ABSTRACT

This study examined whether parents’ attribution of their child’s emotions (internalizing, externalizing) to dispositional causes is associated with children’s problem behaviour (internalizing, externalizing). The mediating roles of parents’ emotion-dismissing and -coaching reactions and the moderating role of child’s gender was also examined. Participants were 241 US parents with a child (43% girls) between the ages of 5 and 7. Parents were presented with vignettes in which a gender-neutral child displayed internalizing and externalizing emotions and were asked to imagine their own child in the vignettes. Subsequently, parents indicated whether they attributed the child’s emotion to dispositional causes and the likelihood of reacting in an emotion-dismissing and -coaching way in each situation. Child problem behaviour was measured using the CBCL. Results show that parental dispositional attributions were associated with child internalizing and externalizing problems, and this association was consistently mediated by emotion-dismissing reactions. The association between parental dispositional attributions and emotion-dismissing, as well as its indirect effect on child internalizing problems, was stronger for boys than for girls, whereas the indirect effect via emotion-coaching was stronger for girls than for boys. Thus, the parental attribution process seems to be different for boys and girls.

An important contributor to healthy development in children, is the ability to regulate emotions (Blair & Diamond, Citation2008). Deficits in emotion regulation abilities have often been associated with both internalizing and externalizing problems as well as other forms of psychopathology in children (Zahn-Waxler et al., Citation2000; Zeman et al., Citation2006). For children aged 4–11, the prevalence estimates for anxiety disorders range from 1.57% to 6.9%, and 0.12% to 1.1% for major depressive disorders (Johnstone et al., Citation2018; Lawrence et al., Citation2015). During COVID-19, these prevalence estimates have doubled (Racine et al., Citation2021). The prevalence of externalizing disorders (e.g. conduct disorder, oppositional defiant disorder) ranges between 4.0% to 8.1% in children and adolescents (Polanczyk et al., Citation2015). There are no gender differences in depression for young children, but girls are more likely to have an anxiety disorder compared to boys (Lewinsohn et al., Citation1998; Scheider & Weisz, Citation2017), whereas externalizing problems are more prevalent in boys (Rescorla et al., Citation2007). Identifying the factors that contribute to the development of child problem behaviour is crucial for prevention of mental health problems (Bariola et al., Citation2011). The current study therefore focused on how parental dispositional attributions and reactions to their child’s emotions are related to child internalizing and externalizing problems, and whether child gender moderated these associations.

Parental attributions about children’s emotions

Parents play a key role in the development of emotion regulation abilities of their children through their emotion socialisation practices, i.e. the ways in which parents teach their children about emotions (Root & Rubin, Citation2010). Parents’ emotion socialisation practices are influenced by the beliefs and feelings that parents have about their own and their children’s emotions. This set of feelings and beliefs about emotions is also called the parental meta-emotion philosophy (Gottman et al., Citation1996). Part of this meta-emotion philosophy are attributions, which represent the causal beliefs about the reason for situations or events (Weiner, Citation2010). Two types of attributions are often examined: situational attributions, which are explanations that emotions are caused by something external, and dispositional attributions, in which emotions are explained as the result of traits of the actor or factors internal to the actor (Weiner, Citation2010).

A lot of research has been done on the attributions parents make about their children’s (mis)behaviour (e.g. Colalillo et al., Citation2015; Johnston et al., Citation2009; Kill et al., Citation2021; Mills & Rubin, Citation1990), but few studies have focused on parents’ attributions for their children’s emotion expression (Bougher-Muckian et al., Citation2019). The focus on the attributions parents make about child emotions is important especially in the context of children’s internalizing and externalizing problems, as both types of problems include disturbances in emotion or mood (Graber, Citation2004). Thus, parental attributions about child emotions might be particularly relevant predictors of child internalizing and externalizing problems. The small body of research on the attributions people make about emotion expression suggests that parents and non-parents attribute negative emotion expressions both to dispositional and situational causes (Barrett & Bliss-Moreau, Citation2009; Bougher-Muckian et al., Citation2019; Brescoll & Uhlmann, Citation2008). Yet, non-parents made more dispositional attributions for women’s internalizing (i.e. sadness, fear) and externalizing (i.e. anger) emotion expression compared to men’s (Barrett & Bliss-Moreau, Citation2009; Brescoll & Uhlmann, Citation2008). Since dispositional attributions about emotions appear to differ depending on gender, they might be specifically relevant to examine in relation to child internalizing and externalizing emotions and child gender.

Parental dispositional attributions and child problem behaviour

The attribution literature consistently shows that when parents make more dispositional attributions about their child’s misbehaviour, this is associated with more externalizing problem behaviours in their children (Colalillo et al., Citation2015; Johnston et al., Citation2009; Kill et al., Citation2021; McKee et al., Citation2008; Park et al., Citation2018). The tendency to make dispositional or internal attributions is also seen in the scant research linking parents’ attributions to children’s internalizing problems (Kill et al., Citation2021), although none of these studies specifically examined parental attributions for child emotions. For instance, in one study, parents of depressed adolescents made more dispositional attributions for their child’s positive and negative behaviour than parents of non-depressed adolescents (Sheeber et al., Citation2009). In another study, parents’ internal attributions about child misbehaviour were positively related to children’s internalizing problems during middle childhood (Colalillo et al., Citation2015).

Moderation by child gender

There are no indications in the literature that child gender moderates the association between parents’ dispositional attributions and child externalizing problems (Colalillo et al., Citation2015; Park et al., Citation2018). Regarding internalizing problems, however, parents’ dispositional attributions for adolescent behaviour were related to adolescent depressive symptoms and this association was stronger for girls than for boys (Chen et al., Citation2009). However, this gender difference was explained by the fact that during adolescence, girls start to value interpersonal intimacy more than boys. As a result, girls might become more vulnerable for their parents’ negative interpretations of their behaviour than boys do (Chen et al., Citation2009; Cyranowski et al., Citation2000). Therefore, it remains to be studied whether there is also a differential effect of dispositional attributions about children’s emotions on internalizing and externalizing problems for younger boys and girls.

Parental dispositional attributions and reactions to child emotions

The relation between dispositional parental attributions and child problem behaviour could be explained by the reaction of the parent to the child’s emotions. Based on the framework of parental meta-emotion philosophy, parental reactions to children’s emotions can be divided in emotion-coaching and emotion-dismissing reactions (Gottman et al., Citation1996). Emotion-coaching is characterised by parental awareness of emotions in their children, validation of their children’s emotions, and negative emotions are seen as opportunities for intimacy and for teaching children how to handle the situation that elicited the emotion (Gottman et al., Citation1996; Katz et al., Citation2012). On the other hand, emotion-dismissing reactions are characterised by denying or ignoring negative emotions, as well as minimising and punitive parental responses to the child’s emotions (Gottman et al., Citation1996; Havighurst et al., Citation2010; Zeman et al., Citation2010).

There is ample evidence that the attributions that parents make about the behaviour of their children, seem to influence parenting behaviours towards the child (Colalillo et al., Citation2015; Eisenberg et al., Citation1996; Leung & Smith Slep, Citation2006). In general, attributing a child’s negative behaviours to dispositional or internal causes has been associated with more negative reactions to the child’s behaviour by parents (for reviews, see Bugental & Corpuz, Citation2019; Miller, Citation1995). Yet again, little is known about whether such dispositional attributions are also related to more negative parental reactions to the emotional displays of their children. Some studies with infants demonstrated that negative or minimising attributions of infant crying have been associated with respectively harsh parenting (Bailes & Leerkes, Citation2021; Martin et al., Citation2018) and more parental rejection and ignoring in response to infant crying (Leerkes et al., Citation2016). Based on the consistently found association between parents’ dispositional attributions for child behaviour and negative parental reactions (Park et al., Citation2018; Sturge-Apple et al., Citation2014; Wagner et al., Citation2018), we expect to find a similar association between parents’ dispositional attributions for their child’s emotions and parental emotion-dismissing reactions (higher) and emotion-coaching reactions (lower).

Moderation by child gender

The association between parents’ dispositional attributions and parental emotion-dismissing and -coaching reactions might also be different for boys and girls. In Western cultures, girls are expected to be more emotionally expressive than boys, especially for positive emotions and internalizing emotions (Chaplin, Citation2015; Root & Rubin, Citation2010). On the other hand, boys are more often allowed to show externalizing emotions, such as anger, than girls (Brody & Hall, Citation2008; Chaplin, Citation2015). Parents have also been found to react in an emotion-dismissing (or less coaching) way when internalizing emotions are expressed by a boy compared to a girl, whereas they are more dismissive (or less supportive) of girls’ expression of externalizing emotions (Barrett & Bliss-Moreau, Citation2009; Chaplin et al., Citation2005; Chaplin, Citation2015; Eisenberg et al., Citation1996). Expressing these gender-atypical emotions does not fit with prevailing gender stereotypes. In addition, as mentioned before, expression of internalizing and externalizing emotions is attributed more to dispositional causes for women than for men (Barrett & Bliss-Moreau, Citation2009; Brescoll & Uhlmann, Citation2008). Thus, it appears that parents might differentiate between boys and girls in their attributions of, and responses to, their child’s internalizing and externalizing emotions. Yet, it remains unclear whether the relation between parental dispositional attributions and parents’ emotion-dismissing or -coaching reactions is also different for boys and girls.

Parents’ emotion-dismissing and -coaching reactions and child problem behaviour

According to the framework of parental meta-emotion philosophy, parents’ emotion-dismissing reactions may give children the message that they need to protect themselves for negative emotions or are not allowed to express such emotions (Katz et al., Citation2012). Therefore, a child might not learn how to regulate their emotions efficiently, which is associated with poorer psychosocial adjustment (Denham et al., Citation2015; Eisenberg et al., Citation1996; Ornaghi et al., Citation2019; Shaffer et al., Citation2012; Ugarte et al., Citation2021). In contrast, emotion-coaching is thought to improve key aspects of children’s emotional competence, such as emotional awareness, expression, and regulation, which in turn are related with better psychosocial adjustment in children (Katz et al., Citation2012). There is ample evidence that more emotion-dismissing and less coaching reactions from parents are associated with more internalizing and externalizing problem behaviour in children (Brajsa-Zganec, Citation2014; Eisenberg et al., Citation1996; Eisenberg et al., Citation1999; Johnson et al., Citation2017; Ugarte et al., Citation2021). However, there are also studies that do not find evidence for direct benefits of emotion-coaching for children’s psychosocial adjustment (Lunkenheimer et al., Citation2007).

Moderation by child gender

There is also some evidence that the relation between parents’ emotion-dismissing reactions and both internalizing and externalizing behaviour problems is stronger for boys than for girls (Eisenberg et al., Citation1999; Engle & McElwain, Citation2011; Grady, Citation2020; Roberts, Citation1999; Suh & Kang, Citation2020). Similarly, emotion-coaching responses have been found to be more strongly associated with boys’ than girls’ emotional, social, and academic adjustment (Brody, Citation2000; Cunningham et al., Citation2009). Boys might be more likely to either internalize or externalize their emotions, particularly when parents dismiss or fail to support emotion expression, as such parental discouragement highlights the presence of societal gender norms that restrict boys’ and men’s emotion expression (Eisenberg et al., Citation1999; Engle & McElwain, Citation2011). However, there are also studies in which the association between parental reactions to children’s emotions and child problem behaviour was not different for boys and girls (Eisenberg & Fabes, Citation1994; Fabes et al., Citation2001). This inconsistency in previous findings highlights the need for more research on this topic to elucidate under which conditions associations emerge.

The current study

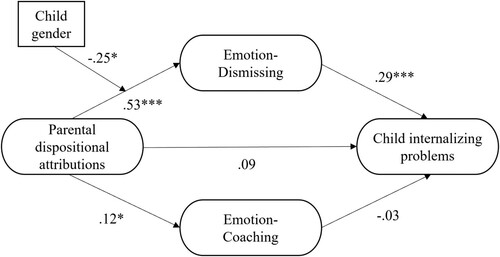

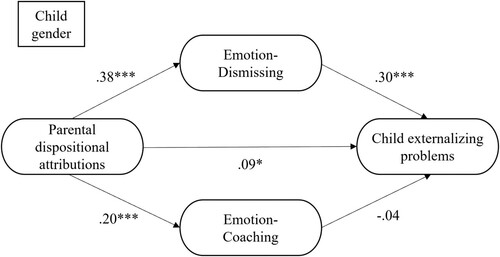

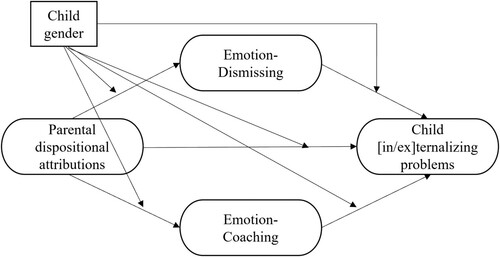

This study examined the association between dispositional attributions that parents make about the internalizing and externalizing emotions of their children and the internalizing and externalizing problems of their children. In addition, this study investigated whether the emotion-dismissing and -coaching reactions of parents mediated the relation between dispositional attributions from parents and internalizing and externalizing problems of the child. Finally, it was examined whether these associations were different for boys and girls. See for an overview of the associations that were studied, separately for externalizing and internalizing emotions and problems.

Figure 1. Moderated mediation model tested separately via PROCESS for externalizing and internalizing problems.

It was hypothesized that: (1) more dispositional attributions from parents would be associated with more internalizing and externalizing problems of the child, and that this association was stronger for girls than for boys; (2) parental dispositional attributions about child emotions would be associated with more emotion-dismissing, but less emotion-coaching, and these associations may be different for boys and girls; (3) more emotion-dismissing and less emotion-coaching from parents would be associated with more child problem behaviour, and this association was stronger for boys than for girls; (4) emotion-dismissing and -coaching reactions of parents would be mediators in the association between parental dispositional attributions and child problem behaviour, and these indirect effects may be different for boys and girls.

Method

Participants

Participants were recruited via Amazon Mechanical Turk (MTurk) in 2 batches in December 2021 (1st batch December 9: n = 200; 2nd batch December 10: n = 62). MTurk is a web service that provides an on-demand, scalable, human workforce to complete research tasks in return for payment. MTurk samples were found to be more demographically representative than convenience samples recruited in person and data quality is high when appropriate (attention) checks are in place (Huff & Tingley, Citation2015). Via MTurk we recruited U.S. parents to complete an online questionnaire (see Procedure) assessing the causes parents attribute to the behaviour of their children. MTurk workers could find the survey with the following keywords: survey, child, gender, boys, girls, parenting, behaviour, emotions, attributions. Participants could access the survey only if they had a U.S.-based IP-address, a child between the ages of 5 and 7 years old, and a 65% approval rating from other requesters for prior surveys. From the 262 participants, 21 were excluded because they failed more than 1 of the 8 attention checks (e.g. “Click on the response option ‘strongly disagree””), resulting in a final sample of 241 participants. See for sample characteristics. The sample was highly educated and most parents were married.

Table 1. Sample characteristics.

Procedure

Each parent completed an online survey via Qualtrics that consisted of questions about a series of vignettes (see section “Instruments”) as well as questionnaires about parental cognitions, parenting practices, and child problem behaviour (duration: approximately 30-45 min). For the current study only the questions about the internalizing and externalizing emotion vignettes were used, as well as a questionnaire on child problem behaviour. Parents provided informed consent for their participation at the beginning of the survey. Subsequently, participants were asked if they indeed had a child aged 5, 6, or 7 years old. When they had more than one child in this age category, they were asked to complete the questions for their oldest child. Next, parents had to enter their child’s first name. This name was then incorporated in the questionnaires and vignettes to make it easier for parents to envision their child in the questionnaires and vignettes. Parents received 5 USD compensation for their participation. This study received approval of the Ethical Review Board of the Faculty of Social and Behavioural Sciences at Utrecht University (FETC21-0347).

Instruments

Vignettes

A quasi-experimental approach was taken that is commonly used in the attribution literature (Miller, Citation1995); presenting parents with vignettes illustrating the child emotions of interest and asking parents to imagine their own child acted in the ways depicted in the vignettes. Six vignettes that were specifically about internalizing and externalizing emotions of children were used for the current study. Six images from the Emotion Picture Book were selected for the emotion vignettes (van der Pol et al., Citation2015): (1) a sad and crying child with a broken scooter; (2) a sad and crying child next to a broken swing; (3) a scared child on top of a high slide; (4) a child that is scared to jump in the swimming pool; (5) an angry child that wants a toy in a toy store; (6) an angry child that wants candy. In addition, the descriptions in the vignettes were based on previous vignettes used to assess attributions about emotions (Root & Rubin, Citation2010). An example description that was used is: “[name child] comes home sad and crying after playing outside. The scooter that [name child] got last week is broken.” See Supporting Information for all the vignettes and the accompanying questions.

Questions about parental attributions and reactions

Following each vignette, parents were asked several questions about the causes of the child’s emotions, followed by questions about parents’ hypothetical reactions. The same order of questions was used to be able to test the sequence of the proposed mediation model (i.e. attribution > reaction).

First, parents indicated why they thought their child felt or behaved this way. Specifically, regarding dispositional attributions, parents rated on a 5-point scale (1 = very unlikely, 5 = very likely) how likely they thought their child’s emotions had a dispositional cause, i.e. “[Name child] is an emotional child”.

Second, parents indicated what they would do when they would be in this situation with their child. Specifically, regarding emotion-dismissing reactions (Shewark & Blandon, Citation2015; Shaffer et al., Citation2012; Wilson et al., Citation2016) parents rated on a 5-point scale (1 = very unlikely, 5 = very likely) how likely it was that they would react in two emotion-dismissing ways: (1) “Tell [name child] to stop overreacting” (i.e. minimalizing reaction/criticizing the emotion); (2) “Tell [name child] to get down the slide or else you go home” (i.e. punishment). In addition, they rated on the same 5-point scale the likelihood of reacting in four emotion-coaching ways (Katz et al., Citation2012): (1) “Reassure [name child] that it is okay to cry when hurt”; (2) “Help [name child] to figure out how to get the swing fixed”; (3) “Ask why [name child] is feeling this way”; (4) “Comfort [name child]”. For the externalizing emotion vignettes an additional emotion-coaching item was completed, i.e. “Talk with [name child] and explain why he/she cannot get the toy.”

Parents’ responses to the dispositional attribution question and parental emotion-dismissing and -coaching questions were averaged across the four internalizing vignettes and the two externalizing vignettes. This procedure resulted in the variables “dispositional attribution of child internalizing emotions’ (Cronbach’s α = .80, four items), “dispositional attribution of child externalizing emotions’ (Cronbach’s α = .62, two items), “parental dismissing of internalizing emotions’ (Cronbach’s α = .85, eight items), “parental dismissing of externalizing emotions’ (Cronbach’s α = .67, four items), “parental coaching of internalizing emotions’ (Cronbach’s α = .88, 16 items), “parental coaching of externalizing emotions’ (Cronbach’s α = .79, eight items). Higher scores on these variables indicated respectively that parents were more likely to make dispositional attributions about the child’s emotions and that parents were more likely to respond in an emotion-dismissing or coaching way. Principal component analyses revealed that for each scale all items loaded on one factor (see Supporting Information).

Finally, to check the ecological validity of the vignettes we asked parents after each vignette “How often does this situation, or something similar, occur in your family?”. They responded on a 5-point scale (1 = almost never, 2 = weekly, 3 = multiple times a week, 4 = daily, 5 = multiple times a day).

Internalizing and externalizing problems of the child

To measure the level of internalizing and externalizing problems of the child, parents completed the Child Behavior Checklist 1,5-5 (CBCL) (Achenbach, Citation1999). The CBCL is a widely used instrument to examine emotional and behavioural problems in children. The CBCL consists of the broadband scales internalizing problems and externalizing problems. The internalizing scale (19 items) combines the syndrome scales “withdrawn/depressed” and “anxious’. The externalizing scale (31 items) combines the syndrome scales “oppositional behaviour”, “aggressive behaviour”, and “overactive behaviour”. For all subscales, both the convergent and divergent validity were rated as favourable, when comparing these subscales to other widely used instruments that assess internalizing and externalizing problems in children (Nakamura et al., Citation2009). An example item of the internalizing scale was “Looks unhappy without a good reason.” An example item of the externalizing scale was “Gets in many fights.” Parents indicated to what extent an item about their child is (0) not true, (1) somewhat true, or (2) very true. The ratings on the items were averaged into an internalizing problems scale (Cronbach’s α = .92) and an externalizing problems scale (Cronbach’s α = .94). Higher scores indicated that parents reported higher levels of respectively internalizing problems and externalizing problems for the child.

Child gender

Parents were asked to indicate whether their child was a boy, girl or other. There were no parents who indicated the option “other”.

Data analysis

The data were analysed using SPSS Statistics 28. First, independent t-tests were performed to examine gender differences on the study variables and Pearson correlation coefficients were computed to examine associations between the study variables. Second, simple mediation analyses were conducted, using the PROCESS macro (version 4.1; Hayes, Citation2022). For this mediation analyses, dispositional attributions of parents were the independent variable and child problem behaviour was the dependent variable. The parental emotion-dismissing and -coaching reactions were included as mediators. The model was tested separately for internalizing and externalizing behaviour.

When a significant indirect effect was found between dispositional attributions of parents and the behaviour problems of the child, a moderated mediation analysis was subsequently performed, with gender of the child (0 = boy, 1 = girl) included as a moderator of all paths in the mediation model (see ). Again, the model was tested separately for internalizing and externalizing behaviour. For both the direct and indirect effects of parental attributions on child problem behaviour, the moderation by child gender was examined. For the mediation model and the moderated mediation model 5000 bootstrap resamples were used and 95% bias-corrected (BC) confidence intervals were computed. For each analysis, we determined which covariates (i.e. child age, parent education, marital status, family composition, number of children) needed to be included based on the change-in-estimate method, > 5% change criterion (Rothman et al., Citation2008).

Results

Descriptive statistics and data inspection

For means, standard deviations, and correlations between the variables for boys and girls see . There were no significant differences between boys and girls on any of the variables (attributions INT: t(239) = −0.97, p = .331; attributions EXT: t(237.2) = −1.86, p = .064; dismissing INT: t(239) = 0.97, p = .334; coaching INT: t(239) = 0.42, p = .966; dismissing EXT: t(239) = 0.37, p = .710; coaching EXT: t(239) = 0.13, p = .897; internalizing problems: t(239) = 0.22, p = .830; externalizing problems: t(239) = −0.04, p = .970). Most variables were significantly correlated, with a positive direction, for both boys and girls. Non-significant correlations were mostly found with the emotion-coaching variables. All variables approached a normal distribution. There were three outliers on the emotion-coaching variables that were winsorized (highest non-outlying number + difference between highest non-outlying number and before highest non-outlying number; Tabachnick & Fidell, Citation2012). The data satisfied the assumption of absence of multicollinearity, with tolerance between .67 and .98 and VIF between 1.02 and 1.49.

Table 2. Means, Standard Deviations and correlations.

The vignettes appeared to be describing ecologically valid situations for most parents as on average parents rated that the situations occurred in their family weekly to multiple times a week (internalizing emotion-eliciting situations: M = 2.57, SD = 0.90; externalizing emotion-eliciting situations: M = 2.64, SD = 0.87).

Simple mediation models

Internalizing problems

The simple mediation model for internalizing problems explained a significant 31.6% of the variance (F(3, 237) = 36.49, p < .001). Dispositional attributions significantly predicted parent’s dismissing (b = 0.48, SE = .05, p < .001) and coaching reactions (b = 0.16, SE = .04, p < .001) to child internalizing emotions. Higher levels of emotion-dismissing (b = 0.26, SE = .04, p < .001) and lower levels of emotion-coaching reactions (b = −0.10, SE = .04, p = .024) were associated with higher levels of child internalizing problems. The direct effect of dispositional attributions on child internalizing symptoms (b = 0.08, SE = .03, p = 0.024, 95%CI[0.01, 0.15]) was partially mediated via parents’ emotion-dismissing (b = 0.13, SE = .02, 95%CI[0.08, 0.17]) and emotion-coaching reactions (b = −0.02, SE = .01, 95%CI[−0.04, −0.001]).

Externalizing problems

The simple mediation model for externalizing problems explained a significant 27.7% of the variance (F(3, 237) = 30.19, p < .001). Dispositional attributions significantly predicted parent’s dismissing (b = 0.38, SE = .04, p < .001) and coaching reactions (b = 0.20, SE = .04, p < .001) to child externalizing emotions. Higher levels of emotion-dismissing reactions (b = 0.24, SE = .04, p < .001) were associated with higher levels of child externalizing problems. Emotion-coaching was not associated with externalizing problems (b = −0.04, SE = .05, p = .389). The direct effect of dispositional attributions on child externalizing symptoms (b = 0.09, SE = .03, p = 0.019, 95%CI[0.04, 0.15]) was partially mediated via parents’ emotion-dismissing reactions (b = 0.09, SE = .02, 95%CI[0.05, 0.13]), but not via parents’ emotion-coaching reactions (b = −0.01, SE = .01, 95%CI[−0.03, 0.01]).

Moderated mediation by child gender

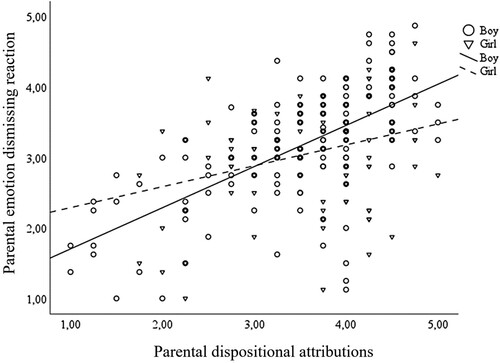

shows statistics for the moderation of the associations between parental dispositional attributions and emotion-dismissing and -coaching reactions by child gender. shows statistics for the moderation of the associations between child behaviour problems and parental dispositional attributions and emotion-dismissing and -coaching reactions by child gender.

Table 3. Dispositional attributions and gender as predictors of parents’ emotion-dismissing and emotion-coaching reactions to children’s internalizing and externalizing emotions.

Table 4. Dispositional attributions, parents’ emotion-dismissing and emotion-coaching reactions, and child’s gender as predictors of child’s internalizing and externalizing problems.

Internalizing problems

As can be seen in , dispositional attributions were a significant predictor for parents’ dismissing and coaching reactions to child internalizing emotions. Gender of the child was no significant predictor of parents’ emotion-dismissing or emotion-coaching reactions to child internalizing emotions. The interaction between dispositional attributions and gender of the child was significant for emotion-dismissing, but not for emotion-coaching. The effect of dispositional attributions on parents’ emotion-dismissing reactions was stronger for parents of boys (b = 0.53, SE = .06, 95%CI[0.41, 0.65]) than for parents of girls (b = 0.28, SE = .08, 95%CI[0.12, 0.45]) (see ).

Figure 2. Conditional effects of dispositional attributions on parents’ emotion-dismissing reactions.

As can be seen in , dispositional attributions, emotion-coaching reactions, and child gender did not significantly predict internalizing problems of the child, but parents’ emotion-dismissing reactions was a significant predictor. All 3 interactions with child gender were non-significant. The indirect effects from dispositional attributions on child internalizing problems, via parental emotion-dismissing (b = −0.09, SE = .04, 95%CI[−0.18, −0.01]) and emotion-coaching reactions (b = −0.04, SE = .02, 95%CI[−0.11, −0.004]), were significantly different for boys and girls. Although significant in both boys and girls, the indirect effect via emotion-dismissing reactions was stronger for boys (b = 0.15, SE = .03, 95%CI[0.09, 0.23]) than for girls (b = 0.06, SE = .03, 95%CI[0.02, 0.12]). In contrast, the indirect effect via emotion-coaching reactions was stronger for girls (b = −0.05, SE = .03, 95%CI[−0.12, −0.01]) than for boys (b = −0.003, SE = .01, 95%CI[−0.03, 0.01]). The direct effect of dispositional attributions on internalizing problems was no longer significant for boys (b = 0.09, SE = 0.05, 95%CI[−0.01, 0.18]), but remained significant for girls (b = 0.11, SE = 0.06, 95%CI[0.003, 0.22]), which indicates complete mediation for boys and partial mediation for girls. The whole moderated-mediation model predicting internalizing problems of the child explained a significant 38% of the variance (F(11, 229) = 12.53, p < .001). For a visualization of this model, see .

Externalizing problems

As can be seen in , dispositional attributions were a significant predictor for parents’ dismissing and coaching reactions to child externalizing emotions. Gender of the child was no significant predictor of parents’ emotion-dismissing or emotions-coaching reactions to child externalizing emotions. The interaction between dispositional attributions and gender of the child was not significant for parental emotion-dismissing nor for emotion-coaching reactions.

As can be seen in , emotion-coaching reactions and child gender did not predict externalizing problems of the child, but parents’ dispositional attributions and emotion-dismissing reactions were significant predictors. All 3 interactions with child gender were non-significant. Similarly, the indirect effects from dispositional attributions on child externalizing problems, via parental emotion-dismissing and emotion-coaching reactions, were not moderated by child gender (dismissing: b = −0.05, SE = .04, 95%CI[−0.13, 0.03]; coaching: b = 0.004, SE = .02, 95%CI[−0.04, 0.04]). The whole moderated-mediation model predicting externalizing problems of the child explained a significant 36% of the variance (F(11, 229) = 11.92, p < .001). For a visualization of this model, see .

Discussion

This study examined the direct and indirect effects of parental dispositional attributions about their child’s emotions in hypothetical situations and parental emotion-dismissing and -coaching reactions on children’s problem behaviour. Additionally, it was investigated whether these effects were different for boys and girls. Results showed that more dispositional attributions of parents about their child’s hypothetical emotions were associated with more behaviour problems of the child, and this was found for both internalizing and externalizing emotions and behaviours. These associations were explained by parents’ emotion-dismissing (for internalizing and externalizing behaviour) and emotion-coaching reactions (for internalizing behaviour only). Regarding gender differences, the relation between parental dispositional attributions about internalizing emotions and emotion-dismissing reactions was stronger for boys than for girls. Similarly, the indirect effect of parental dispositional attributions on child internalizing problems, via emotion-dismissing reactions of parents, was stronger for boys than for girls, whereas the indirect effect via emotion-coaching was stronger for girls than for boys.

Parental dispositional attributions and child problem behaviour

As expected, when parents made dispositional attributions about their child’s internalizing or externalizing emotions in hypothetical situations, this was associated respectively with more internalizing or externalizing problems in their children. Previous research already demonstrated a link between parents’ dispositional attributions for child (mis)behaviour and depressive symptoms in adolescents (Chen et al., Citation2009; Sheeber et al., Citation2009) and internalizing and externalizing behaviour problems in childhood (Colalillo et al., Citation2015; Johnston et al., Citation2009; Kill et al., Citation2021; McKee et al., Citation2008; Park et al., Citation2018). The current study extends this work by showing that the dispositional causes parents attribute to children’s expression of emotions also plays a role in both internalizing and externalizing problems in early and middle childhood. This makes sense considering the strong affective component of internalizing and externalizing problems (Graber, Citation2004).

However, no differences between boys and girls were found in this association, even though a previous study with adolescents showed that parents’ dispositional attributions were more strongly related to depressive symptoms of girls than for boys (Chen et al., Citation2009). The gender difference found in the previous study might be specific for adolescence, a period in which girls start to value interpersonal intimacy more than boys, which might make them more vulnerable for parents’ negative interpretations of their emotions (Chen et al., Citation2009; Cyranowski et al., Citation2000).

Parental dispositional attributions and emotion-dismissing and -coaching reactions

Consistent with our hypothesis, more parental dispositional attributions about children’s internalizing or externalizing emotions were associated with more emotion-dismissing reactions to these emotions in hypothetical situations. Additionally, for internalizing emotions, this association was found to be even stronger for boys than for girls. These findings extend earlier research demonstrating that parental dispositional attributions are not only related to more negative parenting responses to child (mis)behaviour (Sturge-Apple et al., Citation2014; Wagner et al., Citation2018), but also to more dismissing reactions to children’s expression of negative emotions. The stronger association for boys is consistent with the prevailing gender norms in Western cultures, in which men are not expected and allowed to express internalizing emotions (Barrett & Bliss-Moreau, Citation2009; Chaplin, Citation2015; Root & Rubin, Citation2010). The bio-psycho-social model of gender differences in child emotion expression, developed by Chaplin (Citation2015), helps in understanding this gender difference. This theory argues that early biologically-based gender differences in arousal or inhibitory control lead to greater expression of negative emotions in boys compared to girls in infancy (Brody, Citation1999; Weinberg et al., Citation1999). Subsequently, parents respond in ways that dampen boys’ emotion expression (i.e. particularly internalizing emotions) to be consistent with gender roles. Then, it makes sense that when parents of boys attribute internalizing emotions more to dispositional causes (e.g. internal, biological, stable), this is associated with stronger emotion-dismissing reactions than in parents of girls, as a way to correct or minimize the gender-atypical emotion expression of boys. Yet, counterintuitively, this emotion-dismissing strategy of parents is subsequently associated with more, instead of less, gender-atypical internalizing problems in boys.

Somewhat unexpectedly, making more dispositional attributions about children’s internalizing and externalizing emotions were also associated with more emotion-coaching reactions to these emotions in hypothetical situations. Previous research already demonstrated that emotion-coaching and emotion-dismissing are not necessarily negatively correlated and can be considered independent aspects of parental emotion socialisation (Lunkenheimer et al., Citation2007). In the current study, emotion-coaching and dismissing reactions were not associated in the context of child internalizing emotions, but there was a weak positive association in the context of externalizing emotions. Possibly, parents who believe their child is a highly emotional child might employ both emotion-coaching and dismissing to regulate the child’s emotions, particularly when the child expresses externalizing emotions.

Parental emotion-dismissing and -coaching and child problem behaviour

As hypothesized, a stronger emotion-dismissing response of parents to the hypothetical internalizing or externalizing emotions of their children was associated respectively with more internalizing or externalizing problems in the child. Similarly, more parental emotion-coaching of children’s internalizing emotions was associated with less internalizing problems in the child. This is consistent with previous research (Brajsa-Zganec, Citation2014; Eisenberg et al., Citation1996; Eisenberg et al., Citation1999; Johnson et al., Citation2017; Ugarte et al., Citation2021). Emotion-dismissing reactions may send the message to the child that they should not express their emotions. Consequently, children have little opportunity to learn how to effectively regulate their emotions together with their parents, which is a risk factor for the development of internalizing and externalizing problems (Denham et al., Citation2015; Eisenberg et al., Citation1996; Ornaghi et al., Citation2019; Shaffer et al., Citation2012; Ugarte et al., Citation2021). On the other hand, emotion-coaching is thought to foster children’s emotional competence, which is associated with better psychosocial adjustment (Katz et al., Citation2012).

Last, contrary to expectations, this study found no differences between boys and girls in the relation between parents’ emotion-dismissing and -coaching reactions and child problem behaviour. Previous research did show, although not consistently, that the association between parental reactions to children’s negative emotions and child behaviour problems was stronger for boys than for girls (Eisenberg et al., Citation1999; Engle & McElwain, Citation2011; Grady, Citation2020; Roberts, Citation1999; Suh & Kang, Citation2020). A possible explanation for the different findings could be that previous research did not focus specifically on parental reactions to internalizing or externalizing emotions, but on reactions to negative emotions in general. Alternatively, the previous studies that did find evidence for boys’ being more vulnerable to parents’ emotion-dismissing and emotion-coaching, all used questionnaires to assess parents’ emotion socialisation practices, whereas the current study used a quasi-experimental vignette design.

Indirect effects

Regarding indirect effects, the association between parental dispositional attributions and problem behaviour was partially explained by the emotion-dismissing and -coaching reactions of the parent in hypothetical emotion-eliciting situations. Specifically, parents who made more dispositional attributions about their child’s internalizing (or externalizing) emotions were more likely to react in a emotion-dismissing way to these emotions, and this was subsequently associated with more internalizing (or externalizing) problems of the child. Similarly, it has been argued in the attribution literature that when parents believe their child’s behaviour has dispositional causes, they hold their child responsible for the behaviour, which might elicit negative emotions in parents, and subsequently increases the likelihood that parents will react in a negative way (Bugental et al., Citation1998; Dix & Grusec, Citation1985). In turn, these negative parenting practices increase the risk of psychosocial maladjustment in children. Importantly, the indirect effect of the dispositional attributions of parents on internalizing problems of the child, via the emotion-dismissing reaction of parents, was stronger for boys than for girls. The stronger indirect effect for boys was mainly driven by a stronger association between parental dispositional attributions and emotion-dismissing reactions for boys compared to girls, which was discussed in depth in the third paragraph of the discussion.

Somewhat counter-intuitively making dispositional attributions about the child’s emotions was also related to more emotion-coaching and subsequently, to less internalizing problems in children (specifically girls). A possible explanation for this inconsistent mediation effect (MacKinnon et al., Citation2007) could be that parents who think their child has an emotional disposition might use both emotion-coaching and dismissing to regulate the child’s emotions. Yet, only the emotion-coaching strategy appeared to be beneficial for children’s internalizing psychosocial functioning. That we found this indirect effect via emotion-coaching to be stronger for girls might be because parents expect girls’ to be more vulnerable to develop internalizing problems than boys (Zahn-Waxler et al., Citation2008). Especially when they see their daughter as a highly emotional child (dispositional attribution) they might use emotion-coaching to foster emotion regulation skills and reduce the risk of their daughter developing internalizing problems.

Finally, emotion-coaching did not mediate the association between dispositional attributions and externalizing problems. Indications of the lower predictive value of emotion-coaching compared to emotion-dismissing has been found in previous research as well (Johnson et al., Citation2017; Lunkenheimer et al., Citation2007). From the current study it appears that emotion-coaching might be less relevant for externalizing problems compared to internalizing problems, possibly because of the stronger affective component in internalizing disorders compared to externalizing disorders (Graber, Citation2004).

Limitations and directions for future research

One of the limitations of this study is that it is solely based on parental self-report. The parenting reactions and child behaviour that the parents report in the survey might be different from their actual behaviour or their child’s behaviour, due to distorted recall or social desirability (Smith, Citation2011). Future research could use additional methods (e.g. observation) to assess parents’ reactions to children’s emotions, as well as different informants to assess children’s problem behaviour.

Another limitation of this study was that the role of cultural background was not acknowledged. Effects of parental emotion-dismissing and -coaching reactions might be different across cultural contexts. For instance, for Chinese children, minimizing reactions from parents to their negative emotions were not associated with negative child outcomes (Tao et al., Citation2010), possibly due to a different cultural meaning of parental minimizing reactions (Corapci et al., Citation2012; Tao et al., Citation2010). It is therefore important that follow-up research investigates the role of culture, to test whether the findings of the current study can be generalized to other cultural groups.

A third limitation concerns the quasi-experimental design of this study in which parental attributions and responses to child emotions were assessed via vignettes. Although this approach is common in the attribution literature and has the advantage of control over the types of child emotions of interest, it is hampered by reduced ecological validity (Miller, Citation1995). Even though we tried to increase ecological validity by using the child’s name in the vignettes, we do not know whether parents would react in the same way to these emotions in actual situations with their child. Future research could assess parental reactions and attributions of children’s emotions by using interview methods or by using situations that parents actually experienced with their children.

Fourth, due to an error in the online survey we have no information on the gender of the parent who completed the survey. Importantly, most available research on parental attributions that compared mothers and fathers found similarities in their attributions and its associations with parenting reactions and child problem behaviour (for a review see, Bugental & Corpuz, Citation2019; Miller, Citation1995; Park et al., Citation2018). Yet, future research needs to examine whether parental attributions of, and reactions to, children’s emotions are also more similar than different for mothers and fathers as well as for same-gender and other-gender parent–child dyads.

Finally, the study had a correlational design in which all constructs were assessed at a single point in time. As a consequence, we could not draw conclusions about the direction of effects with regard to child problem behaviour. Parental attributions and emotion-dismissing and -coaching reactions might not only have an effect on child problem behaviour, but child problems might also affect the attributions parents make and how they react to children’s problem behaviour. Longitudinal research is necessary to disentangle the direction of effects and to examine whether parental dispositional attributions and emotion-dismissing and -coaching reactions can explain the development of internalizing and externalizing problems over time.

Despite these limitations, the current study also has a number of strengths. First, little research has been done on parental attributions about children’s emotions. However, this study showed specifically these attributions have a direct and indirect effect on the internalizing and externalizing problems of the child. Second, the focus on moderated-mediation is a strength in this study. By not only investigating the mediating role of parents’ emotion-dismissing and -coaching reaction in the association between dispositional attributions and problem behaviour, but also examining the conditional effects for boys and girls, this provided a clearer picture of the intricate interplay of these variables than separate analyses would provide.

Implications for practice

There are multiple interventions that focus on parental emotion socialisation as a way to prevent or reduce child social-emotional problems (Havighurst & Kehoe, Citation2017; Lauw et al., Citation2014). A part of these interventions is aimed at the emotion regulation of parents and at the beliefs they have about emotions. This fits the idea of the parental meta-emotion philosophy, in which beliefs of parents about their own emotions and the emotions of their children influence parents’ emotion socialisation practices. However, the role of child gender is not mentioned at all in the literature on such interventions. For the interventions to be as effective as possible, it might be important to pay attention to the gender-specific ways in which the attributions parents have about boys’ and girls’ emotions are related to parents’ emotion socialisation strategies and children’s internalizing and externalizing problem behaviour.

Conclusion

The current study showed that the attributions parents make about the dispositional causes of their children’s internalizing and externalizing emotions play a role in children’s internalizing and externalizing problem behaviour. Yet, this effect of parental attributions is not only direct, but also indirect via parents’ emotion-dismissing reactions, and to a lesser extent via emotion-coaching reactions, toward children’s internalizing and externalizing problem behaviour. In addition, for boys the parental attribution process via emotion-dismissing reactions on internalizing problems seems to be more pronounced than for girls. Yet, for girls the parental attribution process via emotion-coaching reactions on internalizing problems seems to be more pronounced than for boys. These gender differences might reflect prevailing gender stereotypes about the expression of internalizing and internalizing emotions and problems. In order to foster children’s psychosocial adjustment, parents should be made aware of the often-unconscious attributions they make about their sons’ and daughters’ emotions.

Declaration of interest

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

supporting_information_final.docx

Download MS Word (902.5 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Achenbach, T. M. (1999). The child behavior checklist and related instruments. In M. E. Maruish (Ed.), The use of psychological testing for treatment planning and outcomes assessment (pp. 429–466). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

- Bailes, L. G., & Leerkes, E. M. (2021). Maternal personality predicts insensitive parenting: Effects through causal attributions about infant distress. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 72, 101222. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2020.101222

- Bariola, E., Gullone, E., & Hughes, E. K. (2011). Child and adolescent emotion regulation: The role of parental emotion regulation and expression. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 14(2), 198–212. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-011-0092-5

- Barrett, L. F., & Bliss-Moreau, E. (2009). She’s emotional. He’s having a bad day: Attributional explanations for emotion stereotypes. Emotion, 9(5), 649. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016821

- Blair, C., & Diamond, A. (2008). Biological processes in prevention and intervention: The promotion of self-regulation as a means of preventing school failure. Development and Psychopathology, 20(3), 899–911. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579408000436

- Bougher-Muckian, H. R., Root, A. E., Floyd, K. K., Coogle, C. G., & Hartman, S. (2019). The association between adaptive functioning and parents’ attributions for children’s emotions. Early Child Development and Care, 189(9), 1538–1552. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2017.1396979

- Brajsa-Zganec, A. (2014). Emocionalni život obitelji: roditeljske metaemocije, temperament djeteta i eksternalizirani i internalizirani problemi. Drustvena Istrazivanja, 23(1), 25–45. https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/emotional-life-family-parental-meta-emotions/docview/1540738684/se-2 https://doi.org/10.5559/di.23.1.02

- Brescoll, V. L., & Uhlmann, E. L. (2008). Can an angry woman get ahead? Psychological Science, 19(3), 268–275. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02079.x

- Brody, L. R. (1999). Gender, emotion, and the family. Harvard University Press. https://doi.org/10.4159/9780674028821

- Brody, L. R. (2000). Gender and emotion. Gender and Emotion: Social Psychological Perspectives, 2(11), 24–47. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511628191.003

- Brody, L. R., & Hall, J. A. (2008). Gender and emotion in context. In M. Lewis, J. M. Haviland-Jones, & L. F. Barrett (Eds.), Handbook of emotions (3rd ed., pp. 395–408). The Guilford Press.

- Bugental, D. B., & Corpuz, R. (2019). Parental attributions. In M. H. Bornstein (Ed.), Being and becoming a parent: Handbook of parenting (3rd ed., Vol. 3, pp. 722–761). Routledge. https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/e/9780429433214/chapters/10.43249780429433214-21.

- Bugental, D. B., Johnston, C., New, M., & Silvester, J. (1998). Measuring parental attributions: Conceptual and methodological issues. Journal of Family Psychology, 12(4), 459–480. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.12.4.459

- Chaplin, T. M. (2015). Gender and emotion expression: A developmental contextual perspective. Emotion Review, 7(1), 14–21. https://doi.org/10.1177/1754073914544408

- Chaplin, T. M., Cole, P. M., & Zahn-Waxler, C. (2005). Parental socialization of emotion expression: Gender differences and relations to child adjustment. Emotion, 5(1), 80–88. https://doi.org/10.1037/1528-3542.5.1.80

- Chen, M., Johnston, C., Sheeber, L., & Leve, C. (2009). Parent and adolescent depressive symptoms: The role of parental attributions. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 37(1), 119–130. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-008-9264-2

- Colalillo, S., Miller, N. V., & Johnston, C. (2015). Mother and father attributions for child misbehavior: Relations to child internalizing and externalizing problems. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 34(9), 788–808. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2015.34.9.788

- Corapci, F., Aksan, N., & Yagmurlu, B. (2012). Socialization of Turkish children’s emotions: Do different emotions elicit different responses? Global Studies of Childhood, 2(2), 106–116. https://doi.org/10.2304/gsch.2012.2.2.106

- Cunningham, J. N., Kliewer, W., & Garner, P. W. (2009). Emotion socialization, child emotion understanding and regulation, and adjustment in urban African American families: Differential associations across child gender. Development and Psychopathology, 21(1), 261–283. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579409000157

- Cyranowski, J. M., Frank, E., Young, E., & Shear, M. K. (2000). Adolescent onset of the gender difference in lifetime rates of major depression. Archives of General Psychiatry, 57(1), 21–27. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.57.1.21

- Denham, S. A., Bassett, H. H., & Wyatt, T. (2015). The socialization of emotional competence. In J. E. Grusec, & P. D. Hastings (Eds.), Handbook of socialization: Theory and research (pp. 590–613). The Guilford Press.

- Dix, T. H., & Grusec, J. E. (1985). Parent attribution processes in the socialization of children. In I. Siegel (Ed.), Parental belief systems: The psychological consequences for children (pp. 201–233). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Eisenberg, N., & Fabes, R. A. (1994). Mothers’ reactions to children’s negative emotions: Relations to children’s temperament and anger behavior. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 40, 138–156. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23087912.

- Eisenberg, N., Fabes, R. A., & Murphy, B. C. (1996). Parents’ reactions to children’s negative emotions: Relations to children’s social competence and comforting behavior. Child Development, 67(5), 2227–2247. https://doi.org/10.2307/1131620

- Eisenberg, N., Fabes, R. A., Shepard, S. A., Guthrie, I. K., Murphy, B. C., & Reiser, M. (1999). Parental reactions to children’s negative emotions: Longitudinal relations to quality of children’s social functioning. Child Development, 70(2), 513–534. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00037

- Engle, J. M., & McElwain, N. L. (2011). Parental reactions to toddlers’ negative emotions and child negative emotionality as correlates of problem behavior at the age of three. Social Development, 20(2), 251–271. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9507.2010.00583.x

- Fabes, R. A., Leonard, S. A., Kupanoff, K., & Martin, C. L. (2001). Parental coping with children's negative emotions: Relations with children's emotional and social responding. Child Development, 72(3), 907–920. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00323

- Gottman, J. M., Katz, L. F., & Hooven, C. (1996). Parental meta-emotion philosophy and the emotional life of families: Theoretical models and preliminary data. Journal of Family Psychology, 10(3), 243–268. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.10.3.243

- Graber, J. A. (2004). Internalizing problems during adolescence. In R. M. Lerner, & L. Steinberg (Eds.), Handbook of adolescent psychology (pp. 587–626). https://doi.org/10.1002/9780471726746.ch19

- Grady, J. S. (2020). Parents’ reactions to toddlers’ emotions: Relations with toddler shyness and gender. Early Child Development and Care, 190(12), 1855–1862. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2018.1543664

- Havighurst, S., & Kehoe, C. (2017). The role of parental emotion regulation in parents emotion socialization: Implications for intervention. In K. Deater-Deckard, & R. Panneton (Eds.), Parental stress and early child development (pp. 285–307). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-55376-4_12

- Havighurst, S. S., Wilson, K. R., Harley, A. E., Prior, M. R., & Kehoe, C. (2010). Tuning in to kids: Improving emotion socialization practices in parents of preschool children – findings from a community trial. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 51(12), 1342–1350. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02303.x

- Hayes, A. F. (2022). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach (3rd ed.).

- Huff, C., & Tingley, D. (2015). “Who are these people?” Evaluating the demographic characteristics and political preferences of MTurk survey respondents. Research & Politics, 2(3), 205316801560464–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053168015604648

- Johnson, A. M., Hawes, D. J., Eisenberg, N., Kohlhoff, J., & Dudeney, J. (2017). Emotion socialization and child conduct problems: A comprehensive review and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 54, 65–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2017.04.001

- Johnston, C., Hommersen, P., & Seipp, C. M. (2009). Maternal attributions and child oppositional behavior: A longitudinal study of boys with and without attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 77(1), 189–195. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014065

- Johnstone, K. M., Kemps, E., & Chen, J. (2018). A meta-analysis of universal school-based prevention programs for anxiety and depression in children. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 21(4), 466–481. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-018-0266-5

- Katz, L. F., Maliken, A. C., & Stettler, N. M. (2012). Parental meta-emotion philosophy: A review of research and theoretical framework. Child Development Perspectives, 6, 417–422. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1750-8606.2012.00244.x

- Kill, H., Aitken, M., Henry, S., Hoxha, O., Rodak, T., Bennett, K., & Andrade, B. F. (2021). Transdiagnostic associations among parental causal locus attributions, child behavior and psychosocial treatment outcomes: A systematic review. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 24(2), 267–293. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-020-00341-1

- Lauw, M. S. M., Havighurst, S. S., Wilson, K. R., Harley, A. E., & Northam, E. A. (2014). Improving parenting of toddlers’ emotions using an emotion coaching parenting program: A pilot study of tuning in to toddlers. Journal of Community Psychology, 42(2), 169–175. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.21602

- Lawrence, D., Johnson, S., Hafekost, J., Boterhoven de Haan, K., Sawyer, M., Ainley, J., & Zubrick, S. R. (2015). The mental health of children and adolescents: Report on the second Australian child and adolescent survey of mental health and welbeing. Department of Health. https://apo.org.au/sites/default/files/resource-files/2015-08/apo-nid56473.pdf.

- Leerkes, E. M., Su, J., Calkins, S. D., Supple, A. J., & O’Brien, M. (2016). Pathways by which mothers’ physiological arousal and regulation while caregiving predict sensitivity to infant distress. Journal of Family Psychology, 30(7), 769–779. https://doi.org/10.1037/fam0000185

- Leung, D. W., & Smith Slep, A. M. (2006). Predicting inept discipline: The role of parental depressive symptoms, anger, and attributions. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 74(3), 524–534. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.74.3.524

- Lewinsohn, P. M., Gotlib, I. H., Lewinsohn, M., Seeley, J. R., & Allen, N. B. (1998). Gender differences in anxiety disorders and anxiety symptoms in adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 107(1), 109–117. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.107.1.109

- Lunkenheimer, E. S., Shields, A. M., & Cortina, K. S. (2007). Parental emotion coaching and dismissing in family interaction. Social Development, 16(2), 232–248. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9507.2007.00382.x

- MacKinnon, D. P., Fairchild, A. J., & Fritz, M. S. (2007). Mediation analysis. Annual Review of Psychology, 58(1), 593–614. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085542

- Martin, J., Anderson, J. E., Groh, A. M., Waters, T. E., Young, E., Johnson, W. F., … Roisman, G. I. (2018). Maternal sensitivity during the first 3½ years of life predicts electrophysiological responding to and cognitive appraisals of infant crying at midlife. Developmental Psychology, 54(10), 1917–1927. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0000579

- McKee, L., Colletti, C., Rakow, A., Jones, D. J., & Forehand, R. (2008). Parenting and child externalizing behaviors: Are the associations specific or diffuse? Aggression and Violent Behavior, 13(3), 201–215. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2008.03.005

- Miller, S. A. (1995). Parents’ attributions for their children's behavior. Child Development, 66(6), 1557–1584. https://doi.org/10.2307/1131897

- Mills, R. S. L., & Rubin, K. H. (1990). Parental beliefs about problematic social behaviors in early childhood. Child Development, 61(1), 138–151. https://doi.org/10.2307/1131054

- Nakamura, B. J., Ebesutani, C., Bernstein, A., & Chorpita, B. F. (2009). A psychometric analysis of the Child Behavior Checklist DSM-oriented scales. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 31(3), 178–189. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10862-008-9119-8

- Ornaghi, V., Pepe, A., Agliati, A., & Grazzani, I. (2019). The contribution of emotion knowledge, language ability, and maternal emotion socialization style to explaining toddlers’ emotion regulation. Social Development, 28(3), 581–598. https://doi.org/10.1111/sode.12351

- Park, J. L., Johnston, C., Colalillo, S., & Williamson, D. (2018). Parents’ attributions for negative and positive child behavior in relation to parenting and child problems. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 47(sup1), S63–S75. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2016.1144191

- Polanczyk, G. V., Salum, G. A., Sugaya, L. S., Caye, A., & Rohde, L. A. (2015). Annual research review: A meta-analysis of the worldwide prevalence of mental disorders in children and adolescents. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 56(3), 345–365. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12381

- Racine, N., McArthur, B. A., Cooke, J. E., Eirich, R., Zhu, J., & Madigan, S. (2021). Global prevalence of depressive and anxiety symptoms in children and adolescents during COVID-19. JAMA Pediatrics, 175(11), 1142–1150. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.2482

- Rescorla, L., Achenbach, T., Ivanova, M. Y., Dumenci, L., Almqvist, F., Bilenberg, N., … Verhulst, F. (2007). Behavioral and emotional problems reported by parents of children ages 6 to 16 in 31 societies. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 15(3), 130–142. https://doi.org/10.1177/10634266070150030101

- Roberts, W. L. (1999). The socialization of emotional expression: Relations with prosocial behaviour and competence in five samples. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science / Revue Canadienne des Sciences du Comportement, 31(2), https://doi.org/10.1037/h0087075

- Root, K. A., & Rubin, K. H. (2010). Gender and parents’ reactions to children’s emotion during the preschool years. In A. Kennedy Root, & S. Denham (Eds.), The role of gender in the socialization of emotion: Key concepts and critical issues. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development (pp. 51–64). Jossey-Bass. https://doi.org/10.1002/cd.268

- Rothman, K. J., Greenland, S., & Lash, T. L. (2008). Modern epidemiology. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins.

- Scheider, J. L., & Weisz, J. R. (2017). Family process and youth internalizing problems: A triadic model of etiology and intervention. Development and Psychopathology, 29(1), 273–301. https://doi.org/10.1017/S095457941600016X

- Shaffer, A., Suveg, C., Thomassin, K., & Bradbury, L. L. (2012). Emotion socialization in the context of family risks: Links to child emotion regulation. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 21(6), 917–924. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-011-9551-3

- Sheeber, L. B., Johnston, C., Chen, M., Leve, C., Hops, H., & Davis, B. (2009). Mothers’ and fathers’ attributions for adolescent behavior: An examination in families of depressed, subdiagnostic and non-depressed youth. Journal of Family Psychology, 23(6), 871–881. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016758

- Shewark, E. A., & Blandon, A. Y. (2015). Mothers’ and fathers’ emotion socialization and children’s emotion regulation: A within-family model. Social Development, 24(2), 266–284. https://doi.org/10.1111/sode.12095

- Smith, M. (2011). Measures for assessing parenting in research and practice. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 16(3), 158–166. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-3588.2010.00585.x

- Sturge-Apple, M. L., Suor, J. H., & Skibo, M. A. (2014). Maternal child-centered attributions and harsh discipline: The moderating role of maternal working memory across socioeconomic contexts. Journal of Family Psychology, 28(5), 645–654. https://doi.org/10.1037/fam0000023

- Suh, B. L., & Kang, M. J. (2020). Maternal reactions to preschoolers’ negative emotions and aggression: Gender difference in mediation of emotion regulation. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 29(1), 144–154. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-019-01649-5

- Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2012). Using multivariate statistics (6th ed.). Harper Collins.

- Tao, A., Zhou, Q., & Wang, Y. (2010). Parental reactions to children’s negative emotions: Prospective relations to Chinese children’s psychological adjustment. Journal of Family Psychology, 24(2), 135–144. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018974

- Ugarte, E., Liu, S., & Hastings, P. D. (2021). Parasympathetic activity, emotion socialization and internalizing and externalizing problems in children: Longitudinal associations between and within families. Developmental Psychology, 57(9), 1525–1539. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0001039

- van der Pol, L. D., Groeneveld, M. G., van Berkel, S. R., Endendijk, J. J., Hallers-Haalboom, E. T., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., & Mesman, J. (2015). Fathers’ and mothers’ emotion talk with their girls and boys from toddlerhood to preschool age. Emotion, 15(6), 854. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000085

- Wagner, N. J., Gueron-Sela, N., Bedford, R., & Propper, C. (2018). Maternal attributions of infant behavior and parenting in toddlerhood predict teacher-rated internalizing problems in childhood. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 47(sup1), S569–S577. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2018.1477050

- Weinberg, M. K., Tronick, E. Z., Cohn, J. F., & Olson, K. L. (1999). Gender differences in emotional expressivity and self-regulation during early infancy. Developmental Psychology, 35(1), 175–188. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.35.1.175

- Weiner, B. (2010). Attribution theory. In P. Peterson, E. Baker, & B. McGraw (Eds.), International encyclopedia of education (vol. 6, pp. 558–563). Elsevier.

- Wilson, K. R., Havighurst, S. S., Kehoe, C., & Harley, A. E. (2016). Dads tuning In to kids: Preliminary evaluation of a fathers' parenting program. Family Relations, 65(4), 535–549. https://doi.org/10.1111/fare.12216

- Zahn-Waxler, C., Klimes-Dougan, B., & Slattery, M. J. (2000). Internalizing problems of childhood and adolescence: Prospects, pitfalls, and progress inunderstanding the development of anxiety and depression. Development and Psychopathology, 12(3), 443–466. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579400003102

- Zahn-Waxler, C., Shirtcliff, E. A., & Marceau, K. (2008). Disorders of childhood and adolescence: Gender and psychopathology. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 4(1), 275–303. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091358

- Zeman, J., Cassano, M., Perry-Parrish, C., & Sheri, S. (2006). Emotion regulation in children and adolescents. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics, 27(2), 155–168. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004703-200604000-00014

- Zeman, J., Perry-Parrish, C., & Cassano, M. (2010). Parent-child discussions of anger and sadness: The importance of parent and child gender during middle childhood. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 2010(128), 65–83. https://doi.org/10.1002/cd.269