?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Nature contact has associations with emotional ill-being and well-being. However, the mechanisms underlying these associations are not fully understood. We hypothesised that increased adaptive and decreased maladaptive emotion regulation strategies would be a pathway linking nature contact to ill-being and well-being. Using data from a survey of 600 U.S.-based adults administered online in 2022, we conducted structural equation modelling to test our hypotheses. We found that (1) frequency of nature contact was significantly associated with lesser emotional ill-being and greater emotional well-being, (2) effective emotion regulation was significantly associated with lesser emotional ill-being and greater emotional well-being, and (3) the associations of higher frequency of nature contact with these benefits were partly explained via emotion regulation. Moreover, we found a nonlinear relationship for the associations of duration of nature contact with some outcomes, with a rise in benefits up to certain amounts of time, and a levelling off after these points. These findings support and extend previous work that demonstrates that the associations of nature contact with emotional ill-being and well-being may be partly explained by changes in emotion regulation.

Nature contact appears to benefit mental health in many cases, with effects that not only buffer against psychopathology and emotional ill-being, but also increase emotional well-being (Becker et al., Citation2019; Bratman et al., Citation2019; Frumkin et al., Citation2017; Markevych et al., Citation2017; White et al., Citation2021). Prior research suggests that emotional ill-being and well-being are not simply mirror images of one another and may have different antecedents and consequences (Huppert, Citation2009; Ryff et al., Citation2006; Suldo & Shaffer, Citation2019). Emotional ill-being refers to facets of poor psychological functioning, which, in the extreme, may include psychopathology but also includes subclinical states characterised by negative affect and perceived stress (Ryff et al., Citation2006). In contrast, emotional well-being refers to facets of psychological functioning that includes positive feelings in general, subjective evaluations about life, as well as momentary positive affect (Park et al., Citation2022). Research to date has linked nature contact with both lower emotional ill-being and higher emotional well-being, based on findings derived from a broad range of study designs, ranging from controlled experiments to large-scale observational studies (Bratman et al., Citation2012; Gascon et al., Citation2017; Hartig et al., Citation2014; Holland et al., Citation2021). Many studies document these associations, but what is less clear are the pathways through which these effects occur.

In the following sections, we first summarise findings concerning the association of nature contact with emotional ill-being and well-being. Next, using structural equation modelling with cross-sectional data, we investigate a candidate set of mediators that has been explored in some intriguing prior work on the associations of nature contact with emotional ill-being and well-being. These include emotion regulation strategies (Bratman, Olvera-Alvarez, et al., Citation2021; Johnsen, Citation2013; Johnsen & Rydstedt, Citation2013; Korpela, Citation1989, Citation2003; Korpela et al., Citation2001; Korpela et al., Citation2010; Korpela et al., Citation2018; Korpela et al., Citation2020; Korpela & Hartig, Citation1996; Korpela & Kinnunen, Citation2011; Richardson, Citation2019), which we define broadly as the processes through which individuals manage and influence their emotions (McRae & Gross, Citation2020). To do this, we administered a survey to a large sample of U.S. adults and then examined the role of emotion regulation in the relationship between nature contact and emotional ill-being and well-being outcomes.

Prior evidence for nature contact and emotional ill-being and well-being

Prior studies have demonstrated that nature contact is associated with many aspects of emotional ill-being and well-being (Bratman, Olvera-Alvarez, et al., Citation2021; Hartig, Citation2021; Hartig et al., Citation2003; Ulrich et al., Citation1991; White et al., Citation2017). This work has demonstrated higher levels of hedonic well-being and decreased states of anxiety occur directly after nature contact, as well as higher eudaimonic well-being and lower levels of chronic stress among people with generally high versus lower levels of nature contact (Bratman et al., Citation2012; Bratman et al., Citation2019; Hartig et al., Citation2014; Holland et al., Citation2021; Markevych et al., Citation2017; Marselle et al., Citation2021; White et al., Citation2021). Studies within either a laboratory or ecologically valid outdoor settings have consistently demonstrated short-term impacts of nature contact on changes in affect and anxiety (Annerstedt et al., Citation2013; Aspinall et al., Citation2015; Berman et al., Citation2008; Berman et al., Citation2012; Bratman, Daily, et al., Citation2015; Watkins-Martin et al., Citation2022), while studies using data from large-scale cohorts or other existing data have demonstrated stable associations of nature contact measured at a single point in time with lower likelihood of developing depression or experiencing perceived stress subsequently, and with higher levels of mental well-being later in life (Banay et al., Citation2019; Besser et al., Citation2020; Bezold et al., Citation2018; de Vries et al., Citation2003; Maas et al., Citation2006; Mitchell et al., Citation2015; Roe et al., Citation2013; White et al., Citation2013; White et al., Citation2021).

Two relevant aspects of nature contact for these associations are the frequency and duration of contact. Emerging work has demonstrated that frequency of nature contact may be associated with different ill-being and well-being outcomes than duration (Shanahan et al., Citation2016). For example, higher annual frequency of visitation to nature may be more important for establishing social bonds and cohesion, whereas higher duration of an average visit may be more relevant for decreasing the risk of depression (Shanahan et al., Citation2016). Additionally, other research has suggested that evaluations of the association of duration of nature contact with affective outcomes should consider non-linear relationships (White et al., Citation2019). Accordingly, here we explored the possibility that weekly duration of nature contact may be significantly associated with emotional ill-being and well-being up to a certain amount (i.e. a “breakpoint”), after which benefits accrue very little, if at all.

As with the health impacts of other environmental exposures, a dose-response relationship of duration of nature contact with affective outcomes could reflect a non-linear relationship in which each increment of exposure duration is not associated with the same amount of change in dependent variables. Instead, initial units of exposure could be associated with significant amounts of change in one direction up until a breakpoint, past which the slope of the dose-response curve can shift, level off, or change direction. The notion of a breakpoint is motivated by substantial work from a variety of disciplines that employ an exposure-response approach to emotional ill-being and well-being, including media use (Twenge & Campbell, Citation2019), noise (Dratva et al., Citation2010), heat (Heaney et al., Citation2019), and other types of studies that assess population-level psychological well-being over time (Zhang et al., Citation2023). It is also supported by work from the physical activity literature, in which non-linear associations between duration of activity and improvements in health have been observed (e.g. physical activity and cardiovascular disease), with effects observed up to a certain amount, and little additional benefit afterward (Li et al., Citation2021).

Nature contact includes various patterns of human-nature interactions and experiences (e.g. looking at vs. swimming in water) (Kahn et al., Citation2010; Weiss et al., Citation2023) and the types of nature with which the contact occurs (e.g. open meadow vs. dense forest) (Barnes et al., Citation2019; Marselle et al., Citation2021; Wheeler et al., Citation2015; White et al., Citation2017). Across many of these dimensions, studies have found consistent evidence that nature contact has benefits for emotional ill-being and well-being. This growing body of evidence gives rise to a question of how nature contact drives these effects. One candidate mediator is emotion regulation, which refers to the processes that influence the emotion trajectory.

Emotion regulation and emotional ill-being and well-being

According to the process model of emotion regulation, five families of emotion regulation strategies can be distinguished (Gross, Citation1998, Citation2015; Gross & John, Citation2003; McRae & Gross, Citation2020). These strategies can be employed, consciously or unconsciously, to up- or down-regulate negative or positive affect (Gross, Citation1998; Gross et al., Citation2019; McRae & Gross, Citation2020; Quoidbach et al., Citation2015). Tendencies to engage in these processes have been examined and described extensively at the individual level, including factors related to age or developmental stage (Helion et al., Citation2019; John & Gross, Citation2004), gender (Nolen-Hoeksema, Citation2012), personality (Gross & John, Citation2003; Ng & Diener, Citation2009), and genetics (McRae et al., Citation2017). Recent work investigates temporal aspects of these processes as well, with the recognition that engaging multiple strategies, concurrent or sequential, often occurs during a single emotion episode (Ford et al., Citation2019). One crucial finding from this literature is that different forms of emotion regulation can have quite different affective consequences.

Here, we focus on two of these families of strategies: attentional deployment and cognitive change. The first family of strategies, the attentional deployment strategies, involves the choice of how to direct attention to a specific aspect of a situation. Such choices, such as distraction and rumination, can alter the emotional impact of the situation due to the content that is either avoided or to which attention is directed. The second family of strategies, cognitive change, including the commonly used strategy of reappraisal, refers to the interpretation and construction of meaning that an individual creates from a set of stimuli or situations. A third family of strategies, situation selection, refers to the process by which an individual makes a choice between two or more situations (e.g. places or people) with which to interact. This family of regulation strategies is relevant because prior work has shown that people select and seek out natural environments as preferred places to be for restoration (Hartig, Citation2021; Hartig et al., Citation1997; Korpela et al., Citation2001; Korpela et al., Citation2020; Korpela & Hartig, Citation1996). However, although we posit that it may be a predictor of nature contact, it was not the primary focus of our investigation, nor did we include situation selection as a candidate mediator, therefore we considered it in a supplemental analysis (see Supplemental Materials for discussion of these findings).

Attentional deployment and cognitive change strategies have been shown to impact emotional ill-being and well-being (Gross, Citation2015). Distraction can play adaptive or maladaptive roles with respect to promoting well-being, depending on aspects of timing and context (Young & Suri, Citation2020). Here we focus on hypotheses related to the adaptive form (Waugh et al., Citation2020; Wolgast & Lundh, Citation2017). This includes, for example, distracting oneself from high-intensity, negative stimuli in the short term (i.e. a typically adaptive form of distraction). We also focus on another primarily adaptive form of emotion regulation, reappraisal, which has been shown to often lead to emotional ill-being and well-being benefits (Gross & John, Citation2003). Finally, the last form of emotion regulation we assessed, a form of attentional deployment towards negative aspects of the self, known as rumination, has been shown to be primarily maladaptive (with some exceptions), leading to increased negative affect and emotional ill-being (Moberly & Watkins, Citation2008, Citation2010).

Emotion regulation as a mediator between nature contact and emotional ill-being and well-being

Interaction with natural environments may lead to affective outcomes by encouraging increases in generally adaptive emotion regulation strategies and/or decreases in generally maladaptive ones (Bratman, Young, et al., Citation2021; Korpela & Hartig, Citation1996; Korpela, Citation1992; Korpela et al., Citation2018; Tester-Jones et al., Citation2020). As with other effects from nature experience – such as the cognitively restorative processes that stem from bottom-up processing of natural stimuli (Kardan et al., Citation2015; Menzel & Reese, Citation2021) – emotion regulation processes can be impacted without one’s conscious awareness of these effects (Koole et al., Citation2015). For example, going for a walk in a natural setting may replenish cognitive resources in a way that allows for effective reappraisal of a problem in a subsequent, difficult conversation with a colleague. Or a natural setting may be picked as a destination in a non-deliberate way, but nonetheless result in affective benefits, despite an individual not consciously anticipating these effects (Nisbet & Zelenski, Citation2011).

Attentional deployment

Attention has been defined as a process in which an individual selects, focuses, and magnifies selected stimuli (Wadlinger & Isaacowitz, Citation2011; Wallace, Citation1999). Internal or external direction of attention towards or away from stimuli or events can have adaptive or maladaptive consequences for emotional ill-being and well-being (Gross, Citation2015; Wolgast & Lundh, Citation2017; Woodward et al., Citation2019). Distraction and rumination are both examples of regulation strategies that involve different types of attentional deployment (McRae & Gross, Citation2020). Distraction entails redirecting one’s attention away from a stimulus and onto something unrelated to it (Gross, Citation2015). This can be adaptative in the short term, especially when faced with high-intensity, negative stimuli (Sheppes et al., Citation2014). Rumination refers to a type of attention that is self-referential, negative, and focused on past decisions and actions. It is typically considered a maladaptive strategy, often associated with negative affective consequences (Aldao & Nolen-Hoeksema, Citation2010; Genet & Siemer, Citation2012; Joormann & Gotlib, Citation2010; Nolen-Hoeksema, Wisco, & Lyubomirsky, Citation2008).

Time spent in natural environments may influence the allocation of attention in ways that are relevant to both distraction and rumination. For example, natural environments may contain stimuli (e.g. songbirds in a meadow) that capture our involuntary attention (Kaplan, Citation1995). They may have characteristics such as perceived beauty, or opportunities for activities that distract and then hold attention away from a focus on appraisal of the self and onto healthy connection with others (Hartig, Citation2021; Jiang, Citation2020; Zhang et al., Citation2014), thereby leading to beneficial affective results. In line with this, a small body of growing research also supports the notion that nature contact reduces rumination (Bratman, Daily, et al., Citation2015; Bratman, Hamilton, et al., Citation2015; Bratman, Young, et al., Citation2021; Lopes et al., Citation2020). Therefore, we posit that higher frequency and longer duration of nature contact will be associated with increased adaptive distraction and decreased maladaptive rumination.

Cognitive change

Natural environments may provide a variety of affordances for adaptive cognitive change, which we operationalised as reappraisal. By affordances, we mean the latent possibilities that an environment provides for action (Gibson, Citation1977; Norman, Citation1999; Suri et al., Citation2018). For example, exposure to contextual cues and characteristics of natural environments may encourage original thinking through the encouragement of explorative thought (Nelson & Guegan, Citation2019), or restore directed attention through the engagement of “soft fascination” (Kaplan, Citation1995; Kaplan & Kaplan, Citation1989). This can contribute to increased capacity for reflection on problems (Basu et al., Citation2019; Hartig et al., Citation1996; Herzog et al., Citation1997; Korpela et al., Citation2020; Mayer et al., Citation2009) and to transform negative emotions into positive ones (Korpela et al., Citation2020; Korpela & Ylen, Citation2007). Though our focus here is on nature, environments other than natural ones may also provide these affordances (e.g. museums or certain healthcare settings) (Collado et al., Citation2017; Joye & van den Berg, Citation2018; Kaplan et al., Citation1993).

Nature contact may also increase creativity and associations between previously unconnected ideas and concepts (Williams et al., Citation2018) – characteristics of thinking that are associated with effective reappraisal (Fink et al., Citation2017). Many of these shifts in thought processes are in line with a “broadening and building” of our thinking (Fredrickson, Citation2001) that can occur through initial positive affective reactions to natural environments (Ulrich et al., Citation1991). Ultimately these shifts could lead to a reconsideration of relationship to objectives, or changes in determinations of “what is good for me” vs. “what is bad for me” (Lazarus, Citation1984). For example, being present in nature might change a set of goals and reorient perspectives through bonding and connection with a social group (Hartig, Citation2021; Littman et al., Citation2021). This prior evidence and theory support our hypothesis that higher frequency and greater duration of nature contact will be associated with increased adaptive reappraisal.

The present study

In this study, we used self-report data from a survey that was distributed via Prolific, an online research platform that provides services for participant recruitment. We opted for a sampling strategy that aims to be nationally representative on age, sex, and race, as defined by Prolific, in which they stratify samples across these categories using U.S. Census Bureau subgroups as the reference for national population proportions with respect to age, sex, and race subgroups. We used this cross-sectional sample to test our pre-registered hypotheses regarding (1) the association of nature contact with emotional ill-being and well-being, (2) the association of two families of emotion regulation strategies (attentional deployment and cognitive change) with emotional ill-being and well-being, and (3) the degree to which attentional deployment (i.e. distraction and rumination) and cognitive change (i.e. reappraisal) explain the association of nature contact with emotional ill-being and well-being via structural equation modelling.

We measured two distinct aspects of nature contact – frequency and duration – given the evidence that different outcomes may be associated with each (e.g. annual frequency vs. duration of a given visit; (Shanahan et al., Citation2016)). Our frequency measure used a 9-point ordinal scale that assessed number of visits ranging from never to once a month to 6–7 days a week. Our duration measure was continuous, ranging from 0 to 100 hours per week. We expected a non-linear dose-response relationship to exist for both duration and frequency, but our measure of frequency is itself a non-linear ordinal scale, while the measure of duration is a linear scale. Thus, while the underlying construct may be non-linear, we expected the responses on the non-linear frequency scale to exhibit a linear relationship with outcomes. We explored the possibility that a saturation or “breakpoint” may exist for the association of weekly duration of nature contact with emotional ill-being and well-being and emotion regulation strategies, up to which benefits accrue, and past which they level off. Below we lay out our hypotheses with respect to frequency and duration of nature contact.

H1a: frequency of nature contact is associated with emotional ill-being and well-being

We hypothesise that frequency of nature contact will be linearly associated with lesser emotional ill-being and greater emotional well-being.

H1b: duration of nature contact is associated with emotional ill-being and well-being

We hypothesise that duration of nature contact (hours per week) will have a non-linear relationship with emotional ill-being and well-being, with beneficial associations accruing up and until a breakpoint, after which there will be little to no gains.

H2: emotion regulation is associated with emotional ill-being and well-being

We hypothesise that distraction and reappraisal will be linearly associated with lesser emotional ill-being and greater emotional well-being, and that rumination will be linearly associated with greater emotional ill-being and lesser emotional well-being.

H3a: frequency of nature contact is associated with use of adaptive versus maladaptive strategies for regulating emotions

We hypothesise that more frequent nature contact will be linearly associated with more use of adaptive emotion regulation strategies, including distraction and reappraisal, and with less use of the maladaptive emotion regulation of rumination.

H3b: duration of nature contact is associated with use of adaptive versus maladaptive strategies for regulating emotions

We hypothesise that duration of nature contact (hours per week) will be non-linearly associated with more use of adaptive emotion regulation strategies, including distraction and reappraisal, and with less use of the maladaptive emotion regulation of rumination, with beneficial associations accruing up and until a breakpoint, after which there will be little to no gains.

H4: emotion regulation mediates the link between frequency of nature contact and emotional ill-being and well-being

We hypothesise that frequency of cognitive distraction, rumination, and reappraisal will partially mediate the association of frequency of nature contact with emotional ill-being and well-being. Given the computational complexity of estimating breakpoints in a SEM, and the goal of keeping our SEM as parsimonious as possible, we chose to conduct the analysis of our full conceptual model using only the frequency measure of nature contact as the predictor.

Methods

Participants

Based on a general review of previous related studies on nature contact and affect, we planned to test our hypotheses with a sample of N = 600. Participants were recruited via collaboration with Prolific services and compensated $5 based on the 30-minute duration of the study. A total of 609 participants in the U.S., aged 18 and over, completed the study in January 2022 (see Supplemental Table 1 for descriptive statistics). Per the sampling approach conducted by Prolific, recruitment was stratified across age, sex, and race according to the following brackets and categorisations: 18–27, 28–37, 38–47, 48–57, and 58+; male and female; and White, Mixed, Asian, Black and Other. Prolific does not assess Hispanic or non-Hispanic ethnicity, so we included this additional question in our survey. Nine participants were excluded from the analysis due to failing more than one out of the four attention checks, leaving a total of 600 participants. Our survey successfully employed a forced-choice method, to avoid missingness in responses, so that our data were complete from all respondents. The University of Washington Human Subjects Division reviewed this project and determined that the activity qualified for exempt status.

Measures

Our self-report measures were designed to capture average, general levels of nature contact, frequency of engagement with emotion regulation strategies, and emotional ill-being and well-being.

Nature contact

Frequency and duration measures were developed for the purposes of this study, derived from operationalisations used in other nature exposure studies (Shanahan et al., Citation2016; White et al., Citation2019).

Frequency was measured using this question:

About how often do you usually visit or pass through outdoor natural areas for any reason? This includes, for example, walking, biking, or recreating outside in local, regional, or national parks, at the beach, beside or within lakes, creeks, or the ocean, gardening or tending to plants, camping, fishing, reading or walking outside next to trees, engaging in yard work with natural elements, etc…

Duration was measured using this question:

Over the last month, approximately how many HOURS PER WEEK do you consider yourself to have interacted with nature? This includes, for example, walking, biking, or recreating outside in local, regional, or national parks, at the beach, beside or within lakes, creeks, or the ocean, gardening or tending to plants, camping, fishing, reading or walking outside next to trees, engaging in yard work with natural elements, etc…

Emotion regulation

We assessed distraction using the validated 5-item disengagement attention deployment subscale of the Process Model of Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (PMERQ; Olderbak et al., Citation2022). The PMERQ is a recently developed questionnaire which measures the frequency of usage of different emotion regulation strategies in the process model of emotion regulation. Example items include “To feel less upset during upsetting situations, I divert my attention away from what is happening”. Participants are asked to indicate the extent to which they agree with each of the 5 statements on a 6-point Likert scale from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree” and a sum score for the subscale can be calculated (min = 5; max = 30). In the current study, this measure showed good internal consistency (α = .91).

We assessed rumination using a 5-item subscale from the validated Ruminative Responses Scale (RRS; Treynor et al., Citation2003). Items on this scale are designed to assess the brooding component of rumination (e.g. “I think ‘Why do I have problems other people don’t have?’”). Each item was rated on a 4-point scale, ranging from one (“never”) to four (“always”) from which a sum score can be calculated (min = 5; max = 20). In the current study, this measure showed good internal consistency (α = .82).

We assessed reappraisal using the 6-item engagement repurposing subscale of the PMERQ (e.g. “When something upsetting happens, to feel less upset, I think about the possible benefits of the situation”). Participants are asked to indicate the extent to which they agree with each statement on a 6-point Likert scale and a sum score can be calculated to evaluate the usage of each strategy (min = 6; max = 36). In the current study, this measure showed good internal consistency (α = .91).

Emotional ill-being and well-being

Emotional ill-being and well-being were assessed using measures of positive and negative affect, life satisfaction, purpose in life, and perceived stress (Ryff et al., Citation2006).

We assessed positive and negative affect using the 20-item Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS; Watson et al., Citation1988). This scale consists of twenty items with ten items assessing positive affect (e.g. “interested”, “active”) and negative affect (e.g. “distressed”, “irritable”) each, as experienced over the past month. Each item is rated on a 5-point scale, ranging from one (“very slightly or not at all”) to five (“extremely”) from which a sum score can be calculated (min = 10; max = 50 for positive affect and negative affect). In the current study, this measure showed high internal consistency for positive affect (α = .93) and negative affect (α = .92).

We assessed life satisfaction using the 6-item Life Satisfaction Scale (LSS; Margolis et al., Citation2019). This scale consists of six items designed to measure assessments of life satisfaction (e.g. “I like how my life is going”). Each item is rated on a 7-point scale, ranging from one (“strongly disagree”) to seven (“strongly agree”) from which a sum score can be calculated (min = 6; max = 42). In the current study, this measure showed good internal consistency (α = .91).

We assessed purpose in life using the 7-item scale from the Ryff Measures of Psychological Well-Being (PWB; Ryff, Citation1989). These items are designed to measure individuals’ evaluation of this aspect of their lives (e.g. “I have a sense of direction and purpose in life”). Each item is rated on a 6-point scale, ranging from one (“strongly disagree”) to seven (“strongly agree”) from which a sum score can be calculated (min = 7; max = 42). Three items are reverse scored so that higher scores on the overall measure indicate higher purpose. In this study, this measure showed good internal consistency (α = .84).

We assessed perceived stress using the 10-item version of the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS; Cohen et al., Citation1983). This scale consisted of ten items designed to assess feelings and perceptions of stress over the last month (e.g. “In the last month, how often have you felt nervous and “stressed”?”). Each item is rated on a 5-point scale, ranging from zero (“never”) to four (“very often”) from which a sum score can be calculated (min = 0; max = 40). In the current study this measure showed good internal consistency (α = .92).

Demographic and other covariates

Given limited evidence on relevant covariates in the context of nature contact and emotional ill-being and well-being, we included age, gender, education, and a measure of perceived socioeconomic status (MacArthur Scale of Subjective Social Status; Giatti et al., Citation2012) to assess where individuals feel they stand in comparison to others, as control variables in our regression and mediation analyses.

Open science statement

The preregistration for all primary hypotheses and our publicly available dataset and analysis scripts can be found at https://osf.io/zrg2w.

Analytic approach

To examine Hypothesis 1a, we fit linear regression models with frequency of nature contact as the predictor, an emotional ill-being or well-being measure as the outcome, and included covariates of age, gender, education, and perceived socioeconomic status. To examine Hypothesis 1b, we fit segmented regression models with duration of nature contact as the predictor, an emotional ill-being or well-being measure as the outcome (one model for each outcome), and included covariates of age, gender, education, and perceived socioeconomic status. We chose to use segmented regression models because we expected a nonlinear relationship between duration and our hypothesised outcomes. In other words, we expected that an increase of one hour per week of nature exposure would be more consequential to emotional ill-being and well-being for an individual going from zero to one hour per week vs. that person going from 15 to 16 hours per week, for example. The segmented regression model estimates different slopes for different intervals of the predictor (see EquationEquation 1(1)

(1) ). To determine where the slope of the line changes, the model estimates a breakpoint, ψ. In the context of this study, the breakpoint indicates the value of hours of nature contact per week where the relationship between hours in nature and the outcome variable changes in slope. We fit our models using the segmented package in R (Muggeo, Citation2008).

(1)

(1) The term β1xi gives the prediction,

, when the independent variable x for person i, (i.e. hours per week spent in nature for person i) is less than the breakpoint ψ. The term β2(xi – ψ)+ is added to β1xi if (xi – ψ) is greater than 0 (i.e. when the hours per week spent in nature is greater than the breakpoint).

To examine Hypothesis 2, we fit linear regression models with an emotion regulation strategy as the predictor, an emotional ill-being or well-being measure as the outcome variable, and included covariates of age, gender, education, and socioeconomic status.

To examine Hypothesis 3a and 3b with respect to the association of frequency and duration of nature contact with emotion regulation, we used the same approach as described above for Hypothesis 1a and 1b, respectively.

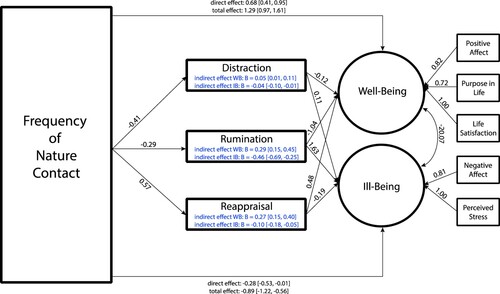

To examine Hypothesis 4, we fit a structural equation mediation model with frequency of nature contact as the predictor, each of the three emotion regulation strategies (distraction, reappraisal, and rumination) as mediators, and an ill-being composite and well-being composite as the two outcomes (see ). We chose to implement a structural equation model following recommendations regarding best practices for cross-sectional mediation modelling in the context of nature and well-being (Dzhambov et al., Citation2020). We implemented the models in MPlus version 8.8 (Muthén & Muthén, Citation1998–Citation2017). We used Bayesian estimation with non-informative default priors to estimate the parameters of the model (see https://osf.io/zrg2w for full model implementation). Data will be made available online once this and other studies using them have been published.

Figure 1. Bayesian structural equation model results with frequency of nature contact, emotion regulation, and emotional ill-being and well-being.

Notes: Bayesian structural equation model with mediation paths from nature contact to emotional ill-being and well-being outcomes via emotion regulation strategies. Unstandardised regression coefficients and factor loadings are labelled on the arrow for each path. Indirect effect estimates are contained within the box for each emotion regulation strategy. Direct and total effect estimates are labelled on the paths from nature frequency to ill-being and well-being. We determined significance by identifying whether the 95% Bayesian credible interval contained 0. Using this criterion, all paths were significant. IB = ill-being; WB = well-being.

Results

H1a: frequency of nature contact is associated with emotional ill-being and well-being

In support of our hypothesis, we observed significant associations between frequency of nature contact and lesser emotional ill-being and greater emotional well-being. See for all results.

Table 1. Emotional ill-being and well-being and emotion regulation outcomes in relation to frequency of nature contact.

H1b: duration of nature contact is associated with emotional ill-being and well-being

In support of our hypothesis, we observed that the association between weekly duration of nature contact and emotional ill-being and well-being was significant for the measures of well-being (positive affect (β1 = 1.73, p < .001), life satisfaction (β1 = 0.73, p = .002), and purpose in life (β1 = 1.52, p = .003), such that an increase of 1 hour per week of time in nature was associated with an increase of β1 on the scale of each of these outcomes, and this association held until the estimated breakpoint (ψ), after which the effect levelled off to zero or close to zero (β1+β2) (see ). The breakpoints for these relationships were between 2.54 - 6.14 hours per week. Interestingly, we did not find significant associations for the measures of ill-being (i.e. negative affect and perceived stress).

Table 2. Breakpoints in hours of weekly duration of nature contact for emotional ill-being and well-being outcomes and emotion regulation strategies.

H2: emotion regulation is associated with emotional ill-being and well-being

In support of our hypothesis, we observed significant associations between reappraisal and lesser emotional ill-being and greater emotional well-being. We also observed the expected significant association between rumination and greater emotional ill-being and lesser emotional well-being. Counter to our hypothesis, we observed a significant association between distraction and greater emotional ill-being and lesser emotional well-being (except for positive affect). See for all results.

Table 3. Emotional ill-being and well-being outcomes in relation to emotion regulation strategies.

H3a: frequency of nature contact is associated with use of adaptive versus maladaptive strategies for regulating emotions

In support of our hypothesis, we observed a significant association between frequency of nature contact and more use of reappraisal. We also observed the expected significant association between frequency of nature contact and lesser use of rumination. Contrary to our hypothesis, we observed a significant association between frequency of nature contact and lesser use of distraction. See for all results.

H3b: duration of nature contact is associated with use of adaptive versus maladaptive strategies for regulating emotions

In support of our hypothesis, we observed that the association between weekly duration of nature contact and the adaptive emotion regulation strategy of reappraisal (β1 = 0.98, p = .045) was significant such that an increase of 1 hour per week of time in nature was associated with an increase of β1 on the scale of this outcome, and this association held until the estimated breakpoint (ψ), after which the effect levelled off to zero or close to zero (β1+β2) (see ). The breakpoint for this relationship was 2.73 hours per week. Interestingly, we did not find significant associations for distraction or rumination.

H4: emotion regulation mediates the link between frequency of nature contact and emotional ill-being and well-being

In support of our hypothesis, we found significant indirect effects from frequency of nature contact to emotional ill-being and well-being via more reappraisal and less rumination (see and ). We also found a significant indirect effect from frequency of nature contact to less use of distraction to lesser ill-being and greater well-being – however, this effect was in the opposite direction than hypothesised.

Table 4. Results from Bayesian structural equation model.

Discussion

Despite an enormous growth in research on the association of nature contact with emotional ill-being and well-being over the past decade, much remains unknown about pathways underlying these effects. Our results generally support our hypotheses that some emotion regulation strategies may be important pathways through which nature contact leads to emotional ill-being and well-being, though we cannot know if these associations reflect causal relationships as our data are cross-sectional. Below, we discuss some implications of our results as well as limitations and directions for future research. It is important to note that these ideas are motivated by our findings, but further empirical explorations are necessary to test these theories, given the cross-sectional nature of our data and resulting inability to assess causal relationships.

Nature contact and emotion regulation are associated with emotional ill-being and well-being

We observed significant associations of more frequent nature contact with lesser emotional ill-being and greater emotional well-being across all aspects that we assessed. For duration of nature contact, breakpoints were found for positive dimensions of well-being, including positive affect (3.27 hours per week), life satisfaction (6.14 hours per week), and purpose in life (2.54 hours per week). This supports the notion of a non-linear dose-response curve for these outcomes, with diminishing marginal gains in the levels of association after a certain threshold of duration of nature contact was reached. We did not find these associations with duration of nature contact and negative affect or perceived stress (though the trends were in the expected direction).

Our findings are also in line with the substantial literature on the associations of adaptive and maladaptive emotion regulation strategies with emotional ill-being and well-being (Gross, Citation2015; McRae & Gross, Citation2020). We observed a different direction of associations than we expected with distraction. This may be due to complexities regarding distinctions in distraction strategies and the repercussions for well-being. For example, distraction coupled with avoidance has been shown to be maladaptive, while distraction coupled with acceptance has been shown to be adaptive (Wolgast & Lundh, Citation2017). Relatedly, those who experience negative affect may be more likely to employ distraction as an emotion regulation strategy, and this may have resulted in the direction of the association we found here. Though we were most interested in adaptive forms of distraction, our choice of measure (a subscale of the PMERQ) in this context may not have provided sufficient distinction for us to adequately assess this.

Association of nature contact with emotion regulation

We found that frequency of nature contact was significantly associated with all the emotion regulation strategies we assessed – though in the opposite direction than we hypothesised for distraction. We also found significant nonlinear associations of duration of nature contact with reappraisal using segmented regression analyses that showed a breakpoint at 2.73 hours per week. This finding indicated that there was an association between duration of nature contact with greater frequency of reappraisal engagement up until 2.73 hours per week, but after this point higher levels of duration of nature were associated with only negligible increases in reappraisal. We did not find significant nonlinear associations of duration of nature contact with distraction or rumination.

Emotion regulation as a mediator between nature contact and emotional ill-being and well-being

We found significant indirect effects between frequency of nature contact; the regulation strategies of rumination and reappraisal; and emotional ill-being and well-being. We also found indirect effects for distraction, though they were in the opposite direction than hypothesised. Taken together, our findings support the notion that emotion regulation strategies are important to consider when assessing the relationship of nature contact with emotional ill-being and well-being (Bratman, Olvera-Alvarez, et al., Citation2021; Bratman, Young, et al., Citation2021; Johnsen & Rydstedt, Citation2013; Korpela et al., Citation2018; Korpela et al., Citation2020; Richardson, Citation2019; Tester-Jones et al., Citation2020), and that some of these strategies may be more relevant with respect to nature contact than others (e.g. we found a larger effect size for the association of frequency of nature contact with reappraisal vs. rumination and distraction).

Our cross-sectional mediation results support the notion that natural environments are associated with the greater use of adaptive regulation strategies (e.g. reappraisal) and lesser use of maladaptive ones (e.g. rumination) – and that these strategies may help explain associations of nature contact with lesser emotional ill-being and greater emotional well-being. The fact that distraction was associated with greater emotional ill-being and lesser emotional well-being means that the directions of our hypothesised associations were not supported, likely due to the heterogenous characteristics of the relationship of distraction with ill-being and well-being outcomes, depending on a number of individual-level and contextual factors. Future research should investigate this further. Below, we discuss specific ways in which the natural environment may play a role in influencing different emotion regulation strategies. We propose these ideas as potential areas for future research but emphasise that they will need to be validated with empirical findings specifically targeted to address the proposed relationships – including methods that provide insight on causal mechanisms.

Attentional deployment

While we did not find the expected direction of association between nature contact and distraction, we did find greater frequency of nature contact was associated with lesser rumination. This may be because the natural environment is associated with these aspects of attention allocation in different ways (Bratman, Olvera-Alvarez, et al., Citation2021).

With respect to distraction, some studies have demonstrated the potential of nature to encourage a form of adaptive distraction by providing a set of stimuli upon which to focus during short-term disengagement from aversive thoughts (e.g. shifting attention to bird song or a beautiful landscape) (Jiang, Citation2020). However, in our study we found distraction was related to greater ill-being and lesser well-being, suggesting the association of less distraction with nature contact may in fact be adaptive. Our use of the PMERQ subscale may have resulted in our employment of a measure that assessed maladaptive instead of adaptive distraction, and this may explain the differences in our findings from Jiang (Citation2020).

With respect to rumination, our results for frequency of nature contact were in line with previous research that found an association of nature contact with decreased rumination (Bratman, Daily, et al., Citation2015; Bratman, Young, et al., Citation2021; Lopes et al., Citation2020). The reasons why less rumination may happen in natural contexts remain relatively unknown. One possibility is that natural landscapes encourage a broadening of attentional scope or focus (e.g. global vs. local processing (Zadra & Clore, Citation2011)), which can be associated with reduced rumination and increased positive affect (Grol et al., Citation2015; Loewenstein & Lerner, Citation2003). Future research should investigate this possibility.

Reappraisal

Our results supported our hypothesis regarding a relationship of nature contact with emotional ill-being and well-being via reappraisal. As with other strategies of emotion regulation, context can be critical to the efficacy of reappraisal (McRae, Citation2016). Various environments may promote or detract from the capacity to think differently about situations. Specifically, nature experience might impact the ability to change the meaning of a stimulus, or to gain a new perspective on one’s goals in an adaptive way. For example, with respect to stress specifically, the determination of “what makes stress stressful” depends upon a variety of factors that are related to an individual’s specific relationship with social and physical environments (Bratman & Olvera-Alvarez, Citation2022; Sapolsky, Citation2015; Slavich, Citation2020). Natural environments may operate as a type of context that impacts the point at which an individual feels that a particular set of demands are greater than their cognitive or affective resources. What is stressful in an urban context may not be in a natural one, and vice versa. Our findings do not provide insight into these potential causal mechanisms, but future research should investigate these possibilities further.

Frequency and duration

Unlike the results for our frequency measure, our findings were not significant for duration of nature contact and negative affect, perceived stress, distraction, and rumination. Thus, given the association of distraction and rumination with negative affective outcomes, these segmented regression analyses appear to show a stronger relationship of average weekly duration of nature visits with positive emotional well-being and adaptive emotion regulation, and a non-significant relationship with negative emotional well-being and maladaptive emotion regulation. It is also interesting to note that associations of frequency of nature contact differed from duration, insofar as frequency was more consistently associated with significant associations across adaptive and maladaptive emotion regulation strategies, as well as ill-being and well-being measures. That there is a difference in findings between duration and frequency is broadly in line with prior work (e.g. Shanahan et al., Citation2016), though caution should be taken in interpreting null results, and future research should further investigate how and whether these different measures of nature contact lead to different findings with respect to these types of outcomes.

Limitations and future directions

Though our results largely supported our pre-registered hypotheses regarding the associations of nature contact with emotional ill-being and well-being via emotion regulation, there are important limitations to note in our approach that can inform future directions of research.

Cross-sectional data and lack of causal inference

First, the data we used were cross-sectional. This means that we were only able to establish associations and potential pathways based on cross-sectional mediation analyses, and we cannot infer causal relationships. It could be the case, for instance, that individuals who engage in reappraisal most frequently and/or effectively choose to spend more time in nature, and not that nature contact per se increases engagement in this choice of an adaptive emotion regulation strategy (Tester-Jones et al., Citation2020). We also lack insight into how participants were experiencing the environments, and whether instruction and/or education on specific practices to engage with nature may make the associations or effects even stronger (Pasanen et al., Citation2018).

To address limitations in our ability to assess causal relationships with this study, further research should investigate these pathways by gathering real-time data and employing controlled experiments and ecological momentary assessment methodologies. Emotion regulation often involves concurrent or sequential regulation strategies, as emerging work in polyregulation demonstrates (Ford et al., Citation2019). Nature experience may play a role at different points within this framework – identifying a regulation goal, selecting a strategy, and implementing a tactic. Future research should employ assessment approaches that focus on the real-time interplay between physical location, experience of affect and other aspects of well-being, and choice of regulation strategies (Heiy & Cheavens, Citation2014). This research may also provide insight into whether nature contact has immediate, short-term impacts on affect through emotion regulation, and if these culminate to produce longer-term emotional ill-being and well-being outcomes (Korpela et al., Citation2020).

Future work should also aim to further understand how flexibility in choices of regulation strategies are associated with various environmental contexts (Pruessner et al., Citation2020). Insight into this, along with temporal dynamics, may reveal more about the underlying explanatory factors for the nonlinear effects we observed, in which different breakpoints for outcomes were reached at a certain amount of nature contact per week – after which beneficial associations were no longer observed. For example, nonlinear relationships may be due to the typical duration of different tasks (e.g. dog walking), or related to the ways in which natural environments may cue different ways of thinking. At relatively high levels of duration, beneficial outcomes may taper off when this flexibility and shift in thought reaches a “saturation point”.

Constraints on generality

Our study did not investigate personality traits as potential moderators of the pathway from nature contact to emotional ill-being and well-being. For example, past research has shown that individuals with higher levels of neuroticism experienced greater restoration in natural environments via emotion regulation (Johnsen, Citation2013). Other emerging work points to the sensitivity of highly anxious individuals to social stress and negative affect, and the increased benefit that certain environmental factors may provide for the regulation and reduction of these aspects of well-being through the provision of additional affordances for emotion regulation (Holz, Tost, & Meyer-Lindenberg, Citation2019; Reichert, Braun, Lautenbach, Zipf, Ebner-Priemer et al., Citation2020; Tost, Reichert, Braun, Reinhard, Peters et al., Citation2019). As another example, with respect to attention allocation, individuals with higher working memory capacity (Kobayashi et al., Citation2021) or low levels of trait anxiety (Cho et al., Citation2019) tend to engage in distraction more effectively and adaptively. The relevance of these individual-level personality traits is an important area of investigation for future research in nature and health. We did include the covariates of age, gender, education, and perceived socioeconomic status, but there may be other potentially relevant covariates that should be included in future investigations as well.

Additionally, our study was not powered to empirically examine how different types of nature and nature interactions impact different people in a variety of ways. This represents a crucial set of questions for the field of environmental psychology (Bratman & Olvera-Alvarez, Citation2022) – including investigations into how the effects from forests, for example, may differ from meadows, oceans, and other natural environments (Li et al., Citation2023); whether the natural area is situated in a designed and controlled space (e.g. urban park) or larger, wild area (e.g. National Park); or how different living locations (e.g. urban vs. rural) of individuals may play a role in modifying effects (Wheeler et al., Citation2015). Also important to note in future work is how a range of types of interaction patterns with nature (Kahn et al., Citation2010) may be relevant for emotion regulation and emotional ill-being and well-being, including considerations of whether the nature contact is incidental or intentional, or the nature visit is due to work obligations or recreation. These aspects were not captured in our operationalisation of nature contact in this paper.

We requested a nationally representative sample from Prolific, and did not include race and ethnicity as covariates in our analyses, as we did not have strong a priori hypotheses about the ways in which these factors might moderate associations in this case. We lacked adequate information on the social dimensions and barriers present within the natural areas visited by our participants and we were not sufficiently powered to examine this set of related and important questions. Future work on nature and emotion regulation should investigate the potential for discrimination and exclusionary policies in natural environments to moderate the associations of these spaces with emotion regulation and emotional ill-being and well-being outcomes for BIPOC visitors and communities (Hoover & Lim, Citation2021; Roberts, Citation2022; Roberts et al., Citation2023).

Our self-report assessment of nature contact was intentionally designed to capture a range of nature types and interactions as our hypotheses focused on nature contact in broad terms. This measure was not developed to distinguish between categories of nature type and interaction. As with most self-report measures, our operationalisation of nature contact is also limited by potential for incorrect or biased recall as well. It is also important to note that we conducted this survey in January 2022 – a time during which the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic were still a dominant aspect of many individuals’ daily experiences, and we therefore note this potential limitation on generalisability of our findings across time as well.

Conclusion

Results from the present study are consistent with the idea that emotion regulation may mediate the link between nature contact and emotional ill-being and well-being, though we were not able to assess causal pathways with these cross-sectional data. These pathways should be examined with designs that allow for investigations of cause and effect, and a deeper understanding of the ways in which environments may influence temporal dynamics between emotion regulation and emotional ill-being and well-being. Future work can continue to broaden the dimensions of well-being that are considered in this context as well, including self-acceptance and personal growth (Ryff, Citation1989). These and other considerations will add to the understanding of the ways in which nature contact may have a health-promoting impact through two separate pathways: 1) an increase in well-being through a “promotion of positive”, and 2) a decrease in negative affect through a “reduction of harm” (Bratman et al., Citation2019; Markevych et al., Citation2017; Marselle et al., Citation2021; White et al., Citation2020). Not only will this provide context for the theoretical understanding of causal mechanisms, but it will also help to determine the best ways to leverage nature contact to decrease ill-being and increase well-being for people around the world.

SM Nature - Emotion Regulation 01192024.docx

Download MS Word (122.4 KB)Acknowledgements

Gregory N. Bratman appreciates support from the Doug Walker Endowed Professorship, Craig McKibben and Sarah Merner, and John Miller. Gregory N. Bratman and Hector A. Olvera-Alvarez appreciate support from the JPB Environmental Health Fellowship.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aldao, A., & Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2010). Specificity of cognitive emotion regulation strategies: A transdiagnostic examination. Behaviour Re- search and Therapy, 48, 974–983. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2010.06.002 .

- Annerstedt, M., Jonsson, P., Wallergard, M., Johansson, G., Karlson, B., Grahn, P., Hansen, A. M., & Wahrborg, P. (2013). Inducing physiological stress recovery with sounds of nature in a virtual reality forest – results from a pilot study. Physiology & Behavior, 118, 240–250. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2013.05.023

- Aspinall, P., Mavros, P., Coyne, R., & Roe, J. J. (2015). The urban brain: Analysing outdoor physical activity with mobile EEG. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 49(4), 272–276. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2012-091877

- Banay, R. F., James, P., Hart, J. E., Kubzansky, L. D., Spiegelman, D., Okereke, O. I., Spengler, J. D., & Laden, F. (2019). Greenness and depression incidence among older women. Environmental Health Perspectives, 127(2), 027001. https://doi.org/10.1289/EHP1229

- Barnes, M. R., Donahue, M. L., Keeler, B. L., Shorb, C. M., Mohtadi, T. Z., & Shelby, L. J. (2019). Characterizing nature and participant experience in studies of nature exposure for positive mental health: An integrative review. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02617

- Basu, A., Duvall, J., & Kaplan, R. (2019). Attention restoration theory: Exploring the role of soft fascination and mental bandwidth. Environment and Behavior, 51(9–10), 1055–1081. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916518774400

- Becker, D. A., Browning, M. H., Kuo, M., & Van Den Eeden, S. K. (2019). Is green land cover associated with less health care spending? Promising findings from county-level Medicare spending in the continental United States. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 41, 39–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2019.02.012

- Berman, M., Jonides, J., & Kaplan, S. (2008). The cognitive benifits of interacting with nature. Psychological Science, 19(12), 1207–1212. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02225.x

- Berman, M. G., Kross, E., Krpan, K. M., Askren, M. K., Burson, A., Deldin, P. J., Kaplan, S., Sherdell, L., Gotlib, I. H., & Jonides, J. (2012). Interacting with nature improves cognition and affect for individuals with depression. Journal of Affective Disorders, 140(3), 300–305. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2012.03.012

- Besser, L. M., Hirsch, J., Galvin, J. E., Renne, J., Park, J., Evenson, K. R., Kaufman, J. D., & Fitzpatrick, A. L. (2020). Associations between neighborhood park space and cognition in older adults vary by US location: The multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Health & Place, 66, Article 102459. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2020.102459

- Bezold, C. P., Banay, R. F., Coull, B. A., Hart, J. E., James, P., Kubzansky, L. D., Missmer, S. A., & Laden, F. (2018). The relationship between surrounding greenness in childhood and adolescence and depressive symptoms in adolescence and early adulthood. Annals of Epidemiology, 28(4), 213–219. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annepidem.2018.01.009

- Bratman, G. N., Anderson, C. B., Berman, M. G., Cochran, B., de Vries, S., Flanders, J., Folke, C., Frumkin, H., Gross, J. J., Hartig, T., Kahn, P. H., Kuo, M., Lawler, J. J., Levin, P. S., Lindahl, T., Meyer-Lindenberg, A., Mitchell, R., Ouyang, Z., Roe, J., … Daily, G. C. (2019). Nature and mental health: An ecosystem service perspective. Science Advances, 5(7), eaax0903. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aax0903

- Bratman, G. N., Daily, G. C., Levy, B. J., & Gross, J. J. (2015). The benefits of nature experience: Improved affect and cognition. Landscape and Urban Planning, 138, 41–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2015.02.005

- Bratman, G. N., Hamilton, J. P., & Daily, G. C. (2012). The impacts of nature experience on human cognitive function and mental health. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1249(1), 118–136. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06400.x

- Bratman, G. N., Hamilton, J. P., Hahn, K. S., Daily, G. C., & Gross, J. J. (2015). Nature experience reduces rumination and subgenual prefrontal cortex activation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 112(28), 8567–8572. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1510459112

- Bratman, G. N., & Olvera-Alvarez, H. A. (2022). Nature and health: Perspectives and pathways. Ecopsychology, 14(3), 133–136. https://doi.org/10.1089/eco.2022.29007.editorial

- Bratman, G. N., Olvera-Alvarez, H. A., & Gross, J. J. (2021). The affective benefits of nature exposure. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 15(8), e12630. https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12630

- Bratman, G. N., Young, G., Mehta, A., Lee Babineaux, I., Daily, G. C., & Gross, J. J. (2021). Affective benefits of nature contact: The role of rumination. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, Article 643866. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.643866

- Cho, S., White, K. H., Yang, Y., & Soto, J. A. (2019). The role of trait anxiety in the selection of emotion regulation strategies and subsequent effectiveness. Personality and Individual Differences, 147, 326–331. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2019.04.035

- Cohen, S., Kamarck, T., & Mermelstein, R. (1983). A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 24(4), 385. https://doi.org/10.2307/2136404

- Collado, S., Staats, H., Corraliza, J. A., & Hartig, T. (2017). Restorative environments and health. In G. Fleury-Bahi, E. Pol, & O. Navarro (Eds.), Handbook of environmental psychology and quality of life research (pp. 127–148). Springer.

- de Vries, S., Verheij, R. A., Groenewegen, P. P., & Spreeuwenberg, P. (2003). Natural environments – healthy environments? An exploratory analysis of the relationship between greenspace and health. Environment and Planning A, 35(10), 1717–1731. https://doi.org/10.1068/a35111

- Dratva, J., Zemp, E., Felber Dietrich, D., Bridevaux, P. O., Rochat, T., Schindler, C., & Gerbase, M. W. (2010). Impact of road traffic noise annoyance on health-related quality of life: Results from a population-based study. Quality of Life Research, 19(1), 37–46. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-009-9571-2

- Dzhambov, A. M., Browning, M. H. E. M., Markevych, I., Hartig, T., & Lercher, P. (2020). Analytical approaches to testing pathways linking greenspace to health: A scoping review of the empirical literature. Environmental Research, 186, Article 109613. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2020.109613

- Fink, A., Weiss, E. M., Schwarzl, U., Weber, H., de Assuncao, V. L., Rominger, C., Schulter, G., Lackner, H. K., & Papousek, I. (2017). Creative ways to well-being: Reappraisal inventiveness in the context of anger-evoking situations. Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience, 17(1), 94–105. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13415-016-0465-9

- Ford, B. Q., Gross, J. J., & Gruber, J. (2019). Broadening our field of view: The role of emotion polyregulation. Emotion Review, 11(3), 197–208. https://doi.org/10.1177/1754073919850314

- Fredrickson, B. L. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. American Psychologist, 56(3), 218. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.56.3.218

- Frumkin, H., Bratman, G. N., Breslow, S. J., Cochran, B., Kahn, P. H., Lawler, J. J., Levin, P. S., Tandon, P. S., Varanasi, U., Wolf, K. L., & Wood, S. A. (2017). Nature contact and human health: A research agenda. Environmental Health Perspectives, 125(7), 7. https://doi.org/10.1289/EHP1663

- Gascon, M., Zijlema, W., Vert, C., White, M. P., & Nieuwenhuijsen, M. J. (2017). Outdoor blue spaces, human health and well-being: A systematic review of quantitative studies. International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health, 220(8), 1207–1221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijheh.2017.08.004

- Genet, J. J., & Siemer, M. (2012). Rumination moderates the effects of daily events on negative mood: results from a diary study. Emotion, 12(6), 1329.

- Giatti, L., Camelo, L. D. V., Rodrigues, J. F. D. C., & Barreto, S. M. (2012). Reliability of the MacArthur Scale of Subjective Social Status – Brazilian longitudinal study of adult health (ELSA-Brasil). BMC Public Health, 12(1), 1096. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-12-1096

- Gibson, J. J. (1977). The theory of affordances. In R. Shaw & J. Bransford (Eds.), Perceiving, acting, and knowing: Toward an ecological psychology (pp. 67–82). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Grol, M., Hertel, P. T., Koster, E. H. W., & De Raedt, R. (2015). The effects of rumination induction on attentional breadth for self-related information. Clinical Psychological Science, 3(4), 607–618. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167702614566814

- Gross, J. J. (1998). The emerging field of emotion regulation: An integrative review. Review of General Psychology, 2(3), 271–299. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.2.3.271

- Gross, J. J. (2015). Emotion regulation: Current status and future prospects. Psychological Inquiry, 26(1), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/1047840X.2014.940781

- Gross, J. J., & John, O. P. (2003). Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: Implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(2), 348–362. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.85.2.348

- Gross, J. J., Uusberg, H., & Uusberg, A. (2019). Mental illness and well-being: An affect regulation perspective. World Psychiatry, 18(2), 130–139. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20618

- Hartig, T. (2021). Restoration in nature: Beyond the conventional narrative. In A. R. Schutte, J. Torquati, & J. R. Stevens (Eds.), Nature and psychology: Biological, cognitive, developmental, and social pathways to well-being (Proceedings of the 67th Annual Nebraska Symposium on Motivation). Springer Nature.

- Hartig, T., Böök, A., Garvill, J., Olsson, T., & Gärling, T. (1996). Environmental influences on psychological restoration. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 37(4), 378–393. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9450.1996.tb00670.x

- Hartig, T., Evans, G. W., Jamner, L. D., Davis, D. S., & Gärling, T. (2003). Tracking restoration in natural and urban field settings. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 23(2), 109–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-4944(02)00109-3

- Hartig, T., Korpela, K., Evans, G. W., & Gärling, T. (1997). A measure of restorative quality in environments. Scandinavian Housing and Planning Research, 14(4), 175–194. https://doi.org/10.1080/02815739708730435

- Hartig, T., Mitchell, R., de Vries, S., & Frumkin, H. (2014). Nature and health. Annual Review of Public Health, 35(1), 207–228. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032013-182443

- Heaney, A. K., Carrion, D., Burkart, K., Lesk, C., & Jack, D. (2019). Climate change and physical activity: Estimated impacts of ambient temperatures on bikeshare usage in New York City. Environmental Health Perspectives, 127(3), 37002. https://doi.org/10.1289/EHP4039

- Heiy, J. E., & Cheavens, J. S. (2014). Back to basics: A naturalistic assessment of the experience and regulation of emotion. Emotion, 14(5), 878–891. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037231

- Helion, C., Krueger, S. M., & Ochsner, K. N. (2019). Emotion regulation across the life span. Handbook of Clinical Neurology, 163, 257–280. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-804281-6.00014-8

- Herzog, T. R., Black, A. M., Fountaine, K. A., & Knotts, D. J. (1997). Reflection and attentional recovery as distinctive benefits of restorative environments. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 17(2), 165–170. https://doi.org/10.1006/jevp.1997.0051

- Holland, I., DeVille, N. V., Browning, M. H., Buehler, R. M., Hart, J. E., Hipp, J. A., Mitchell, R., Rakow, D. A., Schiff, J. E., & White, M. P. (2021). Measuring nature contact: A narrative review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(8), 4092. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18084092

- Holz, N. E., Tost, H., & Meyer-Lindenberg, A. (2019). Resilience and the brain: a key role for regulatory circuits linked to social stress and support. Molecular Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-019-0551-9.

- Hoover, F.-A., & Lim, T. C. (2021). Examining privilege and power in US urban parks and open space during the double crises of antiblack racism and COVID-19. Socio-Ecological Practice Research, 3(1), 55–70. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42532-020-00070-3

- Huppert, F. A. (2009). Psychological well-being: Evidence regarding its causes and consequences. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being, 1(2), 137–164. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1758-0854.2009.01008.x

- Jiang, S. (2020). Positive distractions and play in the public spaces of pediatric healthcare environments: A literature review. HERD: Health Environments Research & Design Journal, 13(3), 171–197. https://doi.org/10.1177/1937586720901707

- John, O. P., & Gross, J. J. (2004). Healthy and unhealthy emotion regulation: Personality processes, individual differences, and life span development. Journal of Personality, 72(6), 1301–1334. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2004.00298.x

- Johnsen, S. Å. K. (2013). Exploring the use of nature for emotion regulation: Associations with personality, perceived stress, and restorative outcomes. Nordic Psychology, 65(4), 306–321. https://doi.org/10.1080/19012276.2013.851445

- Johnsen, S. Å. K., & Rydstedt, L. W. (2013). Active use of the natural environment for emotion regulation. Europe's Journal of Psychology, 9(4), 798–819. https://doi.org/10.5964/ejop.v9i4.633

- Joormann, J., & Gotlib, I. H. (2010). Emotion regulation in depression: Relation to cognitive inhibition. Cognition and Emotion, 24(2), 281–298.

- Joye, Y., & van den Berg, A. E. (2018). Restorative environments. In L. Steg & J. I. M. de Groot (Eds.), Environmental psychology: An introduction (pp. 65–75). Wiley.

- Kahn, P. H., Jr., Ruckert, J. H., Severson, R. L., Reichert, A. L., & Fowler, E. (2010). A nature language: An agenda to catalog, save, and recover patterns of human–nature interaction. Ecopsychology, 2(2), 59–66. https://doi.org/10.1089/eco.2009.0047

- Kaplan, R., & Kaplan, S. (1989). The experience of nature: A psychological perspective. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005053-199111000-00012

- Kaplan, S. (1995). The restorative benefits of nature: Toward an integrative framework. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 15(3), 169–182. https://doi.org/10.1016/0272-4944(95)90001-2

- Kaplan, S., Bardwell, L. V., & Slakter, D. B. (1993). The museum as a restorative environment. Environment and Behavior, 25(6), 725–742. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916593256004

- Kardan, O., Demiralp, E., Hout, M. C., Hunter, M. R., Karimi, H., Hanayik, T., Yourganov, G., Jonides, J., & Berman, M. G. (2015). Is the preference of natural versus man-made scenes driven by bottom-up processing of the visual features of nature? Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00471

- Kobayashi, R., Miyatani, M., & Nakao, T. (2021). High working memory capacity facilitates distraction as an emotion regulation strategy. Current Psychology, 40(3), 1159–1167. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-018-0041-2

- Koole, S. L., Webb, T. L., & Sheeran, P. L. (2015). Implicit emotion regulation: Feeling better without knowing why. Current Opinion in Psychology, 3, 6–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2014.12.027

- Korpela, K., & Hartig, T. (1996). Restorative qualities of favorite places. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 16(3), 221–233. https://doi.org/10.1006/jevp.1996.0018

- Korpela, K., & Kinnunen, U. (2011). How is leisure time interacting with nature related to the need for recovery from work demands? Testing multiple mediators. Leisure Sciences, 33(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/01490400.2011.533103

- Korpela, K. M. (1989). Place-identity as a product of environmental self-regulation. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 9(3), 241–256. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-4944(89)80038-6

- Korpela, K. M. (1992). Adolescents’ favourite places and environmental self-regulation. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 12(3), 249–258. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-4944(05)80139-2

- Korpela, K. M. (2003). Negative mood and adult place preference. Environment and Behavior, 35(3), 331–346. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916503251442

- Korpela, K. M., Hartig, T., Kaiser, F. G., & Fuhrer, U. (2001). Restorative experience and self-regulation in favorite places. Environment and Behavior, 33(4), 572–589. https://doi.org/10.1177/00139160121973133

- Korpela, K. M., Korhonen, M., Nummi, T., Martos, T., & Sallay, V. (2020). Environmental self-regulation in favourite places of Finnish and Hungarian adults. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 67, Article 101384. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2019.101384

- Korpela, K. M., Pasanen, T., Repo, V., Hartig, T., Staats, H., Mason, M., Alves, S., Fornara, F., Marks, T., Saini, S., Scopelliti, M., Soares, A. L., Stigsdotter, U. K., & Thompson, C. W. (2018). Environmental strategies of affect regulation and their associations with subjective well-being. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00562

- Korpela, K. M., & Ylen, M. (2007). Perceived health is associated with visiting natural favourite places in the vicinity. Health & Place, 13(1), 138–151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2005.11.002

- Korpela, K. M., Ylén, M., Tyrväinen, L., & Silvennoinen, H. (2010). Favorite green, waterside and urban environments, restorative experiences and perceived health in Finland. Health Promotion International, 25(2), 200–209. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/daq007

- Lazarus, R. S. (1984). On the primacy of cognition. American Psychologist, 39(2), 124–129. https://doi.org/10.1037//0003-066x.39.2.124

- Li, H., Browning, M. H., Rigolon, A., Larson, L. R., Taff, D., Labib, S. M., Benfield, J., Yuan, S., McAnirlin, O., Hatami, N., & Kahn, P. H., Jr. (2023). Beyond “bluespace” and “greenspace”: A narrative review of possible health benefits from exposure to other natural landscapes. Science of the Total Environment, 856, Article 159292. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.159292

- Li, J., Zhang, Z., Si, S., & Xue, F. (2021). Leisure-time physical activity and cardiovascular disease risk among hypertensive patients: A longitudinal cohort study. Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine, 8, Article 644573. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcvm.2021.644573

- Littman, A. J., Bratman, G. N., Lehavot, K., Engel, C. C., Fortney, J. C., Peterson, A., Jones, A., Klassen, C., Brandon, J., & Frumkin, H. (2021). Nature versus urban hiking for veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder: A pilot randomised trial conducted in the Pacific Northwest USA. BMJ Open, 11(9), e051885. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-051885

- Loewenstein, G., & Lerner, J. S. (2003). The role of affect in decision making. In H. Goldsmith, R. J. Davidson, & K. Scherer (Eds.), Handbook of affective science (pp. 619–642). Oxford University Press.

- Lopes, S., Lima, M., & Silva, K. (2020). Nature can get it out of your mind: The rumination reducing effects of contact with nature and the mediating role of awe and mood. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 71, Article 101489. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2020.101489

- Maas, J., Verheij, R. A., Groenewegen, P. P., De Vries, S., & Spreeuwenberg, P. (2006). Green space, urbanity, and health: How strong is the relation? Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 60(7), 587–592. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2005.043125

- Margolis, S., Schwitzgebel, E., Ozer, D. J., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2019). A new measure of life satisfaction: The Riverside Life Satisfaction Scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 101(6), 621–630. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2018.1464457

- Markevych, I., Schoierer, J., Hartig, T., Chudnovsky, A., Hystad, P., Dzhambov, A. M., de Vries, S., Triguero-Mas, M., Brauer, M., Nieuwenhuijsen, M. J., Lupp, G., Richardson, E. A., Astell-Burt, T., Dimitrova, D., Feng, X., Sadeh, M., Standl, M., Heinrich, J., & Fuertes, E. (2017). Exploring pathways linking greenspace to health: Theoretical and methodological guidance. Environmental Research, 158, 301–317. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2017.06.028

- Marselle, M. R., Hartig, T., Cox, D. T. C., de Bell, S., Knapp, S., Lindley, S., Triguero-Mas, M., Böhning-Gaese, K., Braubach, M., Cook, P. A., de Vries, S., Heintz-Buschart, A., Hofmann, M., Irvine, K. N., Kabisch, N., Kolek, F., Kraemer, R., Markevych, I., Martens, D., … Bonn, A. (2021). Pathways linking biodiversity to human health: A conceptual framework. Environment International, 150, Article 106420. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2021.106420