ABSTRACT

Emotional experiences typically labelled “being moved” or “feeling touched” may belong to one universal emotion. This emotion, which has been labelled “kama muta”, is hypothesised to have a positive valence, be elicited by sudden intensifications of social closeness, and be accompanied by warmth, goosebumps and tears. Initial evidence on correlations among the kama muta components has been collected with self-reports after or during the emotion. Continuous measures during the emotion seem particularly informative, but previous work allows only restricted inferences on intra-individual processes because time series were cross-correlated across samples. In the current studies, we instead use a within-subject design to replicate and extend prior work. We compute intra-individual cross-correlations between continuous self-reports on feeling moved and (1) positive and negative affect; (2) goosebumps and subjective warmth and (3) appraisals of closeness and morality. Results confirm the predictions of kama muta theory that feeling moved by intensified communal sharing cross-correlates with appraised closeness, positive affect, warmth and (less so) goosebumps, but not with negative affect. Contrary to predictions, appraised morality cross-correlated with feeling moved as much as appraised closeness did. We conclude that strong inferences on emotional processes are possible using continuous measures, replace earlier findings, and are largely in line with theorising.

Many people can think of remarkable pleasant feelings associated with social bonding. We can get feelings that we describe with terms like “heart-warming”, “tenderness”, “being moved”, or “touching” when sharing special moments with special people, such as when we see a loved one that has been away for a little too long; sing, pray or mourn together, or win a game together as a team. Similar feelings can arise from witnessing bonding between third parties, for example when someone cares for and helps a stranger or reunites with a loved one. There are many terms for such feelings – lay and scientific – but scholars disagree on their exact nature.

Various theorised affective states associated with social closeness and bonding have been studied for more than a century (for a review, see Zickfeld, Schubert, Seibt, & Fiske, Citation2019). More recently, several theoretical accounts of the experience of being moved (or feeling moved)Footnote1 have been proposed (e.g. Cova & Deonna, Citation2014; Cullhed, Citation2020; Deonna, Citation2020; Menninghaus et al., Citation2015; Sparks et al., Citation2019). One theory developed to understand this experience is kama muta theory (Fiske, Schubert, et al., Citation2017). It postulates a theoretical emotion labelled “kama muta”. Kama muta is, according to the theory, a distinct positive emotion elicited by the appraisal of a sudden intensification of a communal sharing relationship. Most, but not all, instances of being moved and similarly labelled feelings such as nostalgia are assumed to be instances of kama muta (Fiske, Schubert, et al., Citation2017). The term “kama muta” (Sanskrit for “moved by love”) is used to accurately refer to an emotion theorised to occur across many, but not all, events described with lay terms like moving, heart-warming, nostalgic or cute. This approach is similar to previous theories that introduced distinct theorised affective concepts, such as cognitive dissonance theory (Festinger, Citation1957) or elevation theory (Haidt, Citation2000, Citation2003).

Hypotheses derived from the kama muta theory can be tested in cross-sectional correlational studies that measure aspects of the experience after it has concluded (e.g. Zickfeld, Schubert, Seibt, Blomster, et al., Citation2019). Alternatively, they can be tested in experiments that measure the experience while it is unfolding in real time (Schubert et al., Citation2018; Vuoskoski et al., Citation2022). In the current work, we follow the second and more rare approach. We test hypotheses regarding appraisals, physiological symptoms and valence involved in kama muta with an updated approach to continuous measurement concurrently to the experience.

Kama muta

Kama muta is hypothesised to follow from sudden intensifications of communal sharing. The concept of communal sharing comes from relational models theory, according to which relationships can be described by four types or dimensions: market pricing, in which actions and resources are exchanged for others of proportional value; equality matching, in which the parties are concerned about using identical procedures to create equality; authority ranking, the relationships between superiors and their subordinates and communal sharing, in which the parties are treated as one, caring and sharing according to need and ability (Fiske, Citation1992, Citation2004). The theory holds that kama muta is elicited when a perceived communal sharing relationship becomes salient or comes into existence over a short time, and thus suddenly intensifies. This can for instance happen when someone (yourself or someone you see) hugs a loved one or when someone shows kindness to a stranger (Fiske, Schubert, et al., Citation2017).

Kama muta is theorised to be universal, functional and to have evolved through natural selection. According to the theory, kama muta is not just elicited by experiencing intensifications of communal sharing but also in turn motivating people to maintain and invest in communal sharing relationships (Fiske, Seibt, et al., Citation2019). This makes kama muta into a communal glue. Cultural practices that emphasise shared essences – dressing similarly, sharing resources or partaking in rituals that, literally or figuratively, connect bodies – contribute to communal sharing and, in turn, increase the chances of feeling kama muta (Fiske, Citation2004). The emotion is positive in the sense that people enjoy it and want to share and propagate it. This makes the social practices that elicit kama muta attractive to members of the group. Since communal cooperation is so central to survival and reproduction for humans, natural selection would plausibly favour an emotion like kama muta.

While maintaining that kama muta is universal, the theory also emphasises that its expression and interpretation vary greatly between cultures, groups, people and contexts (Fiske, Seibt, et al., Citation2019). Weak instances of kama muta are expected to be frequent in daily life and contribute to making social encounters pleasant and desirable. Stronger kama muta may be felt when sharing an important memory or hugging a loved one after a long time apart; in such instances, it may be labelled “nostalgia” or “love”.

Empirical evidence for kama muta theory consists of findings that there is an emotional response that is distinct from joy, sadness and awe (i.e. all emotions that have a phenomenology somewhat similar to that of kama muta) in terms of appraisals, sensations, labels, non-verbal expressions and behavioural tendencies (Seibt et al., Citation2018; Zickfeld, Schubert, Seibt, Blomster, et al., Citation2019). Furthermore, continuous measures of self-rated level of feeling moved differ from those of self-rated levels of happiness and sadness (Schubert et al., Citation2018). Sensations and bodily responses include feeling warm; moist eyes or tears; chills and goosebumps; a lump in the throat and feeling buoyant afterward (Fiske, Schubert, et al., Citation2017). While these in isolation can be symptoms of many emotions, the co-occurrence of some or all of them is particularly characteristic of kama muta. Kama muta also seems distinct from similar emotions in terms of appraisals and motivational tendencies – kama muta is associated with higher ratings on items pertaining to appraisals of love and bonding as well as items pertaining to the desire to hug, show appreciation for and help others (Zickfeld, Schubert, Seibt, Blomster, et al., Citation2019).

Continuous measurement of kama muta and its pitfalls

Kama muta theory defines the theoretical concept kama muta instead of being moved (or feeling moved) as its main phenomenon. However, being moved (and similar vernacular labels, e.g. being touched) still plays an important part in the theory, namely as a culture’s label for this emotion that can be used as operationalisation. To test how the subjective experience of feeling moved coincides with other experiential variables, Schubert et al. (Citation2018) assessed the coherence between various variables that were assessed continuously (see also Mauss et al., Citation2005). In the study, participants saw one out of six different viral video clips typically described as “moving”. While they saw the video clip, they had to continuously rate their own experience on one item only. Participants watched one or several of these video clips, but always rated the same item. These were feeling moved, happiness, sadness, experiencing goosebumps, bodily warmth or crying and perceiving closeness. (The study was conducted in English with native English speakers.) Time series of each variable and for each video were created by taking the average of the participants’ ratings for consecutive 3-second intervals. Each of the time series thus showed how each variable developed throughout each video averaged across participants. To measure the co-occurrence between feeling moved and the other variables, cross-correlations were computed between the time series of being moved and each of the other time series (after detrending the time series). From the results, the authors inferred that feeling moved coincides with appraisals of closeness, a sense of warmth in the chest, goosebumps and tears and that it often coincides with feelings labelled as happiness but typically not with those labelled as sadness.

Because of the way Schubert et al. (Citation2018) collected data, it allows the conclusion that one sample’s average development of feeling moved correlated with another sample’s average development of, for instance, a sense of warmth in the chest. However, this approach also has its downsides. One limitation is that they drew conclusions about processes at the individual level from correlations at the group level. This is problematic because correlations within subgroups of data do not need to match the correlations in the data across subgroups. This problem, known as Simpson’s paradox (Blyth, Citation1972), is common in psychological research – when interpreting correlations between two variables in a sample, researchers are typically quick to infer that the two variables correlate similarly within persons.

To illustrate how Simpson’s paradox can lead to invalid inferences, consider (the widely used example of) how typing speed is related to typing accuracy. When measured once for everyone in a sample, speed and accuracy correlate positively because skilled typists are both fast and accurate. However, if one studied the performance of individual typists when typing at different speeds, the two variables would correlate negatively in the form of a speed-accuracy trade-off: The less fast people type, the more accurate they are, and this is true for typists at any level. The same can, in principle, happen for any correlation between two constructs (Fisher et al., Citation2018, p. 20). Correlations between variables within participants do not need to match the correlations found when measuring across all participants (Borsboom et al., Citation2003; Hamaker, Citation2012). Fisher et al. (Citation2018) have shown that this can be more than a theoretical problem by reanalysing data from multiple clinical studies, showing that intra-individual and inter-individual correlations can differ substantially in real data.

This problem afflicts the conclusion drawn by Schubert et al. (Citation2018). That one sample’s average emotional reaction to a video in one facet of kama muta occurs at the same time point as another sample’s average emotional reaction in a different facet is in line with the kama muta theory, but it does not automatically mean that the two facets also co-occur within most, many or even any individuals. The between-subject design of that study prevented any other type of analysis and thus inference.

To overcome this problem, in the current work, we gave up the between-subject design, and always assessed three continuous measures of emotional responses to the same video for every participant in three viewings. We calculated cross-correlations at the individual level first, before aggregating them across participants. In sum, while Schubert et al. (Citation2018) cross-correlated time series of averaged emotional responses across samples, we here average intra-individual cross-correlations of time series. This allows stronger inferences on intra-individual processes.

Overview of the current studies

The three studies we present in this paper had two main purposes. First, we tested whether selected results from Schubert et al. (Citation2018) would replicate with a changed methodology and analysis strategy. This was motivated by our realisation explained above: that Schubert et al. (Citation2018) made the error of drawing inferences about intra-individual processes from correlations measured between groups, as explained above. Second, in our studies, we also extended on Schubert et al. (Citation2018) by testing hypotheses derived from the kama muta theory against some opposing hypotheses found in the literature on being moved.

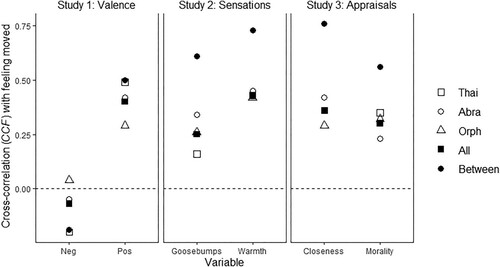

The three studies tested hypotheses on dominant affect, appraisal and physical sensations, respectively. In Study 1, we tested if feeling moved was more strongly correlated with positive affect than with negative affect, as predicted by the kama muta theory, but contested by findings and theorising by Menninghaus et al. (Citation2015, Citation2017). In Study 2, we tested whether Schubert et al. (Citation2018) findings about the correlations between feeling moved, experienced warmth and goosebumps, including the finding that warmth was more strongly correlated with feeling moved than goosebumps would replicate with our improved design. In Study 3, we tested if feeling moved was more strongly correlated with appraisals of social closeness (our approximation of communal sharing) than with appraisals of morality, a prediction that can be derived from the kama muta theory, but is contested by other literature – in particular, the literature on the elevation construct. summarizes the video-dependent and average cross-correlations between the variables in the three studies.

Table 1 . Cross-correlations between time series in each study depending on and across videos.

The three studies were preregistered. They were registered as one study but conducted consecutively, meaning that participants were not randomly assigned to one of the studies. Because of this, and to ease presentation, we present them here as three separate studies. The preregistrations, as well as the data, are openly available in the Open Science Framework at http://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/DE32V.

Study 1: feeling moved, positive affect and negative affect

The first study looked at the occurrence of positive and negative affect in instances of being moved. Although kama muta theory as well as other accounts of being moved describe the experience as positive, being moved has a close connection to negative feelings – many events that we see as moving occur in temporal or other vicinity to sadness or fear (e.g. mourning together over the loss of a loved one or giving one’s life to save another’s), and common symptoms of being moved, such as tears, chills, goosebumps and a lump in the throat overlap with those of sadness and fear (Zickfeld, Schubert, Seibt, Blomster, et al., Citation2019). Different theoretical accounts of being moved offer at least two general solutions to this problem. Some describe being moved as a mixture or synthesis of positive and negative affect – as joy or sadness but with opposite or ambiguous valences or as mixed positive and negative affect (Frijda, Citation2001; Menninghaus et al., Citation2015, Citation2017). Others, such as the kama muta theory, describe being moved as a single positive emotion, but one that due to the nature of the eliciting conditions often occurs alongside or shortly after occurrences of negative affect (Cova & Deonna, Citation2014; Fiske, Citation2019, pp. 92–94; Strick & van Soolingen, Citation2018).

Specifically, Fiske (Citation2019, pp. 92–94) has argued that kama muta often occurs together with negative affect because sudden intensifications of communal sharing (i.e. the appraisal of kama muta) often naturally appear during or after tragedy because they contrast from them. Death, natural disasters, attacks by an enemy, separation and other devastating events bring people together to mourn and support each other. But tragedy and negative affect is not theorised to be necessary for the experience of kama muta, and many events that have been identified as kama muta or being moved in empirical research and theorising seem purely positive (Cova & Deonna, Citation2014; Schubert et al., Citation2018; Steinnes et al., Citation2019; Zickfeld, Schubert, Seibt, Blomster, et al., Citation2019).

Another recent and prominent account of being moved construes it as an experience that inherently involves mixed positive and negative affect. Menninghaus et al. (Citation2015) asked participants to recall and describe an event that was moving, stirring or touching (using German translations of these terms) and afterward to report which emotions they had experienced during the event. Both when using a closed and when using an open-ended answering format, they found that joy and sadness were the two emotions most often reported. They asked another sample to rate the states moved, touched, stirred and deeply moved as well as other emotion terms, including joy and sadness, using semantic differential scales with adjective pairs such as “warm-cold” and “bright-dark” and found that the average ratings for being moved (and the synonyms) tended to fall around the middle between the average ratings for joy and sadness. They concluded that being moved is a state in which positive and negative emotions, typically joy and sadness, occur simultaneously or in rapid succession of each other and that being moved comes in joyfully moving and sadly moving prototypes depending on which emotion is more dominant (Menninghaus et al., Citation2015, Citation2017). Thus, the kama muta theory differs from the mixed-emotions account in that it does not predict that being moved needs to involve any sadness or any other negative emotion.

Schubert et al.’s (Citation2018) results showed that across six videos, the averaged samples’ time series of feelings moved cross-correlated with happiness more than with sadness. The cross-correlation with happiness was moderately positive. The cross-correlation with sadness was basically zero on average but spanned almost the entire spectrum from highly negative to highly positive across the stimuli. In this study, we tested the hypothesis that feeling moved is a positive emotion, as kama muta theory maintains, by measuring subjective levels of feeling moved, positive feelings and negative feelings while participants watched both joyful and sad videos that were considered very moving. We predicted that, across the videos, feeling moved would co-occur with a positive affect on average as well as more than it would co-occur with negative affect.

Method

Participants

Participants were recruited through Prolific (prolific.co). To allow us to observe some of the inter-individual variability in the variables that we measured and to achieve high statistical power, we aimed to recruit 120 participants (40 per video). We used a strategy in which we initially recruited until we reached the target number of participants, excluded participants based on preregistered criteria, and repeated these two steps until we had at least 120 participants. In total, we recruited 149 participants; 6 were excluded for failing an attention check embedded in the study (“Answer ‘somewhat like me’ to this question”), 1 due to technical issues, and 15 because they had cross-correlations between time series that were undefined or implausibly high (due to anomalous rating patterns). The final sample consisted of 127 participants (49 female, 77 male, 1 other; age range: 18–72, median age: 32). Participants were required to be native English speakers, residents of the USA and over 18 years old. They were compensated with USD 3.25, in accordance with Prolific’s standards for ethical compensation.

Materials and procedure

We selected three out of the six videos used by Schubert et al. (Citation2018; links to the videos in Supplementary Material). In “Thai Medicine”, a doctor covers the medical expenses of his patient upon realising that the same patient showed him mercy as a child when he tried to steal from the patient’s restaurant in order to help his sick mother. “Marina Abramovic” shows the surprise reunion between a performance artist and her former romantic and professional partner, and includes surprise, tender touching, tears and ends with him leaving again. “Two Orphans” is about two orphans who go on a journey to visit and mourn over the grave of one of their mothers. (The labels used for the videos here are from Schubert et al., Citation2018.) The videos were selected to have a stimulus sample that represents at least some of the theoretically relevant variation that exists in the universe of moving videos. “Thai medicine” represents the story where the climax is a very moving happy ending. “Two Orphans” represents a sad story that is nonetheless very moving. Finally, “Marina Abramovic” represents something in-between and, in addition, does not overtly touch on moral norms.

The videos were embedded in a form created in Qualtrics (Qualtrics.com). Each participant was randomly assigned to one video which they watched three times in a row. There was a rating scale underneath the video. The participants were instructed to immediately update their rating on the scale whenever their reaction to the video changed. For each time the participants watched the video, they were asked to rate a different item. The three items were: feeling moved (“Please rate to what extent you are feeling moved or touched right now”), positive affect (“Please rate to what extent you are having positive feelings right now”), and negative affect (“Please rate to what extent you are having negative feelings right now”). The order in which the three items were presented was randomised. The participants could choose whether to use their mouse, number keys on their keyboard or arrow keys to change their rating on the scale. Whenever the participants changed their rating, the rating, along with a timestamp and a randomly generated participant ID number, were saved and used to create time series of each participant’s second-to-second rating on the item throughout the video. In addition to the video section, the Qualtrics-form included a questionnaire with questions about demographics and subscales from the Perth Emotional Reactivity Scale (Becerra et al., Citation2019), the Perth Alexithymia Questionnaire (Preece et al., Citation2018) and the Affect Integration Inventory (2017).Footnote2 It was randomised whether the participants were presented with the questionnaire first or the video task first.

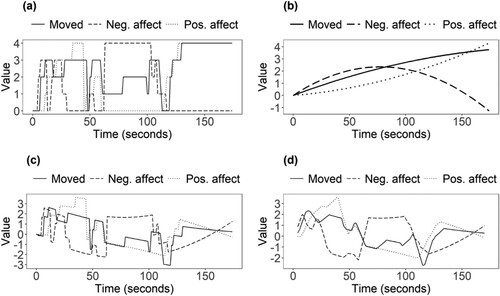

Statistical approach

In this study (and the following two), we looked at the co-occurrence between feeling moved and other variables by calculating the cross-correlations between the respective time series. As explained in Schubert et al. (Citation2018), simply taking the time series of the three variables as they are and measuring the cross-correlations between them would give an inflated estimate. (More details on this problem and our solution can be found in the supplementary material.) Therefore, we followed Schubert et al. (Citation2018) and detrended the time series before calculating cross-correlations. We detrended each time series for each participant separately by first regressing them individually on time in seconds (linear effect) and its square (quadratic effect), without an intercept and saving the residuals (see supplementary materials for more details). After detrending, we smoothened the time series with a 9-second moving average, assuming that participants never precisely react in the moment they experience a change. The decision to use 9 seconds was made after testing how different degrees of smoothing affected the time series of the pilot participants. (Note that this is different from binning into 9 seconds chunks.) illustrates the data preparation.

Figure 1. The data preparation process illustrated with the time series of one participant.

Note: The participant in this example watched the video labelled “Thai Medicine” and rated feeling moved, positive feelings and negative feelings on scales from 1 to 5. Panel (a) shows the time series only subtracted by 1. Panel (b) shows the individually derived linear and quadratic trends for each variable (no intercept included). Panel (c) shows the detrended time series, where the trends shown in panel (b) have been subtracted from the time series in panel (a). Panel (d) shows the detrended time series after smoothing with a moving average of 9 seconds. Note that the moving average function by default, when using a length of 9 seconds, removes the first four and last four seconds from the time series. The cross-correlation function (CCF) between the detrended and smoothed time series for this participant was 0.72 (moved – positive affect), −0.17 (moved – negative affect) and −0.45 (positive affect and negative affect).

With the detrended and smoothed individual time series, we computed the two intra-individual Pearson-based cross-correlation functions (CCF) without any lag between each participant’s time series of feeling moved and their time series of positive affect and negative affect, respectively. Next, we transformed the CCFs into Fisher z-coefficients. These were the units of analysis in our inferential tests. We excluded Fisher z-coefficients greater than 2.3 or smaller than −2.3 (corresponding to Pearson’s rs of ±.95), reasoning that it would be nearly impossible for two-time series to coincide to that extent if the participants had truly been rating their reactions continuously throughout the video.Footnote3 We also excluded 21 participants that had undefined CCFs resulting from never indicating a single change throughout the video.Footnote4 After excluding participants, we computed the means and standard deviations for each of the Fisher z-transformed CCFs and converted the mean back into CCF for reporting (treating them as regular Pearson’s rs). Supplementary Table 1 shows the means, standard deviations and maximal values of the ratings before applying the calculations just described.

To test whether our hypothesis that feeling moved would cross-correlate more with positive affect than with negative affect, we computed a general linear model where the individual Fisher z-coefficients were the dependent variable (see Otten & Wentura, Citation2001 for a similar procedure). We compared the z-coefficients for the two cross-correlation coefficients within participants, while also adding which video the participant had watched as a between-participants method factor. In addition, we tested separately whether the coefficients stemming from the cross-correlation between feeling moved and positive affect and feeling moved and negative affect were different from zero by computing linear models with only the respective cross-correlation and video as a between subjects-factor. We would conclude that the cross-correlations were different from 0 if the models had a significant intercept. All tests were two-sided.

Results and discussion

On average across the sample (i.e. across the three different videos), the cross-correlations between feeling moved and positive affect were positive and moderate, Mz = 0.42, SDz = 0.42, CCF = 0.40, differed significantly from 0, F(1,124) = 87.03, p < .001, and did not depend on which video the participants had watched, F(2,124) = 2.35, p = .100 (). The cross-correlations between feeling moved and negative affect were on average negative and very small, Mz = −0.07, SDz = 0.37, CCF = –0.07 but still significantly different from 0, F(2,124) = 4.93, p = .028. In this case, the cross-correlation depended significantly on which video the participants had watched, F(2,124) = 4.64, p = .011, ranging from moderately negative, Mz = −0.20, SDz = 0.33, CCF = −0.20, for those who had watched “Thai” (which has a moving happy ending), to slightly positive, Mz = 0.04, SDz = 0.27, CCF = 0.04, for those who had watched “Two Orphans” (which has a bitter-sweet ending).

Figure 2. Cross-correlation functions (CCFs) between being moved and the respective variables in each study by video and across all videos.

Note: Cross-correlation functions for the single videos (Thai = “Thai Medicine”, Orph = “Two Orphans”, Abra = “Marina Abramović”) and the one averaging across the three videos (labelled “All”) are computed within individuals and then averaged. Cross-correlations labelled “Between” are added for comparison purposes. They were computed from time series that resulted from first averaging across participants (see Supplementary Material).

The difference between the cross-correlations between feeling moved and positive affect and feeling moved and negative affect was statistically significant, F(5,248) = 79.01, p < .001. While the overall size of the two cross-correlations did not depend on which video the participants watched, F < 1, there was a significant interaction between video and the within-subject factor, F(5,248) = 6.11, p = .003, meaning that the degree to which feeling moved cross-correlated more with positive affect than with negative affect did depend on which video the participants had watched.

Since the degree of cross-correlation between feeling moved and negative affect depended on the video, we followed up with one exploratory one-sample t-test for each video in order to test whether the cross-correlation was significantly different from 0 in each of them. The tests revealed that the cross-correlation was only significantly different from 0 in “Thai Medicine”, Mz = −0.20, SDz = 0.33, t(42) = 3.97, p < .001. For “Marina Abramović” it was close to 0, Mz = −0.05, SDz = 0.47, t < 1, as it was for “Two Orphans”, Mz = 0.04, SDz = 0.27, t < 1.

At least for the videos included in the study, these results support the claim that kama muta has positive valence and can, but does not have to, co-occur with negative affect. Seen together with Schubert et al.’s (Citation2018) finding that kama muta in many cases co-occur with self-reported happiness and sometimes co-occur with self-reported sadness, but is different from both happiness and sadness, the results support not only that kama muta is positive, but also that it is a distinct emotion.

We can also note that Study 1 replicated the previous results despite the fact that a different methodology was used. The within-subject cross-correlations were similar to but smaller than the between-sample cross-correlations.

The exploratory findings regarding “Two Orphans” – the representative of a sad but moving video – are particularly interesting in light of Schubert et al. (Citation2018) results. Schubert and colleagues’ found that feeling moved was not positively cross-correlated with happiness when the participants felt moved watching this tragic story. One possible explanation of our exploratory finding that is in line with the kama muta theory is that people nevertheless experience positive affect when they feel moved watching “Two Orphans”, and hence, in line with the kama muta theory, that in addition to being different from happiness and sadness, feeling moved is an inherently positive experience, even when it happens in response to a narrative generally found sad. But we stress the exploratory nature of this finding.

Study 2: feeling moved, warmth and goosebumps

There is generally theoretical consensus regarding which sensations are involved in being moved. Many theoretical and empirical investigations confirm that a sense of warmth (or a “tingling sensation”, often in the chest); chills or goosebumps and moist eyes or crying are common signs of being moved (see Zickfeld, Schubert, Seibt, & Fiske, Citation2019, for a review). But instances of kama muta vary between, as well as within, individuals. It is thus normal for an experience labelled being moved to include all, some or none of these sensations. The question is thus which sensations are more closely aligned with feelings of being moved. Study 2 tested if Schubert et al.’s results that self-reported feeling moved coincides with both goosebumps and a sense of warmth in the chest, but more with warmth than with goosebumps would replicate with our improved design. We will thus discuss these two sensations below, and largely ignore tears and crying in the current research.

The evidence and theorising regarding the mechanisms and functions of sensations are diverse and have been conducted from several different perspectives. There is more research on chills and goosebumps than on warmth, but most of the research on chills focuses on responses to music. As can be witnessed by studying other mammals, there is consensus that the original functions of piloerection in mammals were to keep the animal warm when feeling cold and to make the animal appear larger when threatened.

Chills and goosebumps are closely associated with negative emotions, especially sadness and fear (e.g. Darwin, Citation1872, pp. 178–197, 278–309). Some theoretical work characterises chills and goosebumps that occur in “moving” moments as resulting from such concurrent negative emotions. For instance, in a study of chills in response to music, Panksepp (Citation1995) suggested that goosebumps in response to moving music are caused by sadness involved. A related explanation is that emotions such as being moved and awe involve an encounter with the sublime which gives a sense of fear, and which in turn can explain the chills and goosebumps (Konecni, Citation2011).

Maruskin et al. (Citation2012) hypothesised that in humans, chills have evolved into having an intrapersonal function by signalling to oneself whether to engage in approach or avoidance. By factor analysis, they divided types of chills into the pleasant goosetingles, associated with feeling moved, awe, sexual arousal and apprehension of aesthetic beauty, and the unpleasant coldshivers, associated with coldness, anger, fear and sadness. The idea is that goosetingles provide a signal to oneself to approach and that coldshivers give a signal to oneself to avoid. Maruskin et al. (Citation2012) provide some preliminary evidence for this hypothesis, showing that goosetingles, but not coldshivers, predicted closeness to mother measured with Inclusion of the Other in the Self (Aron et al., Citation1992) when participants watched videos with themes that were not about mothers. The notion that there are two distinct variants of chills is supported by some psychophysiological evidence (Bannister & Eerola, Citation2021).

A more general explanation of pleasant chills characterises them as a symptom of peak arousal. Laeng et al. (Citation2016) and Salimpoor et al. (Citation2011) found that physiological markers of arousal predicted chills when listening to music. Letting participants choose movie clips that had moved them to tears in the past as stimuli, Wassiliwizky et al. (Citation2017) found that the co-occurrence of piloerection and tears indicated peak emotional arousal during those clips. However, Zickfeld et al. (Citation2020) found that experiences rated as very moving resulted in more goosebumps but less arousal compared to emotional experiences rated as sad.

Regarding warmth sensations, Haidt (Citation2003) has suggested that vagus nerve activity explains it as a sensation of elevation. Zickfeld et al. (Citation2020) tested whether the chest actually gets warmer by measuring skin temperature on the chest while showing participants moving videos. They found that there is a temperature increase associated with being moved relative to sadness. While it was significant, the increase was miniscule (0.02°C), and we think it, therefore, remains an open question whether this is associated with the subjective increase in temperature. Given the widespread self-reports of some experience in the chest during kama muta, however, it seems likely that there is some physiological basis to this experience, instead of it being simply the fallout of a metaphor.

Taken together, it is clear that goosebumps have multiple functions, possible come in two varieties, and are involved in several emotions, while subjective feelings of warmth are much more unique to experiences that involve feeling moved. The videos that we showed our participants are about 3 minutes long and evoke other emotions as well as kama muta. Because various emotional experiences involve goosebumps while warmth is relatively unique to being moved and kama muta, we hypothesised that feeling moved should cross-correlate more strongly with warmth than with goosebumps. However, we expected positive cross-correlations for both sensations. Schubert et al. (Citation2018) finding that warmth is cross-correlated with kama muta over and above other sensations is in line with previous studies as well (Zickfeld, Schubert, Seibt, Blomster, et al., Citation2019, Zickfeld et al., Citation2020), and it has been proposed that warmth is the most distinctive symptom of feeling kama muta (although, as people experience emotions differently, some people do not report this). Using the same methodology as in Study 1, we tested if this would also be what we find when we measure feeling moved, warmth and goosebumps within subjects.

Method

We used the same procedures as in Study 1, but with feeling moved, warmth (“ … whether you are feeling a sense of warmth in the chest or somewhere else in your body”; 3 levels: “no warmth”, “some warmth”, “a lot of warmth”) and goosebumps (“ … whether you are having goosebumps”; 2 levels: “no goosebumps”, “goosebumps”) as the items that the participants rated while watching the videos. We recruited in total of 197 participants. Of those, 11 were excluded for failing the attention check, 4 due to technical difficulties and 61 for having extreme or undefined cross-correlations between time series. This large number is mainly due to several people having no goosebumps at all. Our final sample consisted of 121 participants (51 female, 69 male, 1 prefer not to answer, age range: 18–71, median age: 33).

Results and discussion

Results were consistent with our hypotheses and Schubert et al.’s (Citation2018) results except that the cross-correlations were generally lower (see ). The average cross-correlation of feeling moved with sensed warmth, CCF = 0.43, Mz = 0.46, differed significantly from 0, F(2,118) = 183.94, p < .001. So did the cross-correlation with goosebumps, CCF = 0.25, Mz = 0.25, F(2,118) = 71.80, p < .001. While the cross-correlation with warmth did not vary by video, F < 1, the cross-correlation between feeling moved and goosebumps did, F(2,118) = 3.47, p = .034. It was highest in “Marina Abramović”, (Mz = 0.36) and lowest in “Thai Altruism”, (Mz = 0.16). The difference between the cross-correlations was statistically significant, F(5,236) = 19.86, p < .001. Video had no main effect in the test for the difference, F(5,236) = 1.94, p = .146, and did not interact with the within-participants factor (which pair of variables the coefficients were from), F(5,236) = 1.23, p = .293.

We attribute that we obtained much lower cross-correlations than Schubert et al. (Citation2018) to that Schubert and colleagues design and statistical approach literally averaged out the noise in the measures of cross-correlations. A possible reason why warmth coincided more with warmth than goosebumps is that warmth is a particularly distinctive indicator of kama muta, as previous research has also suggested. Warmth is particularly high for kama muta and less associated with related emotions (e.g. sadness) than other symptoms, such as goosebumps.

Study 3: feeling moved, closeness appraisal and morality appraisal

In Study 3, we tend to what appraisals are associated with feelings of being moved. This is perhaps the most contested area of work on being moved, with different theories putting forward different appraisals. Being moved has been described as an emotional phenomenon elicited by empathic caring (Batson et al., Citation1987) or by behaviour perceived as prosocial (Konecni, Citation2011); surpassing standards and praiseworthy (Landmann et al., Citation2019) or morally outstanding (Haidt, Citation2000, Citation2003). Others have proposed that being moved is elicited by the accentuation of something seen as good and of irreplaceable personal importance (Cova & Deonna, Citation2014; Cullhed, Citation2020; Deonna, Citation2020).

Kama muta theory posits that kama muta results from suddenly intensifying communal sharing relations, which are mirrored by appraisals of social closeness. Schubert et al. (Citation2018) found high cross-correlations between feeling moved and closeness measured using the Inclusion of Other in the Self-scale (IOS; Aron et al., Citation1992). The IOS uses the degree of overlap between two circles to represent the connectedness between people and resembles communal sharing conceptually. Thus, Schubert and colleagues’ results are highly compatible with the kama muta theory. The finding is confirmed by evidence from non-continuous measurements, where appraisals of social closeness have been found to predict being moved (Landmann et al., Citation2019; Seibt et al., Citation2018).

A common theme across the alternatives to kama muta theory for understanding being moved is that they posit that being moved is elicited by the appraisal of something as good – in a broad sense or specifically in a moral sense. Elevation is a widely studied and frequently mentioned theorised emotion elicited by the appraisal of outstanding moral behaviour (Haidt, Citation2000, Citation2003; Pohling & Diessner, Citation2016; Thomson & Siegel, Citation2017). Empirical evidence for its existence as a distinct emotion largely consists of findings that it is experienced separately from similar emotions such as joy, admiration and awe (see Pohling & Diessner, Citation2016, and; Thomson & Siegel, Citation2017 for reviews). Notably, elevation is often described and operationalised using terms such as “moved” and “touched” and also the typical sensations (warmth, goosebumps, tears) and prosocial motivations (Schnall et al., Citation2010; Sparks et al., Citation2019). Elevation is thus phenomenologically similar to kama muta and other conceptualizations of being moved.

Given that the phenomenology of kama muta and elevation are so similar, the question is whether appraisals of increased closeness (operationalising intensified communal sharing) as predicted by kama muta theory or appraisals of morality of observed behaviour as predicted by elevation theory are stronger predictors. Very few studies have tested whether appraisals of morality actually predict elevation, but Seibt et al. (Citation2017) found that both increased closeness and morality perceptions were predictive of kama muta. To follow up on this, we include perceived morality in Study 3. To extend on Schubert et al. (Citation2018) finding that feeling moved cross-correlated greatly with closeness, Study 3 thus also measured perceived morality continuously. We predicted that the measures of feeling moved would cross-correlate positively with appraisals of closeness. We also predicted that feeling moved would cross-correlate more with appraisals of closeness than with appraisals of morality. Although we expected appraisals of morality to often be closely associated with being moved, we reasoned that, according to kama muta theory, the appraisal of intensification of communal sharing should be present in all experiences of being moved (assuming that they are not referring to other emotions than kama muta) and therefore cross-correlate more with feeling moved than morality when we look at a variety of eliciting events.

Method

As in Study 1, we had a target of 120 participants. We used the same inclusion and exclusion criteria and the same strategy to reach the target number of participants. We recruited 177 participants in total. Of those, 21 were excluded for failing the attention check, 2 participants due to technical difficulties and 34 were excluded because of extreme or undefined cross-correlations. Our final sample consisted of 120 participants (70 male, 49 female, 1 other; age range 18–70, median age = 31).

We followed the same procedure as in Study 1, except that the scales for positive and negative affect were replaced with scales for appraisals of closeness and morality. The participants rated appraisals of closeness using a modified version of the Inclusion of Other in Self (IOS)-scale (see Supplementary material), which uses overlapping circles to represent the degree of closeness between people. For the perceived level of morality, we were not aware of an existing measure and therefore used an ad-hoc item: “Please rate the extent to which you find what you see morally good/right” with a five-point scale.

The data preparation and inferential statistics were the same as in Study 1. We preregistered one prediction: that the cross-correlation between feeling moved and appraisals of closeness would be greater than the cross-correlation between feeling moved and appraisals of morality.

Results and discussion

We predicted that time series of appraisals of closeness would have a greater cross-correlation with time series of feeling moved than time series of appraisals of morality would. Time series of feeling moved had positive cross-correlations that were significantly different from 0 both with appraisals of closeness, CCF = 0.36, Mz = 0.38, F(2,117) = 61.71, p < .001, and appraisals of morality, CCF = 0.30, Mz = 0.31, F(2,117) = 61.88, p < .001 (see ). Which video the participants had watched did not affect the strength of the cross-correlations, neither between feeling moved and appraisals of closeness, F < 1, nor between feeling moved and appraisals of morality, F(2,117) = 1.02, p = .363.

Against our prediction, the cross-correlations did not differ significantly from each other, F(5,234) = 1.00, p = .318. Video had no main effect, F < 1, and did not interact with the within participants-factor (whether we were looking at the cross-correlation between feeling moved and closeness or feeling moved and morality), F(5,234) = 1.51, p = .223, meaning that the difference between the two cross-correlations did not depend on which video the participants had watched. To explore whether the explanation could be that self-reports of perceived closeness and self-reports of perceived morality are essentially identical measures, we checked the correlation between closeness and morality. It was moderate, r = .34. In an additional exploratory multilevel (mixed) model, we explored how the two appraisals predicted when controlling for each other. The results confirmed that both appraisals had independent influences (see Supplementary Materials).

While the cross-correlation between feeling moved and closeness replicated Schubert et al.’s (Citation2018) findings and is in line with kama muta theory, we did not find support for our prediction that the cross-correlation with appraisals of closeness would be greater than the cross-correlation with appraisals of morality. However, there is a reason to interpret this result cautiously: Looking at the cross-correlations for the individual videos, we were surprised to see that the overlap between feeling moved and appraisals of morality was high even in the video “Marina Abramovic”. We had included it in our stimulus set precisely because we thought of it as not including any outstanding moral behaviour. Participants rated this simple scene that showed a melancholic encounter between past partners as displaying considerable morality. This can mean that our participants have a different view of morality than we do or that they judge “how morally good they find something” in a different way than we anticipated. In other words, we question the validity of our own, admittedly ad hoc and unvalidated, item. It is plausible that the participants rated the moral goodness that they perceived based on an intuitive judgement or gut feeling, and it is plausible that such a gut feeling is merely based on the participants’ emotional reaction. If so, it could be the feeling of being moved (and perhaps other emotions) that caused the participants subjective judgements of morality. (Of course, a similar argument could be made for closeness, but that item at the very least relied on a validated scale.)

However, if the results for the morality judgment can be taken at face (validity) value, they are only compatible with kama muta theory if it can be shown that the morality judged here is based on applying communal sharing standards, so that morality appraisals also reflect the intensification of communal sharing. As an example, consider the climax in “Thai Medicine”: The doctor pays the patient’s hospital bill while leaving a note saying that “all expenses were paid 30 years ago with 3 packs of painkillers and a bag of veggie soup”, a reference to a scene in the beginning, in which the doctor was a young boy and received medicines and soup for his mother from the patient. The doctor shares his money according to the patient’s need and his own ability, just as the patient did in the past, applying communal sharing standards. The climax is thus moral within the frame of communal sharing, and intense because it contrasts with proportionality standards.

Acts can also be moral outside of the relational frame of communal sharing. Obedience to a legitimate leader or deity that leads to sacrifice, standing in for equality in the face of prejudice or large efforts to repay debts may be perceived as highly moral acts in the frames of authority ranking, equality matching and market pricing, respectively (Fiske, Citation1992). Evidence that such morality can explain feeling moved would falsify the kama muta theory. Instead, it would count in favour of other accounts of being moved such as Cova and Deonna’s theory that allows for various types of positive values to independently be sufficient to evoke being moved, or that being moved by moral events can be best explained by elevation theory.

In sum, while the results confirm that social closeness predicts feeling moved, this is not the only predictor. The situation is similar to the findings of Landmann et al. (Citation2019), who also found both social closeness and extraordinary achievements to predict being moved. Research on kama muta theory has to confront this challenge and investigate theoretically and empirically whether and when morality judgments are appropriate to operationalise communal sharing besides or above closeness judgments.

General discussion

The current studies tested the co-occurrence of feeling moved and six other variables. Improving upon prior work reported by Schubert et al. (Citation2018), we tested for co-occurrence within participants rather than between participants. The studies were partly tests whether the earlier findings would replicate with stricter methodology, and partly tests of new hypotheses. Showing our participants three different moving videos and asking them to rate three different variables continuously while watching the video, we found, as predicted, that participants’ ratings of feeling moved cross-correlated with their own ratings of closeness, positive affect, warmth and goosebumps. Also as predicted, the cross-correlation with feeling moved was greater for positive affect than for negative affect (for which it was ever so slightly negative) and greater for warmth than for goosebumps (while both were significant). Against our predictions, there was no greater cross-correlation between feeling moved and closeness appraisals than between feeling moved and morality appraisals; instead, both were positive and significant.

The current results replicate all those repeated from Schubert et al. (Citation2018) but allow for stronger inferences about how individuals’ experience of kama muta because the correlations were measured within the participants. They also replicate previous findings regarding the valence and sensations of being moved, as well as results from previous research on kama muta that confirm the strong correlation between self-reported being moved and appraisals of closeness as well as morality (Seibt, Schubert, Zickfeld, & Fiske, Citation2017; Zickfeld, Schubert, Seibt, Blomster, et al., Citation2019). Beyond appraisals, the correlates of feeling moved (goosebumps, warmth, positive affect) that we found show that this emotional experience closely resembles the description of moral elevation (Haidt, Citation2000, Citation2003). This provides further support for the claim that moral elevation is better understood as a specific type of instance of the feeling that we often call being moved or feeling moved. Proponents of the kama muta theory as well as other researchers of being moved have defended this claim (Cova et al., Citation2017; Seibt, Schubert, Zickfeld, & Fiske, Citation2017).

Several exploratory findings are also interesting in light of previous results and theorising. While feeling moved consistently coincided with positive affect across the three different videos, including the most sad one, it had an almost negligible cross-correlation with negative affect on average, and was only cross-correlated with negative affect for the sad video. This may suggest that, contrary to Menninghaus et al. (Citation2015) conclusions, experiencing negative affect is not a necessary constituent of being moved. This is consistent with the kama muta theory, which holds that kama muta is a positive emotion that is elicited by appraisals of sudden intensifications of communal sharing of any kind (Fiske, Schubert, et al., Citation2017). Reasoning from the kama muta theory as well as other understandings of being moved, it can seem plausible that experiences of being moved are felt more strongly when the eliciting situation follows or is held against a background of something that elicits negative feelings. This is because the negative event could make the perceived intensification of communal sharing greater or make whichever appraisal that elicits being moved more salient (Cova & Deonna, Citation2014; Fiske, Citation2019, pp. 92–94; Strick & van Soolingen, Citation2018). But it is an open question whether people experience stronger kama muta or feeling moved when it emerges from a sad event.

Comparing time series calculated within participants vs. averaged across participants

The current work was motivated by the realisation that as long as there is dispersion in the variables (as is virtually always the case in psychology) we cannot infer within-subject processes from between-subject comparisons without making assumptions not found in the data itself. Recent work has forcefully pointed this out (Borsboom et al., Citation2003; Fisher et al., Citation2018; Hamaker, Citation2012; Kievit et al., Citation2013). The only conclusion one can make after observing a correlation between one reaction to a stimulus in one group and another reaction to the same stimulus in another group is that the stimulus has properties that elicit both responses. But the observation cannot prove anything about the relationship between the two reactions as they occur within individuals. Therefore, the different measures must be made on the same individuals to infer about how the measures relate to each other on the individual level. This is not merely a theoretical concern. By reanalysing data from six clinical studies, Fisher et al. showed that the bivariate correlations between nine clinically relevant variables were often larger and always less variable at the inter-individual level than at the intra-individual level.

The current data show the averaged within-participants cross-correlations that we observed were always much smaller than the cross-correlations of averaged time series (for identical items and videos). We believe the primary reason is that the intra-individual correlations are subject to a lot more noise (i.e. measurement error) from the continuous measurement than averaged time series, where this noise is literally averaged out.Footnote5 The difference may also reflect a true difference between inter-individual and intra-individual cross-correlations in the sense that over and above cancelling out noise, averaged reactions are better predicted by other averaged reactions, for instance, because not all people react in the same component. If one set of participants readily experiences one but not another physical sensation, while another set of participants reacts in the opposite way, the averaged curves would still cross-correlate. Our data cannot explain whether cancelled noise or true difference between intra- and inter-individual data account for more of the difference in cross-correlations.

Another benefit from computing the cross-correlations at the intra-individual level before averaging across individuals is that we could observe and appreciate the substantial individual differences in the characteristics of the feeling moved experience. While every variable that we measured on average cross-correlated significantly with feeling moved (although the cross-correlation with negative affect was only −.08), for every variable except warmth, the standard deviation of the Fisher z-coefficients obtained from the correlation coefficients was greater than the absolute size of their means. Hence, it was common for participants to deviate from the average experience of feeling moved, and for each cross-correlation with feeling moved there were participants with values much higher or lower than average, and cross-correlations with the opposite sign (ranging from 10.7% of the participants for warmth to 39.9% of the participants for negative affect).

The problem of inferring intra-individual processes from inter-individual comparisons is prevalent in other designs as well, but every study must be scrutinised individually. Take Benedek and Kaernbach (Citation2011) as a first example. They investigated physiological and experiential correlates of goosebumps during listening to moving music. Using a camera, they objectively classified trials into whether goosebumps occurred or not on participants’ arms, and then calculated differences in other physiological parameters (e.g. breathing depth, which showed the largest effect) and feelings (e.g. being moved) depending on the presence of goosebumps. This analysis design allows intra-individual inferences regarding the co-occurrence of goosebumps with the other two phenomena, but not regarding the co-occurrence of being moved and deep breaths.

However, the problem extends to more common designs. One must measure the variables repeatedly within the same participants to draw intra-individual inferences. We are unfortunately sure that we ourselves have overgeneralised many correlations in this way in previous work.

Limitations

Note that we, in this research, test predictions about what the experience we often call “being moved” should correlate with if kama muta theory were correct. We assume that self-reported levels of “feeling moved or touched” operationalise kama muta, where “feeling” is understood as one’s own categorisation of an experience (Clore, Citation1992). When we test predictions from kama muta theory about being moved against predictions from other accounts of being moved and when we use other research on being moved to inform about kama muta, we assume that both research on kama muta and other research on being moved studies the same phenomenon. We think that these assumptions can be reasonably justified, but that they are also problematic. On the one hand, the concept of kama muta was conceived of in part to counter the fact that the term “being moved” does not consistently refer to one particular state. But on the other hand, self-reported “being moved” has nevertheless been strongly correlated with a multi-item kama muta-measure in previous research (Zickfeld, Schubert, Seibt, Blomster, et al., Citation2019), and it is repeatedly noted that kama muta is the emotion that we usually have when we say that we feel moved (Fiske, Citation2019; Fiske, Schubert, et al., Citation2017; Fiske, Seibt, et al., Citation2019).

Although there are benefits both to continuous measures and measuring cross-correlations within-subjects, there are also challenges and limitations inherent in our design. A prominent limitation is that continuous self-report measures necessitate using single-item scales to measure appraisals, valence and sensations. Presumably, people lack the attentional capacity to rate multiple items at once without letting the items compromise each other, and it would be demanding to ask participants to watch their video even more than three times in a row. But single-item scales have limited validity and reliability by their nature. Conventional studies use multi-item measures to get comprehensive and exact estimates of participants’ levels on mental states that are best defined and described by multiple features and terms. Our single-item scales are incomplete and less robust. An atypical interpretation of an item (e.g. mistakenly interpreting “closeness” as physical closeness), a delayed response or a single mistake could substantially change a time series and, in turn, how it cross-correlates with another time series.

A related limitation is that we relied on several new measures that were not previously validated. This may have been a problem, especially for the morality item, in which the phrasing “how morally good/right” could be interpreted as “how morally good or morally right”, as we intended or as “how morally good or how right”, for which “right” may be interpreted in a non-moral way.

Finally, note that we make one assumption that is worth mentioning. Although we interpret our data as showing that changes happen simultaneously, we measure them on three separate occasions, and align them using time series. This is different from some psychophysiological studies that do measure their variables truly simultaneously (e.g. Wassiliwizky et al., Citation2017; Zickfeld et al., Citation2020), but similar to other studies that measure psychophysiology in a first viewing and experiences during a second viewing (Hofmann et al., Citation2021). In the future, it might be interesting to explore the simultaneous measurement of two meaningful dimensions simultaneously (Fayn et al., Citation2022).

Conclusion

The three studies we presented here contribute to a growing body of research that shows that there is a distinct emotion that is not always mentioned in taxonomies of emotions and is often referred to as “being moved” in daily language. The data presented here provide a strong test of the kama muta theory developed for this emotion at the level of intra-individual processes – confirming it in two instances (valence, sensations) and challenging it in one instance (appraisals). Intensification of social closeness is one, but perhaps not the only, appraisal involved (see also Landmann et al., Citation2019). Interesting avenues for future research on kama muta (or alternative accounts of this emotion) thus include the precise nature of its appraisals.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (235.1 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 These terms are virtually used interchangeably in recent literature, and we treat them as such. When citing others, we use the same term as they use.

2 We had preregistered hypotheses regarding the relationship between these constructs and feeling moved. For ease of presentation, these data are not reported in the main manuscript, but the analyses and results regarding these hypotheses can be found in the appendix.

3 In our data, this mainly occurred when participants only registered reactions at the very end, which we consider as not fulfilling the task. One could wonder whether such extreme correlations would be plausible if, for example, a participant did not feel moved and not have positive affect for the whole video except for at the very end. In our view, this would be more akin to a post-experience measure rather than a continuous measure. We did not anticipate this issue in the pre-registration, but because we found it very plausible that such responses would not be valid and distort our results, we decided to update the preregistration upon this realization after Study 1. This was the only change from the original preregistration.

4 Correlations cannot be computed between variables for which one has zero variability. Because the most appropriate interpretation of the relationship between variables in such cases would be that there is no statistical association, we discussed treating such correlations as if they were 0. But we instead decided to exclude them, reasoning that we had formulated our hypotheses to imply that there will be a relationship between two reactions only when the video was to elicit both.

5 To explore this explanation, we did an additional analysis where we computed cross-correlations in a similar way to Schubert et al. (Citation2018) by taking averaged time-series of a variable in one sample (e.g. Study 1) and cross-correlating it with averaged time-series of another variable across the other two samples (e.g. Studies 2 and 3). Supporting our explanation, each of the cross-correlation functions were greater in absolute terms when calculated this way. The results are found in Supplementary Table 3 and illustrated in alongside the main results from Studies 1, 2 and 3.

References

- Aron, A., Aron, E. N., & Smollan, D. (1992). Inclusion of other in the self scale and the structure of interpersonal closeness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 63(4), 596–612. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.63.4.596

- Bannister, S., & Eerola, T. (2021). Vigilance and social chills with music: Evidence for two types of musical chills. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1037/aca0000421

- Batson, C. D., Fultz, J., & Schoenrade, P. A. (1987). Distress and empathy: Two qualitatively distinct vicarious emotions with different motivational consequences. Journal of Personality, 55(1), 19–39. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.1987.tb00426.x

- Becerra, R., Preece, D., Campitelli, G., & Scott-Pillow, G. (2019). The assessment of emotional reactivity across negative and positive emotions: Development and validation of the Perth Emotional Reactivity Scale (PERS). Assessment, 26(5), 867–879. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191117694455

- Benedek, M., & Kaernbach, C. (2011). Physiological correlates and emotional specificity of human piloerection. Biological Psychology, 86(3), 320–329. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsycho.2010.12.012

- Blyth, C. R. (1972). On Simpson’s paradox and the sure-thing principle. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 67(338), 364–366. https://doi.org/10.1080/01621459.1972.10482387

- Borsboom, D., Mellenbergh, G. J., & van Heerden, J. (2003). The theoretical status of latent variables. Psychological Review, 110(2), 203–219. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.110.2.203

- Clore, G. L. (1992). Cognitive phenomenology: Feelings and the construction of judgment. In The construction of social judgments (pp. 133–163). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates

- Cova, F., Deonna, J., & Sander, D. (2017). “That’s deep!”: The role of being moved and feelings of profundity in the appreciation of serious narratives. In D. R. Wehrs & T. Blake (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook of affect studies and textual criticism (pp. 347–369). Springer International. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-63303-9_13

- Cova, F., & Deonna, J. A. (2014). Being moved. Philosophical Studies, 169(3), 447–466. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-013-0192-9

- Cullhed, E. (2020). What Evokes Being Moved? Emotion Review, 12(2), 111–117. http://doi.org/10.1177/1754073919875216.

- Darwin, C. R. (1872). The expression of the emotions in man and animals (1st ed.). Darwin Online. http://darwin-online.org.uk/content/frameset?pageseq=1&itemID=F1142&viewtype=text

- Deonna, J. A. (2020). On the good that moves US. The Monist, 103(2), 190–204. https://doi.org/10.1093/monist/onz035

- Fayn, K., Willemsen, S., Muralikrishnan, R., Castaño Manias, B., Menninghaus, W., & Schlotz, W. (2022). Full throttle: Demonstrating the speed, accuracy, and validity of a new method for continuous two-dimensional self-report and annotation. Behavior Research Methods, 54(1), 350–364. http://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-021-01616-3

- Festinger, L. (1957). A theory of cognitive dissonance (pp. Xi, 291). Stanford University Press.

- Fisher, A. J., Medaglia, J. D., & Jeronimus, B. F. (2018). Lack of group-to-individual generalizability is a threat to human subjects research. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 115(27), E6106–E6115. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1711978115

- Fiske, A. P. (1992). The four elementary forms of sociality: Framework for a unified theory of social relations. Psychological Review, 99(4), 689–723. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.99.4.689

- Fiske, A. P. (2004). Relational models theory 2.0. In N. Haslam (Ed.), Relational models theory: A contemporary overview (pp. 3–25). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Fiske, A. P. (2019). Kama muta: Discovering the connecting emotion. Routledge.

- Fiske, A. P., Schubert, T. W., & Seibt, B. (2017). “Kama muta” or ‘being moved by love’: A bootstrapping approach to the ontology and epistemology of an emotion. In J. Cassaniti & U. Menon (Eds.), Universalism without uniformity: Explorations in mind and culture (pp. 79–100). University of Chicago Press.

- Fiske, A. P., Seibt, B., & Schubert, T. W. (2019). The Sudden Devotion Emotion: Kama Muta and the Cultural Practices Whose Function Is to Evoke It. Emotion Review, 11(1), 74–86. http://doi.org/10.1177/1754073917723167

- Frijda, N. H. (2001). Foreword. In A. J. J. M. Vingerhoets & R. R. Cornelius (Eds.), Adult crying: A biopsychosocial approach (Vol. 3, pp. xii–xviii). Brunner-Routledge.

- Haidt, J. (2000). The positive emotion of elevation. Prevention & Treatment, 3(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1037/1522-3736.3.1.33c

- Haidt, J. (2003). Elevation and the positive psychology of morality. In C. L. M. Keyes & J. Haidt (Eds.), Flourishing: Positive psychology and the life well-lived (pp. 275–289). American Psychological Association.

- Hamaker, E. L. (2012). Why researchers should think “within-person”: A paradigmatic rationale. In M. R. Mehl & T. S. Conner (Eds.), Handbook of research methods for studying daily life. (pp. 43–61). The Guilford Press.

- Hofmann, S. M., Klotzsche, F., Mariola, A., Nikulin, V., Villringer, A., & Gaebler, M. (2021). Decoding subjective emotional arousal from EEG during an immersive virtual reality experience. ELife, 10, e64812. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.64812

- Kievit, R. A., Frankenhuis, W. E., Waldorp, L. J., & Borsboom, D. (2013). Simpson’s paradox in psychological science: A practical guide. Frontiers in Psychology, 4, 1–14https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00513

- Konecni, V. J. (2011). Aesthetic trinity theory and the sublime. Philosophy Today, 55(1), 64–73. https://doi.org/10.5840/philtoday201155162

- Laeng, B., Eidet, L. M., Sulutvedt, U., & Panksepp, J. (2016). Music chills: The eye pupil as a mirror to music’s soul. Consciousness and Cognition, 44, 161–178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.concog.2016.07.009

- Landmann, H., Cova, F., & Hess, U. (2019). Being moved by meaningfulness: Appraisals of surpassing internal standards elicit being moved by relationships and achievements. Cognition and Emotion, 33(7), 1387–1409. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2019.1567463

- Maruskin, L. A., Thrash, T. M., & Elliot, A. J. (2012). The chills as a psychological construct: Content universe, factor structure, affective composition, elicitors, trait antecedents, and consequences. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 103(1), 135. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028117

- Mauss, I. B., Levenson, R. W., McCarter, L., Wilhelm, F. H., & Gross, J. J. (2005). The Tie that binds? Coherence among emotion experience, behavior, and physiology. Emotion, 5(2), 175–190. https://doi.org/10.1037/1528-3542.5.2.175

- Menninghaus, W., Wagner, V., Hanich, J., Wassiliwizky, E., Jacobsen, T., & Koelsch, S. (2017). Negative emotions in art reception: Refining theoretical assumptions and adding variables to the distancing-embracing model. The Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 40, e380. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X17001947

- Menninghaus, W., Wagner, V., Hanich, J., Wassiliwizky, E., Kuehnast, M., & Jacobsen, T. (2015). Towards a psychological construct of being moved. PLOS ONE, 10(6), e0128451. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0128451

- Otten, S., & Wentura, D. (2001). Self-anchoring and in-group favoritism: An individual profiles analysis. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 37(6), 525–532. https://doi.org/10.1006/jesp.2001.1479

- Panksepp, J. (1995). The emotional sources of chills induced by music. Music Perception, 13(2), 171–207. https://doi.org/10.2307/40285693

- Pohling, R., & Diessner, R. (2016). Moral elevation and moral beauty: A review of the empirical literature. Review of General Psychology, 20(4), 412–425. https://doi.org/10.1037/gpr0000089

- Preece, D., Becerra, R., Robinson, K., Dandy, J., & Allan, A. (2018). The psychometric assessment of alexithymia: Development and validation of the Perth Alexithymia Questionnaire. Personality and Individual Differences, 132, 32–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2018.05.011

- Salimpoor, V. N., Benovoy, M., Larcher, K., Dagher, A., & Zatorre, R. J. (2011). Anatomically distinct dopamine release during anticipation and experience of peak emotion to music. Nature Neuroscience, 14(2), 257–262. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.2726

- Schnall, S., Roper, J., & Fessler, D. M.T. (2010). Elevation leads to altruistic behavior. Psychological Science, 21(3), 315–320. http://doi.org/10.1177/0956797609359882.

- Schubert, T. W., Zickfeld, J. H., Seibt, B., & Fiske, A. P. (2018). Moment-to-moment changes in feeling moved match changes in closeness, tears, goosebumps, and warmth: Time series analyses. Cognition and Emotion, 32(1), 174–184. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2016.1268998

- Seibt, B., Schubert, T. W., Zickfeld, J. H., & Fiske, A. P. (2017). Interpersonal closeness and morality predict feelings of being moved. Emotion, 17(3), 389–394. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000271

- Seibt, B., Schubert, T. W., Zickfeld, J. H., Zhu, L., Arriaga, P., Simão, C., Nussinson, R., & Fiske, A. P.. (2018). Kama Muta: Similar emotional responses to touching videos across the United States, Norway, China, Israel, and Portugal. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 49(3), 418–435. http://doi.org/10.1177/0022022117746240.

- Sparks, A. M., Fessler, D. M. T., & Holbrook, C. (2019). Elevation, an emotion for prosocial contagion, is experienced more strongly by those with greater expectations of the cooperativeness of others. PLOS ONE, 14(12), e0226071. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0226071

- Steinnes, K. K., Blomster, J. K., Seibt, B., Zickfeld, J. H., & Fiske, A. P. (2019). Too cute for words: Cuteness evokes the heartwarming emotion of kama muta. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 387. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00387

- Strick, M., & van Soolingen, J. (2018). Against the odds: Human values arising in unfavourable circumstances elicit the feeling of being moved. Cognition and Emotion, 32(6), 1231–1246. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2017.1395729

- Thomson, A. L., & Siegel, J. T. (2017). Elevation: A review of scholarship on a moral and other-praising emotion. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 12(6), 628–638. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2016.1269184

- Vuoskoski, J. K., Zickfeld, J. H., Alluri, V., Moorthigari, V., & Seibt, B. (2022). Feeling moved by music: Investigating continuous ratings and acoustic correlates. PLOS ONE, 17(1), e0261151. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0261151

- Wassiliwizky, E., Jacobsen, T., Heinrich, J., Schneiderbauer, M., & Menninghaus, W. (2017). Tears falling on goosebumps: Co-occurrence of emotional lacrimation and emotional piloerection indicates a psychophysiological climax in emotional arousal. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 41. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00041

- Zickfeld, J. H., Arriaga, P, Santos, S. V., Schubert, T. W., & Seibt, B. (2020). Tears of joy, aesthetic chills and heartwarming feelings: Physiological correlates of Kama Muta. Psychophysiology, 57(12). http://doi.org/10.1111/psyp.v57.12

- Zickfeld, J. H., Schubert, T. W., Seibt, B., Blomster, J. K., Arriaga, P., Basabe, N., Blaut, A., Caballero, A., Carrera, P., Dalgar, I., Ding, Y., Dumont, K., Gaulhofer, V., Gračanin, A., Gyenis, R., Hu, C.-P., Kardum, I., Lazarević, L. B., Mathew, L., … Fiske, A. P. (2019). Kama muta: Conceptualizing and measuring the experience often labelled being moved across 19 nations and 15 languages. Emotion, 19(3), 402–424. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000450

- Zickfeld, J. H., Schubert, T. W., Seibt, B., & Fiske, A. P. (2019). Moving through the literature: What is the emotion often denoted being moved? Emotion Review, 11(2), 123–139. https://doi.org/10.1177/1754073918820126