ABSTRACT

Appropriately skilled staff are required to meet the health and care needs of aging populations yet, shared competencies for the workforce are lacking. This study aimed to develop multidisciplinary core competencies for health and aged care workers in Australia through a scoping review and Delphi survey. The scoping review identified 28 records which were synthesized through thematic analysis into draft domains and measurable competencies. Consensus was sought from experts over two Delphi rounds (n = 111 invited; n = 59 round one; n = 42 round two). Ten domains with 66 core competencies, to be interpreted and applied according to the worker’s scope of practice were finalized. Consensus on multidisciplinary core competencies which are inclusive of a broad range of registered health professionals and unregistered aged care workers was achieved. Shared knowledge, attitudes, and skills across the workforce may improve the standard and coordination of person-centered, integrated care for older Australians from diverse backgrounds.

Introduction

It is well established that the global population is aging rapidly (World Health Organization, Citation2015). Yet, despite growing numbers, current health systems fall short in the care of older individuals, continuing to focus on time-limited health conditions rather than the management and prevention of chronic conditions common in older age (World Health Organization, Citation2015). Furthermore, health systems lack adequate integration with long-term care systems, thus neglecting the chronic care and functional needs of older people (Eklund, Citation2009; Low L-F & Lap, Citation2011).

Growing evidence shows that quality of care and health outcomes can be improved, and hospitalization and costs decreased when there is an integrated, interprofessional (interdisciplinary) approach to older people’s care (Geriatrics Interdisciplinary Advisory Group, Citation2006; Goldberg, Koontz, Rogers, & Brickell, Citation2012; Martin, Ummenhofer, Manser, & Spirig, Citation2010; Tsakitzidis et al., Citation2016). Traditionally however, healthcare disciplines have worked independently to identify and address specific competencies relevant to their practice (Mezey, Mitty, Burger, & McCallion, Citation2008). This has promoted professional silos, and fostered in healthcare workers, ‘stereotypical ideas about their own and other disciplines’ (Goldberg et al., Citation2012, p. 101) limiting team-work and effective service delivery (Goldberg et al., Citation2012). Integrated person-centered care is enabled when health and social care providers work collaboratively, with a common purpose (World Health Organization, Regional Office for Europe, Citation2016). Shared knowledge, attitudes and skills for the care of older people across the workforce may help to facilitate this, and to address calls for better, more comprehensive training in gerontology and geriatrics (Australian Medical Association, Citation2019; Damron-Rodriguez et al., Citation2019; The Education Committee Writing Group of the American Geriatrics Society, Citation2000). However, attempts to identify multidisciplinary core competencies for the care of older people undertaken previously, have largely been restricted to professional degrees (see for example, (Semla, Beizer, Berger, et al., Citation2010). This has excluded vocationally trained care workers (also known as personal care workers or unregulated health-care workers) who also have extended contact with older people, and a critical role in the provision of quality care (Carnell & Paterson, Citation2017; Department of Health, Citationno date).

With the number of older people (65+ years) projected to increase over coming decades (from 14% of the population in 2013 to 21% in 2053), the optimization of their health and wellbeing has become an important economic, medical, and social challenge in Australia (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, Citation2014). Services provided by the health and aged care sectors in Australia are delivered by a large and diverse workforce (ranging from professionals to support staff) in hospitals and clinics, transition care services, and community-based and residential aged care (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, Citation2018). Appropriately skilled staff are required to adequately meet the changing needs and increased demands of this population (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, Citation2014); and to provide care that is also cognizant of, and responsive to the special needs of specific groups of older Australians, such as Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people (Aged Care Workforce Strategy Taskforce, Citation2018; AIHW, Citation2018). However, a recent consultation undertaken by the Australian Government-funded independent Aged Care Workforce Strategy Taskforce identified significant gaps in the competencies of Australia’s aged care workforce and highlighted the need for the education system, both vocational education and training and higher education, to produce a highly skilled and adaptable workforce better able to coordinate care across settings (community, residential aged care, and hospital) (Aged Care Workforce Strategy Taskforce, Citation2018).

Competency-based education defines training experience by desired outcomes, rather than by exposure to specific content and is increasingly favored by contemporary educators (Scott Tilley, Citation2008). In nursing and medicine for example, recent literature suggests that a focus on competencies will narrow the gap between education and practice and improve patient outcomes (Carraccio et al., Citation2016; Frank et al., Citation2010; Scott Tilley, Citation2008). Thus, in order to promote and inform needed workforce reform in Australia, this study sought to develop a framework of competencies that health and aged care workers should share in order to provide integrated, quality care to older people from diverse backgrounds, across all settings. This paper describes the process of competency creation, beginning with the identification of relevant competencies from the literature and followed by input from a panel of experts, and presents the consensus-based competencies developed.

Methods

The study was led by a multidisciplinary project team (MDPT) drawn from the Age and Aging Clinical Academic Group of the Sydney Partnership for Health, Education, Research and Enterprise (SPHERE) (Maridulu Budyari Gumal, Citation2020). SPHERE is focused on advancing healthcare, including ensuring that the healthcare workforce is prepared and capable of caring for older people. The study involved two phases of work, as shown in . The first phase was a scoping review to identify relevant competency frameworks from international and local sources from which the MDPT could develop draft multidisciplinary competencies for the Australian workforce; the second phase was a modified Delphi survey with an expert panel to finalize competencies through consensus. The project was approved by the UNSW Human Research Ethics Committee (HC180838).

Phase 1: competency generation

Study design

Phase 1 employed a scoping review design according to the methodological framework (five stages) recommended by Arksey and O’Malley (Arksey & O’Malley, Citation2005) to allow a thorough examination of the scope of existing competency frameworks in the care of older people, and to identify common domains across competencies.

In the absence of a set definition of ‘competency’ in the education literature (Frank et al., Citation2010), we adopted a definition based on the existing work of the Partnership for Health in Aging relating to competency development for healthcare professionals (Semla et al., Citation2010). We, therefore, defined competencies as the essential skills and the necessary approaches that health and aged care workers must have in order to provide quality care for older adults (Semla et al., Citation2010). The in-scope workforce was agreed by the project team to include medicine, nursing, dentistry, physiotherapy, occupational therapy, speech therapy, exercise physiology, nutrition, dietetics, optometry, orthoptics, podiatry, psychology, pharmacy, paramedicine, and social work. Also included were vocationally trained care workers with a minimum of Certificate III training. In Australia, the most common vocational qualification for those entering the aged and community care industry is a Certificate III qualification (Australian Skills Quality Authority, Citation2013). The Certificate III Individual Support is a generic qualification for community and residential care workers in which a diverse range of electives may be packaged together, and training is available from a wide range of registered training organizations (SkillsIQ, Citation2020).

Searches

An extensive search of the following databases: Medline/PubMed, CINAHL, ProQuest, Scopus, Cochrane, Embase and PsycINFO was conducted from October to November 2018. Individualized search strategies were developed according to the indexing terms and search syntax of each database, including Boolean operators, truncations and Medical Subject Headings (MeSH). Keywords used in these search strategies included: competency, entry-level, standard, proficiency, aged care, older people, healthcare workers, care workers, dentist, medicine, nursing, paramedicine, occupational therapist, physiotherapist, speech therapist, exercise physiologist, psychologist, social work, nutritionist, dietitian, pharmacy, optometry, orthoptist, podiatry. Furthermore, manual searches of related articles and other papers citing included references, as well as bibliographic mining were carried out. In addition, a search of the gray literature was undertaken to identify contemporary (in current usage) competencies related to the relevant workforces in Australia.

Eligibility criteria

Scholarly literature relevant to the study’s aims and published up to November 2018 were eligible for inclusion. No limitations were placed on study design, quality, or location; however, only material available in the English language were included. Eligible records met the following inclusion criteria:

Described competencies for the in-scope workforce, and

Referred to the care of older people in general, or in specific settings, and

Included or referred to two or more groups from the in-scope workforce

Records were deemed irrelevant if they met the following exclusion criterion:

Referred only to learning outcomes or competencies arising from a specific targeted educational activity (e.g. postgraduate short course), rather than to practice more generally.

Eligible gray literature included contemporary practice- or competency-based standards from Australian professional, accrediting, and training organizations for the in-scope workforce (for example, the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners), and relevant local documents known to the MDPT which related to competencies for the care of older people for the in-scope workforce in Australia (see ). These were mostly single-discipline competencies.

Table 1. Documents identified through the scoping review

Study selection and data extraction

A systematic screening process was conducted whereby initial search results were screened for eligibility first by title, then by abstract, and finally by full text. Document eligibility was determined independently by two investigators (AV with other team members), and a third investigator (RP) was used to achieve consensus when discrepancies arose. Key information regarding each included record, such as author, year, country, aims, and included workforces were extracted and presented in a summary table (). In addition, the competencies presented within each document were entered into QSR NVivo Pro Version 11 for further analysis.

Data synthesis and generation of competencies

Using an inductive, qualitative approach, competencies within relevant documents were grouped into themes. This was first conducted by a single investigator (AV), then a consensus meeting was held with the MDPT to confirm the themes, and to merge the themes into a final list of domains. Two investigators were then assigned to each domain to review the data and draft individual competencies that would constitute these domains, using measurable verbs and language inclusive for all health and aged care workers. A second team meeting was held to ensure that all drafted competencies were consistent in language and format, and to reduce overlap between domains. Competencies were then circulated to a second pair of investigators who verified the content and wording of the competencies. All changes were then confirmed at a third team meeting. This verified list of domains and competencies were returned to the first set of investigators who drafted an introductory statement for each domain to describe the intent of the domain. A final meeting was undertaken to verify the final list of competencies and introductory statements, which were then circulated to the MDPT for minor editorial feedback in preparation for phase two of the study.

Phase 2: consultation and consensus for competency framework

Study design

This phase followed a modified two-round Delphi survey technique (Hasson, Keeney, & McKenna, Citation2000), administered via an online survey and using a multidisciplinary panel of purposely selected experts (Creswell and Plano Clark Citation2011) from across the nation. Invited health professionals were well informed and/or experienced in working with older people or in aged care workforce training needs, or in aged care research, as indicated by industry or scientific publications, conference presentations, professional organization involvement, industry profiles, or known as an expert by the MDPT. Invited trainers or managers were considered well informed and/or experienced in the area of aged care, as indicated by the recommendation of a service provider, their years of experience in the sector, or known as an expert by the MDPT. All invited experts received a participant information statement with the invitation e-mail and indicated their informed consent to participate at the commencement of the survey.

The aim of the Delphi process was to achieve consensus on domains and multidisciplinary core competencies for the care of older people for Australian health and aged care workers.

In the first round (R1), the expert panel was presented with the list of competencies under defined domains (developed as described in Phase 1) and asked to rate each competency statement on a 5-point Likert scale (‘not at all relevant’ to ‘very relevant’) in response to the following question: In caring for older people, to what extent is this competency relevant across the health and aged care workforce? A priori it was agreed that the threshold for inclusion of a competency would be at least 80% of the expert panel scoring the competency as very or somewhat relevant. An opportunity to provide comments on the competencies within each domain, or to add additional competencies or domains was available via open-ended text boxes.

After R1, the MDPT reviewed both the quantitative and qualitative results and made revisions in response to ratings and comments. Revisions included the development of a preamble to describe the purpose of the workforce competencies, wording refinement to existing competencies, and the creation of additional (new) competencies under existing domains.

In round two (R2), the revised material was circulated to the expert panel, along with the quantitative results (percent scores on the Likert scales). A brief summary of the action taken by the MDPT in response to the results and comments from the R1 survey was also provided. In R2, the expert panel was asked to: rate the appropriateness of the preamble on a five-point scale (‘not at all appropriate’ to ‘very appropriate’); rate additional (new) competencies on a 5-point Likert scale (‘not at all relevant’ to ‘very relevant’); and where wording modification had been made to competencies, to indicate whether they were ‘satisfied’ or ‘unsatisfied’ with the change. An opportunity to provide comments on the preamble and competencies within each domain was available via open-ended text boxes.

Following R2, the MDPT again reviewed the quantitative and qualitative results, making minor modifications in response to the panel’s ratings and comments, and reached consensus on the final preamble, domains, and competencies.

Results

Phase 1

The initial search returned 1,430 documents, 28 of which met the inclusion criteria and were reviewed (). Ten described competencies for two or more health professions, and 18 were single discipline and Australian-based documents (). No contemporary documents containing competencies pertaining to a specialized qualification for vocationally trained aged care workers at Certificate III level in Australia were identified.

Initial inductive thematic analysis of the competencies extracted from the 28 records selected for review () identified 12 themes. After review by the MDPT, these were reduced to 10 domains and 65 multidisciplinary competencies relating specifically to the care of older people. An additional document (National Initiative for the Care of the Elderly, Citation2009) meeting the inclusion criteria was subsequently identified. Post-hoc inclusion of this document did not alter the outcomes of the original analysis.

Phase 2

The MDPT invited 111 experts to participate. Sixty-one opened the R1 survey, 59 of whom answered one or more survey questions (response rate per question ranged from 52% to 53%). As the survey was anonymous, those who only opened the survey could not be distinguished from those who answered, except for one expert who withdrew by e-mail. Therefore, 60 experts from R1 were invited to participate in the second round; 42 of 60 invited experts answered one or more survey questions in R2 (response rate per question ranged from 65% to 70%). shows the disciplines of invited experts, and those who responded to the survey.

Table 2. Distribution of discipline experts

In the R1 survey, the panel of experts reached at least 80% support for all 65 competencies listed, meeting the a priori threshold for the inclusion of a competency. No new domains were proposed by the panel. However, panel comments suggested refinements to some competencies to ensure relevance to all workers, or to improve their clarity. Some additional competencies were suggested, including supported decision-making and competencies around specific diseases and conditions, such as dementia, frailty, falls, and sarcopenia. Some panelists sought clarification as to whether level of competence would depend on level of training and scope of practice. Two panelists were concerned that the health and aged care system would fail to support some of the competencies:

“These competencies are best-practice but the system is not set up to have them occur” (Response 15)

“[The system] funds chronicity and dependency, it does not fund wellness, choice or restorative function” (Response 51)

In response to the panel comments, the MDPT produced a preamble to introduce the competencies and explain their intention and application, refined the wording of 23 competencies (one of which was intended to combine two of the original competencies), and formulated two new competencies.

In R2, the preamble was considered appropriate by 88% of the expert panel. A high level of support was also achieved for all refined competencies (≥80%), and both additional competencies (92.3% and 79.5%). In response to panel comments, the MDPT made further minor wording refinements to the preamble and some of the competencies to further improve clarity or ensure inclusiveness (for example, ‘older people’s choices’ replaced with ‘their chosen goals’; ‘medical practitioner’ with ‘clinician’; ‘educates’ replaced with ‘informs’); and for two refined competencies, panel comments suggested that the original competency might still be better.

The final document includes a preamble that explains the intended application of the competencies, 10 domains and 66 competencies. The first three domains reflect a holistic, person-centered and strengths-based approach to assessment, care planning and coordination, and care delivery; the fourth domain relates to the promotion of healthy aging; the fifth domain aims to promote effective interpersonal and communication skills so that sensory, cognitive, language, and cultural needs of older people are accommodated, and they are empowered and supported in decision-making; the sixth domain promotes an interdisciplinary team approach to caring for older people; domains seven and eight relate to sustainability and ongoing improvement of health and aged care systems to support older people, and improve the safety and quality of their care; the ninth and tenth domains promote workforce development in respect of professional skills and leadership in the care of older people. The domains are listed in . The competencies which underpin these domains recognize and respect diversity amongst older Australians and can be translated by educators and applied in ways which meet the needs of specific groups. The competencies are not discipline-specific and relate specifically to the care of older people. They apply to both the vocational and higher education sectors, and could also support training and staff development for those already in the workforce. See Appendix.

Table 3. Domains

Discussion

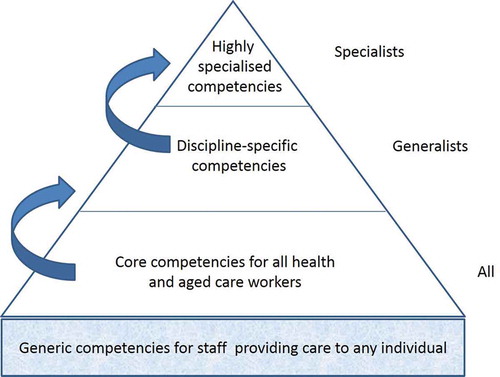

The development of a set of multidisciplinary core competencies for the care of older people for the health and aged care workforce in Australia involved the comprehensive review of relevant scientific and gray literature, repeated meetings of the MDPT, and a two-stage modified DELPHI survey with a broad range of experts. Sixty-six competencies across 10 domains were developed to foster a shared approach to care. To our knowledge, this represents the first attempt to provide a set of core competencies to guide education and training and improve the standard of care for older people, which are inclusive of a broad range of registered health professionals and unregistered care workers (with a minimum Certificate III training). These competencies are limited to those specifically related to the care of older people and are designed to be interpreted and applied according to the worker’s scope of practice. These shared competencies assume a strengths-based and person-centered approach to care (Moyle, Parker, & Bramble, Citation2014), and recognize diversity amongst older people. They may be considered to sit above generic competencies expected of staff providing care to any individual (for example, infection control), and to underpin the competencies specific to individual disciplines and to specialists within these disciplines. This hierarchy is illustrated in the pyramid shown in (adapted from (Walsh et al., Citation2012).

Figure 3. Hierarchical competencies for the care of older people (adapted from Walsh et al., Citation2012, p. 46)

While the Delphi methodology has been used to refine the number of competencies (Damron-Rodriguez et al., Citation2019; Lock, Citation2011; Witt et al., Citation2014), we found a high level of support (≥80%) for all initial competencies. This may reflect the systematic approach taken to the initial formulation and selection of competencies drawing on a scoping review, followed by extensive group work involving the MDPT whose members were themselves experienced in working with older people, aged care research, and workforce training, prior to undertaking the survey. The expert panel was selected because of their understanding of the nature of the roles and the environment in which workers are employed (McGaghie, Miller, Sajid, & Telder, Citation1978). Importantly, the expert panel confirmed the content validity of the competencies within each domain, identified additional competencies needed, prompted the development of the preamble, and assisted us to refine wording, particularly around ensuring the inclusiveness of competencies for all workers.

As these are shared competencies, we have excluded discipline-specific competencies (for example, competencies addressing diseases, diagnosis, and treatment traditionally emphasized in clinical disciplines), to focus on promoting the knowledge, skills, and attitudes necessary to underpin person-centered, integrated care for older people across the health and aged care sectors. This approach aligns well with international calls for re-aligned health and aged care systems to better meet the needs of older populations (World Health Organization, Citation2015). They also include competencies related to interdisciplinary practice, which has been recognized as central to the care and management of older people with complex needs, and one that may reduce care costs (Geriatrics Interdisciplinary Advisory Group, Citation2006). Our competencies include some of the identified key elements for collaboration such as a shared purpose and goals, shared knowledge, and an understanding of the roles and responsibilities of other team members (Hartgerink et al., Citation2014; Mezey et al., Citation2008). While support for interdisciplinary education and practice is strong, most healthcare professionals learn separately from other professions (Mezey et al., Citation2008). This is because there are many barriers to shared learning opportunities, such as full curricula, lack of incentives, and difficulties in scheduling (Skinner, Citation2001). The barriers are even greater for vocationally trained care workers who, in Australia, are trained through a range of registered training organizations in a system separate to the university system (Ey, Citation2018). Identifying shared competencies for the workforce is a necessary beginning to meet the challenge of interdisciplinary efforts, and provides a framework on which educational programs can be structured (Mezey et al., Citation2008; Schoenmakers, Damron-Rodriguez, Frank, Pianosi, & Jukema, Citation2017; Skinner, Citation2001). However, to be effective, these competencies need to be broadly adopted, utilized, and integrated into relevant curricula, and learner outcomes assessed and reviewed, with the intention of ongoing quality improvement of courses and programs (Damron-Rodriguez et al., Citation2019).

The Australian government is currently seeking significant reforms to improve the safety and quality of care provided to older Australians. This requires “a workforce with the right attitude and skills.” (Australian Government, Citation2019). In September 2018, the Aged Care Workforce Strategy Taskforce identified a range of strategies for workforce reform including: addressing current and future workforce competencies and skills; strengthening the interfaces and workforces across the continuum of care and systems (aged care, primary care, acute care, and dental services); and improved training for the aged care workforce (Aged Care Workforce Strategy Taskforce, Citation2018). These are supported by findings of the current Royal Commission into aged care quality and safety, which highlights the need for practical solutions to meet workforce challenges (The Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety, Citation2019). Multidisciplinary core competencies are thus an essential step to developing a basic level of shared knowledge, skills and attitudes across the workforce, and to begin to deliver care that is streamlined and coherent.

During the course of this current research, the Aged Services Industry Reference Committee (Australian Industry and Skills Committee, CitationNo date) was appointed to respond to the recommendations listed in the 2018 Aged Care Workforce Strategy. The Aged Services Industry Reference Committee plans to bring together the vocational and higher education sectors, along with industry, health professionals, and consumers ‘to set the competencies and skills needed to deliver safe, quality aged care services in Australia’ (Australian Industry and Skills Committee, Citation2018). Available information suggests its focus may be on workers in the aged services sector only, rather than inclusive of workers in the health sector (Australian Industry and Skills Committee, Citation2018). However, our findings suggest that it is possible to achieve consensus on competencies that are inclusive of the variety of workers who care for older people in different settings.

We suggest several directions for future research. The first is to review the curricula of university faculties and vocational training organizations against our identified competencies; and second, to examine the perceptions of health professionals and aged care workers on the extent to which their education has addressed these core competencies (Clark, Raffray, Hendricks, & Gagnon, Citation2016). The third is to work with specific and diverse communities of older people within Australia (for example, with our Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities, or our culturally and linguistically diverse communities) to explore ways in which educators can translate and apply our competencies in socially and culturally appropriate ways to meet their needs. While there was a high level of support for the competencies by our expert panel, there was some concern expressed amongst experts in the first survey that the health and aged care ‘system’ was not set up to support the outcomes sought by some of the competencies, for example, wellness, choice, and functional gain for older people. Thus, a fourth suggested direction of inquiry is to identify system issues which fail to support the application of competencies and limit the outcomes that can be achieved by competent workers. These areas of inquiry are essential to identify gaps in education, to inform educators in the development of curricula, and to advocate for change to better prepare and enable health and aged care workers to meet the needs of our aging population. Finally, the focus of this study has been on shared competencies for health and aged care workers. 'Multidisciplinary efforts' have been recognized as 'the logical step toward truly interdisciplinary ventures' (Skinner, Citation2001, p. 73). Thus, future research should also explore ways in which interdisciplinary education and training and the development of interdisciplinary competencies, can be supported (Skinner, Citation2001).

Limitations

A comprehensive literature search was undertaken to inform competency development; however, it is possible that relevant material was excluded. An initial survey response rate of 53% raises the possibility of selection bias which may overestimate the level of support amongst experts for the notion of ‘shared’ competencies, or for individual competency statements, or may have facilitated the achievement of consensus. A comprehensive disciplinary range was surveyed; however, it was not possible to have representation from all disciplinary groups who care for older people. Only two Delphi rounds were undertaken as we sought to reduce response fatigue amongst experts. Final changes, though minimal, were therefore made by the MDPT. Wider consultation with universities, training organizations, professional bodies, and the health and aged care sectors has not been undertaken. We did not have the opportunity to consult with older people themselves, and we recognize the potential benefits that co-production could have offered. While international literature was sourced, the MDPT and experts were drawn only from Australia, thus the generalizability of the competencies may be limited.

Conclusion

Sixty-six competencies across 10 domains have been developed to foster a shared approach to the care of older people for the Australian health and aged care workforce. These were informed by the literature and a multidisciplinary panel of experts. Wider consultation with key stakeholders may assist in refining the competencies further. Experience elsewhere suggests that while competency-based frameworks can be an effective method to achieve outcomes-based education that better aligns the abilities of workers with the needs of those for whom they care (Frank & Danoff, Citation2007), widespread support is required for effective implementation (Damron-Rodriguez et al., Citation2019). With an aging population, and Australian Government calls for workforce reform, there is an opportunity to consider the role of shared multidisciplinary competencies in preparing the future workforce.

Declaration of interest statement

The authors have no potential conflict of interest to declare.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank all our discipline experts for taking the time to participate in our DELPHI survey. We also thank Ms Kelli Flowers for her contribution to the project in its early stages.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. National Initiative for the Care of the Elderly (2009). “Core interprofessional competencies for gerontology.” from http://www.nicenet.ca/files/NICE_Competencies.pdf.

References

- Aged Care Workforce Strategy Taskforce (2018). A matter of care. Australia’s aged care workforce strategy. Report of the aged care workforce strategy taskforce, https://www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/a-matter-of-care-australia-s-aged-care-workforce-strategy.pdf

- Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. doi:10.1080/1364557032000119616

- Australian Government. (2019, 14 January). Aged care workforce strategy taskforce. Retrieved February 21, 2019, from https://agedcare.health.gov.au/reform/aged-care-workforce-strategy-taskforce.

- Australian Industry and Skills Committee. (2018). Industry reference committee to shape aged services workforce. Retrieved July 13, 2020, from https://www.aisc.net.au/hub/industry-reference-committee-shape-aged-services-workforce.

- Australian Industry and Skills Committee. (No date). Aged services industry reference committee. Retrieved July 13, 2020, from https://www.aisc.net.au/irc/aged-care-industry-reference-committee.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2014). Australia’s health 2014. Australia’s health series no. 14. Cat. no. AUS 178. Canberra, Australia: AIHW.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2018). Older Australians at a Glance. Retrieved July 13, 2020, from https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/older-people/older-australia-at-a-glance/contents/summary.

- Australian and New Zealand Podiatry Accreditation Council (2009). Podiatry competency standards for Australia and New Zealand. Retrieved 16 November 2018 from http://www.anzpac.org.au/files/Podiatry%20Competency%20Standards%20for%20Australia%20and%20New%20Zealand%20V1.1%20211212%20(Final).pdf

- Australian Orthoptic Board. (2015). Competency standards for orthoptists. Retrieved 23 November 2018 from https://www.australianorthopticboard.org.au/Downloads/Competency%20Standards%20Jul15.pdf.

- Australian Dental Council. (2016a). “Professional competencies of the newly qualified dentist.” Retrieved 16 November 2018 from https://www.adc.org.au/sites/default/files/Media_Libraries/PDF/Accreditation/Professional%20Competencies%20of%20the%20Newly%20Qualified%20Dentist_rebrand.pdf.

- Australian Dental Council. (2016b). “Professional competencies of the newly qualified dental hygienist, dental therapist and oral therapist.” Retrieved 16/11/2018 from https://www.adc.org.au/sites/default/files/Media_Libraries/PDF/Accreditation/Professional%20Competencies%20of%20the%20Newly%20Qualified%20Dental%20DH%20DT%20OHT_rebrand%20Final.pdf.

- Australian Medical Association. (2019). AMA submission to the Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety–18/237. https://ama.com.au/sites/default/files/documents/AMA%20submission%20to%20the%20Royal%20Commission%20into%20Aged%20Care%20Quality%20and%20Safety%20FINAL_0.pdf.

- Australian Skills Quality Authority. (2013). Report. Training for aged and community care in Australia. A national strategic review of registered training organisations offering aged and community care sector training. https://www.asqa.gov.au/sites/default/files/Strategic_Reviews_2013_Aged_Care_Report.pdf?v=1508135481.

- Carnell, K., & Paterson, R. (2017). Review of national aged care quality regulatory processes. https://wwhttps://www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/review-of-national-aged-care-quality-regulatory-processes-report.pdfw.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/review-of-national-aged-care-quality-regulatory-processes-report.pdf.

- Carraccio, C., Englander, R., Van Melle, E., Ten Cate, O., Lockyer, J., Chan, M. K., … Snell, L. S. (2016). Advancing competency-based medical education: A charter for clinician-educators. Academic Medicine, 91(5), 645–649. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000001048

- Clark, M., Raffray, M., Hendricks, K., & Gagnon, A. J. (2016). Global and public health core competencies for nursing education: A systematic review of essential competencies. Nurse Education Today, 40, 173–180. doi:10.1016/j.nedt.2016.02.026

- Conway, J. F., P. Little, M. McMillan and M. Fitzgerald (2011). Determining frameworks for interprofessional education and core competencies through collaborative consultancy: The CARE experience. Contemporary Nurse: A Journal for the Australian Nursing Profession, 38(1–2), 160–170.

- Creswell, J.W., Plano Clark, V.L. (2011). Designing and conducting mixed methods research (2nd Edition). Los Angeles, California: Sage Publications.

- Damron-Rodriguez, J. (2008). Developing competence for nurses and social workers. AJN American Journal of Nursing, 108(9), 40–46.

- Damron-Rodriguez, J., Frank, J. C., Maiden, R. J., Abushakrah, J., Jukema, J. S., Pianosi, B., & Sterns, H. L. (2019). Gerontology competencies: Construction, consensus and contribution. Gerontology & Geriatrics Education, 40(4), 409–431. doi:10.1080/02701960.2019.1647835

- Dental Board of Australia. (2016). Entry-level competencies: Public health dentistry (community dentistry). Retrieved 16 Nov 2018 from https://www.dentalboard.gov.au/documents/default.aspx?record=WD16%2F20910&dbid=AP&chksum=KRrGQSxsTZqGYmkVSShCjw%3D%3D

- Department of Health. (no date). Aged care workforce strategy. https://webarchive.nla.gov.au/awa/20191107015214/https://agedcare.health.gov.au/reform/aged-care-workforce-strategy-taskforce.

- Dietitians Association of Australia. (2015). National competency standards for dietitians in Australia. Retrieved 16 Nov 2018 from https://daa.asn.au/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/NCS-Dietitians-Australia-with-guide-1.0.pdf.

- Eklund, K. W. K. (2009). Outcomes of coordinated and integrated interventions targeting frail elderly people: A systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Health & Social Care in the Community, 17(5), 447–458. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2524.2009.00844.x

- Ey, C. (2018). The vocational education and training sector: A quick guide. Retrieved February 12, 2020, from https://www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/Parliamentary_Departments/Parliamentary_Library/pubs/rp/rp1819/Quick_Guides/VocationalTraining.

- Frank, J. R., & Danoff, D. (2007). The CanMEDS initiative: Implementing an outcomes-based framework of physician competencies. Medical Teacher, 29(7), 642–647. doi:10.1080/01421590701746983

- Frank, J. R., Snell, L. S., Cate, O. T., Holmboe, E. S., Carraccio, C., Swing, S. R., … Harris, K. A. (2010). Competency-based medical education: Theory to practice. Medical Teacher, 32(8), 638–645. doi:10.3109/0142159X.2010.501190

- Freeman, M., K. Flowers, M. Van Den Dolder, C. Dobson, J. Masso and A. O'Flynn (2009). Domains of aged care nursing practice, South Western Sydney Local Health District Aged Care CNCs, Sydney, Australia.

- Geriatrics Interdisciplinary Advisory Group. (2006). Interdisciplinary care for older adults with complex needs: American geriatrics society position statement. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 54(5), 849–852. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00707.x

- Glista, S. and M. Petersons (2003). A model curriculum for interdisciplinary allied health gerontology education. Gerontology and Geriatrics Education, 23(4), 27–40.

- Goldberg, L. R., Koontz, J. S., Rogers, N., & Brickell, J. (2012). Considering accreditation in gerontology: The importance of interprofessional collaborative competencies to ensure quality health care for older adults. Gerontology & Geriatrics Education, 33(1), 95–110. doi:10.1080/02701960.2012.639101

- Hartgerink, J. M., Cramm, J. M., Bakker, T. J. E. M., van Eijsden, R. A. M., Mackenbach, J. P., & Nieboer, A. P. (2014). The importance of relational coordination for integrated care delivery to older patients in the hospital. Journal of Nursing Management, 22(2), 248–256. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2834.2012.01481.x

- Hasson, F., Keeney, S., & McKenna, H. (2000). Research guidelines for the Delphi survey technique. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 32, 1008–1015.

- Kappelman, M. M., L. A. Bartnick, B. Cahn and M. I. Rapoport (1981). A nontraditional geriatric teaching model: Interprofessional service/education sites. Journal of Medical Education 56(6), 467–477.

- Kiely, P. M. and J. Slater (2015). Optometry Australia Entry-level Competency Standards for Optometry 2014. Clinical and Experimental Optometry, 98(1), 65–89.

- Lock, L. R. (2011). Selecting examinable nursing core competencies: A Delphi project. International Nursing Review, 58(3), 347–353. doi:10.1111/j.1466-7657.2011.00886.x

- Low L-F, M., & Lap, B. H. (2011). A systematic review of different models of home and community care services for older persons. BMC Health Services Research, 11(1), 93. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-11-93

- Ma, A. (2006). Importance and adequacy of practice competencies for care professionals in aging-related fields: The Chinese administrator's perspective. Gerontology & geriatrics education, 26(2), 17–34.

- Maridulu Budyari Gumal. (2020). Working together for good health and wellbeing. The Sydney Partnership for Health, Education, Research and Enterprise (SPHERE). https://www.thesphere.com.au/.

- Martin, J. S., Ummenhofer, W., Manser, T., & Spirig, R. (2010). Interprofessional collaboration among nurses and physicians: Making a difference in patient outcome. Swiss Medical Weekly, 140, w13062.

- McGaghie, W. C., Miller, G. E., Sajid, A. W., & Telder, T. V. (1978). Competency-based curriculum development in medical education. In An introduction. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organisation.

- Mezey, M., Mitty, E., Burger, S. G., & McCallion, P. (2008). Healthcare professional training: A comparison of geriatric competencies. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 56(9), 1724–1729.

- Moyle, W., Parker, D., & Bramble, M. (2014). Care of older adults: A strengths based approach. Port Melbourne, Victoria: Cambridge University Press.

- National Initiative for the Care of the Elderly. (2009). Core interprofessional competencies for gerontology. http://www.nicenet.ca/files/NICE_Competencies.pdf

- Nursing and Midwifery Board of Australia. (2016). Registered nurse standards for practice. Retrieved 16 Nov 2018 from https://www.nursingmidwiferyboard.gov.au/Codes-Guidelines-Statements/Professional-standards/registered-nurse-standards-for-practice.aspx.

- Occupational Therapy Board of Australia. (2018). Australian occupational therapy competency standards. Retrieved 23 Nov 2018 from https://www.occupationaltherapyboard.gov.au/Codes-Guidelines/Competencies.aspx.

- Paramedics Australasia Ltd. (2011). Australasian competency standards for paramedics. Retrieved 16 Nov 2018 from https://paramedics.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/PA_Australasian-Competency-Standards-for-paramedics_July-20111.pdf.

- Pharmaceutical Society of Australia. (2017). Professional Practice Standards - Version 5. Retrieved 16 Nov 2018 from https://www.psa.org.au/practice-support-industry/professional-practice-standards/.

- Physiotherapy Board of Australia & Physiotherapy Board of New Zealand. (2015). “Physiotherapy practice thresholds in Australia and Aotearoa.” Retrieved 16 Nov 2018 from https://physiocouncil.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Physiotherapy-Board-Physiotherapy-practice-thresholds-in-Australia-and-Aotearoa-New-Zealand.pdf.

- Psychology Board of Australia. (2013). Guidelines for the 5+1 internship program for provisional psychologists and supervisors. Retrieved 23 November 2018 from https://Retrieved 23 November 2018 from.

- Ramcharan, P., C. David, C. Jones and R. Moors (2015). “I'm a person not a job!„: Establishing core competencies for change in brotherhood of St Laurence residential aged care. Melbourne, Victoria.

- Royal Australasian College of Physicians. (2013). Geriatric Medicine Advanced Training Curriculum. Retrieved 16 November 2018 from https://www.racp.edu.au/docs/default-source/default-document-library/geriatric-medicine-advanced-training-curriculum.pdf?sfvrsn=d7fc2e1a_10.

- Royal Australian College of General Practitioners. (2015). Competency profile of the Australian general practitioner at the point of fellowship. Retrieved 16 November11 2018 from https://www.racgp.org.au/download/Documents/VocationalTrain/Competency-Profile.pdf.

- Schapmire, T. J., B. A. Head, W. A. Nash, P. A. Yankeelov, C. D. Furman, R. B. Wright, R. Gopalraj, B. Gordon, K. P. Black, C. Jones, M. Hall-Faul and A. C. Faul (2018). Overcoming barriers to interprofessional education in gerontology: the Interprofessional Curriculum for the Care of Older Adults. Advances in Medical Education and Practice, 9, 109–118.

- Schoenmakers, E. C., Damron-Rodriguez, J., Frank, J. C., Pianosi, B., & Jukema, J. S. (2017). Competencies in European gerontological higher education. An Explorative Study on Core Elements, Gerontology & Geriatrics Education, 38(1), 5–16. doi:10.1080/02701960.2016.1188812

- Scott Tilley, D. D. (2008). Competency in nursing: A concept analysis. The Journal of Continuing Education in Nursing, 39(2), 58–64. doi:10.3928/00220124-20080201-12

- Semla, T., Beizer, B. J., Berger, S., Chernoff, R., Damron-Rodriguez, J., Goodwin C.S., Grus C.L., Kemle K., Mitty E.L., Shay K., Warshaw G.A. (2010). Partnership for health in aging: Multidisciplinary competencies in the care of older adults at the completion of the entry-level health professional degree. https://www.americangeriatrics.org/sites/default/files/inline-files/Multidisciplinary_Competencies_Partnership_HealthinAging_1.pdf

- SkillsIQ. (2020). Aged care training package product development. Retrieved July 13, 2020, from https://www.skillsiq.com.au/CurrentProjectsandCaseStudies/AgedCareTPD.

- Skinner, J. H. (2001). Transitioning from multidisciplinary to interdisciplinary education in gerontology and geriatrics. Gerontology & Geriatrics Education, 21(3), 73–85. doi:10.1300/J021v21n03_09

- Speech Pathology Australia. (2017). Competency-based occupational standards for speech pathologists. Entry level Retrieved 16 November 2018 from https://www.speechpathologyaustralia.org.au/SPAweb/SPAweb/Resources_for_Speech_Pathologists/CBOS/CBOS.aspx.

- The Australian Institute for Social Research. (2009). Developing a framework for core competencies in aged care. from https://digital.library.adelaide.edu.au/dspace/handle/2440/122944.

- The Education Committee Writing Group of the American Geriatrics Society. (2000). Core competencies for the care of older patients: Recommendations of the American geriatrics society. Academic Medicine, 75(3), 252–255.

- The Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety. (2019). Interim report: Neglect. Volume 1. https://agedcare.royalcommission.gov.au/publications/Documents/interim-report/interim-report-volume-1.pdf.

- Tsakitzidis, G., Timmermans, O., Callewaert, N., Verhoeven, V., Lopez-Hartmann, M., Truijen, S., … Van Royen, P. (2016). Outcome indicators on interprofessional collaboration interventions for elderly. International Journal of Integrated Care, 16(2), 5.

- Walsh, L., Subbarao, I., Gebbie, K., Schor, K. W., Lyznicki, J., Strauss-Riggs, K., … James, J. J. (2012). Core competencies for disaster medicine and public health. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness, 6(1), 44–52. doi:10.1001/dmp.2012.4

- Witt, R. R., Roos, M. O., Carvalho, N. M., da Silva, A. M., Rodrigues, C. D. S., & dos Santos, M. T. (2014). Professional competencies in primary health care for attending to older adults. Revista Da Escola De Enfermagem, 48(6), 1018–1023.

- World Health Organization (2015). Word report on ageing and health. Geneva, Switzerland.

- World Health Organization, Regional Office for Europe. (2016). Integrated care models: An overview. Working document. WHO, Copenhagen, Denmark.

Appendix

Multidisciplinary core competencies for health and aged care workers in Australia

Preamble

This document proposes a range of multidisciplinary core competencies specific to the care of older people, and suitable for all health and aged care workers across all settings in Australia for the purposes of providing a minimum set of universal competency standards to guide education and training and improve the standard of care of older people. They have been developed following a review of the literature and a DELPHI process with a broad range of disciplinary experts.

For any single competency, the depth of knowledge and level of engagement will depend on the worker’s scope of practice. For example, the planning and coordination of person-centered care by an aged care worker (minimum Certificate III) might focus around the personal care and social needs of an older person, while a clinician might focus on complex chronic disease management, but both workers will plan and coordinate care in a way that promotes the autonomy, independence, and functional ability of the older person (see Competency 2.1). Shared competencies for health and aged care workers may promote consistent, integrated care for older people, and facilitate teamwork and interdisciplinary practice, thus improving care and the care experience.

These competencies assume an approach to the care of older people which is both person-centered and strengths-based; and they assume that health and aged care workers are familiar (within their scope of practice) with the common diseases, conditions, and situations that impact older people (for example, delirium, dementia, sarcopenia, frailty, falls, sensory deficits, loneliness, and loss).

The core competencies in this document are intended to form the basis upon which further discipline-specific and highly specialized competencies may be built. Also, they are not intended to cover the broader generic competencies required by all health and aged care workers.

Domain 1: Assessment

Competencies in this domain relate to an understanding of normal and abnormal aging and reflect a holistic, person-centered approach to assessment, which includes the informal caregiver, as appropriate. The health or aged care worker can apply and interpret relevant/validated tools as required for assessment and understands the role of other disciplines in the assessment process.

1.1 Describes the normal aging process and differentiates normal aging from illness and disease, and identifies associated risk factors.

1.2 Conducts a holistic assessment by recognizing diversity amongst older people and applies knowledge of physical, cognitive, psychological, social, cultural, and spiritual dimensions of aging.

1.3 Explains the importance of, and adopts a person-centered approach to assessment, acknowledging the role of other disciplines in the assessment process as appropriate.

1.4 Recognizes the role and needs of informal caregivers and includes their perspectives during the assessment process as appropriate.

1.5 Demonstrates knowledge and use of relevant tools for assessment of older people and interpretation of their results.

1.6 Recognizes the impact of the range of environmental factors (including social, physical, and assistive technology) on the functional ability of the older person, and the ways in which the environment can support functional ability.

1.7 Collects, organizes, and documents relevant information related to the assessment and care of the older person.

Domain 2: Care planning and coordination

Competencies in this domain relate to person-centered care planning and coordination, including end-of-life planning. The health or aged care worker recognizes the importance of care coordination across the care spectrum and understands the role of other disciplines in providing care.

2.1 Plans and coordinates person-centered care that promotes autonomy, independence, and the functional ability of older people and their informal caregivers.

2.2 Recognizes and respects the societal, cultural, and community environment within which the care plan must be applied.

2.3 Sets priorities within the care plan that address the goals of the older person.

2.4 Involves older people actively in the care-planning process by empowering them and their informal caregivers to make informed decisions about their care.

2.5 Contributes, through referral, handover, and other communication, to effective interdisciplinary and integrated care across all levels and settings.

2.6 Evaluates the appropriateness of care plans as the health status and holistic needs of the older person changes, and initiates, or facilitates the review of the care plan when required.

2.7 Develops care plans that respect the privacy concerns of older people.

2.8 Plans and coordinates care for older people across various life stages, including end-of-life.

2.9 Recognizes scope of own expertise and that of other disciplines in care planning and coordination, and refers to other disciplines or services when necessary.

2.10 Identifies and coordinates available resources to meet care plan priorities.

Domain 3: Care Delivery

Competencies in this domain are intended to enhance the experience of older people, their informal caregivers and health and aged care workers at the point where care is experienced. Maintaining the older person’s functional ability through collaborative processes, and person-centered care is fundamental to enhancing this experience.

3.1 Recognizes diversity amongst older people and applies knowledge of physical, cognitive, psychological, social, cultural, and spiritual dimensions of aging.

3.2 Explains the importance of, and adopts a person-centered, interdisciplinary, and integrated approach to care delivery which supports autonomy, self-management, and reablement where appropriate.

3.3 Locates, and explains how legislation, standards, regulatory requirements, guidelines, codes of practice, and/or organizational policies influence care delivery within the scope of their role.

3.4 Demonstrates clinical skills and/or techniques to attend to physical, cognitive, psychological, social, cultural, and spiritual dimensions of care delivery.

3.5 Delivers evidence-based care within the scope of their role, which is timely, responsive, regularly evaluated, and modified as appropriate.

3.6 Recognizes the complexity of care needs of older people and initiates appropriate response and follow up as necessary.

3.7 Recognizes the needs of informal caregivers and identifies and facilitates caregiver support as necessary.

Domain 4: Healthy aging

Competencies in this domain are intended to promote healthy aging across the older person’s life course, through health protection, disease prevention, and health promotion. Health and aged care workers empower older people to make healthy choices by providing appropriate information, resources, and education.

4.1 Describes the social determinants of health, key risk factors, and individual behaviors that influence health over the life course.

4.2 Applies evidence-based approaches to screening, and disease and injury prevention for older people.

4.3 Advocates to older people (and their informal caregivers) interventions and behaviors that promote health and wellbeing, while respecting older peoples’ autonomy.

4.4 Provides appropriate options, information, resources, and education to empower older people (and their informal caregivers) to actively participate in maximizing their functional ability and achieving their chosen goals.

4.5 Identifies and effectively responds to the health literacy, health education, and health promotion needs of older people (and their informal caregivers).

4.6 Raises awareness in the wider community about healthy aging and the needs of older people.

Domain 5: Communication and interpersonal skills

Competencies in this domain are intended to promote quality in communication with older people across the spectrum of communication modalities. Communicating with older people in a manner appropriate to and respectful of their individual needs, contributes to empowerment of the person, supports their decision-making, and underpins person-centered care provision.

5.1 Demonstrates effective interpersonal communication skills (verbal, non-verbal and listening) with the older person and their informal caregivers.

5.2 Employs appropriate communication strategies to accommodate sensory, cognitive, language, and cultural needs.

5.3 Understands and applies the principles of informed consent for assessment, interventions, and information-sharing from the older person or informal caregiver.

5.4 Provides clear information in a timely manner that ensures the older person is advised of, and understands the assessment process and outcomes, and their care and treatment options.

5.5 Ensures the older person has sufficient discussion time for their concerns to be addressed appropriately.

5.6 Empowers the older person to be an active participant in their care plan.

5.7 Recognizes and applies appropriate use of information technology in communication and provision of services.

5.8 Demonstrates an awareness of strategies for supporting older people in decision-making, as a way of respecting their human rights and dignity.

Domain 6: Interdisciplinary team care

Competencies in this domain are intended to promote an interdisciplinary team approach to optimize care, quality of life, and functional ability of older people, while maintaining an enabling approach and a positive view of aging. This requires recognition of the importance of coordinated and interdisciplinary teams in the provision of care, an understanding of group dynamics and partnerships, and an appreciation of the skills and knowledge other disciplines can contribute to the health and aged care team. (Adapted from NICE competencies, 2009)Footnote1

6.1 Recognizes and respects the diversity of roles, scope of practice, and competence of the various health and aged care team members who work with older people.

6.2 Demonstrates an understanding of the skills and knowledge required to function effectively as a team member in the care of older people.

6.3 Recognizes the benefits and need of collaborative and coordinated care within and across the interdisciplinary teams, and accesses a range of services to achieve improved health outcomes for older people.

6.4 Demonstrates an understanding of the referral process within the interdisciplinary team and makes appropriate referrals.

6.5 Explains the importance of, and delivers person-centered care that is safe, timely, efficient, effective, and equitable through communication and partnering with older people and their informal caregivers.

6.6 Informs older people and their informal caregivers about the process and benefits of interdisciplinary team care.

Domain 7: Health and aged care systems and policy

Competencies in this domain are intended to ensure the sustainability and ongoing improvement of health and aged care systems to support older people, their families, informal caregivers, and staff to receive or provide care in the most appropriate and efficient setting and improve health outcomes.

7.1 Demonstrates knowledge of health systems, key aged care services, and interrelated systems and services that enable effective health and aged care system navigation for older people.

7.2 Demonstrates an understanding of access and equity issues for older people, and describes strategies for how these issues may be addressed.

7.3 Facilitates and advocates for older people in navigating health and aged care systems and related policies.

7.4 Demonstrates an understanding of, and commitment to the continuous quality improvement process and the efficient, effective, and equitable utilization of resources.

7.5 Explains the importance of, and participates in, processes that support the monitoring and reviewing of health and aged care systems and policies.

Domain 8: Safety and quality

Competencies in this domain are intended to ensure the safety and quality of care provided to older people, creating health and aged care systems that promote the best possible outcomes for older people, their informal caregivers and health and aged care workers. This requires understanding and responding to the specific risks and conditions experienced by the older person, without limiting their quality of life or dignity.

8.1 Demonstrates an understanding of the principles of quality improvement and participates in quality improvement and assurance activities, including receiving and responding to feedback from older people, their families, and informal caregivers.

8.2 Locates and demonstrates knowledge of, and compliance with, legislation, professional and ethical standards, regulatory requirements, guidelines, codes of practice, and/or organizational policies for the care of older people, as appropriate to their role and scope of practice.

8.3 Employs a systematic approach to identify, monitor, and manage risks and unsafe practices to maximize the safety and well-being of older people, informal caregivers, and health and aged care workers.

8.4 Understands the increased vulnerability of older persons and promotes their safety, without limiting their quality of life or right to autonomy.

8.5 Establishes rapport with the older person, searching for person-centered ways to improve their quality of life.

8.6 Understands the needs of caregivers with respect to their caring role.

Domain 9: Professional skills/practices professionally

Competencies in this domain are intended to promote the development of personal and professional skills, and to acknowledge personal and professional accountability and responsibility in providing care to older people. The health or aged care worker who embraces evidence-based practice and professional development will contribute to quality in care provision.

9.1 Delivers quality care to older people informed by the best available evidence.

9.2 Accepts shared responsibility for own professional development, and contributes to the professional development of others, considering the need for an interdisciplinary approach.

9.3 Manages resources, time, and workload accountably and effectively.

9.4 Engages in reflective practice, planning, and action for ongoing learning when working with older people.

9.5 Identifies and manages the influence of own values and culture on practice, recognizing particularly ageism and its effect on care delivery.

9.6 Understands when additional help and support is needed in the delivery of care to older people, and follows organizational escalation policies and procedures.

Domain 10: Leadership

Competencies in this domain are intended to enhance the experience of older people, their informal caregivers, and health and aged care workers through promoting a vision for high-quality care. Leaders inspire, direct, and motivate through advocating a positive view of aging and older person care.

10.1 Recognizes that everyone has leadership capacity and encourages shared leadership and appropriate task delegation when caring for older people.

10.2 Advocates for the needs of older people inside and outside their workplace to promote an inclusive society.

10.3 Recognizes the importance of mentorship, peer, and/or student support to grow and retain the health and aged care workforce.

10.4 Elevates the importance of caring for older people and shows pride in their professional role.

10.5 Applies the principles of conflict resolution where required to promote safe practice and the delivery of quality care for older people.