ABSTRACT

Previous research has found a rich lexicon of shame and guilt terms in Chinese, but how comparable these terms are to “shame” or “guilt” in English remains a question. We identified eight commonly used Chinese terms translated as “shame” and “guilt”. Study 1 assessed the Chinese terms’ intensities, social characteristics, and action tendencies among 40 Chinese speakers. Testing term production in the reverse direction, Study 2 asked another Chinese-speaking sample (N = 85) to endorse emotion terms in response to eight eliciting scenarios generated using each term’s social characteristics from Study 1. A native English-speaking sample (N = 83) was also included to examine the production of English emotion terms and compare motivational tendencies cross-culturally. Using this cross-referencing method, we found that some of the Chinese terms shared similar social-functional characteristics to their English translation, but some had distinct profiles. The two large shame-like and guilt-like term categories yielded in Study 1 were replicated in Study 2’s Chinese term-production task where larger-scale correspondences between categorised elicitors and term clusters were found. Meanwhile, English speakers’ term use provided further evidence for the equivalence between some Chinese terms and “shame” or “guilt” both in terms of their social and motivational characteristics.

Shame and guilt are complex emotions that regulate reactions to one’s own transgressions. Research on differences between the two has accumulated in Western psychology since the 1990s (e.g. Baumeister et al., Citation1994; Keltner, Citation1996; Tangney, Citation1995), but with little consistent extension to other languages and cultures. Especially with complex emotions, it is questionable whether the meaning of English emotion terms can generalise to other languages (Wierzbicka, Citation1986). Moreover, it is possible that even terms roughly similar in translation can have different social connotations, which brings great challenges to cross-cultural research on emotions. Focusing on eight Chinese terms translated as “shame” or “guilt”, we took a cross-referencing approach to examine these Chinese terms’ comparability with their English counterparts on their social-functional characteristics. The purpose of the current research was twofold: We hope to lay the ground for term selection and verbal emotion measures for future research on shame and guilt in Chinese and cross-culturally, and we also hope to provide a different approach to examining equivalence between emotion terms from different languages.

Social appraisal dimensions differentiating shame and guilt in western culture

In a large research literature primarily developed among English and Western European languages, shame and guilt are defined as self-conscious negative emotions evoked when people recognise their own wrong behaviours or negative attributes (Haidt, Citation2003; Lewis, Citation1971; Tangney & Tracy, Citation2012; Wong & Tsai, Citation2007). These emotions in turn motivate self-relevant intentions and behaviours (Baumeister et al., Citation1994; Tangney & Dearing, Citation2002). In Western usage, shame and guilt have been proposed to differ in several social characteristics, but with little agreement on which are key.

Moral/non-moral

Guilt has been described as more morally relevant than shame (Giner-Sorolla, Citation2012; Tangney & Tracy, Citation2012), being prototypically associated with moral violations such as harm to others, while shame can be induced by both serious moral transgressions and non-moral failures such as social or competence blunders (Ferguson et al., Citation1991; Sabini & Silver, Citation1997; Smith et al., Citation2002; Tangney et al., Citation1996; van der Lee et al., Citation2016).

Public exposure/private

Many accounts propose that shame is “usually dependent on the public exposure of one’s frailty or failing” (Gehm & Scherer, Citation1988, p. 74), while guilt is driven by internalised standards (Campos et al., Citation1983). Shame is more likely than guilt to be felt in literal public situations, as well as when imagining public exposure (Smith et al., Citation2002; Tangney et al., Citation1996).

Close/distant social relations

Baumeister et al. (Citation1994, p. 245) proposed that guilt is mostly elicited when one’s behaviour inflicts “harm, loss or distress on a relationship partner”, and it is “stronger, more common, and more influential in close relationships than in weak or distant ones”. Tangney et al. (Citation1996) also found that shame versus guilt was more likely in the presence of acquaintances than close others.

Equal/hierarchical relations

Functional evolutionary accounts interpret shame as regulating hierarchical relations between perceived superiors and inferiors, while guilt regulates reciprocal relations between equals (Fessler, Citation2007; Lebra, Citation1971). Some evidence does suggest that shame, more so than guilt, is related to feelings of inferiority towards people higher in the social hierarchy (Gilbert et al., Citation1994).

Action tendencies

Guilt and shame are also thought to entail different action motives, with some controversy about the nature of the distinction. Guilt has been found to drive reparative, constructive actions such as apologies and compensation (e.g. Baumeister, Stillwell, et al., Citation1995; de Hooge et al., Citation2007; Ketelaar & Au, Citation2003). Shame, though, is often linked with maladaptive responses such as social withdrawal, arguably because it involves flaws in the core self instead of behaviours that can be compensated (Lewis, Citation1971; Tangney, Citation1995). However, Western research also has identified an adaptive function of shame, promoting prosocial or image-repair activities similar to guilt’s (de Hooge et al., Citation2008, Citation2010, Citation2018; Gausel & Leach, Citation2011; Lickel et al., Citation2014). Sheikh (Citation2014) suggested that the maladaptive side of shame is more common in individualistic cultures, while Leach and Cidam's (Citation2015) meta-analysis found that shame can promote either withdrawal or engagement, the latter occurring when one’s failure or bad image was seen as reparable.

Shame and guilt from a cultural perspective

Guilt and shame centrally involve the self (Tracy & Robins, Citation2007), so self-construal should influence them. Unlike cultures that construe the self as independent, interdependent cultures highly value harmonious relationships (Markus & Kitayama, Citation1991; Triandis, Citation1988). Due to their significance in social relations, shame and guilt might be more central in interdependent cultures such as China, than in individualistic cultures such as Europe and the USA (Fessler, Citation2004). Shaver et al. (Citation1992) examined prototypical emotion categories in English, Italian, Chinese and Indonesian and found only Chinese produced a separate basic cluster of self-critical emotions including shame, guilt and embarrassment.

Besides collectivism-individualism, other cultural dimensions such as power distance and the degree of hierarchy were also found shaping the meaning of shame and guilt (Silfver-Kuhalampi et al., Citation2013; Young et al., Citation2021). Values widely shared in a society could influence the two emotions too. Confucianism, for example, the social philosophy foundational to Chinese ethics, highly values the cultivation of virtues such as benevolence and righteousness in a life-long process of self-improvement (Hwang, Citation2001; Tu, Citation1978). Consequently, having a sense of shame has positive implications in Chinese culture, because it motivates self-reflection and self-cultivation (Mascolo et al., Citation2003; Wong & Tsai, Citation2007). By contrast, Western psychology offers accounts of shame’s reparative or avoidant tendencies, as remarked earlier, but has little to say about its role in regulating character or self-improvement.

Acknowledging the impact of various cultural characteristics on shame and guilt, however, the current research mainly concerned whether translated emotion terms in two languages are equivalent in their social-functional characteristics, a question most cross-cultural research on emotions needs to ask initially. Thus, we next review commonly adopted approaches in previous cross-linguistic research on shame and guilt and then focus on lexical studies of the two emotions in Chinese.

Common approaches to cross-cultural research on shame and guilt

Various approaches have been taken to compare shame and guilt cross-culturally. Some start with emotion terms (the "translation method”, Ogarkova et al., Citation2012). Using the terms “shame” and “malu” (Indonesian translation of “shame”) as prompts, Fessler (Citation2004) collected and coded accounts of naturally-occurring instances in the United States and Indonesia. Instead of coding responses, Lewandowska-Tomaszczyk and Wilson (Citation2014) measured native speakers’ responses to English “shame”, “guilt,” and corresponding Polish translations (wstyd and wina) with an instrument measuring 144 features of emotions (Fontaine et al., Citation2013). Using the same set of features, Silfver-Kuhalampi et al. (Citation2013) tested 34 national samples’ responses to shame and guilt (their translated terms) and concluded that the two emotions are generally differentiated in very similar ways across cultures, such as shame involving public exposure and withdrawal tendencies and guilt involving a concern for others and reparation tendencies.

Other approaches have used emotion-eliciting scenarios as stimuli (the "mapping/reference-based method”, Ogarkova et al., Citation2012), and emotion terms as measures. Kollareth et al. (Citation2018) had native American-English, Spanish, and Malayalam speakers read stories of non-moral and moral violations and indicate the protagonists’ emotion on scales of “shame”, “guilt”, and their translations in Spanish and Malayalam. Ogarkova et al. (Citation2012) examined five European cultural groups’ freely listed emotion terms in response to constructed scenarios capturing multiple facets of shame, guilt, anger and pride. Although most of these studies used one-to-one translation of emotion terms starting from English, equivalence of terms from different languages is not always perfect. For example, Mendoza et al. (Citation2010) showed that “shame” and its translation in Spanish, vergüenza, have different features, and even their shared features differ in typicality. In general, emotion terms are important to existing cross-cultural emotion research whether they are used as the stimulus (the translation method) or as the measures (the mapping method).

Previous research on Chinese terms of shame and guilt

The translation issue with shame and guilt in Chinese seems particularly challenging, as research has found a rich lexicon of shame and guilt in Chinese.

Li et al. (Citation2004) collected 113 Chinese terms related with shame, both descriptively and associatively, using a Chinese dictionary and native Chinese respondents, while another group of Chinese respondents sorted the terms based on similarity. Two distinctive types of shame-related concept were identified through hierarchical cluster analysis: “self-focus” states including guilt and losing face, and “reactions to shame” (other-focused) including disgrace, shamelessness and embarrassment. However, many proverbs and figures of speech that were not descriptive words for shame were included, so their findings might not generalise to a more straightforward lexicon. Using a qualitative method, Bedford (Citation2004) interviewed 34 Taiwanese women about their experiences of shame and guilt starting from the English words, and revealed three Chinese terms for guilt (nei jiu, zui e gan and fan zui gan) and four for shame (diu lian, can kui, xiu kui and xiu chi), all distinctive in their profiles of elicitors and affective experience.

Bedford’s (Citation2004) findings have greatly influenced later research on shame and guilt in Chinese, but it is still not clear whether a systematic, quantitative investigation of the Chinese terms would confirm her results. Frank et al. (Citation2000) wrote nine scenarios that captured the five forms of shame in Chinese culture identified by Bedford (Citation1994) and asked American participants to rate them on 28 cognitive, motivational, and affective qualities. They found that Americans could distinguish the five forms of shame, despite a lack of English vocabulary reflecting the differences. But because neither the scenarios nor the affect descriptors were validated among Chinese speakers, the correspondence between the scenarios and the forms of shame were not established. Zhuang and Bresnahan (Citation2017) presented Chinese and American participants shame- or guilt-eliciting scenarios where relational closeness and targets of harm (self vs. other) were manipulated, and measured the two emotions with several scaled descriptors initially developed in English such as “I would feel inwardly troubled” or “I would be blushing”. They also included an open-ended question for which answers were coded consulting Bedford (Citation2004). This approach had a similar issue that both the scenarios and emotion descriptors were not generated or validated by Chinese participants. Moreover, their findings that the Chinese versus American participants freely reported more shame-related utterances and mixed feelings of shame and guilt also suggested the importance of precise understanding of Chinese terms related to shame and guilt.

Using the reference-based method but also focusing on emotion terms, Lin and Ng (Citation2012) selected five Chinese terms of shame (diu lian, xiu chi, chi ru, nan wei qing and gan ga) from 12 Chinese speakers’ free emotional responses to shame-eliciting scenarios from Ogarkova et al. (Citation2012) and let another sample of 32 Chinese speakers rate the five terms on 21 self-other features such as presence of others, social class of the other, and impact on oneself/others. Analyses of ratings of these features yielded three clusters of emotions (xiu chi and chi ru; nan wei qing and gan ga; and diu lian alone). While this approach in general was similar to our first study, the researchers intentionally deleted guilt-related terms such as xiu kui and can kui. It also did not try to confirm whether terms were used distinctively when participants started from different situations.

Despite these lexical studies of shame and guilt in Chinese, much cross-cultural research has assumed that Chinese translations of “shame” and “guilt” have similar meaning to English. For example, Gao et al. (Citation2010) studied both Chinese and American emotional responses to self- or other-inflicted scenarios, using xiu chi as the equivalent to shame and nei jiu to guilt. Other studies have mentioned that shame/guilt was measured with one scaled item in each language, but not specifying the Chinese term (e.g. Seiter & Bruschke, Citation2007; Tang et al., Citation2008). Likewise, in recent neuroscience research on shame and/or guilt conducted on Chinese participants and published in English, exact Chinese terms used in verbal measures of emotions were not reported (Yu et al., Citation2020; Zhu et al., Citation2019). It is likely that these studies also used xiu chi and/or nei jiu, a convention following pioneering quantitative research on shame and guilt in mainland China by Qian and colleagues. Comparing the emotions of xiu chi and nei jiu, they found that xiu chi versus nei jiu was more painful, more associated with public exposure, personal inadequacy but not moral violation, and withdrawal tendencies, similar with findings in English (Qian et al., Citation2000; Qian & Qi, Citation2002; Xie & Qian, Citation2000).

Nonetheless, the typical social inputs and outcomes of xiu chi and nei jiu may be different from other Chinese terms translated as “shame” and “guilt”, as previous studies suggested (e.g. Bedford, Citation2004). Surprisingly, we could not find any quantitative research that examines whether the Chinese words translated as the same English term show convergence or divergence in their social-functional characteristics, nearly three decades after Bedford's research (Citation1994). We also could not find any studies that directly addresses the equivalence of terms of shame and guilt in Chinese and English. For this reason, a quantitative study comparing the major social-functional features of the Chinese words translated as “shame” or “guilt” and with their English counterparts would be crucial for future research on the two emotions, both in Chinese culture and cross-culturally.

The present studies

The present research carried out a systematic investigation of Chinese speakers’ associations between dictionary-translated Chinese terms of “shame” and “guilt” and social appraisals and motivations, testing whether the Chinese translations are equivalent to English “shame” and “guilt” in terms of their social-functional characteristics. We first quantitatively identified eight relatively frequent terms in Chinese translated as “guilt” and “shame”. In Study 1, we asked native Chinese speakers to rate the terms on four social dimensions proposed to distinguish between guilt and shame in English, and on intensity and action tendencies. This would allow us to outline each emotion term’s social-functional profile and to test hypotheses about whether, individually and as a whole, they are conceptually close to the social meanings attributed to English shame and guilt. In Study 2, we reversed direction to test whether the Chinese terms could be reliably produced from eight eliciting scenarios built on the results of Study 1 by a different Chinese sample. A sample of native English-speakers was also included to examine appropriateness of English terms to the scenarios and compare motivational tendencies across samples.

Lexicon selection

We used systematic methods to find the most common terms translated as “shame” and “guilt” in Chinese. First, we consulted the Oxford Chinese Dictionary (Kleeman & Yu, Citation2010), Collins online dictionary (Collins Dictionary, Citationn.d.), and Cambridge online dictionary (Cambridge Dictionary, Citationn.d.) to find Chinese words translated as “shame” and “guilt”. The adjectives, “ashamed” and “guilty”, were also included in our searching. The non-emotion meanings “disappointing or not satisfactory” for shame and “having done something wrong or committed a crime” for guilt were excluded. Nine Chinese terms were identified: xiu kui (羞愧), chi ru (耻辱)Footnote1, can kui (惭愧), xiu chi (羞耻), diu lian (丢脸) and bu hao yi si/nan wei qing (不好意思, 难为情; referred to as bu hao yi si for short) which were translated into English as “shame,” and nei jiu (内疚), kui jiu (愧疚) and zi ze (自责) as “guilt”. We also searched for additional terms including the characters xiu (羞, ashamed), jiu (疚, remorseful), kui (愧, ashamed), can (惭, ashamed) and chi (耻, shame) which reoccur in these translations within the Oxford Chinese Dictionary (Kleeman & Yu, Citation2010) and the Leiden Weibo Corpus (LWC, van Esch, Citationn.d.).Footnote2

Secondly, using the same list of single characters, we referred to the China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI, Citation2021), the most comprehensive online publishing platform in mainland China, to search Chinese-language journal articles in psychology. Among the 368 psychology articles retrieved, most of them used the emotion terms xiu chi to discuss shame and nei jiu for guilt. However, this search did not turn up any additional terms used in Chinese psychological research that had the meaning of self-conscious reactions to a fault.

The LWC further allowed us to derive frequencies of terms in colloquial use, as opposed to printed lexicons which might overrepresent literary or academic language. The reason for selecting terms based on their frequency was to focus on terms that could be clearly understood in self-report psychological research. Terms used more than once in a million words (bu hao yi si, diu lian, nei jiu, can kui, kui jiu, zi ze, xiu chi, xiu kui) were retained (see ). The LWC contains about 5000 words with frequency over 1 in a million, and 5000 is suggested as the extent of a working vocabulary for effective communication in Chinese (Chinese Testing International, Citation2018).

Table 1. Frequency of Chinese terms translated as “shame” or “guilt” in LWC.

Study 1

This study sought to establish the social-functional characteristics of the eight Chinese terms translated as “shame” or “guilt”. We had participants recall experiences prompted by each term. Bipolar-scaled questions measured four social dimensions of each experience: morality/competence concern, private/public setting, close/distant relations, and equal/hierarchical relations, to map out the Chinese terms’ social meaning against understandings of English “guilt” and “shame”. We also asked participants the intensity of each emotion, both in the emotional episode recalled and in general, because Western research has shown that shame versus guilt is experienced more intensely in specific contexts (Tangney & Dearing, Citation2002), and on a semantic level, different terms might have similar elicitors but different intensities (e.g. the English words “annoyed” and “furious” represent different intensities of anger). Finally, we included an open-ended measure of action tendencies evoked by each experience.

To test equivalence between the translations of the emotion terms in terms of their social meanings, we would compare the mean placement of each term on each social dimension to the midpoint. We hypothesised:

H1-1. The social meanings of Chinese translations of “shame” (bu hao yi si, can kui, diu lian, xiu chi, xiu kui) and “guilt” (nei jiu, kui jiu, zi ze) are similar to English “shame” and “guilt” respectively; that is, relative to the midpoint of the scale of each social dimension, Chinese translations of “shame” would be more inadequate, more public, and more relevant to distant and hierarchical relations, while Chinese translations of “guilt” would be more moral, more private, and more relevant to close and equal relations.

H1-2. The Chinese translations of “shame” (bu hao yi si, can kui, diu lian, xiu chi, xiu kui) would cluster as one category, and translations of “guilt” (nei jiu, kui jiu, zi ze) would cluster as another.

In addition, coding free-response action tendencies to each term allowed inspection of the assumption in Western psychology that guilt leads to reparation and shame to withdrawal (and sometimes, reparation as well). It also allowed us to explore whether Chinese terms translated as “shame” and “guilt” have positive implications not strongly identified in Western psychology, such as motivating self-reflection and self-cultivation (Mascolo et al., Citation2003; Wong & Tsai, Citation2007). By measuring each term’s motivational tendencies in addition to social characteristics and intensities, its social-functional profile could be revealed.

Method

Participants

We recruited 40 Chinese international students (25 female, 15 male, Mage = 23.73, SD = 2.40) from a university in England, screened so all participants had lived in China before age 17. A priori power analysis of the within-participants design indicates that a sample size of 34 participants could detect a medium effect size (Cohen’s d = .50) with an alpha = .05 and power = .80 for one-sample t-tests of mean difference from constant (mid-point of scales). The effect size was estimated from previous research on shame-guilt differences in social characteristics (Qian & Qi, Citation2002, Cohen’s d = 0.53; Smith et al., Citation2002, Study 2: Cohen’s d = 0.69, Study 4: Phi = 0.28 and Cohen’s d = 0.57, 1.25). Participants took part voluntarily and received a small reward.

Measures

The questionnaire was written in Chinese. For each term, participants were asked to rate the general intensity of feelings that the term represented on a 10-point scale from 1 to 10 (extremely intense), recall or imagine a situation in which they had felt these feelings and describe it, and rate how strong the feelings in that situation were on a 10-point scale (1 = the mildest to 10 = the most intense). They then evaluated the situation along four dimensions, each of which had two poles corresponding to social features of guilt (pole A) and shame (pole B). On a 5-point scale (1 = much more A to 5 = much more B), participants rated whether:

the event concerned participants’ A) morality or B) competence,

the event happened in A) private or B) public,

participants were close with the other(s) or B) the other person(s) was/were an acquaintance(s) or stranger(s),

the other person(s) was/were A) your peer(s) or equal to you or B) elders or your superior(s). To simplify this scale, we did not assess whether the other person was a subordinate, as the targeted sample was university students whose social interactions would mainly involve peers and superiors.

Lastly, they were asked to recall or imagine what action they felt or would feel like taking in response to that situation. As an initial check on the appropriateness of our word choices, we asked the first ten participants open-ended questions: which words were too similar to distinguish from the other(s), which were close but different, and what the differences were.

Results

Distinctiveness among Terms

Seven of the ten respondents who answered the similarity check reported that kui jiu and nei jiu were very similar. Three of these explained differences between the two, but with little agreement on the key difference. Given this inconsistent understanding, the eight terms were all kept in the questionnaire.

Intensity

The general and the situation-specific intensity of these terms relative to each other were similar. Bu hao yi si, can kui and diu lian had relatively low intensity (see ). Xiu chi was the most intense feeling, followed by xiu kui. The intensity of nei jiu, kui jiu and zi ze was moderate.

Table 2. Intensity of Chinese terms translated as “shame” or “guilt”, Study 1.

Social dimensions

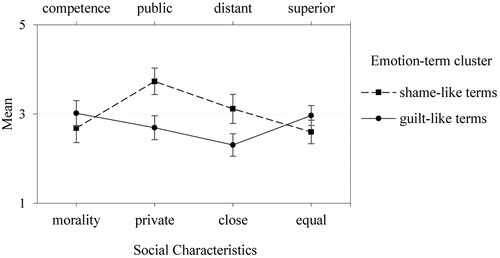

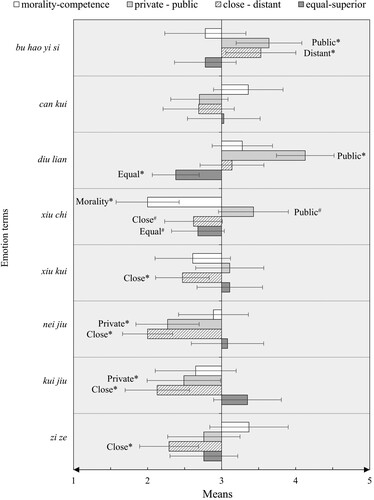

One-sample t-tests against the scale midpoint (3) examined the placement of each term’s elicitors on each social dimension (see ).

Figure 1. Social characteristics of eliciting situations of Chinese terms translated as “shame” or “guilt”, Study 1. Note. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. Bars on the two sides correspond to the two ends of social dimensions, e.g. white bars on the left and right sides indicate the terms’ morality and competence concern respectively. Text labels with * indicate significant differences (#: marginal significance) from the midpoint.

Competence/morality

Most elicitors did not clearly lean toward either end, except xiu chi which strongly favoured morality, t(38) = 4.60, p < .001, d = 0.74.

Public/private

Bu hao yi si (t(35) = 2.83, p = .008, d = 0.47) and diu lian (t(38) = 5.69, p < .001, d = 0.91) were more likely to be elicited in public, while nei jiu (t(36) = 3.35, p = .002, d = 0.55) and kui jiu (t(36) = 2.03, p = .05, d = 0.33) were more likely to be elicited in private.

Close/distant relations

Four terms including nei jiu (t(38) = −5.80, p < .001, d = 0.93), kui jiu (t(38) = −3.95, p < .001, d = 0.91), zi ze (t(37) = −3.50, p = .001, d = 0.63) and xiu kui (t(35) = −2.86, p = .007, d = 0.48) were more likely to be elicited in close relations than distant, while bu hao yi si was more associated with distant relations, t(37) = 2.19, p = .035, d = 0.36.

Equal/hierarchical relations

No terms were significantly associated with hierarchical relations, and only diu lian was judged as invovling equal relations, t(36) = 3.85, p < .001, d = 0.63.Footnote3

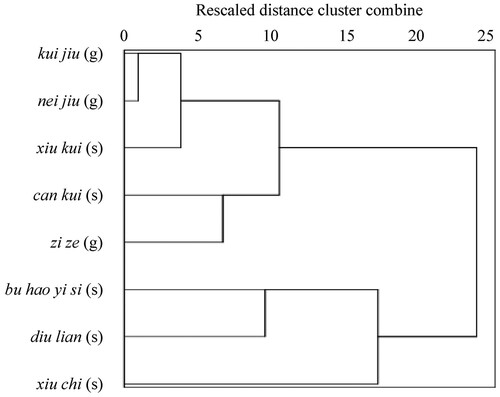

Hierarchical cluster analysis

Using the four scaled social characteristics plus the average of the two intensity measures as clustering variables, an agglomerative hierarchical cluster analysis explored the typology of the eight terms. Because there were few terms and we were simply interested in knowing their conceptual distances, we chose the “conservative” complete linkage method, which ensures each term “is more similar to all members of the same cluster than it is to all members of any other cluster” (Blashfield, Citation1976, p. 379; Blashfield & Aldenderfer, Citation1988). The analysis yielded two major clusters generally corresponding to dictionary-translated “shame” (bu hao yi si, diu lian, xiu chi) and “guilt” (kui jiu, nei jiu, xiu kui, can kui and zi ze), and within each there were subordinate groups or single terms (see ). Despite their translation as “ashamed” in dictionaries, can kui and xiu kui fell into the guilt cluster.

Figure 2. Dendrogram of eight emotion terms using complete linkage method, Study 1. Note. (s): dictionary-translation of “shame”; (g): dictionary-translation of “guilt”.

The mean intensity of the guilt cluster (M = 6.36, SD = 1.06) was higher than the shame cluster (M = 5.16, SD = 1.59), t(39) = 5.32, p < .001, d = 0.84, although the Pitman-Morgan test shows that the variation in intensity of the shame group was higher than the guilt group, t(38) = 2.98, p = .005. In terms of social characteristics, the shame cluster was more likely to be elicited in public compared with the guilt cluster (t(37) = 5.29, p < .001, d = 0.86), to involve socially distant others rather than close ones (t(36) = 3.75, p < .001, d = 0.62) and equal relations rather than hierarchical relations (t(36) = 2.56, p = .015, d = 0.42) (see ).

Action tendencies

Following Braun and Clarke's (Citation2006) guidelines of thematic analysis, one of the researchers familiarised themselves with all reported action tendencies and generated some initial categories (original data available at https://osf.io/ge8tx/). Referring to each reported tendency, these categories were then reviewed to check their internal coherence and distinctiveness from each other. Five themes were generated.

Withdrawal: avoid other people or withdraw from the situation.

Reparation: appease the offended other(s). Examples are apologising, being polite, showing modesty, and offering compensation.

Self-improvement: stop wrong actions and do the right thing. Unlike reparation, this objective aimed to improve one’s own competence or moral character, rather than to repair a specific relationship or wrong.

Cognitive coping: change thoughts about the event, seek distraction, or reflect on oneself.

Self-assertiveness: defend oneself by arguing, explaining the rightness of one’s own behaviours, or retaliation.

Based on a written scheme (available at https://osf.io/ge8tx/), two Chinese native-speaking psychology postgraduate students coded these responses independently. For each response, each theme was coded zero if absent and one if present. The coders’ agreement was generally high with Cohen’s κ ranging from .66 to 1.00 and agreement ranging from 91% to 100%. Disagreements were resolved by discussion.

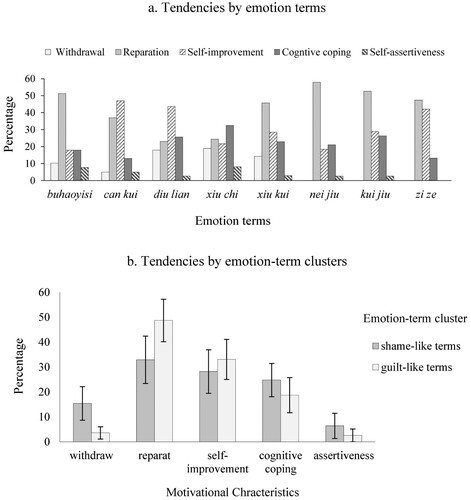

Cochran's Q test showed significant differences among the eight terms in the frequency of withdrawal (χ2(7) = 23.44, p = .001), reparation (χ2(7) = 19.63, p = .006) and self-improvement (χ2(7) = 15.04, p = .036). There was no difference in cognitive coping (χ2(7) = 7.23, p = .41) and self-assertiveness (χ2(7) = 4.51, p = .72). As shown in a, reparation was the most prevalent tendency when participants felt bu hao yi si (51.28%), nei jiu (57.89%), kui jiu (52.63%) and zi ze (47.37%). Withdrawal was not often chosen but most often occurred in diu lian (17.95%) and xiu chi (18.92%). Self-improvement was the most common tendency when people felt can kui (47.00%) and diu lian (43.59%) and the second most common for zi ze (42.11%). Cognitive coping was also commonly chosen but was only most frequent in xiu chi (32.43%). Being self-assertive was very rare.

Figure 4. Frequency of five tendencies for Chinese shame and guilt terms, Study 1. Note. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

Based on results of the cluster analysis, the two emotion categories significantly differed on two motivational tendencies; the shame-like cluster drove people to withdraw more than guilt, t(38) = 3.74, p < .001, d = 0.60, while guilt-like cluster motivated appeasement more, t(38) = 3.57, p < .001, d = 0.57 (see b).

Discussion

The hypothesis H1-1 was partly supported; some of the Chinese terms showed similar characteristics to their English translation as we expected. Similar to Western guilt concepts, the terms translated as “guilt”, nei jiu and kui jiu, were more often experienced in private, in close relations, and more likely to motivate reparation instead of withdrawal. Among the terms translated as “shame”, xiu chi was the closest to the Western shame concept due to its high-intensity, public, and withdrawal nature. Compared with xiu chi or “shame” in English, bu hao yi si and diu lian were also public, but less intense and predominantly associated with different action tendencies such as reparation and self-improvement. However, some terms showed different characteristics from their English translations. Despite the dictionary translation of “shame”, the term xiu kui was a more private feeling and more other-oriented, and the term can kui was also felt mainly in private situations and motivated self-improvement instead of withdrawal. The guilt-translated term zi ze had a greater focus on competence rather than the moral faults of other guilt-like terms (nei jiu, kui jiu), and motivated self-improvement instead of reparation. These nuances are not completely captured in the commonly understood meaning of English “shame” or “guilt”.

The two major categories suggested by the cluster analysis of the Chinese terms generally supported H1-2. In line with their dictionary translation, most terms clustered within the expected shame-like (bu hao yi si, diu lian, xiu chi) or guilt-like (kui jiu, nei jiu, zi ze) category, except can kui and xiu kui which were translated as “shame” but fell into the guilt-like cluster.

Furthermore, the motivational processes of shame-eliciting events among Chinese respondents showed differences from previous Western findings. To hide or escape was not a dominant response to shame-like emotions such as diu lian and xiu chi. Instead, tendencies of self-improvement and cognitive coping were found more frequently, in line with theory about the link between shame and self-cultivation in Chinese culture (e.g. Mascolo et al., Citation2003).

Profiles of the Chinese terms

Beyond showing broad correspondence between the Chinese terms and their English translation in social meaning, the study also helped build each Chinese term’s social-functional profile.

Bu hao yi si, usually translated “shame,” was mildest. Its typical elicitor was doing something inappropriate in public among strangers or acquaintances, with reparative actions most likely. Due to these characteristics, bu hao yi si may be more similar to embarrassment than shame in English (Keltner, Citation1996; Miller & Tangney, Citation1994; Tangney et al., Citation1996).

Can kui was a mild term without a strong tendency towards the endpoints of any social dimension, suggesting that it did not fit the usual Western “shame-guilt” distinctions. It tended slightly to be experienced in private, and strongly motivated self-improvement and reparation. Although Bedford (Citation2004) qualitatively analysed can kui in terms of failing to attain one’s ideal state, inferiority in social comparisons also appeared in nine of the 39 elicitors of can kui (e.g. “seeing my classmates working hard while I’m playing video games”). Despite its usual translation as “shame” and its greater self- rather than relationship-focus, can kui also had guilt-like aspects, specifically its private nature and approach tendency.

Diu lian, literally translated as “losing face”, was moderately intense and clearly associated with public exposure. It was evoked by failure in public, especially in front of peers. Striving to improve performance was the most likely response, similar to can kui, followed by withdrawal. In accordance with Bedford (Citation2004) and Lau et al (1997; as cited in Ho et al., Citation2004), we did not find that diu lian was highly painful, maybe because it is less reputation-focused nowadays than it traditionally was.

Xiu chi was the most intense shame-like term and primarily concerned one’s moral reputation. People felt xiu chi when they had done something deeply immoral, similar to strong usages of “shame” in English. Beyond the action tendencies of avoidance or self-banishment suggested in Bedford (Citation2004), we also found reparation, self-improvement, and cognitive coping as common responses to xiu chi.

Sharing some characteristics with xiu chi, xiu kui was also intense, but less moral and more likely to promote reparation in a relation. Bedford (Citation2004, p. 40) found that the main cause of xiu kui is “violation of a self-expectation that results in harm to others”, and the element of harming others might be the reason why xiu kui clustered more closely with guilt-like terms in our analysis, although both dictionaries and Bedford (Citation2004) suggest that xiu kui corresponds to “shame”.

Nei jiu and kui jiu were two emotions with relatively high intensity and a guilt-like profile; respondents identified these terms to doing something wrong in private that negatively affected family or close friends (Baumeister, Reis, et al., Citation1995; Baumeister, Stillwell, et al., Citation1995). Bedford (Citation2004) also suggested that nei jiu is a form of social guilt caused by failing one’s responsibility to another person, implying close relations. Repairing the relation was the most likely response. As a minor difference, people used kui jiu more often than nei jiu towards superiors such as parents.

Zi ze was another intense feeling, usually translated as “guilt” but not identified in Bedford (Citation2004). Arising in private, it usually involved a close social relation as did nei jiu and kui jiu but was more likely to be caused by a competence fault, so did not completely correspond to the Western social profile of “guilt”. Zi ze had a strong element of self-improvement in addition to reparation, in line with its literal meaning, self-blame.

Study 2

Although Study 1 revealed distinctive social features within the Chinese translations of “guilt” and “shame”, it remained to be seen whether each term’s common eliciting event with these social features would reliably produce that term more than others. This is a further step that can validate the distinctiveness of the terms’ social characteristics but has rarely been taken in emotion lexical research.

In Study 2, eight eliciting scenarios were constructed using each term’s social characteristics, in order to test how Chinese speakers would use the eight emotion terms in response to the eliciting scenarios. If the social characteristics of each Chinese term identified in Study 1 were strongly distinct, we should be able to observe one-to-one scenario-term correspondences, that is, in response to the eliciting scenario that explicitly depicted the corresponding term’s social characteristics, Chinese participants should be more likely to endorse the corresponding term than others. But considering that some of the Chinese terms showed similar profiles and some characteristics used to construct the scenarios were exaggerated (non-significant, only suggestive in Study 1), this assumption about one-to-one scenario-term correspondences might be too restrictive. Also, research in European languages sometimes finds confusion between shame and guilt when producing terms to describe situations (e.g. Ogarkova et al., Citation2012; Tangney et al., Citation1996). However, if the two shame-like and guilt-like term clusters generated from Study 1 were indeed reliable and meaningful emotion categories, at least we should be able to observe larger-scale correspondences between the two categories of scenarios and terms. More specifically, we hypothesised:

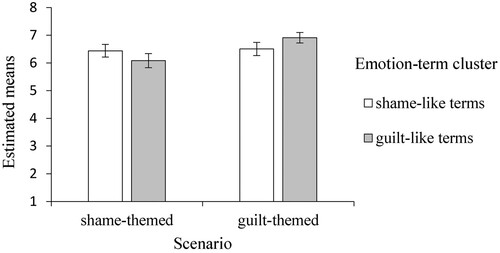

H2-1. For the Chinese term-production task, when dividing the emotion terms and their corresponding elicitor situations into two categories based on the two clusters of shame-like and guilt-like terms shown in Study 1’s cluster analysis, shame-themed scenarios would be described with higher endorsement of shame-like terms than guilt-like terms, and guilt-themed scenarios would be described with higher endorsement of guilt-like terms than shame-like terms.

H2-2. For English word use among English-speaking participants, shame was expected to predominate in scenarios of diu lian and xiu chi, guilt in the scenarios of nei jiu and kui jiu, embarrassment in the scenario of bu hao yi si.

Although some motivational tendencies reported by Chinese participants in Study 1 have received little attention in previous research on shame and guilt in English, whether these tendencies are culturally unique remains a question. Therefore, we tested whether two cultural groups would associate the measured emotions of shame and guilt with different motivational tendencies in response to the scenarios, using measures of the five types of tendencies reported in Study 1. We expected that:

H2-3. Own-language measures of guilt would predict reparation motives similarly in the two cultures, whereas measures of shame would predict different motives. Specifically, for Chinese participants, shame would predict motives such as self-improvement and cognitive coping, while for British participants, shame would predict primarily withdrawal motives.

To allow for meaningful comparisons of the emotions’ motivational tendencies, the emotion terms in the two languages should be equivalent as far as possible (we hypothesised the equivalence in H2-2). Depending on British participants’ actual term use, we would first select Chinese terms that parallel English shame, guilt and embarrassment (as a covariate) to test H2-3.

Method

Participants

Eighty-five Chinese (52 women, Mage = 28.73, SD = 9.41) and 83 British participants (58 women, Mage = 31.74, SD = 14.22) who had lived in their home country before age 16 were recruited online using volunteer snowball sampling. Sensitivity power analysis indicated that this sample size could detect a medium to large effect size (f = .31 for the Chinese sample who had 2 within-subjects emotion term clusters and .25 for the British who had 3 within-subjects terms) with power of .80 in repeated-measures ANOVA tests.

Materials

Eight scenarios corresponding to the eight emotion terms were constructed, using data on their characteristics from Study 1 (). We started with a basic description of a morality- or competence-related fault in each scenario based on whether the term was significantly more related to morality or competence. Because all scenarios needed to describe a transgression in some way, for terms that did not show significant difference from the midpoint of the morality/competence dimension, we still describe the transgression as morality- or competence-related in their scenarios based on which side of this dimension the term’s mean score fell into. We then added descriptions of each term’s other social characteristics whose scores were significantly different from the midpoint (e.g. public/private, superior/equal, distant/close). Lastly, we added descriptions of intensity for the lowest and highest-rated terms by adding mildly in the scenario of bu hao yi si and deeply in the scenario of xiu chi, and in two cases followed nonsignificant differences to further distinguish terms. “Superior” was added for the kui jiu scenario, as it was the only characteristic found in Study 1 that might distinguish it from nei jiu; “private” was added to the can kui scenario to separate it from the scenario of diu lian.

Table 3. Eight scenarios constructed based on eight terms’ characteristics, Study 2.

Measures

After each scenario, participants rated each emotion on an eight-point scale (1 = not at all likely to 8 = extremely likely): eight Chinese terms for Chinese participants, and three English terms, embarrassment, shame, and guilt for British participants. They then rated the likelihood of five motivational tendencies (11 items) on the same scale, including withdrawal (withdraw from the situation; avoid other people, Spearman’s ρ = .89/.81 for Chinese/British), reparation (apologise; compensate to other people; Spearman’s ρ = .71/.67), self-improvement (improve performance; improve the self; self-reflection, α = .85/.85)Footnote4, cognitive coping (divert attention; change thoughts, Spearman’s ρ = .51/.47) and self-assertiveness (defend the self; retaliate, Spearman’s ρ = . 40 and .47 ).Footnote5 It is worth noting that measures of the last two tendencies showed lower reliability and this should be taken into account when interpreting the results.

The questionnaire was first designed in English. We had two Chinese translators who majored in English, one translating the original questionnaire into Chinese, and the other translating the Chinese version back into English. Ambiguous and incongruent wordings in this back-translation were revised on agreement of both translators.

Results

Scenario-emotion correspondences

The emotion terms were applied broadly, with Scenarios 4–8 (scenarios of xiu chi, xiu kui, nei jiu, kui jiu, and zi ze) eliciting mean ratings in the top quarter of the scale (between 6 and 8) for all terms. No term apart from bu hao yi si was endorsed significantly more than all other terms for its corresponding scenario (more details see Supplement, “Scenario-Term Correspondences, Study 2”).

We then tested whether the broad distinctions of shame-like and guilt-like categories were followed in use of terms, that is, larger-scale correspondences between shame-/guilt-themed scenarios and shame-like/guilt-like terms. Based on Study 1’s cluster analysis, we divided the eight scenarios into two themes, the corresponding scenarios of bu hao yi si, diu lian and xiu chi as shame-themed scenarios and the corresponding scenarios of other five terms as guilt-themed scenarios. We then calculated aggregated scores of the two clusters of emotion terms in the two types of scenarios in two steps. Firstly, ratings of bu hao yi si, diu lian and xiu chi in each scenario were averaged to derive means of the shame-like terms and ratings of the other five terms averaged to derive means of the guilt-like terms at the scenario level. We then averaged the scenario-level means of shame-like terms and guilt-like terms respectively, both in the three shame-themed scenarios and five guilt-themed scenarios.

One-way repeated-measure ANOVA was conducted, with types of scenarios (shame-themed vs guilt-themed) entered as a within-subject factor and aggregated scores of two emotion-term clusters (shame-like terms vs guilt-like terms) as repeated measures to see whether two themes of scenarios would produce differential use of terms (H2-1). The main effect of emotion-term clusters was not significant, F(1, 84) = .21, p = .65, ηp2 = .002, but the main effect of scenarios was significant, F(1, 84) = 32.65, p < .001, ηp2 = .28; emotions overall scored higher in guilt-themed scenarios versus shame-themed scenarios. More importantly, there was a significant interaction between scenarios and term clusters; F(1, 84) = 54.50, p < .001, ηp2 = .39 (see ). The guilt-like term cluster scored higher than the shame-like term cluster in guilt-themed scenarios (F(1, 84) = 31.65, p < .001, ηp2 = .27), and the opposite was found in in shame-themed scenarios (F(1, 84) = 21.61, p < .001, ηp2 = .21), supporting H2-1.

Application of English-language emotional terms

Repeated-measures ANOVA were carried out for each scenario to examine British participants’ emotion term use (H2-2). For two of the embarrassment- or shame-related scenarios of bu hao yi si (S1) and diu lian (S3), scores of the three English terms were significantly different (S1: F(2, 164) = 118.27, p < .001, ηp2 = .59, S3: F(1.77, 144.72) = 78.331, p < .001, ηp2 = .49). Post-hoc comparisons with Sidak adjustment showed significant differences between each pair (ps < .001), with embarrassment highest, followed by shame and then guilt. For the scenario of xiu chi, there was no significant difference among the three English terms, F(1.41, 115.36) = 2.50, p = .10, ηp2 = .03, but pairwise comparisons suggested higher shame than guilt (p = .02). For the two focal guilt scenarios (S6 nei jiu and S7 kui jiu), British participants rated the three terms differently (S6: F(1.41, 115.73) = 21.34, p < .001, ηp2 = .21; S7: F(1.44, 113.49) = 33.14, p < .001, ηp2 = .30); pairwise comparisons showed that guilt was rated significantly higher than shame (ps < .05), and shame higher than embarrassment (ps < .001) for both scenarios. In general, H2-2 was mostly supported except that embarrassment, instead of shame, was most prevalent in the scenario of diu lian.

For the scenarios of can kui (S2), xiu kui (S5), and zi ze (S8) that we did not have specific prediction, the three English terms were also rated differently (S2: F(2, 164) = 9.35, p < .001, ηp2 = .10; S5: F(1.62, 132.77) = 32.54, p < .001, ηp2 = .28); S8: F(2, 158) = 7.37, p = .001, ηp2 = .09). Similar post-hoc comparisons showed that in S2 embarrassment and shame scored higher than guilt (ps < .01), in S5 guilt scored significantly higher than shame (p = .005), and shame higher than embarrassment (p < .001), and in S8 embarrassment scored higher than shame and guilt (ps < .05).

Motivational tendencies

Both samples reported medium to high likelihood (Ms > 5) of most motivational tendencies except self-assertiveness which showed very low means (See Supplement).Footnote6 As self-assertiveness was not positively correlated with scores of any Chinese or English emotion terms (See Supplement, Table S3), it was excluded from further analyses. To test whether the emotions were associated with the four motivational tendencies differently between the two cultural groups (H2-3), we conducted linear mixed model analyses for each sample separately in R, using the package lme4 (Bates et al., Citation2015). The three emotions of embarrassment, shame and guilt (or parallel Chinese terms) were entered as fixed-effect factors in each model, the four tendencies as outcome variables in separate analyses, and intercept for subjects as random effects. According to the Chinese terms’ social characteristics and British participants’ term use examined above, xiu chi was selected as the parallel to “shame”, and ratings of nei jiu and kui jiu were averaged to form a composite index that parallels to “guilt”, due to their similar profiles and high correlations across scenarios (r = .90). Because British participants’ mean rating of “embarrassment” in the scenario of diu lian was not only highest among the three English terms, but also higher than its score in the scenario of bu hao yi si, we selected diu lian as the parallel to “embarrassment”, instead of the colloquial term bu hao yi si which had general high ratings across scenarios.

As shown in , diu lian and xiu chi were significant positive predictors of withdrawal for Chinese, and so were embarrassment and shame for British participants. The emotion of guilt (nei jiu/kui jiu) negatively predicted withdrawal among Chinese participants but not British. The reparation tendency including to apologise and compensate was positively predicted by the emotion of guilt in both samples. Whereas xiu chi positively predicted reparation for Chinese participants, we did not find similar results for shame among British participants; instead, only embarrassment positively predicted reparation. For both samples, all three emotions positively predicted self-improvement, with guilt being the strongest predictor. Cognitive coping such as diverting attention and changing thoughts were negatively predicted by guilt in both groups. Nonetheless, Chinese participants were also more likely to use cognitive strategies when feeling diu lian, but for British participants neither embarrassment or shame was a significant predictor of this tendency.

Table 4. Mixed model analyses of comparable emotions predicting motivational tendencies, Study 2.

Discussion

The eight Chinese terms translated as “shame” or “guilt” had broad applicability across scenarios, showing that a common elicitor of a term is not necessary its only elicitor. This might be because that people often use terms imprecisely as long as the general meaning can be understood, analogous to fuzzy usage of colour terms (Berlin & Kay, Citation1991). Another reason why the scenarios did not produce their corresponding terms exclusively might be that some social characteristics used to construct the scenarios were exaggerated. Similarly, the differences between shame and guilt on the four social dimensions used in Study 1 were also exaggerated for the purpose of examining the terms’ social characteristics. However, larger-scale correspondences between guilt-themed/shame-themed scenarios and shame-like/guilt-like term clusters were found, supporting H2-1. This suggested that the two clusters of terms generated from Study 1 were reliable and meaningful emotion categories.

In addition to Study 1’s findings that the term xiu chi had very similar social characteristics with shame, and nei jiu and kui jiu with guilt, we found that British participants also reported the highest likelihood of feeling shame in the scenario of xiu chi and guilt in the scenarios of nei jiu and kui jiu, suggesting equivalence between these terms in two languages. The emotional language of private incompetence in Chinese, however, might not be captured by “shame” or “guilt” in English. Recognising one’s inadequacy privately was not associated predominantly with shame or guilt for British but was associated with emotions such as can kui and zi ze for Chinese.

In line with findings among Western cultures (e.g. Baumeister, Stillwell, et al., Citation1995; Tangney & Dearing, Citation2002), we found clear association between shame and the withdrawal tendency as well as between guilt and reparation for both Chinese and British. The adaptive functions of shame, including self-reflection and self-improvement (e.g. de Hooge et al., Citation2008; Gausel & Leach, Citation2011), were also found in both samples. However, the reparation tendency was positively linked to shame for Chinese (xiu chi), but not for British participants. Moreover, Chinese seemed more likely than British to use cognitive strategies to cope with their feeling of diu lian (vs. embarrassment). However, more evidence is needed to draw this conclusion, partly due to relatively low reliability of the cognitive coping measures. Further investigation may benefit from considering what cognitive strategies people use to regulate their emotions of shame or guilt (e.g. reappraisal as an emotion regulation strategy, see Gross & John, Citation2003), and whether people from different cultures tend to regulate negative self-conscious emotions differently (e.g. see Matsumoto et al., Citation2008).

General discussion

Practical and theoretical implications

There has been criticism that imprecise emotion term usage causes problems for verbal measurements of emotions (e.g. Weidman et al., Citation2017), and that folk emotion words such as “shame” are not suitable for scientific inquiry (Fiske, Citation2020; Kollareth et al., Citation2019), let alone the problematic translation of emotion terms in cross-language research (Wierzbicka, Citation1999). Researchers have suggested various ways to avoid untechnical emotion terms, such as defining emotion concepts in universal “semantic primitives” (Wierzbicka, Citation1992), focusing on fundamental psychological aspects of emotions but not terms (Kollareth et al., Citation2019), or coining new technical names for emotion constructs (Fiske, Citation2020). Nevertheless, we believe emotion terms in natural languages inform us about lay conceptualisation of emotions, so that emotion terms remain an informative tool for cross-cultural research.

By examining the social-functional characteristics of eight Chinese emotion terms that translated as “shame” or “guilt”, we found that some words translated “shame” had more complexity in psychological meaning than dictionaries might indicate. The shame-translated Chinese words differed in their intensity, morality/competence concern and self-/other-oriented motivational tendencies. For example, can kui, although translated as “shame”, was associated with private situations of incompetence and self-focus instead of other-focus, and its common elicitor did not produce a preponderance of “shame” or “guilt” responses by the British. Nonetheless, British participants’ similar emotional responses to those scenarios which had similar social characteristics of English “shame” or “guilt” suggested equivalence between some emotion terms in the two languages. Namely, xiu chi parallels “shame”, and kui jiu and nei jiu parallel “guilt”.

The two cultural groups also nominated similar action tendencies across scenarios, despite some differences such as lower endorsement of cognitive coping by the British participants. Cognitive-coping responses to shame, which have received little attention in Western-origin literature, were revealed in Study 1’s thematic analysis and associated with the emotion of diu lian for Chinese in Study 2. Self-improvement responses were positively predicted by guilt in both samples, suggesting that this heretofore neglected tendency (relative to the well-studied tendency of reparation) provided by Study 1’s Chinese sample might be profitably studied further outside of China.

Moreover, we provided a different approach to studying emotion terms’ equivalence between languages. Previous cross-linguistic research into emotion terms has usually used either the translation method that starts with emotion terms and finds their semantic differences, or the mapping method that starts with contexts or expressions and finds out which emotion terms accompany them (Boster, Citation2005; Ogarkova et al., Citation2012). We cross-referenced the two methods, by starting with the translation method in Study 1 to find the social characteristics of the emotion terms and using the mapping method in Study 2 to test whether these characteristics were distinctive enough to produce corresponding emotion terms. This allowed us to explore the distinction in specific emotion terms, but also the general tendency of guilt-like and shame-like terms to be produced from associated situations, as assuming a one-to-one mapping of many of these terms could be problematic (Cowen & Keltner, Citation2021; Gray et al., Citation2017).

Limitations and future research

The two studies had limitations. Firstly, Study 1 only measured four social appraisals and action tendencies, leaving other components of emotions such as subjective feelings, expressions, and regulation unexplored. A multi-component approach, such as the GRID method which operationalised six major components of emotions, may allow for more comprehensive investigation (Fontaine & Breugelmans, Citation2021). Secondly, we measured the morality-competence dimension with a bipolar, continuum scale, similar to our measurement of the other three dimensions, because the morality-competence distinction has been commonly used to distinguish the emotions of shame and guilt (e.g. Qian & Qi, Citation2002; van der Lee et al., Citation2016). But shame could be elicited by both one’s transgressions and incompetence (e.g. Smith et al., Citation2002; Tangney et al., Citation1996), and at times the two may not be completely exclusive (e.g. when personal incompetence harms someone), making it difficult to interpret the scores of this dimension. Separating this dimension to two may allow for more precise understanding of the two emotions. Lastly, participants in Study 1 were Chinese university students studying in England. As opposed to the online Chinese samples collected in Study 2, they might be more exposed to Western culture, which could lead to some different results in the two studies. However, because the UK-based Chinese students had lived in China before age 17, their base experience could be considered roughly similar.

It is worth noting that the four social dimensions derived from existing Western research could have overlooked characteristics prevalent in Chinese but not Western culture. For example, filial obligation to parents was frequently reported in Study 1, but our two social-relation dimensions could not distinguish filial relations from other close relations. Developing a list of dimensions that captures the two emotions’ culturally specific characteristics would be useful for more nuanced examination. On the other hand, if synonyms and near-synonyms for “guilt” and “shame” such as “remorse,” “humiliation,” and “mortification” were included in our investigation, other dimensions of self-conscious emotions might also be found in English. Therefore, it is important to keep in mind that the current research was not comparing the constructs of shame and guilt between the Chinese and Western cultures, and the scope of our studies was bounded by the translated terms selected and examined.

To study the constructs of negative self-conscious emotions in Chinese culture, different approaches are needed. A bottom-up approach from Chinese emotion lexicon, as advocated by the indigenous psychologies approach (Kim et al., Citation2000), would be useful to disclose structures and concepts of the emotions. For example, Shaver et al. (Citation1992) found that the term xiu qie (羞怯, diffident), clustering with several other terms usually translated as “shame” such as xiu kui, xiu chi and can kui, formed an emotion cluster not found in English or Italian, although it was usually translated as “timid” (Collins Dictionary, Citationn.d.). Our search of psychological articles on Chinese emotion terms that consist of the character xiu in CNKI (Citation2021) also showed research on xiu qie made up a large percent of the retrieved literature. Whether this is indeed a culturally distinctive concept of shame in Chinese culture might be worth studying.

In conclusion, the two studies examined comparability between Chinese translations of “shame” of “guilt” and their English counterparts; some Chinese terms shared very similar social-functional characteristics with their English translations, but some showed more complexities. Although different social characteristics of Chinese terms were not precisely reconstructed when participants chose words to express reactions to associated elicitors, vocabulary choice in Chinese followed the larger shame-like and guilt-like clusters we identified. The research also suggests a cross-referencing approach to validating emotion terms’ characteristics and establishing equivalence between emotion terms in different languages.

Supplement__revision3_.docx

Download MS Word (83.3 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available at https://osf.io/ge8tx/.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Chi ru (耻辱, disgrace, humiliation) was excluded in our investigation, as we found in the Leiden Weibo Corpus it was mostly used to describe the state of being humiliated.

2 LWC consists of 5,103,566 messages posted in January 2012 on Sina Weibo which is China's most popular Twitter-like microblogging service.

3 Most situations involved interpersonal relations, except zi ze. Eight out of 39 elicitors of zi ze did not specify any other person and had similar themes: Respondents did something incompetent either by commission or omission.

4 The self-reflection item was intended to measure cognitive tendency, but for both cultural groups, it had lower correlation with the two items of cognitive coping (rs ranging from –.11 to .11) than with items of self-improvement. Therefore, we moved self-reflection into the category of self-improvement.

5 We also asked one question about whether their feelings involved more negative appraisals of their behaviour or of the self, to assess Tangney's influential view of shame and guilt (e.g., Tangney & Dearing, Citation2002). Results of this non-social appraisal were reported in Supplement (“Comparisons of Action-Self Appraisals, Study 2”).

6 In the Supplement (Comparisons of Motivational Tendencies, Study 2), we also reported independent-samples t-tests of motivational tendencies for each scenario with both raw scores and scores after within-subject standardisation, to address potential cultural differences in response bias.

References

- Bates, D., Mächler, M., Bolker, B. M., & Walker, S. C. (2015). Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software, 67(1), 1–48. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v067.i01

- Baumeister, R. F., Reis, H. T., & Delespaul, P. A. E. G. (1995). Subjective and experiential correlates of guilt in daily life. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 21(12), 1256–1268. https://doi.org/10.1177/01461672952112002

- Baumeister, R. F., Stillwell, A. M., & Heatherton, T. F. (1994). Guilt: An interpersonal approach. Psychological Bulletin, 115(2), 243–267. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.115.2.243

- Baumeister, R. F., Stillwell, A. M., & Heatherton, T. F. (1995). Personal narratives about guilt: role in action control and interpersonal relationships. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 17(1–2), 173–198. https://doi.org/10.1080/01973533.1995.9646138

- Bedford, O. A. (1994). Guilt and shame in American and Chinese culture (Publication No. 9506309). [Doctoral dissertation, University of Colorado at Boulder]. ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global.

- Bedford, O. A. (2004). The individual experience of guilt and shame in Chinese culture. Culture and Psychology, 10(1), 29–52. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354067X04040929

- Berlin, B., & Kay, P. (1991). Basic color terms: Their universality and evolution. Univ of California Press.

- Blashfield, R. K. (1976). Mixture model tests of cluster analysis: Accuracy of four agglomerative hierarchical methods. Psychological Bulletin, 83(3), 377–388. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.83.3.377

- Blashfield, R. K., & Aldenderfer, M. S. (1988). The methods and problems of cluster analysis. In J. R. Nesselroade & R. B. Cattell (Eds.), Handbook of Multivariate Experimental Psychology (pp. 447–473). Springer US. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4613-0893-5_14

- Boster, J. S. (2005). Emotion categories across languages. In H. Cohen & C. Lefebvre (Eds.), Handbook of categorization in cognitive science (pp. 187–222). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-008044612-7/50063-9

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Cambridge Dictionary. (n.d.). https://dictionary.cambridge.org/

- Campos, J. J., Barrett, K. C., Lamb, M. E., Goldsmith, H. H., & Stenberg, C. (1983). Socioemotional development. In M. M. Haith & J. J. Campos (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology: Vol 2. Infancy and developmental psychobiology (4th ed), pp. 783–915. Wiley.

- China National Knowledge Infrastructure. (2021). https://www.cnki.net/

- Chinese Testing International. (2018). Chinese Proficiency Test (HSK). http://www.chinesetest.cn/gosign.do?id=1&lid=0.

- Collins Dictionary. (n.d.). https://www.collinsdictionary.com/

- Cowen, A. S., & Keltner, D. (2021). Semantic space theory: A computational approach to emotion. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 25(2), 124–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2020.11.004

- de Hooge, I. E., Breugelmans, S. M., Wagemans, F. M. A., & Zeelenberg, M. (2018). The social side of shame: approach versus withdrawal. Cognition and Emotion, 32(8), 1671–1677. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2017.1422696

- de Hooge, I. E., Breugelmans, S. M., & Zeelenberg, M. (2008). Not so ugly after all: When shame acts as a commitment device. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95(4), 933–943. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0011991

- de Hooge, I. E., Zeelenberg, M., & Breugelmans, S. M. (2007). Moral sentiments and cooperation: Differential influences of shame and guilt. Cognition and Emotion, 21(5), 1025–1042. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699930600980874

- de Hooge, I. E., Zeelenberg, M., & Breugelmans, S. M. (2010). Restore and protect motivations following shame. Cognition and Emotion, 24(1), 111–127. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699930802584466

- Ferguson, T. J., Stegge, H., & Damhuis, I. (1991). Children’s Understanding of Guilt and Shame. Child Development, 62(4), 827–839. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.1991.tb01572.x

- Fessler, D. (2004). Shame in two cultures: Implications for evolutionary approaches. Journal of Cognition and Culture, 4(2), 207–262. https://doi.org/10.1163/1568537041725097

- Fessler, D. M. T. (2007). From appeasement to conformity. In Jessica L. Tracy, R. W. Robins, & J. P. Tangney (Eds.), The self-conscious emotions: Theory and research (pp. 174–193). Guilford Press.

- Fiske, A. P. (2020). The lexical fallacy in emotion research: Mistaking vernacular words for psychological entities. Psychological Review, 127(1), 95–113. https://doi.org/10.1037/rev0000174

- Fontaine, J. R. J., & Breugelmans, S. M. (2021). Emotion between universalism and relativism: Finding a standard for comparison in cross-cultural emotion research. In M. Bender & B. G. Adams (Eds.), Methods and Assessment in Culture and Psychology (pp. 144–169). Cambridge University Press.

- Fontaine, J. R. J., Scherer, R. K., & Soriano, C. (2013). Components of emotional meaning: A sourcebook. Oxford University Press.

- Frank, H., Harvey, O. J., & Verdun, K. (2000). American responses to five categories of shame in Chinese culture: A preliminary cross-cultural construct validation. Personality and Individual Differences, 28(5), 887–896. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(99)00147-6

- Gao, J., Wang, A., & Qian, M. (2010). Differentiating shame and guilt from a relational perspective: A cross-cultural study. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 38(10), 1401–1407. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2010.38.10.1401

- Gausel, N., & Leach, C. W. (2011). Concern for self-image and social image in the management of moral failure: Rethinking shame. European Journal of Social Psychology, 41(4), 468–478. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.803

- Gehm, T. L., & Scherer, K. R. (1988). Relating situation evaluation to emotion differentiation: Nonmetric analysis of cross-cultural questionnaire data. In K. R. Scherer (Ed.), Facets of emotion: Recent research (pp. 61–77). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Gilbert, P., Pehl, J., & Allan, S. (1994). The phenomenology of shame and guilt: An empirical investigation. British Journal of Medical Psychology, 67(1), 23–36. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8341.1994.tb01768.x

- Giner-Sorolla, R. (2012). Shame and Guilt. In R. Giner-Sorolla (Ed.), Judging passions: Moral emotions in persons and groups (pp. 103–130). Psychology Press.

- Gray, K., Schein, C., & Cameron, C. D. (2017). How to think about emotion and morality: Circles, not arrows. Current Opinion in Psychology, 17, 41–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.06.011

- Gross, J. J., & John, O. P. (2003). Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: Implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(2), 348–362. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.85.2.348

- Haidt, J. (2003). The moral emotions. In R. J. Davidson, K. R. Scherer, & H. H. Goldsmith (Eds.), Handbook of affective sciences (pp. 852–870). Oxford University Press.

- Ho, D. Y.-F., Fu, W., & Ng, S. M. (2004). Guilt, shame and embarrassment: Revelations of face and self. Culture & Psychology, 10(1), 64–84. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354067X04044166

- Hwang, K. K. (2001). The deep structure of Confucianism: A social psychological approach. Asian Philosophy, 11(3), 179–204. https://doi.org/10.1080/09552360120116928/09552360120116928

- Keltner, D. (1996). Evidence for the distinctness of embarrassment, shame, and guilt: A study of recalled antecedents and facial expressions of emotion. Cognition & Emotion, 10(2), 155–172. https://doi.org/10.1080/026999396380312

- Ketelaar, T., & Au, W.-T. (2003). The effects of feelings of guilt on the behaviour of uncooperative individuals in repeated social bargaining games: An effect-as-information interpretation of the role of emotion in social interaction. Cognition and Emotion, 17(3), 429–453. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699930143000662

- Kim, U., Park, Y. S., & Park, D. (2000). The challenge of cross-cultural psychology: The role of the indigenous psychologies. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 31(1), 63–75. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022100031001006

- Kleeman, J., & Yu, H. (Eds.). (2010). The Oxford Chinese Dictionary: English-Chinese-Chinese English. Oxford University Press.

- Kollareth, D., Fernandez-Dols, J.-M., & Russell, J. A. (2018). Shame as a culture-specific emotion concept. Journal of Cognition and Culture, 18(3–4), 274–292. https://doi.org/10.1163/15685373-12340031

- Kollareth, D., Kikutani, M., & Russell, J. A. (2019). Shame is a folk term unsuitable as a technical term in science. In C. Mun (Ed.), Interdisciplinary perspectives on shame: Methods, theories, norms, cultures, and politics (pp. 3–26). Lexington Books/Rowman & Littlefield.

- Leach, C. W., & Cidam, A. (2015). When is shame linked to constructive approach orientation? A meta-analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 109(6), 983–1002. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspa0000037

- Lebra, T. S. (1971). The social mechanism of guilt and shame: The Japanese case. Anthropological Quarterly, 44(4), 241–255. https://doi.org/10.2307/3316971

- Lewandowska-Tomaszczyk, B., & Wilson, P. A. (2014). Self-conscious emotions in collectivistic and individualistic cultures: A contrastive linguistic perspective. In J. Romero-Trillo (Ed.), Yearbook of Corpus Linguistics and Pragmatics (pp. 123–148). Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-06007-1_7

- Lewis, H. B. (1971). Shame and guilt in neurosis. Psychoanalytic Review, 58(3), 419–438.

- Li, J., Wang, L., & Fischer, K. (2004). The organisation of Chinese shame concepts. Cognition & Emotion, 18(6), 767–797. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699930341000202

- Lickel, B., Kushlev, K., Savalei, V., Matta, S., & Schmader, T. (2014). Shame and the motivation to change the self. Emotion, 14(6), 1049–1061. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038235

- Lin, B., & Ng, B. C. (2012). Self-other dimension of Chinese shame words. International Journal of Computer Processing of Languages, 24(01), 51–78. https://doi.org/10.1142/s1793840612400041

- Markus, H. R., & Kitayama, S. (1991). Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychological Review, 98(2), 224–253. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.98.2.224

- Mascolo, M. J., Fischer, K. W., & Li, J. (2003). Dynamic development of component systems of emotions: Pride, shame, and guilt in China and the United States. In R. J. Davidson, K. R. Scherer, & H. H. Goldsmith (Eds.), Handbook of Affective Science (pp. 375–408). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470880166.hlsd001006

- Matsumoto, D., Yoo, S. H., & Nakagawa, S. (2008). Culture, emotion regulation, and adjustment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 94(6), 925–937. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.94.6.925

- Mendoza, A. H. de, Fernández-Dols, J. M., Parrott, W. G., & Carrera, P. (2010). Emotion terms, category structure, and the problem of translation: The case of shame and vergüenza. Cognition & Emotion, 24(4), 661–680. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699930902958255shameandvergüenza

- Miller, R. S., & Tangney, J. P. (1994). Differentiating embarrassment and shame. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 13(3), 273–287. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.1994.13.3.273

- Ogarkova, A., Soriano, C., & Lehr, C. (2012). Naming feeling: Exploring the equivalence of emotion terms in five european languages. In P. Wilson (Ed.), Dynamicity in Emotion Concepts (pp. 253–284). Peter Lang. https://doi.org/10.3726/978-3-653-01466-2

- Qian, M., Andrews, B., Zhu, R., & Wang, A. (2000). The development of Shame Scale of Chinese college students [In Chinese]. Chinese Mental Health Journal, 14, 217–221. http://zxws.cbpt.cnki.net/WKD/WebPublication/paperDigest.aspx?paperID=60daab63-f302-49cf-bb54-2fa565ceec0f

- Qian, Mingyi, & Qi, J. (2002). A comparative study on the difference between shame and guilt among Chinese collge students [In Chinese]. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 34(06), 74–81. http://journal.psych.ac.cn/acps/EN/abstract/abstract1829.shtml

- Sabini, J., & Silver, M. (1997). In defense of shame: Shame in the context of guilt and embarrassment. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour, 27(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-5914.00023

- Seiter, J. S., & Bruschke, J. (2007). Deception and emotion: The effects of motivation, relationship type, and sex on expected feelings of guilt and shame following acts of deception in United States and Chinese samples. Communication Studies, 58(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/10510970601168624

- Shaver, P. R., Wu, S., & Schwartz, J. C. (1992). Cross-cultural similarities and differences in emotion and its representation: A prototype approach. In M. S. Clark (Ed.), Review of personality and social psychology (Vol. 13), pp. 175–212. Sage Publications.

- Sheikh, S. (2014). Cultural variations in shame’s responses. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 18(4), 387–403. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868314540810

- Silfver-Kuhalampi, M., Fontaine, J. R. J., Dillen, L., & Scherer, K. R. (2013). Cultural differences in the meaning of guilt and shame. In J. J. R. Fontaine, K. R. Scherer, & C. Soriano (Eds.), Components of emotional meaning: A sourcebook (pp. 388–396). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/ACPROF:OSO/9780199592746.003.0027

- Smith, R. H., Webster, J. M., Parrott, W. G., & Eyre, H. L. (2002). The role of public exposure in moral and nonmoral shame and guilt. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83(1), 138–159. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.83.1.138