determining what work to take on and in negotiations with clients (Gunn & Vigar, Citation2012; Loh & Arroyo, Citation2017). But consultants can be constrained by wider corporate goals and market conditions; perhaps in times of recession ethical principles might be more ‘fluid’.

Hirschman’s (Citation1970) concept of an employee’s choices being ‘exit’ ‘voice’ or ‘loyalty’ in a given workplace situation is useful here. Jackson (Citation2020) notes that most mid-career planners are loyal, but a small minority choose the exit, to find organisations where their ‘mission’ can play out (see also Vigar, Citation2012; Schoneboom, Citation2023). In our interviews that follow, we explored reasons for moving jobs and whether this related to attempts to actualise more ideal roles in terms of value confluence between workplace and planners or whether they were driven by more pragmatic reasons such as salary, career progression or location.

In sum, there is often dissonance between planner’s actual roles and their ideal roles (Howe, Citation1994). In the section that follows, we highlight our approach to researching this dissonance, how planners’ values are reflected in the work they do at various points in their career, and how they have or have not found meaning and a mission to guide their working lives.

Methodology: biographical interviews with planners

In this paper, we mobilise 23 biographical interviews conducted as part of the ‘Working in the Public Interest’ project (https://witpi.sites.sheffield.ac.uk/). These interviews were conducted with a cross-section of planners working in all parts of the UK, and explored their career paths, professional self-understanding, working practices and values. Seven interviewees had just worked in the public sector, seven just in the private sector and nine with experience of both sectors. There was also a mix of seniority, length of time in the planning profession and personal characteristics (such as race and gender).

The interviewees were mainly recruited through networks of the project’s academic team and cannot claim to be ‘representative’ of the planning profession (indeed by dint of the approach to selection, arguably the planners interviewed were perhaps more likely to be engaged practitioners than might be average), but they do provide an insightful cross-section of planners. The interviews were semi-structured and included questions on the purpose of planning and the meaning of the public interest, but these were asked in the context of a biographical or professional life history interview which started with asking the interviewee to draw a timeline of their career and narrate their CV so as to try and develop a rich understanding of the evolution of professional roles and identities (Lewis, Citation2008). Interviewees were asked about their values but were not explicitly asked about their ‘mission’. Interviews were recorded, fully transcribed and analysed by two different academics coding them according to agreed key themes.

The biographical interview approach has rarely been used in planning scholarship despite the great potential value in understanding professional values and practices (albeit there has been some work drawing on ‘practice stories’ of planning professionals such as that of John Forester). The turn to biographical methods in the social sciences relates to a need to foreground the realities of lived experience, which are vital given that things like government policies are filtered through networks of relationships and shared assumptions (Chamberlayne et al., Citation2000). Rustin therefore argues that ‘the idea that the production as well as the reproduction of social identities takes place at an individual, subjective level, should be of interest to many who must be concerned to understand what spaces exist in which meaningful lives and careers can be made’ (Rustin, Citation2000, p. 49).

Bourdieu (1986 in Denzin, Citation2011) raises the issue of the ‘biographical illusion’ whereby the joint interests of the persona narrating their biographical history and the researcher is to construct a coherent story with purpose even though in reality a biography is almost always a discontinuous series of events. Denzin (Citation2011) counters that whether coherence is an illusion or not, it is interesting in how individuals seek to give coherence to their lives when talking through their self-autobiography because the narratives and ideologies that underpin such attempts thus reveal themselves. This talks to the way that organising a professional life story will involve the logic of a social field, a larger society and culture where life is played out and within which the life history is being narrated, with particular meanings attached to positions within these fields. This helps understand not just individual life histories but broader social realities (Rosenthal, Citation2004; Kohli, Citation2011).

Thus, a biographical interview approach is particularly useful in understanding not just the individual careers of a small group of planners but the broader sense-making and positionality of the planning profession in the UK, and the way that people might experience the act of doing planning work and the identities and values they attach to that career. By its nature, the focus of the interview is how an individual narrates their professional story, and so questions of reliability and validity are somewhat different to those in more conventional interview research.

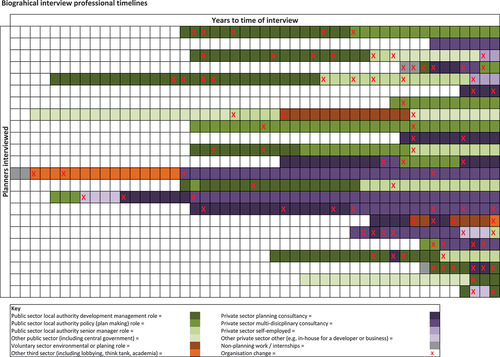

For each of our 23 interviews, we produced a timeline of the career of each of these planners, including which sector where they worked and any time they changed employer, which is reproduced here in an anonymised way as . The full set of interviews informed a characterisation of ‘planner types’ seen across the public and private sectors (see Clifford et al., Citation2020). For the purposes of this paper, though, we focus on the potentially progressive missions, which motivate some contemporary planners in their daily practice as illustrated from selected planners within this larger dataset.

Narrated planning careers: values, purposes, and being ‘on a mission’

Across all our biographical interviews, there was usually (although not in every case) a sense of a mildly progressive mission from our planners but the nature of that mission did vary. For example, all interviewees offered a definition of the public interest and tended to view this as important for justifying the purpose of planning, but definitions offered tended not to be that detailed or reflective. Typical was PIanner 1 commenting that ‘it should generally be about making people’s lives better, bearable even, so it’s about everybody, it’s about the community, the public, however you want to describe it, as opposed to an individual and their particular needs or wishes’.

Our interviews began with a discussion of the route into planning. Although the most common route was through a geography degree, and then seeking to apply this or find a career related to it, people’s background could play a role in their motivation to become a planner, and thus shape their professional mission. An example here would be Planner 18, who had grown-up in an outer suburban neighbourhood in the USA ‘and as a teenager, just got incredibly frustrated at having to be driven or drive everywhere’ then realising ‘you didn’t have to live that way’ and wanting to work to promote a more sustainable built environment through her work as a senior local government official in the UK. In other cases, it might be a personal interest, such as a liking for a particular approach to architecture or a passion for cycling, for example.

The sense of mission could sometimes itself shape careers, as became obvious in relation to some of the moves some planners had made between jobs (illustrated in the timelines on ). For example, four of our seven planners who had worked in both public and private sectors had some initial experience working in local government, then had moved to the private sector before returning to the public sector. All had moved to the private sector initially for reasons of career development, such as better provision of mentoring to support professional chartership, funding for a master’s degree, or seemingly improved job prospects. All four had left because of a sense of their work challenging their sense of ethics and notions of being a ‘good planner’ related to securing not diminishing the public benefit. Planner 21 most clearly articulated this, explaining that ‘every day at [name of private consultancy] felt like a week or a month. I really struggle with the private sector side of planning, it challenged my ethics … you can’t, can’t push back on the quality or anything to make the scheme better’. Similarly, Planner 20 had ‘just wanted to get back to local government … it’s just those small differences that make places better’. Planner 4 was adamant that ‘there is a whole bunch of consultancies out there that we would call the anti-planners that are not bothered about any of the public interest or whatever and are out there just to get money’. Such feelings contrasted with literature that suggested that UK private sector planning was a much better place to make a difference (Vigar, Citation2012; Sturzaker & Hickman, Citationthis issue). We cannot say that these four narrated experiences are in any way representative of the wider profession. It is also important to note a variety of organisational cultures across public and private sectors, and similar things, of a lack of influence and a stifling political culture, were also said of local government. Overall, however, this is illustrative of how employees did sometimes choose the ‘exit’ (Hirschman, Citation1970; Jackson, Citation2020) when an organisation’s values did not seem to accord with their own and their sense of planning’s mission.

Other career moves across our biographies were, however, much more prosaic such as wanting to live in a particular part of the country, a partner’s job moving or simply for promotion. Despite some evidence of cross-sectoral hybridity, and even when moves are for more prosaic reasons, it is striking from the timelines in that our data are suggestive of planning careers in the UK still tending to be primarily public sector or private sector rather than an equal or balanced mix of the two, suggesting a notion of sector fit is still an important consideration (albeit, as already discussed, this must be considered alongside broader organisational fit given diversity within both sectors).

We now turn to consider four particular planners from this wider set in more detail. These were selected on the basis that they illustrate a variety of guiding ‘missions’, some more radical, others more market-oriented and technocratic. There were undoubtedly within our dataset some ‘chameleons’, and certainly some planners with very little sense of being a mission beyond a weakly articulated version of their organisation’s objectives, or a vague notion of ‘better outcomes’, however, there was some sense of ‘mission’ present in most of our biographical interviews. The four selected allow the opportunity to explore four contrasting and fairly clearly articulate ‘missions’, which each appeared in part in several of our wider set of interviews. There is no basis for making claims as to how representative these might be of the wider planning profession in the UK, but the four do cut across public and private sector experience, gender, career length and seniority. There did not appear to be any particularly strong correlation between any of these characteristics and the sense of being on a ‘mission’ in our dataset; perhaps broader socio-political contexts can influence widely regardless of these characteristics but being interpreted via personal experience and values as well as common understandings of the profession (a sense of planning as about ‘delivering development’ was very common, for example).

Planner 14: the delivery state mission

Planner 14 is a senior officer in local government with responsibility for planning, housing and regeneration. They entered the planning profession in the 1980s via a planning degree having had little idea what they wanted to do for a job after school but having liked geography. They started working in local government near to where they grew-up, initially in policy but then development control because they thought this would be more exciting work. There were few prospects for promotion within the council, so they moved to a different part of the country both for a promotion but also to experience living in a different place within an environment that they liked. Planner 14 was then promoted through various positions, often because of local government reorganisation.

Planner 14 is passionate about planning, having spent their own time over the years engaging outside paid work with the Town and Country Planning Association and going on study trips to learn more about different approaches to planning. They commented that ‘planning is at the heart of European prosperity over a number of years, in truth. If you look at the origins of planning in terms of trying to get rid of slum conditions for people … I think, as a profession, in some ways, it’s a noble thing … it seems to me it’s got a fundamental and public purpose.’ This public purpose is ‘all about the public interest’ which is something that ‘you can hide behind or you actually serve’.

There was a strong sense of being on a mission, and in this case that was about an interventionist local state delivering good development to benefit local communities. They explained that where they work ‘the council, happily, have moved to a very interventionist approach, so it sees the local plan as where we need to go in terms of growth and it’s decided that it’s going to take an interventionist approach to achieve those things, not just leave it to the market’. This involves the council borrowing from the Public Works Loans Board, buying land and being a master developer. This responds to some perceived failures in market delivery in the area including fragmented piecemeal development, low-quality housing and insufficient affordable housing for local needs.

Planner 14 is thus consciously working and seeking to work beyond narrower regulatory conceptions of planning common in the UK, commenting that a council restructure at one point in their career had led to them having responsibility for economic development and housing as well as planning, and led to them starting ‘to see the way in which planning wasn’t just about development control, it was about the whole picture, so it was good grounding in understanding that things that councils do as a whole, in a sense, are planning, it’s about making your places better … it was about seeing the objectives of the council and understanding how best you can turn around the organisation towards them and actually planning had a very key role’. They were pleased that planning had gone from being marginalised in the council to being at the heart of delivering corporate objectives developed with and for the local community.

Planner 14’s delivery-focussed mission defined planning as ‘deciding how places should grow and how you take the whole community with you and provide for everybody’s needs … the big picture stuff to create new places and build communities’, Planner 14 responded to the way that promotion through their career had given them more acting space than a more junior planner. Yet they also felt that ‘you are shaped by your organisation’ and that they had consciously remained in the public sector, liking ‘the idea of it serving the public’. This did not mean they felt that the private sector could not be somewhere you could have a positive impact, but they concluded ‘I suppose I’m lucky because I’ve been able to progress and have ambition within the public sector, so it’s served my needs in terms of ambition as well.’ Throughout this biographical interview there was a strong sense of optimism about the role that planning could play, that more interventionist planning did not just have to be the preserve of continental Europe, but also an awareness of some challenges and constraints of government planning reforms. There was a sense of someone who was an ‘institutional entrepreneur’ (Lowndes, Citation2005) able to make use of opportunities such as organisational restructures and local government reform to seek to achieve their objectives of seeing higher quality housing and better infrastructure delivery to meet local needs.

Planner 15: the sustainability, evidence and ethics mission

Planner 15 is a senior consultant in a large multi-disciplinary private sector consultancy. They studied geography at university in the 1970s and had work experience over the summer holidays in local government planning. They grew-up in a post-war expanded town with parents who both worked for the public sector, which they felt had promoted an interest in the built environment and social value. They started working in local government in the 1970s but felt that the 1974 restructure of local government had led to lots of new appointments and so someone joining after that would be unlikely to get promotion soon, so moved to a central government agency. Having worked with private consultants at some public inquiries they then decided to move to the consultancy sector, where concerns about the ethics of one partner prompted a move to another consultancy.

Planner 15 radiated enthusiasm for planning. They had given-up their own time to support the work of the Royal Town Planning Institute and mentor new entrants to the profession to try and share their years of experience. They linked the purpose of planning to sustainability and saw the importance of it, explaining ‘so if you look out the window on your next flight, if you’re going over somewhere that doesn’t have strong planning and you see that sprawl and you wonder how on earth older people manage when they can no longer drive or how you reduce emissions when everyone is car borne or how you keep up social/public facilities when you haven’t got nucleated settlements and everybody’s facing austerity and wanting low taxes, how on earth do you keep any public services going, then maybe we’re not in quite such a bad position and that would be one of my purposes of planning, to avoid those excesses.’ Despite much mention of sustainable development there was an acknowledgement that ‘in consultancy, you’re defined by your projects’ and discussion of some projects which had not promoted environmental sustainability but had led to the creation of job opportunities, a reflection perhaps of the compromises of professional life in a revenue-earning role and the emptiness of the term sustainability in planning.

There was a strong sense from Planner 15 that good planning required robust evidence and analysis and understanding of that data. They were concerned that under austerity the ‘social side of planning’ had gotten submerged, and that many planning reforms since 2010 were not good, based on ‘abominable arguments’ rather than a positive planning system ‘making people’s lives more comfortable’. They expressed concern that ‘regretfully, we’ve lost many of the tools that we had and financial resources that we’ve had in the past, to be very effective’. Although they had primarily worked in the private sector, Planner 15 was very ‘depressed about the regulatory side’ of planning and ‘worried about capacity in the public sector’. They felt that talent ‘has been sucked into the private sector over the course of the last 20 years or so, … to the detriment of the whole planning system’ and that underfunded local authorities lacked capacity to properly analyse evidence or understand the local context and be able to work for ‘the best interests of a local area’.

As well as concerns with promoting evidence-based planning there was a further ethical dimension to Planning 15’s mission. They explained how that at the consultancy they worked at in the 1980s, ‘it was the height of the property boom and [one of the partners] wanted to go off and play property, I think he thought he could make more money more quickly. There were a couple of times when he tried to mix his property interests with his professional consultancy which I strongly disagreed with … so I knew it was time to do something’. Planner 15 thus deliberately changed to an organisation where they ‘felt very much at home with the way they did things’.

They explained that ‘it sounds high minded, but throughout my career, we’ve turned down several juicy, private developer commissions who have made it quite plain that they want to smash their way through local authority policy … and if we disagree with what they’re trying to do, then we don’t take the commission in the first place.’ They had ‘stood up to individual clients who have tried to twist your findings, tried to re-write an environmental impact assessment’ but expressed concern that ‘Unfortunately, I think there are some planning consultants who may not take quite that strong a line. There are some who are certainly working for speculative land finders’ and that there was now an approach of land speculation and volume housebuilding which squeezed out social benefit and that ‘there are elements of that sort of ecosystem that perhaps haven’t got the same scruples that some of us still believe in’. Nevertheless, they were optimistic, concluding ‘I’ve lived through lots of different forms of planning, planning’s been on and off the agenda and can therefore help to keep people going through the bad times because you know that the tide will turn.’

Planner 1: the community focussed mission

Planner 1 also followed the route of a geography degree then going into planning in the 1980s. They had been made aware of the possibilities of planning as a career as a planner lived next door to one of their relatives when they grew-up. After graduation they worked as a local government technician, then undertook a part-time postgraduate planning qualification on ‘day release’ and moved through various local government planning roles. This included moving local authorities to relocate to get married, moving from development control to policy to gain more experience and moves due to local government reorganisation. Job change also included getting promoted and there was acknowledgement when discussing one of their role changes that ‘it’s less, I suppose, a career move out of intention to change the world, it’s more a career move out of trying to get paid more … [but] … it’s not entirely financially motivated because I enjoyed the work.’ This is a reminder of the everyday considerations that can shape careers in planning as much as any other sector: it’s unlikely to be entirely about mission or value as much as keeping in employment and paying a mortgage in many cases.

Planner 1 reflected how, before their current role, ‘the time that I enjoyed most was probably at [Council name]… There was a feeling that we were doing the right thing and we were doing it to the best of our abilities, and it was worthwhile, and it was also fun because of the people I was working with’, whereas at the next Council they moved to work was ‘very frustrating, almost like going to some backwater, where it seemed that nobody had any particular concept of what planning was about really.’ They linked their enjoyment of the first role to having a ‘very knowledgeable’ boss who raised ‘the profile of the planning service, so that it was very much one of the most important services that they had at the council’.

In terms of a sense of mission, Planner 1 felt that of all the government reforms they’d seen over their long career in planning, ‘the one, big change in terms of legislation that’s affected me has been the Localism Act which changed things completely, I think’ and that ‘the most enjoyable work that I’ve done has been on neighbourhood planning’. There was a sense from the biographical interview that giving greater voice to communities in the planning system was the mission that Planner 1 had waited most of their career for before accidently happening on it (they took the role because it had a clear revenue stream when austerity was leading to job losses).

Prior to the introduction of neighbourhood planning, Planner 1 discussed that they had become increasingly depressed about planning because of the slow erosion over time of the ‘control that I think planning has, generally, over what actually gets built and what that stuff looks like. I think we try … to talk about influencing design and promoting good design, but at the same time, I don’t see many examples of good design coming out, particularly in residential developments and new housing estates’. These concerns had not diminished, and they continued to lack faith ‘in volume housebuilders as organisations that can shape the world in a good way’. However, they saw a glimmer of hope in the opportunities provided by neighbourhood planning: ‘I think it’s more about me than what the plan perhaps does, it’s about how I learnt to write planning policies and understand, or try to understand at least what people want to achieve and then, hopefully, draft something, create something which will stand up to scrutiny and actually work when it comes to making a decision’. Planner 1 discussed the way in which they ‘believe, very strongly, in community involvement … but I think it can work and it can help. It’s just getting people involved in planning and thinking about what they want, thinking about what they would like the world to look like I think is a useful change’.

This passion at times brought them into conflict with some of their colleagues: ‘a lot of officers still want to take the old approach which is “we know best”’ whereas he felt planning didn’t need its jargon and should be turned on its head to put community wishes first. Planner 1 didn’t ‘feel constrained in any way, whether it’s by political masters or by managers, [I] kind of try and say what I think is the right thing to do, so I think that’s me looking to act in the public interest.’ Instead, they were motivated by doing what they saw as the right thing for communities, rather than for their employer linking back to an idea that planning ‘should generally be about making people’s lives better, bearable even’.

Planner 1 had clearly found a niche they liked and did not feel they would ‘fit’ in the private sector. They were ‘a lot more cynical’ about the difference planning could make than when they had started their career but still felt a sense of being motivated by a purpose of ‘trying to make a difference … to people’s living environment … deliver what people need to live decent lives’. They typically spent evenings working with parish councils and neighbourhood forums and being the ‘good guys of the planning department going out and selling the fact that the council is here to help you, unlike in every other sphere of life’.

Planner 23: the public service mission

Planner 23 had also been interested in geography at school and took an undergraduate degree in it. They then started working as an ‘agency planner’, doing work for local authority planning departments in London. A perceived lack of career progression and support for a postgraduate qualification led them to a job as an in-house planner for a national retail organisation, seeking to gain them planning permission for their own needs and object to planning applications from business rivals. A company merger led to redundancy and career re-evaluation, and as they explained, ‘I thought I’d just go back to protecting our residents back in lovely, local government … so it was that feeling of I’m back on the good side’.

Planner 23’s mission was one of securing public benefit through regulating private sector developers, perhaps the classic public sector planner role. Their career had not always been shaped by this mission, early in their career when they were unable to secure a permanent position or support for their postgraduate education through their agency work: ‘people asked why I was going into the private sector and I said “well, they’re willing to pay for my masters and that is something that I want to do and I don’t have the money to pay for it myself”’ but it apparently did feel that doing this ‘for my own, personal gain’ was a bit like turning ‘my back on the public sector’. The redundancy in the private sector then meant that ‘the job security, it disappeared out of the window, overnight … and then I came back to the public sector… “I’ve been made redundant, and I have bills to pay. Please, can I have a job?”’

Whilst these moves were clearly driven by personal circumstance, there was a sense of better organisational fit in local government: ‘so it was that feeling of I’m back on the good side, trying to protect residents.’ This mission for public benefit was about being strong with private developers who ‘just want their company to make more money and we’re trying to get the most money out of the developers to benefit the residents’. This public benefit could be secured by being strong and refusing planning permission without adequate affordable housing and negotiating improvements over things like public green space and street trees. Planner 23 felt residents might be unaware of this important role for planning: ‘they’re not in the meetings where we’re trying really hard to get the best benefits for them’, weighing-up the impact of schemes with other considerations such as planning gain. But they felt their role was to explain this to them and point out the difficulties and opportunities the council had in resisting development and securing community benefits.

Interestingly, although a younger planner, Planner 23 thus had traditional values concerning public service and place attachment. They described working in one of the most multi-cultural boroughs in London and taking time to assist residents whose first language was not English to understand the planning process. Their own minority ethnic background seemed relevant to this. They also described the feeling of having made a positive difference which could come from working on smaller planning applications: ‘you have to enjoy what you do, you have to enjoy where you’re going and enjoy the people that you work with and feel that you’re making a difference, even if it is a single storey rear extension. When you go to the site and they say their grandma’s ill and she can’t go up the stairs anymore, they need that extension … and then you approve it and you’ve made a difference to them, even if it’s just one family … it’s still important.’ They also described taking time to understand the place they worked and the impacts from different schemes and developments interacting over time, so being able to make a difference through both understanding technical planning processes but also a place and its community. Planner 23 thus established a justice-based missions in Hillier’s terms, discovering their mission through work practices.

Conclusions: making a difference with limited acting space

The four individual biographical interviewees we have considered in this paper are illustrative of the way a sense of a progressive ‘mission’ is still a motivating factor for some planning practitioners in the UK, with those missions involving a range of issues and goals such as utilising different tools to deliver development seen as beneficial, supporting sustainability, and helping communities. For individual planners, the degree of acting space, and the ability to use this to affect change, will clearly vary according to career stage, individual circumstance and organisational focus, culture and priorities. Looking across all our biographical interviews, the significance of neoliberal, market orientations deepened by a decade of deregulation (most pronounced in England)Footnote3 and by local government cuts to planning services is clear. This has led to greater ‘box-ticking’ and almost universally less time for reflection. These factors diminish the opportunity to pursue progressive planning ideals. Nevertheless, as illustrated by our four examples in this paper, a mildly progressive orientation within the planning profession is still observable, underpinned by a degree of value confluence among planners, as suggested by the literature on epistemic communities, professions, and previous research in planning.

The progressive tendencies among planners are usefully distinguished between common-good and justice-based motivations. Common-good motivations are most prevalent and reflected in planners reaching for the ‘public interest’ justification to explain, however poorly, what they are trying to achieve (Campbell & Marshall, Citation2002). The actions in support of such motivation are often pragmatic, nudging and negotiating better outcomes in discussions with clients and developers. Across our wider set of 23 biographical interviewees, this was the most commonly expressed form of progressive motivation. As such almost all UK planning appears incremental to varying degrees, very rarely radical, although one of our interviewed planners’ work could be described thus and he worked in the private sector in a community-focused niche.Footnote4 Justice-based motivations for planners emerged in relation to working directly with communities most commonly. This could be a deliberate career choice pursued within the public or private sector. Such planners saw their primary orientation as to work for communities, sometimes as clients, rather than their employer. In the case of planner 23 above this ‘mission’ was accomplished through the development management system.

Others might see their work as ‘missionary’, acting for clients to build more housing to satisfy a perceived need, but how far the realities of such work would stand up to close scrutiny of purported value-orientation is moot (Vigar, Citation2012). Sometimes such actions weren’t much reflected upon and in this, professional bodies and others could do much to continually remind planners of the bigger issues potentially at stake within planning including the various overlapping crises of poverty, injustice, biodiversity, climate change and health and wellbeing. All too often planners seem to have become trapped in narrow working practices and organisational and professional norms. Resource pressures give them little opportunity to step back and see the bigger picture.

Where do the more progressive motivations come from for planners? Missions can have multiple roots, from geography and planning degrees, and the motivation to pursue these in the first place, in childhood and family influence, to liking particular places and local environments. Missions also emerged from being in practice, sometimes coupling with these earlier experiences. The nurturing of a mission benefits from a good mentor who can affirm that such motivations are good to pursue (Jackson, Citation2020). Such mentoring relies on organisational cultures oriented to learning, the existence of which depends on committed managers and leadership which includes welcoming argument and dissent (Schoneboom, Citation2023). In many cases, it seemed progressive orientations were stumbled upon during their career rather than chosen from the outset.Footnote5 In local government, the dominance of managerialist practices and the effects of huge cuts to local planning services have led to work intensification, which makes us apprehensive that such cultures can thrive as they once may have. Indeed, managing the extensification of planning work, the increased complexity due to more processes loaded into planning systems, has created difficult working conditions in both sectors (Parker et al., Citation2018).

Where progressive motivations were lacking, the ‘chameleons’ in the broader set of interviewees in our study, what were the motivations/constraints that lead one to being a chameleon? Hillier (Citation2002) notes that chameleon-like behaviour results from practical reasons such as the desire to maintain a salaried job, alongside other constraints such as family commitments to a particular job location for example. We found evidence of this with planners staying in jobs they did not enjoy for longer than they otherwise would. We also confirm the findings of Howe (Citation1994, p. 174) in that a small minority of planners had very little ethical compass at all, which resulted less from a cynical position or from working in a corrupt context, but more from a lack of reflectivity about why they were performing particular tasks. They appeared to have lost sight of what ends they were trying to achieve. Likely all planners at some point in their career/lifecourse will take the chameleon path constrained in their ability to find voice or take the exit (see Wilson, Citation2018, Chapter 7).

‘Exit’ was a strategy often exercised as planners moved organisations to find the right fit. Planners often moved for promotion or to fit with a partner’s employment location. But in many cases, they moved to find an organisation where their values or practices squared more with their employers; with clear evidence of planners actively changing employer in pursuit of ‘acting space’ to pursue their mission. Indeed, the culture and values of the employing organisation was a stronger explanatory variable in terms of planner’s value orientations than the public/private distinction (albeit that still held meaning for many of the planners interviewed), with progressive consultancies redlining certain firms or even whole sectors, while some local authorities gave their planners little say in anything strategic (see also Vigar, Citation2012). Rather the public/private division provided a further level of complexity in matching personal and organisational values with knowledge and skillsets. An interesting trend in this regard relates to the emergence in recent years of large, often publicly-traded, multi-national professional services companies. Such firms have tended to grow by taking over existing smaller firms. Our interviewees noted that this would mean more bureaucracy, less acting space, a prioritisation of profits to the exclusion of ‘good’ planning, and less actual planning work and so often left (see Linovski, Citation2023 for similar findings). Some then started their own consultancies to pursue their ‘mission’ in late career where guaranteed income was less important, and quality of life more important. In self-employment they were unencumbered by imposed corporate goals.

Overall, the degree to which our planners were able to pursue a ‘mission’ depended on the organisational value orientation (there being more or less progressive organisations in public and private sectors) and the degree to which the individual could carve out a niche to pursue their mission (which might depend on particular role focus or seniority). The nature of the mission itself might be influenced by the circumstances of the individual (such as their upbringing, education or work experience) as well as the sector they worked in (in our study, the weakest sense or articulation of any mission were from planners working in the private sector in non-progressive consultancies, yet a public/private binary is insufficient to understand the nature, extent and acting space for any mission). There can, however, clearly be chameleons in all sectors and organisations: just as some planners in our study had clearly moved to pursue a mission, others had not, and some probably never would.

Understanding the degree to which planners can, and are, pursuing any sort of progressive mission involves close study of motivations and practices: planning is a peopled profession and life histories, and everyday experiences of planners relate to how planning is performed, by whom and to what ends (Clifford, Citation2022). We therefore finish by arguing for the value of biographical interviewing in planning research and advocate for more work in this area. Our research focussed on fairly mainstream public and private planners who were known to us. It is likely that this creates a particular sample (see also Jackson, Citation2020). Further research focusing on planners ‘at the margins’, particularly in the voluntary sector and in niches of the private sector such as those with more market fundamentalist underpinnings, to see how they conceive of their work and justify its outcomes, would be significant (see Zanotto, Citation2019). Comparisons to other professions subject to market logics and commercialisation processes such as law, would also be fruitful (see Faulconbridge & Muzio, Citation2009).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the research participants of the ESRC funded Working in the Public Interest project and our fellow researchers: Zan Gunn, Andy Inch, Abby Schoneboom, Jason Slade, and Malcolm Tait. Three anonymous referees provide valuable comments on an earlier draft.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. in the Anglo-Saxon world at least, and we note here a dominance of work in this area from such contexts which we are mindful of perpetuating.

2. By progressive we mean, ‘decision-making on the basis of whether a decision increases flourishing or equity’ (McClymont, Citation2014, p. 188), as opposed to merely oiling the wheels of capitalism, see also Zanotto (Citation2019).

3. Planning is a devolved function in the UK, so reforms of the planning system vary between England, Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales.

4. Most of their work involved using the tools of the state – neighbourhood planning, parish planning – and so wasn’t a pure form of radical planning but they frequently co-designed new practices with communities that effectively challenged planning orthodoxies. This was in part-contrast with Planner 1, working within local government using the same technologies, who also saw their role as serving citizens, not their employer, but more within existing frameworks, bending them where they could to meet community objectives.

5. A phenomenon noted in other professions (see Suddaby et al. (Citation2007)). Historically in (US) planning see Howe (Citation1980).

References

- Allmendinger, P. (1996) Development control and the legitimacy of planning decisions: A comment, The Town Planning Review, 67(2), pp. 229–233. doi:10.3828/tpr.67.2.x630579742276448.

- Allmendinger, P., & Tewdwr-Jones, M. (2002) The communicative turn in urban planning: Unravelling paradigmatic, imperialistic and moralistic dimensions, Space and Polity, 6(1), pp. 5–24. doi:10.1080/13562570220137871.

- Barclay, S., & Marshall, A.-M. (2005) Supporting a cause, developing a movement, and consolidating a practice: Cause lawyers and sexual orientation litigation in Vermont, in: A. Sarat & S. A. Scheingold (Eds) The Worlds Cause Lawyers Make: Structure and Agency in Legal Practice, pp. 171–202 (Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press).

- Campbell, H., & Marshall, R. (2002) Utilitarianism’s bad breath? A re-evaluation of the public interest justification for planning, Planning Theory, 1(2), pp. 163–187. doi:10.1177/147309520200100205.

- Campbell, H., Tait, M., & Watkins, C. (2014) Is there space for better planning in a neoliberal world? Implications for planning practice and theory, Journal of Planning Education and Research, 34(1), pp. 45–59. doi:10.1177/0739456X13514614.

- Chamberlayne, P., Bornat, J., & Wengraf, T. (Eds). (2000) The Turn to Biographical Methods in Social Science (London: Routledge).

- Clifford, B. (2018) Charting outsourcing in UK public planning. Available at https://drive.google.com/file/d/14NVyj-O4yxVIlwsullq-6wQVmAFnkBTV/view.

- Clifford, B. (2020) Planning ethics: The need for a ‘do no harm’ principle to help secure the public interest? Available at https://witpi.sites.sheffield.ac.uk/research/planners/planning-ethics.

- Clifford, B. (2022) British local authority planners, planning reform and everyday practices within the state, Public Policy and Administration, 37(1), pp. 84–104. doi:10.1177/0952076720904995.

- Clifford, B., Inch, A., Slade, J., Tait, M., Gunn, S., Schoneboom, A., & Vigar, G. (2020). WITPI Planner pen portraits. Available at https://drive.google.com/file/d/1lyaBO8rJUrkYPZ6EO0woRkDO1R-GqoS7/view.

- Clifford, B., & Tewdwr-Jones, M. (2013) The Collaborating Planner: Practitioners in the Neoliberal Age (Bristol: Policy Press).

- Denzin, N. K. (2011) Interpretative Guidelines. Chapter 46. in: R. Miller (Ed) Biographical Research Methods: Volume IV, pp. 73–88 (London: Sage).

- Faulconbridge, J. R., & Muzio, D. (2009) The financialization of large law firms: Situated discourses and practices of reorganization, Journal of Economic Geography, 9(5), pp. 641–661. doi:10.1093/jeg/lbp038.

- Ferm, J., & Raco, M. (2020) Viability planning, value capture and the geographies of market-led planning reform in England, Planning Theory & Practice, 21(2), pp. 218–235. doi:10.1080/14649357.2020.1754446.

- Fox-Rogers, L., & Murphy, E. (2016) Self-perceptions of the role of the planner, Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design, 43(1), pp. 74–92. doi:10.1177/0265813515603860.

- Grange, K. (2013) Shaping acting space: In search of a new political awareness among local authority planners, Planning Theory, 12(3), pp. 225–243. doi:10.1177/1473095212459740.

- Grange, K. (2017) Planners – A silenced profession? The politicisation of planning and the need for fearless speech, Planning Theory, 16(3), pp. 275–295. doi:10.1177/1473095215626465.

- Gunn, S., & Vigar, G. (2012) Reform processes and discretionary acting space in English planning practice, 1997–2010, Town Planning Review, 83(5), pp. 533–553. doi:10.3828/tpr.2012.33.

- Harris, N., & Thomas, H. (2011) Clients, customers and consumers: A framework for exploring the user-experience of the planning service, Planning Theory & Practice, 12(2), pp. 249–268. doi:10.1080/14649357.2011.580157.

- Harvey, D. (1985) The Urbanisation of Capital (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press).

- Hendler, S., & Bickenbach, J. E. (1994) The moral mandate of the ‘profession’ of planning. in: H. Thomas (Ed) Values and Planning, pp. 162–177 (London: Routledge).

- Hillier, J. (2002) Shadows of Power: An Allegory of Prudence in Land-Use Planning (London: Routledge).

- Hirschman, A. O. (1970) Exit, Voice, and Loyalty: Responses to Decline in Firms, Organizations, and States (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press).

- Howe, E. (1980) Role choices of urban planners, Journal of the American Planning Association, 46(4), pp. 398–409. doi:10.1080/01944368008977072.

- Howe, E. (1994) Acting on Ethics in City Planning (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press).

- Jackson, J. (2020) What do mid-career Melbourne planners profess? International Planning Studies, 25(4), pp. 393–408. doi:10.1080/13563475.2019.1626702.

- Kitchen, T. (1997) People, Politics, Policies and Plans: The City Planning Process in Contemporary Britain (Basingstoke, Palgrave: SAGE).

- Kohli, M. (2011) Biography: Account, text, method. Chapter 45. in: R. Miller (Ed) Biographical Research Methods: Vol. IV, pp. 59–72 (London: Sage).

- Lauria, M., & Long, M. (2017) Planning experience and planners’ ethics, Journal of the American Planning Association, 83(2), pp. 202–220. doi:10.1080/01944363.2017.1286946.

- Lewis, D. (2008) Using life histories in social policy research: The case of third sector/public sector boundary crossing, Journal of Social Policy, 37(4), pp. 559–578. doi:10.1017/S0047279408002213.

- Linovski. (2023) Planners in publicly traded firms, Journal of the American Planning Association, 89(3), pp. 376–388. doi:10.1080/01944363.2022.2093259.

- Linovski, O. (2019) Shifting agendas: Private consultants and public planning policy, Urban Affairs Review, 55(6), pp. 1666–1701. doi:10.1177/1078087417752475.

- Loh, C. G., & Arroyo, R. L. (2017) Special ethical considerations for planners in private practice, Journal of the American Planning Association, 83(2), pp. 168–179. doi:10.1080/01944363.2017.1286945.

- Loh, C. G., & Norton, R. K. (2013) Planning consultants and local planning, Journal of the American Planning Association, 79(2), pp. 138–147. doi:10.1080/01944363.2013.883251.

- Lowndes, V. (2005) Something old, something new, something borrowed … how institutions change (and stay the same) in local governance, Policy Studies, 26(3–4), pp. 291–309. doi:10.1080/01442870500198361.

- McClymont, K. (2014) Stuck in the process, facilitating nothing? Justice, capabilities and planning for value-led outcomes, Planning Practice and Research, 29(2), pp. 187–201. doi:10.1080/02697459.2013.872899.

- Nelson, S., & Neil, R. (2021) Early career planners in a neo-liberal age: Experience of working in the South East of England, Planning Practice & Research, 36(4), pp. 442–455. doi:10.1080/02697459.2020.1867777.

- Othengrafen, F. (2014) The concept of planning culture: Analysing how planners construct practical judgements in a culturised context, International Journal of E-Planning Research (IJEPR), 3(2), pp. 1–17. doi:10.4018/ijepr.2014040101.

- Parker, G., Street, E., & Wargent, M. (2018) The rise of the private sector in fragmentary planning in England, Planning Theory & Practice, 19(5), pp. 734–750. doi:10.1080/14649357.2018.1532529.

- Raco, M. (2018) Private consultants, planning reform and the marketisation of local government finance. in: J. Ferm & J. Tomaney (Eds) Planning Practice: Critical Perspectives from the UK, pp. 123–137 (NYC: Routledge).

- Reade, E. (1987) British Town and Country Planning (Milton Keynes: Open University Press).

- Rosenthal, G. (2004) Biographical research, chapter 45. in: C. Seale, G. Gobo, J. Gubrium, & D. Silverman (Eds) Qualitative Research Practice, pp. 48–64 (London: Sage).

- Rustin, M. (2000) Reflections on the biographical turn in social science. in: P. Chamberlayne (Ed) The Turn to Biographical Methods in Social Science: Comparative Issues and Examples, pp. 33–52 (London: Routledge).

- Sanyal, B., (Ed). (2005) Comparative Planning Cultures (NYC: Routledge).

- Schoneboom, A. (2023) What Town Planners Do (Bristol: Policy Press).

- Slade, D., Gunn, S., & Schoneboom, A. (2019). Serving the public interest? The reorganisation of UK planning services in an era of reluctant outsourcing. Available at https://www.rtpi.org.uk/media/2005/servingthepublicinterest2019.pdf.

- Steele, W. (2009) Australian urban planners: Hybrid roles and professional dilemmas? Urban Policy and Research, 27(2), pp. 189–203. doi:10.1080/08111140902908873.

- Sturzaker, J., & Hickman, H. this issue. Profit or public service? PPR

- Suddaby, R., Cooper, D. J., & Greenwood, R. (2007) Transnational regulation of professional services: Governance dynamics of field level organizational change, Accounting, Organizations & Society, 32(4), pp. 333–362. doi:10.1016/j.aos.2006.08.002.

- Valler, D., & Phelps, N. A. (2018) Framing the future: On local planning cultures and legacies, Planning Theory & Practice, 19(5), pp. 698–716. doi:10.1080/14649357.2018.1537448.

- Vigar, G. (2012) Planning and professionalism: Knowledge, judgement and expertise in English planning, Planning Theory, 11(4), pp. 361–378. doi:10.1177/1473095212439993.

- Wilson, R. (2018) A Guide for the Idealist: Launching and Navigating Your Planning Career (NYC: Routledge).

- Zanotto, J. M. (2019) Detachment in planning practice, Planning Theory & Practice, 20(1), pp. 37–52. doi:10.1080/14649357.2018.1560491.