ABSTRACT

Introduction

Over 100 million people worldwide live with disabilities resulting from an acquired brain injury (ABI). ABI survivors experience cognitive and physical problems and require support to resume an active life. They can benefit from support from someone who has been through the same issues (i.e. peer mentor). This review investigated the effectiveness of peer mentoring for ABI survivors.

Method

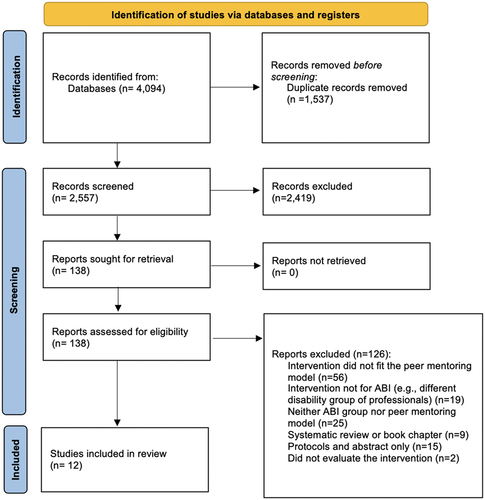

Eleven databases, two trial registers, and PROSPERO were searched for published studies. Two reviewers independently screened all titles, abstracts, and full texts, extracted data, and assessed quality. The PRISMA 2020 guidelines were followed to improve transparency in the reporting of the review.

Results

The search returned 4,094 results; 2,557 records remained after the removal of duplicates and 2,419 were excluded based on titles and abstracts. Of the remaining 138, 12 studies met the inclusion criteria. Five were conducted in the United States, three in Canada, three in the UK, and one in New Zealand. Meta-analysis was inappropriate due to the heterogeneity of study designs. Therefore, a narrative synthesis of the data was undertaken.

Conclusion

Although peer mentoring has the potential to positively influence activity and participation among ABI survivors, further research is needed to understand the extent of the benefits.

Introduction

Acquired brain injury (ABI) is defined as any form of injury to the brain sustained since birth (Citation1). Possible causes include traumatic brain injury (TBI), stroke, brain tumors, meningitis, encephalitis, hydrocephalus, oxygen deprivation (anoxia), neurotoxicity disorders, infections, electrolyte imbalances and others.

Worldwide, an estimated 40 million people are admitted to hospitals annually with TBI or strokes, the leading causes of ABI (Citation2,Citation3). At least 135 million people worldwide live with long-term disabilities resulting from TBIs and strokes, with many more affected by other forms of ABI (Citation2,Citation4,Citation5).

ABIs can result in long-term physical, cognitive, emotional, and behavioral problems and personality changes that limit social interaction and participation in daily activities (Citation6). Even people with minor head injuries can experience long-term difficulties (Citation7).

Participation in personally valued activities is an important factor in life satisfaction, quality of life, well-being and social integration following brain injury (Citation8). Evidence suggests that ABI survivors have problems occupying their time in meaningful ways (Citation9–11).

Peer mentoring can help people to resume personally valued activities and is defined as ‘a relationship in which two individuals share some common characteristic or experience and one provides needed assistance or support to the other’ (Citation12). It is ‘purposeful [and] unidirectional, where the mentor is there to function as a support for the mentee’ (Citation13). Peer mentoring has been employed in the management of various long-term conditions, including spinal injury (Citation14), diabetes (Citation15), and cancer (Citation16).

As part of a larger study (to be reported elsewhere) to design and test a peer mentoring intervention for people with ABI, we set out to systematically review the available evidence on peer mentoring following ABI to a) determine the effectiveness of peer mentoring interventions in enhancing participation in activities among people with ABIs, b) determine whether peer mentoring is effective in enhancing other outcomes such as quality of life, mood, confidence, satisfaction, and behavior management, and c) the design of peer mentoring interventions and issues affecting their implementation.

Materials and methods

This review was carried out in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Citation17) and a protocol was registered on the PROSPERO International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (CRD42016050395).

Studies of any design which employed and evaluated a model of individualized peer mentoring support between ABI survivors were included. The term ‘peer mentoring’ is used here for consistency, but similar concepts may be defined differently and use a variety of models. Any form of peer mentoring intervention was included in the review if it did not vary widely from the model of individualized peer support. Only full-text articles published in English and in peer-reviewed journals were included.

Studies were excluded if they employed group support models or exclusively used non-ABI survivors in either mentor or mentee roles. Papers which simply described a peer mentoring service but failed to evaluate the experiences of people with ABI receiving peer mentoring support were excluded.

Literature searches were developed across a range of databases using indexing terms (e.g., medical subject headings (MeSH) and Embase’s Emtree thesaurus) and text words relating to ABI and peer mentoring. Participation and activity-related terms were not included to keep the search broad and avoid excluding any relevant studies. The search strategy was adapted to the requirements of each database.

The following 11 medical, health, social care, and psychology databases were searched in late October 2022 (see Appendix 1 for examples of the search strategy for selected databases): MEDLINE (Ovid: 1946 to 18.10.22); PsycINFO (Ovid: 1806 to Week 2 October 2022); EMBASE (Ovid: 1974–18.10.22); CINAHL Plus with Full Text (EBSCOHost: 1986 to 18.10.22); Web of Science Core Collection (Thomson Reuters: 1970 to 18.10.22); Scopus (Elsevier: 1970 to 18.10.22); Cochrane Library (including Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR); Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL); Cochrane Methodology Register (CMR); Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE); Health Technology Assessment Database (HTA); NHS Economic Evaluation Database (EED) (Wiley: 1996 to 18.10.22); AMED (Ovid: 1985 to 18.10.22); ASSIA: Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts (ProQuest: 1987 to 18.10.22); LILACS (Bireme 1982 to 1.11.16).

A search was conducted in PROSPERO for ongoing reviews in the same topic area. Research in progress was identified through the ISRCTN registry (www.isrctn.com) and Clinical Trials (www.clinicaltrials.gov) websites. Hand searches of reference lists of relevant papers were conducted, and citation searches were undertaken using SCOPUS and Google Scholar.

Three researchers independently assessed titles and abstracts using a PICO (Participants, Intervention, Comparator, Outcomes) screening and selection tool and shortlisted studies for inclusion. Full texts were obtained for all shortlisted articles and two reviewers assessed them for inclusion in the review. Any discrepancies were resolved through discussion, with the involvement of a third reviewer (KR), a senior member of the research team, who supported the researchers screening studies to resolve any discrepancies and make a final decision if necessary.

Data extraction sheets were developed and piloted based on outcomes identified in the PICO selection tool (appendix 2). Three researchers (RM, JFS and BDP) extracted data independently; discrepancies were resolved through discussion. Data were extracted on the following elements: Participant demographics; Description of intervention and program using the template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) (Citation18); Details of mentor training; Logistical challenges; Primary outcome (activities, participation, social interaction, community integration); Secondary outcomes (measures of mood; measures of life satisfaction and quality of life; measures of disability management; measures of behavior management; measures of confidence; measures of resilience; measures of participant feedback; adverse events; other outcomes); study design.

Due to the broad range of methodologies included in the review, studies were assessed for quality and risk of bias using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) – Version 2018 (Citation19). This tool is designed for reviews including qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods studies.

Meta-analysis was inappropriate due to the scarcity of studies and the heterogeneity of designs. Therefore, a narrative synthesis of the data was undertaken in accordance with published guidelines (Citation20). This focused on both the implementation and effectiveness of the interventions.

Results

The screening process resulted in 12 studies, reporting on 11 interventions being included in the review (), published between 2002 and 2022. Two studies reported findings about the same trial [SUPERB feasibility trial] in two manuscripts, one presented the main trial results (Citation21), and another one presented the post-intervention interviews of the trial (Citation22). A third study evaluating the fidelity of the SUPERB feasibility trial (Citation23) was excluded because the quantitative and qualitative findings of the trial were reported in the other two papers (Citation21,Citation22); thus, the fidelity study did not report any new information for the review. The PRISMA 2020 Checklist is presented in appendix 3.

Five studies were conducted in the United States (Citation24–28), three in Canada (Citation29–31), three in the UK (Citation21,Citation22,Citation32), and one in New Zealand (Citation33). Appendix 4 includes the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) checklist (Citation18) for the 13 interventions identified in the review.

Quality assessment and summary of study designs

The studies included a randomized controlled trial (RCT) (Citation26), a feasibility RCT (Citation21), a pilot RCTs (Citation27), a pilot feasibility RCT (Citation30), two case studies (Citation28,Citation29), two qualitative studies (Citation22,Citation33), a concurrent mixed methods design with no control group (Citation25), a co-design and feasibility testing study (Citation32), a mixed methods pilot study (Citation31), and a quantitative before-and-after study with no control group (Citation24). A summary of the study characteristics is presented in .

Table 1. Summary of studies included in the systematic review.

The wide range of study designs meant comparing them in terms of quality was not possible. The quality assessment of each study according to the MMAT 2018 criteria (Citation19) is presented in .

Table 2. Risk of bias assessment.

Participants characteristics

The demographic characteristics of mentors and mentees are presented in . Study populations included adults with stroke or post-stroke aphasia (Citation21,Citation22,Citation32); adults with TBI (Citation27,Citation30,Citation33); adolescents with encephalitis (mentee) and TBI (mentor) (Citation28); adults with TBI and family members (mentors and mentees) (Citation25); adults with a brain tumor (Citation31); young people (16–26 year-olds) with neurological conditions (including TBI) (mentees); adults with neurological conditions, rehabilitation professionals or family members (mentors) (Citation24); adult stroke survivors (mentors and mentees), plus health professionals, program coordinators and care partners (for qualitative evaluation) (Citation29); adults (16 years old and over) with TBI and significant others (mentors and mentees) (Citation26).

The two service description papers reported delivering support to 200 TBI survivors from 1994–1996, with 22 peer supporters and 19 stroke survivors with four mentors.

The studies included information regarding the eligibility criteria and desirable characteristics to recruit the mentors. The most common characteristics reported were being a good listener (Citation22,Citation25,Citation28,Citation31), having empathy (Citation22,Citation25,Citation28,Citation31), being able to share life experiences (Citation22,Citation31,Citation33), willingness/motivation to help others (Citation25,Citation26,Citation28,Citation30,Citation32), and having adequate personal adjustment (Citation24–28).

Effectiveness of peer mentoring intervention in enhancing participation

The key outcome measures of interest in this review are summarized in .

Intervention outcomes

There was no evidence that peer mentoring interventions improved participation outcomes in people with ABI. This came from one RCT (Citation26), one pilot feasibility trial (Citation30), one pilot RCT (Citation27), one feasibility RCT (Citation21), one pilot concurrent mixed methods study (Citation25), a case study (Citation28), and a before and after non-randomized study (Citation24). The heterogeneity in the study designs and outcome measures used meant metanalysis was not possible.

The RCT by Hanks et al. (Citation26). found that the mentored TBI group showed lower scores than the control group in the Community Integration Measure (CIM). The pilot feasibility RCT by Levy et al. (Citation30). found no significant change in the community integration questionnaire (CIQ). Hilari et al. (Citation21). found a small but not-significant improvement in the general health questionnaire (GHQ-12), and no change in the CIQ. Hibbard et al. (Citation25) found no impact on the social support section of the Traumatic Brain Injury-Mentoring Partnership Program questionnaire. Mentored participants in the study by Struchen et al. (Citation27). showed an increase in perceived social support, while the control group showed a decline. This group also experienced a non-significant increase in social activity levels (Citation27).

Two studies (Citation24,Citation28) identified a small improvement in the participation domain of the Mayo-Portland Adaptability Inventory-4.

The participants and program successes of Kolakowsky-Hayner et al. (Citation24) showed non-significant improvements on the Craig Handicap Assessment and Reporting Technique – Short Form (CHART-SF) Occupation and Social Integration sub-scales. The active peer mentoring participants in the Struchen et al. (Citation27). study showed non-significant improvements only in the social integration sub-scale of the CHART-SF.

Effectiveness of peer mentoring in enhancing quality of life, mood, confidence, satisfaction and behavior management

There was limited evidence that peer mentoring interventions improved the secondary outcomes of interest. This came from one RCT (Citation26), one pilot feasibility trial (Citation30), one pilot RCT (Citation27), one feasibility RCT (Citation21), and a case study (Citation28).

Two studies (Citation26,Citation28) found improved quality of life for the mentees after the peer mentoring intervention. Hilari et al. (Citation21). found a small (close to zero) benefit of the intervention on friendship, communication participation measures, depression, and well-being measures. However, this study showed no difference in communication confidence levels between the intervention and control group (Citation21).

Regarding the impact of mentoring on mood, a study found no significant difference in measures of mood or self-efficacy (Citation30). They found a statistically significant reduction in pain at two months post-intervention (p = 0.02), but this was not maintained at any other time point (Citation30). Struchen et al. (Citation27). found a statistically significant (p = <.01) increase in depressive symptoms after mentoring in the intervention group and no impact on the loneliness scale. Hanks et al. (Citation26). found that mentored TBI participants had significantly better behavioral control (p=0.04), lower alcohol use (p=0.01), and were less emotion-focused (p=0.04).

Qualitative findings

Eight papers reported the impact of peer mentoring based on participants’ experiences, indicating potential outcomes for future research.

Across studies incorporating qualitative methods, a positive impact of peer mentoring support was reported by mentors and mentees. Many reported the benefits of sharing and learning about the lived experiences of people who have been through something similar (Citation22,Citation24–28,Citation30,Citation33). The mentees felt increased hope, received valuable guidance, and felt less lonely (Citation25–31,Citation33). Mentees also explained that the peer mentoring support took them out of their comfort zone and encouraged them to act toward overcoming their difficulties (Citation32). Setting goals helped them remain motivated and work toward a shared purpose (Citation30,Citation32).

The mentors also experienced a positive feeling and sense of accomplishment, as well as decreased anxiety and improved communication skills related to the mentoring experience (Citation31).

Design of peer mentoring intervention and issues affecting their implementation

Delivery mode and setting

The intervention delivery modes differed between the studies. Five interventions involved appointments exclusively face-to-face (Citation21,Citation22,Citation28,Citation31–33), three studies allowed a combination of sessions via face-to-face, telephone, and/or e-mail according to the participants’ preferences (Citation24–26), two studies reported an initial appointment face-to-face followed by remote sessions (Citation27,Citation29), and one study mostly via telephone (Citation30). Nine interventions were conducted in a community setting (Citation21,Citation22,Citation24–28,Citation30,Citation32,Citation33), and two occurred in a hospital (Citation29,Citation31).

Matching criteria

The study which employed peer supporter visits to a rehabilitation unit did not match participants on specific criteria but on a convenience basis (Citation26). The other studies all matched mentor and mentee pairings according to specific criteria. The most common criteria shared by the studies were geographical location (Citation24,Citation25,Citation27,Citation32), gender (Citation21,Citation22,Citation24,Citation25,Citation27,Citation28), age (Citation21,Citation22,Citation24,Citation25,Citation27), interests (Citation21,Citation22,Citation24,Citation25,Citation27,Citation28), cultural factors (Citation21,Citation22) and personal attributes (e.g., openness, positivity, similarity in symptoms experienced) (Citation32).

One study attempted to match for disability type as this was the only study with participants who had different neurological conditions (Citation24). Additional criteria included: the current mentee load of mentors; similarity of communication difficulties; and a shared vision for enhancing quality of life for persons living with aphasia. Hibbard et al. (Citation25). also reported additional criteria, including marital status; educational background; cognitive challenges; physical challenges; cause of TBI; and ability to meet specific psychological needs, such as the need for structure, role model, and social support (Citation25). Two studies had no clear matching criteria (Citation31,Citation33).

Frequency, intensity, and duration

Only one intervention involved a single meeting with a mentor (Citation31). The rest included different levels of frequency and intensity. Three studies included interventions with up to six 1-hour sessions (Citation21,Citation22,Citation32,Citation33). However, the intervention duration of these studies varied between three and six months.

Other interventions included one 10-minute visit followed by six telephone follow-ups of 5–60 minutes (Citation33), one visit day a week for 10 weeks (Citation28), and a four-month intervention with meetings once a week (Citation30). One intervention involved a minimum of three contacts per month with the aim to end partnerships when mentees had achieved their employment or educational goals (Citation24).

The intervention for the RCT ran for twelve months (Citation26). The pairings were intended to meet weekly for the first month, biweekly for the next two to three months, and then monthly for the remainder of the first year. The pilot RCT by Struchen et al. (Citation27). ran for three months. Most partnerships in both studies did not meet the requirements for the number and frequency of meetings.

For another study, the frequency and number of contacts, and partnership duration were entirely at the discretion of the participants (Citation25).

Content, activities, and processes of interventions

Descriptions varied considerably regarding the content addressed during the contacts between the pairs. Overall, the interventions included activities focused on supporting mentees to integrate into the community, access resources and social opportunities (Citation24,Citation26,Citation27,Citation30,Citation33), increasing awareness about the health condition of the mentee and in some instances, their families (Citation25,Citation26), addressing cognitive, emotional, and physical needs (Citation25,Citation26,Citation28,Citation30,Citation31), support with employment or education (Citation24,Citation30), providing hope (Citation29), developing intervention goals and working toward achieving them (Citation21,Citation22,Citation32), referrals to other services to overcome issues (Citation30), participating in leisure activities (e.g., getting nails done, coffee, lunch) and sharing feelings (Citation33).

Programs were facilitated in some cases by professionals such as program coordinators (Citation24,Citation25,Citation29), researchers (Citation28), vocational rehabilitation counselors (Citation24), rehabilitation psychologists (Citation24), psychologists (Citation26), and community coordinators (Citation26).

Mentor training

All the studies provided details of mentor training. The training was delivered by a variety of professionals including speech and language therapists (Citation21,Citation22), neuropsychologists (Citation27), clinical linguists (Citation21,Citation22), rehabilitation psychologists (Citation24), rehabilitation consultant (Citation33) and program staff, hospital staff and researchers (Citation24,Citation27–29,Citation31–33).

The training included topics such as clarifying the role of the mentor (Citation21,Citation22,Citation31,Citation33), emotional management (Citation31), communication and listening skills (Citation21,Citation22,Citation25,Citation26,Citation29,Citation30,Citation32), knowledge of brain injury and its effects (Citation25–28,Citation33), techniques for building relationships and rapport with mentees (Citation26,Citation28,Citation33), advocacy skills (Citation25), accessing community resources (Citation25,Citation27,Citation28), enhancing social functioning and skill acquisition of mentees (Citation25,Citation27,Citation28), handling difficult situations/inappropriate conversation/problem behavior (Citation21,Citation22,Citation27,Citation28,Citation30,Citation31,Citation33), and goal setting (Citation21,Citation22,Citation32).

Some of the programs provided written guides and training manuals to mentors (Citation21,Citation22,Citation25–27).

Logistical problems

Two studies did not report logistical problems (Citation28,Citation31). Multiple studies encountered the same logistical difficulties when implementing the peer mentoring intervention.

Seven studies reported challenges associated with the delivery and implementation of the peer mentoring intervention such as problems scheduling times and locations for meetings (Citation22,Citation24,Citation25,Citation31,Citation33), making allowances for the mentors’ cognitive difficulties (Citation27,Citation29), budgeting for transport (Citation29), providing sufficient mentoring and staff support time (Citation27,Citation33), mentors and mentees living far away (Citation24), lack of accessible meeting locations (Citation24), short intervention timeframe to develop a good relationship (Citation33,Citation34), and loss of participants’ interest due to delay between enrollment and matching (Citation24).

There were also challenges associated with the research methods such as difficulties recruiting participants (Citation21,Citation25,Citation26,Citation29,Citation30,Citation32), identifying suitable mentors (Citation25,Citation27), having too many matching criteria (Citation24), retaining participants during the intervention (Citation24–27,Citation29,Citation32), and contacting participants for follow-up (Citation25,Citation29).

Discussion

The three main aims of this review were to assess the evidence of peer mentoring’s effectiveness in enhancing participation in activities; and evidence for its effectiveness in other ways, such as enhancing quality of life and mood and to investigate issues relating to the design and implementation of previous ABI peer mentoring studies.

There was no evidence that peer mentoring interventions improved participation outcomes in people with ABI. The studies showed small or non-significant impact on participation levels and satisfaction. Two studies looked primarily at participation (Citation27,Citation30). Struchen et al. (Citation27). employed a ‘social peer mentoring’ intervention. However, there were no significant improvements for mentored participants in the number of social activities and interactions or satisfaction with social life. Despite this, the authors reported a trend in the mentored group toward increased satisfaction with social life over the previous month. The study also demonstrated some improvements in perceived social support and social integration. Non-significant improvements in the participation domain of the Mayo-Portland Adaptability Inventory-4 were shown (Citation24,Citation28) and CHART-SF occupation and social integration sub-scales (Citation24,Citation27) but mentored participants had lower scores than controls on the Community Integration Measure (Citation26). Overall, despite limited evidence, there is reason to think that with a specific focus on enhancing participation levels, future studies may have success.

A secondary aim was to ascertain the evidence for peer mentoring’s effectiveness in enhancing other key rehabilitation outcomes, such as quality of life, mood, behavior management, and confidence. There were several significant improvements in measures of the quality of life (Citation26,Citation28), mood (Citation21,Citation26), disability management (Citation24), general health (Citation21), coping styles, behavioral control, and alcohol use (Citation26). These findings provide encouraging evidence for the effectiveness of these programs. However, the increase in depressive symptoms found by Struchen et al. (Citation27). should be considered carefully in future studies, with participants monitored carefully for any signs of negative effects. As Struchen et al. (Citation27). hypothesized, these symptoms may be attributable to participants’ increased awareness of their condition, so may decrease over time as participants learn how to manage their difficulties. Support should be made available for anyone who experiences negative effects.

A particularly encouraging finding was the high level of satisfaction and positive feedback reported in qualitative findings across the studies. Although no significant improvements were found in participation levels by Struchen et al. (Citation27). participants themselves felt that their mentors helped them to increase their social activities and feel less lonely. Other benefits included emotional and affirmational support; shared experience; increased confidence; social support; having someone to talk to; enhanced knowledge of brain injury and community services; learning about coping strategies and receiving motivation and inspiration. The mentors involved also experienced a positive feeling from healing others (Citation27,Citation31), decreased anxiety and improved communication skills because of the study (Citation31).

The final aim of the review was to elicit from previous research relevant information about the design and implementation of peer mentoring interventions for ABI. Heterogeneity in the research designs and clinical populations included made it difficult to draw any firm conclusions about the optimal design of a peer mentoring intervention for people with ABI. Most studies involved mentors and mentees with the same form of injury (predominantly stroke or TBI). This made it difficult to infer whether including participants with a range of ABIs as mentors and mentees in a future study would be successful. Fraas and Bellerose’s study involved an encephalitis survivor mentoring a TBI survivor, however, this was a single case study (Citation28). Kolakowski-Hayner et al. (Citation24). included a mixture of neurological disabilities, which meant that the results could not be interpreted as applying generally to people with ABI. Ozier & Cashman included brain tumor participants, with only 10 mentees and three mentors (Citation31).

There were also differences in the demographics of the populations, including the time since mentees sustained their injuries, with some still in hospital, some recently returned to the community, and some several years post-injury. This made it difficult to draw conclusions about the optimum stage of recovery for delivering peer mentoring interventions. Four pilot and feasibility RCTs have been conducted. One included only stroke survivors (Citation21,Citation22) and three were exclusive to TBI survivors (and significant others) (Citation26,Citation27,Citation30). Two were pilot studies with few participants (Citation27,Citation30). Most mentored participants in both studies were male with moderate or severe injuries. As such there is limited information about the effectiveness of peer mentoring for people of other genders, or for people with less severe injuries. Methodological weaknesses also limit the conclusions to be drawn from the studies. For example, two studies did not assess participants at baseline, and one of these relied on self-report to assess the effectiveness of the intervention (Citation25,Citation26).

Characteristics of mentors identified by participants included authenticity, friendliness, confidence, good listening, knowledge of community resources, respectfulness, good communication skills, kindness, and experience with brain injury. These largely corresponded with, and added to, the mentor eligibility criteria pre-defined by the researchers. Future studies on peer mentoring may benefit from selecting and screening mentors carefully for these traits and providing relevant training. The feedback from mentors was positive, but there is little other evidence from the studies about the effectiveness of the training. Each program focuses on different training topics and there is a need to focus on topics specific to the goals of the intervention.

The mode of delivery, settings, and goals of the interventions varied depending on programs. For example, the early hospital one-off visits employed by a study (Citation29) had different goals from the more sustained community-based approaches used in other studies. This makes outcomes difficult to compare. There was also little information in the studies on the content of mentoring sessions themselves, so it is not known whether discussions in sessions kept to the intended topics or what activities took place. This is understandable, as sessions were largely intended to be private interactions between the partners, but a more rigorous approach to documenting session content would inform future research and help to determine the active ingredients of ABI peer mentoring. It will be important to carefully select the mode of delivery and settings depending on project goals.

The inclusion and exclusion criteria are important considerations. The ones used in the included studies varied and those with more stringent criteria had difficulty recruiting participants. While it is important not to include people who won’t benefit (such as those with severe cognitive problems or who will not be able to communicate with others or learn from the experience), it is also important not to exclude people unnecessarily.

There was considerable variation in the nature of the contacts between pairs (with most studies allowing in-person, telephone, or e-mail correspondence), the frequency of contacts, and the duration of partnerships. Consistent implementation of these variables is important to understand the factors which influenced outcomes. The study which implemented a consistent approach to duration, frequency, and mode of contact was successful at bringing the partners together as planned (Citation28). This study required partners to meet once a week for 10 weeks at a specific time and venue. Future studies could learn from this and provide a fairly rigid structure for the frequency and nature of meetings. However, it should be noted that these papers focused on single case studies, so the approach may not be as successful when implemented with multiple partnerships. It will be important to consider the issue when matching partners and to consider their preferred means of contact. The goal and focus of the intervention are also key to this issue. If the focus is purely on discussing problems and speaking to a person who understands the difficulties, then phone conversations may be appropriate. However, if the goal is to participate in activities, then face-to-face contact in the community would be most effective.

Although the papers described the criteria employed to match partners together, they provided little information on how easy this was to implement in practice. It is a key consideration for future studies to match participants to suitable mentors soon after recruitment. It can be inferred from the high levels of participant satisfaction with mentors that those who completed the programs were matched together appropriately. However, future studies should provide more detailed information on the matching process and the reasons for unsuccessful matches and participant drop-out. Key considerations must be the personal preference of the participants and the convenience of contact.

Practical and logistical challenges related to scheduling meetings, staffing resources, maintaining participant involvement, and accommodating participants’ cognitive difficulties. Researchers should consider these when designing peer mentoring interventions or planning future research. For example, help with arranging venues and transport for a project involving face-to-face meetings in the community, convenience, provision of support for both partners. Other considerations include, carefully matching partners, providing expenses and making the experience as enjoyable, rewarding and undemanding as possible.

This review has shown that there is a lack of definitive RCTs. The evidence available comes from small-scale studies, employing different models of mentoring, methodologies, and outcome measures. Conducting a meta-analysis or reporting a combined number of participants was not performed due to the variety of study types, including service descriptions, single case studies, and small RCTs.

One strength of this study is the use of the TIDieR checklist (Citation18) to describe the peer mentoring interventions delivered in studies included in the review. This study has several limitations. A potential limitation of this review is that the studies included in the review had a small sample size, and there was heterogeneity in outcomes measured and follow-up assessments. Another limitation of this study may refer to publication bias because we only included studies written in English and published in peer-reviewed journals; therefore, we may have not conducted a comprehensive review of the literature available.

Conclusion

Peer mentoring for people with ABIs is a relatively new intervention with limited supporting evidence. It has the potential to positively influence participation among ABI survivors, but this requires further investigation.

Future research is needed to identify the most important skills and qualities required in a mentor; training requirements; how best to match mentors with mentees; mentee eligibility criteria; the optimum mode of delivery and setting; and to determine the frequency, intensity and duration of peer mentoring sessions required to be effective in promoting positive outcomes. Researchers must also carefully select measures sensitive enough to measure the desired outcomes. Mixed methods studies will help researchers to quantitatively assess intervention effectiveness and explore the acceptability of peer mentoring for participants.

In light of newer guidance on developing and evaluating complex interventions, a review focused on identifying the underlying theory or behavior change mechanisms of peer mentoring interventions might be worth considering for future research.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (99.3 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the funders for supporting the research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/02699052.2024.2310779

Additional information

Funding

References

- Headway. Types of brain injury [Internet]. 2022. Available from: https://www.headway.org.uk/about-brain-injury/individuals/types-of-brain-injury/.

- James SL, Theadom A, Ellenbogen RG, Bannick MS, Montjoy-Venning WC, Lucchesi LR, Abbasi N, Abdulkader R, Abraha HN, Adsuar JC et al. Global, regional, and national burden of traumatic brain injury and spinal cord injury, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2016. Lancet Neurol. 2019 Jan 1;18(1):56–87. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30415-0.

- Feigin VL, Nichols E, Alam T, Bannick MS, Beghi E, Blake N, Culpepper WJ, Dorsey ER, Elbaz A, Ellenbogen RG, et al. Global, regional, and national burden of neurological disorders, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2016. Lancet Neurol. 2019 May 1;18(5):459–80. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30499-X.

- Johnson CO, Nguyen M, Roth GA, Nichols E, Alam T, Abate D, Abd-Allah F, Abdelalim A, Abraha HN, Abu-Rmeileh NM, et al. Global, regional, and national burden of stroke, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2016. Lancet Neurol. 2019 May 1;18(5):439–58. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(19)30034-1.

- Avan A, Digaleh H, di Napoli M, Stranges S, Behrouz R, Shojaeianbabaei G, Amiri A, Tabrizi R, Mokhber N, Spence JD, et al. Socioeconomic status and stroke incidence, prevalence, mortality, and worldwide burden: an ecological analysis from the global burden of disease study 2017. BMC Med. 2019 Oct 24. 17(1): 1–30. doi:10.1186/s12916-019-1397-3.

- Andelic N, Hammergren N, Bautz-Holter E, Sveen U, Brunborg C, Røe C. Functional outcome and health-related quality of life 10 years after moderate-to-severe traumatic brain injury. Acta Neurol Scand. 2009 Jul 1;120(1):16–23. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0404.2008.01116.x.

- Williams W, Potter S, Of NH, Undefined N. Mild traumatic brain injury and postconcussion syndrome: a neuropsychological perspective. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2010;81(10):1116–22. 2010. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2008.171298.

- Malley D, Cooper J, Cope J. Adapting leisure activity for adults with neuropsychological deficits following acquired brain injury. NeuroRehabilitation. 2008 Jan 1;23(4):329–34. doi:10.3233/NRE-2008-23406.

- Bier N, Dutil E, Couture M. Factors affecting leisure participation after a traumatic brain injury: An exploratory study. J Head Trauma Rehabil [Internet]. 2009 May [cited 2022 Oct 31];24(3):187–94.doi: 10.1097/HTR.0b013e3181a0b15a.

- Desrosiers J, Rochette A, Noreau L, Bourbonnais D, Bravo G, Bourget A. Long-term changes in participation after stroke. Top Stroke Rehabil [Internet]. 2014 Sep [cited 2022 Oct 31];13(4):86–96. doi:10.1310/tsr1304-86.

- Wise EK, Mathews-Dalton C, Dikmen S, Temkin N, MacHamer J, Bell K, Powell JM. Impact of traumatic brain injury on participation in leisure activities. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2010 Sep 1;91(9):1357–62. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2010.06.009.

- Sherman JE, DeVinney DJ, Sperling KB. Social support and adjustment after spinal cord injury: influence of past peer-mentoring experiences and Current live-in partner. Rehabil Psychol. 2004 May [cited 2022 Oct 31]; 49 (2):140–49. doi:10.1037/0090-5550.49.2.140.

- Hayes E, Balcazar F. Mentoring: program development, relationships and outcomes. In: Keel M, editor. Peer-mentoring and disability: current applications and future directions. New York: Nova Science Publishers; 2009. p. 123–41.

- Ljungberg I, Kroll T, Libin A, Gordon S. Using peer mentoring for people with spinal cord injury to enhance self-efficacy beliefs and prevent medical complications. J Clin Nurs InternetAvailable from. 2011 Feb 1[cited 2022 Oct 31]; 20(3–4):351–58. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2702.2010.03432.x

- Goldman ML, Ghorob A, Eyre SL, Bodenheimer T. How do peer coaches improve diabetes care for low-income patients?: a qualitative analysis. Diabetes Educ. 2013 Oct 29;39(6):800–10. doi:10.1177/0145721713505779.

- Rini C, Lawsin C, Austin J, Duhamel K, Markarian Y, Burkhalter J, Labay L, Redd WH. Peer mentoring and survivors’ stories for cancer patients: positive effects and some cautionary notes. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(1):163–66. doi:10.1200/JCO.2006.08.8567.

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009 Aug 18;151(4):264–69. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135.

- Hoffmann T, Glasziou P, Boutron I, Milne R, Perera R, Moher D, Altman DG, Barbour V, Macdonald H, Johnston M, et al. Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. British Med J. 2014; (348):g1687. doi:10.1136/bmj.g1687.

- HONG QN, Pluye P, Fàbregues S, Bartlett G, Boardman F, Cargo M, et al. MIxed methods appraisal tool (mmat) version 2018 User guide. Registration Of Copyright [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2022 Dec 1]; Available from: http://mixedmethodsappraisaltoolpublic.pbworks.com/.

- Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden A, Petticrew M, Arai L, Rodgers M, et al. Narrative synthesis in systematic reviews: a product from the ESRC methods programme. ESRC Methods Programme [Internet]. 2006; 93. Available from: http://www.ccsr.ac.uk/methods/publications/documents/Popay.pdf.

- Hilari K, Behn N, James K, Northcott S, Marshall J, Thomas S, Simpson A, Moss B, Flood C, McVicker S, et al. Supporting wellbeing through peer-befriending (SUPERB) for people with aphasia: a feasibility randomised controlled trial. Clin Rehabil. 2021 Aug 1;35(8):1151–63. doi:10.1177/0269215521995671.

- Northcott S, Behn N, Monnelly K, Moss B, Marshall J, Thomas S, et al. For them and for me: a qualitative exploration of peer befrienders’ experiences supporting people with aphasia in the SUPERB feasibility trial. 2021;44(18):5025–37 doi:10.1080/0963828820211922520.

- Behn N, Moss B, McVicker S, Roper A, Northcott S, Marshall J, Thomas S, Simpson A, Flood C, James K, et al. Supporting wellbeing through PEeR-befriending (SUPERB) feasibility trial: fidelity of peer-befriending for people with aphasia. BMJ Open. 2021 Aug 1. 11(8):e047994. 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-047994.

- Kolakowsky-Hayner SA, Wright J, Shem K, Medel R, Duong T. An effective community-based mentoring program for return to work and school after brain and spinal cord injury. NeuroRehabilitation. 2012 Jan 1;31(1):63–73. doi:10.3233/NRE-2012-0775.

- Hibbard MR, Cantor J, Charatz H, Rosenthal R, Ashman T, Gundersen N, et al. Peer support in the community: initial findings of a mentoring program for individuals with traumatic brain injury and their families. Journals Lww com. [Internet]. 2002; [cited 2022 Oct 31]. 17(2):112–31. https://journals.lww.com/headtraumarehab/Fulltext/2002/04000/Psychological_Distress_and_Family_Satisfaction.00004.aspx?casa_token=LZtG_0CQQvsAAAAA:VDtFnsmvSMRAj8PVBe8slIbeLMu10RBvn9vATfDkU9Ptu87y8X2eO9_0YVnLzLMMyhEU_pM89YHYXdn0MuJDkEq-ayW7n4SZ.

- Hanks RA, Rapport LJ, Wertheimer J, Koviak C. Randomized controlled trial of peer mentoring for individuals with traumatic brain injury and their significant others. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2012 Aug 1;93(8):1297–304. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2012.04.027.

- Struchen MA, Davis LC, Bogaards JA, Hudler-Hull T, Clark AN, Mazzei DM, Sander AM, Caroselli JS. Making connections after brain injury: development and evaluation of a social peer-mentoring program for persons with traumatic brain injury. J Head Trauma Rehabil. [Internet] 2011 Jan [cited 2022 Oct 31]; 26(1):4–19. 10.1097/HTR.0b013e3182048e98.

- Fraas M, Bellerose A. Mentoring programme for adolescent survivors of acquired brain injury. Brain Injury [Internet]. 2009;[cited 2022 Oct 31];24(1):50–61. doi:10.3109/02699050903446781.

- Kessler D, Egan M, Kubina LA. Peer support for stroke survivors: a case study. BMC Health Serv Res [Internet]. 2014 Jun 16[accessed 2022 Oct 31];14(1):1–9. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-14-256.

- Levy BB, Luong D, Bayley MT, Sweet SN, Voth J, Kastner M, Nelson MLA, Jaglal SB, Salbach NM, Wilcock R, et al. A Pilot feasibility randomized controlled trial on the Ontario Brain Injury Association Peer Support Program. Journal Of Clinical Medicine 2021. [Internet] 2021 Jun 29[cited 2022 Nov 3]. 10(13):2913. doi:10.3390/jcm10132913.

- Ozier D, Cashman R. A mixed method study of a peer support intervention for newly diagnosed primary brain tumour patients. Canadian Oncology Nursing Journal. 2016 Apr 20;26(2):104. doi:10.5737/23688076262104111.

- Masterson-Algar P, Williams S, Burton CR, Arthur CA, Hoare Z, Morrison V, et al. Getting back to life after stroke: co-designing a peer-led coaching intervention to enable stroke survivors to rebuild a meaningful life after stroke. Disabil Rehabil. 2020 May 7;42(10):1359–72. doi:10.1080/09638288.2018.1524521.

- Kersten P, Cummins C, Kayes N, Babbage D, Elder H, Foster A, Weatherall M, Siegert RJ, Smith G, McPherson K, et al. Making sense of recovery after traumatic brain injury through a peer mentoring intervention: a qualitative exploration. BMJ Open. 2018 Oct 1. 8(10):e020672. 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-020672.

- Munce SEP, Jaglal S, Kastner M, Nelson MLA, Salbach NM, Shepherd J, Sweet SN, Wilcock R, Thoms C, Bayley MT, et al. Ontario brain injury association peer support program: a mixed methods protocol for a pilot randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2019 Mar 1;9(3):e023367. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2018-023367.