ABSTRACT

Children’s earliest acquired words are often learned through sensorimotor experience, but it is less clear how children learn the meaning of concepts whose referents are less associated with sensorimotor experience. The Affective Embodiment Account postulates that children use emotional experience to learn more abstract word meanings. There is mixed evidence for this account; analyses using mega-study datasets suggest that negative or positively valenced abstract words are learned earlier than emotionally neutral abstract words, yet the relationship between sensorimotor experience and valence is inconsistent across different methods of operationalising sensorimotor experience. In the present study, we tested the Affective Embodiment Account specifically in the context of verb acquisition. We tested two semantic dimensions of sensorimotor experience: concreteness and embodiment ratings. Our analyses showed that more positive and negative abstract verbs are acquired at an earlier age than neutral abstract verbs, consistent with the Affective Embodiment Account. When sensorimotor experience is operationalised as embodiment, high embodiment verbs are acquired at an earlier age than low embodiment verbs, and there is further benefit for high embodiment and positively valenced verbs. The findings further clarify the role of Affective Embodiment as a mechanism of language acquisition.

Multiple representation theories of word meaning propose that we understand words through our perceptual, physical, social, emotional, and linguistic experiences, which are unconsciously simulated when we process language (Barsalou, Citation2008). Such theories also predict that embodied experience will be important for language acquisition (Pexman, Citation2019). Indeed, research shows that children tend to acquire words earlier if they are more concrete, referring to tangible entities that they can readily perceive or interact with physically (Gentner, Citation2006; Pexman, Citation2019). However, embodied experience seems less relevant to the development of abstract word meaning (e.g. hope), as abstract words do not have clear perceptual referents or associated physical experience. One proposal is that abstract word meaning relies more on emotional, interoceptive, linguistic, and social experience (Borghi et al., Citation2017). Extending that proposal, the Affective Embodiment Account (AEA) suggests that the acquisition and processing of abstract words might involve emotional information to a greater degree than for concrete words (Borghi et al., Citation2017; Vigliocco et al., Citation2014). The purpose of the present paper was to test theoretical claims of the AEA about acquisition of verb meaning.

The AEA is based on the observation that abstract concepts tend to be more emotionally valenced than concrete concepts (Vigliocco et al., Citation2014), and thus the meanings of abstract words may be embodied via emotional experience. In terms of language development, the AEA proposes that emotional experience contributes to acquisition by providing a bootstrapping mechanism for abstract language. Early associations between emotional experience and abstract words build a foundation for the continued development of abstract language by helping children understand that language applies not only to “word-to-world mappings” wherein words refer to perceivable entities in their environment (Gleitman et al., Citation2005, p. 25), but also to entities not experienced from the external environment through the senses. Consistent with this proposal, large-scale analyses of word age of acquisition data have found an interaction between word concreteness and valence, wherein valenced abstract words (positive and negative) are acquired earlier than abstract words of neutral valence (Ponari et al., Citation2018; Reggin et al., Citation2021). Behavioural evidence from a developmental perspective is limited, however, children’s lexical processing and recognition memory for abstract words appear to be enhanced when words are more valenced, and this is evident in children as young as 6-years-old (Kim et al., Citation2020; Lund et al., Citation2019; Ponari et al., Citation2018). This evidence further suggests that emotional information may be a particularly important dimension of abstract word meaning.

While the preceding studies provide some support for the AEA and its proposal regarding abstract language development, there is also evidence that constrains the generalizability of this account. Winter (Citation2023) tested the relationship between valence and sensorimotor experience in a large set of words (including a variety of syntactic classes). Sensorimotor information was operationalised as sensory experience ratings (which quantify the degree to which a word evokes sensory experience, rather than how sensory experience is used to understand a word’s meaning) and sensorimotor strength associations (rating the degree to which a word is experienced through six different senses, quantifying both the sum rating across all senses and the rating for the sense most strongly related to the concept). They found that the relationship reverses direction when tested with these measures and that words with more sensorimotor information are more likely to be positively or negatively valenced.

Purpose of the present study

The findings from Winter (Citation2023) suggest limitations to the AEA, but their study did not test the core proposal that emotional information provides a bootstrapping mechanism for the acquisition of abstract language. Thus, the purpose of the present study was to investigate the generalizability of the AEA proposal, first by testing whether we observe an interaction between word concreteness and valence in relation to age of acquisition for English verbs. We selected verbs as our stimuli for several reasons. First, verbs tend to be more abstract, with lower concreteness and imageability ratings compared to nouns, and more difficult for children to acquire (Gentner, Citation2006), thus providing an opportunity to conduct a highly sensitive test of which dimensions of word meaning benefit the acquisition of abstract words. Furthermore, a reverse effect of valence on abstract word processing was observed in a study that specifically examined verb processing in adults (Palazova et al., Citation2013), suggesting that the relationship between concreteness and valence may differ for this class of words in particular.

Second, the use of verbs allows us to further test whether the relationship of emotional valence to acquisition varies as a function of how sensorimotor information is operationalised, by investigating interactions involving both concreteness ratings and, separately, embodiment ratings. Embodiment ratings measure the degree to which a verb’s meaning involves the human body (Sidhu et al., Citation2014) and can include internally focused, introspective states of the human body, whereas the definition of concreteness is more externally focused on concepts experienced through the senses. The distinction between internal vs external focus has been identified in a latent factor structure of semantic space, distinguishing information arising from the self (involving semantic dimensions such as emotion and self-generated motion) vs information arising from the environment (involving semantic dimensions related to sensory experience; Troche et al., Citation2017). Consistent with this internal vs external framework, embodiment may also index bodily states related to emotions, which would not be captured in concreteness ratings. Therefore, emotion may not be related to the acquisition of low embodiment verbs, the meanings of which do not relate to the human body through either introspection or action.

Method

For our analyses we used the semantic dimensions of concreteness (the degree to which a verb’s meaning can be experienced through the senses, range: 1–5; Brysbaert et al., Citation2014), relative embodiment (the degree to which a verb’s meaning involves the human body, range 1–7; Sidhu et al., Citation2014), imageability (the degree to which a verb’s meaning can easily generate a mental image, range 1–7; Cortese & Fugett, Citation2004), valence (the degree to which a verb’s meaning is unhappy or happy, range: 1–9 with 5 representing neutral valence on this bi-polar scale; Warriner et al., Citation2013), and valence extremity (the degree to which a verb’s meaning is emotional, taking the absolute distance from the midpoint of a bi-polar scale; Warriner et al., Citation2013). These measures were derived from semantic dimension ratings for 2,938 verbs (Muraki & Pexman, Citation2024), collected using the definitions described above. For the present study we only included verbs that had at least 20 participant ratings on each of the predictors in the Muraki and Pexman norms (M = 26, range: 21–49 ratings) and had ratings available for the dependent variable and the control variables (n = 2159). The dependent variable in our regression analyses was age of acquisition (Kuperman et al., Citation2012), quantified using ratings from adult English speakers that capture the age at which they believe they acquired a word. The control variables were two lexical dimensions that are highly related to word age of acquisition: word length (in letters) and word frequency (log subtitle frequency Brysbaert & New, Citation2009).

We first conducted a network analysis to provide insight into the structure of the lexical semantic space of our verb data. In this analysis lexical semantic variables are represented as nodes within the network and the statistical relationships amongst the variables are represented by the edges (Isvoranu & Epskamp, Citation2023). We entered valence extremity into this analysis, to interpret the linear relationship with the other variables (otherwise a polynomial term would be required to account for the bi-polar valence rating scale). We estimated a partial correlation network from a Spearman correlation matrix using a stepwise graphical LASSO nonregularized algorithm for network estimation combined with BIC model selection. This method of network estimation is ideal when a dataset has a large sample size and few nodes, resulting in a network with reduced false edges and high sensitivity to identify strong edges (Isvoranu & Epskamp, Citation2023). We estimated confidence intervals for the edge weights using nonparametric bootstrapping with 2,500 samples (with replacement) to assess the stability of the edge weights in the network.

We next conducted item-level regression analyses to investigate the relationships between verb concreteness or embodiment and valence to predict word age of acquisition. We omitted verb imageability from the regression models as it is highly correlated with concreteness. We chose to use concreteness instead of imageability to facilitate comparison with previous studies that operationalised sensorimotor experience using concreteness ratings. All predictors were mean centred before being entered into the regression models. Interactions between concreteness and valence and embodiment and valence tested both linear and quadratic relationships between the sensorimotor dimension and valence. Analyses were run in R (R Core Team, Citation2022) and all packages used for the analyses are provided in the supplemental materials. The data and analysis scripts are available at https://osf.io/6mu2 h/.

Results

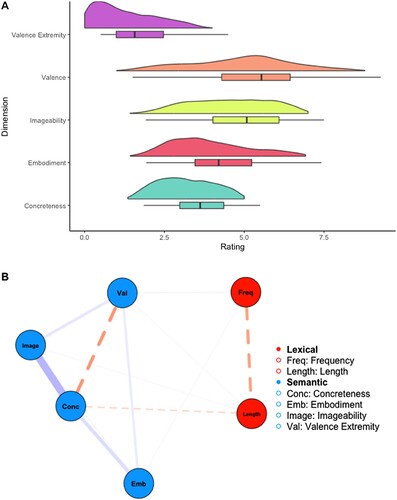

The medians, interquartile ranges, and distributions of the semantic variables are presented in a. Means, standard deviations, and correlations between the variables are presented in Table S1 of the supplemental materials. The verbs were first submitted to a network analysis, the results of which are presented in . The network was comprised of 6 nodes and 12 non-zero edges, with a mean edge weight of 0.091. Non-zero edge weights ranged from 0.073 (frequency – embodiment) to 0.811 (concreteness – imageability). The confidence intervals across the bootstrapped samples for the pairwise partial correlations between semantic variables were generally narrow, as were the confidence intervals for the pairwise partial correlations between lexical variables, indicating stable edge weight estimates. This is consistent with the clustering of relationships with the selected network. Semantic variables were strongly related to one another, with the strongest positive relationship occurring between concreteness and imageability. Embodiment showed a moderate positive relationship with valence extremity, indicating that more embodied verbs were also more valenced. This contrasted with the negative relationship between concreteness and valence extremity, indicating that more concrete verbs were less valenced.

Figure 1. Lexical Semantic Variable Medians, Distributions, and Relationships (n = 2,159).

Note. A. Density plot and boxplot of semantic variables. B. Nonregularized partial-correlation network. Lexical variables are presented in red and semantic variables are presented in blue. Solid purple edges represent positive partial-correlations and dashed orange edges represent negative partial-correlations. The width of the edge line represents the strength of the partial correlation.

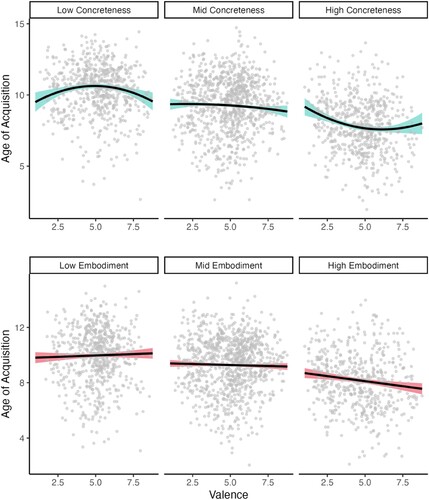

We conducted a regression analysis to test whether the interaction between verb concreteness and valence accounted for variance in age of acquisition, above and beyond the control variables. We hypothesised that abstract verbs would be acquired earlier if they were positively or negatively valenced. This model (presented in ) accounted for 47.6% of the variance in age of acquisition. We observed a significant interaction between verb concreteness and the quadratic valence term (b = 6.92, t = 3.74, p < .001), indicating that for abstract verbs, more valenced items (either positive or negative, e.g. approve, disappoint) were acquired earlier than neutral items. However, for verbs at the midpoint or high end of the concreteness scale, this relationship was not present, or was reversed, showing that for very concrete verbs more valenced items (either positive or negative, e.g. caress, mutilate) tended to be acquired later than neutral items ().

Figure 2. Interactions Between Concreteness and Valence and, Separately, Embodiment and Valence, to Predict AoA.

Note. Relationships between valence and age of acquisition for low, mid, and high values of concreteness and, separately, embodiment (Low, mid, and high correspond to the 10th, 50th, and 90th percentile respectively). Blue and red regions represent the 95% confidence band.

Table 1. Regression Models Predicting AoA (n = 2,159).

We then conducted a regression analysis to test whether the interaction between verb embodiment and valence accounted for variance in age of acquisition, above and beyond the control variables. We hypothesised that, in contrast to concreteness, less embodied verbs would not be acquired earlier if they were positively or negatively valenced. This model (presented in ) accounted for 40.8% of the variance in age of acquisition. We observed a significant interaction between verb embodiment and the linear valence term (b = −4.52, t = −2.21, p = .027), indicating that more positively valenced embodied verbs (e.g. live) were acquired earlier than negatively valenced (e.g. mishear) or neutral (e.g. metabolize) embodied verbs. However, for verbs with low or midscale embodiment ratings this relationship with valence was not present ().

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to investigate the generalizability of the AEA proposal by extending the previous research in two ways. We first examined if the AEA proposal can account for verb acquisition, by testing whether sensorimotor and emotional semantic dimensions were related to acquisition. If the AEA proposal generalises to verb acquisition, we expected that verbs with low concreteness ratings (i.e. the degree to which a word’s meaning is related to the senses) would be acquired earlier if they were more valenced. Second, we tested the prediction that if sensorimotor information was operationalised by a measure of relative embodiment (i.e. the degree to which the word’s meaning involves the human body), valence would provide no additional benefit to acquiring low embodiment verbs, as these items would lack introspective information related to emotional meaning.

We replicated previous findings that words with low concreteness ratings are acquired earlier if they are highly valenced (positive or negative), and did so here with a set of items entirely comprised of verbs. These results are consistent with the claim that emotional information may provide a bootstrapping mechanism for the acquisition of abstract word meanings, and further highlight that this relationship holds when specifically considering the acquisition of verb meaning. When the sensorimotor information associated with a word’s meaning is operationalised as embodiment, we observed a different relationship between sensorimotor and emotional information. As hypothesised, valence provides no additional benefit to acquisition for low embodiment verbs, yet valence accounts for variance in age of acquisition when verbs are highly embodied, suggesting that embodiment and valence may capture some shared information involving the introspective experience of emotions. This interpretation is further supported by the results of the network analysis, which revealed that concreteness is negatively related to valence (irrespective of whether it is positive or negative), whereas embodiment is positively related to valence, meaning that more embodied verbs also tend to be more valenced.

Furthermore, the interaction between highly embodied verbs and valence demonstrates that for acquisition of these verbs, their specific valence matters. That is, highly embodied verbs associated with positive valence are acquired earlier (e.g. marry) and those associated with negative valence are acquired later (e.g. harass). These are the first findings to suggest that the polarity of valence matters for age of acquisition. Previous research investigating the role of valence in language acquisition has found that both positive and negative valence aids word acquisition. The present research suggests that, beyond the benefits that introspective, emotional experience (as captured by embodiment ratings) provide in acquiring language, there may be an additional benefit if that emotional experience is positive (as captured by valence ratings). One potential explanation is that negative concepts tend to be more granular (Jackson et al., Citation2022), and these more specific meanings might be acquired later than their more general counterparts. These novel results provide further insight into inconsistent findings on the effects of positive and negative valence in child language processing. For instance, Lund et al. (Citation2019) reported that 7-year-olds showed better performance responding to positive words in lexical decision tasks (LDT), independent of concreteness, but 6-year-olds showed an advantage for negative words in LDT. The present findings are correlational and so should not be interpreted too strongly but suggest that valence effects in child language processing should be further investigated. For instance, there would be value in examining effects of valence while systematically varying embodiment, as this may clarify the role of positive vs negative valence in child lexical semantic processing.

Our findings are consistent with those of Winter (Citation2023), who found that concrete words tend to be less valenced, whereas words with high sensory experience ratings or sensorimotor strength associations were more valenced, and both these patterns were observed in the differences between concreteness and embodiment in our network analysis and regression models. However, whereas Winter interpreted these differences as a limitation of the AEA proposal, our findings suggest that embodiment and valence are related because they both involve the human body, and therefore more embodied words should be more valenced. While these findings provide additional support for the AEA proposal, the lack of relationship between verbs with low embodiment ratings and valence suggests that emotional information may provide a bootstrapping mechanism for only some verbs that lack sensorimotor information. This is consistent with research suggesting that there are different kinds of abstract concepts (Conca et al., Citation2021) that should be further differentiated. Abstract concepts have tended to be treated as a homogeneous category and to be defined by what they lack, rather than by the dimensions that might comprise abstract concepts (Borghi et al., Citation2022).

In summary, the present study provides insight on how children acquire verb meaning by elucidating relationships between concreteness, embodiment, and valence. We replicated previous findings that abstract verbs are acquired earlier if they are associated with emotional information, supporting the AEA proposal. Further, we provided evidence that emotional information may facilitate embodied verb acquisition, with emotional experience being captured as a dimension of relative embodiment. We also showed limitations of the AEA proposal, with a subset of verbs that are not embodied and whose acquisition is not aided by emotional information. Our findings indicate a role for emotions in the early acquisition of abstract and highly embodied verbs but suggest that emotion cannot solely account for the acquisition of word meaning in the absence of sensorimotor information. Other mechanisms must be in play and should be the focus of future research.

Authors’ note

This work was supported by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) of Canada Insight Grant awarded to PMP. The authors report there are no competing interests to declare. The authors made the following contributions. EJM: Conceptualisation, Methodology, Formal Analysis, Data Curation, Writing – Original Draft, Writing – Review & Editing, Visualisation. PMP: Conceptualisation, Methodology, Writing – Review & Editing, Supervision.

C&E_SI_VerbDevSupp_R1.docx

Download MS Word (38 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Barsalou, L. W. (2008). Grounded cognition. Annual Review of Psychology, 59(1), 617–645. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.59.103006.093639

- Borghi, A. M., Binkofski, F., Castelfranchi, C., Cimatti, F., Scorolli, C., & Tummolini, L. (2017). The challenge of abstract concepts. Psychological Bulletin, 143(3), 263–292. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000089

- Borghi, A. M., Shaki, S., & Fischer, M. H. (2022). Abstract concepts: External influences, internal constraints, and methodological issues. Psychological Research, 86(8), 2370–2388. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00426-022-01698-4

- Brysbaert, M., & New, B. (2009). Moving beyond Kučera and Francis: A critical evaluation of current word frequency norms and the introduction of a new and improved word frequency measure for American English. Behavior Research Methods, 41(4), 977–990. https://doi.org/10.3758/BRM.41.4.977

- Brysbaert, M., Warriner, A. B., & Kuperman, V. (2014). Concreteness ratings for 40 thousand generally known English word lemmas. Behavior Research Methods, 46(3), 904–911. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-013-0403-5

- Conca, F., Borsa, V. M., Cappa, S. F., & Catricalà, E. (2021). The multidimensionality of abstract concepts: A systematic review. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 127, 474–491. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2021.05.004

- Cortese, M. J., & Fugett, A. (2004). Imageability ratings for 3,000 monosyllabic words. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers, 36(3), 384–387. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03195585

- Gentner, D. (2006). Why verbs are hard to learn. In K. A. Hirsh-Pasek, & R. M. Golinkoff (Eds.), Action meets word (1st ed, pp. 544–564). Oxford University PressNew York. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195170009.003.0022.

- Gleitman, L. R., Cassidy, K., Nappa, R., Papafragou, A., & Trueswell, J. C. (2005). Hard words. Language Learning and Development, 1(1), 23–64. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15473341lld0101_4

- Isvoranu, A.-M., & Epskamp, S. (2023). Which estimation method to choose in network psychometrics? Deriving guidelines for applied researchers. Psychological Methods, 28(4), 925–946. https://doi.org/10.1037/met0000439

- Jackson, J. C., Lindquist, K., Drabble, R., Atkinson, Q., & Watts, J. (2022). Valence-dependent mutation in lexical evolution. Nature Human Behaviour, 7(2), 190–199. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-022-01483-8

- Kim, J. M., Sidhu, D. M., & Pexman, P. M. (2020). Effects of emotional valence and concreteness on children’s recognition memory. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.615041

- Kuperman, V., Stadthagen-Gonzalez, H., & Brysbaert, M. (2012). Age-of-acquisition ratings for 30,000 English words. Behavior Research Methods, 44(4), 978–990. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-012-0210-4

- Lund, T. C., Sidhu, D. M., & Pexman, P. M. (2019). Sensitivity to emotion information in children’s lexical processing. Cognition, 190, 61–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2019.04.017

- Muraki, E. J., & Pexman, P. M. (2024). English Verbs Semantic Norms Database: Concreteness, Embodiment, Imageability, Valence and Arousal Ratings for 2,900 Verbs. Retrieved from osf.io/preprints/psyarxiv/wqsjc.

- Palazova, M., Sommer, W., & Schacht, A. (2013). Interplay of emotional valence and concreteness in word processing: An event-related potential study with verbs. Brain and Language, 125(3), 264–271. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bandl.2013.02.008

- Pexman, P. M. (2019). The role of embodiment in conceptual development. Language, Cognition and Neuroscience, 34(10), 1274–1283. https://doi.org/10.1080/23273798.2017.1303522

- Ponari, M., Norbury, C. F., & Vigliocco, G. (2018). Acquisition of abstract concepts is influenced by emotional valence. Developmental Science, 21(2), https://doi.org/10.1111/desc.12549

- R Core Team. (2022). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. (4.2.1) [Computer Software]. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. https://www.R-project.org/.

- Reggin, L. D., Muraki, E. J., & Pexman, P. M. (2021). Development of abstract word knowledge. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 686478. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.686478

- Sidhu, D. M., Kwan, R., Pexman, P. M., & Siakaluk, P. D. (2014). Effects of relative embodiment in lexical and semantic processing of verbs. Acta Psychologica, 149, 32–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actpsy.2014.02.009

- Troche, J., Crutch, S. J., & Reilly, J. (2017). Defining a conceptual topography of word concreteness: Clustering properties of emotion, sensation, and magnitude among 750 English words. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1787. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01787

- Vigliocco, G., Meteyard, L., Andrews, M., & Kousta, S. (2014). Toward a theory of semantic representation. Language and Cognition, 1(2), 219–247. https://doi.org/10.1515/LANGCOG.2009.011

- Warriner, A. B., Kuperman, V., & Brysbaert, M. (2013). Norms of valence, arousal, and dominance for 13,915 English lemmas. Behavior Research Methods, 45(4), 1191–1207. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-012-0314-x

- Winter, B. (2023). Abstract concepts and emotion: Cross-linguistic evidence and arguments against affective embodiment. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 378(1870), 20210368. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2021.0368