ABSTRACT

Research has identified three different types of smiles – the reward, affiliation and dominance smile – which serve expressions of happiness, connectedness, and superiority, respectively. Examining their explicit and implicit evaluations by considering a perceivers’ level of social anxiety and psychopathy may enhance our understanding of these smiles’ theorised meanings, and their role in problematic social behaviour. Female participants (N=122) filled in questionnaires on social anxiety, psychopathic tendencies (i.e. the affective-interpersonal deficit and antisocial lifestyle) and callous–unemotional (CU) traits. In order to measure explicit and implicit evaluations of the three smiles, angry and neutral facial expressions, an Explicit Valence Rating Task and an Approach-Avoidance Task were administered. Results indicated that all smiles were explicitly evaluated as positive. No differences in implicit evaluations between the smile types were found. Social anxiety was not associated with either explicit or implicit smile evaluations. In contrast, CU-traits were negatively associated with explicit evaluations of reward and dominance smiles. These findings support the assumptions of non-biased explicit information processing in social anxiety, and flattened emotional sensitivity in CU-traits. The importance of a multimethod approach to enhance the understanding of the effects of smile types on perceivers is discussed.

From a social-functional perspective (Keltner & Haidt, Citation1999; Niedenthal et al., Citation2010), at least three different types of smiles with distinct morphologies, as well as distinct meanings and functions can be identified. First, symmetrical smiles together with raised eye brows express happiness and social approval (reward smile). Second, symmetrical smiles and a lowered upper lip signal the willingness to bond socially (affiliation smile). Finally, asymmetrical smiles, a wrinkled nose and a raised upper lip express dominance and superiority (dominance smile; Martin et al., Citation2017; Niedenthal et al., Citation2010; Rychlowska et al., Citation2017). Despite the growing body of research showing that the reward, affiliation and dominance smiles have different, namely positive and negative, functions (Martin et al., Citation2018, Citation2021; Orlowska et al., Citation2018; Rychlowska et al., Citation2017, Citation2021), many studies used smiles homogenously to represent positive social stimuli.

Although these studies did not differentiate between different smile types, they suggest that certain perceiver characteristics are related to differences between explicit and implicit evaluations of both positive and negative facial expressions (Eisenbarth et al., Citation2008; Heuer et al., Citation2007; von Borries et al., Citation2012). In particular, this was observed for psychopathic traits and social anxiety: Aberrant implicit evaluations of facial expressions, in the form of impulsive approach-avoidance reactions, were observed. These might in turn explain problematic social behaviour, such as aggression and withdrawal, as seen in psychopathic traits and social anxiety, respectively (Dapprich et al., Citation2021; Heuer et al., Citation2007; von Borries et al., Citation2012). In order to further validate the distinct positive and negative meanings of the three smiles, the current study therefore investigated whether their explicit and implicit evaluations differ as a function of the perceiver’s social anxiety and psychopathic traits.

The distinctiveness of the reward, affiliation and dominance smile has been well underpinned by both explicit and implicit assessments. With regard to explicit assessments, such as recognition tasks, it has been found that the reward, affiliation and dominance smile were generally recognised as such (Orlowska et al., Citation2018; Rychlowska et al., Citation2017). Perceivers also recognised the positive meaning of the reward smile by assuming that expressers intend to convey happiness, joy and contentment. The same was true for the negative meaning of the dominance smile, which was interpreted as conveying superiority, disapproval and contempt (Martin et al., Citation2021; Orlowska et al., Citation2018; Rychlowska et al., Citation2017). However, the meaning of the affiliation smile, namely promoting social connectedness, could not be differentiated from the meaning of the reward smile (Orlowska et al., Citation2018; Rychlowska et al., Citation2017), and its expression was labelled as faked (Martin et al., Citation2021). Yet, another study showed that opponents who expressed the affiliation smile, as compared to the other two smiles, were assumed to have less negative intentions and a greater willingness to repair the relationship after breaches of trust in economic games (Rychlowska et al., Citation2021). Thus, when seen out of context, positive intentions communicated by the affiliation smile might be more difficult to understand (Martin et al., Citation2021). Next to context information, perceiver characteristics may be crucial to recognise the meaning of the smiles.

Implicit assessments, such as physiological measurements, further support the positive meanings of both the reward smile and the affiliation smile, and the negative meaning of the dominance smile. During a social speech task, male participants who faced observers who expressed reward or affiliation smiles showed lower stress responses (i.e. decreased cortisol reactivity), whereas male participants who faced observers who expressed dominance smiles showed higher stress responses (i.e. increased cortisol reactivity; Martin et al., Citation2018). However, participants with higher baseline high-frequency heart rate variability (HF-HRV), i.e. an index of emotion recognition abilities (Lischke et al., Citation2017; Quintana et al., Citation2012), showed the lowest stress responses when confronted with the affiliation smile (i.e. decreased heart rate) and the highest stress responses when confronted with the dominance smile (i.e. increased cortisol reactivity), respectively (Martin et al., Citation2018). Thus, perceiver characteristics seem to play a role in the recognition of the positive and negative meanings of different smiles.

Two social dysfunctions that are related to biased explicit and implicit responses to positive and negative facial expressions are social anxiety and psychopathic tendencies. While social anxiety is defined by high fear in social situations and avoidance behaviour (Heimberg et al., Citation1999; Rapee & Heimberg, Citation1997), psychopathy is defined by a lack of fear and rule-transgressive, aggressive behaviour (Cleckley, Citation1941; Hare & Neumann, Citation2008; Lykken, Citation1957). The definitions seem to describe opposing emotional (i.e. high fear versus lack of fear) and behavioural (i.e. avoidance versus aggression) components. Negative correlations between self-reported social anxiety and psychopathic tendencies have indeed been found (Dapprich et al., Citation2021; Hofmann et al., Citation2009), although self-reported avoidance and aggressive behaviour may correlate positively (Dapprich et al., Citation2021). Another shared mechanism of social anxiety and psychopathy might be distortions in the evaluations of facial expressions.

Even though explicit evaluations, i.e. valence ratings, of smiles do not seem to differ as a function of social anxiety or psychopathy (Eisenbarth et al., Citation2008; Heuer et al., Citation2007), implicit evaluations, i.e. impulsive approach-avoidance tendencies, do differ (Dapprich et al., Citation2021; Heuer et al., Citation2007; Lange et al., Citation2008; Roelofs et al., Citation2010; von Borries et al., Citation2012). The Approach-Avoidance Task (AAT) is a frequently used task to assess implicit evaluations, building on the innate motivation to approach pleasure and avoid harm (Phaf et al., Citation2014). In this task, participants respond to pictures of facial expressions by either pulling them closer with a joystick (approach) or pushing them away (avoid). Healthy participants are generally quicker to approach smiling faces and to avoid angry ones (Phaf et al., Citation2014). However, socially anxious individuals quickly avoid both smiling and angry faces, suggesting that they implicitly evaluate social interactions, regardless of their valence, as aversive (e.g. Heuer et al., Citation2007). In contrast, individuals with higher psychopathic traits only slowly avoid angry faces, suggesting that they implicitly evaluate angry faces as less aversive (Dapprich et al., Citation2021; von Borries et al., Citation2012). Overgeneralised avoidance of both positive and negative facial expressions might underlie social avoidance, whereas a lack of avoidance of negative facial expressions might underlie aggressive behaviour (Heuer et al., Citation2007; von Borries et al., Citation2012). Yet, previous research did not consider that both positive and negative meanings can be conveyed through smiles.

Therefore, the current study examined whether perceivers’ levels of social anxiety and psychopathic traits are related to differences in the explicit and implicit evaluations of the reward, affiliation and dominance smile. Based on the theoretically positive meaning of both the reward smile (i.e. expressing happiness) and the affiliation smile (i.e. promoting social connectedness), we expected both to be evaluated positively, both explicitly and implicitly (i.e. approached quickly). In contrast, based on the theoretically negative meaning of the dominance smile (i.e. expressing dominance, which is reciprocally related to anger; Cabral et al., Citation2016), we expected the dominance smile to be evaluated negatively, both explicitly and implicitly (i.e. avoided quickly).

Based on the seemingly opposing correlates of social anxiety and psychopathy, we first tested whether self-reported social anxiety and psychopathic tendencies did indeed correlate negatively with each other. Explicit evaluations were not expected to differ as a function of social anxiety or psychopathic traits (Eisenbarth et al., Citation2008; Heuer et al., Citation2007), but implicit evaluations, operationalised as approach-avoidance tendencies, were expected to differ. Participants with higher social anxiety were expected to avoid all three smiles more quickly than individuals with lower social anxiety, in line with their overgeneralised avoidance of smiling and angry facial expressions (e.g. Heuer et al., Citation2007). Differences in the speed of these avoidance tendencies might indicate which smile they find most aversive. Participants with higher psychopathic traits were expected to avoid the dominance smile more slowly than individuals with lower psychopathic traits, in line with their reduced avoidance of angry facial expressions (Dapprich et al., Citation2021; von Borries et al., Citation2012). Weaker avoidance tendencies in response to dominance smiles might indicate in how far more subtle negative expressions, as compared to angry expressions, are perceived as provocative.

In order to test these hypotheses, self-report questionnaires on social anxiety and psychopathic traits, an explicit valence rating task, and an AAT were administered in female students. Only female students were tested since they might better recognise subtle facial expressions (Hoffmann et al., Citation2010). We operationalised psychopathic traits by means of two well-validated questionnaires to comprehensively capture its characterising attributes. That is, first, the Levenson Self-Report Psychopathy Scale was used to measure both the affective-interpersonal deficit (Factor I) and the antisocial lifestyle (Factor II; Levenson et al., Citation1995). Second, the Inventory of Callous–Unemotional Traits was used to measure callous–unemotional traits (Frick, Citation2004). In all analyses, we also controlled for gender of the expresser based on the stereotypes that females are more affiliative and males more dominant (Hess et al., Citation2005), which might lead to more positive evaluations and faster approach tendencies for expressions that conform to these stereotypes.

Methods

The current study combined different research interests. Both the whole study set-up (#13747) and the current research questions including the statistical approach (#30627) were pre-registered on aspredicted.org. In the following, only the measurements which are relevant for the current research question will be explained in detail.Footnote1

Participants

We recruited 123 female psychology students from the participant pool of Radboud University, Nijmegen, the Netherlands.Footnote2 Participants were between 17 and 48 years old (M[SD] = 20.37 [4.02]). One participant was excluded due to technical problems. The resulting final sample consisted of 122 females. Participation was rewarded with course credit.

Procedure

All participants first completed the Approach-Avoidance Task and a Motivated Viewing Task (the latter is unrelated to the current research questions since it did not include pictures of the three smiles). Then participants completed the Explicit Valence Rating Task and filled in the Inventory of Callous–Unemotional Traits, the Levenson Self-Report Psychopathy Scale, the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale and the State Self-Esteem Scale. Only the Approach-Avoidance Task and the Explicit Valence Rating Task contained pictures of the three different smiles, therefore only these two tasks are relevant for the current paper. Validated pictures of white actors expressing the three smiles were derived from Rychlowska et al. (Citation2017) and Martin et al. (Citation2021). Only full-intensity expressions of the three smiles were used. The whole experiment took one hour, after which participants were thanked and debriefed.

Explicit Valence Rating Task (EVRT)

In the EVRT, participants rated the valence of five different facial expressions: the affiliation smile, the reward smile, the dominance smile, an angry and a neutral expression. Eight different white actors (4 females and 4 males) displayed each of these expressions (Martin et al., Citation2021; Rychlowska et al., Citation2017), yielding a total of 40 trials. The instructions presented with each picture read: “Imagine someone would look at you like this. Do you think this expression is rather positive or rather negative?” Pictures were presented with 72 × 72 dpi resolution, and they remained on the screen until a response was given, using a rating scale ranging from −100 (negative) to +100 (positive) with 0 being neutral. Internal consistencies of the valence ratings ranged from poor (α = .36 for female affiliation smiles) to excellent (α = .91 for angry faces). See for the descriptive statistics.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of explicit valence ratings (N = 122).

Approach-Avoidance Task (AAT; Heuer et al., Citation2007)

An adapted version of the AAT was used including pictures of the three smiles, next to pictures of angry and neutral faces. Participants were seated in front of a computer screen with a joystick mounted on the table. Single pictures of the facial expressions were presented on the screen in medium size. Upon pulling versus pushing of the joystick, the picture grew or shrank in size, respectively. The picture disappeared when a full movement in the correct direction was made, and the latency of this full movement was automatically recorded. Participants had to respond to the colour of each picture (sepia or grey). Half of the participants had to pull all grey pictures and to push all sepia pictures. This was reversed for the other half. The 40 pictures that were also used in the EVRT were mixed with 80 filler pictures of other actors showing only neutral expressions. Each picture was pushed and pulled once, yielding a total of 240 trials. In the analyses, only the 80 trials of the 8 actors expressing the three smiles, angry and neutral expressions were used. The internal consistency of the reaction time (RT) differences in the whole AAT was poor (RT of pushing minus the corresponding RT of pulling; α = .25), and it was even lower for the different combinations of facial expressions and gender (see supplementary material for the descriptive statistics).

Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale (LSAS; Liebowitz, Citation1987)

The LSAS subscale measuring fear of social situations was used. For 24 social situations, participants rated their perceived level of anxiety (e.g. “talking to people in authority”). Answers were given on a Likert-scale ranging from 0 (none) to 3 (severe) and were summed up to the anxiety subscale score. Internal consistency was high (α = .90).

Inventory of Callous–Unemotional Traits (ICU; Frick, Citation2004)

The ICU measures callous–unemotional traits. It consists of 24 items (e.g. “I do not show my emotions to others”), which were rated on a Likert-scale ranging from 0 (not at all true) to 3 (definitely true). Internal consistency for the total score was acceptable (α = .70).

Levenson Self-Report Psychopathy Scale (LSRPS; Levenson et al., Citation1995)

The LSRPS measures psychopathic tendencies in non-clinical samples. It consists of 26 items measuring the affective-interpersonal deficit (i.e. Factor I; e.g. “Looking out for myself is my top priority”) and antisocial lifestyle (i.e. Factor II; e.g. “I find myself in the same kind of trouble time after time”). They are rated on a Likert-scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). Internal consistency of Factor II (α = .63) was questionable, but acceptable for Factor I (α = .72) and the total score (α = .77).

Statistical approach

Data were analysed using the statistical software s R (version 3.5.0; R Core Team, Citation2019) and R studio (version 1.2.5033; RStudio Team, Citation2019). Pearson’s correlations between questionnaires and valence ratings were calculated with the function corr.test of the package “psych” using Bonferroni adjustment to control for multiple testing (version 1.8.12; Revelle, Citation2018). Bayesian linear mixed models were conducted to analyse our main research questions by using the function brm of the package “brms” (version 2.11.1; Bürkner, Citation2017). The models are described in more detail in the supplementary materials. Model convergence was assessed in terms of Rhat (values > .9 and < 1.1 were considered as good) and diagnostic plots (Bürkner, Citation2017). Importantly, we considered an effect to be statistically significant, if the 95% posterior credible interval (CI) did not include zero. Significant interactions were followed up using the package “emmeans” (Lenth, Citation2020).

Transparency statement

Please note that the preregistration of the current study contains a slightly different terminology, less nuanced hypotheses, and a different analysis for the explicit valence ratings. First, in the pre-registration, we refer to the three smiles by using rather plain terms. Here, we decided to use the established terms in order to enhance the comparability of our and previous results. Second, we were able to specify our hypotheses regarding gender and explicit evaluations after reading more literature on social stereotypes. Finally, we realised that the explicit valence ratings can be analysed on the trial level, thereby controlling for participant and actor. Thus, we used mixed models for the analysis of the explicit valence ratings, too.

Results

Correlations between questionnaires

Descriptive statistics of our measures and a complete correlation matrix are depicted in the supplementary materials. We found significant positive correlations of the anxiety subscale of the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale with the Levenson Self-Report Psychopathy Scale total score (r = .30, p = .010) and with the Levenson Self-Report Psychopathy Scale Factor II scale (r = .34, p = .002): Participants with higher social anxiety had higher levels of psychopathic tendencies.

Explicit valence ratings

Explicit valence ratings were predicted as a function of the categorical predictors facial expression (reward smile/ affiliation smile/ dominance smile/ angry/ neutral) and actors’ gender (male/ female), which were sum-to-zero coded, as well as the continuous predictors social anxiety (i.e. Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale anxiety score) and psychopathic tendencies (i.e. Inventory of Callous–Unemotional Traits total score and Levenson Self-Report Psychopathy Scale total score), which were standardised. The four-way interactions between facial expression, gender, social anxiety and the measurements for psychopathic traits, respectively, as well as the underlying three- and two-way interactions were included. Random intercepts for participant and actor were included. Facial expression, gender, and their interaction were entered as random slopes varying across participants. Facial expression was included as random slope varying across actor. A more detailed description of the statistical model can be found in the supplementary materials.

As mentioned above, we expected a significant main effect of facial expression on valence ratings, indicating more positive evaluations of both the reward smile and the affiliation smile, and more negative evaluations of the dominance smile. Furthermore, we expected a significant interaction of facial expression and gender on valence ratings, indicating more positive evaluations of affiliation smiles expressed by females, and dominance smiles expressed by males. We did not expect that social anxiety or psychopathic tendencies would be related to any differences in the valence ratings.

The model converged without warnings and the diagnostic plots indicated that sampling succeeded. Most important for the current questions, the reward smile (estimated regression coefficient [B] = 60.62), lower and upper bounds of the 95% posterior credible interval (95% CI) [50.47, 70.57], the affiliation smile (B = 27.51, 95% CI [10.57, 44.79]) and the dominance smile (B = 17.13, 95% CI [2.16, 32.01]) were all rated as more positive than the overall mean, whereas angry expressions (B = −74.30, 95% CI [−84.93, −63.60]) were rated as more negative than the overall mean. Post-hoc analyses showed that reward smiles were rated more positively than affiliation smiles (B = −33.1, higher and lower posterior density interval (HPD) [−53.2, −12.7]), and also more positively than dominance smiles (B = −43.7, HPD [−62.3, −24.5]), whereas the difference between affiliation smiles and dominance smiles was not significant (B = 10.6, HPD [−14.5, 35.6]).

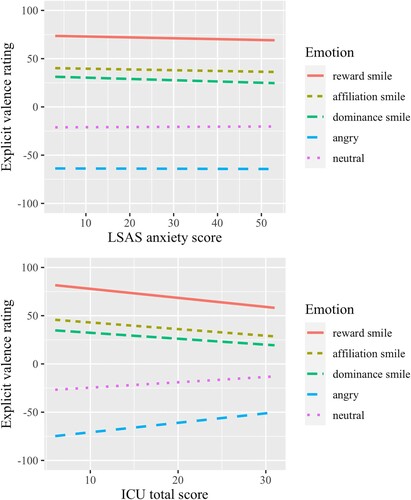

Furthermore, there were significant interactions between the Inventory of Callous–Unemotional traits total score and the ratings of the reward smile, the dominance smile and angry expressions. Thus, with increasing levels of callous–unemotional traits, the reward smile (B = −5.01, 95% CI [−8.25, −1.73]) and the dominance smile (B = −2.80, 95% CI [−5.43, −0.19]) were rated as less positive, whereas angry expressions were rated as less negative (B = 6.28, 95% CI [2.08, 10.35]). For an illustration, see .

Figure 1. Explicit valence ratings per facial expression as a function of social anxiety and callous-unemotional traits

Finally, there was a significant interaction between ratings of angry female faces and Levenson Self-Report Scale scores (B = 2.01, 95% CI [0.42, 3.63]), suggesting that higher psychopathic tendencies were related to less negative ratings of females’ angry expressions. However, neither the effect of gender nor the effect of social anxiety was significant, indicating that the explicit valence ratings did not differ between male and female actors, nor did they differ for participants with varying levels of social anxiety.

Approach-avoidance response times

Approach-avoidance tendencies (operationalised as reaction time differences in the Approach-Avoidance Task) were predicted as a function of the same model as for explicit valence ratings, though the categorical predictor movement (push/ pull) was added. That is, reaction times of correct trials that were performed with the pictures of the same actors as in the explicit valence rating were entered as the dependent variable. The categorical predictors facial expression (reward smile/ affiliation smile/ dominance smile/ angry/ neutral), movement (push/ pull) and actors’ gender (male/ female) were sum-to-zero coded, whereas the continuous predictors Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale, Inventory of Callous–Unemotional Traits and Levenson Self-Report Psychopathy Scale were standardised. Two five-way interactions were specified, namely for facial expression, movement, gender, social anxiety (i.e. Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale) and psychopathic tendencies (i.e. Inventory of Callous–Unemotional Traits and Levenson Self-Report Psychopathy Scale, respectively). In addition to that, the underlying four-, three- and two-way interactions were included. Random intercepts for participant and actor were entered. Facial expression, movement, gender and their interactions were specified as random slopes varying across participants. Facial expression and movement were included as random slopes varying across actor. A complete description of the statistical model can be found in the supplementary material.

As mentioned above, we expected a significant two-way interaction of facial expression and movement on reaction times, indicating shorter reaction times for the approach of both the reward and affiliation smile, as well as shorter reaction times for the avoidance of dominance smiles (and angry expressions). Furthermore, we expected significant three-way interactions between facial expression, movement and social anxiety, indicating shorter reaction times for the avoidance of all smiles, as well as significant three-way interactions between facial expression, movement and psychopathic tendencies, indicating shorter reaction times for the avoidance of dominance smiles (and angry expressions).

The model converged without warnings and the diagnostic plot indicated that sampling succeeded. There was a significant main effect of movement on reaction time, indicating that participants were generally faster to push than to pull the joystick (B = 0.03, 95% CI [0.02, 0.05]). Neither a significant interaction between facial expressions and movement, nor between facial expressions, movement and any other predictor of interest was found. Thus, social anxiety, CU-traits, psychopathic tendencies, and expresser gender were unrelated to the responses to facial expressions.

Discussion

The aim of the current study was to examine the explicit and implicit evaluations of three different types of smiles by also taking perceivers’ social anxiety and psychopathic traits into account. At an explicit level, all smile types were evaluated as more positive than neutral and angry expressions. Reward smiles were evaluated most positively. Affiliation smiles and dominance smiles were evaluated positively, too, but did not differ from each other in perceived positivity. With increasing levels of callous–unemotional (CU) traits, the reward smile and the dominance smile were evaluated less positively, and angry faces less negatively. Neither perceivers’ level of social anxiety nor expressers’ gender were related to the evaluations of the smiles. In implicit evaluations, none of the expected differences emerged.

The finding that all three smiles were explicitly evaluated as positive is partly in line with theory and research. First, reward smiles received the most positive evaluations, which is in line with both its theoretical meaning and previous findings. That is, its distinct morphological features, namely symmetric activations of the zygomaticus major and raised eye brows, have consistently been interpreted as spontaneous expressions of happiness, joy or contentment (Martin et al., Citation2021; Orlowska et al., Citation2018; Rychlowska et al., Citation2017). Moreover, they were found to buffer perceivers’ stress responses (Martin et al., Citation2018). The positive explicit valence ratings found in the current study further support its rewarding function to perceivers.

Second, the generally positive evaluations of dominance smiles were unexpected and in line neither with theory nor with previous findings. Previous research found that pictures and video clips of actors showing an asymmetric activation of the zygomaticus major, a wrinkled nose and a raised upper lip were clearly recognised as signals of social dominance, disapproval or contempt (Martin et al., Citation2021; Orlowska et al., Citation2018; Rychlowska et al., Citation2017). Moreover, they increased stress responses in perceivers (Martin et al., Citation2018), underlining a negative meaning for perceivers. In the current study, dominance smiles were less positively evaluated than reward smiles and received the least positive ratings of the three smile types, suggesting that participants perceived the dominance smile as the most negative smile – but still generally positive. If no context information is available, people might fall back on the prototypical assumption that smiles are rather positive. Yet, the circumstances under which the dominance smile has a negative or positive meaning require further investigation.

Finally, positive evaluations of the affiliation smile are in line with its theoretical meaning, though only partly in line with previous research. Expressions of the affiliation smile, i.e. symmetric activations of the zygomaticus major and a lowered upper lip, were less easily interpreted as intending to improve social relationships (Orlowska et al., Citation2018; Rychlowska et al., Citation2017), and rather labelled as faked (Martin et al., Citation2021). A positive, prosocial function of affiliation smiles could only be detected when taking context and perceiver characteristics into account (Martin et al., Citation2018; Rychlowska et al., Citation2021). The current results also suggest that participants perceived stand-alone affiliation smiles neither as clearly positive, nor as clearly negative: Their explicit valence ratings were lower than those of reward smiles, but could not be distinguished from those of dominance smiles. Similarly, the range of explicit evaluations ascribed to the affiliation smiles (range = −7 – 75), as well as the low Cronbach’s alpha values (α = .67) suggest that the meaning of the affiliation smile may be ambiguous, varying across specific stimuli and perceivers. However, different to previous research (Martin et al., Citation2018), we did not find that perceiver characteristics related to different responses towards affiliation smiles, but to different responses towards both reward and dominance smiles.

Our findings with respect to individual differences in the explicit evaluations of the three smiles were only partially consistent with our predictions. In contrast to our predictions, increasing levels of CU-traits were associated with decreased intensity ratings of reward smiles, dominance smiles and angry expressions (decreased positivity in the case of smiles, and decreased negativity in the case of anger). Previous research showed that these expressions were more easily recognised than other expressions (e.g. Montagne et al., Citation2007; Rychlowska et al., Citation2017). Perhaps an easier recognition also enabled participants with higher CU-traits to be less affected by the valence of the respective expression. Since CU-traits are characterised by unemotionality, carelessness and uncaringness (Frick, Citation2004), the diminished ability to experience affect might be related to diminished ratings of another person’s affect. Similarly, male participants with higher CU-traits evaluated positive video clips as less positive and negative clips as less negative (Fanti et al., Citation2016). This flattened sensitivity could also explain why CU-traits are associated with aggressive, rule-breaking behaviour. Consistent with our predictions, social anxiety was not found to be associated with explicit evaluations of either smiles or angry expressions. This finding has been explained by the notion that biased implicit processes rather than biased explicit evaluations maintain the strong behavioural avoidance tendencies observed in individuals with social anxiety (Heuer et al., Citation2007). However, the current attempt to study implicit evaluations of the three smiles was unfortunately inconsistent with our predictions.

Unexpectedly, implicit evaluations of the smile types did not differ from each other, and neither social anxiety nor psychopathy played a role in this hypothesised link. The Approach-Avoidance Task (AAT) has often been used to measure implicit evaluations (for a meta-analysis, see Phaf et al., Citation2014) and biased automatic action tendencies in response to facial expressions have been replicated for both social anxiety (Heuer et al., Citation2007; Lange et al., Citation2008; Roelofs et al., Citation2010) and psychopathic traits (Dapprich et al., Citation2021; von Borries et al., Citation2012). However, in the current study, AAT response tendencies had very low reliabilities for the whole task and for the different facial expressions. It might be that we had too few actors with too much variability for the same facial expressions, which did not consistently evoke the same tendency to approach or avoid. As the responses to our stimuli were not internally consistent, a larger variety of actors and more validation studies of the three smiles are needed. Not only automatic action tendencies showed an unexpected pattern, but also the link between self-reported social anxiety and psychopathic tendencies disconfirmed our hypotheses.

Against our expectations and some previous research (Dapprich et al., Citation2021; Hofmann et al., Citation2009), social anxiety and psychopathic tendencies correlated significantly positively with each other. We found that participants who reported more fear in social situations also reported more psychopathic tendencies, such as shallow affect, lacking prosocial emotions and impulsive behaviour. However, to be more precise, social anxiety was only significantly positively associated with the total score and with Factor II of the Levenson Self-Report Psychopathy Scale, but not with Factor I or CU-traits. These findings might indicate that different subtypes of (social) anxiety and psychopathy are differentially linked to each other (for a review, see Derefinko, Citation2015). Indeed, Dapprich et al. (Citation2021) as well as Hofmann et al. (Citation2009) used other questionnaires than we did here. Thus, it will be necessary to test whether different operationalisation of social anxiety and psychopathy relate differently to each other and to other concepts.

Several limitations should be considered when interpreting the present results. First, the current study used static pictures of facial expressions, which lack context information and have lower ecological validity. Previous research already stressed the importance of using a multimethod approach in order to study the three smiles, as well as their social motives and their effects on perceivers (Martin et al., Citation2018, Citation2021; Orlowska et al., Citation2018; Rychlowska et al., Citation2021). For instance, a variety of different measures has been used, including physiological measures, economic decisions, facial mimicry and explicit rating tasks. These studies revealed that realistic presentations of the smiles and context information are crucial. Thus, examining valence ratings with paradigms of higher ecological validity would be desirable. Furthermore, given the partly low internal consistencies of our measures, future research needs to include additional stimuli. Finally, as we only tested healthy female participants, the effects cannot be generalised to males or clinical populations. Future research should examine whether the same effects occur in other samples.

The current study was one of the first to examine the evaluation of three theoretically central types of smiles in relation to two psychopathologies that interfere with social behaviour – social anxiety and psychopathy. The present results suggest that all smiles are evaluated as positive. However, further validation of the three smiles using multimethod approaches seems desirable. A more comprehensive understanding of the influence of perceivers’ characteristics on the interpretation of the meaning of facial expressions may inform us about the possible behavioural consequences of such expressions.

Supplementary_Material

Download MS Word (36.2 KB)Acknowledgements

We would like to thank our students for helping to conduct the experiment, as well as our participants for participating in it. Finally, the helpful suggestions by the editor and two anonymous reviewers are gratefully acknowledged.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 In addition to the measures mentioned here, a Motivated Viewing Task which did not include pictures of the three smiles, and the State Self-Esteem Questionnaire (Heatherton & Polivy, Citation1991) were administered.

2 Based on an a-priori power analysis, we aimed to test 120 participants. We powered for a small-to-medium correlation between an interindividual difference variable (e.g. social anxiety) and AAT difference scores (r=.25, two-tailed), with p=.05 and 1−ß=.80.

References

- Bürkner, P. (2017). Brms: An R package for Bayesian multilevel models using Stan. Journal of Statistical Software, 80(1), 1–28. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v080.i01

- Cabral, J. C. C., Tavares, P. d. S., & de Almeida, R. M. M. (2016). Reciprocal effects between dominance and anger: A systematic review. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 71, 761–771. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.10.021

- Cleckley, H. M. (1941). The mask of sanity: An attempt to reinterpret the so-called psychopathic personality. Mosby.

- Dapprich, A. L., Lange, W.-G., von Borries, A. K. L., Volman, I., Figner, B., & Roelofs, K. (2021). The role of psychopathic traits, social anxiety and cortisol in social approach avoidance tendencies. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 128, 105207. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2021.105207

- Derefinko, K. J. (2015). Psychopathy and low anxiety: Meta-analytic evidence for the absence of inhibition, not affect. Journal of Personality, 83(6), 693–709. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12124

- Eisenbarth, H., Alpers, G. W., Segrè, D., Calogero, A., & Angrilli, A. (2008). Categorization and evaluation of emotional faces in psychopathic women. Psychiatry Research, 159(1–2), 189–195. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2007.09.001

- Fanti, K. A., Panayiotou, G., Lombardo, M. V., & Kyranides, M. N. (2016). Unemotional on all counts: Evidence of reduced affective responses in individuals with high callous-unemotional traits across emotion systems and valences. Social Neuroscience, 11(1), 72–87. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/17470919.2015.1034378

- Frick, P. J. (2004). Inventory of Callous-Unemotional Traits.

- Hare, R. D., & Neumann, C. S. (2008). Psychopathy as a clinical and empirical construct. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 4(1), 217–246. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091452

- Heatherton, T. F., & Polivy, J.. (1991). Development and validation of a scale for measuring state self-esteem. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 60(6), 895–910. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.60.6.895

- Heimberg, R. G., Horner, K. J., Juster, H. R., Safren, S. A., Brown, E. J., Schneier, F. R., & Liebowitz, M. R. (1999). Psychometric properties of the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale. Psychological Medicine, 29(1), 199–212. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291798007879

- Hess, U., Adams, R. B. J., & Kleck, R. E. (2005). Who may frown and who should smile? Dominance, affiliation, and the display of happiness and anger. Cognition & Emotion, 19(4), 515–536. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02699930441000364

- Heuer, K., Rinck, M., & Becker, E. S. (2007). Avoidance of emotional facial expressions in social anxiety: The approach-avoidance task. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 45(12), 2990–3001. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2007.08.010

- Hoffmann, H., Kessler, H., Eppel, T., Rukavina, S., & Traue, H. C. (2010). Expression intensity, gender and facial emotion recognition: Women recognize only subtle facial emotions better than men. Acta Psychologica, 135(3), 278–283. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actpsy.2010.07.012

- Hofmann, S. G., Korte, K. J., & Suvak, M. K. (2009). The upside of being socially anxious: Psychopathic attributes and social anxiety are negatively associated. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 28(6), 714–727. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2009.28.6.714

- Keltner, D., & Haidt, J. (1999). Social functions of emotions at four levels of analysis. Cognition & Emotion, 13(5), 505–521. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/026999399379168

- Lange, W.-G., Keijsers, G., Becker, E. S., & Rinck, M. (2008). Social anxiety and evaluation of social crowds: Explicit and implicit measures. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 46(8), 932–943. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2008.04.008

- Lenth, R. (2020). emmeans: Estimated Marginal Means, aka Least-Squares Means (R package version 1.4.6). https://cran.r-project.org/package=emmeans

- Levenson, M. R., Kiehl, K. A., & Fitzpatrick, C. M. (1995). Assessing psychopathic attributes in a noninstitutionalized population. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 68(1), 151–158. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.68.1.151

- Liebowitz, M. R. (1987). Social phobia. Modern Problems in Pharmacopsychiatry, 22, 141–173. doi:https://doi.org/10.1159/000414022

- Lischke, A., Lemke, D., Neubert, J., Hamm, A. O., & Lotze, M. (2017). Inter-individual differences in heart rate variability are associated with inter-individual differences in mind-reading. Scientific Reports, 7(1), 11557. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-11290-1

- Lykken, D. T. (1957). A study of anxiety in the sociopathic personality. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 55(1), 6–10. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/h0047232

- Martin, J. D., Abercrombie, H. C., Gilboa-Schechtman, E., & Niedenthal, P. M. (2018). Functionally distinct smiles elicit different physiological responses in an evaluative context. Scientific Reports, 8(3558), 1–8. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-21536-1

- Martin, J. D., Rychlowska, M., Wood, A., & Niedenthal, P. M. (2017). Smiles as multipurpose social signals. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 21(11), 864–877. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2017.08.007

- Martin, J. D., Wood, A., Cox, W. T. L., Sievert, S., Nowak, R., Gilboa-Schechtman, E., Zhao, F., Witkower, Z., Langbehn, A. T., & Niedenthal, P. M. (2021). Evidence for distinct facial signals of reward, affiliation, and dominance from both perception and production tasks. Affective Science, 2(1), 14–30. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s42761-020-00024-8

- Montagne, B., Kessels, R. P. C., De Haan, E. H. F., & Perrett, D. I. (2007). The emotion recognition task: A paradigm to measure the perception of facial emotional expressions at different intensities. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 104(2), 589–598. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2466/pms.104.2.589-598

- Niedenthal, P. M., Mermillod, M., Maringer, M., & Hess, U. (2010). The simulation of smiles (SIMS) model: Embodied simulation and the meaning of facial expression. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 33(6), 417–433. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X10000865

- Orlowska, A. B., Krumhuber, E. G., Rychlowska, M., & Szarota, P. (2018). Dynamics matter: Recognition of reward, affiliative, and dominance smiles from dynamic vs. static displays. Frontiers in Psychology, 9(938), 1–8. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00938

- Phaf, R. H., Mohr, S. E., Rotteveel, M., & Wicherts, J. M. (2014). Approach, avoidance, and affect: A meta-analysis of approach-avoidance tendencies in manual reaction time tasks. Frontiers in Psychology, 5(Article 378), 1–16. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00378

- Quintana, D. S., Guastella, A. J., Outhred, T., Hickie, I. B., & Kemp, A. H. (2012). Heart rate variability is associated with emotion recognition: Direct evidence for a relationship between the autonomic nervous system and social cognition. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 86(2), 168–172. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2012.08.012

- Rapee, R. M., & Heimberg, R. G. (1997). A cognitive-behavioral model of anxiety in social phobia. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 35(8), 741–756. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7967(97)00022-3

- R Core Team. (2019). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Organisation for Statistical Computing. https://www.r-project.org/

- Revelle, W. (2018). psych: Procedures for personality and psychological research (R package version 1.8.12). Northwestern University. https://cran.r-project.org/package=psych

- Roelofs, K., Putman, P., Schouten, S., Lange, W. G., Volman, I., & Rinck, M. (2010). Gaze direction differentially affects avoidance tendencies to happy and angry faces in socially anxious individuals. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 48(4), 290–294. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2009.11.008

- RStudio Team. (2019). RStudio: Integrated development environment for R.

- Rychlowska, M., Jack, R. E., Garrod, O. G. B., Schyns, P. G., Martin, J. D., & Niedenthal, P. M. (2017). Functional smiles: Tools for love, sympathy, and war. Psychological Science, 28(9), 1259–1270. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797617706082

- Rychlowska, M., van der Schalk, J., Niedenthal, P., Martin, J., Carpenter, S. M., & Manstead, A. S. R. (2021). Dominance, reward, and affiliation smiles modulate the meaning of uncooperative or untrustworthy behaviour. Cognition and Emotion, 35(7), 1281–1301. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2021.1948391

- von Borries, A. K. L., Volman, I., de Bruijn, E. R. A., Bulten, B. H., Verkes, R. J., & Roelofs, K. (2012). Psychopaths lack the automatic avoidance of social threat: Relation to instrumental aggression. Psychiatry Research, 200(2–3), 761–766. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2012.06.026