?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

We proposed and tested the notion of a bidirectional influence of emotion expressions and context. In two studies (N = 215, N = 222), we found that the expressions shown by supporters and opponents of a player in a ball game were used by observers to correctly deduce the eliciting situation – i.e. the outcome of the game. Conversely, knowledge of the outcome of the game (as well as real world knowledge of the negative interdependence of opponents in a competitive game) influenced the perception of both the emotions shown (Study 1) and the perceived bias/emotional control exhibited by the expressers (Study 2). This research contributes to a growing body of research that shows that both situations and emotion expressions contain intrinsic meaningful information and that both sources of information are used by observers in a social appraisal process.

In every-day life we rarely see facial expressions devoid of context. Rather, we see people who are interacting with others or with objects in meaningful surroundings that can influence our interpretation of the facial expressions shown. Hence, the wrinkled nose of a person walking through a fish market will be perceived differently from the wrinkled nose of someone observing a social faux pas. In recent years, emotion research has increasingly emphasised the importance of context for emotion perception (e.g. Barrett, Mesquita, & Gendron, Citation2011; Hess & Hareli, Citation2015). In fact, constructivist theories of emotion consider context to be of preeminent importance when it comes to constructing meaning from emotional exchanges (for an overview see, e.g. Faucher, Citation2013). From this perspective, facial expressions are described as inherently ambiguous and their interpretation as strongly dependant on the context in which they are shown (Hassin, Aviezer, & Bentin, Citation2013). From this view then, the interpretation of a particular type of emotion expression is defined primarily by the kind of situation (i.e. context) in which the expression is observed (Clore & Ortony, Citation2013).

Recently, we proposed that this influence is bidirectional (Hess, Landmann, David, & Hareli, Citation2017). That is, just as the context influences the interpretation of facial expressions, these expressions have sufficient intrinsic meaning to conversely influence the interpretation of the situation that elicited them.

The reverse engineering of situational information

The notion that emotional expressions can signify situations can be derived from appraisal theories of emotion. According to appraisal theories of emotion, emotions are elicited and differentiated through a series of appraisals of (internal or external) stimulus events based on the perceived nature of the event (e.g. Scherer, Citation1987; Frijda, Citation1986). Importantly in this context, facial expressive behaviour has been posited to be a direct readout of appraisal outcomes (Kaiser & Wehrle, Citation2001; Scherer, Citation1992; Smith & Scott, Citation1997).

Further, participants can reconstruct both their own appraisals (Robinson & Clore, Citation2002) and those of the protagonist of a story (e.g. Hareli & Hess, Citation2010; Roseman, Citation1991; Scherer & Grandjean, Citation2008). This information can then be used to deduce additional information about the expresser or the situation from the expresser’s behaviour in a process we call reverse engineering (Hareli & Hess, Citation2010).

More generally, any information that is relevant to appraisals can be used to predict emotional reactions when the appraisals are known and conversely to deduce the appraisals when the reaction is known. For example, the mere fact that someone reacts with an emotion to an event signals that the event is relevant to that specific person, which in turn provides information about the person's goals and values as well as about the event. That is, knowing that a person reacted, for example, with happiness to the win of a team, allows the observer to conclude that the person cares about the team’s success. Conversely, knowing that someone cares about a team’s success allows the conclusion that a win would elicit happiness. This in turn allows the conclusion that a happy facial expression shown by someone who cares about a given team, signals that the team won.

In short, because appraisals are based on information about the situation (in light of the goals, resources and values of the perceiver), the resulting facial expression necessarily also provides information about the situation. Yet, at the same time, other types of contextual information such as the social roles of the expressers or their relationship to each other can be informative as well (Hess & Kirouac, Citation2000; Kirouac & Hess, Citation1999). We propose that observers use perspective taking to balance these different types of information when drawing conclusions about a person’s goals and motives but also when decoding their emotion expressions.

Identifying emotions from nonverbal cues

Specifically, there are two ways to identify emotions from nonverbal cues (Kirouac & Hess, Citation1999). The traditional context-free research on emotion recognition implicitly assumes a pattern matching process, where specific features of the expression are associated with specific emotions (Buck, Citation1984). For example, upturned corners of the mouth or lowered brows are recognised as smiles or frowns respectively and a perceiver can thus conclude that the individual is happy or angry. In this process, the perceiver is a passive decoder who could, and in fact can, be replaced by an automated system and context information plays no role or only a minimal one (e.g. Dailey, Cottrell, Padgett, & Adolphs, Citation2002).

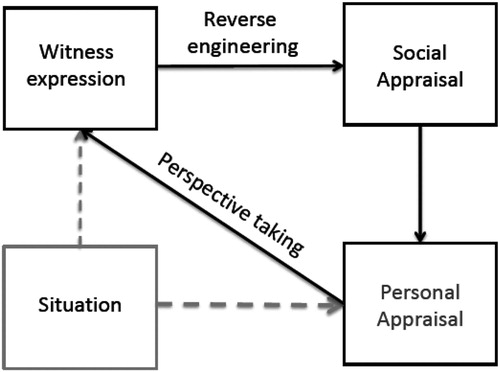

However, in many situations the perceiver can also use a second process – perspective taking. Knowing the goals and values of others or the specific situation they are in allows the perceiver to take their perspective and to infer their likely emotional state. The bidirectional model of emotion perception combines the process of reverse engineering of the appraisals of others with perspective taking (see ) by proposing that reverse engineered or social appraisals function as input for perspective taking.

A bidirectional model of emotion and situation perception

The model (see ) posits that someone who observes an event (the observer), appraises the situation him or herself (personal appraisal, dashed black line) and (re)acts based on that appraisal as claimed by appraisal theories (e.g. Scherer, Citation1987). When other individuals also witness the event (witnesses), their emotion expressions reflect their own appraisal of the situation (dashed grey line) and allow the reverse engineering of their appraisal of the situation. These social appraisals (see also, Fischer & Manstead, Citation2008) can be used by the observer as input information to further refine their personal appraisal – together with other situational information. The personal appraisal of the situation by the observer then impacts – via perspective taking – on the observer’s interpretation of the witnesses’ emotion expression. That is, both sources of information – personal appraisal and social appraisal – impact on each other.

Notably, when the observer does not see the event directly or is missing information to understand the meaning of the event, the witnesses’ expressions can – via the link through social appraisal – substitute as source for situational information (solid grey line labelled perspective taking). Importantly, this information can then be used by the observer to re-evaluate the meaning of the expressions shown by the witnesses.

For example, a team winning a game should be a pleasant and goal conducive event for a supporter of that team but not for an opponent, that is, a supporter of the opposing team, for whom this event should be goal obstructive. These appraisals should reflect themselves in the emotional expressions shown. We propose that when participants (observers) rate the facial expressions of witness A who experienced a positive event that is however negative for witness B, as in the situation above, they will take into account the facial expressions of both individuals and reverse engineer their respective appraisal of the situation. Importantly, this information serves as input for perspective taking and allows the participants to adjust their interpretation of the facial expressions shown by both witnesses.

Let us assume that an observer sees that, after the last throw of a game, the supporter of team A shows a big smile and the supporter of team B a neutral expression. From the smile they can deduce that something goal conducive and pleasant happened. Given the context, a game was just finished, they can deduce that the team supported by that person has won. This information can then be used to interpret the neutral expression shown by B, who supports the losing team and based on perspective taking should experience negative affect because observers know that losing a game typically elicits negative emotions. Perspective taking then leads to an attribution of less positive affect to the supporter of the losing team, even when this person shows a neutral or even a happy expression (perhaps to put up a brave front).

In short, observers will use the facial expressions of witnesses to an event to reverse engineer the appraisals of these expressers and at the same time use those social appraisals to deduce their likely emotional state, even if this state is incongruent with the emotions expressed. In other words, we posit that the social perception of an emotion depends neither on the expressions alone nor on the context alone. Rather, it is determined by a combination of the two as well as the real world knowledge of the perceiver. In this process, the perceiver is seen as an active agent who balances all available information to arrive at a social judgment.

The present research had the goal to test this prediction. Specifically, we tested the notion that (a) the expression of a witness to an event provides information about the event that caused this expression, (b) this situational information then informs the observer's own perception of the situation, which (c) in turn impacts on the observer's perception of the witnessed emotion.

The present research

To test this model we selected the sports context described above. This context is particularly suitable as there are clear motivational goals associated with being a supporter of a team and there is a clear negative interdependence between supporters of opposing teams. Thus, a supporter of team A can be expected to consider anything that advances team A’s chances of winning as goal conducive and anything that advances team B’s chances of winning as goal obstructive. Goal conducive events elicit happiness (Scherer, Citation1987) and conversely, using reverse engineering (Hareli & Hess, Citation2010), participants can conclude that when a supporter of team A reacts with happiness, the eliciting event is good for team A and hence should be bad for team B. Participants saw both the supporter of the player and a supporter of the opposing team at the same time, to make the motivational negative interdependence between these two witnesses to the event salient.

Finally, we added a third emotion: awe. Awe is characterised by a realisation of the presence of something greater than the self, as well as some disengagement from awareness of the self (Shiota, Keltner, & Mossman, Citation2007). As such, the expression of awe should transcend the negative interdependence structure of the expressions of happiness vs. neutrality: showing awe in response to an event should not depend on whether the expresser supports the player's team or not. As such, this emotion makes an interesting control condition as it has been shown to be less susceptible to context information about the expresser, because an extraordinary outcome “stands above” the specific motivations of supporters and opponents and is recognised as extraordinary by both (Hareli, Elkabetz, & Hess, Citation2019).

We predicted that participants will use the negative interdependence of the goals of a supporter of the player and an opponent’s team supporter in combination with their expressions (happy, neutral, awe) to deduce (a) the nature of the emotion eliciting event, i.e. whether the player played well or not, (b) use this information about the situation to re-evaluate their judgment of the actors’ likely emotional states in light of this outcome. That is, we predict a bidirectional relationship between these two sources of information, resulting in mutual influence.

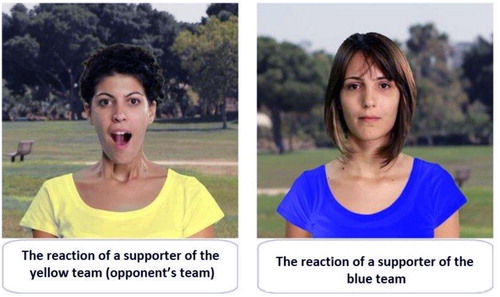

In two studies, participants were shown a series of images from a fictitious ball game taken from Hareli et al. (Citation2019). A fictitious game was chosen so that individual differences in knowledge of the game would not interfere with the social perception process. Participants first saw a series of images which depicted the playing field as well as spectators who either supported the team of the player currently on the field (supporters) or the opposing team (opponents). The teams were identified by the colour of their T-shirts. The picture showing the last throw was followed by a photo depicting one supporter of the player and one supporter of the opponent team, showing the same or different emotions ( shows the last three images depicting the game, shows an example of the two expressers).

Based on results from Study 1, which suggested that participants may trust opponents’ expressions more than supporters’ expressions, in Study 2 we addressed the question of whether participants would judge the expression shown by supporters as less authentic. All data are available upon request from the authors. The research meets the ethical guidelines, including adherence to the legal requirements for the Humboldt-University of Berlin. We report all exclusions, measurements and manipulations.

Study 1

Study 1 was designed to test the notion that participants are able to deduce the likely situational context (i.e. the outcome of the game) based on the emotion expressions shown by supporters and opponents and that this reverse engineered situational information would in turn affect ratings of the emotion expressions.

Method

Participants

A total of 215 (126 women) participants with a mean age of 38 years (SD = 12) who were recruited through Amazon MTurk completed the study and passed control questions probing for attention. We aimed in both studies for a minimum of 20 participants per cell in a complete between-participants design.

Stimulus materials

Facial expressions

Facial expressions of awe, happiness and neutrality by six men and women were taken from the Haifa Set of Facial Expressions of Emotions (HSFEE, Hareli et al., Citation2019). Digital image manipulation was used to colour the actors’ shirts (blue = supporter; yellow = opponent of the player) and to create sets of one supporter and one opponent of the same sex showing either awe, happiness or a neutral expression in all possible combinations. Faces were counterbalanced between conditions, such that the same individuals were shown as supporters or opponents and appearing on the left or right side of the photo respectively for half the participants. Each participant saw only one condition.

Ball game

Participants first saw the ten photos that depicted a fictitious, boule-like ball game (see , for the last three images). Participants saw in sequence: the game field, pictures of people watching the game, a person taking his turn in the game and throwing a ball, and the position of the three balls thrown by the player. This last image in the set (which depicted the outcome of the final throw) was followed by the “reaction” of one of the player's supporters (henceforth “supporter”) and one of the opponent's supporters (henceforth “opponent”) shown next to each other (see for an example). Supporters and opponents were distinguished by the colour of their t-shirt. Participants saw in the photos that the blue team was playing. To ensure that participants could tell who is a supporter of the player and who of the opponent, labels below each photo reminded them of that.

Procedure and dependent measures

The study was conducted in a between-participants design and each participant saw only one game and one combination of reactions by one supporter and one opponent. Following the sequence of photos, participants were first asked to briefly describe what they thought the purpose of the game was, based only on what they had observed. This served to make sure that they had paid attention to the sequence of images. Participants then answered five questions about the outcome of the play and the quality of the performance of the player (likelihood that the player won the game, what was the quality of the performance, player's skill level, player's performance relative to the standard performance, chances that the player's performance had set a new record). As these correlated substantially (r = .57 to r = .78) they were combined into one variable called performance quality (α = .92). Finally, participants rated the intensity of the emotions shown by the supporter and the opponent respectively on six single item scales. These were labelled awe, happiness and neutral together with the team label to make sure that the participants knew which of the two individuals’ expression they were rating. The scales were anchored with 1 – very low to 7 – very high.

Data analysis plan

We first assessed whether participants were indeed able to deduce the performance quality of the player from the witnesses’ expressions. For this, we conducted a 3 (supporter emotion condition: awe, happiness, neutral) × 3 (opponent emotion condition: awe, happiness, neutral) between subjects ANOVA on the rated performance quality. The results were followed-up by post-hoc tests (p < .05).

We then examined two questions. First, does the quality of the player’s performance as indexed by the opponent’s expression impact on the perception of the supporter’s expression? We predicted that a happy expression shown by the opponent would signal a loss by the player’s team (i.e. low player performance quality) and in turn would lead to a reduction in perceived happiness of the supporter. By contrast, a neutral expression shown by the opponent should signal a win by the player’s team (i.e. high player performance quality) and in turn would increase ratings of the supporter’s happiness.

We then used mediation analyses to test the prediction that it is the indirect effect of opponent emotion condition on player performance quality that predicts the change in rated supporter emotion intensity. Finally, we conducted the same set of analyses for supporter emotion condition as a predictor of rated opponent emotion intensity.

Results

Did participants deduce the performance quality of the player’s last throw based on the emotion expressions shown by supporter and opponent?

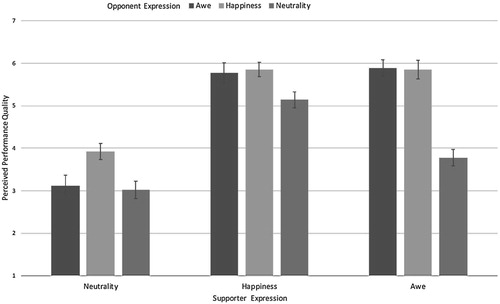

A 3 (supporter emotion condition: awe, happiness, neutral) × 3 (opponent emotion condition: awe, happiness, neutral) between subjects ANOVA was conducted on the composite performance quality scale. As predicted, the main effects of supporter emotion condition, F(2,206) = 68.79, p < .001, = .40, and opponent emotion condition were significant F(2,206) = 17.28, p < .001,

= .14. Post-hoc tests revealed that participants evaluated the player’s performance quality as significantly better when the supporter showed happiness (M = 5.42, SD = .84, CI95% 5.21; 5.61) than when the supporter showed awe (M = 4.66, SD = 1.48, CI95% 4.29; 5.02) or a neutral expression (M = 3.21, SD = 1.35, CI95% 2.92; 3.51).

Conversely, the player’s performance was rated as significantly better when the opponent showed either a neutral expression (M = 4.67, SD = 1.33, CI95% 4.37; 4.98) or awe (M = 4.56, SD = 1.67, CI95% 4.19; 4.94), which did not differ, than when the opponent showed happiness (M = 3.72, SD = 1.52, CI95% 3.33; 4.10). Thus, participants correctly deduced that the happiness of a supporter and the neutral expression of an opponent both signal that the player played well. Conversely, a neutral expression by a supporter and a happy expression by an opponent signalled that he did not play well, i.e. he lost the game.

Awe by either the supporter or the opponent indicated a good play, in line with the notion that awe in a performance context signals that a standard was exceeded (Hareli et al., Citation2019). Importantly, as expected, the meaning of awe was not dependent on the allegiance of the expresser.

We then assessed whether knowledge of the outcome of the game, as signalled by either the supporter’s or the opponent’s expressions, influenced the perception of the emotion shown by the respective other person.

The influence of the situational information indexed by the opponent’s facial expression on the perception of the supporter’s emotional state

To assess the influence of the opponents’ expression on the perceived expressions of supporters, we first conducted a 3 (supporter expression condition: awe, happiness, neutrality) × 3 (opponent expression condition: awe, happiness, neutrality) between subjects ANOVA on the emotion intensity ratings for the supporters’ expressions (see upper part of for F-values and upper part of for means).

Table 1. Effects of supporter's and opponent's expressions condition on emotion intensity ratings.

Table 2. Mean ratings of supporter's and opponent's expressions condition as a function of supporter's and opponent's expressions Study 1.

Trivially, main effects of supporter emotion condition on the rated intensity of the supporter’s expression emerged. Specifically, post-hoc tests revealed significant differences, such that the supporter was rated as most happy when showing happiness, as most in awe when showing awe and as most neutral when showing neutrality – independently of the emotion of the opponent. This was expected as validated emotion expressions had been used as stimuli.

Importantly, the predicted significant influence of opponent expression on ratings of the supporter’s expressions emerged as well. Specifically, for all supporter emotion intensity ratings, significant main effects of opponent emotion expression condition as well as significant supporter x opponent emotion expression condition interactions (see the upper part of ) emerged. That is, as predicted, the perceived intensity with which the supporter expressed emotions varied as a function of the emotion shown by the opponent. For example, supporters who showed happiness were rated as significantly less happy when the opponent also expressed happiness but not when the opponent expressed awe or neutrality. This finding is congruent with the idea that supporters and opponents cannot both be happy but both can be in awe. Thus, participants “adjusted” their happiness ratings for a happy supporter in light of the situational information signalled by the expression of the opponent.

Mediation analysis

To assess whether the impact of opponent expression condition on rated supporter emotion intensity was, indeed, mediated by the situational information provided by the opponent’s expression, we conducted a mediation analysis using PROCESS 3.1 (Hayes, Citation2017). For this, we contrasted happiness and neutrality shown by the opponent to predict the perceived emotion of the supporter as mediated by perceived performance. We excluded awe as independent variable from this analysis as awe should always signal that the game was won and can therefore not be contrasted against either happiness or neutrality.

The independent variable, therefore, was opponent expression condition (0 – neutral, 1 – happy). We predicted that opponent expression signals perceived player performance quality, or in other words, situational information about the game. In turn, situational information about the game should predict intensity ratings for supporter emotion. Hence, perceived player performance quality was the mediating variable and the three dependent variables were perceived intensity of supporter happiness, neutrality and awe. The results are shown in upper panel.

Table 3. Results of mediation analyses Study 1.

As expected, opponent facial expression condition significantly predicted player performance, such that a happy opponent was associated with lower performance quality ratings. Further, perceived performance quality significantly and positively predicted perceived supporter happiness and awe. While the direct effect from opponent expressions to perceived supporter happiness/awe was not significant, the predicted indirect effect through perceived player performance quality was significant for both happiness and awe (see ).

Further, performance quality significantly and negatively predicted perceived supporter neutrality. Both the direct effect from opponent facial expression condition to perceived supporter emotion, b = 1.54, p < .001, and the predicted indirect effect through perceived player performance quality were significant. In sum, as hypothesised, the expressions shown by the opponent predicted perceived performance quality, which in turn predicted perceived supporter happiness, awe and neutrality.

The influence of the situational information indexed by the supporter’s facial expression on the perception of the opponent’s emotional state

To assess the converse influence of the expression of supporters on the perceived expression intensity of opponents, a 3 (supporter expression condition: awe, happiness, neutrality) × 3 (opponent expression condition: awe, happiness, neutrality) between subjects ANOVA was conducted on ratings of the intensity of the opponents’ expressions (see lower part of for F-values and lower part of for means).

Similar to the results for supporters, significant main effects of opponent expression condition emerged for ratings of the intensity of the opponent’s happiness, awe and neutrality. Post-hoc tests revealed that the opponent was rated as most happy when showing happiness, as most in awe when showing awe and as most neutral when showing neutrality (see and ).

Further, significant opponent by supporter expression condition interactions suggested that emotions shown by the supporter influenced the perception of the opponent’s happiness and neutrality. However, this was not the case for opponent awe for which only a main effect of opponent expression emerged significantly (see the lower part of ).

Mediation analysis

To assess whether the impact of supporter expression on opponent emotion was mediated by the situational information provided by the supporter’s expression, we conducted a mediation analysis using PROCESS 3.1 (Hayes, Citation2017) using the same approach as detailed above (see lower panel).

Supporter expression condition positively predicted perceived player performance, which in turn negatively predicted the perceived intensity of opponent happiness. However, perceived player performance quality did not predict opponent awe or neutrality. None of the direct links from supporter expression condition to perceived opponent emotion were significant.

In sum, only perceived opponent happiness was significantly predicted by the indirect effect of supporter expression condition on perceived performance quality. This may suggest that participants did not fully trust the supporter’s expressions to signal the type of situation that would have resulted in opponent neutrality (a good throw by the player which would mean that the opponent’s team lost) or awe (if the throw has been outstanding). This in turn may suggest that perceivers consider supporters to be more likely than opponents to mask their expressions, for example, by putting on a “brave face.” That is, participants might consider supporter emotion expressions to be less trustworthy and hence less informative than opponent expressions. As a consequence, they did not use the supporter’s expression to adjust their perception of the opponent’s emotions.

Discussion

In all, the findings from Study 1 suggest that participants’ ratings of the supporters’ and, to a lesser degree, the opponents’ emotion expressions were mediated by their knowledge about the likely goals of the expressers and the situational information they derived from these very emotion expressions. Thus, these findings suggest that, when rating the emotions expressed by the supporter/opponent, participants considered the meaning of both expressions with regard to the outcome of the game.

It is important to remember that participants were clearly instructed to rate the expressive behaviour of each person separately. Nonetheless, participants used the complete information available to assess the situation and deduce the likely emotion felt by the expresser and from there judged the expression. Specifically, the ANOVA results showed that participants rated the focal emotions of supporters and opponents according to the emotion category they were drawn from. That is, happy expressions were rated as most happy, awe expressions as showing most awe and neutral expressions as most neutral. However, the mediation analysis, which focused on the potentially contradictory emotional reactions of opponents and supporters – happiness and neutrality, showed that observers used the situational information conveyed by these expressions to judge the likely emotional state of the observed person and correspondingly adjust their ratings as predicted by the bidirectional model proposed.

Study 2

Results from study 1 provide support for the idea that participants employ perspective taking, based on their understanding of the situation, to assess the “real” emotion felt by a person. However, whereas opponent emotion expression had a pervasive impact on all three perceived supporter emotions, this was not the case for the influence of supporter emotion expressions on opponent emotion. Specifically, the expression reflecting the situational information derived from the supporter’s expressions was not predictive of the opponent's neutrality or awe. Since an opponent would show neutrality and potentially awe when the player plays well and the supporter’s team wins, this suggests that the observers may not have believed the supporter’s positive expressions (indicating such a win) to be always honest. That only trusted expressions are used for perspective taking would support the notion that it is indeed the situational information gleaned from the observer’s expression which influences the emotion ratings and not a direct effect of expression (such as, for example, a contrast effect). We therefore conducted a second study to assess the notion that participants may not trust supporter expressions as much as opponent expressions and therefore do not consider supporters’ expressions to provide valid information on the situation, which could be used for perspective taking.

Trust requires three elements: Ability, benevolence and integrity (Mayer, Davis, & Schoorman, Citation1995). Ability in this context refers to expertise. Thus, if participants believe that the supporter is less knowledgeable than the opponent then they should trust the supporter’s reactions, and hence his or her expression, less. Benevolence and integrity in this context refer to the notion that the expresser is not hiding or masking their emotions to mislead the observer. We therefore asked participants about the perceived expertise of the supporter and the opponent respectively as well as whether they felt that these individuals were biased in their judgment or tried to control their expressions.

Method

Participants

A total of 222 (85 women, 1 gender unknown) participants with a mean age of 35 years (SD = 11) who were recruited through Amazon MTurk completed the study and passed control questions probing for attention.

Procedure and dependent measures

The same stimulus materials as for Study 1 were used. Following the sequence of photos, participants were again first asked to briefly describe what they thought the purpose of the game was. They then rated the player’s performance quality using the same five scales as in Study 1. These scales were again correlated (r = .42 to r = .83) and hence combined into one variable called performance quality (α = .92). We then asked, using single item scales, for the perceived expertise of the opponent and supporter respectively to assess whether the supporters and opponents are seen as equally competent to assess the quality of the play. Finally, participants rated, for both the supporter and the opponent, how biased their judgment seemed to be and the extent to which they tried to control their expression. We used the word “bias” because this term is commonly used to refer to someone whose judgment may favour one group over another.

Results

We first verified whether participants were able to deduce the quality of the performance of the player as in Study 1. For this, a 3 (supporter emotion condition: awe, happiness, neutral) × 3 (opponent emotion condition: awe, happiness, neutral) was conducted on the composite performance quality scale. Significant main effects of supporter emotion condition, F(2,213) = 94.44, p < .001, = .47, and opponent emotion condition, F(2,213) = 32.10, p < .001,

= .23, as well as a significant supporter by opponent emotion condition interaction emerged, F(4,213) = 7.36, p < .001,

= .12 (see for means and standard errors).

Figure 4. Perceived performance quality of the player as a function of supporter expression and opponent expression.

As in Study 1, participants evaluated the player’s performance as significantly better when the supporter showed happiness than when the supporter showed a neutral expression, irrespective of the emotion shown by the opponent. Correspondingly, the player’s performance quality was rated as significantly better when the opponent showed either a neutral expression or awe, which did not differ, and worst when the opponent showed happiness. That is, participants deduced that the team whose member showed happiness won the game and judged the player performance accordingly.

Performance was rated as relatively low when the supporter showed neutrality, suggesting that perceivers followed the supporters’ evaluation that the player had not played well. However, it was rated as significantly higher when the opponent showed awe. By contrast, even though performance was generally rated higher when the supporter showed either awe or happiness, perceived performance was rated as significantly lower when the opponent showed happiness. This may be due to the notion suggested above, that the positive expression of a supporter is not always seen as indicative of a truly excellent performance. That this reduction was less extreme when the opponent showed awe while the supporter showed happiness supports the notion that awe is not dependent on the allegiance of the expresser as it signals an outstanding achievement.

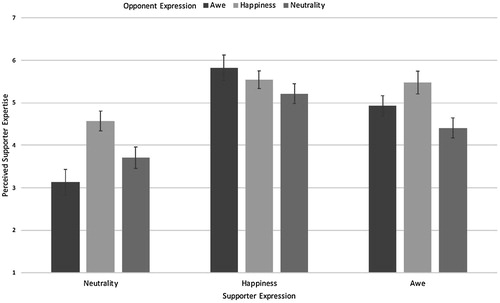

Perceived expertise

To assess whether the supporter or the opponent was considered a better judge of the game, a mixed model ANOVA with the within-subjects factor team (supporter vs opponent) and the between subjects factors opponent emotion condition and supporter emotion condition on perceived expertise was conducted. Significant main effects of team, F(1,213) = 10.68, p = .001, = .05, supporter emotion condition, F(2,213) = 15.93, p < .001,

= .13 and opponent emotion condition, F(2,213) = 10.72, p < .001,

= .09, emerged. These main effects were qualified by a team by supporter emotion condition, F(2,213) = 17.95, p < .001,

= .14, a team by opponent emotion condition, F(2,213) = 6.61, p = .002,

= .06 and an opponent by supporter emotion condition interaction, F(4,213) = 2.65, p = .035,

= .05.

Overall, the expertise of the supporter was rated as significantly higher (M = 5.27, SD = 1.29, CI95% 5.10; 5.45) than the expertise of the opponent (M = 4.99, SD = 1.55, CI95% 4.78; 5.18, t221 = 3.31, p = .001). Interestingly, perceived expertise was also influenced by the emotions shown by both expressers. Simple effects analyses were conducted separately for supporter and opponent.

Supporter

A 3 (opponent emotion condition) by 3 (supporter emotion condition) ANOVA, revealed significant main effects of opponent emotion condition, F(2,213) = 7.99, p < .001, = .07, supporter emotion condition, F(2,213) = 34.32, p < .001,

= .24, as well as a significant interaction, F(4,213) = 3.11, p = .016,

= .06 (see for means and standard errors).

Figure 5. Mean rated expertise of the supporter as a function of supporter and opponent emotion expression.

Overall, post-hoc tests revealed that the supporter’s expertise was rated as highest when the supporter showed happiness, followed by awe and lowest when the supporter showed a neutral expression. Further, the supporter’s expertise was rated significantly higher when the opponent showed a “matching” expression. That is, when the opponent showed happiness while the supporter showed neutrality and vice versa. In these cases, the two emotions lead to the same conclusion about the game outcome and therefore confirm each other.

Awe expressions shown by opponents increased perceptions of expertise when the supporter did not show happiness. Thus, participants again considered both expressions and while they overall considered the expertise of the supporter to be higher than the expertise of the opponent, this evaluation dropped when the opponent’s expression could not be easily reconciled with the expression of the supporter.

Opponent

For opponent expertise only, the main effect of opponent expression condition, F(2,213) = 9.73, p < .001, = .08, was significant, such that expressions of awe (M = 4.68, SD = 1.22, CI95% 4.40; 4.97) and happiness, (M = 4.63, SD = 1.24, CI95% 4.36; 4.90), which did not differ, signalled greater expertise than neutral expressions (M = 3.80, SD = 1.30, CI95% 3.48; 4.14).

Thus, for both supporters and opponents a neutral expression was seen as less indicative of expertise, which may suggest that this expression was considered a “default” that could also signal indifference. That the expertise of the opponent does not depend on the emotion of the supporter could be a sign that even though participants consider supporters as higher in expertise they do not trust their expression fully and therefore do not use it to gauge the opponent’s expertise. Hence, the expression of the opponent serves as a gauge for the reliability of the supporter’s expression but not vice versa.

Bias

An ANOVA with the within factor team (supporter vs. opponent) x and the between factors opponent emotion condition (awe, happiness, neutral) and supporter emotion condition (awe, happiness, neutral) revealed a significant main effect of team, F(1,213) = 11.59, p = .001, = .05, and a significant team by supporter emotion interaction, F(1,213) = 3.17, p = .044,

= .03. As expected, participants considered the expressions of the supporter to be more biased (M = 5.27, SD = 1.29, CI95% 5.09; 5.44) than those of the opponent (M = 4.89, SD = 1.56, CI95% 4.76; 5.18). No significant main effects or interactions emerged for perceived bias in the simple effects analyses conducted separately for each team.

Control

A 2 (team) by 3 (opponent emotion) by 3 (supporter emotion) ANOVA, revealed a team by supporter emotion condition, F(2,213) = 7.79, p = .001, = .07, and a team by opponent emotion condition interaction, F(2,213) = 9.97, p < .001,

= .07, as well as a supporter emotion condition by opponent emotion condition interaction, F(4,213) = 2.55, p = .040,

= .05. Simple effects analyses were conducted separately for supporters and opponents to follow up on the interactions.

Supporter control

A 3 (opponent emotion condition) by 3 (supporter emotion condition) ANOVA, revealed significant main effects of supporter emotion condition, F(2,213) = 7.40, p = .001, = .09, and opponent emotion condition, F(2,213) = 3.94, p = .021,

= .04.

Specifically, when supporters showed awe (M = 2.88, SD = 1.70, CI95% 2.49; 3.27), the expression was considered significantly less controlled than when they showed happiness (M = 3.49, SD = 1.65, CI95% 3.15; 3.83) or neutrality (M = 3.66, SD = 1.60, CI95% 3.58; 4.35), which did not differ. Yet, the expression of the opponent was also taken into consideration. Specifically, when the opponent showed awe (M = 3.86, SD = 1.71, CI95% 3.51; 4.22), the supporter’s expressions were considered to be more controlled than when the opponent showed neutrality, (M = 3.00, SD = 1.61, CI95% 2.58; 3.41) or happiness (M = 3.32, SD = 1.68, CI95% 2.94; 3.71), which did not differ.

Thus, the supporter’s awe was seen as a more spontaneous expression, congruent with the notion that this emotion is shown when someone is overwhelmed by an event (Hareli et al., Citation2019). Yet, both neutrality and happiness were seen as more controlled, matching the notion that participants felt that supporters may not always show what they feel.

Opponent control

A 3 (opponent emotion condition) by 3 (supporter emotion condition) ANOVA, revealed only a main effect of opponent emotion condition, F(2,213) = 6.08, p = .003, = .05, such that the opponent’s neutral expressions (M = 4.17, SD = 1.76, CI95% 3.71; 4.61) were considered to be significantly more controlled than their awe (M = 3.06, SD = 1.71, CI95% 2.70; 3.42) and happy expressions (M = 3.43, SD = 1.53, CI95% 3.09; 3.78), which did not differ. As neutral expressions were generally perceived as indicative of a bad performance, this may suggest that participants felt that an even more negative emotional reaction, such as anger or sadness, was suppressed. No other significant effects emerged for any of the reported analyses.

Discussion

The results of Study 2 suggest that participants use the emotional expressions of both supporter and opponent as well as their real world knowledge about these individuals’ motivations to assess the trustworthiness of the expressions shown. For an expression to be trustworthy, the expresser has to be competent and the expression unbiased and not masked or otherwise controlled. Overall, the findings support the notion that participants consider supporters to be more knowledgeable of the game but also as more biased in judgment and controlled in their expressions. As such, supporter expressions were perceived as less trustworthy.

These evaluations explain why participants relied more on the opponent’s expressions and the situational information signalled by that expression when evaluating aspects of that supporter’s behaviour than vice versa. In fact, the opponent’s expression is largely taken as is and ratings of the opponent’s expertise and control of their expression were not influenced by the supporter’s behaviour. The notion that the supporter’s expressions are considered to be more biased and controlled also explains the stronger effect of opponent emotion on supporter emotion found in Study 1. These findings further suggest that participants have naïve emotion theories regarding the appropriate emotional behaviours of spectators in a game.

General discussion

The present research provides evidence for the notion that when asked to rate the emotion of others, participants consider situational information and world knowledge about the situational dynamics, including whom to trust when making their judgment. Importantly, we could show that the situational information used may be derived from the very same expressions that participants were asked to judge. That is, we were able to show a bidirectional relationship between situational and expressive information.

Specifically, participants first use the expressions of others to form an impression of the eliciting event and then use this expression-derived situational information to further adjust their interpretation of these same expressions. This bidirectional relationship also extends to related ratings such as the ratings of expertise, bias and control in Study 2. In both studies, participants did not rely on a single source of information, be it the situation or the facial expression of either opponent or supporter, but rather considered all these pieces of information to form a holistic judgement.

We also found indications in Study 1 that in order to be used as information for perspective taking, a person’s expression has to be trusted. Study 2 showed that participants implicitly judge the likely trustworthiness of the expressions they are asked to rate and again do so by including information derived from the emotion expression of the respective other person and real world knowledge about their motivations. That is, not only judgments of emotion but also judgments of the spontaneity of the expression (or its authenticity) are influenced by reverse engineered social appraisals. Expressions that suggest that opponents and supporters agree on their perception of the situation are considered more trustworthy than expressions that lead to divergent meaning. Expressions that are trustworthy then are used to fine tune the perception of the other person’s emotion as shown in Study 1. The present results therefore substantiate the crucial prediction of the bidirectional model that both situational information and facial expressions enter into social appraisal processes.

Yet, the present research is not without limitations. First, participants had very limited knowledge of the game since its rules were unknown to them. We choose this strategy to control for individual differences in context knowledge. Yet, it is likely this forced participants to rely more on the reaction of spectators than might be the case in typical real-life situations, where people often have more specific situational knowledge. Further, many social contexts do not provide clear information regarding the motivations of the expressers. This may make it harder to interpret conflicting facial information from witnesses to an event. The degree to which such information is required for social appraisals is a question for future research. Also, the data were collected in the US. As such, cultural notions about “proper” sports spectator behaviour have certainly informed the judgments. In fact, the negative interdependence of the reactions of supporter and opponent are in part derived from such cultural notions. As such, cultural differences in the understanding of the roles of opponent and spectator may translate into differences in social appraisal outcomes. This is a question for future research.

The present findings point to the importance of situational information for the perception of emotions as suggested by constructivist approaches to emotion perception among others (Barrett et al., Citation2011; Hess & Hareli, Citation2016, Citation2017). However, constructionist approaches to emotion perception consider this a one-way street in which a clear situational signal guides the construction of meaning of an “inherently ambiguous” emotion signal (Barrett et al., Citation2011; Hassin et al., Citation2013, p. 60). By contrast, the present research shows that the emotion expressions were used by the participants to reverse engineer social appraisals in meaningful ways. Such, these expressions were meaningful in their own right. The bidirectional social perception model moves past the traditional view of uniform one directional emotion communication processes by positing one process that yields situational information (reverse engineering) and a second process (perspective taking) that is applied to modify the very source from which the situational information is derived.

It is important to note that in the present research participants and expressers not only did not know each other but really had no relationship with each other. Nonetheless participants relied on the expressers to inform them about the situation. However, as the reduced impact of supporter expressions on ratings of opponent emotions shows, this reliance is tempered by participants’ attributed trust to the emotion expressions. Study 2, in turn showed that participants seem to hold naïve theories about whom to trust in a game situation such as the one used here.

In fact, the present research shows that participants do not only use expressive and situational information but also their real world knowledge about game situations in general. In fact, when the two expressions did not match, it was real world knowledge about the negative interdependence of game outcomes that made a judgment possible. As such, the present research points to the importance of taking emotion perception research out of the sandbox provided by the typical context free stimuli and to acknowledge that because decoders use all information at their disposal when making emotion judgments, such stimuli do not elicit the same type of process that is engaged by richer stimulus material. Hence, to really understand emotion communication we have to study this process holistically by including all relevant sources of information.

In conclusion, the present research provided evidence that participants use not only facial expressions or situational information or their own naïve theories when making emotion judgments, but rather use all sources of information. In this they balance the information from each source, weigh it by its trustworthiness and adjust mismatches in line with their understanding of the situation. This implies on one hand that emotion recognition is a complex social act and on the other that both the situation and emotional facial expressions have well interpretable intrinsic meaning.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Barrett, L. F., Mesquita, B., & Gendron, M. (2011). Context in emotion perception. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 20(5), 286–290. doi: 10.1177/0963721411422522

- Buck, R. (1984). Nonverbal receiving ability. In R. Buck (Ed.), The communication of emotion (pp. 209–242). New York: Guilford Press.

- Clore, G. L., & Ortony, A. (2013). Psychological construction in the OCC model of emotion. Emotion Review, 5, 335–343. doi: 10.1177/1754073913489751

- Dailey, M. N., Cottrell, G. W., Padgett, C., & Adolphs, R. (2002). EMPATH: A neural network that categorizes facial expressions. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 14, 1158–1173. doi: 10.1162/089892902760807177

- Faucher, L. (2013). Comment: Constructionisms? Emotion Review, 5(4), 374–378. doi: 10.1177/1754073913489754

- Fischer, A., & Manstead, A. S. R. (2008). The social function of emotions. In M. Lewis, J. Haviland-Jones, & L. F. Barrett (Eds.), Handbook of emotions ( Vol. 3, pp. 456–468). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- Frijda, N. H. (1986). The emotions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hareli, S., Elkabetz, S., & Hess, U. (2019). Drawing inferences from emotion expressions: The role of situative informativeness and context. Emotion, 19, 200–208. doi: 10.1037/emo0000368

- Hareli, S., & Hess, U. (2010). What emotional reactions can tell us about the nature of others: An appraisal perspective on person perception. Cognition and Emotion, 24, 128–140. doi: 10.1080/02699930802613828

- Hassin, R. R., Aviezer, H., & Bentin, S. (2013). Inherently ambiguous: Facial expressions of emotions, in context. Emotion Review, 5(1), 60–65. doi: 10.1177/1754073912451331

- Hayes, A. F. (2017). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach (2nd ed.). New York: Guilford Publications.

- Hess, U., & Hareli, S. (2015). The role of social context for the interpretation of emotional facial expressions. In M. K. Mandal, & A. Awasthi (Eds.), Understanding facial expressions in communication (pp. 119–141). New York, NY: Springer.

- Hess, U., & Hareli, S. (2016). The impact of context on the perception of emotions. In C. Abell, & J. Smith (Eds.), The expression of emotion: Philosophical, psychological, and legal perspectives (pp. 199–218). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Hess, U., & Hareli, S. (2017). The social signal value of emotions: The role of contextual factors in social inferences drawn from emotion displays. In J. Russell, & J.-M. Fernandez-Dols (Eds.), The science of facial expression (pp. 375–392). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Hess, U., & Kirouac, G. (2000). Emotion expression in Groups. In M. Lewis & J. Haviland-Jones (Eds.), Handbook of emotion (2nd Ed, pp. 368–381). New York: Guilford Press.

- Hess, U., Landmann, H., David, S., & Hareli, S. (2017). The bidirectional relation of emotion perception and social judgments: The effect of witness’ emotion expression on perceptions of moral behaviour and vice versa. Cognition and Emotion, 1–14. doi: 10.1080/02699931.2017.1388769

- Kaiser, S., & Wehrle, T. (2001). Facial expressions as indicators of appraisal processes. In K. R. Scherer, A. Schorr, & T. Johnstone (Eds.), Appraisal processes in emotion: Theory, methods, research. Series in affective science (pp. 285–300). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Kirouac, G., & Hess, U. (1999). Group membership and the decoding of nonverbal behavior. In P. Philippot, R. Feldman, & E. Coats (Eds.), The social context of nonverbal behavior (pp. 182–210). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Mayer, R. C., Davis, J. H., & Schoorman, F. D. J. (1995). An integrative model of organizational trust. Academy of Management Review, 20(3), 709–734. doi: 10.5465/amr.1995.9508080335

- Robinson, M. D., & Clore, G. L. (2002). Belief and feeling: Evidence for an accessibility model of emotional self-report. Psychological Bulletin, 128, 934–960. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.128.6.934

- Roseman, I. J. (1991). Appraisal determinants of discrete emotions. Cognition & Emotion, 5, 161–200. doi: 10.1080/02699939108411034

- Scherer, K. R. (1987). Towards a dynamic theory of emotion: The component process model of affective states. Geneva Studies in Emotion and Communication, 1, 1–98. Retrieved from http://www.affective-sciences.org/node/402.

- Scherer, K. R. (1992). What does facial expression express? In K. Strongman (Ed.), International review of studies on emotion ( Vol. 2, pp. 139–165). Chichester: Wiley.

- Scherer, K. R., & Grandjean, D. (2008). Facial expressions allow inference of both emotions and their components. Cognition & Emotion, 22, 789–801. doi: 10.1080/02699930701516791

- Shiota, M. N., Keltner, D., & Mossman, A. (2007). The nature of awe: Elicitors, appraisals, and effects on self-concept. Cognition and Emotion, 21(5), 944–963. doi: 10.1080/02699930600923668

- Smith, C. A., & Scott, H. S. (1997). A componential approach to the meaning of facial expressions. In J. A. Russell, & J.-M. Fernández-Dols (Eds.), The psychology of facial expression (pp. 229–254). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.