ABSTRACT

The goal of the study was to determine which aspects of interpersonal touch interactions lead to a positive or negative experience. Previous research has focused primarily on physical characteristics. We suggest that this may not be sufficient to fully capture the complexity of the experience. Specifically, we examined how fulfilment of psychological needs influences touch experiences and how this relates to physical touch characteristics and situational factors.

In two mixed-method studies, participants described their most positive and most negative interpersonal touch experience within a specific time frame. They reported fulfilment of nine needs, affect, intention, and reason for positivity/negativity, as well as the body part(s) touched, location, type of touch, interaction partner, and particular touch characteristics (e.g. humidity).

Positive and negative touch experiences shared similar touch types, locations, and body parts touched, but differed in intended purpose and reasons. Overall, the valence of a touch experience could be predicted from fulfilment of relatedness, the interaction partner and initiator, and physical touch characteristics. Positive affect increased with need fulfilment, and negative affect decreased.

The results highlight the importance of relatedness and reciprocity for the valence of touch, and emphasise the need to incorporate psychological needs in touch research.

Touch is important for social relationships and crucial to feel comfortable with each other (e.g.; Debrot et al., Citation2013). Consequently, the frequency of touching is higher in closer relationships (Beßler et al., Citation2020; Schirmer et al., Citation2021; Sorokowska et al., Citation2021; von Mohr et al., Citation2021), and close interaction partners touch more different body parts (Heslin & Alper, Citation1983; Schirmer, Cham, Lai, et al., Citation2023; Suvilehto et al., Citation2019).

How comforting or pleasant the experience of touch is depends on a number of physical and psychological factors. Among the physical properties that characterise touch, force combined with velocity has recently received a lot of attention in research. In particular, slow, gentle stroking, which activates the so-called C-tactile afferents (CTs), has been suggested to be of particular importance for positive emotional experience (McGlone et al., Citation2014). It is often rated as more pleasant than touch at higher velocities, which activates CT afferents to a lesser extent, while engaging A-beta afferents more (Ackerley, Backlund Wasling, et al., Citation2014; Löken et al., Citation2009).

Slow stroking touches are typical for skin-to-skin touch between individuals (Croy et al., Citation2016; Lo et al., Citation2021) and can therefore be understood as “social touch”. CT afferents are also activated by gentle indentation (Vallbo et al., Citation1999), and may therefore also be involved in hugs, another type of touch that features in close relationships (e.g.; Packheiser et al., Citation2022). In addition to CTs, there is a strong possibility that other skin receptors, such as Aβ mechanoreceptors, play a role in affective experiences and are capable of eliciting pleasurable sensations (e.g.; Schirmer, Croy, and Ackerley, Citation2023; Vallbo et al., Citation2016). An illustration of this is the pleasure derived from deep pressure touch targeted at Aβ fibres (Case et al., Citation2021). The pleasantness of both deep pressure touch and gentle stroking can be significantly diminished by peripheral nerve blockage of Aβ input to the brain (Case et al., Citation2023). Furthermore, stroking with CT-optimal velocity on the palm where Aβ fibres are abundant is as pleasant as on hairy skin abundant with CTs (e.g.; Ackerley, Carlsson, et al., Citation2014; Pawling et al., Citation2017).

In addition to force and velocity, affective responses to a touch can also be influenced by other physical characteristics such as its roughness/smoothness, hardness/softness, and coldness/warmness (e.g.; Guest et al., Citation2011; Hollins et al., Citation1993; Okamoto et al., Citation2013). For example, touches with materials that are rated as soft are typically perceived as more pleasant (Ekman et al., Citation1965; Essick et al., Citation2010; Etzi et al., Citation2014; Major, Citation1895; Marschallek et al., Citation2023; Verrillo et al., Citation1999).

However, the particular physical characteristics are only one aspect of a touch experience. For example, slow stroking by a close person in a relaxed situation may feel pleasant, but slow stroking performed by a stranger or if the receiver is not in the right mood may feel uncomfortable. Fisher et al. suggested (Citation1976) that touch is perceived as positive as long as it does not enforce a higher level of intimacy than the recipient is comfortable with (Argyle & Dean, Citation1965; Sommer, Citation1969) or sends a negative message, for example, by being perceived as patronising (Henley, Citation1970).

In fact, several authors have shown that touch can effectively convey a message. The sense of touch alone is capable of effectively communicating a wide range of emotions, including anger, fear, disgust, love, gratitude, sympathy, happiness, and sadness (Hertenstein et al., Citation2009; Hertenstein, Keltner, et al., Citation2006; Hertenstein, Verkamp, et al., Citation2006). When it comes to expressing feelings of love and sympathy, touch is considered the preferred means of communication, surpassing body language and facial expressions (App et al., Citation2011). The ability to quantify the physical aspects of intuitive touches that successfully convey emotions (Hauser et al., Citation2019; McIntyre et al., Citation2022) bolsters the notion of universal interpersonal touch strategies.

The communicative or signifying dimension of touch was also emphasised by Jones (Citation1999), who noted that “the same type of touch can have different meanings” and “different touches can have the same meaning” (p. 194). In their seminal paper, Jones and Yarbrough (Citation1985) asked 39 participants to record the touch events they experienced during three days. The gathered 1500 records were then categorised and interpreted to determine different meanings. Examples for such meanings would be “support – serves to nurture, reassure or promise protection” or “announcing a response – calls attention to and emphasises a feeling state of initiator”. They identified “key features” of each meaning, such as the way a touch is performed or contextual elements that need to be present. For example, the key features of attention-getting touches were that they are initiated by the person requesting attention, that the initiator clarified the purpose, and that the touches were brief and directed to 1–2 different body parts. This example illustrates how the combination of intention, physical touch characteristics and situational characteristics produces the different meanings of touch.

Presumably, another crucial factor in the emotional experience of touch is its congruence with the wishes of the recipient (Sailer & Leknes, Citation2022). This idea is also implicit in models of social homeostasis, which assume that there is an individual set point for the quantity and/or quality of social contact (Lee et al., Citation2021; Matthews & Tye, Citation2019). It is also in line with models of person-environment fit to assume “that for feeling good, people’s motives (goals) must correspond to the gratifications provided by their environment” (Brandstätter, Citation1994, p. 1). The importance of individual motives (i.e. needs) has also been recognised in the field of Human–Computer Interaction (HCI), where it changed the approach to designing interaction from the mere efficiency-oriented to the experiential. An according goal for interaction design is thus that the characteristics of the interaction should match or even express the psychological needs of the user in this particular interaction (Hassenzahl, Citation2010; Lenz et al., Citation2017).

A psychological need can be defined as “an energising state that, if satisfied, conduces toward health and well-being but, if not satisfied, contributes to pathology and ill-being” (Ryan & Deci, Citation2000, p. 74). Self-determination theory (Ryan & Deci, Citation2000) suggests three central needs: autonomy (i.e. to be able to determine own behaviour without external influence), competence (i.e. to experience oneself as capable and competent and being able to reliably predict outcomes), and relatedness (i.e. to care for and feel related to others). Additional needs, such as stimulation, physical thriving, or popularity complement the three central needs (Sheldon et al., Citation2001). Studies unanimously show that need fulfilment is crucial to positive experience. For example, when participants are asked to remember positive life experience and to indicate to what extent needs had been met, need fulfilment correlates with the positivity of the experience (Sheldon et al., Citation2001). This pattern emerges at daily level (Howell et al., Citation2011), and is replicated for positive experiences with interactive products (Hassenzahl et al., Citation2010, Citation2015).

In this paper, we apply the concept of need fulfilment to better understand positive and negative touch experiences. We gathered positive and negative touch experiences and assessed need fulfilment, valence, body parts touched, touch types used, interaction partner, and context of the touch. Previous studies showed that accepted and wanted touch varies with the type of touch, the body parts touched, the interaction partner, and who initiated the touch (e.g.; Beßler et al., Citation2020; Heslin & Alper, Citation1983; Jones & Yarbrough, Citation1985; Nguyen et al., Citation1975; Schirmer, Cham, Lai, et al., Citation2023; Suvilehto et al., Citation2015). These factors might therefore also influence the valence of the touch experience.

We hypothesised that a larger degree of need fulfilment is related to higher positive affect. This was assumed because in general, need fulfilment correlates with positive affect and happiness (Hassenzahl et al., Citation2010, Citation2015; Partala & Kallinen, Citation2012; Reis et al., Citation2000; Sheldon et al., Citation2001). Extrapolating from these findings on positive affect, we also hypothesised that a larger degree of need fulfilment is also related to lower negative affect. Moreover, we hypothesised that need fulfilment can predict whether a touch was experienced as positive or negative, and that need fulfilment would be a better predictor for the valence of a touch experience than physical touch characteristics.

These assumptions were tested in two different studies using retrospective self-reports. In both studies, participants were asked to describe the most positive and most negative interpersonal touch situation in a given time interval and to report their individual need fulfilment and the positive and negative affect experienced in those situations. In study 1, the touch events were restricted to non-sexual touch received from the romantic partner, whereas the participants in study 2 were free to report any type of touch with any interaction partner, including self-initiated touch.

Study 1

Method

Participants

The study was part of a larger project in which participants recorded the frequency of non-sexual touch received from their partner daily for one week. Power analysis was calculated for the main outcome of the larger study (touch frequency, results to be reported elsewhere), 120 participants (70 female, 46 male, 1 non-binary, 2 chose not to answer) were recruited. The median age of the sample was 23 years (mean age 24; age range 18–41). 103 participants were students, 11 working, 2 in training, 1 unemployed, 2 did not reply. 112 had a high school diploma, 2 with middle school diploma, 4 with a different school diploma, 2 did not reply. 107 were in a heterosexual relationship, 13 in a homosexual relationship. 66 lived in separate households, 52 lived together, 2 did not reply. The median relationship duration was 2 years and 1 month (N = 115, M = 35.6 months, SD = 34.1 months).

Power analysis was calculated post-hoc for the analysis methods used for the present data, namely a 2*9 repeated-measures ANOVA and pairwise correlations. For the lowest observed Eta-squared value in the ANOVA results (Eta-squared = 0.325), an effect size of f = 0.69 and a power of 1 resulted. For the smallest observed correlation of r = .26 and an alpha-level of .05, the power was 0.89.

Participants were recruited through public notices in University buildings, public libraries, supermarkets, through posts in forums, a mailing list for psychology students, and social networks. Inclusion criteria were at least 18 years of age, proficiency in the German language, currently being in a romantic relationship and having at least one in-person contact with the partner during the assessment week. As compensation, participants could choose between course credits (psychology students) and a payment of 20 €.

Measures

Touch experiences questions: Participants were asked to describe the most positive and most negative experience of touch received from their partner during the preceding week on paper. No definitions or instructions regarding the terms “positive” and “negative” were given. Participants were asked to describe the situation in which the touch took place, the body part that was touched and the type of touch (open answers). They also answered the open-ended questions “How did you feel during the touch?” and “How do you think it made your partner feel?”. The questionnaire provided an example touch to illustrate potential answers to these questions.

German version of Sheldon’s need questionnaire (Hassenzahl et al., Citation2010): Sheldon’s Needs questionnaire assesses the degree of fulfilment of 10 different needs: autonomy (feeling that one’s activities are self-chosen and self-endorsed), competence (to experience oneself as effective and attaining or exceeding a standard in one’s performance), relatedness (a sense of belonging and closeness with others), self-actualisation-meaning (a sense of long-term growth and meaning), physical thriving (feeling healthy and that biological requirements are satisfied), pleasure-stimulation (experiencing enjoyment and pleasurable stimulation), money-luxury (attaining material dominance), security (a sense of order and predictability), self-esteem (a sense of personal worthiness and importance), and popularity-influence (making friends and influencing others). Answers were coded from 1 (not at all) to 5 (extremely), so that high values indicate high need fulfilment.

We omitted items regarding the need for money-luxury which we considered irrelevant for touch. For the remaining 9 scales, only the two items we considered most relevant for touch were included (see Table S1 in Supplementary Materials for items used). This was done because participants also reported other data and we aimed to keep the entire form within a reasonable length. To determine the reliability for each shortened scale, Spearman Brown coefficients were calculated and are reported in Table S1 (Eisinga et al., Citation2013).

For Sheldon’s Needs questionnaire, the values for different needs were obtained by calculating the mean of the items constituting the respective need scale.

Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (German item translation by Krohne et al., Citation1996; Mackinnon et al., Citation1999; PANAS; Watson et al., Citation1988). The PANAS was preceded by the question “How did you feel during the touch?”. The PANAS contains 20 items. Positive affect represents the extent to which a person feels alert and enthusiastic, with high positive affect characterising a state of high energy and experiencing pleasure, whereas low positive affect rather represents sadness and lethargy (Watson et al., Citation1988). Negative affect characterises a state of distress and unpleasurable engagement, whereas low negative affect represents calmness and serenity. Answers were coded from 1 (not at all) to 5 (extremely), so that high values indicate high positive or high negative affect, respectively. The PANAS was employed to allow for a replication of the previously found relationship between need fulfilment and positivity of the affective experience.

Positive and negative affect were determined by calculating the mean of the items in the positive affect and negative affect subscales of the PANAS separately for positive and negative touch experiences.

Procedure

In the larger project, participants were asked to count all touch received from the partner with a mechanical counter. They were told that this included “all touches that you feel as such, such as stroking, hugging, random grazing, kissing, holding hands, laying hands on and many more”. They were also instructed that a touch would be counted as another touch if either the type of touch changed or there was a pause between touches, which was also illustrated with an example. They were asked to “not report touch that occurred while having sex”.

At the end of one week of daily touch assessment, participants filled in the touch experiences questions on paper. Participants then filled out the German version of Sheldon’s Needs questionnaire (Hassenzahl et al., Citation2010) for the positive touch experience, followed by the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS: German item translation by Krohne et al., Citation1996; Mackinnon et al., Citation1999) as a measure of positive and negative affect. Afterwards, they filled in Sheldon’s Needs questionnaire for the negative touch experience, followed by another PANAS. All questionnaires were on paper.

The study protocol was preregistered at https://osf.io/s9c3j (Hypothesis 3). The study was approved by the Ethical Commission of the Faculty of Social and Behavioural Science, Friedrich-Schiller University Jena (FSV 21/074).

Data analysis

Analysis of open questions: Open questions were analysed by thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006, Citation2019). The first author (US) read and re-read the answers in order to identify potential overarching themes (categories). In this way, the individual answers on touched body parts were grouped into larger categories in a bottom-up approach, and the same was done for type of touch, touch situation, and the experienced emotion during the touch. The German answers were coded into English categories. These overarching themes (categories) were then discussed with the author YF. The coding was carried out with the software NVivo (Version 12, 2018). Finally, quotes were identified that were congruent with the overarching themes.

For most questions, the answer of one participant was sorted into one overarching category. However, many participants named multiple and qualitatively different emotions in the question about their emotion during the touch experience, and the situation in which it occurred. The answer of one participant could therefore be assigned to several different categories. For example, the answer “valued, accepted, loved” was assigned to the three categories “valued”, “accepted”, “loved”. When the answers about the situation were ambiguous (which occurred primarily for the positive experience), the response about the participants’ and the partner’s feelings was also taken into consideration.

The answers about the situation of the touch experience were further divided into three different themes: (1) spatial location of the touch experience, which could be either private (at home or in own car) or public (with others, outside on street). (2) The reason for why the touch experience was negative or positive (e.g. “wanted to do or was busy with something else”), and (3) the assumed intention behind the touch. The answers to the question how they thought the partner felt were only used to verify the assumed intention behind the touch and the reasons for why the touch experience was negative or positive.

Statistical analysis: Statistical analyses were run on SPSS V. 27. Graphs were made with R Version 4.3.0 using, ggplot version 3.4.2 and GraphPad Prism version 9.3.1.

The data were checked for outliers based on the Q-Q plot of residuals and standardised residuals. Firstly, as a manipulation check (not pre-registered), we tested if positive touch experiences elicit more positive affect than negative affect, and if negative touch experiences elicit more negative affect than positive affect. Two Bonferroni-corrected paired t-tests were calculated comparing positive affect for the negative and positive touch experience, and negative affect for the negative and positive touch experience. Effect sizes are reported as Cohen’s d.

Secondly, to test whether positive touch experiences fulfil more needs than negative touch experiences, need fulfilment for each need was compared for positive and negative experiences in a 2*9 repeated-measures ANOVA with the factors touch experience (positive, negative) and needs (autonomy, competence, relatedness, self-actualisation, physical thriving, pleasure-stimulation, security, self-esteem, popularity). This deviated from the pre-registered analysis of a multiple regression with positive and negative affect as the outcome. The reason for this change in the analysis plan was that we decided to focus on the relationship between the touch experience and need fulfilment rather than on the relationship between need fulfilment and affect. This also corresponds better to the way in which the open questions were put to the participants, and therefore to the structure of the qualitative data. Effect sizes for the ANOVA are reported as partial Eta-squared. Greenhouse-Geisser corrected degrees of freedom are reported where sphericity was violated. A significant interaction was followed up by Bonferroni-corrected paired t-tests.

Pairwise Pearson correlations were calculated to determine if fulfilment of the 9 needs is related to higher positive affect and lower negative affect. The correlations were Bonferroni-corrected. To compare the strength of correlations between need-fulfilment with positive versus negative affect, a bootstrap approach was employed to compute nonparametric confidence intervals for the differences between absolute values of correlation coefficients.

Results

Characterisation of positive and negative touch experiences

Reported emotions

Each participant had the opportunity to name several emotions. Altogether, 132 emotions were named for the positive touch experience, and 90 emotions for the negative touch experience. The three most frequent positive emotions were “secure” (31 counts), “loved” (18 counts), and “happy” (14 counts). The four most frequent negative emotions were “irritated” (13 counts), “uncomfortable” (11 counts), “painful” (8 counts), and “unpleasant” (8 counts). The negative touch experiences were sometimes associated with mixed feelings, as the emotions “happy”, “amused” and “cared for” were also mentioned.

| b. | Touch types | ||||

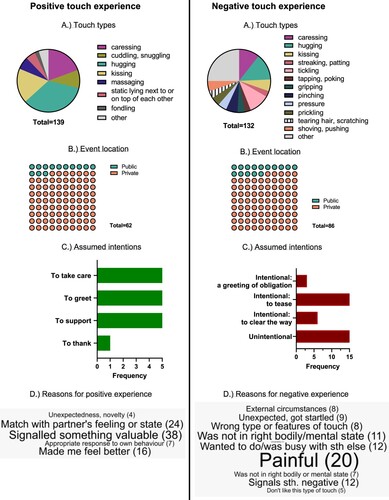

All in all, participants reported 25 different types of touch (see and Table S2 in Supplementary Materials). Thirteen of them were unique to negative experiences (e.g. slapping and pinching), and two were unique to positive experiences (fondling and static lying). The same touch could be involved in both positive and negative experiences (e.g. hugging). Hugging was both the most frequent positive experience (48 counts out of 139) and the most frequent negative experience (18 counts out of 122).

| c. | Touched body areas | ||||

Figure 1. (A) Touch types (frequencies). “Positive”, types that were named less than three times and “negative” types named less than four times are summarized in the category “other”, (B) event locations (in %), (C) assumed intentions behind the touch (frequencies), and (D) reasons for why the touch experience was positive (N = 47) or negative (N = 24) with frequencies in parentheses. Note that participants only mentioned assumed intentions for a small number of touch experiences (for exact numbers and examples, see Tables S2, S3, S4 in Supplement).

Most frequently involved in a positive experience (33 counts out of 137) was touch to the upper body (i.e. in hugging and cuddling) (see Figure S1 in Supplementary Materials). The second most frequent body part mentioned in positive touch was the head (22 counts out of 137), for example running the fingers through the hair during cuddling. The back was mentioned 11 times. Positive touch experiences on the back occurred, for example, during massage or cuddling.

Interestingly, the upper body and shoulder were also most frequently reported in a negative experience (each 13 counts out of 138), for example in situations when the participant was not in the mood (e.g. “I felt very absent and wasn't quite there on Saturday night in the kitchen. That's why touching didn't feel so good”). This was followed by the arm and stomach (each 11 counts out of 138). The arm, for example, was grabbed roughly during an argument or tickled on the underside. The foot was named 7 times as negative touch location in the context of teasing. The genitals and the nose were only named for negative touch experiences with the partner, most often in relation to unintentional touch.

| d. | Touch situations | ||||

Altogether, the majority of the reported touch experiences occurred in private settings (see and Supplementary Tables S3 and S4). Thus, positive and negative touch experiences with the partner do not seem to differ regarding the geographical location where they took place.

| e. | Reasons and intentions | ||||

Most reasons given for why a touch experience was positive and negative differed. The only reason common to both experiences was unexpectedness. Thus, an unexpected touch can be experienced as both positive and negative. Among the reasons specific for positive experiences was the match with the partner’s feelings or state, pointing to the interactive nature of touch or that the touch signalled something of value to the recipient. Among the reasons for negative experiences were instances when the touch recipient was busy doing something else, or was not in the right state of mind for receiving the particular touch.

Similarly, the assumed intentions differed between positive and negative experiences. Assumed intentions for positive experiences were thanking or support, whereas assumed intentions for negative experiences could be separated into intentional (e.g. teasing) and unintentional (accidental).

All in all, the reasons and the assumed intention of the touch provider distinguish negative and positive touch experiences, while the touch types and geographical location remained inconsequential.

| (2) | Affect in positive and negative touch experiences | ||||

PANAS ratings showed significantly higher negative affect for negative than positive touch experiences (t[116] = −16.07, d = −1.49) and more positive affect for positive than negative touch experiences (t[116] = 14.05, d = 1.30; pBonf’s < .025). The mean values () show that positive affect was stronger in positive touch experiences (diff = 2.01), and negative affect almost non-existent, whereas in negative touch experiences, the difference was less pronounced (diff = 0.22), with a substantial amount of positive affect being present as well. This underlines the more diverse nature of negative touch experiences. Accidental negative touches, for example, may not create as much negative affect as touches seen as intentional (e.g. teasing).

| (3) | Need fulfilment in positive and negative touch experiences | ||||

Table 1. Means and standard deviations for positive and negative affect and overall need fulfilment in positive and negative touch experiences (study 1).

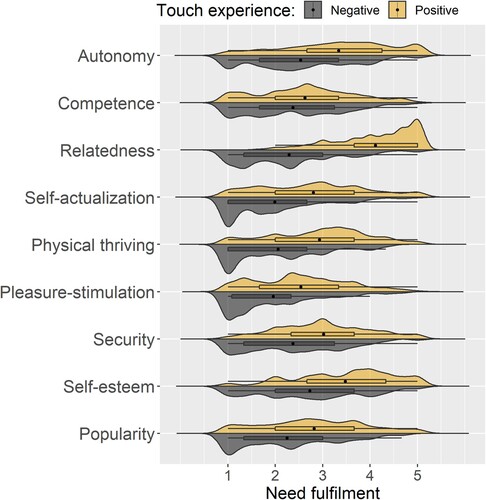

Fulfilment of all needs was higher for positive than for negative experiences (; main effect for touch experience with F(1,117) = 550.72; p < .001; Eta-squared = 0.83). In addition, the individual needs were fulfilled to a different extent (main effect of needs with F(8,731) = 106.93; p < .001; Eta-Squared = 0.48), see . These main effects were further qualified by a significant interaction between touch experience and needs, which indicated that the difference between positive and negative experiences was more pronounced for particular needs than for others (F(8,688) = 56.37; p < .001; Eta-squared = 0.33).

Figure 2. Need fulfilment in positive [N = 120] and negative [N = 120] touch experiences with the partner. Dot shows the mean, boxes upper and lower quartile, and whiskers minimum and maximum values. Kernel density estimation illustrates the distribution shape of the data where wider sections represent higher probabilities of a given value.

![Figure 2. Need fulfilment in positive [N = 120] and negative [N = 120] touch experiences with the partner. Dot shows the mean, boxes upper and lower quartile, and whiskers minimum and maximum values. Kernel density estimation illustrates the distribution shape of the data where wider sections represent higher probabilities of a given value.](/cms/asset/50036036-919a-467d-8251-44a4cab75103/pcem_a_2311800_f0002_oc.jpg)

suggests that in particular self-actualisation and physical thriving are violated during negative touch experiences; and that relatedness and physical thriving are particularly important for positive touch experiences. Autonomy and popularity appeared to be the least different needs for positive and negative touch experiences. Nevertheless, all paired differences were highly significant with all pBonf’s < .006. The highest effect sizes (Cohen’s d) were observed for physical thriving, self-esteem and relatedness, suggesting that the differences were somewhat larger for these needs than the others.

| (4) | Relationship between need fulfilment and the affect resulting from a touch experience | ||||

Within positive experiences, positivity of affect was significantly correlated (pBonf = .006) with self-actualisation (r = 0.27), self-esteem (r = 0.30), pleasure-stimulation (r = 0.53), physical thriving (r = 0.27) and popularity (r = 0.36). Thus, as these needs were increasingly fulfilled during positive experiences, positive affect also exhibited higher levels. At the same time, higher physical thriving, pleasure-stimulation and self-esteem were also related to lower negative affect during positive experiences; see Table S5 (Supplementary Materials) for details.

For negative experiences, negativity of affect was significantly correlated (pBonf = .006) with self-esteem (r = −0.31), security (r = −0.39), and physical thriving (r = −0.27). This means that lower self-esteem, lower security and lower physical thriving are related to higher negative affect during negative experiences. At the same time, an increase in the fulfilment of all needs correlated with increased positive affect during negative experiences (see Table S5), with the highest correlations for competence (r = 0.53) and self-esteem (r = 0.50). No other pairs of variables were correlated after Bonferroni correction for multiple testing.

To summarise, fulfilment of the needs for self-esteem and physical thriving in touch with the partner is relevant for both positive and negative affect. Need-fulfilment was correlated with positive affect slightly stronger than with negative affect, according to the last three columns of Table S5 (Supplementary Materials).

Summary

Study 1 showed that positive touch experiences were characterised by higher positive affect, lower negative affect and a higher degree of fulfilment of every single need. Fulfilment of several needs correlated with affect in positive and negative touch experiences. This finding is consistent with prior research conducted by other authors in different contexts, such as daily life events (Sheldon et al., Citation2001) or interactions with interactive products like computers and mobile phones (Hassenzahl et al., Citation2010).

The type of touch and the location (i.e. geographical place) where the touch took place were not clearly different between positive and negative touch experiences. In contrast, the presumed intention of the toucher and the reasons for the valence of the touch distinguished better between negative and positive experiences.

Limitations of the study were that the study only contained information about touch that was initiated by the partner, and no self-initiated touch – which might be expected to influence the valence of a touch experience. Self-initiation links to autonomy and implies higher controllability, both of which contribute to well-being (Linley et al., Citation2009; e.g.; Ly et al., Citation2019). In addition, due to the open answer format, not all participants mentioned the presumed intention behind the touch or named a reason for why the experience was positive or negative. Moreover, the open answers about the touch “situation” were often very complex and included a range of factors that could be difficult to code, e.g. “Lying in bed and cuddling up to each other. Snow outside. Bodies lengthwise against each other. Wonderfully warm.”

Therefore, study 1 was followed up with a larger sample, more explicit questions with closed answer format and including touch with different interaction partners, and all types of touch, i.e. including sexual touch. Furthermore, we aimed to investigate the role of different physical characteristics in positive and negative touch experiences. Physical features were named in some of the qualitative answers among the reasons for why the touch was positive (see example above) or negative (e.g. “painful”). Physical features, in particular roughness, influence the pleasantness of touch with surfaces and fabrics (e.g.; Etzi et al., Citation2014; Klöcker et al., Citation2014; Wijaya et al., Citation2020), but also of touch with humans (e.g.; Gentsch et al., Citation2015). Stroking velocity alters the pleasantness of being stroked (e.g.; Löken et al., Citation2009). Thus, it is known that physical features of a touch are important for its experience, but not how important physical features are relative to other factors such as need fulfilment.

As a further change from study 1, positive and negative experiences were sampled from different participants in study 2, which allowed us to employ a logistic regression model for predicting the valence of the touch experience. In addition, due to the low reliability of some of the scales with the shortened questionnaire, the full version was used in study 2.

As in study 1, we tested the hypothesis that we also assumed that positive affect increases with and that negative affect decreases with need fulfilment. We also hypothesised that the valence of a touch experience can be predicted from need fulfilment, and that need fulfilment would be a better predictor than physical touch characteristics.

Study 2

Methods

Participants

Power analysis was calculated with GPower for a multiple linear regression with 15 predictors, a power of 0.8, a medium effect size of f2 = 0.15 (Cohen, Citation1977), and an alpha-error level of 0.05 (Faul et al., Citation2009). A sample size of 139 was recommended. However, we later changed the analysis plan to a logistic regression (which was also included in the preregistration as exploratory analysis). Logistic regression can be employed as discrimination model which is robust to violation of common assumptions in discrimination analysis such as multivariate normality. It can also be used in retrospective or prospective studies by considering group indicator as an outcome to assess the relationship between covariates (predictor variables) and the occurrence of an event (see for example Hilbe, Citation2009; Kuo et al., Citation2018; Suarez et al., Citation2017). Because the pre-registration did not contain an a priori power analysis for the logistic regression, a simulation-based power analysis was performed post-hoc with R Version 4.3.0 for a logistic regression model with 17 predictors with weak to moderate collinearity, a power of 0.85, a moderate effect size of Cohen’s h = 0.3, and an alpha-error level of 0.05. The recommended sample size was 280.

300 participants were recruited from the UK in order to make sure they had good knowledge of the English language. 160 women and 140 men with a median age of 35.5 (mean age 37; age range 19–77) participated. They were recruited through the online recruitment service Prolific (Prolific.com). From Prolific, participants were directed to the online survey tool of the University of Oslo called Nettskjema (https://www.uio.no/tjenester/it/adm-app/nettskjema/). Payment was set at £8/hr and it took a median time of 8 min to fill in the questionnaire, resulting in a payment of 2£ per participant.

Inclusion criteria were healthy volunteers from 18 to 80 years located in the UK. Exclusion criteria were current untreated depressive or psychotic states (self-reported).

The study protocol was approved by the Norwegian Centre for Research Data (reference number 316709), and was preregistered at https://osf.io/dyunj.

Measures

Half of the participants were instructed to recall the “single most positive touch event”, and the other half the “single most negative touch event” with a human interaction partner that had occurred in the past month. Regarding the definition of “positive” and “negative”, we adapted the original instruction from Sheldon and colleagues (Sheldon et al., Citation2001) and used the sentence “we are being vague about the definition of “positive event” on purpose, because we want you to use your own definition. Think of “positive” in whatever way makes sense to you”.

Touch characterisation questions: Participants were then asked to assess the chosen experience on the basis of various aspects. To facilitate the coding of the answers, the questions with open-answer format from study 1 were more specific. First, participants were asked to select the type of touch from a set of different options illustrated with pictures taken from the “Longing for Interpersonal Touch Picture Questionnaire” (LITPQ; Beßler et al., Citation2020): handshake, hand on shoulder, kiss, caress, hug (all these were closed-format), or “other” (open answer format). The next question inquired about the interaction partner: partner, family member, friend, acquaintance, colleague, stranger (all these closed-format), or “other” (open answer format). This was followed by a question about who took the initiative for the touch (self, other, or both), and two open questions about the (presumed) intention of the touch and why the touch experience was positive/negative. Participants were also asked for a short description of the geographical location and the situation in which the touch occurred (open answer format). To measure the closeness to the interaction partner, the Inclusion of the Other in the Self scale (IOS; Aron et al., Citation1992) was used.

Physical attributes of the touch were assessed using visual analogue scales (VAS). Here, participants characterised the touch according to the following attributes: roughness (anchors: rough-soft), intensity (anchors: weak-strong), duration (anchors: short-lasting-long-lasting), humidity (anchors: damp-dry), and velocity (anchors: slow-fast). For humidity and velocity participants also had the option to choose “not applicable”. In addition, psychological characteristics of the touch were assessed with VAS-scales for pleasantness (anchors: unpleasant-pleasant), comfort (anchors: uncomfortable-comfortable), appropriateness (anchors: appropriate-inappropriate) and expectedness (anchors: unexpected-expected).

Sheldon’s need questionnaire (Sheldon et al., Citation2001): Participants were then asked to specify to what extent the touch experience met or did not meet nine different needs. Similar to study 1, needs were measured with Sheldon's questionnaire (Sheldon et al., Citation2001) under exclusion of the need for luxury scale. In contrast to study 1, all items of the nine scales included were used. For the reliability of the different needs scales with the present sample, see Table S6 in the Supplementary Materials.

Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS; Watson et al., Citation1988): To investigate whether those experiences that best fulfil psychological needs elicit the most positive emotions, participants filled in the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS; Watson et al., Citation1988). In contrast to study 1 where the short version of the PANAS was used, the long version was used in study 2.

Data analysis

The open questions about the setting of the touch, the assumed intention of the toucher, and the reason for why the touch experience was negative or positive were analysed according to principles of systematic text condensation (Malterud, Citation2012). Overarching themes were generated using NVivo software (Version 12, 2018) for data management. Independently from each other, two persons (one of them US, first author) identified codes in the material. These codes were then integrated to themes in an iterative process until both persons agreed on a final categorisation.

Statistical analyses were run on SPSS V. 27 and R Version 4.3.0. Graphs were made with R Version 4.3.0 using, ggplot version 3.4.2 and GraphPad Prism version 9.3.1.

All quantitative data were checked for outliers. Similar to study 1, we first performed a manipulation check by testing if positive touch experiences elicit more positive than negative affect, and if negative touch experiences elicit more negative than positive affect. Because the variances were unequal and three of the variables were non-normally distributed, two Bonferroni-corrected Mann–Whitney U tests were calculated comparing positive affect for the negative and positive touch experience, and negative affect for the negative and positive touch experience.

To test whether positive experiences fulfil more needs than negative touch experiences, need fulfilment for each need was compared for positive and negative experiences in a one-way ANOVA. Effect sizes are reported as partial Eta-squared.

To test whether positive and negative touch experiences are associated with need fulfilment, a logistic regression model was fitted to the data with the outcome variable “experience type” (positive or negative). This method was preregistered as our alternative choice, whereas a linear regression with positive and negative affect as outcomes was preregistered as first choice. The reason for choosing the alternative was our wish to concentrate on the relationship between need fulfilment and touch experience instead of on the relationship between need fulfilment and affect. Moreover, this choice allowed us to maintain consistency with the analysis of study 1 and the qualitative data, where positive and negative touch experiences were also compared. Logistic regression can be used to predict group membership (Pampel, Citation2000), as for example in case–control studies (Suarez et al., Citation2017). We also slightly adjusted the pre-registered hypotheses to the ones now stated in the Introduction to match this logistic regression.

Each continuous variable was standardised by subtracting its value from the mean and dividing by the standard deviation. The main effects of the 9 needs together with the physical touch characteristics intensity, roughness, duration, humidity and velocity were predictors in the model. Gender, initiative (0 (reference group) = me and both, and 1 = other) and interaction partner (0 (reference group) = partner, friend and family member, and 1 = acquaintance, colleague and stranger) were entered as factors. Effect sizes are reported by odds ratio values. The odds of an event is the event’s occurrence probability divided by the probability that it will not occur, and odds ratio quantifies the strength of the association between two events, by comparing the odds of one event occurring in two different conditions.

Missing values of humidity (135) and velocity (50) were checked for their randomness with the Little’s MCAR test (Li, Citation2013). Since the test did not reject the hypothesis that the missing data are missing completely at random (Chi-Square = 73.18, df = 68, p = .312), missing values were handled with a multiple imputation approach. The multiple imputation was implemented using the R package mice with 100 iterations. The logistic regression model was fitted to each iteration and finally the pooled results were obtained using the pooling rule proposed by Rubin (Citation1987). Multicollinearity was investigated by spectral decomposition of the model data matrix. The model data was full rank with no severe multicollinearity problem.

To determine if the previously found positive associations between need fulfilment and positive affect could be replicated, and to find out if need fulfilment also reduces negative affect, pairwise Pearson correlations were calculated between need fulfilment and positive and negative affect. Correlations were Bonferroni-corrected. The strength of Pearson correlations between need-fulfilment and positive affect and the strength of Pearson correlations between need-fulfilment and negative affect were compared by a non-parametric approach. For this purpose, nonparametric confidence intervals for the differences between absolute values of correlation coefficients were computed using a bootstrap method.

Results

Characterisation of positive and negative touch experiences

Touch types

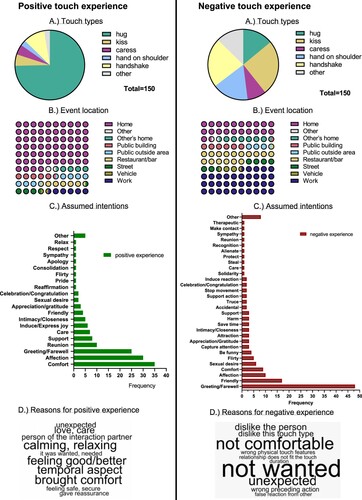

Two-third of touches in positive experiences were hugs, whereas the touch types in negative experiences were more equally distributed (see ). The most frequently named touch type in negative experiences was the kiss. All touch types appeared in both negative and positive touch experiences. Examples for mentions under the category “other” were “cuddle/spooning”, “handshake that fell into a hug”, and “headlock”.

| b. | Event location | ||||

Figure 3. (A) Touch types (frequencies), (B) event location (%), (C) assumed intentions behind the touch (frequencies), and (D) the 10 most frequent reasons given for why the experience was positive or negative (for exact number of reasons and further categories, see Table S8 in Supplements).

The majority of positive touch experiences took place at the respondent’s home. The three most frequently mentioned places where negative touch experiences took place were at home, work/school, and restaurants/pubs/bars/clubs ().

| c. | Assumed intentions | ||||

The assumed intentions () behind positive and negative touch experiences showed some overlap, but also considerable differences. For example, “affection” (30 counts out of 150) and “comfort” (35 out of 150) were among the most frequent assumed intentions for both positive touch experiences, and also for negative (“affection”: 10 out of 150; “comfort”: 9 out of 150) touch experiences. Similarly, “sexual desire” could be the assumed intention behind positive as well as negative touch experiences. “Greeting” was the most frequent category for negative experiences (48 out of 150), followed by “friendly” (17 out of 150). In addition, participants paraphrased the underlying need for relatedness, by for example, describing the importance and fulfilling character of physical touch (“create closeness”, “is needed”, “expresses love and care”).

As to the differences between positive and negative touch experiences, the intentions behind negative touch experiences were more varied than those behind positive touch experiences (31 different categories for negative touch experiences, 21 for positive touch experiences). Intentions of harming or alienating were only named for negative touch experiences. Thus, “bad intentions” were only named for negative touch experiences, whereas good intentions could lead to both negative and positive touch experiences. In general, participants perceived most intentions behind the touch as positive, irrespective of whether the touch experience was marked as positive or negative.

| d. | Reasons for positive or negative touch experience | ||||

Various reasons were given for why a touch was experienced as positive or negative. Positive touch was driven by positive affective experience (“feeling good”, “feeling better”, “happiness”) with a focus on comfort and relaxation. The interaction partner was also mentioned several times as a reason why touch was classified as a positive or negative experience. In contrast, touch experiences were negative when they were unexpected and unwanted, or when the “relationship” did not match the touch (e.g. “I did not consider the person close enough to me to touch me in that way”) (see Table S8 in Supplementary Materials). Interestingly, physical touch characteristics (e.g. limpness or wetness of handshake) played a crucial role only for the negative (17 counts out of 150) but not for positive touch experiences (2 counts out of 150).

Note that there had been a number of occasions where the question appears to have been misunderstood, e.g. where individuals answered just “yes” or “no”, possibly overlooking the “why” in “why was the touch experience positive/negative?” (coded as “not answering the question” in Table S8).

| (2) | Affect in positive and negative touch experiences | ||||

The division of touch experiences into positive and negative was supported by the PANAS ratings (), which showed significantly higher negative affect for negative than positive touch experiences and more positive affect for positive than negative touch experiences (U = 4009 for positive affect comparison, and U = 19183 for negative affect comparison; pBonf’s < .025). As in study 1, the mean values indicate that positive affect is also present during negative touch experiences, but that very little negative affect is present during positive touch experiences.

| (3) | Need fulfilment in positive and negative touch experiences | ||||

Table 2. Means and standard deviations for positive and negative affect in positive and negative touch experiences (study 2).

Fulfilment of all needs was significantly higher for participants who described a positive touch experience than for those who described a negative touch experience (see , and Table S7 for inferential statistics). It appears as if relatedness and self-esteem are the most fulfilled needs during positive touch experiences, and pleasure-stimulation, physical thriving and self-actualisation the least fulfilled needs during negative touch experiences. The largest differences between positive and negative touch experiences were observed for relatedness, physical thriving and autonomy. In Study 1, the largest differences were also found for physical thriving and relatedness, but not for autonomy.

| (4) | Predicting the valence of the touch experience from need fulfilment | ||||

Figure 4. Need fulfilment in positive and negative touch experiences. Dot shows the mean, boxes upper and lower quartile, and whiskers minimum and maximum values. Kernel density estimation illustrates the distribution shape of the data where wider sections represent higher probabilities of a given value.

The total accuracy of the logistic regression model was 91.28% with a sensitivity of 93% and a specificity of 89.68% (for estimations of regression coefficients see ).

Table 3. Logistic regression coefficients for positive and negative touch experiences in Study 2 (significant effects are in bold font). For the categorical variables the target category vs reference category are [1]: Female vs male [2]: Me/both vs other [3]: Friend/family-member/partner vs acquaintance, colleague, stranger.

Among the nine needs, only the fulfilment of relatedness significantly predicted a positive touch experience, which underlines the importance of touch-related practices for need fulfilment. According to the exponentiated coefficient (Exp(B) in ) of relatedness, for every standard deviation increase in relatedness, the odds that the touch experience was positive are six times higher. Initiative, interaction partner and the physical characteristics of the touch roughness, intensity and humidity were also significant predictors. According to the regression coefficients, mutually-initiated touch experiences are 7 times more likely to be a positive than a negative experience (Exp(B) = 7.26), and a touch experience which involved a friend, partner or a family member was four times more likely to be positive (Exp(B) = 4.39). The exponentiated regression coefficients of roughness, intensity and humidity were greater than two which indicates that every standard deviation increase of these variables will double the odds of a positive touch experience. Hence, damp, intense and rough touch is more likely to be categorised as a positive experience. When following up this rather unintuitive result it appears as if it was driven by touch experiences involving partners and close friends.

To test the hypothesis that need fulfilment is a better predictor of the touch experience’s valence than physical characteristics, the prediction power of the two blocks of variables was compared by computing the Cox & Snell R2 with the base model as the null model. The Cox & Snell R2 for physical characteristics was 0.24 with five degrees of freedom which shows that physical characteristics increase the explained variance of the base model by 24%. The Cox & Snell R2 for need fulfilment was 0.23 with nine degrees of freedom which shows that need fulfilment increases the explained variance of the base model by 23%. Calculated with a bootstrap approach, the 95% nonparametric confidence interval for the difference between these R2 values was −0.07 and 0.11. Thus, we cannot conclude that need fulfilment is a better predictor of touch valence than physical touch characteristics, but that both equally and individually contribute to the valence.

| (5) | Relationship between need fulfilment and affect resulting from touch experiences | ||||

For positive experiences, the fulfilment of each need was correlated with positive affect with a correlation in the range from 0.341 to 0.725 (Pearson correlation, mean correlation following Fisher-z transformation r = 0.613). The same held true for negative experiences (Pearson correlation: 0.334–0.522, mean r = 0.433). All pairwise correlations were significant after Bonferroni correction for multiple testing (see Table S9 in Supplementary Materials). Hence, the linear association between need fulfilment and positive affect was slightly stronger when the experience described was positive than when it was negative.

In positive touch experiences, self-esteem was negatively correlated with negative affect, i.e. the lower fulfilment of self-esteem is associated with higher negative affect (Pearson correlation coefficient = −0.244). None of the other pairwise correlations were significant.

These results indicate that, regardless of the experience type, satisfied need fulfilment is moderately associated with increased positive affect, but that non-satisfied (lower) need fulfilment is only weakly associated with negative affect.

Discussion

The two studies investigated how need fulfilment, physical characteristics, the interaction partner and situational characteristics determine positive and negative touch experiences. As one of these determinants, we were interested in the extent to which the touch fulfils different psychological needs. We hypothesised that a greater degree of need fulfilment from interpersonal touch would be related to higher positive affect and lower negative affect. We also hypothesised that need fulfilment can predict whether a touch experience is positive or negative, and that need fulfilment would be a better predictor than physical characteristics of the touch.

In addition to need fulfilment and physical features of the touch, further characteristics were extracted from the descriptions of the respective touch experiences: types of touch, body sites that were touched, locations where the touch experience took place, the assumed intention behind the touch, and the stated reason why the touch was positive or negative.

Which attributes of a touch convey its valence?

All touch types that occurred during positive experiences also occurred during negative experiences, however, the touch types during negative experiences appeared to be more varied. This was reflected in a more even distribution of touch types (study 2) and when naming a set of touch types only for negative experiences (study 1). In general, the type of touch alone did not give sufficient information about whether a touch experience was positive or negative, with the exception of a number of touch types named for negative experiences only, such as slapping or pushing by. This result underlines that a particular type of touch, such as slow stroking, is not pleasant per se. Recent studies tried to pinpoint which type of touch individuals prefer in a limited number of situations measured in the lab, e.g. handholding or stroking (Sened et al., Citation2023). These authors concluded that handholding is preferred over stroking for emotion regulation. Results from the current study indicate that preferences obtained in a very limited number of situations in the lab have to be treated with caution, and that individual preferences could turn into the opposite from situations to situation.

There were also no body areas specific to positive or negative touch experiences, but several areas that were only mentioned in negative touch experiences, such as the leg and foot (study 1). However, we should bear in mind that participants only rated the most negative and most positive experience within a specific timeframe, and that there may have been instances of positive touch on the foot that simply did not fulfil the “most positive” touch criterion. Conversely, mildly pleasant experiences could have been categorised as the “most positive” touch experience if there were no other experiences that were more enjoyable than that particular one.

Negative touch experiences happened more often in public and or at work places. However, positive and negative experiences could happen at the very same place (e.g. in the kitchen).

Altogether, each of these touch features by itself is not sufficient to distinguish between positive and negative experiences. This is similar to findings from Jones and Yarbrough (Jones & Yarbrough, Citation1985) who concluded that the meaning of a specific touch can only be understood by taking into account many different variables. In their study, information about body parts, who initiated the touch, type of touch, relationship, purpose, whether the touch was accompanied by a verbal statement, and how it was received was combined to identify six different categories of meaningful touch: (1) Positive affect touches (expressions of affection) with the subcategories support, appreciation, inclusion, sexual, affection, (2) playful touches (joking, teasing) with the subcategories playful affection and playful aggression, (3) control touches intended to influence the interaction partner with the three subcategories compliance, attention-getting, announcing a response, (4) ritualistic touches with the two sub-categories greeting and departure, (5) hybrid touches with the subcategories greeting/affection, departure/affection, and (6) task-oriented touches (during a particular task, e.g. inspecting someone’s clothing) with the three subcategories reference to appearance, instrumental ancillary, instrumental intrinsic, and (7) accidental touches. Thus, in order to determine which type of touch would be preferred given a particular situation, all these features would need to be integrated.

In contrast to the type of touch, the body part and the physical place, the assumed intentions and the reasons for why a touch was positive differed largely from those experienced as negative. Both factors specify the “why” (Morrison, Citation2023) or meaning (Sailer & Leknes, Citation2022) of a touch. The reasons why a touch experience was positive or negative varied widely. Not wanting to be touched (study 2) or wanting something else in that very situation (study 1) were cited as common reasons why touch was negative. Physical characteristics of touch (e.g. the limpness or wetness of a handshake) seemed to play a central role in negative but not in positive touch experiences. Participants sometimes gave several reasons for the valence of the same touch, and these could be on different levels, for example, “It made me feel wanted and warm and fuzzy on my skin.” or “It was from a person who I didn't like and they were unclean”; both quotes from study 2. Altogether, the data indicate that the assumed intention of a touch and the reasons individuals give are more indicative of its valence than where it took place, the general touch type or body part touched. Nevertheless, it needs to be kept in mind that participants state what they think are their reasons, and individuals do not always have access to these reasons (Wilson et al., Citation1993).

The role of need fulfilment and physical characteristics for touch valence

Positive and negative experiences differed significantly in the extent to which all nine psychological needs were fulfilled, with higher fulfilment of all needs in positive experiences. In line with previous studies, higher need fulfilment was related to positive affect. This was true for both negative and positive touch experiences. Need fulfilment was also related to reduced negative affect. This effect of touch was also mentioned in the open answers as one reason for why the touch was positive (Table S3), for example when the participant reported to have been sad and crying, and partner touch made them feel “accepted, understood, secure”. Overall, in line with our assumption, the fulfilment of needs increased positive affect and decreased negative affect. Previous studies have shown that responsive partner touch (Debrot et al., Citation2014), and touch in general is an important means of emotion regulation (e.g.; Eckstein et al., Citation2020; Rodriguez & Kross, Citation2023; Sened et al., Citation2023). Touch that fulfils certain needs and thereby increases positive affect could be a mechanism by which it contributes to subjective well-being at least in close and intimate relationships. Note, however, that the relationship between need satisfaction and affect was correlative and therefore the data do not allow for causal conclusions.

From all the needs, only the fulfilment of the need for relatedness significantly predicted a positive touch experience in study 2. This shows the importance of touch within everyday practices to nurture and fulfil the need for relatedness. This may not be surprising as touch is present in almost all close relationships, and one important function of interpersonal touch is to establish, maintain and strengthen relationships (Dunbar, Citation2010; e.g.; Gallace & Spence, Citation2010; Hertenstein, Verkamp, et al., Citation2006; Jablonski, Citation2021). Along these lines, relationship quality is an important modulator of the effects of interpersonal touch (Jakubiak, Citation2022). In their study, both low and high relationship satisfaction individuals benefited from touch, but the benefit was greater when relationship satisfaction was at least moderate. Similarly, participants who rated the quality of their relationship as high, experienced more stress alleviation from touch by the partner than those who rated it as low (Liu et al., Citation2021), and relationship satisfaction predicted touch pleasantness of both the touch received from and given to the partner (Triscoli et al., Citation2017). These studies emphasise the close interconnectedness of attributes of touch with the relationship in which they occur. Related to this, touch with the partner, friend or family member was more likely to be positive than touch with a colleague, acquaintance or a stranger. This echoes recent data where imagined touch with the partner was ascribed more positive intentions, and elicited more positive emotions than when participants had someone else in mind (Krahé et al., Citation2023 PREPRINT). Similar to this, participants in a different study reported to be more comfortable with touch from a partner or close person than a distant unknown person (Schirmer, Cham, Zhao, et al., Citation2023).

A further important contribution to positive touch was who initiated the touch, where mutually initiated touch was much more likely to be positive than self- or other-initiated touch. This highlights the importance of agency. Whereas previous studies from a non-social lab context suggest that agency is in itself rewarding (Eitam et al., Citation2013; Karsh & Eitam, Citation2015), in the social context of touch the mutual initiation was more decisive for a positive experience than self-initiation. During social interaction, mutual behaviour in the sense of similar behaviours displayed by the interaction partners signals mutual understanding and is related to social support. Interactions run more smoothly when the participants show similar behaviours, and mutuality contributes to the liking between the interaction partners (Chartrand & Bargh, Citation1999). This effect worked even when the interaction partner was a virtual agent (Bailenson & Yee, Citation2005). When evaluating video-taped touch interactions, the initiator of touch was perceived as more powerful and dominant than the touch receiver, even if the touch was reciprocated (Goldberg & Katz, Citation1990). The present results suggest that touch initiation and mutuality are also crucial for the positive experience of received touch.

In addition to these psychological factors, several physical touch characteristics were additionally able to predict whether a touch experience was positive or negative, namely humidity, intensity and roughness. This finding differs from the qualitative reports where physical characteristics of touch (e.g. the limpness or wetness of a handshake) were frequently named as reason for negative but not positive touch experiences. It is possible that this difference is due to the answer format. Physical characteristics may not be as salient as other aspects of the touch and therefore only be named if they are explicitly asked for. For example, the relief of being reunited with a family member after a long absence may be more salient than the fact that the hug was intense. Thus, these positive aspects may not be named in questions with open-answer format.

Interestingly, positive touch involved humid, intense and rough touch. In previous studies, humidity/dryness was often assessed in the form of high friction. Ratings of dryness are negatively correlated with friction (Chen et al., Citation2009). When touching different materials, pleasantness decreases with friction (Gwosdow et al., Citation1986; Klöcker et al., Citation2013). These findings fit the results of the present study, where damper (less dry) touch predicted a positive touch experience. Friction is also closely related to the perception of roughness, where roughness is correlated with higher friction and smoothness is correlated with lower friction (Chen et al., Citation2009; Ekman et al., Citation1965). Many studies have shown that smoother materials are typically rated as more pleasant (Ekman et al., Citation1965; Essick et al., Citation2010; e.g.; Etzi et al., Citation2014; Major, Citation1895; Ripin & Lazarsfeld, Citation1937; Schirmer, Cham, et al., Citation2023; Verrillo et al., Citation1999; Wijaya et al., Citation2020). However, one previous study also found rougher stroking to be more pleasant than smoother stroking (Sailer et al., Citation2020).

In contrast to previous studies where pleasantness ratings decreased with stimulus intensity (e.g.; Schirmer, Cham, Zhao, et al., Citation2023), intensity in the current study was associated with the positivity of a touch experience. Contrary to these controlled laboratory studies, the touches assessed in the present studies could be of a wide variety of types and could occur with a range of different interaction partners. Although our data were not sufficiently powered to examine this statistically, it is possible that roughness and intensity are positive aspects as long as a close partner is involved. Consistent with this interpretation, in participants who reported touch interactions in daily life, momentary happiness increased with the intensity of affectionate touch (Schneider et al., Citation2023).

Limitations

The studies have a number of limitations. First, they were based on retrospective self-report which is susceptible to various biases, including but not limited to recall biases (e.g.; Reis & Wheeler, Citation1991). Because participants were asked to recollect the most positive and negative touch experience in a given time interval, the answers were biased towards the most salient experiences. A further selection bias may have arisen in study 1 due to the exclusion of touch that occurred during sexual activity. Considering that sexual touches can elicit both intense pleasure and extreme discomfort, it would be expected that sexual touch would have been frequently mentioned if it hadn't been excluded. Surprisingly, in study 2, where participants were free to report experiences during sex, only a minimal number of such events were mentioned. One possible explanation for this finding is that the likelihood of sexual touches was lower in study 2 than in study 1. This could be attributed to the fact that study 1 specifically targeted participants in relationships, while study 2 did not have such a requirement. Another possibility is that touch events during sexual activity might not be the primary source of both positive and negative touch experiences in daily life. If this is the case, then the restriction in study 1 probably did not strongly bias the selection of touch experiences.

Second, in study 1, participants were asked to report their touch experiences after a week of counting every touch event. This approach could have potentially heightened the significance of minor touch experiences, making them more salient in participants’ perceptions. Third, study 1 showed a trade-off between questionnaire-length and reliability. Whereas the shorter version was more practical, reliability on some scales was low. Thus, future studies should not shorten Sheldon’s Needs questionnaire. Fourth, although we investigated the role of several determinants for touch, the list of determinants considered was not complete. For example, attachment avoidance is known to play a role in touch experience (Keizer et al., Citation2022; Krahe et al., Citation2018; Krahé et al., Citation2023). However, this may be reflected in different needs of the participants such as a lower need for relatedness (Jakubiak, Debrot, et al., Citation2021; Jakubiak, Fuentes, et al., Citation2021), and therefore be covered indirectly. Future studies should investigate the role of further person and situation factors as well as characteristics of the touch provider that can influence touch perception (for reviews, see e.g. Ellingsen et al., Citation2016; Saarinen et al., Citation2021). Fifth, the generalizability of the results may be limited as our samples were comprised predominantly of Western European participants.

Implications

The results have implications for our understanding of touch perception and developments of haptic technology. Whereas the type of touch (stroking, tapping) in itself was not indicative of the resulting experience, certain physical characteristics of the touch (e.g. humidity) were important. This suggests that instead of aiming for an exact replication of a specific type of human touch, touch technology should prioritise getting the physical aspects right. This may also be possible for touch types considered “artificial” such as vibration. Furthermore, the relevance of relatedness and mutuality for a positive touch experience suggest that more emphasis should be given to these aspects of touch interactions. For technology development, the importance of mutuality suggests that inventions of remote touch should include a self-initiated element. Furthermore, our results indicate that emphasis should be put on clearly communicating the intention of the touch when using mediated touch, and meeting the momentary need of relatedness. For example, mediated and artificial touch may have more positive effects it if is associated with a close person. In other words, technologies to mediate intimate touch may need to be dedicated to, that is, clearly associated with a particular person.

Conclusion

Our data illustrate the complexity of interpersonal touch in everyday life. They show that “tactile” features of a touch, such as the touch type and the body site touched, are not decisive for the valence of a touch experience. Instead, the following three aspects were important for the experienced valence of a touch (1) need fulfilment, in particular of the need for relatedness, (2) meaning-making aspects such as the assumed intention and those reflected in the verbal reasons given, (3) certain physical characteristics of the touch itself. These findings highlight the importance of the “context” for touch experience.

Author contribution statement

Original idea and design of study 2: Uta Sailer (US) and Marc Hassenzahl (MH). Design of study 1: US, Yvonne Friedrich (YF) and Ilona Croy (IC). Data collection: YH (study 1), US (study 2). Data analysis: Fatemeh Asgari (FHA) and US. US wrote the first draft. All authors contributed to article writing.

Declaration of interest statement

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Supplements_needs_man_061223.docx

Download MS Word (526.2 KB)Acknowledgements

Study 2 was supported by grant 16SV9108 of the German Federal Ministry for Research and Education, project VEREINT. US was also supported by ERA-NET-NEURON, JTC 2020/Norwegian Research Council (grant number 323047), and a Jena Excellence Fellowship. IC was supported by ERA-NET-NEURON, JTC 2020/DRL (grant number 01EW2105). We thank Andreas Lie Massey for his assistance with various manuscript preparation tasks, including the creation of and . We also thank Marie Hoffmann for help with data collection in study 1, and Trond Farestveit Erstad for preparing Figure S1.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ackerley, R., Backlund Wasling, H., Liljencrantz, J., Olausson, H., Johnson, R. D., & Wessberg, J. (2014). Human C-tactile afferents are tuned to the temperature of a skin-stroking caress. The Journal of Neuroscience, 34(8), 2879–2883. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2847-13.2014

- Ackerley, R., Carlsson, I., Wester, H., Olausson, H., & Backlund Wasling, H. (2014). Touch perceptions across skin sites: Differences between sensitivity, direction discrimination and pleasantness. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience, 8, 54. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnbeh.2014.00054

- App, B., McIntosh, D. N., Reed, C. L., & Hertenstein, M. J. (2011). Nonverbal channel use in communication of emotion: How may depend on why. Emotion, 11(3), 603–617. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0023164

- Argyle, M., & Dean, J. (1965). Eye-contact, distance and affiliation. Sociometry, 28(3), 289–304. https://doi.org/10.2307/2786027

- Aron, A., Aron, E. N., & Smollan, D. (1992). Inclusion of other in the self scale and the structure of interpersonal closeness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 63(4), 596–612. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.63.4.596

- Bailenson, J. N., & Yee, N. (2005). Digital chameleons. Psychological Science, 16(10), 814–819. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2005.01619.x

- Beßler, R., Bendas, J., Sailer, U., & Croy, I. (2020). The “longing for interpersonal touch picture questionnaire”: Development of a new measurement for touch perception. International Journal of Psychology, n/a(n/a), https://doi.org/10.1002/ijop.12616

- Brandstätter, H. (1994). Well-being and motivational person-environment fit: A time-sampling study of emotions. European Journal of Personality, 8(2), 75–93. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.2410080202

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 11(4), 589–597. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806

- Case, L. K., Liljencrantz, J., McCall, M. V., Bradson, M., Necaise, A., Tubbs, J., Olausson, H., Wang, B., & Bushnell, M. C. (2021). Pleasant deep pressure: Expanding the social touch hypothesis. Neuroscience, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroscience.2020.07.050

- Case, L. K., Madian, N., McCall, M. V., Bradson, M. L., Liljencrantz, J., Goldstein, B., Alasha, V. J., & Zimmerman, M. S. (2023). Aβ-CT affective touch: Touch pleasantness ratings for gentle stroking and deep pressure exhibit dependence on A-fibers. Eneuro, 10(5), ENEURO.0504-22.2023–22.2023. https://doi.org/10.1523/ENEURO.0504-22.2023

- Chartrand, T. L., & Bargh, J. A. (1999). The chameleon effect: The perception-behavior link and social interaction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 76(6), 893–910. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.76.6.893

- Chen, X., Barnes, C. J., Childs, T. H. C., Henson, B., & Shao, F. (2009). Materials’ tactile testing and characterisation for consumer products’ affective packaging design. Materials & Design, 30(10), 4299–4310. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matdes.2009.04.021

- Cohen, J. (1977). Chapter 9—F tests of variance proportions in multiple regression/correlation analysis. In J. Cohen (Ed.), Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (pp. 407–453). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-179060-8.50014-1

- Croy, I., Luong, A., Triscoli, C., Hofmann, E., Olausson, H., & Sailer, U. (2016). Interpersonal stroking touch is targeted to C tactile afferent activation. Behavioural Brain Research, 297, 37–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbr.2015.09.038

- Debrot, A., Schoebi, D., Perrez, M., & Horn, A. (2014). Stroking your beloved one's white bear: Responsive touch by the romantic partner buffers the negative effect of thought suppression on daily mood. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 33(1), 75–97. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2014.33.1.75

- Debrot, A., Schoebi, D., Perrez, M., & Horn, A. B. (2013). Touch as an interpersonal emotion regulation process in couples’ daily lives. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 39(10), 1373–1385. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167213497592