ABSTRACT

Research on individual differences in the occurrence of relatively frequent facial displays is scarce. We examined whether (1) individuals’ spontaneous facial expressions show a relatively frequent pattern of AUs (referred to as Personal Nonverbal Repertoires or PNRs), and (2) whether these patterns are associated with self-reported social and emotional styles. We videotaped 110 individuals during 10 minutes in 2 different contexts and manually FACS coded 18 AUs. Subsequently, participants completed questionnaires regarding individual differences in social and emotional styles: BIS/BAS, interpersonal orientation, conflict handling style, and emotion regulation (reliably reduced to 4 factors: Yielding, Forcing, Compromising and Extraversion). We found five patterns of PNRs: Smiling (AU6,12), Partial Blinking, Drooping (AU41, 63), Tensed (AU1 + 2, 4, 7, 23), and Eyes widening (AU5). Three PNRs showed weak to moderate correlations with individual differences in social and emotional styles (based on EFA): Smiling is associated with Compromising and Extraversion, Drooping with Yielding, and Partial Blinking is negatively correlated with Extraversion. These findings suggest that some of an individual’s frequent facial action patterns are associated with specific styles in social and emotional interactions.

Personal Nonverbal Repertoires: individual differences in facial displays

Some people constantly raise their eyebrows, others frequently tighten their lower eyelids, and still others continuously smile. Are these purely coincidental phenomena, or could they reflect an individual’s style in social interactions? We argue that there are individual differences in nonverbal expressions, which we refer to as Personal Nonverbal Repertoire (PNRs). The term is broad as it may encompass body posture and gestures, but here we focus on facial displays.

Some early work has already suggested the possible existence of individual differences in facial micromovements (Piderit, Citation1867; Ekman & Friesen, Citation2003). To date, however, facial displays have been primarily considered as momentary states, described as read-outs of emotions (e.g. Ekman & Friesen, Citation2003), signals of social intentions (the Behavioral Ecology View, Fridlund, Citation1994), states of action readiness (Frijda & Tcherkassof, Citation1997), or as more general motivational states, such as arousal and valence (e.g. Russell, Citation1997). These ideas have been tested in many studies in which participants were asked what emotions or motivational states they perceived in targets’ faces (see e.g. Keltner et al., Citation2016 for an overview).

Whereas facial reactions are clearly situation-contingent, that is, responses to an event, they can also be considered as more stable dispositions: individuals may systematically differ in the frequency with which they show specific facial reactions, across specific situations. Following discussions in personality research (see also Fleeson & Noftle, Citation2008; Geukes et al., Citation2017; Mischel & Shoda, Citation1995), we believe that the occurrence of a nonverbal behaviour in an individual can be situation-contingent, but at the same time relatively stable over time. Thus, whereas everyone may smile more at a wedding rather than a funeral, some people may smile more than others in both contexts. In the present research, we are interested in such stable individual differences that occur across situations. Our first question is whether we can find support for the idea that there are individual differences in the relative frequency (see also Fleeson & Noftle (Citation2008)) with which people show specific facial actions (PNR) over time and across situations. We use the relative frequency of AUs within an individual (and not across individuals), in order not to equate it with general expressiveness. For example, the more frequent smiling of individuals would not inform us about their PNR, if they also show other facial expressions more frequently.

The subsequent question is whether relative frequent AUs group together in meaningful factors. Literature on the relation between emotions and facial actions, suggests that this is the case. However, there is little research on the occurrence of patterns in spontaneous facial behaviour. In one study, Stratou et al. (Citation2017) used automated AU recognition (CERT) to measure naturally occurring facial behaviour, including three large data sets using different contexts. They found 6 factors (factor loadings above .30), based on 16 AUs: Enjoyment smile (AU6, 7, 12), Eyebrows up (AU1, 2), Mouth open (AU20, 25, 26), Mouth Tightening (AU14, 17, 23), Eye tightening (AU4, 7, 9) and Mouth Frown (AU10,15,17). These factors were largely stable across the different datasets, thus suggesting that factors of AUs can be found on the basis of naturally occurring facial expressions.

A second question is whether individual patterns of facial behaviour can be related to individual differences in social and emotional styles. We use the term social and emotional styles here to refer to a general response pattern in interacting with others and coping with emotions. For example, an open, affiliative approach to others, may be accompanied by frequent smiling more than by frequent frowning. We thus examined whether the relative frequent occurrence of specific facial actions is associated with self-reported individual differences in interactions with others (De Dreu et al., Citation2001; Wiggins, Citation1979) and regulation of emotions and stress (Gross & John, Citation2003).

We included different types of measures to tap social and emotional styles. First, we measured two dimensions in the interpersonal domain: extraversion (vs introversion) and dominance (vs submissiveness), which have been mentioned as part of the circumplex model of interpersonal behaviour, as well as the five-factor model of personality (Trapnell & Wiggins, Citation1990). In addition, we included measures of different styles in conflict situations. De Dreu et al. (Citation2001) distinguish 5 different styles for dealing with conflicting situations, based on two dimensions: concern for others and concern for oneself. High concern for oneself and for others leads to Problem Solving, whereas high concern for oneself and low concern for others leads to Forcing, and high concern for others and low concern for oneself leads to Yielding, neutral concern for both oneself and others leads to Compromising, and finally low concern for both oneself and others leads to Avoiding.

Social and emotional styles may also be reflected in individual differences in emotion regulation. Gross and John (Citation2003) distinguish two types of emotion regulators: people who suppress their emotions and people who re-appraise the emotional event. This research has typically shown that re-appraisers are better able to decrease the intensity of their negative emotions, compared to suppressors. Suppressors still experience a fair amount of negative emotions, even though they try not to show it. Suppressors may thus still show facial activity (non-verbal leakage), but it will be subdued. Finally, people also differ in how nervous they are to avoid punishment versus how positive they are in achieving their goals. On the basis of Gray’s Reinforcement Sensitivity Theory (Gray, Citation1987) two dimensions of personality have been proposed: anxiety and impulsivity. These are based on individuals’ sensitivity of two neurological systems: the Behavioral Inhibition System (BIS), and the Behavioral Approach System (BAS). BIS is sensitive to punishment and negative affect, whereas BAS is sensitive to reward and positive affect. These two systems have been investigated in many studies and related to differences in personality as well as to various forms of psychopathology (see Bijttebier et al., Citation2009). Here we use the self-report scales of BIS/BAS (Carver & White, Citation1994), because they have been shown to reflect differences in negative affect, especially anxiety and nervousness (BIS) and positive affect (BAS).

To date, only a few studies have examined facial actions in relation to stable individual differences, such as temperament or general mood (see ). Four factors of facial actions have been identified that could form a basis for PNRs. It should be kept in mind, however, that in previous studies only posed, and not spontaneous expressions were measured, and they exclusively focused on what characteristics observers infer from these expressions. Here we explore whether the production of facial expressions is associated with self-reported social and emotional styles.

Table 1. Facial actions in relation to individual differences.

The first factor is AU6 (cheek raiser) and AU12 (lip corner puller), sometimes also combined with AU7 (eye lid tightener; Stratou et al., Citation2017). The combination of these AUs reflect a positive, affiliation-oriented approach, which may be associated with Extraversion and positive goal achievement (BAS), and with positive ways of coping with problems (Compromising, Problem solving or Reappraisal; see Fridlund, Citation1994; Frijda & Tcherkassof, Citation1997; Jäncke, Citation1993; Kring & Sloan, Citation2007).

A second factor could be AU1 (inner brow raiser), AU2 (outer brow raiser) and AU5 (upper eyelid raiser), which reflects an active outward orientation: high arousal, and high attention and focus. This PNR could be negatively associated with Suppression (not showing one’s feelings) and positively with any of the styles that we measured that requires an active focus.

A third factor could be based on the combination of AU4 (corrugator), AU7 (eyelid tightener) and AU23 (lip tightener), which has been described as indicating concentration, but also signalling a negative hedonic tone, and the readiness to attack. This PNR may therefore be associated with active and coercing interaction styles, such as Forcing and Dominance.

Finally, AU41 (eyelids drooping) has been identified as reflecting low arousal and a low state of action readiness and may be therefore be associated with Yielding and Submissiveness.

The current study

We use a novel approach and examine spontaneous facial actions in relation to self-reported individual differences in social and emotional styles. The research is exploratory in nature and aims to answer two questions. First, do individuals’ spontaneous facial expressions show a relatively frequent occurrence of AUs? If so, can we identify specific patterns of AUs that often occur simultaneously, in line with patterns reported in the literature ()? The second question concerns the relation between facial actions and self-reported social and emotional styles. We included measures that would tap individual differences in how people relate to others (interpersonal dominance, extraversion, conflict styles) and how they cope with their emotions (emotion regulation, BIS/BAS).

Method

Participants and design

Participants were 110 Dutch men (N = 48; Mage = 45; SD = 13.81) and women (N = 62; Mage = 45; SD = 15.37). Their ages ranged from 20 to 78 and they had different educational levels. All procedures involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed written consent was obtained by email from all individual participants included in the study. A sensitivity analysis conducted in G-power suggested that with α = .05 and 110 participants, our main hypothesis testing (i.e. analyses of correlations) would have a power of 0.80 to detect a small to medium effect (r = 0.26).

Procedure

Upon arrival, every participant received an instruction about the procedure, stating that they would participate in video recorded sessions and afterwards would fill in 5 questionnaires. After the briefing, they started with answering questions in two different ways (see Supplemental Materials 1 for more details).

Solo context

Alone in a room with only a computer projecting questions. The participant could set the pace of the questions by mouse-clicks. The questions started factual but became more personal and intimate during the session.

Interview context

Sitting at a table in front of an Interviewer. The questions also focused on specific emotional experiences (fear, anger, pride). The Interviewer set the pace of the questions and followed up with questions on initial answers from the participant.

All interviews were conducted by 3 interviewers, alternately: 2 females, 1 male. The interviewers were not acquainted with the participants and conducted the interviews in a neutral manner. Because there is some evidence (Hess & Bourgeois, Citation2010) that the sex of the interviewer may elicit different facial behaviours, we checked the effects of interviewer’s sex on the occurrence of facial actions but did not find any significant differences (see Supplemental Materials 2).

Questionnaires (see Supplemental Materials 3 for sample items)

Behavioral Inhibition System /Behavioral Approach System (BIS/BAS; Carver & White, Citation1994). Scores were aggregated as BIS (Cronbach’s α = .77) or BAS (Cronbach’s α = .79).

Interpersonal Behavior (Wiggins, Citation1979): We used 4 sets of items, based on two dimensions from the Interpersonal Adjective Scales (IAS-R, Wiggins, Citation1984): Dominance (Cronbach’s α = .82) versus Submissiveness (Cronbach’s α = .80) and Extraversion (Cronbach’s α = .82) versus Introversion (Cronbach’s α = .82).

Dutch Test for Conflict Handling (De Dreu et al., Citation2001): measures the preferred style(s) of conflict handling at work by rating 20 statements on a scale of 0–6, measuring five styles: forcing (Cronbach’s α = .76), avoiding (Cronbach’s α = .75), yielding (Cronbach’s α = .62), compromising (Cronbach’s α = .67) and problem solving (Cronbach’s α = .77).

Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (Gross & John, Citation2003): taps individual differences in emotion regulation style by either reappraisal (5 statements) or suppressing negative feelings (5 statements). Cronbach’s α for reappraisal is .73 and for suppression .83.

Emotional Well-being (Hess & Blairy, Citation2001). This questionnaire was used to measure the level of Stress (Cronbach’s α = .68).

Facial coding

Per participant a total of 10 min video was coded. Ten coders coded the video material. Interpersonal reliability was tested by a certified FACS-coder who coded video materials for 24 participants and double coded materials coded by all the different coders. She was blind to our hypotheses and unaware of the different contexts (Solo or Interview). Average Intra class correlation (ICC) coefficients per AU between the FACS-coder and the other coders ranged between .986 and .999, p < .01 (Supplemental Materials 4, Table S1). We initially coded 17 existing Action Units, using FACS (Ekman & Friesen, Citation1978) and one action that is not part of FACS, but has been previously observed by the first author, namely PartialBlink. Because we did not aim to study highly idiosyncratic PNRs, we kept 12 displays in the analyses that occurred in 3% or more of the frames coded: AU1, AU1plus2, AU4, AU5, AU6, AU7, AU12, AU23, AU41, AU45, AU63 and PartialBlink (Supplemental Materials 5, 6, Table S2, Figure S1).

Results

Relative frequency of action units per individual

We first examined the relative frequency of single AUs for each individual, by checking whether any of a participant’s single AU had a frequency that was higher than the median frequency score of the total of AUs for that same individual, calculated separately for each context. We used the median rather than the average frequency to minimise the impact of outliers. Thus, we operationalized a PNR as the relative high frequency of AUs within an individual in a specific context. This comparison showed that all 110 participants had one or more AU scores above their individual median in each context (see Supplemental Materials 7 for more details).

Consistent occurrence of similar action units per individual across two contexts

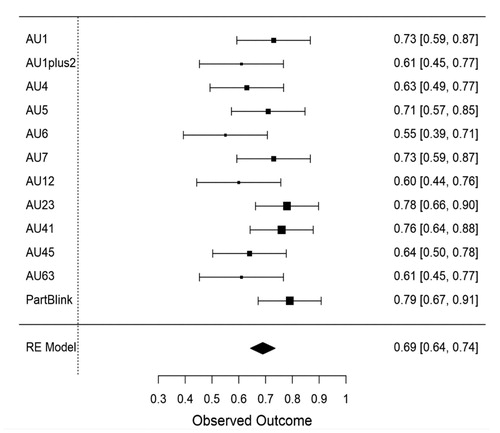

To identify a robust pattern of individuals’ consistency of facial display across the two contexts (see Table S3 in the Supplemental Materials for the means in both contexts), we calculated the (Spearman) correlation of AU activity between the solo and the interview contexts, separately for each AU (see for the coefficients). We then used the meta-analysis method to identify the robust nature of this test, beyond a specific AU. Because we recorded a random selection of different AUs, we conducted a random-effects meta-analysis (using the JASP 0.9.2 software), which included twelve different tests of the consistency (i.e. relation) between individuals’ facial displays across the solo and the interview contexts. The meta-analysis yielded a strong positive relationship, estimated as .69, 95% CI [.64, .74], Z = 29.412, p < .001. Furthermore, we calculated the heterogeneity of the observed similarities to test whether our estimate of the average relation (r = .69) can be generalised. Findings pointed toward small variance of the observed effect, Q = 14.66, I2 = 0.25, df = 11, p = .20, implying that the estimate can be generalised across the AUs included in the analysis. In other words, the average correlation between the two contexts of .69, suggests that 47% (.69*.69 = .47) of the individuals’ facial display in one context can be predicted from the activation in the other context. shows the Forest plot of individual consistency of facial displays across the Solo and Interview contexts. The effect was estimated using the random effects (RE) model.

Figure 1. Forest plot of individual consistency of facial display across the Solo and Interview context. For each test of consistency, the size of the box represents the mean effect size estimate, which indicates the weight of that AU in the meta-analysis. Numerical values in each row indicate the mean and 95% confidence interval of effect size (i.e. correlation) estimates in bootstrapping analyses.

PNRs: relations between AUs

The next question was whether we can find support for specific patterns of AUs. We first examined all the simple correlations between each pair of two AUs. Since the variables were not all normally distributed (i.e. AU41: ZSkeweness = 2.34; ZKurtosis = 2.58; all other AUs had ZSkeweness and ZKurtosis values < 2), we used Spearman’s correlation coefficient to calculate the relation between all pairs of AUs. The findings show that all AUs were weakly to strongly, but significantly, related to at least one other AU, except AU41 (see Supplemental Materials, Table S4).

Factor analysis of AUs

Next, we tried an Exploratory Factor Analysis to detect underlying factors in the facial displays. However, the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) test for sampling adequacy showed a KMO value of .548, which is below standard of acceptability (KMO > .60; Kaiser, Citation1974). To reduce the complexity of the data, we submitted all AUs to a Principal Components Analysis, with Oblimin rotation (see ). The rotated solution accounted for all 12 AUs (extraction communalities ranged from .48 to .82), explained 65% of AUs variance, and showed five factors with eigenvalues above 1.

Table 2. Factor loadings of individual AUs after EFA.

The first factor comprised AU6, AU12 and AU7 (eigenvalue = 2.45) and accounted for 20% of the variance. We refer to this factor as Smiling. The second factor (eigenvalue = 1.94) accounted for 16% of the variance, including four AUs: AU7 (negative), AU45 (negative), PartialBlink, and AU1 (negative). We refer to this as Partial Blinking. The third factor (eigenvalue = 1.28) included two AUs (AU41, AU63), and accounted for 11% of the variance. We refer to this as Drooping. The fourth factor (eigenvalue = 1.13) accounted for 9% of the variance, including AU4, AU7, and AU23, but also AU1plus2. We refer to this factor as Tensed. The fifth factor (eigenvalue = 1.07), Eyes Widening, accounted for 9% of the variance and included mainly AU5.

Self-reported individual differences in social and emotional styles

All scales measuring different aspects of social and emotional styles were reliable (as reported in the methods section). We examined the underlying factor structure of all self-reported individual difference measures and found that the sample was adequate for factor analysis of these variables (KMO = .73). We performed an exploratory factor analysis. To determine the number of factors, we used the methods of parallel analysis (see Hayton et al., Citation2004; Horn, Citation1965). This procedure suggests that all scales can be represented using four latent factors. Averaging the (standardised) scores for each factor across the entire sample resulted in four factors that we labelled: (1) Yielding (including Yielding, Submissiveness, BIS, Stress), (2) Forcing (including Forcing, Dominance, BAS, -reversed- Avoiding), (3) Compromising (including Compromising, Reappraisal, Problem Solving), and (4) Extraversion (including Extraversion, -reversed- Introversion, -reversed- Suppression; Supplemental materials, Table S5).

The relationship between PNRs and individual differences

In order to examine the second question, we first correlated the factor loadings of the AUs with the means of the self-report scales (see ). We found significant positive correlations between Smiling and reappraisal, BAS and extraversion; between Partial Blinking and suppression; between Drooping and yielding, BIS, and stress; between Tensed and problem solving; and between Eyes Widening and reappraisal.

Table 3. Correlations between Personal Nonverbal Repertoires (PNR) and self-report scales.

Next, we correlated the factor loadings of AUs with the four factor loadings of the self-report scales. We found the following significant correlations: Smiling correlates with Compromising (r = .20, p < .05) and Extraversion (r = .26, p < .01); Partial Blinking correlates negatively with Extraversion (r = -.21, p < .05), and Drooping correlates with Yielding (r = .31, p < .01). There were no significant correlations for Tensed and Eyes Widening (see Supplemental materials, Table S6 for all correlations).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study that examines individual differences in relatively frequent patterns of spontaneous facial actions and their relations with self-reported characteristics. We found support for the concept of Personal Nonverbal Repertoires: each individual in our sample showed one or more facial actions more frequently across two contexts than the median of all facial actions of that individual. We found five PNRs, partly in line with previous research, and examined their relationship with social and emotional styles. The first PNR was defined as Smiling, consisting of smiling (AU12), raising the cheek (AU6), and tightening the lower eyelid (AU7), suggesting authentic and intense, rather than polite smiling. This pattern has been found in previous research (referred to as Enjoyment Smile, Stratou et al., Citation2017, or Duchenne smile, Ekman & Friesen, Citation2003), although not always including AU7. As expected, Smiling was associated with a positive and extraverted interaction style, aimed at coping with problems and finding compromises.

The second PNR which we labelled Partial Blinking consisted of Partial Blinking, and was negatively associated with blinking (AU45), raising the lower eyelid (AU7) and lifting the inner eyebrows (AU1). The negative factor loadings of AU1, AU7, and AU45 suggests passivity, because raising the inner eyebrow, tightening the eyelid and blinking all signal an active and alert gaze. The negative association with extraversion fits with this explanation and suggests a positive association with suppression of emotions and introversion.

The third PNR was labelled Drooping, reflecting low arousal, and in line with expectations consisted of drooping eyelids (AU41) and white under the iris (AU63). Drooping was positively associated with yielding, implying a submissive and anxious interaction style based on stress. The question is how Partial Blinking and Drooping can be distinguished, as they both represent a passive stance, but are correlated with different social and emotional styles. Whereas Partial Blinking seems mainly associated with not showing any feelings (i.e. a poker face), Drooping suggests anxiety and giving in. This may indicate that Drooping provides a more explicit signal to a conversation partner than is the case for Partial Blinking.

The fourth PNR was labelled Tensed, consisting of frowning (AU4), eyelid tightener (AU7), lip tightener (AU23), as well as the brow raiser (AU1 + 2). The combination of AU4, AU7 and AU23 has been previously found (e.g. Ekman & Friesen, Citation2003; Fridlund, Citation1994; Frijda & Tcherkassof, Citation1997; Russell, Citation1997), and this combination has been related to concentration, but also to antagonism, displeasure and the readiness to attack. The combination between AU1 + 2, AU4, and AU7 is often perceived as fear, whereas AU23 may point to the down regulation of this emotional state, signalling tenseness. However, we did not find a correlation between this PNR and the self-report factors, although the correlations with the single scales show a positive correlation with problem solving and a negative correlation with suppression. In other words, people with a Tensed PNR may on the one hand show focus and concentration, while also suppressing their feelings of anxiety.

Finally, the fifth PNR that we termed Eyes Widening consisted of a single AU, the upper lid raiser (AU5), and was not associated with inner and outer brow raiser (AU1 + 2), as previous research suggested. We did not find a correlation with the self-report factors. There was however a positive correlation with reappraisal and a negative with compromising.

It should be noted that single facial actions may send out a different signal when occurring in different combinations with other AUs. This is clearly the case for the eyelid tightener (AU7), which was associated with three PNRs, Smiling, Partial Blinking (negatively) and Tensed. It has previously been argued that the activation of AU7 is strongly associated with AU6, because it is controlled by the same muscle. Thus, AU6 in combination with AU7 can be a clear signal of authentic happiness or amusement. However, in combination with AU4 and AU23, it may point to a more tense face, reflecting the assessment of something negative that one needs to regulate. We should also note that the study by Stratou et al. (Citation2017) found some different factors than we did. This may also point to the fact that the inclusion of different AUs may lead to different patterns. Stratou et al. (Citation2017) also included very infrequent AUs and used automatic emotion recognition software (which cannot detect all facial actions that we included), and used a different cut-off point (.30 versus .40). Such differences may account for the emergence of different factors of AUs.

We found significant and moderate correlations between three AU factor loadings and self-report factor loadings. The size of these correlations is comparable with correlations between AUs and self-reported measures in other studies (see e.g. Kring & Sloan, Citation2007; Mauersberger et al., Citation2015; Stratou et al., Citation2017). The fact that we did not find significant correlations for Tensed or Eyes Widening could be due to the fact that we FACS coded spontaneous displays in dynamic contexts, resulting in more individual and situational variation, and thus more statistical noise than in more standardised settings. In general, correlations between behavioural or implicit measures, such as facial expressions, and self-report measures, tend to be low (see e.g. Mauss et al., Citation2005), however.

Limitations, strengths and future research

Although our sample size was sufficient, the variation in AUs is large, and more research is needed to establish the robustness of these specific PNRs. For example, we studied facial actions only in two different contexts, and thus we cannot draw conclusions about the extent to which a PNR is variable across more different contexts (see also Fleeson, Citation2004). However, it should be mentioned, that FACS coding spontaneous facial expressions of a sample in more different contexts will be very time consuming. Another limitation is that the self-report questionnaires tapped general dispositions, but not all of these were applicable to the study context. This was especially the case for conflict management styles, as the context in which the facial expressions were recorded was not a conflict situation.

In sum, we showed that all participants display one or more facial actions relatively frequently and we found evidence for five factors of facial actions, referred to as Personal Nonverbal Repertoires (PNRs). Three of these are associated with specific social and emotional styles in interactions: Smiling is associated with compromising and extraversion, Drooping with yielding, and Partial Blinking is negatively correlated with extraversion. These findings are partly in line with previous results and theorising (Jäncke, Citation1993; Kring & Sloan, Citation2007; Mauersberger et al., Citation2015; Russell, Citation1997), but most of these studies were based on the observation of facial expressions, rather than the production of facial actions. Our study also entailed a few other important differences with previous research: we coded 18 different AUs, rather than only a few action units, which occurred spontaneously in an interactive setting, and we only included the relative frequent AUs. The correlations with social and emotional styles show that there is at least initial support for the idea that individual differences in some relatively frequent facial actions are related to specific styles in social interactions. Thus, the focus of this study is novel and broader than most previous studies (but see Stratou et al., Citation2017). Replication of these findings is necessary, however, in order to examine whether the PNRs that we found are robust or show variation in different samples and contexts.

Supplementary_Material

Download MS Word (74.9 KB)Acknowledgments

We want to thank Corinne Brenner, Laura Ilgen and Sara Makkenze for their invaluable support in carrying out this study, and Han van der Maas and Robert Zwitser for their statistical advice.

Disclosure statement

In accordance with Taylor & Francis policy and my ethical obligation as a researcher, I am reporting that I have a financial and/or business interest in a company that may be affected by the research reported in the enclosed paper. I have disclosed those interests fully to Taylor & Francis, and I have in place an approved plan for managing any potential conflicts arising from that involvement. Herman A. Ilgen.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in Open Science framework at https://osf.io/dj7km/?view_only=13f397c89d5c4350a23a4fb50adb39e3.

References

- Bijttebier, P., Beck, I., Claes, L., & Vandereycken, W. (2009). Gray’s reinforcement sensitivity theory as a framework for research on personality-psychopathology associations. Clinical Psychology Review, 29(5), 421–430. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2009.04.002

- Carver, C. S., & White, T. L. (1994). Behavioral inhibition, behavioral activation and affective responses to impending reward and punishment: The BIS-BAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67(2), 319−333. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.67.2.319

- De Dreu, C. K. W., Evers, A., Beersma, B., Kluwer, E. S., & Nauta, A. (2001). A theory-based measure of conflict management strategies in the workplace. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 22(6), 645–668. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.107

- Ekman, P., & Friesen, W. V. (1978). The facial action coding system. Consulting Psychologists Press.

- Ekman, P., & Friesen, W. V. (2003). Unmasking the face. A Guide to Recognizing Emotions from Facial Clues. Los Altos, CA: Malor Books.

- Fleeson, W. (2004). Moving personality beyond the person-situation debate. The challenge and the opportunity of within-person variability. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 13(2), 83–87. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0963-7214.2004.00280.x

- Fleeson, W., & Noftle, E. E. (2008). Where does personality have its influence? A supermatrix of consistency concepts. Journal of Personality, 76(6), 1355–1386. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2008.00525.x

- Fridlund, A. J. (1994). Human facial expression: An evolutionary view. Academic Press.

- Frijda, N. H., & Tcherkassof, A. (1997). Facial expressions as modes of action readiness. In J. A. Russell, & J. M. Fernandez-Dols (Eds.), The psychology of facial expression (pp. 103–132). Cambridge University Press.

- Geukes, K., Nestler, S., Hutteman, R., Küfner, A. C. P., & Back, M. D. (2017). Trait personality and state variability: Predicting individual differences in within- and cross-context fluctuations in affect, self-evaluations, and behavior in everyday life. Journal of Research in Personality, 69, 124–138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2016.06.003

- Gray, J. A. (1987). The psychology of fear and stress. Cambridge University Press.

- Gross, J. J., & John, O. P. (2003). Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: Implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(2), 348–362. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.85.2.348

- Hayton, J. C., Allen, D. G., & Scarpello, V. (2004). Factor retention decisions in exploratory factor analysis: A tutorial on parallel analysis. Organizational Research Methods, 7(2), 191–205. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428104263675

- Hess, U., & Blairy, S. (2001). Facial mimicry and emotional contagion to dynamic emotional facial expressions and their influence on decoding accuracy. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 40(2), 129–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0167-8760(00)00161-6

- Hess, U., & Bourgeois, P. (2010). You smile − I smile: Emotion expression in social interaction. Biological Psychology, 84(3), 514–520. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsycho.2009.11.001

- Horn, J. L. (1965). A rationale and test for the number of factors in factor analysis. Psychometrika, 30(2), 179–185. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02289447

- Jäncke, L. (1993). Different facial EMG-reactions of extraverts and introverts to pictures with positive, negative and neutral valence. Personality and Individual Differences, 14(1), 113–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/0191-8869(93)90180-B

- Kaiser, H. F. (1974). An index of factorial simplicity. Psychometrika, 39, 31–36.

- Keltner, D., Tracy, J., Sauter, D. A., Cordaro, D. C., & Galen, M. (2016). Expression of emotion. In L. Feldman Barrett, M. Lewis, & J. M. Haviland-Jones (Eds.), Handbook of Emotions (fourth Edition, pp. 467–482). The Guilford Press.

- Kring, A. M., & Sloan, D. M. (2007). The Facial Expression Coding System (FACES): development, validation, and utility. Psychological Assessment, 19(2), 210–224. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.19.2.210

- Mauersberger, H., Blaison, C., Kafetsios, K., Kessler, C., & Hess, U. (2015). Individual differences in emotional mimicry: Underlying traits and social consequences. European Journal of Personality, 29(5), 512–529. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.2008

- Mauss, I. B., Levenson, R. W., McCarter, L., Wilhelm, F. H., & Gross, J. J. (2005). The tie that binds? Coherence among emotion experience, behavior, and physiology. Emotion, 5(2), 175–190. https://doi.org/10.1037/1528-3542.5.2.175

- McCrae, R. R., & Costa Jr, P. T. (1989). The structure of interpersonal traits: Wiggins’s circumplex and the five-factor model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 56(4), 586–595. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.56.4.586

- Mischel, W., & Shoda, Y. (1995). A cognitive-affective system theory of personality: Reconceptualizing situations, dispositions, dynamics, and invariance in personality structure. Psychological Review, 102(2), 246–268. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.102.2.246

- Piderit, T. (1867). Wissenschaftliches System der Mimik und Physiognomik. Detmold Verlag.

- Russell, J. A. (1997). Reading emotions from and into faces: Resurrecting a dimensional-contextual perspective. In J. A. Russell, & J. M. Fernandez-Dols (Eds.), The psychology of facial expression (pp. 295–320). Cambridge University Press.

- Stratou, G., Van der Schalk, J., Hoegen, R., & Gratch, J. (2017). Refactoring facial expressions: An automatic analysis of natural occurring facial expressions in iterative social dilemma. Seventh International Conference on Affective Computing and Intelligent Interaction (ACII). October 23-26, 2017.

- Trapnell, P. D., & Wiggins, J. S. (1990). Extension of the interpersonal Adjective scales to include the Big five dimensions of personality. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 59(4), 781–790. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.59.4.781

- Wiggins, J. S. (1979). A psychological taxonomy of trait-descriptive terms: The interpersonal domain. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37(3), 395–412. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.37.3.395

- Wiggins, J. S. (1984). The interpersonal adjective scales-revised. Department of Psychology, University of British Columbia.