ABSTRACT

Do people share their feelings of guilt with others and, if so, what are the reasons for doing this or not doing this? Even though the social sharing of negative emotional experiences, such as regret, has been extensively studied, not much is known about whether people share feelings of guilt and why. We report three studies exploring these questions. In Study 1, we re-analysed data about sharing guilt experiences posted on a social website called “Yahoo Answers”, and found that people share intrapersonal as well as interpersonal guilt experiences with others online. Study 2 found that the main motivations of sharing guilt (compared with the sharing of regret) were “venting”, “clarification and meaning”, and “gaining advice”. Study 3 found that people were more likely to share experiences of interpersonal guilt and more likely to keep experiences of intrapersonal guilt to themselves. Together, these studies contribute to a further understanding of the social sharing of the emotion guilt.

People often share their emotions with others, such as friends or partners. Sometimes people even publicly share their emotions online (e.g. via online reviews, blogs, or forums). The types of emotions that people share do not only encompass basic emotions, such as sadness, happiness, or anger, but also self-conscious emotions, such as regret, pride, and embarrassment (Feinberg et al., Citation2012; Summerville & Buchanan, Citation2014; Van Osch et al., Citation2016; Wetzer et al., Citation2007a, Citation2007b). This is why we think that we could expect people to also share their feelings of guilt. After all, guilt is a self-conscious emotion that is highly related to regret and that results from awareness of harm to others or violations of moral standards (Mandel, Citation2003; Zeelenberg & Breugelmans, Citation2008; Zhang, Zeelenberg, and Breugelmans, Citation2021a, Citation2021b). Interestingly, there is not much research examining the social sharing of guilt. Rimé et al. (Citation1998) found that guilt is shared much less frequently with others than emotions such as anger, sadness, and happiness. Less frequently does not mean that it is not shared at all. Also, we are not aware of any research explaining when or why people decide to share their guilt. This article presents three studies that address these questions concerning the social sharing of guilt.

The social sharing of emotions is generally conceptualised as one type of emotion regulation strategies that has been widely used in everyday life (Brans et al., Citation2013; Heiy & Cheavens, Citation2014). Emotion regulation varies between strategies focused on private experiences of the emotion (reappraisal) versus those focused on public expressions of emotion (e.g. suppression; Gross & John, Citation2003). Research on the regulation of the negative self-conscious emotion of guilt has mainly focused on how people use reappraisal to regulate guilt (Feinberg et al., Citation2020; Saintives & Lunardo, Citation2016). In addition, although considerable research has examined the psychological benefits of the social sharing of emotions, relatively little research has addressed how people use interpersonal emotion regulation strategies (such as sharing one’s experience with others) for guilt (Graham et al., Citation2008; Pauw et al., Citation2018; Rimé, Citation2007, Citation2009; Wetzer et al., Citation2007a).

Exploring the social sharing of guilt thus not only fills an important gap in the (interpersonal) emotion regulation literature, it also provides insight into a specific relational perspective of understanding guilt. Despite the lack of research on the social sharing of guilt, research has been examining the effects of communications of guilt (and other emotions) between two interdependent persons in, for example, negotiations or social exchange situations. In such situations, the expression of guilt may be instrumental to people in achieving their goals: communicating guilt in these cases could serve a strategic function. For example, researchers have studied the role of communicated guilt in negotiation (Van Kleef et al., Citation2006), trust games (Shore & Parkinson, Citation2018), and intergroup exchange (Shore et al., Citation2019). In these situations, the expression of guilt is typically linked to goals such as asking for forgiveness, repairing a relationship, or smoothening an interaction. This research on communicating guilt in interdependent situations does not address the questions whether and why people share their feelings of guilt with unrelated others, for example with third parties who are unaware of the event for which the guilt is expressed. Such sharing with third parties has been documented for many other emotions (e.g. Graham et al., Citation2008; Nils & Rimé, Citation2012). So, if people share their feelings of guilt in interdependent situations for “strategic” reasons, what would be the function of sharing their feelings of guilt with unrelated third parties? Before we answer this question, we first would like to elaborate on the question of whether people socially share guilt or not.

Do people socially share guilt with others?

In light of the finding that people are not likely to share their feelings of guilt (Rimé et al., Citation1998), it is interesting that a recent study found that people use anonymous internet forums as platforms to disclose actions they felt guilt over. More specifically, Levontin and Yom-Tov (Citation2017) collected data from an online question-and-answer forum called “Yahoo Answers” that allows people to post questions and to receive answers from others. They examined 437 questions that people posted online involving feelings of personal guilt. In their article, Levontin and Yom-Tov provided the following example to illustrate a guilt related question from Yahoo Answers:

Ladies or gentlemen have you ever while on a diet ever fallen of the wagon like eating something you shouldn’t of? I just eaten 4 chocolate digestives and now I feel guilty I have recently started going to the gym so thank god I can burn it off but I still feel guilty though anyone bee the same? (Levontin & Yom-Tov, Citation2017, p. 3)

We did not know whether all or most cases in Levontin and Yom-Tov (Citation2017) were about intrapersonal guilt. So, as the start of our research we examined whether people also shared interpersonal guilt by reanalysing the data collected by Levontin and Yom-Tov. For that we coded the descriptions of the guilt-related questions from Yahoo Answers as intrapersonal or interpersonal guilt. This would allow us to find out if both types of guilt are shared with others. This reanalysis is our Study 1, reported below.

Motivations for social sharing guilt and regret

In the study of Levontin and Yom-Tov (Citation2017), they did not directly examine the motivations for sharing guilt on the platform. We think that the motive of relieving guilt that was assumed by Levontin and Yom-Tov (Citation2017) is similar to the “venting” motive identified in other social sharing research (e.g. Graham et al., Citation2008; Pauw et al., Citation2018; Rimé, Citation2007, Citation2009; Wetzer et al., Citation2007a). Interestingly, social sharing research has documented more motives for the sharing of emotions with others. Duprez et al. (Citation2015) reviewed the literature and identified seven common motives for socially sharing emotions: (1) seeking assistance/support and comfort/consolation, (2) rehearsing and re-experiencing the episode, (3) venting, (4) seeking clarification and meaning, (5) informing and/or warning, (6) arousing empathy/attention, and (7) seeking advice and solutions. It is noteworthy that none of the studies that Duprez et al. reviewed included the emotion guilt. It is thus as yet unknown whether and how these seven motives apply to the sharing of guilt.

There are four motivations that we think are especially relevant for the sharing of guilt. First, people may share feelings of guilt simply to vent. Wetzer et al. (Citation2007a) examined the motivations of a range of negative emotions and found that “venting” was indicated to be the most relevant goal for sharing all of these emotions. Guilt was not included in their study, but regret was. Second, people may share feelings of guilt in order to obtain “advice and solution”. Guilt is felt after doing something wrong and associated with anxiety over social exclusion (Baumeister et al., Citation1994). Hearing other people’s opinions may help to transform a stressful event into a less threatening event. The third and fourth motivations that we propose are relevant for guilt were not included by Duprez et al. (Citation2015). We think that people may share feelings of guilt in order to “hear criticism” from the other. When people feel guilty, they typically feel responsible for the bad thing that happened. This can even lead to self-punishment when there is no opportunity to compensate the other person (e.g. Nelissen, Citation2012; Nelissen & Zeelenberg, Citation2009). Hearing criticism from others may be a form of self-punishment, also because it helps people to be fully aware of their mistakes. Fourth, people may share feelings of guilt in order to “get reassurance”.Footnote1 Feeling guilt comes from realising having done something wrong. People may hope to feel reassured by hearing about other’s similar experiences. If they know that others had similar experiences, they might feel better (either by “misery loves company” or by “being on the same page” as someone else).

We also explored the main motivations of sharing guilt with others by comparing it with sharing regret, one of the emotions closest to guilt. This comparison was chosen on the basis of past research (Berndsen et al., Citation2004; Zeelenberg & Breugelmans, Citation2008) addressing the role of intrapersonal and interpersonal harm in distinguishing guilt and regret. Specifically, guilt results primarily from interpersonal harm, whereas regret can result from both harm to oneself and harm to others (Zeelenberg & Breugelmans, Citation2008). How exactly this difference relates to motivations for sharing these emotions is still unclear. Therefore, we compared the motivations of sharing guilt with regret.

Some studies examined the main motivations of sharing regret (Wetzer et al., Citation2007a, Citation2007b), which were to warn others or to bond with them. Are these two motivations also main motivations for sharing guilt? The phenomenology of guilt (e.g. Breugelmans et al., Citation2014; Roseman et al., Citation1994) suggests that people who feel guilt tend to put their relationships first, suggesting that the main motivations of sharing guilt could be warning other people or bonding with others. Guilt, however, also represents something that people did wrong. If they share this with third parties, with whom they do not have a relationship to repair, they are running the risk of looking bad in the eyes of these others. The main motivations for sharing guilt in such cases may thus be more focused at oneself, removing their negative feeling or gaining advice. Bonding and warning others, the main motivations to share regret, do not serve this specific function. Thus, we expected that the motivations for sharing guilt could be different from those for sharing regret.

In line with these considerations, Study 2 mainly test the motivations of social sharing guilt and we proposed four main motivations (venting, advice and solution, getting assurance, hearing criticism) would be the top motivations for sharing guilt among other motivations. In addition, we also further examined whether people share different types of guilt and regret (interpersonal harm vs. intrapersonal harm) with different motivations.

Shared guilt vs. not shared guilt

Expressing emotions can elicit both favourable and unfavourable responses. For example, expressions of happiness were found to both help savour the moment and to elicit exploitation (Gable et al., Citation2004; Van Kleef et al., Citation2006). For expressing guilt, we think people are particularly worried about the unfavourable responses of others. Therefore, we are also interested in guilt experiences that were not shared and in why people chose to keep them inside. Specifically, we examined whether there are differences between the types of guilt (i.e. intrapersonal or interpersonal) that people share and the ones that they keep for themselves. We explore this for two reasons. First, we have argued that the type of guilt is both interesting and important for the knowledge about sharing guilt. It is interesting in the sense that it would be more likely for people to share experiences of intrapersonal guilt than those of interpersonal guilt. It is important in the sense that the type of guilt may influence people’s motivations. Second, some research show that interpersonal emotion regulation can also bring some undesirable outcomes. For example, Swerdlow et al. (Citation2023) found that people will experience shame for conducting interpersonal emotional regulations. Expressions of guilt with third-parties are more likely to meet with different types of harms. Therefore, it is particularly relevant to explore unshared guilt and reasons for this.

Study 3 was therefore the first to examine which type of guilt are kept inside and what are the reasons of doing this. In sum, we examined questions of whether people share interpersonal and intrapersonal guilt with others and what motivates people to (not) share guilt with others.

Study 1: reanalysis of Levontin and Yom-Tov’s (Citation2017) data.Footnote2

To examine whether people share interpersonal guilt experiences with third parties, we looked at both interpersonal and intrapersonal guilt (Berndsen et al., Citation2004; Zeelenberg & Breugelmans, Citation2008). Interpersonal guilt comes from harming other people, and intrapersonal guilt comes from harming oneself. Levontin and Yom-Tov (Citation2017) collected 1014 questionsFootnote3 from the online question-and-answer website Yahoo Answers that included the term “guilt” (the words “guilt” and “guilty”). They kindly shared their data with us, allowing us to inspect the descriptions and code them as being about intrapersonal or interpersonal guilt.

Two judges independently coded all the questions (N = 1014) as explained below (N = 1014, initial Cohen’s Kappa = .79); they subsequently discussed cases where classification differed, resulting in all final codes being in agreement. Each of the 1014 questions contained two parts: the title of the question, and its content. In order to make sure we only included cases in which askers on the online forum experienced guilt themselves, the data were coded according to the following rules: (1) We removed 579 cases (57.10%) where the term “guilt” did not reflect a feeling of guilt (for example, “according to tv network there is a policy that reduces your fine by 50% if you plead guilty”.); (2) We removed another 41 cases (4%) where the question was about other people’s guilt (for example, “ … my boyfriend confessed to kissing a random girl in a nightclub … we had been together 18 months and were very happy, and he told me after due to guilt … ”); (3) The remaining 394 casesFootnote4 (38.86%) were coded for whether people talked about interpersonal guilt (270 out of 394 cases = 68.52%; e.g. cheating while being in a relationship, or treating a family member badly), or intrapersonal guilt (124 out of 394 cases = 31.48%; e.g. gaining weight, or masturbation); this was a significant difference, z = 7.30, p < .001.

Thus, people shared both experiences of intrapersonal and of interpersonal guilt experience with unknown others at this online forum, and the number of interpersonal guilt experiences was about twice as high as that of the intrapersonal guilt experiences. Note that starting this research, we expected the opposite, namely that people would be more likely to share experiences of intrapersonal guilt. Of course, these data do not really allow us to examine the likelihood of sharing interpersonal and intrapersonal guilt, so we do not know if these findings reflect that experiences of interpersonal guilt are shared more often, or that they simply are more prevalent. Zeelenberg and Breugelmans (Citation2008; Study 3) also reported more cases of guilt from interpersonal harm than from intrapersonal harm, so it could be that interpersonal guilt is simply more prevalent, perhaps because it is also the more prototypical type of guilt.

In addition, we note that the function of this online forum (Yahoo Answers) is for people to ask questions and to get answers from others. Thus, people shared their experiences of guilt in order to ask other people’s opinions about it. Levontin and Yom-Tov (Citation2017) did not examine the motives for sharing guilt directly and assumed that people share in order to relieve guilt. It remains unknown whether this was indeed people’s reason for sharing their experience of guilt online, or whether other reasons spurred them to do so. Furthermore, the way online fora are set up differs in many ways from how in academic studies ask people about their sharing of guilt experiences. The online reported experiences may be more spontaneous and self-initiated than the ones obtained in academic research, which may be more reflective and deliberative. In the following studies, we further examine the sharing of guilt and the motivations underlying the sharing of this emotion.

Study 2

This study examined the different motivations underlying the sharing of experiences of guilt (preregistered at https://aspredicted.org/blind.php?x = md5f3b). We were thus interested in why people would decide to share their guilt. A second goal of Study 2 was to explore whether there are different motives of sharing interpersonal and intrapersonal experience guilt (and regret). We had specific hypotheses concerning the motivations for sharing inter/intrapersonal experience guilt and regret. Wetzer et al. (Citation2007a, Citation2007b) found that people share regret to warn others and to bond with them. We predicted that warning others is stronger for sharing intrapersonal than interpersonal regret. Because in the situations of interpersonal harm the phenomenology of regret shares many features with the phenomenology of guilt (Zeelenberg & Breugelmans, Citation2008), the motivation of sharing interpersonal regret is expected to be similar that of sharing guilt. Therefore, we expect that people who share interpersonal regret may have other more motivations than warning others, such as gaining advice.

We also had specific predictions for interpersonal and intrapersonal guilt. Earlier we argued that there are four main motivations for sharing guilt: venting, advice/solution, hearing criticism, and getting assurance. We expected that the motivation of gaining outside perspectives (such as gaining “advice and solution”) would be stronger for sharing interpersonal than intrapersonal guilt. The motivation of “venting” was expected to be stronger for sharing intrapersonal than interpersonal guilt. We did not expect the two types of guilt does to differ on the motivations of hearing criticism and getting assurance.

Summarising the above, we examined how 10 motivations for sharing emotions relate to the sharing of interpersonal and intrapersonal guilt and regret. Seven of these motivations come from the review of Duprez et al. (Citation2015). The other three were added specifically for finding out the main motivations for sharing guilt.

Method

Participants

An a-priori sample size calculation with G*Power for an MANOVA with two conditions and 10 DVs (95% power, α = .05, and η2p = .06), indicated 416 participants. We decided to oversample to 430 take account of potential data exclusions. In total, 498 participants from MTurkFootnote5 took part in the study to exchange for a small payment ($0.30). Out of 243 participants in the guilt condition, 52 mentioned that they did not have an experience of sharing guilt with others, and four others did not complete the whole questionnaire; out of 253 participants in the regret condition, 36 mentioned that they did not have an experience of sharing regret with others, and three others did not complete the whole questionnaire. These participants were excluded from further analysis. The final sample consisted of 401 participants (241 females, Mage = 39.55, SD = 12.82).

Materials and procedure

Participants were randomly assigned to one of the two conditions (guilt vs. regret). They answered the following questions in the guilt (regret) condition: “We ask you to look back on your life. Have you ever shared feelings of guilt (regret) with some other person, who was not involved in the event?” [Yes/ No], “If yes, please think about this guilt (regret) experience and recall what you felt guilty (regret) about. Next, please answer the following questions. Did you feel guilt (regret) mostly because of negative outcome for yourself, or for someone else?” [Yourself/Someone else]. This latter sentence allowed us to classify the experiences of guilt and regret as intrapersonal or interpersonal (see Breugelmans et al., Citation2014), and to explore the relationship between two emotions and two types of harm. Then, participants were asked: “With whom did you share your experience? (Partner/Friend/Family member, Relative/Acquaintance/Stranger/Colleague/Therapist) You can indicate more than one person, if you talked to multiple people”. This question, commonly used in studies about social sharing, helps participants to reexperience or reactivate of emotional episode before answering the study questionnaire (Rimé et al., Citation1991).

Participants then filled out a questionnaire of 10 potential motivations for sharing their emotions (20 items in total, two for each motivation). These items were taken from Duprez et al. (Citation2015) and Wetzer et al. (Citation2007a). Participants indicated to what extent they agreed with items beginning with “I shared my experience of guilt/regret with others in order to … ” (e.g. “be supported”, “get it off my chest”, “be criticized”) on a scale from 1 (not at all) to 7 (very much). After this, we included an open-ended question (“If you shared your experience for another reason, please indicate that reason below”.) to see whether there were other motivations of sharing their emotion.

Results

With whom did people share and what?

Participants indicated with whom they shared their emotions. The number of social sharing partners (they could indicate more than one) amounted to one or two in 89.79% of cases (n = 401), three to four in 8.72% of cases, and five or more in 1.49% of cases. The social sharing partners in the guilt condition (n = 263) were most often a friend (37.26% of cases; family member, relative: 19.77%, partner: 18.25%, colleague: 7.60%, therapist: 7.22%, acquaintance: 6.46%, and stranger: 3.42%). The social sharing partners in the regret condition (n = 336) were also most often a friend (38.39% of cases; family member, relative: 21.42%, partner: 18.45%, therapist: 11.30%, colleague: 4.46%, acquaintance: 3.86% and stranger: 2.08%). We explored whether people shared guilt and regret with sharing partners, which was not the case, χ2 (N = 599) = 7.29, p = .295.

We found that there were more cases of interpersonal guilt (n = 123) than of intrapersonal guilt (n = 64), which is consistent with Study 1. For regret we found the opposite, more cases of intrapersonal (n = 132) than interpersonal regret (n = 82), which is consistent with the findings of Zeelenberg and Breugelmans (Citation2008).

Which social sharing motives are strongest?

A confirmatory factor analysis on the motivation items using the lavaan package (Rosseel, Citation2012) in R (R Core Team, Citation2018) showed a good model fit, χ2 (125) = 296.66, p < .001; Comparative Fit Index (CFI) = 0.95, Tucker-Lewis index (TLI) = 0.92; Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) = 0.059 [.05, .067] for a model with ten distinct motivations. We then compared the nine-factor model that combined “Get reassurance” and “Hear criticism” as one factor alongside other nine motivation factors: χ2 (134) = 448.03, p < .001; CFI = 0.90, TLI = 0.86; RMSEA = 0.076 [.069, .084]. Another eight-factor model that combined “Assistance, supports and comfort/consolation” and “Get reassurance” as one factor and combined “Clarification/meaning” and “Advice/Solutions” as another factor alongside other motivation factors: χ2 (149) = 671.84, p < .001; CFI = 0.84, TLI = 0.8; RMSEA = 0.09 [.08, .010]. Based on fit statistics (CFI > .95, TLI > .95, and RMSEA < .06), both the eight-factors model and the nine-factor model perform worse than the ten-factor model (Hu & Bentler, Citation1999; Tucker & Lewis, Citation1973).

We used the Spearman-Brown coefficient to assess reliability for all scales that consisted of only two items (cf. Eisinga et al., Citation2013). We averaged scores on relevant items to create composite measures of motivation of “assistance, support and comfort/consolation” (ρ = .74), “rehearsing” (ρ = .69), “venting” (ρ = .77), “clarification/meaning” (ρ = .75), “informing and/or warning” (ρ = .54), “arousing empathy/attention” (ρ = .70), “advice and solutions” (ρ = .70), “hearing criticism” (ρ = .64), “getting reassurance” (ρ = .55), and “bonding” (ρ = .85). The coefficients for each subscale were acceptable indicators of the reliability (also see Napoli et al., Citation2014).

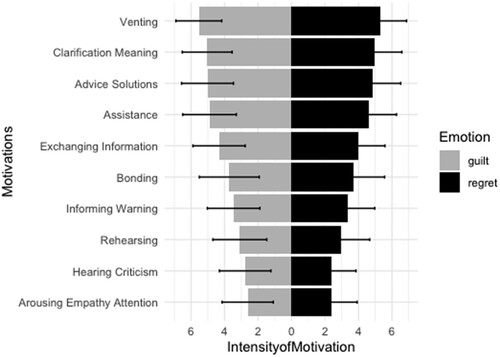

Our first hypothesis was that the motivations of “venting”, “advice/solutions”, “hearing criticism” and “getting assurance” were more likely to be the main motivations of sharing guilt than the other six motivations. To test this prediction, planned pairwise contrasts of motivations showed that, overall, “venting”, “clarification/meaning”, “advice/solutions” and “assistance, support and comfort/consolation” were the top four motivations for sharing guilt (see and ). Here, the motivations of “hearing criticism” and “getting assurance” were not very strong when sharing guilt with third parties. We also observed a similar pattern for the ranking of motivations for sharing regret.

Figure 1. Intensity of different motivations within sharing guilt/regret condition (Types of motivations ordered from high to low according to average scores).

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of motivations for both emotion conditions and correlation coefficients (Pearson’s r) among motivations of social sharing scales.

Do people share interpersonal and intrapersonal guilt/regret for different motivations?

We predicted that people would have different motivations for sharing interpersonal and intrapersonal guilt and regret. In order to examine this hypothesis, a 2 (Emotion: Guilt vs. Regret) × 2 (Harm: Interpersonal vs Intrapersonal) MANOVA with the 10 motivations as DVs was conducted. The analysis showed a main effect for Emotion, Wilks’ Lambda = 0.948, F (10, 388) = 2.14, p = .021, η2 = .052, and an Emotion × Harm interaction, Wilks’ Lambda = 0.949, F (10, 388) = 2.10, p = .023, η2 = .051. The significant main effect for Emotion supported our predictions. More specifically, univariate tests found that the motivations of “assistance, support and comfort” (p = .025, η2 = .013), “venting” (p = .023, η2 = .013), “arousing empathy/attention” (p = .020, η2 = .014) and “hearing criticism” (p = .003, η2 = .022) and “getting assurance” (p = .015, η2 = .015) scored higher when sharing guilt than when sharing regret (see for F values).

Table 2. ANOVA results and descriptive statistics of 10 motives for social sharing items for each type of emotion condition in study 2.

The univariate analyses also showed interaction effects for the motivations “clarification/meaning” (p = .013, η2 = .02), “arousing empathy/attention” (p = .014, η2 = .01) and “hearing criticism” (p = .002, η2 = .02) (see ). Specifically, for guilt, participants scored higher on these three motivations with respect to sharing intrapersonal guilt compared to interpersonal guilt, conversely, participants in the regret condition scored higher on these three motivations for sharing interpersonal than intrapersonal regret.

We next examined whether the motivations for sharing guilt or regret were also associated with the type of harm (inter- vs intrapersonal). To do this, we conducted a one-way MANOVA with harm as a between-subjects factor for guilt and for regret separately. In the guilt condition, we found a main effect of type of harm across the motivations, Wilks’ Lambda = 0.882, F (10, 176) = 2.34, p = .013, η2 = .118. Univariate tests found that people who shared intrapersonal guilt had stronger motivations of “gaining assistance, support and comfort”, F (1, 185) = 5.92, p = .016, η2 = .031, “rehearsing”, F (1, 185) = 4.86, p = .029, η2 = .026, “venting”, F (1, 185) = 4.78, p = .03, η2 = .025, “arousing empathy”, F (1, 185) = 11.16, p = .001, η2 = .057, and “hearing criticism”, F (1, 185) = 8.26, p = .005, η2 = .043, from others than those who shared interpersonal guilt. For regret, we did not find a main effect of type of harm, Wilks’ Lambda = 0.928, F (10, 203) = 1.56, p = .118. Univariate tests also did not show any significant difference among specific motivations.

Discussion

We examined the motivations for sharing guilt and regret. In general, the strongest motivations for sharing guilt and regret were “venting”, “clarification and meaning”, “gaining advice/solutions”, and “gaining assistance, support”. In addition, we did not find that the motivations “getting reassurance” and “hearing criticism” from others were very strong when sharing guilt with others, but we found that these two motivations were significantly higher for sharing guilt than for regret (see ). This result is in line with Duprez et al. (Citation2015), who also found that when comparing with sharing positive experiences, negative experiences were more frequently shared for the purpose of these four motivations. Although guilt stems from violating social norms or hurting others, which is different from most other negative emotions, such as anger, sadness and anxious, the motivations for sharing guilt are not different from these emotions.

Second, we examined whether people share guilt and regret for different motivations. Overall, although the pattern of rankings of motivation within guilt or regret are similar, some motivations for sharing guilt were significantly stronger than for sharing regret. In contrast to our predictions, we did not find significant differences for the motivations of “warning others” or “bonding with them”. Specifically, we found that people who shared guilt with others had a stronger hope of getting others’ opinions compared with those who shared regret, and those opinions include both positive comfort (motives of “assistance, support and comfort” and motive of “arousing empathy/attention”) and negative criticism (“hearing criticism”). Also, they had a stronger motivation of “venting” than those who shared regret. To sum up, the categories of motivations typical for sharing guilt and regret are mostly the same, but there are differences in the intensity of those motivations.

Third, we examined whether different motivations for sharing were associated with interpersonal/intrapersonal guilt or regret. For regret, we found that the type of harm did not influence the motives of sharing regret. For guilt, we found that although people shared more interpersonal than intrapersonal guilt experiences, the strength of motives for sharing intrapersonal guilt is stronger than for sharing interpersonal guilt.

Study 3

Studies 1 and 2 found that people do share guilt experiences and that the motivations for doing so are slightly different for interpersonal and intrapersonal guilt. However, there are also experiences of guilt that have not been shared with others, and as to yet, we have no insight into these. The aim of Study 3 is to compare shared and unshared guilt experiences, in order to examine whether intrapersonal guilt experiences are overrepresented in the ones that are shared. Moreover, we also measured how guilty people felt about shared versus unshared experiences. This allowed us to explore whether choosing to share or not to share a guilt-related experience is related to the intensity of the guilt. This study was preregistered via AsPredicted as https://aspredicted.org/blind.php?x = ay7vk9.

Method

Participants

Four hundred participants were recruited from MTurk in exchange for payment ($0.30). We determined sample size with G*Power for a Proportions z test, which indicated that for an 80% power, with α = .05, p1 = .34 (in Study 2 we had 123 interpersonal and 64 intrapersonal guilt experiences), p2 = .50 (we chose this because we do not know the proportion of the types of harm when they are unshared), we needed 298 participants. We oversampled to 400 participants because a substantial number of participants in Study 2 indicated not to have shared any guilt experience. Four hundred and sixty-eight participants participated in the study,Footnote6 of whom 34 in the Not Shared condition and 42 in Shared condition indicated that they could not remember the experience we asked for. One participant did not fill out the whole questionnaire. These participants were excluded from further analysis, leaving 391 participants (Mage = 39.48, SD = 11.73, 194 females) who completed the entire study.

Materials and procedure

Participants were randomly assigned to one of two conditions (Shared guilt or Unshared guilt). Participants were asked to answer the following questions (Unshared guilt condition is in parentheses):

There are kinds of feelings people tend (not) to share it with others. We would like to know whether at any point in time if you have shared feelings of guilt with other people, who was not involved in the event (if you have kept feelings of guilt inside and did not talk about it with other people). [Yes, No]

If yes, please think about this guilt experience and recall what you felt guilty about. Next please answer the following questions. Did you feel guilt mostly because of negative outcome for yourself, or for someone else? [Yourself/Someone else]

How much guilt did you feel about the experience? (1 = not at all, 7 = very much)

What is the reason or are the reasons for (not) sharing your guilt feelings with others? Please list as many as you can think of, and be as specific as you can without feeling that you are compromising your anonymity.

Results and discussion

The proportion of interpersonal and intrapersonal guilt shared or not

We expected that people are more likely to share intrapersonal guilt experiences than interpersonal guilt experiences and that they prefer to keep the interpersonal guilt experiences away from others. Overall, we found a significant association between the type of guilt and whether it was shared or not, χ2(N = 391) = 14.49, p < .001, φ = 0.19. There were no significant differences in the Shared Condition: we found 96 (51.34%) interpersonal guilt experiences and 91 (48.66%) intrapersonal guilt experiences, χ2 (N = 187) = 0.134, p = .71. Here, we thus found that the difference between interpersonal guilt experiences and intrapersonal guilt experiences was substantially smaller than it was in the Studies 1 and 2 (Study 1: 270 interpersonal guilt vs. 124 intrapersonal guilt; Study 2: 123 interpersonal guilt vs. 64 intrapersonal guilt). We have no explanation for why that is the case. There were significant differences in the Unshared Condition: we found 66 (32.35%) interpersonal guilt experiences and 138 (67.65%) intrapersonal guilt experiences, χ2 (N = 204) = 25.41, p < .001, φ = 0.35. The pattern of results was opposite to what we expected.

Reasons for sharing guilt

Participants in the Shared and Unshared conditions were asked to write their reasons for (not) sharing. We wanted to explore whether we could replicate the results of the rankings of motivations for sharing guilt of Study 2.Footnote7 The first author read all answers and coded these answers into the ten categories of motivations from Study 2 for sharing emotions. Forty-three participants wrote only about the guilt experiences and not about the motivations for sharing guilt with others. These were excluded from further analyses, leaving a final sample of 145. Overall, participants described 201 motivations, which is an average of 1.38 motivations per participant.

Consistent with Study 2, the majority of participants (n = 84; 41.79%) indicated that venting was the motivation for sharing their guilt. The second most frequently mentioned motivation was clarification/meaning (n = 33; 16.41%), the third was to get support and consolation from others (n = 19; 9.45%; get reassurance with others, n = 13; 6.46%; get advice from others, n = 12; 5.97%; to bond with others, n = 10; 4.97%; to inform/warn others n = 8; 3.98%). Few participants mentioned other motivations, for example, participants sharing guilt with others because it was part of a “group event”, or of a “religious tradition”. One participant wrote that it is “coping mechanism”.

Reasons for not sharing guilt

We excluded 19 participants who did not write motivations for not sharing guilt, leaving a final sample of 187. Overall, participants described 207 motivations of keeping guilt inside, or an average of 1.10 per participant. The two most mentioned reasons for keeping the guilt inside were that people “do not want to look bad” (n = 35; 16.90%) or that they were “too embarrassed or ashamed of the experiences to share it” (n = 35; 16.90%). The third most frequent was being afraid that sharing it would make the situation worse (e.g. “lose trust”, “lose relationship”, n = 34; 16.42%; not wanting to be “judged by others”, n = 27; 13.04%; not wanting to “bring burden on others”, n = 27; 13.04%; “it is private”, n = 16; 7.72%). Other, less often mentioned reasons were that people did not know “how to share it” or they thought “sharing the guilt is useless”.

We also explored whether there were differences of intensity of guilt in different conditions. A two-way ANOVA with the Shared/Unshared condition and types of harm as between-subjects factors and the intensity of guilt as dependent variable only showed a main effect of Shared/Unshared condition, F (1, 387) = 5.21, p = .02, η2 = 0.13. Specifically, we found that participants in the Unshared condition felt stronger guilt (M = 5.70, SD = 1.15) than participants in Shared condition (M = 5.45, SD = 1.24). There was no main effect of the types of harm, F (1, 387) = 1.54, p = .21, nor an interaction effect, F (1, 387) = 0.24, p = .61.

General discussion

In three studies we aimed to answer three questions: do people share guilt with third parties? If so, why do they do that? And what can we learn from comparing shared experiences of guilt with non-shared experiences? Study 1 reanalysed Levontin and Yom-Tov’s (Citation2017) data to examine what type of guilt people shared with third-party. We found that people share both interpersonal and intrapersonal guilt with others. Study 2 (N = 401) further explored and compared the motivations for sharing guilt and regret with other people and found that the main motivations for sharing guilt and regret were “venting”, “clarification and meaning”, and “gaining advice”. Study 3 (N = 391) further examined whether the ratio of sharing interpersonal and intrapersonal guilt could be different in the situation of shared and unshared guilt experience. We found that people shared more interpersonal guilt and kept intrapersonal guilt more to themselves.

We believe that the answer to the first question, namely that people do share feelings of guilt, is especially interesting in relation of previous research on the social sharing of emotions. For example, Finkenauer and Rimé (Citation1998) found that of all emotions, people were least likely to share feelings of guilt. Perhaps, one reason for the observed difference is our studies being conducted more than two decades after those of Finkenauer and Rimé. Nowadays dedicated online websites or social media platforms for anonymously sharing emotions, including guilt are readily available. On the other hand, we did find that friends, family members and partners were among the people whom people most often shared their guilt with, so the existence of the online opportunities for sharing are unlikely to be the full explanation. The finding that people do share guilt with third parties is important for social sharing related research, because most of this research has, until now, not included guilt (e.g. Pauw et al., Citation2018; Rimé et al., Citation1991). Research including guilt mostly focused on strategic sharing between transgressor and victims. Our findings suggest that guilt is shared outside of these interactions as well.

With regard to the second question about the reasons why people would share their experiences of guilt with others, we found results that are consistent with the general literature of emotional regulation. This literature indicates that people who share negative emotions are in need of cognitive and emotional assistance to gain control over this emotion (down regulation; Gross & Thompson, Citation2007). In line with this idea, we found that people sharing guilt were motivated most by “venting”, “getting clarification/meaning”, “gaining advice/solutions” and “assistance, support and comfort”. In contrast to our expectations, sharing guilt appeared to be less motivated by “getting reassurance”, and “hearing others’ criticism”. The reason we predict these two motivations is because that we argue guilt is different from other negative emotions (anger, sad, or disappointment) on the basis that it is felt when people did bad behaviours. Therefore, when people share this emotion with others, we assume the motivations for sharing guilt should also be different from other negative emotions. However, our results found that motivations for sharing guilt are similar with the motivations for sharing other negative emotions. This suggests that the valence of emotion is important for the motivations for sharing emotion, more than the specifics of the different emotions.

Of these findings, we found getting clarification/meaning as the second most frequent motivation for sharing. It seems that people sharing guilt with others appear to want to analyse the experience and gain an outsider’s perspective, suggesting that they might not be sure whether and to what extent they should feel guilty or not. We think that this motivation is very similar to reappraisal, referring to emotion regulation by a change in the cognitions about the situation, altering its meaning in order to influence its emotional impact (Gross & John, Citation2003). This shows a hitherto unexplored aspect of expressing guilt. As we stated before, previous research of guilt expression mainly explored the relationship between perpetrators and victims and that research found that people express guilt to ask for forgiveness. We, however, find that when people share guilt with third parties, they also seem to do that in order to find out if they actually should feel guilty. It thus seems that people want to calibrate their emotions through communication with others.

Finally, regarding the comparison of shared and unshared guilt experiences, we found that people keep intrapersonal guilt experiences more to themselves. This was contrary to the expectation that people would share interpersonal guilt experiences more because it might reflect worse on oneself. We can thus only speculate on why this is the case. It could be that cases of interpersonal guilt tend to be more amenable to reappraisal as was discussed before and thus that the benefits of sharing are larger than the potential costs. The findings from Study 3 suggest that people kept feelings of guilt inside because they did not want to look bad and be judged by others. This points to a more general point, namely that when studying social sharing of emotion, it is important to focus on both the expected benefits and the costs, especially for moral emotions such as guilt, that often involve undesirable behaviour. We believe that this is an important addition to previous research which mainly focused on the perceived benefits of sharing emotions (Rimé, Citation2009; Zech & Rimé, Citation2005).

In addition to the literature on social sharing, our research also sheds some light on the relationship between guilt and regret. Do people share guilt and regret feeling with different motivations? We found the rank order of motivations within guilt and regret were similar, but also that the strength of motives for sharing guilt and regret were different. The mean values of some motives (“assistance, support and comfort”, “getting reassurance”, “venting”, and “hearing criticism”) for sharing guilt were stronger than those for sharing regret. Previous research has found similarities and differences between guilt and regret with regard to the type of harm (Zeelenberg & Breugelmans, Citation2008) or associated self-discrepancies (Zhang, Zeelenberg, & Breugelmans, Citation2021a), and this line of research provided a new perspective of comparing these two emotions. That is, we found that people share guilt and regret with similar motives even though these emotions are experienced differently in some situations. In other words, even though the antecedents of guilt and regret may differ, the consequences for social sharing are very much the same.

Future research may want to address the limitations in the present research. First, emotions are dynamic processes that unfold over time, rather than momentary incidents (Eaton & Funder, Citation2001). We used self-report measures in Study 2 and 3 to examine the motivations of sharing guilt. Because reports on social sharing are always based on individual’s recollection of events, we felt that this approach was best for addressing the research questions. Future research could use experience sampling (Larson & Csikszentmihalyi, Citation1983) to study whether similar results are found and to further explore how sharing guilt with a third party influences the feeling of guilt. Do these disappear immediately after sharing or do they linger on? Similarly, how do people feel after sharing? Additional studies are also needed to address the consequences of sharing to provide a more complete picture of the process of interpersonal emotion regulation.

In addition, Studies 2 and 3 specially focused on the sharing of guilt and regret from an interpersonal/intrapersonal perspective. Whether an emotion is shared also depends on specific, situational features that afford or constrain the possibilities of sharing beyond the motivations for doing so embedded in the emotion. For example, whether different appraisals of guilt/regret and event characteristics might yield different effects on motivations of sharing, such as perceived control of the events, publicity of the event, or follow-up actions of the events (Roseman, Citation2013). Interestingly, appraisals of the situation and emotion-related appraisals may also overlap (cf. Tekoppele et al., Citation2023), so that the same situational features affect both the emotional experience and the perceived coping potential. It would seem very fruitful to further explore such relationships in future research on social sharing of specific emotions.

Second, this research was conducted in a Western cultural context, where emotional expression is generally encouraged. It will be important to see if the same motivations for sharing guilt are relevant for people from other cultural contexts. This is not only because in many East Asian cultures emotional expression is discouraged, but also because some of the antecedents of guilt may differ across cultures (Breugelmans et al., Citation2014). For example, Breugelmans et al. found that feelings of guilt are mostly associated with interpersonal harm in a U.S.A. sample, while it was equally associated with interpersonal and intrapersonal harm in a Taiwanese sample. Our Study 2 found that people shared interpersonal and intrapersonal guilt with different motivations; motivations such as “venting”, “gaining support” and “hearing criticism” were stronger for sharing intrapersonal guilt are stronger than interpersonal guilt. It would be interesting to see whether this means that such motivations would also be stronger in the Taiwan compared to the U.S.A.

Third, participants for Studies 2 and 3 were recruited from the Amazon MTurk platform. We found that a small proportion of participants in Study 3 misreported in response to the open-ended question. They wrote about the guilt experience itself rather than about the motivations for sharing guilt or keeping it inside. Recently, there has been some criticism about the use of online platforms for data collection, raising concerns about the quality of the data acquired by these methods. For example, Goodman et al. (Citation2013) found that online participants were less attentive to experimental materials than participants recruited in more traditional ways. On the other hand, several other studies have not found such results, or even the opposite. For instance, Necka et al. (Citation2016) found that, although online participants may engage in undesirable respondent behaviours, they do not do so more frequently than participants recruited by other means. From a series of three studies, Hauser and Schwarz (Citation2016) even concluded online participants tend to be “more attentive to instructions than … college students”. In short, there are no strong reasons to a priori doubt the validity of our data based on the recruitment methods. However, we would recommend that future research to recruit participants from different sources in order to corroborate the generalisability and replicability of our results.

Given the lack of research concerning the social sharing of guilt and the prevalence of sharing platforms in the current Internet age, it is important to learn more about how and why people share their feeling of guilt and about what the consequences are of this behaviour. We present three studies as a first in-depth exploration of social sharing of guilt with third parties. We find that although guilt mainly comes from feeling responsible for personal wrongdoings, people share both interpersonal and intrapersonal guilt with others. We also find that people share their feelings of guilt with others to vent and receive support and advice from others.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Acknowledgement

We thank Liat Levontin for sharing the data from Levontin and Yom-Tov (Citation2017) with us.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Note that in the preregistration of this study, we named this motivation as to “exchange information”. We think “get reassurance” fits better with the meaning of items that we used to measure this motivation, that is why we use that term here.

2 All data and materials reported in this article can be found at the Open Science Framework, via: https://osf.io/t2×4m/?view_only = 88f9dac37ca9400abd6e97b367449075

3 Note that this is more than double of the 437 questions that were analyzed in their paper. A large number of these 1014 questions turned out not to be informative for their research.

4 The final analysis of Levontin and Yom-Tov (Citation2017) includes cases that address other people’s guilt as well. This is why they examined more cases than we do here.

5 Note that initial sample size was larger than the requested sample size because MTurk detects when the total time participants spent on the questionnaire is much shorter than expected. In this case new participants are automatically recruited, leading to a total sample larger than the requested sample.

6 See Endnote 4 on why the sample is larger than requested.

7 This text analysis is exploratory and not preregistered.

References

- Baumeister, R. F., Stillwell, A. M., & Heatherton, T. F. (1994). Guilt: an interpersonal approach. Psychological Bulletin, 115(2), 243–267.

- Berndsen, M., Van der Pligt, J., Doosje, B., & Manstead, A. S. R. (2004). Guilt and regret: The determining role of interpersonal and intrapersonal harm. Cognition & Emotion, 18(1), 55–70. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699930244000435

- Brans, K., Koval, P., Verduyn, P., Lim, Y. L., & Kuppens, P. (2013). The regulation of negative and positive affect in daily life. Emotion, 13(5), 926–939. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032400

- Breugelmans, S. M., Zeelenberg, M., Gilovich, T., Huang, W. H., & Shani, Y. (2014). Generality and cultural variation in the experience of regret. Emotion, 14(6), 1037–1048. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038221

- Duprez, C., Christophe, V., Rimé, B., Congard, A., & Antoine, P. (2015). Motives for the social sharing of an emotional experience. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 32(6), 757–787. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407514548393

- Eaton, L. G., & Funder, D. C. (2001). Emotional experience in daily life: Valence, variability, and rate of change. Emotion, 1(4), 413–421. https://doi.org/10.1037/1528-3542.1.4.413

- Eisinga, R., Te Grotenhuis, M., & Pelzer, B. (2013). The reliability of a two-item scale: Pearson, Cronbach, or Spearman-Brown? International Journal of Public Health, 58(4), 637–642. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-012-0416-3

- Feinberg, M., Ford, B. Q., & Flynn, F. J. (2020). Rethinking reappraisal: The double-edged sword of regulating negative emotions in the workplace. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 161, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2020.03.005

- Feinberg, M., Willer, R., & Keltner, D. (2012). Flustered and faithful: Embarrassment as a signal of prosociality. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 102(1), 81–97. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0025403

- Finkenauer, C., & Rimé, B. (1998). Socially shared emotional experiences vs. emotional experiences kept secret: Differential characteristics and consequences. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 17(3), 295–318. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.1998.17.3.295

- Gable, S. L., Reis, H. T., Impett, E. A., & Asher, E. R. (2004). What do you do when things go right? The intrapersonal and interpersonal benefits of sharing positive events. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 87(2), 228–245. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.87.2.228

- Goodman, J. K., Cryder, C. E., & Cheema, A. (2013). Data collection in a flat world: The strengths and weaknesses of mechanical Turk samples. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 26(3), 213–224. https://doi.org/10.1002/bdm.1753

- Graham, S. M., Huang, J. Y., Clark, M. S., & Helgeson, V. S. (2008). The positives of negative emotions: Willingness to express negative emotions promotes relationships. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 34(3), 394–406. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167207311281

- Gross, J. J., & John, O. P. (2003). Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: Implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(2), 348–362. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.85.2.348

- Gross, J. J., & Thompson, R. A. (2007). Emotion regulation: Conceptual foundations. In J. J. Gross (Ed.), Handbook of emotion regulation (pp. 3–24). Guilford Press.

- Hauser, D. J., & Schwarz, N. (2016). Attentive Turkers: MTurk participants perform better on online attention checks than do subject pool participants. Behavior Research Methods, 48(1), 400–407. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-015-0578-z

- Heiy, J. E., & Cheavens, J. S. (2014). Back to basics: A naturalistic assessment of the experience and regulation of emotion. Emotion, 14(5), 878–891. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037231

- Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

- Larson, R., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1983). The experience sampling method. New Directions for Methodology of Social & Behavioral Science, 15, 41–56.

- Levontin, L., & Yom-Tov, E. (2017). Negative self-disclosure on the web: The role of guilt relief. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1068. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01068

- Mandel, D. R. (2003). Counterfactuals, emotions, and context. Cognition and Emotion, 17(1), 139–1159. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699930302275

- Napoli, J., Dickinson, S. J., Beverland, M. B., & Farrelly, F. (2014). Measuring consumer-based brand authenticity. Journal of Business Research, 67(6), 1090–1098. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2013.06.001

- Necka, E. A., Cacioppo, S., Norman, G. J., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2016). Measuring the prevalence of problematic respondent behaviors among MTurk, campus, and community participants. PLoS ONE, 11(6), e0157732. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0157732

- Nelissen, R. M. A. (2012). Guilt-induced self-punishment as a sign of remorse. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 3(2), 139–144. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550611411520

- Nelissen, R. M. A., & Zeelenberg, M. (2009). When guilt evokes self-punishment: Evidence for the existence of a dobby effect. Emotion, 9(1), 118–122. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014540

- Nils, F., & Rimé, B. (2012). Beyond the myth of venting: Social sharing modes determine the benefits of emotional disclosure. European Journal of Social Psychology, 42(6), 672–681. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.1880

- Pauw, L. S., Sauter, D. A., Van Kleef, G. A., & Fischer, A. H. (2018). Sense or sensibility? Social sharers’ evaluations of socio-affective vs. cognitive support in response to negative emotions. Cognition and Emotion, 32(6), 1247–1264. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2017.1400949

- R Core Team. (2018). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing.

- Rimé, B. (2007). Interpersonal emotion regulation. In J. J. Gross (Ed.), Handbook of emotion regulation (pp. 466–485). Guilford Press.

- Rimé, B. (2009). Emotion elicits the social sharing of emotion: Theory and empirical review. Emotion Review, 1(1), 60–85. https://doi.org/10.1177/1754073908097189

- Rimé, B., Finkenauer, C., Luminet, O., Zech, E., & Philippot, P. (1998). Social sharing of emotion: New evidence and new questions. European Review of Social Psychology, 9(1), 145–189. https://doi.org/10.1080/14792779843000072

- Rimé, B., Mesquita, B., Boca, S., & Philippot, P. (1991). Beyond the emotional event: Six studies on the social sharing of emotion. Cognition & Emotion, 5(5-6), 435–465. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699939108411052

- Roseman, I. J. (2013). Appraisal in the emotion system: Coherence in strategies for coping. Emotion Review, 5(2), 141–149. https://doi.org/10.1177/1754073912469591

- Roseman, I. J., Wiest, C., & Swartz, T. S. (1994). Phenomenology, behaviors, and goals differentiate discrete emotions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67(2), 206–221.

- Rosseel, Y. (2012). Lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. Journal of Statistical Software, 48(2), 1–36. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v048.i02

- Saintives, C., & Lunardo, R. (2016). Coping with guilt: The roles of rumination and positive reappraisal in the effects of postconsumption guilt. Psychology & Marketing, 33(5), 344–357. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.20879

- Shore, D., & Parkinson, B. (2018). Interpersonal effects of strategic and spontaneous guilt communication in trust games. Cognition and Emotion, 32(6), 1382–1390. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2017.1395728

- Shore, D. M., Rychlowska, M., Van der Schalk, J., Parkinson, B., & Manstead, A. S. R. (2019). Intergroup emotional exchange: Ingroup guilt and outgroup anger increase resource allocation in trust games. Emotion, 19(4), 605–616. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000463

- Summerville, A., & Buchanan, J. (2014). Functions of personal experience and of expression of regret. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 40(4), 463–475. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167213515026

- Swerdlow, B. A., Sandel, D. B., & Johnson, S. L. (2023). Shame on me for needing you: A multistudy examination of links between receiving interpersonal emotion regulation and experiencing shame. Emotion, 23(3), 737–752. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0001109.

- Tekoppele, J. L., De Hooge, I. E., & van Trijp, H. C. M. (2023). We've got a situation here! – How situation-perception dimensions and appraisal dimensions of emotion overlap. Personality and Individual Differences, 200, 111878. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2022.111878

- Tucker, L. R., & Lewis, C. (1973). A reliability coefficient for maximum likelihood factor analysis. Psychometrika, 38(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02291170

- Van Kleef, G. A., De Dreu, C. K., & Manstead, A. S. (2006). Supplication and appeasement in conflict and negotiation: The interpersonal effects of disappointment, worry, guilt, and regret. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 91(1), 124–142. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.91.1.124

- Van Osch, Y. M. J., Zeelenberg, M., & Breugelmans, S. M. (2016). On the context dependence of emotion displays: Perceptions of gold medalists’ expressions of pride. Cognition and Emotion, 30(7), 1332–1343. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2015.1063480

- Wetzer, I. M., Zeelenberg, M., & Pieters, R. (2007a). Consequences of socially sharing emotions: Testing the emotion-response congruency hypothesis. European Journal of Social Psychology, 37(6), 1310–1324. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.396

- Wetzer, I. M., Zeelenberg, M., & Pieters, R. (2007b). “Never eat in that restaurant, I did!”: Exploring why people engage in negative word-of-mouth communication. Psychology and Marketing, 24(8), 661–680. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.20178

- Zech, E., & Rimé, B. (2005). Is talking about an emotional experience helpful? Effects on emotional recovery and perceived benefits. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy: An International Journal of Theory & Practice, 12(4), 270–287.

- Zeelenberg, M., & Breugelmans, S. M. (2008). The role of interpersonal harm in distinguishing regret from guilt. Emotion, 8(5), 589–596. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0012894

- Zhang, X., Zeelenberg, M., & Breugelmans, S. M. (2021a). Anticipated guilt and going against one’s self-interest. Emotion, 21(7), 1417–1426. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0001032

- Zhang, X., Zeelenberg, M., Summerville, A., & Breugelmans, S. M. (2021b). The role of self-discrepancies in distinguishing regret from guilt. Self and Identity, 20(3), 388–405. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298868.2020.1721316