ABSTRACT

Purpose

Feasibility and pilot outcomes of a new community-based program for families of children with acquired brain injury (ABI) are presented. Interventions, delivered by home-visiting and teletherapy, were underpinned by problem-solving therapy, narrative meaning making, goal-directed interventions and community system psychoeducation.

Methods

Eighty-three families of children, who had sustained an ABI before 12 years of age, had an average of 13 sessions of the ‘Family First’ (FF) intervention. A mixed-methods prospective design was employed. Feasibility was evaluated through measures of accessibility and acceptability. Goal attainment scaling and pre-post changes on standardized questionnaires assessed changes in psychosocial adjustment and quality of life.

Results

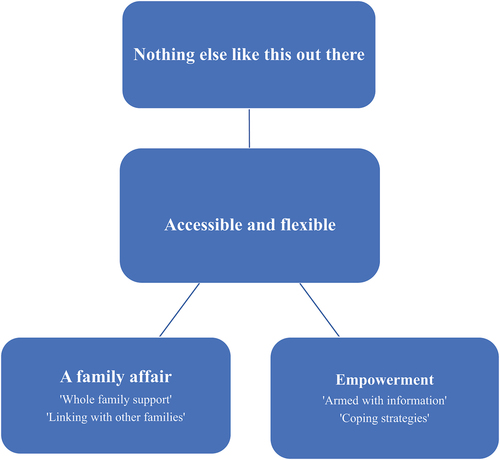

Feasibility analyses suggested engagement and retention of often hard to reach families and children with high psychosocial needs. Qualitative analyses suggested themes related to the accessibility of a unique service (‘Nothing else like this out there’ and ‘Accessible and flexible’) which facilitated ‘Empowerment’ within a family context (‘A family affair’). Promising changes on standardized scales of behavior problems, competencies and child and family quality of life were discerned. Increased goal attainment scores were observed.

Conclusion

The FF program showed feasibility and promise. It impacted positively on the lives of children and families and improved capacity in supporting systems.

Introduction

Acquired brain injury (ABI) in childhood is associated with negative outcomes for the child’s cognitive, emotional and behavioral functioning (Citation1), with direct impact on educational attainments, social inclusion and later adult adjustment (Citation2–4). Late effects are not uncommon, as the injured brain fails to develop optimally and psychosocial and educational demands increase across development (Citation4,Citation5). Moreover, childhood brain injury does not just negatively impact on the child. Elevated levels of psychosocial difficulties have been demonstrated in parents and siblings and overall family functioning (Citation2,Citation6).

The latter is important as it has become increasingly clear that family functioning is a significant predictor of outcome for the child. Parental mental health (e.g. distress, anxiety and depression), the dyadic relationship (e.g. attachment and parenting) and overall family relationships (e.g. familial environments, communication, cohesion and sibling relationships) have all been shown to predict outcomes for the injured child (Citation3,Citation4,Citation7). Bidirectional pathways to explain such associations have been formulated (Citation7). Indeed, the importance of family functioning, and family-focused interventions, have been reliably observed across the literature on children with chronic illness in general (Citation8–10).

Family-focused interventions, specifically for children with ABI, have a growing evidence base. These have varied from relatively brief psychoeducation (Citation11) and counseling (Citation12) to more intensive interventions grounded in formal relational and behavioral therapies (Citation13,Citation14). Findings have been encouraging, although some of these latter trials have involved relatively small numbers; have lacked control groups; have predominantly involved children with mild brain injury and have not documented as many child as family-related outcomes.

Perhaps, the strongest evidence for the effectiveness of family-focused interventions in pediatric ABI comes from the online family problem-solving programs formulated and evaluated in randomized controlled trials by Shari Wade and her colleagues. Problem-solving therapies have generally shown impact in interventions with pediatric populations (Citation10), and Wade’s research has demonstrated that this effectiveness is also evident for children with ABI and their families when delivered online (Citation2,Citation15). These trials have suggested benefits for both family outcomes (e.g. parental distress, family functioning and parent–child conflict) but also for child outcomes (e.g. behavioral problems, social competence and executive functioning), consistent with the ultimate goals of family-focused interventions (Citation15).

The current intervention is also based on the premise that bolstering family resilience will have benefit for both family and child outcomes. However, our intervention is further informed by Bronfenbrenner’s social ecological theory (Citation16). Whilst the family system surrounding the child may have a primary influence, next-level community systems, and especially health and school systems, are also likely to be relevant for child outcomes – both directly and indirectly through influences on the family system. Research quantifying different systemic influences for outcomes in pediatric ABI is lacking, but qualitative studies increasingly attest to the importance of such influences (Citation17,Citation18). The need for greater continuity of care, better communication and targeted community supports have been highlighted as important needs, as reported by families themselves, in the chronic stages of the child’s recovery (Citation18). Such knowledge has started to inform contemporary family-focused intervention programs (Citation19) and informed the current study.

Our ‘Family First’ (FF) program evolved across a 7-year time frame, consistent with how practice-based evidence and action research progresses (Citation20,Citation21). However, the core elements were consistent throughout. FF was predicated on the theoretical framework that bolstering family resilience will improve outcomes for the injured child, as well as the family. Thus, interventions were with respect to whole family functioning, although with a predominant focus on enabling the family to support the injured child. Interventions were tailored to specific goals formulated with families at the outset of their participation in the program. However, these specific interventions were delivered within the evidence-based problem-solving therapy framework, and specifically an adaption of our previous protocols for this with families of children with chronic illness (Citation8,Citation22,Citation23). FF included some parent workshops but the keystone of the intervention was a home-visiting program, which later pivoted onto teleinterventions (a) to increase access, especially for hard-to-reach families, from right across the region, and (b) to better inform the therapist's understanding of behaviors in context and facilitate tailored interventions with optimal ecological validity. Many of the goals formulated related to school functioning, and interfaces with healthcare agencies and professionals. Thus, interventions to build capacity in these agencies to support the child and family became a core feature of the program.

This community-based program was subject to independent evaluation by the two authors not involved in delivering the interventions (CMC and NR). In this paper, we present findings from that evaluation as practice-based evidence. Our primary research questions were as follows (Citation1) How feasible was this community-based family-focused intervention as reflected in data related to engagement, accessibility and acceptability? (Citation2) What do pilot pre – post data, related to child and family psychosocial functioning and goal attainment, tell us about promise and potential effectiveness?

Methods

Design

The evaluation was underpinned by the Medical Research Council (MRC) framework for evaluating complex interventions (Citation24), and the current paper was informed by updated MRC frameworks (Citation25) including process evaluations (Citation26). Thus, our research questions related to feasibility (including accessibility and acceptability) as well as pilot evaluations of effectiveness. A mixed methods design was employed. This combined pre-post changes on standardized instruments, as well as family reported experiences and outcomes in a qualitative arm of the design. Whilst no control group was possible within the terms of this practice-based project, repeated measures analyses were conducted, and change effect sizes assessed. Moreover, the qualitative data on family perspectives informed interpretation of any change in the quantitative measures.

Participants and procedure

Families were resident within one devolved nation of the UK (Northern Ireland) and were recruited through a brain injury organization in the voluntary sector. The essential eligibility criteria for access to the program were that the child had sustained a clinically diagnosed ABI at, or after, birth and before 12 years, and that they continued to experience at least one significant problem consequent to this, as agreed between the referrer (self or professional) and the FF team as impacting in a negative way on adjustment, social or educational inclusion. The injury had to be as a consequence of an acquired neurological insult (e.g. traumatic brain injury, infection, stroke), rather than a congenital abnormality. However, it was common that referred children had co-morbid diagnoses (e.g. learning disability and epilepsy), and such were also included with additional diagnoses recorded. At project inception, a media campaign advertised the program across the region, with specific project briefings targeted at statutory agencies (health and education) from which referrals were expected. Both self and professional/agency referrals were acceptable, although engagement with statutory agencies for information and consultation occurred for all referrals. A screening interview determined eligibility but also outlined the nature of the program to the parents to elucidate whether they were willing and able to engage with this. In some cases, other service provision was deemed necessary prior to entering the FF program. This occurred in a small number of cases and related, for example, to where risk was apparent for the child or any family member (e.g. parental mental health or capacity). Institutional ethics approval was obtained, and written consent for participation in the project was elicited from parents with child assent. The latter was confirmed by the project therapist when they met the specific family.

The family first intervention

The community program commenced in 2015. Interventions were responsive and iterative in response to feedback and interim evaluations, and consistent with action research (Citation21). Nevertheless, there were consistent elements across the life of the project which allowed for pilot evaluations of effectiveness, as well as feasibility.

As noted, our premise was that bolstering family resilience would improve outcomes for the child. Supporting the capacity of health and education agencies to support families, became a core feature of the program. Interventions were tailored to the specific goals formulated with families at the outset of the program. These typically clustered into informational needs, parenting strategies, managing cognitive, emotional and behavioral challenges, communication, interfaces with school and health care and overall family well-being. They were delivered within a specific problem-solving therapy framework for parents of children with chronic illness (Citation8,Citation22,Citation23) to encourage generalizability. Further details on the parameters of the intervention are outlined in .

Table 1. Outline of the family first intervention.

Outcome and process evaluations

The outcome and process evaluation were informed by the MRC framework as noted. This included elements related to feasibility (accessibility and acceptability) and pilot evaluations of effectiveness. As a feasibility and pilot study of effectiveness, we were not definitive about primary -v- secondary outcome measures. Thus, a range of measures related to feasibility and effectiveness were included as outlined below:

Accessibility

Demographic profiles – age, gender, family composition, parental employment and socioeconomic status as indicated by deprivation indices (Citation30).

Brain injury and clinical profiles – the nature of the brain injury, educational status and severity of incurred disability at the time of project participation, as measured by the King’s Outcome Scale for Childhood Head Injury (KOSCHI) (Citation31). This was chosen as a specific measure of negative outcome severity following childhood brain injury, rather than generic developmental functioning. Given this was the chronic phase of recovery for these children, this measure of current severity, in terms of disability outcomes, was deemed to be a more useful measure than historical coma scale scores. The authors report good construct validity for the scale. Mild, moderate and severe levels of KOSCHI disability classifications were used. These were based on levels of independence and the presence, or not, of physical, cognitive and psychosocial difficulties (Citation31).

Number and nature of service contacts and services accessed.

Acceptability

Families who had engaged (for more than one session) with the project over the previous year (n = 21) were invited to participate in an in-person focus group, or online individual interviews using a video-conferencing platform. Seven parents (all mothers), who were able to attend the focus group (n = 2) or interviews (n = 5) within the time frame possible, consented. All were white UK/Irish mothers and most (6/7) were in two-parent households. Interviews were conducted by two of the authors who had not been involved in delivering the interventions (CMC and NR). Both the interviews and the focus group began by asking parents about their experience of FF (‘I’m interested in your experience of participation in Family First. What was that like?’). Follow-up probe questions followed the narrative which unfolded but prompted for both positive and negative experiences if such were not naturally forthcoming. Interviews were recorded and transcriptions were anonymized. Reflexive thematic analysis was used by the same two authors to synthesize the data (Citation32–34) as outlined below.

Friends and Family Test (Citation35) – this simple measure has been used in the UK National Health Service (NHS) to evaluate patient experience of a range of services. It asks whether clients would recommend the service to friends or family, if experiencing similar difficulties, and normative data summarize the percentage of respondents who would ‘strongly recommend’ the service minus those who would not recommend or who have no opinion either way. Comparison data for related NHS services were available (Citation35). All families, who participated over the life of the project, were invited to complete this measure.

Effectiveness

A number of standardized clinical measures were conducted at baseline and at completion of participation (or at 6 months if longer term involvement). Whilst, both parent and child informant data were collected, and whilst data from a further 6-month period were collected, only maternal data at project completion will be reported in the current paper due to insufficient numbers and returns in other datasets. Although we did not formally elicit participant feedback on measures completed, the return rate across measures will be considered as pertinent to this issue. Final measures utilized here included:

Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) (Citation36) – competency and problem behavior scales – completed by parents. The CBCL is a well-validated measure used to assess behavior problems and social competencies in children (Citation36), including in studies of behavioral outcomes in children with ABI (Citation2–4,Citation13).

Pediatric Quality of Life Scale (PedsQL 4.0) (Citation37) – the ‘psychosocial,’ ‘physical health’ and ‘family functioning’ subscales were used. This has been a well-validated tool to measure quality of life in children with chronic illnesses and their families (Citation37) with good psychometric properties specifically noted for children with brain injury (Citation38).

Goal attainment scaling has been highlighted as a sensitive and valid way to measure progress on achievement of individual goals in brain injury rehabilitation (Citation39). We adopted this methodology in terms of formulation of goals with families at the start of project participation. Goals were formulated in SMART terms – specific, measurable, achievable, realistic and time-limited. However, we adapted scaling for ease of understanding from a −2 to +2 continuum, to a simple 1–10 scaling, to measure proximity to agreed goal attainment at the start of participation and at discharge.

Data analyses

Accessibility data related to family characteristics and clinical features of the child was summarized in terms of means, standard deviations and ranges (e.g. age data) and in terms of percentages of children/families who fell into different categories (e.g. gender and deprivation quartiles).

Acceptability data was primarily represented by the focus group and individual interviews described above. This was analyzed by two of the authors (NR and CMC) using reflexive thematic analysis, as noted above. Although primarily inductive, this allowed for reflexive deductive codings, relevant here given the premise of the study and the authors’ positions related to the importance of the family for child outcomes. These positions were critically reflected on and mutually challenged through the process of the analysis. For quality assurance purposes, codings and emergent themes for the focus group were independently generated by both authors. These were discussed with respect to personal and contextual processes and assumptions likely to have influenced interpretations. One author (NR) coded all seven individual interview transcripts and formulated thematic patterns. Together, both authors interrogated thematic labels and the alignment of themes to participant quotations. A thematic synthesis, or story of how the themes might be related to each other was formulated.

For our analyses related to effectiveness and the standardized instruments, we examined changes on the ‘Competence’ subscale of the CBCL, together with the ‘Internalizing’ and ‘Externalizing’ index scores of the ‘Problem’ subscales, as the ‘Total’ score masked important variations across both sets of behavioral difficulties. We evaluated the ‘Physical’ and ‘Psychosocial’ subscales of the PedsQOL 4.0 separately, rather than the merged total score, as again each domain appeared to vary differentially. The ‘Family Functioning’ subscale of the PedsQOL 4.0 was also utilized.

Return rates for the questionnaires varied, especially at the follow-up period. Moreover, there were missing values across the questionnaires (ranging from 1 to 37) which sometimes prohibited sub-scale calculations. Informed by recommended practice (Citation40), we first checked if missing values accounted for more than 5% but less than 25% of the cases; we then checked if such had occurred in a random fashion, by comparing missing value cases to cases without missing values on relevant other scales (e.g. baseline scores on the same and related scales). If both conditions were met, we used the series mean to manage the missing values. This condition was only met on two subscales – ‘Competence (n = 4/19 at post-intervention) and ‘Family Functioning’ (n = 13/55 at post intervention). For all other scales, we had to only perform pre – post analyses where we had complete pre- and post-intervention responses. Numbers included in each specific analysis were reported. Responders at follow-up did not differ statistically from non-responders at baseline assessment on the same scales (p > 0.05). The numbers included for each analysis varied, therefore, from 19 to 55 as outlined in . Normality assumptions were met for all scales and only two outliers (more than two standard deviation divergence from series mean) were identified for exclusion. Paired sample t-tests were used to compare pre- and post-scores.

In terms of our goal attainment measure, we used an adapted Likert 1–10 scale as noted above. Numbers represented proximity to goal attainment with ‘10’ representing complete goal attainment. Data were available for 50 families who formulated an average of three goals each.

Results

Accessibility

A total of 105 families accessed the service from 2015 to 2022. This was more than 50% above projected targets at project inception. Just over 79% (n = 83) met eligibility criteria and had at least one psychoeducational session, with 69% (n = 72) engaging in longer-term work. Of the 83 families who met eligibility criteria, there was an average of 13 (±1.2) sessions per family. Whilst the range was 1–43 sessions, most (92%) fell within the 1–26 session range. Most contacts were one-on-one home visiting, or online sessions, but 13% of families attended one or more group sessions. School consultations took place for 45% of families. When three outliers were excluded (greater than two standard deviations above the mean), there was an average of 3.8 (± 0.4) consultations with health, social care and educational professionals and services per family (range = 0–18).

Northern Ireland is the smallest devolved nation of the UK with a population of 1.9 million with about 20% under 15 years of age (Citation41). Over a third of the population live in the Belfast metropolitan area in the east of the region and many specialist health services are located in this area. However, uptake and engagement came from right across the region, and beyond the metropolitan area, with the highest healthcare sector proportion (38%) coming from the normally most hard to reach, more rural, area in the west of the region.

summarizes the demographic and clinical characteristics of those families who participated in the project. These were children in the chronic phase of recovery whose mean age was 7.7 years at project access, but whose brain injury had typically occurred some 4 years previously – at mean age of 3.6 years. Most were male children, consistent with the gender demography of brain injury in childhood. Rates of parental unemployment and lone parent status were high and almost 40% came from the lowest deprivation quartile. Accessibility for typically harder to reach families was, thus, good.

Table 2. Family characteristics and child clinical features.

A range of mechanisms of brain injury were reported, although traumatic brain injury accounted for just under half (46%) of all cases as outlined in . The majority of children who accessed the project had at least ‘moderate’ levels of disability, as classified by the KOSCHI classification system (Citation31). This category describes children who, although mostly independent for daily living skills, have overt problems of a physical, cognitive or psychological nature including learning and behavior difficulties. Co-morbid diagnoses were recorded for some cases as outlined in . Learning disability (21%) and epilepsy (18%) were the most common. Previous, or current, involvement with other community services (e.g. community pediatrics, speech and physiotherapy) was evident in over half of the sample. Of those children in the sample at school age, 82% were attending mainstream school. The remaining 18% were in special needs education or a special needs class within mainstream school. Of all children, a statutory educational statement, for special educational needs following the brain injury, was in process for almost half (47%). This is a formal report, compiled by educational and health professionals, which outlines the nature of a child’s disabilities and needs, and recommended adjustments required. A further 17% were in receipt of specific school supports short of a formal statement. Together, these data suggest children and families in significant need had accessed the project.

Acceptability – family experience of the project

The seven mothers who engaged with the focus group were parents of children of comparable age (6.7 years) and spread of brain injury mechanisms (traumatic brain injury, infection, stroke and tumor) as in the wider sample. Thematic analysis identified four superordinates and four sub-themes which are summarized in . This graphic identifies a putative relationship between themes – first in terms of the perceived uniqueness and accessibility of the project and then the perceived experiences and benefits derived through participation.

Underpinning parents’ experience of participation in the FF program was the recurrent theme ‘Nothing else like this out there’. Participant 6, for example, noted ‘It’s a one stop hub. There is nothing else like it out there’. Associated reports spoke of specialist knowledge and understanding, not typically found in generic community services. Amplifying appreciation of this availability was perceptions of an accessible and flexible intervention (see ). This was both in terms of timely interventions post-referral, but also in terms of outreach and media of engagement – the home visiting program and the teletherapy that occurred post-COVID. Participants 1 and 7 for example noted:

‘ … the fact that they came to us. And you weren’t trying to get somewhere else and you weren’t trying to fit that in’

… the (videoconferencing platform) meetings have been a lifesaver over COVID

Two additional themes related to parental experience of the interventions themselves. An ‘Empowerment’ theme was evident across participant data. This related to the benefits from knowledge acquired through project participation (‘Armed with knowledge’ sub-theme), both for themselves, but also in relation to their capacity to advocate for their child. The development of new ways of coping with challenges posed by ABI was also evident (‘Coping strategies’ sub-theme). Participant 3, for example, noted:

Having knowledge, information and understanding from Family First was just so powerful for us … and being able to pass that along to others around us so that they could try their best and maybe take a different approach to how they were dealing with our son. (Participant 3)

Participants 1 and 2 gave both general and specific examples of coping strategies developed to manage school anxiety and general child adjustment difficulties:

There were times when my child was more anxious and maybe school wasn’t going that well. The Family First staff member used the remote control of the X-box, to sort of give my child ideas of how to control their emotions and how to handle things. It was great

… there were techniques and skills that we would have learned from our interactions with Family First, that were just game changers really

Finally, analyses suggested a ‘Family affair’ theme, consistent with a family-focused intervention. The ‘Whole family support’ sub-theme reflected appreciation of the whole family being included in interventions as expressed, for example, by Participant 4 – ‘I have three children at home, so it was about getting to know the whole family, and they were included which was amazing’. A related, but distinct sub-theme, was ‘Linking with other families’, which reflected a sense of connection with other families facing a similar challenge. Participant 5, for example, noted ‘There was a lot of things that … we could all (a group of families) relate to…and I find that to be a really good source of support as well”.

In addition to these qualitative data from a subgroup of parents, all families were asked to complete the single-item Friends and Family Test (Citation35) as outlined above. Data were returned from 41 respondents. In sum 94% of these parent respondents suggested they were ‘extremely likely’ and 6% ‘likely’ to recommend the Family First program to friends or family in a similar situation. Contemporary data on the NHS England website (Citation35) for comparator community/mental health services suggested recommendation figures of 86%−93%. This benchmarking suggested high levels of acceptability for the FF program in our overall sample.

Effectiveness

The 72 families who participated in more than one session of the project were asked to complete the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) and the Pediatric Quality of Life (PedsQL 4.0), together with the ‘Family Functioning’ module of the latter questionnaires as outlined above.

summarizes changes on each scale, together with effect size differences, based on Cohen’s criteria (Citation42), and levels of statistical significance. As noted above, data was returned for between 19 (‘Competence’ subscale of the CBCL) and 55 (‘Family Functioning’ subscale of the PedsQL 4.0) pre- post-intervention pairs across the factors of interest. Families in these data analyses had all attended more than one session (means varied from 15 to 16 sessions for these subsamples), and there were no differences between responders and non-responders in terms of number of parents at home, parental employment, parental education and severity of disability (p > 0.05).

Table 3. Pre- and post-scores on standardized outcome measures.

The first point of note is that, based on parent informant scales, mean scores for these children were in the ‘caseness’ or ‘at risk’ range of both the CBCL and PedsQL 4.0, in terms of CBCL ‘Competence’ (social, academic and activity domains), ‘Internalizing’ and ‘Externalizing’ emotional-behavioral difficulties and ‘Physical’ and ‘Psychosocial’ (emotional, school and social domains) quality of life (Citation36,Citation37). The ‘Family Functioning’ quality of life mean was also distinctly below reference group norms for community samples (Citation37).

No changes across time were evident on parent reports of ‘Internalizing’ behaviors. However, at discharge from the project, gains had been reported on the ‘Competence’ and ‘Externalizing’ index scales for the CBCL, and on all domains of quality of life. Cohen’s d effect sizes (Citation42) ranged from small (‘Family Functioning’ index) to large (‘Psychosocial’ quality of life index).

As noted above, interventions in the FF project were delivered with respect to goals formulated with the families at project admission. Data were available for 50 families who formulated mostly three goals each. highlights that proximity to goal attainment increased, across the 155 goals formulated, from a mean of 2.2 (±1.6) at project entry to 6.5 (±2.3) at project discharge. This increase was statistically significant at p < 0.001 with a large effect size.

Discussion

The ‘Family First’ (FF) intervention program has been innovative in weaving together family-focused interventions with interventions in other systems of influence (schools and health and social care). A community outreach program, delivered through home-visiting and teletherapy media, it has been underpinned by narrative, problem-solving and goal-directed interventions to address problems experienced in the chronic phase of the child’s recovery from brain injuries of multiple etiologies.

Findings suggested the FF program recruited and engaged often hard to reach families, with respect to socioeconomic deprivation, lone parenthood and rural locations. Recruitment was above targets scoped at project inception. Children in significant need accessed the project, as reflected by KOSCHI disability classifications, the proportions undergoing educational statementing, and baseline profiles of psychosocial adjustment difficulties and reduced quality of life for the child and family. Supporting these quantitative data was the qualitative data where the accessibility and flexibility of the project were discerned from the parent narratives. Finally, levels of retention were high, with families engaging for an average of 13 sessions – above the number typically reported in other family-focused interventions with this population (Citation11–15).

Such reach and relevance are encouraging. Qualitative indicators of acceptability were also encouraging. Perceptions of a unique and accessible project underpinned experiences of empowerment, through knowledge and skill transfers and experienced within a whole family sphere of influence (see ). These positive outcomes speak directly to the unmet needs recent studies have suggested are common for families of children with ABI, and especially those in the chronic phase of recovery (Citation17,Citation18).

The effectiveness of the program was gauged in a pilot pre-post evaluation design, utilizing standardized measures related to child psychosocial adjustment and child and family quality of life. Whilst both pre- and post-intervention means, on the CBCL and PedsQL 4.0, were generally discrepant from healthy peer-referenced norms by a standard deviation (Citation36,Citation37), there were statistically significant improvements in child psychosocial competencies and quality of life, and reductions in externalizing behaviors, with typically medium effect sizes. Significant improvements in overall family functioning were also evident (small effect size). Consistent with these changes on standardized scales, were the data related to goal attainment. These were the bespoke family goals, commonly related to family relationships, managing emotions and behavior and school-related functioning. Mean proximity ratings to goal attainment significantly increased with a large effect size. Again, there was a synergy with our qualitative data. Themes related to the acquisition of new coping skills, empowerment and impact on the family as a whole, suggested therapeutic processes underpinning our quantitative outcomes consistent with the project aims.

Limitations and future directions

Our findings should be considered in light of a number of study limitations. Perhaps most fundamentally, we did not have a control group and future evaluation of this program would benefit from such. However, we did see promising gains here and research would suggest such are often unlikely at the chronic stage of recovery (Citation13). Importantly, data from the qualitative arm of the current study were consistent with ascribing changes to the impact of the program. Other limitations, and points for future research, which should be considered in interpreting conclusions include:

The variability in return rates across our different measures of effectiveness. This may tell us something about the feasibility of different measures – e.g. his return rates are the goal attainment and family functioning measure-v- relatively lower return rates on the much longer CBCL. However, although we did show that responders on the various measures did not differ significantly from non-responders on key measures, the potential for bias in such a variable return rates is raised.

Relatedly, the lack of a further follow-up period to assess maintenance of gains and the inclusion of child/father respondent data and observational data, limit our conclusions. Efforts were made to capture respondent data from the children and fathers, but returns were disappointing and insufficient for meaningful analyses. Ways to increase such returns should be sought.

We did not formally assess measure feasibility in this study, although the above comments suggest conclusions about the challenges here.

Whilst we included families of children with multiple ABI etiologies and thus may reach conclusions re applicability of the intervention, we did not break down pathways of traumatic brain in injury. Non-accidental brain injury, for example, is likely to raise specific issues in any family-focused intervention that warrant future consideration.

Our intervention protocol was responsive and iterative as noted above, and we have suggested that this is appropriate for such a feasibility and pilot study. However, despite common core elements, and generally good engagement (mean sessions attended was 13), the variability in sessions attended, and the part tailoring of the interventions, do mean efficacy (-v-effectiveness) cannot be established.

Although the vast majority of school age children were in mainstream education (82%), resources did not permit cognitive profiling of all children who participated in the program. This may be relevant to influencing outcomes and responses to the program, and would be important to investigate, together with other developmental measures, within a larger sample pool and dedicated trial resources.

Finally, our qualitative data was based on a sample of 7 mothers out of the 21 invited to participate in this arm of the study. As we have noted, the sample reflected the overall study sample in terms of age of children and spread of brain injury mechanisms. However, all were white (UK/Irish) and only one was a lone parent. Although sample representativeness was deemed to be more relevant to the quantitative analyses, this degree of sample homogeneity must be considered as context for our findings. It is possible that a greater diversity of demographics would have extended themes discerned.

Findings do suggest this program is promising enough to move toward a funded clinical trial. In addition to addressing the above limitations, an intervention manual would benefit attention to treatment fidelity.

Conclusions

This new, community-based, and systemically informed, intervention for families of children in the chronic phase of recovery following early ABI, has shown promise in this feasibility study and pilot evaluation. Levels of engagement, for often hard to reach families and children with high needs, were impressive. Consistency between quantitative and qualitative data sources and methods suggested high levels of acceptability and perceptions of change and empowerment within the family. Ultimately, outcomes with respect to quality of life, externalizing behaviors and child competencies suggested that the clinical mainstreaming of such a service would have benefits for the child and family, and likely mitigate some of the personal, familial and social costs potentiated by childhood ABI.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Catroppa C, Hearps S, Crossley L, Yeates K, Beauchamp M, Fusella J, Anderson V. Social and behavioral outcomes following childhood traumatic brain injury: what predicts outcome at 12 months post-insult? J Neurotrauma. 2017;34(7):1439–47. doi:10.1089/neu.2016.4594.

- Wade SL, Fisher AP, Kaizar EE, Yeates KO, Taylor HJ, Nanhua Zhang N. Recovery trajectories of child and family outcomes following online family problem-solving therapy for children and adolescents after traumatic brain injury. J Internat Neuropsych Soc. 2019;25(9):941–49. doi:10.1017/S1355617719000778.

- Durber CM, Yeates KO, Taylor HG, Walz NC, Stancin T, Wade SL. The family environment predicts long-term academic achievement and classroom behavior following traumatic brain injury in early childhood. Neuropsych. 2017;31(5):499–507. doi:10.1037/neu0000351.

- Ryan NP, van Bijnen L, Catroppa C, Beauchamp M, Crossley L, Hearps S, Anderson V. Longitudinal outcomes and recovery of social problems after pediatric traumatic brain injury (TBI): contribution of brain insult and family environment. Int J Dev Neuroscience. 2016;49(1):23–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2015.12.004.

- Anderson V, Spencer-Smith M, Wood A. Do children really recover better? Neurobehavioral plasticity after early brain insult. Brain. 2011;134(8):2197–221. doi:10.1093/brain/awr103.

- Ownsworth T, Karlsson L. A systematic review of siblings’ psychosocial outcomes following traumatic brain injury. Dis Rehab. 2022;44(4):496–508. doi:10.1080/09638288.2020.1769206.

- Beauchamp MH, Seguin M, Cagner C, Lalonde G, Bernier A. The PARENT model: a pathway approach for understanding parents’ role after early childhood mild traumatic brain injury. Clin Neuropsych. 2021;35(5):845–67. doi:10.1080/13854046.2020.1834621.

- McCusker CG, Doherty N, Molloy B, Rooney N, Mulholland C, Sands A, Craig B, Stewart M, Casey F. A randomized controlled trial of interventions to promote adjustment in children with congenital heart disease entering school and their families. J Pediatr Psychol. 2012;37(10):1089–103. doi:10.1093/jpepsy/jss092.

- Fedele DA, Hullmann SE, Chaffin M, Kenner C, Fisher MJ, Kirk K, Eddington AR, Phipps S, McNall-Knapp RY, Mullins LL, et al. Impact of a parent-based interdisciplinary intervention for mothers on adjustment in children newly diagnosed with cancer. J Pediatr Psychol. 2013;38(5):531–40. doi:10.1093/jpepsy/jst010.

- Law E, Fisher E, Fales J, Noel M, Eccleston C. Systematic review and meta-analysis of parent and family-based interventions for children and adolescents with chronic medical conditions. J Pediatr Psychol. 2014;39(8):866–86. doi:10.1093/jpepsy/jsu032.

- Renaud MI, Klees C, van Haastregt, van Hassstregt JCM CE, van de Port IG, Lambregts SA, van Heugten CM, van Haastregt JC, van de Port IG. Process evaluation of brains Ahead!: an intervention for children and adolescents with mild traumatic brain injury within a randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehab. 2020;34(5):688–97. doi:10.1177/0269215520911439.

- Hickey LH, Anderson V, Hearps S, Jordan B. Family forward: a social work clinical trial promoting family adaptation following paediatric acquired brain injury. Brain Inj. 2018;32(7):867–878. doi:10.1080/02699052.2018.1466195.

- Garcia D, Rodriguez GM, Lorenzo NE, Coto J, Blizzard A, Farias A, Smith ND, Kuluz J, Bagner DM. Intensive parent–child interaction therapy for children with traumatic brain injury: feasibility study. J Pediatr Psychol. 2021;46(7):844–55. doi:10.1093/jpepsy/jsab040.

- Brown FL, Whittingham K, Boyd RN, McKinlay L, Sofronoff K. Does stepping stones triple P plus acceptance and commitment therapy improve parent, couple, and family adjustment following paediatric acquired brain injury? A randomised controlled trial. Beh Res Ther. 2015;73:58–66. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2015.07.001.

- Wade SL, Gies LM, Fisher AP, Moscato EL, Adlam AA, Bardoni A, Corti C, Limond J, Modi AC, Williams T. Telepsychotherapy with children and families: lessons gleaned from two decades of translational research. J Psychother Integ. 2020;30(2):332–47. doi:10.1037/int0000215.

- Bronfenbrenner U, Morris PA. The bioecological model of human development. In: Damon W, RM L,eds Handbook of child psychology: theoretical model of human development. New York (NY): John Wiley, 2006:pp. 793–828series editorvolume editor.

- Miley AE, Fisher AP, Moscato EL, Culp A, Mitchell MJ, Hindert KC, Makaroff KL, Rhine TD, Wade SL. A mixed-methods analysis examining child and family needs following early brain injury. Dis Rehab. 2022;44(14):3566–76. doi:10.1080/09638288.2020.1870757.

- Minney MJ, Roberts RM, Mathias JL, Raftos J, Kochar A. Service and support needs following pediatric brain injury: perspectives of children with mild traumatic brain injury and their parents. Brain Inj. 2019;33(2):168–182. doi:10.1080/02699052.2018.1540794.

- Rohrer-Baumgartner N, Holthe IL, Svendsen EJ, Roe C, Egeland J, Borgen IM, Hauher SL, Forslund MV, Brunborg C, Ora HP, et al. Rehabilitation for children with chronic acquired brain injury in the child in context Intervention (CICI) study: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2022;23(1):169. doi:10.1186/s13063-022-06048-8.

- Barkham M, Mellor-Clark J. Bridging evidence-based practice and practice-based evidence: developing a rigorous and relevant knowledge for the psychological therapies. Clin Psychol And Psychother. 2003;10(6):319–27. doi:10.1002/cpp.379.

- Koshy E, Koshy V, Waterman H. Action research in healthcare. London: Sage Publications; 2011.

- McCusker CG, Doherty N, Molloy B, Rooney N, Mulholland C, Sands A, Craig B, Stewart M, Casey F. Early psychological interventions in infants with congenital heart disease and their families promote infant neurodevelopment and reduce worry and distress in parents. Child Care Health Dev. 2009;36(1):110–17. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2214.2009.01026.x.

- Besani C, McCusker CG, Higgins A, McCarthy A. A family-based intervention to promote adjustment in siblings of children with cancer: a pilot study. Psycho-Oncol. 2018;27(8):2052–55. doi:10.1002/pon.4756.

- Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, Michie S, Nazareth I, Petticrew M. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new medical research council guidance. BMJ. 2008;337:a1655. doi:10.1136/bmj.a1655.

- Skivington K, Matthews L, Simpson SA, Craig P, Baird J, Blazeby JM, Boyd KA, Craig N, French DP, McIntosh E, et al. A new framework for developing and evaluating complex interventions: update of medical research council guidance. BMJ. 2021;374:n2061.

- Moore GF, Audrey S, Barker M, Bond L, Bonell C, Hardeman W, Moore L, O’Cathain A, Tinati T, Wight D, et al. Process evaluation of complex interventions: medical research council guidance. BMJ. 2015;350(mar19 6):h1258. doi:10.1136/bmj.h1258.

- Eccleston C, Fisher E, Law E, Bartlett J, Palermo TM. Psychological interventions for parents of children and adolescents with chronic illness. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015; 4. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009660.pub3.

- Wade SL, Cassedy AE, Shultz EL, Zang H, Zhang N, Kirkwood MW, Stacin T, Yeates KO, Taylor HG. Randomized clinical trial of online parent training for behavior problems after early brain injury. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2017;56(11):930–9 e2. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2017.09.413.

- Catroppa C, Soo C, Crowe L, Woods D, Anderson V. Evidence-based approaches to the management of cognitive and behavioral impairments following pediatric brain injury. Future Neurol. 2012;7(6):719–31. doi:10.2217/fnl.12.64.

- Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency. Northern Ireland Multiple Deprivation Measure. 2022; [accessed 2022 June 6] www.nisra.gov.uk

- Crouchman M. A practical outcome scale for paediatric head injury. Arch Dis Child. 2001;84(2):120–24. doi:10.1136/adc.84.2.120.

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006 Jan;3(2):77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Braun V, Clarke V. Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qual Res Sport Exerc Health. 2019;11(4):589–97. doi:10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806.

- Braun V, Clarke V. Can I use TA? Should I use TA? Should I not use TA? Comparing reflexive thematic analysis and other pattern-based qualitative analytic approaches. Couns Psychother Res. 2021;21(1):37–47. doi:10.1002/capr.12360.

- NHS England - friends and family test 2022. [accessed 2022 June 28] www.england.nhs.uk/fft

- Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA. Manual for the ASEBA School-age Forms and profiles. Burlington (VT): University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth and Families; 2001.

- Varni J, Burwinkle T, Seid M, Skarr D. The PedsQL™* 4.0 as a pediatric population health measure: feasibility, reliability, and validity. Ambul Pediatr. 2003;3(6):329–41. doi:10.1367/1539-4409(2003)003<0329:TPAAPP>2.0.CO;2.

- McCarthy ML, MacKenzie EJ, Durbin DR, Aitken ME, Jaffe KM, Paidas CN, Slomine BS, Dorsch AM, Berk RA, Christensen JR, et al. The pediatric quality of life inventory: an evaluation of its reliability and validity for children with traumatic brain injury. Arch Phy Med Rehabil. 2005;86(10):1901–09. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2005.03.026.

- Turner-Stokes L. Goal attainment scaling (GAS) in rehabilitation: a practical guide. Clin Rehabil. 2009;23(4):362–70. doi:10.1177/0269215508101742.

- Little RJ, Rubin DB. Statistical analysis with data. 2nd ed. New York (NY): Wiley; 2002.

- Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency. 2021. [accessed 2022 June 28] www.nisra.gov.uk/statistics/census/2021-census

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioural sciences. 2nd ed. England (London): Routledge; 1988.