ABSTRACT

Objective

The aim of this scoping review was to identify behavioral disturbances exhibited by patients in post-traumatic amnesia (PTA). While behavioral disturbances are common in PTA, research into their presentation and standardized measures for their assessment are limited.

Design

The study protocol was registered with PROSPERO (CRD42021268275). A scoping review of databases was performed according to pre-determined criteria on 29 July 2021 and updated on 13 July 2022. A conventional content analysis was used to examine and categorize behavioral disturbances.

Results

Thirty papers met the inclusion criteria, of which 27 reported observations and/or scores obtained on behavioral scales, and 3 on clinician interviews and surveys. None focused exclusively on children. Agitation was the most frequently assessed behavior, and Agitated Behavior Scale was the most used instrument. Content analysis, however, bore eight broad behavioral categories: disinhibition, agitation, aggression, lability, lethargy/low mood, perceptual disturbances/psychotic symptoms, personality change and sleep disturbances.

Conclusion

Our study revealed that while standardized assessments of behavior of patients in PTA are often limited to agitation, clinical descriptions include a range of behavioral disturbances. Our study highlights a significant gap in the systematic assessment of a wide range of behavioral disturbances observed in PTA.

Introduction

Post-traumatic amnesia (PTA) has been defined as a period of recovery following traumatic brain injury (TBI), after a patient wakes from coma, where a patient is ‘confused, amnesic for ongoing events and likely to evidence behavioral disturbance’ (Citation1; p675). PTA is routinely assessed in children and adults with a standardized scale such as the Galveston Orientation Amnesia Test (GOAT; Citation1), Westmead PTA scale (WPTAS; Citation2); and Children’s Orientation and Amnesia Test (COAT; Citation3). PTA scales assess cognitive recovery, namely, orientation and memory.

In contrast, while it has been known for over a century (Citation4) that neurobehavioral disturbances are (i) commonly present during PTA and (ii) interfere with acute rehabilitation, research into their natural history, assessment and prognostic validity has been largely neglected (Citation5).

A small number of studies that did report on behavioral disturbances during PTA have almost exclusively focused on agitation, possibly due to agitation interfering with rehabilitation, limiting patients’ independence and increasing demands on care. A worldwide (n = 34 countries) online survey of clinicians (n = 331) involved in the care of patients in the early stages of recovery from TBI revealed that three quarters of these clinicians evaluated agitation in their services (Citation6). Agitation displayed during PTA has been shown to relate to cognitive functioning. For example, Corrigan (Citation7) found higher agitation among patients with low level cognition and lower agitation among patients with higher level cognition. Hennessy and colleagues (Citation8), however, found that behavioral disturbances during PTA were related to difficulties with attention and concentration (typically not assessed with PTA scales) rather than orientation and memory (typically assessed with PTA scales). Furthermore, inspection of clinical observations reported in the literature has suggested that behavioral disturbances displayed by patients in PTA include but are not limited to agitation. For instance, emotional lability, delusions, impulsiveness, verbal and physical aggression, inappropriate behavior, and regressive personality, are some of the behavioral disturbances reported in the literature (Citation8–10). Recently, and in response to the recognition of behavioral disturbances that often coexist with cognitive impairments in the acute stage of recovery from TBI, it has been suggested that it may be better to use the term post-traumatic confusional state rather than PTA to capture both types of disturbances (Citation11,Citation12).

There is limited research evaluating behavior disturbance during PTA and current standardized measures of PTA neglect to include these relevant behavioral symptoms. This neglect may be related to the challenging and complex nature of PTA. Also, cognitive features like confusion and daily memory disturbance limit administration of self-report questionnaires. Instead, assessments of behavior rely on objective and/or secondary completion of questionnaires by staff or families. There are some exceptions, however, to scales measuring progress of patients in PTA. For example, the Ranchos Los Amigos Scale (Citation11), which maps early stages of cognitive recovery (but does not measure PTA as such), also includes a small number of general behavioral attributes (‘confused,’ ‘agitated,’ ‘appropriate,’ ‘inappropriate,’ ‘purposeful’ or ‘automatic’ (Citation13). The 14-item Agitated Behavior Scale (ABS (Citation14), frequently used in research settings, measures only ‘agitated’ behaviors, asking about observations of inattention, violence, restlessness and perseveration. Recently, Hennessy and colleagues (Citation6) reported on a novel assessment of cognition and behavior in adults who were in PTA. This measure includes a range of frequent behavioral disturbances (found in > 50% of patients) such as Inattention, Sleep Disturbance, Impulsivity, Repetitive Behavior, Daytime Drowsiness, Self-Monitoring, Self-Stimulation, and Restlessness. The scale was to undergo further development. To our knowledge, there are no behavioral scales that have been validated for use with children who are in PTA, although Symonds (Citation15) has pointed out that behavioral disturbances are particularly common in children who are in PTA.

Overall, there is a clear need for a better characterization of the behavioral disturbances experienced by patients in PTA and for the development of a standardized, validated scale for the assessment of these behavioural disturbances. As Marshman articulates, ‘few clinicians would discharge a patient with a maximal PTA score’ as indicated by cognitive measures, ‘but with disabling agitation.’ (Citation5) p.1477) Ideally, the scale would include clearly delineated and categorized symptoms of behavioral disturbances, assist in tracking behavioral recovery, inform approaches to inpatient rehabilitation and help with discharge planning. The primary aim of this Scoping review and content analysis is to detail behavioral disturbances exhibited by patients in PTA reported in the literature to date. We also aim to propose behavioral categories representing these disturbances. A secondary aim is to explore reference to possible correlates and the predictive value of these disturbances for the benefit of future research. We anticipate that findings of the current study could be used to inform development of scales and protocols for evaluation of behavioral disturbances during PTA.

Method

Study framework, protocol and registration

The systematic scoping review methodology (Citation16) met the criteria outlined in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR) Checklist (please refer to the Supplement Digital Content 1 (Citation17). The protocol for this Scoping review was registered with PROSPERO (registration number: CRD42021268275).

Inclusion/Exclusion criteria

Studies included in the review were required to report on (i) participants of any age who had sustained a TBI of any severity, (ii) participants who had experienced PTA, as per standardized PTA scale or clinical observations reporting on patient experiences in PTA, and (iii) clinical observations of behavioral disturbances or performance on a rating scale assessing behavioral disturbances during PTA. Only full-length, original studies published in peer-reviewed journals in the English language were included in the current study. No limits on the date of study publication were imposed. Studies were excluded from the review if (i) there was no reporting of behavior during PTA or (ii) reported behavioral features related to behaviors following rather than during PTA.

Search strategy

The searches were conducted on four databases: (i) PsycINFO (1806 – present), (ii) MEDLINE (1946 – present), (iii) Web of Science (1899 – present) and (iv) Scopus (1788 – present) on 29 July 2021 and updated on 13 July 2022. Searches were designed to include the following concepts: (i) traumatic brain injuries, (ii) PTA and (iii) behavior.

The search terms for PsycINFO were [‘amnesia’ (subject heading and keyword) OR ‘post traumatic amnesia’ (keyword) OR ‘PTA’(keyword)] AND [‘traumatic brain injury’ (subject heading and keyword) OR ‘TBI’ (keyword)] AND [‘behavior’ (subject heading and keyword)]. The search terms for MEDLINE were [‘amnesia’ (subject heading and keyword) OR ‘post traumatic amnesia’ (keyword) OR ‘PTA’(keyword)] AND [‘TBI’ (keyword) OR ‘traumatic brain injuries’ (subject heading and keyword)] AND [‘behavior’ (keyword)]. The search terms for Web of Science were [‘amnesi*’ OR ‘post traumatic amnesia’] AND [‘traumatic brain injur*’ OR ‘TBI’] AND [‘behavior’]. The search terms for Scopus were [‘amnesi*’ OR ‘post traumatic amnesia’] AND [‘traumatic brain injur*’ OR ‘TBI’] AND [‘behavior’]. Keyword searches applied to both the title and abstract of articles.

First, all search results were downloaded to endnote and duplicates were excluded. Second, all titles and abstracts were reviewed independently by two authors (VT, SL) against the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Any discrepancies were discussed until a consensus was reached. Third, full length manuscripts of potentially relevant manuscripts were independently reviewed by the main investigator (VT) and one of the co-investigators, with final selection agreed upon in the group discussion with all authors. Finally, the reference lists of the remaining papers were reviewed to identify relevant papers that had not been retrieved through the electronic searches.

Content analysis: data extraction and synthesis

The data charting process, given the exploratory nature of our investigation, was developed as we became more familiar with the study data (Citation16). A conventional content analysis was used with the aim of categorizing descriptions of a given phenomenon. The conventional content analysis is an inductive approach and considers that categories and names for categories flow from the data in a way that does not just count words, though carefully examines the language used to classify large amounts of information (Citation18). The descriptions of behavior, whether scale items, terms or phrases from clinical observations, were formatted as the units of analysis. These were manually analyzed independently by the main investigators (VT and SL) between the 27 July and 10 August 2022 before contrasting categories and discussing classifications. Charting the data followed the stages outlined below:

Immersion in the data: Independent items from each scale were listed and reviewed repeatedly to obtain a sense of the whole data. In each scale, items were read word by word to derive those capturing key concepts.

Collating terms in categories: Across scales, duplicate words were disregarded and where the same key concepts were being described, these words were grouped, and a broader category was formulated which summarized the common behavior being identified by these descriptors.

Sorting terms into accurate clusters based on how they link to form meaning: Phrases and words used to describe clinical observations of patients in PTA were listed and reviewed repeatedly. The phrases and words were sorted into the broader categories mentioned above. Where they did not fit into existing categories, new broader categories were formulated.

Results

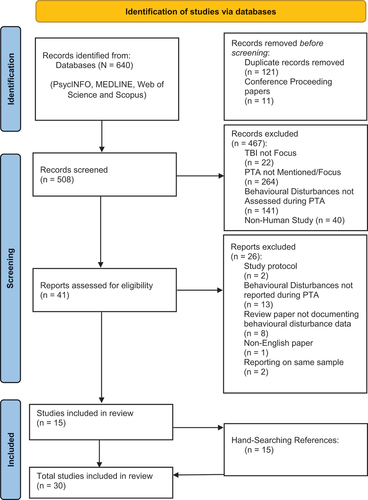

provides an overview of the study selection process. Initial searches yielded a total of 640 articles, of which 132 were excluded (121 of which were duplicates and 11 were conference papers). The abstract review of the remaining 508 papers resulted in the exclusion of 467 studies as they did not meet inclusion criteria. Review of 41 full text manuscripts identified 15 relevant studies. Screening of the manuscript reference list identified 15 additional, potentially relevant studies. Following review, all these additional 15 studies met the inclusion criteria. No papers were excluded because of an inability for reviewers to reach consensus. The total number of papers included in the review was 30.

Figure 1. PRISMA flow diagram.

Demographic and study variables

Across 30 studies, 27 involved health-care workers reporting clinical observations and/or scores as assessed using behavioral scales, the behaviors of patients who sustained TBI and were in PTA. The remaining three reported on interviews and surveys completed by clinicians reflecting on behavioral disturbances displayed by patients in PTA. Of the 27 studies, the sample sizes ranged from 2 to 219. The mean sample size was 63.33 (SD 56.85) and the total sample size was 1710. All but six studies included adults only. The remaining six studies included adults and children, with the youngest participant beginning aged either 0, 12, 13 or 15 at the time of TBI, but extending to patients aged between 58 and 70. Overall, the majority of participants in these studies were adults. The age and gender distribution of participants, where provided by the study, are reported in Tables 2 and 3, Supplemental Digital Contents 2 and 3. These tables also includeinformation on the severity of TBI which was classified as either mild, moderate or severe, as reported by authors.

Reporting on PTA

Of the 30 studies, seven studies administered the GOAT, six studies used the WPTAS and one used the GOAT (Citation1) and WPTAS (Citation2). Another used the WPTAS and the Oxford PTA Scale (Citation9), 2 administered the Orientation Group Monitoring System (OGMS; 7) and the remaining 13 studies verbally reported that their clients were in an acute stage of recovery, having just emerged from coma. On review of these scales, no items were identified that assessed behavior.

Behavioral disturbances in PTA

Two tables summarizing the key features of the 30 studies identified (27 direct reports on patient behavior and three interviews or surveys of healthcare workers) are included in the Supplement Digital Content of this manuscript. Overall, 20 papers used a scale to assess behavioral disturbances (refer Table 2, Supplement Digital Content 2); two included a scale and clinical observations concurrently, and eight reported clinical observations only (refer Table 3, Supplement Digital Content 3). The following scales were used in these studies: Agitated Behavior Scale (ABS; n = 11), Checklist of Neurobehavioral sequelae (n = 1), Post-Traumatic Activity Level (PTAL; n = 1), Overt Aggression Scale (OVS; n = 1), Disability Rating Scale – Revised (DRS-R; n = 1), Confusion Assessment Protocol (CAP; n = 1), Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (n = 1) or the Delirium Rating Scale (DelRS; n = 1). Other measures (n = 5) included behavioral rating scales developed (i) by combining items of the above-mentioned scales, (ii) from review of the literature or (ii) relying on the clinical experience of authors.

The 10 studies that involved clinical observations of behavior for patients in PTA are as follows: case studies (n = 6), semi-structured interviews of healthcare staff (n = 1), and reviews of patient files and healthcare worker notes (n = 3).

Behavioral disturbance categories

Eight behavioral categories were identified via a conventional content analysis and these categories and subcategories, information on how they were reported, and examples are summarized in . While most behavioral categories contained discrete behavioral subcategories, some subcategories were deemed relevant to more than one category. For example, restlessness was described as a feature of disinhibition and restlessness. As summarized in , in order from most to least frequently reported in the literature, the categories included: agitated behavior, disinhibited behavior, lethargy/low mood, aggression, lability, perceptual disturbance/psychotic like symptoms, sleep disturbances and personality changes.

Table 1. Behavioral categories.

Correlates and predictive value of behavioral disturbances

The predictive value of behavioral disturbances explored by the literature has been included in supplementary Tables S2 and S3. For example, patient length of stay, later cognitive, behavioral or physical functioning, mental health, community independence and involvement and treatment outcomes, given the presence or severity of behaviors reported on during PTA.

Discussion

The aim of the current study was to detail behavioral disturbances displayed by patients in PTA following TBI, as reported in the literature. Our scoping review of the literature revealed that (i) assessment of patients in PTA has been dominated by scales evaluating cognitive functions despite behavioral disturbances being recognized for decades (Citation1,Citation4,Citation27,Citation28) (ii) there is a lack of research on behavioral features of children in PTA, and (iii) the range of behavioral disturbances displayed by adults in PTA extends well beyond agitation which is most commonly (but not routinely) assessed.

What first became apparent was the absence of behavioral items in scales used to assess PTA in the studies that were included in our review. All items of the PTA scales employed in papers included in our study, the GOAT (Citation1), WPTAS (Citation2) and OGMS (Citation29), measured only patient orientation and/or memory, which is problematic for two main reasons (Citation5,Citation8). First, this focus on a single domain (i.e., cognition (Citation30) is likely to provide an incomplete picture of patients’ recovery during PTA. Second, while PTA duration is a strong predictor of cognitive outcomes, later independent living skills, self-care and social problems (Citation31), research suggests that PTA duration, as measured by scales that assess cognitive recovery, is not a predictor of behavioral and psychological outcomes following TBI in either adults or children (Citation5,Citation8,Citation32). Papers that explored behaviors during PTA used scales or items (i) from various scales originally intended to measure behavior for other purposes or (ii) that were developed in-house to meet the aims of a particular study. No standardized, validated behavioral scale that assessed a range of behaviors displayed by participants in PTA has been identified.

What also became apparent was that all papers reported on behavioral disturbances among adults. A small number of studies included patients with an extremely varied age range (for example, 0–70+; 33) though had no separate reporting on behavioral disturbances displayed by children. In contrast, early researchers pointed out that behavioral disturbances are reported to be most common in children sustaining TBI, particularly a ‘complete change in character’ (Citation33; p590) or ‘defective moral sense’ (Citation27; p1089). Moreover, the behavioral difficulties manifested by children in PTA may be related to their developmental stage and differ to those displayed by adults, highlighting the need for developmentally appropriate assessment scales of behavior.

Through content analysis, our study revealed that eight broad categories of behavioral disturbances are present in adult patients who are in PTA, namely, disinhibited behavior (C1), agitation (C2), aggression (C3), lability (C4), lethargy/low mood (C5), perceptual disturbances/psychotic like symptoms (C6), personality changes (C7) and sleep disturbances (C8). The behavior most commonly reported, regardless of the papers’ method of investigation, was agitation. Interestingly however, the reported prevalence rates of agitation are highly variable, ranging between 7 and 70% (Citation25). In part, the difference in the reported prevalence rate of agitation may be due to the diversity of definitions and measurement tools used across studies. A preference for assessing and measuring agitation more than other behavioral features could have resulted from the significant interference agitated behaviors cause in patient care; requiring the possible use of restraints, redirection, reorientation and environmental modifications in a hospital setting (Citation34,Citation35). Agitated behavior and aggressive behaviors can be a great burden on healthcare workers, especially nurses, as well as making patients more vulnerable to further harm (Citation24). Among papers using behavioral rating scales, the ABS, which was designed to focus on agitation alone, was used most frequently. On review of the scale, however, its items were found to fit into several other behavioral categories and these behaviors may occur independently of agitation (for example, restlessness, distractibility or impulsivity (Citation6,Citation9). Recently, papers that use the ABS included additional items such as sleep disturbance, day-time arousal, socially inappropriate behavior, confabulation and self-monitoring (Citation8) in recognition of their assessment value to patient care.

Disinhibited behavior was the second most common behavior reported, followed by lethargy/low mood, aggression, lability, perceptual disturbance/psychotic like symptoms, sleep disturbances and finally personality changes. Notably, personality changes were only mentioned in papers reporting clinical observations. One paper described regression in detail as a rarer occurrence in patients who sustained severe TBI (Citation10). Other papers (Citation15,Citation33) made general comments on personality change. Assessment of personality change would be difficult due to the complexity of measuring such a change given it requires knowledge of the patient’s disposition before brain injury and given the relationship between personality change and other categories such as disinhibition and agitation may be complex and difficult to disentangle (Citation15). Nevertheless, including an item on personality change in the assessment of behavior during PTA may be important, as changes in personality are reported among child, adolescent and adult patients who sustain severe TBI, in the chronic stages of recovery (Citation36,Citation37). Moreover, these changes are often particularly distressing and concerning for the family members and caregivers, who report observing such alterations (Citation38).

Though some of the papers investigated the impact of behavioral disturbances on patient care and predictive value of behavioral disturbances during PTA, their findings should be considered preliminary given the high variability in scales and restricted scope of behaviors assessed by these scales. Specifically, agitation and restlessness were reported to interfere with therapeutic interventions (Citation39), though also predict the amount of community support patients may require upon discharge (Citation40), the independence patients can exercise in activities of daily living (Citation8), long-term residual emotional disturbances (Citation41), residual behavioral disturbances (Citation1), social communication impairments (Citation22) and disability (Citation10). Correlates of behavioral disturbances, particularly agitation, were also explored demonstrating the likely strong relationship or interaction between cognitive and behavioral domains of PTA. Lower WPTAS, OGMS or GOAT scores, reflective of poorer orientation and memory have been significantly associated with greater agitation (Citation7,Citation25,Citation42–48). Nevertheless, some instances of improved cognition with continued agitation were also reported. Such a dissociation suggests that behavioral disturbances may be present even when cognitive deficits that characterize PTA resolve (Citation7). Future research may allow a better understanding of how behavioral disturbances during PTA contribute to the severity and duration of possible ongoing difficulties. Notably, the predictive validity of PTA behavioral disturbances, other than agitation, is largely unknown. Finally, future research should consider how pre-existing behavioral and cognitive difficulties may affect a patient’s presentation during PTA to aid assessment and patient care within and outside of the hospital to support their recovery.

While our study showcased novel findings, it is important to recognize its limitations. First, scales evaluating behavioral disturbances during PTA are often limited to specific types of behaviors (i.e., agitation) and as such may not be grasping the range of actual behavioral disturbances manifested by patients in PTA. Second, the findings of our study are restricted to mostly adults and could not be generalized to children and adolescents, as no study has been published reporting specifically on behavioral difficulties of children and adolescents in PTA. Third, it is possible that behavioral disturbances can manifest differently across TBI severities, which could not be examined in the current study as manuscripts typically did not report behavioral findings separately for different TBI severities. Fourth, the findings of the current study were based on behavioral descriptions from published literature rather than from observations of a clinical population. Future studies should seek clinical observations and expert opinions to further clarify and refine our findings. Fifth, it was also not possible to explore the incidence and occurrence of different behavioral disturbances due to difference in measures used and categorization of behaviors across studies. The papers that were included in our study were published over a wide time period from 1904 to 2022. We noticed marked differences in language used to describe behavioral disturbances and in reporting styles across this time. Sixth, current PTA assessment scales reviewed in our study were limited to scales used in papers that met our inclusion criteria and therefore may not reflect all the different PTA assessment scales used in clinical settings.

Our scoping review is, to our knowledge, the first to detail behavioral disturbances exhibited by patients in PTA and categorize these behavioral disturbances. Our qualitative analysis identified eight categories of behavioral disturbances exhibited by patients in PTA reported in the literature. In contrast, assessment of behavioral disturbances was typically limited to agitation. Moreover, our study found no standardized, validated scales developed for assessment of behaviors in PTA, although behavioral disturbances are an integral feature of PTA, impact rehabilitation, and may be long-lasting. Furthermore, this scoping review discovered no studies focussed on behavior of children in PTA, which is alarming as behavioral disturbances are thought to be particularly common in children. Future research should undertake phenomenological investigations of behavioral disturbances and develop standardized measures for assessment of behavior in PTA across the lifespan.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (183.9 KB)Disclosure statement

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare author(s).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/02699052.2024.2304865

Additional information

Funding

References

- Levin H, Oʼdonnell V, Grossman R. The Galveston orientation and amnesia test. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1979;167(11):675–684. doi: 10.1097/00005053-197911000-00004. Cited in: PMID: 501342.

- Shores EA, Marosszeky JE, Sandanam J, Batchelor J. Preliminary validation of a clinical scale for measuring the duration of post‐traumatic amnesia. Med J Of Aust. 1986;144(11):569–72. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1986.tb112311.x. Cited in: PMID: 3713586.

- Ewing-Cobbs L, Levin HS, Fletcher JM, Miner ME, Eisenberg HM. The children’s orientation and amnesia test: relationship to severity of acute head injury and to recovery of memory. Neurosurg. 1990;27(5):683–91. doi: 10.1227/00006123-199011000-00003. Cited in: PMID: 2259396.

- Meyer A. The anatomical facts and clinical varieties of traumatic insanity. Am J Psychiatry. 1904;60(3):373–441. doi: 10.1176/ajp.60.3.373. Cited in : PMID: 10956578.

- Marshman LAG, Jakabek D, Hennessy M, Quirk F, Guazzo EP. Post-traumatic amnesia. J Clin Neurosci. 2013;20(11):1475–1481. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2012.11.022. Cited in: PMID: 23791248.

- Carrier SL, Hicks AJ, Ponsford J, McKay A. Managing Agitation During Early Recovery in Adults with Traumatic Brain Injury: An International Survey. Ann Phys Rehabil. 2021;64(5):101532. doi: 10.1016/j.rehab.2021.101532. Cited in: PMID: 33933690.

- Corrigan JD, Mysiw WJ. Agitation following traumatic head injury: equivocal evidence for a discrete stage of cognitive recovery. Arch Phys Med Rehab. 1988;69(7):487–92. Cited in: PMID: 3389986.

- Hennessy MJ, Delle Baite L, Marshman LAG. More than amnesia: prospective cohort study of an integrated novel assessment of the cognitive and behavioral features of PTA. Brain Impair. 2021;22(3):294–311. doi:10.1017/BrImp.2021.2.

- Weir N, Doig EJ, Fleming JM, Wiemers A, Zemljic C. 2006. Objective and behavioral assessment of the emergence from Post-traumatic amnesia (PTA). Brain Inj. 20(9):927–35. 10.1080/02699050600832684. Cited in: PMID.

- Heled E, Sverdlik A, Agranov E. 2013. Persistent extreme regressive behavior in severe traumatic brain injury patients: a rare neurological phenomenon. Neurocase. 20(5):487–95. 10.1080/13554794.2013.826680. Cited in: PMID.

- Sherer M, Katz DI, Bodien YG, Arciniegas DB, Block C, Blum S, Doiron M, Frey K, Giacino JT, Graf M, et al. Post-traumatic Confusional State: A Case Definition and Diagnostic Criteria. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2020;101:2041–50. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2020.06.021. Cited in: PMID: 32738198.

- Hagen C, Malkmus D, Durham P. Rancho Los Amigos levels of cognitive functioning scale. In: Tate R, Eds. A compendium of tests, scales and Questionnaires. 1st. London: Psychology Press; 1972. p. 42–44. 10.4324/9781003076391-10

- Whyte J, Kunz R. Rancho Los Amigos Scale. Encyclo Clin Neuropsych. 2018;2932–33. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-57111-9_67.

- Corrigan JD. Development of a scale for assessment of agitation following traumatic brain injury. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 1989;11(2):261–277. doi: 10.1080/01688638908400888. Cited in: PMID: 2925835.

- Symonds CP. Discussion on differential diagnosis and treatment of Post-Contusional States. Proc R Soc Med. 1942;35(9):601–14. doi:10.1177/003591574203500905. Cited in: PMID: 19992544.

- Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. 2010;5(1):69. doi:10.1186/1748-5908-5-69.

- Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, Moher D, Peters MDJ, Horsley T, Weeks L, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–73. doi:10.7326/M18-0850.

- Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277–1288. doi:10.1177/1049732305276687.

- Corrigan JD, Mysiw WJ, Gribble MW, Agitation CS. Cognition and attention during post-traumatic amnesia. Brain Inj. 1992;6(2):155–60. doi: 10.3109/02699059209029653. Cited in: PMID: 1571719.

- Fugate LP, Spacek LA, Kresty LA, Levy CE, Johnson JC, Mysiw W. Definition of agitation following traumatic brain injury: I. A survey of the brain injury Special Interest Group of the American Academy of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1997;78(9):917–23. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(97)90050-2. Cited in: PMID: 9305261.

- Nielsen AI, Power E, Jensen LR. Communication with patients in post-traumatic confusional state: perception of rehabilitation staff. Brain Inj. 2020;34(4):447–455. doi: 10.1080/02699052.2020.1725839. Cited in: 32050798.

- Steel J, Ferguson A, Spencer E, Togher L. Social Communication Assessment During Post-traumatic Amnesia and the Post-acute Period after Traumatic Brain Injury. Brain Inj. 2017;31(10):1320–1330. doi: 10.1080/02699052.2017.1332385. Cited in: PMID: 28657359.

- Spiteri CJ, Ponsford JL, Roberts CM, McKay A. Aspects of cognitive impairment associated with agitated behavior during Post-traumatic Amnesia. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2022;28(4):382–90. doi: 10.1017/S1355617721000588. Cited in: PMID: 33998433.

- Searby A, Maude P. Graduate Nurse perceptions of caring for people with posttraumatic amnesia. J Neurosci Nurs. 2014;46(6). doi:10.1097/jnn.0000000000000098. Cited in: PMID: 25365055

- McKay A, Love J, Trevena-Peters J, Gracey J, Ponsford J. The relationship between agitation and impairments of orientation and memory during the PTA period after traumatic brain injury. Neuropsychol Rehabil. 2020;30(4):579–590. doi: 10.1080/09602011.2018.1479276. Cited in: PMID: 29860914.

- Levin HS, Grossman RG. Behavioral sequelae of closed head injury: a quantitative study. Arch Neurol. 1978;35(11):720–27. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1978.00500350024005. Cited in: PMID: 31155.

- Symonds CP. Mental disorder following head injury. Proc R Soc Med. 1937;30(9):1081–1094. doi:10.1177/003591573703000926. Cited in: PMID: 19991202.

- Nakase-Thompson R, Sherer M, Yablon SA, Nick TG, Trzepacz PT. Acute confusion following traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj. 2004;18(2):131–142. doi: 10.1080/0269905031000149542. Cited in: PMID: 14660226.

- Jackson RD, Mysiw WJ, Corrigan JD. Orientation group monitoring system: an indicator for reversible impairments in cognition during Posttraumatic Amnesia. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1989;70(1):33–36. doi: 10.1016/S0003-9993(21)01643-9. Cited in: PMID: 2916916.

- Andriessen TM, de Jong B, Jacobs B, van der Werf SP, Vos PE, van der Werf SP. Sensitivity and specificity of the 3-item memory test in the assessment of post traumatic amnesia. Brain Inj. 2009;23(4):345–52. doi: 10.1080/02699050902791414. Cited in: PMID: 19330596.

- Briggs R, Brookes N, Tate R, Lah S. Duration of post-traumatic amnesia as a predictor of functional outcome in school-age children: a systematic review. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2015;57(7):618–627. doi: 10.1111/dmcn.12674. Cited in: PMID: 25599763.

- Ahmed S, Bierley R, Sheikh JI, Date ES. Post-traumatic amnesia after closed head injury: a review of the literature and some suggestions for further research. Brain Inj. 2000;14(9):765–80. doi: 10.1080/026990500421886. Cited in: 11030451.

- Russell WR. Cerebral Involvement in Head Injury. Brain. 1932;55(4):549–603. doi:10.1093/brain/55.4.549.

- McNett M, Sarver W, Wilczewski P. The prevalence, treatment and outcomes of agitation among patients with brain injury admitted to acute care units. Brain Inj. 2012;26(9):1155–1162. doi: 10.3109/02699052.2012.667587. Cited in: PMID: 22642404.

- Trevena-Peters J, McKay A, Spitz G, Suda R, Renison B, Ponsford J. Efficacy of activities of daily living retraining during posttraumatic amnesia: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabilitation. 2018;99(2):329–37.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2017.08.486. Cited in: PMID: 28947165.

- Max J, Koele S, Castillo C, Lindgren SD, Arndt S, Bokura H, Robin DA, Smith WL, Sato Y. Personality change disorder in children and adolescents following traumatic brain injury. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2000;6(3):279–289. doi:10.1017/S1355617700633039. Cited in: PMID: 10824500.

- Warriner EM, Velikonja D. Psychiatric disturbances after traumatic brain injury: neurobehavioral and personality changes. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2006;8(1):73–80. doi:10.1007/s11920-006-0083-2. Cited in: PMID: 16513045.

- Marsh NV, Kersel DA, Havill JH, Sleigh JW. Caregiver burden at 1 year following severe traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj. 1998;12(12):1045–1059. doi: 10.1080/026990598121954. Cited in: PMID: 9876864.

- McGhee H, Cornwell P, Addis P, Jarman C. Treating dysarthria following traumatic brain injury: investigating the benefits of commencing treatment during Post-traumatic Amnesia in two participants. Brain Inj. 2006;20(12):1307–1319. doi: 10.1080/02699050601081851. Cited in: PMID: 17132553.

- Reyes RL, Bhattacharyya AK, Heller D. Traumatic head injury: restlessness and agitation as prognosticators of physical and psychologic improvement in patients. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1981;62(1):20–23. Cited in: PMID: 7458627.

- Van Der Naalt J, Van Zomeren AH, Sluiter WJ, Minderhoud JM. Acute behavioral disturbances related to imaging studies and outcome in mild-to-moderate head injury. Brain Inj. 2000;14(9):781–88. doi: 10.1080/026990500421895. Cited in: PMID: 11030452.

- Nott MT, Chapparo C, Heard R, Baguley IJ. Patterns of agitated behavior during acute brain injury rehabilitation. Brain Inj. 2010;24(10):1214–21. doi: 10.3109/02699052.2010.506858. Cited in: PMID: 20715891.

- Noé E, Ferri J, Trénor C, Chirivella J. Efficacy of ziprasidone in controlling agitation during post-traumatic amnesia. Behav Neurol. 2007;18(1):7–11. doi: 10.1155/2007/529076. Cited in: PMID: 17297214.

- Wolffbrandt MM, Poulsen I, Engberg AW, Hornnes N. Occurrence and severity of agitated behavior after severe traumatic brain injury. Rehabil Nurs. 2013;38(3):133–141. doi: 10.1002/rnj.82. Cited in: PMID: 23658127.

- Sherer M, Nakase-Thompson R, Yablon SA, Gontkovsky ST. Multidimensional assessment of acute confusion after traumatic brain injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;86(5):896–904. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2004.09.029. Cited in: PMID: 15895334.

- Brooke MM, Questad KA, Patterson DR, Bashak KJ. Agitation and restlessness after closed head injury: a prospective study of 100 consecutive admissions. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1992;73(4):320–23. doi: 10.1016/0003-9993(92)90003-f. Cited in: PMID: 1554303.

- Rao N, Jellinek HM, Woolston DC. Agitation in closed head injury: haloperidol effects on rehabilitation outcome. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1985;66(1):30–34. Cited in: PMID: 3966865.

- Harmsen M, Geurts AC, Fasotti L, Bevaart BJ. Positive behavioral disturbances in the rehabilitation phase after severe traumatic brain injury: an historic cohort study. Brain Inj. 2004;18(8):787–96. doi: 10.1080/02699050410001671757. Cited in: PMID: 15204319.