ABSTRACT

Background

Despite well-documented benefits of physical activity (PA), people with brain injury face numerous PA barriers. This mixed methods systematic review aimed to summarize barriers and enablers that individuals with traumatic brain injury (TBI) experience when participating in PA.

Methods

Primary studies investigating barriers and/or enablers to PA in adults living with TBI were included. Literature search in MEDLINE, EmCare, Embase, PsychINFO, PEDro, and OTSeeker was initially conducted in December 2021 and January 2022, and updated in June 2022. Methodological quality of the included studies was assessed using Joanna Briggs Institute critical appraisal tools. A customized data extraction form was utilized. Descriptive synthesis was used to summarize the findings.

Results

Twelve studies of various methodological qualities were identified. Barriers to PA included personal issues, changing health status, external factors, lack of support, and lack of knowledge. Identified enablers included personal drivers, social support, professional support, accessibility, and education.

Conclusions

The shared similarities between barriers and enablers across several themes suggest that multiple barriers may be amenable to change. Given the diverse barriers to PA, health professionals should use person-centered, holistic approach with ongoing review and monitoring, when engaging with individuals with TBI.

Background

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) can be defined as alteration in brain function, or other evidence of brain pathology, caused due to an external force (Citation1). Altered brain function is defined as one of the following clinical signs: any period of loss of or decreased level of consciousness; any loss of memory for events immediately before or after the injury; neurologic deficits; and any alternation in mental state at the time of injury (Citation1). It is a silent epidemic that causes death and disability in approximately 69 million individuals each year, resulting in major socioeconomic burden costing upward of $530 billion (AUD) annually (Citation2–4). TBI most commonly affects the young (15–45 years of age), although it is common in elderly as well (due to falls), with lifelong consequences (Citation3). The biopsychosocial impact of TBI is long lasting and requires individuals to adapt and adjust to a new reality of life. These individuals experience a greater risk of chronic neurological, endocrine, and cardiovascular comorbidities and psychiatric conditions, social and emotional behavioral changes, and physical impairments (Citation5).

Rehabilitation is important for long-term management, where the reintegration from hospital to home is a crucial and distinct stage of recovery. During this stage of rehabilitation, families, health professionals, and the community can support individuals with TBI in creating new routines (Citation4). Rehabilitation aims to improve function at home and in the community, offer emotional and social support, treat mental and physical issues, and prevent complications from TBI (e.g., blood clots, breathing problems, pain, etc.) (Citation6). A variety of rehabilitation strategies are used to manage an individual’s specific needs and abilities. These can consist of pharmacological management, use of assistive technology, environmental manipulation, cognitive and behavioral therapies, retraining activities of daily living, pain management, and family education and counseling (Citation7). Physical activity (PA) is a cost-effective, non-pharmacological therapy that has proven beneficial effects on enhancing functional outcomes after injury (Citation8). PA is defined as any bodily movement that requires energy expenditure (Citation9). This includes both exercises (i.e., planned PA) and activities involving bodily movements, such as work (e.g., lifting), housework (e.g., cleaning), active transportation (e.g., cycling), and recreational activities (e.g., gardening), which range from light to vigorous intensities (Citation9,Citation10).

However, PA remains underappreciated as prevention and intervention methods globally (Citation11). This is particularly concerning as physical inactivity causes, and accelerates, chronic diseases (Citation12). The advantages of PA are numerous and extend beyond health. Being physically active significantly improves both physical and mental well-beings, as well as one’s sense of purpose, quality of life, ability to cope with stress, ability to maintain and form healthy relationships, and social connectedness (Citation11). Additionally, PA restores healthy homeostatic regulation of stress, reverses or reduces performance limitations observed in neurocognitive tasks, and produces beneficial change in cerebral blood flow and vascular disease improvement (Citation13). These physiological changes are associated with improved executive function, working memory, mental flexibility, processing speed, and overall cognition (Citation13). Given these benefits, PA is an essential treatment goal in long-term rehabilitation.

While the evidence for PA is strong, individuals with TBI typically spend less than 50 min per week being physically active due to numerous barriers faced by this cohort (Citation14). These include ongoing pain, fatigue and fear, and constrained access to the PA program due to transportation and mobility limitations, cost, lack of modified equipment and time restrictions (Citation12–15). Despite this recognition, to date, there has been limited research on barriers and enablers associated with PA participation for individuals with TBI. Therefore, this mixed methods systematic review aimed to address this knowledge gap by synthesizing current research evidence on this topic, which could then be used to inform future services design and strategies to support individuals living with TBI to increase and maintain long-term PA. The advantages and novelty of a mixed methods systematic review are numerous (Citation16). First, inclusion of diverse methodological approaches results in a comprehensive approach in summarizing all available literature on a topic, aiding in complex decision-making. Second, better understanding of, and explanations about, results in quantitative research from the lens of qualitative research and vice versa. Third, the opportunity to confirm and triangulate findings using various sources of evidence enhances the reliability and accuracy of conclusions.

Methods

This mixed methods systematic review was conducted and reported in line with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 statement (Citation17). The protocol for this review was registered a priori with PROSPERO (CRD42021284516). There were no deviations from the protocol. Ethical approval was not required as systematic reviews summarize existing research, and do not collect original data.

Selection criteria

A preliminary scoping search was first conducted to map the literature and gain an understanding of the review topic. The PCC (Population, Concept, Context) format aided in the development of inclusion and exclusion criteria. Quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods primary studies were included if they involved participants who had experienced a TBI at any stage of lifespan, regardless of the severity of the injury and were aged 18 years and older, and investigated barriers to and/or enablers of PA. Exclusion criteria were studies which included children and adolescents (i.e., under 18 years) or participants with other forms of brain injury, such as an acquired brain injury (e.g., stroke), explored barriers to and enablers of tasks not involving PA, and were other research designs (including literature and systematic reviews, opinions, commentaries, editorials, letters to the editor, and conference presentations). Non-English and non-human studies were also excluded.

Search strategy

Electronic databases including MEDLINE, EmCare, Embase, PsychINFO, PEDro, and OTSeeker were initially searched in December 2021 and January 2022, and an update search was completed in June 2022. As a means of avoiding publication/location bias, gray literature search via Google, relevant organizational websites (e.g., Brain Injury Australia, Brain Injury SA), and pearling was undertaken. The search strategy was developed using a combination of keywords and Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) with application of relevant truncations and Boolean operators: Brian Injuries, Traumatic/OR Craniocerebral Trauma/OR Brain Hemorrhage, Traumatic/OR ((skull OR head OR brain OR craniocerebral) adj (trauma* OR injur*)) AND physical* activit* OR exercise* OR Movement/AND barrier* OR obstacle* OR limit* OR enabler*. As PEDro and OTSeeker have less advanced searching mechanisms, the search strategy was modified to suit individual database search engine. This search strategy was independently validated by an Academic Librarian from the University of South Australia. The search syntax of all databases is included in Appendix A.

Screening

All identified citations were exported into EndNoteTM. After removal of duplicates, the remaining studies were exported to CovidenceTM for title and abstract screening, followed by full-text screening. Three reviewers (CB, SK & EJT) undertook independent screening and in duplicate, with one reviewer (CB) involved in both screening stages. Any discrepancies were resolved by the expert reviewer (SK).

Methodological quality

Two independent reviewers (CB & SK) assessed the methodological quality of the included studies using the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) critical appraisal tools (Citation18) for analytical cross-sectional and qualitative studies. In line with the JBI guidelines, the validity, relevance, and results of a study were assessed and scored with ‘yes,’ ‘no,’ ‘unclear.’ or ‘not applicable’ answers. The JBI tools were modified to provide a numerical rating, whereby, 1 mark was allocated for every ‘yes’ answer, 0 marks were assigned for ‘unclear’ or ‘no,’ and ‘not applicable’ would reduce the total number of assessment criteria. The scores allocated to each study (0 to 8 for cross-sectional studies and 0 to 10 for qualitative studies) provided an overall rating, with a higher score being indicative of better methodological quality.

Data extraction

A customized data extraction form was developed for this review. The form incorporated key elements relevant to the review question, including study author(s), publication year, country of origin, sample size, demographic data (e.g., age, sex, severity, and duration of TBI), data collection methods, themes or codes, and supporting evidence. Data extraction was completed by one reviewer (CB), with independent validation from another reviewer (SK).

Data synthesis

This review included both quantitative and qualitative studies, and aimed to describe factors affecting PA participation, a convergent integrated approach (Citation16) to data synthesis and integration was used. In this process, qualitative and quantitative data were initially extracted and descriptively summarized independently, and subsequently integrated. In the first step of this process, two reviewers (CB & SK) carefully mapped various barriers and enablers that were identified from individual studies. In the next step, these barriers and enablers were then categorized into themes based on similarities in meaning. In the final step, labeling of the higher-level categories (Appendix B) was informed by the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF) framework (Citation19) and previous reviews on similar topics (Citation20). As a means of improving rigor in the synthesis process, the categorization of barriers and enablers and the development of themes were conducted via a consensus approach between three reviewers (CB, SK & EJT), which were then verified by another reviewer who is a practicing clinician in this field (ET).

Results

Literature selection

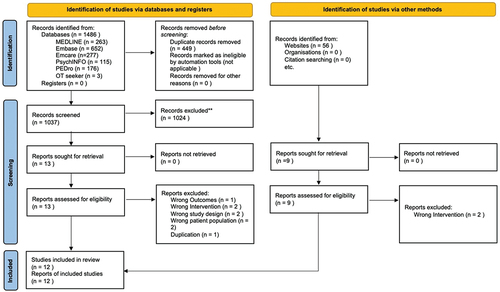

As shown in , the electronic database search yielded 1037 records, of which 1024 were excluded following the title and abstract screening. Of the 13 articles obtained in full text, eight were excluded as they did not meet the inclusion criteria for various reasons, including intervention (n = 2), study design (n = 2), population (n = 2), outcome (n = 1), and duplicate (n = 1). Upon gray literature searching, an additional nine articles went through full-text screening. Of these, seven studies were included and two were excluded due to not meeting the inclusion criteria (intervention). A total of 12 studies were included in this review (11 published studies and one thesis).

Study characteristics

Of the 12 studies included, nine were quantitative (Citation4,Citation21–28) and three were qualitative (Citation12,Citation29,Citation30) studies. The studies were conducted in the United States of America (Citation21–23,Citation26,Citation27,Citation30), Australia (Citation4,Citation12,Citation24,Citation25), Canada (Citation29), and the United Kingdom (Citation28), and were published between 2009 and 2022. A total of 1094 participants were included in these studies, with sample size ranging from 6 to 472 participants. The mean age of these participants ranged from 28 years (Citation30) to 44 years (Citation23). Most studies identified barriers and enablers to PA for individuals who had a severe TBI (Citation12,Citation23–25,Citation29), with one study including moderate-to-severe TBIs (Citation26) and another including minor-to-severe TBIs within the study cohort (Citation30). Additionally, there were various timeframes since TBI had occurred ranging from 1.5 months (Citation24) up to 31 years (Citation29) ().

Table 1. Study characteristics.

Methodological quality

provide an overview of the methodological quality of the included studies. Critical appraisal scores ranged from 2/8 to 6/8 for the quantitative studies. All the quantitative studies used objective measurements to determine the severity of TBI. Most clearly defined the inclusion criteria and described the study population and setting in detail. However, there were some critical methodological flaws. These commonly included a lack of accounting for confounding factors (differences between comparison groups that potentially affect the study results) and associated processes to deal with it. Customized questionnaires were used for data collection, with some studies providing reliability data and no studies providing information regarding the validity of the measures used. All of the three qualitative studies scored 8/10. While many of the criteria were addressed by these studies, common drawbacks were lack of statement identifying the researcher’s theoretical and cultural context, and inconsistency between the research methodology and the representation and analysis of data.

Table 2. Methodological quality assessment of quantitative studies.

Table 3. Methodological quality assessment of qualitative studies.

Barriers to PA participation

Eleven out of 12 included studies revealed barriers to PA participation. These barriers were categorized into five main themes: Personal issues (found in 11 studies), Changing health status (11 studies), External factors (nine studies), Lack of support (four studies), and Lack of knowledge (seven studies) ().

Table 4. Barriers to PA for individuals with TBI.

Personal issues

This theme related to participants’ perception of barriers when participating in PA. A range of emotions such as fear, anxiety, depression, and frustration regarding PA were expressed by participants. In four studies, participants expressed concerns about the consequences of participating in PA, including fear of worsening their condition or re-injury (Citation12,Citation21,Citation26,Citation27). In one study, more than 20% of those aged between 35 and 54 reported a fear of leaving home, which was significantly greater than other age groups (Citation27). Additionally, participants felt frustrated when they were unable to perform tasks or engage in activities that they used to do (Citation12,Citation22). Another two studies also found exacerbated depressive symptoms associated with TBI, due to a compromised sense of self and social identity perceived by participants (Citation4,Citation30).

Findings from several studies suggested that lack of motivation was a major barrier (Citation4,Citation25–28). This was associated with other common barriers including inability to overcome laziness and lack of goals (Citation12,Citation27,Citation30). One participant expressed that their laziness to PA was not related to their TBI (‘I’m very lazy, but it’s not from the crash or the injury, it’s me. I think I was like that before’ (Citation12)). In other cases, participants ceased exercising once they had achieved their rehabilitation goals, as there was no longer anything to motivate them (Citation12).

Lack of structure or discipline, as well as time, were additional barriers (Citation23,Citation25). Across many of the included studies, participants often reported that finding time for PA was difficult, as PA was considered a lower priority in comparison to family, work, and other commitments in their lives (Citation22,Citation23,Citation25). PA participation was also hindered by attitudes and beliefs of participants, including belief of PA being incongruous with aging, regarded PA as a task, and perceived that PA would not benefit their condition and therefore not important for their recovery (Citation12,Citation21).

Changing health status

Given the dynamic and changing nature of TBI, participants’ condition was often exacerbated, leading to a plethora of symptoms which greatly hindered their participation in PA. From the included studies, fatigue was found as a factor influencing participants’ day-to-day commitments (Citation4,Citation25,Citation28,Citation29). One participant stated that ‘if I do that [walk to the next tram stop] before work then I’m too tired when I get to work and I don’t perform, make mistakes’ (Citation12). Another participant also reported that their declined function and weight loss resulted from the time spent in a coma was related to their reduced PA (Citation30).

The quantitative studies further revealed commonly reported factors hindering participants’ ability to perform PA. This included lack of coordination/movement control, mobility, or communication skills, being unable to understand or tolerate PA, loss of balance, limb movement or cognitive function, and increase in pain, dizziness, visual problems, or use of assistive devices (Citation21–23,Citation26,Citation27).

External factors

External factors related to outside influences that impacted participants’ ability to engage in PA. Transportation and accessibility difficulties, environmental barriers, and financial pressures were identified factors negatively influencing PA involvement for participants with TBI. Lack of transportation was reported as a significant barrier (Citation22,Citation23,Citation27,Citation28,Citation30). Due to the changing health status of this population, many participants were unable to drive and therefore would need to walk or rely on public transport for their PA. For example, one participant expressed that ‘[transportation is] always a factor because when I have an appointment somewhere I usually have to leave my house roughly two hours early’ (Citation29). The lack of transportation meant that many facilities were not readily accessible to these participants. Furthermore, access to certain facilities, such as gyms or weight-rooms, was another barrier reported by some participants (Citation21–23,Citation26,Citation27,Citation30).

Additionally, costs associated with accessing facilities and PA programs, as well as perceptions from others in a gym or exercise setting, contributed to anxiety among participants, which resulted in a lack of PA participation (Citation22,Citation27,Citation29). The absence of resources for this cohort was an environmental barrier, as participants reported few facilities had the resources for their PA or were suitable for their participation (e.g., limited day centers or day classes) (Citation12,Citation26,Citation28).

Lack of support

This theme discussed how lack of support and assistance from families, peers, and health professionals hindered PA participation. Families and friends were reported as a barrier when they failed to provide motivational support or care, such as not completing PA with participants or helping participants with their PA (Citation22,Citation28). Additionally, participants felt being a burden on families/friends and stated that they could not constantly ask for help (‘you can ask people to take you, but you get tired of having to ask’ (Citation30)). The absence of personal care attendants and lack of encouragement and instruction on how to be physically active contributed to the perception of health professionals being a barrier to PA (Citation22,Citation27,Citation30). Some participants perceived health professionals as being unapproachable and therefore felt nervous talking about PA with them, which hindered their ability to learn about PA participation (Citation30).

Lack of knowledge

Lack of knowledge about PA in participants with TBI, as well as health professionals working with them, was another theme merged from the included studies. One of the biggest barriers for education was the lack of understanding and awareness of the health benefits of PA, which was associated with perceptions of PA being less personally meaningful and not worth perusing (Citation12,Citation26). Furthermore, the lack of understanding about characteristics and types of PA (e.g., where to exercise, how to engage in PA, how much was required to elicit health benefits, and whether incidental activities were considered as PA) was discovered from several studies (Citation12,Citation22,Citation25,Citation27,Citation30).

Participation in PA was also influenced by health professionals’ knowledge. Inexperienced health professionals and those who received limited education about PA were related to participants’ decreased confidence in PA participation, as these health professionals were unable to cater the needs required by this cohort. In some cases, participants were told that they were not cleared to participate in any PA (Citation30). One study incorporated a ‘Think S.A.F.E’ list, which aimed to prevent high impact activities such as contact sports or running for a year (Citation30). However, this list provided some participants with an impression that PA was unsafe, as some referenced the list as a barrier.

Enablers of PA participation

Six included studies revealed enablers of PA participation. These were categorized into five main themes: Personal drivers (found in six studies), Social support (six studies), Professional support (three studies), Accessibility (three studies), and Education (four studies) ().

Table 5. Enablers of PA for individuals with TBI.

Personal drivers

This theme discussed the association between positive attitudes, high self-motivation, and self-efficacy and increased PA participation in participants with TBI. Participants who perceived a high PA level as normal and considered PA as an integral part of their identity reported positive attitudes toward regular PA (Citation12,Citation30). Their beliefs and attitudes about the benefits of PA shaped their motivation to engage in PA, with personally relevant benefits promoting greater motivation (Citation12,Citation25). Participants commonly reported wanting to get back to their pre-injury abilities. For instance, one participant stated ‘I want to get better. I want to get to 100%’ (Citation30). Exercise adherence was found to be positively influenced by personal factors such as age, exercise habits before the injury (particularly walking or jogging being the predominant form of exercise before the injury), and severity of the injury (greater injury severity is associated with higher motivation to recover) (Citation24). Furthermore, completing an activity that participants had previously enjoyed was associated with increased confidence in participating in this type of exercise again (Citation24). Therefore, participants perceived a greater sense of self-efficacy and fewer barriers to PA (Citation28). A few participants further reported time as an enabler. In particular, the severity of their injuries prevented them from returning to work, and as a result, they had more time to plan for PA (Citation29).

Social support

Participants reported that spending time with significant others was enjoyable and encouraged their PA participation (Citation12). For instance, participants reported they ‘needed the support’ to participate in PA, while others used social influences such as ‘[I do it for] my kids’ or ‘my mum’ to enable PA (Citation30). Families and friends, therefore, played a crucial role in providing extra support to help participants adjust to PA when they started (Citation24,Citation29). Participants expressed that completing PA with someone would make it more motivating for them, and as a result, they would be less likely to avoid it (Citation29). In contrast, two quantitative studies found that social support from families and friends was not associated with increased PA in TBI participants (Citation25,Citation28).

Professional support

Professional support via helping participants feel supported, heard, and educated before, during, and following PA was reported as a critical factor encouraging PA participation. Participants who felt they were listened to by their health professionals were most likely to engage in extra PA sessions outside their rehabilitation sessions (Citation25,Citation29). Those whose health professionals instilled and continued to instill PA after rehabilitation believed PA was essential and felt encouraged to continue (Citation29). Likewise, regular review addressing unanticipated issues or questions was related to increased confidence and PA participation, and assisted participants with additional training (Citation25). Participants also expressed positive views toward day center staff, by elaborating on how their assistance with PA interventions encouraged participation and motivation (Citation28). Furthermore, clarity regarding PA instructions which were provided to participants and their relatives was discussed as another enabler (Citation25). A detailed written program and adequate training were reported as an effective approach from health professionals (Citation25).

Accessibility

Ensuring accessible transportation and facilities was vital to promoting PA in participants with TBI. Studies revealed positive effects among service providers who could fund for relevant services and group PA or offered instruction on accessing current facilities (Citation28,Citation30). While participants stated facilities that pre-booked transportation promoted PA participation, they also found having access to adapted equipment was helpful, as this allowed them to engage in PA on all terrains whilst in a wheelchair (Citation29). Furthermore, finance was an enabler for some participants who were entitled to compensation, while others also mentioned assistance to finance would be a facilitator to PA participation (Citation29).

Education

Education was vital for PA participation and long-term involvement. Tailored education from health professionals focusing on the appropriateness and suitability of PA addressed barriers and, in turn, was associated with increased confidence in participating in PA (Citation28). Education about the benefits of PA was related to increased motivation to be more active, alleviating concerns about physical health, and highlighting other types of PA that may be suitable (Citation28). Two studies revealed that participants who understood the health benefits correlated with PA participation and the role of PA in rehabilitation and independence post-injury, believed PA to be worth perusing (Citation12,Citation30). Additionally, educating participants on planning activities and time management was another enabling factor. One participant stated that ‘I am capable of doing two or three sporting activities because I always remind myself that I need to rest. I have to relax and do my things at home’ (Citation29). As a result, participants were able to compensate for cognitive impairments and decreased energy levels (Citation29).

Discussion

Despite well-documented benefits of PA, participation remains low among individuals with TBI. Therefore, this systematic review aimed to summarize and describe factors hindering and facilitating PA participation experienced by adults with TBI, to inform the development and implementation of enabling strategies that could support their participation and long-term involvement in PA. Overall, this review identified multi-dimensional, intertwined factors influencing PA participation in adults with TBI, with similarities shared between barriers and enablers across several themes. While Personal issues and Changing health status were the leading themes for barriers, enablers are commonly categorized under Personal drivers and Social support.

There is strong evidence to indicate that numerous barriers to PA are present for individuals with TBI. These include personal attitudes and motivation, health conditions, lack of support from family/friends and health professionals, environmental issues, and lack of knowledge about PA. However, these barriers are not unique to the TBI cohort. A systematic review on barriers and motivators to PA for individuals who experienced a stroke has also identified personal and environmental barriers (Citation31). These mainly include transportation and costs, access, stroke-related impairments, health problems, embarrassment, knowledge gaps, and fear (Citation31). Similar barriers have also been identified in studies examining conditions such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (Citation20), acquired brain injuries (Citation15), young adults with childhood onset physical disabilities (Citation32), diabetes (Citation33), and spinal cord injuries (Citation34).

Furthermore, exiting literature that provides insights into PA among the general population has revealed personal attitudes and motivation and environmental factors as predominant barriers, overlapping with the barriers reported by individuals with TBI (Citation35,Citation36). However, there are several barriers to PA that appear to be unique to individuals with a chronic condition. A significant barrier that differs from the general population is the changing health status caused by the condition. For instance, individuals with TBI report that their changing health status is associated with mobility and heath limitations (e.g., instability, fatigue, pain), which hinder their participation in PA. Similar findings have also been echoed by stroke patients and individuals with physical disabilities (Citation31,Citation37,Citation38). Evidence suggests that individuals with severe mobility limitations have at least three barriers to PA on average, which is significantly more than those with moderate or no mobility limitations (Citation39). In addition to the changing health status, there are a range of other barriers to PA reported by individuals with TBI that differ from the general population. Key examples include lack of accessible facilities and equipment, needing assistance and support to engage in PA, feeling like a burden as having to constantly ask for help, and lack of knowledge about PA in both health professionals and individuals with TBI.

Given the multi-dimensional and intertwined nature of barriers to PA, a broader approach is required when assisting individuals with TBI. Therefore, health professionals need to consider individual client-related issues in a holistic manner and use a multi-faceted approach when engaging with individuals with TBI. These findings are supported by a narrative review undertaken by Driver and colleagues (Citation19) on individuals with acquired brain injury. Driver et al. (Citation19) identified a myriad of injury-specific biological, psychological, and socio-environmental factors that impact being overweight or obese following acquired brain injury. As a result, the authors recommend tailored interventions to meet individuals’ unique needs (Citation19). Such an approach has been used for the management of other conditions. For example, a biopsychosocial approach to chronic pain management is currently acknowledged as the most effective treatment, since it addresses the biological, psychological, and social factors related to pain and disability (Citation37). Similarly, individuals with TBI may have complex clinical presentations involving altered expectations, beliefs, and behaviors that require tailored PA interventions (Citation19,Citation37).

The World Health Organization (WHO) has developed and endorsed the ICF to help health professionals understand the complexities of health and the interactions between ‘person’ and ‘environment’ (Citation40). The framework allows health professionals to identify an individual’s level of functioning at physical, personal, and societal levels, and understand how environmental factors may reduce participation (Citation41). Therefore, the ICF is useful in recognizing fundamental components that need to be addressed in the PA intervention (Citation42). It further facilitates open communication and engagement between the individual and the health professional, and with other health professionals, organizations, or facilities to mitigate future barriers. As barriers can evolve over time, it is important to evaluate and engage with individuals with TBI on an ongoing basis to ensure the strategies are tailored to their needs. Regular review and continued monitoring have been successful in behavior changing strategies, whereby health professionals are able to reevaluate strategies, discover any new barriers, and make changes as required (Citation43).

Lack of professional support and education is another important finding within the review. This is supported by Pickelsimer and colleagues (Citation44) who assessed the unmet service needs of individuals with TBI. Within this study, 47% participants reported at least one barrier (e.g., lack of awareness/advocacy/case management) to receiving services, 35.2% reported at least one unmet need and 51.5% had unrecognized needs (Citation44). This highlights the importance of education and case management for individuals with TBI, as clients and their caregivers often report a lack of explicit information about the injury and associated consequences, and how to maximize recovery (Citation45). Additionally, individuals with TBI report a lack of knowledge among health professionals as well as fitness and recreation instructors, limiting their confidence in PA participation and access to suitable facilities. A previous study has revealed a successful partnership between knowledgeable physiotherapists and fitness instructors and recreation providers in providing an affordable, accessible, safe, and effective task-oriented PA program for people with neurological conditions in the community (Citation46).

The shared similarities between barriers and enablers across several themes indicate that these factors are essentially ‘two sides of the same coin,’ suggesting multiple barriers may be amenable to change. For instance, social and professional support, personal thoughts and emotions, accessibility of facilities and equipment, and knowledge about PA are identified as barriers but also enablers to PA. This suggests that once a barrier is recognized, the development of strategies to address the barrier may be underpinned by its mirroring factor (i.e., enabler). The impact of TBI can extend beyond an individual and cause changes in their family’s functioning, which impacts the family’s ability to provide desired social support (Citation47), an important factor identified within the current review and other literature (Citation48) that is associated with improved PA. Strategies such as implementation of home-based skills and education sessions for family members, friends, or caregivers may facilitate social support by enhancing the quality of relationship with TBI individuals, which has previously been demonstrated in the literature (Citation49).

Limitations

As with any research, this review has methodological and reporting limitations. While this review included both quantitative and qualitative studies, many had a small sample size and only included individuals who had a level of verbal ability and cognitive capacity. Therefore, the findings may not be generalizable to all adults with TBI. There was also sex bias with 69% of the included participants being male. However, this may reflect the wider TBI population, as males are 2.22 times more likely than women to sustain a TBI (Citation50). Furthermore, as all included studies originated from western countries, there is a knowledge gap in terms of research on TBI in culturally and linguistically diverse populations as these groups are currently under-represented. Given that this review has identified several factors contributing to participation in PA for TBI, research on these population groups is warranted. As this review only focused on studies published in the English language, language bias cannot be ruled out. However, given that this review followed best practice standards in the conduct and reporting of reviews (i.e., PRISMA), such bias has been minimized.

Implication to practice and research

From a clinical practice perspective, it is evident that individuals with TBI experience numerous barriers when participating in PA. Therefore, health professionals should use person-centered, holistic approach when discussing enabling strategies with individuals with TBI. Considering the findings within the current review, key elements underpinning enabling strategies may include delivery of group classes with the involvement of family members/friends, improved accessibility by having access to convenient transportation and adapted equipment and facilities, better education about PA and safe PA participation, and integration of frameworks such as the ICF into practice. Although further research is required to determine what enabling strategies will work best for each barrier, there is no ‘one size fits all’ and ongoing review and monitoring from health professionals are recommended to address evolving barriers in a timely manner.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Menon DK, Schwab K, Wright DW, Mass AI. Position statement: definition of traumatic brain injury. Archiv Phys Med Rehabil. 2010;91(11):1637–40. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2010.05.017.

- Brain injury Australia. Lancet: the cost and frequency of traumatic brain injuries. Putney (AU): Brain Injury Australia; [accessed 16 July 2022]. https://www.braininjuryaustralia.org.au/lancet-the-cost-and-frequency-of-traumatic-brain-injuries/.

- Dewan MC, Rattani A, Gupta S, Baticulon RE, Hung YC, Punchak M, Agrawal A, Adeleye AO, Shrime MG, Rubiano AM, et al. Estimating the global incidence of traumatic brain injury. J Neurosurg. 2018;130(4):1080–97. doi:10.3171/2017.10.JNS17352.

- Hamilton M, Williams G, Bryant A, Clark R, Spelman T. Which factors influence the activity levels of individuals with traumatic brain injury when they are first discharged home from hospital? Brain Inj. 2015;29(13–14):1572–80. doi:10.3109/02699052.2015.1075145.

- Izzy S, Chen PM, Tahir Z, Grashow R, Radmanesh F, Cote DJ, Yahya T, Dhand A, Taylor H, Shih SL, et al. Association of traumatic brain injury with the risk of developing chronic cardiovascular, endocrine, neurological, and psychiatric disorders. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(4):e229478. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.9478.

- Hopkins Medicine J. Rehabilitation after traumatic brain injury. Baltimore (US): Johns Hopkins Medicine; [accessed 16 July 2022]. https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/treatment-tests-and-therapies/rehabilitation-after-traumatic-brain-injury.

- Khan F, Baguley IJ, Cameron ID. 4: rehabilitation after traumatic brain injury. Med J Aust. 2003;178(6):290–95. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.2003.tb05199.x.

- Zhang Y, Huang Z, Xia H, Xiong J, Ma X, Liu C. The benefits of exercise for outcome improvement following traumatic brain injury: evidence, pitfalls and future perspectives. Exp Neurol. 2022;349:113958. doi:10.1016/j.expneurol.2021.113958.

- World Health Organization. Physical activity. Geneva (CH): World Health Organization; 2022 [accessed 9 Mar 2023]. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/physical-activity.

- Rimmer JH. Physical activity. Chicago (US): Encyclopedia Britannica; 2022 [accessed 9 Mar 2023]. https://www.britannica.com/topic/physical-activity.

- Das P, Horton R. Rethinking our approach to physical activity. The Lancet. 2012;380(9838):189–90. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61024-1.

- Analytis P, McKay A, Hamilton M, Williams G, Warren N, Ponsford J. Physical activity: perceptions of people with severe traumatic brain injury living in the community. Brain Inj. 2018;32(2):209–17. doi:10.1080/02699052.2017.1395479.

- Archer T. Influence of physical exercise on traumatic brain injury deficits: scaffolding effect. Neurotox Res. 2011;21(4):418–34. doi:10.1007/s12640-011-9297-0.

- Jones TM, Dear BF, Hush JM, Tito N, Dean CM. myMoves program: feasibility and acceptability study of a remotely delivered self-management program for increasing physical activity among adults with acquired brain injury living in the community. Phys Ther. 2016;96(12):1982–93. doi:10.2522/ptj.20160028.

- Lorenz LS, Charrette AL, O’Neil-Pirozzi TM, Doucett JM, Fong J. Healthy body, healthy mind: a mixed methods study of outcomes, barriers and supports for exercise by people who have chronic moderate-to-severe acquired brain injury. Disabil Health J. 2018;11(1):70–78. doi:10.1016/j.dhjo.2017.08.005.

- Aromataris E, Lockwood C, Porritt K, Pilla B, Jordan Z, editors. JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis [Internet]. Adelaide (AU): JBI; 2024. Chapter 8, Mixed methods systematic reviews (2020). [accessed 22 Jul 2027]. https://synthesismanual.jbi.global.

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71.

- Joanna Briggs Institute. Critical appraisal tools. Adelaide (AU): Joanna Briggs Institute; [accessed 23 Mar 2022]. https://jbi.global/critical-appraisal-tools.

- Driver S, Douglas M, Reynolds M, McShan E, Swank C, Dubiel R. A narrative review of biopsychosocial factors which impact overweight and obesity for individuals with acquired brain injury. Brain Inj. 2021;35(9):1075–85. doi:10.1080/02699052.2021.1953596.

- Thorpe O, Johnston K, Kumar S. Barriers and enablers to physical activity participation in patients with COPD: a systematic review. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev. 2012;32(6):359–69. doi:10.1097/HCR.0b013e318262d7df.

- De Joya AL. Barriers to physical activity following traumatic brain injury: a cognitive mapping study [ dissertation]. Birmingham (US): The University of Alabama at Birmingham; 2012.

- Driver S. What barriers to physical activity do outpatients with a traumatic brain injury face. The J Cognit Rehabil. 2009;33:4–10.

- Driver S, Ede A, Dodd Z, Stevens L, Warren AM. What barriers to physical activity do individuals with a recent brain injury face? Disabil Health J. 2012;5(2):117–25. doi:10.1016/j.dhjo.2011.11.002.

- Hassett LM, Tate RL, Moseley AM, Gillett LE. Injury severity, age and pre-injury exercise history predict adherence to a home-based exercise programme in adults with traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj. 2011;25(7–8):698–706. doi:10.3109/02699052.2011.579934.

- Leung J, Fereday S, Sticpewich B, Hanna J. Extra practice outside therapy sessions to maximize training opportunity during inpatient rehabilitation after traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj. 2018;32(7):915–25. doi:10.1080/02699052.2018.1469046.

- Pham T, Green R, Neaves S, Hynan LS, Bell KR, Juengst SB, Zhang R, Driver S, Ding K. Physical activity and perceived barriers in individuals with moderate-to-severe traumatic brain injury. PM & R. 2022;15(6):1–9. doi:10.1002/pmrj.12854.

- Pinto SM, Newman MA, Hirsch MA. Perceived barriers to exercise in adults with traumatic brain injury vary by age. J Funct Morphol Kinesiol. 2018;3(3):47. doi:10.3390/jfmk3030047.

- Reavenall S, Blake H. Determinants of physical activity participation following traumatic brain injury. Int J Ther Rehabil. 2010;17(7):360–69. doi:10.12968/ijtr.2010.17.7.48893.

- Quilico EL, Harvey WJ, Caron JG, Bloom GA. Interpretative phenomenological analysis of community exercise experiences after severe traumatic brain injury. Qual Res Sport Exerc Health. 2021;13(5):800–15. doi:10.1080/2159676X.2020.1778064.

- Self M, Driver S, Stevens L, Warren AM. Physical activity experiences of individuals living with a traumatic brain injury: a qualitative research exploration. Adapt Phys Activ Q. 2013;30(1):20–39. doi:10.1123/apaq.30.1.20.

- Nicholson S, Sniehotta FF, van Wijck F, Greig CA, Johnston M, McMurdo MET, Dennis M, Mead GE. A systematic review of perceived barriers and motivators to physical activity after stroke. Int J Stroke. 2013;8(5):357–64. doi:10.1111/j.1747-4949.2012.00880.x.

- Buffart LM, Westendorp T, van den Berg-Emons RJ, Stam HJ, Roebroeck ME. Perceived barriers to and facilitators of physical activity in young adults with childhood-onset physical disabilities. J Rehabil Med. 2009;41(11):881–85. doi:10.2340/16501977-0420.

- Thomas N, Alder E, Leese GP. Barriers to physical activity in patients with diabetes. Postgrad Med J. 2004;80(943):287–91. doi:10.1136/pgmj.2003.010553.

- Vissers M, van den Berg-Emons R, Sluis T, Bergen M, Stam H, Bussmann H. Barriers to and facilitators of everyday physical activity in persons with a spinal cord injury after discharge from the rehabilitation centre. J Rehabil Med. 2008;40(6):461–67. doi:10.2340/16501977-0191.

- Hoare E, Stavreski B, Jennings GL, Kingwell BA. Exploring motivation and barriers to physical activity among active and inactive Australian adults. Sports. 2017;5(3):47. doi:10.3390/sports5030047.

- Sørensen M, Gill DL. Perceived barriers to physical activity across Norwegian adult age groups, gender and stages of change. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2008;18(5):651–63. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0838.2007.00686.x.

- Booth J, Moseley GL, Schiltenwolf M, Cashin A, Davies M, Hübscher M. Exercise for chronic musculoskeletal pain: a biopsychosocial approach. Musculoskeletal Care. 2017;15(4):413–21. doi:10.1002/msc.1191.

- Damush TM, Plue L, Bakas T, Schmid A, Williams LS. Barriers and facilitators to exercise among stroke survivors. Rehabil Nurs. 2007;32(6):253–62. doi:10.1002/j.2048-7940.2007.tb00183.x.

- Rasinaho M, Hirvensalo M, Leinonen R, Lintunen T, Rantanen T. Motives for and barriers to physical activity among older adults with mobility limitations. J Aging Phys Act. 2007;15(1):90–102. doi:10.1123/japa.15.1.90.

- World Health Organization. International classification of functioning, disability and health (ICF). Geneva (CH): World Health Organization; [accessed 29 July 2022]. https://www.who.int/standards/classifications/international-classification-of-functioning-disability-and-health.

- Rimmer JH. Use of the ICF in identifying factors that impact participation in physical activity rehabilitation among people with disabilities. Disabil Rehabil. 2006;28(17):1087–95. doi:10.1080/09638280500493860.

- Scholten I, Barradell S, Bickford J, Moran M. Twelve tips for teaching the international classification of functioning, disability and health with a view to enhancing a biopsychosocial approach to care. Med Teach. 2021;43(3):293–99. doi:10.1080/0142159X.2020.1789082.

- National Health and Medical Research Council. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of overweight and obesity in adults, adolescents and children in Australia. Canberra (AU): National Health and Medical Research Council; 2013 Sept [accessed 23 Feb 2023]. https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/about-us/publications/clinical-practice-guidelines-management-overweight-and-obesity#block-views-block-file-attachments-content-block-1.

- Pickelsimer EE, Selassie AW, Sample PL, Heinemann AW, Gu JK, Veldheer LC. Unmet service needs of persons with traumatic brain injury. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2007;22(1):1–13. doi:10.1097/00001199-200701000-00001.

- Hart T, Driver S, Sander A, Pappadis M, Dams-O’Connor K, Bocage C, Hinkens E, Dahdah MN, Cai X. Traumatic brain injury education for adult patients and families: a scoping review. Brain Inj. 2018;32(11):1295–306. doi:10.1080/02699052.2018.1493226.

- Salbach NM, Howe J-A, Brunton K, Salisbury K, Bodiam L. Partnering to increase access to community exercise programs for people with stroke, acquired brain injury, and multiple sclerosis. J Phys Act Health. 2014;11(4):838–45. doi:10.1123/jpah.2012-0183.

- Leach LR, Frank RG, Bouman DE, Farmer J. Family functioning, social support and depression after traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj. 1994;8(7):599–606. doi:10.3109/02699059409151012.

- Lindsay Smith G, Banting L, Eime R, O’Sullivan G, van Uffelen JGZ. The association between social support and physical activity in older adults: a systematic review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2017;14(1):56–56. doi:10.1186/s12966-017-0509-8.

- Wilson S, McKenzie K, Quayle E, Murray G. A systematic review of interventions to promote social support and parenting skills in parents with an intellectual disability. Child care Health Dev. 2014;40(1):7–19. doi:10.1111/cch.12023.

- Frost RB, Farrer TJ, Primosch M, Hedges DW. Prevalence of traumatic brain injury in the general adult population: a meta-analysis. Neuroepidemiology. 2013;40(3):154–59. doi:10.1159/000343275.

Appendix A

- search syntax

1 MEDLINE

2 Emcare

3 Embase

4 PsychINFO

5 PEDro

6 OT seeker