ABSTRACT

An expanding aging population has placed increased demands on health care resources in many countries. Enhancing community aged care support workers’ role to support greater client self-management and reablement is therefore timely. This article presents perceptions of the impact of an Australian practice change initiative designed to enhance knowledge, skills, and confidence of support workers to support behavior change in clients with complex health care needs. A comprehensive training program was delivered in 2013. Methods included thematic analysis of interviews with clients, focus groups with support workers and coordinators, and collection of case studies of client/support worker behavior change interactions. Client, support worker, and coordinator responses were highly positive, reporting improvement in the quality of interactions with clients, client health outcomes, care coordination, communication, and teamwork. Mental health literacy remained the biggest knowledge gap. This research showed that support workers are ideally placed to be more actively involved in motivating clients to achieve behavior change goals.

Introduction

In many countries, increasing demand for health services, brought about by the growing burden of chronic disease in an expanding aged care population, poses significant challenges for the current and future health workforce. Complexity within aged care populations, due to multimorbid chronic physical and mental health conditions, and complex psychosocial circumstances that make engagement and care provision more difficult, requires a multilayered, flexible workforce approach to enable shared responsibility and early intervention across the workforce and health system (National Health Priority Action Council [NHPAC], Citation2006; Productivity Commission, Citation2011; Segal & Bolton, Citation2009). In particular, psychosocial complexities affect clients’ health, use of primary health care services, and the rate of hospital emergency department presentations.

In Australia, a number of broad initiatives have aimed to provide a strategic approach for dealing with current and projected health workforce shortages. These initiatives include enhancing the skills of the current workforce and broadening the scope of support-level roles including assistants, carers, and volunteers. The rationale for this latter focus, referred to by Denton, Brookman, Zeytinoglu, Plenderleith, and Barken (Citation2015) as “task shifting,” is that it would release professional staff time to work to their top of license, enabling more coordination and complex case management to occur, and ensure optimal utilization of the support workforce and professional/specialist roles (Moran, Nancarrow, Enderby, & Bradburn, Citation2012).

This more effective use of workforce skills is particularly important for the aged care workforce. Recent aged care sector policy changes have called for the introduction of national focus on consumer-directed care (CDC) practices within packaged care and the Home Support Program for older Australians, from July 2015 (Australian Government Department of Social Services [AGDSS], Citation2015a, Citation2015b). These changes require care coordinators and support workers across aged care services to develop a new set of cultural, professional, and business skills and mind-sets if they are to continue to deliver quality services to this population into the future. Given the nature of the aged care workforce, many staff will require support and up-skilling to adapt to these new requirements.

To assist the shift to CDC, Health Workforce Australia (HWA), a leading national strategic workforce agency tasked with driving change, collaboration, and innovation to build a sustainable health workforce, undertook extensive work in promoting research and innovation involving the support worker workforce, before its essential functions were transferring to the Department of Health by the existing federal government. HWA (Citation2014a) argued that, “There is significant potential for this workforce to help meet the challenges posed by workforce shortages, escalating costs and increasing demand and systemic barriers. To date, this potential has not been met” (p. 5). They further argued that support workers are:

a group of importance and interest in their own right across health, aged care and disability services … They bring important attributes that are valued by clients and carers. Their core attributes as helpers and enablers, companions, facilitators and monitors are specific to their practice and operate as a bridge between themselves, clients and professionals. These generalist skills (e.g. health education, early identification of deterioration and lifestyle management) can be used to create efficiencies and flexibility within and across teams, and community or acute care (HWA, Citation2014a, p. 9).

Support workers make up more than 80% of workers within community aged care environments (King et al., Citation2012). Their role has predominantly been to perform hands-on, everyday personal care tasks to a largely passive client group (i.e., clients who are content for others to make care decisions for them and expect others to do so all or most of the time). Within this model of care, neither clients nor support workers have been encouraged to focus on clients’ self-management of their health (AGDSS, Citation2015a; Muramatsu et al., Citation2015; Neysmith & Aronson, Citation1996). However, because of their familiarity with clients’ everyday needs and their trusted relationships with clients, support workers are in an ideal position to communicate clients’ needs to care coordinators in a more straightforward and timely way, identify adverse changes in clients’ health and well-being, and provide motivational support that is client centered and realistically targeted to clients’ identified needs and goals, leading to more positive care outcomes (Martin & King, Citation2008; Mellor et al., Citation2010; Menne, Ejaz, Noelker, & Jones, Citation2007; Ryan, Nolan, Enderby, & Reid, Citation2004). Yet these workers have largely been excluded from chronic condition care coordination pathways and planning, despite their vital role in communicating client progress and issues of concern. Care coordinators have been reluctant to delegate and therefore to maximize support workers’ interactions with clients and their communication with professional staff (Mellor et al., Citation2010; Menne et al., Citation2007; Munn, Tufunaru, & Aromataris, Citation2013).

This article reports on a large interagency community aged care project that aimed to enhance the role and capacity of aged care support workers to work with complexity and support greater client self-management (HWA, Citation2014a, Citation2014b). It reports on the outcomes of qualitative data from in-depth interviews with clients and focus groups with support workers and care coordinators that sought their perceptions of the impact of complexity competent support workforce training developed for this purpose on the care provided by support workers to clients. It complements quantitative evaluation of that training, using a series of pre- and postsurveys, reported elsewhere (Lawn, Westwood, Jordans, & Keller, Citation2016). The research was guided by two key objectives:

To explore whether provision of specific training to support workers that focused on enhancing their skills in working with clients with complex needs can have a positive impact on clients’ engagement with care.

To investigate whether this training can facilitate support workers to play a more active role in supporting clients’ behavior change.

Method

The context of training

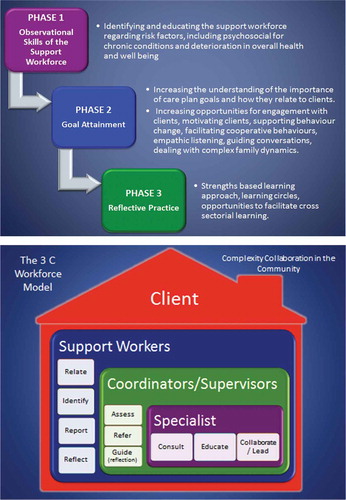

This qualitative exploratory research was conducted for HWA (Citation2014a, Citation2014b). Its focus was on exploring impacts of training designed to enhance the role of support workers to support coordination of care for older people with complex needs, building their capacity to support client self-efficacy for CDC, and to identify and respond to risk associated with complexity. This involved development and testing of a complexity competent support workforce model (see ). This model identified the client as central to the care process, and the roles that each of the workforce levels play. Where previous care models tended to represent clients as passive bystanders, in this approach, workforce groups work with clients in a reablement and CDC approach that supports more active self-management by the client in partnership with support providers (Pascale, Citation2013; Pitts, Sanderson, Webster, & Skelhorn, Citation2011). Training workshops were delivered in three phases to support the education needs of the support worker workforce towards this new model of care. See for further details about these phases and workshops.

Table 1. Phases of Workshop Delivery.

Setting

The project was undertaken as a partnership between five aged care services for people with complex needs living in the community, in metropolitan and rural South Australia. Services included a Community Complex Care team (based at the Local Health Network), two community nongovernment providers of aged care packages, a community domiciliary care service, and a rural country health service providing domiciliary-type services and aged care packages.

Ethical considerations

Ethics approval was granted by the region’s Clinical Research Ethics Committee. All personal and service data was deidentified. Participation was voluntary, with signed consent from all participants. Participant information sheets were provided to all participants. Clients and workers could choose not to participate, or to withdraw, at any time with no adverse effect on their relationship with the service.

Participants

Client participants were older people (age 65+) living in the community, and who were frequent users of hospital (at least two unplanned presentations per year) and other acute care services as a result of multiple comorbidities and other psychosocial complexities. Clients were living independently in the community in their own homes or within clustered housing units and receiving a range of supports such as personal care, physiotherapy and occupational therapy aide support, social support, transportation and shopping assistance, house cleaning, and welfare check visits. Support worker participants were paid community workers providing the above range of services to the aged care population. Most support worker participants (approximately 90%) were women, age between 25 and 60 years, and White, with English as their first language, and without tertiary education. Support workers were named differently in each organization as “paramedical aide,” “support worker,” “care worker,” or “personal care worker.” Coordinators were health professionals (largely from the professions of social work, physiotherapy, occupational therapy, and nursing), and also predominantly women, providing direct supervision to support workers, or who interacted directly with them because they provided health professional case management to clients. Specific sociodemographic data for support workers and coordinators was not collected.

Recruitment and data collection

Clients were recruited voluntarily and purposively via key staff in each service who approached coordinators to nominate potential clients who met the inclusion criteria of receiving support worker services, having complex care needs and cognitive capacity to provide informed consent for interviews, as determined by coordinators. Clients with a clearly established diagnosis of dementia were excluded where this diagnosis would impair their capacity to provide informed consent and to be interviewed. It is quite possible that some participants might have had early-stage dementia, whether diagnosed or undiagnosed; though this was not recorded during data collection. Project budget constraints limited the researchers to the conduct of a small number of client participant interviews. They were therefore concerned that they could not do justice to the experiences of subpopulations such as clients from culturally diverse backgrounds. They therefore limited the sample to one general demographic for this study; that is, those who could speak English clearly and did not require an interpreter.

In-depth interviews were undertaken with two clients of each of the five services involved in the project (n = 10) prior to project training activities (November–December 2012). Seven of these participants were then reinterviewed at the end of the project (November, 2013). Interviews ranged from 50 to 100 minutes and were conducted by the lead researcher to improve consistency. Interview processes were supported by an interview guide that was established in consultation with the project reference group (see ). One participant had died during the year and two participants (a husband and wife who were no longer registered with the service) were contacted for follow-up interviews; however, they did not wish to participate. All follow-up client participants were women, age 66 to 97 years. Of the initial 10 client participants interviewed, five lived alone, three lived with family (one as carer for a sibling), and two lived in supported community care housing. Data saturation was not achieved because the number of clients to be recruited was predetermined by the project’s budgetary parameters.

Table 2. Client Interview and Worker Focus Group Guide Questions.

Table 3. Case examples of supporting clients’ motivation and behaviour change.

Three focus groups were conducted with support workers across the five services (N = 24) and one combined focus group was conducted with coordinators of these services (N = 8) near the end of the project. All focus groups were 120 minutes in length and were conducted by the lead researcher to improve consistency, and supported by separate interview guides, established in consultation with the project reference group (see ). Support workers and coordinators were recruited voluntarily through information provided by key staff for each service. All focus groups were held at mutually agreed service locations and times. Arising from interviews with clients and focus groups with support workers and coordinators, we gathered qualitative case study examples highlighting how the project had impacted the clients and workforce.

Data analysis

Descriptive thematic analysis was used to report patterns within the data from interviews and focus groups, using Braun and Clarke’s (Citation2006) six-phase process: (1) familiarizing oneself with the data, (2) generating initial codes, (3) searching for themes, (4) reviewing themes, (5) refining and naming themes, and (6). producing the report. Interviews were audio-taped and transcribed verbatim by a professional transcription service. Transcripts were sent to those client participants who agreed to receive them, for checking accuracy and contextual meaning and providing them with an opportunity for further reflective comments (two participants took up this option, though made no changes to their comments). Client interview transcripts from the beginning and the end of the project were coded using this approach, soon after interviews were conducted. Then, at the end of the project, matched pre–post interviews were scrutinized by the research team; paying particular attention to any reported shifts in clients’ experiences across the time period.

For all interviews and focus groups, transcripts were read and reread, then manually open-coded by the lead researcher to identify data features that seemed interesting and meaningful. Codes evolved following critical discussions between the researchers, discussions during project reference group meetings, and presentation to the services at the conclusion of the project. Mind maps assisted the researchers to understand data relationships and patterns and provided overall conceptualization of the data. Field notes and reflections were incorporated into all stages to ensure reflexivity and interpretive rigour. Final analysis involved the write-up of a coherent logical story and inclusion of meaningful extracts of participants’ words to demonstrate each idea. Case studies were maintained as narratives, drawn from verbal and written stories, as told by support workers, and corroborated by clients and coordinators.

Results

Themes from client interviews are reported first, followed by themes from focus groups with support workers. A series of case studies from support workers are then provided to demonstrate their changed practice. This is followed by themes from focus groups with coordinators; then gaps that remained for support workers and coordinators. Pseudonyms are used for client quotes.

Clients’ interviews

Interviews with clients elicited four broad themes focused on the importance of support workers’ role, how training made them more inclusive of clients’ needs, how they became better at identifying risks earlier, and the health outcomes of these changes for clients.

The importance of the role

Clients did not initially perceive that the support they received had changed. This is primarily because most already thought their support workers were “wonderful.” They stressed the importance of the role and relationship, of the support worker understanding their needs and preferences, and the existing skills of support workers:

I’ve always felt comfortable, you know, with them … they have a lot of skills (Ruth, 94).

She knows everything about, you know, my health, my care, what I need, more so really than my daughter because she’s with me so much more. She sees me very much in my day-to-day life, and in all kinds of situations [laughing] you know, yes (Betty, 88).

Training has made support workers more inclusive of clients

However, on further questioning about whether they had noticed any change in the support workers’ interactions with them, one half of the clients reported that they had noticed their support worker asking them more questions about their health and well-being. They said this helped them to feel more included in decision making as part of support workers being more collaborative. Contrary to being challenged by this because they might assume that support workers were there to do the tasks, clients said they valued being included more:

They seem to be talking to me more about what I might want to do … And they suggest little things to me to get out and do things … they just care about what you’re doing and where you’re going … It’s certainly not a situation where they come in and tell me their version of what I need to do. They listen to me. They often will ask a question about something, “What do you think I should do because of this or that … Does this look normal to you?” (Gwen, 89).

Identifying risks and needs earlier

Clients gave clear examples of how they felt their support workers had developed more skills and appeared to be focusing on identifying issues of concern earlier than previously:

I didn’t ever know that if you had a bladder infection you could become a little bit disoriented … and this particular day she asked me, “Well you haven’t got a bladder infection by any chance have you? Is everything going fine?” (Beth, 85).

They’ve ganged up on me a little bit more! (laughs). And they decided that I need more help … So that’s sort of been helpful, I must admit … I think they felt I wasn’t coping, whereas I thought I was and of course this is where the independence gets to be a bit of a nuisance … I think they’d had a conversation with the coordinator. She rang and she said, “How about having XXX come every week instead of just every fortnight?” and I said, “Oh, what would she do?” “She could help with this or that or whatever you choose.” So the support workers were the messengers … taking a little bit more sort of notice (Ruth, 94).

Evidence of improved health outcomes

Some clients clearly felt that their health had improved during the project period. This may not have been directly because of the project and changes in the way the support workers were working with clients. However, the marked differences in demeanor and comments from the following client who was referred to the service following a suicide attempt and who was quite depressed still at the beginning of 2013 are impressive. They suggest that support workers played a significant role in improved communication, awareness of mental health needs and engagement of this client:

My health has actually been better this year. I’ve been really impressed with my health. It’s different now … (What’s different?) I just think it’s depending on relationships really that is such a bonus. We so look forward to them coming and sort of sharing their lives and they share ours. They’re almost intuitive and are so skilled at picking up when I’m struggling…. She arrived and saw me in this awful state and she immediately thought that I was going back into the depression bit. It wasn’t that, I was just feeling so rotten with the cold … She acted—she told the Coordinator and they rang Mental Health and they sent one of their—what are they called?—case worker people, yeah. They rang and made an appointment and then they took the trouble to ring my parish … They were really linking together quite well, absolutely great networking there. A good safely net … I realised the benefit of how important that is, because it was something we’ve never had before … They include me in making decisions or in talking about the things that I want to do … she and I work very well together … So it’s just having that undergirding of if something, if there is something on your mind … And there’s the social side of it, yeah … we’re more like sisters. The relationships have matured. I do treat them very openly about what I’m doing (Janet, 89).

Focus groups with support workers

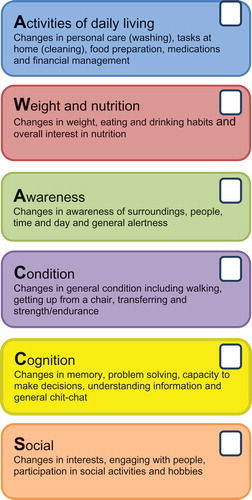

Results from focus groups with support workers elicited four broad themes related to the training, support workers’ perceived enhancement of their role, shifts in their thinking about their role, and perceptions of the risk assessment tool known as the AWACCS tool (that assessed any changes in Activities of daily living, Weight and nutrition, Awareness, Condition, Cognition and Social activities).

Support worker training

Support workers were overwhelmingly positive about the training they had received as part of the project. Their comments suggest that training is a key component of their ongoing role development; important for reflective practice and outcomes for clients, “I think it just makes us a bit more professional and you feel more confident in what you’re doing. You work better as a team” and “I think it did prod me to really observe and make sure that I was feeding back as much as I should be.”

Evidence of enhanced support

Support workers’ comments suggest that they enhanced their awareness of risk and support to clients as a consequence of the training; that they saw their role as more than delivering designated tasks, “I think I’ve asked more questions when I’m there [in client’s home],” “I feel that we are giving better care to our clients because we are more aware of the signs to look for … It gives you a basis of what to look out for,” and “It’s kind of made us feel more important I think rather than just go in there and think yeah, you’ve got to do domestic duties sort of thing.”

Changes in how support workers think, talk about, and practice behavior change support with clients

Support workers were asked about the impact of the second phase of training involving behavior change. Their comments show a clear shift in their thinking about how they work with clients. There were numerous examples of “change talk” in their comments about looking for opportunities, a hook to help open up conversation about change, and seeing the benefits to change of client self-efficacy:

So we might then talk about it. I’ve got that knowledge in my head now at least, that I’m going to keep an eye on it and I’ll find some opportunities if they come up.

I want to know something about them, that hook and how you can make it easier to engage with them; a common ground, to help them talk about what they want and what they need.

It’s very easy to do things for other people. Because you get it done quicker. So that was one of the things I picked up that day (at the training) is to actually enable them or empower them to feel like they’re achieving; that they can do it, yeah.

When I first started doing this role, I’d say “I’ll hang out the washing or I’ll do this”—you think you’re there to help them. But now I’ll say “Oh are you going to hang out the washing now?” So I might say “I’ll come out with you” but you actually let them lead. It might be the sheets and I help them with and then let them do the rest. I’ll say “That works well, your trolley’s good” so they feel like they’re actually achieving quite a bit, which they are. So instead of taking that away from them, you’re encouraging them to do it for themselves. You’re building their confidence.

From one of my ladies now when I go and do the domestic jobs, she’ll dust while I’m vacuuming and stuff like that, so that’s good. Because whereas before she just used to sit there. Or they’ll help make the bed. And I’ll say “Oh, would you like me to help you with it” so they think they’re making the bed. And like whereas I used to kind of take over and like they’ll get the pillowcases on and stuff like that rather than me just saying “I’ll do it.”

The AWACCS tool

Support workers overwhelmingly reported positive comments about the AWACCS tool that was developed for the project to assist them to recognize and report changes in complexity and risk for their clients (see ). They stated that this tool gave them a clear and formal structure to work by, to communicate issues of concern, and also provided a formal feedback process to them, which was a service gap they had noted at the commencement of the project:

The AWACCS tool, I think it’s really good because it’s on our phones. And the coordinator gets it instantaneously. And it comes up on their computer … you can then go to your next job and you’ve done your reporting there and then.

I think it made us take notice of the clients … whereas before I’d go in there and work away and yes, I guess I didn’t take much notice.

Previous to those forms I would just email my coordinator but I was never sure whether I would get a response or whether there was going to be a response to the client that had an issue because we weren’t—I didn’t get the feedback.

Case study examples of support workers changed practice

The case examples in provide further evidence of the shift in support workers’ understanding, thinking and practice in supporting clients’ behaviour change. The four case examples demonstrate ways that support workers had increased awareness and incorporated a new understanding of motivation and behaviour change into their role. Each example was perceived as leading to better health outcomes for the clients.

Focus groups with coordinators

Results from focus groups with coordinators elicited three broad themes related to broader aged care sector changes, impacts on organizational processes, and utility of the AWACCS tool.

The context of broader changes in the sector

Coordinators were overwhelmingly positive about the project and its impact on them and support workers. However, they were cognizant of the bigger picture of pressures for change within the sector, particularly around human resource management, balanced with clients’ potential to develop greater expectations of the service as a consequence of the changes.

I think it’s been a massive change for us implementing consumer directed care … educating ourselves and clients and care workers about what it means … Certainly the response from care workers in terms of reporting changes for clients has meant that they’ve been contacting us more frequently … more open communication. Where that has occasionally clashed … is what we’re then able to implement with the client doesn’t always match with what the carer wanted … because it’s a defined bucket … We have to be more creative with the way we dish it out and that can be difficult as well when they’ve had that same cleaning service for I don’t know how long.

Improved communication, teamwork, and skills

Impacts on organizational processes

Coordinators made several positive comments about the impact of the project on communication, teamwork and support workers’ skills generally. It was apparent that organizational and collaborative team processes had improved as a result of project activities.

The thing that has changed for us has been the fact that we’ve got the iPhones so the response time is a lot quicker. It’s just pressing a button and up it [the AWACCS] comes on the computer screen so that’s quick … I had one just before I came … so immediately I could ring the worker to say “Look, what’s happening with this man?” And she told me what was going on which was quite a concern so then I spoke to the daughter and left a message to ring me … We’re not having to wait for the advisor of that person to come into the office … So that really prompts some good communication and good collaborative working.

The AWACCS tool

Utility of the AWACCS tool

Like support workers, coordinators reported that the AWACCS tool provided a useful means of closing the feedback loop between team members providing care. However, coordinators’ comments demonstrated even further benefits for building a positive service culture. These included the ability for support workers to receive feedback on and recognition of their efforts and the feelings of team inclusiveness that this fostered:

In the past, personal support staff have commented, “Oh we reported this, and I’m sure something’s been done about it but we didn’t really get to hear much about what was done about it” … The fact that there’s space for the coordinator to actually write the action and they’re getting much more feedback and they like that … I think there’s more validation.

The AWACCS tool enabled support workers to recognize issues of concern with clients’ health status early and report these to coordinators early to avert the need for hospitalization. One example of this was the role played by a support worker in recognizing and reporting concerns about a client with a heart condition, having noticed a clear decline in the client’s general appearance and worsening fluid retention over the course of two weekend visits:

It did make a huge difference to this lady remaining home and not going to hospital. If they had have been reported later, she would have gone to hospital but it stopped that happening so that was great. It was a weekend shift so she was in on Saturday and she was in again on Sunday and it had changed quite considerably so she knew that if this wasn’t looked at quickly that something would happen. And the doctor was actually impressed which was good, and fed that back too, so that was good. Because the daughter took the person to the doctor and the doctor said he was really impressed with the timeliness of the whole process … So that worker now will probably be even more alert.

Gaps that remain

Support workers reported that they often had good informal communication with each other as part of understanding clients’ needs and filling in for each other. However, there were areas where they felt more improvement could be made to their role, their interaction with each other, and with coordinators. They wanted coordinators to be more aware of the complexity of the support worker role and their need for support:

I don’t think they realise what’s involved in all the things we do and the clients that we have to deal with like mental health clients and stuff like that … They think we just clean; you just clean them … They don’t realise how risky the job is out in the community, what we’ve got to deal with out there. They don’t realise any of that.

Knowledge and skills in working with clients with mental health issues (or where other members of the client’s family had mental health issues) continued to be an area identified as the biggest gap by support workers and coordinators:

I think the biggest thing and the biggest training everyone needs—and we’ve been asking for a while, is mental health training. More and more because we’ve had quite a lot of incidents that have been occurring or have occurred … (Interviewer: So what is it about mental health that is particularly challenging?) The triggers and how to handle them. Yeah, how to handle the behavior … having a bit of background and knowing what triggers them so you don’t accidentally say the wrong thing—You don’t want to get the aggressive side out … For us, our own safety … But yeah, because of the privacy laws, we are not allowed to ask about family members. We’re not allowed to know their health histories.

Support workers also said they would like more time to debrief, share and reflect on their work with support worker colleagues and with coordinators:

[Of supervision] Having some sort of formal process for making that happen sounds like a good idea … especially now when we’re getting more younger people with—like going into mental health … we really have no training for it. We really need then someone we can talk to.

Support workers and coordinators stated that this debriefing and supervision, with training topics with high relevance to their day-to-day work experiences, revisited at regular intervals to capture the needs of new staff and to help reinforce learning, would also help support workers to retain what they had learned:

I reckon we should revisit it because sometimes you learn so much and then you know—I think you take certain things in on the day but you can always learn more … Because it’s like when I first started as a domestic and then did some study, and because I was working with the clients at the same time I would think “oh yes, that’s what I’m doing and that’s what I should do” … if you don’t use it all the time, you forget it … And it’s a good reminder, I think, just to reinforce what you know.

Communication remained an issue requiring more improvement, especially in organizations where support workers did not meet regularly at the office. This seemed to work against improving support workers’ capacity to respond to complexity and suggested that adaptations to communication processes would still need to occur to maximize project benefits and support these workers more:

So at the meetings we used to be able to, when we had every month, to talk to people. If you had one client, say we could have the same client, or we could talk to each other about that client. Now we have got a new roster system … and they will ring you up. Like I’ve just got a new client who has got schizophrenia … and all I get was the care plan and her address. And I thought, but I have never dealt with anyone with schizophrenia. So then I had to ring up work and said to this person, “What do I need to know about her?” … We’re often going in blind.

We get told that there’s a care plan in their house, look at it when you get there, but you actually don’t know what you’re going to find when you get there or where do you find a care plan—In a drawer or in a cupboard? And they don’t want to show you sometimes. And also sometimes you feel a bit rude—well I feel a bit rude if I go in there and I start reading the care plan in front of them. It’s better to read it beforehand.

Discussion

This study showed that support workers can and do add value to health care teams and to care provision to enhance CDC and support clients’ behavior change because of the inherent nature of their relationships and roles with clients. Client participants already valued support workers as trusted “friends” with whom they shared their lives and concerns. Though not always recognised formally as “skills’”, these attributes present opportunities for enhancing support workers’ role in supporting clients to become more goal-oriented toward behaviors that maximize their self-management capacities. Support workers were ideally positioned to assess changes in clients’ health and to maximize clients’ engagement in their own health care on a routine basis. Others have noted the value of support workers; that their life experience is often an asset that gives them maturity to cope with the wide range of situations they come across in their role (Coogle, Parham, Jablonski, & Rachel, Citation2007; Pender & Sillsbury, Citation2014). Evidence from focus groups and individual cases clearly demonstrated changes in thinking and practice for support workers as a result of the training they received. They showed greater understanding of the importance of client-centered, motivational approaches to client care. This involved recognition that it is not about the workers’ authority to provide care but encouraging clients’ confidence and control over their own situation, and that this can be built regardless of clients’ level of complexity. This meant having a focus on “doing with,” rather than “doing for” clients. The opportunities they have, through the closeness of their relationship with clients, to engage in everyday conversations about the barriers and enablers to clients’ goal achievement, were evident from the case studies. It was very apparent that trust and rapport were key relationship elements between support workers and clients that aided CDC aspirations and engaged clients in this new approach to care. Valuing this relationship as the first step toward improving client outcomes was a key focus of the project model.

There was also growing acceptance and awareness of the value of the support worker role by coordinators within the services, though support workers felt even more communication and opportunities for shared reflection were needed. Lizarondo et al.’s (Citation2010) review of the literature on allied health assistants (AHAs) identified a range of barriers to expanding their role. These included uncertainty regarding the scope of their roles and responsibilities, protectionist attitudes of health professions, and feelings of inadequacy by AHAs about their skills (p. 152). Likewise, Denton et al.’s (Citation2015) study of task shifting found that health professional staff (in similar roles to the coordinators in this study) were concerned about the quality of care due to support workers’ perceived lack of ability to perform more complex tasks with clients. In our project, the support workers’ skills were clearly apparent, to them and their coordinators, in the outcomes they began to achieve with clients, as demonstrated in the case examples and clients’ interview responses. Seeing positive consequences of their efforts appeared to act as a reinforcement to strive to translate this new knowledge into their practice; a phenomenon also noted by Coogle et al. (Citation2007). The training methods also enabled critical reflection on their practice, by using case scenarios applicable to their everyday work. Similar to other studies (Munn et al., Citation2013) mentorship and supervision support were identified by participants as highly desirable for their continuous learning beyond the training.

All community aged care organizations in Australia face similar challenges in terms of resources, time, and funding; and they often compete with each other for funding of their services. In this project, there was value in working collaboratively between organizations with differing governance structures. The introduction of shared training, tools, and processes contributed to opportunities for the sharing of ideas and knowledge. This allowed the introduction of processes designed to assist support workers that might not have been achievable within individual organizations. Shared learning might be particularly important if they are to increase their capacity and confidence in working with people with complex physical and mental health needs. Munn et al.’s (Citation2013) systematic review and metasynthesis of qualitative studies about health assistants and their training for new models of care confirmed that shared training improves working relationships, respect and communication between professionals and assistants.

Support worker satisfaction also appeared to have improved through the project. This may have an impact on retention rates, which is a workforce issue identified in the literature (Radford et al., Citation2015). However, evaluation of longer-term impacts on client care is needed. The current policy and practice moves in Australia, toward a CDC approach and more interprofessional care, are areas of significant change for many in the aged care workforce and their organizations. Therefore, the concepts covered in the project will become even more important to enhance support workers’ skills and clients’ active partnership in their own care and acceptance of support workers enhanced role.

A number of policy and practice implications are also apparent. Support work is typically low-wage work; however, as support workers take on a more complex role in community health care, it is unclear how equity in remuneration for these improved skills will be realized within an environment of ever tighter fiscal constraint. Effective CDC, like other models of collaborative care generally, takes time. Convincing governments of the long-term health and financial benefits of this approach, and resourcing it adequately, will be ongoing challenges. Investment in information technology to assist the support worker workforce tools such as the AWACCS seems warranted, given the benefits to assessment and communication apparent in this project. The CDC initiative has also “shaken” the traditional hierarchical model of aged care delivery, characterized by professional case management models and professional dominance with support workers in quite restricted ancillary roles, across many provider agencies in Australia. Therefore, perceived threats to professionalism will need to be managed to allow this new model of care to flourish.

Limitations

This study had a number of limitations. Data was drawn from a small sample of clients and workers, with most being women. There may have been selection bias by services as part of identification of client participants. This was minimized by the researcher emphasizing to service recruitment staff that clients with positive and negative experiences of care should be considered. During interviews with clients, five of 10 participants spoke freely about negative experiences of receiving support from the service. Another limitation was that the views of family carers were not elicited. Sims-Gould and Martin-Matthews’ (Citation2010) study of sharing the care suggests that this is an important consideration. The study did not examine impacts for other important aged care populations, in particular, people with dementia and those from culturally diverse backgrounds. More systematic capture and quantitative measurement of improvements in client outcomes is also warranted. Likewise, this study did not elicit sociodemographic characteristics of support workers or coordinators, in detail. It was therefore unable to determine any further potential patterns of interest that may have affected the data, such as workers’ level of experience or age.

More broadly, the findings represent experiences within one aged care system that may not be generalizable to other countries or aged care contexts. The findings also represent experiences within a limited number of aged care services in Australia. However, it can be argued that aged care service structures are relatively homogeneous in Australia. Aged care service providers are regulated by national authorities, and the workforce is regulated by national authorities and training organizations. Likewise, aged care service providers comprise a number of organizations that often possess services in multiple locations across more than one state. The models and structure of service delivery are quite similar in many respects across services. The service types included in this study are typical of those found in Australia’s urban and regional areas. One of the services was located in a rural context. Aged care services to remote communities in Australia are quite limited or nonexistent in some contexts; therefore, this is a further limitation.

Conclusions

The qualitative findings reported here suggest that support workers clearly demonstrated their capacity to understand many core concepts around motivation, goal setting, and behavior change. Learning activities within the training allowed them and others to recognize the depth and complexity of the care they deliver. There was also clear value in combining support workers and coordinators from different organizations within the same learning space, to share ideas and to learn with, from, and about each other as part of effective interprofessional learning. This enhanced collaborative working environment built respect for support workers’ role and provided an opportunity for service teams to consider how they might embed their learning into their service structures. The motivational exercises generated thinking about what clients actually want and that support workers can play an integral part in supporting clients’ behavior change; that their role was not about support workers asserting authority over clients but was about encouraging clients’ control over their own situation. These concepts are critically aligned with the current CDC approach being promoted across Australia. Health care policy makers and services should account for support workers’ valuable contributions, given the growing climate of fiscal restraint and greater focus on reablement and CDC within aged care services. These contributions may be best supported with more opportunities for individual and team reflection and continuous learning embedded into supervision and support to this workforce.

Acknowledgment

We would like to thank the participants of this study for their time and commitment across the project.

Funding

This project was funded by a grant provided to Southern Adelaide Local Health Network (SALHN) by Health Workforce Australia.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Australian Government Department of Social Services. (2015a). Aged care reform. Retrieved from https://www.dss.gov.au/our-responsibilities/ageing-and-aged-care/aged-care-reform

- Australian Government Department of Social Services. (2015b). Consumer directed care (CDC). Retrieved from http://www.myagedcare.gov.au/aged-care-services/home-care-packages/consumer-directed-care-cdc

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Qualitative research analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Coogle, C. L., Parham, I. A., Jablonski, R., & Rachel, J. A. (2007). The value of geriatric care enhancement training for direct service workers. Gerontology & Geriatrics Education, 28(2), 109–131. doi:10.1300/J021v28n02_08

- Denton, M., Brookman, C., Zeytinoglu, I., Plenderleith, J., & Barken, R. (2015). Task shifting in the provision of home and social care in Ontario, Canada: Implications for quality of care. Health & Social Care in the Community, 23(5), 485–492. doi:10.1111/hsc.2015.23.issue-5

- Flinders Human Behaviour and Health Research Unit. (2015). The Flinders program. Adelaide, Australia: Flinders University. Retrieved from https://www.flinders.edu.au/medicine/sites/fhbhru/self-management.cfm

- Health Workforce Australia. (2014a). Assistants and support workers: Workforce flexibility to boost productivity: Summary report, July, 2014. Canberra, Australia: Department of Health. Retrieved from https://www.hwa.gov.au/sites/default/files/HWA%20Report%20Assistants%20and%20Support%20Workers%20short%20version_0.pdf

- Health Workforce Australia. (2014b). Expanded scope of practice and aged care workforce reform: Progress report. Adelaide, Australia: Author. Retrieved from http://www.hwa.gov.au/sites/default/files/Expanded-Scope-of-Practice-and-Aged-Care-Workforce-Reform-Progress-Report20140321.pdf

- King, D., Mavromaras, K., Wei, Z., He, B., Healy, J., Macaitis, K. … Smith, L. (2012). The aged care workforce, 2012. Canberra, Australia: Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing. Retrieved from http://www.cshisc.com.au/media/163387/The_Aged_Care_Workforce_Report.pdf

- Kumar, S., & Stanhope, J. (2014). The AWACCS tool for detecting decline in aged care clients. Retrieved from http://www.unisanet.unisa.edu.au/staff/Homepage.asp?Name=saravana.kumar

- Lawn, S., Westwood, T., Jordans, S., & Keller, N. (2016). Support workers can develop the skills to work with complexity in community aged care: An Australian study of training provided across aged care community services. Geriatric and Gerontology Education. Advance Online Publication. doi:10.1080/02701960.2015.1116070

- Lizarondo, L., Kumar, S., Hyde, L., & Skidmore, D. J. (2010). Allied health assistants and what they do: A systematic review of the literature. Multidisciplinary Healthcare, 3, 143–153.

- Martin, B., & King, D. (2008). Who cares for older Australians? A picture of the residential and community based aged care workforce. Adelaide, Australia: Flinders University, National Institute of Labour Studies.

- Mellor, D., Kiehne, M., McCabe, M. P., Davison, T. E., Karantzas, G., & George, K. (2010). An evaluation of the Beyondblue depression training program for aged care workers. International Psychogeriatrics, 22(6), 927–937. doi:10.1017/S1041610210000153

- Menne, H. L., Ejaz, F. K., Noelker, L. S., & Jones, J. A. (2007). Direct care workers’ recommendations for training and continuing education. Gerontology & Geriatrics Education, 28(2), 91–108. doi:10.1300/J021v28n02_07

- Miller, W. R., & Rollnick, S. (2012). Motivational interviewing: Helping people change (3rd ed.). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- Moran, A., Nancarrow, S., Enderby, P., & Bradburn, M. (2012). Are we using support workers effectively? The relationship between patient and team characteristics and support worker utilisation in older people’s community-based rehabilitation services in England. Health & Social Care in the Community, 20(5), 537–549. doi:10.1111/hsc.2012.20.issue-5

- Munn, Z., Tufunaru, C., & Aromataris, E. (2013). Recognition of the health assistant as a delegated clinical role and their inclusion in models of care: A systematic review and meta-synthesis of qualitative evidence. International Journal of Evidence-based Healthcare, 11(1), 3–19. doi:10.1111/j.1744-1609.2012.00304.x

- Muramatsu, N., Madrigal, J., Berbaum, M. L., Henderson, V. A., Jurivich, D. A., Zanoni, J. … Cruz Madrid, K. (2015). Co-learning with home care aides and their clients: Collaboratively increasing individual and organizational capacities. Gerontology & Geriatrics Education, 36(3), 261–277. doi:10.1080/02701960.2015.1015121

- National Health Priority Action Council. (2006). The National chronic disease strategy. Retrieved from http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/pq-ncds-strat

- Neysmith, S. M., & Aronson, J. (1996). Home care workers discuss their work: The skills required to use your common sense. Journal of Aging Studies, 10(1), 1–14. doi:10.1016/S0890-4065(96)90013-4

- Pascale, K. (2013). The goal directed care planning toolkit: Practical strategies to support effective goal setting and care planning with HACC clients. Alliance, Melbourne, Australia: Eastern Metropolitan Region HACC Alliance, Outer Eastern Health and Community Services. Retrieved from http://kpassoc.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/Goal-Directed-Care-Planning-Toolkit-Web-version.pdf

- Pender, S., & Spillsbury, K. (2014). Support matters: The contribution of community nursing assistants. Journal of Community Nursing, 28(4), 87–89.

- Pitts, J., Sanderson, H., Webster, A., & Skelhorn, L. (2011). A new reablement journey. Sheffield, England: Ambrey Associates. Retrieved from http://www.centreforwelfarereform.org/library/type/pdfs/a-new-reablement-journey.html

- Productivity Commission. (2011). Caring for older Australians. Report No. 53, Final Inquiry Report. Canberra, Australia: Government of Australia.

- Radford, K., Shacklock, K., & Bradley, G. (2015). Personal care workers in Australian aged care: Retention and turnover intentions. Journal of Nursing Management, 23(5), 557–566. doi:10.1111/jonm.2015.23.issue-5

- Ryan, T., Nolan, M., Enderby, P., & Reid, D. (2004). ‘Part of the family’: Sources of job satisfaction amongst a group of community‐based dementia care workers. Health & Social Care in the Community, 12(2), 111–118. doi:10.1111/hsc.2004.12.issue-2

- Segal, L., & Bolton, M. T. (2009). Issues facing the future health care workforce: The importance of demand modelling. Australia and New Zealand Health Policy, 6, 12–19. doi:10.1186/1743-8462-6-12

- Sims-Gould, J., & Martin-Matthews, A. (2010). We share the care: Family caregivers’ experience of their older relative receiving home support services. Health and Social Care in the Community, 18(4), 415–423. doi:10.111/J.1365-2524.2010.00913.x