ABSTRACT

Background

Individuals recovering from stroke often experience cognitive and emotional impairments, but rehab programs tend to focus on motor skills. The aim of this investigation is to systematically assess the change of magnitude of cognitive and emotional function subsequent to a conventional rehabilitative protocol administered to stroke survivors within a defined locale in China.

Methods

This is a multicenter study; a total of 1884 stroke survivors who received in-hospital rehabilitation therapy were assessed on admission (T0) and discharge (T1). The tool of InterRAI was used to assess cognitive, emotional, and behavioral abnormality.

Results

The patients aged >60 years, with a history of hypertension, and long stroke onset duration were more exposed to functional impairment (all p < 0.05). Both cognitive and emotional sections were significantly improved at T1 compared to T0 (p < 0.001). Initially, 64.97% and 46.55% of patients had cognitive or emotional impairment at T0, respectively; this percentage was 58.55% and 37.15% at T1.

Conclusion

Many stroke survivors have ongoing cognitive and emotional problems that require attention. It is essential to focus on rehabilitating these areas during the hospital stay, especially for older patients, those with a longer recovery, and those with hypertension history.

Introduction

Despite advancements in medical care strategies and techniques, the incidence rate and prevalence of stroke remain high (Citation1). In addition to impairments in physical function, the neuropsychiatric sequelae following a stroke present significant challenges for patients, resulting in varying degrees of short- or long-term mental distress (Citation2). The prevalence of post-stroke cognitive impairments (PCI) can vary between 20% and 80%, with post-stroke depression (PSD) exceeding 20% (Citation3,Citation4). Recent research has indicated a potential correlation between the occurrence of COVID-19, a global pandemic, and stroke. Given the significant psychological impact of COVID-19 beyond its physical effects, it is crucial in the aftermath of the pandemic to prioritize the emotional and cognitive recovery of vulnerable populations.

Unfortunately, emotional or cognitive disorders of patients after stroke are given less attention than physical health disorders (Citation5). While the association between cognition and motor function is well established, the majority of studies tend to prioritize motor function over neuropsychiatric aspects. For instance, a search on a prominent academic website in PubMed (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/) yielded over 100 papers in the past 3 years with titles containing ‘stroke, review, and motor,’ compared to less than 40 papers when the keywords of motor were modified to cognition, mental, or emotion. In fact, patients with mild impairments who are discharged home often experience similar cognitive and emotional challenges as those with severe impairments who remain in inpatient rehabilitation (Citation6). Mental health disorders have a similar or greater effect on patients’ quality of life compared to physical health disorders (Citation7). Therefore, PCI and PSD should receive more attention from clinicians (Citation8).

Although the assessment were process together at the admission, the management of emotional problems is often separated from cognitive rehabilitation for stroke patients (Citation9). This is due to no specific emotional management technique appears to be effective for stroke survivors, other than pharmacological interventions (Citation10). A meta-analysis of 1,972 post-stroke patients with depression reported uncertain evidence of the usefulness of cognitive behavioral therapy (Citation11). A recent randomized controlled trial using reminiscence therapy to treat cognitive disorders, anxiety, and depression in stroke patients showed that cognitive and emotional problems were reduced in the intervention group (Citation8). In other words, there is little evidence regarding successful complex interventions for both PSD and PCI after stroke. However, although the success rates of management of both PSD and PCI were so small, rarely research conducted in the rehabilitation department have investigated the effect of standard hospitalization rehabilitation on cognition and emotion, except for the targeted intervention study (Citation8).

Hence, this study aimed to conduct a multicenter investigation in a specific region on China to a comprehend the extent of cognitive and emotional improvement among stroke patients undergoing inpatient rehabilitation. Furthermore, to identify potential influencing factors that could serve as a basis for subsequent functional enhancement.

Methods

Participants

Patient selection

Between October 2019 and February 2021, patients with a diagnosis of post-stroke-related functional impairment who were undergoing inpatient rehabilitation in one of the participating institutions in Yunnan province were included in this study. All of the patients treated by the alliance institutions were managed by international resident assessment instruments (InterRAI) series assessment including InterRAI-post acute care, InterRAI- health care, and InterRAI- long term care facilities. Our study screened these institutions’ medical records, and incomplete records were excluded. Each individual as assigned unique ID number, and duplicated data were also excluded. A total of 1884 post-stroke patients admitted to the rehabilitation department of 10 hospitals in several main cities of Yunnan province were included in this study.

Study design

This study was conducted retrospectively. General information including age, sex, marital status, time since stroke onset, and complications of hypertension (HTN) and/or diabetes mellitus (DM) were collected to analyze the differences between functional impairment and onset condition. The medical records from the admission assessment (T0) and discharge assessment (T1, 14 days later) were collected for analysis. The delta score between admission and discharge was also calculated for comparison of the change of function according to different characteristics.

The InterRAI assessment used in China was modified with permission from Qinghua University, China, and used under license. Data were retrospectively collected from medical records and informed consent was waived for this study. The alliance institution hospital review board approved this study (IRB No. PJ-2019-04).

InterRAI sections C and E

We were interested in the characteristics of cognitive and mental health changes in patients with stroke. Therefore, Sections C and E of the InterRAI assessments, which include seven items with 30 small checkup questions, were used for assessment in this study. These items covered cognitive, depression, anxiety, and behavioral domains (One question, C5- “Change in decision making as compared to 90 days ago (or since last assessment if less than 90 days ago) was excluded from the current study because it was not included in all the assessments). The scores for the seven items were calculated using the sum of the 30 subordinate questions. A score of more than one point for any domain indicated impairment, so higher scores indicated worse damage; the coding and points are shown in supplementary data (Supplemental Table S1).

Intervention

Patients received no specific interventions except for conventional physical therapy. Conventional physical therapy included physical, occupational, or other therapies related to the initial individual assessment outcomes (5–6 times per week) for 14 days.

Statistical analysis

All data analyses were conducted using SPSS Statistics software version 26 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). The demographic data are presented as mean ± standard deviation and percentage. The normal or abnormal cases for every domain at every assessment were used in the crossover test, and the scores before and after for every domain were analyzed using paired t-test or Wilcoxon test. The participants were divided into subgroups based on sex, age, and duration since stroke onset. The intergroup analysis was performed using the independent t-test or Mann-Whitney U-test, and the Kruskal – Wallis test was used for subgroup analysis. The statistical tests were two-tailed with p < 0.05 denoting statistical significance. p < 0.01 denoted statistical significance for the subgroup analysis (0.05/5).

Results

In total, 1884 patients’ datasets were collected for analysis. To see if there were objective conditions that would affect cognition and emotion, we added a comparison of patients’ conditions with an indicator of cognitive/emotional abnormalities. shows the median sex, age, height, weight, marital status, and time from stroke onset of the participants. This included patients with comorbid HTN (n = 1096) and DM (n = 152), as previous studies have shown that most stroke patients have these two underlying conditions (Citation12,Citation13).

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of the participants.

Stroke patients with a history of HTN, aged >60 years, and long duration after stroke were more likely to have an emotional impairment (p < 0.05). Those with long duration after stroke were more likely to have cognitive impairment (p < 0.05) ().

Table 2. Sub-group analysis of the impairment cognition and emotion based on demographic characteristics.

At the admission assessment, 64.97% and 46.55% of the patients showed cognitive and emotional abnormalities. More than 39.33% (741 cases) of patients showed both cognitive and emotional impairments; the percentage was 29.35% (553 cases) on the discharge assessment ().

Table 3. Patients with cognitive or emotional abnormalities on admission and discharge.

The total scores for sections C and E were decreased at T1 relative to T0 (lower scores indicate better function) (p < 0.05). The patients showing cognitive abnormalities (all of the C series) at T0 had decreased scores at the T1 assessment (p < 0.05). The E1 and E2 scores were significantly decreased at T1 relative to T0 (p < 0.05). No change was observed in the score of E3 between the two assessments (p > 0.05) ().

Table 4. Effect of hospitalization on cognition and emotion on admission and discharge.

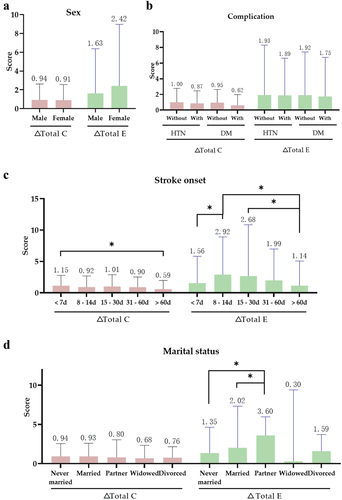

The total change of the delta scale in the cognitive and emotional assessment was different according to demographic characteristics. The Δtotal C was significantly increased in patients with stroke onset < 7d compared with > 60 d (p < 0.01). The Δtotal E was also different between different stroke onset duration (p < 0.01). Moreover, the △total E also increased significantly in the patients’ who lived with partners than those who were married or never married (p < 0.01) ().

Figure 1. The improved cognitive and emotional function during hospitalization based on demographic characteristics.

A. Change of cognition and emotion in different gender; B. Change of cognition and emotion according to complicated with HTN or DM; C. Change of cognition and emotion according different stroke duration; D. Change of cognition and emotion according to marital status.

Abbreviations: C, cognition score; E, emotional and behavior score; Δ Total C = total score of C (on admission assessment) – total score of C (on discharge assessment); Δ Total E = total score of E (on admission assessment) – total score of E (on discharge assessment); HTN, hypertension; DM, diabetes; a higher score indicates more impairment. *p < 0.01.

Discussion

We wanted to determine whether patients’ cognitive and emotional status was given sufficient attention during inpatient rehabilitation, and conducted a large, multicenter retrospective study of stroke patients in inpatient rehabilitation in Yunnan, China, which is unprecedented.

Of 1884 patients, 1224(64.96%) participants were assessed upon admission and identified to have at least one type of cognitive impairment-related issue. Among the participants, 1073 (56.95%) had one or more abnormal emotional and behavioral scores for the domains: ‘indicators of possible depression, anxiety, or sad mood,’ ‘self-reported mood,’ or ‘behavioral symptoms.’ The impairments related to ‘self-reported mood’ were the most common in the emotion domain, and those related to behavior were the least. The prevalence of cognitive and emotional impairments in this study differed from those reported in previous studies (Citation7,Citation14,Citation15). Previous studies have noted that more than 74% of post-stroke patients have depressive symptoms, whereas more than 52% have anxiety symptoms; however, the results of our study were lower than previous reports that separately evaluated the cognitive and affective domains (depression, anxiety, and other pathological symptoms) (Citation16). They reported that 67% of post-stroke patients had cognitive difficulties, and approximately 43% had emotional impairment (Citation17). At the time of trial design, we worried that the possible excess prevalence would be reported due to the use of Inter-RAI, which may make it easier to define as depression. Moreover, data in this study must be compared with caution because the requirement for participation in the previous cohort study was having a first-ever mild stroke. We did not investigate whether the patients in our study had recurrences, and our prevalence may be underestimated.

The severity of functional impairment and disease course in stroke patients may be closely related, suggesting that although the disease course is long after stroke, patients who still require inpatient treatment may have more disabilities, but the recovery characteristics of different types of disabilities may vary (Citation18). Our study revealed variations in the rates of emotional and cognitive impairment at different time points following stroke onset. Specifically, cognitive function shows notable improvement during the later acute phase, highlighting a significant disparity in cognitive recovery between acute and chronic phases. Conversely, emotional recovery demonstrates swifter progress solely in the later acute phase, with no substantial enhancements observed in either the acute or chronic phases. The trends we report are congruent with those reported in the recent literature review that the symptoms of depression increase and decrease progressively with time, which its therapeutic efficacy and preventive effects are not satisfactory (Citation19,Citation20).

Upon conducting the time of discharge assessment, a total of 1103 (58.55%) participants were observed to exhibit persistent cognitive-related issues, while 700 (37.15%) participants continued to report experiencing emotional-related problems. Some studies have suggested that PSD ‘Is strongly associated with the experience and consequences of the stroke itself.’ Emotional distress also has a negative influence on cognitive function (Citation21). Although the majority of patients in our study showed significant improvement in cognition or depression after 14 days of treatment, the proportion of patients with concomitant cognitive and mood disorders, which was 39.33% at admission, remained at a high level than other research at discharge (Citation22). The management of depression has traditionally been distinct from cognitive rehabilitation (Citation9,Citation23), with antidepressant medications commonly prescribed, as in our study. It may also explain the high proportion of depression cases at discharge in this study. Other alternative intervention approaches may be more effective in depression; a recent review suggests that integrating psychological, behavioral, and somatic interventions shows promise in enhancing outcomes for individuals with depression and neurocognitive disorders (Citation24).

Furthermore, our study revealed that emotional disorders in the majority of patients following a stroke are often accompanied by cognitive impairment. Regrettably, there is a possibility that a considerable number of patients who have improved function and have been discharged from departments other than rehabilitation may have been overlooked in our analysis. It is unclear whether these individuals experienced mild emotional and cognitive impairments, as clinically diagnosing cognitive impairment associated with minor depression can be easily overlooked despite its significance (Citation9).

Existing literature suggests that factors beyond disability, quality of life, and mortality may contribute to depression in stroke patients (Citation25). Our research indicates that marital status differences may impact the extent of improvement in mood disorder scores among patients. Specifically, unmarried individuals demonstrated significantly less improvement in mood disorders compared to those who cohabitated with a partner, and married patients also exhibited less improvement than those who lived with a partner. Importantly, this study is the first to identify such a relationship. Additionally, older patients may show a higher propensity for mood disorders, particularly those with concomitant hypertension, as indicated by Tseng et al. (Citation26).

Abnormal behavior may be considered among neuropsychiatric symptoms such as aberrant motor behavior (Citation22). Section E of the InterRAI behavioral symptom assessment is not a neuropsychiatric assessment in the strictest sense; however, we found that the items of the E3 section, which include items like ‘wandering,’ ‘verbal abuse,’ and ‘socially inappropriate or disruptive behavior’ were close to psychiatric abnormalities. Because we could not exclude a previous history of psychiatric disorders, some abnormal behaviors were not emphasized in this study.

Considering that the duration of our study spans a high epidemic of a global disease, COVID-19, which may lead to cognitive and emotional abnormalities (Citation27), we conducted a comparison of studies utilizing the interRAI assessment to evaluate cognitive changes associated with COVID-19 infection. The results of these studies indicate a notable decrease in cognitive scores during COVID-19, suggesting that individuals affected by the virus may experience heightened cognitive difficulties (Citation28). However, because this was a retrospective study, it was challenging to collect prospective data on whether these patients had been previously infected with COVID-19 and exclude the effects caused by it.

The results of the current study are not very promising. However, we must consider that patients have limited time to receive rehabilitation therapy in the hospital. Additionally, most patients and caregivers focus more on physical recovery than cognitive, mental, or behavioral issues. This is a crucial area for future research. Interventions should aim to address various functional impairments, and medical staff should receive appropriate training. Furthermore, management strategies should be tailored to the unique characteristics of each patient.

Study limitations

Our study did not exclude patients with a history of preexisting cognitive or mental disorders before the onset of stroke. Consequently, the prevalence of such disorders might have been overestimated in our report. To evaluate the effectiveness of in-hospital rehabilitation therapy in treating cognitive, emotional, and behavioral dysfunctions, we employed the InterRAI method. We refrained from including other functional data, such as motor, nutrition, communication, and daily activity, as their inclusion could have hindered our focus on the items of interest. Nonetheless, we did not control for confounding factors such as diverse brain lesions and educational attainment. Future studies should address these factors and minimize potential bias.

Conclusion

A large proportion of stroke survivors presented with cognition and emotional issues in Yunnan province, which is influenced by age, hypertension, and disease duration. While most patients with concomitant functional impairment recover well, many still experience unresolved cognitive and emotional problems at the time of discharge. Therefore, rehabilitation programs should focus on cognitive and emotional rehabilitation along with physical rehabilitation to ensure the overall well-being of stroke patients.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the Kunming Medical University. This is a medical record-based study and informed consent was waived for this study. We confirm that all methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author (Liqing Yao) on reasonable request.

Authors’ contributions

Conceptualization, L.H.J.; Methodology, L.H.J., T.Y.; Statistical analysis: L.H.J., T.Y.; Data curation, Z.Y., Y.H.; Data interpretation: L.H.J., T.Y.; Writing – original draft preparation, L.H.J. T.Y.; Writing – review and editing, L.Q.Y. Funding acquisition, L.Q.Y. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Health Commission of the Yunnan province and a dozen rehabilitation center in Yunnan province for support during data collection.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Yang Y, Huang X, Wang Y, Leng L, Xu J, Feng L, Jiang S, Wang J, Yang Y, Pan G, et al. The impact of triglyceride-glucose index on ischemic stroke: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2023, 22(1):2. doi:10.1186/s12933-022-01732-0

- Robinson RG. The clinical neuropsychiatry of stroke: cognitive, behavioral and emotional disorders following vascular brain injury: Cambridge University Press; 2006.

- Noh Y, Ahn JH, Lee J-W, Hong J, Lee T-K, Kim B, Kim S-S, Won M-H. Brain factor-7® improves learning and memory deficits and attenuates ischemic brain damage by reduction of ROS generation in stroke in vivo and in vitro. Lab Anim Res 2020, 36(1):1–9.doi:10.1186/s42826-020-00057-x

- Terroni L, Sobreiro MF, Conforto AB, Adda CC, Guajardo VD, MCSd L, Fráguas R, Fráguas RJD, neuropsychologia: association among depression, cognitive impairment and executive dysfunction after stroke. 2012, 6:152–57. Dement Neuropsychol 3 doi:10.1590/S1980-57642012DN06030007

- D’Souza CE, Greenway MR, Graff-Radford J, Meschia JF. Cognitive impairment in patients with stroke. In: Seminars in neurology: 2021: thieme medical publishers, inc. 333 seventh avenue, 18th floor. New York, NY; 2021. p. 075–084.

- Slenders JPL, Verberne DPJ, Visser-Meily JMA, Van den Berg-Vos RM, Kwa VIH, van Heugten CM: Early cognitive and emotional outcome after stroke is independent of discharge destination. J Neurol 2020, 267(11):3354–61. doi:10.1007/s00415-020-09999-7

- Investigators EM, Alonso J, Angermeyer M, Bernert S, Bruffaerts R, Brugha T, Bryson H, de Girolamo G, de Graaf R, KJAPS D, et al. Disability and quality of life impact of mental disorders in Europe: results from the European Study of the Epidemiology of mental disorders (ESEMeD) project. 2004, 109:38–46. Acta Psychiatr Scand s420 doi:10.1111/j.1600-0047.2004.00329.x

- Robinson RG, Jorge RE. Post-Stroke Depression: A Review. Am J Psychiatry 2016, 173(3):221–31. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.15030363

- Ferro JM, Santos AC. Emotions after stroke: a narrative update. Int J Stroke 2020, 15(3):256–67. doi:10.1177/1747493019879662

- Wang SB, Wang YY, Zhang QE, Wu SL, Ng CH, Ungvari GS, Chen L, Wang CX, Jia FJ, Xiang YT. Cognitive behavioral therapy for post-stroke depression: a meta-analysis. J Affect Disord 2018, 235:589–96. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2018.04.011

- Cipolla MJ, Liebeskind DS, Chan S-L. The importance of comorbidities in ischemic stroke: impact of hypertension on the cerebral circulation. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2018, 38(12):2129–49. doi:10.1177/0271678X18800589

- van Sloten TT, Sedaghat S, Carnethon MR, Launer LJ, Stehouwer CDA, van Sloten CD. Cerebral microvascular complications of type 2 diabetes: stroke, cognitive dysfunction, and depression. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2020, 8(4):325–36. doi:10.1016/S2213-8587(19)30405-X

- Huang J, Zhou FC, Guan B, Zhang N, Wang A, Yu P, Zhou L, Wang CY, Wang C. Predictors of Remission of Early-Onset Poststroke Depression and the interaction between Depression and cognition during follow-up. Front Psychiatry 2018, 9:738. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00738

- Schottke H, Giabbiconi CM. Post-stroke depression and post-stroke anxiety: prevalence and predictors. Int Psychogeriatr 2015, 27(11):1805–12. doi:10.1017/S1041610215000988

- Vlachos G, Ihle-Hansen H, Bruun Wyller T, Braekhus A, Mangset M, Hamre C, Fure B. Cognitive and emotional symptoms in patients with first-ever mild stroke: the syndrome of hidden impairments. J Rehabil Med 2021, 53(1):jrm00135. doi:10.2340/16501977-2764

- Bhattacharjee S, Al Yami M, Kurdi S, Axon DR. Prevalence, patterns and predictors of depression treatment among community-dwelling older adults with stroke in the United States: a cross sectional study. BMC Psychiatry 2018, 18(1):130. doi:10.1186/s12888-018-1723-x

- Ayerbe L, Ayis S, Wolfe CD, Rudd AG. Natural history, predictors and outcomes of depression after stroke: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry 2013, 202(1):14–21. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.111.107664

- Yetim E, Topcuoglu MA, Yurur Kutlay N, Tukun A, Oguz KK, Arsava EM. The association between telomere length and ischemic stroke risk and phenotype. Sci Rep 2021, 11(1):10967. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-90435-9

- Almeida OP. Stroke, depression, and self-harm in later life. Curr Opin Psychiatry 2023, 36(5):371–75. doi:10.1097/YCO.0000000000000882

- Karaahmet OZ, Gurcay E, Avluk OC, Umay EK, Gundogdu I, Ecerkale O, Cakci A. Poststroke depression: risk factors and potential effects on functional recovery. Int J Rehabil Res 2017, 40(1):71–75. doi:10.1097/MRR.0000000000000210

- Morimoto SS, Kanellopoulos D, Manning KJ, Alexopoulos GS. Diagnosis and treatment of depression and cognitive impairment in late life. Ann NY Acad Sci 2015, 1345(1):36–46. doi:10.1111/nyas.12669

- Mallo SC, Ismail Z, Pereiro AX, Facal D, Lojo-Seoane C, Campos-Magdaleno M, Juncos-Rabadan O, Abbate C. Assessing mild behavioral impairment with the mild behavioral impairment-checklist in people with mild cognitive impairment. J Alzheimer’s Dis 2018, 66(1):83–95. doi:10.3233/JAD-180131

- Bingham KS, Flint AJ, Mulsant BH. Management of Late-Life Depression in the context of cognitive impairment: a review of the recent literature. Curr Psychiatry Rep 2019, 21(8):74. doi:10.1007/s11920-019-1047-7

- Mole JA, Demeyere N. The relationship between early post-stroke cognition and longer term activities and participation: a systematic review. Neuropsychol Rehabil 2020, 30(2):346–70. doi:10.1080/09602011.2018.1464934

- Tseng T-J, Wu Y-S, Tang J-H, Chiu Y-H, Lee Y-T, Fan I-C, Chan T-C. Association between health behaviors and mood disorders among the elderly: a community-based cohort study. BMC Geriatr 2019, 19:1–14. doi:10.1186/s12877-019-1079-1

- Haddad MM, Uswatte G, Taub E, Barghi A, Mark VW. Relation of depressive symptoms to outcome of CI movement therapy after stroke. Rehabil Psychol 2017, 62(4):509–15. doi:10.1037/rep0000171

- Huang C, Huang L, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Gu X, Kang L, Guo L, Liu M, Zhou X, et al. 6-month consequences of COVID-19 in patients discharged from hospital: a cohort study. Lancet 2021, 397(10270):220–32. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32656-8

- van der Krogt IE, Sizoo EM, van Loon AM, Hendriks SA, Smalbrugge M. The recovery after COVID-19 in nursing home residents. Gerontology Geriatr Med 2022, 8:23337214221094192. doi:10.1177/23337214221094192