ABSTRACT

This study proposed and evaluated an infusion active aging education (IAAE) model to help university students develop an age-friendly mind-set and the ability to empower older individuals through intergenerational learning. The IAAE model encompasses the (1) Identification of academic champions from various faculties, (2) Active infusion of cocreated intergenerational activities into discipline-specific curricula; (3) Activity implementation, and (4) Evaluation. In total, 511 students and 129 older adults participated in this study between 2018 and 2020. A mixed-method evaluation was conducted to compare the pretests and posttests results of the students in the intervention (n = 287) and comparison (n = 63) groups and to thematically analyze the data of qualitative in-depth interviews with 29 older adult participants. The results revealed that the intervention group students achieved significant improvements in aging-related knowledge, attitudes, skills, and professional interests, whereas the comparison group students achieved significant improvement only in aging-related knowledge. The older adult participants reported improvements in their understanding of young people, sense of self-worth, and generativity. The IAAE model can contribute to the growth of age-friendly practices by enriching university curricula with intergenerational interactions through a participatory and nonprescriptive approach.

Introduction

Rapid population aging has become a global demographic phenomenon as people are living longer and having fewer children. According to the Census and Statistics Department (Citation2022), the proportion of older adults (aged 65 years and over) in the total population increased from 13% in 2011 to 19% in 2021 in Hong Kong. However, a survey of more than 9,000 Chinese adults in Hong Kong revealed that they were relatively unsatisfied with the city’s range of products and services for older adults with various needs and preferences (Cuhk, Ling, & Poly, Citation2019); this finding reflects the city’s inadequate age friendliness. Making environments more age-friendly is crucial for older adults because it improves their health and well-being (Gibney, Zhang, & Brennan, Citation2020), facilitates active aging, and improves quality of life (World Health Organization, Citation2007).

Developing age-friendly environments requires comprehensive knowledge of topics related to aging; this is especially relevant for university students entering professions that require working with or for older adults. However, students typically have limited knowledge of aging and hold stereotypes about older adults because of their limited exposure to aging-related topics in the classroom and the lack of opportunities to interact with older adults (McCleary, Citation2014; Wagner & Luger, Citation2021). To promote the development of age-friendly environments, students must have opportunities to gain knowledge and skills related to aging. This can help them communicate and interact with older adults and develop an interest in careers that involve working with and serving the aging population.

Scholars of education have infused gerontology into pedagogy to deepen young adults’ understanding of the aging society and increase their interest in working with older generations (Kok, Hash, Gould, Harper-Dorton, & Ello, Citation2018; Krout & McKernan, Citation2007). The infusion-based educational method involves the implementation of an institutionalized mechanism through which educational content on aging is embedded into formal academic curricula. Its purpose is to ensure that all students acquire basic multigenerational knowledge and interactional competence while fulfilling course objectives (Hooyman & St Peter, Citation2006).

Researchers have developed knowledge-based, strength-oriented, experiential, and organizational approaches to achieve beneficial outcomes from infusion-based education. The knowledge-based approach integrates aging-related content through supplemental reading materials in lectures, clinical case studies, and field placements (Gelman, Citation2012). The strength-oriented approach involves the active utilization of media and other resources that facilitate theoretical discussion, stimulate students’ emotional responses, and elicit further exploration of relevant topics (McCleary, Citation2014). The experiential methods provide young people with interactive, hands-on, and in-depth experiences through volunteering and service activities (Young, Lee, & Kovacs, Citation2016). Strategies for organizational change typically synthesize the bottom-up involvement of faculty, students, field instructors, community partners, and older adults with top-down institutional support for enhancing gerontological pervasiveness and sustainability (Hooyman & St Peter, Citation2006). However, studies have mostly used a single infusion-based method in disciplines such as social work (Kok, Hash, Gould, Harper-Dorton, & Ello, Citation2018) and health and social services (Boscart, McCleary, Huson, Sheiban, & Harvey, Citation2017).

Empirical evidence suggests that infusion-based educational programs are effective in enhancing students’ knowledge and skills related to aging, but most programs do not succeed in developing students’ interest in working with or for older adults. For instance, Olson (Citation2007) discovered that exposure to gerontology-related content in a Master of Social Work program did not increase students’ interest in the field. Rogers, Gualco, Hinckle, and Baber (Citation2013) reported that although undergraduates in social work who participated in a semester-long gerontology-infused research course and aging-related practicum gained considerably more aging-related knowledge, competence, and attitude, but they exhibited a slight decrease in interest in careers involving the aging population. Career interest relates to professional prospects after graduation; it affects the students’ preparation and decision-making before their professional lives and their ability to contribute to the creation of age-friendly environments. Gerontology-infused interventions should increase students’ awareness of careers related to aging and older adults. In addition to exposing students to information on and experience with the aging population, other innovative strategies should be implemented (Olson, Citation2007).

Studies have indicated that the effects of infusion pedagogy can be maximized by inviting older adults to play active roles in activities and by creating positive intergenerational contact experiences (Montepare & Farah, Citation2018; Newman & Hatton-Yeo, Citation2008; Wagner & Luger, Citation2021). Jarrott, Scrivano, Park, and Mendoza (Citation2021) identified 15 evidence-based intergenerational practices (e.g., integrating friendship mechanisms, fostering empathy, providing meaningful roles for young and older participants, and offering novel activities) that lead to effective outcomes. In addition, voluntary contact between young people and older individuals exemplifying successful aging can assuage young people’s anxiety about intergenerational communication, challenge their ageism, and improve their attitudes toward older people (Levy, Citation2018). This can also increase young people’s interest in working with or for older adults. The benefits and empowering effects of intergenerational learning can be amplified by institutionalizing aging-related infusion in academic disciplines beyond aging-specific courses and one-off educational activities. This study proposed and evaluated a theory-based intergenerational infusion learning (i.e., IAAE) model that combines infusion-based methods and incorporates active aging and intergenerational components into the curricula in various academic disciplines.

IAAE model guided by intergroup contact theory

To expand the scope of infusion education and encourage the involvement of various stakeholder groups, the second author developed the IAAE model, which was subsequently refined by the first and second authors. This model is conceptually grounded in intergroup contact theory, which hypothesizes that appropriately managed contacts with out-group members can reduce stereotypes of and discrimination against an out-group (Levy, Citation2018; Paolini et al., Citation2021). Through the application of intergroup contact theory, we designed educational activities on the basis of five facilitative conditions to achieve optimal intergenerational contact that would benefit both young and older participants; the five conditions are as follows: (1) equal status, (2) common goals, (3) cooperative interaction, (4) institutional support, and (5) opportunities for friendship (Pettigrew et al., Citation2011).

Guided by intergroup contact theory and an activity-oriented pedagogy, the IAAE model aims to promote positive intergenerational contact; increase multiple stakeholders’ awareness of and sensitivity to the challenges and opportunities associated with the aging population; improve the aging-related knowledge, attitudes, skills, and professional interests of university students; and enhance individual and institutional capacity in tertiary education to support future professionals in an aging society. During its implementation, the model encompassed four sequential components as follows: (1) the Identification of academic champions who convey the benefits and value of the pedagogy to promote the application of aging-related knowledge and skills in their respective disciplines; (2) the Active infusion of relevant intergenerational content and learning activities into course curricula and implementation of intergenerational and discipline-specific strategies co-created by gerontologists and academic champions; (3) Activity implementation; and (4) Evaluation ().

The IAAE project was initiated by the Institute of Active Ageing that strives for the promotion of active aging and quality of later life through research, education, and evidence-based practices. The project team contacted the academic departments of a local university in Hong Kong to elicit buy-ins and participation. Faculty members who indicated their willingness to adopt the infusion method were enrolled as academic champions. The project team explained the background and objectives of this project to the academic champions and then discussed the potential activities that could be implemented and were consistent with their course objectives. This co-design of activities prioritized student characteristics and curricular uniqueness.

After finalizing the details of the action plan, the project team recruited older adults who met specific criteria for the individual courses and then conducted interviews with them to ensure the activities ran smoothly. Briefing sessions, which were typically held at least 2 days ahead of the scheduled day of activity, were offered to the academic champions in case any particular changes in the activity’s content were required. Activity implementation involved preparation of the relevant materials, venue, and equipment and coordination with guests, including the older adult participants. An evaluation of the activities was conducted to determine the effectiveness of the model on multiple stakeholders.

The IAAE model combined the knowledge-based, strength-oriented, experiential, and organizational methods developed by gerontology infusion researchers and experts. It adopted co-created educational activities that adhered to the infusion principle and the favorable conditions of intergroup contact theory; these were done to support teaching strategies and improve learning outcomes. For example, in the course “Researching People, Things, and Contexts” offered by the university’s School of Design, the conduct of an experiential mahjong activity was supported by the school faculty (thus exemplifying institutional support). Young students and older adults were considered to be of equal status in this activity. In addition, they focused on becoming familiar with each other and on winning the game (i.e., a common goal), and were willing to collaborate if necessary (i.e., cooperative interaction), implying the potential to develop friendships.

presents the examples of infusion-based educational activities that were implemented through this model. The roles of older adults in these activities comprised the following: (1) sharing classmates who talked about their life experiences during various activities and events (e.g., an intergenerational cultural exchange event organized by the School of Design); (2) dialogue facilitators who participated in discussions with students regarding specific topics (e.g., facilitator for the Virtual Place Audit organized by the Department of Building Real Estate); (3) helpful teammates (e.g., teammates in a soap cycling workshop organized by the Department of Management and Marketing); (4) simulated clients whom students provided consultation services to (e.g., Eye Care service learning program conducted by the School of Optometry); and (5) various combinations of the preceding four roles. In summary, the students – older-adult interactions were either friendly or client-oriented interactions.

Table 1. Summary of curriculum infusion using the IAAE model.

Methods

Project and research design, procedure, and participants

A non-equivalent group pretest – posttest design and mixed-methods approach were used to examine the effectiveness of the IAAE model (Creswell, Citation2014; Plano-Clark et al., Citation2015). Two groups of participants were recruited, namely university students and older adults. Infusion efforts were directed to disciplinary curricula that typically lack a prevalence of aging-related components such as design, engineering, marketing, urban planning, optometry, biological and chemical technology, and hotel and tourism management. Academic champions who taught university courses were contacted through (1) the internal research and professional networks of the team members (of the present project) within their university, (2) e-mail invitations, and (3) snowball referrals by other academic champions. Older adults were recruited from the membership pool of the Institute of Active Ageing. Since its establishment, the IAA has accumulated over 4,000 members who are aged over 50 years, from different districts in Hong Kong, and interested in participating in active aging activities. The Institute of Active Ageing members were contacted by e-mail based on the following criteria: (1) aged 50 years and older; (2) Hong Kong Chinese fluent in Cantonese and/or English; (3) open-minded and willing to communicate with young people; (4) interested in participating in intergenerational learning activities for the selected subject(s); and (5) other requirements as specified by the academic champions.

In total, 11 faculty members from seven academic departments/schools of a local university were contacted and invited to participate in the project between September 2018 and December 2020. Eight of them agreed to participate as academic champions, with each implementing IAAE in one of their academic courses. Contextually relevant activities were co-created by the project team and the academic champion for each course during two to four formal meetings and through informal communication. The action plans for activity formats and content were revised multiple times because of factors such as the lack of venues, time constraints, and the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic during the later phase of the project.

The IAAE project was implemented in eight courses. A total of 511 undergraduate students and 129 older adults attended two IAAE sessions that each lasted approximately 3 hours as a part of the normal classes or learning activities that formed their course curricula. Before the first activity, briefing sessions were held for the students and older participants, in which the IAAE model and the reasons for the inclusion of older adults in regular classes were explained; these sessions psychologically prepared both the students and older participants for the activities, helped them understand their roles and potential logistical challenges, facilitated communication, and contributed to improving the outcome of the intervention.

The class size for each course ranged from 28 to 129, and the number of older participants for each class ranged from 5 to 29. Class size was one of the major considerations in our activity design process, and we determined the number of older participants suitable for each activity. For instance, we designed a highly interactive activity involving singing and dancing for a class of 28 students and 25 older adult participants. However, one activity called “virtual place audit” was attended by 129 students and 5 older adults and was held immediately after the outbreak of COVID-19 (). For most of the activities, one older adult was assigned to every four to five students. The approximate ratio of older adults to students per class was between 25:28 and 5:129.

Another 130 students from diverse disciplinary backgrounds who did not participate in any intergenerational learning activities were recruited from three courses (i.e., Comparative Social Policy, Skills and Practice for Working with Older Adults, and Preparing for Natural Disasters in the Chinese Context) conducted by another academic department, and they were assigned to the comparison group. In these courses, students were exposed to aging-related educational content but did not engage in intergenerational interaction; these activities provided reference to determine the effects of intergenerational interaction. The students in both the intervention and comparison groups completed pretest and posttest structured questionnaires. After the classes were completed, the older participants were invited to participate in semistructured interviews.

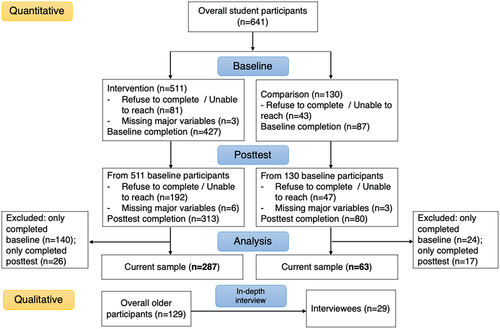

Data collection

Quantitative and qualitative data were collected between September 2018 and December 2020. A quasi-experimental design was adopted for the quantitative component. Students who participated in IAAE activities were assigned to the intervention group (n = 511), whereas those who did not receive IAAE interventions were assigned to the comparison group (n = 130). Students in both groups completed self-administrated questionnaires at the start of a semester and then at the end of a semester. These surveys were either administered online or offline. From the intervention group, 427 and 313 valid responses were collected at the baseline and posttest stages, respectively. From the comparison group, 87 pretest responses and 80 posttest responses were gathered. Ultimately, 287 respondents in the intervention group and 63 respondents in the comparison group completed both the baseline and posttest surveys. Written informed consent was obtained from all the participants.

illustrates the data collection process. To supplement the quantitative findings and develop a thorough understanding of the benefits of IAAE activities for older adults, three trained research staff members conducted semistructured in-depth interviews (30–60 min) with 29 older adults; the interviews were conducted in person or by telephone. After the interviews, supermarket cash coupons were provided to the participants as a token of our appreciation.

Measures

Knowledge about aging and older adults

A 25-item version of Palmore’s (Citation1977) Facts on Aging Quiz 1 was adapted to assess students’ knowledge of the physical health, mental health, and social well-being of aging and aged adults. Respondents answered “Yes,” “No,” and “Don’t know” to a statement in each question. The instrument exhibited good internal consistency for the sample in this study (αpre = .80; αpost = .83). Items 3, 4, 6, 9, 10, 15, and 25 covered physical health (αpre = .49; αpost = .57); items 1, 2,5,8, 11, 12, 13, 14, 16, 18, and 24 covered mental health (αpre = .65; αpost = .67); and the remaining items covered social well-being (αpre = .62; αpost = .64) (Palmore, Citation1988). The total score ranged from 0 to 25, with a higher score suggesting greater knowledge.

Attitudes toward older adults

The Chinese version of the Kogan’s (Citation1961) Attitude Toward Older People Scale was used to assess students’ attitudes toward older adults (Yen at al., Citation2009). This method applies a 34-item scale that covers common stereotypes about older adults. The scale comprises 17 positively worded and 17 negatively worded statements. The participants rated their level of agreement with each statement on a scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree). Scores for negative attitudes were reverse coded. The total score ranged from 34 to 204, with a higher score indicating a friendlier attitude toward older people. The internal consistency was satisfactory in our sample for both the entire scale (αpre = .80; αpost = .83) and the subscales of appreciation (αpre = .72; αpost = .78) and prejudice (αpre = .78; αpost = .81).

Gerontological skills

Students rated their competency in (1) interacting with older people and (2) working in a job that serves or works with older people on a scale ranging from 1 (very little skill/confidence) to 10 (highly skilled/confident). The two items were adapted from questions that were used to measure the comfort level and overall feelings of students regarding their gerontological competency (Rogers et al., Citation2013). A higher score indicates superior gerontological skills. Internal consistency was satisfactory (αpre = .80; αpost = .80).

Professional interest

Eight questions were designed to measure participants’ interest in understanding aging, their passion for careers involving working with older people, and their inclination to work with older colleagues or serve older customers (see Appendix). Students were asked to rate their interest on a scale ranging from 1 (completely uninterested) to 5 (very interested). The total score ranged from 8 to 40, with a higher score indicating a higher level of professional interest. The questionnaire exhibited satisfactory internal consistency (αpre = .92; αpost = .92) in our sample.

Demographic information

Data on the students’ gender, current year of study, department/school, and previous experience with older adults were collected for the baseline sample.

Data analysis

SPSS Version 26 was used for quantitative data analysis. Descriptive statistics and frequency distributions were used to summarize the participant demographics. Levene’s tests were employed to investigate the homogeneity of variance between the two groups. Shapiro – Wilk tests were performed to examine the normality of major variables. Because the distribution of our data was non-normal, chi-square and Mann – Whitney U tests were used to compare data of the intervention and control groups at baseline. Wilcoxon signed-ranks tests were used to detect significant changes after the intervention. As a reliable indicator of clinically meaningful changes, the effect size was calculated to evaluate the magnitude of effectiveness; the r values of 0.1, 0.3, and 0.5 indicated small, medium, and large effect sizes, respectively (Cohen, Citation1988). Statistical significance was indicated by two‐tailed p values less than 0.05.

For qualitative data analysis, interviews were transcribed verbatim and analyzed by two coders who were trained in social sciences under the supervision of two gerontology scholars. The two coders adopted a reflexive method to reduce the potential bias associated with categorizing the major themes that were verified by the gerontologists (Creswell & Poth, Citation2018). Thematic content analysis was conducted using a constant comparison method comprising three stages (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006). First, open coding was used to explore, compare, and contextualize the preliminary themes. Second, axial coding was applied to re‐organize the data into categories based on various patterns and relationships. Third, selective coding was adopted to identify and formulate the core concepts and themes. The different sources of information were compared to increase the credibility and verifiability of the model and to validate its findings (Leech & Onwuegbuzie, Citation2007).

Results

Sample characteristics

presents the characteristics of the entire student sample at the baseline. In the intervention group (n = 287), 56.4% of respondents were female and 78.4% were juniors or seniors. In the comparison group (n = 63), 60.3% of respondents were female and 71.4% were freshmen or sophomores. A chi-square test of independence revealed that the respondents in the two groups differed significantly by year of study (X2 [4, N = 350] = 120.92, p < .01). The results of Levene’s tests suggested that the variances of the two groups were equal. The Mann – Whitney U tests revealed no significant difference between the intervention and comparison groups in any of the major domains . presents the sociodemographic characteristics of the older adults who participated in the follow-up interviews (n = 29).

Table 2. Sample characteristics at baseline (University students).

Table 3. Sample characteristics of older adults participants as obtained through interviews (n = 29).

Changes in aging-related knowledge, attitudes, skills, and professional interest among students

reveals the within-group post-intervention changes for primary domains in the intervention and comparison groups. No significant change was detected in the comparison group (p > .05), except for the knowledge of aging (Z = -2.50, p < .05, r = -0.31). In the intervention group, the students’ reported knowledge of aging significantly increased with a substantial effect size (Z = -5.69, p < .01, r = -0.34), particularly their knowledge of social facts pertinent to older adults (Z = -10.78, p < .01, r=-0.64). Moreover, students in the intervention group exhibited an overall improvement in their attitudes toward older adults (Z = -3.17, p < .01, r = -0.19). Specifically, students in the intervention group displayed a significantly higher level of appreciation (Z = -2.57, p < .05, r = -0.15) and lower level of prejudice (Z = 2.83, p < .01, r = 0.17) at posttest. Their gerontological skills (Z = -4.00, p < .01, r = -0.24) also significantly improved, especially their communication skills (Z = -4.23, p < .01, r = -0.25) and professional skills pertinent to serving older adults (Z = -2.86, p < .01, r = -0.17). In addition, these students exhibited a significant increase in professional interest in working with older adults (Z = -4.79, p < .01, r = -0.28).

Table 4. Within-groups changes in the intervention group and comparison group.

Qualitative findings on the benefits of the IAAE intervention for older adults

Four overarching and mutually reinforcing themes related to the benefits of the IAAE intervention as perceived by the older adult participants emerged from the qualitative data: (1) increased self-worth through meaningful engagement at the university, (2) enhanced practical and up-to-date knowledge, (3) improved attitude toward and communication with younger people, and (4) generative achievement.

Increased self-worth through meaningful engagement at the university

All the older adult participants exhibited positive attitudes and strong support for the experiential learning activities and intergenerational contact. Several of them participated out of curiosity, and a majority reported that they had looked forward to increasing their knowledge of and interactions with young people in an academic setting.

“We can learn and work with university students about nutrition … It feels great to be of assistance in their research.” (a 70-year-old woman who participated in an Applied Biology and Chemical Technology course).

A participant also reported that her motivation to participate was mainly based on her limited experience of university when she was young:

“I haven’t tried it before. That’s why I tried it to see what would happen.” (a 64-year-old woman who participated in an applied biology and chemical technology course).

A participant who received tertiary education in her early life felt exhilarated and proud about being invited to share her lifelong learning experience with younger students. She said the following:

“The course that I studied was completely different from my previous career. Furthermore, you can meet new friends here and enjoy campus life again.” (a 68-year-old woman who participated in a design course).

Most of the older adults described the intergenerational interaction in the project as a meaningful experience that provided a sense of achievement and increased their self-worth. One older adult stated the following:

“I treasure the valuable interactions with the students, which allowed me to play a part. I take pride in my contributions.” (a 63-year-old woman who participated in an optometry course).

Enhanced practical and up-to-date knowledge

Participation in university classes increased the older adults’ knowledge of certain areas, helped them overcome challenges related to aging, and broadened their horizons. In addition to increasing their knowledge of cataracts, glaucoma, and macular degeneration, the older adults who participated in a service-learning class activity related to eye care reported increased awareness of optical issues and the methods for preventing and managing them. One participant stated the following:

“The students provided me with information that I was previously unaware of. I learned about the importance of eating food that helps me keep my eyes healthy.” (a 60-year-old woman who participated in an optometry course).

Those who attended the classes on nutrition also reported higher attention to food labels in the process of product selection, thanks to the personalized nutrition report grounded on their daily consumption by students. For example, one participant stated the following:

“After the class, I found myself to be more aware of the nutritional information displayed on food labels.” (64-year-old, female, participated in an applied biology and chemical technology course).

The older adults who participated in an urban planning and development class were invited to identify and present images of age-friendly facilities in their neighbors to students. One older adult participant discussed her heightened awareness of age-friendliness in her community and stated how people could better serve older adults.

“I am willing to introduce this [age-friendly] feature [of my community] to other people. I hope that people in the community can participate more actively in volunteer services.” (60-year-old, female, participated in a building real estate course).

Improved attitudes toward and communication with youth

The older adult participants reported that the students were genial, considerate, and interested in their involvement in class discussions, interviews, and other group activities. Several of the older adult participants reported feeling comfortable with the young students who were “really serious [about their study] and respectful to the interviewees” (a 65-year-old man who participated in a course on optometry).

Impressed by students’ diligence and professionalism in their studies and with the patience they showed toward their senior “classmates,” the older adults demonstrated an increased willingness to communicate with, learn from, and work with the young:

“We can keep ourselves young and updated without being out of touch with society” (a 62-year-old man who participated in a course of Hotel, Tourism, and Management).

An interviewee stated that she “really enjoyed listening to young people’s learning experience” (66-year-old, female, participated in a hotel, tourism, and management course) due to the excitement of viewing life and society from a younger person’s perspective and exploring the meaning of active aging. A male participant echoed this attitude; he highlighted the intergenerational discord related to recent sociopolitical problems and proposed that more events involving generational engagement should be held. He stated the following:

“With more platforms for generational communication, older, middle-aged, and young people won’t simply view a movement through their subjective lenses.” (64-year-old, male, participated in a design course).

Higher generative achievement

Most of the older adult participants also reported a higher level of generative achievement, which they acquired by playing crucial roles in the personal, academic, and professional growth of students. The older adult participants inferred that this program opened a new door for students by encouraging them to explore aging-related topics in their chosen disciplines. A participant stated the following:

“The experiential co-learning activities can help students to understand [their] needs and explore the development of (the) silver market.” (a 60-year-old woman who participated in an optometry course).

Most of the older adult participants agreed that their interactions with students represented a positive contribution to the lives of these students. On this topic, an older male participant stated the following:

“Age group represents various aspects such as life experience. I assume that [the interaction has] widened students’ perspectives” (a 64-year-old man who participated in a hotel, tourism, and management course).

Some of the older adults highlighted the importance of passing on their experience, ability to empathize, and interpersonal skills to the younger generations. A woman shared her personal experience of inappropriate treatment of eye disease by an unethical ophthalmologist; she expressed her hope that the students “can learn something like, for instance, being patient-oriented and viewing things from different angles” (a 60-year-old woman who participated in an optometry course).

Similarly, a participant shared his perspective on the physical, mental, and social dimensions of aging, and he gained a sense of achievement through discussions with students about the future product design of assistive technology devices. He stated the following:

“I touched on older people’s vision problems and joint pain, and I felt that my effort to share my experiences was worthwhile.” (a 64-year-old man who participated in a biomedical engineering course).

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to develop and evaluate a theory-based intergenerational infusion learning model that incorporates active aging and intergenerational components into the classroom curricula of various academic disciplines. A crucial contribution of this study is its replicable adoption of the IAAE intervention in seven academic schools/departments; this method was implemented to facilitate the development of an age-friendly environment and promote the social inclusion of older people from an upstream perspective. This study also contributed to the literature by exploring the perceived benefits among the older adults of their participation in the intergenerational learning activities under the IAAE model.

Consistent with intergroup contact theory, the results revealed that the favorable intergenerational contact that occurred in the classroom within the framework of IAAE helped students to develop age-friendly mind-sets and capacity. The student participants reported a reduction in their stereotypes of and discrimination against older people and an increased appreciation of older people. The students exhibited increased communication capabilities and confidence in working with older adults following their interactions in academic activities. Although the activities were not promoted as activities designed to educate students on facts about aging, the student participants formed a more realistic image of the social well-being of older adults through direct intergenerational contact (physical or virtual) in the classroom. Their increased knowledge may be linked to their interaction with older adults as friends, their self-exploration of aging-associated information out of curiosity and/or compulsory assignments that required the provision of services to older adults. Furthermore, the qualitative responses of the older adult participants reflected their enhanced self-worth, increased knowledge, improved attitudes toward communicating with young adults, and increased generative achievement, all of which were gained through their active engagement in the IAAE activities. Given the crucial role of reflection on past life stories and experiences for older adults (Bai et al., Citation2014), future programs may consider incoporating intergenerational sharing of life stories related to the course content.

The current study further revealed that students exhibit an increased desire to work with older adults after undergoing an intergenerational co-learning process; this finding differs from that of Rogers, Gualco, Hinckle, and Baber (Citation2013). This may be because the older adult participants in the study conducted by Rogers, Gualco, Hinckle, and Baber (Citation2013) mainly played a passive role in their interactions with students; specifically, they served as either research participants or service recipients. By contrast, in the current study, the intergenerational activities were designed on the basis of the components of equal status, common goals, cooperative interactions, institutional support, and opportunities for friendship, all of which are suggested by intergroup contact theory. In addition, these activities were informed by the recommended practices summarized by Jarrott, Scrivano, Park, and Mendoza (Citation2021), including training facilitators and participants (e.g., briefing sessions); offering meaningful roles (e.g., older adults serving as mentors), organizing events flexibly (e.g., modification of planned offline activities to online ones), using technology (e.g., effective use of the virtual platform as a communication tool amid the pandemic) and creating novel things (e.g., bringing the Mahjong game into the classroom). Through this unique design, older adults can actively engage in activities, which increases the likelihood that students’ stereotypes of older people will change and that their interest in working with or for older adults will increase. Compared with studying aging issues using textbooks and lectures alone, curricula that incorporate intergenerational interactions are more likely to help students develop professional sensitivity toward older adults and to combine social needs and career opportunities. The comparison group exhibited a significant increase in knowledge of aging, but not in career interest. This result supports the hypothesis that exposure to aging-related content increases knowledge but is insufficient to increase students’ professional interest (Olson, Citation2007).

Equipping future professionals with aging-related knowledge, understanding, and acceptance during their university studies is helpful for establishing an age-friendly environment. This approach creates a nonthreatening opportunity for young and old adults to interact in a safe and trust-enhancing learning environment. The infusion model can incorporate the components of active aging and intergenerational interaction into university classroom curricula. It can serve as a powerful tool for combating ageism; facilitating the exchange of experiences, knowledge, and values between generations; and supporting individual empowerment and mutual appreciation among interactive activity participants (Gamliel & Gabay, Citation2014).

The professional knowledge acquired through conventional university education methods may be inadequate for graduates to become sufficiently aware of and interested in older adults. However, this study’s proposed infusion-based method of learning about aging and older adults offers new perspectives and is expected to widen the career horizons of future professionals. In addition, older adults’ participation in education activities can enable them to realize their contribution and improve their self-worth, thus supporting the creation of an age-friendly environment. With these benefits in mind, education policymakers should promote the institutionalization of this study’s proposed model (i.e., IAAE). Mentoring schemes, service-related subjects, and common core curricula should be considered as promising areas for the development of university-level IAAE interventions.

To ensure that curricula interventions are effective, institutional support should be provided at the departmental, school, and university levels in the form of fair compensation, training, and rewards for faculty members who participate in these interventions. These incentives can ensure that IAAE activities align with the university’s missions and should thus be incorporated into mainstream educational practice. The findings of this study can benefit the Age-Friendly University network in terms of the development of age-friendly programs for students, encouraging older adults’ participation in university activities and promoting intergenerational learning (Montayre et al., Citation2022).

Limitations

The current study has several limitations. First, a larger-scale randomized controlled trial with multiple follow-up time points should be conducted to enable a robust evaluation of the short-term and long-term effects of the IAAE model. Future studies should investigate the long-term effects of IAAE-based interventions by monitoring subsequent career choices, decisions, and behaviors of students.

Second, the response rates of both the intervention and comparison groups could have affected the evaluation outcome of the current study; this was because the students who found the activities enjoyable and beneficial were more likely to respond. In future studies, incentives could be provided to encourage students to complete evaluation questionnaires and to prevent response bias.

Third, the differences between the intervention and control groups in terms of grade and major could have affected comparability because senior students and students in social sciences courses are more likely to already have knowledge of aging. To ensure the robustness of their comparisons, studies should implement IAAE activities on a given subject every other semester. In addition, quantitative analyses should be performed to comprehensively examine the benefits of the IAAE intervention for older adults.

Conclusion

Guided by intergroup contact theory and an activity-oriented pedagogy, this study developed an IAAE model and successfully engaged with students, academics, and older adults to create innovative, intergenerational, and contextually relevant components for academic curricula. The IAAE model is a promising model for nurturing future professionals with sufficient knowledge and skills that enable them to contribute to the creation of an age-friendly environment and optimize opportunities for enhancing the health, participation, and security of older people. The key components of the IAAE model should apply to other settings. Studies can examine the effectiveness of the model in cultural contexts outside Asia. Studies should also develop culturally appropriate activities and apply the model to create opportunities for intergenerational learning for younger cohorts (e.g., high school students); this can positively affect society by strengthening community ties and values, fostering familial harmony, and ensuring the sustainability of the workforce.

Human subjects

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Human Subjects Ethics Subcommittee of The Hong Kong Polytechnic University (HSEARS20180807001).

Acknowledgments

The Geron-Infusion Education initiative was jointly developed and implemented by The Hong Kong Polytechnic University under the “Infusion Active Ageing Education” project (GIE-IAAE) and The University of Hong Kong under the “Campus Ageing Mix Project for University Students” (GIE-CAMPUS), with funding support from ZeShan Foundation. We would like to thank Zeshan Foundation and the University Grant Council of HKSAR for their generous support. We would also like to thank all the participants for their participation in this meaningful project.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bai, X., Ho, D., Fung, K., Tang, L., He, M., Young, D. … Kwok, T. (2014). Effectiveness of a life story work program on older adults with intellectual disabilities. Clinical Interventions in Aging, 9, 1–8. doi:10.2147/CIA.S56617

- Boscart, V., McCleary, L., Huson, K., Sheiban, L., & Harvey, K. (2017). Integrating gerontological competencies in Canadian health and social service education: An overview of trends, enablers, and challenges. Gerontology & Geriatrics Education, 38(1), 17–46. doi:10.1080/02701960.2016.1230738

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Census and Statistics Department. (2022). 2021 Population census. Retrieved from https://www.censtatd.gov.hk/en/scode600.html

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale, N.J.: L. Erlbaum Associates. Retrieved from https://www.utstat.toronto.edu/ brunner/oldclass/378f16/readings/CohenPower.pdf

- Creswell, J. W. (2014). A concise introduction to mixed methods research. SAGE publications. Retrieved from https://us.sagepub.com/hi/cab/a-concise-introduction-to-mixed-methods-research/book266037

- Creswell, J. W., & Poth, C. N. (2018). Qualitative inquiry & research design: Choosing among five approaches (4th ed.). Los Angeles: Sage Publications. Retrieved from https://us.sagepub.com/en-us/nam/qualitative-inquiry-and-research-design/book246896

- Cuhk, H. K. U., Ling, U., & Poly, U. (2019). Cross-district report of baseline assessment on age-friendliness (18 Districts). Retrieved from Jockey Club Age-friendly City https://www.jcafc.hk/uploads/docs/Cross-district-report-of-baseline-assessment-on-age-friendliness-18-districts.pdf

- Gamliel, T., & Gabay, N. (2014). Knowledge exchange, social interactions, and empowerment in an intergenerational technology program at school. Educational Gerontology, 40(8), 597–617. doi:10.1080/03601277.2013.863097

- Gelman, C. R. (2012). Transformative learning: First-year msw students’ reactions to, and experiences in, gerontological field placements. Educational Gerontology, 38(1), 56–69. doi:10.1080/03601277.2010.500579

- Gibney, S., Zhang, M., & Brennan, C. (2020). Age-friendly environments and psychosocial wellbeing: A study of older urban residents in Ireland. Aging & Mental Health, 24(12), 2022–2033. doi:10.1080/13607863.2019.1652246

- Hooyman, N., & St Peter, S. (2006). Creating aging-enriched social work education: A process of curricular and organizational change. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 48(1–2), 9–29. doi:10.1300/J083v48n01_02

- Jarrott, S. E., Scrivano, R. M., Park, C., & Mendoza, A. N. (2021). Implementation of evidence-based practices in intergenerational programming: A scoping review. Research on Aging, 43(7–8), 283–293. doi:10.1177/0164027521996191

- Kogan, N. (1961). Attitudes toward old people: The development of a scale and an examination of correlates. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 62(1), 44–54. doi:10.1037/h0048053

- Kok, A. J., Hash, K. M., Gould, P. R., Harper-Dorton, K. V., & Ello, L. M. (2018). Context-driven gero-infusion: Lessons learned from a curriculum development institute cohort. Social Work Education, 37(7), 853–866. doi:10.1080/02615479.2018.1454418

- Krout, J. A., & McKernan, P. (2007). The impact of gerontology inclusion on 12th grade student perceptions of aging, older adults and working with elders. Gerontology & Geriatrics Education, 27(4), 23–40. doi:10.1300/J021v27n04_02

- Leech, N. L., & Onwuegbuzie, A. J. (2007). An array of qualitative data analysis tools: A call for data analysis triangulation. School Psychology Quarterly, 22(4), 557. doi:10.1037/1045-3830.22.4.557

- Levy, S. R. (2018). Toward reducing ageism: PEACE (Positive education about aging and contact experiences) model. The Gerontologist, 58(2), 262–232. doi:10.1093/geront/gnw116

- McCleary, R. (2014). Using film and intergenerational colearning to enhance knowledge and attitudes toward older adults. Educational Gerontology, 40(6), 414–426. doi:10.1080/03601277.2013.844034

- Montayre, J., Maneze, D., Salamonson, Y., Tan, J. D., Possamai-Inesedy, A., & Heyn, P. C. (2022). The making of age-friendly universities: A scoping review. The Gerontologist. online ahead of print. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnac084

- Montepare, J. M., & Farah, K. S. (2018). Talk of ages: Using intergenerational classroom modules to engage older and younger students across the curriculum. Gerontology & Geriatrics Education, 39(3), 385–394. doi:10.1080/02701960.2016.1269006

- Newman, S., & Hatton-Yeo, A. (2008). Intergenerational learning and the contributions of older people. Ageing Horizons, 8(10), 31–39. Retrieved from https://www.ageing.ox.ac.uk/files/ageing_horizons_8_newmanetal_ll.pdf

- Olson, M. D. (2007). Gerontology content in MSW curricula and student attitudes toward older adults. Educational Gerontology, 33(11), 981–994. doi:10.1080/03601270701632230

- Palmore, E. (1977). Facts on aging. A short quiz. The Gerontologist, 17(4), 315–320. doi:10.1093/geront/17.4.315

- Palmore, E. (1988). Response to“the factor structure of the facts on aging quiz. The Gerontologist, 28(1), 125–126. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3342988/

- Paolini, S., White, F. A., Tropp, L. R., Turner, R. N., Page-Gould, E., Barlow, F. K., & Gómez, Á. (2021). Intergroup contact research in the 21st century: Lessons learned and forward progress if we remain open. The Journal of Social Issues, 77(1), 11–37. doi:10.1111/josi.12427

- Pettigrew, T. F., Tropp, L. R., Wagner, U., & Christ, O. (2011). Recent advances in intergroup contact theory. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 35(3), 271–280. doi:10.1016/j.ijintrel.2011.03.001

- Plano-Clark, V. L., Anderson, N., Wertz, J. A., Zhou, Y., Schumacher, K., & Miaskowski, C. (2015). Conceptualizing longitudinal mixed methods designs: A methodological review of health sciences research. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 9(4), 297–319. doi:10.1177/1558689814543563

- Rogers, A. T., Gualco, K. J., Hinckle, C., & Baber, R. L. (2013). Cultivating interest and competency in gerontological social work: Opportunities for undergraduate education. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 56(4), 335–355. doi:10.1080/01634372.2013.775989

- Wagner, L. S., & Luger, T. M. (2021). Generation to generation: Effects of intergenerational interactions on attitudes. Educational Gerontology, 47(1), 1–12. doi:10.1080/03601277.2020.1847392

- World Health Organization. (2007). Global age-friendly cities: A guide. World Health Organization. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/ageing/publications/Global_age_friendly_cities_Guide_English.pdf

- Yen, C.-H., Liao, W.-C., Chen, Y.-R., Kao, M.-C., Lee, M.-C., & Wang, C.-C. (2009). A Chinese version of Kogan's Attitude toward Older People Scale: Reliability and validity assessment. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 46(1), 38–44. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2008.05.004

- Young, J. A., Lee, J. S., & Kovacs, P. J. (2016). Creating and sustaining an experiential learning component on aging in a BSW course. SAGE Open, 6(4), 215824401667971. doi:10.1177/2158244016679711

Appendix

Would you be interested in:

Learning more about older people?

Working with or working for older people?

Having a job that is related to older people?

Having a job that is related to serving or working with older people/customers/clients?

Being led by people who are older than 60 years in daily working situations?

Working in the same team with people who are older than 60 years in daily working situations?

Leading employees who are older than 60 years in daily working situations?

Serving older clients or customers who are older than 60 years in daily working situations?